Karl Shuker's Blog

September 28, 2025

BRINGING TO LIFE THE (IN)FAMOUS PHOTOGRAPH OF LOYS'S APE: A SHUKERNATURE VIDEO(S) OF THE DAY

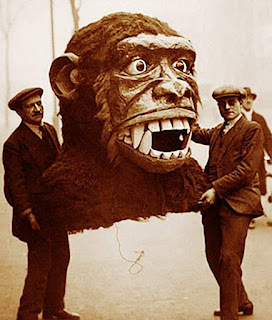

A coupleof photo-stills from my two AI-generated video clips of the familiar cropped versionof the notorious Ameranthropoides loysiphotograph (the centre image here) coming to life (AI photo-stills and videos createdby me using Adobe Firefly)

A coupleof photo-stills from my two AI-generated video clips of the familiar cropped versionof the notorious Ameranthropoides loysiphotograph (the centre image here) coming to life (AI photo-stills and videos createdby me using Adobe Firefly)

It's been several months since I postedhere on ShukerNature a ShukerNature Picture of the Day (click here to access the most recent one),and I have never posted a ShukerNature Video of the Day – until now, that is.Moreover, because I'm a generous kind of guy, I've posted two, not just one, asyou can see. But what is their theme, their subject matter? Here's my answer:

Have you ever wondered what would havehappened if Loys's ape Ameranthropoidesloysi had been genuine, not a hoax, and its fake photograph had come tolife? Wonder no longer!

These two video clips were generated for meyesterday by the AI image-generation program Adobe Firefly in response to twoseparate prompts provided to it by me – one was a detailed verbal descriptionwritten by me, the other was a visual prompt consisting of the original Ameranthropoides loysi photograph,reproduced below:

Allegedlydating from 1917, this is the less familiar uncropped version of the notorious Loys'sape photograph, revealed several decades later to have been a hoax, featuringthe dead body of a pet spider monkey (public domain)

Allegedlydating from 1917, this is the less familiar uncropped version of the notorious Loys'sape photograph, revealed several decades later to have been a hoax, featuringthe dead body of a pet spider monkey (public domain)

One ever-present, ever-surprising factorthat I've encountered numerous times when utilizing various different AIimage-generation programs to create the pictures and most of the videosappearing in my pictorial biker/motorcycling-themed blog RebelBikerDude's AI Biker Art, is thesheer unpredictability and often truly surreal nature of their output, in whichall manner of unexpected, wholly unprompted visual details are frequently includedby the programs in their generated images (bikers anomalously sprouting wingscomes readily to mind with my AI biker art blog!). Sure enough, the secondvideo in this present ShukerNature article will be seen to include – albeit onlyvery briefly – some strange large object appearing and disappearing behind thecreature's back. What it is is anyone's guess!

To read my comprehensive three-part coverageon ShukerNature of the entire A. loysiphoto saga, be sure to click here, here, and here. It also appears as an entire, fully-updatedchapter in my book ShukerNatureBook 2: Living Gorgons, Bottled Homunculi, And Other Monstous Blog Beasts.

There is also a shorter version in one of my earlier books, Extraordinary Animals Revisited: From Singing Dogs To Serpent Kings, which features a sepia-tinted version of the Loys's ape cropped photo on its front cover:

July 12, 2025

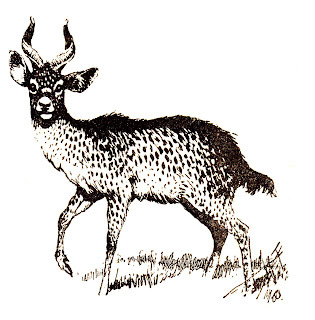

SPOTTING A SPOTTED BUSHBUCK IN LIBERIA

Atypically-patterned male northern bushbuck in Senegal (© Lucy Keith-Diagne/Wikipedia–

CC BY 4.0 licence

)

Atypically-patterned male northern bushbuck in Senegal (© Lucy Keith-Diagne/Wikipedia–

CC BY 4.0 licence

)Bushbucks are the smallest members of thespiral-horned African antelope group, which also include the kudus, nyalas,sitatunga, elands, and bongo. Traditionally, just a single bushbuck species hasbeen recognized, Tragelaphus scriptus,albeit with numerous subspecies (some of which long ago were briefly deemed bycertain 'splitter' mammalogists to be species in their own right before being 'lumped'into T. scriptus), distributedthrough much of sub-Saharan Africa. More recently however, it has been splittaxonomically into two – the northern bushbuck, native to western andnorthern/central Africa, which retains the binomial name T. scriptus; and the Cape bushbuck T. sylvaticus, native to southern and eastern Africa.

Moreover, in the Cape bushbuck both sexesare generally brown, often with only limited coat patterning on the torso, evenin the more showy male (though more strikingly patterned individuals dosometimes occur). Conversely, the northern bushbuck is the more familiar form,patterned as its torso is (most especially in the adult male) with a diverse,eyecatching arrangement of vertical white stripes on its flanks and often also ahorizontal lower flank stripe lying beneath them plus a couple of horizontalshoulder stripes, all of them again white, as well as a series of white spotson its haunches. The overall effect is as if this antelope is wearing aharness, which is why a popular longstanding alternative name for the bushbuck asa whole has always been the harnessed antelope, but which is nowadays appliedspecifically to the northern species.

Adultfemale northern bushbucvk with calf in Ghana (© Lalambala/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Adultfemale northern bushbucvk with calf in Ghana (© Lalambala/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

However, as will now be revealed, thereis one northern bushbuck specimen on record whose coat patterning isdramatically different from that of any other bushbuck of any kind – so muchso, in fact, that veteran cryptozoologist Dr Bernard Heuvelmans deemed itworthy of being investigated as potentially representing an entirely discretebut currently undescribed species in its own right. In addition, itsextraordinary skin is apparently still preserved in a museum. Yet this unique,fascinating individual and its very intriguing history have never been fullydocumented in any English-language publication – until now, that is, via thisworldwide ShukerNature exclusive. So, let's begin at the beginning of this verybelated bushbuck revelation.

I first learned of this singular specimenduring the mid-1980s, when browsing through Heuvelmans's lengthy but thoroughlyengrossing paper 'Annotated Checklist of Apparently Unknown Animals With WhichCryptozoology is Concerned', a paper that I have since returned to countlesstimes during my own researches. It was published in Vol. 5 of Cryptozoology, the official scientificjournal of the now-defunct International Society of Cryptozoology, and in it Heuvelmansbriefly documented dozens of cryptids, many of which were very obscure andhitherto-unknown to me, arranged geographically and via habitat, with eachcryptid's entry supplemented by one or more source references. Here isHeuvelmans's entry for the mystery bushbuck:

A small, entirely spottedbushbuck antelope, known only from an incomplete skin (preserved in theZoological Museum of Berlin University) from Liberia (Pathé 1940).

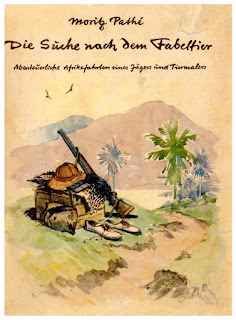

The reference cited by him is: Pathé,Moritz (1940). Die Suche nach demFabeltier [The Search For TheMythical Creature]. DeutscherVerlag (Berlin).

Thefront of the dustjacket for Pathé's above-cited book, illustrated with one ofhis own paintings – note the spotted bushbuck skin sticking partly out of oneof his cases (public domain)

Thefront of the dustjacket for Pathé's above-cited book, illustrated with one ofhis own paintings – note the spotted bushbuck skin sticking partly out of oneof his cases (public domain)

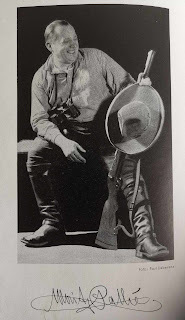

Moritz Pathé (1893-1956) was a prolificand very talented German artist, photographer, and book illustrator,specializing in animal illustrations, and the author of several works,documenting his travels in Africa seeking rare creatures to portray, but alsoto hunt and trap.

Yet despite searching for moreinformation concerning Pathé's enigmatic antelope, I was unable to locate any,and eventually it slipped from my mind. A few weeks ago, however, my interestin it was revived when palaeontologist and fellow cryptozoological writer DrDarren Naish contacted me to enquire whether I had any information on fileregarding it. As I still hadn't, Darren's query inspired me to launch anothersearch, and this time, finally, I achieved success, thanks to two longstandingfriends who both share my enthusiasm for all matters of a cryptozoologicalkind.

The first of these was Frenchcrypto-scholar Michel Raynal, who kindly supplied me with a copy of the principalchapter from Pathé's book in which he documented the Liberian spotted bushback(the entire book featured it, as it was the mythical animal referred to in thetitle, but this particular chapter contained the most significant informationconcerning it). Although the text was in German, I would normally have experiencedno problems with translating it, but as various of you may know, for quite sometime now I have been afflicted with a close-up vision problem (happily, mydistance vision is unaffected) that makes reading and on-screen researchdifficult at present (an operation to correct this condition should be takingplace soon). Consequently, translating many pages of German into English is presentlybeyond my capabilities.

Moreover, because the font employed inthe book is a very ornate one that was commonly used in German publicationsback in the days when Pathé's book was published, blocking and pasting the textin sections into Google Translate and other translation sites also failed,because its ornate font rendered the text unreadable by the online translators.

But then one of my German crypto-friends,Markus Hemmler, came to my rescue, generously providing me with an immenselyuseful English translation of the relevant chapter (annotated by him with somevery informative explanatory notes), plus other excerpts, as well as a copy ofa colour plate from it (as did Michel) that contained Pathé's own very detailedillustrations of the skin, showing it dorsally and laterally, and which I'veincluded here, as you'll see below. Markus subsequently also supplied me withan image of the full-colour illustrated dustjacket of Pathé's book (shown abovehere), the illustration being one of the author's own paintings, plus some ofhis line-drawings that appeared inside the book. All of these will be revealedlater here.

First of all, however, here is a summaryof the pertinent information regarding the spotted bushbuck as provided byPathé in the principal chapter of his book devoted to it plus some referencesto it that appeared in subsequent chapters:

In 1937, Pathé was spending time in the WestAfrican country of Liberia, with the express purpose of hunting, drawing, andpainting various of its more exotic animal species, in particular the pygmyhippopotamus and the crowned eagle. But a fortuitous meeting with a youthoffering for sale a truly extraordinary albeit incomplete antelope skin changedthe course of his plans completely, so that much of his time there was insteadspent seeking a living example of this exceptionally elusive, ostensiblymythical, yet (by virtue of the afore-mentioned physical, tangible skin)unequivocally real creature, even inspiring the title of the book that he wouldwrite about his adventures.

To quote from one of Markus's annotationsto his English translation of the relevant sections from Pathé's book:

At the beginning of the bookPathé already is in Monrovia [Liberia's capital] and until page 92 he describessome adventures like the journey from Monrovia (via Mesurado River, StocktonCreek to St. Paul River, then over land to Royersville at the Po River andbeyond this river into the jungle) to Bangatown at the Lofa River [innorthwestern Liberia] and his experiences and exploration of the surroundingarea.

And so it was that one day during hisstay in Bangatown, Pathé received an unexpected visitor in the form of a nativeyouth named Jimmy, about 20 years old and hailing from a small village farupriver in the neighbouring but still quite distant Gola region. Jimmy had beenhoping to sell the skin on behalf of his uncle to some people with whom hisfather and uncle had done business before, but for various reasons he failed tosell it to them. However, being mindful of Pathé's reputation as a hunter,Jimmy had then brought the skin to him, in case he may wish to buy it, and asPathé had never seen anything like it before, he swiftly did so.

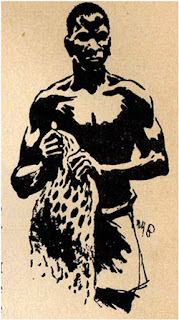

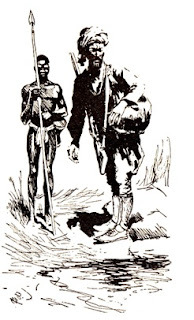

Ab/w illustration by Pathé from his book, depicting Jimmy holding the spottedbushbuck skin (public domain)

Ab/w illustration by Pathé from his book, depicting Jimmy holding the spottedbushbuck skin (public domain)

According to Jimmy, who also had neverseen one like it before, the antelope had been shot by a native huntersomewhere in Gola. Jimmy stated that he did not know specifically where, buteventually revealed that the hunter had mentioned a distant spot on the MahéRiver, a tributary of the afore-mentioned Lofa River..

Pathé decided to hire Jimmy as hishunting boy, offering him both pay and on-the-job training if he accepted, whichthe youth instantly did, promising to return in a week's time and begin hisexciting new career, which again he did.

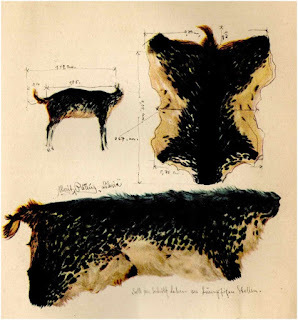

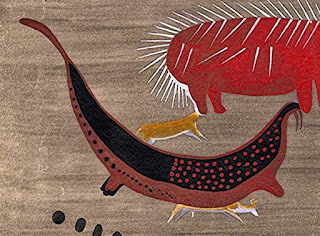

The book then digresses, pursuing othertopics such as the successful search by Pathé and Jimmy for a crowned eaglethat Pathé hoped to paint, but on p. 110 he returns to the anomalous antelopeskin, which becomes his principal focus thereafter. Yet what was so specialabout it? Here is the earlier-mentioned colour plate containing threeillustrations of it by Pathé:

Threecolour paintings of the mystery spotted antelope skin, the first one being aconcept image of what it may have looked like with its legs still present; allthree prepared by Pathé (public domain)

Threecolour paintings of the mystery spotted antelope skin, the first one being aconcept image of what it may have looked like with its legs still present; allthree prepared by Pathé (public domain)

As seen, the skin lacked its head and limbs,but those were not relevant in relation to what instantly set it apart from allknown antelopes, which was its remarkable patterning. Although its species appearedat the very least to be akin to the bushbuck, this skin lacked the latter'scharacteristic white stripes and posterior white dappling. Instead, andincongruously, its back and much of its flanks were heavily patterned with blackspots, which in its dorsal and upper dorso-lateral regions had coalesced andcongealed so extensively that a solid mass of black pigmentation had resulted.

Could this extraordinary creaturerepresent a hitherto-undescribed species in its own right, or was it a verydistinctive, aberrant specimen of the known northern bushbuck? Pathé personallyappeared far from sure, because during the course of his book his opinionoscillated back and forth constantly between these two options.

When I first saw his paintings of it, Iimmediately thought of two remarkable leopards that had been shot in thevicinity of Grahamstown, South Africa, during the 1880s (click here to see my documentation andpictures of them on ShukerNature; they are also chronicled in my three books onmystery cats). Dubbed melanotic at that time (but a term rarely used today), ineach of these aberrant individuals the typical black-pigmented leopard rosetteshad broken up on the flanks into tiny but very profuse black spots that in theupper dorso-lateral and dorsal regions had amalgamated into solid or near-solidexpanses of black pigmentation, just as was exhibited by Pathé's singularbushbuck specimen.

In the case of the Grahamstown leopards(similar cases are also on record featuring other leopards, tigers, and atleast one jaguar individual known to me), this abnormal patterning is nowadaysreferred to as pseudo-melanism, distinguishing it from true melanism.

For in the latter condition (which isresponsible for all-black leopard specimens aka black panthers, and all-blackindividuals in many other animal species too), the pelage's black rosettes ofthe individual in question are unaffected but its background colour isabnormally dark, so much so in fact that it often obscures the presence of therosettes. Conversely, as described above, in pseudo-melanism the backgroundcolour of the individual's pelage remains its usual shade but is virtuallyobscured dorsally and dorso-laterally by abnormal amalgamation and coalescingof the black rosettes into large expanses of solid black pigmentation plusintense black speckling elsewhere on the flanks.

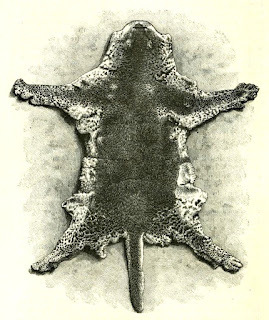

Illustration from the 1880s depicting the dorsalview of the second melanotic Grahamstown leopard's skin, clearly revealing itsremarkable pseudo-melanistic patterning, which is ostensibly reminiscent of thespotted bushbuck's patterning (public domain)

Illustration from the 1880s depicting the dorsalview of the second melanotic Grahamstown leopard's skin, clearly revealing itsremarkable pseudo-melanistic patterning, which is ostensibly reminiscent of thespotted bushbuck's patterning (public domain) However, the fundamental problem withseeking to identify the spotted bushbuck skin as that of a pseudo-melanisticspecimen is that in typical bushbuck specimens their markings are white, notblack. So as bushbucks never normally possess any black markings at all, Icannot conceive how pseudo-melanism could create this specimen's unique patternof black-pigmented spots and coalesced black spotting.

In contrast, it is possible that the skinrepresents an example of incomplete true melanism, whereby instead of the pelageof the individual in question being black all over, it exhibits melanism onlyin certain body regions, such as its back and flanks, for instance. In some casesinvolving very discrete, localized body regions, this is known as mozaicism,with one famous example being that of Ranger, a male lion born during the 1970sat Glasgow Zoo (then called Calder Park Zoo). His parents were of normalcolouration, but he exhibited a large black region on his chest plus anotherone on his right foreleg (click here to see my documentation of Rangeron ShukerNature).

Whatever the precise explanation for thisbushbuck skin's aberrant appearance, however, it is hardly surprising that Pathéwas so interested it – but he was not the only one.

Asketch by Pathé of the spotted bushbuck's incomplete skin in dorsal view thatappears on the cloth binding of his book's front cover (normally hidden beneaththe dustjacket) (public domain)

Asketch by Pathé of the spotted bushbuck's incomplete skin in dorsal view thatappears on the cloth binding of his book's front cover (normally hidden beneaththe dustjacket) (public domain)

Not long after purchasing the skin fromJimmy, Pathé received a visit from a renowned big game hunter/explorer ofEnglish-African-Indian heritage named Charles Sandiputt. He made a living fromshooting rare specimens for rich Western clients and then charging them steeplyfor the privilege of acquiring these greatly-desired trophies, but he was currentlyrunning low both on funds and on gun cartridges, and hoped to purchase some ofthe latter from Pathé. While conversing, Pathé naively showed Sandiputt thespotted bushbuck skin, and although the hunter tried to disguise hisexcitement, it was clear to Pathé how very interested he was in it.

Sure enough, after examining the skin indetail, Sandiputt offered Pathé a sizeable sum of money for it (despite havingpleaded poverty earlier), and also offered to go hunting with him in search ofadditional specimens. This last-mentioned offer in particular was an abruptabout-face to say the least, after just moments earlier having turned downPathé's own suggestion for them to go hunting together, but that of course was beforehe'd seen the spotted bushbuck skin!

However, Pathé refused both of thehunter's offers, having realized by now that he'd made a mistake in revealingthe skin's existence to Sandiputt, who departed not long afterwards withouthaving secured from Pathé not only the skin but also any specific detailsregarding who had shot the animal itself and where. Some days later, however,Sandiputt surreptitiously reappeared, and was caught by Pathé questioning hisnative helpers on this very same subject, but having already been prompted byPathé not to divulge any details about it to anyone, they remained tight-lipped.

To cut a lengthy story short: AfterSandiputt had exited empty-handed a second time, Pathé soon sent Jimmy back tohis Gola homeland to find the hunter from there who had shot the freak bushbuck,and secure his services in a search for living specimens, which Jimmy did.Pathé dubbed the hunter Bill, who then led Pathé and his hunting party to the mountainousregions upstream of the Little Mahé River in Gola. Here, with Jimmy serving astranslator, Bill claimed to have not merely shot the specimen whose skin wasnow a closely-guarded possession of Pathé (he even took it with him on their Golahunt, in order to ensure that it was not stolen in their absence if leftunguarded back at Bangatown) but also to have seen several additional livingspecimens.

However, the hunt for these elusiveantelopes proved unsuccessful, due in no small way to Pathé's alarmingdiscovery that Sandiputt was also seeking these creatures in this very samevicinity and at the very same time as them, and that – in an example of deviousintrigue worthy of high politics or industrial espionage – Bill was a veritabledouble agent. For he had already been contacted and cunningly hired in secret bySandiputt to tire out Pathé's party so that they would quit the search andreturn to Bangatown, leaving behind Bill who would then lead Sandiputt in hisown search, assisted by the local villages' inhabitants to whom Sandiputt hadpromised a big reward for a skin or information concerning where such antelopescould be found alive. Furthermore, Bill was to steal Pathé's boat too fortravelling up the Mahé River, as Sandiputt didn't have access to one himself!

Billwith Charles Sandiputt, drawn by Pathé (public domain)

Billwith Charles Sandiputt, drawn by Pathé (public domain)

Ultimately, however, Sandiputt's dastardlyploy was all in vain, with none of his unscrupulous plans coming to fruition, becausethe ever-loyal Jimmy had made sure that Bill did not steal Pathé's boat, and neitherparty encountered any spotted bushbucks anyway (though Pathé did make a somewhatparadoxical claim that he and Bill briefly spied two such creatures together,only to directly contradict himself a little later in his book by saying thathe had failed to find any – very strange). Ultimately, however, everyone returnedhome in apparent defeat, certainly with their respective quests for actualskins unfulfilled. But even then, the story was not quite over.

For not long after Pathé had arrived backin Bangatown with his party, his hut suffered an unexplained break-in, with nofewer than four of his locked iron cases and trunks having been forced open, yetnothing inside them had been taken. Bearing in mind that Pathé had been keepingthe precious bushbuck skin locked in just such a case (he had several of themin his hut), he naturally suspected that whoever had broken in was seeking theskin but had chosen the wrong cases. Presumably, moreover, as Pathé's remainingcases (including the one that did contain the skin) had not been tampered with,the would-be burglar(s) must have come close to being disturbed, causing themto flee before having chance to force open any of the others.

Despite a thorough investigation takingplace, no culprit was ever identified or apprehended, but Pathé reflected extensivelyupon the indisputable fact that when Sandiputt had first visited him, thehunter had witnessed him taking the skin out of one of these cases, so Sandiputthad been aware thereafter that this is where it was being kept. Moreover, Sandiputthad reappeared at Bangatown just a short time before the burglary had takenplace (his excuse for doing so being that he wished to return Pathé's loanedcartridges to him), so he was known to have been in this precise location atthat precise time. Coincidence?

After describing a feverish dream inwhich he had shot a spotted bushbuck, only to wake up and find that it had allbeen nothing more than a hallucination, and that it was now Christmas Day, Pathémade plans to travel back to Liberia's capital Monrovia and thence to Germany, dulyarriving home in early 1938. Pathé had always planned to make his zoologically-valuable,unique spotted bushbuck skin freely available to science, so although it tookhim several months after returning to Germany before he actually did so, Pathéfinally fulfilled his vow by donating it to the Zoological Museum at the HumboldtUniversity of Berlin. In response, he received the following writtencommunication from the then head of its mammal department, the eminent Germanzoologist Prof. Hermann Pohle (and which is translated here by Markus):

Dear Mr Pathé!

Thank you very much for sending me the fur from Monrovia.At first glance, I could see that no wild animal from which it could have comeis known. A careful comparison then revealed that no domestic animal of thiscoloration is known either. Therefore, it is an unknown species or breed.Unfortunately, the fur is very incomplete; it is missing the head and legs.Therefore, it is unsuitable for a new description. It would therefore be ofgreat value if you were able to travel to Liberia again and capture a completeanimal, at least the fur and skull of one specimen.

Needless to say, however, Pathé did notdo so, as WW2 would soon be changing the face of the world forever, but that isnot all.

As is so depressingly frequent in sagasof physical, tangible cryptozoological specimens, Markus made a worryingdiscovery when he recently contacted the museum for information concerning theskin. Can you guess what he discovered? Yes indeed, there was no entry eitherfor the skin itself or for the name Pathé on the museum collection's database! However,as he did learn, the collection isn't fully digitized as yet, so the skin maystill turn up there, lurking meanwhile in anonymity somewhere within the museum'scapacious basement, perhaps? Also, the database isn't accessible online atpresent anyway, after having gone offline in 2024 due to a cyber-attack, buthopefully at some stage in the future it will reappear online, enabling externalresearchers like Markus and myself to peruse it directly ourselves.

A sketchby Pathé from his book, depicting how he conceived the spotted bushbuck mighthave looked in life (public domain)

A sketchby Pathé from his book, depicting how he conceived the spotted bushbuck mighthave looked in life (public domain)

Alsoof note is that Markus succeeded in obtaining from the archives of Berlin'sNatural History Museum seven pages of written correspondence between Pathé andPohle, but there was only a single very brief reference in them to the spottedbushbuck. Namely, in a letter to Pathé dated 25 October 1946, Pohle expressed optimism that Pathé would soon resume travelback to Liberia (now that WW2 was over), and stated: "It seems to me thatyou must now finally find the mythical creature and bring it back, even if itis only a domestic animal", but as already noted here, that never happened,and given the unverified nature of its continuing presence in the HumboldtUniversity Zoological Museum's collection, Pathé's spotted bushbuck skin is aneven bigger enigma now than it was before!

And on that unsatisfactory,unresolved note, we must bid adieu at least for the time being to the anomalousantelope constituting the subject of this present ShukerNature article – themost comprehensive coverage of it ever published in the English language. Markusplans to prepare a German-language counterpart, which will be posted in duecourse in his own blog, and when it appears there I shall add a clickable linkto it here.

Lastly, one of the mostunexpected aspects of this entire saga is that Pathé does not appear to haveactually stated anywhere in his book the precise year when his search for thespotted bushbuck took place, but due to some masterfully Sherlockian detectivework by Markus, it seems safe to say that it was in 1937. This is becauseMarkus uncovered a short newspaper report published on 28 April 1938 by the Bergische Post, in which it mentionsthat Pathé "has just returned from Liberia". Recalling that Pathé hadspecifically referred in his book to spending Christmas there, just before leavingLiberia to return home to Germany, this clearly identifies the year that hespent in Liberia as 1937.

If any additional news regardingthe spotted bushbuck skin emerges, I'll include it here as an update.Meanwhile, my sincerest thanks go to Markus Hemmler and Michel Raynal for verykindly making so much relevant information available to me, thereby making mypreparation of this article possible.

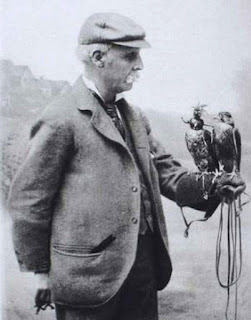

A vintage photograph of Moritz Pathé, from his book Mit Büchse und Palette im westafrikanischenUrwald (Franz Schneider Verlag: Berlin, 1944) (public domain)

A vintage photograph of Moritz Pathé, from his book Mit Büchse und Palette im westafrikanischenUrwald (Franz Schneider Verlag: Berlin, 1944) (public domain)

June 5, 2025

MANIFESTING THE MULILO - A RAINBOW-SUMMONED HILL-DRAGON, OR A LOATHSOME BLACK SLUG-SNAKE?

Mightthe mulilo – if it exists – look something like this? (created by Dr Karl Shukerusing Dream Lab)

Mightthe mulilo – if it exists – look something like this? (created by Dr Karl Shukerusing Dream Lab)

In more than 40 years of cryptozoologicalresearches and writings, I have been proud and privileged to introduce to thecryptozoological community and beyond a considerable number and notable diversityof cryptids whose details had been hitherto consigned to obscure, overlooked periodicals,books, and other passed-over publications. One such mystery beast is themulilo, whose details I uncovered in a long-since-forgotten Empire Review article, but which I dulydocumented and discussed in one of my own books, From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings, first published in 1997,and which was the very first crypto-themed publication to include it.

My book From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings (© Dr KarlShuker)

My book From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings (© Dr KarlShuker)Today, conversely, numerous onlinewebsites have also documented this creature, but as far as I can tell theircoverages are merely paraphrasings of mybook's original version, with no new, additional content Yet my book is seldom referenced as theirsource, sadly.

Consequently, coupled with theregrettable fact that certain of these online paraphrased coverages are farfrom accurate iterations of mine anyway, I've decided to present onShukerNature my book's original, concise account of the mysterious mulilo – so hereit is.

Dream a dream of a mysterious dragon that only appears when arainbow is resting upon the vivid, viridescent hillsides of Zaire [now theDemocratic Republic of Congo] and Zambia – a creature whose reality is widelyaccepted by many native people in these tropical African countries. One mightexpect such an Arcadian, picturesque scenario to inspire images of a bright,evanescent entity with sparkling opalescent scales, a proud noble head ofclassical profile, and sweeping, polychromatic butterfly wings – a golden,glittering creature of Faerie, of heady sunlit reverie.

Yet nothing could be further from the truth, because the imagethat these people do visualize when contemplating this creature is an evocationof much darker dreams. According to their belief, Central Africa'srainbow-summoned dragon, known as the mulilo, is a gigantic, coal-black,slug-like beast of loathsome form, almost 6 ft in length, over 1 ft in width,and leaving death in its wake – the deadly legacy of its poisonous breath.

Could the mulilo be a giant black slug? (createdby

Dr Karl Shuker

using Grok X1)

Could the mulilo be a giant black slug? (createdby

Dr Karl Shuker

using Grok X1)

One could certainly be forgiven for considering the mulilo to benothing more than a fanciful folktale. Yet as reported in 1940 by W.L. Speightwithin an Empire Review article onAfrican mystery beasts, a living, corporeal animal is apparently involved,because pieces of blackened flesh said to be from dead mulilos are worn by somenatives as fertility charms.

There is no known species of slug that attains the size attributedto the mulilo; in any event, the bodies of slugs are relatively insubstantial,little more than slender gelatinous sacs - hardly the likeliest of materials toremain intact for utilization as charms. Perhaps, therefore, the blackenedflesh is really from a slug-like snake, or even a serpentine salamander (likethe sirens of North America).

Even so, the thorny question remains as to whether this corporealcreature is truly the mulilo, or whether its flesh is merely used by thenatives to vindicate their belief in what is actually a non-existent, whollymythical beast? If the flesh is froma mulilo (regardless of what species it may belong to), how do the nativesobtain it?

Another giant black slug-inspired mulilorepresentation (created by

Dr Karl Shuker

using Grok X1)

Another giant black slug-inspired mulilorepresentation (created by

Dr Karl Shuker

using Grok X1)

According to Speight, they set a trap – building a secure cage,lined internally with sharp blades, and baited with a living cockerel. Thenthey simply wait each night, and listen. On the morning that no cock-crow isheard, the natives celebrate and journey joyfully to the cage – for they knowthat inside it they will find the mulilo, dead, impaled upon the blades duringits capture of the cockerel.

Yet despite this apparently successful method of obtainingmulilo remains, the mulilo is as mysterious and unidentified today as it waswhen documented by Speight over half a century ago [almost a full century agonow]. Moreover, it does not even seem to have been reported again. Perhapsrainbows have been rare in Zaire and Zambia lately?

Myview concerning the mulilo that I held back in the late 1990s remains unchangedtoday, almost 30 years later. Namely, that if it is indeed a real,flesh-and-blood entity, it is most likely to be some form of black-scaled snake,possibly a fairly thick-bodied or sturdy one, perhaps even a melanistic varietyof a species already known to science.

Overthe years I have documented a number of times with a variety of different examplesthat in the culture of many indigenous peoples from around the world, aberrantanimal specimens, such as melanistic, albinistic, or extra-large individuals,for instance, are often categorised by them as being fundamentally (rather thanmerely superficially) distinct, wholly separate creatures from normal specimensof the same species, and are even given wholly separate names by them.

Is the mulilo based upon an unusual melanisticvariety of snake? (created by

Dr Karl Shuker

using Dream Lab)

Is the mulilo based upon an unusual melanisticvariety of snake? (created by

Dr Karl Shuker

using Dream Lab)

So ifthe mulilo were indeed nothing more than an all-black form of a known snakespecies but deemed special by the locals on account of its unexpectedcolouration, this would not be in any way surprising.

In addition,certain snakes, especially large meat-eating constricting species such as theAfrican pythons, are notorious for the foul stench of their breath. So if themulilo is simply a melanistic version of one such species, this could plausiblyexplain native testimony (conceivably somewhat exaggerated or embellished ifretold to the more ingenuous of Westerners?) relating to its allegedlypoisonous exhalations.

A large and sturdy melanistic specimen of constrictingsnake might inspire superstitious fear among local people encountering it (created by Dr KarlShuker using Magic Studio)

A large and sturdy melanistic specimen of constrictingsnake might inspire superstitious fear among local people encountering it (created by Dr KarlShuker using Magic Studio)

If onlyfurther details could be obtained. So if anyone reading this ShukerNaturearticle is aware of any addition information appertaining to the mulili, I'dlove to hear from you, so please comment below with your news – many thanksindeed!

Excerptedfrom my book FromFlying Toads To Snakes With Wings (Llewellyn: St Paul, 1997).

An intriguing image generated by Dream Lab,combining the serpentine scaly body of a melanistic snake with slug-likecephalic tentacles – the perfect mulilo? (created by Dr Karl Shuker using DreamLab)

An intriguing image generated by Dream Lab,combining the serpentine scaly body of a melanistic snake with slug-likecephalic tentacles – the perfect mulilo? (created by Dr Karl Shuker using DreamLab)

April 18, 2025

SHUKERNATURE IS #1 – CONFIRMING WHAT MY COUNTLESS LOYAL SHUKERNATURE FANS AND FOLLOWERS HAVE ALWAYS KNOWN!

FeedSpot'sofficial opening image to its listing of the 15 Best UK Nature Blogsin 2025 (© FeedSpot)

FeedSpot'sofficial opening image to its listing of the 15 Best UK Nature Blogsin 2025 (© FeedSpot)Ever since I launched it way back inJanuary 2009, my ShukerNatureblog has consistently received praise, plaudits, and even some awards, based uponits content, which has always been judged to be entertaining, interesting, eminently reliable, and extremelyeducational – and for which I am exceedingly grateful to everyone concerned,most especially its countless loyal fans and followers.

Now I am delighted to announce that myblog has garnered a further award. On 12 April 2025, as I was kindly informed thisweek by its founder and creators account manager Anuj Agarwal, the blog databasewebsite FeedSpot has awarded ShukerNature itspremier, #1 position in the blogs section of its new listing of the 15 Best UKNature Blogs and Websites in 2025!! Please click hereto view the entire listing.

Nor is that all. ShukerNature also appears at #18 in FeedSpot's Best 90 Nature Blogs worldwide! Click here to view the entire listing.

My sincere thanks to Anuj, FeedSpot, andto all of you, my readers, for making this happen – I am truly grateful!!

Theofficial Top UK Nature Blog medal awarded by FeedSpot to ShukerNature in April 2025 (© FeedSpot)

Theofficial Top UK Nature Blog medal awarded by FeedSpot to ShukerNature in April 2025 (© FeedSpot)

March 31, 2025

A DICYNODONT DEPICTION?

Life restoration of Dicynodon lacerticeps, a dicynodont from the Late Permian, SouthAfrica (© ДиБгд-Wikipedia –

CC BY 4.0 licence

)

Life restoration of Dicynodon lacerticeps, a dicynodont from the Late Permian, SouthAfrica (© ДиБгд-Wikipedia –

CC BY 4.0 licence

)A farm named La Belle France, situatedat Brackfontein Ridge in the Karoo region of South Africa's Free StateProvince, has long been known for the exquisite cave paintings on the wall of acave in its grounds – and especially for one particular painting dubbed theHorned Serpent, which bears no resemblance to any known animal alive today. Itscurved, elongate, spotted body has four paddle-like limbs and a small head butbearing a pair of very large downward-curving tusks, giving it a resemblance tothe head of a walrus. But there have never been walruses in this area, ever. Sounless it is simply wholly imaginary, a spirit beast, what could this depictedcreature represent?

Cryptozoologists have speculatedwhether it may have been some form of aquatic sabre-tooth tiger, an idea datingback at least as far as Bernard Heuvelmans's writings in his 1978 book Les Derniers Dragons d'Afrique, and whichI have already documented in detail here on ShukerNature.

The 'Horned Serpent' petroglyph (public domain)

The 'Horned Serpent' petroglyph (public domain)

However, a wholly new and very convincingidentity has now been proposed, in a thought-provoking PLoS ONE paper authored by Dr Julien Benoit, from the EvolutionaryStudies Institute and School of Geosciences, at the University of theWitwatersrand, in Johannesburg (click here to access it, and here to access a popular-format articleregarding it in The Conversation). The cave paintings were produced by the Sanpeople, formerly known as the Bushmen of the East, indigenous hunter-gathererswho no longer inhabit this particular region, but were well aware of thewildlife around them and were accomplished artists, portraying such creaturesin their cave paintings. The San left this area in 1835, which therefore meansthat this is the latest date by which the Horned Serpent painting could havebeen produced by them. However, it may have been made much earlier, because theSan had lived here for thousands of years, and in this very same area are countlessfossils that may well provide the answer to the mystery of the Horned Serpent'szoological identity, as Benoit has proposed.

The fossils are mostly of ancientreptiles known as dicynodonts, which became extinct here around 250 millionyears ago, during the Upper Permian Period. The principal species is Dicynodonlacerticeps, averaging 4 ft in total length, whose squat body and fourfairly stout limbs render it relatively undistinguished in appearance – except,that is, for its single pair of very sizeable, downward-curving, tusk-liketeeth. Benoit had previously discovered that the San people inhabiting Lesotho,which neighbours South Africa's Free State, had incorporated depictions offossil dinosaur footprints into their cave paintings there, so he has nowproposed that the South African Karoo's Horned Serpent was their attempt toreconstruct, like veritable proto-palaeontologists, the appearance in life ofthe long-extinct dicynodonts, because its tusked head does bear a distinctresemblance to fossil dicynodont skulls and teeth present in this same area.

A fossil Dicynodonskull (© Ghedoghedo/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

A fossil Dicynodonskull (© Ghedoghedo/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Put another way, it is certainly a most notable coincidence thata mysterious tusked beast should be depicted by indigenous artists in the sameregion where fossil skulls and teeth of a distinctively tusked species are commonlyfound. But that is not all. To quote Benoit:

The body of the tusked animalfrom La Belle France [Horned Serpent], as painted by the San, is strangelyflexed like a banana, a pose that is commonly encountered on fossil skeletonsand is called the "death pose" by palaeontologists. Its body is also coveredwith spots, not unlike the mummifieddicynodonts found in the area whose skin iscovered with bumps.

Personally, therefore, I think it likely that the longstandingmystery concerning what the Horned Serpent cave painting represents, and whoseexistence was first brought to widespread attention almost a century ago, in1930, is now finally solved.

Two of the nowadayspalaeontologically-inaccurate but still historically-significant life-sized dicynodontsculptures created during the early 1850s by English sculptor Benjamin WaterhouseHawkins for display at southeast London's Crystal Palace Park and which, along withmany other sculptures of prehistoric fauna prepared by him, can still be seen todayat Dinosaur Court in Crystal Palace Park; NB - an extensive documentation of their history and also that of the cryptozoological jungle walrus linked to the Horned Serpent petroglyph can be found in my book

ShukerNature Book 3: Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, Jungle Walruses, and Other Belated BlogBeasts

(© Ben Sutherland/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Two of the nowadayspalaeontologically-inaccurate but still historically-significant life-sized dicynodontsculptures created during the early 1850s by English sculptor Benjamin WaterhouseHawkins for display at southeast London's Crystal Palace Park and which, along withmany other sculptures of prehistoric fauna prepared by him, can still be seen todayat Dinosaur Court in Crystal Palace Park; NB - an extensive documentation of their history and also that of the cryptozoological jungle walrus linked to the Horned Serpent petroglyph can be found in my book

ShukerNature Book 3: Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, Jungle Walruses, and Other Belated BlogBeasts

(© Ben Sutherland/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

February 27, 2025

THE TANTALISING TWO-TONGUES IDENTIFIED AFTER ALMOST A CENTURY?

A representation of what atwo-tongues may have looked like based solely upon the original report's verbaldescription of this mystery mammal, created by me using Magic Studio

A representation of what atwo-tongues may have looked like based solely upon the original report's verbaldescription of this mystery mammal, created by me using Magic StudioJust over a yearago, in my Alien Zoo column for the British monthly magazine Fortean Times, I introduced readers to acryptozoological conundrum that had been puzzling me ever since I firstencountered it during the 1990s, and which dated back a further six decades, toa 1930s news report from the periodical ModernWonder.

In December 2024,moreover, I also documented it on ShukerNature (click here to read my blog article) The report,dated 27 May 1939, claimed that some mysterious beasts had been captured by aphotographer in the jungles of Malaya (now Malaysia) and had been shown to someofficials in Manila, capital of the Philippines, but that no-one had been ableto identify them.

They were each saidto be quadrupedal and to weigh approximately 200 lb, to possess a raccoon-likehead (masked?), a furry mole-like pelage (dense and/or dark?), a pair of owl-likeeyes (very large and indicating a nocturnal lifestyle?), an odd dentitioncombining human-like teeth with cat-like teeth, a fondness for bananas, and –by far their most bizarre feature – each animal possessed two tongues! (Hence Ihave dubbed their mystifying species the two-tongues.)

Native to Malaysia and Indonesia,a Sunda slow loris Nycticebus coucang– note the distinctive black mask-like markins encircling its extremely large eyesand its very dense fur (© David Haring. Duke Lemur Center. North Carolina/Wikipedia–

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Native to Malaysia and Indonesia,a Sunda slow loris Nycticebus coucang– note the distinctive black mask-like markins encircling its extremely large eyesand its very dense fur (© David Haring. Duke Lemur Center. North Carolina/Wikipedia–

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

I'd speculated inAZ and on ShukerNature that were it not for their substantial weight and,needless to say, their extraordinary twin-tongued condition, these cryptidsmight conceivably have been Malaysian tarsiers, as those very small andsingle-tongued but decidedly goblinesque creatures always arouse considerable curiosityfrom observers unfamiliar with them.

Having documentedthis mystifying case in various of my writings without eliciting any opinionsfrom readers as to what these animals may be, I now hoped that AZ and ShuikerNatureaficionados might prove more forthcoming. And sure enough, at long last I havereceived a suggestion, made by two different ShukerNature readers whollyindependently of each other, that may finally have solved this tantalising riddle.

One reader gavehis name as Lars Dietz, the other chose to remain anonymous, but both broughtto my attention in December 2024 the fascinating fact that lorises – those big-eyed,nocturnal, densely-furred, fruit-eating, Asian relatives of Africa's pottos andbushbabies, as well as Madagascar's lemurs – possess a veritable second tongue,the sublingua. Consisting of a relatively large, muscular tongue-like structurepositioned beneath the primary tongue, and also possessed by the lorises' above-namedAfrican and Madagascan relatives, and by the tarsiers too, it lacks taste buds,its function instead being to keep clean another dental characteristic of suchcreatures, the toothcomb, which is used in oral grooming. Outwardly, however,the sublingua does look like a second genuine tongue.

In this close-up photograph ofa slow loris's face, its pale, pointed sublingua can be clearly seen projectingout of its mouth beneath its longer, pink-coloured primary tongue (© DavidHaring. Duke Lemur Center. North Carolina/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

In this close-up photograph ofa slow loris's face, its pale, pointed sublingua can be clearly seen projectingout of its mouth beneath its longer, pink-coloured primary tongue (© DavidHaring. Duke Lemur Center. North Carolina/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Consequently, itis easy to understand how a loris – or a tarsier – may have been described as atwo-tongued creature by anyone with no previous experience of it. Having saidthat: as lorises and tarsiers exist in the Philippines as well as in Malaysiait seems strange that they would not have been recognised by officials there.

Also, of course,there is the not inconsiderable matter of the two-tongues' claimed weight of 200lb to explain, which is far greater than that of lorises and tarsiers – unlessthe report had been garbled during its documentation in Modern Wonder, with the animals' true weight having been 200 g, not200 lb. This would compare well with that of lorises and also that of theheaviest tarsiers.

In view of thesublingua's evident anatomical relevance to this crypto-case (not to mention theblack mask-like circles of fur encircling the extremely large eyes of slow lorises,plus their bodies' very dense fur), I feel that some such confusion between themetric and imperial systems of weights may well have occurred, thereby causingthe true taxonomic identity of the two-tongues as either lorises (most probably)or tarsiers to become obscured.

Tarsiers are nothing if notgoblinesque, even otherworldly, in appearance, especially to anyone unfamiliarwith these curious yet harmless creatures (© LDC Inc Foundation/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

/ (©Pieere Fidenci/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence)

Tarsiers are nothing if notgoblinesque, even otherworldly, in appearance, especially to anyone unfamiliarwith these curious yet harmless creatures (© LDC Inc Foundation/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

/ (©Pieere Fidenci/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence)

Moreover, perhapsthe officials who saw these creatures simply weren't well-versed in theircountry's native fauna anyway. It certainly wouldn't be the first time thatthis situation has been true!

My sincere thanksto those two ShukerNature readers for steering me in what I feel sure is theright direction in resolving this curious cryptozoological puzzle after almosta century.

And be sure to clickhere to read my previous ShukerNature articleon this subject.

Another of mymost probably now-obsolete (but still visually-engaging) two-tongues reconstructions,based solely upon the Modern Wonders report'sverbal description of these creatures, and created by me using Magic Studio

Another of mymost probably now-obsolete (but still visually-engaging) two-tongues reconstructions,based solely upon the Modern Wonders report'sverbal description of these creatures, and created by me using Magic Studio

February 26, 2025

"BRING ME THE HEAD OF KING KONG!" – A SHUKERNATURE PICTURE OF THE DAY

Vintagephotograph of a man-made pantomime stage prop in the form of a giant primatehead (but NOT derived from a real, dead animal) (public domain/Wikipedia)

Vintagephotograph of a man-made pantomime stage prop in the form of a giant primatehead (but NOT derived from a real, dead animal) (public domain/Wikipedia)It’s been quite a while since I lastposted a 'ShukerNature Picture of the Day', but this particular photographseemed an ideal candidate for such a role, especially as it's one that I've beenmeaning to blog about for ages, so here it is, together with what I've managedto uncover concerning its nothing if not visually striking subject.

Needless to say, had I encountered thispicture recently I would probably have simply assumed it to be an AI-generatedimage and therefore may not have investigated it, as the head was certainly far too big to be from any type of anatomically-feasible primate, even one of the cryptozoological kind.

In reality, however, I firstencountered it online some years ago (on Wikipedia, if memory serves mecorrectly), and its arresting appearance was such that I decided to do whateverI could to identify exactly what it depicted and where it had originated. Hereis what I discovered.

As indicated by this present ShukerNaturepost's tongue-in-cheek title, parodying the biblical Salome's imperious demand toKing Herod Antipas for John the Baptist's head (served on a platter, which it dulywas!), I had initially wondered whether this public-domain photo may have beenin some way related to the original, classic King Kong monster movie released by RKO Radio Pictures in spring1933, directed by Marian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, and starring FayWray alongside this movie's titular stop-motion mega-star created by celebratedanimator Willis H. O'Brien. Perhaps it was a spare giant ape head for close-upshots, or used for publicity purposes?

Although that idea ultimately provedfalse, I suspect that it nonetheless contains an element of relevance to thelatter movie. For what I finally found out was that the object in this photo isactually a gaff, in this instance specifically a stage prop that had featured in a major pantomime performed just a fewmonths after the release of King Kong,so it seems possible that the prop was inspired by this film, which had proved sucha massive hit worldwide earlier that same year.

Publicityphoto-still of American actress Fay Wray promoting the 1933 film King Kong (public domain)

Publicityphoto-still of American actress Fay Wray promoting the 1933 film King Kong (public domain)

According to an unidentified, tantalizingly-briefnewspaper report published on 11 December 1933 that had contained the photo, whatit depicted was a 4.5-ft-tall giant ape or monkey head made from cardboard andpaper (NOT from the remains of any real, dead animal) that had been speciallyconstructed by a stage props company for a pantomime staged in Glasgow,Scotland, during the winter 1933/34 pantomime season.

Sadly, the report gave no furtherdetails, not even naming the pantomime in question or the theatre where it wasstaged. According to the Panto Archive website's comprehensive listing ofGlasgow pantomime venues and productions (click here to view the entire list), the onlypantomime staged in Glasgow during the 1933/34 season was 'Babes In The Wood',at the Theatre Royal, and featuring veteran Scottish music hall comedian TommyLorne (1890-1935) as its principal star.

Perhaps, therefore, the giant monkey/apehead had appeared in it in the capacity of a guardian to the babes abandoned inthe wood, or possibly as a comic bogeyman-type character. This is onlyspeculation on my part, however, as I have been unable to discover any furtherinformation concerning either the head itself or the pantomime in which itappeared, but I did succeed in locating a second newspaper photo of it. Dating fromthe same period, but this time showing the head of a man inside the prop's gapingmouth and a woman standing alongside it, this second photo can be accessed here. I wonder if this eyecatching effigy still survives somewhere, stored away, perhaps, in the vaults of some theatre or stage props provider?

At any rate, we can all be reassured now by thecomforting knowledge that somewhere deep within the cloud-shrouded Skull Islandof make-believe movie-land, the real King Kong is still striding majestically throughhis stop-motion domain with his huge head held high, still firmly attached to hismighty neck and shoulders, whereas, tragically, the same cannot be said for Johnthe Baptist's.

Speaking of Skull Island: be sure to click here to read my full review of the more recent King Kong-starring monster movie Kong: Skull Island in my film review blog, Shuker In MovieLand.

Mewith a gargantuan statue of King Kong at Wookey Hole's Dinosaur Valley in Somerset, southwest England, on 29 August 2010 (© Dr KarlShuker)

Mewith a gargantuan statue of King Kong at Wookey Hole's Dinosaur Valley in Somerset, southwest England, on 29 August 2010 (© Dr KarlShuker)

February 22, 2025

PRESENTING THE PYRALLIS - BORN (AND BORNE) WITHIN THE FIERY FURNACES OF ANCIENT CYPRUS

Isthis what the fire-sustained pyrallis is said to have looked like in ancientCyprus? This is #1 of ten original pyrallis representations included by me inthis article.

Isthis what the fire-sustained pyrallis is said to have looked like in ancientCyprus? This is #1 of ten original pyrallis representations included by me inthis article.The classical mythology of ancient Greeceis plentifully populated by all manner of famous legendary beasts – fromcentaurs, satyrs, gorgons, and Stymphalian birds to harpies, sirens, theminotaur, and much more. There are also some far less familiar but no lessfascinating examples, including the diminutive but thought-provoking fusion ofherpetology and entomology presented here now – namely, the pyrallis of ancientCyprus.

Also known variously as the pyrausta, pyragones,or pyrotocon, the pyrallis derives all of its names from the Greek word 'pyr',which translates as 'fire', because it is intimately associated with thistraditional fundamental element. According to traditional classical Greeklegend, the pyrallis was a tiny incandescent beast resembling a winged, four-limbed,golden insect but in more recent times it is often represented with a scalyreptilian body and the head of a fire-breathing dragon too.

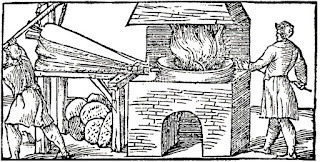

A16th-Century woodcut engraving of a basic copper-smelting furnacelike those in ancient Cyprus (public domain)

A16th-Century woodcut engraving of a basic copper-smelting furnacelike those in ancient Cyprus (public domain)

Moreover, not only was it born in butalso spent its entire life flitting amongst the coruscating flames of copper-smeltingfurnaces in Cyprus, living amid these blazing domains in great swarmsresembling gleaming showers of glowing sparks, borne upon the furnaces'billowing heat and smoke. Should any of these minute insectoids fly beyond theconfines of their infernal abode for even a split-second, however, they wouldinstantly turn to ash and die.

In that respect, the pyrallis, althoughentirely different in form and size, is reminiscent of another creature fromGreek fable, the fire-inhabiting salamander, after which real-life salamandersare named (even though they certainly do not inhabit fire!).

Imageof the fire-inhabiting mythical salamander, created by me using Magic Studio

Imageof the fire-inhabiting mythical salamander, created by me using Magic Studio

Needless to say, it was long assumed thatsuch a fanciful animal as the pyrallis was indeed entirely fabulous, with nobasis in reality. However, as will now be revealed here, although attractingscant scientific attention even at the time of its original presentation in apublished article, and nowadays, 75 years later, having been all but forgotten,there is one compelling line of speculation that seeks to identify this mythicalmini-beast with a certain bona fide species, one whose own intimate associationwith fire may have genuinely inspired the pyrallis legend.

The earliest record relating unequivocallyto the pyrallis as described by me above is a brief passage that can be foundin Chapter 36 (not 42 as sometimes incorrectly claimed) of Book #11 from Naturalis Historia (The Natural History). This is the encyclopaedic magnum opus produced by theeminent 1st-Century Roman scholar/naturalist Pliny the Elder (23/24AD to 79 AD), which consists of 37 books contained within ten volumes.

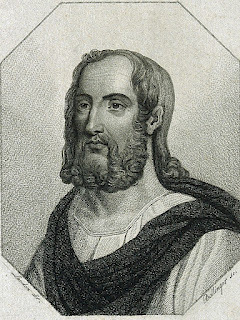

Portraitengraving of Pliny The Elder (public domain)

Portraitengraving of Pliny The Elder (public domain)

In the 1855 English translation of Naturalis Historia prepared by Dr JohnBostock, the relevant passage reads as follows:

Thatelement [fire], also, which is so destructive to matter, produces certainanimals; for in the copper-smelting furnaces of Cyprus, in the very midst ofthe fire, there is to be seen flying about a four-footed animal with wings, thesize of a large fly: this creature is called the "pyrallis," and bysome the "pyrausta." So long as it remains in the fire it will live,but if it comes out and flies a little distance from it, it will instantly die.

Pyrallis#2

Pyrallis#2

True, it was not the first pyrallismention. In his comprehensive work Historyof Animals, celebrated Greek scholar Aristotle (384-322 BC) stated that theturtle dove was at war with the pyrallis. However, he seemingly considered thelatter creature to be merely some form of unspectacular bird, as this mentionwas contained within a paragraph devoted entirely to warfare between differenttypes of familiar bird, such as the owl, crow, raven, kite, green woodpecker, gull,tern, and buzzard. Consequently, it would appear to have no relevance to thefire-sustaining insect-dragon under investigation by me here. (Indeed, variousAristotlean researchers have identified this avian pyrallis as a type ofpigeon, the pygmy dove.)

Conversely, and also confusingly,elsewhere in his same work Aristotle described in some detail a creature thathe did not name but which is evidently one and the same as the pyrallis thatwould be named and documented by Pliny three centuries later.

Aristotlebust, a marble, Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by Lysippos from 330BC (public domain)

Aristotlebust, a marble, Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by Lysippos from 330BC (public domain)

Here is Aristotle's account of hisunnamed version:

Livinganimals are found in substances that are usually supposed to be incapable ofputrefaction…In Cyprus, in places where copper-ore is smelted, with heaps ofthe ore piled on day after day, an animal is engendered in the fire, somewhatlarger than a blue bottle fly, furnished with wings, which can hop or crawlthrough the fire. And…perish when you keep the one away from the fire…Now thesalamander is a clear case in point, to show us that animals do actually existthat fire cannot destroy; for this creature, so the story goes, not only walksthrough the fire but puts it out in doing so…Such is the mode of generation ofthe insects above enumerated.

Pyrallis#3

Pyrallis#3

It is clear that this passage by Aristotledescribing an unnamed blue bottle-sized fire-inhabiting creature was theprimary source utilized by Pliny for his own version, in which said creaturewas referred to by him by name, as the pyrallis (or pyrocausta), and also thatAristotle deemed it to be some type of insect. Less clear, meanwhile, is whyAristotle applied that very same name, pyrallis, to an entirely different,wholly unrelated creature, a kind of bird. All very strange, and bewildering!

Anyway, one subsequent early work alsodocumented the pyrallis, albeit not by that name. This work was Book 2 of De Natura Animalium, a 17-bookcollection of brief accounts and anecdotes concerning natural history, writtenby Roman author Aelian, aka Claudius Aelianus (c175-c235 AD), with a particularemphasis upon extraordinary or fabulous cases.

A vintageclaimed likeness of Aelian (public domain)

A vintageclaimed likeness of Aelian (public domain)

Here is the short passage that he wroteabout creatures that he termed fire-flies but which obviously referred to thepyrallis:

Thatliving creatures should be born upon the mountains, in the air, and in the sea,is no great marvel [I'd beg to differ regarding creatures being born in theair!], since matter, food, and nature are the cause. But that there shouldspring from fire winged creatures which men call 'Fire-flies,' and that theseshould live and flourish in it, flying to and fro about it, is a startlingfact. And what is more extraordinary, when these creatures stray outside therange of the heat to which they are accustomed and take in cold air, they atonce perish. And why they should be born in the fire and die in the air othersmust explain.

Pyrallis#4

Pyrallis#4

Notwithstanding Aelian's naming of themas fire-flies, these mythical entities' fire-generated, fire-inhabitinglifestyle sets them wholly apart from the real-life insects known to us todayas fire-flies, which are bioluminescent lampyrid beetles, and also include thefamiliar glow-worms. For their only connection to fire is the fiery light thatthey emit. Perhaps, therefore, Alien had somehow conflated the legendarypyrallis with the genuine fire-flies and glow-worms.

Whatever the explanation for hisnomenclatural confusion, however, Aelian certainly seemed to believe in theauthenticity of the pyrallis, so might there be a real-life insect known to himthat gave rise to this legendary mini-monster? Such a fascinating notion wasput forward as a very plausible possibility in 1950 by Emile Janssens, via afascinating yet little-known paper published in French by the scientificjournal Latomus, in turn published bythe Société d'Études Latines de Bruxelles, in Belgium.

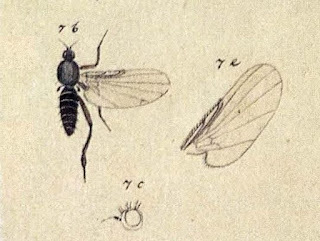

Asmoke fly, Microsania sp., greatlyenlarged (public domain)

Asmoke fly, Microsania sp., greatlyenlarged (public domain)

As Janssens noted in his paper,pyrophilic or pyrophilous (fire-loving) insects are far from unknown. Take, forexample, the aptly-dubbed smoke flies of the genus Microsania, belonging to the taxonomic family Platypezidae, theflat-footed flies. Just a few millimeters long at most, typically hump-backedin appearance, and of global distribution, these diminutive dipterans seem toappear from nowhere wherever there is a fire and smoke, and swarm amidst thefire like motes of black ash, then vanish as swiftly as they appeared once thefire dies and the smoke dissipates.

Their attraction to fire was first scientificallyrecorded by Belgian entomologist G. Severin via a 1921 paper, in which herevealed how, after having sought in vain for any Microsania specimens for 20 years within a particular area ofBelgium, he unexpectedly observed numerous individuals dancing in swarms amidstthe smoke generated by a heath fire in that very same locality, but that wasnot all. Not one specimen could be found more than a few feet (1 m) beyond theperimeter of the fire and its smoke; and once the fire had ceased and its embershad cooled, every last fly disappeared, not a single one remaining in the area.

Thecommon blue bottle fly Calliphoravomitoria (© Shiv's fotografia/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Thecommon blue bottle fly Calliphoravomitoria (© Shiv's fotografia/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

This scenario bears much more than apassing resemblance to that of the pyrallis legend, as Janssens commented inhis paper. Nevertheless, he dismissed these flies as the likely identity forthe latter entity on account of how tiny they are, in stark contrast to theclassical writers quoted by me earlier here all stating that the pyrallis wasthe size of a large blue bottle fly, i.e. Calliphoravomitoria, a very familiar species of blow fly, which measures 1-1.5 cmlong and is therefore considerably bigger than a Microsania fly.

Although far from unknown as notedearlier, out of the more than 1 million insect species currently described byscience (and with countless more still awaiting description) only around 50-60of them are pyrophilic. Of these, moreover, the vast majority are beetles, plusten dipterans (true flies), eight hemipteran bugs, one wasp, and one moth. Twoof the best-known pyrophilic beetles are a pair of European carabid (groundbeetle) species – Sericoda quadripunctata(attracted to severe burning outbreaks) and Pterostichusquadrifoleolatus (to weak burnings).

Sericoda quadripunctata, a European species of pyrophilic carabid (ground beetle) (©YvesBousquet/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 licence

)

Sericoda quadripunctata, a European species of pyrophilic carabid (ground beetle) (©YvesBousquet/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 licence

)By far the most famous and best-studied pyrophilicbeetle species, however, and which was favoured above all other real-lifecreatures by Janssens as the identity of (or at least the inspiration for) the pyrallis,is a certain European species of buprestid wood-boring beetle. Despite itssombre black colouration, Melanophila acuminatais colloquially known as the fire beetle or fire bug, due to its decidedlyfiery lifestyle, in every sense.

For just like the smoke flies, this insectspecies is irresistibly drawn to fire (hence yet another name for it, thefire-chaser beetle) – so much so that whenever there is a forest fire and allother creatures are fleeing away fromit, these beetles are seen fleeing towardsit! Indeed, rural fire fighters are often greatly hindered by large swarms ofthem while trying to extinguish such blazes, to the extent that they often haveto wear special beekeeper attire in order to prevent these beetles from penetratingtheir clothes and biting them!

Anadult fire beetle Melanophila acuminata(© AG Prof. Schmitz/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)

Anadult fire beetle Melanophila acuminata(© AG Prof. Schmitz/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)

Several studies of this bizarre beetle,which is approximately 1 cm long, the size of a blue bottle fly, have uncoveredthe reason for its obsession with fire and the various anatomical accessoriesthat it has evolved to assist it in locating conflagrations. As is so oftentrue in so many disparate walks of life, it all has its basis in sex!

The fire beetle has evolved to copulatespecifically upon the still-burning wood of newly-scorched trees, especiallyconifers, and to lay its eggs beneath the charred bark of such trees, whichthen serves as food for this beetle's white maggot-like larvae once hatched.Even its feet have evolved an asbestos-like resistance to high temperaturesthat enables it to scuttle around unharmed on smoldering wood and sizzling emberstoo hot for a human hand to dare touch.

Melanophila a

cuminata

larva on Pinus sylvestris,the Scots pine (© Gilles San Martin/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Melanophila a

cuminata

larva on Pinus sylvestris,the Scots pine (© Gilles San Martin/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

But how do fire beetles sense thepresence of a fire? Examinations of their micro-anatomy have revealed that justlike certain heat-sensing snakes such as pit vipers and rattlesnakes, thesebeetles possess a pair of thermal infra-red receptors, resembling tiny pits.These sensory organs are present on their thorax's undersurface, eachcontaining a small water droplet that expands when heat is detected, triggeringa nervous system response to follow the heat source.

They are extraordinarily sensitive toheat, enabling the beetles to home in on a fire from very considerabledistances. In fact, one study whose results were published in 2012 estimated viathe use of modeling that this particular species could detect a fire from asfar away as 80 miles (roughly 130 km)!

Pyrallis#5

Pyrallis#5

In addition, there are olfactory organson the antennae of this species that some researchers believe may detect smokeand thereby further assist it in its fire-sensing needs. No doubt such organsexplain instances in which these insects have been known to swarm en masse atAmerican football stadiums during a game, lured there by the thick haze oftobacco smoke resulting from the game's numerous smoking spectators.

Bearing in mind, however, as I'verevealed earlier here, that the fire beetle is not the only known Europeanspecies of pyrophilic beetle, why did Janssens favour it above all of theothers as a possible explanation for the pyrallis legend?

Pyrallis#6

Pyrallis#6

After referring briefly to one of thoseothers, here is what he stated in his paper:

But there is better. We know,thanks to the English entomologist W[illiam]. E. Sharp, the extraordinaryhabits of a Buprestid beetle which flies with the vivacity of a fly and whichhas the size required by the indications of ancient authors. It is Melanophila acuminata.

Pyrallis#7

Pyrallis#7

He thenquoted a very pertinent excerpt concerning Sharp that had appeared in a 1934scientific account written by fellow entomologist A. Collart and published inthe Société Entomologiquede Belgique's Bulletin.Knowing that this species could be found on charred pine tree trunks, Sharp hadset about seeking specimens of it in a Berkshire pine forest where a fire hadrecently broken out. As documented by Collart:

It was only after a longsearch that a single specimen of Melanophilawas caught on a charred stump of Pine; this was a meagre harvest, when, guidedby a distant smoke, Mr. Sharp and the friend who accompanied him arrived at aplace where the fire was still active. Immediately several specimens of Melanophila were captured; some wererunning on ground too hot for the hand to be able to rest on it. Others wereinstalled, often in copula on burning pine stumps or, under a bright Augustsun, flew through puffs of acrid smoke released by the burning peat; and,grilled by the peaty materials on fire, blinded by a suffocating smoke, the tworesearchers made a painful but very fruitful hunt for the Melanophila!

Pyrallis#8

Pyrallis#8

As Janssensjudiciously pointed out, the above description certainly parallels that ofAelian (as well as Pliny's and Aristotle's) for the pyrallis. Moreover, it isreasonable to assume that the fuel used in the copper ore furnaces of Cyprus longago consisted mainly of resinous pine wood.

And whereas firebeetles do not actually die when they eventually depart from the fire and smokethat initially attracted them, they do disappear back into their ruralsurroundings with extraordinary rapidity, plus their dark colouration makesthem difficult to observe when no longer illuminated by the bright glow of afire. So again it is not unreasonable to assume that ancient Cypriot observersassumed that they had simply turned to ash and died.

Pyrallis#9

Pyrallis#9

Consequently,I certainly feel that Janssens's proposal that the pyrallis myth was inspiredby sightings of fire beetles swarming and flying amidst the burning, smoking pinewood fuel in copper ore furnaces to be a tenable one, and it is a great shamethat it did not receive the scientific attention and further investigation thatit so richly deserved.

NB – All pyrallisillustrations included here were created by me using Magic Studio, andrepresent this legendary beast in a variety of different forms, includinginsect-headed, dragon-headed, four-limbed, and six-limbed, all of which are descriptionsthat have been attributed to it by various authors down through the ages.

Pyrallis#10

Pyrallis#10

January 23, 2025

SHEDDING LIGHT UPON THE MYSTERY OF LUMINOUS BIRDS - Part 2: ALL AGLOW WITH SUGGESTED SOLUTIONS!

Isthis what a luminous or glowing owl would look like?

Isthis what a luminous or glowing owl would look like?Sceptics notwithstanding, the phenomenon ofluminous birds whose lengthy history I surveyed recently on ShukerNature inPart 1 of this two-part review (click here to read Part 1) is assuredly genuine, but howcan it be explained? Five principal potential solutions have been suggested byamateur naturalists and professional scientists alike down through the ages,and these are as follows:

1) It is due to thebird having made physical external contact with phosphorescent organisms livingon decayed wood in tree holes

The idea behind this suggested solution –the most familiar and extensively documented of the five under considerationhere – is that such contact would cause phosphorescent bacteria, plants, andfungi growing on the wood to become attached to the bird's feathers, thereby yieldingan area of luminescence upon its plumage.

Howa glowing barn owl with a particularly luminous breast might look

Howa glowing barn owl with a particularly luminous breast might look

However, whereas the parts of a bird'sbody most likely to make contact with wood when entering or exiting a tree holewould be its wings and head (brushing against the rim of the hole), the bodyregion actually exhibiting most (or all) of its perceived luminescence in thosespecimens that have been reported has tended to be the breast, with the wings andhead sometimes giving off little (if any) light.

Also, it must be remembered that glowingexamples of extremely large birds, such as North America's great blue heron Ardea herodias, standing 45-54 inchestall, have been recorded – and it seems highly unlikely that birds of thisstature would (or could) inhabit tree holes.

Agreat blue heron (© Mike Baird/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Agreat blue heron (© Mike Baird/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

In addition, and as its common namesuggests, the barn owl, the most popular identity for luminous owls, prefers toroost in barns or deserted out-houses rather than in tree holes (though it willroost in them if need be).

Yet if this option is nonetheless a viableone in relation to certain bird species, a common phosphorescent fungus likelyto be involved is the honey fungus Armillariamellea – a very abundant, widespread, edible species (or species complex,as is nowadays deemed to be the case) that lives on trees and woody shrubs, andsports bioluminescent mycelia yielding an ethereal greenish-blue glow commonlyreferred to as foxfire.

Thehoney fungus Armillaria mellea (©Stu's Images/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Thehoney fungus Armillaria mellea (©Stu's Images/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Indeed, I remember reading long ago afascinating snippet of information demonstrating just how powerful the foxfire glowof this fungal species can be. Edited by Dilys Breese, and published by the BBCin 1981, the multi-contributor book WildlifeQuestions and Answers included the snippet in question, provided bycorrespondent R. Watling, and which reads as follows:

I have often seen the eerielight of the honey fungus in a tropical rain forest. You see all the leaves andstems and trunks, twenty-five feet tall maybe in an old tree, with thisbeautiful glow, just like a silver lady among the trees. And these fungi caneven take their own photographs! If you set up a camera next to one of them, givenenough exposure time, you will get a picture of the fungus all bright andshiny, taken by its own luminescence.

Schistostega

luminous moss inside a Japanese cave (© Dr TerraKhan/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Schistostega

luminous moss inside a Japanese cave (© Dr TerraKhan/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)