Karl Shuker's Blog, page 8

January 29, 2022

CAUGHT ON THE HOP BY PHANTOM KANGAROOS AND OTHER OUT-OF-PLACE MYSTERY MACROPODS: Part 3 – FURTHER IDENTITIES, AND FURTHER AFIELD

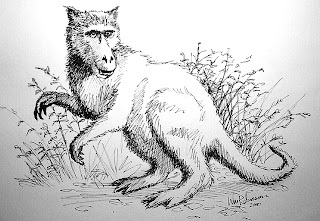

Artistic representation of a devil monkey – is North America home to an undiscovered species of macropod, or macropod-like mystery beast? (© William M. Rebsamen)

Artistic representation of a devil monkey – is North America home to an undiscovered species of macropod, or macropod-like mystery beast? (© William M. Rebsamen)

For the cryptozoologist, the most perplexing of all American phantom kangaroo reports (click hereand hereto read a selection of these as documented in Parts 1 and 2 of this three-part ShukerNature article) must surely be those attributed to the Jersey devil. For although several accounts concerning the latter mystery beast allude to creatures bearing a superficial similarity to genuine macropods, such beasts additionally possess certain features that are anything but characteristic of Australia's most famous denizens. Such features include a tendency to emit bloodcurdling screams, as well as possessing hooves, horns, and wings.

SHRIEKS AND SCREAMS

The things with wings and the horrors with horns plus hooves evidently have nothing to do with kangaroos, phantom or otherwise, and therefore can be omitted from further discussion here forthwith. The remainder, conversely, appear to differ from typical macropods only with respect to their spine-chilling shrieks. In actual fact, America possesses certain known creatures famed for their ability to produce these very same sounds.

The two most notable species are the great horned owl Bubo virginianus and the puma Puma concolor. As it happens, although hunters and trackers had frequently reported personal observations of pumas producing these remarkably loud and eerie sounds, they were generally disbelieved by scientists – until official observations of such activity were recorded from various zoo specimens, as documented by C.A.W. Guggisberg in his comprehensive book Wild Cats of the World (1975) and subsequently expanded upon by me in my own, first book Mystery Cats of the World (1989).

Puma (top) and great horned owl (bottom) (public domain / Patrick Coin/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)

Puma (top) and great horned owl (bottom) (public domain / Patrick Coin/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

) Thus it is probable that at least some reports of poorly-observed screaming critters can be explained in this way. Such a solution cannot, however, be applied to those reports in which the witness has distinctly observed a kangaroo-like creature shrieking at close quarters. Moreover, any ventriloquist puma or owl working in conjunction with a kangaroo stooge is much more likely to be found employed upon a Saturday morning cartoon show than wandering through America's countryside!

Evidently, the riddle of the screeching kangaroos will remain unresolved until a specimen can actually be obtained. However, there is one final mystery macropod identity (offered by several writers in the past as at least a theoretical possibility) that has so far not been investigated here, but which is particularly pertinent to this more aberrant, shrieking category of phantom kangaroo (because due to their weird vocals these latter cryptids cannot be so readily considered as straightforward escapees of known macropod species). The possibility in question, albeit exceedingly remote and radical, is that America harbours an unknown, indigenous species of macropod or macropod-like creature. Furthermore, such a form could actually have arisen via two completely different means.

THE CHATATA BIPED AND THE DEVIL MONKEY

Although today represented only by the didelphids (true opossums), caenolestids (rat/shrew opossums), plus a lone surviving species of microbiotheriid (monito del monte), and existing predominantly in Central and South America (a single didelphid species occurs as far north as the U.S.A.), in earlier times the marsupials were a very diverse group throughout the New World. South America in particular was once home to a number of sizeable forms, including the pouched sabre-tooth Thylacosmilusand the wolf-like borhyaenids that belonged to a now entirely extinct taxonomic order whose members were known as sparassodonts and were only very distantly related to all other South American marsupials.

Interestingly, by morphologically paralleling the placental wolves, the borhyaenids also called to mind Australasia's marsupial wolves, the thylacinids (of which the now 'officially' extinct Tasmanian wolf Thylacinus cynocephalus is the only modern-day representative). Indeed, these two latter marsupial groups were once deemed to be closely related. Following more recent research, however, it is nowadays recognised that this is not the case at all – their notable outward similarity arose instead through convergent evolution, due to their occupancy of the same ecological niche upon their respective continents.

If the Americas' pouched mammalian clan could produce a parallel to the Australasian marsupial wolves, could it also have produced a parallel to the Australasian macropods – and one, moreover, which (unlike the borhyaenids) has actually survived to the present day, in North America? Sadly, however, all of the scientific evidence currently available stands firmly against this possibility. Firstly, excluding only a few surviving didelphids all of North America's marsupials died out much earlier (and were much less specialised) than those of the New World's southern continent. So if an indigenous American macropod-like form had evolved and has possibly survived into the present day, one would expect sightings from South or even Central America rather than from the northern continent. Furthermore, no fossil remains of kangaroo-like beasts have ever been recorded from the Americas (known New World fossil marsupials have been carnivorous or insectivorous rather than herbivorous).

Holding some grapes, a Virginia opossum Didelphis virginiana, North America's only known living marsupial species (public domain)

Holding some grapes, a Virginia opossum Didelphis virginiana, North America's only known living marsupial species (public domain)

Worth noting for comparison purposes, however, is that despite the absence of geologically-recent coelacanth fossils, two living species do indeed exist. Consequently, an absence of recent fossils of a given animal group does not prove conclusively that no living representative of this group survives. Moreover, one discovery hasoccurred that may have particular bearing upon the veracity of this most intriguing (albeit highly unlikely) mystery macropod identity.

On 9 November 1891, New York City historian Prof. Albert Leighton Rawson published in the Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences a short paper entitled 'The Ancient Inscription on a Wall at Chatata, Tennessee'. In this, Rawson described a mysterious wall-like structure lately excavated near Cleveland, in Bradley County, which was composed of red sandstone that bore many hundreds of inscribed symbols of unknown meaning and origin. Moreover, there was also evidence to suggest that attempts had subsequently been made to obliterate them, by covering them with cement and placing on top of this a layer of stone – all very strange.

Strangest of all, however, was the fact that certain of the symbols took the form of unusual animal types, not clearly identifiable with known American species. Of these, the most perplexing must surely be the very distinctive creature whose inscribed form is replicated here:

Exact reproduction of the inscribed form of the mystifying bipedal beast present on the Chatata Wall (public domain)

Exact reproduction of the inscribed form of the mystifying bipedal beast present on the Chatata Wall (public domain)

For whereas certainly not matching any 'official' New World animal, it closely corresponds with an 'unofficial' form – the American phantom kangaroo. Unlike known macropods, of course, the Chatata biped sports a beard-like structure hanging from its lower jaw, plus strange-looking hind feet. Such differences, however, could simply be due to artistic style. Also, if the Americas have indeed yielded their own macropod form, one would expect at least slight differences from the Australasian version – another reason for the 'beard' and feet?

The specific age of the inscriptions is unknown, but they would certainly seem to predate very considerably the last 200 years or so – when Australasian macropods first began to arrive in America bound for zoos, sideshow, and circuses, and from which escapees could subsequently infiltrate America's countryside.

Of course the Chatata biped may simply be a beast created by the inscriber's imagination. Nevertheless, is it not curious that it bears so close a resemblance to one of America's most puzzling modern-day mystery creatures, the phantom kangaroo? Tragically, however, no direct investigations of this carving or any others on the Chatata Wall can currently be undertaken, because, incredibly, the wall's exact location is no longer known! There is also a much-debated theory that its inscriptions may actually be nothing more than the casual, non-coordinated product of natural geological or palaeontological phenomena, but I cannot in any way comprehend how such precise, well-delineated forms could have been created by such random means.

Artistic reconstruction of the possible appearance of a devil monkey, based upon eyewitness descriptions (© William M. Rebsamen)

Artistic reconstruction of the possible appearance of a devil monkey, based upon eyewitness descriptions (© William M. Rebsamen)

More than 20 years after I wrote the original version of this article (back in the mid-1980s), a new and very different but no less intriguing cryptozoological connection to America's phantom kangaroos was postulated – this time by Loren Coleman and fellow American mysteries researcher Patrick Huyghe in their book The Field Guide to Bigfoot, Yeti, and Other Mystery Primates Worldwide (1999). Even though I have otherwise largely refrained from including updates, this highly intriguing identity certainly deserves mention here.

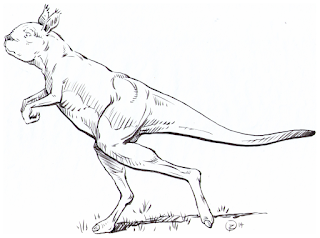

They proposed that at least some of America's reported mystery macropods are not macropods at all but actually constitute an undiscovered species of indigenous primate, a giant simian to be precise, that Coleman and another of his co-researchers, Mark A. Hall, have dubbed the devil monkey. Here is how Coleman and Huyghe described this postulated cryptid in their book:

They appear to be a kind of giant baboon that moves by saltation, leaping as do kangaroos – and are often mistaken for them. Due to their size [standing up to 5 ft tall according to a reconstruction of this cryptid's possible appearance included alongside its verbal description] and means of locomotion, they have evolved a large flat foot with three rounded toes. Immature Devil Monkeys resemble marsupials such as wallabies due to convergent evolution but this similarity diminishes as they mature.

A fascinating if entirely speculative proposal, because as yet there is no known fossil evidence to confirm the prior existence of any type of endemic primate in continental North America (other than our own species in modern times, of course), thereby reducing the likelihood that any such creatures exist here today.]

A more baboon-like interpretation of the devil monkey's possible appearance, should it actually exist (© William M. Rebsamen)

A more baboon-like interpretation of the devil monkey's possible appearance, should it actually exist (© William M. Rebsamen)

OAHU'S ROCK WALLABIES

The second way in which America could possess its very own, separate macropod form can be illustrated by the startling case of the distinctive form of rock wallaby unique to the Hawaiian island of Oahu. As noted in 1982 within a Science Digest news report, a single pair of Australian brush-tailed rock wallabies Petrogale penicillatus escaped from a zoo on Oahu in 1916. They were never caught, and subsequently reproduced in the wild, their offspring in turn mating amongst themselves, until a sizeable population of several hundred wallabies was established (although this has since declined to a present-day total of only 40 or so specimens).

Furthermore, in the early 1980s, when studying these most unusual additions to the Oahu fauna, American biologist Dr James Lazell claimed that they now differed so considerably both in body size and in colouration from their original Antipodean ancestors that they actually appeared to have evolved into a totally separate subspecies – unique to Oahu. Such rapid evolutionary divergence from the original form (less than 60 years in the case of the Oahu wallabies) is particularly common amongst very small populations of creatures isolated from all other intraspecific individuals – a phenomenon termed genetic drift. Furthermore, as Lazell noted in Science Digest, dramatic deviations will occur if the original organisms possess any marked genetic irregularities.

Brush-tailed rock wallabies (© Mark Hodgins and Doug Beckers/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Brush-tailed rock wallabies (© Mark Hodgins and Doug Beckers/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

[It should be pointed out, however, that a detailed molecular genetic analysis of the Oahu wallaby population conducted by Drs Mark D.B. Eldridge and Teena L. Browning, and published by the Journal of Mammalogy in 2002, refuted previous suggestions that these Hawaiian specimens now constituted a separate taxon.]

If, as seems probable, many of the reported 'normal' macropods sighted across America are descendants of original escapees that survived and multiplied in the wild, might it be possible that at least some of these have evolved (or are evolving) into separate taxa from their captive ancestors? In other words, could America genuinely possess its own indigenous macropod form, albeit of accelerated modern-day rather than traditional prehistoric evolutionary origin? It is to be hoped that whenever living macropods are captured in the wilds of North America, precise genetic and protein analyses will be undertaken to discover conclusively their taxonomic identity and reveal whether such an exciting phenomenon is indeed occurring here.

NATURALISED WALLABIES IN BRITAIN

This whole subject also has great bearing upon creatures far closer to home for me – namely, within the British Isles. For it is well known that established populations of naturalised Bennett's wallaby Notamacropus rufogriseus officially exist in Britain.

As detailed by Sir Christopher Lever in his definitive book The Naturalised Animals of the British Isles (1977), one such population was long located within heather moorland, scrub, and woodlands in the Peak District of Derbyshire and Staffordshire, England, descended from five macropod escapees from a private zoo near Leek during World War II. Sadly, however, this population seems nowadays to have all but died out, due to a succession of harsh winters, although occasional sightings of single specimens are still reported here.

A shy Bennett's wallaby (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A shy Bennett's wallaby (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Another documented British wallaby population exists in the St Leonard's Forest and Worth Forest area south of Crawley New Town in northern Sussex, England, and may have been similarly established by wartime escapees, this time from Leonardslee Park near Horsham. There is even a famous wallaby population on Inchconnachan, one of the islands in Scotland's Loch Lomond. These are descended from some specimens that were introduced there during the 1940s by Lady Arran Colquhoun, and Inchconnachan itself is popularly referred to colloquially as Wallaby Island.

In view of the Oahu wallabies, is it conceivable that in time to come these British naturalised wallabies will evolve into at least a phenotypically-distinct form, visually distinguishable from their escapee ancestors? Truly a most stimulating thought, and one made even more tantalising by the fact that prior to their population crash the Peak District wallabies had already yielded some individuals differing markedly in colouration from the original escapees. Moreover, in recent years a number of albino wallabies have been reported in the wild from various disparate localities across Great Britain.

An albino Bennett's wallaby (© Dr Karl Shuker)

An albino Bennett's wallaby (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Intriguingly, reports have also been filed involving British sightings of macropods in locations other than those officially confirmed to be occupied by populations. In some cases, such reports are known to have been caused by lone escapees from captivity nearby; in others, an individual from one of the official naturalised populations may simply have strayed elsewhere.

However, a fair few reports exist that cannot be satisfactorily explained by either of these answers, leading to the prospect that other, currently unconfirmed populations of escapee descendants may exist in Britain. Take, for example, the Oxfordshire outbreak of August 1985:

ELUDING CAPTURE

On 14 August 1985, student Greg Caswell gave chase to a wallaby spotted bounding along the Benson to Crowmarsh road in south Oxfordshire, England, while he was driving home late that evening, but he didn't catch it. Although two or three wallabies were known to have escaped before Christmas 1984 from the McAlpine estate near Fawley (about 8 miles from Crowmarsh), these were all thought to have been killed in road accidents (Fortean Times, winter 1985). On 24 or 25 August, a drowned wallaby was discovered in a private pool at Crowmarsh – possibly the individual that had eluded capture by Greg just over a week earlier (Oxford Mail, 28 August).

A few days before that find, and at least 30 miles north-west of Oxford, Julia Brooks of Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire, had been surprised to observe a wallaby in her garden eating food scraps put out for the birds; and on 25 August, workers on the Cornbury Park estate (about 15 miles southeast of Chipping Campden) sighted a macropod in nearby fields, but they claimed that it was 5-6 ft tall, grey-coloured, and was identified emphatically by them as a kangaroo, not a wallaby (Fortean Times, winter 1985).

Might it have been an eastern grey kangaroo Macropus giganteus, like this individual? (© Danielle Langlois/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Might it have been an eastern grey kangaroo Macropus giganteus, like this individual? (© Danielle Langlois/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Thus it seems that this latter, much larger beast was not the same macropod that Brooks had spied. On 17 September, the Oxford Mail reported that Police Constable Jon Badrick from Chipping Norton had been assigned to capture his town's mystery macropod(s), and he revealed that the wallaby may have once belonged to a Dennis Washington who kept wallabies at Middle Barton – although whether any of his had in fact escaped was not mentioned. Moreover, on 6 October London's Mail on Sunday newspaper actually published a photograph of a wallaby eluding capture by a Chipping Norton policeman. Yet whether any macropods from this hotbed of hopping activity were ever caught is unknown – like so many cryptid sagas, after a blaze of publicity Oxfordshire's mystifying marsupials simply faded from the news.

Less than two years later, a wallaby was being pursued by the Royal Ulster Constabulary after having been spotted near to Belfast Zoo in Northern Ireland, but it was not revealed whether this specimen had in fact escaped from the zoo (Sandwell Express and Star, 30 April 1987). Similarly, another wallaby of uncertain origin was also being sought by police after having been spotted hopping down the Weymouth to Wareham road in Dorset, southwestern England, by an ambulance crew (Sandwell Express and Star, 14 August 1987).

As demonstrated here by the individual standing between (but further back than) my mother Mary Shuker and myself at a farm in Melbourne, Australia, adult kangaroos can be well over 5' tall (I am 5'10" but by standing nearer to the camera than the kangaroo was, I appear much taller than it was, due to forced perspective) (© Dr Karl Shuker)

As demonstrated here by the individual standing between (but further back than) my mother Mary Shuker and myself at a farm in Melbourne, Australia, adult kangaroos can be well over 5' tall (I am 5'10" but by standing nearer to the camera than the kangaroo was, I appear much taller than it was, due to forced perspective) (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Naturalised kangaroo (as opposed to wallaby) populations are not supposed to exist anywhere in the British Isles, which makes the Cornbury Park specimen a notable puzzle. Even more bizarre, however, is the Lancashire creature observed one afternoon in 1967 by David Rees at the edge of a wooded area called Freshfields near Southport, England – an incident recalled by him in Fortean Times (summer 1980). For this animal, described by Rees as being a kangaroo, was at least 8 ft tall, with a rusty-brown pelage. Its most surprising feature, however, was its gait. Rees reported that after viewing him, the creature "...turned around and walked into the undergrowth and out of sight". Enquiries to local police failed to ascertain its origin.

Although, as stated by Dr Alyson Lander of New South Wales, Australia, in a follow-up letter (Fortean Times, Summer 1981), its colour matched that of a male red kangaroo (albeit an exceedingly tall one), no modern-day species of macropod moves by walking. Not only the origin but also the zoological identity of this animal thus remains a mystery.

ENORMOUS RABBIT-LIKE MYSTERY BEASTS DOWN UNDER

Continental Europe is not immune to phantom kangaroos either. A selection of reports concerning the French equivalent of America's 'normal' category of such beasts appeared in Fortean Times (spring 1987), courtesy of Jean-Louis Brodu. Additionally, in September 1985 one or more kangaroos were frightening villagers in northern Hungary; a Hungarian Sunday newspaper applied the escapee theory as an explanation (Fortean Times, winter 1985).

Inevitably, tales of phantom kangaroos have also been recorded from the original homeland of all marsupial hoppers – the vast island continent of Australia. However, the Antipodean brand of mystery macropod makes even the mighty 6-7-ft-tall red kangaroo, capable of 10-ft-high bounds, look positively puny in comparison. For in the arid desert land constituting the dry heart of Australia, reports from gold-prospectors and other occasional travellers to these inhospitable zones have spoken of enormous rabbit-like beasts that disappear in a single bound. Furthermore, some accounts refer specifically to "kangaroos 12 feet high".

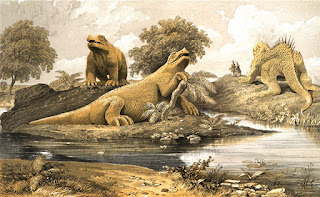

Sthenurus

depicted in walking pose (© Brian Regal/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.5 licence

)

Sthenurus

depicted in walking pose (© Brian Regal/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.5 licence

)

Consequently, in his classic cryptozoological book On the Track of Unknown Animals(1958), Dr Bernard Heuvelmans boldly suggested that these may actually be surviving representatives of Australia's giant Pleistocene macropods. Grazers such as Procoptodon and browsers such as Sthenurus attained heights of 10 ft.

However, in recent years anatomical studies based upon their fossil remains have indicated that these bipedal giants most likely moved not by bounding but instead by walking. In any event, the possibility that such massive marsupials still exist is one that may never be investigated fully, due to the daunting conditions that must be faced by anyone penetrating these environmentally hostile regions.

FINAL THOUGHTS

It is clear that the creatures hitherto classed as phantom kangaroos actually constitute a diversity of different animal types, of which only the 'normal' category is likely to feature genuine macropods. Consequently, usage of the term 'phantom kangaroo' should be restricted hereafter to this single specific group. It is also evident that public awareness concerning the phenomenon of mystery macropods has been stimulated in particular by the extensive investigations of Loren Coleman and David Fideler, and the unstinting documentation of reports by Fortean Times. It is hoped that their efforts will be ultimately rewarded by unequivocal solutions to this most curious cryptozoological conundrum.

In the meantime, however, whenever you put out scraps for the birds, don't forget to check whether the bipeds eating them include not only winged and feathered examples but also some pouched and furred ones!

Finally, be sure to click hereand herein order to read Parts 1 and 2 of this ShukerNature article – you know it makes sense!

Rolling back the years – how I looked way back in the mid-1980s when I wrote the original version of this article at the very beginning of what has become for me a lifelong and exceedingly enjoyable cryptozoological career (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Rolling back the years – how I looked way back in the mid-1980s when I wrote the original version of this article at the very beginning of what has become for me a lifelong and exceedingly enjoyable cryptozoological career (© Dr Karl Shuker)

January 27, 2022

CAUGHT ON THE HOP BY PHANTOM KANGAROOS AND OTHER OUT-OF-PLACE MYSTERY MACROPODS: Part 2 – ESCAPEES AND OTHER EXPLANATIONS

On the alert – an adult eastern grey kangaroo (© fir0002/Wikipedia –

GFDL 1.2 licence

)

On the alert – an adult eastern grey kangaroo (© fir0002/Wikipedia –

GFDL 1.2 licence

) As revealed in Part 1 of this three-part ShukerNature article (click hereto read Part 1), eyewitness descriptions of elusive kangaroo-like beasts sighted across North America vary considerably from one to another – to the extent whereby it is possible to divide such creatures, based upon their reported morphological and behavioural attributes, into several categories. Clearly, therefore, more than one type of animal is involved in the enigma of America's mystery macropods, as will now be demonstrated.

ESCAPEE THEORY

The majority of reports describe animals that resemble and behave like normal kangaroos and wallabies; such creatures are readily identified by their observers as macropods, and do not appear in any way strange in themselves(except for the ease with which they evade capture). They are made mysterious in fact only by being macropods in America – and thereby out-of-place and of undetermined origin. Hence it seems likely that such animals are indeed normal, known species of kangaroo and wallaby – but where have they come from?

In their native Australian homeland, certain macropod species, e.g. the red kangaroo Macropus rufus and certain wallabies, inhabit open plains and semi-desert areas, whereas various other wallabies and the eastern grey kangaroo M. giganteus prefer woodland regions. Such habitats are of course also found in America, and correspond closely with their Australian counterparts. Accordingly, if any American captive specimens (maintained as exhibits in zoos, circuses, and parks, or in private households as pets) have escaped in the past, the chances are that if they were fortunate enough to locate habitats comparable with those of their native Antipodean homeland, then they survived.

Red kangaroos in their semi-arid native Australian habitat, but not dissimilar from habitats on the southwestern U.S.A. (public domain)

Red kangaroos in their semi-arid native Australian habitat, but not dissimilar from habitats on the southwestern U.S.A. (public domain)

Additionally, if a pair (or indeed a number) of specimens escaped together, they may well have established a thriving naturalised population (as has happened in several different, widely dispersed localities within the U.K., for instance – see later). Having said that, the theory of escapees has been put forward so frequently to explain away sightings of mystery or out-of-place beasts in America, Britain, and elsewhere that it has virtually become a cryptozoological cliché. In some cases, moreover, it is painfully inadequate as a satisfactory solution to such sightings.

In the case of the 'normal' category of New World phantom kangaroos, however, it does present itself as a tenable solution. Certainly, many sightings of such beasts can be compared favourably with known species. The 5-6-ft reddish-brown individuals are plausibly identifiable as male red kangaroos; comparably-sized greyish-black specimens are likely to be either female red kangaroos or eastern grey kangaroos; both species are common zoo exhibits. Similarly, the 3-ft specimens resemble various wallaby species. Indeed, the creature photographed in colour at Waukesha, Wisconsin, during April 1978 (see Part 1 of this present article) specifically resembles Bennett's wallaby Notamacropus rufogriseus(as also noted by Coleman in Mysterious America), native to Tasmania but a very frequent exhibit in zoos and parks worldwide.

Bennett's wallaby squatting upright on its haunches (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Bennett's wallaby squatting upright on its haunches (© Dr Karl Shuker)

The moniker of 'phantom kangaroo' has been applied to America's mystery macropods on account of their extreme elusiveness, in turn implying a paranormal connection. However, it should be remembered that all but the very biggest macropods are relatively defenceless and all are herbivores, thereby constituting the natural prey of large carnivorous species – which in Australasia meant (until relatively recent times, geologically speaking) not only the Tasmanian wolf (thylacine) and dingo but also the marsupial lion Thylacoleo. Consequently, a well-developed capacity for evanescence and concealment is a survival necessity for macropods.

Added to this is the fact that escapee macropods will clearly be very disoriented at first, unexpectedly finding themselves in totally unfamiliar surroundings with their previous, familiar routine of existence now gone. Their response (and that of any intelligent animal faced with such a situation) will be to display enhanced defensive and protective behaviour whilst acclimatising to their new surroundings. Moreover, as they will soon discover, in North America these new surroundings contain several very hostile species, which may include pumas, bobcats, lynxes, wolverines, wolves, bears, and humans toting rifles, thereby reinforcing and perpetuating such wariness upon the part of the macropods thereafter.

Red kangaroo in almost deer-like quadrupedal pose (© ltshears/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Red kangaroo in almost deer-like quadrupedal pose (© ltshears/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Consequently, if America's 'normal' contingent of phantom kangaroos does indeed consist of escapees and their wild-born descendants, it should be no surprise to learn that they are exceedingly elusive. Any incautious individuals will be killed very quickly following their original escape, by the predators already listed.

One final point concerning the escapee theory is that escapees are notalways reported to the authorities – especially if they were pets or inhabitants of private collections and (as a result, for example, of such escapees having been brought into the country illegally, or having caused any disturbance, etc, while on the loose) their owners may themselves falling foul of the law. Indeed, unreported escapees (plus deliberately-released unwanted pets) have been responsible for establishing populations of exotic animal species in many parts of the world, and will no doubt continue to do so, albeit to the inevitable detriment of the native fauna.

MISTAKEN IDENTITY

One option that must always be considered when dealing with mystery creatures is the possibility that at least some such sightings are actually misidentifications of known native species.

Among the North American rodents is a group constituting the genus Dipodomys – the kangaroo rats. As one might expect from their name, these possess notably long hindlimbs and tail, much shorter forelimbs, and move via powerful bipedal bounds, thereby paralleling genuine macropods and occupying in America a similar ecological niche to that filled in Australia by some of the smaller desert-living macropods.

A kangaroo rat Dipodomys sp. (public domain)

A kangaroo rat Dipodomys sp. (public domain)

Kangaroo rats inhabit dry or semi-dry sandy country, and are distributed from southwestern California southwards to central Mexico. The larger species, e.g. the giant kangaroo rat D. ingens, attain a total length of almost 2 ft. They are generally nocturnal creatures, but certainly any individuals observed at dawn or dusk could be mistaken for small wallabies. Indeed, kangaroo rats may well constitute the true identity of some of the so-called "baby kangaroos" that have been reported from many U.S. regions over the years.

Another instance of mistaken identity may perhaps be responsible for the second category of American phantom kangaroos. Although true kangaroos and wallabies adopt a quadrupedal posture not only when grazing but also while moving slightly when grazing, their mode of locomotion under all other circumstances is invariably one of bipedal bounding, with their tail stretched out horizontally behind and their body held comparably. Hence true macropods would not appear to be the identity of those wallaby-sized, less-frequently spied American 'kangaroos' that hop rapidly on all fours.

A Bennett's wallaby adopting a quadrupedal stance while stationary (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A Bennett's wallaby adopting a quadrupedal stance while stationary (© Dr Karl Shuker)

One group of native New World creatures, however, whose members are of comparable size and which do behave in this manner, consists of the surface-dwelling jack rabbits (which are actually hares!) of the western United States. Even so, there are certain problems with equating the quadrupedal 'kangaroos' with jack rabbits.

Firstly, whereas the former creatures apparently resemble typical macropods in all but their mode of progression, jack rabbits have notably short tails and long ears. Also, in view of the very familiar appearance of jack rabbits, it is difficult to imagine that they could be mistaken for kangaroos by observers. The same principle applies to suggestions that such beasts were really misidentified fawns. There is also the problem of the 5.5-ft-tall quadrupedal 'kangaroo' sighted by Louis Staub in Ohio as detailed in Part 1 of this article. No known lagomorph attains such a size. Equally, Staub specifically stated that he was sure that the creature was not a deer.

A black-tailed jack rabbit Lepus californicus in quadrupedal pose but with its huge ears instantly distinguishing it from all macropods (© Jim Harper/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)

A black-tailed jack rabbit Lepus californicus in quadrupedal pose but with its huge ears instantly distinguishing it from all macropods (© Jim Harper/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)

EXOTIC EXPLANATIONS

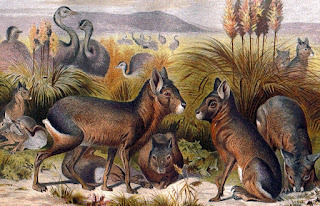

One final animal species well worth mentioning in the context of quadrupedal macropod-like beasts is the mara or Patagonian cavy Dolichotis patagonum. This most interesting creature, a guinea-pig relative, is about 2.5 ft in total length, and is very distinct from more typical cavy species, having evolved notably long hind limbs and exhibiting a cursorial mode of existence. Intriguingly, however, its overall appearance when standing is reminiscent of a small macropod on all fours.

Could this specialised rodent therefore be responsible for some of the quadrupedal 'kangaroo' reports from the States? Sadly, the mara's distribution range is limited to South America's southern half. Consequently, although this species certainly bears comparison with the description of such creatures (especially the smaller ones), it would naturally be quite ludicrous even to contemplate the possibility of native maras having any involvement in America's phantom kangaroo phenomenon – but escapees from captivity are another matter, especially as this species is often exhibited in zoos.

An exquisite 19th-Century chromolithograph depicting maras in their native Patagonian pampas together with some rheas (public domain)

An exquisite 19th-Century chromolithograph depicting maras in their native Patagonian pampas together with some rheas (public domain)

Indeed, as Loren Coleman reported in Fortean Times (spring 1982): following a spate of mystery macropod sightings in Tulsa, Oklahoma, during summer 1981, a strange bounding creature was actually captured right in the heart of Tulsa on 27 September of that year – and was found to be a mara. Its origin has never been ascertained, but it was presumably an escapee from captivity. Could an elusive naturalised population exist in that region, I wonder, descendants of original escapees? Certainly the Tulsa environment is compatible with mara survival.

It is evident that America's quadrupedal 'kangaroos' have yet to be identified with any degree of certainty. Clearly, therefore, it would be beneficial for future reports and sightings of such animals to be investigated in especial detail, and for them to be formally recognised hereafter as distinct entities from genuine phantom (i.e. 'normal') kangaroos.

White-snouted coati with upright tail and curled tail tip (© Dennis Jarvis/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

White-snouted coati with upright tail and curled tail tip (© Dennis Jarvis/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Equally enigmatic, but equally likely to have an exotic explanation, is the 4-ft-tall bipedal creature – sporting a greyhound-shaped head, short brown fur, and a long tail held vertically with a distinct curl at its tip – sighted by a Mr Workman at Tucson, Arizona, during the early 1960s, as detailed in Part 1. Although bipedal and, according to Workman, resembling in outward appearance a kangaroo, it did not move via hopping but via walking – and on notably smallhind feet. These latter features clearly dismiss a macropod identity from further consideration. So too does its vertically-held, curl-bearing tail (macropod tails are uniformly straight and are held horizontally). Clearly this creature merits its own category relative to other phantom kangaroo sightings.

However, although superficially perplexing, a most plausible solution has in fact been put forward with regard to its likely taxonomic identity. In a reply published beneath the original letter concerning this animal (ISC Newsletter, spring 1982), J. Richard Greenwell – Secretary of the International Society of Cryptozoology (ISC) – suggested that the latter could have been a coati.

A troop of white-nosed coatis with tails duly held vertically and curl-tipped (© Strobilomyces/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

A troop of white-nosed coatis with tails duly held vertically and curl-tipped (© Strobilomyces/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Coatis are lithe relatives of the raccoons, kinkajou, cacomistles, and other procyonid carnivores. They attain a total length of 4 ft, possess a slender head, and a highly inquisitive nature, in turn bestowing upon them a tendency to stand upright in order to observe more accurately any object that attracts their attention. Worthy of especial note – their tail is held vertically, and curls at its tip.

Moreover, although coatis constitute a primarily South American taxon, the distribution of the common coati Nasua narica extends as far north as the southern U.S.A., including Arizona. So far, therefore, the coati and Workman's creature accord very closely both morphologically and geographically. Even so, there arecertain difficulties. The latter beast's head-and-body length alone measured 4 ft (its tail length was additional to this), and it actually walkedbipedally. Coatis, conversely, do not attain this beast's total size; nor do they typically do more than stand bipedally – when moving, they usually bound on all fours.

Another photo of the same tails-aloft coati troop (© Strobilomyces/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Another photo of the same tails-aloft coati troop (© Strobilomyces/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

However, it is certainly possible that Workman overestimated the creature's size. Equally, some coati individuals will in fact walk at least a short distance bipedally, just like their larger relatives the bears. Indeed, in Part 1 of this article I included a link to a photo of a coati doing precisely that (hereit is again); I have also personally witnessed a pet coati walking bipedally of its own free will (like a true cryptozoologist, however, I did not have a camera with me at the time to photograph this noteworthy behaviour!). In any case, the otherwise striking correspondence between Workman's animal and a coati – even to the curl-tipped, vertically-held tail – suggests that this is indeed the correct identity for that particular mystery animal.

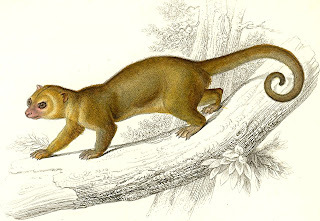

Worthy of brief mention here is another phantom kangaroo case with procyonid pertinence. Following the fraught encounter by two policemen in 1974 with an irascible, 5-ft-tall macropod lookalike nicknamed the Chicago Hopper as detailed in Part 1, a mystery creature was in fact captured nearby. Not only that, it was actually offered as the Chicago Hopper's identity. In reality, however, this was a quite ridiculous state of affairs, because the captured critter in question was a kinkajou Potos flavus – a golden-coloured relative of coatis and raccoons, but which only attains a total length of 2.5 ft, and looks nothing whatsoever like a kangaroo! The fact that the kinkajou is restricted in the wild state to Central and South America raises some interesting questions regarding the capture of a living specimen in Arizona, but as the latter's species is a popular exotic pet and zoo exhibit, it was probably just another escapee or deliberate release from captivity. Regardless of origin, however, it was clearly unrelated to the Chicago Hopper incident.

Life-like engraving from 1849 depicting a kinkajou (public domain)

Life-like engraving from 1849 depicting a kinkajou (public domain)

COUGH-LIKE SOUNDS

The Chicago Hopper is a representative of the last phantom kangaroo category delineated by me in Part 1, and whose members I dubbed there as aggressive growlers and shriekers. However, although united by their bellicose behaviour and vehement vocals, this category's members morphologically constitute a rather heterogeneous gathering. Consequently, as it is likely that more than one taxonomic identity is involved here, the principal examples will be considered individually.

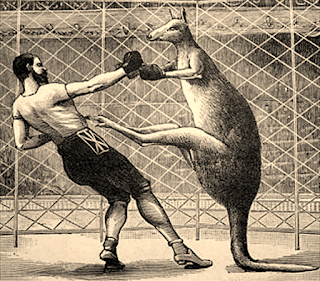

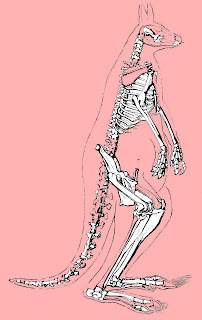

Judging from the reports on record concerning the Chicago Hopper, this was in every way a normal kangaroo – except, it appeared, for its pugnacity and unexpected utterance of growling noises. Let us now examine these latter attributes closely. It attacked by using its hindlimbs as formidable kicking instruments – which is typical kangaroo behaviour. Furthermore, although many people apparently believe that kangaroos are actually mute or at least not prone to vocalisations of any form, in the event of imminent danger all adult kangaroos (but especially males) in fact produce notable cough-like sounds. These serve to alert all other kangaroos nearby.

Vintage illustration of a boxing kangaroo using its hind feet very effectively – and emphatically! – to kick its human opponent (public domain)

Vintage illustration of a boxing kangaroo using its hind feet very effectively – and emphatically! – to kick its human opponent (public domain)

When approached by the two policemen, the Chicago Hopper clearly considered itself to be under threat, and the two responses that it displayed were those that characterise adult kangaroos when exposed to such circumstances – it voiced its cough-like alarm signal (which could certainly sound like growling, especially to two witnesses who were probably not expecting such noises from a kangaroo), and it defended itself from possible attack by using its hind legs as weapons. In short, there is no reason whatsoever to consider further that the Chicago Hopper was anything other than a normal kangaroo. Of course, its origin is still a mystery, but as it is assuredly a 'normal' phantom kangaroo the possible solutions to this riddle have already been dealt with earlier here.

Conversely, the rapacious Tennessee "kangaroo" that attacked, killed, and partly devoured waterfowl and even a number of large dogs in 1934 is a very different matter. The problem with this particular case is that no report giving any specific morphological features concerning the animal appears to have been documented – it was simply described as resembling a "giant kangaroo". However, if the reports of its carnivorous activity are accurate, then it was most certainly not a macropod. (Having said that, such creatures are not entirely unknown to science – during the Australian Miocene epoch, around 20 million years ago, Queensland was home to some sizeable meat-eating macropods, belonging to the now long-extinct genus Ekaltadeta.) Additionally, the Reverend W.J. Hancock informed the New York Times that it was seen "...running across the field". As noted earlier, macropods do not run.

Artistic restoration of possible appearance in life of Ekaltadeta ima, a prehistoric species of carnivorous Australian macropod from the Miocene (© Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 licence

)

Artistic restoration of possible appearance in life of Ekaltadeta ima, a prehistoric species of carnivorous Australian macropod from the Miocene (© Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 licence

)

Beyond this, however, it is virtually impossible to speculate regarding this cryptid's identity. If in spite of its carnivorous behaviour it resembled a kangaroo as far as its eyewitnesses were concerned, then presumably it was bipedal. Could it therefore have been a bear? Possibly, but surely it would be difficult to confuse a bear with a kangaroo. Sadly, it is likely that this intriguing mystery beast will remain mysterious, unless any report regarding it is uncovered that provides further morphological details.

Yet what of the shrieking mystery macropods? What might these be? As will be seen in Part 3, the concluding part of this ShukerNature blog article, one of the exciting possibilities concerning phantom kangaroos (especially the more bizarre forms) is that a totally unknown species may be involved. And don't forget to click here to read Part 1 if you haven't already done so.

How very unlike a macropod can a macropod look simply by changing its posture from its default bipedal stance, as demonstrated very readily by this reposing albino Bennett's wallaby (© Dr Karl Shuker)

How very unlike a macropod can a macropod look simply by changing its posture from its default bipedal stance, as demonstrated very readily by this reposing albino Bennett's wallaby (© Dr Karl Shuker)

January 21, 2022

CAUGHT ON THE HOP BY PHANTOM KANGAROOS AND OTHER OUT-OF-PLACE MYSTERY MACROPODS: Part 1 – AN AMERICAN ANOMALY

How can reports of phantom kangaroos and other out-of-place mystery macropods be explained? (public domain)

How can reports of phantom kangaroos and other out-of-place mystery macropods be explained? (public domain)

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

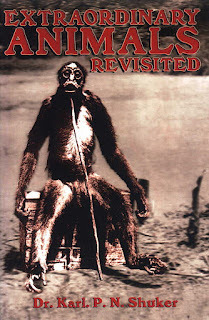

During the past 35 years, I have written many hundreds of cryptozoological articles, all of which at one time or another and in one form or another have been published – all but one, that is, until quite recently. Back in the 1980s, I penned a number of articles for a monthly British magazine entitled The Unknown, which was in fact the very first magazine to publish my writings, at the very beginning of my post-university career as a full-time freelance cryptozoological researcher and author. Sadly, however, after just over 30 issues, The Unknown abruptly folded, and in so doing meant that one lengthy three-part article of mine that this magazine had recently accepted for publication never saw the light of day in print form within it.

For reasons that I've never ascertained, I subsequently neglected to resubmit it elsewhere, and for over three decades it languished as a typed-out but largely-forgotten manuscript in a file of my earliest work. Eventually calling to mind this article in 2019, however, I sought out the file containing it, read it through again, and was pleasantly surprised by its content and composition, which I felt were more than sufficient to warrant its long-overdue publication.

Rather than attempting to update it, however, which not only would have been a herculean task but also would have expanded its already sizeable length very appreciably, I felt that for historical reasons this article may actually be of interest to readers if presented in its original, pre-existing three-part form, bearing in mind that it constitutes one of my very first pieces of investigative cryptozoological authorship. Accordingly, incorporating only minimal, essential amendments (i.e. ones required to maintain factual accuracy across the three decades since I originally penned it), 'the article that got away' was finally published in hard copy format within the CFZ Yearbook 2020 after patiently waiting for a mere 32 years to see itself in print.

The CFZ Yearbook 2020 (© Centre for Fortean Zoology/CFZ Press)

The CFZ Yearbook 2020 (© Centre for Fortean Zoology/CFZ Press)

And now, at long last, it makes its exclusive online debut here in ShukerNature (where on account of its considerable length I have split it up into its original three parts, which will be presented as three consecutive blog posts, beginning here today with Part 1).

In so doing, this resurrected research article of mine affords an insight not only into phantom kangaroos (a subject never previously or subsequently written about by me) but also into the primordial competency (or otherwise!) of the then cryptozoological 'new kid on the block' investigating and documenting them.

PART 1 – AN AMERICAN ANOMALY

In the mind of any student of natural history, Australia is irrevocably linked with marsupials – a vast morphological diversity of pouched mammals, whose most familiar members are undoubtedly those bounding bipeds the kangaroos. Together with their many smaller relatives such as the wallabies and potoroos, they are known collectively as macropods ('big feet'), and must surely be the zoological personification of Down Under.

As readily revealed by this kangaroo skeleton, kangaroos, wallabies, and potoroos are not known zoologically as macropods for nothing! The metatarsal bones in particular are very elongated, as is the fourth digit (toe) (public domain)

As readily revealed by this kangaroo skeleton, kangaroos, wallabies, and potoroos are not known zoologically as macropods for nothing! The metatarsal bones in particular are very elongated, as is the fourth digit (toe) (public domain)

Consequently, it may come as something of a surprise to learn that sightings of kangaroo-like creatures in the wild are also being recorded many thousands of miles beyond the Antipodes, in a geographical region where such animals just should notbe – North America!

UNDERLYING VARIETY

Moreover, these New World anomalies exhibit the extreme elusiveness that has earned comparably evanescent pantheresque creatures such as the Exmoor Beast and Surrey Puma of Great Britain the title of 'phantom felines'; hence the mystery hoppers are nowadays commonly referred to as 'phantom kangaroos'.

What would appear to be one of the very earliest incidents on record concerning any sighting of a supposed kangaroo in America occurred in New Richmond, Wisconsin, and was documented a year later by local historian Mrs Ann Epley (and much more recently by veteran American cryptozoologist Loren Coleman in his classic book Mysterious America, 1983). She recorded that during a severe cyclone storm in 1899 that decimated a visiting circus (Gollmar's) as well as much of New Richmond itself, eyewitness Mrs Glover reported seeing a kangaroo – presumed to have escaped from the wrecked circus – running through a neighbour's yard; it was never captured. Worthy of note here is the fact that genuine macropods do not run– they move by powerful hopping, bipedal bounds. Equally strange, moreover, the circus owner's son, Robert H. Gollmar, could not recall the circus ever having owned a kangaroo. As a result of this latter component of the incident, this beast is traditionally classed as a bona fide phantom kangaroo (despite its aberrant alleged mode of progression).

Eastern grey kangaroo Macropus giganteus, bounding bipedally in typical macropod manner (© PanBK/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.o licence

)

Eastern grey kangaroo Macropus giganteus, bounding bipedally in typical macropod manner (© PanBK/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.o licence

)

Since the 1950s, a remarkable number of sightings of mystery macropods have been documented across North America, especially from the East and Mid-West. Surprisingly, however, such creatures had been almost wholly overlooked by investigators of out-of-place animals – until Fortean writers and researchers Loren Coleman and David Fideler began an extensive investigation of this intriguing phenomenon. Indeed, their combined books, articles, and bulletins dealing with these beasts constitute the definitive (and in fact the only major) pre-internet sources of information concerning this subject (hence are naturally the sources for a number of such cases mentioned in this present article), and are responsible for establishing it as a bona fide phenomenon for serious cryptozoological study.

In their publications, Coleman and Fideler have presented this subject within a chronologically-structured framework, charting and updating its progression via series of comprehensive year-by-year reports. Consequently, in order to provide a fresh insight into the subject, my article will concentrate primarily notupon chronological documentation but instead upon the underlying (yet rarely considered) variety of creatures involved – an approach not previously utilised in relation to phantom kangaroos. For, as will be revealed, those animals currently labelled as such do not in fact constitute a uniform, homogenous set, but instead can be divided into various separate categories based upon morphological and behavioural differences.

1) 'Normal' kangaroos

In the great majority of eyewitness accounts concerning phantom kangaroos in North America that surfaced during the 88 intervening years between the Gollmar circus incident of 1899 and the year 1987 in which I originally penned this article, there is nothing to suggest that the morphology or behaviour of the creatures in question was anything other than that of normal kangaroos – except for their elusiveness. Consequently, I shall refer to those animals in this first category of American mystery macropods as 'normal' kangaroos. The following reports of such beasts include some of the most informative on record.

In 1957, the two young sons of Barbara Battmer claimed to have spied two kangaroos hopping through an expanse of forest at Coon Rapids, Minnesota, near to where they themselves were playing. They described the creatures as being 5 ft tall and in colour a combination of browns varying from light tan to medium brown. A year later, and some hundreds of miles away at Platte River, Nebraska, eyewitness Charles Wetzel, moving steadily from his plains cabin, approached to within 10 yards of a kangaroo-like beast. The latter stood approximately 6 ft tall, was brown in colour, and hopped in pronounced 10-ft bounds via its large hind legs – which contrasted sharply with its much shorter forelegs.

Red kangaroos photographed while hopping bipedally in typical macropod manner (© Donald Hobern/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Red kangaroos photographed while hopping bipedally in typical macropod manner (© Donald Hobern/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Alongside these two reports from Mysterious America, Coleman also details numerous similar sightings reported from many other American localities during the subsequent 1960s, whereas in November 1974 a 5-ft-tall Chicago specimen uniformly black except for a brown face and belly was spotted by Joe Bernotus from the window of the train in which he was travelling to work. Furthermore, in his book Weird America (1978), Jim Brandon mentions a similar-sized, macropod-mannered creature that several persons reported seeing bounding through cornfields in Du Quoin, Illinois (a notably popular State for phantom kangaroo appearances) in July 1975.

The year 1977 saw a marked return of macropod mania to the State where it had all apparently begun 78 years before – Wisconsin. As documented in Fate Magazine(September 1978) and subsequently by Stephen McMurray in a letter to The Unknown (December 1986), three separate sightings of 'normal' kangaroos took place here during 1977. Once again, all eyewitness involved were convinced that the animals were indeed kangaroos and not any known American mammalian form.

April is evidently a good month for spotting American kangaroos, because two of the most significant sightings so far recorded of 'normal' New World hoppers took place within 24 hours of each other in April 1978, during a spate of kangaroo reports emanating from or near to Waukesha, Wisconsin. On 23 April, Lance Nero sighted from his home two supposed kangaroos hopping out of the adjacent woods. Moreover, they left behind well-formed tracks (from which casts were later made). Each such track consisted of a three-pronged, furciform print (two prongs pointing forward, and one backwards – with two rounded projections sited distally along the backward-pointing prong). Despite their singular shape, however, these remarkable tracks were actually 'identified' in due course by sheriff deputies as ordinary deer spoor! Thankfully, contrary evidence was obtained the very next day during another encounter nearby, evidence that could not be dismissed so readily this time.

Diagrams of a kangaroo's foot (left) and its foot spoor (right) – the backward-pointing prong in the latter diagram is the impression sometimes yielded by the kangaroo's metatarsals, the central crescent shape is the impression produced by its foot's palm pad, and the two forward-pointing prongs are impressions produced by its foot's two largest, principal digits, IV and V (public domain)

Diagrams of a kangaroo's foot (left) and its foot spoor (right) – the backward-pointing prong in the latter diagram is the impression sometimes yielded by the kangaroo's metatarsals, the central crescent shape is the impression produced by its foot's palm pad, and the two forward-pointing prongs are impressions produced by its foot's two largest, principal digits, IV and V (public domain)

In that incident, two men (who did not wish to be named) spotted the creature in question close to two Highways near Waukesha and, to the delight of cryptozoologists everywhere, they actually had a loaded camera with them. Two colour photographs of the animal were taken, of which one proved to be too blurred for identification purposes. The other, however, while rather dark and indistinct, did reveal an indisputably bipedal creature reminiscent of a macropod. This photo (which can be viewed online here) is now owned by Loren Coleman, who, in various of his publications, describes the animal depicted as being:

...a tan animal with lighter brown front limbs, hints of a lighter brown hind limb, dark brown or black patches around the eyes, inside the two upright ears, and possibly surrounding the nose and upper mouth area.

Another significant encounter with a mystery macropod occurred in September 1979, when a dark-coloured specimen reminiscent of a kangaroo was observed in Concord, Delaware. For as recorded in Pursuit (spring 1980), police called in to investigate this sighting discovered not only unusual tracks but also a 6-inch strand of fur.

The final example of a 'normal' kangaroo offered here could have been the most important of all. Alas, however, it was not to be. On 31 August 1981, a trucker walked into a cafe at Tulsa, Oklahoma, and informed a bemused waitress that his truck had just hit and killed a kangaroo – while swerving, furthermore, to avoid hitting a second one! Two policemen at the cafe as well as the waitress herself all subsequently testified that he then revealed to them the body of a 3.5-ft kangaroo ensconced in the back of his truck. However, no photograph was taken of this specimen, which was very regrettable because the trucker afterwards got back into his vehicle and (without anyone apparently recording his name, address, or truck registration number plate) simply drove away with his cryptozoological cargo – and thus cannot be traced to learn any further details.

2) Quadrupedal kangaroos

Although equally as agile and athletic as those of the 'normal' type, the creatures constituting this second category of phantom kangaroos exhibit one fundamental difference – these are primarily quadrupedal, bounding not solely upon their hind legs but upon all fours. Despite being far fewer in number than those concerning the bipedal 'normal' forms, reports describing quadrupedal kangaroo-like beasts have similarly been recorded from varied regions of North America.

Red kangaroo in quadrupedal stance (public domain)

Red kangaroo in quadrupedal stance (public domain)

For example, longstanding American cryptozoological investigator Ron Schaffner reports in his newsletter Creature Chronicles (Spring 1983) that in January 1949, while riding a Greyhound bus between Columbus and Akron, Ohio, Louis Staub observed just such a beast about 2 miles south of Grove City, Ohio. In a Cincinnati Post report for 10 January, Staub described the creature as being about 5.5 ft tall, brown in colour with a long pointed head, and resembling a kangaroo except for the fact that it hopped on all fours. He stated that he was certain that it was not a deer.

Similarly, Loren Coleman records that on 25 November 1974, farmer Donald Johnson reported seeing a "kangaroo" that was "...running on all four feet" down the centre of a rural road through Sheridan, Indiana. Additionally, on 14 July 1975, Rosemary Hopwood observed a 2.5-ft-tall quadrupedal "kangaroo" while driving her car along Illinois Route 128 near Decatur. However, unlike the previous two examples, this particular specimen diddisplay a modicum of macropod behaviour – by periodically sitting upright on its haunches. It had pointed ears and a long thick tail.

3) Unique specimen

Category 3 consists of a single, unique specimen, which, although bipedal, differs sufficiently from the 'normal' type to warrant separate consideration. In a letter published in the International Society of Cryptozoology's Newsletter(spring 1982), Ronald Quinn recalled that the incident had occurred sometime between 1963 and 1965 at Peck Canyon (50 miles south of Tucson, Arizona) and had involved a friend, Mr Workman. He had lived in this region and had sent a letter to Quinn informing him of his encounter, which was as follows.

Click hereto see what this bipedal mystery beast may have been (more concerning the latter identity in Part 2 of this present three-part ShukerNature blog article).

Returning home from his mining work one afternoon, Workman's truck had become entrenched in some deep sand. While attempting to extricate his vehicle, he observed a most unusual creature approaching him from down the sandy wash that he had just driven over. It was a 4-ft-tall bipedal beast that reminded Workman of a kangaroo. However, its tail was held vertically and bore a distinct curl at its tip. Moreover, this bewildering biped moved by walking, rather than by hopping or bounding, and its hind feet appeared much smaller than those of a kangaroo. After watching Workman for a few minutes, the creature walked away again, and was not reported thereafter, either by Workman or by anyone else working in that area.

4) Aggressive growlers and shriekers

The final category of phantom kangaroos assembled here is more of a classification of convenience than the well-defined grouping characterising the earlier categories covered above, because Category 4's members appear to be as diverse as they are bizarre. Yet they do in fact share two notable features – a rather unnerving tendency to growl or shriek like banshees, and to act in an alarmingly aggressive manner.

One classic example, reported in detail by Fideler and Coleman within their article 'Kangaroos From Nowhere' (Fate, April 1978), is undoubtedly the pugnacious macropod known as the Chicago Hopper. During the morning of 18 October 1974, two patrolmen had been called to the Northwest home of a startled eyewitness to what had seemed to be a large kangaroo spied on his porch. Upon their arrival on the scene, however, the patrolmen came face to face with a creature that transformed their initial amusement into outright alarm. For although it did appear to the men to be a kangaroo (and standing about 5 ft tall), it was growling, in a most disconcerting manner.

Two adult male red kangaroos engaged in ritualistic fighting – notwithstanding their herbivorous lifestyle, kangaroos can be very belligerent! (public domain)

Two adult male red kangaroos engaged in ritualistic fighting – notwithstanding their herbivorous lifestyle, kangaroos can be very belligerent! (public domain)

Additionally, as they soon discovered upon drawing nearer, it was very aggressive – delivering a number of extremely powerful (and painful!) kicks before making its escape from the hapless patrolmen and the hastily-summoned back-up squad cars. As these latter arrived, the creature leaped over a nearby fence into another street, and rapidly bounded along this until it passed out of sight, and into American legend.

Yet even this belligerent biped appeared benevolent in comparison to the supposed giant "kangaroo" that terrorised Tennessee during 1934. Sighted in South Pittsburg, it displayed an especially startling and disquieting characteristic. In stark contrast to the strictly vegetarian diet of typical kangaroos, the Pittsburg beast was vehemently carnivorous. For according to the local farmers, it had slaughtered and partaken of a variety of waterfowl, plus a selection of alsatian dogs! Despite prolonged searches, however, this rapacious 'roo was never captured.

One of New Jersey's most notorious cryptids is the so-called Jersey devil. However, reports describing this beast are so diverse that, as Coleman notes in Mysterious America, it is quite evident that more than one type of creature is involved. Some of these reports describe beasts resembling kangaroos, but with quite macabre vocal attributes.

Artistic representation of the Jersey devil based upon eyewitness reports (© Richard Svensson)

Artistic representation of the Jersey devil based upon eyewitness reports (© Richard Svensson)

For example, in 1900 Mrs Amanda Sutts heard a scream one night near to the family farm's barn. When the family came outside to investigate, a kangaroo-like beast was spied, which Sutts described as being approximately the size of a small calf, weighing about 150 lb, and making the most horrific sound "...like a woman screaming in an awful lot of agony". Apparently this sound was often heard by the family, emanating from the surrounding countryside; not surprisingly, it terrified the horses. Comparable reports from elsewhere in New Jersey also exist on record (see The Jersey Devil, 1976 – a very comprehensive book on this subject, authored by James McCloy and Ray Miller Jnr), some of which describe horse-headed kangaroo-like creatures with wings!

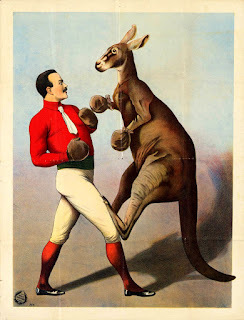

In actual fact, a famous hoax occurred in January 1909 regarding the Jersey devil, when publicist Norman Jefferies claimed that he had caught the beast, and put it on display at Philadelphia's Arch Street Museum, charging a small entrance fee for public viewing. Its true identity, however, was ultimately exposed – it was nothing more than an ordinary Australian red kangaroo Macropus rufus that Jefferies had earlier obtained from an animal dealer, and which had then been painted with green stripes and bore a pair of artificial, deftly-attached bronze wings (click here to read more about this on ShukerNature). Even so, it is interesting that the animal chosen by Jefferies to represent the Jersey devil was a kangaroo.

Having categorised America's phantom kangaroos, it is now necessary to attempt an identification of them. As will be seen in Part 2 of this three-part article, a number of possible candidates may be involved – don't miss it!

Capitalising upon potential kangaroo aggression – a boxing kangaroo advertised in a sideshow poster printed in Hamburg, Germany, by Adolph Friedländer, 1890s (public domain)

Capitalising upon potential kangaroo aggression – a boxing kangaroo advertised in a sideshow poster printed in Hamburg, Germany, by Adolph Friedländer, 1890s (public domain)

January 16, 2022

A GREEN MAN OF NOTTINGHAM, AND A PURPLE WINGED CAT? A SHUKERNATURE PICTURE OF THE DAY

The very curious but captivating painting spied and photographed in a Nottingham pub by Facebook friend Kristian Lander (© Kristian Lander)

The very curious but captivating painting spied and photographed in a Nottingham pub by Facebook friend Kristian Lander (© Kristian Lander) Today's ShukerNature Picture of the Day dates back to 15 January 2013. That was when longstanding Facebook friend Kristian Lander from Nottingham, England, posted on my Facebook wall the above photograph snapped by him of a very unusual painting that he had recently encountered inside a local public house, because he was particularly intrigued by the mauve but mysterious winged beast lurking in its bottom left-hand corner, and wondered if I knew anything about it.

Sadly, I didn't, but it certainly elicited my curiosity, and when Kristian's post containing his photo reappeared recently in my Facebook's Memories section, I decided to document on ShukerNature the sparse details that have come my way during the intervening years concerning it. So here they are, exactly eight years after Kristian first brought this perplexing painting to my attention, in the hope that someone who reads them will be able to provide further data.

Kristian informed me that the painting was hanging high above an archway inside a pub at Bulwell, Nottingham, named the William Peverel (which had opened in 2012 and is currently part of the famous JD Weatherspoon chain). Consequently, he'd had to use the zoom attachment on his camera in order to obtain his close-up photo of it, but there was no signature visible, nor was there any artist information available.

Three of my own Green Man exhibits (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Three of my own Green Man exhibits (© Dr Karl Shuker)

However, Kristian had noticed that there was a description of the painting on a nearby wall plaque. This stated that it was a picture of the man after whom the pub had been named, one William Peverel, apparently giving homage to the Green Man – a longstanding symbol of fertility and rebirth in English folkloric tradition, and usually represented as a human figure covered in green, leafy foliage. As for the purple winged creature beside Peverel, however, its identity was merely referred to in the description as "unknown".

Now for some interesting facts concerning the real-life person after whom this pub is named – William Peverel. It turns out that he was a Norman knight who was a favourite of William the Conqueror, i.e. King William I of England, who famously defeated the Saxons' King Harold II at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and thus founded the Norman dynasty in England. Peverel was specifically listed in the Domesday Book as a builder of castles, and also owned several, including Nottingham Castle. Before he died in 1114, he had sired two sons, both of whom were also named William.

The JD Wetherspoon website includes a page of details for Nottingham's William Peverel pub (there is actually more than one pub in England with this same name), which can be accessed here. Sadly, however, they contain no mention of this painting (though they do include one interior photo that shows it in place upon one of the walls), but what they do state is that this pub's namesake was actually a son of William the Conqueror. Yet according to lineages for William I that I have checked, only one of his nine children was named William, and he became King William II following his father's death, so he was certainly not William Peverel. Moreover, William I is not credited as having any illegitimate children, so I'm not sure where the Wetherspoon claim regarding Peverel being William I's son originates.

Interior photograph of the William Peverel public house in Bulwell, Nottingham, England, showing the William Peverel 'green man' painting hanging upon one of its walls directly over an archway (© JD Wetherspoon/The William Peverel – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only; please be sure to click

here

to visit this very popular pub's webpage for full details concerning its facilities, menus, location, etc).

Interior photograph of the William Peverel public house in Bulwell, Nottingham, England, showing the William Peverel 'green man' painting hanging upon one of its walls directly over an archway (© JD Wetherspoon/The William Peverel – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only; please be sure to click

here

to visit this very popular pub's webpage for full details concerning its facilities, menus, location, etc).

Peverel's parentage contradictions notwithstanding, let's turn now to the painting itself. As commented upon by another Facebook friend, Scott Wood, the face of William Perceval as depicted in it is unmistakably based upon a much earlier but very famous, and decidedly idiosyncratic, painting entitled 'Vertumnus' (Vertumnus being the Roman god of seasons, plant growth, and change), which was produced in 1591 by Italian artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526/27-1593). Here it is:

'Vertumnus', painted in 1591 by Giuseppe Arcimboldo (public domain)

'Vertumnus', painted in 1591 by Giuseppe Arcimboldo (public domain)

As can be readily seen, his subject's face is actually composed of various fruits, flowers, vegetables and other botanical offerings, which is nothing if not apt, given that Vertumnus was a plant-associated deity. Yet in spite of the name that he gave to this painting, Arcimboldo did not actually intend it to be a depiction of Vertumnus, but rather a portrait of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II.

Moreover, this phytologically-influenced illustration was not an artistic sui generis either – on the contrary, Arcimboldo was well known for this highly imaginative, albeit decidedly quirky, mode of depiction, having painted a number of other portraits in which its subjects are composed of intricate, exquisitely-arranged collections of horticultural produce as well as fishes and even books. Having said that, Arcimboldo did also prepare many far more conventional artistic works too (including the self-portrait presented at the end of this ShukerNature blog article), but his unique botanically-themed portraits are his most familiar paintings nowadays.

As for whether the clear similarity between the face of William Peverel in the pub's 'green man' painting of him and Arcimboldo's 'Vertumnus' painting indicates that the former is definitely a modern-day painting, or merely one that was painted at some undetermined time within the 400+ years that have passed since Arcimboldo painted the latter, this is of course impossible to determine without the Peverel painting being subjected to a rigorous examination by expert art historians.

Comparing the face of William Peverel in the pub's 'green man' painting of him (allowing for it having been unavoidably photographed both at a distance and at an angle) (left) with Arcimboldo's 'Vertumnus' painting (right), showing the great similarity

– please click to enlarge for improved viewing (© Kristian Lander / public domain)

Comparing the face of William Peverel in the pub's 'green man' painting of him (allowing for it having been unavoidably photographed both at a distance and at an angle) (left) with Arcimboldo's 'Vertumnus' painting (right), showing the great similarity

– please click to enlarge for improved viewing (© Kristian Lander / public domain)

Incidentally, despite the descriptive plaque alongside the William Peverel painting in Nottingham's eponymous pub stating that it depicts Peverel apparently giving homage to the Green Man, it is possible that there is an entirely different explanation for what - and even who – this painting depicts. My first clue to this unexpected yet undeniably plausible possibility came from a seemingly source-less but thought-provoking quote made known to me by another Facebook friend, Caitlin Warrior, and when I pursued it to discover its origin, this is what I uncovered.

In the compendium Medieval Outlaws: Twelve Tales In Modern English Translation, edited by Thomas H. Ohlgren and published as a revised, expanded edition in 2005 by Parlor Press, there is a Romance story entitled 'Fouke le Fitz Waryn', which is known from a single manuscript in the British Library that dates from c.1330 and is written in Anglo-Norman prose. How much of its content is based upon real events and real people and how much is folklore and heroic fantasy, however, is difficult to determine.

Translated by Thomas E. Kelly, and beginning not too long after William the Conqueror has become England's monarch, it tells of how William Peverel proclaims a tournament at which the knight who performs best and wins the tournament shall receive as his prize the hand of William's beautiful niece, Melette of the White Tower. Waryn de Metz (Metz being in Lorraine, France), a valiant but unmarried, childless nobleman, decides to take part, attended by a company of knights sent by his cousin John, Duke of Brittany, to assist him. When they arrive in England, Waryn and his company pitch their tents in the forest near to where the tournament is to be held.