Jonathan Harnum's Blog, page 42

November 2, 2015

TODAY ONLY: 2 Free Kindle Books on Practice (11-2-15)

Happy November! For today only (11-2-15), get the free Kindle edition of The Practice of Practice (a longer-form read on music practice) and Practice Like This (all killer, no filler version on practice in general).

Don’t practice longer, practice smarter. On Amazon,free shipping worldwide at Sol Ut Press, and from your favorite bookstores.

Warning: Don’t fall for Amazon’s unfortunate button placement. You DO NOT have to sign up for Kindle Unlimited to get the books for free. You must “purchase” the books by putting them in your cart, and then check out. You’ll be “charged” $0.00, and then you’ve got the books!

October 21, 2015

Meklit Hadero: Finding Musical Inspiration In Everyday Sounds

In the second video below, singer-songwriter Meklit Hadero (discography) gives a fun talk about finding musical inspiration in everyday sounds. That kind of inspiration leads to musical discoveries and compositions like Kemekem (with Ethiopian musician Samuel Yirga):

Here’s Hadero’s short talk about finding inspirational sounds in the most ordinary places. She hints at the creative kind of practice mentioned in the last blog post, and covered more deeply in The Practice of Practice and Practice Like This: Songwriting as practice. It’s a particularly powerful form of practice because you own what you’re doing, it’s exploratory, and best of all, it’s fun and can make time fly. Check out Meklit Hadero:

____________________

Don’t practice longer, practice smarter. On Amazon, free shipping worldwide at Sol Ut Press, and from your favorite bookstores.

October 14, 2015

Play With Yourself: How to Get Better With Multi-tracking

One of the revelations I discovered while researching The Practice of Practice was that some musicians–like Erin McKeown who turned me on to the strategy–use composition and multi-tracking, or looping, to improve. Trumpet Wizard Adam Rapa breaks down why using multi-tracking is so good for your practice from a blog post over at the fantastic 21st Century Brass site. Check it out below.

You can use a free program like Audacity or Garage Band, or get a loop pedal (I just received a Boomerang and am dying to mess around with it in practice).

Here’s the video and the post from Adam Rapa. If nothing else, check out Poopy Pants Blues, which is multiple tracks of Adam’s incredible playing (starts at 7:33)

Many of the major growth-spurts I’ve experienced as a trumpet player can directly be attributed to spending lots of time multi-tracking myself. This has been one of the most important factors in my development, without a doubt.

When you multitrack yourself, whether harmonizing an exercise or playing all of the trumpet parts in a big band chart or orchestral excerpt, this is the artistic process you go through:

1) You make choices. Lots of them. Nuances of phrasing, rhythmic placement, dynamics, articulation quality, etc. This is where you get to develop and refine your artistic preferences.

2) You accurately apply these choices to every part you record, to the best of your ability.

3) You listen back to all of the parts combined and decide if you’re satisfied with the choices you’ve made and with your level of accuracy in executing those choices.

Then, you’ve either got a recording you’re happy with, or you go back to step #1 or 2.

Rinse, repeat.

In some cases, you’ll be happy with the choices you’ve made, but aren’t satisfied with the playing. Perhaps there are too many out-of-tune notes ruining the chords. Or you’re happy with the playing, but after hearing all of the parts together, you decide to make different choices. Maybe you’d prefer to exaggerate the dynamics or articulations a little more; play something softer, or more swingin’; anything that will add greater character in the music. After all, now that you’re multi-tracking, it IS music!

Doing this regularly can have remarkable effects on your playing. First, you’re practicing being CONSCIOUS; truly, fully conscious of every tiny detail within your playing, which by itself will bring drastic growth. You may be surprised in the beginning (perhaps because of how awful your first few multi-trackings sound…) by how much junk in your playing normally goes by either unnoticed or at least untended. But not anymore! Now that you’re multi-tracking yourself, you’re fully accountable, fully conscious, and honing your skills at a much faster rate!

In addition, you’re practicing consistency. Consistency is obviously one of the best traits we can develop, and is essential both in live performance and studio recording.

I LOVE recording sessions and I have the pleasure and honour of recording with world class musicians and producers. From Gospel records to Bollywood film scores, Hip-Hop tracks to Disney productions, the one thing all of those sessions have in common is this: Studio time is expensive and the person paying for it is counting on me to nail my parts as quickly as possible.

Here’s what I do: Start with the melody or lead line, then double it for thickness (a very common recording technique). Then record a harmony part while listening to the first part, and double it. Same thing with any additional harmony parts. In eight passes, I’ve just recorded four horn parts, each part twice, each one a keeper. Instant trumpet section! No cleaning needed, no time wasted. Being able to do THIS will certainly ensure that you’ll be called back again and again.

That’s exactly the kind of experience you’ll be training for by turning your practice sessions into recording sessions. And what better way to turn those “boring” technical exercises into something fun? What would normally be a musically uninspiring scale study can become a beautiful array of chords; an assigned task of sheer drudgery can become a labor of love and something to be proud of. Think of exercises as potent medicine for curing some kind of technical or harmonic limitation, and multi-tracking as the “spoonful of sugar”.

Keep in mind that your first few recordings will probably sound pretty rough. Don’t let this deter you from making more recordings. It will definitely get better over time, as long as you’re proactively working towards improving your pitch and timing every time (among other aspects of your playing). After all, it’s been said that “perfect practice makes perfect.” If you focus, you will improve.

Once you’ve gotten some experience with multi-tracking yourself and your recordings are pretty clean, try doing what I do and challenge yourself by recording each line without listening to the other lines, seeing how close you can get. All of the exercises I played in this video were recorded without listening to the other tracks, and without any editing. Often times, this is a humbling test of your pitch and rhythmic accuracy and a strong motivation to be even more mindful of the tiniest details in every note you play.

I hope you find this article and video helpful, and that you’ve become inspired to incorporate this wonderful format into your daily playing.

____________________

Learn more about how best to practice. Don’t practice longer, practice smarter. The Practice of Practice, by Jon Harnum. On Amazon, Sol Ut Press, and bookstores.

October 12, 2015

Frustrated With Practice? Listen Boston Brass’s Lance LaDuke’s Talk

Watch, listen and learn. Lance LaDuke talks about overcoming frustration with practice, what to focus on in practice, and how to think about (and do) practice. Great stuff on setting goals in video 2.

____________________

Learn more about how best to practice. Don’t practice longer, practice smarter. The Practice of Practice, by Jon Harnum. On Amazon, Sol Ut Press, and bookstores.

October 6, 2015

How to Succeed In Music Without Really Trying (TRUTH!)

October 1, 2015

Free Kindle Edition of “Basic Music Theory: How to Read, Write, and Understand Written Music” (Oct. 1-5)

Free Kindle Edition: Basic Music Theory: How to Read, Write, and Understand Written Music (October 1-5, 2015)

Free Kindle Edition: Basic Music Theory: How to Read, Write, and Understand Written Music (October 1-5, 2015)It’s Fall giveaway time again! Until October 5th, get a free Kindle copy of the book from Amazon. Cheers!

Don’t forget to check out the online extras here.

September 28, 2015

The Importance of Patience in Practice

In a Skype talk with a colleague in Bratislava (ain’t technology grand?), the topic of how to teach patience arose. Today, this talk came across the wire, addressing that very topic.

Because there are an infinite number of things that need attention in our quest to improve, it can be a challenge for beginners–or anyone, for that matter–to focus on the smaller details for long enough to perfect them. That takes patience. Here is a perspective on patience from artist/teacher/scholar Jennifer L. Roberts. You can read the transcript, or listen to the video below.

This is an important topic, for both teachers and learners, for two reasons. First, we all want to be better RIGHT NOW, and that can overwhelm the biological need to learn slowly (check out Myelin for more on this). Given our instant-gratification culture, brought about by digital enhancement, the experience of slow learning is becoming more and more remote. Why think about it when you can just Google it?

This talk conveys intriguing, important ideas about patience and learning. Hope you enjoy (the sound gets better after a minute or so).

The transcription (thanks to Harvard Initiative for Teaching and Learning for the original post):

I‘M NOT SURE there is such a thing as teaching in general, or that there is truly any essential teaching strategy that can be abstracted from the various contexts in which it is practiced. So that we not lose sight of the disciplinary texture that defines all teaching, I want to offer my comments today in the context of art history—and in a form that will occasionally feel like an art-history lesson.

During the past few years, I have begun to feel that I need to take a more active role in shaping the temporal experiences of the students in my courses; that in the process of designing a syllabus I need not only to select readings, choose topics, and organize the sequence of material, but also to engineer, in a conscientious and explicit way, the pace and tempo of the learning experiences. When will students work quickly? When slowly? When will they be expected to offer spontaneous responses, and when will they be expected to spend time in deeper contemplation?

I want to focus today on the slow end of this tempo spectrum, on creating opportunities for students to engage in deceleration, patience, and immersive attention. I would argue that these are the kind of practices that now most need to be actively engineered by faculty, because they simply are no longer available “in nature,” as it were. Every external pressure, social and technological, is pushing students in the other direction, toward immediacy, rapidity, and spontaneity—and against this other kind of opportunity. I want to give them the permission and the structures to slow down.

In all of my art history courses, graduate and undergraduate, every student is expected to write an intensive research paper based on a single work of art of their own choosing. And the first thing I ask them to do in the research process is to spend a painfully long time looking at that object. Say a student wanted to explore the work popularly known as Boy with a Squirrel, painted in Boston in 1765 by the young artist John Singleton Copley. Before doing any research in books or online, the student would first be expected to go to the Museum of Fine Arts, where it hangs, and spend three full hours looking at the painting, noting down his or her evolving observations as well as the questions and speculations that arise from those observations. The time span is explicitly designed to seem excessive. Also crucial to the exercise is the museum or archive setting, which removes the student from his or her everyday surroundings and distractions.

At first many of the students resist being subjected to such a remedial exercise. How can there possibly be three hours’ worth of incident and information on this small surface? How can there possibly be three hours’ worth of things to see and think about in a single work of art? But after doing the assignment, students repeatedly tell me that they have been astonished by the potentials this process unlocked.

It is commonly assumed that vision is immediate. It seems direct, uncomplicated, and instantaneous—which is why it has arguably become the master sense for the delivery of information in the contemporary technological world. But what students learn in a visceral way in this assignment is that in any work of art there are details and orders and relationships that take time to perceive. I did this three-hour exercise myself on this painting in preparation for my own research on Copley. And it took me a long time to see some of the key details that eventually became central to my interpretation and my published work on the painting.

Just a few examples from the first hour of my own experiment: It took me nine minutes to notice that the shape of the boy’s ear precisely echoes that of the ruff along the squirrel’s belly—and that Copley was making some kind of connection between the animal and the human body and the sensory capacities of each. It was 21 minutes before I registered the fact that the fingers holding the chain exactly span the diameter of the water glass beneath them. It took a good 45 minutes before I realized that the seemingly random folds and wrinkles in the background curtain are actually perfect copies of the shapes of the boy’s ear and eye, as if Copley had imagined those sensory organs distributing or imprinting themselves on the surface behind him. And so on.

What this exercise shows students is that just because you have looked at something doesn’t mean that you have seen it. Just because something is available instantly to vision does not mean that it is available instantly to consciousness. Or, in slightly more general terms: access is not synonymous with learning. What turns access into learning is time and strategic patience.

The art historian David Joselit has described paintings as deep reservoirs of temporal experience—“time batteries”—“exorbitant stockpiles” of experience and information. I would suggest that the same holds true for anything a student might want to study at Harvard University—a star, a sonnet, a chromosome. There are infinite depths of information at any point in the students’ education. They just need to take the time to unlock that wealth. And that’s why, for me, this lesson about art, vision, and time goes far beyond art history. It serves as a master lesson in the value of critical attention, patient investigation, and skepticism about immediate surface appearances. I can think of few skills that are more important in academic or civic life in the twenty-first century.

DECELERATION, then, is a productive process, a form of skilled apprehension that can orient students in critical ways to the contemporary world. But I also want to argue that it is an essential skill for the understanding and interpretation of the historical world. Now we’re going to go into the art-history lesson, which is a lesson about the formative powers of delay in world history.

I have chosen Copley’s work to discuss today because it actually has a significant educational resonance. It’s essentially an example of eighteenth-century distance learning. In 1765, Copley was doing very well as the best portrait painter in North America. But he felt stranded in the backwater colony of Boston, thousands of miles away from the nearest art academy. He was clearly a talented painter, but he had been mostly self-taught, and he longed to have a chance to learn from the painting superstars in the academic center of London. So he decided to try to open up a correspondence course of sorts. And to begin that correspondence he painted this picture, packed it up in a crate, walked down to Boston Harbor, put it on a ship, walked back to his studio, and waited to see what kind of feedback he might get about his work from London.

He had to wait a very long time.

It took about a month for the painting to make the crossing to London, and then it was stuck for several weeks in customs, and then it waited a few weeks before it could go on exhibition, and then a friend of Copley’s wrote him a letter conveying some of the things he’d heard the academicians say. He waited a long while to send it, at which point it took almost eight weeks (sailing now against the current) to return to Boston on another ship. All in all, it was about 11 months before Copley was able to open his friend’s letter and learn that painters in London thought his work was generally wonderful but that it suffered from being rather “too liney”—and that Copley might consider correcting that fault. Copley was unsure exactly what that meant, and dispatched another letter asking his friend to inquire further into the matter. This became typical of his long-distance education.

Now, the people in this room who are experienced in educational-feedback theory are probably horrified. Indeed, in the terms of educational science, this agonizingly slow response pace would be identified, I believe, as “non-formative” feedback. And yet I would like to suggest that slowness is not necessarily “non-formative”—in fact, in the case of this painting, it is thoroughly formative. Let me be clear that I am not arguing that we should wait 11 months to return papers. I’m talking in a more general way about the need to understand that delays are not just inert obstacles preventing productivity. Delays can themselves be productive.

We can see this directly in the painting, which is full of allusions to time, distance, and patience. The painting is about its own patient passage through time and space. Look at that squirrel. As the strange shape of the belly fur indicates, if one takes time to notice it, this is not just any squirrel but a flying squirrel, a species native to North America with obvious thematic resonances for the theme of travel and movement. (The work’s full title is A Boy with a Flying Squirrel.) Moreover, squirrels in painting and literature were commonly understood to be emblems of diligence and patience. Then: the glass of water and the hand. Across his long career, this is the only glass of water that Copley ever included in a painting. Why? Well, for one thing, this motif evokes the passage of a sensory chain across a body of water and thereby presents in microcosm the plight or task of the painting itself. Or think about the profile format of the portrait—unusual for Copley. It turns out that in the eighteenth century, the profile format was very strongly associated with persistence in time and space. Where was one most likely to see a profile? On a coin. What is a coin? In essence, a coin is a tool for transmitting value through space and time in the most stable possible way. Coins are technologies for spanning time and distance, and Copley borrows from these associations for a painting that attempts to do the same thing.

Copley’s painting, in other words, is an embodiment of the delays that it was created to endure. If Copley had had instant access to his instructors in London, if there had been an edX course given by the Royal Academy, he would not have been compelled to paint the way he did. Changing the pace of the exchange would have changed the form and content of the exchange. This particular painting simply would not exist. This painting is formed out of delay, not in spite of it.

And this is actually a lesson with much wider implications for anyone involved in the teaching or learning of history. In the thousands of years of human history that predated our current moment of instantaneous communication, the very fabric of human understanding was woven to some extent out of delay, belatedness, waiting. All objects were made of slow time in the way that Copley’s painting concretizes its own situation of delay. I think that if we want to teach history responsibly, we need to give students an opportunity to understand the formative values of time and delay. The teaching of history has long been understood as teaching students to imagine other times; now, it also requires that they understand different temporalities. So time is not just a negative space, a passive intermission to be overcome. It is a productive or formative force in itself.

GIVEN ALL THIS, I want to conclude with some thoughts about teaching patience as a strategy. The deliberate engagement of delay should itself be a primary skill that we teach to students. It’s a very old idea that patience leads to skill, of course—but it seems urgent now that we go further than this and think about patience itself as the skill to be learned. Granted—patience might be a pretty hard sell as an educational deliverable. It sounds nostalgic and gratuitously traditional. But I would argue that as the shape of time has changed around it, the meaning of patience today has reversed itself from its original connotations. The virtue of patience was originally associated with forbearance or sufferance. It was about conforming oneself to the need to wait for things. But now that, generally, one need not wait for things, patience becomes an active and positive cognitive state. Where patience once indicated a lack of control, now it is a form of control over the tempo of contemporary life that otherwise controls us. Patience no longer connotes disempowerment—perhaps now patience is power.

If “patience” sounds too old-fashioned, let’s call it “time management” or “temporal intelligence” or “massive temporal distortion engineering.” Either way, an awareness of time and patience as a productive medium of learning is something that I feel is urgent to model for—and expect of—my students.

Related articles

Scientists look inside the works of great artists

Scientists look inside the works of great artists

September 22, 2015

The Music Practice Board Game

August 28, 2015

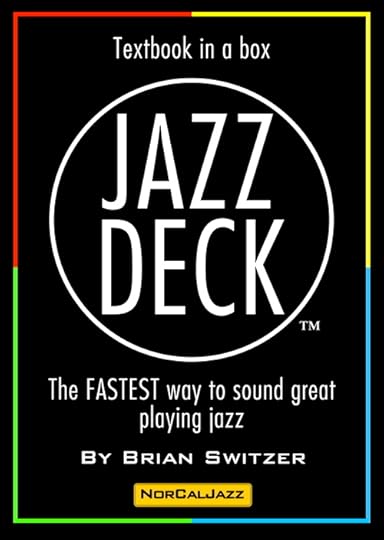

Playing With a Full Deck: If You’re a Jazz Learner, You NEED This Tool

I’ve been playing jazz for, well, for more decades than I can believe. I’m still practicing, still learning.

When starting out, the Jazz Deck would have blown my mind and given me a jump start like none other because it’s simple and super-easy to use.

Today, it blows my mind because of its ability to pack a ton of information into a simple package with eye-catching design. It’s pure genius. Saw it and ordered one immediately. You can, too. Right here.

Jazz Deck is the mind-child of jazz musician, educator, and trumpeter Brian Switzer. I’ll let him tell you about it. There are lots more useful videos on his site here.

_____________________________________________________________

And here’s an example using the cards to solo over the minor 7 chord that opens All the Things You Are:

_____________________________________________________________

A side note on practice (pun intended)

The 2nd video is a superb example of how great practicers isolate ONE idea and work it thoroughly. It’s one chord in a 32-bar song form! But guess what? That minor 7 chord shows up all over the place, so even though you’re focused on one microscopic detail, it relates to MUCH more. You can learn about this trait and many more traits of the best practicers in two of my books, Get Better Faster (less words, more images), and The Practice of Practice (more comprehensive for musicians).

June 12, 2015

The Obstacle IS the Path: Guitarist and Inventor Les Paul

Every setback might be the very thing that makes you carry on and fight all the harder and become that much better. And I’ll probably play until I fall over and that’s the end.

Les Paul in 2005. The legendary guitarist and inventor played until a few months before his death at age 94 in 2009.

Les Paul lived those words. After an injury to his right elbow in a car crash, doctors said they couldn’t rebuild it. So Paul told them to fuse it at a 90-degree angle so he could still play. You can see this in the video below. He had some of his biggest hits after the accident.

It can be tough to own that attitude toward failure. It’s one of the more important, unspoken mindsets about practice that we aren’t often told. The topic of dealing with adversity (and much more) is covered in more detail in The Practice of Practice.

Listen to the brief NPR story about Les Paul.

Here’s the album with Nat King Cole and Les Paul at Carnegie Hall.

A 1966 Merv Griffin Appearance

Related articles

A look back at Les Paul for his 100th birthday

A look back at Les Paul for his 100th birthday Gibson – To Celebrate Les Paul 100th Birthday

Gibson – To Celebrate Les Paul 100th Birthday Les Paul’s 100th Birthday: Anniversary Celebration to Kick Off in Times Square

Les Paul’s 100th Birthday: Anniversary Celebration to Kick Off in Times Square Les Paul anniversary celebration to kick off in Times Square

Les Paul anniversary celebration to kick off in Times Square