Karl Shuker's Blog, page 9

November 30, 2021

MADAGASCAR'S SNAKE-EATING ANTS - FORGOTTEN FABLE, OR FASCINATING FACT?

A worker specimen of Aphaenogaster swammerdami, a Madagascan species of funnel ant (© AntWeb.org/Wikipedia –

CC BY 4.0 licence

)

A worker specimen of Aphaenogaster swammerdami, a Madagascan species of funnel ant (© AntWeb.org/Wikipedia –

CC BY 4.0 licence

) While lately perusing online some 19th-Century back numbers of the Antananarivo Annual and Madagascar Magazine (a yearly periodical that has proved very fruitful in providing me with fascinating but hitherto-obscure, cryptozoologically-unreported material concerning Malagasy mystery beasts of many kinds), I chanced upon a truly bizarre report regarding ants and snakes that as far as I am aware has not been previously blogged about online.

Appearing in this periodical's Christmas 1875 issue, it consisted of the following account, from an article written by Madagascan traveller/clergyman Rev. H.W. Grainge and entitled 'Journal of a visit to Mojanga and the north-west coast':

We also noticed about this part a large number of earthen mounds, varying from one to two and a half feet in height; these were the nest of a large ant credited by the men with uncommon sagacity. We were told that they make regular snake traps in the lower part of these nests; easy enough for the snake to enter, but impossible for it to get out of. When one is caught the ants are said to treat it with great care, bringing it an abundant and regular supply of food, until it becomes fat enough for their purpose; and then, according to native belief, it is killed and eaten by them.

(Mojanga is nowadays known as Mahajanga, or Majunga in French – Madagascar is a former French colony; these names are applied to a city and administrative district on Madagascar's northwest coast.)

Vintage photograph of wilderness at Mojanga during the early 20thCentury (public domain)

Vintage photograph of wilderness at Mojanga during the early 20thCentury (public domain)

Rev. Grainge's macabre little vignette attracted the attention of a reader named R. Toy, who duly quoted it exactly a year later, in the Christmas 1876 issue of the Antananarivo Annual and Madagascar Magazine, and then appended his own equally interesting firsthand experiences concerning this very curious affair:

It would be interesting if some missionary living in the country would test the reality of this reputed fact by digging open a few of these nests. There is no doubt but that the belief is most universal among the natives. I have been assured most confidently over and over again that it is a fact that snakes are kept and fattened by the ants as above described; and knowing the sagacity of ants, and the care they take in feeding the aphides for the sake of their honey, one would not hastily set aside the statement, so generally accepted by the natives, as devoid of truth.

Needless to say, just because a belief is widely accepted does not necessarily make it true, as the very widely accepted yet wholly fallacious belief in hoop snakes, for instance, readily demonstrates. Equally, however, as noted by Toy, the farming and milking of aphids by ants for their sweet secretions is well documented scientifically. So too is their rearing within their nests of the caterpillars of the large blue Phengaris arion, a Eurasian species of lycaenid butterfly.

Large blue (© PJC&Co/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Large blue (© PJC&Co/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

(Although in this latter instance, the ants are the unsuspecting victims of a lepidopteran version of brood parasitism, with the large blue's caterpillars actually acting as predators after having tricked the ants via morphological and pheromonal mimicry tactics into carrying them inside their nests, then feeding them there; the caterpillars also take the opportunity to prey upon the ants' own pupae).

Even so, it is an immense step up, behaviourally speaking, from ants feeding 'cuckoo' caterpillars that they have been tricked into bringing inside their nests to ants purposefully trapping snakes inside their nests, then fattening them up, before killing them specifically to devour them. Such a highly advanced strategy has no readily apparent, direct parallels elsewhere in the ant, or indeed in the entire insect, world – or does it? Read on.

In August 2019, a trio of Japanese researchers who included Teppei Jono published a fascinating Royal Society Open Science paper (click hereto access it) revealing two very different but closely interacting relationships between a species of Madagascan myrmicine ant Aphaenogaster swammerdami and two species of snake, all of which was hitherto unsuspected by science and unequivocally novel. The snakes are a large ant-eating blindsnake called Mocquard's worm snake Madatyphlops decorsei, and an even larger ophiophagous (snake-eating) lampropheid called the Malagasy cat-eyed snake Madagascarophis colubrinus(also known locally as the ant mother – see later).

A Madatyphlopsblindsnake or worm snake (© Bernard Dupont/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

A Madatyphlopsblindsnake or worm snake (© Bernard Dupont/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Native to much of the world (sub-Saharan Africa, much of South America, and Antarctica being the only major exceptions), there are approximately 200 species of Aphaenogasterant, which belong to the taxonomic subfamily Myrmicinae, and produce just a single caste of worker. They are famous for their large funnel-shaped nests (more about which later), earning them the common name of funnel ants. In Madagascar, a major predator of these ants is Mocquard's worm snake Madatyphlops decorsei, endemic to this mini-island continent, and formally described by French herpetologist Dr François Mocquard in 1901, who named it in honour of Gaston-Jules Decorse, a French army physician.

Mocquard assigned this newly-revealed species to the nominate blindsnake genus Typhlops, where it remained until 2014 when a new genus, Madatyphlops, was specifically created for the blindsnakes of Madagascar and the Comoros (14 species are currently recognised), and to which it was duly transferred (and of which it is the largest species). Dark shiny grey-brown dorsally, paler ventrally, this species spends its life underground, explaining why it only has vestigial eyes.

As for the Malagasy cat-eyed snake or ant mother Madagascarophis colubrinus, this species is an active predator of Mocquard's worm snake and is a member of the taxonomic family Lampropheidae. The latter was long considered to be merely a subfamily of Colubridae, but was elevated to the level of a family in its own right in 2010 when a molecular-based study revealed that in reality its member species were more closely allied to the elapids than to the colubrids. Very variable in colour and markings, M. colubrinus is one of five species housed within its genus, endemic to Madagascar, and all are mildly venomous, but they are capable of constriction too if their venom proves insufficient to subdue their prey. This consists of other small reptiles, including snakes as already noted, plus rodents. They have large eyes with vertical, superficially cat-like pupils, hence their common name.

Malagasy cat-eyed snake Madagascarophis colubrinus, aka the ant mother (© Dawson/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)

Malagasy cat-eyed snake Madagascarophis colubrinus, aka the ant mother (© Dawson/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)

According to a publicity release issued on Scimex when the Japanese team's August 2019 paper was published (click here to access it):

A Madagascan ant species can tell whether marauding snakes are friend or foe. When ant-eating blind snakes approach an ant nest, the worker ants run back to evacuate their young, leaving a few behind to mount a biting attack on the intruder. But they also have a second line of defence. The ants allow one of the few known predators of the blindsnake - a snake-eating snake - into their nest, in what the authors say is a symbiotic relationship where the ants get protection and the snake gets a cosy place to hide. Instead of biting the snake-eating snake when it approaches, the ants touch them with their antenna - a well-known form of communication between ants.

In the past, differences in reactions by ants to other species had only occurred relative to different insect predators or aggressors. Consequently, as noted by University of York researcher Dr Eleanor Drinkwater in a Naked Scientistswebsite interview on 20 August 2019 concerning this study by Jono et al., the latter might be the first study to show that ants react differently to different vertebrate predators too. When the researchers conducted experiments to determine the ants' reactions to these snakes, presenting to various nests of this ant species a specimen of each of the two snakes plus one of a third, control snake species, the ants ignored the ant mother snake, but attacked the blindsnake and also the control snake. However, the only snake that sent the ants fleeing back inside their nest to evacuate it was the blindsnake.

Another worker specimen of Aphaenogaster swammerdami (© AntWeb.org/Wikipedia –

CC BY 4.0 licence

)

Another worker specimen of Aphaenogaster swammerdami (© AntWeb.org/Wikipedia –

CC BY 4.0 licence

)

Reading this remarkable discovery has made me wonder whether it may have influenced the native Madagascan belief in ants trapping, fattening up, and then killing snakes. After all, the reason why the local tribespeople refer to M. colubrinusas the ant mother is that they are well aware of its frequent presence around the nests of this particular species of ant, and that it preys upon the blindsnakes preying upon the ants, thereby indirectly protecting the ants.

Also, the nests of some Aphaenogaster ants are both funnel-shaped and deep, conceivably giving a false impression that they have been specially created as inescapable traps for snaring creatures. (Having said that, it is possible that in certain Australian Aphaenogasterspecies, their nests' funnel-shaped entrances do act as traps for surface foraging arthropods.)

Could it be, therefore, that the Madagascan locals knew of the ants' different specific reactions to these two snakes too, long before the researchers scientifically revealed them recently, but that down through many generations of verbal retellings the true nature of these reactions and also of their nests had become distorted and elaborated upon, eventually yielding an imaginative but wholly incorrect scenario whereby the ants do not merely attack the blindsnakes but actually trap, feed, and then feed upon them?

A predominantly black specimen of the Malagasy cat snake (© Bernard Dupont/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

A predominantly black specimen of the Malagasy cat snake (© Bernard Dupont/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

After all, it wouldn't be the first time that garbled, orally-transmitted recollections of elusive animals and unusual animal behaviour by non-scientific observers has resulted in the evolution of memorable yet entirely erroneous folk beliefs.

Finally: after discovering the two above-quoted reports in two successive early volumes of the Antananarivo Annual and Madagascar Magazine, I painstakingly checked through every succeeding volume of it, and also widely elsewhere online, but I have been unable to uncover any additional reports on this most curious subject.

Consequently, it presently remains a herpetological enigma – unless anyone reading this ShukerNature blog article of mine has further information? If so, I'd love to hear from you!

Madagascar's ophidian ant mother Madagascarophis colubrinus (© Axel Strauss/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Madagascar's ophidian ant mother Madagascarophis colubrinus (© Axel Strauss/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

November 19, 2021

THE ISLE OF WIGHT MEGA-FOOTPRINTS – A CAUTIONARY CRYPTOZOOLOGICAL TALE

My cast of one of the set of Isle of Wight mega-sized animal footprints from April 1994 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My cast of one of the set of Isle of Wight mega-sized animal footprints from April 1994 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Here's a cautionary little tale for cryptozoology that I included during a lecture presented by me on modern-day mystery beast reports at the very first Fortean Times UnConvention, held in London during 18-19 June 1994. However, I've never previously documented it anywhere online – so it's high time that I did.

In April 1994, naturalist Martin Trippett from the Isle of Wight (a large island situated off southern England) informed me that a garden in the IOW town of Ride had recently received an unusual visitor. The garden had been freshly dug on the day in question by its owners, who then placed their garden rubbish in some bin-liners. The garden was completely enclosed by a 3-ft-high wall and its only entrance was via a gate, which they locked that night.

The next morning, they found that some unidentified animal had been in their garden, ripping the bin liners to shreds and leaving huge footprints all over the freshly dug soil. The photograph opening this present ShukerNature article is of a cast of one set of those prints (later described to me over the phone by some IOW newspaper reporters), which Martin very kindly posted to me for my examination and permanent retention.

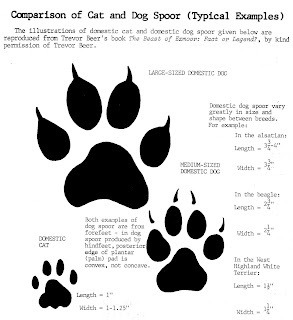

Diagrams comparing dog and cat spoor – typical examples (click to enlarge for reading purposes) (© Trevor Beer

– reproduced with his kind permission in my 1989 book Mystery Cats of the World and in its updated 2020 edition Mystery Cats of the World Revisited)

Diagrams comparing dog and cat spoor – typical examples (click to enlarge for reading purposes) (© Trevor Beer

– reproduced with his kind permission in my 1989 book Mystery Cats of the World and in its updated 2020 edition Mystery Cats of the World Revisited)

Measuring 4.5 in long and 4 in across, the prints had no claw marks at all, which ostensibly leaned towards a huge cat as an identity. However, when the casts were sent to me, I could see from the shape of the heel pad and the diverging placement of the toe pads that they were in fact dog prints, albeit from a very large and extremely well-manicured dog – so this is what I told the reporters.

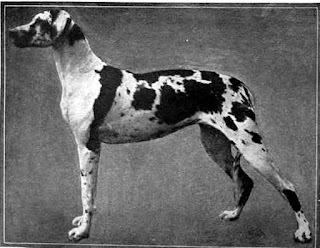

Inevitably, they were rather disappointed, as this dashed any hopes for them of dramatic headlines concerning giant cats on the loose. Nevertheless, they then confessed to me that they had actually been informed by the police that a Great Dane dog had been loose in this particular area for the past week, a huge breed that could very easily scale a 3-ft-high wall if it so chose (more details here).

All of which proves that however tempted you may be to give the media the story that it wants, regardless of your own personal opinion, it is not a good idea to do so. Cryptozoology has a nasty knack of coming back to haunt those who flirt with its favours.

Vintage photograph from 1910 of a Harlequin Great Dane (public domain)

Vintage photograph from 1910 of a Harlequin Great Dane (public domain)

October 17, 2021

A LIKING FOR THE (MISNAMED) LAKE OF ALLIGATORS

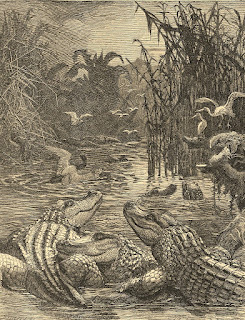

Vintage engraving depicting a lake of crocodiles (public domain)

Vintage engraving depicting a lake of crocodiles (public domain) What's in a name? Not a lot, sometimes. Or, to put it more poetically: the naming of books – and animals – is a difficult matter, it isn't just one of your holiday games, as T.S. Eliot almost said.

Take, for instance, a book written by English diplomat, Conservative MP, and Oriental scholar Edward Backhouse Eastwick (1814-1883), published in 1849, and entitled Dry Leaves From Young Egypt. With a title like that, one might well be forgiven for assuming it to be a volume devoted to the land of the pyramids and sphinx, but in reality its subject is the author's journey in 1839 through Sindh, the most southeasterly of Pakistan's four provinces. Similarly, a section within this same book entitled 'Magar Taláo – the Alligator Lake' is not about alligators at all, which are not native to Pakistan, but concerns crocodile instead, which are native here.

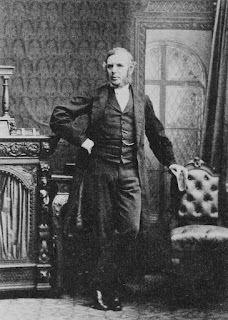

A 19th-Century painting (artist unknown to me) of Edward Backhouse Eastwick (public domain)

A 19th-Century painting (artist unknown to me) of Edward Backhouse Eastwick (public domain)

I first learned about Magar Taláo about 30 years ago, from a thoroughly fascinating, exquisitely illustrated compendium volume from 1885 entitled The World of Wonders: A Record of Things Wonderful in Nature, Science, and Art that I'd recently purchased at a book fair, and which was packed with the most intriguing, unusual, and sometimes truly bizarre subjects, often excerpted from earlier works that nowadays are all but forgotten. In the case of Magar Taláo, this compendium's coverage consisted of what turned out upon my later checking of it to be a direct quote of the entire relevant passage from Eastwick's afore-mentioned book.

Moreover, as it is such an interesting but nowadays rarely read passage, I have decided to do the same with it here on ShukerNature, because I feel sure that it will interest my blog's readers just as much as it did with me when I first read it all those years ago in The World of Wonders, and then subsequently re-read it in its original source. So here it is, quoted in full directly from Eastwick's Dry Leaves From Young Egypt(but please bear in mind that the so-called alligators referred to in it are actually crocodiles, and that it is set in Pakistan, not Egypt!):

One of my first expeditions after reaching Caráchi [Karachi] was a visit to the Magar Taláo, as it is called, or Lake of Alligators. This curious place is about eight miles from Caráchi. and is well worth inspecting to all who are fond of the monstrous and grotesque. A moderate ride through a sandy and sterile track varied with a few patches of jungle, brings one to a grove of tamarind trees, hid in the bosom of which lie the grisly brood of monsters. Little would one ignorant of the locale suspect that under that green wood in that tiny pool, which an active leaper could half spring across, such hideous denizens are concealed. "Here is the pool," I said to my guide rather contemptuously, "but where are the alligators?" At the same time I was stalking on very boldly with head erect, and rather inclined to flout the whole affair, naso adunco. A sudden hoarse roar or bark, however, under my very feet, made me execute a pirouette in the air with extraordinary adroitness, and perhaps with more animation than grace. I had almost stepped on a young crocodilian imp about three feet long, whose bite, small as he was, would have been the reverse of pleasant. Presently the genius of the place made his appearance in the shape of a wizard-looking old Fakir, who, on my presenting him with a couple of rupees, produced his wand — in other words, a long pole, and then proceeded to "call up his spirits." On his shouting "Ao! Ao!" "Come! Come!" two or three times, the water suddenly became alive with monsters. At least three score huge alligators, some of them fifteen feet in length, made their appearance, and came thronging to the shore. The whole scene reminded me of fairy tales. The solitary wood, the pool with its strange inmates, the Fakir's lonely hut on the hill side, the Fakir himself, tall, swart, and gaunt, the robber-looking Bilúchi by my side, made up a fantastic picture. Strange, too, the control our showman displayed over his "Lions." On his motioning with the pole they stopped (indeed, they had already arrived at a disagreeable propinquity), and, on his calling out "Baitho," "Sit down," they lay flat on their stomachs, grinning horrible obedience with their open and expectant jaws. Some large pieces of flesh were thrown to them, to get which they struggled, writhed, and fought, and tore the flesh into shreds and gobbets. I was amused with the respect the smaller ones shewed to their overgrown seniors. One fellow, about ten feet long, was walking up to the feeding ground from the water, when he caught a glimpse of another much larger just behind him. It was odd to see the frightened look with which he sidled out of the way evidently expecting to lose half a yard of his tail before he could effect his retreat. At a short distance (perhaps half a mile) from the first pool, I was shewn another, in which the water was as warm as one could bear it for complete immersion, yet even here I saw some small alligators. The Fakirs told me these brutes were very numerous in the river about fifteen or twenty miles to the west. The monarch of the place, an enormous alligator, to which the Fakir had given the name of "Mor Saheb," "My Lord Mor," never obeyed the call to come out. As I walked round the pool I was shewn where he lay, with his head above water, immoveable as a log, and for which I should have mistaken him but for his small savage eyes, which glittered so that they seemed to emit sparks. He was, the Fakir said, very fierce and dangerous, and at least twenty feet in length.

What a fascinating if frightening vista the Lake of Alligators must have been to the previously imperious, unimpressed Eastwick, and, echoing his own viewpoint afterwards, how surreal a scene it must have seemed – the product of some fevered nightmare, no less – featuring a primeval phantasmagorical world bedeviled by the deadliest of dragons who remain lulled only by the spellbinding skills of the almost mystical, magical fakir in their midst, a veritable crocodile whisperer, in fact!

Finally, for everyone reading this blog article of mine who shares my passion for titillating trivia: the first recorded use in English of the Arabic word 'kismet', meaning destiny, fate, or simply luck, was by none other than a certain Edward Backhouse Eastwick (who spelled it 'kismat'), in – yes, you've guessed it – Dry Leaves From Young Egypt. There's a future quiz question lurking in there somewhere!

A congregation of pool-dwelling crocodiles (public domain)

A congregation of pool-dwelling crocodiles (public domain)

October 15, 2021

HOW TO LOSE A CHIMAERA, IN ONE EASY LESSON!

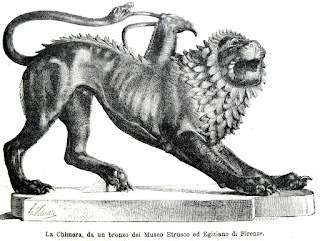

Vintage picture postcard depicting the famous Chimaera of Arezzo bronze statue; it was originally part of a group, with Bellerophon and Pegasus fighting it (public domain)

Vintage picture postcard depicting the famous Chimaera of Arezzo bronze statue; it was originally part of a group, with Bellerophon and Pegasus fighting it (public domain) How to lose a chimaera in one easy lesson? Simply see it, then promptly forget all about it, until far too much time has passed to make amends. See, I told you that it was easy! Confused? I was too, for a while – but let's begin at the beginning.

The year was 1980-ish, sometime in that decade anyway. It was during an afternoon in the Midlands town of Stratford-upon-Avon, famous not only in England but also internationally as the birthplace of a certain playwright, one William Shakespeare, to be precise. I was there with my family, as this was a favourite visiting locale for us on Sundays, because unlike in many other English towns back then, most shops in Stratford were open on the Sabbath due its huge popularity with overseas tourists.

Chimaera fountain at Arezzo, vintage postcard, 1952 (public domain)

Chimaera fountain at Arezzo, vintage postcard, 1952 (public domain)

And so it was on that fateful afternoon that I found myself in a large two-storey shopping complex in the centre of Stratford's shopping area, a complex that specialized in antiques. Its very spacious interior was divided up into numerous stalls, each stall rented out to a different antiques seller, so it collectively offered a vast range of objets d'art, curiosities, and exotica of every conceivable kind – in other words, a fascinating place in which to spend time browsing, at least for anyone like me with a decidedly eclectic range of interests.

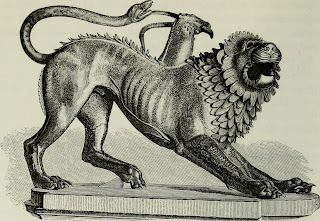

In one corner of the downstairs storey was a stall whose lady vendor could usually be found whiling away the hours by knitting as potential purchasers eyed her wares. I can still vividly recall spotting on the floor amidst some other figurines a Jack Russell terrier-sized black sculpture in metal of what seemed to me to be a somewhat odd-looking lion, with a spiky mane, unusually slender haunches, and a long tail that curved up over its back instead of downwards. There also seemed to be something peculiar sticking up from its shoulders, but as I wasn't overly interested in this ostensibly misshaped, confusing creature, I never bothered to peer closer to see what that 'something peculiar' was. Instead, my gaze fell elsewhere, peering at other items in her stall before moving on to various stalls nearby – this complex contained a great many stalls, so in order to visit all or most of them, it paid not to linger or loiter too long at any single one.

An inordinately elaborate chimaera, by Jacopo Ligozzi, created between 1590 and 1610 AD (public domain)

An inordinately elaborate chimaera, by Jacopo Ligozzi, created between 1590 and 1610 AD (public domain)

I thought nothing more of that strange-looking leonine statue for a long time, some years in fact, until one day I was idly flicking through a Larousse-published encyclopaedia of art that I'd lately purchased, and there, to my great surprise, was a photograph of a statue that looked exactly like the odd, spiky-maned lion that I'd seen during that long-gone Sunday afternoon visit to Stratford – except that it wasn't a lion after all. Instead, it was a chimaera (=chimera), and no ordinary chimaera either, always assuming of course that any chimaera can ever be considered ordinary. But what exactly IS a chimaera?

If you're unversed in Greek mythology, you may not have encountered the stirring legend of Bellerophon, Pegasus, and the Chimaera, so here are its edited highlights. The hideous semi-human monster Echidna had given birth to a number of horrific beasts, including the three-headed hell hound Cerberus, the two-headed monster hound Orthos, the many-headed Lernaean hydra, and the chimaera, which was yet another multi-headed horror.

An animatronic large-scale model of the chimaera (© Dr Karl Shuker)

An animatronic large-scale model of the chimaera (© Dr Karl Shuker)

This terrifying beast took the form of a huge lion, but unlike any normal member of the leonine pride, the chimaera bore a second head, in the form of a horned goat's, sprouting forth from between its shoulders or its upper back (recollections may vary, as I believe someone once said recently…?), and a third head, in the form of a venomous snake's, at the end of its long, ever-thrashing tail. Moreover, as if all of that were not already more than sufficiently deadly for anyone to deal with, the chimaera also breathed fire, jetting forth great flames of destruction from the jaws of its primary, leonine head.

In other words, this was an exceptionslly formidable beast for anyone to contend with, but most especially for the poor benighted inhabitants of Caria in northern Anatolia, Turkey – because this is where the chimaera had taken up residence and was terrorizing the helpless populace, who had no answer to the perilous threat posed by an enormous monstrosity with three different heads and infernal flame-throwing capabilities.

Two vintage engravings of the Chimaera of Arezzo bronze statue (top and bottom); and a vintage b/w photograph of it (middle) – note the dedicatory inscription to the god Tinia carved upon its right foreleg (all public domain)

Two vintage engravings of the Chimaera of Arezzo bronze statue (top and bottom); and a vintage b/w photograph of it (middle) – note the dedicatory inscription to the god Tinia carved upon its right foreleg (all public domain) In such a dire situation, the usual plan of action is for the terrified locals to send out for a hero to dispatch their hideous persecutor, but in this instance they did not have to do so, because just such a man had already been sent there, by his scheming uncle, King Iobates of Lycia in Anatolia, who fervently hoped that his heroic nephew would be killed by the chimaera, thereby foiling a prophecy claiming that his nephew would kill him instead.

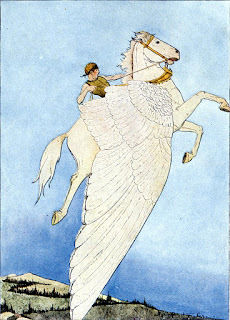

The nephew in question was a mighty, fearless warrior-hero named Bellerophon, who arrived in Caria astride his equally mighty, fearless steed. Nor was this just any mighty, fearless steed either – in fact, it was none other than the magnificent winged horse Pegasus, previously untamed, but whom Bellerophon had successfully captured using the goddess Athena's enchanted golden bridle while it was drinking from a sacred spring on the citadel of Corinth in Greece, unaware of Bellerophon's stealthy approach.

Bellerophon on Pegasus slaying the chimaera – from Walter Crane's A Wonder Book For Girls and Boys (public domain)

Bellerophon on Pegasus slaying the chimaera – from Walter Crane's A Wonder Book For Girls and Boys (public domain)

Riding Pegasus, Bellerophon swiftly entered into battle with the chimaera, but even though his winged steed possessed the significant advantage of flight, it was a long and physically grueling onslaught before Bellerophon and Pegasus finally wore down this immensely powerful monster's vast reserves of strength. Doing so, however, finally enabled Bellerophon to slay it, by firing a spear tipped with a block of lead down its throat, whose fire melted the lead, thereby suffocating the chimaera, and freeing the people of Caria from its tyranny forever.

Encouraged by his great success, Bellerophon then decided to attempt an even more daring feat – to fly up through the sky upon Pegasus until he reached the very home of the gods themselves, who had hitherto remained forever concealed from human eyes in their lofty cloud-shielded domain at the very summit of Mount Olympus. This was something that no mortal had ever even attempted before, let alone achieved, but Bellerophon was intent upon doing so, and promptly set off, riding Pegasus ever upwards towards the divine dwelling place of the Greek deities.

An exquisite illustration from 1914 of Bellerophon riding Pegasus (public domain)

An exquisite illustration from 1914 of Bellerophon riding Pegasus (public domain)

Zeus, however, was far from pleased about this. He had watched with pleasure as Bellerophon had dispatched the dreaded chimaera, but now his brow was creased with fury, his eyes thunderous with rage, as he witnessed Bellerophon's blasphemous ascent through the skies towards their rarefied Olympian home. Suddenly, Zeus had an idea – he sent forth a biting gadfly, down towards Bellerophon and his winged steed. When it reached them, the gadfly savagely bit Pegasus on his rump – which caused him to rear up in shock and pain, throwing an unsuspecting Bellerophon off his back, who plummeted headlong back down to Earth.

Miraculously, however, Bellerophon survived, by landing on a thorn bush that cushioned his fall, but its thorns blinded him, and he spent the rest of his days wandering the land piteously like a beggar, in abject misery – a sorry end indeed for a former hero and slayer of monsters.

Modern-day photographs depicting both sides of the Chimaera of Arezzo bronze statue (public domain / Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0 licence )

Back now to my afore-mentioned Larousse-published encyclopaedia of art, and the photograph that I had seen in it was of a bronze statue of the chimaera, which had been unearthed by construction workers on 15 November 1553 at Arezzo, an ancient Etruscan and Roman city in Tuscany, Italy, and which dated back to approximately 400 BC.

Nowadays known officially as the Chimaera of Arezzo, and widely deemed to be the finest example ever uncovered of ancient Etruscan artwork, this spectacular statue is believed to have been a votive offering to the sky god Tinia – the supreme deity in Etruscan mythology. It stands 78.5 cm (2.5 ft) high, measures 129 cm (4.25 ft) in total length, and after passing through several different owners and holding locations it has been on permanent display at Florence's National Archaeological Museum in Tuscany since 1870.

Apart from its bright red colour, this is an identical replica of the Chimaera of Arezzo bronze statue, and was cast by the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry (© Piero Paoletti/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Apart from its bright red colour, this is an identical replica of the Chimaera of Arezzo bronze statue, and was cast by the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry (© Piero Paoletti/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Modern outdoor chimaera statue in stone inspired by the Chimaera of Arezzo bronze statue (

© Thomas Shahan/Wikipedia

– CC BY 2.0 licence)

Modern outdoor chimaera statue in stone inspired by the Chimaera of Arezzo bronze statue (

© Thomas Shahan/Wikipedia

– CC BY 2.0 licence)

I now realized that what I had seen in that antiques stall at Stratford was a modern-day replica of this historically highly significant statue, a faithful facsimile of the Chimaera of Arezzo no less. Unfortunately, however, I hadn't realized back then what it was, so I hadn't thought to ask its price. True, the price may have been more than I could have afforded, but I’ll never know, because I never asked.

All that I do know is that in the 30-40 years that have passed since that monumental miss on my part, I have never once seen another contemporary reproduction of the Chimaera of Arezzo statue for sale, anywhere. But I live in hope…

My mother Mary Shuker and I being scrutinized by an animatronic chimaera at an exhibition of monsters held in Birmingham's art gallery during August 2008 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My mother Mary Shuker and I being scrutinized by an animatronic chimaera at an exhibition of monsters held in Birmingham's art gallery during August 2008 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Finally: The 2012 fantasy movie Wrath of the Titans, albeit playing fast and loose with classical Greek mythology as is Hollywod's wont, contains an undeniably thrilling battle sequence between Perseus (as opposed to Bellerophon) and a winged chimaera - check out its sneaky serpentine tail in the following video clip:

October 13, 2021

MYSTERY BEASTS SERVED UP ON A PLATE, GREEK STYLE!

My newly-purchased modern-day Greek wall plate featuring some very mysterious creatures depicted upon it – please click photograph to enlarge it for close-up viewing purposes (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My newly-purchased modern-day Greek wall plate featuring some very mysterious creatures depicted upon it – please click photograph to enlarge it for close-up viewing purposes (© Dr Karl Shuker) On Tuesdays and Fridays, the (very) small outdoor market in my West Midlands, England, home town is largely devoted to bric-a-brac and collector's stalls, selling all manner of curiosities and exotica amidst the more traditional DVDs, stamps, books, medals, toys, records, ornaments, and suchlike – so naturally I'm a frequent visitor!

Yesterday, the very first stall that I walked up to included among its varied array of objects for sale the large and very ornately decorated terracotta Greek wall plate whose photograph opens this present ShukerNature article. Although only a modern-day creation, unsigned and unstamped, its sizeable 11-inch diameter coupled with its striking portrayal of several different animals in classical Greek style rendered this exquisite wall plate an extremely eyecatching item of artwork very worthy of being displayed, and its previous owner had evidently thought so too, because a wall-hanger frame was still attached to its reverse side.

What attracted me to this plate most of all, however, was the precise nature of the animals depicted upon it, because whereas some were readily identifiable, others were much more mysterious. Consequently, I decided to ask its price, although I strongly suspected that such a beautiful object, especially one that was in excellent condition too, would not be cheap. When I asked the seller, a look of intense concentration immediately fixed itself upon his face, and he proceeded to stand there for several moments, in deep, rapt contemplation. How much would he decide to ask for it, I wondered - £5, £10, possibly even more? After what seemed like an eternity, the seller finally reached a decision and turned slowly towards me, as I awaited with quiet dread the size of the figure that he was about to quote me.

"20p," he said.

Never had a 20p coin ever exited anyone's pocket and found itself in someone else's hand as rapidly as did the 20p coin that I used to purchase this absolute bargain!

Picking up the surprisingly heavy but thoroughly wonderful wall plate that was now mine, all mine, I placed it gingerly inside a plastic carrier bag and then that inside another one, to ensure that nothing else that I may purchase there would knock against it and possibly chip its beautiful surface, and then I walked happily away, another item of potential cryptozoological interest to add to my collection.

When I arrived back home, I unwrapped the plate and spent some time perusing its portrayed beasts. First and foremost to attract my attention was the gorgeously-detailed fabulous beast depicted at its centre, which I readily recognized to be a Greek sphinx, combining a lion's body with a woman's head, and winged. Egyptian sphinxes, conversely, combine a lion's body with a man's head, and are not winged.

Close-up of the Greek sphinx depicted at the centre of my Greek wall plate (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Close-up of the Greek sphinx depicted at the centre of my Greek wall plate (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Turning now to the various beasts decorating the plate's perimeter, I could see straight away that two of them were a pair of maned lions, depicted near to bottom-left and bottom-right of the plate:

The two maned lions depicted on my Greek wall plate (© Dr Karl Shuker)

The two maned lions depicted on my Greek wall plate (© Dr Karl Shuker)

This left four other creatures still to identify, and this is where it became rather more difficult, at least initially. Three of these – positioned bottom-centre, near top-left and near top-right – were depictions of a very distinctive, unusual type of bird. It sported a long swan-like or goose-like neck, but its plumage's form and colouration did not match that of any swan or goose native to either Greece or its environs that I could think of. And yet it did seem strangely familiar somehow.

The three mystery birds depicted on my Greek wall plate (© Dr Karl Shuker)

The three mystery birds depicted on my Greek wall plate (© Dr Karl Shuker)

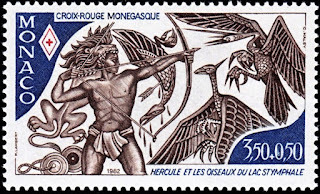

After giving the matter some thought, I then gave thanks to the fact that I was not only a lover of classical mythology but also a stamp collector, because an image had suddenly popped into my mind – the image of one specific postage stamp featuring the classical Greek demi-god hero Heracles (aka Hercules) battling a flock of avian man-eaters known as the Stymphalian birds (click here to access my detailed investigation of these creatures elsewhere on ShukerNature).

In 1982, Monaco had commemorated the famous Greek legend of Heracles by issuing a series of postage stamps that each illustrated one of his twelve great labours. And among those labours was his slaying of the ferocious lake-dwelling Stymphalian birds, which reputedly possessed long necks and huge wings of brass. Moreover, the three birds depicted on that particular stamp definitely bore a marked resemblance to the tantalizing trio portrayed upon my Greek wall plate.

The Monaco postage stamp depicting Heracles fighting the Stymphalian birds (© Monaco Postal Service – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

The Monaco postage stamp depicting Heracles fighting the Stymphalian birds (© Monaco Postal Service – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Consequently, although I cannot be absolutely certain, it seems reasonable to assume that my plate's mystery birds are indeed representations of these mythological feathered monsters. Indeed; the plate's modern-day Greek artist may even have been directly inspired by that particular Greek-themed Monaco stamp when designing his birds for it.

All that now awaited my attention and attempts to identify it was the very intriguing animal portrayed at top-centre on my plate. Looking closely at it, I felt that it most closely resembled some form of big cat. Unquestionably, its face, body shape, and paws were all decidedly feline, but if so, which cat could it be?

For whereas the creature's chest was very noticeably spotted, like that of a leopard, its tail was just as noticeably tufted, like that of a lion. Yet it did not possess a mane like the instantly recognisable pair of lions portrayed elsewhere on the plate both sported. Perhaps it was meant to be a lioness rather than a lion, but if so, why was its chest spotted? Equally, why only its chest, why not the remainder of its body as well, which is what you would expect if, tufted tail notwithstanding, it was intended to be a representation of a leopard? All very mystifying.

And a day later it remains very mystifying, because despite having given the matter much thought during the interim period between then and now, I am still unable to offer a plausible identity for this semi-mottled mystery beast. Perhaps it was simply an invention of the artist, a fictitious entity playfully added to the plate's panoply of authentic classical Greek fauna from reality and mythology (back in early times, lions did exist here). Alternatively, might it even be an attempt by him to portray a leopon, a hybrid of lion and leopard? Or could it be some fabled Greek beast unfamiliar to me? I shall continue to investigate this pictured puzzle, but if any ShukerNature reader can offer me any suggestions of their own, I'd greatly welcome receiving them.

The unidentified mystery beast depicted on my Greek wall plate, ostensibly combining morphological features of the lion and the leopard (© Dr Karl Shuker)

The unidentified mystery beast depicted on my Greek wall plate, ostensibly combining morphological features of the lion and the leopard (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Finally: this particular example is one of several modern-day Greek wall plates decorated with exquisite depictions of mythological beasts and deities that I have purchased down through the years at various bric-a-brac markets and car boot sales.

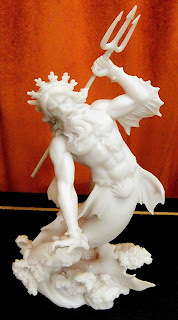

I recently featured one of them, depicting a famous statue portraying the horrific death of the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons at the jaws and coils of a pair of giant snakes sent forth from the sea by Poseidon, in a ShukerNature article of mine examining this famous Greek/Trojan legend (click here to access it). Here it is again:

Modern-day Greek wall plate depicting the famous statue 'Laocoön and His Sons' (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Modern-day Greek wall plate depicting the famous statue 'Laocoön and His Sons' (© Dr Karl Shuker)

And below are some of the others:

Modern-day Greek wall plate depicting a pair of beautiful winged steeds pulling the sun chariot of Apollo across the sky (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Modern-day Greek wall plate depicting a pair of beautiful winged steeds pulling the sun chariot of Apollo across the sky (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Modern-day Greek wall plate depicting the slaying of the minotaur by Theseus (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Modern-day Greek wall plate depicting the slaying of the minotaur by Theseus (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Modern-day Greek wall plate depicting Odysseus bound to the mast of his ship to prevent him from being lured to his death by the deadly singing of the three sirens surrounding the vessel (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Modern-day Greek wall plate depicting Odysseus bound to the mast of his ship to prevent him from being lured to his death by the deadly singing of the three sirens surrounding the vessel (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Modern-day Greek wall plate depicting Hermes, Artemis, and Apollo, with one of Artemis's sacred deer beside her (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Modern-day Greek wall plate depicting Hermes, Artemis, and Apollo, with one of Artemis's sacred deer beside her (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Modern-day Greek wall plate depicting Zeus, Hera, and Nike (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Modern-day Greek wall plate depicting Zeus, Hera, and Nike (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Lastly, just to be different, my resin statuette of the Greek sea god Poseidon

(© Dr Karl Shuker)

Lastly, just to be different, my resin statuette of the Greek sea god Poseidon

(© Dr Karl Shuker)

October 5, 2021

INVESTIGATING THE BLUE MYSTERY MINI-BIRDS OF GALILEE

An adult male specimen of the blue rock thrush Monticola solitarius (© AquilaGib/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)Nowadays, as a result of long experience in such matters, I am rarely if ever surprised to discover creatures of cryptozoological interest in ostensibly unlikely sources, but even so I am never less than interested by them. Such was the case with the subject of this present ShukerNature blog article, which to my knowledge has never been brought to cryptozoological attention before.

An adult male specimen of the blue rock thrush Monticola solitarius (© AquilaGib/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)Nowadays, as a result of long experience in such matters, I am rarely if ever surprised to discover creatures of cryptozoological interest in ostensibly unlikely sources, but even so I am never less than interested by them. Such was the case with the subject of this present ShukerNature blog article, which to my knowledge has never been brought to cryptozoological attention before. The tantalizingly short but fascinating item – from the 1 September 1866 issue in Vol. 2 of a long-discontinued English periodical entitled Hardwicke's Science-Gossip – recently came to my attention:

BLUE BIRDS OF GALILEE. – In the translation of Renan's "Life of Jesus" (cheap edition), there is mention made at page 74 of "blue birds (at Galilee) so light that they rest on a blade of grass without bending it." Is there a blue bird in that region so small as to afford foundation for the statement, and if so, what is its scientific name? – H.G. [these being the initials of this query's author – their full name was not given]

Named after its publisher, Robert Hardwicke, based in London, Hardwicke's Science-Gossip was published on the first day of each month from 1865 (Vol. 1) to 1893 (Vol. 29), after which it was succeeded by Science-Gossip. Its editors were Mordecai Cubitt Cooke (ed. 1865-1871) and John Ellor Taylor (ed. 1872-1893). Throughout the brief interchange of correspondence concerning these birds that appeared in this periodical's pages, and which will be presented in full below, the editor was Cooke.

A photograph of Ernest Renan, snapped by Antoine Samuel Adam-Salomon (public domain)

A photograph of Ernest Renan, snapped by Antoine Samuel Adam-Salomon (public domain)

First of all, however, a word about the source from which H.B. had quoted the line regarding the blue birds. Published in 1863, the book in question was a very popular work entitled The Life of Jesus, written by French biblical scholar Ernest Renan (1823-1892) after having visited Galilee and Jerusalem during the early 1860s. Hence his account was based upon first-hand knowledge, not merely upon trawling through the writings of others. Whereas he appeared distinctly uninspired by Jerusalem's environs, Renan was greatly enamoured by what he considered to be the natural beauty of Galilee. Here is the full excerpt from his book regarding its wildlife that contained the line about the blue birds that had piqued H.B.'s curiosity:

The saddest country in the world is perhaps the region round about Jerusalem. Galilee, on the contrary, was a very green, shady, smiling district, the true home of the Song of Songs, and the songs of the well-beloved. During the two months of March and April the country forms a carpet of flowers of an incomparable variety of colors. The animals are small and extremely gentle — delicate and lively turtle-doves, blue-birds so light that they rest on a blade of grass without bending it, crested larks which venture almost under the feet of the traveller, little river tortoises with mild and lively eyes, storks with grave and modest mien, which, laying aside all timidity, allow man to come quite near them, and seem almost to invite his approach.

All of the other animal species mentioned in this excerpt are readily identifiable and familiar sights in Galilee, which makes the zoologically unrecognizable blue birds all the more perplexing.

Galilee (© Paulina Zet/Vered Hasharon/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Galilee (© Paulina Zet/Vered Hasharon/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Back now, therefore, to H.G.'s plea for assistance in identifying Renan's feather-light blue mystery mini-birds of Galilee. It was initially answered, albeit exceedingly succinctly, in the 1 November 1866 issue of Hardwicke's Science-Gossip by a correspondent signing off with the initials T.G.P.:

BLUE BIRD OF GALILEE. – H.G. inquires as to this bird, mentioned by Renan. The bird that learned author probably refers to is Cinnaris [sic] osea, the Sun-bird or Honeysucker of Palestine.

This comment was challenged in the 1 December 1866 issue by the memorably-named Lester Lester, of Monkton Wyld (nowadays a small settlement within the civil parish of Wootton Fitzpaine, in the southwest English county of Dorset), who responded somewhat pompously as follows:

THE BLUE BIRD OF GALILEE. – Will T.G.P. allow one who has lately been reading Tristram's "Land of Israel" to suggest that the Blue Bird of Galilee is most probably the Blue Rock-thrush (Petrocincla cyanea), and not the Sun-bird (Cinnaris [sic] osea)? The habitat of this latter bird is the Ghor or deep valley of the Jordan and Dead Sea, most especially about Jericho, and not the rocky hills of Galilee.

T.G.P.'s communication was also responded to in the 1 January 1867 issue of Vol. 3, this time by none other than the Rev. Dr H.B. [Henry Baker] Tristram (1822-1906) himself – the English clergyman/scholar/ornithologist who was the author of the book Land of Israel that Lester had cited (or, to give it its full, correct title, The Land of Israel: A Journal of Travels in Palestine, Undertaken With Special Reference to Its Physical Character, published in 1865).

Rev. Dr H.B. Tristram, photographed in 1908 (public domain)

Rev. Dr H.B. Tristram, photographed in 1908 (public domain)

However, Rev. Dr Tristram was even more emphatic than Lester in his dismissal of T.G.P.'s sunbird suggestion:

THE BLUE BIRD OF GALILEE. – I see that a correspondent in a late number inquired what was "the blue bird of Galilee." I suppose that fancy may be allowed some scope in the question, but as a matter of fact there are but two birds to which it can be applied – the blue Thrush (Petrocincla cyanea) which is scattered about the Galilean hills and glens in small numbers all the year round, and the Roller (Coracias garrula) which is very common over the whole country in summer only. The Sun-bird (Nectarinia osea) is quite out of the question. It is not blue, and it barely exists in Galilee; one or two pairs merely straggling into the neighbourhood of the Lake of Galilee. It is a bird of the Lower Jordan valley and Dead-Sea basin strictly, and even there will only be seen by those who look closely for it.

Beneath this communication was a short square-bracketed addendum provided by the periodical's editor, who at that time was Cooke. As will be seen below, this addendum consists of a summary of a presumably longer response by T.G.P. to Tristram's missive (T.G.P.'s full response was not published, which is a great shame as it would have been most enlightening to discover what further support he offered for his preferred sunbird identity). Here it is:

["T.G.P." writes to us again in support of his opinion that the bird alluded to by Renan, as "so small and light that it can rest on a blade of grass without bending it," must be some such small creature as Cinnyris osea.]

And those were the last words on the subject to appear in Hardwicke's Science-Gossip. For despite my checking methodically through every succeeding volume of its entire run (all but Vol. 1 of which can be found online here, courtesy of the Biodiversity Heritage Library), no further mention of these enigmatic birds was found. Nor have I been able to uncover any details regarding them elsewhere.

Moreover, perusing a comprehensive online checklist of the birds of the Israel/Palestine region provided me with no additional species worthy of consideration. Consequently, I am focusing my attention now upon the trio mentioned in the above-quoted correspondence between T.G.P., Lester, Tristram, and editor Cooke.

Juvenile (top), adult female (centre), and adult male (bottom) of the blue rock thrush Monticola solitarius (public domain)

Juvenile (top), adult female (centre), and adult male (bottom) of the blue rock thrush Monticola solitarius (public domain)

Let’s begin with the blue rock thrush. Nowadays referred to scientifically as Monticola solitarius (Petrocincla cyanea as used by the writers quoted above is now obsolete), this species was traditionally classified as a thrush, but in more recent times it has been recategorised as a chat, and thus assigned to the flycatcher family Muscicapidae. Nevertheless, it retains its long-familiar turdine English name. Moreover, as both its English and its taxonomic names suggest, this is a montane species, and is certainly common in the hills and mountains of Galilee. However, despite the confident assertions by Lester and Tristram that it may well be the identity of Renan's blue mystery mini-birds encountered by him there, there are two major problems associated with this identification.

Firstly: only the adult male blue rock thrush is blue, adult females and juvenile individuals are brown. So unless all of the birds seen by Renan were males, or specimens of the brown females were also there but he either didn't notice them or (if he did) he didn't realize that they belonged to the same species as the blue ones, this weighs heavily against the blue rock thrush as an identity contender. Secondly, and on the subject of weighing heavily: the blue rock thrush is the size of a European starling Sturnus vulgaris and weighs up to 2 oz (60 g), with a total length of up to 9 in. Needless to say, therefore, this bird is far too big to be able to "rest on a blade of grass without bending it".

As noted by Tristram, the European roller Coracias garrulus is indeed common throughout the Galilee district in summer, and both sexes sport predominantly blue plumage. In terms of size, however, this stocky species is even bigger than the blue rock thrush, being the size of a European jay Garrulus glandarius, boasting a total length of up to 1 ft, sometimes slightly more, and a weight of up 5.3 oz (150 g). Consequently, it has even less chance than the blue rock thrush of being able to "rest on a blade of grass without bending it".

European roller (© Zeynel Cebeci/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

European roller (© Zeynel Cebeci/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

When I first read that memorable descriptive line from Renan's account of the Galilean mystery blue birds, I thought straight away that the only birds small enough and light enough in weight to correspond with it would be hummingbirds – but these of course are all exclusively New World in occurrence. However, as I then thought, they do have some similarly-sized Old World ecological counterparts – the nectariniids or sunbirds. Although taxonomically unrelated, by sharing the hummingbirds' lifestyle the sunbirds through convergent evolution have come to look and behave very much like them. Could it be, therefore, that the identity of Renan's feather-light mini-birds is a sunbird?

Only one species exists in the Israel/Palestine region of the Middle East – the Palestine sunbird Cinnyris osea (formerly Nectarinia osea). Contrary to Tristram's claim, this species can appear blue, or at least the breeding male can, which sports iridescent plumage that shimmers green or blue in sunlight, depending upon the angle at which it is observed. And it is certainly a much better fit for Renan's mini-birds than either the blue rock thrush or the roller in terms of its size, with even the male (larger than the female) not exceeding a total length of 4.75 in, and a weight of 0.3 oz (8 g). One could certainly imagine such a minuscule bird being able to rest upon a sturdy blade of grass without bending it, especially with a mountain breeze providing a counterbalance to the sunbird's weight (such that it is) upon the blade.

This is so obvious that it surprises me how readily both Lester and (especially) Tristram (given his ornithological expertise) rejected T.G.P.'s suggestion that the Palestine sunbird was the likeliest candidate for Renan's mystery mini-birds. (Having said that, Lester was basing his view upon what he had read in Tristram's book, as opposed to proffering an entirely independent one of his own.) True, their opposition was founded largely upon claims that this species simply wasn't common enough in the Galilean district to be a tenable identity, but they should have conceded that in terms of size alone, as well as colouring, it was a far more plausible one than either of their own favoured, but much heavier, candidates.

A breeding male Palestine sunbird in Israel (© Tom David PikiWiki Israel/Wikipedia – CC BY 2.5 licence

)

A breeding male Palestine sunbird in Israel (© Tom David PikiWiki Israel/Wikipedia – CC BY 2.5 licence

)

So how can this ornithological paradox be reconciled? Might it simply be that the Palestine sunbird is actually more common in Galilee than attested to by Tristram and Lester? Or perhaps, more specifically, it is more common there during the months of March and April to which Renan was alluding in his description of its wildlife? Worth noting, moreover, is that this species' males do sport their iridescent breeding plumage during those particular months (click here, for instance, to see a photograph of one such specimen exhibiting shimmering blue/green plumage that was snapped during March 2013 in Israel by Volker Hesse).

Of course, as with the blue rock thrush contender, if we are to take the Palestine sunbird's identity candidature seriously we would have to assume that because only its breeding males are blue (or green, depending upon viewing angle), these were the only individuals to catch Renan's eye, with the even smaller, dowdy, grey-and-white females overlooked by him or at least not deemed attractive enough to merit a mention in his description. To my mind, this is not an unreasonable prospect, as the breeding males are exceedingly eyecatching, resembling living jewels, and therefore certainly likely to eclipse the drab females when attracting an observer's attention.

A further possibility is that Renan's description was overly romantic – a criticism that has been directed at his writings by various scholars and critics in the past. Perhaps he saw sunbirds somewhere else in the Israel/Palestine region as opposed to in Galilee, but added them to his account of Galilee's wildlife as a descriptive flourish – i.e. poetic licence? Or might he have misremembered where he saw them, erroneously claiming that they occurred in Galilee when in reality he had seen them elsewhere in this region? Or could these feather-light fliers have been entirely fictitious, created by Renan to enhance still further the idyllic image of Galilee conjured forth by his lyrical narrative?

A hummingbird hawk moth with slaty-blue body, newly emerged from its chrysalis (© Jean-Pierre Hamon/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

A hummingbird hawk moth with slaty-blue body, newly emerged from its chrysalis (© Jean-Pierre Hamon/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

One final, admittedly remote, but nonetheless intriguing identity for Renan's mystery mini-birds of Galilee comes to mind – is it possible that they were not birds at all but were instead a certain very famous avian impersonator from the insect world? The species that I have in mind is the hummingbird hawk moth Macroglossum stellatarium, which so closely resembles a hummingbird not only in size but also in behaviour that when seen in flight and hovering around flowers, imbibing nectar using its long slender proboscis, it is often mistaken by non-naturalists for such a bird.

Furthermore, not only does this species occur in the Israel/Palestine region and can produce 3-4 broods a year so that adults are seen all year round, but also its body in particular (and to a lesser extent its wings) can appear a powdery slaty-blue colour when viewed in sunlight. And as it is even smaller and lighter in weight than the Palestine sunbird, it assuredly could "rest on a blade of grass without bending it".

How ironic it would be if both Renan and the trio of correspondents debating his mystery mini-birds in the pages of Hardwicke's Science-Gossip more than 150 years ago had all been led entirely astray, that the true nature of those tiny blue blade-resters was not avian at all, but rather that of an incognito insect, a masquerading moth.

Hummingbird hawk moth hovering alongside a flower, convergent evolution having transformed this insect into an extraordinarily precise facsimile of a hummingbird (© Krizzz2020/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Hummingbird hawk moth hovering alongside a flower, convergent evolution having transformed this insect into an extraordinarily precise facsimile of a hummingbird (© Krizzz2020/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

September 30, 2021

LAOCOÖN, HIS SONS, AND POSEIDON'S CRESTED SERPENTS FROM THE SEA

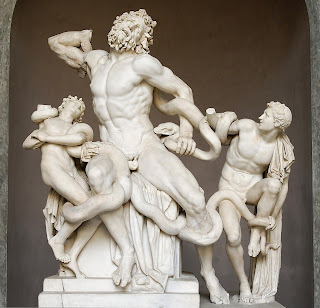

The famous ancient Greek marble statue, 'Laocoön and His Sons', unearthed within an Italian vineyard in 1506, depicting the Trojan priest Laocoön and his twin sons being slain by a pair of huge serpents (public domain/Wikipedia)

The famous ancient Greek marble statue, 'Laocoön and His Sons', unearthed within an Italian vineyard in 1506, depicting the Trojan priest Laocoön and his twin sons being slain by a pair of huge serpents (public domain/Wikipedia)

In February 1506, a magnificent, mostly-intact marble statue in the Hellenistic baroque style was unearthed within the grounds of a vineyard owned by a Felice de Fredis, near Santa Maria Maggiore, Italy. As his great interest in classical works was well known, Pope Julius II was duly informed of the statue's discovery, and he in turn swiftly sent a team of experts to the vineyard in order to evaluate it personally and report back to him; the team included a young Michelangelo.

The statue consisted of three human figures, of which the central, adult male figure was approximately life-sized, whereas the two male youths flanking him were slightly less so, thereby enhancing the central figure's dramatic appearance. The faces and bodies of all three figures were contorted and twisted with tortured agony and fear – and for good reason. Two huge snakes were coiled around this unfortunate human trio, savagely attacking them with lethal intent. The statue was taken to the Vatican, where it has remained on public display ever since in one of its museums.

There has been much controversy as to whether this very dynamic work of art is one and the same as a certain statue written about in ancient works, and which dated back to the 2nd Century BC; or whether it is a somewhat later copy of that early statue (which some believe may actually have been created from bronze, not marble); or whether it is a much later, original work, possibly inspired by but not a direct copy of the 2nd-Century BC statue. One or other of the last two options is now deemed the most likely identity.

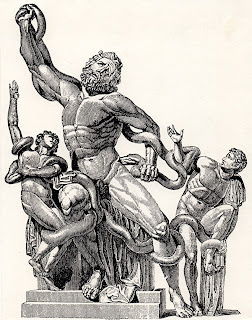

A vintage engraving of the statue 'Laocoön and His Sons', in which the illustrator has restored the missing portions to portray how the statue may have originally appeared when complete and unbroken (public domain)

A vintage engraving of the statue 'Laocoön and His Sons', in which the illustrator has restored the missing portions to portray how the statue may have originally appeared when complete and unbroken (public domain)

The time period of this vineyard-unearthed statue's creation has also attracted dissension, with proffered dates ranging from c.200 BC to the 70s AD, with an approximate time-span of 27-BC-68 AD being the most favoured nowadays. Moreover, it is believed to have spent some time adorning the palace of the Roman Emperor Titus (reigned 79-81 AD). Its creators may have been a trio of Greek sculptors from Rhodes – namely, Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus.

One aspect concerning the vineyard statue for which there is absolutely no controversy, however, is who and what it depicts, because the fraught scene in question is one of the most famous in all of classical Graeco-Trojan mythology. The central figure is the Trojan priest Laocoön, and the two youths are his twin sons Antiphantes (aka Antiphas) and Thymbraeus. Accordingly, the title by which this statue is officially known in the art world is 'Laocoön and His Sons'.

But what is of particular interest and relevance to this present ShukerNature article is the zoological nature of the giant serpents lethally encircling the doomed trio's bodies, which are named Porces and Chariboea (aka Curissia or Periboea). Based upon the statue alone, they simply look like muscular, constricting snakes, quite possibly inspired by the African rock python Python sebae, often kept as a pet in ancient Greece and Rome too. Consequently, they have been readily accepted as such by some authors. Conversely, ancient written accounts of their morphology and origin suggest something rather more exotic.

An African rock python (public domain)

An African rock python (public domain)

As with the specific identity and age of the statue, there is contention regarding the precise background of Laocoön and why the snakes – or whatever they are – were attacking him and his sons, with different ancient sources making differing claims. As this is not the relevant place to examine and discuss in detail each of these sources and claims, suffice it to say therefore that the three major claims are that Laocoön was:

A Trojan priest who warned the Trojans not to trust the huge wooden horse offered to them as a gift by the opposing Greeks; his warning went unheeded and the Trojans fatally wheeled the horse into their city, thereby precipitating their destruction at the hands of the Greek soldiers concealed inside it, but to punish him for trying to prevent the horse from being accepted, the goddess Athena (the Greeks' divine supporter) sent two giant snakes to kill him and his sons.

Or: A Trojan priest of Apollo who broke his oath of celibacy by fathering his sons, so as a punishment Apollo sent two giant snakes to kill him and his sons.

Or: A Trojan priest of Poseidon who desecrated his temple by indulging in sexual intercourse within its perimeter, so as a punishment Poseidon sent forth two great serpents of the sea across the waves to kill him and his sons.

Engraving of Laocoön and his sons being attacked by giant snakes from the sea, in Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, c.1516-20 (public domain)

Engraving of Laocoön and his sons being attacked by giant snakes from the sea, in Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, c.1516-20 (public domain)

Of these, the third version is the one most commonly cited and favoured, and is featured dramatically within ancient Roman poet Virgil's classic epic The Aeneid (written 29-19 BC):

Two snakes from Tenedos (I shudder to think of it) come on over the peaceful sea unwinding their huge coils and swim abreast towards the shore. Their breasts rise among the billows, their bloody crests tower over the waves; their flanks skim the abyss, and their vast tails curve in sinuous coils, the waves carrying the spume. Already they have reached the beach: their burning eyes shine, red with blood and flame; their tongues, like a dart, flicker in their mouths, which they lick, hissing...

Tenedos is an island in Turkey where according to legend the Greeks hid their army, to fool the Trojans into believing that the war between their two nations was finally over – a treacherous ruse augmented by their deceitful gifting to the Trojans of the Trojan Horse.

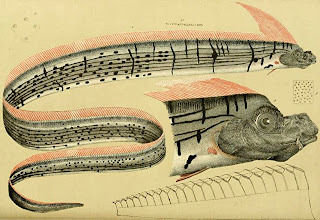

Vintage illustration of the oarfish (aka giant oarfish or ribbonfish) (public domain)

Vintage illustration of the oarfish (aka giant oarfish or ribbonfish) (public domain)

Way back in the 1970s, I studied sections of The Aeneid (including the above one) as part of my Latin O-Level course, and I can still well remember thinking how very reminiscent Poseidon's fire-crested sea serpents were of a certain huge and highly distinctive species of marine fish. Moreover, when I subsequently acquired and read veteran cryptozoologist Dr Bernard Heuvelmans's classic tome In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents (1968), I discovered that I wasn't the only one to have recognised this similarity. Here is what Heuvelmans wrote:

The colour of these snakes' crests makes one suspect that Virgil's terrific picture may be inspired, in parts at least, by one of the most mysterious of the world's larger fishes, the oarfish Regalecus glesne...It is long and serpentine, and right along its spine is a crest of bright coral red which it can raise into a sort of plume on its head.

Just how long this surreal but wholly inoffensive ribbon-like fish can be is very much a matter for conjecture, as I examined in an entire chapter devoted to it within my book A Manifestation of Monsters (2015), and also here on ShukerNature. It is certainly known to measure over 30 ft long, but some plausible if unconfirmed lengths of up to 50 ft have also been documented.

A Greek wall plate of mine depicting the vineyard-unearthed 'Laocoön and His Sons' statue (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A Greek wall plate of mine depicting the vineyard-unearthed 'Laocoön and His Sons' statue (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Consequently, whereas the vineyard statue's visual portrayal of Laocoön and his sons' dreadful fate at the coils of their constricting nemeses was probably more naturalistic, merely inspired by pythons, verbal versions of the Laocoön legend like that of Virgil in which the giant serpents were huge crested snakes of the sea sent across the waves by Poseidon were more melodramatic, and conceivably inspired by rare sightings and strandings ashore of the spectacular oarfish. (They certainly do not recall any of the known, elapid species of sea snake currently documented.) Or, as Heuvelmans put it:

It is therefore more likely that the two serpents from Tenedos whose "bloody crests tower over the waves" were modelled on oarfish. There is even less doubt that these huge fragile fish could not have done the least harm, even to a newborn baby left upon the beach. But poetic licence will explain much...

Indeed it will.

My replica in resin from Greece of the 'Laocoön and His Sons' statue (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My replica in resin from Greece of the 'Laocoön and His Sons' statue (© Dr Karl Shuker)

September 21, 2021

SNAKES WITH WINGS - AND OTHER STRANGE THINGS!

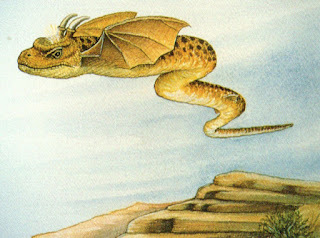

Artistic representation of the Namibian flying snake based upon eyewitness descriptions (© Philippa Foster)

Artistic representation of the Namibian flying snake based upon eyewitness descriptions (© Philippa Foster)

I went once to a certain place in Arabia, almost exactly opposite the city of Buto, to make inquiries concerning the winged serpents. On my arrival I saw the back-bones and ribs of serpents in such numbers as it is impossible to describe: of the ribs there were a multitude of heaps, some great, some small, some middle-sized. The place where the bones lie is at the entrance of a narrow gorge between steep mountains, where there open upon a spacious plain communicating with the great plain of Egypt. The story goes that with the spring the winged snakes come flying from Arabia towards Egypt, but are met in this gorge by the birds called ibises, who forbid their entrance and destroy them all. The Arabians assert, and the Egyptians also admit, that it is on account of the service thus rendered that the Egyptians hold the ibis in so much reverence.

Herodotus – The History, Book II

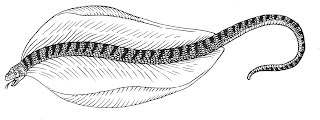

Despite its common name, the so-called flying snake Chrysopelea ornata of southeast Asia cannot actively fly. However, it is well known that this distinctive species can glide for up to 300 ft through the air by launching itself from a tree while simultaneously spreading its ribs and flattening its body, until its undersurface is concave, thereby transforming itself into a ribbon-shaped parachute.

Southeast Asia's known flying snake Chrysopelea ornata (public domain)

Southeast Asia's known flying snake Chrysopelea ornata (public domain)

Yet according to some remarkable reports filed away within the bulging archives of cryptozoology, there may be some currently-undescribed species of snake that are capable of true flight, i.e. achieved with the aid of wings or comparable means of active propulsion.

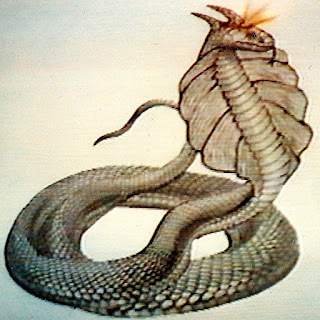

THE NAMIBIAN FLYING SNAKE

One such mystery beast is the supposed flying snake that has been reported not only by the native Namaqua people but also by a number of European eyewitnesses within the Namib Desert of southern Namibia. According to their generally consistent accounts, it has a brown or yellow body mottled with dark spots, an inflated neck, and a very large head bearing a pair of short backward-pointing horns - plus, very remarkably, a glowing 'torch' in the centre of its brow. Most astonishing of all, however, is the pair of membranous bat-like wings allegedly emerging from the sides of its neck or mouth.

Eyewitnesses have stated that this extraordinary snake launches itself from the summit of a high rocky ledge, then soars down to the ground, landing with an appreciable impact and producing scaly tracks in the dusty earth. In 1942, while tending sheep in the mountains at Keetmanshoop, teenager Michael Esterhuise threw a stone at what he had assumed to be a large monitor lizard lurking inside a rocky crack. When it emerged, however, it revealed itself to be a big snake with a pair of wing-like structures projecting from the sides of its mouth.

A second reconstruction of the Namibian flying snake's possible appearance (© Tim Morris)

A second reconstruction of the Namibian flying snake's possible appearance (© Tim Morris)

On a separate occasion, moreover, one of these serpents soared down towards Esterhuise after having launched itself from a rocky ledge. When it landed, hitting the ground with great force, Esterhuise fainted, and when he was later found (unharmed though still unconscious) by a search party, the snake had gone but its tracks remained. They were subsequently examined by no less celebrated a naturalist than Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer – curator of South Africa's East London Museum and immortalised zoologically as the discoverer of that famous 'living fossil' fish the coelacanth Latimeria chalumnae in 1938. In her opinion, these tracks, containing the clear impression of scales, were indeed consistent with the marks that a snake would make.

A South African television documentary by Angus Whitty Productions, entitled In Search of the Giant Flying Snake of Namibia and first broadcast in 1995, contained testimony from a number of alleged eyewitnesses, which provided estimates of this mystery serpent's total length that ranged from 9 ft to 15 ft. The programme also specially prepared and featured on-screen a detailed drawing of the latter snake's alleged appearance based upon such testimony.

Screenshot of the flying snake drawing from In Search of the Giant Flying Snake of Namibia (© Angus Whitty Productions – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Screenshot of the flying snake drawing from In Search of the Giant Flying Snake of Namibia (© Angus Whitty Productions – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Well worth noting is that Namibia is a former German colony, so it is not impossible that Teutonic legends of lightning snakes retold here by German settlers may have infiltrated and influenced native Namibian lore. However, such legends cannot leave physical, tangible tracks like those examined by Miss Courtenay-Latimer, so perhaps a real snake is indeed present but one whose appearance has been exaggerated or distorted in the telling due to shock by those who have unexpectedly encountered it.

If so, the Namibian flying snake may still be an undescribed species, but one that in reality merely sports a pair of extensible lateral membranes similar to those of the famous Asian gliding lizard Draco volans(though whether such structures would be sufficiently adept, aerodynamically, to bear so sizeable a snake through the air is another matter), plus a pair of horny projections resembling the 'eyebrow' horns of certain African vipers. As for its glowing 'torch', this may be nothing more mysterious than a highly-reflective patch of shining scales on its brow.

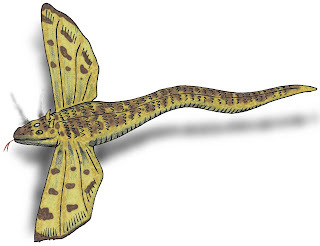

THE TL'IISH NAAT'A'I OR ARIZONA FLYING SNAKE

For a number of years, American cryptozoologist Nick Sucik has been investigating reports of an equally mystifying but even more obscure aerial anomaly of the serpentine kind - the tl'iish naat'a'í (pronounced 'kleesh-not-ahee' and translated as 'snake that flies'). Also known as the Arizona flying snake, apparently this bizarre reptile is a familiar creature there to the Navajo Nation, and to the Hopi Nation as well (who refer to it by names translating as 'sun snake'). They all describe it as being fundamentally serpentine in form, generally around 2 m long, and dull grey in colour (although sometimes said to have a red belly), but possessing a pair of retractable and virtually transparent wing-like membranes. These emerge from behind its head, run laterally along much of its body's length, can flap vigorously and very rapidly, and are thus used for active flight (rather than passive gliding) purposes.