Angela Slatter's Blog, page 86

April 12, 2015

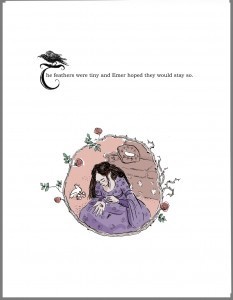

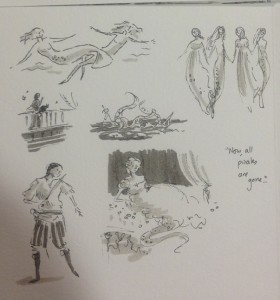

Flight – roughs

Off to meet Kathleen and Sue from Tiny Owl Workshop to chat about the layout for the picture book version of Flight. Very excited – even Kathleen’s ‘rough’ artwork is exquisite.

Off to meet Kathleen and Sue from Tiny Owl Workshop to chat about the layout for the picture book version of Flight. Very excited – even Kathleen’s ‘rough’ artwork is exquisite.

Still-life with Awards

All the awards together

So, I went off to Canberra for the Aurealis Awards (their twentieth anniversary) and, no matter what else happened, it was always going to be about catching up with folks, especially my Brain, Lisa L. Hannett, talking lots, ordering room service, talking more, napping, ordering room service again, talking more, then getting all dressed up for a night out with our tribe.

We headed off to University House, where all (except those who had Supanova, wedding, and other commitments) had gathered, to be emceed and regaled by Queen Margo Lanagan, and wowed by some excellent 1995 costumes. Among others, we heard from the lovely Garth Nix and the even lovelier Kate Forsyth, with some great readings by Margo of the 1995 award winners.

To my delighted embarrassment – or embarrassed delight – I came away with three awards, one of them with Lisa for our Twelfth Planet collection The Female Factory, as well as the Best Fantasy Short Story for “St Dymphna’s School for Poison Girls”, and Best Horror Short Story for “Home and Hearth”. So it was lucky I’d taken the time to write all six acceptance speeches despite my grumbling about not needing them.

The Female Factory Award went home with Lisa – I’ll get mine when we organise for a second one.

A few bottle of celebratory Tattinger later (thanks Kate Forsyth and Liz Grzyb), it was time to retire before we turned into pumpkins – a very real possibility. Sunday was spent wandering over to the National Gallery, then lunching with the lovely Tehani Wessely and her terrific offspring, before heading back to the airport.

A few bottle of celebratory Tattinger later (thanks Kate Forsyth and Liz Grzyb), it was time to retire before we turned into pumpkins – a very real possibility. Sunday was spent wandering over to the National Gallery, then lunching with the lovely Tehani Wessely and her terrific offspring, before heading back to the airport.

A whirlwind trip, but well worth it for the company! But coming home is always nice, too, returning to the Significant Other and putting the awards on the shelf with the other ones.

Thanks to Nicole Murphy and Tehani and all the other judges and organisers and volunteers who worked so hard to make the night excellent!

For all of the results, go here – and read the shortlistees as well as the winners for all the works are so amazing it’s a privilege to be numbered amongst them.

All photos are Lisa’s, except the last.

April 8, 2015

The Norma – An Honourable Mention

The Female Factory got an honourable mention for the Norma K. Hemming Award on the weekend (the actual award being taken out by Paddy O’Reilly’s very excellent novel The Wonders)! From the Judges’ Report:

The Female Factory got an honourable mention for the Norma K. Hemming Award on the weekend (the actual award being taken out by Paddy O’Reilly’s very excellent novel The Wonders)! From the Judges’ Report:

For the 2015 competition, the Judges also saw fit to award an Honourable Mention to the runner up, a collection of stories by Lisa L Hannett and Angela Slatter titled The Female Factory, published by Twelfth Planet Press in November 2014.

The Judges, writer and editor, Russell Blackford; editor, Sarah Endacott; writer, editor and publisher, Rob Gerrand; and writer, Tess Williams, commenting on the runner up, said:

“Lisa Hannett and Angela Slatter’s The Female Factory explores the different stages of human female life: from conception, to childhood, to old age. Reproduction is a fraught thing, with burgeoning wombs and bargaining for ‘surrendered’ babies. Motherhood is just as tortured, and the stories canvass desire, antipathy and resentment. With rich prose and tantalising scenes, the collection is a clever meeting of genres.”

April 7, 2015

The Bitterwood Posts: Terrible As An Army with Banners

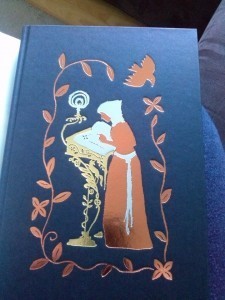

Kathleen’s final cover art

This is the story that always make me cry, so I can never read it out anywhere or I’ll end up as a snotty, blubbering mess. It’s a mix of letters and diary entries; it starts with one sister writing to another, and I channelled my relationship with my own sister when I wrote this. We are very different, but very close … but very different. We frequently look at each other with that dreadful astonishment that we came from the same parents, not least because she is obsessed with sport and I consider opening a book sufficiently sport-like to count as exercise. But I love my sister very dearly, and what I wanted Goda’s words to echo is what I feel about my sister: that even though we are so different we will always be sisters, our blood will always be shared, and that family flows through you whether you want it to or not.

Many years ago I read Eco’s The Name of the Rose; the monk Adso describes the peasant girl as ‘terrible as an army with banners’, and I thought it a most beautiful phrase. Years and more reading showed that it was originally from The Song of Solomon. I still love it; I used the phrase in my version of “Bluebeard”. The other translation, ‘terrible as an army arrayed for battle’, just seems to miss the right beat, doesn’t quite have the same beauty, although ‘arrayed’ is a beautiful word.

I find the phrase evocative and resonant, so much so I used it as the title of this story, which also owes some of its DNA to Eco’s wonderful book. I adore the idea of libraries, especially of medieval libraries as bastions of learning, as the places where knowledge was kept safe during the ‘Dark Ages’ (even though some of Eco’s monks let it get out of hand). What I like about my nuns at the Citadel of Cwen’s Reach is their determination to keep knowledge in the world because, good or bad, one day it might be needed. This is also the tale of a terrible destruction; it’s a chronicle of ending; it’s a letter of farewell, but, I pray, it’s also a statement of stubborn hope.

Terrible As An Army With Banners

Kathleen’s art

Dearest Elswide,

This is written in haste for the last boat is departing soon and I will not be on it, although I hope this will be. I beg you keep safe these pages, for they record an end – such an end, sister! Such an end – and I would have this chronicle kept safe. If you can, have it copied and sent forth so it may be found and read, and the truth of our demise – the last days of the Citadel at Cwen’s Reach – known.

You did not agree with my decision, sister, when I left home and joined the order. I know our silences have been long and fraught, but you are my blood and that counts for much. Your children are my family, too, and they should be told what I have done. They should know who the Little Sisters of St Florian were and they should be proud, though soon some will try to erase us from the world’s memory. Elswide, I did not desert you, I did not betray our shared heritage by leaving. I followed the path that was, to me at least, obviously laid out before me, but you have ever been in my thoughts. I’ve not forgotten you.

Please know that I have never regretted my decision, not even now when the end is upon me, not even when I can hear the sound of the siege engines at the gates. Know that I did the right thing and that my place was always meant to be as part of this community. I was always meant to have a quill in my hand and my nose pressed close to a blank page that begged to be covered with words. I was always meant to be here at the end. I write this knowing that I am a thing, a final thing, an omega.

Do not despair, sister, for in all endings there are new beginnings; from fire there comes new life, and from chaos, creation.

Your sister,

Goda

Amanuensis to Mater Dylis, last Mother Abbess of the Little Sisters of St Florian, The Citadel at Cwen’s Reach

*

Kathleen’s art

Know all you who read this that it is the recounting of the last days of the Citadel at Cwen’s Reach, the home for centuries past of the Little Sisters of St Florian, and their innermost circle the Blessed Wanderers, the Murcianii, whose diligence and bravery have brought so many books to us and therefore prevented their loss to the world. I write this now as events draw to a close – I would that you could hear the things I do as my pen scratches across the page: the roar of canons, the crackle of flames, the sounds of men dying in the streets outside our walls. All you need know of me is that I am Goda, Amanuensis to Mater Dylis, who shall be our last mistress. I have lived here for almost fifteen years, at first as a postulant, then as a novice, finally as a full Sister and scribe – not as one of the wanderers, though, for I was never so blest – but I have faithfully served as I may.

Know also that the Citadel has been a refuge for women of all ages, from all walks of life, those who fled and looked for something better. Some found a place with us, others rested and recovered and learned the skills to set them on a newer, safer path. Some came to seek the counsel of the most sacred Beatrice – although at the time they did not know it for her existence has always been a closely guarded secret – who has given guidance to our Maters for so many, many years. Some came to learn, some to teach. Some came for the wrong reasons but, in the end, learned the right ones. Others still came to us for the balm of eternal sleep and it was given with tenderness and compassion.

We have been a repository, a shrine, a home, a fortress. We have been a beacon of learning, custodians of knowledge that might otherwise have passed away. Until now we have been unbiased in what we have preserved. Until now we have never knowingly destroyed any book, but circumstances have removed the luxury of such openness and inclusion.

Kathleen’s art

For centuries, wars and battles have been waged around us by lords and kings, petty and powerful, forgotten and renowned, yet we remained inviolate, neutral, untouched by these ructions. Requests have been made of us by these rulers, and our decisions to either grant or refuse access to volumes or scrolls or other such records, have been accepted and respected, if not happily received. Our walls have never been breached, we have never been attacked, and no man has ever set foot in the shrine of the caput mundi.

But now this man, this strange man, this darkness made flesh of whom Beatrice warned us almost too late, is coming. This terrible man who, it is whispered, has lived well beyond his time. This man who has refused to take no for an answer.

***

April 1, 2015

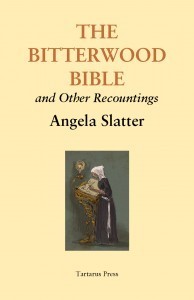

The Bitterwood Posts: The Bitterwood Bible

Kathleen’s art

“The Bitterwood Bible” was always going to be an important story in this collection because it tells the history of the actual Bitterwood Bible and Murciana who made it. I’d given a lot of thought to Murciana because in Sourdough and Other Stories (the sequel to Bitterwood), she is referred to as Murcianus – indeed, there’s a whole library of books attributed to the almost-mythical-by-that-stage male author Murcianus. Even when I was writing Sourdough, I knew that that the usual kind of colonisation had occurred, that something created by a woman had been found to be so grand and widespread that it couldn’t be stamped out or eradicated … so it’s been appropriated and attributed to a man.

Throughout both collections there are a lot of magic books referred to and all are some version of Murciana’s Bitterwood Bible, even the grimoire used by Patience and Wynne Sykes in Sourdough (“Gallowberries” – and also in my soon-to-be-published Tor.com novella Of Sorrow and Such), known as Murcianus’ Book of Magica. One day I will write the tale of Sister Benedicte, who was tasked with copying the book and then stole it away. In this world there are all sorts of copies of this book, partial and full and annotated and extended … all to keep the knowledge in the world and all repurposed by their owners.

Kathleen’s art

I’d thought a lot about where Murciana came from and in the end it felt right to show how she arrived at the Citadel of Cwen’s Reach with the Little Sisters of St Florian. I could have started anywhere in her life, I suppose, even back to when she was the daughter of the vampires in “The Night Stair” (before they were vampires), but somehow showing her at the moment when she comes to the Citadel seemed right: she brought history with her, she was at a point where she might have decided to embrace terrible things, but instead she was offered a much better choice.

The Bitterwood Bible

All stories have a beginning, but beginnings themselves have many sparks, some slow to catch, others forest-fire fast.

Does this tale begin three hundred years ago, give or take, with the small child stolen from her parents? Does it begin the moment she ceases to cry for them, starts to forget them, loses her determination to find them again – for the best, really, so she will never know what they become? Does it begin when she is first ordered to pick up a quill, punished until she forms her letters correctly, beautifully? Does it begin when she starts to regard as hers the book in which she records everything for her master?

Or does it begin here, at the base of the cliff? At the breach through which only she can fit? Or in the tunnels that climb upward, honeycombing the substance of the promontory of Cwen’s Reach, upon which the Citadel sits?

Murciana’s palm is sweaty as she grips the torch, despite the glacial cold creeping through the tunnels. She makes dragon’s breath with every exhalation, and her lungs ache from the icy air she takes in. Beneath the soles of her shoes, the ground is a mix of rubble and rime, depending on how much seawater has flowed through. The passages are thin, in some places she must turn her scrawny self sideways to pass by – even if there’d been no other reason for her to undertake this mission, her master would never have fit through half these ways. She has to be careful with the satchel, adjusting it this way and that so its contents are not bumped and damaged.

Kathleen’s art

Her other hand is equally sweaty, wrapped as it is around the ivory hilt of the misericorde, which she holds ahead of herself. Her master offered the knife, casually at the very last minute – he has never let her near weapons before, certainly not handed her one – along with the advice that she might encounter some kinds of creatures in the tunnels, perchance large rats, smaller wild cats, mayhap even a troll or ogre – they liked dark places, although she shouldn’t worry too much as neither of the last three was overly fond of either sea or water. Oh, and she should look out for crevasses, subterranean lakes, uncertain earth and rock falls. With that he heaved her upwards and through the slim aperture, waiting only to pass the torch and dagger to her when her thin-wristed, ink-stained hand reappeared, questing for the light.

So far no crevasses, subterranean lakes, uncertain earth, nor rock falls. No large rats or even little ones, no smaller wild cats, nor troll nor ogre, although there had been times when she’d been certain of a stealthy footstep behind her, and she’d swung about, torch held high, blade jabbing at the dancing shadows. But there was nothing either mundane nor arcane trying to make itself known. She was alone, in the darkness, in the heart of a cliff, climbing upwards to ask questions of a thing of which she cannot quite conceive, although gods knew she’d seen enough miracles great and terrible in her short life.

‘It will only speak to you,’ her master had said as they’d trekked across marshlands and plains, through forests, up hill and over dale, until they came to that port city of Breakwater and negotiated passage to a small inlet half a day’s journey from Cwen’s Reach. Far enough away, he’d sworn, that they wouldn’t be noticed in the city of the Citadel. Another long walk along the ridges and clifftops, then down a rugged path and onto the sand and pebbles, struggling and stumbling until at last they came to the wide mouth of a cave. Inside the Magister cast a spell, throwing magelight across the damp dark space and searching until he found the ramp of scree that led up the hole in the rock wall.

‘It will only speak to another woman.’

‘That doesn’t mean it will speak to me,’ she said quite reasonably and was rewarded with a glare. ‘I only mean to say, Magister, that just because I’m female doesn’t guarantee its cooperation. What if it wants to know why I’m asking these questions? Why I’m copying down these spells? What do I plan to do with them? Surely saying “I shall give them into the hands of my master” will not be viewed well?’

She knew she was courting a beating, but couldn’t quite help herself, not even after all this time. She wondered that part of her refused to submit, to be obedient.

‘Just ask it the questions, and write down the answers. It won’t hurt you, but Gods help you if you return empty-handed.’

It seems she’d been climbing for hours, and in her mind she goes over the questions she must ask. They form a kind of rhythm for her footsteps, even as she worries at them, concerned that the word order will escape her – they must be spoken firmly, confidently, insisted the Magister, not read out. Aloud, she almost sings:

How to transform things for a season?

How to kill without trace?

How to live beyond one’s time?

She wonders if she might ask questions of her own? Would the Magister even know if she tried? After she’s asked his questions, obviously, those to which she must bring back answers.

Some while ago the sloping path had given way to steps, at first rough-hewn, but as she rose higher their craftsmanship grew, the precision of cut and placement increased, the materials changing from rock, to polished stone, to something that looked like marble and sparkled in the light from her torch. The walls grew smoother, the passages broadened, showing obvious signs of tool marks, of someone caring how this area looked. And soon enough she began to hear a low rumble, the timbre of a voice echoing in an enclosed space.

When she comes at last to a dead end, she reaches out and feels about, taking so long to find the catch that she thinks perhaps the Magister’s information had been incorrect. That she will have to go back through the winding underworld of the tunnels and bring him nothing after all his months and years of research and planning. That she will dash all his great hopes of finding what the tinker had told him was rumoured to be held in the deepest, most secret room of the Citadel. As she despairs, her fingers catch at it, the cold carven hook, which she pulls and feels it click.

There is a grinding, the painful sound of a mechanism unused for many years, and then the floor beneath her tips so she slips and is thrown forward into the space where the wall had been. She loses both knife and torch in the fall, and the bag lands heavily on her, knocking the wind from her. And she makes a noise, such a noise, with the dropping and the falling and the whumping.

Still and all, it doesn’t seem to bother the women watching her too much. Well, the woman and her companion, who is also female – looks female – but lacks everything except a head. The woman, the actual one, has half-risen from a low stone bench that encircles the basin where the other’s head floats on a sea of fire. Or is it cloud, all saffron-hued and red-streaked? On closer inspection, it is a kind of pond, not too deep, but filled with roiling, aggressive fire-clouds, yet the head does not bob, is not buffeted, simply levitates, hovering in the same spot, looking at Murciana with curiosity but not disdain, not fear. That gives the girl heart, which surprises her.

‘Good evening,’ says the woman in a low, rich voice.

‘Good evening,’ echoes the head, in an equally mellifluous tone.

Scrambling to her feet, readjusting the heavy satchel, Murciana manages to nod several times before she stutters out an appropriate greeting. All eyes turn to the torch which is guttering on the ground and the misericorde, whose thin blade seems blood-covered in the ruby light. Suddenly, Murciana feels unutterably rude – it isn’t a sensation with which she is too familiar, having not been trained in etiquette and having devoted large amounts of her time to perfecting a sly disrespect where the Magister is concerned. But before these women who’ve not batted an eyelid at her sudden arrival she feels callow and impolite.

***

March 30, 2015

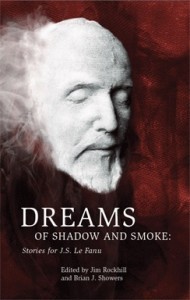

Huzzah for Dreams of Shadow and Smoke!

Many and warm congrats to Messrs Brian J. Showers and Jim Rockhill of Swan River Press – their J Sheridan Le Fanu tribute anthology, Dreams of Shadow and Smoke, has won Best Ghost Story Book for 2014 (in 2015, as is the way of such things)!!

Many and warm congrats to Messrs Brian J. Showers and Jim Rockhill of Swan River Press – their J Sheridan Le Fanu tribute anthology, Dreams of Shadow and Smoke, has won Best Ghost Story Book for 2014 (in 2015, as is the way of such things)!!

I believe there are a few copies of this beautiful limited edition remaining. Go here – you know you want to.

Contents

“A Preliminary Word” – Jim Rockhill & Brian J. Showers

“Seaweed Tea” – Mark Valentine

“Let the Words Take You” – Angela Slatter

“Some Houses — A Rumination” – Brian J. Showers

“Echoes” – Martin Hayes

“Alicia Harker’s Story” – Sarah LeFanu

“Three Tales from a Townland” – Derek John

“The Corner Lot” – Lynda E. Rucker

“Rite of Possession” – Gavin Selerie

“A Cold Vehicle for the Marvellous” – Emma Darwin

“Princess on the Highway” – Peter Bell

“Story Notes” – “Biographical Notes”

“Acknowledgements”

March 29, 2015

The Bitterwood Posts: St Dymphna’s School for Poison Girls

Art by Kathleen Jennings

The title for this story came from a friend’s throwaway line about St Dymphna’s Home for the Wealthy Insane (thanks, Dr Carson). I thought “No, St Dymphna’s Home for Poison Girls” and my mind went off on its own and sat in a corner, conjuring visions of a boarding school like the one in Charlotte Brontë’s Villette except with more murder and fewer French lessons.

I thought about finishing schools for young ladies and the sorts of girls who are sent there, and the kinds of families they come from. I thought about the strife between grand houses caused by matters of pride and honour (not to mention thefts), and wondered what might happen if the female offspring from those grand houses might be taught something useful … which was still misused by said houses. I wondered about the sorts of young women who might not think beyond what their families were sending them to do, who didn’t say to themselves “Sod this for a game of soldiers – I’ve just been taught these great and terrible skills by independent and terrifying women, why should I go off to die in the service of my family? Why shouldn’t I too become an independent and terrifying woman?”

Which is precisely the sort of thing Mercia does think for she’s not one of the herd, although in the end she follows a different path as well. And she’s also been sent off to do something dangerous by her surrogate family, the Little Sisters of St Florian, so in some ways she’s also a pawn but smart enough to break away. Mercia is the youngest daughter of Wulfwyn from “The Burnt Moon”, and the youngest sister of Delling, who frees the ghosts of Southarp in “The Undone and the Divine”. She appears again in the new collection The Tallow-Wife and Other Tales. This story first appeared in The Review of Australian Fiction, Volume 9, Issue 3 – and is shortlisted for Best Fantasy Short Story at this year’s Aurealis Awards.

Art by Kathleen Jennings

St Dymphna’s School for Poison Girls

‘They say Lady Isabella Carew, née Abingdon, was married for twenty-two years before she took her revenge,’ breathes Serafine. Ever since we were collected, she, Adia and Veronica have been trading stories of those who went before us – the closer we get to our destination, the faster they come.

Veronica takes up the thread. ‘It’s true! She murdered her own son – her only child! – on the eve of his twenty-first birthday, to wipe out the line and avenge a two-hundred year old slight by the Carews to the Abingdons.’

Adia continues, ‘She went to the gallows, head held high, spirit unbowed, for she had done her duty by her family, and her name.’

On this long carriage journey I have heard many such recountings, of matrimony and murder, and filed them away for recording later on when I am alone, for they will greatly enrich the Books of Lives at the Citadel. The Countess of Malden who poisoned all forty-seven of her in-laws at a single banquet. The Dowager of Rosebery, who burned the ancestral home of her enemies to the ground, before jumping from the sea cliffs rather than submit to trial by her lessers. The Marquise of Angel Down, who lured her father-in-law to one of the castle dungeons and locked him in, leaving him to starve to death – when he was finally found, he’d chewed on his own arm, the teeth marks dreadful to behold. Such have been the bedtime tales of my companions’ lives; their heroines affix heads to the ground with spikes, serve tainted broth to children, move quietly among their marriage-kin, waiting for the right moment to strike. I have no such anecdotes to tell.

On this long carriage journey I have heard many such recountings, of matrimony and murder, and filed them away for recording later on when I am alone, for they will greatly enrich the Books of Lives at the Citadel. The Countess of Malden who poisoned all forty-seven of her in-laws at a single banquet. The Dowager of Rosebery, who burned the ancestral home of her enemies to the ground, before jumping from the sea cliffs rather than submit to trial by her lessers. The Marquise of Angel Down, who lured her father-in-law to one of the castle dungeons and locked him in, leaving him to starve to death – when he was finally found, he’d chewed on his own arm, the teeth marks dreadful to behold. Such have been the bedtime tales of my companions’ lives; their heroines affix heads to the ground with spikes, serve tainted broth to children, move quietly among their marriage-kin, waiting for the right moment to strike. I have no such anecdotes to tell.

The carriage slows as we pass through Alder’s Well, which is small and neat, perhaps thirty houses of varied size, pomp, and prosperity. None is a hovel. It seems life for even the lowest on the social rung here is not mean – that St Dymphna’s, a fine finishing school for young ladies as far as the world-at-large is concerned, has brought prosperity. There is a pretty wooden church with gravestones dotting its yard, two or three respectable mausoleums, and all surrounded by a moss-encrusted stone wall. Smoke from the smithy’s forge floats against the late afternoon sky. There is a market square and I can divine shingles outside shops: a butcher, a baker, a seamstress, an apothecary. Next we rumble past an ostlery, which seems to bustle, then a tiny school house bereft of children at this hour. So much to take in but I know I miss most of the details for I am tired. The coachman whips up the horses now we are through the hamlet.

I’m about to lean back against the uncomfortable leather seat when I catch sight of it – the well for which the place is named. I should think more on it, for it’s the thing, the thing connected to my true purpose, but I am distracted by the tree beside it: I think I see a man. He stands, cruciform, against the alder trunk, arms stretched along branches, held in place with vines, which may be mistletoe. Green barbs and braces and ropes, not just holding him upright, but breaching his flesh, moving through his skin, making merry with his limbs, melding with muscles and veins. His head is cocked to one side, eyes closed, then open, then closed again. I blink and all is gone, there is just the tree alone, strangled by devil’s fuge.

I’m about to lean back against the uncomfortable leather seat when I catch sight of it – the well for which the place is named. I should think more on it, for it’s the thing, the thing connected to my true purpose, but I am distracted by the tree beside it: I think I see a man. He stands, cruciform, against the alder trunk, arms stretched along branches, held in place with vines, which may be mistletoe. Green barbs and braces and ropes, not just holding him upright, but breaching his flesh, moving through his skin, making merry with his limbs, melding with muscles and veins. His head is cocked to one side, eyes closed, then open, then closed again. I blink and all is gone, there is just the tree alone, strangled by devil’s fuge.

My comrades have taken no notice of our surrounds, but continue to chatter amongst themselves. Adia and Serafine worry at the pintucks of their grey blouses, rearrange the folds of their long charcoal skirts, check that their buttoned black boots are polished to a high shine. Sweet-faced Veronica turns to me and reties the thin forest green ribbon encircling my collar, trying to make it sit flat, trying to make it neat and perfect. But, with our acquaintance so short, she cannot yet know that I defy tidiness: a freshly pressed shirt, skirt or dress coming near me will develop wrinkles in the blink of an eye; a clean apron will attract smudges and stains as soon as it is tied about my waist; a shoe, having barely touched my foot, will scuff itself and a beribboned sandal will snap its straps as soon as look at me. My hair is a mass of – well, not even curls, but waves, awkward, thick, choppy, rebellious waves of deepest fox-red that will consent to brushing once a week and no more, lest it turn into a halo of frizz. I suspect it never really recovered from being shaved off for the weaving of Mother’s shroud; I seem to recall before then it was quite tame, quite straight. And, despite my best efforts, beneath my nails can still be seen the half-moons of indigo ink I mixed for the marginalia Mater Friðuswith needed done before I left. It will fade, but slowly.

The carriage gives a bump and a thump as it pulls off the packed earth of the main road and takes to a trail barely discernable through over-long grass. It almost interrupts Adia in her telling of the new bride who, so anxious to be done with her duty, plunged one of her pearl-tipped, steel-reinforced veil-pins into her new husband’s heart before ‘Volo’ had barely left his lips. The wheels might protest at water-filled ruts, large stones and the like in their path, but the driver knows this thoroughfare well despite its camouflage; he directs the nimble horses to swerve so they avoid any obstacles. On both sides, the trees rushing past are many and dense. It is seems a painfully long time before the house shows itself as we take the curved drive at increased speed, as if the coachman is determined to tip us all out as soon as possible and get himself back home to Alder’s Well.

***

March 26, 2015

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

Another cracking read from Paula Guran and Prime Books! Collecting some outstanding reprints, this anthology is available for order here.

Another cracking read from Paula Guran and Prime Books! Collecting some outstanding reprints, this anthology is available for order here.

CONTENTS:

The Same Deep Waters As You • Brian Hodge

Mysterium Tremendum • Laird Barron

The Transition of Elizabeth Haskings • Caitlín R. Kiernan

Bloom • John Langan

At Home With Azathoth • John Shirley

The Litany of Earth • Ruthanna Emrys

Necrotic Cove • Lois Gresh

On Ice • Simon Strantzas

The Wreck of the Charles Dexter Ward • Elizabeth Bear & Sarah Monette

All My Love, A Fishhook • Helen Marshall

The Doom That Came to Devil Reef • Don Webb

Momma Durtt • Michael Shea

They Smell of Thunder • W.H. Pugmire

The Song of Sighs • Angela Slatter

Fishwife • Carrie Vaughn

In the House of the Hummingbirds • Silvia Moreno-Garcia

Who Looks Back? • Kyla Ward

Equoid • Charles Stross

The Boy Who Followed Lovecraft • Marc Laidlaw

Singing Her Scars: Damien Angelica Walters

Damien Angelica Walters’ short fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in various anthologies and magazines, including The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy & Horror 2015, Year’s Best Weird Fiction Volume One, Cassilda’s Song, Nightmare, Strange Horizons, and Apex. “The Floating Girls: A Documentary,” originally published in Jamais Vu, is on the 2014 Bram Stoker Award ballot for Superior Achievement in Short Fiction.

Damien Angelica Walters’ short fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in various anthologies and magazines, including The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy & Horror 2015, Year’s Best Weird Fiction Volume One, Cassilda’s Song, Nightmare, Strange Horizons, and Apex. “The Floating Girls: A Documentary,” originally published in Jamais Vu, is on the 2014 Bram Stoker Award ballot for Superior Achievement in Short Fiction.

Sing Me Your Scars, a collection of her short fiction, is out now from Apex Publications, and Paper Tigers, a novel, is forthcoming from Dark House Press. You can find her on Twitter @DamienAWalters or online at http://damienangelicawalters.com.

What do readers need to know about Damien Angelica Walters, and which story of yours would you recommend to a new reader?

DAW: I fear I’m much like most writers—an introvert, a bookworm, a drinker of too much coffee, and a fan of dinosaurs and Alien.

For those unfamiliar with my work, Like Origami in Water would be a good story to start with, I think. It’s an older story and while my authorial voice has matured a bit, I think it showcases the tone of my short fiction well. It’s short, too, at just about 1,500 words, so it’s a quick read.

Who were/are your literary heroes/influences?

DAW: Joyce Carol Oates, Stephen King, Shirley Jackson, Mary Shelley, Margaret Atwood, Peter Straub, Ray Bradbury, Jacqueline Carey, Gillian Flynn, Cormac McCarthy, Kij Johnson, Catherynne Valente, Kelly Link, Laird Barron, John Langan, and Ken Liu are some of the writers who’ve either inspired me or influenced me or left me in awe of their skill. Genre fiction holds a jaw-dropping wealth of talent.

Where did the inspiration for Sing Me Your Scars spring from?

DAW: Do you remember all those hateful memes about real women? Real women look like this, no, they look like that… For a time it felt like I saw a different one every day (mostly posted by men), all with this perceived ideal of feminine perfection and each time, my frustration grew. That frustration turned into a sentence – This is not my body. – and then into a paragraph and then into the story itself.

What was the story/book that made you think ‘I want to write!’?

DAW: I don’t think it was one specific book, but a cumulative effect of everything I read, both genre and non-genre, both good and bad. I remember creating illustrated books when I was in third grade and trying to sell them to the other kids in the neighborhood. While I’m fairly certain the books were about ghosts and other creepy things, sadly, none of them survived my childhood.

Name five fictional characters you’d invite over for coffee and cake?

DAW: Phèdre nó Delaunay de Montrève from Jacqueline Carey’s Kushiel’s Dart, Offred from Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, the nameless main character from Jacqueline Harpman’s I Who Have Never Known Men, Rose McClendon from Stephen King’s Rose Madder, and Ludwig Von Sacher from Kirsten Bakis’ Lives of the Monster Dogs.

Are there any of your own characters that you think you’d like to revisit in longer form at some point?

Are there any of your own characters that you think you’d like to revisit in longer form at some point?

DAW: I’ve been toying with the idea of turning The Floating Girls: A Documentary into a novel, but at this point I’m still jotting ideas down to see if it’s viable or not. My fear is that even with the addition of new characters and a larger storyline comprised of events that occur before and after the events in the short story, the central story won’t translate well to a longer work.

What first drew you to write horror rather than any other genre?

DAW: It wasn’t a conscious choice, to be sure, but I grew up reading fairy tales and Lois Duncan and when I was eleven, I read Stephen King’s The Shining. Given that my tastes as a reader always skewed to the dark, it was a given that what I wrote would follow suit.

Who’s your favourite villain in fiction?

DAW: That’s a hard question to answer. I think it’s a tie between Coleman Collins from Peter Straub’s Shadowland and the Overlook Hotel in Stephen King’s The Shining. Uncle Cole should be all magic tricks and letting the boys stay up too late with ice cream for dinner and cake for desert; he shouldn’t be crucifixion and mermaid girls and glass birds.

And the Overlook should be rooms and ugly carpet and a big kitchen; it shouldn’t be blood on the walls, fire extinguishers that become snakes when you’re not looking, and it most definitely should not be able to exploit your father’s greatest weakness and turn him against you.

What’s your favourite short story ever and why?

DAW: Another tough question, and I’m going to cheat a bit and give you two. As far as the classics go, I’ll say The Lottery by Shirley Jackson. It’s masterful the way it draws you into a seemingly normal village, even if the gathering of the stones is disquieting. But the townspeople don’t seem worried overmuch, so it’s easy to brush that off. The story pulls the rug out from under you by slow degrees and then at the end, it leaves you suspended in the air and ready to drop with Mrs. Hutchinson. The slow burn coupled with keeping the carnage off-screen works beautifully.

For newer fiction, Spar by Kij Johnson is brilliant. If you read it quickly, you might be inclined to dismiss it as vulgar or tentacle porn, but if you read it closely, you see the true story underneath. It’s about communication, or the lack thereof, and how destructive, how paralyzing, that can be. It’s masterful.

What’s next for Damien Angelica Walters?

What’s next for Damien Angelica Walters?

DAW: I have several short stories and a portmanteau novel currently in the works. I’m also trying to plot another novel about monsters, love, hate, and revenge. I’ve never plotted a novel before so I may or may not be successful, but my novel first drafts are always a mess and I’d love to find a way to make them a bit cleaner.

Publication-wise, Paper Tigers, a novel, will be out later this year from Dark House Press, and I’ve short fiction forthcoming in several anthologies and magazines, including Cassilda’s Song, edited by Joe Pulver, a King in Yellow anthology of all new stories written by women, The Mammoth Book of Cthulhu: New Lovecraftian Fiction, edited by Paula Guran, and Black Static.

March 22, 2015

The Bitterwood Posts: Now, All Pirates are Gone

Art by Kathleen Jennings

In Sourdough and Other Stories, there is a tale called “The Navigator”, about ships and sirens and men with wings who act as navigators for said ships. There is a nameless narrator who may or may not die at the end, and who may or may not be a pirate … but there are definitely pirates in that world. I had the title, “Now, All Pirates Are Gone” scribbled down for another story that never made it into Sourdough.

When I was writing Bitterwood, I went back to my Sourdough notes and found that title and knew that it belonged in the new collection. I wanted a pirate story that was a bit more than seeking lost treasure and run-ins with the authorities. I thought about how Royal Navies were always trying to wipe them out, and I wondered about how someone might succeed. I found the tale of the ghost ship Caleuche in Chilote mythology and that gave me the name of the mysterious island. I knew I wanted to connect this tale with the action of “By My Voice I Shall Be Known”, and the unknown protagonist’s line ‘How long before she, too, chooses the water?’

I love my pirates. I love Maude and Sancha and Hieronymus the cat. I’m very fond of Edine, though she’s both stupid and dangerous.

Now, All Pirates are Gone

The sea is strangely silent tonight and this makes Maude and her crew nervous.

Beneath their collective worn canvas shoes, bare feet, and thick soled boots, the brig’s deck is steady as Astra’s Light moves through the waters with nary a noise, and only the slightest shhhh’ing as the bow splits the flat mirror of liquid salt. Ahead of them, the island lies low, relaxed, a dark hunched thing against the blue-black sky, seemingly boneless as those chickens Maude’s aunt sometimes bred, the ones that weren’t quite right. But from the centre of Isla Caleuche rises a tower, straight and tall as a luring finger, saying Come hither.

The breeze that pushes them toward their goal is strong, warm – indeed, hot – and the night air is humid. Maude wipes at her face with an embroidered kerchief. The thing was not meant for such rough use and is frayed, discoloured after five hard years. Soon it will be little more than a rag, but she won’t discard it for it was a gift from the mute woman with auburn-rose hair they’d plucked from the sea, back when the oceans were kind and full of bounty. When the business of piracy was at its peak and all but the worst captains could afford to, and did, display some compassion and a reasonable degree of generosity. The folk of the Astra’s Light didn’t know how long the woman had floated, and they couldn’t figure how she hadn’t drowned, but her skin had turned as furrowed as a crone’s frown and it took days of pouring fresh water into her mouth and applying rich unguents (from Maude’s own stock, thank you very much) to make her even begin to look human once more.

Grateful, the woman had made herself useful – darning ragged pants, shirts and skirts, socks and stockings. Making serviceable bunk-blankets for the whole crew out of the worsted wool, calico and felt from an Argosy they’d “lightened” but days before; and a fine coverlet of green and gold brocatelle for Maude and Sancha’s bed. Men and women all began to regard her as something of a mascot, a pet to replace the cat that had disappeared in a storm a week earlier. The woman couldn’t write or speak, so Sancha had begun teaching her letters. By the time they’d set her ashore at Cwen’s Reach, she’d made a silken shawl for Sancha and the fine cambric kerchief for the captain, Maude’s initials embroidered in one corner and cleverly stitched now-mermaids-now-maidens gambolling around the edges, tail to feet and back again. Maude, who had the full complement of sailors’ superstitions to give her ballast, came to regard the piece of fabric as something of a lucky charm. In her career, she’d had her share of accidents – a shoulder dislocated from hanging out a window, stab wounds from any number of ill-wishers and naval men, powder burns from unexpected and inconvenient explosions – but from the day the kerchief came into her possession she’d been unusually incident- and injury-free.

When they’d made harbour at Cwen’s, Sancha had accompanied the woman, and left her with one of the Little Sisters of St Florian at the Citadel – which was the closest thing to a charitable institution the port town had. It seemed like the best place, Sancha later said, as she showed Maude the new ship’s cat she’d acquired, a black and gold kitten five months or so old, standoffish and wise as it sat on the bed beside them, observing their state of undress with a kind of disdain. Or perhaps the distaste was for her name: Hieronymus.

It was only some time after she’d gone, the woman, and the seas seemed to change their tenor, that they wondered if she was the beginning of their ruin.

***