Angela Slatter's Blog, page 87

March 22, 2015

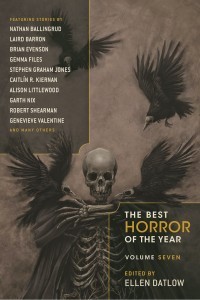

Year’s Best Horror Volume 7

Full ToC reveal and final cover! Squeeeee!

Full ToC reveal and final cover! Squeeeee!

“The Atlas of Hell” by Nathan Ballingrud (Fearful Symmetries, edited by Ellen Datlow, ChiZine Publications)

“Winter Children” by Angela Slatter (Postscripts #32/33 Far Voyager, edited by Nick Gevers, PS Publishing)

“A Dweller in Amenty” by Genevieve Valentine (Nightmare Magazine, March 2014)

“Outside Heavenly” by Rio Youers (The Spectral Book of Horror Stories, edited by Mark Morris, Spectral Press)

“Shay Corsham Worsted” by Garth Nix (Fearful Symmetries, edited by Ellen Datlow, ChiZine Publications)

“Allocthon” by Livia Llewellyn (Letters to Lovecraft, edited by Jesse Bullington, Stone Skin Press)

“Chapter Six” by Stephen Graham Jones (Tor.com, June 2014)

“This is Not for You” by Gemma Files (Nightmare Magazine, September 2014)

“Interstate Love Song (Murder Ballad No. 8)” by Caitlín R. Kiernan (Sirenia Digest #100, May 2014)

“The Culvert” by Dale Bailey (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, September/October 2014)

“Past Reno” by Brian Evenson (Letters to Lovecraft, edited by Jesse Bullington, Stone Skin Press)

“The Coat Off His Back” by Keris McDonald (Terror Tales of Yorkshire, edited by Paul Finch, Gray Friar Press)

“the worms crawl in” by Laird Barron (Fearful Symmetries, edited by Ellen Datlow, ChiZine Publications)

“The Dog’s Home” by Alison Littlewood (The Spectral Book of Horror Stories, edited by Mark Morris, Spectral Press)

“Tread Upon the Brittle Shell” by Rhoads Brazos (SQ Magazine, Edition 14, May 2014)

“Persistence of Vision” by Orrin Grey (Fractured: Tales of the Canadian Post-Apocalypse, edited by Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Exile Editions)

“It Flows From the Mouth” by Robert Shearman (Shadows & Tall Trees, Volume 6)

“Wingless Beasts” by Lucy Taylor (Fatal Journeys, Overlook Connection Press)

“Departures” by Carole Johnstone (The Bright Day is Done, Gray Friar Press)

“Ymir” by John Langan (The Children of the Old Leech, edited by Ross E. Lockhart & Justin Steele, Word Horde)

“Plink” by Kurt Dinan (Postscripts #32/33 Far Voyager, edited by Nick Gevers, PS Publishing)

“Nigredo” by Cody Goodfellow (In the Court of the Yellow King, edited by Glynn Owen Barras, Celaeno Press)

March 19, 2015

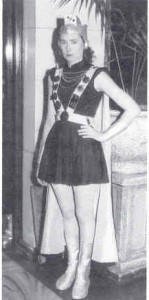

The Norma!!

Norma K. Hemming in costume in 1956 – http://www.asff.org.au/hemming.htm

Gods, but I love that Australia has an award called the Norma!

That’s the Norma K. Hemming to you.

The exciting news is that The Female Factory has been shortlisted! Look at our teeny-tiny collection with all those awesome novels! *much Snoopy dancing*

“The following works have been shortlisted by the judges for the 2015 Norma K Hemming Award for race, gender, sexuality, class and disability in speculative fiction sponsored by the Australian Science Fiction Foundation:

Collection: The Female Factory’by Lisa L Hannett and Angela Slatter published by Twelfth Planet Press in November 2014

Novel: Nil By Mouth by LynC published by Satalyte Publishing in June 2014

Novel: North Star Guide Me Home by Jo Spurrier published by HarperVoyager in May 2014

Novel: Razorhurst by Justine Larbalestier published by Allen and Unwin in July 2014

Novel: The Wonders by Paddy O’Reilly published by Affirm Press in July 2014

The award will be presented to the winner at Swancon 40, the 54th Australian Science Fiction Convention in Perth, on Sunday evening 5th April 2015.”

March 18, 2015

The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy and Horror: 2015 Edition

Utterly delighted to have my fourth outing in Paula Guran’s The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, this time in the 2015 Edition (Prime Books) – and to share it with Lisa Hannett in her first appearance there makes it even more special!

Utterly delighted to have my fourth outing in Paula Guran’s The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, this time in the 2015 Edition (Prime Books) – and to share it with Lisa Hannett in her first appearance there makes it even more special!

Our title story from The Female Factory collection (Twelfth Planet Press – Twelve Planets Series #11) is making a cameo alongside the likes of Helen Marshall, Laird Barron, Caitlin R Kiernan, Brandon Sanderson, Jeff VanderMeer, Lavie Tidhar, and the excellent Kaaron Warren.

For the full ToC and pre-order details, go here!

And, should you wish to buy the original Female Factory collection (and let’s face it, you know you want to), go here!

March 16, 2015

QWC Short Story Clinic

In just over three weeks I’ll be teaching the Short Story Clinic at Queensland Writers Centre. What I aim for is for students to come out of the course with at least one short story that’s fit to begin the process of submitting to magazines, journals and anthologies.

In just over three weeks I’ll be teaching the Short Story Clinic at Queensland Writers Centre. What I aim for is for students to come out of the course with at least one short story that’s fit to begin the process of submitting to magazines, journals and anthologies.

What can you expect during the course? Firstly, critique on what does and doesn’t work in your tale from myself and your fellow student-scribes. Secondly, story development suggestions and solutions, as well as some structural and line editing. Thirdly, market and submissions advice whenever appropriate.

Testimonials required? Have a look here.

Contact QWC to book in.

Dates:

Tuesday April 7

Tuesday May 5

Tuesday July 7

Tuesday August 4

Tuesday September 8

Tuesday October 6

Time:

6:00pm – 8:00pm

Venue:

The Learning Centre, QWC, Level 2, State Library of Queensland, Cultural Centre, Stanley Place, South Brisbane.

March 15, 2015

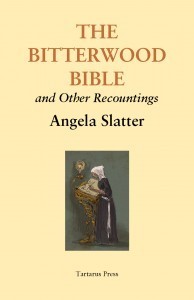

The Bitterwood Posts: The Night Stair

Art by Kathleen Jennings

In 2012, my Significant Other and I were travelling around the UK and we visited Battle Abbey where the Battle of Hastings had taken place. We wandered through the ruins and one of the signs pointed out the night stair that the monks had taken when going to early services. I just loved that name and thought it sounded positively sinister. Where might it really lead?

I carried that around in my head as a title for the better part of a year until I started thinking about a vampire tale for Bitterwood. I could see Adlisa standing in the selection line, waiting, hoping to be chosen, not for a perceived better life, but so she could act, find the truth, and, with any luck at all, get revenge. But, as always, there’s a sting in the tale. She’s another character I want to revisit later, as Adlisa the Bloodless – she’s already got a mention in the new collection, The Tallow-Wife and Other Tales, and I hope to expand on that some time in the future.

The Night Stair

Art by Kathleen Jennings

The Steward is a tall man, entirely bald, gaunt in the face, yet rotund in the belly. His legs in their loose fawn linen trews, look like a scarecrow’s, sticking out under the awning of his gut – perpetually in shade perhaps they don’t get enough light to grow. His tunic of padded green silk, his sable wool coat with its thick fur collar, are too warm even for the end of summer, but as marks of his office, must be seen, just like the yellow crystal hanging about his neck. Called the “Steward’s Gaze”, it’s the size of the top joint of a man’s thumb, and has passed from incumbent to incumbent for as long as anyone has the will to recall. He puts it in his mouth and sucks hard when he thinks no one is watching. It’s worth a king’s ransom, and I’ll warrant the gold chatelaine belt around his waist could buy the city’s food for half a year.

His finery makes me aware of the state of my black dress – not that it’s poor or made shiny by age, but it belonged to others before me. Both my sisters – my only full-blood siblings – wore it to their own choosing. I am certain I can smell them, their scents imprinted into the warp and weft of the fabric despite washing. The colour makes my skin paler, my eyes bluer, provides the perfect background for the tresses, which pour down my back like gold fresh from the smelter. I was careful, so careful with my toilette: brushing my hair, one hundred strokes; rubbing the cream that was my mother’s (comfrey and rose to soften and plump, a little lemon balm for lightening) into my skin; drops of eyebright to ensure my gaze is clear. I refrained from pinching my cheeks – pale is best – but I did nip gently at my lips, to carmine them a little, so it seems as if all life is concentrated there. I will not be found wanting.

I stand in line with seven other girls who have been presented this day. We are of an age, none more than sixteen springs, and there is only one of them, perhaps two, who might outdo me. To my right is Essa, with her milky skin and eyes like the sky reflected in ice, hair bright platinum; even her nails seem to have a silvery sheen. She watches me from the corner of her eye, just as I watch her.

To my left is Dimity, whose eyes are bright green, her cheeks with the tiniest hint of pink. She keeps her regard firmly fixed upon her own feet. Our Lady best likes girls who resemble herself; that is not Dimity for all her snow-washed whiteness – the eyes are all wrong and the eyes count.

So, Essa. Essa is the one to beat – the Steward will surely select between the two of us.

Filling this large room in the city hall are parents, including my father, who’s left the running of the mine’s smelter to his deputies so he can see what deals might be struck. Behind him are three of my younger half-siblings, those not yet old enough to be exhibited, but deemed mature enough to watch proceedings in order to learn how to behave when – if – their time comes. Another ten still wait at home; not all will be offered, only those whose appearance is right, those whose behaviour does not mark them out as more trouble than they’re worth. My father has twice made a small fortune from this process and I imagine he hopes to again – his tendency for taking new wives, sometimes before the old one is done, and his proclivity for procreation, his personal fecundity, constantly require more funds than his well-paid position provides.

Filling this large room in the city hall are parents, including my father, who’s left the running of the mine’s smelter to his deputies so he can see what deals might be struck. Behind him are three of my younger half-siblings, those not yet old enough to be exhibited, but deemed mature enough to watch proceedings in order to learn how to behave when – if – their time comes. Another ten still wait at home; not all will be offered, only those whose appearance is right, those whose behaviour does not mark them out as more trouble than they’re worth. My father has twice made a small fortune from this process and I imagine he hopes to again – his tendency for taking new wives, sometimes before the old one is done, and his proclivity for procreation, his personal fecundity, constantly require more funds than his well-paid position provides.

Steward Oswain walks slowly up and down our line, as if inspecting troops. His brown eyes are considering, patient, although a little uncertain, as if offered several courses at a banquet and told he might only have one. He stops in front of the Toop girl and shakes his head (anyone can see she’s too fat), then the Ansible twins (hair too dark), and then Mistress Garran’s girl (whose neck is smudged by a red birthmark); a dismissal for each. At the back of the crowd I hear a woman crying; she is shushed and hustled out – I cannot tell if her weeping was of relief or despair. The desperate whirring of my own thoughts is far too loud.

I straighten my shoulders, lift my head a little higher, blink quickly so that tears of fear do not start and cause the coal-mascara on my lashes to run. The Steward takes one more pass; another. He stops in front of Dimity – Dimity! – puts a finger under her chin and makes her look at him. Her lips tremble; he smiles kindly and nods. Essa makes a noise, and this one I know for relief. The Steward steps back, turns away. All scrutiny has left us. Parents mill around the tall stork of a man to strike bargains; Dimity’s mother to get the highest price, the others to find out when there might be another choosing – as if the Steward can predict Our Lady’s moods to a day and date! Only my siblings still watch, their eyes fastened onto me as if by hooks.

Dimity takes her first step forward as a chosen girl and I trip her. Essa’s intake of breath is sharp. The green-eyed maiden falls so fast, is so surprised, that she does not put her hands out to save herself. Her face meets the floor with a satisfying crunch of bone and cartilage. There is that tiny broken moment when nothing happens, no one moves, when time is divided into before and after, then, as if a clock’s hands click over, everything starts again, and the girl on the floor wails. I do not move.

Dimity sits up, blood pouring from her ruined nose. She stares at me all uncomprehending, hands twitching as if to point me out, but she catches my glance and I can see her crumple inside. She sobs a little more quietly and when an adult asks what happened, she answers with ‘I fell’.

She will thank me; or rather, she would if she thought about it.

***

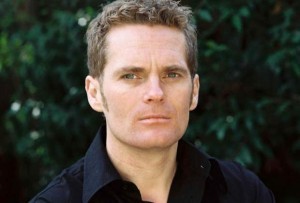

James Bradley’s Clade

Sydney author James Bradley’s new novel Clade has recently been released into the wild. His three previous novels, Wrack, The Deep Field and the international bestseller The Resurrectionist, have all been widely translated, and won or been shortlisted for major literary awards. He’s also written a book of poetry, Paper Nautilus, and edited the anthologies, Blur and The Penguin Book of the Ocean. Not only that, he’s been shortlisted for the Aurealis Awards in the Best Horror Short Story category for his tale “Skinsuit” (which originally appeared in Island Magazine #137).

Sydney author James Bradley’s new novel Clade has recently been released into the wild. His three previous novels, Wrack, The Deep Field and the international bestseller The Resurrectionist, have all been widely translated, and won or been shortlisted for major literary awards. He’s also written a book of poetry, Paper Nautilus, and edited the anthologies, Blur and The Penguin Book of the Ocean. Not only that, he’s been shortlisted for the Aurealis Awards in the Best Horror Short Story category for his tale “Skinsuit” (which originally appeared in Island Magazine #137).

Clade is a multi-generational saga about family, love and loss in a world  irrevocably warped by environmental change. Gary K. Wolfe of Locus online has said: “[Clade] is among the most literate and humane contributions to that slowly emerging tradition of what is sometimes called ”slow apocalypse” fiction . . . It’s his astute management of chronology, as each section leaps years ahead of the preceding one, that generates the novel’s haunting and elegiac feeling, making it a near-epic of loss, remembrance, and steadily diminishing hope.”

irrevocably warped by environmental change. Gary K. Wolfe of Locus online has said: “[Clade] is among the most literate and humane contributions to that slowly emerging tradition of what is sometimes called ”slow apocalypse” fiction . . . It’s his astute management of chronology, as each section leaps years ahead of the preceding one, that generates the novel’s haunting and elegiac feeling, making it a near-epic of loss, remembrance, and steadily diminishing hope.”

So, what do readers need to know about James Bradley?

I’m never quite sure what to say when people ask me that! I guess the answer is that I’m a writer who’s published four novels (Wrack, The Deep Field, The Resurrectionist and, most recently, Clade), a book of poetry, Paper Nautilus, and a fair number of shorter things. I’ve also edited a couple of anthologies, the most recent of which was The Penguin Book of the Ocean, and I write and review for newspapers and magazines, as well as running a blog, and in 2012 I won the Pascall Prize for Australia’s Critic of the Year. I live in Sydney with my partner, the writer Mardi McConnochie and our two daughters.

Where did the inspiration for Clade spring from?

I’d been trying to find a way of writing about climate change for a long time, but although I’d managed to get at it tangentially in a few short stories (in particular ‘Visitors’, which was published by Review of Australian Fiction) and non-fiction I’d always found the subject too complex and unwieldy to really get a grip on. But after we had kids I found the whole subject started to take on a different edge, as it began to become clear to me just what a disaster we’re leaving them.

Who were/are your literary heroes/influences?

Who were/are your literary heroes/influences?

So many. Le Guin, Ondaatje, Gibson, Dickens, George Eliot, Margaret Atwood, Tolstoy, Lorrie Moore. Just lately I’ve been blown away by Helen MacDonald’s astonishing H is for Hawk, and I’ve been rereading Auden and Heaney, who remain as astonishing for ever. And Clade takes some inspiration from Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars books, as well as a lot of recent nature writing.

You wrote a novelette Beauty’s Sister for Penguin a couple of years ago – how did that come about?

I wrote ‘Beauty’s Sister’ as a sort of experiment – I’d just abandoned a novel quite a long way through the editing process, so I wanted to try something completely different. And one day I woke up with the narrator, Juniper, in my mind, and a series of questions about what it must have been like to be Rapunzel’s parents. After I wrote it I really had no idea what to do with it, mostly because it was so long, and then, out of the blue, Penguin approached me to say they were setting up a digital publishing initiative called Penguin Specials, so I sent it to them and they liked it. Interestingly they later republished it as a physical book, which was great, because it meant it found a whole new audience. Since then I’ve written several more fairy-tale themed stories, partly because I’m so fascinated by the weirdness of fairy tales, their psychological elisions and strangeness, partly because I feel like there’s something in them I haven’t quite got at yet.

How does Clade differ to your previous novels?

Because my books bounce around so much in time people tend to think they’re very different to each other, but I’ve always thought they share quite closely allied interests, and that there are some strong commonalities binding them together: if nothing else they’re all interested in time, and mortality, and continuance (they also all tend to explore questions about unsettled identity).

Yet at the same time each one is written as a reaction to the last, which means they tend to diverge quite violently stylistically and in terms of subject matter. With Clade I was reacting to The Resurrectionist, which was both a very difficult book to write and ended up being a deliberately disordered and stylistically dense novel in which the voice does a lot of the work, and at least partly as a result of that Clade is a much sparer and cleaner novel. That contrast is on purpose, partly because I couldn’t face the thought of writing a book as unsettled (or unsettling) as The Resurrectionist again, partly because when I began Clade I’d developed an almost visceral distaste for writerly writing. But I also wanted it to be a more hopeful book, because at the end of the day I feel like we need to find ways of thinking about the future which allow us the possibility of changing it.

When did you first decide you wanted to be a writer?

I started writing in my early 20s, when I began publishing poems. Before that I’d always felt like I saw the world slightly differently from the people around me, but I’d never really known how to express that. After a year or two I decided I wanted to try and write a novel that did the things with language and form I was trying to make poetry do, but on a much larger scale. I suspect in some ways I’m still trying to do that.

Which book would you say taught you the most about writing?

Which book would you say taught you the most about writing?

I suspect the book of mine that taught me the most about writing was The Resurrectionist, although sadly a lot of it was about what not to do, or not to do again. But I think all of them have taught me things, and each new one is about trying to do various things better than I did the last time. In terms of books by other people I’m not really sure – in recent years I’ve been fascinated by the way Alice Munro’s stories manage to do cover such big spans of time without ever seeming truncated, so a story feels as full as a novel, and I love the incredible acuity of Hilary Mantel’s representation of psychology. There are also writers like Ondaatje who have taught me a lot about structure, and writers like Rachel Kushner and Don Delillo and others who have taught me about language.

Do you find it difficult, shifting gears between short and long fiction?

I love the scale of novels, their thickness and variousness, but I also love the narrative concision of short stories, the way they can turn you 180 degrees in just a few pages, so the pleasures of writing each are slightly different. But having said that I don’t usually find shifting between thema challenge, although if I’m working on a novel I find it almost impossible to do anything else, so convincing myself to stop for a week or two to write a short story can be difficult.

What’s next for James Bradley?

The $64,000 question. I’ve been writing a trilogy of YA SF novels which I’m halfway through, although I still don’t know what I’ll do with them. I’m working on a couple of novels as well: one with graphic elements, and another which is historical, and I’m slowly mapping out a couple of collections of shorter fiction. But I’ve also got a new adult novel slowly coalescing and feels increasingly interesting. Which of them gets finished first is a bit of an open question at the moment, all I know is I want whatever comes next to be new somehow, denser, more alive, and for it to feel urgent to me.

March 13, 2015

New novella: Fitcher’s Bird

Art by Arthur Rackham

I’ve started a new novella today, Fitcher’s Bird, a modernisation of the old fairy tale mingled with a serial killer story. Because I’m cheerful like that, me.

Once upon a time there was a girl who lost her sisters, but she found their bones long after the flesh had fallen away.

She took those bones, they were hers, after all, who else had such a right to them? She planted these weird seedlings in the eventide, down at the bottom of her garden. She fed them with water and blood and dead things that no longer minded the uses to which they were put. She watched and tended the strange beds she’d sewn.

She waited. She was patient as good sisters are. And then one night when the moon grew full and fat in the sky, she saw the soil begin to tremble, small avalanches of dirt trickling from the raised plots until, at last, pale thin fingers broke the earth and glowed beneath the midnight light.

***

March 12, 2015

QWC Blog Post – Starting your story: if the door won’t open use a window

In the lead-up to my short story clinic at QWC, I’ve written an article for the Queensland Writers Centre blog about how to start your short stories.

In the lead-up to my short story clinic at QWC, I’ve written an article for the Queensland Writers Centre blog about how to start your short stories.

The thing to remember is that the short story starts in medias res – in the middle of things. You don’t have the luxury of telling your reader the history of everything and everyone who appears in your tale. You need to go in at the point of conflict, or very close to it … either before or after. For me a short story is about crisis, choice, and/or consequence. The closer you start to these events, the tighter the tale will be.

So: doors and windows. Sometimes your story just isn’t working. It’s too slow, your character isn’t right, you can’t get the narrative drive into gear – you’re boring yourself and if you, the writer, are bored, then your readers are most assuredly going to be bored.

So, what’s the remedy?

The rest is here.

March 9, 2015

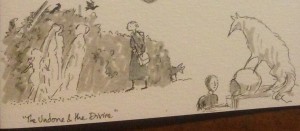

The Bitterwood Posts: The Undone and the Divine

Kathleen’s sketches

This story has quite a few inspirations feeding into it. I wanted it to show carry on action from the earlier tales “The Burnt Moon” and “The Badger Bride”, and show a little more of Adelbert’s life and to introduce the character of Delling, one of the daughters of Wulfwyn from “The Burnt Moon”. The title comes from a Florence + the Machine song, “Bedroom Hymns”, the name Delling (Dellingr) is that of a male god from the Norse Sagas, and the naglfar is a boat made from the finger and toe nail clippings of the dead, which will take part in Ragnarok. I don’t know why I picked out these very Norse elements, but I just liked the sound of Delling as a girl’s name, and the idea of the nail-boat was very rich and resonant for me when I read about it.

More of Kathleen’s sketches

I also wanted to revisit Southarp and her people, some of whom were complicit in the burning of Hafwen and some of whom were collateral damage of Adelbert’s terrible revenge. I liked the idea that they were stuck on earth, and so simply carried on in death the way they had in life. I love the idea of Delling coming to do a great, selfless work and thus earn release for someone she loves as well as people she never knew – I think the title of the story plays to this: that the town of Southarp and its folk had been undone, and what Delling does is rather divine. I think she’s a wonderful character and hope to revisit her again someday.

The Undone and the Divine

The ghosts spend their days profitably, doing precisely what they did in life.

Trading, gossiping, building, baking, shoeing ephemeral horses with u-shaped things made of smoke and promises, sleeping when the sun sets and rising when it shows its face once more, fornicating as is only natural. Such coupling, however, is unsatisfying, for it produces nothing, neither pleasure nor offspring; ethereal fingers pass through gossamer flesh. Touches are felt no longer than the tiniest fragment of a second, with no lingering to allay the longing. At its heart, the village is broken and without purpose.

So when Delling, shaven-headed, in a faded blue travelling dress, crosses the burnt boundaries, steps over the earthy threshold still marked with deepest ash and visible under the grass and wild foliage after all the lonely years, the spectres go about their business, pretending that she is the insubstantial one. They ignore her when she says, quite loudly, ‘Southarp’ into the warm air. They ignore her although they yearn to know what she carries in the satchel hung at her hip and the sandalwood box slung across her back. They wonder why she looks familiar. They are even more curious to note that she does not run screaming when she sees them, for see them she does.

So when Delling, shaven-headed, in a faded blue travelling dress, crosses the burnt boundaries, steps over the earthy threshold still marked with deepest ash and visible under the grass and wild foliage after all the lonely years, the spectres go about their business, pretending that she is the insubstantial one. They ignore her when she says, quite loudly, ‘Southarp’ into the warm air. They ignore her although they yearn to know what she carries in the satchel hung at her hip and the sandalwood box slung across her back. They wonder why she looks familiar. They are even more curious to note that she does not run screaming when she sees them, for see them she does.

For a while, she stops and watches the phantoms as they do their dance of imagined life, taking in their faces and storing them in her memory. Then she moves along. Beneath the thick soles of her boots, Delling can feel things crunch and crumble; the last of the rats’ skeletons, friable, but defiant against the elements and time. She strides past the shell of the Burnt Moon Mill where the wheel still hangs, precarious on the last few struts and wall fragments. It no longer turns, although slapped and batted by the water, but does not yield; the liquid gives up, splits and flows around the fluid-eaten paddles that have been submerged for so long they are covered with a green algae that seems fluorescent. Delling eyes the mill and the skeleton of the cottage that once housed Cenred and Cern and Wulfwyn. She continues on by the hunched shape of the inn, all collapsed in on itself with vines climbing thickly over it, like some great beast gone to sleep for too long and trapped. Along the streets she goes, accompanied by the crunch-crunch-crunching of her shoes as they grind down the past.

So many left-overs, so many burnt-out wrecks, so much loss, but the silhouette of the old is still there, the figure of the village remains. Just like the moving shadows and shades that hustle and bustle in the last of the afternoon sun, the goodwives nodding to each other, the menfolk closing their stalls for the day, penning up ghostly animals, picking spectral vegetables from gardens long since grown over. As she passes she can see them all disappearing into their cremated homes; through non-existent walls she watches them prepare for the evening, cooking illusory meals that can be neither tasted nor truly eaten, setting children tasks that no one will care to check. Soon, they will be abed. Delling wonders if ghosts dream.

***

Simon Kurt Unsworth: The Devil’s Detective

UK writer Simon Kurt Unsworth has been writing some fairly stunning and disturbing short fiction for quite some time – if you’re a fan of his, then hold onto your hat because his first novel has just been released into the wild. The blurb for The Devil’s Detective reads thusly:

UK writer Simon Kurt Unsworth has been writing some fairly stunning and disturbing short fiction for quite some time – if you’re a fan of his, then hold onto your hat because his first novel has just been released into the wild. The blurb for The Devil’s Detective reads thusly:

Welcome to hell…

…. where skinless demons patrol the lakes and the waves of Limbo wash against the outer walls, while the souls of the Damned float on their surface, waiting to be collected.When an unidentified, brutalised body is discovered, the case is assigned to Thomas Fool, one of Hell’s detectives, known as ‘Information Men’. But how do you investigate a murder where death is commonplace and everyone is guilty of something?

So, what do readers need to know about Simon Kurt Unsworth, Writer?

That he’s tall, wears cowboy boots and writes directly into his iMac or MacBook with his iTunes library on permanent shuffle. I suppose it might be useful for people to know that I’ve had three collections of short stories published, Lost Places from Ash Tree Press, Quiet Houses from Dark Continents Publishing and Strange Gateways from PS Publishing, and that I’ve had lot of stories published, including being reprinted in six volumes of The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror. If people want to send me gifts, I’m partial to single malt whiskey, spiced rum, weird bolo ties and pizzas.

Where did the inspiration for The Devil’s Detective spring from?

The short answer is, I don’t quite know! I was in Leeds and I had a sudden image of a train rumbling down the street outside the bedsit I was in, the windows of it filled with screaming faces. At the same time, I had a clear idea about a policeman in Hell trying to solve a really, really gruesome set of murders, and the name Thomas Fool became associated with the policeman. Tom Fool was a real person, incidentally – he was the jester at Muncaster castle, and is alleged to have killed someone, and his ghost is now said to haunt the castle. I’d seen one of those ‘primetime dramatisations masquerading as a documentary’ things about him and it scared me silly for some reason, and the three things kind of came together in my head. It took twenty years from having those initial ideas to actually writing the damn thing, though, and most of the incidents in the plot were the result of simply sitting and working things out. I always had the ending in my head, it was just a case of getting everyone there. Incidentally, Tom Fool is where we get the word tomfoolery from…

Who were/are your literary heroes/influences?

Oh God, where to start! Well, clearly, Stephen King, especially the early stuff – ‘Salem’s Lot is my favourite novel bar none, and Night Shift was an early masterclass for me in the creation of brilliant short stories. I go through phases with King more recent work (I’m on a ‘liking his stuff again’ phase at the moment), but his old stuff is unassailable in my view. M. R. James wrote the best ghost stories I’ve ever read, and T.E.D. Klein’s stuff (especially the story ‘Children of the Kingdom’) gave me a voice to rip off when I was starting to try and write things. Japanese graphic novelist Junji Ito – and if you don’t think graphic novels are novels, if you think they’re in some way lesser artforms, go and read the three volume masterpiece that is Uzumaki and if you aren’t persuaded of the sheer power of the graphic novel after reading that, you’re lost to the darkness – is an artist who doesn’t produce enough stuff (that gets translated, at least), and he just awes me and keeps me hoping that one day I’ll write something as good as his work. For various reasons, the work of Kim Newman, Christopher Fowler and John Connolly have provided inspiration, and the films of John Carpenter are a constant source of joy and influence. Mostly, though, I try to think about what it might feel like to have my family and friends in dire situations, and write about how that might feel. Zombie apocalypses are all well and good and very exciting, but actually what’s more terrifying to me than the walking dead is my son or wife or stepchildren being threatened by the walking dead, and it’s that feeling I try and find in my writing.

What draws you to writing horror?

Because it’s what I like to read, and because it’s what I like to watch. It’s really that simple.

You are allowed to invite five people, dead or alive, to a dinner party – who are they and why?

This is an odd one, really, because I’ve kind of decided that I don’t want to meet my heroes in case I’m disappointed. I have a horrible suspicion that if I met Spike Milligan, for example, he and I would not get on at all (despite my belief that he’s one of the funniest men ever to have put pen to paper, and him being hugely important in what I find funny and how I see the world), and that might spoil my enjoyment of his work. That aside, I suppose the 5 people I’d want are:

My wife, Rosie. She’s my best friend, and I can’t imagine not having her with me for something like this.

Stephen King, just because that way I’d have met him (instead of just being in books with him!). He and I have similar political leanings, so I think we’d get on okay. Plus, he might let slip some ideas I could nick…

The writer Larry Connolly. He and I only see each other about once every 3 years so it’d be great to catch up with him.

Note: I’ve hit three and can’t think of any more unusual guests, because I’ve genuinely got the people in my life I want and there’s no one I’m desperate to meet – so my last two guests are my son Ben, because I don’t see him enough and he’s ace, and my best friend Steve because he always, always makes me laugh and feel better about myself.

What was the process like, selling the novel from go to whoa?

Long! I originally sent the first three chapters of the novel to my now-agent John Berlyne on the advice of my friend Steve Volk. John told me he didn’t read unfinished stuff, but then (thankfully!) read it anyway and decided he liked it. He gave me some specific advice and then told me to “fuck off and finish it and then come back to me” (his words, not mine). I did, and then we spent some time going back and forth tightening and changing things until we had something pretty good. John then did his funky agent thing, and nine months later we started to get interest…and then offers. The process of deciding which offer to take, while John worked his Machiavellian magic to made the various offers as good as possible, took a few weeks and then it took another few months of contract negotiation (thankfully all carried out by John and not me!) before we had something I could sign. I worked out it was almost exactly a year between formally agreeing to represent me and us selling The Devil’s Detective. I don’t know if that’s normal or not, but it was a strange period, characterized by long periods of frustrating nothingness and then periods of frenzied emails and phone calls and offers and counter-offers. I look back on that time with a kind of startled affection, because my life changed so completely over those twelve months that I almost don’t recognize the person I used to be compared to the person I am now.

When did you first decide you wanted to be a writer?

I’m like most writers, I think – I’ve never not wanted to be a writer. If you’re asking when I thought I could be writer, there are two points: at about 13, I wrote a story that basically ripped of Stephen King and my English teacher, who had previously not responded well to anything I’d done, gave it a high mark. It made me think I could write, and from that point it was what I wanted to do. Later, I took some creative writing courses and during one of these I wrote the story ‘The Baking of Cakes’, which is where I think I found my voice and confidence because of how people responded to it.

Who’s your favourite villain in fiction?

Who’s your favourite villain in fiction?

Three houses tie for this: the Overlook Hotel, Hell House and Hill House. I’m a total sucker for a good haunted house story, and those three are pinnacles for me because in each the house itself is a character, sinister and threatening and dangerous. They’re fucking terrifying!

What’s your favourite short story ever and why?

Oh, that’s tough, there are so many. Well, Clifford D. Simak, Hell House, Hill House, Shirley Jackson, Clive Barker,’s ‘Skirmish’ is near-perfect for me because it’s a self-contained tale but also acts as a gateways to a bigger world into which we can imagine ourselves. M.R. James’ ‘The Mezzotint’ is brilliantly, creepily nasty and is a big influence, King’s ‘Battleground’ is a masterpiece of dealing with an essentially silly central idea with absolute straightness and creating something brilliant as a result, and Barker’s ‘In the Hills, the Cities’ shocked me damn near catatonic when I first read it. I think, though, that it has to be the James’ tale that takes the crown – just. It is, to me, a perfectly crafted gruesome vignette, both frightening and upsetting and delivered with neither explanation nor apology.

What’s next for Mr Simon Kurt Unsworth?

The sequel to The Devil’s Detective, currently called The Devil’s Evidence, is taking up most of my writing time. Outside of that, I’m enjoying being a husband, dad and stepdad, so I’ll keep on it them as well.