Angela Slatter's Blog, page 80

July 26, 2015

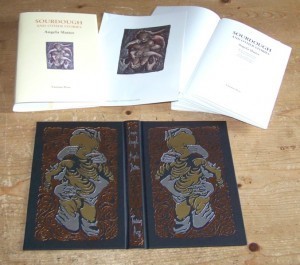

Another Bitterwood Bible Giveaway!

Lisa’s photo

To mark Bitterwood’s shortlisting for the World Fantasy Awards, Tartarus Press and I are celebrating by giving away another copy of the increasingly rare limited edition hardcover of The Bitterwood Bible and Other Recountings (we’re down to roughly the last one hundred copies), with illustrations by Kathleen Jennings, Introduction by Stephen Jones, and Afterword by Lisa L. Hannett.

To enter, click here and then click the very complicated Enter Giveaway button at Goodreads (even I can do it and I am challenged by the toaster).

Should you feel moved to actually purchase a copy, you can do so here at Tartarus’ brand spanking new site.

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories: Stephen Volk

Stephen Volk is the author of the superb novellas, Whitstable and Leytontone, as well as a screenwriter of note, having written Ghostwatch, Afterlife, and Gothic. He’s won BAFTAs and British Fantasy Awards and is generally delightful.

Stephen Volk is the author of the superb novellas, Whitstable and Leytontone, as well as a screenwriter of note, having written Ghostwatch, Afterlife, and Gothic. He’s won BAFTAs and British Fantasy Awards and is generally delightful.

What inspired your story “Wrong”?

I don’t want to give too much away, because I don’t want the reader to know what’s coming, but it was directly inspired by something that happened in my home town a few years ago. The way prurient gossip surrounds this kind of thing, and the attendant moral outrage, made me think it was the core of an unusual story, but I didn’t know how to tell it until I combined it with my memories of student life. The two things seemed to gel and make it work, I hope.

What’s the first horror story you can remember making a big impact on you?

Possibly “Enoch” by Robert Bloch, because it was the first story in the paperback tie-in to the Amicus film Torture Garden. I remember the thrill of realising it took me inside the mind of somebody mad. It was the first paperback I bought with my pocket money instead of comics and it felt like forbidden fruit.

Name your three favourite horror writers.

Tomorrow it might be three different ones, but today it’s Richard Matheson, Mark Morris and (unfashionably) Dennis Wheatley.

Is your writing generally firmly in the horror arena or do you do occasional jaunts into other areas of speculative fiction?

I’ve written stories that are crime (arguably my novellas Whitstable and Leytonstone) and science fiction/fantasy screenplays such as adaptations of The Box of Delights and The Chrysalids but I’m most at home in the supernatural and psychological. But I go where the story takes me. I don’t really think when I’m writing a story that it has to be “horror” – Mark said this story, “Wrong”, for instance “wasn’t really horror but was horror”: which I take as a great compliment! My wife doesn’t think I write horror, as a matter of fact, but that’s to do with her definition. I’m happy to be called a horror writer because it is the glove that fits me best, but happy to be just called a writer too.

What’s in your to-be-read pile at the moment?

John Connolly’s Nocturnes, Mark Morris’s The Wolves of London, Marion Couts’s The Iceberg, Sarah Pinborough’s The Death House, and The Shining: Studies in the Horror Film edited by Danel Olson. What’s at the top of the pile always shifts around depending what I’ve just read and what I fancy reading next.

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories can be pre-ordered here.

July 23, 2015

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories: Lisa L. Hannett

Lisa L. Hannett has had over 60 short stories appear in venues including Clarkesworld, Fantasy, Weird Tales, Apex, the Year’s Best Australian Fantasy and Horror, and Imaginarium: Best Canadian Speculative Writing. She has won four Aurealis Awards, including Best Collection for her first book, Bluegrass Symphony, which was also nominated for a World Fantasy Award. Her first novel, Lament for the Afterlife, was published by CZP in 2015. You can find her online at http://lisahannett.com and on Twitter @LisaLHannett.

What inspired your story “Sugared Heat”?

I often think about how, as a kid in Canada, I’d go on school trips out to the sugar bush to tap maple trees for syrup. (There were taps plugged right into the trees! And we’d pack snow onto popsicle sticks and drip syrup right onto them!) I was also thinking about really small, really isolated towns (again, as I often do) and the lengths to which the people who lived in them might go to avoid too much inbreeding. (Assuming they’d be okay with a bit of inbreeding, of course.) At the same time, I’d been thinking a lot about dryads, and also about terrible skin afflictions — and wouldn’t tree bark make an excellent back-scratcher, if you got hold of a big enough slab? But surely the dryads wouldn’t be all that keen on giving up their bark, I thought. Maybe it would be better if you stripped down and rubbed up against them … which sent the story spiralling in a much darker direction than I expected, given that the whole train of thought kicked off with kids and maple snow-popsicles.

What’s the first horror story you can remember making a big impact on you?

I Am Legend, by Richard Matheson. (The book, not the film, which was dreadful.) The way those vampires taunted Neville when he was barricaded inside his house at night has stuck with me for years. It was such an inhuman — but human —thing they did to him. Brilliant psychological horror.

Name your three favourite horror writers.

Shirley Jackson. Robert Shearman.[Insert all other horror writers here because how can I narrow it down to three? What a cruel, cruel task.]

Is your writing generally firmly in the horror arena or do you do occasional jaunts into other areas of speculative fiction?

I like the umbrella term ‘speculative fiction’ because it’s broad (and unspecific) enough to encompass all of the sorts of stories I write. My work is mostly strange, sometimes creepy, often unsettling — all trademarks of horror, I suppose — but I rarely consciously sit down in front of my computer and think, ‘Today, I’m going to write horror.’ (Or fantasy / science fiction, for what it’s worth.) Bluegrass Symphony contains stories I thought maybe were mostly fantasy, but they’ve also been received as horror (‘The Short Go: A Future in Eight Seconds’ won ‘Best Horror Short Story’ at the 2011 Aurealis Awards; meanwhile the collection itself was nominated for a World Fantasy Award.) Midnight and Moonshine is pretty firmly fantasy, and The Female Factory is science fiction in that its stories rely on scientific concepts and questions— but there is nary a spaceship or planet (other than Earth) to be found in that collection. All of my uncollected stories straddle the fantasy/science fiction/horror borderlines, too. The ones I think might be science fiction get bought by horror venues, the ones I think are horror get bought by fantasy markets, the ones I think are fantasy wind up as something in-between. And then there’s Lament for the Afterlife, my first novel, which is a mid-apocalyptic dark fantasy horror war story. Think Platoon meets Pan’s Labyrinth meets Things We Didn’t See Coming, and that starts to describe it…

What’s in your to-be-read pile at the moment?

I’m 95% of the way through The Anchoress by Robyn Cadwallader, so that’s at the top. I’m also partway through The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro, so that’s next. I’m also well into Redeployment by Phil Klay, which I’m reading slowly so that it lasts longer, but I’ll have to get to the end sooner or later. After that I want to re-read Hild by Nicola Griffith (because I devoured it the first time, and now want to savour it). Then I’ve got Sweetland by Michael Crummey lined up (whose previous book, Galore, is one of my favourites of all time). I also want to read Archivist Wasp by Nicole Kornher-Stace.

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories can be pre-ordered here.

July 22, 2015

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories: Nicholas Royle

The delightful Nicholas Royle is a novelist, creative writing lecturer, reviewer, editor and publisher of Nightjar Press. Here he takes some time to chat about his story “The Larder”.

The delightful Nicholas Royle is a novelist, creative writing lecturer, reviewer, editor and publisher of Nightjar Press. Here he takes some time to chat about his story “The Larder”.

What inspired your story “The Larder”?

If I were to say precisely what inspired “The Larder” it would kind of give the game away, so I’ll just say my love of birds. But also my love of the Observer’s books, a series of British pocket-sized books published between 1937 and 2003. In particular I liked the Observer’s Book of Birds and the Observer’s Book of Birds’ Eggs.

What’s the first horror story you can remember making a big impact on you?

Not strictly speaking a horror story, but I found it horrifying and, now that I look back, I realise it inspired much of what I’ve been writing about in the last 30 years. It was a comic strip story featuring Pixie and Dixie and Mr Jinks in, I think, the 1968 Huckleberry Hound Annual featuring a dressmaker’s dummy that was made to appear to have a mind of its own.

Name your three favourite horror writers.

Joel Lane, Alison Moore, Dennis Etchison.

Is your writing generally firmly in the horror arena or do you do occasional jaunts into other areas of speculative fiction?

I write in and on the borders of lots of different genres, but mainly horror, crime, mystery and literary fiction.

What’s in your to-be-read pile at the moment?

Noir by Robert Coover. Also a range of short stories by British writers published last year, from which I’m selecting the contents of Best British Short Stories 2016 (Salt). I’m judging some prizes, so I have a lot of reading for those – the Lightship First Novel Prize, the Novella Prize and the Manchester Fiction Prize.

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories can be pre-ordered here.

July 21, 2015

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories: Thana Niveau

Thana Niveau is a Halloween bride who lives in a crumbling gothic tower in Wicker Man country. She shares her life with fellow horror scribe John Llewellyn Probert, in a Victorian library filled with arcane books and curiosities. She has twice been nominated for the British Fantasy award, for her collection From Hell to Eternity and for her short story “Death Walks En Pointe”.

Thana Niveau is a Halloween bride who lives in a crumbling gothic tower in Wicker Man country. She shares her life with fellow horror scribe John Llewellyn Probert, in a Victorian library filled with arcane books and curiosities. She has twice been nominated for the British Fantasy award, for her collection From Hell to Eternity and for her short story “Death Walks En Pointe”.

What inspired your story “Behind the Wall”?

The origin of this story is bittersweet. Shortly after my friend Joel Lane died, I had a strange dream. My husband John and I had bought a new house in an isolated village and someone told us we could keep Joel alive by walling off a room in the house and imagining that he was there behind it, still writing. In the dream the idea was both creepy and comforting and we were about to start work on it when I woke up.

It wasn’t at all my usual kind of dream (mine tend to be both more surreal and overtly threatening) and I had the strangest notion that it was a gift from Joel. I don’t believe in god or heaven but I do believe that we have souls, an essence that is uniquely “us”. That essence has to go somewhere when we die. Perhaps it simply gets re-absorbed into the universe. Or perhaps it gets dispersed among your loved ones. If so, I hope everyone who loved Joel has a part of him with them always.

What’s the first horror story you can remember making a big impact on you?

That would have to be Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart”, which my mom first read to me when I was very little. I loved it and made her read it to me again and again. It made me want to be a writer. Some 20 years later, I read Clive Barker’s “Dread” and felt insanely jealous that he’d got there first with the idea!

Name your three favourite horror writers.

Shirley Jackson, Ramsey Campbell and Stephen King.

Is your writing generally firmly in the horror arena or do you do occasional jaunts into other areas of speculative fiction?

I’ve recently fallen back in love with SF, so I’ve been both reading and writing a lot of that lately. I was thrilled to place my story “The Calling of Night’s Ocean” in Interzone last year.

I’ve also done some fun Lovecraft crossovers, including a story called “Tentacular Spectacular” for Steampunk Cthulhu and a high fantasy one for Sword & Mythos. I had a blast writing them and they’re both genres I’d happily return to, with or without tentacles!

I also read crime fiction, but I don’t think I’d enjoy writing it. I would love to attempt an old-school mystery, though – ideally set in space! And I’ve got one pet project that’s been fermenting for decades which is either fantasy or magic realism, although of course I can’t keep the horror out of it.

What’s in your to-be-read pile at the moment?

I tend to have several books on the go at once and I’m buried in 4 novels right now: Creatures of Light and Darkness (Roger Zelazny), Ringworld (Larry Niven), Neuromancer (William Gibson) and Hellstrom’s Hive (Frank Herbert), as well as the current issues of Interzone and Black Static and a couple of horror anthologies. (I tend to dip in and out of story collections and anthologies rather than reading them straight through.) On my teetering TBR pile is a ton of mostly SF, including Armada (Ernest Cline), Mother of Eden (Chris Beckett) and Helliconia Summer (Brian Aldiss).

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories can be pre-ordered here.

July 20, 2015

The Sourdough Posts: Sister, Sister

“Sister, Sister” has its roots in my childhood: one of the books we had to read was an old collection of my mother’s, called Norwegian Folk Tales. I suspect it was an old book when Mum first got it as a kid, it was a thin tome with a forest green cover and silver lettering – it’s long since disappeared, though I found a later edition earlier this year and bought it (still not the same, just saying). In it was all sorts of tales of hulders and trolls, of women whose back side was hollowed out like a tree trunk, and yet others who looked perfectly normal but for their cow tale … but the bit of information that most appealed to me and stuck with me over the years was that trolls were known to steal away human babies and leave their own nasty, mewling offspring in the cradles.

“Sister, Sister” has its roots in my childhood: one of the books we had to read was an old collection of my mother’s, called Norwegian Folk Tales. I suspect it was an old book when Mum first got it as a kid, it was a thin tome with a forest green cover and silver lettering – it’s long since disappeared, though I found a later edition earlier this year and bought it (still not the same, just saying). In it was all sorts of tales of hulders and trolls, of women whose back side was hollowed out like a tree trunk, and yet others who looked perfectly normal but for their cow tale … but the bit of information that most appealed to me and stuck with me over the years was that trolls were known to steal away human babies and leave their own nasty, mewling offspring in the cradles.

Even at a young age I loved the idea of the changeling child – and even more I loved to torment my younger sister that she wasn’t really my true sibling, but a troll’s daughter left in the crib to cause trouble. All this probably says more about me than my sister, but when I began to think about new stories for Sourdough I knew I wanted a troll tale and I knew I wanted to use the changeling child as a motif.

The first image that came to me was that of the interior of the Golden Lily Inn and Brothel; I knew who the inhabitants were, I knew many of them had previously appeared in Sourdough, such as Bitsy, Kitty, Fra Benedict, Rilka, Faideau, Livilla – and my beloved Patience Sykes in her old age (her middle years are covered in Of Sorrow and Such out from Tor.com in October this yea). One of the things that really comes to the fore in this story is how well we do or don’t know our friends, how rumour and gossip colours what we know of their history, and indeed how many of these characters have already become the stuff of legend to some small degree. Theodora, my narrator is new, though, and we see through her eyes how she’s fallen from Princess of Lodellan to an employee at the Golden Lily. That she’s been replaced by her sister as First Lady, that she dreams of escape and being free, and that the being she loves most in the world is her little daughter Magdalene. But Lodellan isn’t safe anymore and when Theodora treads the streets she once ruled she comes to the attention of something she’d really rather have avoided.

Sister, Sister [extract]

The final hymn is being sung off-key and I suspect the choir-master will not be pleased. I smile, imagining his scowl as he tries to locate the culprit amongst those angel-faces. Imagination is all I have at this distance, there’s very little to see from the arse-end of the Cathedral.

Pillars, posts, baptismal fonts, and other members of the faithful all ruin the landscape. My kind are tolerated in church, but only just. This is not the view I used to have; once, I sat in the pews up front, those with little gates on the side to let everyone know how special we were.

Once, I was on show.

I still am, I suppose, but now it’s looks of pity, occasionally of contempt. Always curiosity. I’d have thought that after six months it would have died down, but apparently not. I hold my head high, meeting cold stares with one even frostier until they turn away. But I tolerate this, continue coming back once a week for my daughter’s sake. Just because I’ve lost faith doesn’t mean Magdalene should be denied the possibilities of its comfort; besides she loves the theatre of it as only a child can. When she is older she can decide for herself whether there is something genuine to be had.

The Archbishop lifts the chalice, makes his final flamboyant gestures, bows his head and  bids those within range of his voice to go in peace. This much I know from memory. Those in the front rows rise and I think I see the flash of Stellan’s golden hair and a hook twists in my gut; but I could be mistaken. No sign of the other one though. The flock rises with the rhythm of a wave. One advantage of our lowly seating is its proximity to the door. We, the inhabitants of the inn, are out in the sunlight before the exulted few have managed to move two yards.

bids those within range of his voice to go in peace. This much I know from memory. Those in the front rows rise and I think I see the flash of Stellan’s golden hair and a hook twists in my gut; but I could be mistaken. No sign of the other one though. The flock rises with the rhythm of a wave. One advantage of our lowly seating is its proximity to the door. We, the inhabitants of the inn, are out in the sunlight before the exulted few have managed to move two yards.

Magdalene’s hand creeps up to twine fingers with mine, her grip tight and clammy. In the shade of the portico at the top of the steps sit the Archbishop’s six hounds. Grey and silver in the shadows, insubstantial until someone with ill intent crosses the threshold, then they become suddenly-solid, voracious and vicious. No one wants a resurrected wolf hunting them down. I have explained, over and over, to my little girl that they will do her no harm, but there is a core of fear in her that not even her mother can touch.

From across the square comes the sound of a carriage and four. It is the white ceremonial one I rode in on my wedding day. The sheer curtains are drawn but I think I see pale blonde hair as the occupant peeks out. Polly, who has yet to attend a church service in all her time in this city. My sister makes no pretense of religious zeal.

Behind us the wolf-hounds growl and Magdalene wails, climbing up my skirts like a terrified monkey. She holds me so tightly I can barely breathe. Grammy Sykes pats her back and talks in a low voice to the wolf-hounds. They react to her tone, settle back to sit in the shadows, the exiting crowd giving them a wide berth. I look at them, wondering who among the press of bodies set the beasts off. Grammy pokes me to move along and we head for home.

*

The inn is old, so old that if you cut into the walls you might find age rings like those in the great trees of the forest beyond the city walls. The wood panels have been darkened by years, hearth smoke, sweat, tears and alcohol vapour. If you licked them (as the children sometimes do), you’d taste hops as well as varnish.

The bar itself, where Fra Benedict serves the drinks, is pitted with the marks of drinking vessels slammed down too hard, the irresistible will of dripping liquid, and the musings and graffiti carved by the bored, the drunk and the lonely when the barman is distracted. The glassware gleams, though, as do the metal fixtures and the bottles behind the bar are kept clean (although it’s not as if they stay undisturbed long enough for dust to settle). There are booths with seats covered in balding velvet, and the hiss-hum of the gas lamps (lit low for daytime) is a constant comfort.

Things are quiet at the moment, Sunday afternoon, most of our clients still pretending their piety after Mass this morning. There’s only Faideau in a corner booth, his breeches slung low and his shirt stained with wine. He’s a poet, he says; drinks like one at any rate. He snores loudly. Fra Benedict will go through his pockets soon for the money he owes, then roust him to move on, to spend at least a few hours out in the sunshine.

In one corner is the crèche, where we whores and wenches leave our children (those of us who have them) under the tender, watchful eyes of Grammy Sykes and her half-wolf, half-something-or-other, Fenric. The small space is scattered with books and toys, which miraculously stay within a reasonable radius. Two little boys, and three girls, one of them Magdalene, three years old and still clad in her red Sunday robe. My little girl, the only reminder that I was once loved.

In the kitchen I can hear Bitsy dropping pans. A few seconds later Rilka chases her out, swearing mildly, which is about as angry as anyone can get with Bitsy, who now stands in the middle of the room, unsure what to do next. Fra Benedict makes his particular peculiar noise to catch her attention, jerks his head for her to come and sit at the bar. He is mute, his tongue having been torn out many years ago in some monastery brawl. Bitsy hoists herself onto one of the high stools and sips at the weak ale and blackberry shandy he pours for her.

Bitsy is a little older than me: her face bears the blankness of youth and her long straight hair is a white blonde. She used to be a doll-maker. Not all of them go the same way; she made a special kind of doll, putting tiny pieces of her soul into them. Beautiful dolls, they were (I saw some in a museum, once), but each one left her emptier.

Now she’s touched, little more than a doll herself, with just enough wit to sometimes take drinks to tables, wash dishes, and lie still when a client with no need for a real response climbs aboard and lets her giggle beneath him. Fra Benedict is kind to her; I think they are distant cousins.

Rilka’s dark head pops out of the kitchen. ‘Finished with them peas yet, Theodora?’

I shake my head. ‘Soon, Rilka.’

She disappears with a profanity. Rilka was a nun, in her better days.

Now she’s just like us. Some men pay extra for her to lose her spectacular temper and hurt them. Her special gentlemen callers, she says with a laugh. Tall and muscular, cedar-skinned Rilka doubles as cook.

Kitty thinks Rilka killed someone, tells how she talks in her sleep.

Kitty mends our dresses, sitting in the corner, working on one of those I brought with me, taken apart and made over to fit others. I had no further need of finery. Kitty pulls hard on her final stitch, makes a knot then cuts the thread with her teeth, etching more deeply the tailor’s notch in her left front tooth. Her hair is brassy-bright, a touch of red, a touch of gold; it’s beautiful and distracts clients from the scars on her face: two running parallel across the bridge of her nose before dropping down her left cheek like deep gutters, relics of an unkind husband. Her eyes are blue and sad.

She holds the dress up for me to see: the green and gold brocade is now short enough to show off Livilla’s fine legs, and tight enough around the waist to push her breasts up so they will spill from the top of the bodice. I nod approval just as we hear one of Livilla’s loud sighs floating down from an upstairs room. A few seconds later there is a satisfied, bellowing grunt from her client. She has earned her fee for the day.

Fra Benedict and Grammy Sykes, his common-law wife, don’t make us take all comers. Most of the men are regulars who know Fra and Grammy keep a fair house with clean, cared-for girls. Sometimes there are women, too, anxious for something soft and gentle as a welcome relief from their husbands’ violent prongings. We need only bed one client each day, any after that are up to our discretion. The fee here is high enough and the need for us to work as bar wenches outweighs the pull of the money to be made in excessive bed-sports. One of the advantages of Fra and Grammy’s lax policy is that men are anxious to have what might be refused them, so we always have clientele, banging on the doors, hoping to pay for our favours.

Grammy Sykes was a whore once herself; she remembers what it was like, the constant line of hard, demanding cocks. I think she prides herself on being kinder to us than anyone ever was to her. Livilla whispers that Grammy was a great beauty in her day, although there is scant evidence of it now.

Grammy and Fra will both tell you how many of their girls have gone on to better places, indeed, so many of their old girls are now the wives of rich and influential men that upper-class dinner parties sometimes resemble a whores’ reunion; can’t throw a silken shoe without hitting some woman who used to earn her living horizontally. The comfort of a prosperous future is for the other girls. They don’t tell me this story.

I finish shelling the peas then turn to polishing the silverware Grammy keeps for the private parlour. I hear the front door open behind me, see the sunlight flare in momentarily before the door closes and the cool dimness is restored. I don’t turn around until Fra nods to indicate that the customer is waiting for me.

Prycke was, still is, the Prime Minister. He wanders the capital with minimal guards as if he is still as unimportant now as he was when he was born in the lower slum areas, out near the abattoirs in the furthest, poorest quarters of the city. He’s not overly tall, has a stern sallow face, but his eyes are kind. Clad in dark colours, you might not realise how fine the fabrics of his breeches and frock coat are unless you look carefully. The buckles on his shoes catch the light of the gas-lamps and it seems he has stars on his feet.

‘Have you a moment, mistress?’

I nod, feeling the precarious pile of dark curls on my head sway; one long tendril breaks free and snakes down my neck. He watches it fall. ‘My time costs nowadays, sirrah.’

He is taken aback, reaches into a pocket and draws forth two gold coins. I raise one finely plucked brow but say nothing. I remain silent until he has extracted seven gold coins, then tell him to pay Fra Benedict.

Prycke follows me upstairs. I choose the room with blue velvet curtains hanging around the four-poster bed and a view of the city, an expanse of roofs and, if you look straight down, the Lilyhead fountain and children playing in its greenish waters. I tug at the loose stays of my dress with one hand and at the single clip in my hair with the other; the russet velvet falls to the floor and torrents of hair tumble down to my waist, obscuring the jut of my breasts. I sweep the tresses back so he gets his money’s worth.

He gulps, removes his shoes first (so sensible! So practical! So strategic!), then his coat, and unbuttons his breeches, letting them drop. His legs are pale, hairy, strong. The tip of his cock peeps from under the hem of his shirt, shy, not quite ready. He didn’t expect this encounter, I’m sure, at least not this kind of encounter.

I lie on the bed, splayed like an open flower, and wait for him.

When we are finished, he avoids my eyes. He slips, calls me Majesty. I laugh long and hard at that.

‘Would you come back, Ma – madam? If you could?’

‘Even if I wanted to, I would not, could not. Another sits in my place.’ I fix him with a stare, blue and cold.

‘Your step-sister, madam, she never sets foot in . . .’

‘My sister, Prycke, neither step nor half. Only full-blood can hate so well.’

‘Your husband sent me.’

‘My husband heard me called “whore” and believed it. My husband heard his daughter called “bastard” and believed that, too.’ I hiss the words at him, spittle gathering at the corners of my mouth and curse that I still feel anything. ‘Five years together and I gave him no cause to doubt me, but the moment my sister swears to him that I had taken lovers he believed her.’

‘Madam, I was not in the city when it happened. I would have counselled him otherwise,’ he stammers. He feels badly for me. But he did nothing for me.

‘For all the good it would have done. My husband brands me whore and takes my sister to his bed. So, I embrace my new title, Prycke. I am whore to whoever pays for me.’ I sit up, step into my gown, lacing it tightly for I have earned my keep for today and tomorrow.

He dresses quickly, a handy skill. ‘Madam, your sister has a strangeness about her. She is peculiar . . . she does not attend . . .’

I raise my hand. ‘No more, Prycke. No more.’ He reaches for the door handle. ‘Prycke?’

He turns back, face hopeful.

‘Tell the Archbishop I will see him on Tuesday, at our usual time.

***

July 19, 2015

The Voice of Waters of Versailles: Kelly Robson

The lovely Kelly Robson takes some time out to talk about wine, water, and teetering on the edge of darkness.

1. So, what do new readers need to know about Kelly Robson?

When driving, I always strive to give my passengers the smoothest possible ride. No jerky stops and starts for me and mine!

Same goes for readers. My ultimate goal is to be the kind of writer whose work you can fall into effortlessly.

2. What was the inspiration behind Waters of Versailles (edited by the inimitable Ellen Datlow)?

Looking back, Waters of Versailles formed at a confluence of four wide streams: wine, water, death, and children. Several years back, I had a glorious freelance gig writing the monthly wine and spirits column for Chatelaine, Canada’s largest women’s magazine. At the same time, I was working for environmental scientists, editing and producing a 500-page book about river restoration projects. During that same year, my dad died, and a few months later I took care of my two year-old niece for 36 hours. She’s a great kid, but childcare was the most exhausting thing I’ve ever done.

But that’s just hindsight. The story originally sprouted from the image of the champagne fountain — a giant Baroque extravagance, wasteful and glorious.

3. Tell us about the cover art from the very talented Kathleen Jennings!

Kathleen Jennings is such an amazing artist — I am so lucky to have a cover by her. It’s just glorious — such a striking design!

Not only did Kathleen get all the major characters into it, she also included the monkey and the parrot, which are two of my favourite parts of the story. The cover also includes an Easter egg. If you look closely at the bottom right and left, you’ll see tiny water taps and spouts on the framing pipe design. So clever!

Kathleen has made the art available at her Redbubble store. I’ve bought several items, and I know Ellen Kushner and Tansy Rayner Roberts have both bought a few pieces too — T-shirts and scarves. The art looks even better printed large. I have a big Redbubble print on my bedroom wall, and I hope to be able to save up enough to buy Kathleen’s original when I see her at the World Fantasy Convention in November.

4. When did you first start writing and what made you want to do so?

Books have always been the most important thing in my life. I started young, writing my first book in grade 5 and adapting C.S. Lewis’ The Last Battle for a one-act play in grade 6. With a start like that it should have been full steam ahead, but though I wrote a few things over the years I didn’t get really serious about writing until Nanowrimo 2005. There comes a time in everyone’s life where you realize time is running out and you really should get down to it or it won’t happen. I’ve put hundreds of thousands of words in the trunk over the past ten years, and each one was necessary in learning how to tell a good story.

5. What’s your favourite short story ever?

If I had to choose just one, it has to be Connie Willis’ Science Fiction screwball comedy romance Spice Pogrom, which heavily influenced Waters of Versailles. It’s a hilarious, touching story with a cast of thousands. I love the way the plot starts snowballing downhill, taking everything with it. Genius!

If I had to choose just one, it has to be Connie Willis’ Science Fiction screwball comedy romance Spice Pogrom, which heavily influenced Waters of Versailles. It’s a hilarious, touching story with a cast of thousands. I love the way the plot starts snowballing downhill, taking everything with it. Genius!

6. In general, who and/or what are your writing influences?

My living gods are Connie Willis, Walter Jon Williams, and Michael Bishop. All are brilliant at both short and long form. Outside of the genre, it’s got to be Alan Bennett and Hilary Mantel.

Connie’s new novel is coming out this January. I’ve just found out that Walter is returning to his Praxis space opera universe with a new trilogy, and I’m just thrilled. Michael Bishop had a brilliant novelette in Asimov’s this February, Rattlesnakes and Men, and I hope to see more from him soon. And Alan Bennett has just released a bunch of short stories, old and new.

My dead gods are James Tiptree, Jr., Jane Austen, the Brontes (especially Anne), Thomas Hardy, Elizabeth Gaskell, and George Eliot.

7. Talk us through your amazing science fiction horror short “The Three Resurrections of Jessica Churchill”?

This is where Tiptree comes into it. “Three Resurrections” draws heavily on the Tiptree novella The Only Neat Thing to Do, which starts off as an aw-shucks space adventure and then has you sobbing uncontrollably through the last third.

“Three Resurrections” is dark. Very dark. It has to be, because it’s my attempt to convey the vast gaping horror I have stood on the edge of since the age of sixteen, when one of my high school classmates disappeared. It was foul play — she was certainly murdered — but her body has never been found. She is listed among the Highway of Tears murders, which are still ongoing along Highway 16 in British Columbia and Alberta, contributing to the epidemic of murdered and missing Indigenous women in Canada. This is a ongoing situation that the Canadian government refuses to deal with.

8. Who is your favourite villain in fiction?

I like effective villains. They’re strangely hard to come by! My favourite villain is Steerpike from Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast. He really is the worst. I will never forgive him for what he did to Fuchsia. And his rise from kitchen boy to Master of Ritual is a delicious version of the stereotypical fantasy hero’s rise from obscurity to power.

9. Who is your favourite heroine/hero in fiction?

I love unlovable heroines — the Emma Woodhouses and the Gwendolyn Harleths of the literary world. They’re vain, bossy, and sometimes quite nasty. They think far too well of themselves, but I can’t fault them for it. Healthy self-regard is no crime. And in any case, they are their own worst enemies. In my opinion, Gwendolyn Harleth doesn’t deserve the ending that George Eliot gives her in Daniel Deronda. I would very much like to rehabilitate her.

10. What is next for Kelly Robson?

My Science Fiction short story “Two Year Man” is out right now in the August 2015 issue of Asimov’s. And in November I have a novelette in the anthology Licence Expired: The Unauthorized James Bond, coming from Toronto’s wonderful ChiZine Publications and edited by Madeline Ashby and David Nickle. The Ian Fleming books have just entered public domain in Canada, so it’s open season on Fleming’s Bond. My story “The Gladiator Lie” is an alternate ending to From Russia with Love. It was so fun and gratifying to work on. I’m still cackling over it. And I’m not alone — every contributor has said that writing a Bond story was the most fun writing they’ve ever done. If the authors had that much fun, you know readers will have a blast.

July 14, 2015

Get Your Fight Scenes Here: Top Five Tips for Tip Top Fights

One of the things I find most challenging in writing is fight scenes – not a huge number occur in my work, but just enough to cause me annoyance and frustration. Lucky for me I’ve got Alan Baxter, International Master of Kung Fu and, coincidentally, award-winning author of dark fantasy, horror and sci-fi on speed dial. I figured all writers could benefit from a few tips from an expert in the field of punching people in the face (but not in a psychopathic manner), so I asked him to write a post about it. Take it away, Al!

One of the things I find most challenging in writing is fight scenes – not a huge number occur in my work, but just enough to cause me annoyance and frustration. Lucky for me I’ve got Alan Baxter, International Master of Kung Fu and, coincidentally, award-winning author of dark fantasy, horror and sci-fi on speed dial. I figured all writers could benefit from a few tips from an expert in the field of punching people in the face (but not in a psychopathic manner), so I asked him to write a post about it. Take it away, Al!

Top Five Tips for Tip Top Fights

So you want to write a fight scene. Even if you don’t now, you probably will at some point. After all, stories are powered by conflict and that can mean unrequited love, an obstructionist boss, a broken down car or a million other things. But it often means actual, genuine, drag-out fisticuffs. People love a bit of ultraviolence in their fiction and it’s usually the safest place to find it.

The trouble is, most writers haven’t had many, if any, fights. And that’s a good thing. Fighting is not a great experience for most, unless you train in the martial arts and enjoy combat sports. Or you’re a psycho who beats people in the street, but if that’s you, you should be in jail. Go and hand yourself in, you animal.

And that’s where I come in. I’m not a psycho (go ahead, try to prove it!), but I’m a writer and a martial artist. I’ve trained for over 30 years and fought in a variety of environments, so I can draw on my knowledge to write good fight scenes. In fact, I started to get a bit of a reputation for it and was asked to run some workshops on the subject. Following that, I even wrote a short ebook on the subject called Write The Fight Right. It’s a very short book, but it’s designed as a reference guide for writers to make their fight scenes as authentic and exciting as possible.

Recently, Angela asked me to write her a guest post on the subject of fight scenes, so I said “How about a Top Five Things To Consider When Writing Fights?” She said “Sounds perfect!”

So, here are my five top tips to make a fight scene in your story as realistic and visceral as possible:

Your book is not a movie. Most people, without any other point of reference, simply transcribe a movie-style fight scene onto the page when writing. Movie fights are (most of the time) incredibly unrealistic and designed for that medium. In a movie, we have to watch from the outside, we need to see what’s going on, so combatants take turns and use big, clear attacks and blocks. Real fighting is nothing like that. With writing, we can get inside the action and inside the characters’ heads and make everything more exciting and gritty and downright brutal.

Less is more! A fight scene should be the fastest, most visceral scene in a story,

but so often they’re slow and cumbersome when authors try to describe everything that’s going on, all the complexities of attacks and blocks and so on. It’s boring! Short, sharp and pared back is the way to go.

but so often they’re slow and cumbersome when authors try to describe everything that’s going on, all the complexities of attacks and blocks and so on. It’s boring! Short, sharp and pared back is the way to go.The five senses. Movies are a visual medium with added sound. When we write, we can use touch, taste and smell to great effect as well. What does it feel like to get punched in the face? Can you smell the sweat and fear? Can you taste the blood? (The answers to these questions are: pretty horrible, yes, and yes.) Using these things along with sight and sound adds enormous impact to your fight scenes.

Adrenaline and emotion. Anyone in a fight who isn’t scared is a psychopath. Even the best fighters are afraid and they have to deal with massive dumps of adrenaline, they have anger, shock, pain to deal with. The better a fighter you are, the more you’ve trained to deal with these things. The less experience you have, the more these things will fuck you up.

The knockout myth. You know in movies when people are knocked out for long enough for other characters to do all kinds of stuff, then they wake up and carry on like normal? Such bullshit. When a person is knocked out, that’s brain damage. If they’re only out for a few seconds, they’ll come around groggy and almost certainly concussed, but hopefully not too badly off. If a person is out for several minutes, they have suffered serious brain injury and absolutely will not be able to function normally for a long time after they wake up. If ever! This fact isn’t much use in stories when you need someone to be out of action for a while, but if you’re looking for realism, the KO is not it.

Hopefully these points will give you some food for thought in your next fight scene. Of course, (shameless self-promotion ahead!) all these things and more are dealt with in much greater detail in my ebook, Write The Fight Right. Now go forth and write great fights!

Hopefully these points will give you some food for thought in your next fight scene. Of course, (shameless self-promotion ahead!) all these things and more are dealt with in much greater detail in my ebook, Write The Fight Right. Now go forth and write great fights!

Alan Baxter is an award-winning author of dark fantasy, horror and sci-fi and an International Master of Kung Fu. Read extracts from his novels, a novella and short stories at his website – http://www.warriorscribe.com – and find him on Twitter @AlanBaxter and Facebook.

July 13, 2015

Once upon a time …

By Michael Hutter

… Simon Marshall-Jones of Spectral Press sent me this gorgeous piece of art and said, ‘Don’t suppose you fancy writing a novella for me with this as the cover? It’s called “The Witch’s Scale”.’ Faster than the speed of light (figuratively not literally, pedants), I said ‘Yea, verily yea.’ Equally quickly I wrote a novella … two and a half years before the deadline.

As a working writer, I can’t afford to have stories sitting around that long, so I said to a very understanding Simon, ‘I’ll write you another.’ That first novella, renamed “Ripper”, went off to live with Stephen Jones in his Horrorology anthology, which is coming out from Jo Fletcher Books in October this year.

So, I wrote another novella (in between writing a novel, three short story collections, and about fifteen short stories). It was set in the Sourdough world … and it was one and a half years ahead of the deadline. Again, Simon was understanding when I withdrew it and renamed it and sent if elsewhere. That novella, now known as “Of Sorrow and Such”, will be published by Tor.com, also in October of this year, as part of their new novella series.

But never fear, I always had another idea for “The Witch’s Scale”, and I’ve spent the last several months making notes and plotting things out; last week it all came together and the story demanded to be written. So, I’m taking time off between the other novels I’m supposed to be writing, and getting a Real and True “The Witch’s Scale” down on paper … well, screen.

What I do like is that there are now three of my novellas with lines in them about the witch’s scale and where women appear on it. I’ve always liked putting little links between my books and stories, whether it’s simply reusing a street name or a repeated motif as a kind of Easter egg, and I really love the fact that this cover has inspired and informed several works.

Having started “The Witch’s Scale”, I’m happy to say it’s coming in nicely. It’s set in the Sourdough world, it’s in a town unofficially ruled by the Briars, a family of witches. The matriarch Gisela has brought up her great-granddaughters, Audra and viewpoint character Ani, to take over when she dies: Audra, the most powerful witch of the new generation, as the new head of the family; and Ani, who alone of the Briars has no eldritch skills at all, as the administrator. But when Gisela does pass away, Ani unexpectedly comes into a power not seen in the Briars for hundreds of years: the ability to speak to the dead.

Extract from The Witch’s Scale

‘How are you, Deirdre?’ I speak softly so as not to startle her, but she gives no sign at all of having heard.

The girl still faces the wall. All I can see is the back of her head, the dirty blonde, dishevelled hair she’s neither washed nor brushed since she gave birth to the stillborn boy seven days ago. She’s not bathed though I know her mother has tried to talk her into it. The room smells of old blood and dried excrement, stale body odour and some fresh vomit. She’s not keeping down the small amount of food Beres gets her to eat; I suspect she eats while watched just to get the woman to go away. Then Deirdre puts her fingers down her throat and brings it up again into the chamber pot. She’s not too fussy how much gets in and how much misses the receptacle; I notice that too.

The baby’s not yet been buried; it’s still summer so he’s in one of the cellars dug into the bank of the river where some folks store their fruit and vegetables to keep them fresh and cool. Beres has swaddled him and put him there, between the bottled preserves and the wheels of cheese, just until her daughter can be persuaded to name him. We do not consign our dead to the earth without a name; without their names they are not whole, they are lost, they wander.

Gingerly, I sit on the bed and put a hand on her shoulder, which has grown thin, the bones more pronounced as if trying to escape her skin. She shivers, the movement going through her like a ripple through water. It’s the first sign of life I’ve seen in her since the baby came too early.

‘Deirdre. Deirdre, you need to talk to me. Please.’ There’s a long frozen moment that’s broken only when she turns, a slow rolling from her side to her back, and I reminded of a dead fish sinking into the depths, rolling, belly up, then down, then up, then down, a terrible spiral that can end only one way. ‘Deirdre, I know it hurts.’

‘How can you know anything?’

***

Happy dance!

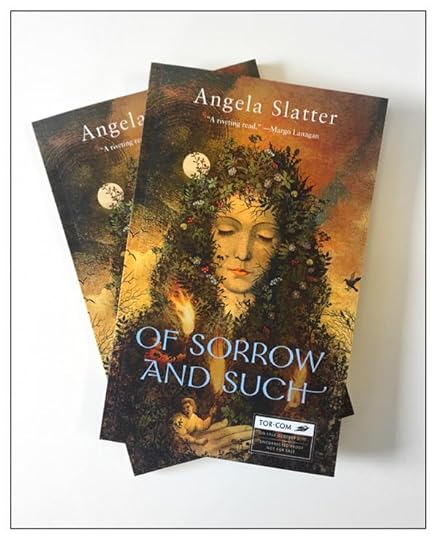

This morning the lovely Irene Gallo posted this on Twitter – galleys for my Tor.com novella Of Sorrow and Such!

This morning the lovely Irene Gallo posted this on Twitter – galleys for my Tor.com novella Of Sorrow and Such!

The cover art is by the astonishing Anna and Elena Balbusso, who did the cover for Nicola Griffith’s Hild, among other things.

It’s a real book!!