Angela Slatter's Blog, page 81

July 12, 2015

Chatting with the Lovecraft eZine

This morning I had a lovely chat with the gents at the Lovecraft eZine. Thanks to Mike Davis, Matthew Carpenter, Rick Lai and Peter Rawlik, and especial thanks for being kind, chaps: I’d got my times mixed up and realised I only had 15mins between rolling out of bed and getting on-line. Apologies to my poor David who was pushed out the door without breakfast, and any of the neighbours who may have heard loud profanities while I attempted to tame my hair and put on some face-paint in a less-than-clownish fashion.

This morning I had a lovely chat with the gents at the Lovecraft eZine. Thanks to Mike Davis, Matthew Carpenter, Rick Lai and Peter Rawlik, and especial thanks for being kind, chaps: I’d got my times mixed up and realised I only had 15mins between rolling out of bed and getting on-line. Apologies to my poor David who was pushed out the door without breakfast, and any of the neighbours who may have heard loud profanities while I attempted to tame my hair and put on some face-paint in a less-than-clownish fashion.

Also, I totally did this podcast BEFORE I had my coffee AND without swearing. Those who know me will be looking out their windows for the other signs of the Apocalypse. My sister’s comment was “Ah, my sister, the 8th Wonder of the World.” She’ll be dealt with later.

The casting of the pod can be listened to here.

So we talked about a lot of stuff including: being Accidentally Lovecraftian; fairy tales and their influence; advice for new writers; how reading Caitlín Rebekah Kiernan’s work is like drinking a wonderfully strange alcoholic beverage; and the Tale of the Plushy Badgers.

And! Richard Luong was the other guest – he’s the illustrator for Cthulhu Wars and OMG check out his artwork!

July 9, 2015

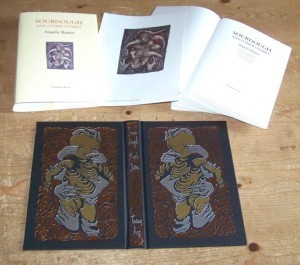

The Sourdough Posts: Sourdough

This was the story that started the Sourdough and Other Stories collection, but in a strange and wandering way. At the end of my MA, I was sending off queries letters to small publishers to see if I could interest anyone in a short story collection. What I know now is that very few publishers, large or small, will take a chance on a no-name newbie, and that’s understandable.

This was the story that started the Sourdough and Other Stories collection, but in a strange and wandering way. At the end of my MA, I was sending off queries letters to small publishers to see if I could interest anyone in a short story collection. What I know now is that very few publishers, large or small, will take a chance on a no-name newbie, and that’s understandable.

Fortunately for me, one of the publishers I sent a letter and a few sample stories to was Tartarus Press. Even more fortunately for me, the divine Rosalie Parker read the letter and the stories. She said ‘no’ to the collection, but asked if I would mind if she took the short story “Sourdough” for the next Tartarus anthology, Strange Tales II. As if I’d mind! So, my first accidental sale. That was in 2006.

In 2009 when I was writing more and the Sourdough collection was starting to take shape in my mind, I wrote to Rosalie again and asked if she’d be interested in seeing a collection of stories in that world (she’d also taken another tale for Strange Tales III, “Sister, Sister”). She was indeed interested!

So, “Sourdough the Short” was the start of it all. I had an idea about a girl who made bread into works of art; I thought about the fairy tale “Donkeyskin”, where the princess puts her jewellery into food baked for the prince and I thought about what a silly, dangerous act that was. I’d read Margo Lanagan’s tale “Wooden Bride” and the city she described there gave me an oblique inspiration for Lodellan. I chose the name Emmeline for my protagonist because it means labourer and she does indeed labour over the making and baking of her bread creations, and I chose Peregrine as the name for her lover, because it means both a pilgrim and a wanderer, and in this story he does indeed wander for a time. And Sourdough is the story I chose as a project with Kathleen Jennings, to turn the tale into a graphic story.

Sourdough [extract]

Art by Kathleen Jennings

My father did not know that my mother knew about his other wives, but she did.

It didn’t seem to bother her, perhaps because, of them all, she had the greater independence and a measure of prosperity that was all her own. Perhaps that’s why he loved her best. Mother baked very fine bread, black and brown for the poor and shining white for the affluent. We were by no means rich, but we had more than those around us, and there was enough money spare for occasional gifts: a book for George, a toy train for Artor, and a thin silver ring for me, engraved with flowers and vines.

The sight of other children in other squares, with Father’s uniquely gleaming red hair, did not bother Mother at all. After he died, I think she found it comforting, to be reminded of him by all those bright little heads.

Our home was in one of the squares at the edge of the merchants’ quarter – the town was divided into ‘quarters’ that weren’t really quarters. Seen from above, the town.

It was a large square, made up of groups of much smaller squares (tall houses built around a common courtyard); in the centre of the town was the Cathedral, high up on a hill, then spreading around it in an orderly fashion were rows and rows of city blocks, the richest ones nearest the Cathedral, then the further out you got, the poorer the blocks. We sat just before the poorest houses, not quite good enough to be in the middle of the merchants’ rows, but still not in among the places were rats shared cradles with babies. We had several large rooms mid-way up one of the tall houses, and Mother leased out the big ground-floor kitchen for her business.

From the time I could walk I would follow Mother around the kitchen, learning her art. For a while she was simply annoyed by my constant presence, as I got under foot, but when I learnt to sit on the bench next to the huge wooden table on which she kneaded the bread, and be quiet, she decided to share her knowledge. I was her firstborn, after all, and her only daughter.

When I could see over the top of the table, I started to help her. Baking tiny child’s loaves at first for practice, much to Mother’s amusement, then making the dark, ‘poor’ bread for those who could not afford refined flour. Finally, I was allowed to create white bread to grace the tables of the rich: those born to wealth and knowing nothing else, the higher merchants, the bishop and his like. I began to create complicated twists of dough to look like artworks. At first Mother laughed, but the orders kept coming for them, so she watched and imitated me.

One morning, after we’d finished baking for the day, I began to play with the leftover dough on the board in front of me. Soon a child formed, a baby perfectly copied to the life, with tiny hands and feet, an angel’s smile and a sculpted lick of hair on its forehead.

Mother came up behind me and stared. She reached past me and squashed her fists down on the dough-child, pushing and kneading until it was once again a featureless lump.

‘Never do that. Never make an image of a person or a child. They bring bad luck, Emmeline, or things you don’t want. We don’t need any of that.’

I should have remembered the dough-child, but memory is a traitor to good sense.

*

Art by Kathleen Jennings

There was to be a wedding, arranged, a fine society ‘do’ and we were to supply the bread.

The parents of the groom – or rather, his mother – insisted on being involved in every decision pertaining to the wedding, so there was a power struggle in train between her and the bride’s mother (two titans in boned bodices). Things were getting tense, apparently – this information we had from Madame Fifine (about as French as Yorkshire pudding), the confectioner who was to supply the bonbons for the wedding feast. We were to appear at the groom’s parents’ house, goods in tow, to show our wares.

Mother and I tidied ourselves as well as we could, pulling flour-free dresses from chests and piling our hair high. Artor and George were press-ganged into carrying the wooden trays of our finest white breads to the big house near the Cathedral. We were shown into a drawing room almost as big as our ground-floor kitchen.

As soon as the boys gingerly laid the trays on the big table, Mother shooed them out. I knew they’d be in the stableyard, bumming cigarillos from the stable and kitchen lads, eyeing the horses longingly, waiting for the day when Mother could afford a horse and carriage (that day was a long way off, but they hoped the proceeds from the wedding would speed up the process).

The drawing room was awash with boredom. The parents sat stiffly across from each other on heavily embroidered chairs whose legs were so finely carved it seemed that they should not be able to support the weight of anyone, let alone these four who almost dripped with the fat of their prosperity. The bride, conversely, was thin as a twig, nervous and sallow, but pretty, with darting dark eyes and tightly pulled hair sitting in a thick, dark red bun at the base of her neck. The groom did not face the room: he had removed himself to the large French window and was staring at the courtyard below (probably watching my brothers watching his horses). He had dark hair, curly, that kissed the collar of his jacket, and he was tall but that was all I could tell. Madame Fifine had said he was called Peregrine.

Mother nodded to me and I took the first loaf from one of the trays, showed it to the clients so they could observe its clever shape (a church bell with bows), then placed it on a platter and cut six slices for them to taste. The two mothers, the two fathers, the bride all took their slices and the room was silent but for their well-bred chewing. I crossed the room and offered the groom the last slice. He didn’t turn, merely raised his hand in a ‘no’ and shook his head. I noticed his hand bore the stain of a port-wine birthmark.

‘It would be a shame, sir, to waste something so fine.’

Perhaps struck by the fact that I spoke to him, he looked at me and broke into a smile.

‘Yes. You’re right. It would be a shame.’ He took the bread, green eyes bright. ‘What hair you have, miss.’

I blushed.

‘Emmeline.’ Mother called me and I began my task over again: now the loaf shaped like a flower, now the one like an angel, now all the animal shapes (rabbits, doves, kittens, a horse), the one like a church. Each time I saved his slice until last and we spoke in low voices, he asked me about my life and laughed at my pert answers. When the tasting was finished, the mothers began to argue; the design to choose was the cause of combat. Finally, they turned to the girl, Sylvia, and made her decide. She had the look of a trapped animal and I felt sorry for her.

‘Perhaps…’ I began and all eyes turned to me, the mothers’ brimming with affront, the fathers’ with boredom, the groom’s with amusement, my own mother’s with something like dread, and the bride’s with hope of rescue. ‘Perhaps Miss Sylvia has a favourite animal or flower. We could make the bread to her choice if she does not like what we have brought today.’

‘A fox!’ she cried, clapping her hands to her mouth as if she had said something a-wrong or too bold. I smiled and she said more firmly. ‘Yes, a fox. That would please me.’

‘As you wish, Miss Sylvia.’ Mother’s voice was a relieved breeze. ‘My Emmeline can make anything with her hands; she has great skill.’

So it was settled. The bride had spoken, and defied both her mother and future mother-in-law. Mother and I hefted the wooden trays scattered with the remains of butchered loaves and made for the door. The groom was there before the footman and ushered us through. He smiled and I felt as warm as bread fresh from the oven.

***

?

July 8, 2015

In which the Dance of Happiness is Done

Lisa’s photo

So I woke to a text from my dearest Brain, Lisa L. Hannett, sent while she was exploring far-flung Lindisfarne on her Great Viking Adventure Time, saying “WAKE UP WAKE UP WAKE UP, MY BRAIN, YOU’RE ON THE WFA SHORTLIST!”

And so, All of the Dancing was Done. It’s lovely that my first and second WFA noms were both for Tartarus Books!

The Bitterwood Bible and Other Recountings – from my lovely publisher Tartarus Press and with illustrations by the wonderful Kathleen Jennings – is shortlisted for Best Collection along with (and yes, gasp with amazement as these are truly awesome collections):

Mercy and Other Stories, Rebecca Lloyd (Tartarus)

Gifts for the One Who Comes After, Helen Marshall (ChiZine)

They Do the Same Things Different There, Robert Shearman (ChiZine)

The Bitterwood Bible and Other Recountings, Angela Slatter (Tartarus)

Death at the Blue Elephant, Janeen Webb (Ticonderoga)

The rest of the shortlists are here and include the likes of the superb Kaaron Warren, Jeff VanderMeer, Scott Nicolay, Ellen Datlow, Galen Dara, Kelly Link … I’ll stop before I just everyone.

July 5, 2015

The Way to Wolf Creek: Aaron Sterns

The disarmingly delightful Aaron Sterns, horror writer extraordinaire, took some time out to answer a few questions for me about writing Wolf Creek (film and novel), giant crocodiles, stalking John Jarratt, and the future of horror.

The disarmingly delightful Aaron Sterns, horror writer extraordinaire, took some time out to answer a few questions for me about writing Wolf Creek (film and novel), giant crocodiles, stalking John Jarratt, and the future of horror.

What do readers need to know about Aaron Sterns?

I’m unashamedly a horror writer. It seems to be fashionable for authors to distance themselves from the genre once they’ve had their start — to instead proclaim themselves exponents of dark fantasy, or weird fiction, or supernatural romance or whatever. Even Barker qualified himself as a writer of the ‘fantastique’. But I’m of the school of thought that horror is a largely-inclusive realm (beneath the overall huge banner of fantasy) that encompasses any example of fiction or film that addresses the dark side of experience (thanks Douglas E. Winter). With the slipstreaming of genres post-postmodernism I’m not sure how people can easily ghettoise certain works anyway. Is Game of Thrones epic fantasy, or does it use so many elements of horror and is so nihilistic in its view of human nature and life that it’s more attuned to the more maligned genre? And who cares anyway, except that it has an impact on you, which should be the inspiration of all art. Not being ashamed of the label, I’ve been fairly singular in my pursuit of horror since I started to seriously pursue fiction in my teens — some thirty years ago now — in an effort to understand (or tackle) some of the existential fears I was feeling (and still feel). Fears that only seemed to be overtly addressed in the dark fiction I was reading at the time — novels such as Huxley’s Brave New World, Orwell’s 1984, most of Ballard, etc. I’ve been lucky enough to pursue this search in many fields too, beginning in academic study to round out my understanding, then moving into short fiction and novels, and on to screenwriting as well. I’m now in the fortunate position of working both as a novelist and screenwriter, something that is a rarity in Australia (though it’s taken decades of work to achieve).

Tell us about your involvement with the Wolf Creek films.

Greg McLean and I met through a friend of mine from uni and I ended up sharing their writing office space. I was the horror fiction/ theory guy, our friend Dan was the artist, and Greg was the film-maker. We’d pass work back and forth to critique and eventually Greg enticed me to put some of my outspoken theories into practice and write some screenplays with him (including a ‘fast zombie’ idea that was unfortunately squashed by the Dawn of the Dead remake a year later). I guess I was an unofficial consultant on the first Wolf Creek, and I also have a fun little cameo in it (as I have in most of Greg’s films, actually). During post on the film there was a lot of talk about sequel ideas, and at one stage Greg and I came up with something we thought was pretty cool and could actually be a worthy sequel and not just a safe, cynical rehash (as lots of people were seriously suggesting the sequel should be). We wanted something that set itself up as repeating events, only for it to take a tangent and venture into new territory. Great, Greg said, you’re the horror guy. Go write it.

How did that translate to the novel Wolf Creek: Origin?

Initially, I was acting more as a curator for a potential series of Wolf Creek novels. Greg had been approached by Penguin for six novels, so we sat down in our trusty haunt Mario’s in Fitzroy one day and blocked out the entire series on napkins. The first was to be the juiciest: Mick’s tortured upbringing and first stumbling attempts at killing. As my background’s fiction and I’d already co-written the film sequel, Greg argued I was the obvious choice to write Mick’s origin story. I was busy with my own novel at that stage, so said no a couple of times. But I eventually realized I’d never again have the chance to develop the mythology of perhaps Australia’s most iconic villain again. And I’d always wanted to write a serial killer novel — a subject that’s disturbed me since I was a teenager because the psychology is so foreign to me, and still is. The deadline was so tight from conception to submission (about three months) that I didn’t have time to second-guess myself or be overawed by the opportunity. I mapped out the story during a lightning research trip to Queensland (to visit John Jarratt’s birthplace, and check out a cattle station nearby), then launched straight into it.

Does collaboration come naturally to you after working on film scripts such as Rogue, with Greg McLean?

Does collaboration come naturally to you after working on film scripts such as Rogue, with Greg McLean?

Starting out as a fiction writer I was no doubt as precious about my golden words as anyone. A publication rejection would send me into a spiral of self-doubt. But film is all about collaboration and taking notes and not taking anything personally. You have to have a clear vision and faith in yourself, but you also have to be objective enough to know when you’re wrong. It’s not easy to both believe in something and simultaneously be open to its destruction. Critiquing and reading others’ works (as a script-editor for instance) also helps in this, I think, because it’s always easier to tear someone else’s work apart than your own. You just need to divorce yourself from your own work enough to see it as someone else’s. So I’m becoming quite comfortable with working with others — at least in screenwriting — and am now even inviting co-writers to work on me with my own material I’ve been developing for some years, because I recognize the value another point of view brings. Fiction’s a whole different matter though. I think prose really needs to be filtered through one vision, but you never know.

What draws you to writing horror?

That’s such a huge question, it’s almost hard to quantify. I’ve always had a dark sensibility, and I struggled with existential issues quite young (and still do). I think I turned to horror because it was raising questions I myself was struggling with (the purpose of life — or lack of it, the terror of random violence, the senselessness of death, the lie of an afterlife). For me, it’s the one field that asks the big questions, and isn’t necessarily required (at least in its best examples) to provide safe and comforting answers. Cosmic horror for instance, such as the H.P. Lovecraft stories I devoured as a kid, serves only to disrupt and question existence. There are no answers, only awe. I’ve never subscribed to the whole ‘rollercoaster’ theory of horror, in which it’s supposed to provide a safe and thrilling experience of fear, before ejecting the viewer out into the bright light of the real world. The definition of horror is of a “lasting dread” — not a momentary sensation of terror or suspense, but a long-lingering emotion. The works that had most impact on me wormed their way inside my head and changed my view of the world forever (such as American Psycho, Crash, etc.). Then a fellow writer once read one of my stories and said later she couldn’t see her own family the same way ever again (it’s okay, she’s still with them). That’s my aim — to not be a safe flash-in-the-pan thrill for the reader/ viewer, but to change their perspective, perhaps permanently. To educate, if you will.

Who were/are your literary heroes/influences?

Cormac McCarthy, J G Ballard, Bret Easton Ellis and William Faulkner probably had the most effect on me along the way — all of which I would either consider Modernist or Postmodernist writers. Specifically in the horror field I’d say Jack Ketchum, Clive Barker, early King. And then there are screenwriters such as Andrew Kevin Walker, Eric Red, Paul Schrader, and filmmakers such as David Cronenberg. I unfortunately don’t get much time to read anymore, and I don’t have the patience or the… forgiveness I once used to have, so tend to half-finish things a lot, but if there’s a new Ketchum available I’ll devour that piece of beauty in a heartbeat.

What is your favourite horror film and why?

Although I love a lot of Cronenberg’s films (Videodrome was one of those very works that changed my view of the world), my absolute favourite film would be a toss-up between Jacob’s Ladder and Carpenter’s The Thing. Jacob’s Ladder is a very emotional, existential work that affects me every time I watch it. And the grounding of its supernatural qualities in the gritty world of New York has been very influential on my own writing. My first short story ‘The Third Rail’ was set in New York, for instance. But The Thing is possibly the perfect horror film, in that it expertly oscillates between character-driven suspense and paranoia, and boasts some of the most imaginative and visceral special effects ever created. Some of the visuals were so imaginative and iconic — such as the spiderhead — that it eclipsed anything else I’d seen. Yet despite this the film’s themes are cerebral, striking to the heart of what it means to be human (much like the ’70s Invasion of the Body Snatchers, another film that shifted my worldview). I also love that the horror is shown in full, and isn’t held back by any of the usual “don’t show anything, it’s much better in the imagination” guff. I’ve always been of the opinion that if it happened you show it. The characters can’t escape what’s happening, so why should the viewer?

How does it differ: writing prose to writing a film script? Do you need to consciously change how you approach the project?

The writing skills are completely diametric in many ways. Screenplays require short sharp sentences, can have no internal description, and must adhere to a very formalized structure on the page which can get in the way of the flow of the actual writing process. Fiction in many ways is much more demanding, because it requires so much more description and ‘presence’ in that world. You have to know every detail intimately (even if you don’t describe it). And on top of that it has to read beautifully and have variances in pace and length and all the thousand other things a fiction writer has to be aware of at any one time. There are certainly some stories I feel are more attuned to one medium — a small, sharp idea might be more appropriate for a short story, something epic and convoluted for a novel series, a punchy, visceral idea for a film. Of course, sometimes you can get added currency by developing an idea across several platforms, but often a novel or short story won’t translate to film — it’s a too-complex or too-simple idea, or it’s not right for the current marketplace, or it doesn’t have a strong enough hook, or something else has just been released that steals its thunder. It’s possibly a matter of choosing your battles wisely.

The future of horror is …?

The future of horror is …?

It’s hard to pick for the genre itself. I can really only speak to where I hope it goes. I hope it’s honest, challenging, prepared to still push boundaries in these politically correct times, just as it’s always striven for. I think social commentary via culture — whether visual/ performance art, or fiction, or film — is more important now than ever, considering how fractured and downward-spiraling the world seems to be, at least to a pessimist (nee realist) such as myself. The metaphor of art can sometimes glean the most truth. Suppression of expression benefits no one.

What’s next for Aaron Sterns?

It’s going to be a busy, busy year. I’m attached as a writer to no less than six films in development. Some are paying jobs and hopefully stand good chances of getting made. Others are spec scripts, some of which I’ve been developing myself for years now and believe are strong. In fact, I’m contracted to turn in three scripts in the next three months. It’s going to be hellish (I tend to write quite slowly, agonizing over every line, dammit), but I just have to push through one a month, and then collapse in a heap in September — although I’ve just been offered another two more gigs in the past week, so I’m not sure I’ll even get much time off when these three are done. I’ve just resecured a fiction agent and she’s sent out my next novel Vilka?i. I have plans for two more works in that world if I get the chance. Plus there’s nonfiction articles coming out, a couple of short stories under consideration, things like that. And I hope to rekindle my involvement with my old university, Deakin. They’ve asked me to return as a Conjoint Senior Lecturer to mentor the new crop of film and literature students. Not sure where I’m going to get the time for that on top of everything (including a hilarious three-year old vying for my attention), but I’d love the opportunity to help out enthusiastic new creatives. It’s all quite overwhelming, but I never lose the sight of the fact I’ve worked hard for these opportunities, and nothing is a given in this life. You make your own luck, and it’s now up to me to work even harder to bring some of these things to fruition. We’ll see how successful I am in another year, I guess.

July 1, 2015

Aaaaaannnnd!

The lovely Belinda Jane Morris has finished her artwork inspired by my story “A Good Husband” in Sourdough and Other Stories!! I love it!

June 30, 2015

The Sourdough Posts: The Bones Remember Everything

Rackham’s Maid Maleen

This was a really challenging story to write because I’d had the scene of spinning hair and making a tapestry from a body in my head for a couple of years before I wrote the full tale. I’d done a very early version of it when I was still a very new writer (at the start of my MA) and knew that it was, at that stage, beyond the reach of my talent. So, I had to hang onto it until I was a much better writer, until I could do it justice.

The title came from a line of a poem I’d heard read ages ago at a VoiceWorks event; a poem about immigration and memory. I thought it an exquisite phrase and have also used it for the name of this blog.

Of course, when I finally got around to writing the story to fit into the Sourdough mosaic, it was still difficult to write. I was pleased with myself at the end: I’d managed to work in both the fate of Dibblespin’s sister Ingrid, and the back story of Rilka, a nun and the Marshall of a Battle Abbey of the Church Militant who appears later in “Sister, Sister”, and allowed Ella from “The Shadow Tree” to ghost through like a dark presence, and referenced the tower from “Little Radish”. I’d woven in the tale of the great and terrible making of the bodily tapestry. I was pleased … but I wasn’t entirely sure it worked; it felt untidy, ragged at its edges.

Feedback from Lisa confirmed my suspicions, and resulted in one of the biggest eviscerations I’ve ever done of a story. A terrifying and ambitious process, to cast aside all preconceptions of what you think the story was/is/should be and remake it, turning the tale into a kind of wordish Frankenstein’s monster. And at the end of it all, the gratifying response from my alpha reader that now, all was well.

It’s a tale about blood and families, sisters and loss, about stories within stories, about bones and babies and the prick of a thorn.

The Bones Remember Everything

I walked for three days.

I had not left a note for Rilka, left her no clue; I had not thought of my lover when I entered the woods. The wolves were shadows and did not bother me. Need for neither food nor drink slowed my progress. There was only the voice, which no longer simply inhabited my dreams, but hummed through the waking hours like a daylight lullaby. I kept going until I reached the place where I was told I needed to be. Ingrid, welcome home.

The path ended abruptly at a prickly barrier; a hide of thorns so thickly grown and woven that I couldn’t make out what lay beyond. The bushes stretched as far as I could see. Left and right, the briars had melded with the usual flora, and there was no way past to be found. I reached up in frustration, to touch one of the branches, but I misjudged and snagged a finger on a long barb.

I put the digit in my mouth and sucked away the welling fluid, tasting its metallic tang. In front of me, though, the drop of blood remaining on the tip of the spike gleamed then began to eat away the brambles just as acid attacks metal. Soon, there was a wound in the wall, big enough for me to walk through. I gave one final look back to see the obstacle continuing to be erased as if it had never been.

Ravens hopped across an untamed lawn and a grey stone tower rose up in the middle of the clearing. Lining the crenellations were statues – not gargoyles but cats. A single door at the base stood ajar. I did not hesitate; the voice urged me on.

Inside, at the bottom was a disused kitchen; then halfway up, a library with shelf-lined

Original art by Stephen J. Clark

walls; finally at the very top of a spiral of age-smoothed stairs a circular room waited. Four arched windows, set across from each other, to the four compass points, let in light. In one area was a spinning wheel covered in cobwebs; a stool was placed in front of it. A four-poster bed crumbled quietly, its hangings all decayed, and bookshelves had been picked bare by birds and mice looking to cushion nests. Only a tiny cat and raven, cleverly carved in stone, lay over-turned on the splintered wood. Against another part of the wall hung a frame made of bones; stretched across it was a covering of skin. At its foot stood a rough-hewn table and on that table were thread, a needle, a quill and a very large jar – almost a glass pail, really. At first, I thought it filled with ink, but closer inspection showed it to be a sluggish dark red, uncongealed. The lid came away with surprising ease. The scent of iron made me dizzy.

The very air seemed to be waiting

The quill was sharp, and when I picked it up, I felt a tingle in my hand that thrummed up my arm and made my shoulder ache. I dipped the nib into the ichor-ink and stood in front of the strange canvas. I swiftly sketched a woman, the one whose voice sang from my dreams. Without knowledge I understood that she shared my blood. The liquid soaked straight into the surface, did not run or smear; it knew where it was to stay.

When the drawing was done, I waited for the outline of the face and body to dry. I picked about the chamber, trying to find a trail, a story in the leftovers of a life. There was little enough and I realised that the only truth was that of the bones.

I closed my eyes and saw a girl sitting by a window, the north-facing window of that very tower, spinning. The thread her efforts produced was long and fine, flax entwined with strands of her own dark hair—she had been at the work for some time. Every so often she pricked her finger and the crimson welled, then was absorbed into the filaments as she caressed them with something like love, something like hate. The pain didn’t bother her, for she was spinning her own life, making herself into a tale, her own tale of blood and flesh and bone, and she would endure for the bones remember everything. And they will call.

I shook myself and opened my eyes. The fine silver needle was surprisingly easy to thread. As I sewed and embroidered, the fibres took on the required colour: ebony for hair, white as new snow for skin, red as a ripe apple for lips. I stitched and stitched, and wondered what would happen when I finished.

Still I did not sleep; day and night no longer mattered. I did not mind, though, for the voice called me by my name and told me its story.

***

June 29, 2015

QWC / Hachette Australia Manuscript Development Program 2015

This highly useful program is open once again, so if your novel is ready (i.e. edited and proofread and carefully plotted with well-rounded, believable characters), then enter!

This highly useful program is open once again, so if your novel is ready (i.e. edited and proofread and carefully plotted with well-rounded, believable characters), then enter!

WHAT IS THE PROGRAM?

Up to 10 emerging fiction and non-fiction writers will work with editors from Hachette Australia to develop high-quality manuscripts.

The program will run for four days in Brisbane, Queensland. Participants will each have an individual consultation with editors from Hachette Australia to receive feedback on their manuscript. During the four days, participants will also meet other publishing industry professionals such as literary agents, booksellers and established authors, and work on their manuscripts. The program will run 23–26 October 2015.

Hachette Australia does not guarantee publication of manuscripts selected for the program but reserves the first right to publish the selected manuscripts. Please read the full terms and conditions in the Application Form.

More info is here.

June 28, 2015

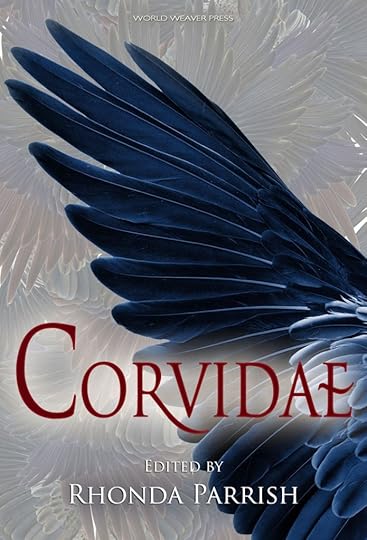

Corvidae cover reveal

And now here is the cover for the latest from Rhonda Parrish and World Weaver Press!

And now here is the cover for the latest from Rhonda Parrish and World Weaver Press!

Associated with life and death, disease and luck, corvids have long captured mankind’s attention, showing up in mythology as the companions or manifestations of deities, and starring in stories from Aesop to Poe and beyond.

In Corvidae birds are born of blood and pain, trickster ravens live up to their names, magpies take human form, blue jays battle evil forces, and choughs become prisoners of war. These stories will take you to the Great War, research facilities, frozen mountaintops, steam-powered worlds, remote forest homes, and deep into fairy tales. One thing is for certain, after reading this anthology, you’ll never look the same way at the corvid outside your window.

Featuring works by Jane Yolen, Mike Allen, C.S.E. Cooney, M.L.D. Curelas, Tim Deal, Megan Engelhardt, Megan Fennell, Adria Laycraft, Kat Otis, Michael S. Pack, Sara Puls, Michael M. Rader, Mark Rapacz, Angela Slatter, Laura VanArendonk Baugh, and Leslie Van Zwol.

You can find it here!

June 25, 2015

Echoes of Empire: Mark Barnes

The delightful and talented

Mr Mark Barnes

was kind enough to chat with me about his

Echoes of Empire

trilogy and a wide variety of other stuff. He is most excellent and has three rescue cats, Odin, Sif and Frey.

The delightful and talented

Mr Mark Barnes

was kind enough to chat with me about his

Echoes of Empire

trilogy and a wide variety of other stuff. He is most excellent and has three rescue cats, Odin, Sif and Frey.What do readers need to know about Mark Barnes?

Need to know? Probably not a lot.

I was born and raised in Sydney, though have travelled quite a bit. Like most writers I’ve a day job; in my case as a freelance organisational change consultant. Doing contract work is great for me, and allows time between jobs to write.

When I was younger I was a competition swimmer, water polo player, and volleyball player. Did the surf live saving thing without ever learning to surf. I was also more of an artist and some-time musician than a writer when I was younger, so things could’ve gone a very different way.

Though I’d flirted with writing, I’d not taken it seriously until I attended Clarion South 2005. That was a defining set of moments that helped put my feet on the path I’m on now.

When did you first decide you wanted to be a writer – was there a particular story or novel that made you think “That’s the ticket!”?

When I read Frank Herbert’s Dune in my early teens, I thought I might want to share stories with other people.Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion followed. Le Guin’s Earthsea Trilogy. Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun. I loved the layered, complex types of storytelling with compelling characters and rich worldbuilding.

I became involved in the fantasy roleplaying hobby, and that gave me the chance to share interactive stories with people, as well as to toy with character and world concepts. It was a long time before I thought of writing as something I could actually do, and share.

What was the inspiration behind your Echoes of Empire trilogy?

Boredom with the blah blahblah oh look it’s Europe in the Dark Ages fantasy. Oh look! Dudes run everything. Stories had become quite predictable, though the dark fantasy movement moved us away from shiny heroes and into stories where anti-heroes and a more cynical, grim worldview were explored.

It seemed to me that authors weren’t taking opportunities to speculate, in a genre that’s referred to as speculative fiction. There was a sense of lazy entitlement to the books available, where all the author had done was rehash our own flawed history and social mores.

I looked at what was available, had an idea for a set of characters who were at once defined by their world as they defined parts of it, and set it in an age of industrialised arcane science in an orientalist setting. From there the world building helped define what cultures looked like, how there had always been gender equality and marriage for all regardless of sexual preference, etc. A world where thinkers, courtesans, and artists were considered heroes as much as any soldier. I also wanted to explore what happens on a world where a new and different power is introduced. In this case it was humans landing on the planet, and how their technology influenced the application of arcane science down the centuries to follow.

How did you connect with 47North?

My agent, John Jarrold, is quite well connected in the industry. An experienced editor and agent, and a man with whom it’s an absolute pleasure to work, John and I had been given an offer from one of the Big Five publishers, but turned it down in favour of other opportunities. The new acquisitions editor from 47North, who John had previously shared The Garden of Stones with at his previous publisher, contacted John and asked whether The Echoes of Empire project was still available.

John and I discussed the opportunity as it would play out at the time, and accepted 47North’s offer for a three book deal based on an early draft of The Garden of Stones. The deal had us releasing all three books in print, audio, and ebook, in a span of 12 months.

And The Garden of Stones was shortlisted for a Gemmell Award – that had to make you pretty happy?

Absolutely. The Garden of Stones made the longlist for the David Gemmel Legend Award, as well as getting shortlisted for the Morningstar. It was quite surreal to get that level of international recognition, especially given pretty much nobody seemed to know about my work here in Australia.

I didn’t know it had happened until a friend of mine Tweeted me to let me know. The same friend did the same as soon as the Morningstar shortlist was announced. Truth be told the best feeling was in knowing that people were connecting with my work, and that it was serving its purpose to entertain people.

Tell us about those astonishing covers …

Tell us about those astonishing covers …Stephan Martiniere is pretty much an art god. When 47North told me they’d secured him for my covers, I was ecstatic. What’s better is that 47North asked what I wanted for all three of my covers, and Stephen shared his concept sketches with me so that we could discuss them in order to come up with the final art.

He’s easy to work with, and gifted beyond belief. I’d be fortunate to have him do other covers for me in the future.

Who is your favourite hero/villain?

Ooh. That’s a good question. I have different ones for different reasons.

My shortlist of heroes would be Paul Atriedes from Dune (with Duncan Idaho and Gurney Halleck as best supporting heroes), Obi-wan Kenobi from Star Wars, Natalia Romanova/Blackwidow, Sparrowhawk from Earthsea, Aragorn and Gandalf, and Hermione Granger from Harry Potter. I also like the conflicting ethics and morality demonstrated by Moorcock’s Elric, and Howard’s Conan. I’m also partial to Indris and Mari, and their journeys in my Echoes of Empire books.

Villains? I like smart villains, and villains whose motivations are clear and understandable rather than doing things because evil reasons. Dune gets the nod with Baron Vladimir Harokonnen, as well as the Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam. Iago from Othello, Moriarty from the Sherlock Holmes stories, Morgan le Fey, Hannibal Lecter, Medea, and Scott Lynch’s Grey King. And of course there’s my own Corajidin, and his mother the Dowager-Asrahn.

I’d like to read stories where there are more compelling women as both heroes and villains. Sadly many of the stories I’ve read don’t give enabled, capable, and malevolent women the air time they deserve.

How do you fit your writing in around a day job?

It may sound clichéd, but I sacrifice some things I’d rather be doing – things that are easier – in order to write. When I’m consulting I’ll work a long day, and follow that up with more hours writing. Weekends? Writing. Spare hours? There really aren’t any, ‘cause I’m writing.

Our books don’t write themselves. We need to make the time. If you don’t want to make the time, then don’t be a writer. Nobody owes us a living, and nobody will do the work for us.

What draws you to epic fantasy?

As a reader it’s great escapism. Well written epic fantasy also deals with social and political issues in new and interesting ways. But mainly I’m drawn to it because I live in the real world, and it’s quite nice to get away from it from time to time, and to be involved in something epic and wondrous.

As a writer it’s for many of the same reasons. Building a world that neither complies with the events of our own history, nor slavishly follows social mores that perhaps don’t make a lot of sense, is a wonderful experience. Creating cultures and histories, populating them with people, sharing the small and intimate moments as well as the ground shaking ones . . . I think it comes down to having the freedom to truly speculate about a world and its people, and the events that transpire in it. Provided I’m consistent in my world building and characterisation, there is no such thing as ‘that can’t happen.’

I’m also drawn to urban fantasy, and some elements of gothic horrors.

What is next for Mark Barnes?

John has the first of an urban fantasy quartet that’s doing the rounds. At the moment I’m working on another epic fantasy in the same world as The Echoes of Empire, though this will be darker and harsher. There’s also another epic fantasy that I’ve written Act I for that I need to finish, and more recently a sci-fi short story that apparently should be a novella, that may end up being three interconnected novellas. I’ve also some notes penned for some gothic horror short stories, or novellas, set in an alternate 1890’s Sydney.

Should they continue to sell, there is also the remainder of The Echoes of Empire to write.

Let’s say I’m not wanting for something to do.

June 21, 2015

The Sourdough Posts: A Porcelain Soul

“Poupée c 1870″ by Photo: Andreas Praefcke – Self-photographed. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...

While reading for my MA I came across a piece by Rainer Maria Rilke called “Some Reflections on Dolls”, and it fascinated me with its ideas about dolls as voids, empty spaces into which we constantly throw our affections, affections which are never returned. What does this say about how we train little girls (in particular) to love? To love hopelessly, eternally, something – and in later life, perhaps someone – who never returns our love? Just a thought.

But anyway! The jumping off point for me was this idea, and my natural writerly progression was, ‘What if this soulless, unloving thing might be given a little piece of soul? What if it might seem to be animated?’ Of course, there’s a lot of creepy doll potential there, but what if these kinds of dolls were things given to the daughters of rich men, of princes? The ultimate high-end toy with someone else’s very core inside them.

And what about the doll-makers themselves? How much might they give up to create these little monstrosities, to create things like children who suck out the very spirit and marrow of the maker, the mother-figure – what might happen if it went unchecked?

Bitsy appears in Sourdough in two other stories: she’s the child pulled away from the burning of Blodwen in “Ash”, and is seen much later in “Sister, Sister”. Selke is one of the characters in my Tor.com novella, Of Sorrow and Such, out in October 2015.

A Porcelain Soul

‘Now. Slice it thin.’

Mater Lucina’s voice is soft, barely heard in the cool of Tertiary and her tone belies what she’s asking me to do. The gossamer substance floats in a small glass box that’s been carefully placed on the beaten bronze bench top. It is the closest thing in consistency to that of a soul. Pious mothers bring newborns here and donate their babies’ breath, so we students of Tintern Doll Makers’ Academy will have something on which to practice. It doesn’t hurt the babes at all: just a few aspirations into a vial and it’s done, no one even misses it. Harmless enough ’prentice work materials for us, before we start using our own souls.

‘Slice it!’ A sharpness, because I hesitate when I shouldn’t, weighted down by the worry of failure.

So I go at it in a panic, conjure a blade and see it form inside the box. Another part of my mind holds the floss steady and I slide the knife through it, so a thin, thin piece peels off. Thinner than the soup in an orphanage, thinner than the horizon. A sliver so waif-like that for a few moments it doesn’t even know it’s been cut. It wobbles, finds itself unanchored from the clotted mass, shivers and falls with the elegance of a fainting dancer.

Shuddering with relief, I wipe the sweat from my forehead. It was better than I deserved to produce, so much better. Lucina knows it, too, and she tells me as much. Her tiny mouth bunches and puckers in irritation. I cringe, knowing that making her angry won’t help my cause.

‘For that,’ she finishes, ‘for the hesitation and a result you did not warrant, you will clean out Primary tonight.’

I stifle a groan. Primary Workshop means clay, slops, slurry, shards of fired and discarded porcelain, the broken pieces of dolls that did not make it, and all the dust and coughing that goes with it. Then there’s the dryness you cannot get out of your hands for days. But I need to be obedient, I need to be the best.

She smiles at me, not unkindly, but with a certain disappointment that hurts. ‘You have to learn, Bitsy, to be decisive and to earn what you get. You can’t simply rely on your talent to give a good enough outcome. One day your luck may run out. One day very soon you’ll be doing this to your own soul and believe me, you don’t want to make mistakes then.’

I nod, but don’t say anything. My throat feels constricted with the efforts of the afternoon. I start to clear away the tools, but Mater Lucina shakes her head. ‘Selke will clean up in here; her punishment for that mess last Sunday.’

I hide a smile. Selke slipped five homunculi in amongst the church choir. A harmless enough trick and, if anyone had paid attention, they’d have noticed the blankness on the ill-painted faces and known them for the soulless abominations they were. She set them to explode when the hymns were sung. Not all together, mind—they were timed to go off at different pitches, so through the service there were these little explosions of glitter, fabric and false flesh. And the squeaking, the God-awful squeaking they made just before they popped.

The tutors don’t like us playing with homunculi—too inhuman, they say—but Selke and obedience don’t seem to mix well. She is quite brilliant. Her toys are bizarre and dangerous and spectacular. She really shouldn’t be here; she should have gone to one of the Armourers’ Academies where she could set her mind to things that are meant for war. Truly that’s where she’d rather be, but an accident of birth got in her way. So, she’s here instead and it presents a problem for both of us.

*

It’s late when I finish Primary, and I miss dinner. Luckily the kitchen mistress likes me and I find a small basket of food waiting on the steps of the workshop when I step out. I lift the red and green cloth: a hunk of cheese, black bread, two chicken legs, a fat slice of gooseberry pie and a small skin of milk.

I pass by Secondary, its lights already extinguished (no one else required punishment this eve) and then see there is a glow from inside Tertiary.

Selke is still there. She isn’t, however, tidying.

A wolf, just a small one, barely beyond a pup, lies where the box of breath was earlier. There’s no rise or fall of its chest. It looks beautiful and sad. Beside the body is a lead coffer, about a foot square, which Selke is opening.

‘What are you—’

‘Sssssssh. Stay out of my way or help,’ she hisses. Her red curls are piled up in a haphazard mess on her head, damp with sweat, and her green eyes look through me like a cat’s.

I put the basket down and lock the door behind me. ‘But Selke, what are you . . .’ I wave my hands in despair.

‘Stand there and watch.’

I look around for something, anything to use in case this goes wrong. She drops back the lid and it gives an angry clang. Up floats a cloud of something that whirls and spins in a tight ball, like chaos barely contained. Animal souls are erratic and volatile; they have none of the calm inertia of a human one. Selke’s mind-knife appears and she takes a slice.

‘Too thick,’ I tell her. ‘Far too thick; too much anima.’

‘Shut up, Bitsy!’ She frowns and sweats as she manœuvres the piece of roiling grey to lie just above the dead beast’s chest. Then she lets it sink into the fur to dig deep into the meat of the animal. The wolf shudders, his entire body shaking as part of it becomes transparent, part of it remains solid, in a kind of incomplete decay that surely must hurt and confuse it. The creature is now half spectre, half rotting corpse, mad and in pain.

There’s no time, really, between this and when it rolls to its feet and begins snarling. Selke is frozen, transfixed by the thing she’s created. It gathers its legs beneath it to spring, every stable muscle straining, but the ephemeral sections shiver and shake as if a strong wind might blow them away.

I bring the hammer down on its head, which has, luckily for us, remained real and stout. It releases a tiny whimper and gives up the ghost one more time. The grey of the soul seeps out and slowly dissipates, freed of the spell that held it.

‘Shit,’ she says, then glares at me. ‘Now I have to start again.’ ‘Not tonight you don’t and not without a tutor here! You’re not

good enough to keep it contained. You still can’t get the balance between light and dark right. Selke, you’re amazing, but this just isn’t your skill!’

She looks set to argue, so I say, ‘Another word and I will tell your aunt—then you’ll be cleaning Primary for the rest of your life.’

Selke subsides. The last thing she wants is for Lucina to hear about this—it may tip the balance the wrong way for her.

‘Peace offering?’ I say, holding the wicker basket high. We are not bad friends, but at the heart of matters we are rivals and this causes tension. Oh, others here have their special talents—Kina can make pretend birds that sing you an aria, Lalla can paint a doll’s face so it seems to have a different expression depending on the direction from which you view it, and Talia’s soft fake foxes will curl about your feet and purr like cats—but Selke and I have, as Mater frequently tells us, the most developed abilities. Some days I think Lucina says this to make us opponents so we will strive harder. It’s worse, still, that Selke is being offered what I so desperately want when she has no desire for it at all.

‘Nice to be the good girl,’ she sneers without heat, and takes the chicken leg I offer.

‘Oh, c’mon. I’m not the one with the exploding simulacra. What did you think that would get you? Top of the class?’

She shrugs and says, ‘Still and all, it was pretty spectacular, wasn’t it?’

I have to agree. We eat in silence for a while, then she asks ‘So, has she set your final task?’

A successful graduation piece gets you admitted into the Doll Makers’ Guild and then you can find gainful employment in one of the town or city fraternities. Some might have the luck to be taken in by one of the houses rich enough and large enough to employ a dedicated doll maker. Some may take to the roads, as itinerant wanderers and makers of toys, living hand to mouth. Or some can teach—if you’re really fortunate you might be asked to join the staff of an academy, like Tintern, which may be small, with no more than forty students, but our work is respected. And we have a powerful patron, which counts for a lot.

‘A special commission. You?’

‘Well, if she lets me graduate—’

‘Avoid the exploding things and you should be fine,’ I interrupt, halving the piece of pie and sharing it. Selke will graduate whether she wants to or not

‘Shut up. The wolf—Rennak of Lodellan wants guard dogs for his cathedral.’

‘You mean . . .’ I bite down on a gooseberry and its juice is sour. ‘You’re reanimating for the Archbishop?’

She grins in a way that strikes me as obscene. ‘As soon as I can get the balance right, the slices thin enough.’

‘How does that count as toy making, Selke? If it were clock-working I’d understand.’

‘Oh, c’mon. You think your puppets are any better? I’m using existing materials to create something different. Same as you. And don’t get onto your reanimation soapbox—when you’re fully fledged you’ll put a sliver of your own soul into each doll.’ She makes a face as she, too, gets a bitter berry. ‘Anyway, you know I’m not interested in the stupid dolls.’

She never has been. If she manages the wolf then martial households will fight for her services. In fact, if she pleases the Archbishop, she’ll find a place in his grand home. That is if, and only if, Mater Lucina lets her go. ‘Besides, clockworking is unreli-able. Eventually the damned things run down, they need maintenance. The wolves are another matter entirely. Anyway, the point may be moot.’

‘Selke, she’s let you learn the art—no one else has been allowed to deviate from standard instruction—she’s letting you do the wolf. She’ll let you go.’ We both hope I’m right. If she is allowed to go, then perhaps I will be allowed to stay. Resources are finely balanced in a small academy—there is only room for equilibrium.

She shrugs, morosely. ‘What’s this special commission anyway?’ ‘A doll for Lord Holgar’s daughter.’

‘Will you use one of these?’

I look at the rows and rows of porcelain shells lining two of the four walls of the room; all empty and waiting to be filled with a tiny piece of humanity. I shake my head

‘No, I’ll start from scratch. She needs to be right. I don’t want it to be . . . easy.’ I smile.

‘You won’t have any trouble with making her beautiful.’

‘No, it will be the slivering. It will be keeping steady when I do the soul.’ I’ve made dolls before, lovely ones, perfectly gorgeous toys that we’ve sold at great profit, but the little piece of spirit inside has never come from me; one of the tutors has always done that. I know all the theory; I have done all the practice with breath; but this will be the first time I’ve worked on my own soul. Everything rests upon this. But even if I succeed, there’s no guarantee I will be given what I want.

We finish the cheese and bread then turn down the gas lights and go to the Dormitory. Before I sleep I remember that tomorrow my cousin will arrive with Lord Holgar. I have not seen Benedict for some time. I wonder if he will look different.

***