Jonathan Harnum's Blog, page 41

February 1, 2016

Great Introduction to the Pipe Organ

A little more basic than the usual fare here, but it’s a nice performance, with rhyme, music, and knowledge. What’s not to like?

January 14, 2016

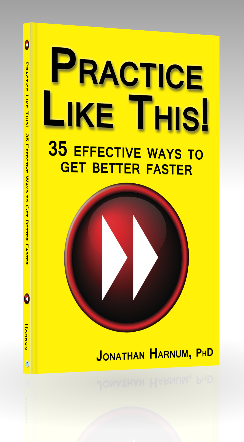

3 Free Books: Jumpstart Your Music

Happy New Year! I hope your music skills get a big boost this year. Here’s a gift of 3 great books to help make it happen. Click on the cover to get the free Kindle edition. Two of them are frequently #1 bestsellers in their category on Amazon.

To get yours, “buy” it for $0 on Amazon. Then it’s downloaded automagically. If you don’t have a Kindle reader, no worries. The app is free and works on all phones and pads.

Help me out and share this far and wide, and thanks. Best wishes for you in 2016!

Jon

January 10, 2016

Wynton Marsalis: 12 Rules of Practice

Wynton Marsalis knows how to practice. As a younger man, he was equally at home in front of a symphony orchestra playing the Haydn concerto, or laying down some serious jazz with Art Blakey. Check out Wynton’s discography for more evidence of his skill and artistry. That’s what tens of thousands of hours of practice sounds like. Check out his 12 Rules of Practice after the video.

Subscribe to live concert video/audio feeds from Jazz at Lincoln Center, where you’ll hear the world’s best jazz musicians doing their thing in real time. On the LiveStream site you can check out other feeds, too. Wynton latest appearance at Ronnie Scott’s in the UK was a concert I enjoyed a lot. Knowing it’s happening live is pretty cool. Here’s a concert from Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra highlighting the music of jazz titans Duke Ellington, John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charles Mingus. Great stuff!

Here are 12 practice suggestions from Master Marsalis. Each one could be the subject of a book on its own. After the videos, I’ve added some suggestions to consider below each of Wynton’s practice rules. Some of them are covered in more detail in the book, The Practice of Practice.

Seek out the best private instruction you can afford.

Write/work out a regular practice schedule.

Set realistic goals.

Concentrate when practicing

Relax and practice slowly

Practice what you can’t play. – (The hard parts.)

Always play with maximum expression.

Don’t be too hard on yourself.

Don’t show off.

Think for yourself. – (Don’t rely on methods.)

Be optimistic. – “Music washes away the dust of everyday life.”

12. Look for connections between your music and other things.

Suggestions for Each Practice Rule:

I interviewed world-class musicians in lots of musical genres for The Practice of Practice. Here are just a few of the tidbits. Get the book for more.

1. Seek out the best private instruction you can afford.

In a study by Sosniak, she found that most accomplished classical musicians’ first teachers lived in the neighborhood, and that teacher was instrumental (haha) in finding the second teacher. Find someone close by who is willing to teach you.

Teachers are also be the people you play with, or hang out with. Just getting together to play and talk about music with a few people is a fun way to spend some time, and can teach you a lot. Make a point of getting together regularly to make music with other people. One fun option anyone can do is free improvisation.

2. Write/work out a regular practice schedule.

Sitting down to think through how and when and where you’ll practice will help make it happen. Daily, 20 minutes or more. Fund

Fundamentals like breathing (for wind instruments), tone quality (everyone), relaxed playing posture, intonation….

Playing with drones is a super-fun and rewarding way to hone all these abilities. Play with a great drone from Prasad Upasani’s app, iTabla.

Pick one song, or one part of a song, to work on. And then….

3. Set realistic goals.

Setting easy goals is better, at first, but continue to challenge yourself.

What’s the easiest goal you can set?

What’s your ultimate goal?

Writing out 10-year goals, 5-year goals, 1 year goals, 1 week goals, and any other that come to you can be helpful.

Think big when you imagine long-term goals.

Make your goals easier the closer you get to the present moment. What is your goal for the next practice session? Keep it short and simple.

A great first goal is to sit down in the chair for 20 minutes of practice, 5-6 days a week.

4. Concentrate when practicing.

Easier said than done. Choosing small, realistic goals will help you concentrate.

5. Relax and practice slowly.

It takes time and repetition for the brain to grow synaptic connections and lay thin coats of myelin over them. By playing slowly, you can more easily avoid and address errors.

6. Practice what you can’t play. – (The hard parts.)

Tuba legend Rex Martin says he never labels anything as “hard,” or “difficult,” because that sets up an expectation of the thing. Instead, he prefers to identify these parts as “unfamiliar.” Through repetition and careful study, they become familiar, and “easy.”

When accomplished practicers get a piece of new music, the immediately identify the “most unfamiliar” parts, the parts that look most challenging. These are tackled first.

7. Always play with maximum expression.

Listening to great musicians will help immensely.

8. Don’t be too hard on yourself.

Buddha is said to have said, “You yourself, as much as anyone else in the entire Universe, deserve your love and affection.

9. Don’t show off.

And while I’m quoting people, why stop now. CS Lewis said, “Humility is not thinking less of yourself. Humility is thinking of yourself less.”

To me, showing off is a weird combination of needy and aggressive. Nobody really likes showoffs because the point is the performer, not the music.

10. Think for yourself. – (Don’t rely on methods.)

You don’t get harmony when everyone sings the same note. (Doug Floyd)

11. Be optimistic.

“Music washes away the dust of everyday life.”

12. Look for connections between your music and other things.

Related articles

November 29, 2015

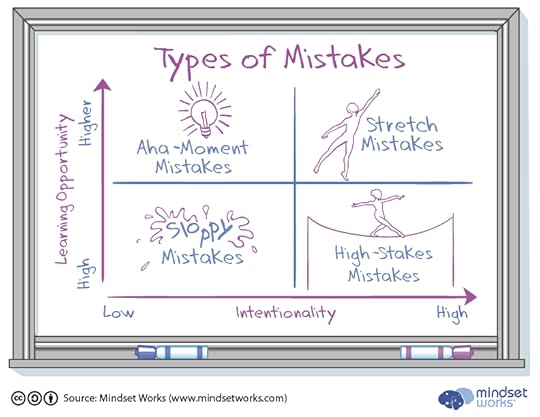

Failing Better: The 4 Types of Mistakes (and how to learn from them)

By MindShiftNOVEMBER 23, 2015

SHARE

by Eduardo Briceño

This article was first published in the Mindset Works newsletter .

We can deepen our own and our students’ understanding of mistakes, which are not all created equal, and are not always desirable. After all, our ability to manage and learn from mistakes is not fixed. We can improve it.

Here are two quotes about mistakes that I like and use, but that can also lead to confusion if we don’t further clarify what we mean:

“A life spent making mistakes is not only most honorable but more useful than a life spent doing nothing” – George Bernard Shaw

“It is well to cultivate a friendly feeling towards error, to treat it as a companion inseparable from our lives, as something having a purpose which it truly has.” – Maria Montessori

These constructive quotes communicate that mistakes are desirable, which is a positive message and part of what we want students to learn. An appreciation of mistakes helps us overcome our fear of making them, enabling us to take risks. But we also want students to understand what kinds of mistakes are most useful and how to most learn from them.

Types of mistakes

The stretch mistakes

Stretch mistakes happen when we’re working to expand our current abilities. We’re not trying to make these mistakes in that we’re not trying to do something incorrectly, but instead, we’re trying to do something that is beyond what we already can do without help, so we’re bound to make some errors.

Stretch mistakes are positive. If we never made stretch mistakes, it would mean that we never truly challenged ourselves to learn new knowledge or skills.

Sometimes when we’re stuck making and repeating the same stretch mistake, the issue may be that we’re mindlessly going through the motions, rather than truly focusing on improving our abilities. Other times the root cause may be that our approach to learning is ineffective and we should try a different strategy to learn that new skill. Or it may be that what we’re trying is too far beyond what we already know, and we’re not yet ready to master that level of challenge. It is not a problem to test our boundaries and rate of growth, exploring how far and quickly we can progress. But if we feel stuck, one thing we can do is adjust the task, decreasing the level of challenge but still keeping it beyond what we already know. Our zone of proximal development (ZPD) is the zone slightly beyond what we already can do without help, which is a fruitful level of challenge for learning.

We want to make stretch mistakes! We want to do so not by trying to do things incorrectly, but by trying to do things that are challenging. When we make stretch mistakes we want to reflect, identify what we can learn, and then adjust our approach to practice, until we master the new level of ability. Then we want to identify a new area of challenge and continue stretching ourselves.

The aha-moment mistakes

Another positive type of mistake, but one that is harder to strive or plan for, is the aha-moment mistake. This happens when we achieve what we intend to do, but then realize that it was a mistake to do so because of some knowledge we lacked which is now becoming apparent. There are lots of examples of this, such as:

When we lack the content knowledge: e.g. not finding water, we try to extinguish a fire with alcohol, which we didn’t realize is flammable.

When we find there is more nuance than we realized: e.g. in our painting, we color a sun near the horizon as yellow, and later notice that the sun does not always look yellow.

When we make incorrect assumptions: e.g. we try to help someone else, thinking that help is always welcome, but we find out that the person did not want help at that moment.

When we make systematic mistakes: e.g. a fellow educator observes us doing a lesson and later points out, with compelling back-up data, that we tend to call on Caucasian girls much more often than we do other students.

When we misremember: e.g. we call a friend for their birthday on the right date, but the wrong month.

We can gain more aha moments from mistakes by being reflective. We can ask ourselves What was unexpected? Why did that result occur? What went well and what didn’t? Is there anything I could try differently next time? We can also ask people around us for information we may not be aware of, or for ideas for improvement.

The sloppy mistakes

Sloppy mistakes happen when we’re doing something we already know how to do, but we do it incorrectly because we lose concentration. We all make sloppy mistakes occasionally because we’re human. However, when we make too many of these mistakes, especially on a task that we intend to focus on at the time, it signals an opportunity to enhance our focus, processes, environment, or habits.

Sometimes sloppy mistakes can be turned into aha moments. If we make a mistake because we’re not focused on the task at hand, or we’re too tired, or something distracted us, upon reflection we can gain aha-moments on how to improve, such as realizing we’re better at certain tasks after a good night’s sleep, or that if we silence our gadgets or close our doors we can focus better.

The high-stakes mistakes

Sometimes we don’t want to make a mistake because it would be catastrophic. For example, in potentially dangerous situations we want to be safe. A big mistake from the person in charge of security in a nuclear power plant could lead to a nuclear disaster. We don’t want a school bus driver to take a risk going too fast making a turn, or a student in that bus to blindfold the bus driver. In those cases, we want to put processes in place to minimize high-stakes mistakes. We also want to be clear with students about why we don’t want the risk-taking behavior and experimentation in these situations, and how they’re different from learning-oriented tasks.

Aside from life-threatening situations, we can sometimes consider performance situations to be high-stakes. For example, if going to a prestigious college is important to someone, taking the SAT could be a high-stakes event because the performance in that assessment has important ramifications. Or if a sports team has trained for years, working very hard to maximize growth, a championship final can be considered a high-stakes event. It is okay to see these events as performance events rather than as learning events, and to seek to minimize mistakes and maximize performance in these events. We’re putting our best foot forward, trying to perform as best as we can. How we do in these events gives us information about how effective we have become through our hard work and effort. Of course, it is also ok to embed learning activities in high-stakes events that don’t involve safety concerns. We can try something that is beyond what we already know and see how it works, as long as we realize that it may impact our performance (positively or negatively). And of course, we can always learn from these performance events by afterwards reflecting and discussing how things went, what we could do differently next time, and how we could adjust our practice.

In a high-stakes event, if we don’t achieve our goal of a high test score or winning the championship, let’s reflect on the progress we’ve made through time, on the approaches that have and haven’t helped us grow, and on what we can do to grow more effectively. Then let’s go back to spending most of our time practicing, challenging ourselves, and seeking stretch mistakes and learning from those mistakes. On the other hand, if we achieve our target score or win a championship, that’s great. Let’s celebrate the achievement and how much progress we’ve made. Then let’s ask ourselves the same questions. Let’s go back to spending most of our time practicing, challenging ourselves, and growing our abilities.

We’re all fortunate to be able to enjoy growth and learning throughout life, no matter what our current level of ability is. Nobody can ever take that source of fulfillment away from us.

Let’s be clear

Mistakes are not all created equal, and they are not always desirable. In addition, learning from mistakes is not all automatic. In order to learn from them the most we need to reflect on our errors and extract lessons from them.

If we’re more precise in our own understanding of mistakes and in our communication with students, it will increase their understanding, buy-in, and efficacy as learners.

Eduardo Briceño is the Co-Founder & CEO of Mindset Works , which he created with Carol Dweck, Lisa Blackwell and others to help people develop as motivated and effective learners. Carol Dweck is still on the board of directors, but has no financial interest in or income from Mindset Works. The ideas expressed in this article, which was first published in the Mindset Works newsletter, are entirely Eduardo Briceño’s.

November 23, 2015

John Coltrane on Practice and More

Right off the bat in this 1966 interview with John Coltrane, he touches on where he practices, and how he leaves his instruments out and at the ready, like when he says, “My flutes are by the bed, so when I’m tired I can lay down and practice.”

Strategies Coltrane mentions and many more are covered in The Practice of Practice. Check out the rest of the 1966 interview with John Coltrane below (start at 0:33).

November 19, 2015

Practice Like This: Free KINDLE Edition Today Only (11-20-15)

Today only (11-20-15), get a free KINDLE edition of the new book, Practice Like This.

ALERT: Don’t be confused by Amazon’s unfortunate placement of the “Read for Free” button. That’s for the Kindle Unlimited Program (which is great, but different from this free offer). You have to “buy” the book and put it in your cart. Then check out and you’ll be “charged” $0.00 and you’ll be able to download Practice Like This to your Kindle or your Kindle app.

Don’t have a Kindle reader? No problem! There’s an app for that. Get it free here.

Free KINDLE edition today only. 11-20-15.

November 18, 2015

What Lots of Practice Sounds Like: Daniel Diaz

November 16, 2015

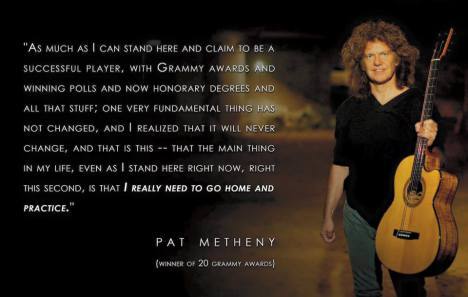

When Do You Get to STOP Practicing?

Tuba master Rex Martin said, “If you’re not trying to get better, you’re getting worse.” That quest to continue exploring your instrument, to continue investigating sounds, to continue to bump up against what you can’t do, is a beautiful thing, a quest that can fill a lifetime. And this goes for any practice: spiritual practice, sports, chess, parenting, the challenge of being the human being you want to be.

And the thing is, no matter how good you get, you can continue to improve and deepen your understanding. Embrace the struggle, enjoy the process. The obstacle is the path.

Here’s what that unending practice sounds like from Pat Metheny.

_________________________________________

Don’t practice longer, practice smarter. Free shipping worldwide at Sol Ut Press.

Related articles

C&L’s Late Nite Music Club With Pat Metheny: ‘Bright Size Life’

C&L’s Late Nite Music Club With Pat Metheny: ‘Bright Size Life’ Pat Metheny – This Belongs To You (The Unity Sessions)

Pat Metheny – This Belongs To You (The Unity Sessions)

November 11, 2015

What Every Musician Needs: Mo’ Rhythm (there’s an app for that)

As Duke Ellington taught us, “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.” Rhythm is the most fundamental of musical elements. It’s the glue that holds everything together. A clue to how powerful rhythm is can be heard when a “wrong” note played with a funky rhythm: it still sounds good.

There is a new tool that can help you acquire better rhythm for yourself in a fun and easy way: Mo Rhythm Africa, from San Diego percussionist and teacher Monette Marino. More on the app below, after the video.

In The Practice of Practice, there’s a chapter on acquiring rhythm skills using a conga or other percussion instruments, like djembe, one of the coolest sounding drums on the planet. The djembe is a drum invented and used originally in the Mali region of West Africa, but has been adopted all over the planet. One of the world-class musicians who shared their practice experience for the book was djembefola master Sidiki Dembele (he’s the player in white in this example).

You don’t have to be a world class expert to get something from the djembe. Marino’s app, Mo Rhythm Africa will help you acquire the traditional rhythms on djembe (and also on dunun, another drum used in this tradition). If you’re new to this kind of music, each traditional rhythm (there are 10 in the app) has instructional videos that go along with them, and they’re only 99 cents for around 5 videos. Here’s a quick diagram, but you can learn more at Monette Marino’s site.

November 6, 2015

Evidence of Practice: Kaki King’s Guitar & Light Show

The first time I heard Kaki King about ten years ago, her playing blew me away. This mesermizing TED performance is evidence of lots of practice, and not just the musical kind. Playing around with effects and images is another way to keep practice interesting. Check her out!

____________________________________

Don’t practice longer, practice smarter. Free shipping worldwide at Sol Ut Press.

Related articles

The Hum returning in October w/ Kaki King, Half Waif, Emily Wells, Ava Luna members & more

The Hum returning in October w/ Kaki King, Half Waif, Emily Wells, Ava Luna members & more