Karl Shuker's Blog, page 5

June 30, 2023

HAGGLING OVER THE HAFGUFA

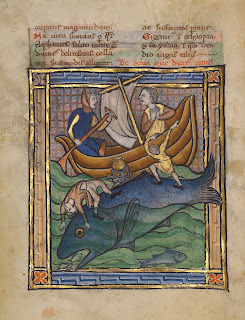

The hafgufa, as depicted in a medieval manuscript, namely the

British Library MS. Harley 3244, fol. 65r, 1236, c.1250,

(public domain)

The hafgufa, as depicted in a medieval manuscript, namely the

British Library MS. Harley 3244, fol. 65r, 1236, c.1250,

(public domain)

The hafgufa is a mysterious sea monster describedin Konungs skuggsjá ('The King's Mirror'), which is a mid-13th-CenturyOld Norse manuscripts – but that is not all. It has actually been traced back asfar as an account in a 2nd-Century-AD text from Alexandria, Egypt, entitledPhysiologus, whose text is accompaniedby illustrations of a whale-like creature termed the aspidochelone, depicted withits huge mouth wide open and fishes jumping into it.

According to The King's Mirror:

It is said of the nature of this fish [the hafgufa] that, whenit goes to feed, it gives a great belch out of its throat, along with whichcomes a great deal of food. All sorts of nearby fish gather, both small andlarge, seeking there to acquire food and good sustenance. But the big fishkeeps its mouth open for a time, no more or less wide than a large sound orfjord, and unknowing and unheeding, the fish rush in in their numbers. And whenits belly and mouth are full, [it] closes its mouth, thus catching and hidinginside it all the prey that had come seeking food”

The hafgufa is also mentioned in various otherNorse manuscripts from this same period. Moreover, a similar description for theaspidochelone is given as follows in Physiologus:

When it is hungry it opens its mouth and exhales a certain kindof good-smelling odor from its mouth, the smell of which, once the smaller fishhave perceived it, they gather themselves in its mouth. But when his mouth isfilled with diverse little fish, he suddenly closes his mouth and swallowsthem.

In the scientific age, there has been muchspeculation and dispute as to whether the hafgufa was based upon a realcreature, and, if so, what that creature might be, with the consensus beingthat it was probably some kraken-like monster.

An

a

spidochelonefrom

a Frenchmanuscript, c.

1270

, held at the

J. Paul Getty Museum

(public domain)

An

a

spidochelonefrom

a Frenchmanuscript, c.

1270

, held at the

J. Paul Getty Museum

(public domain)

Now, however, this maritime mystery beast'strue nature may at last have been revealed, thanks to the publicising of a remarkablemode of feeding behaviour practised by various rorqual whales.

Known as trap feeding and firstscientifically recorded in 2010, various humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae and Bryde's whales Balaeonoptera brydei have been observed waiting motionless at thewater surface in an upright position with their huge mouths wide open, intowhich shoals of fishes unsuspectingly swim to their doom, fatally mistaking thewhales' gaping jaws for shelter, until the jaws close, engulfing them!

Moreover, this eyecatching activity haslately attracted worldwide attention thanks to an Instagram video clip of aBryde's whale performing it that went vital after featuring in a 2021 BBCwildlife documentary (click here to view this clip).

According to the Norse manuscripts, as notedabove, the hafgufa behaves in a similar manner, even actively attracting shoalsof fishes to swim into its open mouth by emitting a specific perfume. And sureenough, when seeking to lure fishes into their mouths by regurgitating food,both the humpback and Bryde's whales produce a distinct smell.

A detailed study examining and comparingmedieval Norse accounts of the hafgufa with modern-day reports of trap feedingby rorquals was published on 28 February 2023 in the journal Marine Mammal Science (click here to read it). The paper was co-authoredby maritime archaeologist John McCarthy, from the College of Humanities, Artsand Social Sciences at Flinders University in Australia, who had becomeinterested in this correlation after reading about the hafgufa in traditionalNorse mythology.

Once again, therefore, it seems likely thatan ostensibly fabulous monster of mythology can lay claim to a firm basis in mainstreamzoological fact after all.

Another illustrationof the hafgufa, this time from Ortelius's 1658 map of Iceland (public domain)

Another illustrationof the hafgufa, this time from Ortelius's 1658 map of Iceland (public domain)

June 9, 2023

AN 'ELL OF AN EEL?

Just how big can moray eels get? A vintage illustrationof the Mediterranean moray (aka Roman eel) Muraenahelena (public domain)

Just how big can moray eels get? A vintage illustrationof the Mediterranean moray (aka Roman eel) Muraenahelena (public domain)

Extra-large,even giant-sized, eels are frequently cited as potential identities for allmanner of freshwater and maritime monsters around the world, including Britain's very ownNessie. Down through the years, I've documented a fair few of these reports,from such disparate, far-flung locations as North America, New Zealand, and theMascarene Islands. Now, another location, Vietnam, can apparently be added tothat list.

LongstandingLoch Ness Monster researcher Steve Feltham hosts a very interesting andinformative public Facebook group entitled 'Steve Feltham, Nessie Hunter,Interactive Collective', which acts as a forum for sharing relevant informationrelevant to this pre-eminent cryptid. On 13 October 2022, group member MikeGavan from New Zealand posted the following fascinating account of what mayhave been a truly gigantic eel encountered underwater off Vietnam by one of hisfriends:

I’ve just had a visit from an older friend ofmine, Tim.

Tim was a deep sea diver in the 1970s, workingfrom a bell at an average depth of 200 m [656 ft], his work was in the area ofundersea recovery, maintenance for the oil industry world wide.

Around 1974, Tim was diving on a recovery jobat 220 m [722 ft] off the coast of Nha Trang, Vietnam.

His job was to recover a length of specialpurpose ducting that had been lost overboard, he was to locate it, tie it andawait a winch.

About 10 minutes into his dive from the bellTim saw what he believed was part of the ducting and proceeded towards it, [but]as he got close enough to touch it he realised that it was not ducting!

"It was soft and felt like an eel or fish,the girth was around 6 ft, when I did actually touch it a large head lookinglike a snake or reptile appeared in my lamps, I contacted the top and asked ifthey were seeing what I was seeing as I had a camera attached to my dive suit,yes was the reply. ”Go to the bell now Tim, repeat, go to the bell now!” wastheir reply, I estimated the creature to be over 100ft, possibly 120-130 ft inlength, I turned and headed bell asap, which wasn’t quickly due to my dive suitand gear, it was terrifying and I never looked back, I’ve seen giant sharks,strange lights etc but that snake thing was the weirdest thing I ever saw in mytenure as a deep sea diver!"

Tim is now 78 years old, honest andtrustworthy & also sound of mind.

He lives on a back country farm of 4000 acresin solitude now.

This was relayed to me literally 2 hours ago.

Thecreature that immediately came to mind when I read this report was a moray eelor muraenid, of which there are over 200 species found in tropical andtemperate waters worldwide, often in coastal regions, and are famouslyserpentine in appearance. However, the longest known species, the slender giantmoray Strophidion sathete, is 'only'up to 13 ft long, a far cry indeed from the immense length cited by eyewitnessTim for the elongate entity that he allegedly encountered at very close range (andeven allowing for possibly a sizeable degree of over-estimation on Tim's part dueto the extreme shock and fear that he'd clearly experienced).

Butcould there be exceptional individuals far greater in size than any recorded byscience existing incognito in our oceans, their huge dimensions buoyed by theirliquid environment? If so, they would indeed be veritable monsters. I wonderwhat happened to the film that Tim's camera recorded of this creature, asviewed by his above-surface team? That would certainly be well worth a watch!

A vividillustration from 1801 of Gymnothoraxfavagineus, the aptly-named leopard moray eel (public domain)

A vividillustration from 1801 of Gymnothoraxfavagineus, the aptly-named leopard moray eel (public domain)

May 19, 2023

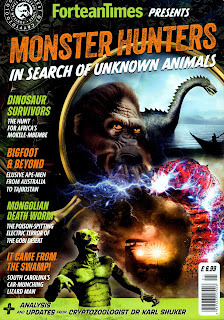

FORTEAN TIMES PRESENTS MONSTER HUNTERS: IN SEARCH OF UNKNOWN ANIMALS - MY LATEST MAJOR CRYPTO-CONTRIBUTION

Thefront cover of the new cryptozoology-themed ForteanTimes bookazine Monster Hunters (��Fortean Times/Diamond PublishingLimited ��� reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis foreducational/review purposes only)

Thefront cover of the new cryptozoology-themed ForteanTimes bookazine Monster Hunters (��Fortean Times/Diamond PublishingLimited ��� reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis foreducational/review purposes only)

Bookazines are increasingly popular andprevalent in bookstores and on newsstands nowadays, constituting a handy publication format that, as its namesuggests, is midway between a magazine and a book. They sell well too, which iswhy I am currently involved in what, if all ultimately transpires according to plan,will be a series of bookazines featuring various of my animal anomaly writings fromdown through the years ��� but more about that some other time.

Instead, this present ShukerNature blog articlefocuses upon what is to my knowledge the first UK bookazine concentratingspecifically upon cryptozoological subjects, and with which I am extremelyhappy to be associated via my varied contributions to it.

Published by the UK's veteran strange phenomenaperiodical Fortean Times, its fulltitle is Fortean Time Presents Monster Hunters:In Search of Unknown Animals, and contains 12 classic cryptozoology-themedarticles published by FT down throughthe years. Some of these are the result of field expeditions, others the productof bibliographical researches.

Moreover, as its in-house cryptozoologistfor over 30 years now, I was very kindly invited by FT to prepare not only a general introduction to this bookazine butalso a concise summary/update for each of its articles, thereby fulfilling muchthe same role as performed by the late Arthur C. Clarke for each episode in hisfamous 1980s TV show Arthur C. Clarke'sMysterious World.

The authors and co-authors of thearticles are: Neil Arnold, Loren Coleman, Edward Crabtree, Adam Davies (two articles),Richard Freeman, Martin Gately, Sharon Hill, Ruby Lang, Stu Neville, Todd Prescott,Richard Svensson, Michael Williams, and yours truly (two articles).

To avoid spoiling the many surprises instore when you read Monster Hunters, Idon't want to give too much away here, so I'll leave you to pair up the articles'authors with their subjects, but the subjects are: bigfoot, British mysterycats, Loch Ness monster, mokele-mbembe, Mongolian death worm, Nandi bear, Russianyeti, Scape Ore Lizard Man, Swedish lindorms, Tajikistan ghul, Trunko, and yowie.

All of the articles are reproduced herein all of their original full-colour glory, which together with my introductionyields an 80-page bookazine that surveys a vast, global range of cryptids inwhat is unquestionably one of the most engrossing crypto-compendia that I haveread for a very long time. Consequently, I unquestionably recommend anyone whohas an interest in mystery beasts, or knows someone else who does, to buy (at just��6.99 in shops, or online here at ��8.25 including p&p directlyfrom FT) this masterfully-compiled (andbargain-priced!) anthology of very notable crypto-creatures. I guarantee thatyou won't regret it!

To give you some additional ideas of whatto expect, here is FT's own publicityblurb for Monster Hunters:

Fromthe archives of FORTEAN TIMES, the world���s foremost journal ofstrange phenomena, comes a new collection exploring the world of cryptozoology��� the search for unknown animals.

Joinus on expeditions to far-flung Mongolia to find the dreaded DEATH WORM of theGobi Desert, to the Congo in search of a LIVING DINOSAUR and to Tajikistan onthe trail of TERRIFYING APE MEN. Explore the wilds of the USA on the track ofBIGFOOT and the South Carolina LIZARD MAN, or venture to the marshes of Swedento investigate sightings of GIANT SERPENTS. And sign up for closer-to-homehunts for NESSIE and BRITAIN���S MYSTERY BIG CATS, including the infamous ���EssexLion���. MONSTER HUNTERS takes readers on an exciting round-the-world quest totrack the most amazing, elusive and sometimes unbelievable crypto-creatures.Plus, the collection includes an introduction and updates and commentary oneach article by renowned cryptozoologist DR KARL SHUKER.

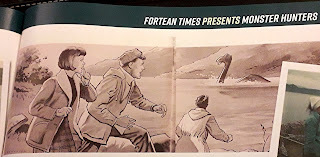

Finally: I mentioned above that I've writtena summary/update for all 12 of this bookazine's articles, but due to reasons ofspace one of them had to be omitted ��� my piece for the Nessie article. So now, asa ShukerNature exclusive, I am including it here, together with the illustration(as seen in the bookazine) that it refers to:

Perusing this article, Inoted two very different aspects that resonate with my own Nessie associations.First and foremost is his statement that "people can see the monster inanything". This is extremely pertinent, because just as I've documentedelsewhere in this bookazine [regarding another cryptid], eyewitnessdescriptions of what they claim to have been the LNM are so immensely variedthat it should be instantly apparent that no single type of creature is beingreported. Instead, a diverse range of different animal species, plus all mannerof non-living entities (boats, waves, atmospheric mirages, etc), have beensighted on the loch down through the decades but have been erroneously combinedby media reports and others to yield a single impossibly-varied and thereforenon-existent composite beast known to us all as Nessie. Having said that, someof the separate, component creatures that have been mistakenly united to yield Nessiemay themselves be novel beasts ��� extra-large eels, for instance, much longerthan officially-recognised specimens, and/or covertly-introduced specimens ofthe European giant catfish (wels). But what of the alleged LNM land sightings,where unfamiliar-looking beasts have supposedly been seen in their entirety? Ifgenuine, these cannot be explained via a composite-identity theory, which iswhy they intrigue me so much, and deserve far more attention than theygenerally receive. This article's second aspect of personal relevance to me isits illustration of three people looking across the loch at a classic 'head,neck, and hump' Nessie swimming by. That very same illustration was containedin a book chapter that as a child first made me aware of the LNM ��� but that'snot all. The book, Stranger Than People,published in 1968, also opened my eyes to many other mysteries, lighting withinme the flame of fascination for all things Fortean that has burned unabatedlyever since [click here to read more by me re Stranger Than People]. So I have a lot to thank it for!

TheLNM illustration in question, as contained in Monster Hunters (�� Fortean Times/DiamondPublishing Limited ��� reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Usebasis for educational/review purposes only)

TheLNM illustration in question, as contained in Monster Hunters (�� Fortean Times/DiamondPublishing Limited ��� reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Usebasis for educational/review purposes only)

April 29, 2023

THE SIPHONOPHORE FISH AND THE GIBBER FISH - TOTALLY DIFFERENT, YET ONE AND THE SAME!

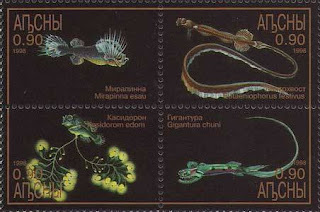

Asiphonophore fish depicted on an unofficial postage stamp released by the self-proclaimedGeorgian state of Abkhazia in 1998 (NB – its erstwhile genus has beenmisspelled on this stamp as Kasidorom,instead of Kasidoron) (public domain)

Asiphonophore fish depicted on an unofficial postage stamp released by the self-proclaimedGeorgian state of Abkhazia in 1998 (NB – its erstwhile genus has beenmisspelled on this stamp as Kasidorom,instead of Kasidoron) (public domain)

Appearancescan deceive, in more ways than one, as exemplified here by the truly remarkablecase of two very different fishes that turned out to be one and the same. Letme explain.

In1965, a small but spectacular fish called Kasidoron edom was describedin a Bulletin of Marine Science paperby C. Richard Robins and Donald P. de Sylva from the University of Miami's Instituteof Marine Science (click here to access this paper). Sole memberof a totally new genus and taxonomic family(until a second, similar species, K. latifrons, was recorded in 1969, fromthe western Indian Ocean), it became known as the siphonophore fish.

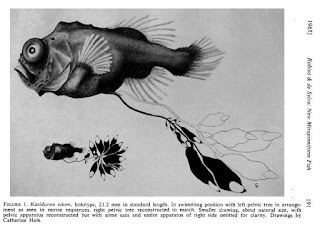

Drawings by Catherine Hale ofthe siphonophore fish, from the above-mentioned Bulletin of Marine Science

paper

by C. Richard Robins and Donald P. de Sylva (© CatherineHale/C. Richard Robins/Donald P. de Sylva/Bulletinof Marine Science – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial fair use basisfor educational/review purposes only)

Drawings by Catherine Hale ofthe siphonophore fish, from the above-mentioned Bulletin of Marine Science

paper

by C. Richard Robins and Donald P. de Sylva (© CatherineHale/C. Richard Robins/Donald P. de Sylva/Bulletinof Marine Science – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial fair use basisfor educational/review purposes only)

Thiswas due to its astonishing pelvic fins. These were greatly modified, the third ray in each one havingtransformed into a long, multi-branched tree-like organ dubbed the pelvic tree,hanging underneath its body, terminating in a series of luminous(?), leaf-like sacs, and closely resembling the tentacular appendagesof those superficially jellyfish-like composite creatures the siphonophores(exemplified by the famous Portuguese man-o'-war Physalia).

Knownat that time only from waters of around 6-165 ft depth, about 150 miles east ofFlorida's Cape Canaveral and northeast of Bermuda, this 1.25-in-longvelvet-black fish attracted appreciable interest, on account of its conjoinedpelvic fins' unique, extraordinary structure. This was assumed to be a devicefor warding off predators, as they would be likely to mistake its harmless formfor the deadly stinging tentacles of genuine siphonophores.

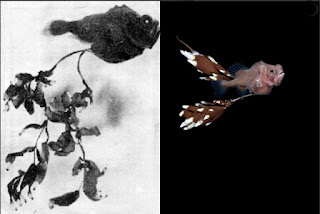

Two siphonophore fish photographsdiscovered by me recently

here

on the Quorawebsite (No copyright/ownership details for them are given there, and despite considerableonline searches I have been unable to locate any either, so I am including thesephotos on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposesonly)

Two siphonophore fish photographsdiscovered by me recently

here

on the Quorawebsite (No copyright/ownership details for them are given there, and despite considerableonline searches I have been unable to locate any either, so I am including thesephotos on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposesonly)

Aftera time, however, the remainder of this fish's anatomy began to receiveattention too, and researches ultimately disclosed that in spite of itsdistinctive appearance the siphonophore fish was not a new species at all.

Onthe contrary, it was unmasked as the hitherto-unknown juvenile form of an oddlittle species called the gibber fish (aka gibberfish) Gibberichthyespumilus, which had been formally described and named in 1933. It had beendiscovered in the waters around Bermuda and the Bahamas.

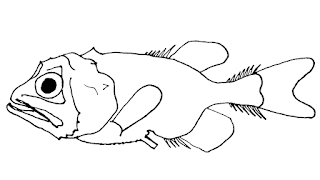

Sketch of the gibber fish G. pumilus (Haplochromis/Wikipedia – publicdomain); click

here

to view a colour photograph of a gibber fish.

Sketch of the gibber fish G. pumilus (Haplochromis/Wikipedia – publicdomain); click

here

to view a colour photograph of a gibber fish.

Previouslyknown only from four specimens, this deepwater denizen attains a total lengthof 4.5 in, and inhabits the western North Atlantic, as well as the SouthPacific waters close to the Samoan Islands. With a very large head, a deep,laterally flattened body, and perfectly normal fins lacking any vestige of itsjuvenile's astounding tentacle-impersonating pelvic tree, the gibber fish isplaced within a taxonomic family of its own, most akin to the squirrelfishesand slimeheads.

Moreover,as the second siphonophore fish species, K.latifrons, has also been reclassified as a gibber fish, it is now known as G. latifrons.

The full set of unofficialAbkhazia postage stamps, which includes not only the siphonophore fish stamp(bottom left) but also a stamp depicting the hairy fish [see below for details](top left) (public domain)

The full set of unofficialAbkhazia postage stamps, which includes not only the siphonophore fish stamp(bottom left) but also a stamp depicting the hairy fish [see below for details](top left) (public domain)

Interestingly,a very similar scenario of extreme metamorphosis from juvenile to adult was more recently revealed with another enigmatic,highly distinctive little fish that had long puzzled ichthyologists – theso-called hairy fish Mirapinna esau. Youcan read about its own very intriguing history here on ShukerNature, and also here in an early cryptozoology articleof mine reproduced on ShukerNature.

This ShukerNatureblog article is expanded from my book TheEncyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals.

March 28, 2023

MOUNT POPA���S ERSTWHILE MYSTERY DOG, AND AUSTRALIA���S STILL-UNEXPLAINED YOKYN ��� A COUPLE OF CURIOUS CANINE CRYPTIDS

ABurmese dhole ��� this dhole subspecies was not scientifically described until1941, when its existence was finally accepted (�� Yathin S. Krishnappa/Wikipedia���

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

ABurmese dhole ��� this dhole subspecies was not scientifically described until1941, when its existence was finally accepted (�� Yathin S. Krishnappa/Wikipedia���

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Down through the decades, I have documenteda wide range of canine cryptids, but two of the least-known examples are thosepresented here, making their ShukerNature debut. One is now a former mysterycanid, the other remains an enigma.

A wild dog of once-controversial scientificstatus was a mysterious specimen discovered on Mount Popa, a dormant volcano inthe region of Mandalay in central Burma (now Myanmar). Renowned Britishzoologist Reginald I. Pocock stated in 1936 that no specimens of Asia's verydistinctive wild red dog or dhole Cuon alpinus had ever been obtainedfrom Burma, but shortly afterwards he learnt that acclaimed mammalogist andanimal collector Guy C. Shortridge had secured a specimen on Mount Popa.

Naturally, Pocock was anxious to examinethis unique example, an adult female, especially as Shortridge alleged that itonly had five pairs of teats (female dholes have 6-8 pairs), and weighed only19 lb (unusually light for a dhole). However, after studying its skull,uncovered at the British Museum, Pocock recognized that it had been nothingmore than an old, small domestic dog Canisfamiliaris, with a high crown and short muzzle. But, ironically, genuineBurmese dholes were obtained later, and in 1941 Pocock christened theirsubspecies C. a. adustus ��� a taxonomicclassification still recognised today.

A dingo ��� the identity of Australia'selusive yokyn? (Katy Platt/Wikipedia ��� copyright-free)

A dingo ��� the identity of Australia'selusive yokyn? (Katy Platt/Wikipedia ��� copyright-free)

As for the yokyn ��� this still-unexplained canine cryptid is a strangedog-like beast reputedly well-known to Australian aboriginals and farmers. Saidto be approximately half the size of a full-grown dingo, with disproportionatelylong claws, a stocky, muscular build,and a very variable pelage (sometimes brindled, sometimes even multi-coloured),a specimen has yet to be formally examined, so its identity remains uncertain (Fate, May 1977; also click here for additional details online).

An unknown species, an odd type of feraldomestic dog, a dingo Canis dingo(aka C. lupus dingo aka C. familiaris dingo), a dog-dingocrossbreed, and even a surviving mainland race of the marsupial Tasmanian wolf Thylacinuscynocephalus are among those identities on offer. If anyone reading thisShukerNature article has further information concerning the yokyn, I'd love toreceive details.

This ShukerNature article is excerpted and updated frommy book ExtraordinaryAnimals Revisited.

MOUNT POPA’S ERSTWHILE MYSTERY DOG, AND AUSTRALIA’S STILL-UNEXPLAINED YOKYN – A COUPLE OF CURIOUS CANINE CRYPTIDS

A Burmese dhole – this dhole subspecies was not scientifically described until 1941, when its existence was finally accepted (© Yathin S. Krishnappa/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

A Burmese dhole – this dhole subspecies was not scientifically described until 1941, when its existence was finally accepted (© Yathin S. Krishnappa/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Down through the decades, I have documented a wide range of canine cryptids, but two of the least-known examples are those presented here, making their ShukerNature debut. One is now a former mystery canid, the other remains an enigma.

A wild dog of once-controversial scientific status was a mysterious specimen discovered on Mount Popa, a dormant volcano in the region of Mandalay in central Burma (now Myanmar). Renowned British zoologist Reginald I. Pocock stated in 1936 that no specimens of Asia's very distinctive wild red dog or dhole Cuon alpinus had ever been obtained from Burma, but shortly afterwards he learnt that acclaimed mammalogist and animal collector Guy C. Shortridge had secured a specimen on Mount Popa.

Naturally, Pocock was anxious to examine this unique example, an adult female, especially as Shortridge alleged that it only had five pairs of teats (female dholes have 6-8 pairs), and weighed only 19 lb (unusually light for a dhole). However, after studying its skull, uncovered at the British Museum, Pocock recognized that it had been nothing more than an old, small domestic dog Canis familiaris, with a high crown and short muzzle. But, ironically, genuine Burmese dholes were obtained later, and in 1941 Pocock christened their subspecies C. a. adustus – a taxonomic classification still recognised today.

A dingo – the identity of Australia's elusive yokyn? (Katy Platt/Wikipedia – copyright-free)

A dingo – the identity of Australia's elusive yokyn? (Katy Platt/Wikipedia – copyright-free)

As for the yokyn – this still-unexplained canine cryptid is a strange dog-like beast reputedly well-known to Australian aboriginals and farmers. Said to be approximately half the size of a full-grown dingo, with disproportionately long claws, a stocky, muscular build, and a very variable pelage (sometimes brindled, sometimes even multi-coloured), a specimen has yet to be formally examined, so its identity remains uncertain (Fate, May 1977; also click here for additional details online).

An unknown species, an odd type of feral domestic dog, a dingo Canis dingo(aka C. lupus dingo aka C. familiaris dingo), a dog-dingo crossbreed, and even a surviving mainland race of the marsupial Tasmanian wolf Thylacinus cynocephalus are among those identities on offer. If anyone reading this ShukerNature article has further information concerning the yokyn, I'd love to receive details.

This ShukerNature article is excerpted and updated from my book Extraordinary Animals Revisited.

January 20, 2023

ON THE ROAD FOR GIANT TOADS

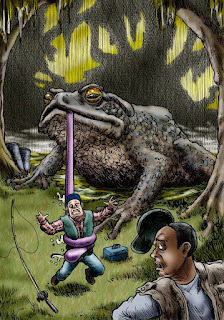

Artistic representation of a giant toad (© Richard Svensson)

Artistic representation of a giant toad (© Richard Svensson)

Today is the 14th anniversary of my ShukerNature blog's official launch (20 January 2009), so now, almost 800 ShukerNature articles later, here is my latest one, to mark this auspicious occasion, and inspired by a fascinating news report that I read just a few hours ago.

The news report in question (which can be accessed directly here) reveals the recent discovery and capture in Queensland, Australia, of a truly gigantic specimen of cane toad Bufo marinus (=Rhinella marina). Weighing a colossal 2.7 kg/6 lb (six times that of normal specimens), and dubbed Toadzilla, it may be the biggest toad of any kind ever officially recorded (but keep my use of the word 'officially' in mind, for reasons to be revealed here shortly).

Native to South America and recognized to be the world's largest toad species, the cane toad was introduced into Australia during the 1930s in a bid to control sugar cane-devouring beetles here. Alarmingly, however, it ultimately proved itself as serious an ecological blight as its intended prey. This is due not only to its skin being toxic but also to various toxin-secreting glands on its back and especially to the pair of very sizeable parotoid glands sited on its warty skin's shoulders, which secrete a potent cardiac toxin called bufotoxin - this highly deleterious suite of secretions collectively causing anything attempting to eat one of these toads to die a swift and usually certain death, including Australia's various native (and mostly endangered) marsupial carnivores, and even creatures as large as goannas (monitor lizards). To make matters worse, this toad also actively preys upon the smaller marsupial carnivore species, such as the shrew-like marsupial mice.

Moreover, because of its very effective deterrent against potential attackers, the cane toad has no predators here, causing its numbers to swell out of all proportion and thereby posing an increasingly severe threat to this island continent's unique indigenous fauna.

A cane toad, with its lethal pair of shoulder-sited toxin-secreting parotoid glands clearly visible (© Froggydarb/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

A cane toad, with its lethal pair of shoulder-sited toxin-secreting parotoid glands clearly visible (© Froggydarb/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Having said that, in recent times one native Australian species, the black-necked ibis Threskiornis molucca, has seemingly conceived a remarkable means of side-stepping the cane toad's hitherto unassailable defence mechanism – these ibises have been seen throwing toads in the air, which distresses them, thus inducing them to release their skin glands' toxic secretions, after which the ibises wipe the toads on wet grass or rinse them in a water source, washing off the poison from the toads' skin, and then repeat the entire process, until the toads' glands and skin are eventually drained of toxin, after which the ibises swallow the toads whole, with no resulting ill effects.

Certain other canny avians, such as crows and hawks, have learned to flip the toads onto their back and then devour their internal organs, leaving their lethal shoulder and back glands untouched. Who said that birds are bird-brained?! More information on toad-tackling birds here.

Anyway, as noted above, the cane toad is officially the world's largest species of toad. Unofficially, however, there may be reason to question this assumption, judging at least from certain intriguing reports contained in the cryptozoological archives.

The native Indian peoples inhabiting various tropical valleys in the Chilean and Peruvian Andes frequently report the existence there of a greatly-feared, giant form of toad called the sapo de loma ('toad of the hills'). It is said to be deadly poisonous and capable of preying upon creatures as large as medium-sized birds and rodents.

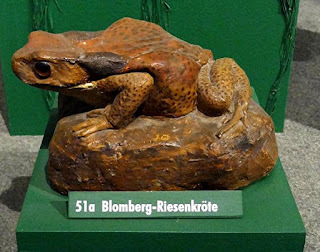

Taxiderm specimen of Blomberg's giant toad Bufo blombergi (© Markus Bühler)

Taxiderm specimen of Blomberg's giant toad Bufo blombergi (© Markus Bühler)

Science has yet to examine a sapo de loma, but as I have pointed out in my book The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals(2012) and its two predecessors (The New Zoo, 2002, and The Lost Ark, 1993), there is a major precedent for discovering batrachian behemoths in South America. Rolf Blomberg (1912-1996) was a Swedish explorer, photographer, and writer, and in 1950 he was instrumental in bringing to scientific attention a hitherto-undescribed species of giant toad native to southwestern Colombia. He achieved this significant feat by capturing a huge specimen there that he brought back with him to his home in neighbouring Ecuador, and which became the type specimen of this spectacular new species – duly dubbed Bufo blombergi in his honour a year later. Blomberg's giant toad (aka the Colombian giant toad) can attain a total snout-to-vent length of up to 10 in, which is greater even than that of the heavier, more massively-built cane toad.

Incidentally, German cryptozoological correspondent Markus Bühler has informed me that while browsing through a series of yearbooks from the 1970s for Stuttgart's Wilhelma Zoo, he noticed that the 1971 volume mentioned the chance birth at the zoo some years earlier of hybrids between a female B. blombergi and a male B. marinus. They were apparently indistinguishable from the paternal species, but exhibited unusually strong growth – no doubt a result of hybrid vigour. Bearing in mind that they were crossbreeds of the world's longest toad species and the world's largest toad species, it is a great pity that the book did not contain any additional information concerning them, because they must surely have had the potential to become veritable mega-toads!

In any event, mindful of the relatively belated scientific discovery of Blomberg's giant toad, it would be rash to rule out entirely the possibility that a comparable species still awaits discovery in remote, rarely-visited Andean valleys not too far to the south of the latter species' distribution range.

Moreover, there are also claims among the Mapuche people relating to a supposedly immense species of toad indigenous to various lakes, lagoons, and irrigation channels in southern Chile and southwestern Argentina. Known as the arumco ('big water frog') in Argentina and the vilú in Chile, it is said to measure up to 3 ft long. One such creature, dwelling in a lake, reputedly devoured a horse that was attempting to wade across, but whether this story is true or merely native folklore or hyperbole remains unresolved.

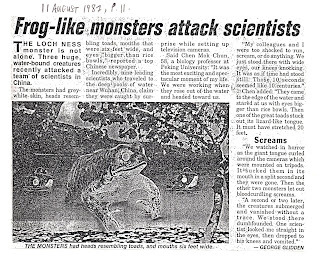

Unidentified newspaper article published on 11 August 1987, p. 11, regarding the mystery Wuhan giant toads (or frogs?)

–

please click picture to enlarge for reading purposes (source unknown to me despite many searches for information concerning this article – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Unidentified newspaper article published on 11 August 1987, p. 11, regarding the mystery Wuhan giant toads (or frogs?)

–

please click picture to enlarge for reading purposes (source unknown to me despite many searches for information concerning this article – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

However, it does remind me of a comparable report that emerged from China. A team of nine scientists from Peking (now Beijing) University, led by 58-year-old biologist Prof. Chen Mok Chun, travelled to some very large, deep mountain pools (one of which is named Bao Fung Lake) near Wuhan in China's Hubei Province during August 1987 in order to film the area and its wildlife. While setting up their television cameras, however, they were allegedly treated to an exhibition of local wildlife far beyond anything that even their wildest imaginations – or worst nightmares – could have conceived.

In full view of the scientists, three huge creatures supposedly rose up out of one of these pools and moved towards the pool's edge nearest to them. Their stunned eyewitnesses likened these grotesque monsters to giant toads or frogs, with greyish-white skins, mouths that were said to be about 6 ft wide, and eyes "bigger than rice bowls".

According to Prof. Chen, they silently watched the scientists for a short time. Then one of them opened its huge mouth and swiftly extended an enormous tongue, estimated at 20 ft long, which it wrapped around the cameras on tripods. As it promptly engulfed the tripods, its two companions let forth some eldritch screams, and then all three monsters submerged, disappearing from view. The delayed-shock reaction experienced by the scientists was so great that one of them dropped to his knees and was physically sick, according to Chinese reports, summarised in various overseas media accounts, including an unidentified American newspaper report included here (if anyone can identify its source, please let me know, thanks!)

This incident seems so utterly incredible that one would surely feel justified in dismissing it entirely as a hoax – were it not for the fact that the eyewitnesses in question were all trained scientists, including a major name in Chinese biological research, and all from the country's leading university. Moreover, reports of such creatures being sighted in this same locality by local fishermen date back at least as far as 1962.

Finally: included here for no reason whatsoever other than I happen to like it is a bizarre sculpture from the late 1800s of a hook-beaked, warty-skinned, rabbit-eared frog – or toad! (© Markus Bühler)

Finally: included here for no reason whatsoever other than I happen to like it is a bizarre sculpture from the late 1800s of a hook-beaked, warty-skinned, rabbit-eared frog – or toad! (© Markus Bühler)

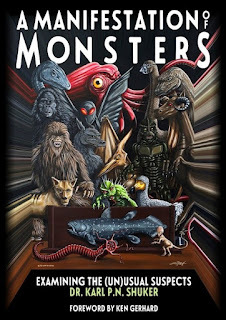

For more information concerning mega-toads, not to mention mega-frogs too (and click herefor one such example of the latter category of amphibian cryptid as documented by me on ShukerNature), be sure to check out my book A Manifestation of Monsters.

January 4, 2023

STREWTH! IS STRUTHIO THE AUSSIE SPINIFEX MAN?

Vintage illustration from 1792 of a male specimen of Struthio camelus, the African ostrich – but is this species alive and well and living in Australia too? (public domain)

Vintage illustration from 1792 of a male specimen of Struthio camelus, the African ostrich – but is this species alive and well and living in Australia too? (public domain)

During summer 1970, dingo hunter Peter Muir found and photographed some strange two-toed tracks in the spinifex (a spiny-seed grass) desert area near Laverton, Western Australia. Local aboriginals claimed that they were from an ogre-like monster – the tjangara or spinifex man.

Emu (© Donald Hobern/Wikipedia

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Emu (© Donald Hobern/Wikipedia

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Scientists initially assumed that these were merely tracks of the common Australian emu Dromaius novaehollandiae, but swiftly retracted this view – because emus leave three-toed versions. Only one known creature produces two-toed tracks like those at Laverton – Struthio camelus, the African ostrich!

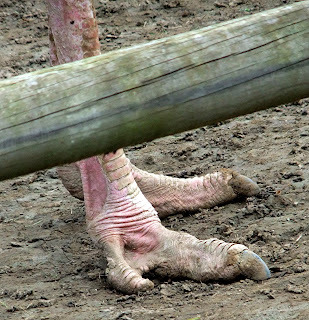

Close-up of ostrich foot showing its fundamentally two-toed format – its very small third toe is too short to leave any noticeable impression in footprints (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Close-up of ostrich foot showing its fundamentally two-toed format – its very small third toe is too short to leave any noticeable impression in footprints (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Yet the concept of ostriches living wild in Australia is by no means ludicrous – far from it. Small populations of feral (run-wild) ostriches still persist north of Adelaide, South Australia, for instance, descended from specimens released by ostrich farmers after World War I, when the feather market collapsed.

Ostriches were formerly maintained in captivity on Australian farms for their once highly-valued plumes (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Ostriches were formerly maintained in captivity on Australian farms for their once highly-valued plumes (© Dr Karl Shuker)

As the ostrich is a desert-hardy bird that can travel great distances in short periods of time, in 1971 veteran American zoologist and cryptozoologist Ivan T. Sanderson suggested in a short Pursuit article that some ex-farm specimens may not only have survived and bred but also have discreetly extended their range across the intervening desertlands into Western Australia, and thence to Laverton. (Incidentally, it is known that ostriches were released in Western Australia before 1912, but these 'officially' died out without establishing a population.)

Female ostrich (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Female ostrich (© Dr Karl Shuker)

This would offer a plausible explanation for the mystery of the two-toed tracks and their unseen originator(s) – aptly dubbed by Australian wags 'the abominable spinifex man'. Indeed, if the Laverton environs were not so sparsely populated, the existence of ostriches there may have been confirmed by now.

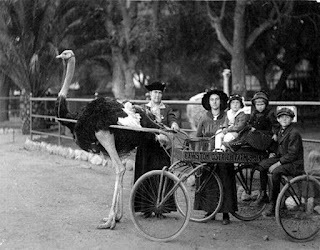

Vintage curio photograph of an ostrich-drawn cart (public domain)

Vintage curio photograph of an ostrich-drawn cart (public domain)

This ShukerNature article is excerpted from my book The Beasts That Hide From Man(2003).

December 24, 2022

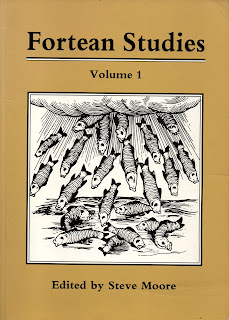

LISTING THE FULL CONTENTS FOR FORTEAN STUDIES - THE ERSTWHILE SISTER SCHOLARLY JOURNAL OF FORTEAN TIMES

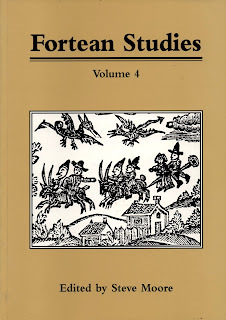

Front covers of Vols 1-4 of Fortean Studies(© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Front covers of Vols 1-4 of Fortean Studies(© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

I recently received an enquiry from Facebook follower Mike Robe, asking if I knew of anywhere online that contained a complete list of contents for each of the seven published volumes of Fortean Studies – the scholarly journal published annually-ish from 1994 to 2001 inclusive by John Brown Publishing of London for the long-running monthly British magazine Fortean Times, which is famously devoted to all matters of a mysterious, inexplicable, and truly Fortean nature. After spending some time checking online, I was very surprised to discover that such listings were indeed conspicuous only by their apparent absence there.

Having been fortunate enough to contribute to virtually every Fortean Studies volume an article of my own (each of which I have subsequently expanded, updated, and included as a chapter in one of my books), I'm very familiar with this journal's contents and their outstanding scholarly merit, collectively constituting a very sizeable corpus of in-depth, extensively-researched contributions too lengthy and specialized for publication in Fortean Times, thus explaining why Fortean Studies was established. It's a great pity that it ceased publication after just seven volumes, but at least many copies of each of these still exist, offering an authoritative, highly-informative, fascinating read for everyone interested in Fortean phenomena.

Consequently, as a response both to Mike's enquiry and to what I feel to be a necessity that the contents of Fortean Studies should, very deservedly, be brought to the widespread attention of online readers, I am presenting herewith a series of scans of the front cover and, on the back cover, the list of contents for each Fortean Studiesvolume from my own library.

NB – Please note that Vol. 1 does contain an article of mine, 'A Belfy of Crypto-Bats', positioned directly after Michel Raynal's giant octopus article, but for some unexplained reason it was omitted from the list of contents.

Fortean Studies, Volume 1, 1994 – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Fortean Studies, Volume 1, 1994 – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Fortean Studies

, Volume 2, 1995 – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Fortean Studies

, Volume 2, 1995 – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Fortean Studies

, Volume 3, 1996 – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Fortean Studies

, Volume 3, 1996 – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Fortean Studies

, Volume 4, 1998 [for 1997] – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Fortean Studies

, Volume 4, 1998 [for 1997] – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

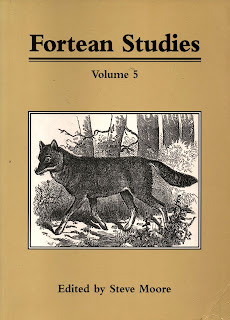

Fortean Studies

, Volume 5, 1998 – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Fortean Studies

, Volume 5, 1998 – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

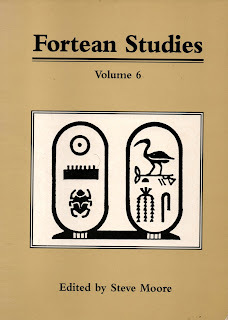

Fortean Studies

, Volume 6, 1999 – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Fortean Studies

, Volume 6, 1999 – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

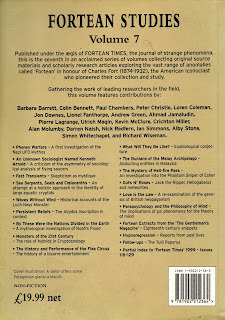

Fortean Studies

, Volume 7, 2001 – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Fortean Studies

, Volume 7, 2001 – click to expand for reading purposes (© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Exceptional pressures of work meant that I was unable to contribute an article to Vol. 6, whereas the article on winged cats that I was planning for Vol. 7 proved so arduous in terms of length and required research that I couldn't complete it in time to meet its publication deadline (it finally appeared almost a decade later, in my book Dr Shuker's Casebook). Nevertheless, I did still contribute to Vol. 7, inasmuch as I was nominated as a reviewer by its editors to evaluate Darren Naish's sea serpent article in manuscript form and offer my opinion as to whether it should be published in Fortean Studies. After reading it, I stated that it should be, so it was.

Second-hand copies of Fortean Studies still appear for sale quite frequently on online auction and bookstore sites, but such listings rarely provide full details of these publications' contents. So I hope that this present ShukerNature post will be of benefit to readers who are thinking of purchasing any Fortean Studies volumes but until now have been deterred from doing so by being uncertain of what they contain.

I wish to thank most sincerely my longstanding friend and fellow cryptozoology enthusiast Mike Playfair for very kindly gifting me his spare copy of Fortean Studies Vol. 7 after learning that this was the one volume that I hadn't been able to track down.

I also wish to pay tribute to the memory of the late Steve Moore, who edited all but that final, seventh volume, for encouraging me to contribute to Fortean Studiesand also for being another longstanding friend of mine within the Fortean community.

Front covers of Vols 5-7 of Fortean Studies(© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Front covers of Vols 5-7 of Fortean Studies(© Fortean Times/John Brown Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

December 23, 2022

PERUVIAN BANDICOOTS, UNDISCOVERED TAPIRS, ZEBRA-STRIPED CARROT CREATURES, AND OTHER NEOTROPICAL NOVELTIES, COURTESY OF LEQUANDA & THI��BAUT

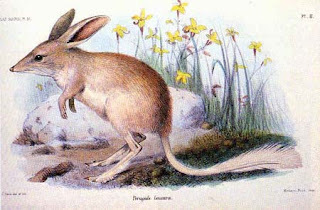

Isthis a bilby I see before me ��� in Peru?? (public domain)

Isthis a bilby I see before me ��� in Peru?? (public domain)

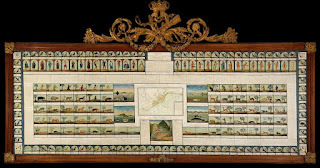

In my previous ShukerNature blog article(click hereto access it), I documented two unexpected creatures depicted in a magnificentmural-format pictorial encyclopaedia entitled Quadro de Historia Natural, Civil y Geografica del Reyno del Peru('Painting of the Natural, Civil and Geographical History of the Kingdom ofPeru'), or QHNCGRP for convenience hereafterin this present article. Consisting of numerous miniature oil paintings andaccompanying text on a wood panel, it measures a very impressive 128x 45.25 inches (325 x 115 cm).

Completed in Madrid, Spain, in 1799 andnow on display at the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales in Madrid (Spain'snational museum of natural history), which has produced an exquisite, lavishly-illustrated website devoted specificallyto it (click here),QHNCGRP was authored by Basque-bornbut (for three decades) Peru-based scholar Jos�� Ignacio Lequanda, whocommissioned French artist Louis Thi��baut to produce the 194 paintingsillustrating it. As noted above, most of these are miniatures, with tiny butvoluminous text by Lequanda accompanying all of the 160 miniatures depictingfauna and flora of Peru or its South American environs.

The vast majority of these miniaturesdepict readily-recognisable Neotropical species, including a large spottedrodent named the paca, a South American zorro or 'fox' (actually a species of Dusicyon canid), an otter, tapir,manatee, various monkeys, trumpeter bird, cock of the rock, spoonbill,hummingbird, Humboldt's penguin, skunk, caiman, giant anteater, fulgorid lantern-fly,llama, vicuna, armadillos, coati, and opossum, to mention but a few.

Viewof QHNCGRP in its entirety ��� click toenlarge for viewing purposes (�� Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales ���reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis foreducational/review purposes only)

Viewof QHNCGRP in its entirety ��� click toenlarge for viewing purposes (�� Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales ���reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis foreducational/review purposes only)

Also present, however, are certaindecidedly mystifying zoological portraits, such as that of a dramaticallyout-of-place Madagascan black-and-white ruffed lemur and one of a putativeliving ground sloth, both of which I documented in my previous QHNCGRP article.

Since writing that, I have been payingfurther close attention to this marvelous pictorial menagerie, and I've spottedseveral additional examples included within it that are nothing if not curiousor controversial, for various differing but equally interesting reasons. Sohere they are ��� make of them what you will!

Take, for instance, the very distinctivecreature portrayed in the QHNCGRPminiature that opens this present ShukerNature article. Whereas I am not awareof any South American mammal matching its morphology (Lequanda claimed it to be a vizcacha, and others have suggested the latter rodent's relative the chinchilla, but these bear little ��� in the case of the chinchilla ��� or no ��� in the case of the vizcacha ��� resemblance to it, I am aware that it does beara remarkable similarity to a certain species of exclusively Australianmarsupial. Namely, the lesser bilby (aka lesser rabbit-eared bandicoot) Macrotis leucura.

Mysterybig-eared, long-snouted, plume-tailed QHNCGRPmammal (above) and a painting of a lesser bilby from English zoologist OldfieldThomas's Catalogue of the Monotremes andMarsupials in the British Museum (Natural History) (below) (public domain)

Mysterybig-eared, long-snouted, plume-tailed QHNCGRPmammal (above) and a painting of a lesser bilby from English zoologist OldfieldThomas's Catalogue of the Monotremes andMarsupials in the British Museum (Natural History) (below) (public domain)

Certainly, its long snout, lengthy plumedtail, and very sizeable ears all correspond very closely to those of the latterspecies. True, its forelimbs are much the same size as its hind ones, whereasthose of the lesser bilby are shorter, and its fur is white rather than brownlike the bilby's. However, the limb discrepancy may simply be an error onThi��baut's part, especially if his subject's preserved skin had becomedistorted via shrinkage. Moreover, preserved skins frequently blanch if exposedtoo long to light (the taxiderm thylacine that was on public display inLondon's Natural History Museum when I visited in 2014, for example, was sofaded, predominantly cream in colour all over, that its diagnostic stripes hadvanished).

Deriving its English name from its verylarge, slender, rabbit-like ears, and characterized by its tail's long whitehairy plume, the lesser bilby was once native to the deserts of centralAustralia, but has not been conclusively sighted since the 1950s, so is nowdeemed extinct. Back when QHNCGRP wascreated, however, it was still in existence, with preserved specimens inmuseums.

As apparently happened with the ruffedlemur, is it possible, therefore, that Lequanda and/or Thi��baut saw a museum specimenof the lesser bilby at Madrid's celebrated Royal Natural History Cabinet(founded in 1771, opened to the public in 1776, and whose contents were veryfamiliar to Lequanda), or even elsewhere, and mistakenly assumed that it was aNeotropical species? Or might Thi��baut have based his miniature upon somepre-existing artwork by another artist? There is a notable QHNCGRP���linked precedent for this latter possibility.

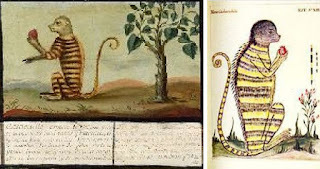

Thi��baut'szebra-striped QHNCGRP mystery monkey(top left), Compa��on's earlier artwork upon which Thi��baut's was based (top right),and a South American tree porcupine (below) (public domain / public domain / (��Eric Kilby/Wikipedia ���

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Thi��baut'szebra-striped QHNCGRP mystery monkey(top left), Compa��on's earlier artwork upon which Thi��baut's was based (top right),and a South American tree porcupine (below) (public domain / public domain / (��Eric Kilby/Wikipedia ���

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

One of the several monkeys depicted asminiatures in QHNCGRP by Thi��baut isthe extraordinary-looking striped example shown above. Its bold zebra-like bodyand limb markings instantly set it apart from any currently-known monkeyspecies, as does the mid-dorsal row of spines running down its back. These arealso alluded to by Lequanda, in his accompanying text. He referred to this fascinatingfasciated creature as a casacuillo, and also mentioned that it lived upon fruit.

Rather than basing his illustration of thiscasacuillo upon first-hand observations of a living or preserved animal,however, Thi��baut used as his inspiration a pre-existing 18th-Centuryillustration. Namely, a water-colour prepared some years earlier with 1,410others for inclusion in the Codex Mart��nezCompa��on, a sumptuous nine-volume manuscript made by Baltasar Jaime Mart��nezCompa��on, Bishop of Trujillo, Peru. This water-colour is also shown here, forcomparison purposes alongside Thi��baut's oil painting.

Moreover, according to writer CarmenMart��nez, writing in an online article from June 2021 devoted to QHNCGRP (click hereto access it), this creature is not a monkey at all, but is instead a SouthAmerican tree porcupine or coendou, of which there are many species, allsporting a prehensile tail. However, to me it looks no more like a tree porcupinethan it does a monkey! Coendous are not striped and their fine spines arepresent profusely over their entire body, not merely along their back. So I amunconvinced by this identification.

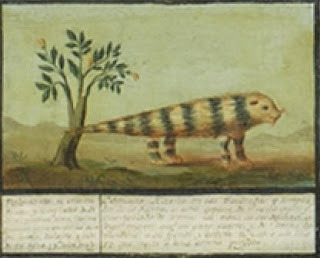

Astriped carrot on legs!! Another of Tri��baut's bemusing mystery beasts includedby him in QHNCGRP (public domain)

Astriped carrot on legs!! Another of Tri��baut's bemusing mystery beasts includedby him in QHNCGRP (public domain)

And speaking of zebra-patterned mysterybeasts depicted in QHNCGRP, what arewe to make of the example shown above? It looks for all the world like a stripedcarrot on legs! It seems to be furry, eared, and whiskered, and is included in the left-hand block of 30mammal miniatures (according to Lequanda, moreover, it is, once again, a coendou!), so we must assume that it is indeed mammalian ��� or shouldwe?

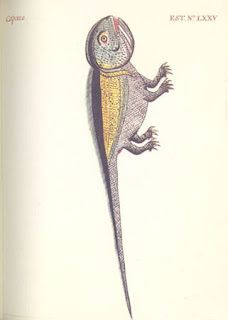

After all, also included in this sameblock of miniatures is the following bizarre beast, popularly if improbably(?)deemed to be a portrait of an iguana according to various sources consulted byme

Yet this latter beast is itself a majormystery. For it seems to possess a stiff pointed tail wholly unlike the highlyflexible tail of an iguana, as well as long curved fangs emerging from itsjaws, and what looks like a pair of wings pressed tightly against its flanks! Apparently, like the striped monkey/coendou illustration, Thi��baut based his miniature upon one from the Codex Mart��nezCompa��on that was labelled as an iguana. Really??

Asupposed iguana depiction by Thi��baut in QHNCGRP(above) and the original version in the Codex (below) (public domain)

Asupposed iguana depiction by Thi��baut in QHNCGRP(above) and the original version in the Codex (below) (public domain)

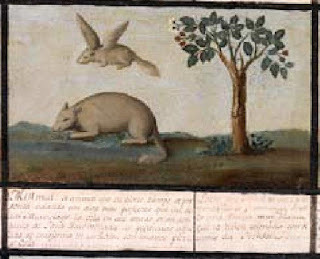

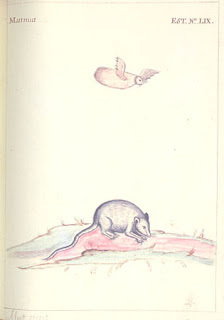

Most improbable of all, however, mustsurely be the next example presented here. What on earth (or in the air!) isthis extraordinary squirrel-like entity that sports not only two pairs of limbsand a bushy tail but also a pair of wings ��� and which are clearly functional,given that Thi��baut has portrayed it flying above a somewhat larger, rodent-likemammal in the same miniature?

Might it be the inaccurate result ofThi��baut painting not from direct observation of some physical specimen, butinstead merely from a verbal description of a flying squirrel? True, the name ofthese rodents is something of a misnomer, seeing that they become airborne notwith the assistance of wings but instead via a pair of gliding membranes (patagia),linking their wrist and ankle on each side of their body. But if a verbaldescription of such a creature does not make this distinction clear to anartist seeking to depict it, the result might well be an illustration of asquirrel-like creature boasting a pair of bona fide wings.

Yet even if that were true, there is stilla fundamental problem in applying it as an explanation for this aerial anomaly asportrayed here, because although flying squirrels are widely distributed inNorth America, they do not occur anywhere in South America. So why wouldThi��baut have depicted one in QHNCGRP?Yet another instance of someone wrongly assuming that a given creature isNeotropical when it definitely is not? Having said that, Thi��baut's illustration is yet again a copy of one from the Codex Mart��nezCompa��on, but in that version the flying entity looks far more like a bird than a mammal, so why did Thi��baut convert it into one in his copied version? Conversely, at least according to Lequanda's accompanying description of it in QHNCGRP, it is indeed a rodent with wings, and is referred to by him as a mutmut. All very strange!

Thi��baut'sbewildering winged squirrel in QHNCGRP(above) and the original bird-like version in the Codex (below) (public domain)

Thi��baut'sbewildering winged squirrel in QHNCGRP(above) and the original bird-like version in the Codex (below) (public domain)

My concern with the ostensiblyunidentifiable mystery creatures from QHNCGRPdocumented by me here is that, as already noted, most of the animals depictedin it by Thi��baut are readily recognisable. So as those were all accuratelyrepresented by him, why should the mystery beasts here not be too, unless he was indulging in some sly humour at Lequanda's expense, perhaps? Yet if they are accurate representations, why can wenot identify them?

Might at least some of them not havearisen through misapprehensions regarding the origins of specimens utilized assubjects, or even as a result of poor verbal descriptions of such, but insteadbe bona fide native Neotropical species that have become extinct before everbecoming known to European scientists, so their morphological appearance iswholly unfamiliar to us?

The last anomalous animal to beconsidered here may provide key evidence that some of Thi��baut's miniaturesdepict significant creatures that were still unknown to science at the timewhen he depicted them.

Thesupposed lowland tapir depicted in QHNCGRP(public domain).

Thesupposed lowland tapir depicted in QHNCGRP(public domain).

Just a few hours after I posted myprevious QHNCGRP-themed ShukerNaturearticle, on 22 December 2022, I received a very interesting, thought-provokingcomment from a reader with the Google username Andrew, and which I duly postedbeneath my article. It concerns the QHNCGRPminiature of what is officially assumed to be a specimen of the lowland (Brazilian)tapir Tapirus terrestris, the largestspecies of native mammal known to be alive today in South America, andoccurring widely here, including in Peru. Here is Andrew's comment:

Thi��baut's depiction of thetapir looks like it could have been based on descriptions of thethen-undiscovered mountain tapir, rather than the lowland species. It has nocrest, its coat is almost black with a slight chestnut tint, and it seems to havewhite lips.

Smaller and darker in colour than thelowland tapir, the mountain tapir T.pinchaque is a very distinctive species that is indeed uncrested andwhite-lipped. It is also noticeably woolly, and looking at the tapir miniature inclose-up its body surface does appear to be hairy. Moreover, of particularhistorical note is that this species, which is indeed native to Peru (occurringin its far north's montane cloud forests), was not formally described byscience until 1829 ��� 30 years after the creation of QHNCGRP.

A lowlandtapir (top) and a mountain tapir (bottom) (�� Dr Karl Shuker / (�� RichardSifry/Wikipedia ���

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

A lowlandtapir (top) and a mountain tapir (bottom) (�� Dr Karl Shuker / (�� RichardSifry/Wikipedia ���

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

In short, if the tapir miniature in QHNCGRP actually depicts a mountaintapir rather than a lowland tapir, this means that Thi��baut had portrayed amajor mammalian species three decades before its official discovery. This in turn begs the question: what specimenwas utilized by Thi��baut as the subject for his illustration?

Whichever it was, and wherever it was,its taxonomic significance as representing a dramatic new species had clearlynot been recognized or appreciated by scientists of the day.

As I have revealed many times in my trioof books on new and rediscovered animals, this is a sad situation that has occurredcountless times down through the centuries, with obscure museum specimens havingbeen long overlooked before belatedly receiving serious attention, only forthem then to be revealed as extraordinary new species whose existence had neverpreviously even been suspected, let alone confirmed. So the potential exampledocumented above has plenty of precedents, that's for certain!

Mythree books on new and rediscovered animals (�� Dr KarlShuker/HarperCollins/Stratus Publishing/Coachwhip Publications)

Mythree books on new and rediscovered animals (�� Dr KarlShuker/HarperCollins/Stratus Publishing/Coachwhip Publications)

Karl Shuker's Blog

- Karl Shuker's profile

- 45 followers