Karl Shuker's Blog, page 7

August 2, 2022

A FIFTH TRUNKO IMAGE EMERGES, ALMOST 100 YEARS AFTER TRUNKO ITSELF DID!

Higher-resolution close-up version of the fifth Trunko photograph to be made known to cryptozoologists (© owner unknown, but image dates from early 1920s, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Higher-resolution close-up version of the fifth Trunko photograph to be made known to cryptozoologists (© owner unknown, but image dates from early 1920s, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

As ShukerNature readers will no doubt already know, Trunko is the name that within my 1996 book The Unexplained I light-heartedly coined (but which to my great surprise duly became globally accepted) for the hitherto nameless yet very enigmatic 'sea monster' carcase washed ashore on a beach at the coastal town of Margate, in what is now Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa, during November 1924 (or 1922, according to certain dubious claims), and characterised by its coating of snow-white 'fur' plus a long elephantine trunk-like projection.

Sadly, no tissue samples were taken from this strange specimen for formal scientific analysis before it was washed back out to sea and lost forever; nor, seemingly, were any photographs snapped of it. Consequently, Trunko appeared destined to remain perpetually unidentified, eternally unexplained, but nonetheless inspiring all manner of highly imaginative but often extremely eyecatching artistic representations of what it may have looked like in life – bizarre hairy marine pachyderms bearing no resemblance to anything ever known to have existed on Earth.

William Asmussen's vibrant representation of a living Trunko battling two killer whales, inspired by various eyewitness claims back in 1922 (© William Asmussen)

William Asmussen's vibrant representation of a living Trunko battling two killer whales, inspired by various eyewitness claims back in 1922 (© William Asmussen)

Almost 90 years later, however, in September 2010, German cryptozoological co-researcher Markus Hemmler and I were very startled but delighted to discover no fewer than three Trunko photos, which had been snapped by a Mr A.K. Jones while this curious carcase had lain ashore.

One was featured on the Margate Business Association (MBA) website, the other two had been published in a Wide World Magazine article way back in August 1925 (click hereand here to read my two world-exclusive ShukerNature articles that documented these extraordinary discoveries immediately after they had been made).

A.K. Jones's Trunko photograph that had appeared on the MBA website (originally © A.K. Jones,

but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

A.K. Jones's Trunko photograph that had appeared on the MBA website (originally © A.K. Jones,

but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Yet until now, all three had remained entirely unknown to the cryptozoological community.

Moreover, these photos were of sufficiently good quality for me to be able to recognise that this entity was a globster, i.e. a decomposed whale carcase from which the skeletal contents have fallen away, leaving behind a thick gelatinous matrix of collagen protein, still encased inside the whale's skin sac of rotting blubber, with the carcase's famous 'trunk' most likely an enclosed rib covered in fibrous tissue, and the carcase's white 'fur' being exposed connective tissue fibres.

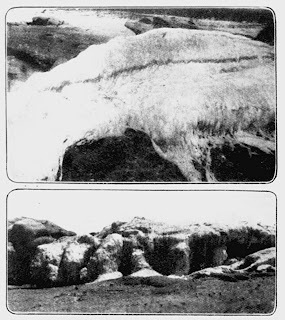

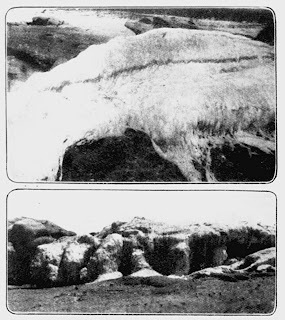

A.K. Jones's two Trunko photograph that had appeared on the Wide World Magazine article of August 1925 (originally © A.K. Jones, but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

A.K. Jones's two Trunko photograph that had appeared on the Wide World Magazine article of August 1925 (originally © A.K. Jones, but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

After more than 80 years, the mystery of Trunko had finally been solved (for full details, see my extensive May 2011 Fortean Times article – the most comprehensive coverage of Trunko's convoluted history ever published, and subsequently republished in ShukerNature Book 1). But that was not all.

In March 2011, I learnt from Markus that a fourth Trunko photograph had been discovered, by Margate-based South African artist and Trunko researcher Bianca Baldi, in the archives of Margate Museum, which showed an amorphous blob that again confirmed Trunko's identity as a globster (click here to read my ShukerNature account of this dramatic find).

The fourth Trunko photograph (© owner unknown, but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

The fourth Trunko photograph (© owner unknown, but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

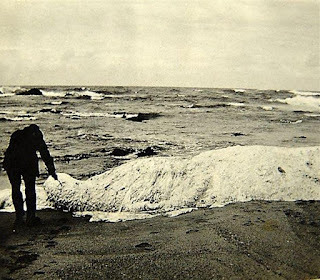

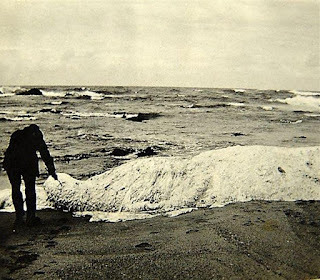

And now, most recently of all, on 19 April 2022 and courtesy yet again of the indefatigable Markus, I was made aware of a fifth Trunko photo. As with the previous quartet, it had been hiding in plain public sight for quite a while.

Markus had discovered that on 4 March 2015, Margate businessman Lencel Celliers had posted in a Facebook group entitled 'MARGATE, Natal, South Africa – NOSTALGIA', a clickable link to a then-online album of vintage Margate-based photographs on the website of a South African news/Information channel called eHowzit that included two Trunko photographs. One of these is the Jones image that had appeared on the MBA website, but the other is entirely new to cryptozoologists.

Lower-resolution full version of the fifth Trunko photograph to be made known to cryptozoologists (© owner unknown, but image dates from early 1920s, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Lower-resolution full version of the fifth Trunko photograph to be made known to cryptozoologists (© owner unknown, but image dates from early 1920s, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

The album provided no details concerning who had snapped this latter photo (it is reproduced here, at the opening to this present ShukerNature article, on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only). As can be seen, it depicts the by-now familiar Trunko form of a huge white globster, but, interestingly, it shows a large fan-shaped projection from the carcase that was not visible in previous Trunko photos but which may explain various previously-mystifying claims by some original Trunko eyewitnesses that the carcase had possessed a lobster-like 'tail' (lobster tails are indeed fan-shaped). In addition, the specific location depicted in this photo, where Trunko was stranded, is revealed to have been the principal Margate beach at Tragedy Bay.

Markus subsequently contacted Mr Celliers on FB for more information regarding this highly significant photo, and Celliers replied that he had obtained both of them from the Margate Museum "when it was still in existence in 2000". (He also provided a link to a Margate-themed YouTube video produced by him and uploaded on 21 July 2012 that includes these same two Trunko pictures – click hereto view it.) Presently unable to identify with certainty which establishment Celliers was alluding to, however, Markus speculates that it may in fact be the Margate Art Museum, but if so, it is still in existence today.

Modern-day view of Margate's principal beach; click picture to enlarge for viewing purposes (© T866/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Modern-day view of Margate's principal beach; click picture to enlarge for viewing purposes (© T866/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Consequently, Markus has now contacted this museum in the hope that it is indeed the correct one and can therefore provide some information concerning this fifth Trunko image.

My sincere thanks as always to Markus Hemmler for so kindly bringing this latest unearthed Trunko photo to my attention and for sharing with me his information concerning it.

My

ShukerNature Book 1

, whose front cover illustration includes a delightful rendition by artist Anthony Wallis of what Trunko might have looked like had it indeed been an exotic species unknown to science – ah, if only… (© Dr Karl Shuker/Anthony Wallis/Coachwhip Publications)

My

ShukerNature Book 1

, whose front cover illustration includes a delightful rendition by artist Anthony Wallis of what Trunko might have looked like had it indeed been an exotic species unknown to science – ah, if only… (© Dr Karl Shuker/Anthony Wallis/Coachwhip Publications)

THE TRUNKO CENTENARY PHOTOGRAPH - A FIFTH TRUNKO IMAGE EMERGES 100 YEARS AFTER TRUNKO ITSELF DID!

Higher-resolution close-up version of the fifth Trunko photograph to be made known to cryptozoologists (© owner unknown, but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Higher-resolution close-up version of the fifth Trunko photograph to be made known to cryptozoologists (© owner unknown, but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

As ShukerNature readers will no doubt already know, Trunko is the name that within my 1996 book The Unexplained I light-heartedly coined (but which to my great surprise duly became globally accepted) for the hitherto nameless yet very enigmatic 'sea monster' carcase washed ashore on a beach at the coastal town of Margate, in what is now Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa, during November 1922, and characterised by its coating of snow-white 'fur' plus a long elephantine trunk-like projection.

Sadly, no tissue samples were taken from this strange specimen for formal scientific analysis before it was washed back out to sea and lost forever; nor, seemingly, were any photographs snapped of it. Consequently, Trunko appeared destined to remain perpetually unidentified, eternally unexplained, but nonetheless inspiring all manner of highly imaginative but often extremely eyecatching artistic representations of what it may have looked like in life – bizarre hairy marine pachyderms bearing no resemblance to anything ever known to have existed on Earth.

William Asmussen's vibrant representation of a living Trunko battling two killer whales, inspired by various eyewitness claims back in 1922 (© William Asmussen)

William Asmussen's vibrant representation of a living Trunko battling two killer whales, inspired by various eyewitness claims back in 1922 (© William Asmussen)

Almost 90 years later, however, in September 2010, German cryptozoological co-researcher Markus Hemmler and I were very startled but delighted to discover no fewer than three Trunko photos, which had been snapped by a Mr A.K. Jones while this curious carcase had lain ashore.

One was featured on the Margate Business Association (MBA) website, the other two had been published in a Wide World Magazine article way back in August 1925 (click hereand here to read my two world-exclusive ShukerNature articles that documented these extraordinary discoveries immediately after they had been made).

A.K. Jones's Trunko photograph that had appeared on the MBA website (originally © A.K. Jones,

but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

A.K. Jones's Trunko photograph that had appeared on the MBA website (originally © A.K. Jones,

but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Yet until now, all three had remained entirely unknown to the cryptozoological community.

Moreover, these photos were of sufficiently good quality for me to be able to recognise that this entity was a globster, i.e. a decomposed whale carcase from which the skeletal contents have fallen away, leaving behind a thick gelatinous matrix of collagen protein, still encased inside the whale's skin sac of rotting blubber, with the carcase's famous 'trunk' most likely an enclosed rib covered in fibrous tissue, and the carcase's white 'fur' being exposed connective tissue fibres.

A.K. Jones's two Trunko photograph that had appeared on the Wide World Magazine article of August 1925 (originally © A.K. Jones, but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

A.K. Jones's two Trunko photograph that had appeared on the Wide World Magazine article of August 1925 (originally © A.K. Jones, but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

After more than 80 years, the mystery of Trunko had finally been solved (for full details, see my extensive May 2011 Fortean Times article – the most comprehensive coverage of Trunko's convoluted history ever published, and subsequently republished in ShukerNature Book 1). But that was not all.

In March 2011, I learnt from Markus that a fourth Trunko photograph had been discovered, by Margate-based South African artist and Trunko researcher Bianca Baldi, in the archives of Margate Museum, which showed an amorphous blob that again confirmed Trunko's identity as a globster (click here to read my ShukerNature account of this dramatic find).

The fourth Trunko photograph (© owner unknown, but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

The fourth Trunko photograph (© owner unknown, but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

And now, most recently of all, on 19 April 2022 and courtesy yet again of the indefatigable Markus, I was made aware of a fifth Trunko photo. As with the previous quartet, it had been hiding in plain public sight for quite a while.

Markus had discovered that on 4 March 2015, Margate businessman Lencel Celliers had posted in a Facebook group entitled 'MARGATE, Natal, South Africa – NOSTALGIA', a clickable link to a then-online album of vintage Margate-based photographs on the website of a South African news/Information channel called eHowzit that included two Trunko photographs. One of these is the Jones image that had appeared on the MBA website, but the other is entirely new to cryptozoologists.

Lower-resolution full version of the fifth Trunko photograph to be made known to cryptozoologists (© owner unknown, but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Lower-resolution full version of the fifth Trunko photograph to be made known to cryptozoologists (© owner unknown, but image dates from 1922, so now likely to be in public domain – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

The album provided no details concerning who had snapped this latter photo (it is reproduced here, at the opening to this present ShukerNature article, on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only). As can be seen, it depicts the by-now familiar Trunko form of a huge white globster, but, interestingly, it shows a large fan-shaped projection from the carcase that was not visible in previous Trunko photos but which may explain various previously-mystifying claims by some original Trunko eyewitnesses that the carcase had possessed a lobster-like 'tail' (lobster tails are indeed fan-shaped). In addition, the specific location depicted in this photo, where Trunko was stranded, is revealed to have been the principal Margate beach at Tragedy Bay.

Markus subsequently contacted Mr Celliers on FB for more information regarding this highly significant photo, and Celliers replied that he had obtained both of them from the Margate Museum "when it was still in existence in 2000". (He also provided a link to a Margate-themed YouTube video produced by him and uploaded on 21 July 2012 that includes these same two Trunko pictures – click hereto view it.) Presently unable to identify with certainty which establishment Celliers was alluding to, however, Markus speculates that it may in fact be the Margate Art Museum, but if so, it is still in existence today.

Modern-day view of Margate's principal beach; click picture to enlarge for viewing purposes (© T866/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Modern-day view of Margate's principal beach; click picture to enlarge for viewing purposes (© T866/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Consequently, Markus has now contacted this museum in the hope that it is indeed the correct one and can therefore provide some information concerning this fifth Trunko image - which, by turning up 100 years after Trunko itself did, surely deserves to be designated as the official Trunko Centenary Photograph!

My sincere thanks as always to Markus Hemmler for so kindly bringing this latest unearthed Trunko photo to my attention and for sharing with me his information concerning it.

My

ShukerNature Book 1

, whose front cover illustration includes a delightful rendition by artist Anthony Wallis of what Trunko might have looked like had it indeed been an exotic species unknown to science – ah, if only… (© Dr Karl Shuker/Anthony Wallis/Coachwhip Publications)

My

ShukerNature Book 1

, whose front cover illustration includes a delightful rendition by artist Anthony Wallis of what Trunko might have looked like had it indeed been an exotic species unknown to science – ah, if only… (© Dr Karl Shuker/Anthony Wallis/Coachwhip Publications)

July 28, 2022

PARKER'S PAPUAN MYSTERY SNAKE, AND A LEGLESS LIZARD OF OZ?

Reconstructing (using a vintage drawing of a black-headed python) the possible appearance of two very distinctive Australian mystery snakes(?) with magenta-coloured heads and yellow bodies that were allegedly encountered in c.1999 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Reconstructing (using a vintage drawing of a black-headed python) the possible appearance of two very distinctive Australian mystery snakes(?) with magenta-coloured heads and yellow bodies that were allegedly encountered in c.1999 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

In his book A Guide to the Snakes of Papua New Guinea (1996), renowned British snake expert Mark O'Shea devoted an entire page to an enigmatic, still-unidentified, but seemingly highly venomous PNG snake of aquatic lifestyle that he has dubbed Parker's snake, in honour of Australian herpetologist Fred Parker, who had first brought this mysterious serpent to scientific attention in his own book The Snakes of Western Province (1982). Both researchers have sought it in the field, but without success, despite specifically visiting the Western Province village of Wipim where it reputedly killed three children (see below). Between them, however, they have collected some valuable information from the local people, who, unsurprisingly, greatly fear this reptile.

In his book, Parker had reported the rapid deaths of three young girls allegedly bitten by this snake while bathing in the Ouwe Creek near Wipim during 1972-73. Other reports of it from further afield have also occurred, but without any attributed deaths. Based upon eyewitness descriptions and other native testimony, Parker's snake is an extremely venomous but also very rare aquatic snake measuring no more than 6.5 ft long, yellowish-brown to brown dorsally and pale yellow to white ventrally, with smooth scales, enlarged ventrals, and a short cylindrical tail. It is said to favour small freshwater swamps and inland streams rather than larger rivers or open swampy grassland. Although it has been seen basking on dry land, it apparently prefers hiding on the muddy bottom. Death resulting from a bite by this snake is very rapid, within just a few minutes, which is much faster than from a taipan or even a sea-snake bite.

Mark O'Shea, 2014 (© Papblak/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Mark O'Shea, 2014 (© Papblak/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

As Mark O'Shea noted in his book, he and Parker have considered a number of possible identities for this mystery serpent. These include New Guinea's mildly venomous dog-faced water snake Cerberus rynchops (with its toxicity presumably exaggerated by locals), the extremely venomous mulga or king brown snake Pseudechis australis (although this Australian elapid has yet to be formally recorded from New Guinea), the small-eyed snake Micropechis ikaheka(another highly venomous elapid but this time known from New Guinea), and even some form of sea-snake or taipan. Yet as Mark freely conceded, none of these wholly corresponds with the local accounts given for it.

Consequently, Parker's snake currently remains an elusive but tantalizing enigma within the ophidian literature; nothing more concerning it has emerged since the publication of Mark's book in 1996, as he confirmed to me during a Facebook communication between us on 22 January 2022.

King brown snake aka mulga snake (© AllenMcC/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

King brown snake aka mulga snake (© AllenMcC/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Not all mysterious snakes are huge, as exemplified by the following tantalisingly vague report of a diminutive form of unidentified serpent from Australia:

I once came across 2 little snakes in a waterhole, somewhere in the outback (can't remember where, it was about nine years ago [i.e. c.1999] and I was travelling all around Oz) but they were about 20 cm [8 in] long with a magenta head and a yellow body. I have never been able to find a picture or find out anything about them, too bad I didn't have a camera!!

Red-naped snake (© Alexandre Roux/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 au licence

)

Red-naped snake (© Alexandre Roux/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 au licence

)

This report was posted onto the Aussie Pythons & Snakes online forum by someone with the username Charlie on 24 January 2008, but it received no response. So as far as I'm aware, no conclusive taxonomic identification of his small yet strikingly-coloured waterhole snakes was ever forthcoming. Nor have I had greater success than Charlie in identifying them.

On 13 November 2021, I posted Charlie's intriguing report on various Facebook groups devoted to cryptozoology to see what response (if any) it elicited. Several identities for the snakes were duly suggested, including the Australian tree snake Dendrelaphis punctulatus, red-naped snake Furina diadema, woma python Aspidites ramsayi, young specimens of the black-headed python A. melanocephalus, and young western brown snakes Pseudonaja nuchalis, but none of these corresponds closely with Charlie's description of the small, very distinctively-hued snakes that he spied.

Black-headed pythons (© Dawson/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)

Black-headed pythons (© Dawson/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)

In view of their miniature size, moreover, it is conceivable that they were not snakes at all, but instead a species of legless lizard, of which there are quite a few endemic to Australia. Some of these, moreover, are deceptively serpentine in outward appearance, especially to those who may not be too familiar with snakes – but yet again I have been unable to obtain pictures of any such reptile that matches those two mystery specimens encountered by Charlie.

An anomalous Aussie mystery snake, or a legendary lizard of Oz? Could it even be that these creatures weren't reptiles at all, but perhaps some form of invertebrate – a species of annelid worm, for instance, or planarian flatworm, the latter of which includes some brightly-coloured Australian species? Any thoughts or suggestions would be greatly welcomed!

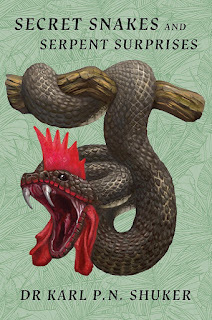

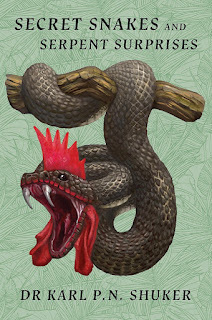

This ShukerNature article is excerpted exclusively from my recent book Secret Snakes and Serpent Surprises.

June 4, 2022

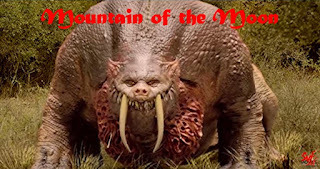

THE MOUNTAIN OF THE MOON AND AN AFRICAN BUNYIP

Photo-still of the dingonek-inspired African bunyip featured in the Bengali blockbuster movie Chander Pahar (© Kamaleshwar Mukherjee/Shree Venkatesh Films – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Photo-still of the dingonek-inspired African bunyip featured in the Bengali blockbuster movie Chander Pahar (© Kamaleshwar Mukherjee/Shree Venkatesh Films – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only) Yes, you read this ShukerNature article's title correctly – an African bunyip, not an Australian one. Allow me to explain.

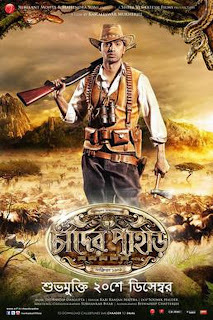

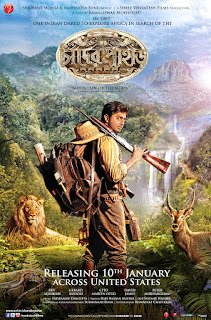

One of the most famous Bengali adventure novels is Chander Pahar (retitled as Mountain of the Moon in subsequent English-language translations), which was written by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, an Indian writer in the Bengali language, and was originally published in 1937. Just under a decade ago, it was turned into a blockbuster Bengali movie that I have long wanted to watch, and finally succeeded in doing so a fortnight ago, thanks to local friend and Amazon Prime subscriber Jane Cooper, who very kindly enabled me to watch it at long last by purchasing it on AP – thanks Jane!

Directed by Kamaleshwar Mukherjee, released in 2013 by Shree Venkatesh Films, and set in the years 1909-1910, Chander Pahar follows the exciting (albeit sometimes positively Munchausenesque!) adventures of a 20-year-old Bengali man named Shankar Ray Choudhuri (played by Indian movie/singing megastar Dev). He has long dreamed of being a derring-do explorer in Africa, but seems destined to spend his life much more mundanely, working as an administrator at the local jute mill in his small Bengali town instead. Happily, however, fate steps in, in the shape of a relative who secures for Shankar a job in Kenya, as the station-master of a tiny railway terminus miles from anywhere.

Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay (public domain)

Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay (public domain)

This posting becomes the vital stepping stone that Shankar has long sought, to set him on the path to becoming a daring African explorer. Many thrilling exploits duly follow, so be sure to click here in order to read my comprehensive plot description and review of Chander Pahar on my companion Shuker In MovieLand blog. Some of these, moreover, are so implausible that Baron Munchausen himself may well have thrown up his hands in despair!

However, the movie's principal focus is Shankar's eventful journey with an older, veteran Portuguese explorer named Diego Alvarez (played by celebrated South African actor Gérard Rudolf) to an inhospitable and virtually inaccessible arid land of high hills and even higher mountains known as the Richtersveld, situated in the northwestern corner of what is today South Africa's Northern Cape province. They are seeking a legendary diamond mine supposedly hidden inside a cave deep within a mysterious Richtersveld mountain known as Chander Pahar – the Mountain of the Moon.

According to local legend, however, this diamond mine is fiercely guarded by the cave's monstrous inhabitant – a gigantic beast still-undescribed by science, but which for reasons never explained either in this movie or in Bandyopadhyay'soriginal novel is known here as the bunyip (despite the latter name being in reality an aboriginal name specifically applied to Australia's most famous indigenous mystery beast!). It turns out that the bunyip has already killed one explorer who accompanied Alvarez during an earlier attempt by him to locate the mine and relieve it of some of its hidden treasures. Will history repeat itself during this latest expedition, in which Shankar is now Alvarez's companion? I'll leave you to read up the full storyline here on my Shuker In MovieLand blog, and concentrate now in this ShukerNature article upon this movie's cryptozoology content – the bunyip.

Three more photo-stills of the ferocious bunyip (© Kamaleshwar Mukherjee/Shree Venkatesh Films – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Three more photo-stills of the ferocious bunyip (© Kamaleshwar Mukherjee/Shree Venkatesh Films – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Chander Pahar has proved hugely popular – having grossed US$ 3.41 million worldwide so far, it is the second highest grossing Bengali movie of all time (indeed, the only Bengali movie to exceed its takings is Amazon Obhijaan, released in 2017, which is itself a sequel to Chander Pahar, once again centering upon the character of Sankhar, but this time the action takes place in South America). Nevertheless, it has not been without its critics, especially among literary purists who believe that it has taken too many liberties in adapting Bandyopadhyay's novel for the big screen – but none more so than with its presentation of the bunyip.

In the novel, the bunyip is never directly seen – a shadow of it moving outside the tent of Shankar and Alvarez one evening is as much as is offered to the readers, leaving the rest to their imagination. In contrast, this movie presents the viewers with a truly memorable CGI bunyip in all its hideous glory, and gory activity, but which some reviewers have denigrated for destroying the monster's mystique, and others for what they considered to be its inferior quality (similar criticisms regarding their quality, or lack of it, have also been aimed at a CGI-engendered volcanic eruption).

As revealed here via the above series of photo-stills, the bunyip is undeniably a startling creation – unlike any beast known to science, that's for sure. A waddling, obese abomination with an exceedingly long whip-like tail, plus a huge and revoltingly vascular dewlap hanging down from its throat that it seems in permanent danger of tripping over when it galumphs after one of its potential human victims, plus a pair of truly enormous vertical fangs that any prehistoric sabre-toothed cat would have given its high teeth for (so to speak!). (In fact, a Kindle e-book edition of Bandyopadhyay's novel actually depicts the bunyip on the front cover as a bona fide living sabre-tooth.)

A Kindle edition of Bandyopadhyay's novel Chander Pahar in which the bunyip is depicted as a living sabre-tooth (© Kindle – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

A Kindle edition of Bandyopadhyay's novel Chander Pahar in which the bunyip is depicted as a living sabre-tooth (© Kindle – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Interestingly, however, this terrifying apparition does recall a traditional African mystery beast known as the dingonek (click here to read my extensive ShukerNature article surveying this and various other comparable African cryptids, the so-called jungle walruses). Moreover, the dingonek is actually mentioned in Bandyopadhyay's novel in addition to the bunyip. In contrast, as noted earlier, I have yet to discover why Bandyopadhyay applied the name of an exclusively Australian water monster to his terrestrial African mystery beast.

According to traditional African lore, conversely, the dingonek is amphibious in nature, i.e. both an adept swimmer in rivers and a formidable adversary on land – so why didn't Bandyopadhyay simply call his monster the dingonek instead of distinguishing it from the latter? Notwithstanding this etymological enigma, there is no denying that the climactic scene featuring a veritable duel to the death between Shankar's inventive brain and the bunyip's immense brawn is a highlight of the entire movie.

So, if you'd like to experience for yourself a glimpse of the thrills and spills that Shankar experiences during his search for the Mountain of the Moon and its hidden diamonds, be sure to click hereto watch an official Chander Pahartrailer on YouTube showcasing its very stirring title song. (You can also watch the entire movie free here on YT, but only in the form of an Odia-language version with no English subtitles, sadly.) And don't forget to click hereif you'd like to view an excerpt from Shankar's chilling confrontation with the belligerent bunyip! And for further details regarding the dingonek and other African sabre-toothed cryptids, check out my recent book Mystery Cats of the World Revisited.

Publicity posters for the original Bengali (top) and American (bottom) cinema releases of Chander Pahar (© Kamaleshwar Mukherjee/Shree Venkatesh Films – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Publicity posters for the original Bengali (top) and American (bottom) cinema releases of Chander Pahar (© Kamaleshwar Mukherjee/Shree Venkatesh Films – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

May 12, 2022

THE PICHU-CUATE – IS A TINY BUT TERRIFYING CRYPTO-SNAKE RESEMBLING KIPLING'S KARAIT ALIVE AND WELL AND LIVING IN AMERICA?

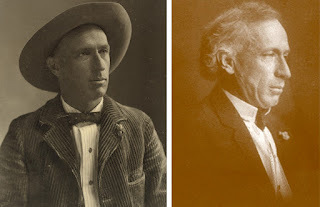

Two photographs of Charles Fletcher Lummis – a pichu-cuate eyewitness who lived to tell the tale, literally, documenting this sinister serpent in his book The King of the Broncos (public domain)

Two photographs of Charles Fletcher Lummis – a pichu-cuate eyewitness who lived to tell the tale, literally, documenting this sinister serpent in his book The King of the Broncos (public domain) Some time ago, I investigated a mysterious, highly-venomous mini-snake named Karait – a memorable albeit short-lived, mongoose-slain character briefly included by Rudyard Kipling in his story 'Rikki-Tikki-Tavi', which was contained in the first of his two Jungle Book novels. Kipling never specified Karait's taxonomic identity. However, as I revealed in my extensive ShukerNature coverage (click hereto read it), this dust-dwelling yet deadly snakeling may have been based upon the Indian saw-scaled viper Echis carinatus.

But that is not all. For it is nothing if not intriguing that a cryptozoological snake bearing a remarkable resemblance both morphologically and behaviourally to Kipling's Karait has been reported from New Mexico and Arizona in the southwestern USA, as brought to my attention recently by American herpetologist/cryptozoologist Chad Arment.

Indian saw-scaled viper Echis carinatus (public domain)

Indian saw-scaled viper Echis carinatus (public domain)

Known as the pichu-cuate – allegedly an Aztec name, in turn suggesting that knowledge of this snake dates back many centuries – it is described as being a tiny species of viper, no bigger or thicker than a normal lead pencil, bearing a pair of small horns above its eyes (supra-ocular), and is a nondescript grey dorsally, rose-pink ventrally, but more venomous than any other North American snake. Extremely rare but also inordinately aggressive, the pichu-cuate supposedly spends its time concealed in sand and dust, sometimes with just its triangular head visible, but will not hesitate to bite anything or anyone that touches it, whether deliberately or inadvertently, which almost invariably leads to its victim's exceedingly rapid, agonizing death. There are claims that people who have been bitten on the hand or a finger by a pichu-cuate have swiftly cut (or shot) off the wounded appendage in the desperate hope of saving their life by preventing this snake's highly virulent venom from travelling further into their body.

The only venomous snakes on record from New Mexico and Arizona are rattlesnakes and coral snakes, which certainly do not resemble the pichu-cuate. Moreover, the morphological and behavioural description presented above for the latter cryptozoological serpent does not match that of any snake species known to exist in these two U.S. states.

First edition (1897) of Lummis's book The King of the Broncos (public domain)

First edition (1897) of Lummis's book The King of the Broncos (public domain)

This diminutive but highly dangerous Karait-like snakeling was first brought to widespread attention by newspaper writer Charles Fletcher Lummis in his compilation book of traditional New Mexican lore The King of the Broncos (1897), in which he related how a young Mexican shepherd named Claudio was apparently bitten on the thumb by a pichu-cuate and was able to save his own life only by shooting off his thumb to prevent the snake's virulent, swift-acting venom from spreading into his body. Moreover, Lummis subsequently claimed to have personally encountered a pichu-cuate on three separate occasions, and on the first of these to have even killed it, whose body he then examined in detail. Regrettably, however, he didn't retain it afterwards for scientific scrutiny. Lummis described its colouration as leaden grey dorsally, matching the sand in which it had been hiding, but rosy-red ventrally, like a conch shell's aperture. Its tiny fangs were no more than one eighth of an inch long, but moveable, slotting into grooves in the roof of its mouth when not about to strike.

In his own book Cryptozoology: Science & Speculation (2004), Chad Arment devoted a chapter to the pichu-cuate, in which he documented Lummis's coverage of it. However, he pointed out that the name 'pichu-cuate' and variations of it are also used in the southwestern USA and Mexico non-specifically, for any snakes deemed by locals to be venomous (regardless of whether they actually are). Hence it is not applied exclusively to this one particular, cryptic serpent.

Cryptozoology: Science & Speculation

by Chad Arment (© Chad Arment/Coachwhip Publications – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Cryptozoology: Science & Speculation

by Chad Arment (© Chad Arment/Coachwhip Publications – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Equally, however, Lummis's mention of the latter's fangs slotting into grooves in the roof of its mouth when not striking is significant, because in North America the only front-fanged venomous snakes with fangs that can move are viperids, thereby eliminating elapids from consideration, as well as rear-fanged colubrids. Also informative is his mention of the pichu-cuate's supra-ocular horns, because as noted by Chad, only four known Latin American snakes possess them. Moreover, two of these, the sidewinder Crotalus cerastes and the eyelash viper Bothriechis schlegelii, can be instantly eliminated, because the former was well known to Lummis, and the latter is arboreal and too colourful. This leaves only the Mexican horned pit viper Ophyracus undulatus and the montane pit viper Porthidium melanurum. Of these two, the former provides the closer match morphologically, but geographically it is not known to exist anywhere near New Mexico or Arizona.

Consequently, Chad concluded his coverage of the pichu-cuate by pondering whether either O. undulatus previously exhibited a broader distribution range than it does today, extending into those two U.S. states, or a small, undescribed viper species formerly inhabited them, and may perhaps still do so today? The following details suggest that this might be true.

Mexican horned pit viper (© Eugenio Padilla/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Mexican horned pit viper (© Eugenio Padilla/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

On 6 May 1984, in his regular 'New Mexican Scrapbook' column published by the El Paso Times, Marc Simmons recalled Lummis's documentation of the pichu-cuate almost a century earlier, and then added some very intriguing, modern-day information of his own. During his travels around New Mexico, Simmons had mentioned the pichu-cuate to various old-timers, but the name meant nothing to them. However, they did tell him about an enigmatic snake known to them as the nino de la tierra ('child of the earth') that sounded suspiciously similar to the pichu-cuate. For it is said to be a small but very deadly, vicious snake that buries itself in the sand, and fatally strikes anyone who sits or lies in that place. But that is not all.

A couple of years earlier, Simmons saw a friend who had been hiking in the rocky foothills of central New Mexico's Ortiz Mountains. The friend mentioned that in a dry arroyo (steep-sided gulley) he had encountered a small grey snake with a triangular head, which in spite of its diminutive size had given him such a chill that he'd instinctively backed away straight away. So perhaps the pichu-cuate (aka nino de la tierra?) is more than just a myth after all.

Marc Simmons's El Paso Times column of 6 May 1984 documenting the nino de la tierra, which may be one and the same as the pichu-cuate – please click this picture to enlarge it for reading purposes (© Marc Simmons/El Paso Times – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Marc Simmons's El Paso Times column of 6 May 1984 documenting the nino de la tierra, which may be one and the same as the pichu-cuate – please click this picture to enlarge it for reading purposes (© Marc Simmons/El Paso Times – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Lastly, there may be some further information concerning the perplexing pichu-cuate hidden away in the collection of photographs and artwork by Lummis that is preserved at the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles, California. Time, therefore, for some enterprising Californian cryptozoologist to seek an opportunity to examine them there?

This ShukerNature blog article is excerpted exclusively from my new book Secret Snakes and Serpent Surprises, published by Chad Arment's own company, Coachwhip Publications. It can be obtained hereat Amazon UK and hereat Amazon USA. More information concerning it is available via its own dedicated page hereon my official website.

Secret Snakes and Serpent Surprises

(2022) (© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)

Secret Snakes and Serpent Surprises

(2022) (© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)

April 29, 2022

LET'S ALL DO THE KUNGA!

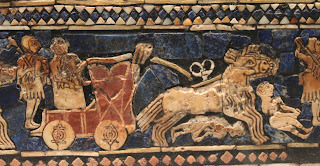

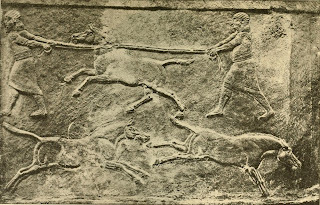

Detail from 'War' panel of Standard of Ur mosaic, c2600 BCE, depicting kungas pulling 4-wheeled battle-wagon (© Zunkir/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0

)

Detail from 'War' panel of Standard of Ur mosaic, c2600 BCE, depicting kungas pulling 4-wheeled battle-wagon (© Zunkir/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0

) It's always good to learn of a 'new' animal, even if it turns out to be one that actually existed four and a half millennia ago! And so, with no further ado, please welcome to ShukerNature the kunga.

Depicted in Mesopotamian art and referred to in cuneiform writings dating back 4500 years from the Fertile Crescent region of the Middle East, the long-vanished kunga was a powerful horse-like creature that was used as a draft animal to pull war wagons into battle and royal chariots during ceremonial parades. However, it has long been a puzzle to archaeologists and zoologists alike.

Close-up of a kunga, as depicted in a detail from 'War' panel of Standard of Ur mosaic, dating from c2600 BCE (© Agricolae/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0

)

Close-up of a kunga, as depicted in a detail from 'War' panel of Standard of Ur mosaic, dating from c2600 BCE (© Agricolae/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0

)

This is because the domestic horse Equus caballus was not introduced into this region until 4000 years ago, and the only known equine beasts that did exist there at the time of the kunga were the domestic donkey E. africanus asinus and the Syrian wild ass (aka the hemippe) E. hemionus hemippus, both of which were smaller and far less sturdy than the kunga. So what was it?

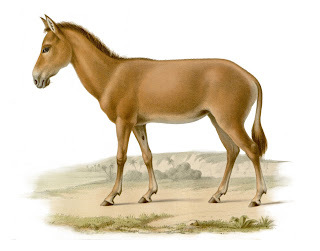

A beautiful vintage colour painting by French artist Georges Severeyns of a Syrian wild ass (the smallest type of modern-day wild equid known to science), in Nouvelles Archives du Muséum d'histoire Naturelle, 1869 (public domain)

A beautiful vintage colour painting by French artist Georges Severeyns of a Syrian wild ass (the smallest type of modern-day wild equid known to science), in Nouvelles Archives du Muséum d'histoire Naturelle, 1869 (public domain)

Unlike many mystery beasts, there are actually physical, tangible remains of the kunga in existence, because as it was such a valuable, useful work beast, specimens were sometimes buried alongside persons of high social status, with several kunga skeletons having been discovered at the northern Syrian burial complex of Umm el-Marra. Unfortunately, however, the bones of kungas, donkeys, wild asses, and horses as well as mules and other equine hybrids, all look very similar, so although kunga bones have been examined, no conclusive identification of what the kunga actually was has ever resulted – until earlier this year.

In January 2022, published research in the journal Science Advances revealed that DNA samples had been extracted from the bones of one buried kunga specimen from Umm el-Marra and subjected to comparative sequencing analyses with other equine forms. These analyses confirmed that it was a hybrid – most probably the offspring of an interspecific mating between a male Syrian wild ass and a female domestic donkey.

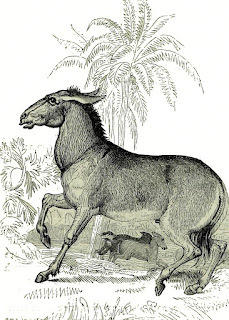

Vintage engraving from 1841 depicting some Syrian wild asses in the wild state (public domain)

Vintage engraving from 1841 depicting some Syrian wild asses in the wild state (public domain)

Moreover, because such matings would not occur naturally, and as the kunga, being a hybrid, was almost certainly sterile (just like the mule), male wild asses would need to have been deliberately captured and mated with female domestic donkeys on a regular basis in order to perpetuate the kunga strain 4500 years ago in the Fertile Crescent – thereby making the kunga the earliest recorded human-engineered hybrid. But when the horse was introduced here 500 years later, the kunga was no longer needed, so the breeding of it ceased, and this remarkable creature duly vanished from existence.

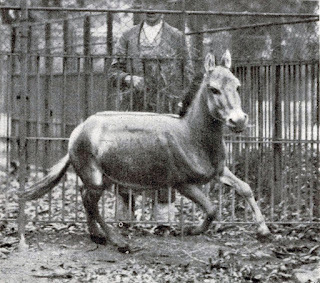

Syrian wild ass being captured by Assyrians, 7th Century BCE art found at Nineveh (Wikipedia/no restrictions)

Syrian wild ass being captured by Assyrians, 7th Century BCE art found at Nineveh (Wikipedia/no restrictions)

Of course, one could ask why, now that the kunga's precise hybrid nature is finally known, scientists are not excitedly proclaiming "Let's all do the kunga – let's resurrect it!", by once again mating male Syrian wild asses with female domestic donkeys. The answer is as tragic as it is simple – no such restoration can take place because the kunga's paternal progenitor, the Syrian wild ass, is itself now extinct, as a result of over-hunting, with the last two known specimens both dying in 1927.

So unless the kunga and/or the Syrian wild ass can be recreated via genetic means in the laboratory one day, the kunga is doomed forever to remain nothing more vital than a collection of long-buried bones, a few brief mentions in cuneiform script, and some preserved images in ancient art. RIP.

A trio of poignant photographs depicting one of the world's last known Syrian wild asses, a specimen living at Vienna's Tiergarten Schönbrunn in 1915, plus one photograph (at bottom of photo-column) of a Syrian wild ass at London Zoo in 1872 (public domain)

A trio of poignant photographs depicting one of the world's last known Syrian wild asses, a specimen living at Vienna's Tiergarten Schönbrunn in 1915, plus one photograph (at bottom of photo-column) of a Syrian wild ass at London Zoo in 1872 (public domain)

April 27, 2022

MAPPING OUT THE NANDI BEAR

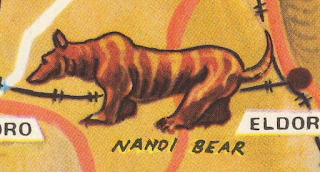

Close-up of the Nandi bear depiction on John McKenzie's 1961 map East Africa (© John McKenzie – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Close-up of the Nandi bear depiction on John McKenzie's 1961 map East Africa (© John McKenzie – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Last year on ShukerNature, in my extensive documentation of what may well be the single most significant episode ever recorded concerning Kenya's most infamous cryptid (click here to read my blog article), the ferocious Nandi bear, I made particular reference to an article on this elusive creature by Gordon Boy that had been published in the October-November 1998 issue of the periodical SAFARI Magazine.

However, in his SAFARI article, Boy included one additional but fascinating Nandi bear nugget that I specifically didn't allude to in my own. This was because I felt that it deserved its very own, separate coverage on ShukerNature (and also because I wanted to research it further first, which I have since done). So here it is now.

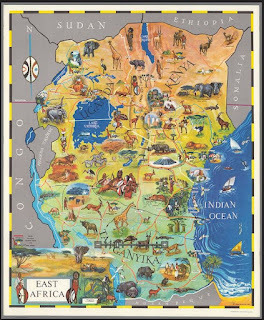

East Africa

, John McKenzie's map that contains the tantalizing Nandi bear depiction

(© John McKenzie – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

East Africa

, John McKenzie's map that contains the tantalizing Nandi bear depiction

(© John McKenzie – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

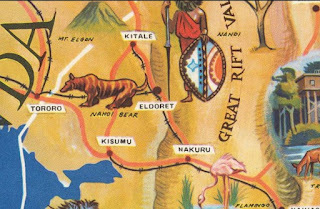

Boy stated that an illustrated full-colour map of East Africa by John McKenzie and simply entitled East Africa (see above scan of it) included a depiction of a strange-looking creature that was actually labeled on it as a Nandi bear. He also stated that the map had been produced in 1952. In reality, however, when I researched this item, I discovered that it had actually been produced in 1961, not 1952, in Nairobi, Kenya; its printer/engraver was East African Standard Ltd.

Boy included a reduced-size reproduction of the entire map in his article (the map's full size is 70 cm by 57 cm), but this reproduction is not big enough for the individual animal depictions in it to be anything other than minuscule. When enlarged, however, they are all rendered clear enough to be readily identifiable with known species – all, that is, except for the Nandi bear depiction, which does not resemble any species currently known to science. Nor, for that matter, does it correspond with any eyewitness description of the Nandi bear.

Nandi bear depiction shown in situ geographically on McKenzie's map East Africa

(© John McKenzie – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Nandi bear depiction shown in situ geographically on McKenzie's map East Africa

(© John McKenzie – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

To quote Boy's brief account of it:

On McKenzie's map, the Nandi bear illustration appears north of Eldoret, on the Uasin Gishu Plateau [in western Kenya]. The illustration shows a massive, dog-like quadruped, with short hair, of a banded brown-and-yellow colour, and with very stocky limbs, a humped back, and a sharply pointed snout. But what is the Nandi bear doing here? It is, after all, the only creature depicted on this map whose existence, even now, has not been verified by science. Or was its inclusion just a mischievous prank on the map-maker's part? The legend of the Nandi bear is not without its pranksters...

This is very true. However, tempering Boy's above statement is another one made by him when introducing his account of McKenzie's map:

The Nandi bear is pictured on some of the old illustrated wildlife maps of East Africa, published during the Colonial era.

In short, there are other old maps out there somewhere that also contain Nandi bear depictions, which in turn reduces the possibility that its included portrayal on the McKenzie example was merely a prank. Needless to say, I have sought to uncover such maps, but as yet I have not succeeded in doing so. Consequently, if anyone reading this ShukerNature blog article of mine knows of any or can offer relevant information concerning them, I'd greatly welcome details.

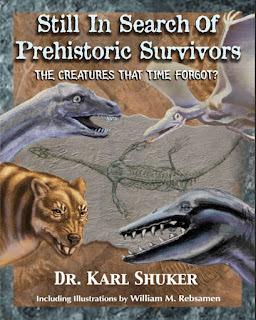

For the most comprehensive modern-day coverage of the Nandi bear in published form, be sure to check out my book Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors.

April 4, 2022

'SECRET SNAKES AND SERPENT SURPRISES' - MY BRAND-NEW, 33RD BOOK IS HERE TO FASCINATE YOU!

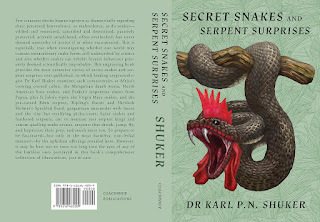

Front cover of Secret Snakes and Serpent Surprises, depicting the crowing crested cobra as based upon eyewitness descriptions (© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)

Front cover of Secret Snakes and Serpent Surprises, depicting the crowing crested cobra as based upon eyewitness descriptions (© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)

My latest thematic cryptozoology book is finally here, my 33rd book in total, and devoted to a subject that has never previously received book-length treatment.

Few creatures divide human opinion so diametrically regarding their perceived benevolence, or malevolence, as do snakes – the eternally-cursed serpent kind according to Christianity, the most divine and blessèd of reptiles according to Hinduism, vilified and venerated, sanctified and demonised, passively protected, actively annihilated, often overlooked, but never deemed not worthy of notice if or when encountered.

The above is especially true, moreover, when investigating whether our world may contain extraordinary snake forms still undescribed by science and also whether snakes can exhibit bizarre behaviour presently deemed scientifically improbable.

Published by Coachwhip Publications, this uniquely engrossing book provides the most extensive survey of secret snakes and serpent surprises ever published, in which I examine such varied envenomed and constricting controversies as Africa's crowing crested cobra, mystery snakes of the Mediterranean lands, the Mongolian death worm, North America's boss snakes, and Parker's serpentine slayer from Papua, plus St John's viper, the Virgin Mary snakes, and the pre-cursed Eden serpent, Kipling's Karait and Sherlock Holmes's Speckled Band, gargantuan anacondas with horns and the tiny but terrifying pichu-cuate, hairy snakes and feathered serpents, Glycon the talking horse-headed ophidian deity of ancient Rome and venerated king cobras, not to mention vast serpent kings and venom-quelling snake-stones, serpents that shriek, jump, fly, and hypnotise their prey via fatal fascination, plus so much more.

So prepare yourself to be duly fascinated – but only in the most harmless, non-lethal manner! – by the ophidian offerings revealed here. Nevertheless, it may perhaps be best not to stare for too long into the eyes of any of the limbless ones portrayed within this book's comprehensive collection of illustrations, just in case...

Secret Snakes and Serpent Surprises is officially published in 12 April 2022, but can be pre-ordered hereon Amazon UK and hereon Amazon USA. It is also available on Barnes & Noble's website and can be ordered directly through all good bookstores too. And be sure to check out its dedicated page hereon my official website for more information concerning it.

The complete wraparound cover of Secret Snakes and Serpent Surprises, depicting the crowing crested cobra as based upon eyewitness descriptions; click picture to enlarge for reading purposes (© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)

The complete wraparound cover of Secret Snakes and Serpent Surprises, depicting the crowing crested cobra as based upon eyewitness descriptions; click picture to enlarge for reading purposes (© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)

March 21, 2022

'OF BOOKS AND BEASTS', BY MATT BILLE - A SHUKERNATURE BOOK REVIEW

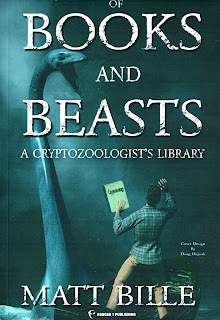

Of Books and Beasts: A Cryptozoologist's Library

by Matt Bille (Hangar 1 Publishing: no place of publication or publication date included [November 2021]) (© Matt Bille/Hangar 1 Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Of Books and Beasts: A Cryptozoologist's Library

by Matt Bille (Hangar 1 Publishing: no place of publication or publication date included [November 2021]) (© Matt Bille/Hangar 1 Publishing – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

It's been a while since I last reviewed any notable cryptozoological publications on ShukerNature, so here are my thoughts concerning one that I received recently.

Back in the 1990s and originally assisted by fellow bibliophile Steven Shipp, I prepared a bibliography of cryptozoology books that was published in issues 6, 7, and 8 of the Centre for Fortean Zoology's periodical Animals and Men. It proved so popular among readers and crypto-researchers alike that, since then, I have periodically updated and expanded it, so that it currently contains many hundreds of entries divided into several sections, and it can nowadays be directly accessed online here, within my official website.

Until last November, however, there had never been a book devoted entirely to reviews of cryptozoological books and related subject matter, which thereby constituted a notable gap in the literature appertaining to mystery beasts. But all of that changed when Matt Bille's Of Books and Beasts: A Cryptozoologist's Library was brought out in both hard-copy and e-book format by Hangar 1 Publishing.

Already known for two previous non-fiction books devoted to current and former cryptids alike as well as his longstanding interest in such creatures, Bille has provided a most valuable service in compiling this third offering, which for the most part consists of cryptozoological book reviews penned by him that originally appeared on his Matt's Sci/Tech Blog, plus a number of additional ones specially written for this book in order to render his coverage of the literature more comprehensive.

This 311-page book is divided into four sections: Cryptozoology Books; Related Sciences; Crypto-Fiction; and A Marvelous Miscellany. There is also an explanatory introduction, plus a couple of afterwords, acknowledgements, and an index/bibliography. Apart from the wonderful front-cover picture (cover design by Doug Hajicek), there are no illustrations, but these are not really necessary in a book of this nature.

The Cryptozoology Books section, which by definition is the crux of this entire publication, follows on from the book's detailed introduction, spans pp. 1-123 (approximately one third of the total content), and is divided into five subsections. These are: A Basic Library of Cryptozoology (which includes reviews of books that Bille deems essential, seminal works of cryptozoology); Primates (reviewed books devoted to the likes of the yeti, bigfoot/sasquatch, and other man-beasts or ape-men); Land Animals (includes reviewed books documenting all manner of – mostly – terrestrial cryptids, including mystery cats, thylacine, and putative mammoths, but also mothman and various amphibious Congolese monsters like the mokele-mbembe and emela-ntouka); Lake and Sea Creatures (reviewed books researching freshwater monsters, sea serpents, other marine mystery beasts); and Others (reviews of general cryptozoology books surveying a wide range of cryptids rather than concentrating upon certain specific types).

The Related Sciences section, spanning pp. 124-220, contains reviews of books that, although not devoted wholly to cryptozoology, often include some crypto-content and/or deal with mainstream zoological subjects of considerable background relevance to mystery beasts. It is divided into three subsections, whose respective titles readily reveal the subject matter of the books reviewed within them. Namely: Paleontology and Evolution; Environment and Exploration; and Zoology of Land, Sea, and Air.

Crypto-Fiction, spanning pp. 221-254, is a less serious, fun section in which Bille presents one subsection devoted entirely to his personal Top Three favourite cryptozoologically-themed novels, and a second subsection containing reviews of a wide range and sizeable number of other crypto-novels. Some of these are classic works, others are less familiar, and there are a few that were entirely new to me but which I fully intend to acquaint myself with at some point.

Last but by no means least of the four sections is A Marvelous Miscellany, spanning pp. 255-272, which definitely lives up to its title, containing reviews of books devoted to the far fringes of cryptozoology and beyond, including beasts of mythology and folklore, ostensibly supernatural and paranormal entities, speculative future evolution of wildlife, and some wholly unclassifiable but no less fascinating subjects.

In two afterwords, respectively entitled Cryptids and Me and A Few Contributions of My Own, spanning pp. 272-279, Bille offers some brief thoughts regarding certain cryptids that in his view may indeed exist, and documents his previous cryptozoological publications. The remainder of the book consists of an acknowlegements section and an extensive index (which also incorporates a bibliography).

Throughout this book, the reviews by Bille vary considerably in length, but they are always balanced, informative, and informed. Moreover, whereas he is not afraid to highlight areas or coverage that he does not personally agree with, he is never rude or hostile in his treatment of them (unlike the belligerent, dogmatic attitude of certain other figures who have inputted within this field of study at one time or another down through the decades). Indeed, Bille's objective take is what makes his reviews so interesting and entertaining, because one is never struggling to discover the real book obscured behind an opaque veil of prejudice and bias, which is a most welcome, heartening change from so many reviews of cryptozoological works that I've read - or endured – over the years.

Equally, it is evident from the content of his reviews that Bille has actually read all of the books in question (in turn reliably demonstrating just how prolific a reader of cryptozoological writings he is, and therefore an ideal person to prepare a work like this one). That may seem a strange statement to make, but as an author myself I am only too aware – painfully so, on occasion – that in all too many instances, a so-called reviewer either has never actually read the book in question or has merely paraphrased the blurb on its back cover or front flyleaf!

Over 20 years ago, I prepared my bibliography of cryptozoology books (which includes not only their titles and authors but also their publishers, places of publication, and dates of publication) in order to provide newcomers and longstanding crypto-researchers alike with a comprehensive listing of published books on the subject – a subject whose literature until then had never been presented in such a readily accessible manner, enabling would-be readers of such books to discover instantly what was out there and containing sufficient supplementary information to assist them in tracking down such works.

Now, with Of Books and Beasts, Bille has ably augmented my efforts by providing an excellent companion work, a veritable pocket library, in fact, that provides very useful, fair-minded synopses and personal opinions concerning around 500 such books, and which will I feel be of immense value to the same audience of readers as my list is aimed at. There is nothing else like this book out there, so I am very happy that it also happens to be a very worthy contribution in its own right to the cryptozoological literature – one that I spent much of the day dipping into after its review copy arrived in the post, because it was simply far too engrossing to put down once opened! So I heartily and unhesitatingly recommend it to anyone eager to learn about the vast diversity of books nowadays out there that deal with mystery beasts.

Finally: or as Lieutenant Columbo would say at this point in the proceedings, just one more thing… (ok, two, in this particular instance – a couple of minor quibbles). Firstly: I'm somewhat bemused by Bille's arranging of his book reviews within each subsection or section. For the most part, it seems to be chronological (although see a little later in my present review), from earliest to most recent publication date, but this is not entirely adhered to. For instance: in the Others subsection of Section 1 (Cryptozoology Books), the first book to be reviewed is Maurice Burton's Animal Legends, published in 1957, which is followed in strict chronological order by a further 34 titles (I'm counting the four Quammen books as a single entry as this was how Bille reviewed them), the last of which is Kelly Milner Halls's 2019 book Cryptid Creatures: A Field Guide. But then, for no apparent reason, the next book reviewed in this same subsection is Michael Newton's 2007 book Florida's Unexpected Wildlife, after which another ten reviewed books follow, arranged chronologically from 2007 to 2020. Why were these not incorporated into the previous 35-book chronological listing, instead of being separated into their own 11-book chronological listing directly following it?

No reason is given, so I am wondering if these final eleven were last-minute reviews by Bille, possibly written to fill some perceived gaps in his coverage but submitted too late to be worked into the main body of reviews? If so, a very short note explaining this inconsistent ordering of reviews would have been most useful (even just a two-word subtitle – Stop Press, or Late Additions – would have sufficed). Moreover, for reasons again unexplained, in the Other Crypto-Novels subsection of the Crypto-Fiction section, and also throughout the section A Marvelous Menagerie, the books reviewed are not arranged chronologically at all, but are instead arranged alphabetically, by author surname. Why not stay with a chronological ordering? Strange.

Secondly: by its very nature, the content of this book is a personal, subjective one, inevitably guided by Bille's own particular interests and influences. In other words, no two compilers of such a book would have included the same entries, and divided them up into sections of the same proportions or subjects. Having said that, I do feel that more space should have been devoted to cryptozoology books per se, and less to (in particular) the Related Sciences section. This book's unique aspect, and no doubt its greatest single selling point, is that it is the first one to proffer an extensive series of reviews of cryptozoology books, so in my view the Related Sciences section could have been greatly reduced, with no serious loss to the book's worth, and replaced by far more cryptozoology-themed book reviews. As it is, I can think of a fair number of crypto-books for which one might expect to find reviews included here, but which are not represented. For instance, although there are a few reviews of books devoted to certain specific types or geographical groupings of feline cryptids, neither edition of the most comprehensive book ever published on such creatures globally is represented by a review, which is clearly a major omission. I may be wrong, but wasn't the book in question entitled Mystery Cats of the World…?

"Looking for a concise but reliable survey of the most noteworthy cryptozoological books past and present? Look no further - here it is!"

Dr Karl Shuker, quoted on the back cover to Of Books and Beasts.

February 25, 2022

A BLACKER SHADE OF DARK - THE GENETIC EXPLANATION FOR PSEUDO-MELANISTIC TIGERS, REVEALED AT LAST!

Exquisite painting of a pseudo-melanistic tiger, prepared specifically for my writings by acclaimed animal artist and longstanding friend Bill Rebsamen – thanks Bill! (© William M. Rebsamen)

Exquisite painting of a pseudo-melanistic tiger, prepared specifically for my writings by acclaimed animal artist and longstanding friend Bill Rebsamen – thanks Bill! (© William M. Rebsamen) True melanism is when an animal's background colour is abnormally dark (due to the expression of a mutant gene allele), so much so that any surface patterns or markings are hidden by it, as with the rosettes of a black leopard, for example.

Despite many eyewitness reports and anecdotal accounts on file, however, no melanistic or black tiger has ever been scientifically confirmed, and this exotic cat form thus remains a cryptid – claimed to exist by locals but not verified by science (for more details on ShukerNature regarding melanistic aka black tigers, click here).

Yet in recent years, following largely unconfirmed sightings dating back half a century, media reports have documented several living specimens in eastern India's Similipal Nature Reserve of what they refer to as black tigers. Photographs of these supposed black tigers, however, swiftly confirm that they are not melanistic specimens. Instead, they represent an equally intriguing but reverse phenomenon, known correctly as pseudo-melanism.

This is characterised by the animals' background colour being normal but their surface markings being abnormally abundant and broad, and having fused together to yield an almost unbroken, solid black mass of dark pigmentation, especially dorsally and upon the tigers' flanks, that has largely obscured the background colouration.

Skin of a reverse-coated pseudo-melanistic tiger from Similipal, India (© Dr Lala A.K. Singh)

Skin of a reverse-coated pseudo-melanistic tiger from Similipal, India (© Dr Lala A.K. Singh)

Until very recently, the genetic basis of pseudo-melanism in tigers has remained unknown. In September 2021, however, a newly-published study in the journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences) conducted by a team of researchers from the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bangalore revealed that this condition was the result of a rare mutation in one gene, Transmembrane Aminopeptidase Q (or Taqpep, for short).

Recessively inherited variants of this gene are also responsible for the markings in domestic cats, and in the ornately striped king mutant form of the normally spotted cheetah.

Moreover, whereas it has been estimated that up to 37% of all tigers in the Similipal Nature Reserve are pseudo-melanistic, there do not appear to be any such specimens anywhere else in India. The researchers believe this unusual situation to be due to a combination of a small founder population at Similipal, its isolation from other tiger populations, and inbreeding within the Similipal tiger population. Also, these tigers' darker colouration may be giving them a selective advantage when hunting in the shadowy forests of Similipal.

For further information on ShukerNature concerning pseudo-melanistic tigers, click here; and for feline pseudo-melanism in general, click here. See also this fascinating subject's coverage in my trilogy of cryptozoological cat books – namely, Mystery Cats of the World, Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery, and Mystery Cats of the World Revisited.

My trilogy of cryptozoological cat books (© Dr Karl Shuker & Robert Hale Ltd/CFZ Press/Anomalist Books respectively)

My trilogy of cryptozoological cat books (© Dr Karl Shuker & Robert Hale Ltd/CFZ Press/Anomalist Books respectively)

Karl Shuker's Blog

- Karl Shuker's profile

- 45 followers