PRESENTING THE PYRALLIS - BORN (AND BORNE) WITHIN THE FIERY FURNACES OF ANCIENT CYPRUS

Isthis what the fire-sustained pyrallis is said to have looked like in ancientCyprus? This is #1 of ten original pyrallis representations included by me inthis article.

Isthis what the fire-sustained pyrallis is said to have looked like in ancientCyprus? This is #1 of ten original pyrallis representations included by me inthis article.The classical mythology of ancient Greeceis plentifully populated by all manner of famous legendary beasts – fromcentaurs, satyrs, gorgons, and Stymphalian birds to harpies, sirens, theminotaur, and much more. There are also some far less familiar but no lessfascinating examples, including the diminutive but thought-provoking fusion ofherpetology and entomology presented here now – namely, the pyrallis of ancientCyprus.

Also known variously as the pyrausta, pyragones,or pyrotocon, the pyrallis derives all of its names from the Greek word 'pyr',which translates as 'fire', because it is intimately associated with thistraditional fundamental element. According to traditional classical Greeklegend, the pyrallis was a tiny incandescent beast resembling a winged, four-limbed,golden insect but in more recent times it is often represented with a scalyreptilian body and the head of a fire-breathing dragon too.

A16th-Century woodcut engraving of a basic copper-smelting furnacelike those in ancient Cyprus (public domain)

A16th-Century woodcut engraving of a basic copper-smelting furnacelike those in ancient Cyprus (public domain)

Moreover, not only was it born in butalso spent its entire life flitting amongst the coruscating flames of copper-smeltingfurnaces in Cyprus, living amid these blazing domains in great swarmsresembling gleaming showers of glowing sparks, borne upon the furnaces'billowing heat and smoke. Should any of these minute insectoids fly beyond theconfines of their infernal abode for even a split-second, however, they wouldinstantly turn to ash and die.

In that respect, the pyrallis, althoughentirely different in form and size, is reminiscent of another creature fromGreek fable, the fire-inhabiting salamander, after which real-life salamandersare named (even though they certainly do not inhabit fire!).

Imageof the fire-inhabiting mythical salamander, created by me using Magic Studio

Imageof the fire-inhabiting mythical salamander, created by me using Magic Studio

Needless to say, it was long assumed thatsuch a fanciful animal as the pyrallis was indeed entirely fabulous, with nobasis in reality. However, as will now be revealed here, although attractingscant scientific attention even at the time of its original presentation in apublished article, and nowadays, 75 years later, having been all but forgotten,there is one compelling line of speculation that seeks to identify this mythicalmini-beast with a certain bona fide species, one whose own intimate associationwith fire may have genuinely inspired the pyrallis legend.

The earliest record relating unequivocallyto the pyrallis as described by me above is a brief passage that can be foundin Chapter 36 (not 42 as sometimes incorrectly claimed) of Book #11 from Naturalis Historia (The Natural History). This is the encyclopaedic magnum opus produced by theeminent 1st-Century Roman scholar/naturalist Pliny the Elder (23/24AD to 79 AD), which consists of 37 books contained within ten volumes.

Portraitengraving of Pliny The Elder (public domain)

Portraitengraving of Pliny The Elder (public domain)

In the 1855 English translation of Naturalis Historia prepared by Dr JohnBostock, the relevant passage reads as follows:

Thatelement [fire], also, which is so destructive to matter, produces certainanimals; for in the copper-smelting furnaces of Cyprus, in the very midst ofthe fire, there is to be seen flying about a four-footed animal with wings, thesize of a large fly: this creature is called the "pyrallis," and bysome the "pyrausta." So long as it remains in the fire it will live,but if it comes out and flies a little distance from it, it will instantly die.

Pyrallis#2

Pyrallis#2

True, it was not the first pyrallismention. In his comprehensive work Historyof Animals, celebrated Greek scholar Aristotle (384-322 BC) stated that theturtle dove was at war with the pyrallis. However, he seemingly considered thelatter creature to be merely some form of unspectacular bird, as this mentionwas contained within a paragraph devoted entirely to warfare between differenttypes of familiar bird, such as the owl, crow, raven, kite, green woodpecker, gull,tern, and buzzard. Consequently, it would appear to have no relevance to thefire-sustaining insect-dragon under investigation by me here. (Indeed, variousAristotlean researchers have identified this avian pyrallis as a type ofpigeon, the pygmy dove.)

Conversely, and also confusingly,elsewhere in his same work Aristotle described in some detail a creature thathe did not name but which is evidently one and the same as the pyrallis thatwould be named and documented by Pliny three centuries later.

Aristotlebust, a marble, Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by Lysippos from 330BC (public domain)

Aristotlebust, a marble, Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by Lysippos from 330BC (public domain)

Here is Aristotle's account of hisunnamed version:

Livinganimals are found in substances that are usually supposed to be incapable ofputrefaction…In Cyprus, in places where copper-ore is smelted, with heaps ofthe ore piled on day after day, an animal is engendered in the fire, somewhatlarger than a blue bottle fly, furnished with wings, which can hop or crawlthrough the fire. And…perish when you keep the one away from the fire…Now thesalamander is a clear case in point, to show us that animals do actually existthat fire cannot destroy; for this creature, so the story goes, not only walksthrough the fire but puts it out in doing so…Such is the mode of generation ofthe insects above enumerated.

Pyrallis#3

Pyrallis#3

It is clear that this passage by Aristotledescribing an unnamed blue bottle-sized fire-inhabiting creature was theprimary source utilized by Pliny for his own version, in which said creaturewas referred to by him by name, as the pyrallis (or pyrocausta), and also thatAristotle deemed it to be some type of insect. Less clear, meanwhile, is whyAristotle applied that very same name, pyrallis, to an entirely different,wholly unrelated creature, a kind of bird. All very strange, and bewildering!

Anyway, one subsequent early work alsodocumented the pyrallis, albeit not by that name. This work was Book 2 of De Natura Animalium, a 17-bookcollection of brief accounts and anecdotes concerning natural history, writtenby Roman author Aelian, aka Claudius Aelianus (c175-c235 AD), with a particularemphasis upon extraordinary or fabulous cases.

A vintageclaimed likeness of Aelian (public domain)

A vintageclaimed likeness of Aelian (public domain)

Here is the short passage that he wroteabout creatures that he termed fire-flies but which obviously referred to thepyrallis:

Thatliving creatures should be born upon the mountains, in the air, and in the sea,is no great marvel [I'd beg to differ regarding creatures being born in theair!], since matter, food, and nature are the cause. But that there shouldspring from fire winged creatures which men call 'Fire-flies,' and that theseshould live and flourish in it, flying to and fro about it, is a startlingfact. And what is more extraordinary, when these creatures stray outside therange of the heat to which they are accustomed and take in cold air, they atonce perish. And why they should be born in the fire and die in the air othersmust explain.

Pyrallis#4

Pyrallis#4

Notwithstanding Aelian's naming of themas fire-flies, these mythical entities' fire-generated, fire-inhabitinglifestyle sets them wholly apart from the real-life insects known to us todayas fire-flies, which are bioluminescent lampyrid beetles, and also include thefamiliar glow-worms. For their only connection to fire is the fiery light thatthey emit. Perhaps, therefore, Alien had somehow conflated the legendarypyrallis with the genuine fire-flies and glow-worms.

Whatever the explanation for hisnomenclatural confusion, however, Aelian certainly seemed to believe in theauthenticity of the pyrallis, so might there be a real-life insect known to himthat gave rise to this legendary mini-monster? Such a fascinating notion wasput forward as a very plausible possibility in 1950 by Emile Janssens, via afascinating yet little-known paper published in French by the scientificjournal Latomus, in turn published bythe Société d'Études Latines de Bruxelles, in Belgium.

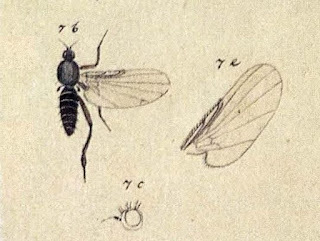

Asmoke fly, Microsania sp., greatlyenlarged (public domain)

Asmoke fly, Microsania sp., greatlyenlarged (public domain)

As Janssens noted in his paper,pyrophilic or pyrophilous (fire-loving) insects are far from unknown. Take, forexample, the aptly-dubbed smoke flies of the genus Microsania, belonging to the taxonomic family Platypezidae, theflat-footed flies. Just a few millimeters long at most, typically hump-backedin appearance, and of global distribution, these diminutive dipterans seem toappear from nowhere wherever there is a fire and smoke, and swarm amidst thefire like motes of black ash, then vanish as swiftly as they appeared once thefire dies and the smoke dissipates.

Their attraction to fire was first scientificallyrecorded by Belgian entomologist G. Severin via a 1921 paper, in which herevealed how, after having sought in vain for any Microsania specimens for 20 years within a particular area ofBelgium, he unexpectedly observed numerous individuals dancing in swarms amidstthe smoke generated by a heath fire in that very same locality, but that wasnot all. Not one specimen could be found more than a few feet (1 m) beyond theperimeter of the fire and its smoke; and once the fire had ceased and its embershad cooled, every last fly disappeared, not a single one remaining in the area.

Thecommon blue bottle fly Calliphoravomitoria (© Shiv's fotografia/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Thecommon blue bottle fly Calliphoravomitoria (© Shiv's fotografia/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

This scenario bears much more than apassing resemblance to that of the pyrallis legend, as Janssens commented inhis paper. Nevertheless, he dismissed these flies as the likely identity forthe latter entity on account of how tiny they are, in stark contrast to theclassical writers quoted by me earlier here all stating that the pyrallis wasthe size of a large blue bottle fly, i.e. Calliphoravomitoria, a very familiar species of blow fly, which measures 1-1.5 cmlong and is therefore considerably bigger than a Microsania fly.

Although far from unknown as notedearlier, out of the more than 1 million insect species currently described byscience (and with countless more still awaiting description) only around 50-60of them are pyrophilic. Of these, moreover, the vast majority are beetles, plusten dipterans (true flies), eight hemipteran bugs, one wasp, and one moth. Twoof the best-known pyrophilic beetles are a pair of European carabid (groundbeetle) species – Sericoda quadripunctata(attracted to severe burning outbreaks) and Pterostichusquadrifoleolatus (to weak burnings).

Sericoda quadripunctata, a European species of pyrophilic carabid (ground beetle) (©YvesBousquet/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 licence

)

Sericoda quadripunctata, a European species of pyrophilic carabid (ground beetle) (©YvesBousquet/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 licence

)By far the most famous and best-studied pyrophilicbeetle species, however, and which was favoured above all other real-lifecreatures by Janssens as the identity of (or at least the inspiration for) the pyrallis,is a certain European species of buprestid wood-boring beetle. Despite itssombre black colouration, Melanophila acuminatais colloquially known as the fire beetle or fire bug, due to its decidedlyfiery lifestyle, in every sense.

For just like the smoke flies, this insectspecies is irresistibly drawn to fire (hence yet another name for it, thefire-chaser beetle) – so much so that whenever there is a forest fire and allother creatures are fleeing away fromit, these beetles are seen fleeing towardsit! Indeed, rural fire fighters are often greatly hindered by large swarms ofthem while trying to extinguish such blazes, to the extent that they often haveto wear special beekeeper attire in order to prevent these beetles from penetratingtheir clothes and biting them!

Anadult fire beetle Melanophila acuminata(© AG Prof. Schmitz/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)

Anadult fire beetle Melanophila acuminata(© AG Prof. Schmitz/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)

Several studies of this bizarre beetle,which is approximately 1 cm long, the size of a blue bottle fly, have uncoveredthe reason for its obsession with fire and the various anatomical accessoriesthat it has evolved to assist it in locating conflagrations. As is so oftentrue in so many disparate walks of life, it all has its basis in sex!

The fire beetle has evolved to copulatespecifically upon the still-burning wood of newly-scorched trees, especiallyconifers, and to lay its eggs beneath the charred bark of such trees, whichthen serves as food for this beetle's white maggot-like larvae once hatched.Even its feet have evolved an asbestos-like resistance to high temperaturesthat enables it to scuttle around unharmed on smoldering wood and sizzling emberstoo hot for a human hand to dare touch.

Melanophila a

cuminata

larva on Pinus sylvestris,the Scots pine (© Gilles San Martin/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Melanophila a

cuminata

larva on Pinus sylvestris,the Scots pine (© Gilles San Martin/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

But how do fire beetles sense thepresence of a fire? Examinations of their micro-anatomy have revealed that justlike certain heat-sensing snakes such as pit vipers and rattlesnakes, thesebeetles possess a pair of thermal infra-red receptors, resembling tiny pits.These sensory organs are present on their thorax's undersurface, eachcontaining a small water droplet that expands when heat is detected, triggeringa nervous system response to follow the heat source.

They are extraordinarily sensitive toheat, enabling the beetles to home in on a fire from very considerabledistances. In fact, one study whose results were published in 2012 estimated viathe use of modeling that this particular species could detect a fire from asfar away as 80 miles (roughly 130 km)!

Pyrallis#5

Pyrallis#5

In addition, there are olfactory organson the antennae of this species that some researchers believe may detect smokeand thereby further assist it in its fire-sensing needs. No doubt such organsexplain instances in which these insects have been known to swarm en masse atAmerican football stadiums during a game, lured there by the thick haze oftobacco smoke resulting from the game's numerous smoking spectators.

Bearing in mind, however, as I'verevealed earlier here, that the fire beetle is not the only known Europeanspecies of pyrophilic beetle, why did Janssens favour it above all of theothers as a possible explanation for the pyrallis legend?

Pyrallis#6

Pyrallis#6

After referring briefly to one of thoseothers, here is what he stated in his paper:

But there is better. We know,thanks to the English entomologist W[illiam]. E. Sharp, the extraordinaryhabits of a Buprestid beetle which flies with the vivacity of a fly and whichhas the size required by the indications of ancient authors. It is Melanophila acuminata.

Pyrallis#7

Pyrallis#7

He thenquoted a very pertinent excerpt concerning Sharp that had appeared in a 1934scientific account written by fellow entomologist A. Collart and published inthe Société Entomologiquede Belgique's Bulletin.Knowing that this species could be found on charred pine tree trunks, Sharp hadset about seeking specimens of it in a Berkshire pine forest where a fire hadrecently broken out. As documented by Collart:

It was only after a longsearch that a single specimen of Melanophilawas caught on a charred stump of Pine; this was a meagre harvest, when, guidedby a distant smoke, Mr. Sharp and the friend who accompanied him arrived at aplace where the fire was still active. Immediately several specimens of Melanophila were captured; some wererunning on ground too hot for the hand to be able to rest on it. Others wereinstalled, often in copula on burning pine stumps or, under a bright Augustsun, flew through puffs of acrid smoke released by the burning peat; and,grilled by the peaty materials on fire, blinded by a suffocating smoke, the tworesearchers made a painful but very fruitful hunt for the Melanophila!

Pyrallis#8

Pyrallis#8

As Janssensjudiciously pointed out, the above description certainly parallels that ofAelian (as well as Pliny's and Aristotle's) for the pyrallis. Moreover, it isreasonable to assume that the fuel used in the copper ore furnaces of Cyprus longago consisted mainly of resinous pine wood.

And whereas firebeetles do not actually die when they eventually depart from the fire and smokethat initially attracted them, they do disappear back into their ruralsurroundings with extraordinary rapidity, plus their dark colouration makesthem difficult to observe when no longer illuminated by the bright glow of afire. So again it is not unreasonable to assume that ancient Cypriot observersassumed that they had simply turned to ash and died.

Pyrallis#9

Pyrallis#9

Consequently,I certainly feel that Janssens's proposal that the pyrallis myth was inspiredby sightings of fire beetles swarming and flying amidst the burning, smoking pinewood fuel in copper ore furnaces to be a tenable one, and it is a great shamethat it did not receive the scientific attention and further investigation thatit so richly deserved.

NB – All pyrallisillustrations included here were created by me using Magic Studio, andrepresent this legendary beast in a variety of different forms, includinginsect-headed, dragon-headed, four-limbed, and six-limbed, all of which are descriptionsthat have been attributed to it by various authors down through the ages.

Pyrallis#10

Pyrallis#10

Karl Shuker's Blog

- Karl Shuker's profile

- 45 followers