Jonathan Harnum's Blog, page 48

August 5, 2014

Want to Practice Better? Forget About “Natural” Ability.

One of the most important chapters in The Practice of Practice–chapter 6–has nothing to do with practice directly, it has to do with what you think about musical talent. Is musical ability “natural,” a gift of genetics? Is it something you’re born with? Something you either have or you don’t? Or is musical talent earned through exposure and effort? Your answer will have a profound impact on your practice: your motivation to practice, how you approach practice, whether you persist in the face of challenges, and how deeply you learn when you do practice.

This stems from Carol Dweck’s work on how your ideas about the nature of intelligence affects how you learn. Here’s a superb summary of her work by Trevor Ragan. Dweck’s studies have been replicated and expanded since 1986 when Dr. Dweck first began her investigations. She has a wonderful book out that covers the topic in great detail, called Mindsets.

Music education researcher Bret Smith has found similar repercussions for musicians who hold fixed (innate ability), or fluid (talent is grown) ideas about musical ability. The kicker is that it doesn’t really matter whether musical talent is genetic or not, it’s your ideas about its nature that shape how you practice. Want to learn more about this topic, and 45 other chapters of great material? Pick up a copy of The Practice of Practice. Learn more about the book here.

Related articles

Practice, even with failure, more important than talent – update

Practice, even with failure, more important than talent – update Children’s Implicit Theories of Intelligence: Attributions, Goals, and Reactions to Challenges

Children’s Implicit Theories of Intelligence: Attributions, Goals, and Reactions to Challenges Intelligence and Other Stereotypes: The Power of Mindset

Intelligence and Other Stereotypes: The Power of Mindset How being called smart can actually make you stupid | Neurobonkers | Big Think

How being called smart can actually make you stupid | Neurobonkers | Big Think 3 Ways To Teach Yourself To Become Smarter

3 Ways To Teach Yourself To Become Smarter What’s your mindset?

What’s your mindset?

August 4, 2014

Erin McKeown Talks Practice

Music is unique. The more I know about how it works, the deeper it gets; the better it becomes.

Music is unique. The more I know about how it works, the deeper it gets; the better it becomes.

~ Erin McKeown, from the Interview

_____________________________________________________

Erin McKeown first opened my eyes about how practice can be very different depending on the kind of music you’re making. When I spoke with her, she said a variation of what many non-classical musicians say about practice, “I never practice.” Turns out she was getting better in a different way, one that can be more interesting and more effective than sitting in a room working on scales. The kind of creative approach Erin uses to get better is covered in more detail in Chapters 26 and 38 of The Practice of Practice. Below is a recording of my 2011 interview with Erin, talking about how she gets better.

Interview: Erin McKeown on Practice

I’ve been a fan of Erin’s since hearing Distillation in 2000. Erin is a vocalist and multi-instrumentalist; she plays guitar, piano, drums, and bass. I learned of Erin McKeown’s music about ten years ago through one of many appearances on NPR, this one on The World Cafe, a most excellent show hosted on WXPN in Philadelphia and hosted by David Dye. Great stuff!

Erin’s got 12 albums out, and they’re all worth owning. My favorite 3 albums are Distillation, Grand, and, Hundreds of Lions, three songs from which are re-arranged for her latest release, Three Songs. The arrangements are well-crafted and spare, and I think I enjoy them more than the originals, though that’s a tough call. Erin puts on an energetic live show, too.

Erin’s got a tasty mix of many of my favorite styles: Django, tin-pan alley, singer-songwriter, punk, as well as some old-timey and rockabilly overtones, and when the mood strikes her she might just whip out a Grateful Dead cover. She also sings and plays from the Great American Songbook as well as crafting her own clever and playful originals. If you haven’t heard of her, you should most definitely buy some of her music. Samples below. I mean, how can you not want to hear someone who is inspired in part by The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy?

I hope you enjoy the interview as much as I did. Erin has some interesting things to say about practice.

Here she is singing one of her songs, The Taste of You.

Want to learn more about the best ways to practice? Get an e-mail with a discount code when The Practice of Practice is published (June, 2014). To learn more about the book, check out a sample from The Practice of Practice.

photo by Nancy Palmieri

Erin’s Web Site

Listen to Samples of Erin’s Music

Videos of Erin

…..past Cabin Fever shows

Mentioned in the interview:

Allison Miller, drums (definitely check out her 2010 album, Boom Tic Boom, LA Times named it a top jazz album of the year: mp3, CD)

Adam Levy: guitarist (Norah Jones, Tracy Chapman…) and teacher.

Carrie Rodriguez (samples of her music)

The Drummer’s Cookbook

Sleater-Kinney (mp3, CD): part of the Riot Grrrl scene

Ryan Adams: Demolition (mp3, CD, vinyl)

Haughty Melodic by Mike Doughty

Soul Coughing

Old Town School of Folk Music

Johnny Cash (music samples)

napping and music practice: previous blog post

Natalia Zuckerman (samples of her music)

Erin’s “Cabin Fever” concerts, Episode 3: Water

Other Resources (links from Erin’s Wikipedia Page)

Official home page

Erin McKeown is a Righteous Babe

Washington Post review of We Will Become Like Birds

Interview with Erin McKeown – small WORLD Podcast 2006

Erin McKeown’s April 2006 Daytrotter Recording Session

http://www.daytrotter.com/article/37/free-songs-erin-mckeown

Interview with Erin McKeown – Lesbilicious Magazine 2008

Audio interview with Erin McKeown and Jill Sobule on Well-Rounded Radio, 2009

Woodsongs Old Time Radio Hour Show #552 – WMV Video

Woodsongs Old Time Radio Hour Show #552 – MP3 Audio

Erin McKeown talks to the PBS NewsHour

………………..

And, as a special bonus in tribute to one of Erin’s musical influences and because physical humor is funny, here’s a 10-second clip from the movie version of Hitchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (both the books, and the audiobooks are better than the movie):

If only this happened every time we thought too much….

Have fun and good luck with your practice.

Related articles

Erin McKeown: Hundreds of Lions

Erin McKeown: Hundreds of Lions First Listen: Erin McKeown, ‘Manifestra’

First Listen: Erin McKeown, ‘Manifestra’ Song Premiere: Erin McKeown, ‘The Jailer’

Song Premiere: Erin McKeown, ‘The Jailer’ Erin McKeown & Rachel Maddow Write a Song

Erin McKeown & Rachel Maddow Write a Song Daily Downloads (Erin McKeown, The Belle Brigade, and more)

Daily Downloads (Erin McKeown, The Belle Brigade, and more)

July 27, 2014

Moanin’ at Montreux: The Fruits of Practice

Bobby Timmons

Tasty! This is what lots of practice sounds like. Moanin‘ by Bobby Timmons (lyrics by Joe Hendricks). Here’s the album on Amazon. Thanks, Mike for turning me on to this version!

Performance is also a kind of practice. Learn more about it in chapter 42 of The Practice of Practice.

Karrin Allyson (v)

Frank Chastenier (p)

John Goldsby (b)

Danny Embrey (g)

Greg Field (d)

Related articles

Spotlight on Jazz-Moanin’

Spotlight on Jazz-Moanin’ Classic Jazz Instrumental Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers – Moanin

Classic Jazz Instrumental Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers – Moanin I Love Music XIV

I Love Music XIV Blakey – Drumming in the heart of Hard Bop

Blakey – Drumming in the heart of Hard Bop

July 15, 2014

Go Go Gadget Practice

J. S. Bach (aged 61)

Do you think somebody who merely pushes a button to make music a musician? See the hilarious video below for a negative example, and the following one for a wonderfully positive example.

Bach once said of his prodigious keyboard skills something like, “There’s nothing to it; you just push the right key at the right time and the instrument plays itself.”

Chapter 33 in The Practice of Practice shares the title of this post. That chapter goes into more detail about using gadgets in your practice. I’ve listed some helpful software below the videos.

The important thing with gadgetry is the willful interaction with sound, not the motor ability. Yes, there are varied levels of physical engagement with the sound-producing device, but again, that’s not the point.

Here’s a pretty funny example of when using gadgetry is NOT practice, or even particularly engaging, musically. A few seconds of watching will be enough to get the gist, and probably a chuckle or three, maybe even a facepalm:

In the following video are some thoughts and superb examples of how “button-pushing” can be both musical and engaging. The TED talk is from Ge Wang, an assistant professor at Stanford University. Wang is the founding director of both the Stanford Laptop Orchestra (SLOrk) and the Stanford Mobile Phone Orchestra (MoPho). Some of the over 200 instruments Wang and his students have created are super cool, like the Twilight, demonstrated around 6:15.

__________________________________________________

Chapter 33 in The Practice of Practice goes into more detail about using gadgets in your practice. Below are five gadgets worth exploring:

Farmer Foot Drum (or foot pedal)

Loop Stations (Boss Phrase Looper; Boomerang Phrase Sampler)

iTabla Pro for practicing with drones and a tabla beat

GarageBand: Super fun and intuitive software to play with and make your own compositions, with lots of helpful tutorials on YouTube.

Audacity: Free recording, playback, and sound manipulation software. Also lots of helpful tutorials on YouTube, some of which are from yours truly.

Related articles

The Stanford Laptop Orchestra – Twilight

The Stanford Laptop Orchestra – Twilight Slork Plays MacBook Music

Slork Plays MacBook Music The technology of Stanford’s Laptop Orchestra (video)

The technology of Stanford’s Laptop Orchestra (video)

July 3, 2014

Goals as Fractals and Guerrilla Practice

Hans Jørgen Jensen

Hans Jørgen Jensen is an affable cello teacher from whose studio have come cello players who win in international cello competitions and garner spots in top orchestras around the world. He’s a wonderful teacher and an interesting, busy man. There were many gems to admire when he spoke with me about practice, but the one that sticks in my mind, the one that was powerful enough to make it a chapter in The Practice of Practice was the power of goals. Another chapter covers what I’ve called Guerrilla Practice: snatching a tiny fragment of practice when you can, either once a day or, ideally, throughout the day. Both are covered briefly below.

Setting goals “just right” is one of the most powerful and motivating techniques expert practicers use to get the most out of the practice session, even if you only have two minutes of practice time a day . When I asked Hans Jensen my favorite interview question, if there was one thing he would teach his younger self about practice, he said, “I would try to make my goals more specific: short-term, long-term, and having a big vision of where you’re heading with it.” He teaches his students to set clearly defined, concrete goals. He said, “If there is no dream, and if there is no vision; that’s what we need for having motivation.”

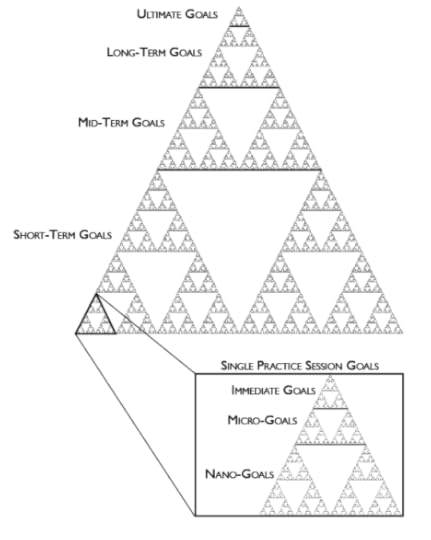

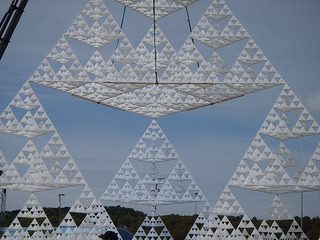

We know about long-term, mid-term, and short-term goals. Except for short-term goals, larger goals are abstract: it’s a challenge to know exactly what to do to achieve them. I envision goals as a fractal, specifically, a Sierpinski fractal, named after the Polish mathematician who discovered it in 1915. You can see below that even the tiniest goal is a part of the larger goal in which it’s embedded, which in turn is part of a larger goal, etc. Here’s the graphic from The Practice of Practice:

The trick for your single practice session is to break down goals even smaller than short-term goals. Immediate goals are what you want to accomplish for the time you have, whether it’s 5 minutes or 2 hours. Micro goals are one specific task you’d like to accomplish, say learning a tough phrase. Nano-goals are a single repetition, the goal of which is to play the repetition flawlessly.

Shrinking goals to the smallest size helps to make concrete exactly what you’ve got to do to improve in that one moment. Approaching practice like this will help you improve even if you only practice 2 minutes a day. One of Hans Jensen’s students was a graduate student strapped for time and she could spare only 2 minutes a day. His student was learning the Popper cello etude #38 (cellist Joshua Roman in the vid isn’t Jensen’s student). Hans said, “It’s a hard etude. It goes fast! I think she worked on it six weeks. At first, for the first two weeks, she only practiced one minute a day. Then we changed to two minutes. It’s really hard! One of the hardest.” Setting tiny, reachable goals was the technique that allowed her to learn the etude.

Kolossen i Frihamnen (Photo credit: Eva the Weaver)

Goals combined with what I’ve called Guerrilla Practice are a one-two punch. I used to think that I needed at least an hour or two to practice, otherwise it wasn’t worth it. Hans said he used to think that, too, but he told me, very emphatically, “That’s totally wrong.” Hans said he had another student who got better lots faster than other players. When Hans asked him what he was doing to get so much better so much faster, he said he used short moments of down time to practice, mostly during group rehearsal warm-up time. Ten or fifteen minutes here and there really adds up.

To learn more about goals and many other helpful practice approaches, get a copy of The Practice of Practice. Buy a paperback copy and get the Kindle edition for free! If you have Amazon Prime, you can borrow a Kindle edition for free.

For more on Hans Jensen’s teaching, check out the wonderful documentary on Vimeo, Taste the String, posted by Richard Van Kleek. All kinds of great stuff in there about learning to play, teaching, and life.

We’re all busy, but I know I can spare at least two minutes a day for an intense burst of practice. I bet you can, too.

Related articles

Jensen Master Class.

Jensen Master Class. Thumb Position

Thumb Position More is caught than taught…

More is caught than taught… don’t practice, just tune: a study on getting to a practice session

don’t practice, just tune: a study on getting to a practice session 10,000 Hours or 22,000 Days?

10,000 Hours or 22,000 Days? Learning to Play the Cello

Learning to Play the Cello Ten Famous Rules Ninety-four Years After

Ten Famous Rules Ninety-four Years After

June 26, 2014

Plays Well With Others: Group Practice

Django Reinhardt

You should know about Django Reinhardt. If you don’t, the documentary Three-Fingered Lightning is the best place to start.

Anyway, all of last week, at Django In June, an intensive guitar camp inspired by Django’s music, I was immersed in practice in all its various guises and all but 30 minutes of it was in group practice. When I say various guises, I mean thinking about music, mental practice, talking about music, and listening to great performances like the one below. All the various guises of practice are covered in lots more detail in The Practice of Practice (a new deal on Amazon allows you to get the paperback at ~20% off and the Kindle edition for free!). But what I’d like to mention is practice time spent with an instrument in the hands, actively making sound with others. We normally think of practice as sitting in a room alone, but practice is much, much more than that, and group practice is a lot more fun, too.

Joscho Stephan with his Volkert D-hole-guitar (grande bouche)

So, during Django-in-June, I practiced with lots of people: in each of the 2 daily classes (rhythm and lead), on the lawn in the shade with my buddy out for the camp from Chicago, but mostly my practice was group jams in which I played rhythm guitar and improvised on trumpet. I’d learned all the tunes, but calling the same dozen or so tunes gets old quickly when you’re playing several hours a day, so there were tons of other songs I stumbled my way through. There were a couple hundred musicians there of widely varying ability and knowledge: violin, mandolin, accordion, clarinet, my lonely trumpet, and a plethora of guitars, both petit bouche and grande bouche, in the Gypsy style.

At the end of the 6 days, my brain was full-to-overflowing, I’d seen some superb musicians making music right in front of me–hello mirror neuron system (it’s in the book)–and my ability to sight read a chord progression (something I can already do fairly well) shot up what felt like an order of magnitude, well beyond anything I’ve experienced practicing alone.

Here are a few suggestions from The Practice of Practice to keep in mind when you’re practicing with somebody else. They’re either questions you can ask directly, if it’s appropriate (often it’s not), or questions to keep in mind as you’re listening to those you’re practicing with.

How do you practice _________? (scales, improvising over ii-V-I, chords, or whatever interests you)

What are you working on?

Here’s what I’m working on. Any thoughts?

I’m having trouble with ___________. How do you deal with that?

How do you work on tone?

How do you work on speed?

How do you work on expression?

How do you place your mics and tweak your amps to get the best sound?

What kind of (insert gear here) do you use, and why? (Could be anything from picks, to amps, to valve oil, to reeds, etc.)

Can you show me a favorite song or lick?

This first video below is from Django In June, two of the headliners, Sebastien Giniaux and Olivier Kikteff. The second is a fun cover of Will Smith’s theme from Fresh Prince of Bel Air on drums. While both of these are more like performances than practice, that’s another myth I’d like to bust: performance is a kind of practice. As is the rehearsal that was required for performances of this caliber. At any rate, you can tell these guys are having a good time.

If this seems like too much to think about or remember, no worries, just play and pay close attention and try to come away with at least one new idea or approach that you can use. That’s the best thing you can do. Folk musicians and jazz musicians already know this. Music is communication without words, and it takes two to tango. Play with others!

————————-

Related articles

Gypsy Jazz Guitar – A One-Man Genre

Gypsy Jazz Guitar – A One-Man Genre Django Reinhardt and the Inspiring Story Behind His Guitar Technique

Django Reinhardt and the Inspiring Story Behind His Guitar Technique Nuages: Django, Le Not So Hot Klub du Denton and Willie

Nuages: Django, Le Not So Hot Klub du Denton and Willie Duke Ellington and Django Reinhardt – “A Blues Riff”

Duke Ellington and Django Reinhardt – “A Blues Riff” 0080 Sweet Sue, Just You – Django Reinhardt (1935)

0080 Sweet Sue, Just You – Django Reinhardt (1935)

June 7, 2014

The Practice of Practice is Published

The Practice of Practice

The Practice of Practice is now available:

U.S., U.K., Spain, France, Germany, Italy, and India!

277 pages

44 Chapters

Illustrations

Extras (learn more)

E-book will be available June 15 worldwide.

Hardcover will be available July 15 (US only).

Talent means nothing when it comes to getting better. Practice is everything. But exactly what is good practice? How does good practice create talent? And what in the world does a pinwheel have to do with practice? The focus of this book is music practice, but these techniques and mindsets can be applied to any skill you want to improve.

Drawn from interviews with world-class musicians, published research, and personal experience, this book covers essential practice strategies and mindsets you won’t find in any other book. You’ll learn the What, Why, When, Where, Who, and especially the How of great music practice. You’ll learn what research tells us about practice, but more importantly, you’ll learn how great musicians in many genres of music think about practice, and you’ll learn the strategies and techniques they use to improve. This book will help you get better faster, whether you play rock, Bach, or any other kind of music.

Whatever instrument you want to play, The Practice of Practice will help you get the most out of your practice. This book will help you become more savvy about getting better. It will also help you be a more informed teacher or a more effective parent of a young learner.

Don’t practice longer, practice smarter.

_______________________________________________________

What’s in the Book

What (6 chapters): Definitions of what music practice is (and isn’t). Also learn about the neural mechanisms of learning and what music practice does to your brain.

Why (5 chapters): Motivation is crucial. Learn ways of keeping the flame lit in this section.

Who (5 chapters): A lot of people (including yourself) will impact your practice. Learn about who they (and you) are, and how they’ll help your practice.

When (6 chapters): This section covers how much, and what times of the day are best for practice, as well as the development of practice skill over time.

Where (5 chapters): Where you practice affects how well you practice. Learn to harness the place of your practice.

How (18 chapters): Three times longer than the next longest section of the book, this section includes information about goals, structuring your practice, as well as specific strategies pros use to get better and effective practice techniques tested by researchers.

The Book Also Contains:

The Book Also Contains:Helpful Visual Aids: A picture is worth a thousand explanations. To the left are just a few of the diagrams, pictures, and illustrations used in the book to make the ideas stick in your head better.

QR Codes and Web Links: Nearly every chapter contains links to carefully selected extra content online, rich content that will extend and reinforce what you’ve learned in each chapter. With a smart phone and a QR code reader, you can access If you’re reading on a Web-connected e-book, you can click on the link and go to the extra online goodies.

Extra Online Content Includes:

video/audio of great performances

interesting talks

interviews on practice

great books and recordings

helpful practice gadgets

many useful practice tools

May 31, 2014

Feeling Stuck in Your Practice (and Getting Unstuck)

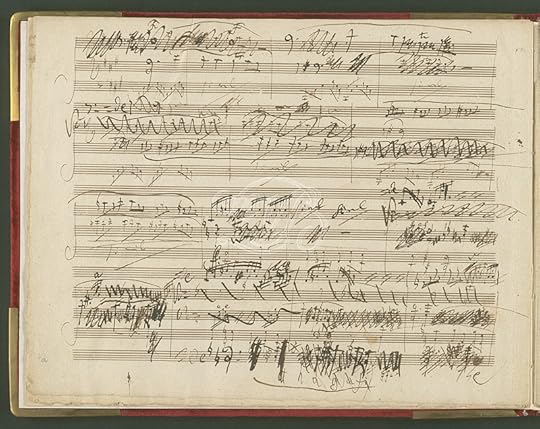

The idea of being (or feeling) “stuck” isn’t usually included in our ideas about practice. When we see these luminaries of music, it’s easy to imagine they have no struggles, that music simply flows from them. But that’s not the case. Music is work. A labor of love, to be sure, but still, a labor. A labor fraught with error and the necessary correction, a labor in which the feeling of being stuck is common. Listening to Sting talk about being stuck, I thought of the Beethoven manuscript mentioned in The Practice of Practice. It’s covered with scribbled errors, and is clearly unfinished. It’s refreshing to see the errors of a Grand-Master musician.

Below, Sting talks about being stuck. Being stuck is one of the few constants I’ve found talking to great musicians about practice. Feeling stuck seems to be a feature of the struggle to get better, because good practice is all about tackling something unfamiliar; it can be difficult to see or feel progress, even when it’s there. Every one of the musicians I’ve spoken with about practice, when asked if they ever get stuck, says a variation of, “all the time,” or even “every day.” They all use a variation of the same thing to overcome that block. Creativity.

Creativity is an essential part of the process of practice. It might be that you practice by writing songs, like Erin McKeown, and so many others; it might be that you invent exercises, like NY Philharmonic trumpeter Ethan Bensdorf; it might be that you re-tune your guitar like Nicholas Barron; you might take a creative approach to the entire practice session like Ingrid Jensen; it might be that you simply change the lighting or take your shoes off like Rex Martin recommends to his students who are bored or stuck. Whatever you do to make practice interesting, I salute you. If you’d like to learn more about using creativity in your practice, check out The Practice of Practice (get 10% off by using the code LGSQC94V when you check out).

Here’s Sting performing and talking about how he overcame being stuck:

Related articles

Procrastination Cure – Get Unstuck Using Fun and Find Time!

Procrastination Cure – Get Unstuck Using Fun and Find Time! Getting Unstuck

Getting Unstuck Creative Unstucking – The Best of Unstucking Advice

Creative Unstucking – The Best of Unstucking Advice Creativity Tip Sheets from Unstuck

Creativity Tip Sheets from Unstuck Sting – The Last Ship

Sting – The Last Ship Bob Dylan on Sacrifice, the Unconscious Mind, and How to Cultivate the Perfect Environment for Creative Work

Bob Dylan on Sacrifice, the Unconscious Mind, and How to Cultivate the Perfect Environment for Creative Work

May 22, 2014

Compose Yourself: Songwriting & Composition as Practice

Daniel Deutsch

Songwriting as a means of practice is a great idea! The engagement with the sound you’re making goes deeper than when you practice scales, or other techniques, because you own (on many levels) the sounds you’re creating. And you don’t have to have special skills to do it, just dive in and start figuring it out. Daniel Deutsch is a teacher of composition who gives some superb examples in this NAfME article :

He says, “Because most of us learned composition in theory class, there is a natural tendency to teach composition as a set of theory exercises, using narrowly prescribed formulas. In my opinion, it is better to start with idea, expression, and emotion. “How does it feel to score a goal in soccer? Let me hear that in your musical idea!”

I believe anybody can be a composer or songwriter, and the added ability to express emotion helps make living in this crazy world a little better. You don’t have to write anything anybody else will hear. Think of composing like writing a journal. You’re not going to show that to anybody. Why would you? It’s too personal. Composing is a process, not a product, and that process will further your musical ability.

Erin McKeown

Composing the music and lyrics for songs is one of the ways singer-songwriter Erin McKeown got her chops. During her high school years she began spending a lot of time with her 4-track recorder, making songs. If you’ve written a song before, you know there is a lot of trial-and-error, a lot of repetition, a lot of assessment. But it doesn’t feel like “normal” practice because it’s fun and engaging.

I love seeing how creators create, whether it’s authors, songwriters, composers, visual artists, whoever. There’s a new way to gain some insight into songwriters’ process over at the Song Exploder podcast. Pretty cool resource. Read Songwriters on Songwriting for even more good insights. If you’re a teacher, you need Maud Hickey’s excellent book on teaching composition, Music Outside the Lines.

I love seeing how creators create, whether it’s authors, songwriters, composers, visual artists, whoever. There’s a new way to gain some insight into songwriters’ process over at the Song Exploder podcast. Pretty cool resource. Read Songwriters on Songwriting for even more good insights. If you’re a teacher, you need Maud Hickey’s excellent book on teaching composition, Music Outside the Lines.

Whether it’s writing a short melody, creating a song, or composing a motet, give composition a try. Engaged practice is the best practice.

Related articles

The Healing Power of Songwriting II: Q&A with Mary Gauthier

The Healing Power of Songwriting II: Q&A with Mary Gauthier Songwriter’s Revenge: Writing Heartbreak Into Country Songs Is Sweet Retribution

Songwriter’s Revenge: Writing Heartbreak Into Country Songs Is Sweet Retribution Songwriters on Songwriting: Suzanne Vega

Songwriters on Songwriting: Suzanne Vega “Jolene”

“Jolene”

April 27, 2014

The Real Deal-With-The-Devil at the Crossroads: Tackling the Monster (Marsalis and Ma)

There is no deal with the Prince of Darkness at the crossroads, but what a great myth. The crossroads is inside the ‘shed, and the devil you’re dealing with is practice. Check out what Yo-Yo Ma and Wynton Marsalis have to say about practice. In these 3 videos, you’ll hear Wynton expound on his 12 rules of practice. Some fly 80s styles going on in there, too. Great stuff:

this last one sums up Wynton’s 12 “rules” of practice, and has some more material by Yo-Yo Ma:

Related articles

12 Rules of Practice, from Wynton Marsalis

12 Rules of Practice, from Wynton Marsalis Willie Nelson and Wynton Marsalis

Willie Nelson and Wynton Marsalis Faust/Marsalis: Why the Arts Matter

Faust/Marsalis: Why the Arts Matter