Angela Slatter's Blog, page 85

April 20, 2015

ToC The Mammoth Book of the Mummy

I’m delighted to say that the wonderful Paula Guran has taken my original story “Egyptian Revival” for her Mammoth Book of the Mummy (Constable and Robinson, Feb 2016). Thanks to Paula not only for buying it, but also for her most excellent and invaluable editing insights.

I’m delighted to say that the wonderful Paula Guran has taken my original story “Egyptian Revival” for her Mammoth Book of the Mummy (Constable and Robinson, Feb 2016). Thanks to Paula not only for buying it, but also for her most excellent and invaluable editing insights.

Here’s a taste:

Egyptian Revival

“Are you a follower, Miss Donnelly?” The voice was smoky and the question not one I’d expected.

People come to me because I find things, not because they care about which amulet I do or don’t wear beneath my shirt. They don’t give a rat’s ass what sacred name’s embroidered on my silky underthings, or whether a shrine does or doesn’t light up the corner of my fifth floor office. They come because I’ve got a proven record of locating missing people and items. Generally, the client goes home happy. Mostly, I get paid.

However, here was a possible patron, all blonde brass and Dior dress—blue and cream with a cinched-in waist and matching swing coat—wanting to know if I was a follower. I pushed a stray curl behind my ear, and played dumb.

“Of what, Mrs. Kolchak? Fashion?” My functional green skirt and simple white blouse plainly said “no.” My custom-made Mary Jane pumps with the steel caps in the toes said, “Hell, no.”

“Of the gods, Miss Donnelly,” she answered evenly. Her teeth were so neat they looked pressed. Then, as if I’d given an affirmative answer, she continued with, “And of which ones?”

She herself wore no talisman, giving no hint as to what I should say, so I went with the truth, which wasn’t entirely a new thing for me, just not necessarily my first port of call.

“I don’t follow a god, Mrs. Kolchak. Didn’t follow any of the ones around before the Egyptians came back into style; don’t follow this latest crop; can’t imagine I’ll be following the next craze either.”

“You’re an atheist?” She arched one perfect eyebrow, but it didn’t seem to make any of her skin wrinkle at all. Neat trick.

“Call me an agnostic realist. Whatever’s out there probably has bigger things to worry about than the billion importuning prayers sent up—or down—every day.”

My potential source of income bit at her pouty lower lip, as if considering my future, and I silently cursed the human mania for hitching hopes and dreams to invisible friends. Fifty or so years ago, when the dead-but-determined-not-to-remain-so Queen Tera managed to resurrect herself with the aid of the Jewel of the Seven Stars, Egyptian religion underwent a revival—how could it not? Forgotten gods found a foothold once again; prayers of the sometimes barely convinced faithful thundered from freshly erected temples, and the pantheon of Kemet made a place for itself among all the other belief systems as if it hadn’t been gone longer than five minutes—especially here in San Francisco where outré is normal. Me, I think religion’s like adding rocks to a body of water: the liquid just shifts around, displaces, to accommodate whatever’s added. No one really notices when it disappears either, though most people don’t admit that.

The restoration didn’t matter one whit to someone like me, but to those further up the economic and social ladder it mattered a lot. If you wanted a certain job or promotion, membership in a particular club, the right house in the right part of town, then your choice of personal divinity could make all the difference. Small fry and ordinary folk mostly held to their Holy Trinity credos, Torahs, Buddhist chants, or what have you, but those with cash and position were happy to pay lip service to the new-old ways, and their willingness to do what was needed to prove devotion could, and did, open doors.

Still Amun, Ra, Osiris, Isis, Sekhmet, Hathor, and all the rest held some sway over popular imagination. The pseudo-Egyptian-style portion of the Memorial Museum that had been torn down in 1929 had been rebuilt to house a permanent collection of ancient Egyptian artifacts, replicas, exhibits, papyrus, coffins, and, of course, mummies—both human and animal. Among the latter there was even an enormous mummified Nile crocodile. Cynics had noted, though, that since Queen Tera’s show-stopping return performance no more ancient royalty had been revivified and there’d been precious few miraculous displays. The deities of the Two Lands were apparently unwilling to intervene on the behalf of those who were now devoted to their rituals, wore their amulets, and burned boatloads of incense in their worship.

Or maybe the gods just didn’t make public spectacles of their divine works.

At any rate, Mrs. Kolchak finally nodded and said, “Perhaps you’re just what I need. No conflicting beliefs.”

Full ToC:

Kage Baker, “The Queen in Yellow”

Gail Carriger, “The Curious Case of the Werewolf That Wasn’t, the Mummy That Was, and the Cat in the Jar”

Paul Cornell, “Ramesses on the Frontier”

Terry Dowling, “The Shaddowes Box”

Carole Nelson Douglas, “Fruit of the Tomb”

Steve Duffy, “The Night Comes On”

Karen Joy Fowler, “Private Grave 9”

Will Hill, “Three Memories of Death”

*Stephen Graham Jones, “American Mummy”

John Langan, “On Skua Island”

Joe R. Lansdale, “Bubba-Ho-Tep”

*Helen Marshall, “The Embalmer”

Kim Newman, “Egyptian Avenue”

Norman Partridge, “The Mummy’s Heart”

Adam Roberts, “Tollund”

Robert Sharp, “The Good Shabti”

*Angela Slatter, “Egyptian Revival”

Keith Taylor, “The Emerald Scarab”

Lois Tilton & Noreen Doyle, “The Chapter of Coming Forth by Night”

April 19, 2015

Dead Funny: An Interview with Johnny Mains

British author and editor Johnny Mains took some time out of his busy schedule to answer a few questions about horror writing, films, his literary influences and encountering the odd publishing industry wanker. His first Best British Horror for Salt Publishing was an outstanding anthology, gathering the talents of Ramsey Campbell, Muriel Gray, Gary Fry, Tanith Lee, Mark Morris, Thana Niveau, John Llewellyn Probert, and Michael Marshall Smith, among others.

What do readers need to know about Johnny Mains, writer and editor?

I’m deeply committed to the genre.

I thoroughly enjoy what I’m doing – I love editing, I adore writing and I’m appreciative of all of the offshoots – writing liner notes for blurays, having stories turned into comics, movies, audio recordings. Most of all I find it a deep honour promoting the genre and trying to get it back out there to a mainstream audience who have, on the main, fallen out of love with it. Because I’m a fanboy at heart, and will remain a fanboy until they dump me in a lime pit.

Progress is being made – but I’m continuously irate that bookshops still don’t seem to be stocking horror in the quantity that fantasy and science fiction books are.

Which of your books would you recommend to a new reader?

What book of mine would I recommend to a reader? I wouldn’t – not to say that I think any of mine are bad; but in the interests of genre promotion I think everyone should go out (if you haven’t already) and buy Nathan Ballingrud’s North American Lake Monsters which is possibly the greatest debut collection that’s been published in the last 20 years. An unbelievably crafted work, and it’s not often you feel a book is an honour to read – but two stories, ‘Sunbleached’ and ‘The Good Husband’ launch the book into that territory.

Tell us about editing the Remains novella series for Salt Publishing.

Well, so far there’s been one book, the classic Twisted Clay, by Frank Walford, which had been out of print for over 40 years. I’ve been working like the clappers on the next books that are up and coming – works by V.H. Leslie, John Llewellyn Probert and Laura Mauro. It’s been rather cool editing these – completely out of my comfort zone as I’ve only ever edited short stories – so when you have a piece that’s 25k and up, it’s a whole new discipline and a steep learning curve. I’m having a load of fun doing it though, and those three books should be out by this summer.

Who were/are your literary heroes/influences?

My literary heroes and influences are the authors who appeared in all of the Pan, Fontana, Mayflower, Panther, Sphere, Target, Tandem and NEL anthologies I read when I was growing up. Whilst there were a few famous names popping up here and there, James, Aickman, Poe etc – it was always the same stories appearing time and time again, so it was to the journeyman author I turned to; names such as Conrad Hill, Roger Dunkley, Alex White, Bryn Fortey, Mary Danby, Roger Malisson, Rog Pile etc. My writing has a decidedly 70s feel to it, which I like to think is charming – but am aware that it probably kills the appeal of my books stone dead for those who like their horror literary, obscure and without humour.

What draws you to horror?

When I was growing up I was always an outsider, and I think horror drew me in because nobody at school was into it, and I was the only one who would read all of the Stephen King books during lunch break in the library – and of course that love for horror cast me out even more, because I was seen as weird and I was bullied a lot at school. But I found comfort, felt at peace – I loved reading a book of such pure horror and knowing I would come out of the other end unscathed.

Why am I still a fan of horror? I find it a very interesting genre to study; it’s the only one that truly explores the dank depths of which one can plummet to and I just don’t think you find the consistent reinvention of the wheel as you do with horror.

You recently wrote the Introduction to Stephen King’s Thinner – how was that as an experience?

You recently wrote the Introduction to Stephen King’s Thinner – how was that as an experience?

It was fraught. It’s Stephen King! I re-read Thinner about four or five times and tried to write a few drafts but nothing seemed to work. I emailed Ramsey Campbell and asked him if I could see the intro he had written for Pet Sematary, and as soon as I read the first two lines I knew where I was going wrong, changed the tone of the piece and wrote it in one go and it was perfect.

The finished book is beautiful. It includes some amazing paintings by Les Edwards and it’s an honour to be asked, be a part of and is indeed one of the proudest genre moments of my life!

What’s your favourite Hammer Horror film and why?

Easy peasy! Plague of the Zombies. It has to be, followed closely by The Snorkel. I love Plague of the Zombies because it’s so joyous. Everyone appears to be having a lot of fun doing filming it. Nice decapitation, furious drumming, voodoo antics, and a burning set. What’s not to love!

You’re editing the second volume of Best British Horror for Salt – what made you want to put this kind of collection together?

Salt approached me in 2013 and asked if it was something I would be up for doing. I had a chat with Nicholas Royle, my friend and editor of Best British Short Stories who told me that I should go for it. The first book was a pleasure to work on – and it was truly eye-opening to see what talent we have in the UK. Up until I started working on the books my reading consisted of everything up until 1989 – this was mainly down to the fact that there was so much in the genre I had to read and catch up on, and also wary about what was happening in the genre currently – and I didn’t want my own stuff to by subconsciously tapping into whatever happened to be ‘on trend’.

The first book had some great press and a slow build-up of sales and I’m currently finishing up the second book, which is slightly behind – but hopefully will be coming out in the next few months. It’s a great honour to be heading up a series of books which is your own personal stamp on how you see the state of the genre and hopefully it is a gateway for people discovering authors for the first time and hopefully trying their hand at writing themselves and getting into the small press the same way I did when I used to devour Stephen Jones’ Best New Horror when I was trying to break into the small press in 2008.

How was the experience of putting together Dead Funny: Horror Stories by Comedians with Robin Ince?

Working with Robin was a dream and working with the comedians was a brilliant experience as well, on the main. The trouble I had on quite a few occasions was working with the agents. They are a bunch of mercenary bastards – and they have to be, that’s their job. But I lost two authors through their agents being absolute wankers. I won’t mention names, but if I ever saw them I would probably knock them out. The ones I had trouble with were rude, unprofessional and probably hadn’t been laid since the 80s.

However the end result was a book that is my crowning achievement so far. We are about to start work on Dead Funny 2 – and I really do think we have a good chance at topping what we did with the first book.

You also seem to be doing a lot of work with film at the moment – recording commentaries and writing liner notes for bluray releases – how did that come about?

You also seem to be doing a lot of work with film at the moment – recording commentaries and writing liner notes for bluray releases – how did that come about?

It’s an area I wanted to break into for quite a while – I don’t just want to be known as the person who writes short stories and edits anthologies. I’m a ferocious film viewer, I try to watch one or two films a night and whilst I read only horror – I watch absolutely everything I can get my hands on.

Marcus Hearn gave me my first taste – he asked me to do a piece to camera on John Burke for the Rasputin bluray and since then I’ve done bits for The Sorcerers, Happiness of the Katakuris and am writing liner notes on Horror Hospital and La Grand Bouffe. I find it stretches me and I really do enjoy writing non-fiction pieces. There’s nowhere to hide when you write them – you have to do your research and do it well. Long may it continue!

What’s next for Johnny Mains?

This year I’m concentrating on writing The Pan Book of Horror Stories Scrapbook – that’s coming out this December and the amount of hours I’m putting into it is extraordinary, but I think it’s going to be an absolutely stunning book when it comes out. I also have Best British Horror, my Aickman tribute anthology and Dead Funny 2 out this year as well. As to my own writing, I have my third collection out in October. Lots of fun. Lots of words!

April 17, 2015

Review: The Female Factory

The wonderful Amanda Wrangles has reviewed The Female Factory (which won the Aurealis Award for Best Collection last week, didn’t ya know?) over at Marianne de Pierres’ most excellent and eclectic site.

The wonderful Amanda Wrangles has reviewed The Female Factory (which won the Aurealis Award for Best Collection last week, didn’t ya know?) over at Marianne de Pierres’ most excellent and eclectic site.

As the latest joint offering from super-star writing duo Angela Slatter and Lisa L. Hannett, The Female Factory lives up to all expectations we’ve come to expect from these two wicked masterminds.

Four novellas stitched together with the common theme of our innate need to reproduce, belong, love (and be loved); along with the often frightening lengths humans will go to in their craving to do just that.

For the rest, click here.

April 16, 2015

In which there is dancing and a book deal

I had no appropriate pic, so went for Kathleen’s suspicious-looking fox

A three book deal to be precise.

As I’m given to understand (by a very reliable source) that this info has been released at the London Book Fair this week, I can no longer keep my trap shut: I’ve signed a three book deal with the delightful Jo Fletcher Books (so, Hachette International). The Verity Fassbinder series is based on the short story “Brisneyland by Night”, which first appeared in Sprawl by Twelfth Planet Press.

The first book, Vigil, will be out in 2016 in a European summer (which I take to mean around about May, but as the weather seems to be moving backwards possibly September), with Corpselight and Restoration to follow in 2017 and 2018. There’ll be garbage golems, witches making wine from the tears of children, sirens, angels who really don’t like humanity, soothsayers, and coffee and cake. Lots of coffee and cake.

“Brisneyland by Night” has been reprinted in Paula Guran’s The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy and Horror 2011 (from Prime Books), and online at Lightspeed Magazine http://www.lightspeedmagazine.com/fic... – should anyone want a hint of what you’ll be getting (it’s not Sourdough, be warned, so not Sourdough).

The deal was negotiated by my Most Excellent and Sartorially Overachieving Agent, Mr Ian Drury of Sheil Land. More details as official things come to hand.

As this comes at the end of a week that started with three Aurealis Awards, my natural writerly pessimism is kicking in, so I’m now going to sit in a corner and watch for rain.

April 15, 2015

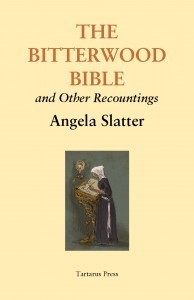

The Bitterwood Posts: Spells for Coming Forth by Daylight

This is my last Bitterwood Post – I’m a little sad now.

This is my last Bitterwood Post – I’m a little sad now.

The title for this story came when I was visiting an Ancient Egyptian exhibition at the Queensland Museum with my mother and sister. One of the guide notes on the wall talked about The Book of the Dead and how an alternative name for it was The Book of Coming Forth to Daylight, and speaks of ‘spells for coming forth by daylight’. So I loved the phrase and the idea of books containing spells – as you might well pick up from the number of magical books in this tome!

I wanted to bring the book full circle, back to dear screwed up old Hepsibah Ballantyne, who’d lived well beyond her span by fair means and foul, and also to wrap up the tale of the blond man who, as Sister Goda wrote in “Terrible As An Army with Banners”, ‘ghosts through our folios like a virulent breeze’. They had a tenuous connection is their early lives, and they’ve both moved through the world of Bitterwood seeking their own ends and leaving ruin behind. I wanted to clear up a few mysteries and create a few more, coz that’s how these books roll.

But I also needed someone to tell this story, and I wanted it to be a first person narrator for this last tale: who better to hear from than Nel? A new girl, changed by the magic left on her dead sister’s skin, made more than she had been, yet with her oldest protection, her invisibility, removed. How might she cope, what might she think? She’s travelled so far for revenge, to fulfil the promise she made to herself and her family. She’s the perfect person to be there and witness the final collision of Hepsibah and the Viceroy.

The other thing I wanted to do with Bitterwood was bring the narrative to Lodellan. Sourdough is all about the cathedral-city and its environs, but Bitterwood begins elsewhere and ends in Lodellan. In The Tallow-Wife and Other Tales, the book starts in the city and then moves away. When the three books stand together, there will be a distinct sense of shift. No one else will notice; it’s just me amusing myself.

Spells for Coming Forth by Daylight

Four years, I think, refusing to believe it and so speak out loud: ‘Four years.’

The folk milling around me in Half-moon Lane’s broad expanse barely notice and those who do are adept at looking elsewhere. Steady, Nel, I think. This is the area of Lodellan where people know how to mind their own business ? if they know what’s good for them ? which is in part why I sought it out. Also, it’s cheaper to find a bed here, to eat once a day ? should I so desire I can feel my ribs, count them with ease ? and to go unremarked unless I fail to pay my bills.

Alas, that’s becoming an all-too-likely event. Four years and the money, the valuables, have just about run out. I sold the last of the tiara gems almost twelve months ago and have been living frugally on the proceeds since. I bartered away the clothing, too, all those lovely travelling dresses, even Asha’s favourite dove grey; now the only thing between me and public indecency is a well-worn pair of trews, an equally lived-in shirt, boots with emaciated soles (enchanted to keep my footsteps quiet), and a cloak grown thin with age ? I’ll be in trouble by the time winter comes. All in varied shades of brown, for brown turns aside the eye, excites no attention, and since my face changed, became more pleasing, I have been so anxious not to be noticed. The camouflage does seem to work, although crowds part when I walk through them even if no one seems to see me. Sometimes I wonder about this, but mostly I simply accept it as bonus of whatever magic rubbed itself on my skin. After the second year of fruitless searching, I sent the driver and coach back to Breakwater, and began walking the length and breadth of whichever land, county, country, the bloodstained pin directed. I’ve crossed mountains and oceans, marshlands and forests, borders and boundaries, followed faithfully to where it led, and look what it’s gotten me: permanently calloused feet, a tan that will never fade, wrinkles like canyons at the corners of my eyes, and hip joints that grind with every step. Perversely, I never thought I’d bewail the loss of what Asha passed on, never thought I’d be concerned for my looks, but it’s strange: when suddenly you get something you never thought to have, never thought you’d care about, it becomes so stupidly precious. I never thought I would be that way. I never thought I would miss the smell of the sea, the stink of the port, the heady sweet miasma of home. I never thought I would miss the house by the Weeping Gate.

Alas, that’s becoming an all-too-likely event. Four years and the money, the valuables, have just about run out. I sold the last of the tiara gems almost twelve months ago and have been living frugally on the proceeds since. I bartered away the clothing, too, all those lovely travelling dresses, even Asha’s favourite dove grey; now the only thing between me and public indecency is a well-worn pair of trews, an equally lived-in shirt, boots with emaciated soles (enchanted to keep my footsteps quiet), and a cloak grown thin with age ? I’ll be in trouble by the time winter comes. All in varied shades of brown, for brown turns aside the eye, excites no attention, and since my face changed, became more pleasing, I have been so anxious not to be noticed. The camouflage does seem to work, although crowds part when I walk through them even if no one seems to see me. Sometimes I wonder about this, but mostly I simply accept it as bonus of whatever magic rubbed itself on my skin. After the second year of fruitless searching, I sent the driver and coach back to Breakwater, and began walking the length and breadth of whichever land, county, country, the bloodstained pin directed. I’ve crossed mountains and oceans, marshlands and forests, borders and boundaries, followed faithfully to where it led, and look what it’s gotten me: permanently calloused feet, a tan that will never fade, wrinkles like canyons at the corners of my eyes, and hip joints that grind with every step. Perversely, I never thought I’d bewail the loss of what Asha passed on, never thought I’d be concerned for my looks, but it’s strange: when suddenly you get something you never thought to have, never thought you’d care about, it becomes so stupidly precious. I never thought I would be that way. I never thought I would miss the smell of the sea, the stink of the port, the heady sweet miasma of home. I never thought I would miss the house by the Weeping Gate.

This city is landlocked, although there is a river running through and around it ? it does  not seem to have a name, just “the river” ? and in the weeks since I’ve been here I have sat by its banks with my eyes closed, trying to persuade myself that the sounds of its rushing waters are like the gentle splash of waves breaking against the pylons of the wharves in Breakwater’s harbour. Some days I am almost convinced; mostly I’m not.

not seem to have a name, just “the river” ? and in the weeks since I’ve been here I have sat by its banks with my eyes closed, trying to persuade myself that the sounds of its rushing waters are like the gentle splash of waves breaking against the pylons of the wharves in Breakwater’s harbour. Some days I am almost convinced; mostly I’m not.

This city is both old and new, its foundations deeply embedded in the past, its encompassing walls thick and ancient, built to house a smaller community in more generous surroundings, but the population has grown as populations are wont to do, and begun to fill the space. Not fully, no, but everything fits more snugly within the series of squares that make up the burg, will become more snug still as time passes. The palace of the local prince and his most recent bride is being extended, extra wings added to house who-knows-what, gardens improved upon and expanded, planted with ever-more exotic foliage that require ever-more gardeners to ensure they do not die in alien soil. And there is a magnificent cathedral being build to replace the tiny church that once was sufficient for the needs of the worshipful, but now no longer meets the requirements of either size or prestige. The Archbishop is apparently anxious for his holy accommodations to reflect his status. I passed by the building site last week, looked down into the great abyss they’d hollowed out, saw all the tunnels that will form catacombs and secret places, and shuddered.

This city, I fear, is the last place I have any hope of finding the Viceroy.

This city, I fear, is the last place I have any hope of finding the Viceroy.

I seemed always to arrive too late. Sometimes it would be obvious he had been there before me ? talk in the hostelries and marketplaces would be of a sudden abundance of murders in locales barely touched by such events, or of items of esoteric value disappeared or stolen. Yet when I described the man I sought no one would, or indeed could, tell me they had seen him. It made me wonder what new magic he had learned, to wipe people’s minds so clear. Then again, perhaps he simply has not shown himself for whatever reason, perhaps his peculiar golems have been carrying his will into the world?

At any rate, I have not found him, have not caught up with him ? at least until now. The  bloodstained pin from Asha’s wedding tiara ? just the pin itself, mind you, the diamond at its apex was the last thing to go ? did something it had not done before when I wandered into Lodellan: it stood straight up, balancing vertically in the palm of my hand. It has spun madly, spun slowly, lain dormant, but it has never done this ? indeed it stands to attention still, on the rickety desk in my room in the boarding house ? and I choose to see in this novelty a sign. That the end is here, that my road will be done, that Asha and Iskha and all the others will be avenged, that the danger of the Viceroy will be gone from the world, and that I will be free. I am unsure what I will do then ? the threat of liberty has always seemed so far away.

bloodstained pin from Asha’s wedding tiara ? just the pin itself, mind you, the diamond at its apex was the last thing to go ? did something it had not done before when I wandered into Lodellan: it stood straight up, balancing vertically in the palm of my hand. It has spun madly, spun slowly, lain dormant, but it has never done this ? indeed it stands to attention still, on the rickety desk in my room in the boarding house ? and I choose to see in this novelty a sign. That the end is here, that my road will be done, that Asha and Iskha and all the others will be avenged, that the danger of the Viceroy will be gone from the world, and that I will be free. I am unsure what I will do then ? the threat of liberty has always seemed so far away.

I make my way along Myrtledove Walk, a tiny byway that leads, as if by magic, to the better part of town. It seems that I step across an enchanted threshold into Busynothings Alley. While the street is a little narrower than its downmarket, more criminally-inclined counterpart, the stores here are fancier, tidier, their signs freshly and artistically painted, emblazed not merely with a drawing of the service offered, but also with the written description beneath. I would feel out of place if I thought myself more conspicuous; as it is I am a brown smudge of a woman, with a hood pulled low over my face, and a heavy satchel concealed under my cloak.

I think what it would be like to be here with the weight of excess coins in my purse, wearing a pretty dress ? not a hand-me-down, but something made just for me ? and wandering about with little else to do. No burden of obligation on my shoulders, no thoughts of home and my sisters and Dalita, no thoughts of last chances and all the tiny failures that have dotted my past forty-eight months. I think about all that and shake my head for such thoughts gain me nothing. I see the sign for Gisborne Street and hurry down it until it intersects with Whortleberry Lane, my destination.

I think what it would be like to be here with the weight of excess coins in my purse, wearing a pretty dress ? not a hand-me-down, but something made just for me ? and wandering about with little else to do. No burden of obligation on my shoulders, no thoughts of home and my sisters and Dalita, no thoughts of last chances and all the tiny failures that have dotted my past forty-eight months. I think about all that and shake my head for such thoughts gain me nothing. I see the sign for Gisborne Street and hurry down it until it intersects with Whortleberry Lane, my destination.

Ermingard, the proprietress of the Loathly Lady, the boarding house of which I am currently a well-tolerated patron, is a source of valuable information if one can but get her to open her mouth. She knows more useful secrets and is in charge of more nefarious things than she will ever admit, but after I rendered her a small service ? Lil’bit would be pleased to know I have not lost my touch with a lockpick ? she has seen fit to answer my queries about the best place to try and sell a book of rare sort (ancient, black-covered, and smelling of badger). The purveyors of fine tomes to which I’ve been directed are, Ermingard assures me, both trustworthy and discreet.

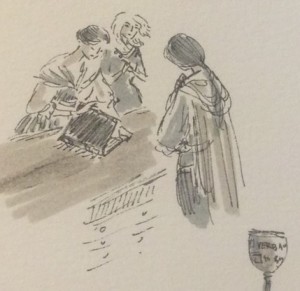

Carabhilles’ Fine Books is located halfway down the lane, a gem even among so many other finely appointed bookstores. The shingle depicts a book with legs, which makes me laugh aloud for the first time in an age. The windows of the shop are clean and sparkle brightly in the afternoon sun. Through them I can see shelves and shelves, rows of tables and desks, piles of volumes neatly stacked awaiting inventory and placement. Well-dressed men, women and children moved about inside with the polite greed of bibliophiles.

I take a deep breath and push the door, which makes the bell on the lintel give a genteel cry of alarm. Heads turn and take me in ever so briefly, then, having summed up my worth and found it wanting, they all return their attention to the things most deserving: the books. Or rather all but one: a youngish woman, not quite twenty, with light brown hair and angry amber eyes, is still staring at me as if that will send me back to whence I came. I shake off my hood and give her a bright smile in answer and nod to say I’ve seen her and yes, I will speak with her. I peel away the edge of my cloak so she can see the satchel beneath, see its size and estimate its heft. So she can imagine what might lie therein and her curiosity is caught, outweighing her annoyance. I was once not this manipulative, this set on getting my own way; I wonder what I would have been like had Asha’s death never happened. A mouse, I suspect, a shadow all my life.

The woman moves towards me, her saffron gown flouncing with each step, and I towards her so we meet in the centre of the front room. Behind the counter from which she’s just come stands another girl, younger still and wide-eyed, this one with white-blonde hair, a green gaze and a dress of amethyst hue that speaks to the prosperity of this establishment. I’d have thought they would look alike, for they are supposed to be sisters, but there is nothing to show a shared blood ? I wonder which one takes after their mother?

‘How may I assist?’ Amber-eyes asks tightly.

‘I wish to discuss the sale of a book.’

‘You wish to buy a book?’ Her expression says quite clearly I cannot afford even a bowl of soup.

‘You wish to buy a book?’ Her expression says quite clearly I cannot afford even a bowl of soup.

‘No, I wish to sell one to you.’

‘What makes you think we’re interested?’

‘We’ll neither of us know until you look at it, but Ermingard at the Loathly Lady said you might be. She said the Carabhilles could be trusted ? I do hope her faith has not been misplaced.’

She doesn’t bother to answer but waves a hand in a gesture that might mean follow me or something less polite. I am an optimist after all, so I choose the former and trail her further into the room, to a narrow polished table with a purple velvet runner down its middle. I open the satchel and extract the big black book, careful not to disturb the other item in there, and place it on the velvet, where it looks like a magnificent rock of a thing. The woman’s eyes widen as she reads the front cover ? Murcianus – Magica: A Book of Craft ? then tries to hide her shock by turning away and rifling through a drawer to find a pair of white cotton gloves. When she faces me again she is mostly composed. If I had not watched her so closely, I’d think the gloves were to stop the musky badger scent from getting on her dainty hands.

‘This is old,’ she says, voice husky. She carefully opens it, gingerly leafing through each page, then pauses ? she thinks I don’t notice how her right hand slides beneath the back cover looking for the indentation, the M I already know is there. Her fingers rest on it, caressing the relief lovingly. How can she think I don’t notice? What is this thing that all her caution, all her sangfroid evaporates like morning dew in the sun? I can only hope it means I will get a good price for it ? I have no interest in keeping it, I cannot read the language in which it’s written. It is a means to an end for me, to finance the final leg of this journey. Or at least to get enough to pay Ermingard for a bed for the next few weeks and to ensure a meal or two a day for that long. Perhaps enough for a new pair of stout boots and a new cloak that will see me survive winter. The more I think about it the more my list of needs grows, so I put the expectant anticipation from my mind.

‘I will need to value this before we can discuss any sale,’ she says. ‘My mother and sister will need to be consulted, too, so we might reach an agreement. Will you be so kind as to leave the book with me and return this afternoon?’

I snort. ‘I’m sorry, have I given the impression that I’m some sort of lackwit? I will not leave this volume here, no. I will wait for you and yours to do a valuation under my watchful eye, or I shall take the tome with me and see what other merchants in this street of books will offer for it.’

She looks as if I’ve slapped her. I take the heavy item from her seemingly nerveless hands and put it back into the satchel, then draw my cloak around it and myself and make to leave. Her fingers grab at me, hard into the flesh of my upper arm.

‘No!’ she almost shouts, then realises that her well-heeled clientele are staring. She lowers her voice and loosens her grip. ‘No, please. Come in and wait.’

I pause for a long moment before nodding. I follow her through the stacks of polished oak, the beautifully bounded books all lined up like pretty maids, until we come to the back wall, which seems to be simply more book-lined shelves, or so I think. She touches a bright red spine with Beata Beatrix in gold lettering and there is a stealthy click. The wall swings back a little. She pushes it open and stands aside, showing I should go first.

And I do for, after all this time, I am apparently an idiot.

As soon as I step into what appears to be a dining room of moderate extravagance, arms snake around me and sharp steel is cold against my throat.

As soon as I step into what appears to be a dining room of moderate extravagance, arms snake around me and sharp steel is cold against my throat.

‘Is this how you do business?’ I say, trying to keep my voice steady. I can feel her hand shaking and the knife with it. She may well cut me through sheer nerves rather than intent, and that would be contrary to my desires. I have a dagger, too, slim and slender, and concealed at my hip, but I’m in no doubt that brandishing it will be counterproductive.

‘You wanted to wait,’ she hisses. ‘So you will wait until Mother returns.’

There is a medium sized table and she pushes me into a chair at one end, then takes up position at the head. Not exactly the best means of controlling me ? and if the shoe had been on the other foot, I’d have tied me up ? but then I’ve just shown myself stupid enough to give her the advantage, so what do I know? We sit in silence for a good few minutes, I rubbing my neck where it feels as if the cold of her blade has seared me.

‘Where’s your mother and when might she grace us with her presence?’ I ask and she remains silent. ‘Only, I’ve got somewhere else to be this afternoon …’

Still she does not answer, but glares at me as if she might be able to ignite my hair or eyebrows. The door in the wall opens and the other girl enters.

‘Where are you, Cassia, leaving me with all those customers …’ she trails off and stares at us. ‘What are you doing?’

‘She has the book, Flavia ? Murciana’s great book!’ Her amber eyes are bright as fire. The younger girl turns sceptical eyes on me, and Cassia raises her voice, ‘In the bag! Under her cloak. Get it, examine it!’

The other girl appears doubtful and I feel it’s time to establish some boundaries, crossing my arms over my chest. ‘If you come near me, I promise you broken fingers at the very least.’

That seems to decide matters ? no hardened criminals or standover merchants these, just  angry frightened children at heart. What are they hiding that makes them so fearful? A professional would have cut me a little, taken off a slice of flesh to encourage me to talk ? and I would have! ? but neither of them are certain of themselves. They have no ruthless disregard for life.

angry frightened children at heart. What are they hiding that makes them so fearful? A professional would have cut me a little, taken off a slice of flesh to encourage me to talk ? and I would have! ? but neither of them are certain of themselves. They have no ruthless disregard for life.

‘Tell me where you got it?’ Cassia almost begs.

I give her a long look, compressing my lips and narrowing my eyes. ‘Since you were not polite enough to answer my questions, I will not answer yours. We shall wait for your mother to return ? oh, and I’d suggest at least one of you goes back out to the shop floor. I didn’t like the look of some of your customers for all their fancy attire, and books ? well, we’ve ample evidence that they make people crazy.’

And so we wait.

***

April 14, 2015

Talking writing stuff …

… over here I chat with the lovely Tarran for Collins Booksellers. A snippet:

… over here I chat with the lovely Tarran for Collins Booksellers. A snippet:

What inspired you to start writing and what motivates you?

I always loved reading as a kid and after lights out I’d tell myself the stories that had been read to me over and over before I slept. I’d think about them and pull them apart ? maybe I was actually a budding editor! ? and then tell them differently, especially if I hadn’t liked the ending. I’d always scribbled, but didn’t make the decision to give writing a proper bash until I was 37 ? I didn’t want to hit 40 and feel I’d never tried to live my dream. I’ve been working at it ten years now, and I still love it, despite the poverty. There are all these stories and characters living inside my head ? if I don’t write about them, they get grumpy.

Ian McHugh: Sprinkling the Angel Dust

Australian spec-fic writer Ian McHugh’s debut short story collection, Angel Dust, was one of the finalists for this year’s Aurealis Awards for Best Collection – and it’s available here from Ticonderoga Publications (and you should go and get a copy). He’s sold stories to professional and semi-pro magazines, webzines and anthologies in Australia and internationally, and he’s won (well, his stories have) grand prize in the Writers of the Future contest, as well as the Aurealis for Best Fantasy Short Story in 2010. He’s also a Clarion West graduate – here he talks about writing, beer, and crass opportunism!

Australian spec-fic writer Ian McHugh’s debut short story collection, Angel Dust, was one of the finalists for this year’s Aurealis Awards for Best Collection – and it’s available here from Ticonderoga Publications (and you should go and get a copy). He’s sold stories to professional and semi-pro magazines, webzines and anthologies in Australia and internationally, and he’s won (well, his stories have) grand prize in the Writers of the Future contest, as well as the Aurealis for Best Fantasy Short Story in 2010. He’s also a Clarion West graduate – here he talks about writing, beer, and crass opportunism!

1. So, what do new readers need to know about Ian McHugh?

Buy me a beer and I’ll be your friend. Buy me two and I’ll follow you around to see if there’s any more. My first short story collection, Angel Dust, was published by Ticonderoga Publications in late 2014. It brings together about a third of my published stories to date. Most of the rest – and a few of those in the book that are archived at online magazines – are posted on or linked from my website, for anyone who might like to try before they buy.

2. What was the inspiration behind your new short story collection, Angel Dust?

Crass opportunism? Russell offered and I said yes. There’s four original stories in the book, but the rest are reprints, so it’s one of those books that kind of unintentionally accumulated over time until someone (Russell) came along and said, “Ooh, I reckon there’s a book in that lot, and I’m the person to publish it.” That being so, there are a few recurring themes. Angels are one that immediately leapt out to Russell – hence the cover and the title. If I was to let my inner wanker become my outer wanker for a moment I might say that “a recurring motif in my work is that of the angel, both literally and in the form of redemptive proxies that inspire my protagonists” or somesuch. A more honest answer might be that I appear to have a fetish for shiny ladies with wings.

As you’d know, when you write, bits of yourself sneak into your stories that you didn’t really intend, and you only realise what they are, and what you’ve exposed, after the story’s published and it’s far, far too late. One of the things that keeps cropping up for me is my apparently boundless anxiety about being a good man – not just a good person, but a good man, and what that means. So a number of my stories revolve around men who are failing at that. (The whole book isn’t just a repetitive meditation on neurotic masculinity, mind you. There’s fun stuff, too. Sometimes even in the same story.)

3. What attracts you to the darker side of fiction?

In my own work, I actually have to say “accident”. I really don’t feel like I have a strong understanding of what makes good dark fiction or horror. Science fiction or fantasy I can pull apart and figure out what makes them tick and replicate that reasonably reliably. Horror for some reason eludes me. Mostly I just try to put my characters through the wringer – make them suffer, threaten them, damage them. Nothing more than trying to generate tension and drama, really. If I just do that, the stories tend to go dark without me really meaning them to, and it seems to work – most years I manage to have at least one story honourably mentioned for Ellen Datlow’s year’s best. But if I try to write a horror story on purpose (eg, for Ellen, on the couple of occasions I’ve been invited to submit to her anthologies) the result is just embarrassing.

In what I read, I don’t have a particular attraction to stories that get dark. You’ll see in my answer below that my influences are all over the shop. For my taste, for a story to go dark and stay there, and still be fulfilling, that’s some really good storytelling and it’s probably the quality of the storytelling, rather than the darkness of the story, that attracts me. A friend recently leant me Nathan Ballingrud’s North American Lake Monsters, which could be subtitled “Nine Vicious Gut-punches”. Dark? Oh my. But it was the storytelling and the living, breathing, awful reality of the characters and their places in the world that kicked my arse rather than the horror elements.

4. In general, who and/or what are your writing influences?

Many, many, many. So, so many. So for the purposes of this answer I’ll just stick to fiction writers: My first speculative fiction novels were Magician, The Sword of Shannara and The Lord of the Rings, in that order. I still have my loved-to-bits copies of all of them from when I was twelve or thirteen. (The Fellowship of the Ring has the pages at either end of the Tom Bombadil bit permanently dog-eared to not read.) On top of that uniformly high fantasy foundation, my first really formative influences were Glen Cook, CJ Cherryh and Diana Wynne Jones. Cook was one of the early adopters of the kind of ‘gritty’ fantasy that people like George RR Martin and Joe Abercrombie have taken and run with. I love Cherryh’s science fiction for how she tells really intimate human stories in hard SF or space opera settings. DWJ I love for the way she revelled in taking the piss out of genre tropes.

There’s a bunch of individual books by other writers that I would point to as having really strongly affected me, too, for various reasons: Dune, Helliconia Spring, Neuromancer, American Gods, Catch-22, All Quiet on the Western Front, The Big Sleep, The Siege of Krishnapur by JG Farrell, China Mountain Zhang by Maureen McHugh, The Stone Ship by Peter Raftos, The Anubis Gates, Ender’s Game, Red Mars, Get Shorty, Fight Club, The Dispossessed, Neal Stephenson’s Quicksilver, Jose Saramago’s The Stone Ship and Death With Interruptions, Celestial Matters by Richard Garfinkle, Travel Light by Naomi Mitchison. I think Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice will go on that list too. It’s the first book in a long time that has so completely blown my mind.

With short stories, my focus is very narrow – it’s all about individual stories, or at most particular collections, rather than certain authors or wider bodies of work that affect how I approach short stories. Things like: “The Wonderful Ice-Cream Suit” and “The Day It Rained Forever” by Ray Bradbury, “The Glass Woman” by Kaaron Warren, “If Lions Could Speak” by Paul Park, “We Were Out of Our Minds With Joy” and “The Wedding Album” by David Marusek, everything in Ted Chiang’s The Story of Your Life and Others, “Lambing Season” by Molly Gloss, “Singing my Sister Down” by Margo Lanagan, all of North American Lake Monsters, Terry Dowling’s Wormwood and Charles Stross’s Accelerando, “A Dry Quiet War” by Tony Daniel, “Cassandra” and “The Last Tower” by CJ Cherryh, everything in Changing Planes by Ursula Le Guin, “The Lincoln Train” by Maureen McHugh, “Matilda Told Such Dreadful Lies” by Lucy Sussex, “each thing I show you is a piece of my death” by Gemma Files and Stephen Barringer, “Embracing the New” by Ben Rosenbaum. There’s more (oh, so many more) but that’s probably well and truly enough for people to be going in with. Every one of them taught me something, even if it was simply “wow”.

5. How did the whole Writers of the Future thing come about for you?

My winning story, “Bitter Dreams”, was the first one I wrote at Clarion West. Maureen McHugh (no relation, but she’s awesome) told me to send it, once I’d edited it, to F&SF with her personal recommendation, which I duly did and GVG duly replied with one of his standard “myeh, didn’t grab me” rejections. The final version of the story was over 12,000 words and WotF was about the only other professional market taking fantasy stories that long at the time, so I entered it there. I think the story really is too graphic and horrific for what they tend to prefer. I was just lucky that Tim Powers happened to be the judge who read it and, as a historical fantasy-horror, it floated his boat, whereas it might not have appealed to a lot of the other judges.

6. When did you first decide you wanted to be a writer?

I pretty much avoided it my whole life until the year I turned thirty. The risk of putting my work out there for people to see was just too terrifying. At the end of 2003, my then-wife introduced me to Matthew Farrer just before we moved to Fremantle. I can’t remember exactly what Matthew said, but he pointed me towards the KSP Writers Centre in Greenmount (across Perth from Freo) and got me onto short stories as a way out of my endless fantasy world-building procrastination.

7. What’s your favourite short story ever and why?

Either “The Wonderful Ice-Cream Suit” or “A Dry, Quiet War”, for opposite reasons.

At a prose level, virtually everything Ray Bradbury wrote is beautiful. He had a knack for delivering these soaring, elaborate word-paintings that nailed a given scene or moment, but he could do so without disrupting the, often, much more functional flow of his stories. “The Wonderful Ice-Cream Suit” is all that plus Bradbury at his most uplifting. It’s the sweetest, loveliest story I think I’ve ever read and the sort of the story that I’ll strive to emulate without ever believing that I’ll get there.

“A Dry, Quiet War” by Tony Daniel is a wrecking ball. It’s a Western where the combatants are post-human super soldiers from the war at the end of time. At the end of the story (spoiler alert) the hero is so pissed that he decides he’s going to kill the villain so hard he will never have existed. Apparently this involves the unravelling of intestines. And Daniel makes it work. Paul Park read it to us in our first week at Clarion West. I’d been planning to write a schlocky zombie-western for my first story in week two (you don’t write when Paul takes week one, you listen). Then Paul read “A Dry, Quiet War” and set the bar waaaaay higher than I’d been prepared for and I thought if I was going to write a Western I’d have to take it a lot more seriously. The result my productive panicking was “Bitter Dreams”, my WotF winner.

8. Do you envisage a time when you might give up short fiction and dedicate yourself to long form?

Not give up, no. I enjoy writing short stories too much. Long form is something I’ve been wrestling with for some time now. The past few years I’ve been battling to turn a 220,000 first draft of a novel, set in my “Bitter Dreams” world, into something more sensible. I think I know (now) what I need to do with it, but for the moment I’ve filed it under Cry For Help and moved on to saner pursuits.

9. A message to your younger, more angsty self?

Her name is Angie. Be patient, you’ll find her.

10. What is next for Ian McHugh?

After filing the Cry For Help, I wrote a few new short stories. One of them is sold and published already. It’s called “Uncle Bob’s Crocodile”, which you can find at Urban Fantasy magazine. Another will be out soon at Beneath Ceaseless Skies, called “Demons Enough”. Hopefully the rest will find homes over the next little while. I’m currently writing another, more straightforward novel that starts from two of the stories in Angel Dust – “The Canal Barge Magician’s Number Nine Daughter”, which first appeared in the Clockwork Phoenix 4 anthology, and “The Tax Collector of Rhuin”, which is one of the new stories in the collection. Fingers crossed this novel falls out better than the last one.

April 13, 2015

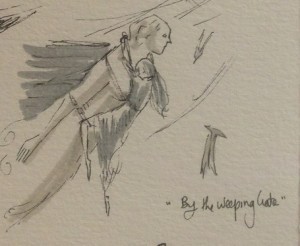

The Bitterwood Posts: By the Weeping Gate

This story first appeared in Stephen Jones’ Fearie Tales: Stories of the Grimm and Gruesome (Jo Fletcher Books). The title came from nowhere; I was thinking about pirates and ports, bordellos and brides – as you do – and the name came to me, a place where you pass from land to sea and those who watch you go or wait for you to come back, weep.

This story first appeared in Stephen Jones’ Fearie Tales: Stories of the Grimm and Gruesome (Jo Fletcher Books). The title came from nowhere; I was thinking about pirates and ports, bordellos and brides – as you do – and the name came to me, a place where you pass from land to sea and those who watch you go or wait for you to come back, weep.

I liked the idea of a girl who is terribly plain amongst all her beautiful sisters, but the sisters aren’t cruel to Nel. Her mother is, though: Dalita is a terrible woman, the epitome of a mother trying to relive her life through her favourite daughter. I have a whole history in my head for her, how she fled her own family and marriage, and made her own way in the world, how it turned her tenacious nature harsh and hard, and how – even though she’s got a strong idea of family – she sees even her own children as a means to an end.

Although her plainness is a source of some distress Nel finds a way to use it to her  advantage – she’s able to pass unseen when others would attract attention and so she can collect secrets as well. I love Nel, I love how she learns and changes and becomes something else in this story, how she takes her courage in her hands and goes out into the world to make things right, even though she is, at the end, someone who can no longer hide.

advantage – she’s able to pass unseen when others would attract attention and so she can collect secrets as well. I love Nel, I love how she learns and changes and becomes something else in this story, how she takes her courage in her hands and goes out into the world to make things right, even though she is, at the end, someone who can no longer hide.

By the Weeping Gate

See here?

This house here in Breakwater, this one, by the Weeping Gate where men and women come to wait and weep for those lost to the sea. This house is very fine, given the notoriety of the canton in which it resides; indeed, given the notoriety of its inhabitants.

This house here in Breakwater, this one, by the Weeping Gate where men and women come to wait and weep for those lost to the sea. This house is very fine, given the notoriety of the canton in which it resides; indeed, given the notoriety of its inhabitants.

The front stairs are swept daily by the girl who tends to such things (more of Nel later); the façade is cleverly created, a parquetry of stones coloured from cream through to ochre, some look as red as rubies, all creating a mosaic of florals and vines (the latter use malachite tiles). There is nothing like it anywhere else in the port city and there are uncharitable souls who whisper its existence is owed solely to the artisans’ truck with magic. The windows are always clean and shine like crystals, but none may see inside due to the heavy brocade drapes hung within.

Come to the door, look at its intricacies, all carved from ebony, bas-relief mermaids and sirens, perched upon jagged rocks with the sea throwing itself against those ragged angles. The knocker is surprisingly plain, as if some tiny attempt at good taste was made; it’s merely brass (highly polished, of course), with a slight ripple pattern so it looks something like a piece of rope. The house was not built by its current occupants – they have shifted into it, grown like a kind of hermit crab into a new shell – but by a sea captain who quickly made then lost his fortune to the ocean and its serpents and pirates, its storms and violent eddies, its whirlpools and deceptive coasts with rocks sewn just beneath the surface. After that, another man purchased it, an ill-famed prelate with no flock, who spent his days delving into dark mysteries, talking to spirits and trying to create soul clocks so that, if he might not live forever, he could at least access another lifetime. His departure from the city was encouraged by a nervous populace. The abode lay dormant and lonely for several years until this woman came along.

Dalita.

Tall and striking with jet-black hair, skin the colour of wheat, and eyes like brown stones. She dragged behind her three small daughters, their features enough like hers and distinct enough from each others’ to say they had different fathers. No one knew whether she bought the property or simply set up shop there – a lawyer did descend a few weeks after her presence was noticed, but by then her business was well-established (it took only a week).

The solicitor rapped the knocker, peremptorily, a look of displeasure on his face and entered when the door was whisked open. He came out some time later, features quite changed and set in what seemed an unfamiliar arrangement of happiness. He walked somewhat stiffly, now, but this did not seem to bother him at all. He became a regular visitor and was content to leave Dalita to her affairs (and her offspring, who continued to increase in number), and if his wallet was a little heavier and his balls a little lighter each time he left, then so much the better.

For all its decorative glory, the house does not have a delightful marine aspect. Perhaps that is unfair. By peeking out one window, inching one’s body sharply to the left and pressing one’s face hard against the glass, one might see, through the tight arch of the Weeping Gate, a sliver of water. It is, it must be said, a strip of the peculiarly unclean, slightly greasy liquid that lines the port, infected by humanity and its waste. But then, no one who ventures this far comes for the sea view.

For all its decorative glory, the house does not have a delightful marine aspect. Perhaps that is unfair. By peeking out one window, inching one’s body sharply to the left and pressing one’s face hard against the glass, one might see, through the tight arch of the Weeping Gate, a sliver of water. It is, it must be said, a strip of the peculiarly unclean, slightly greasy liquid that lines the port, infected by humanity and its waste. But then, no one who ventures this far comes for the sea view.

The house has no wrought iron fence, nor tiny enclosed garden; it simply sits cheek by jowl with its street, which is muddy in times of rain, dusty in times without. The cries of the gulls are not faint here, nor is the smell of fresh, drying or dying fish.

Once inside, however, incense and perfume, a heady opiate mix, negates any piscine odours (and others more personal, leisure-related), and anyone setting foot in the spectacular red entrance hall will immediately lose hold of their fears or concerns. The richness of the decor and the beauty of the girls, their charm, their smiles, their voices (coached to pitch low and light), combine to wash away all imperatives but one. After a single visit, even the most nervous of trader, wheelwright, tailor, sailor, princeling or clergyman – in short, anyone who can scrape up Dalita’s hefty fee – will be content to wander the requisite dark alleyways to the house by the Weeping Gate.

And in truth, with time the locale became strangely safer – mariners keen to earn extra coin were easily recruited to run interference in the streets. Thieves and ruffians learned quickly not to trouble those walking in a certain direction with a particular gait, lest they find themselves faced with consequences they did not wish to bear. The longshoremen were known on occasion to shift some of the more inconvenient street-side debris further away from the house. No need to scare the punters.

Gradually, Dalita’s clientele increased, and soon enough she took fewer habitués herself, becoming fussier, more miserly, with her favours. But as each daughter came of reasonable age, so too did the number of employees of the house; firstly Silva, then the twins Yara and Nane, then Carin, next Iskha, then Tallinn, and finally Kizzy.

Asha was kept aside, held back for finer things.

Asha was kept aside, held back for finer things.

And Nel, too, was kept aside, banished to the kitchens.

Iskha, taking her fate in her own hands, ran away and should not have been seen again.

***

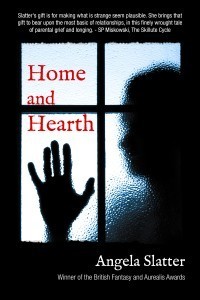

Home and Hearth

Just in case anyone’s interested … the Aurealis Award winning Home and Hearth is available on Amazon as a ebook … here.

Just in case anyone’s interested … the Aurealis Award winning Home and Hearth is available on Amazon as a ebook … here.

Just saying.