Peter M. Ball's Blog, page 8

July 6, 2022

Indie Publishing and Business To Business Thinking

A general frustration I’m having with self-publishing/indy publishing circles right now

Indies are, by and large, a business-to-business endeavour that primarily exist to provide ebooks to distributors and retailers who then sell them to the customer.

Many of those distributors and retailers give an extraordinary level of control to the authors around pricing and promotion, convincing them they’re actually business-to-consumer. It’s become a foundational assumption in the rhetoric around indie publishing, even if it’s not true.

So many people’s frustrations stem from this misunderstanding once they’re past the initial learning curve. The idea that you adjust some part of your product to make it appealing *to the business that actually sells it* is frequently met with all kids of denial, particularly when the suggestion involves increasing your prices beyond the just-barely-making-a-profit baseline.

Indie authors have been trained to focus on the customer above all else, and have stuck to the strategy that undercutting traditional publishing’s prices is the only viable path to success. Frequently, the argument seems to be, “readers won’t pay that” or “I don’t want to pay that for a book”, despite the fact that traditional publishing has made it clear readers will pay decent money for a good book they really want to read.

(My rule a thumb, back when I first indie published in 2005, was “figure out how much you think a book is worth, then add a buck because you’re incredibly bad at gauging the value of your work”. These days, I’d probably add two).

At the same time everyone’s ignoring the business-to-business aspect of their business, there’s a low-level hostility to the work required to set up direct sales channels where you’re *actually* a business-to-consumer business, and can really capitalise on the increased margins on every sale.

And many of those who do take the plunge of selling direct immediately look for ways to hand the logistics back to the businesses they’re already dealing with, because they don’t actually want to have a direct relationship with their consumers.

I like to think this is frustrating because these conversations are happening ore often and we’re heading towards a pivot point, a place where folks are developing a more mature understanding of the business strategies and how to engage with the players involved.

But there are days when I definitely have to pull myself away from the keyboard, lets I find myself trapped in one of those “someone is wrong on the internet” conversations that keeps me awake until 3:00 AM mounting an argument I can’t win…

(originally posted on the book of face, 23 June, 2022)

July 5, 2022

Knock Knock: an interactive sci fi serial (Part 2)

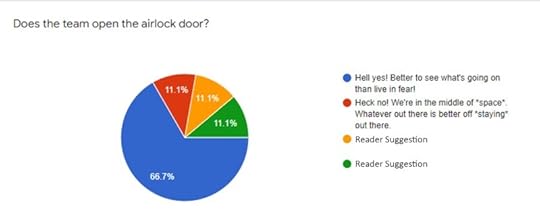

Part two of my sci-fi serial where readers get to choose what happens next. When we encountered the three-person team manning Remote Research Station Denki back in part 1, they were surprised by a mysterious knock on the door…and no details appearing on any scans. Readers go to vote on how they responded, and I’ve included the results below!

Two readers had very specific suggestions (one bloodthirsty, one polite), but overwhelmingly, the response was opening the door and letting the visitor in.

With that, it’s time to kick off part two.

KNOCK KNOCK (A Serial With Reader Interaction)Part 2: Boarding ProceduresTse raised the first tentative hand, stealing a glance at the airlock door as she did so. “Not sure how long that’ll hold,” she said. “Whatever’s out there might not be hostile, but we know a breach will mess us up.”

Finn squared their jaw, masking the gut-rending surge of fear beneath a veneer of command stoicism. “Luce?”

“No way in hell,” Lucy said.

Finn expelled a long breath, fingers clawing at the armrest of their chair. No majority meant the decision fell to them, and the guilty voice inside their skull smugly reminded them they were in charge—it always should have been their call. Finn screwed their eyes shut, blocking out Lucy’s pleading look and Tse’s wary anticipation. Denki’s hull could withstand meteor impacts at velocities up to 55 meters per second, and the design had survived worse in testing. Tse’s fears had merit, but the shell was sturdy – if their visitor could break in, they had bigger worries than decompression.

“I vote we open,” Finn said. “Cautiously. Luce, get ready to pressurize the airlock and break the seal. Tse, break out the boarding kit, just in case they’re hostile.”

Finn’s orders elicited curt, efficient nods, but nobody moved to comply. They were all braced for the next knock, waiting for the echoing boom against the hull, and its absence felt more terrifying than its presence might have been.

“Maybe they heard us,” Tse joked.

They exchanged a long, nervous look in the aftermath, then silently turned and went to work. It was easier to ignore the creeping whisper that Tse’s joke might have been genuine consideration when they were in motion.

The navy didn’t equip remote research stations for major trouble. Their boarding kit comprised three telescoping pikes and gel-packed shotguns designed to take the fight out of boarders without puncturing the hull. Theoretically, enough to hold off a raiding party, on the off chance a pirate crew found themselves this far out and desperate. Ill-suited to a more focused raid, where protocol demanded the crew surrender or blow the station, depending on the odds of surviving the assault.

Tse slung a shotgun over one shoulder, underhanded a pike to Finn. They caught it one-handed and took a position by the airlock, telescoping the weapon to its full two-meter length, sharp-blade pointed toward the door. Standard precaution against boarding; in theory, it didn’t take many pikes to hold a narrow bulkhead or airlock, but in practice Finn felt like they were trying to stop a hurricane with a toothpick.

BOOM… BOOM! The station shook, and Finn dropped into a wide stance, giving themselves stability for the fight ahead. Tse fell into place behind, covering the doorway with the gun. Lucy’s fingers danced across the console. “Still nothing on the sensors, but we’re ready to open on your mark, Cap.”

“Do it,” Finn said. “Let’s meet out visitor face-to-face.”

The hiss of pressurization freed Lucy up to join Finn at the door. She extended a second pike and fell into the same wide stance, training taking over despite the nerves and uncertainty. Finn sucked down a deep breath and steadied their breathing, but couldn’t hide the wince as the magnetic seals released. The airlock slid open, two halves parting for the central seam. Air hissed out as the two chambers matched pressure, and the down-lights in the airlock cast a bright sheen against the black, chitinous shoulders of their intruder.

Any thought that it might be human evaporated in that instant. The intruder was large—easily two feet taller than Tse, the tallest of their team—and wore an encounter suit unlike anything Finn had encountered in fifteen years as a spacer. The black lacquered armor gleamed and shimmered in the light, and it lacked the sleek, body-suit design humanity had spent two centuries refining, moving away from the overstuffed marshmallow suits used during their first forays into space. The visitor hadn’t moved since the seal broke, one arm raised to knock once more, even without the door.

Instinct told Finn to lash out, test the pike blade against the thick armor plating. Get some confirmation self-defense was possible, that they weren’t engaging in a futile effort. Training kept him from making the wrong move. “I’m Captain Dagda Finn of the SolGov research station Denki. We mean you no harm, but we’ll defend ourselves if you take hostile action. Please identify yourself and lay down your weapons.”

The intruder lowered a bulky arm, but offered no verbal response. The ponderous weight of its helmet adjusted, fixing upon the pikes and the nervous humans behind them. Finn swallowed their fear and held their ground, prayed neither Tse nor Lucy would break. “We mean you no harm,” Finn repeated, keeping their voice steady and even. “We ask you to identify yourself, or leave our station in peace.”

The intruder inched forward with ponderous inevitability, its vast bulk floating atop the floor rather than taking a step. Finn tensed, lizard-brain flooding their system with adrenaline as it screamed warning that anything that flowed with no apparent means of locomotion was unnatural to a degree worthy of terror. The rational part of them seized upon the far more terrifying revelation: anything that could manipulate gravity and levitate like that, particularly on the personal scale, operated at a level of technology far more advanced than humanity’s efforts.

Adrenaline coursed through Finn’s body, bringing with it the aluminum taste of fear. Lucy’s hand terminal chirped, and she risked a glance at the details. “No life signs in the suit, or and they’re not broadcasting information. Internal sensors can’t get a lock on the chemical composition of their encounter suit—”

“DESIST.”

The word reverberated through the station, delivered in a resonant baritone that filled the room like a physical force. Lucy swallowed and adjusted her grip on the pike, steeling herself against the order. Finn envied her resolve, felt nothing more than an urge to turn and run.

As if there was anywhere to go, beyond the cramped quarters and living area the researchers occupied during downtime.

Finn swallowed their fear, focused on the job. “Desist what? The scan?”

“DESIST.”

Tse rose to her full height, the shotgun tucked against her shoulder. “Three words make a sentence, asshole. Subject, verb, object. If you don’t give us—”

“DESIST!”

The word rolled out like a battering ram, knocking Tse to the floor. The shotgun skittered beneath the console, and Tse’s head smacked the floor hard enough to rattle teeth. Lucy tensed up, ready to lunge, and the intruder’s blunt head twisted to fix her with a bug-like eye. Tse moaned softly, stunned and unable to rise.

“Permission to engage, Cap?” Lucy hissed the question between clenched teeth, the words threaded with anger.

“Negative,” Finn said. “See to Tse.”

“Sir?”

Finn stared at the black glass orb of the intruder’s eye and held their pike at arms length. One thumb to the trigger and the weapon contracted to a neat baton, easily stowed at the belt. “My gut tells me we aren’t going to crack that armor with pig-stickers and riot rounds, and anything that can knock Tse over with a shout can do worse to the station itself. Tend to our injured while I negotiate.”

For a moment, Finn worried Lucy wouldn’t obey. The small woman’s fingers clenched tight on the pike, the blade point dancing like a hummingbird as her own flight or fight instincts waged a war inside her. She risked a glance at Tse’s crumbled form, and the shotgun half-hidden beneath the console, and reached a decision. The pike telescoped into its compact form and Lucy nodded her acknowledgment of the order.

Finn returned their full attention to the intruder and raised both hands. “Weapons away. Scans halted. We’ve complied with your request to desist. You obviously have a command of our language, so I’d ask again: identify yourself. We’re a science team on a research mission, and—”

“DESIST.”

“Desist what?”

The intruder floated a few inches closer, came to a halt two inches short of Finn’s position. The alien had didn’t look down, and up close Finn could make out the dents and chips in the armor. Damage from fast-moving micro-debris, the result of long-term exposure to the fragments hurtling through the void at high velocity. Whoever their intruder was, it had endured one hell of a beating and come through no worse for wear. Finn doubted any weapon they had aboard was going to a damn thing against armor that strong. Hell, they doubted blowing the station was going to put a dent in an opponent who wore an encounter suit with armor plating most station engineers would envy.

For a few empty seconds, Finn allowed themselves to sink into the importance of the moment: odds were, their intruder wasn’t entirely human; odds were, they’d made first contact between humanity and whatever species was locked away inside that suit. Odds were, they were making history, assuming they didn’t fuck it up and get Denki station torn apart by pissing this damn thing off.

Finn sucked down a long breath to steady their nerves. “Luce, how’s Tse doing?”

“Beat up, but still breathing,” Tse answered, her voice weaker than Finn would have liked.

“Probable concussion,” Lucy added. “Hit her head pretty good, cap.”

“Can you get her to med bay?”

“Negative.” Tse clambered to her feet, taking each movement slow. She limped over to stand beside Finn, arching her neck to stare up at the insect-faced helmet. “I ain’t turning my back on our friend here, not until we got more intel to work with.”

Finn caught Tse’s eye, acknowledged the tall woman’s resolve with a nod. “Alright. Let’s try this another way—no scans, no weapons, just some good old-fashioned research work. Tse, you give us some space, ‘cause this is going to get stupid. Luce, can you hand me a hand-terminal? We’ll try another scan and see if that’s enough to provoke another’s defensive response.”

The clatter of movement behind them alerted Finn that Lucy had other ideas. They half-turned, caught sight of her dropping into a defensive crouch by the main console, Tse’s discarded shotgun trained on the intruder. Her finger rested against the trigger, ready to open fire.

“I’m afraid I can’t comply, cap.”

Finn swore. That was the problem with fight-or-flight in space: too few damn places to run to…

You can vote for what happens next using the form below. The vote will stay open until Midnight, July 13Loading…

July 4, 2022

Action, Reaction, Jackie Chan, & Gunpowder Milkshake

I often start workshops on story structure with the warning, “after this, you’ll never be able to go to the movies with non-writers again.” Lots of folks think I’m joking, but it’s essentially true: the three-act structure is the source code for an awful lot of TV and movies, and understanding its core beats means you can map out the bulk of a plot from a handful of details.

For me, this resulted in a different kind of enjoyment, more focused on teasing out the how-and-why of creative choices and where things go wrong, but there are plenty of folks who don’t enjoy that. Like, for example, my beloved spouse, who was so irritated by my response to the first three episodes of Star Trek: Next Gen that we’ve basically agreed to watch nothing Trek-related together for the sake of our marriage. They love the TV show unconditionally, and I…um…let’s say “sit there marveling at just how far TV storytelling has come in the decades since.”

So, consider this a warning: the rest of this post is very much me meditating on a particular thing films and TV shows do, and once you know it, it’s impossible to unknow it. It’ll change the way you watch films and TV, affect some of your favourite action flicks, and potentially irritate people who watch things with you,

Still with me? Cool, then let’s talk about choreographing action.

Back in June, we watched Gunpowder Milkshake for the first time. My beloved had been eager to see it at the movies, and we missed it because of the pandemic, so it became a birthday treat for them and, frankly, we both loved it. The colour schemes; the glorious B-Movie violence; the slow parade of every bad-ass female actor you’ve ever wanted to do more action movies; hyper-violent fairy princesses with guns; Carla Gugino with a battle axe! I’ve seen plenty of reviews which are down on the film, but it’s occupying a very specific niche for a very specific audience, and my beloved and I are of that audience.

Except, once again, the creator’s curse reared its ugly head in the heart of all those fight scenes, because I kept getting distracted by the creative choices made by the stunt team. For a film that was hailed as a female John Wick, it misses the one fundamental thing that made John Wick’s action so compelling.

In John Wick, the stunt crew kept action and reaction in the same frame, a technique that’s used in of Hong Kong cinema and one reason their action sequences are so interesting (also the reason Hong Kong action stars tend to lose something when they debut in US produced films with US-trained stunt teams). John Wick is famously a film pulled together by a stunt crew, focusing on the stuff they’re often not allowed to do on screen.

In Gunpowder Milkshake, the choice is made to split action and reaction in the more traditional American approach to stunts; they’re good, but stylistically different, and for the bulk of the film, whenever Karen Gillen’s Sam throws a punch, they’ll cut to another camera angel to showcase the reaction to the blow. I’ve linked a video to Every Frame A Paintings video essay on Jackie Chan films, which touches upon the issue.

The video essay is a fascinating piece that explains so much of why Chan films work, but unlike the bulk of the things I first learned from the Every Frame A Painting series, I’d already picked up the use of this trick via a deep dive into Pro Wrestling storytelling. Long-time producer for the WWF, JJ Dillon, once did an interview about the things he disliked about the current product, and the thing he mentioned was the decision to cut away at the moment of impact.

If you’d like to see what he’s talking about, consider this clip of John Cena’s debut match in the WWE. The action starts about two minutes in.

The entire sequence is about six minutes of showtime, of which two are wrestling, and about 80% of the moves hit in that two minutes see a quick cut to another camera angle. This is one of my favourite WWE matches ever, because it does an awful lot in those two minutes, but once you see that particular editing trick, it sticks with you.

In fact, it uses almost as many cuts as this twenty-minute match from the wrestling company the first really captured my heart, Ring of Honor, which created a more compelling and believable match with a lower budget through the simple expedient of setting up the hard camera and pointing it at the ring.

Because the camera switches aren’t selling the seriousness of each move, the wrestlers have to convey how hard they’re hit, how much it hurts, and how they’re reacting with their own bodies and facial expression. There are camera switches deployed, but it’s done judiciously and to add detail, not as a default flourish.

Of course, there’s a flip side to this: because the camera switches aren’t doing some of the work, the wrestlers who aren’t as good tend to struggle, and the wrestlers have hit a little harder (in wrestling parlance, working stiff or snug) because you can’t rely on the camera covering your mistakes. In an industry that’s already taking a huge toll on the performers’ bodies, it’s a little more wear and tear, and it’s not forgiving to newcomers.

But wrestling and film action rely upon chains of logic—the slow accumulation of action and reaction that escalates and leads to decisive moments that change the direction of the story, and ultimately lead to a climactic moment. And while there are ways to bridge that gap (see my prior writing about writing lessons from wrestling), you have to a) nail it, and b) your delivery using those bridges will feel a little hollow when lined up against someone who both nails it and strings the chain of action/reaction together in a more believable way.

The intriguing thing about this particular technique is just how much it changes your viewing experience and understanding of where thigs go wrong. While it’s immediately obvious in action films, I watched the much-derided Max Payne film after learning about it for the first time, and it’s astonishing how much momentum that film loses by splitting action/reaction shots during its big mid-point reveal.

On the plus side, I actually enjoy Max Payne because of that, but such is the creator’s curse. Once you learn how things are done, you’re constantly looking for ways they’re used…and how you (unhampered by budgets and production constraints) could improve things by doing it a different way and getting a stronger effect.

This post appears courtesy of the fine folks who back my Eclectic Projects Patreon, who chip in a few bucks every month to give me time to write about interesting things. If you feel like supporting the creation of new blog posts — and getting to read content a few weeks ahead of everyone else — then please head to my Patreon Page.

If you liked this post and want to show your appreciation with a one-off donation, you can also throw a coin to your blogger via payal.

All support is appreciated, but not expected. Thank you all for reading!

July 3, 2022

Bullet Journals Revisited, And A Defense Of Rapid Logging

A few weeks ago, I read Ryder Carroll’s book The Bullet Journal Method.

I’ve been using bullet journals for years at this point. Not the pretty art-pieces that you’ll find on the internet, full of scrolling calligraphy and Washi tape, but a series of beat-up journals that are filled with messy handwriting and scribbled notes. Notebooks with no interest in being beautiful objects, but plenty of practical use as a tool. I picked it up around 2012, after being impressed by the way my friend Kate Cuthbert organised her work at Harlequin Australia.

Ten years of relatively consistent bullet journaling is a long time. Over the years, I’ve gotten large chunks of my family into the habit — there’s often a family Leuchtturm shop around the end of the year. I’ve experimented with different approaches, from one dedicated bullet journal for everything to bullet journal by project to bullet journal by context (writing/work/life). I’ve researched and experimented with layouts and approaches, and found stuff that really worked for me (elements of Tobias Buckell’s hacks and showrunner John Rodgers hacks have both been useful).

All of which is really a prelude to saying I wasn’t expecting much from Ryder Carroll’s book. I picked it up because the Bullet Journal method has been a lifeline for me in recent years, and I wanted to throw some cash his way for sharing it so freely back in the early days, but I worked on the assumption I knew what I was doing.

Turns out, not so much.

Going back to basics on bullet journaling after a decade of using the system has been an interesting experience, because there’s a certain amount of drift. You cleave to the practices that are easy and useful, and let other parts fall by the wayside.

Going back to basics—with a more detailed explanation of why they’re in place—proved to be a transformative experience. There are three big tips that have wildly changed my relationship with my bullet journal notebook, but the biggest has been recommitting to my daily log of activities and making notes.

The log, in my experience, is one of the first things to go as people get familiar with the Bullet Journal system. It feels less transformative than indexing and threading, which change your relationship with the contents and thought processes. The value of rapid logging your day is easily overlooked—certainly, for the last few years, I’ve been more likely to implement a daily plan than a daily log.

The Bullet Journal Method convinced me to give logging another try, and it’s value was proven in the weirdest of places—giving our cat medication.

Some backstory: we’d been giving The Admiral pills because the poor kitten has a UTI and some teeth issues, and for the majority of that time my spouse, Sarah, has been our designated pill delivery person. Not that I wouldn’t try — I’d give it a go every morning — but my first few attempts were unpleasant for me and the cat, and Sarah would step in and take over in order to avoid distressing The Admiral further.

Fortunately, Sarah had some insight into what I was doing wrong, and would give me a tip after every attempt. Unfortunately, since the pills happen right before I started work, those tips would ordinarily get lost in the sudden transition from “home Peter” to “work Peter”, with slow (or no) improvement.

The cat’s illness coincided with the recommitment to logging, and part of that meant jotting down every event—work tasks, books started, giving the cat pills — and one or two notes about the experience.

So instead of letting things fall out of my head, every bit of advice Sarah gave me got logged and reviewed. I made my own notes, critiquing each attempt, walking through each step until I figured the point of divergence between concept and practice. I’d create notes to supplement that advice with my own research, hitting up youtube and web pages.

And it only took a few days for a task that I would have flailed at for a week, giving into the option of learned helplessness, to become something I could wrap my head around. Admittedly, right at the end of our three days of giving tablets, but there’s now a record of thinking through and correcting all my mistakes to review the next time I have to do it.

The same philosophy’s started to spread through day job tasks, and publishing tasks. Projects that had stalled for months started to pick up speed, both because I was thinking about them with more clarity, and because taking notes gradually led to building system.

Logging’s become a habit worth keeping over the last two weeks, and one that I’ve stuck to far more consistently than other journaling habits.

That said, it comes with challenges: I’m used to a standard bullet journal lasting me between three months and a year, depending on what I’m doing (faster while researching a PhD, slower when working for places that have their own project management systems). Logging and note-taking on this level is chewing through pages far more quickly than I’m used too, and it’s conceivable I’ll go through a notebook a month if I stick with the rate of pages-used-per-day that I’ve run with over the last two weeks.

On the plus side, I’ve got a *lot* of blank notebooks, but I can see a future where I need to think really hard about how they’re all going to get stored once they’re filled.

In the meantime, The Bullet Journal Method‘s a recommended read if you’re interested in trying the BuJo out or revisiting the foundations. Trust me when I tell you there’s more to get out of it than you’d think.

June 28, 2022

Disruption, White Space, and New York City in 1979

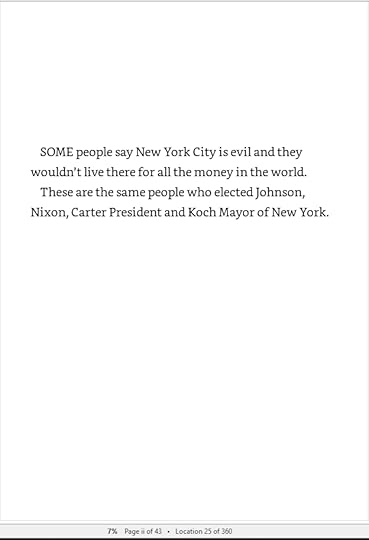

The first lines of text of Kathy Acker’s New York City in 1979 are short and succinct:

SOME people say New York City is evil and they wouldn’t live there for all the money in the world.

These are the same people who elected Johnson, Nixon, Carter President and Koch Mayor of New York.

But of course, rending it like this undoes the impact of that statement, because it’s divorced from the important context of the page. When viewed in the book itself — or, in my most recent re-read, the ebook file — that same collection of words is framed very differently by the white space around them.

I come back to this opening — this prologue — repeatedly to appreciate the heavy lifting it does within the text. The content of the text sets us up for the book that follows, but I’d argue the presentation of the text is equally important. The book starts with an immediate defiance of the most basic of prose conventions, eschewing the page full of text we normally assume is part-and-parcel of such narratives. It foregrounds the coming disruptions in the book, the refusal to obey conventions in style and content alike, but it does so in a way that is unassuming compared to the audacity that follows. If you dislike this four-line opening, the rest of this book is likely to alienate you in ways not yet imagined.

And yet, it’s also a promise to the reader: the effort of engaging with this lack of convention will still bear pleasurable fruit. Prose narratives have always been a curated experience, the author surveys the broader landscape of a character’s fictional life and deciding this moment is worthy of fictional scrutiny and that moment is best kept hidden in the ellipsis between scenes or chapters. This moment is significant for the narrative we’re crafting, and that one is easily ignored.

In this respect, the space around the prose is nuanced and loaded with potential meaning. Acker tights her focus like a poet, evokes a moment — a sentiment — and gets the hell out. Trusts the reader to stitch together the greater meaning in the patchwork of moments that follow, and that the choices where we dip into the flow of the world are highly targeted despite their disparate content. Part of me wishes I had a spare three thousand pounds to invest in some of the original transcripts and publications, to see how the work developed and evolved.

I read a lot of Acker back in the days when I first transitioned from poetry to prose, but it’s only recently that I’ve figured out why her work resonated with me the way it did. The most recent release — a stand-alone Penguin chapbook, which brings me joy — is an interesting study in just how much you can do with 6,000 words if you’re inventive and willing to think about the document as much as the story.

June 21, 2022

Cortisol and Coffee

There’s been very few stretches of my adult life where I haven’t woken up and reached for a cup of coffee first thing in the morning. It’s a core part of my daily routine, as non-negotiable as urination and feeding the cat, and I’m hardly alone in the habit. One of the easiest ways to make my spouse happy is having a cup of coffee waiting for them the moment they wake up, perched on their bedside table beside the phone delivering their wake-up alarm.

Fortunately, this is pretty easy for me to provide, given that we live on slightly different schedules (I get up early to write, they sleep in because they find it harder to fall asleep than I do).

Unfortunately, drinking coffee first thing in the morning is actually a pretty terrible thing to do to your body.

The logic here comes down to cortisol, aka “the stress hormone”. Despite it’s nom-de-plume as a stress marker, bodies naturally produce three cortisone surges throughout the day, and the first of them is right as we wake up. This phenomena — the Cortisol awakening response – means we’re 50% to 77% more cortisone within a half-our of waking up each day. Think of it as your body’s acknowledgement that waking up means shits about to get real, so you’re primed to be alert and deal with the shift from relaxed to engaged.

Except there’s a bunch of stuff that can affect the level of cortisol in your bloodstream upon waking up, ranging from whether you’re a shift worker, whether it’s light out, whether you’re a lark (who naturally produce more cortisol) rather than a night owl, and whenever you have ongoing pain conditions.

It turns out the caffeine in coffee interrupts this cortisol production, causing the body to produce less of the hormone and rely on the coffee instead. Instead of getting the morning energy boost from cortisone, we’re getting it from a substance that we quickly develop a tolerance to.

In this light, optimal coffee consumption usually happens later in the day, when our cortisol levels ebbs (Can’t stomach the thought of going without a hot beverage? Tea might make an interesting substitute — Arthur Chu has a twitter thread on the impact on theanine in tea alongside the caffeine, and why it makes a difference),

Of course, if you’re enjoying your morning coffee, none of this is really meant to be an admonishment and a demand to stop. I read all of this — and wrote all of this — with the mindset of someone who figured “you’ll take my morning cup of coffee out of my cold, dead hands, assholes.”

Except…well, here’s the thing: I do regularly skip the coffee first thing, which has less to do with the science above, and more to do with crime writer Elmore Leanard’s morning routine when he was initially building his career. Leonard would wake up before work and write, and he motivated himself by refusing to drink coffee until he’d written his first 750 words of the day.

I adopted that habit myself when I started a full-time work last year, and the result is that I’m usually y awake for an hour or so before the first cup of coffee hits my system. And it’s definitely taken an edge off my mornings, and made the routines a little easier to cleave to, so long as my day-to-day stress levels aren’t off the charts.

I don’t know that I’ll ever be one of those people who waits two hours for my morning coffee, but I could well be on the way to becoming someone who doesn’t wake up to a cup of Joe first thing.

Cortisole and Coffee

There’s been very few stretches of my adult life where I haven’t woken up and reached for a cup of coffee first thing in the morning. It’s a core part of my daily routine, as non-negotiable as urination and feeding the cat, and I’m hardly alone in the habit. One of the easiest ways to make my spouse happy is having a cup of coffee waiting for them the moment they wake up, perched on their bedside table beside the phone delivering their wake-up alarm.

Fortunately, this is pretty easy for me to provide, given that we live on slightly different schedules (I get up early to write, they sleep in because they find it harder to fall asleep than I do).

Unfortunately, drinking coffee first thing in the morning is actually a pretty terrible thing to do to your body.

The logic here comes down to cortisol, aka “the stress hormone”. Despite it’s nom-de-plume as a stress marker, bodies naturally produce three cortisone surges throughout the day, and the first of them is right as we wake up. This phenomena — the Cortisol awakening response – means we’re 50% to 77% more cortisone within a half-our of waking up each day. Think of it as your body’s acknowledgement that waking up means shits about to get real, so you’re primed to be alert and deal with the shift from relaxed to engaged.

Except there’s a bunch of stuff that can affect the level of cortisol in your bloodstream upon waking up, ranging from whether you’re a shift worker, whether it’s light out, whether you’re a lark (who naturally produce more cortisol) rather than a night owl, and whenever you have ongoing pain conditions.

It turns out the caffeine in coffee interrupts this cortisol production, causing the body to produce less of the hormone and rely on the coffee instead. Instead of getting the morning energy boost from cortisone, we’re getting it from a substance that we quickly develop a tolerance to.

In this light, optimal coffee consumption usually happens later in the day, when our cortisol levels ebbs (Can’t stomach the thought of going without a hot beverage? Tea might make an interesting substitute — Arthur Chu has a twitter thread on the impact on theanine in tea alongside the caffeine, and why it makes a difference),

Of course, if you’re enjoying your morning coffee, none of this is really meant to be an admonishment and a demand to stop. I read all of this — and wrote all of this — with the mindset of someone who figured “you’ll take my morning cup of coffee out of my cold, dead hands, assholes.”

Except…well, here’s the thing: I do regularly skip the coffee first thing, which has less to do with the science above, and more to do with crime writer Elmore Leanard’s morning routine when he was initially building his career. Leonard would wake up before work and write, and he motivated himself by refusing to drink coffee until he’d written his first 750 words of the day.

I adopted that habit myself when I started a full-time work last year, and the result is that I’m usually y awake for an hour or so before the first cup of coffee hits my system. And it’s definitely taken an edge off my mornings, and made the routines a little easier to cleave to, so long as my day-to-day stress levels aren’t off the charts.

I don’t know that I’ll ever be one of those people who waits two hours for my morning coffee, but I could well be on the way to becoming someone who doesn’t wake up to a cup of Joe first thing.

June 19, 2022

POD, Publishing Mad Science, and White Mugs

Two years ago, when I first two my business plan for Brain Jar 2.0, one of my long-term goals was taking the philosophy we used to create books and use it to find other places for written work to exist. Webcomics and artists had been monetizing their art with merchandise for years at that point, and print-on-demand merchandising systems like Redbubble had flourished.

It’s taken me a bit to move on the idea because, frankly, the learning curve and the technology weren’t really at the place I wanted it to be for the audience size I was working with. Much as I love Redbubble and the artist friends who sell there, the lack of integration with other storefronts presented a problem for me — putting merch on Redbubble means pushing people to Redbubble, and 2020 was basically a long exercise in figuring out how important direct sales could be. Other services offered better integration, but were location-centric in a way that wasn’t useful; they could service clients in Europe or American at a reasonable price, but shipping POD products to Australia was…well, prohibitive.

But the nice thing about the new job is having the spoons to dig and research/try stuff out, rather than staring at my to-do list in abject horror. Over the last few weeks, I dug into POD merch options and found a place that actually ticked all the boxes I had around POD products. And since Eclectic Projects exists to try out stuff, serving as Brain Jar’s R&D, I’ve been testing just what I can do with flash fictions, my beloved Futura font, and a plain white mug.

Of course, the point of doing something like this isn’t “oh look, I’m going to sell a billion of these.” The point is to do it, and figure out just how simple it is, because once I’ve got a handle on it there’s so many interesting possibilities. A huge number of writers have a vast back catalogue of pithy, interesting ideas under their belts that they haven’t even thought about monetising (I refer, of course, to Twitter feeds and Facebook Feeds and even Instagram images, plus short forms like poetry and flash fiction); the speed of something like a mug is quick, compared to producing a book, so it’s possible to take something that’s got attention today and offer a product based on it within the space of a few hours.

And, of course, we all have books that are full of pithy, interesting pull quotes that might sound interesting out of context. Books that can suddenly have merch once we wrap our head around the idea, and start thinking about what the world looks like when that’s built into our business model as creators…

The Year The Zombies Came For Christmas

The Year The Zombies Came For ChristmasThree panels, one story. Get a slice of fiction emblazoned on the side of your coffee mug with The Year The Zombies Came For Christmas, a seasonal horror tale from Peter M. Ball. When two young parents who grew up without pets buy the son a dog for Christmas, they think it’s a quaint tradition and a can’t miss gift.

Be a shame if a zombie apocalypse changed things on them…

$9.99Shop nowJune 7, 2022

Making First Moves

This morning I’m pondering the right first move to bed into my daily routine. Right now, I have about four first moves that will kick of my day, depending on which groove I’m in:

Getting up and journaling to park ideas; Getting up and writing directly into the computer; Getting up and doing the day’s Worlde, then posting it to my family chat; Getting up and brain dumping my top-of-mind thoughts into an Omnifocus inbox, then doing a project review and building my diary for the day.Of the four, Wordle is the worst option. Logging in to finish a Worlde puzzle only takes about three minutes, but it puts me in a social mindset because the next step is going into chat, and from there it’s a short skip to spending the entire morning answering email and tooling around on social media.

Journaling is probably my favourite kick-off, but the chain of events that follow that meditative writing often means I’m slow to build up steam for the rest of the day. It’s harder to transition into day job work (or, at least, it was harder to transition into my old day job work), and harder to actually launch into writing projects that aren’t drafting blog posts.

Waking up and drafting is often a good first step — I hit the ground running as a writer, then get coffee after finishing my first 500 words of the day. There’s nice, clean end points that tell me when it’s time to set the manuscript aside and focus on the day job. In many ways, it would be the ideal first move….were it not for the fact that I struggle to write on tired days, and that can throw my entire day out the window.

Writing is also loud, given the ferocity and speed with which I type, which means it’s not my spouse’s favourite first move given they’re usually trying to sleep while I’m hammering out words.

My Omnifocus mindsweep was a relatively new approach, inspired by Kourosh Dini’s Creating Flow With Omnifocus. I picked it up during the chaos of pulling the BWF program in January, when everyone was working from home and our CEO was on leave, and it was great for wrangling my on-the-verge-of-breakdown brain and giving some structure to my day.

It was also great for eliminating the feeling that I was about to miss something important, but also hard-wired into my brain as a dayjob thing that I’m not sure I’ll grock it as a creative kick-off. I also fear that it’ll push me to focus on writing-adjacent tasks, such as publishing or editing, in spaces I’d normally reserve for drafting new work (which also begs the question: is this a bad thing?). Worse, it tends to blur the boundary between “day job” and “not day job” in a way that’s tricky to manage — it largely worked in January because I was working 11 hours days at BWF and there were no boundaries.

Were I working for myself full time as writer and publisher, I suspect it would be the perfect first move. Right now, I’m pondering whether the flexibility of the new work-from-home dayjob makes it worth adopting once more.

I’ve been musing over all fo this for a few days now, and realised that routines are tricky because they’re as much about identity as everything else. Each first move reflects a different fascet of my self-identity, and throws the focus (and delivers solutions for) a particular aspect of the self. None of them are explicitly wrong (although Wordle is less useful), and each delivers benefits that are useful at specific times.

My ideal routine — one jotted down as a thought experiment if writing and publishing was all I’m doing and money wasn’t an object — revealed some interesting gaps. In the scribbled notes I pulled together, the vision of myself in that situation would:

Get up early and go through some kind of exercise/meditation combo to clear my head.Journal for a short stretch, breakfastSpend an hour tinkering with novel plans and making notes about future works.Write 2000 words directly on a computerBreak for lunch, and possibly read a little.Go through the Omnifocus Mindsweep after lunch, to kick off my ‘work’ day in the afternoon., where I focus on publishing and editing.Walk.DinnerMeaningful consumption of media and experiences until bed.I’m honestly surprised that both exercise and novel planning are so prominent in that list, given that they’re largely absent in my current process, but ideal selves aren’t working with any of the limitations that our real selves are negotiating as we bumble through our lives.

Stil, it’s got me thinking about whether a fifth first move is worth considering….

May 31, 2022

Greet The Day

My desk is a disaster zone at the moment. A jagged landscape of poorly stacked notebooks, contracts, and opened mail, with the detritus of my BWF office placed over the top. I love working at my desktop, but I can’t fathom the notion of sitting down and writing there.

Our kitchen is a disaster zone at the moment, too. So is our bathroom, our living room, and my car. Our bedroom is relatively well-composed, although I’m behind on cleaning the CPAP machine and that’s taking a toll on my sleep.

Other disasters: my writing process, my publishing timeline, my PhD deadlines, my planning systems. Invisible chaos that’s largely unnoticeable unless you’re inside my head and trying to wade through the detritus in order to get things done.

The great temptation of chaos is this: nothing is fixable unless everything is flexible, and if you let things slide long enough, the very notion of getting ‘caught up’ is the stuff of nightmares and wry laughter. So you sink into the chaos, doing nothing.

There’s a logic to it: if I don’t wash the dishes, I don’t have to solve the problems with my PhD thesis. I don’t have to email the authors whose books weren’t getting released because BWF ate all my available spoons and threw off all my plans.

I don’t have to deal with the really complicated feelings I have around leaving the Festival, even though it was the right thing to do, or my fear around what happens next.

Of course, I’ve been here before, and I’ve got some pretty well-worn habits that kick in when chaos descends. First and foremost, I reach for Dan Charnas’ Everything In Its Place, and revisiting one of its very first lessons.

On his way to work, LiPuma saw commuters dashing for the subway—flustered, sweating, stumbling—and the next day he’d see those same commuters rushing again. After working in the kitchen, LiPuma couldn’t understand what was wrong with these people. Why not get up a half-hour earlier? Wasn’t greeting your day better than fighting it? Why not make your kid’s lunch the night before, lay out your clothes, do anything you need to do so you can get up and not run around like a maniac so you can smile and enjoy your day? That was, after all, what LiPuma was beginning to do in the kitchen. Stress and chaos were a normal part of his job. But if he could control a little bit of that chaos—preparing for what he knew was going to happen—he could greet chaos, embrace it. His mastery of the expected would enable him to better deal with the unexpected. You plan what you can so you can deal with what you can’t.

Time to take a deep breathe and go back to first principles: Greet the day. Plan first, then arrange my spaces so they’re usable again. Clean as I go and focus on the next action, rather than extrapolating forward to the point of chaos and failure.

I’m not a chef, but any writer knows that stress and chaos is a huge part of the job. You can’t control it, so your main job’s getting back to a space where you roll with the punches a little better.