Karl Shuker's Blog, page 10

August 17, 2021

THE PEEL STREET MONSTER - LOOKING BACK AT A LOCAL CRYPTID

Vintage illustration of a coati (public domain)

Vintage illustration of a coati (public domain)

It's always good to stumble upon the history of a mystery beast not previously documented in the cryptozoological literature (which it hadn’t been, prior to my doing so in a Fortean Timesarticle and subsequently in my book Extraordinary Animals Revisited), and especially when it happens to be a local one – having occurred just a few miles away from where I was born and still live. Yet although the case of the Peel Street Monster began in high drama, the outcome was distinctly underwhelming.

During winter 1933-34, rumours began circulating within the area of Brickkiln Street and Peel Street in the large urban West Midlands town (now city) of Wolverhampton, England, of a bizarre creature that was attacking children. One bold lad who tried to pursue this beast, which became known as the Peel Street Monster, presumably angered it, because it allegedly leapt at his throat, attempting to bite him.

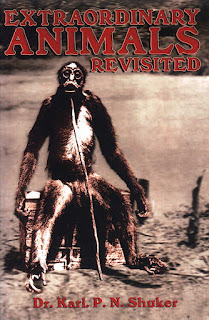

Extraordinary Animals Revisited

(© Dr Karl Shuker/CFZ Press)

Extraordinary Animals Revisited

(© Dr Karl Shuker/CFZ Press)

There came a day in January 1934, however, when this vicious creature made one onslaught too many. A crowd of boys and youths, who included among their number a 17-year-old called Georgie Goodhead, were playing on the corner of St Mark's Street and Raglan Street, when another boy, Jackie Franklin, raced out of Peel Street and up towards them in a state of great alarm. Shouting for help, he told them that a youngster called Billy Wright (but not the famous future Wolverhampton Wanderers footballer of that same name, at least as far as I'm aware) was being attacked by the monster on some waste ground. Georgie and his mates raced back to Peel Street at once with Jackie, where they observed a peculiar-looking animal threatening a small boy. In a later Wolverhampton Express and Star newspaper report, Georgie recalled:

I went and saw a queer animal, far too big for a rat, leaping towards a child about five-year[s]-old. I shouted and the thing turned on me. It crouched, its eyes bulging, then it leaped like lightning.

According to the newspaper report, as the creature neared his throat Georgie picked up a brick and hit it with this hefty implement as hard as he could. The animal collapsed, falling into a pool of water, and was swiftly kicked to death by the crowd that had gathered to watch the boys confronting it. Happily, little Billy was unhurt, and was taken by some of the boys to his parents' sweetshop in Peel Street, while Georgie and Jackie gave a statement at the Red Lion police station and received half a crown each for their bravery.

As for the Peel Street Monster: apart from noting that it was a male, no-one had any idea what this mystifying beast was. According to media reports, naturalists, taxidermists, and vets were all called in to identify it, but to no avail. One unnamed 'expert' did suggest that it may be an anteater – in Wolverhampton?? Another one considered it possible that the creature (despite being dead!) might become a serious rival to the Loch Ness monster.

A ring-tailed coati Nasua nasua, the most familiar of the four recognised coati species and native to South America (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A ring-tailed coati Nasua nasua, the most familiar of the four recognised coati species and native to South America (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Events took an even more surprising turn the following day, when a second mystery beast was found in the Brickkiln region. This one, a female, was already dead, but it closely resembled the Peel Street Monster. Moreover, a photograph of it published in the Express and Star helped to identify its species.

It was a South American coati (coatimundi) – a long-tailed relative of the raccoon and belonging to the genus Nasua, with a head-and-body length of up to 2 ft, a thin tail of much the same length, and distinguished by its very elongate snout (responsible for the 'anteater' identity proffered for the Peel Street Monster?). But where had it, and the Peel Street specimen, come from? And if there had been a pair on the loose, could there be more?

The prospect of a plague of coatis terrorising the good residents of Wolverhampton may seem decidedly slim (not least because the favoured diet of coatis consists of invertebrates and small lizards – as opposed to small children!). Nevertheless, the council was clearly taking no chances, for as the Express and Star duly reported:

And fresh fears arose in Wolverhampton as rumours spread that there may be a colony of the creatures hiding in partly closed cellars. Hundreds of people gathered in Salop Street to watch council workers trying to ascertain if a colony of the creatures were hiding there. The crowds were so great they hampered the efforts of the official rat-catcher. In the search, weapons brought in to confront any coatimundis found included poison gas, traps, sulphur, terriers and ferrets. It was uncertain whether the ferrets were to be used following a suggestion that they might form part of the coatimundi diet [I don't think so!].

As ably demonstrated by this white-snouted coati Nasua narica: when walking quadrupedally, coatis are famous for often holding their tails vertically upright with a little curl at the tip, giving them an unexpected superficial resemblance to small furry sauropod dinosaurs! (© Dennis Jarvis/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

As ably demonstrated by this white-snouted coati Nasua narica: when walking quadrupedally, coatis are famous for often holding their tails vertically upright with a little curl at the tip, giving them an unexpected superficial resemblance to small furry sauropod dinosaurs! (© Dennis Jarvis/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Ferrets or no ferrets, the search did not find any other errant coatis. Police investigations did reputedly reveal that the female coati had been in a travelling menagerie that had parked here earlier (circuses and fairs would sometimes set up on this slum-area waste ground at that time), and had discarded the creature's body after it had died. However, the Peel Street Monster's origin remains a mystery to this day – as do various other aspects of this curious case.

Can we even be sure that the Peel Street Monster was a coati? For if the accounts of it are true, it must have been an exceptionally belligerent specimen. The Express and Star published a photo of this creature lying dead with a crowd of onlookers surrounding it, but its form cannot be discerned. And what happened to the two carcases? Some correspondences reminiscing about this incident appeared 50 years later in the Express and Star during March 1994, but conflicting recollections only served to muddy these already murky waters even further.

All in all, after also allowing for the likelihood of embellished descriptions with such an odd episode, the only thing that can be said with certainty regarding the Peel Street Monster is that something unexpected was seen and killed in Wolverhampton – a most unsatisfactory end to one of the most intriguing OOP animal cases on file from the West Midlands. True, coatis (unlike anteaters!) are nowadays often kept as exotic pets – a friend of mine at university owned one, and I also well remember about 10 years ago seeing one with a collar and lead being taken for a walk by its owner through another local Midlands town, duly attracting considerable interest and attention from passers-by, including me – but whether an escaped/released pet coati explains the Peel Street Monster is another matter entirely.

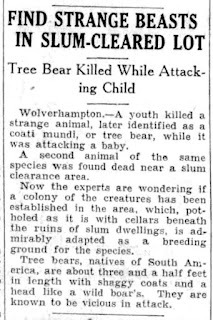

Finally: I was recently reminded of this curious case when Canadian Facebook friend Kevin Stewart kindly sent to me a scan of a Canadian newspaper cutting documenting it, which was particularly interesting to me as I was previously unaware that this relatively obscure, ostensibly local-interest-only UK story had ever attracted any overseas media coverage. The cutting was from Alberta's Edmonton Bulletin for 17 February 1934, so for the purposes of historical documentation, here it is – thanks Kevin!

Edmonton Bulletin

newspaper report of 17 February 1934 concerning the Peel Street Monster public domain)

Edmonton Bulletin

newspaper report of 17 February 1934 concerning the Peel Street Monster public domain)

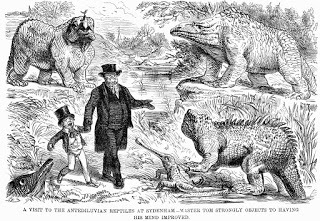

July 28, 2021

DENYING A DEINOTHERE - WHEN THE CAMERA DOES LIE!

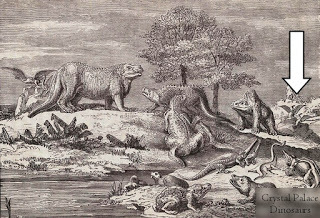

The fake deinothere photograph that inspired this ShukerNature blog article (© owner/photo manipulator unknown to me – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

The fake deinothere photograph that inspired this ShukerNature blog article (© owner/photo manipulator unknown to me – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only) Thanks to the sophistication of readily-available digital photo-manipulation programs, photographic evidence for the existence of cryptids is of very little worth nowadays, at least in my opinion. This was readily demonstrated in mid-February 2021, following the widespread circulation online of a close-up, excellent-quality b/w photograph seemingly depicting the presence in some unidentified zoological gardens of a living deinothere.

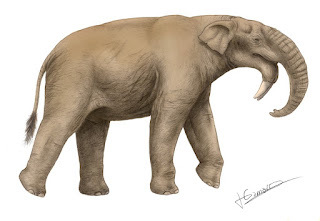

Renowned for their huge body size and especially for their diagnostic downward-curving lower jaw and lower tusks but absence of upper tusks, deinotheres were prehistoric pachyderms distantly related to today's elephants. However, even the most recent fossils of these mega-mammals date back 1 million years.

Clearly, therefore, the existence of a specimen alive and well in any zoo would, if genuine, be a scientific sensation. Yet as the scientific world has made no mention whatsoever of any such prehistoric survivor thriving in captivity, the photo is evidently a fake.

Reconstruction of the likely appearance of a deinothere in life (© Concavenator/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Reconstruction of the likely appearance of a deinothere in life (© Concavenator/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Over the years, I have made a point of exposing many fake photos of the cryptozoological kind, as revealed in many ShukerNature blog articles, in the hope of ensuring that, by doing so, these hoax images can no longer mislead anyone. The most effective means of accomplishing this feat is to uncover the original, genuine photo that the hoaxer has photo-manipulated to yield the fake version, which I have successfully achieved on numerous occasions by conducting detailed image searches online. So when the deinothere picture was brought to my attention, I duly began one such search, but on this particular occasion a fellow cryptozoological researcher beat me to it.

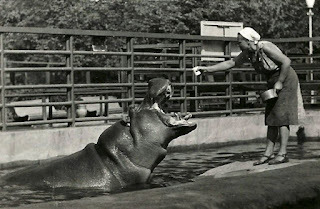

German cryptozoologist and longstanding friend Markus Hemmler had seen the deinothere photo before I had done and had begun an online image search of his own for the original genuine picture straight away. Moreover, he soon met with success, discovering that the original image was a vintage photograph that actually depicted a hippopotamus living in what was then Leningrad Zoo in the USSR.

As he informed me on 14 February, Markus had found it in a Czech article from 4 March 2017, documenting the hardships that the zoo and its animals had suffered during World War 2 (click hereto access this article). A reconstruction of what a deinothere may have looked like in life had been deftly superimposed over the hippo by some unknown hoaxer, hiding it completely. Case closed.

The vintage photograph of a hippopotamus living at Leningrad Zoo during WW2 that had been digitally manipulated by person(s) unknown to create the fake deinothere photograph (public domain)

The vintage photograph of a hippopotamus living at Leningrad Zoo during WW2 that had been digitally manipulated by person(s) unknown to create the fake deinothere photograph (public domain)

July 26, 2021

A SURVEY OF EXTINCT DOG BREEDS. PART 1: GUN DOGS THAT ARE GONE, AND HOUNDS THAT NO LONGER ABOUND

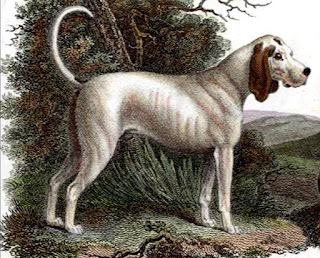

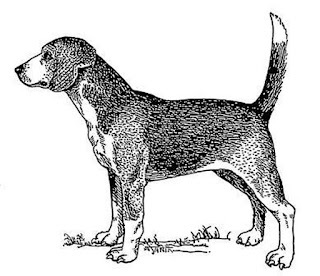

Vintage illustration of a talbot hound, now extinct (public domain)

Vintage illustration of a talbot hound, now extinct (public domain)

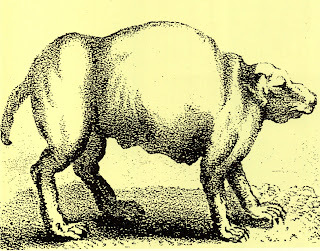

Previously on ShukerNature, I documented the little-known history of a truly remarkable creature – Mexico's hump-backed izcuintlipotzotli, a truly bizarre-looking breed of domestic dog that for still-undetermined reasons is now extinct (click hereto access my article). Needless to say, extinction among species of wild animal and even among breeds of domestic farm animal is well-documented, and is also, as it should be, a cause for much concern.

Conversely, the tragic reality that a sizeable number of domestic dog breeds have also died out, and for a variety of different reasons, has attracted far less attention or interest, even though some of these breeds were once very familiar – so much so, in fact, that in a number of cases their names still live on today even though they themselves are long gone.

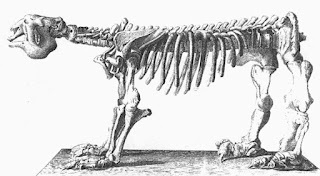

Engraving of Mexico's mysterious hump-backed izcuintlipotzotli (public domain)

Engraving of Mexico's mysterious hump-backed izcuintlipotzotli (public domain)

In an attempt to rectify this sad situation, I plan to prepare an occasional (i.e. non-consecutive) but ultimately multi-part series of ShukerNature blog articles restoring to public prominence a veritable dynasty of deceased dog breeds (and which may therefore yield the most comprehensive popular-format coverage of this neglected subject ever published when complete). I'll be surveying a very diverse array of examples, grouped in the traditional classification categories utilised by official canine organisations and shows, and accompanied by many seldom-seen but fascinating illustrations of these lost breeds.

And how better to begin this major survey than with a selection of gun dogs that are now gone and hounds that no longer abound.

POINTING OUT SOME VANISHED GUN DOGS

As will be seen throughout this article, there are a range of different reasons for the extinction of domestic dog breeds, but two of the most common ones, which arise time and again in the histories of such breeds, is that they died out either through a gradual loss of interest in perpetuating them; or, by being used in crossbreeding to yield new breeds, their own original, pure-bred form eventually disappeared. Both of these reasons certainly explain the disappearance of certain breeds of gun dog.

Morphologically and behaviourally speaking, the principal groups of gun dog are spaniels, retrievers, setters, pointers, and a somewhat looser assemblage commonly referred to as griffons. They include some extremely famous, distinctive breeds, but there were once a number of others that back in their time were no less famous or distinctive but are now extinct. Take, for example, the English water spaniel.

Painting of an English water spaniel (public domain)

Painting of an English water spaniel (public domain)

As its name implies, this breed was used for aquatic purposes, as in procuring waterfowl, and was said to be able to dive and swim as efficiently as any duck. White and tan (or liver) in colour, it resembled a curly-coated springer spaniel, as opposed to the very dissimilar Irish water spaniel, which it pre-dated. It sported long ears and legs, and is thought to have genetically influenced several modern-day breeds, such as the American water spaniel, the curly-coated retriever, and quite probably the English and the Welsh springer spaniels too. Known as far back as Shakespearian times, this once-popular breed has been extinct for almost a century, the last-known specimen being reported in the 1930s.

Another now-deceased spaniel with aquatic proclivities was the Tweed water spaniel, again used for hunting ducks and other waterfowl. A much more localised breed than the English water spaniel, however, and with a very curly but uniformly liver-brown coat like the Irish water spaniel, it was only known from the Tweed area of northernmost England, close to the Scottish borders. It seemingly owed its demise to being used extensively in the development of the curly-coated and the golden retrievers as new, distinct breeds, and had vanished as a breed in its own right by the end of the 1800s.

Vintage illustration of a Tweed water spaniel (public domain)

Vintage illustration of a Tweed water spaniel (public domain)

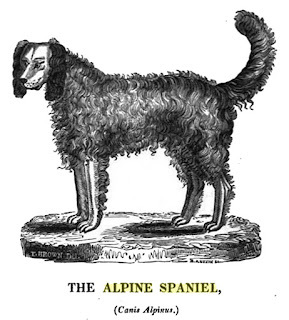

A third curly-coated spaniel was the alpine spaniel, a notably large breed native to the Swiss Alps, where the local monasteries' Augustinian canons utilised it for mountain rescues of lost or injured travellers, especially near the Great St Bernard Pass, and it was the predecessor of the modern-day St Bernard dog, as well as the clumber spaniel. Due to the adverse environmental conditions habitually faced by its breed, however, coupled with an outbreak of disease, by 1847 the last known alpine spaniel specimen had died, and upon whose death the entire breed, therefore, was also dead.

Other extinct breeds of spaniel include the Spanish and Italian spaniels (the former large with dark brown/black and white fur, the latter smaller with chestnut/liver and white fur); the Scottish spaniel (white with red flecks, once bred at Rossmore Castle, Ireland, but not seen since 1908); and the Norfolk spaniel.

An engraving by Thomas Bewick of an alpine spaniel (public domain)

An engraving by Thomas Bewick of an alpine spaniel (public domain)

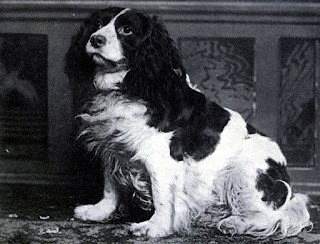

Also known as the Shropshire spaniel the Norfolk spaniel owed its more familiar name to a now-disproved theory that it had originally been developed and bred by the Dukes of Norfolk. Moreover, there is still much controversy as to whether it truly constituted a distinct breed, because it varied greatly in appearance, although 'typical' examples tended to resemble large English cocker spaniels, with black and white or liver and white coats. In 1903, the Norfolk spaniel officially ceased to exist when the English Kennel Cub formally incorporated its breed into that of the newly-defined English springer spaniel.

Another lost breed of gun dog is the pyrame, which resembled a fairly small black-and-tan cocker spaniel with short hair. Its limbs and squat muzzle were predominantly reddish-chestnut in colour, as was a pair of small spots above its eyes, but its back, haunches, head, and ears were black, the latter being very large and pendulous. Its head was small and rounded, and its tail was turned up at the back. It was used in England as a gun dog in the same way as other land-based spaniels, but it died out more than a century ago.

Dash II – rare photograph of a living Norfolk spaniel (public domain); plus a charming vintage painting of a Norfolk spaniel (public domain)

Dash II – rare photograph of a living Norfolk spaniel (public domain); plus a charming vintage painting of a Norfolk spaniel (public domain)

Also worthy of note here are two separate but both now-bygone breeds of water dog. Indigenous to Newfoundland, named after the latter territory's capital city, and with its origins dating back to the 1500s, the St John's water dog was technically a landrace rather than a strict breed. That is, it was bred to fulfil a specific purpose rather than exhibiting a standard, well-defined morphological form or pedigree.

Having said that, many specimens were retriever-like and shared a medium-sized, sturdy, black-furred appearance, often characterised with white, tuxedo-reminiscent chest markings. It was used in its native homeland to retrieve the nets of sailors, hauling them back onto the boats. Surviving until as recently as the 1980s, the St John's water dog helped to give rise to all of the major modern-day breeds of retriever, as well as to the Newfoundland itself, a burly working dog.

Three photographs of St John's water dogs (all public domain)

Three photographs of St John's water dogs (all public domain)

The Moscow water dog was a short-lived Soviet breed originally developed during the post-WW2 1940s in what is now Belarus from the Newfoundland and various European shepherd dogs. Never officially recognised by major kennel clubs outside what was then the USSR, it was one of several new breeds produced solely by the USSR's state-run Red Star Kennels, in order to provide its armed forces with working dogs (in the more general, non-show-specific sense of this term).

The desired purpose of the Moscow water dog was to rescue drowning sailors, but unfortunately it preferred to bite them rather than retrieve them, so its production was discontinued. By the 1980s, moreover, it had been officially homogenised with the Newfoundland as a single breed, and was thus categorised as extinct as far as its constituting a separate breed was concerned.

Two photographs of Moscow water dogs (both public domain)

Two photographs of Moscow water dogs (both public domain)

France's diverse array of pointer breeds, known collectively as braques, are all descended from the original braque. This was a large, sleek-furred breed reminiscent of the English pointer in shape, and whose white coat was handsomely speckled with patches or flecks of liver/chestnut.

Its ancestry dates back many centuries, but even as long ago as the 15thCentury it was already being used to create what became various of the modern-day braque breeds still existing today. Of these, some authorities claim that the braque de l'Ariège or Ariège pointer is the closest in form to the ancestral braque.

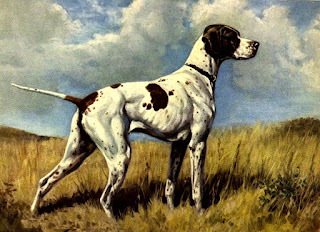

Beautiful painting of a braque du Puy (public domain)

Beautiful painting of a braque du Puy (public domain)

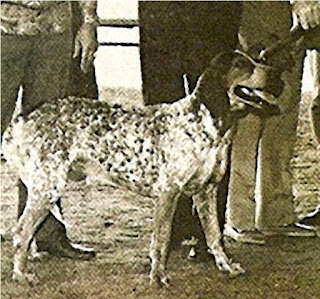

Sadly, one of the modern-day braque breeds is itself now extinct, the braque du Puy or Dupuy pointer. Created in Poitou during the 1800s for hunting in the lowlands, it sported the ancestral braque's coat colour and markings, but was also very greyhound-like by virtue of its lithe, gracile build.

Reconstituted specimens, resembling Dupuy pointers outwardly, are occasionally produced today. However, they do not correspond to the latter breed genetically.

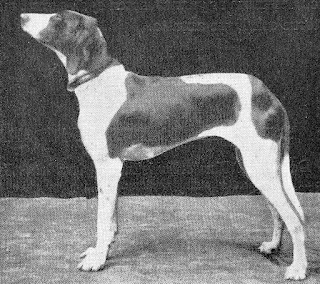

A living braque du Puy photographed in 1932 (public domain)

A living braque du Puy photographed in 1932 (public domain)

HUNTING DOWN SOME ERSTWHILE HOUNDS

Hounds include among their number some of the earliest recorded breeds of domestic dog, dating back thousands of years, such as the saluki, sloughi, and Afghan hound. Conversely, in much more recent historical times several notable breeds of hound have become extinct.

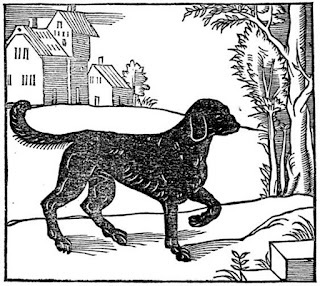

Two of the best known of these are undoubtedly the St Hubert hound and the talbot hound. Although by no means of uniform appearance (Charles IX of France actually preferred pure-white specimens), the most familiar, popular representation of the St Hubert hound is that of an all-black or black-and-tan mastiff-like breed, extremely powerful in stature and heavy-boned, with a long body but quite short legs and a very well-developed sense of smell. According to tradition, it originated in the Ardennes, Belgium, in c.1000 AD, bred by the monks at the Saint-Hubert monastery, but some have suggested that it may have arisen in France.

Early engraving of an original St Hubert hound (public domain)

Early engraving of an original St Hubert hound (public domain)

Several modern-day breeds owe their origin to the St Hubert hound, most famously the bloodhound, which is itself sometimes even dubbed the St Hubert hound. Tragically, due to having been interbred with several other breeds to yield new ones, by the early 19th Century there were scarcely any pure-bred St Hubert hounds remaining, and by the end of that same century the true, original strain had gone.

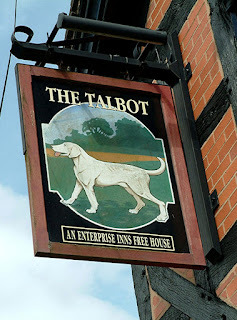

No less renowned in its time was the talbot hound, famed for its pure-white coat and dropped ears, and still frequently commemorated even today not only in many British heraldic devices but also in numerous public house or inn names and advertising signs throughout Great Britain. It was referred to in English literature at least as far back as the mid-1500s, and some authorities consider that it actually owed its origin to the afore-mentioned white specimens of St Hubert hound that were sometimes bred and maintained by French monarchs.

A talbot hound depicted on The Talbot pub sign, Worcester Road, Hartlebury, in Worcestershire, England (© PL Chadwick/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

A talbot hound depicted on The Talbot pub sign, Worcester Road, Hartlebury, in Worcestershire, England (© PL Chadwick/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

By the end of the 18th Century, however, the talbot hound had ceased to exist as a delineated breed, as did two other related forms, the northern hound (aka the North Country beagle) and the southern hound, both of which were very beagle-like in appearance and had been utilised with the talbot hound in the creation of the modern beagle breed now existing today. The talbot hound is also believed to have participated alongside the St Hubert hound in the bloodhound's development.

Due to the extensive crossbreeding that has occurred down through the centuries between France's varied native hounds, several early original breeds have become extinct. The St Hubert hound is one, and the Vendéen hound is another - a very sizeable, rough-coated, pendant-eared, reddish-brown dog used for boar hunting. However, some intimations of it are preserved in the slightly smaller but still-surviving grand griffon vendéen, which itself originated as far back as the 16th Century, the first and largest breed of griffon vendéen to be established.

Vintage illustrations of the northern hound (top) and the southern hound (bottom) (both public domain)

Vintage illustrations of the northern hound (top) and the southern hound (bottom) (both public domain)

Another former French breed of hound was the chien-gris de Saint-Louis or St Louis grey dog, which originated in France during medieval times, certainly being known as far back as the 13th Century when royal packs of hunting hound were composed almost exclusively of this breed. Serving like the St Hubert hound as a potent scenthound, it earned its name from its predominantly grey coat colour (although its long limbs and forequarters were tan or red), and from the canonised French king Louis IX's especial interest in it. It was rough-coated like the Vendéen hound, and gave rise to some of France's modern-day griffon breeds, particularly the griffon nivernais.

In addition to this quartet of famous breeds, several less familiar but no less noteworthy hounds have also disappeared. One very sad loss, for instance, is the long-haired whippet. Very similar to the typical smooth-coated whippet in general build and shape, it was instantly differentiated by way of its fairly long, harsh, wiry coat. However, this very distinctive-looking hound was bred out of existence in favour of its smooth-coated counterpart by about the end of the 19th Century. Today, some whippets sporting a long silky coat exist, but these are very different from their extinct wiry-haired predecessor.

Two very handsome examples of the chien-gris de Saint-Louis or St Louis grey dog (public domain)

Two very handsome examples of the chien-gris de Saint-Louis or St Louis grey dog (public domain)

Equally intriguing was the pocket beagle, which, as its name suggests, was a miniature version of the normal beagle, standing no taller than 13.5 inches. A pack of pocket beagles was owned by England's Queen Elizabeth I, and they were carried to the hunt on horseback. Three centuries later, Queen Victoria also owned a pack, consisting of nine couples, and only averaging 9-10 inches high; in 1844, these were depicted by artist William Barraud in a famous painting (reproduced below).

More recently, attempts have been made in North America to recreate this diminutive hound, which was traditionally used to hunt hares and rabbits, and the American Kennel Club does officially recognise beagles standing less than 13 inches high as a category separate from those that are taller (13-15 in). The English Kennel Club, conversely, does not make any such differentiation.

Queen Victoria's Master of the Beagles Mr Maynard and her pack of pocket beagles, painted by William Barraud in 1844 (public domain)

Queen Victoria's Master of the Beagles Mr Maynard and her pack of pocket beagles, painted by William Barraud in 1844 (public domain)

Another very distinctive breed was the Brazilian tracker or rastreador brasileiro, a highly efficient scenthound. Generally similar in shape, size, and form to the North American coonhound from which it was partly descended, it received official recognition as a distinct breed in 1967, from France's Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI), but less than a decade later it had vanished, and was formally declared extinct in 1973 by both the FCI and the Brazilian Kennel Club.

Its swift demise had resulted from an outbreak of disease coupled by the inimical effects of an insecticide overdose. Attempts are currently underway to recreate the Brazilian tracker in its South American homeland by a canine club called the Grupo de Apoio ao Resgate do Rastreador Brasileiro.

Two rare photographs of living Brazilian trackers (both public domain)

Two rare photographs of living Brazilian trackers (both public domain) Even more imposing was the American panther dog, bred specifically by Aaron Hall in Pennsylvania, USA, during the mid-19th Century to hunt pumas (also known in North America as panthers, cougars, and mountain lions). Part bloodhound, part bulldog, part mastiff, and part Newfoundland, they were so large that, once when visiting Hall at his hunting cabin, former State Game Commissioner C.K. Sober was actually able to ride on the back of one of them!

They were trained to hunt in pairs, and when a puma was cornered the pair would hold it down on both sides until the hunter arrived to dispatch it with his rifle. Following Hall's death in 1892, however, no effort was made by anyone to perpetuate this unique if formidable breed, so the panther dog swiftly died out.

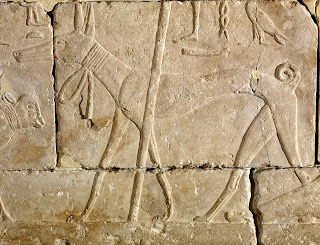

An Egyptian Old Kingdom fragment depicting a tesem (public domain)

An Egyptian Old Kingdom fragment depicting a tesem (public domain)

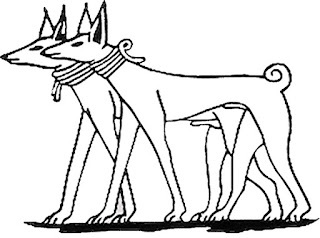

As far as its date of origin is concerned, the final extinct dog breed to be reported here is also the earliest breed – namely, the Egyptian tesem. In its loosest sense, 'tesem' was used in ancient Egypt to denote any type of hunting dog, but in its stricter, more precise sense it was employed as the name for a particular breed of sight hound or gazehound that resembled a greyhound due to its long limbs and slender body, but sported a tail that curled over its back like that of a spitz, plus slim, pointed, pricked-up ears.

One of the first, and most famous, examples on record of a tesem sensu strictowas Akbaru, the so-called Khufu Dog, which was depicted on the tomb of King Khufu (reigned 2609-2584 BC) from ancient Egypt's Old Kingdom period (c.2686-2181 BC), and was wearing a collar. Other depictions of the tesem appeared during the Middle Kingdom (c.2050–1710 BC), but it had been replaced by depictions of a saluki-like breed with pendant ears and straight tail by the time of the New Kingdom (c.1550–1077 BC).

Early Egyptian depiction of two tesems, as confirmed by their curled tails (public domain)

Early Egyptian depiction of two tesems, as confirmed by their curled tails (public domain)

In Part 2 of this occasional ShukerNature series of articles on extinct dog breeds, I plan to review a selection of examples from the Toy and Terrier categories. These were often small breeds, but were once much-loved comforter and companion dogs.

Yet for all manner of different reasons, they gradually diminished in both popularity and number until eventually they ceased to exist, except for their likenesses, captured forever like faint canine ghosts within the rare vintage photographs and other images of them that still survive, several of which I'll be showcasing in my article – so be sure to check it out when uploaded here on ShukerNature!

A rare colour photograph of a St John's water dog with an Outport fisherman in La Poile, Newfoundland, October 1971 (public domain)

A rare colour photograph of a St John's water dog with an Outport fisherman in La Poile, Newfoundland, October 1971 (public domain)

July 24, 2021

KOCH'S MONSTROUS MISSOURIUM AND HORRID HYDRARCHOS - A PHENOMENAL PAIR OF FOSSILISED FRAUDS. Part 2: HYDRARCHOS, THE FAKE SEA SERPENT THAT MADE A SILLY MAN OUT OF SILLIMAN

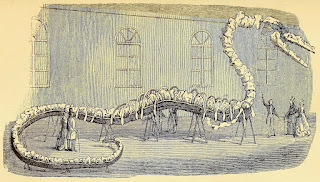

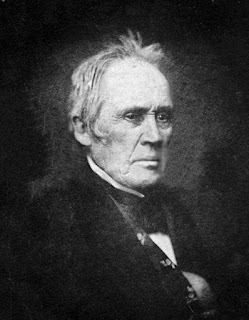

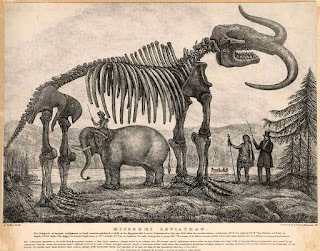

Albert C. Koch's Hydrarchos (aka Hydrargos) – a classic engraving from a German journal, 1846, colourised (public domain)

Albert C. Koch's Hydrarchos (aka Hydrargos) – a classic engraving from a German journal, 1846, colourised (public domain) As recently revealed in Part 1 of this 2-part ShukerNature blog article (click hereto access it), the self-styled 'Dr' Albert C. Koch (in reality, he did not possess a doctorate) was one of many 19th-Century Phineas T. Barnum emulators at large in the USA, establishing dime museums filled with a riotous assemblage of factual and phoney specimens from the living and non-living worlds, and, if sufficiently successful, organising nationwide and sometimes even international tours displaying their most famous and fantastic exhibits. In the case of Koch, who was not merely an entrepreneur of this dubious variety but also a passionate amateur palaeontologist and fossil collector, after opening during 1836 one such museum in St Louis, Missouri, he successfully excavated a mastodon skeleton in Missouri's Benton County four years later, but that was far from all.

Once Koch had not only assembled this skeleton but also surreptitiously made it much bigger than it actually was by adding extra vertebrae and other bones to it from additional mastodon remains, he dubbed his monstrous multi-mastodon the Missourium, and audaciously claimed that it was nothing less than the fossilised remains of the biblical reptilian sea monster Leviathan. Moreover, after making this phoney mega-beast the central exhibit at his museum for a year, Koch decided in 1841 to sell his museum and go on tour with the Missourium. This he did, but after receiving a very lucrative offer for it from the world-famous palaeontologist Prof. Sir Richard Owen of London's British Museum in 1843 (who readily recognised that the Missourium was a fraudulent composite, not a single creature, but could also see that if dismantled, a complete genuine mastodon skeleton could be reassembled from its components), he promptly sold it to Owen.

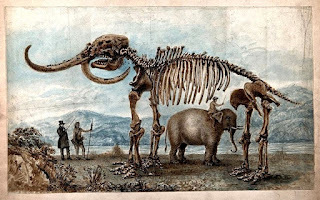

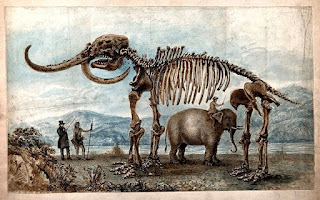

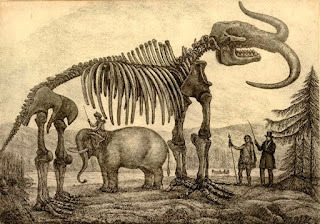

Koch's monstrous Missourium, depicted in this 19th-Century engraving towering over an Asian elephant! (public domain)

Koch's monstrous Missourium, depicted in this 19th-Century engraving towering over an Asian elephant! (public domain)

However, this meant that Koch now needed a new, equally – if not even more – spectacular exhibit to tour with and earn him further money by drawing in the crowds of visitors anxious to cast their credulous eyes upon it. So, what did he do? He created not one but two gargantuan fossil sea serpents, bigger than any fossil creature ever recorded at that time!

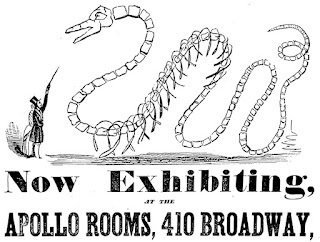

In 1845, an immense skeleton that Koch had recently unearthed in Alabama, and which he claimed to be the near-complete fossilised remains of a prehistoric reptilian sea serpent, was exhibited by him in assembled form, mounted on stilts, in the Apollo Saloon's rooms on New York City’s Broadway.

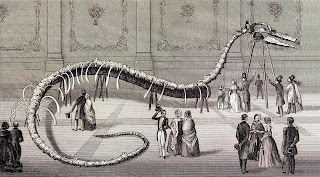

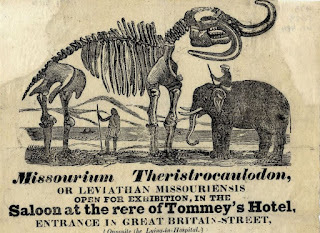

Advertisement for the very first public exhibition of Hydrarchos (public domain)

Advertisement for the very first public exhibition of Hydrarchos (public domain)

Measuring at least 114 ft long (but see Koch's own inflated claim below), it consisted of a skull (including a pair of lengthy, tooth-brimming jaws), an exceedingly long, sinuous vertebral column that featured a lengthy curved neck held upright and an even longer horizontally-curved tail, some ribs in the creature's thoracic region, and parts of supposed paddle limbs, He charged interested spectators in America 25 cents to observe his antediluvian marvel, and 1 shilling to spectators in England once he began touring overseas with it.

Despite this specimen looking totally unlike his Missourium, Koch bizarrely stated that it too was the biblical Leviathan! And according to one broadsheet advertisement for its appearance at Niblo's Garden in New York City, he also claimed that when alive it must have measured 30 ft in circumference, and weighed at least 7,500 lb (I've seen one incredible claim that it weighed an outrageous 40,000 lb!).

A second classic engraving of Hydrarchos from a German journal, 1846, colourised (public domain)

A second classic engraving of Hydrarchos from a German journal, 1846, colourised (public domain)

As with the Missourium, Koch soon prepared a short booklet fully documenting his new reptilian revelation, which was published in 1845. Like before, it sported an unnecessarily lengthy, albeit informative title: Description of the Hydrarchos Harlani (Koch): A Gigantic Fossil Reptile: Lately Discovered by the Author, in the State of Alabama, March 1845 [I've omitted the remainder of its title, which stretched to a further 32 words!]. In it, he introduced his description of the Hydrarchos with the following emphatic pronouncement and dramatic dimensions:

This relic is without exception the largest of all fossil skeletons, found either in the old or new world. Its length being upwards of one hundred and fourteen feet, without estimating any space for the cartilage between the bones, and must, when alive, have measured over one hundred and forty feet, and its circumference probably exceeded thirty feet, reminding us most strikingly, of the various statements made by persons, in regard to having seen large serpents in different parts of the ocean, which were known by the name of Sea Serpents.

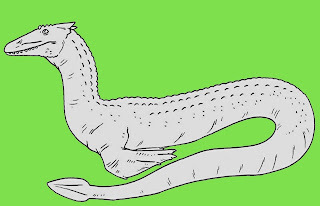

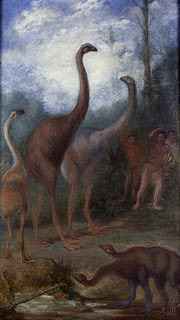

Reconstruction of Hydrarchos in life, based upon Koch's claims (© Tim Morris)

Reconstruction of Hydrarchos in life, based upon Koch's claims (© Tim Morris)

As with his Missourium booklet, Koch then went on to provide a lengthy, extremely detailed description containing all manner of unfounded conjectures and suppositions regarding the possible lifestyle and appearance in life of the Hydrarchos (such as sunbathing in rivers; possessing an extremely long neck that it held upwards in an arching curve like a swan to spy unwary prey walking upon the adjoining shore that it could then seize; and cannibalistically devouring younger specimens of its own kind). Ironically, conversely, he also included some accurate accounts of its genuine mammalian characteristics, such as its double-rooted teeth, even at times comparing it directly and favourably with cetaceans (of which Basilosauruswas of course one – see a little later here for Basilosaurus details), only for him then to dismiss them in favour of a reptilian identity for it!

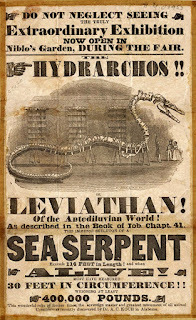

Again as with his Missourium, Koch had given this elongate entity a formal scientific name, which was originally Hydrargos sillimanii, honouring eminent Yale College (now University) naturalist Prof. Benjamin Silliman (1779-1864), who believed in the existence of sea serpents, and had written a fulsome letter of 2 September 1845 to the editors of the New York Express newspaper authenticating Koch's Hydrargos.

Prof. Benjamin Silliman (public domain)

Prof. Benjamin Silliman (public domain)

Here is what he wrote:

The Skeleton having been found entire, inclosed in limestone, evidently belonged to one individual, and there is the fullest ground for its genuineness. The animal was marine and carnivorous, and at his death was imbedded in that ancient sea where Alabama now is; having myself recently passed 400 miles down the Alabama river, and touched at many places, I have had full opportunity to observe, what many Geologists have affirmed, the marine and oceanic character of the country.

Most observers will probably be struck with the snake-like appearance of the skeleton. It differs, however, most essentially, from any existing or fossil serpent, although it may countenance the popular (and I believe well founded) impression of the existence, in our modern seas, of huge animals, to which the name of sea serpent has been attached.

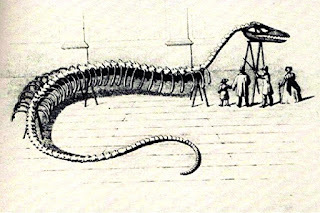

A lesser-known Hydrarchos engraving, from 1845 (public domain)

A lesser-known Hydrarchos engraving, from 1845 (public domain)

Notwithstanding Silliman's misplaced faith in its authenticity, however, the true identity – or identities – of Koch's Hydrargos ultimately came to light when one of its numerous visitors, esteemed American anatomist Prof. Jeffries Wyman (1814-1874), exposed two major problems with it.

Firstly, its teeth and bones were mammalian, not reptilian, originating from a prehistoric form of very lengthy whale known as Basilosaurus (its reptilian-sounding moniker derives from the fact that when first named by zoologist Dr Richard Harlan (1796-1843), it was mistakenly assumed by him to have been a reptile). Secondly, just like the Missourium, its spinal column was composed of vertebrae obtained from more than one individual specimen (possibly as many as six, in fact, and procured by Koch from several different Alabama locations too), thereby explaining this creature's gigantic size. Indeed, as Basilosaurusattained a total length of 'only' 70 ft or so, Koch's 114-ft Hydrargos was larger than life in every sense!

A model of Basilosaurus

(© Markus Bühler)

A model of Basilosaurus

(© Markus Bühler)

Once this became known, with the horrid Hydrargos, courtesy of Koch, having duly made a silly man out of Silliman, the latter highly-embarrassed scientist demanded that his name be removed forthwith from the binomial with which Koch had christened his bogus beast. Yet seemingly unfazed by its public unmasking as a fake, Koch simply gave his charlatan sea serpent a new binomial and continued exhibiting it on tour undeterred.

It was now known as Hydrarchos harlani, or simply the Hydrarchos colloquially, its new genus being only a slight modification of the old one, and its new species name, harlani, honouring another scientist. This time it was none other than the afore-mentioned Dr Richard Harlan, who had examined the very first known fossil vertebra of Basilosaurus and had given this archaic whale its misleadingly reptilian genus name in 1835. Moreover, being deceased by now, Harlan was in no position to challenge Koch's usage of his name when rechristening his spoof sea serpent.

Mounted Basilosaurus skeleton at Nantes Natural History Museum (© François de Dijon/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Mounted Basilosaurus skeleton at Nantes Natural History Museum (© François de Dijon/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

In 1848, English palaeontologist Dr Gideon A. Mantell (1790-1852) wrote an excoriating letter to the Illustrated London News denouncing both Koch and his lithic Leviathan, and fully explaining the latter's true nature as a composite Basilosaurus. At much the same time, however, Koch had sold it to Prussia's King Friedrich Wilhelm IV for a lifelong annual pension, so I doubt that Mantell's criticism unduly disturbed him.

In any case, once he had sold his original Hydrarchos specimen, Koch had returned to Alabama and unearthed a second Basilosaurusskeleton in February 1848. From this and other remains, he duly constructed a second Hydrarchos specimen, this one measuring 96 ft long, and then began touring in Europe all over again.

Hydrarchos advertisement flyer, 1840s (public domain)

Hydrarchos advertisement flyer, 1840s (public domain)

Meanwhile, the new, royal owner of what had previously been Koch's original Hydrarchos gave it to Johannes Müller at Berlin's Royal Anatomical Museum, who, knowing of its true nature, arranged for it to be dismantled, with its components officially relabelled as Basilosaurus remains. Some of these were subsequently sold during the 1850s t0 the Teyler Museum in Haarlem, the Netherlands, via the fossil auction house Krantz, based in Bonn, Germany (but without their origin in Koch's Hydrarchos being revealed!).

Various other remains from it were donated by Müller to Berlin's Museum für Naturkunde. However, the vast majority were long thought to have been destroyed during World War II, but according to recent ongoing investigations this may not have been the case.

Hydrarchos as portrayed in Koch's own diary (public domain)

Hydrarchos as portrayed in Koch's own diary (public domain)

As for Koch's second Hydrarchos: when he finally tired of touring, Koch sold it to the new owner of his erstwhile St Louis museum, who in turn later sold it to a similar establishment in Chicago, Illinois. This was a mini-emporium packed full of curiosities and real specimens intermingled with fake ones, which was owned by Colonel E.L. Wood and duly known as Colonel Wood's Museum.

Here the Hydrarchos was soberly labelled as a specimen of Zeuglodon (a junior synonym of Basilosaurus), rather than as any legendary Leviathan or suchlike. Tragically, however, the entire museum and its contents were destroyed during the great fire that devastated Chicago in 1871.

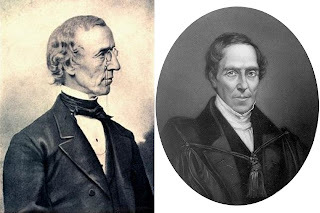

The nemeses of Hydrarchos – Prof. Jeffries Wyman (left) and Dr Gideon A. Mantell (right) (both public domain)

The nemeses of Hydrarchos – Prof. Jeffries Wyman (left) and Dr Gideon A. Mantell (right) (both public domain)

An inevitable result of his escapades with the Missourium and the two Hydrargos/Hydrarchos specimens was that Koch's name became synonymous with fraud, and by the time of his death in 1867 all claims and finds made by him were routinely dismissed as unreliable by the scientific community. This trend continued for many decades, but based upon some intriguing, corroborating finds in later years by reputable researchers, a number of scientists have reassessed Koch's claims and now believe that some of them, especially ones relating to various human artefacts allegedly found by him in association with fossil mastodons and ground sloths in North America, may have been valid after all.

Even so, it seems highly unlikely that Koch will ever be fully rehabilitated by mainstream science. Thanks to his faked fossil exhibits, he may have acquired fame and fortune, but at the same time he lost the opportunity for scientific recognition that he had always craved – and which he might well have achieved, if only he had presented his notable finds of mastodon and Basilosaurusskeletons in a straightforward, honest manner, rather than wilfully distorting and misrepresenting their nature for purely lucrative, non-scientific purposes. Instead, his name seems forever destined to be irrevocably associated with hoax and fraud.

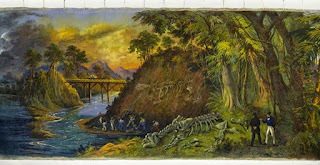

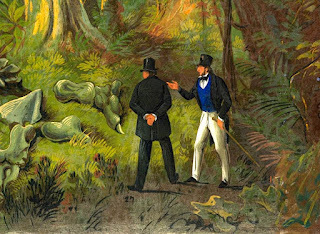

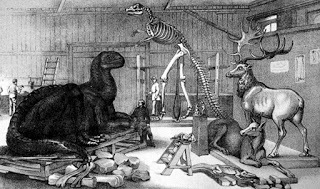

Above: The section of John J. Egan's enormous painting 'Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Plain' that contains the white-trousered figure believed by some researchers to be Albert C. Koch, shown gesticulating towards some fossilised ground sloth remains (public domain); Below: an engraving of a fossil ground sloth skeleton whose corresponding form readily confirms the taxonomic identity of the remains in Egan's painting (public domain)

Above: The section of John J. Egan's enormous painting 'Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Plain' that contains the white-trousered figure believed by some researchers to be Albert C. Koch, shown gesticulating towards some fossilised ground sloth remains (public domain); Below: an engraving of a fossil ground sloth skeleton whose corresponding form readily confirms the taxonomic identity of the remains in Egan's painting (public domain)

Finally: It is nothing if not curious that images of Albert C. Koch himself are exceedingly elusive, as I discovered when preparing this 2-part ShukerNature blog article. However, some researchers have claimed that Koch is the figure who is depicted wearing white trousers, and gesticulating towards some newly-unearthed fossil ground sloth remains (a feat that he did indeed accomplish in 1838), within one section of the enormous 348-ft-long painting 'Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Plain', which was produced by artist John J Egan in 1850.

Incidentally, some online commentators regarding this painting, and no doubt influenced by Koch's mastodon excavations, have misidentified the beast remains being gesticulated at in it as those of a mastodon. In reality, however, they are unequivocally from a ground sloth, whose skeleton is visibly very different from that of any mastodon.

Close-up of the section of Egan's painting containing the figure believed by some to be Koch (public domain)

Close-up of the section of Egan's painting containing the figure believed by some to be Koch (public domain)

July 23, 2021

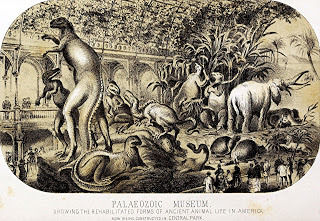

KOCH'S MONSTROUS MISSOURIUM AND HORRID HYDRARCHOS - A PHENOMENAL PAIR OF FOSSILISED FRAUDS. Part 1: MISSOURIUM, A MULTI-MASTODON!

Colour engraving of 'Dr' Albert C. Koch's Missourium (Wellcome Collections/Wikipedia – CC BY 4.0 licence

)

Colour engraving of 'Dr' Albert C. Koch's Missourium (Wellcome Collections/Wikipedia – CC BY 4.0 licence

)

Unless you're well-versed in palaeontology, fossil forgeries are less likely to have attracted your attention than fraudulent fauna composed of modern-day materials. These latter fakes include the infamous Feejee mermaids skilfully constructed from the upper portions of monkeys and the lower regions of fishes, North America's notorious jackalopes and Europe's horned hare counterparts (both types sporting deer antlers or individual tines), and the dragonesque Jenny Hanivers and monstrous devil-fishes that upon closer observation turn out to be nothing more radical than dried rays or skates with modified fins and remodelled bodies.

However, there are two very notable – and exceedingly sizeable – pseudo-reptilian exceptions to this generalisation. Moreover, both of them were created by the very same hoaxer, as will now be revealed here in this present 2-part ShukerNature blog article.

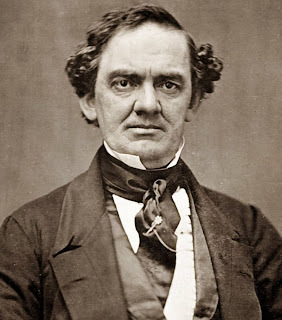

Phineas T Barnum, pictured in 1851 (public domain)

Phineas T Barnum, pictured in 1851 (public domain)

Long before the box-office blockbuster movie The Greatest Showman, loosely based upon his highly eventful life, was released in 2018, Phineas T. Barnum (1810-1891) was already world-famous as a slick 19th-Century American purveyor of curiosities. Barnum began what became a highly successful foray into this field by establishing a magnificent museum packed to the rafters with all manner of extraordinary specimens, many genuine but also including a sizeable number of deftly fabricated fakes, including one of the afore-mentioned Feejee Mermaids. But after his museum burnt down, he lost no time in assembling a new collection, one that featured both preserved and living exhibits, and which this time travelled with him throughout the USA and overseas too, in the form of a spectacular show unlike anything that had ever been seen before.

Moreover, although Barnum certainly eclipsed all would-be rivals in this phantasmagorical field, he didn't entirely extinguish them. Inspired by his success, a fair few loitered and even thrived in his shadow, presenting their own lesser but still financially lucrative exhibitions of oddities. Among these entertainers of the snake-oil sideshow variety was one notorious figure whom I always think of as "the other Barnum" – a certain self-styled Dr Albert C. Koch (evidently dismissing as a mere technicality the inconvenient fact that he had never actually obtained a doctorate!), who transformed his genuine passion for palaeontology into a money-making scheme of monstrous proportions, literally!

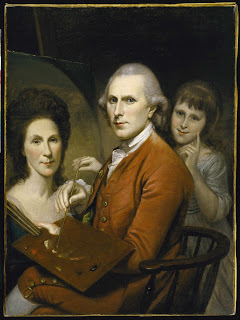

Charles W Peale, self-portrait (public domain)

Charles W Peale, self-portrait (public domain)

Born in 1804 in Roitzsch, near Dresden in Saxony, Germany, Koch emigrated to the USA in 1827 (not 1836 as often claimed – that is the year when he opened his museum in St Louis, see below). Several years later, his entrepreneurial epiphany was inspired from taking particular note of the financial success enjoyed by Peale's American Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, founded in 1805 by painter/naturalist Charles W. Peale (1741-1827). Its centrepiece was a magnificent mounted specimen of a fossil American mastodon Mammut americanum (although back then it was incorrectly dubbed a mammoth) that had been discovered in 1799 by farmer John Masten on his land outside Newburgh, New York.

It had subsequently been disinterred by a team of workers employed by Peale, who had then purchased it, paying Masten a total of US$ 800 for the specimen and the right to search his land for further remains. This was the first complete mastodon specimen ever procured and assembled, for which Peale cannily charged visitors an extra 50 cents on top of the museum's normal entry fee in order to view it. In 1806, Peale painted a somewhat dramatised rendition of this historic specimen's disinterment, entitled 'The Exhumation of the Mastodon'.

'The Exhumation of the Mastodon', painted by Charles W. Peale, 1806 (public domain)

'The Exhumation of the Mastodon', painted by Charles W. Peale, 1806 (public domain)

Consequently, in 1836 Koch opened a museum of his own, based in St Louis, Missouri, where he was currently living. It was principally dedicated to the exhibition of American natural history specimens and indigenous archaeological curiosities (although it did include performing magicians and ventriloquists too!). Some of these specimens were living or stuffed, others were long since deceased, as they included examples of his greatest passion – fossils. Indeed, Koch's primary purpose for opening his museum was to obtain sufficient money, via the entry fee that he charged to its visitors, to fund his palaeontological searches and excavations for ever more, ever greater fossil specimens.

Striving accordingly to elicit the maximum visitor footfall through his museum's doors, Koch was by no means averse to employing the same tricksy, theatrical advertising for which Barnum was infamous. Namely, employing the wiles of ambiguous exaggeration and factual flexibility in order to pull in credulous and credible visitors alike, from local yokels to eminent scientific figures, all equally curious to discover what was awaiting their attention within this extraordinary establishment. Yet to be fair, Koch's collections did include some very significant specimens too, especially within his assemblage of early Osage Nation artefacts that he had reputedly found alongside various excavated fossil animals, and in 1838 he had even successfully unearthed some fossil remains of a giant ground sloth Mylodon east of the Osage River in Missouri. However, in 1840 his museum would gain an exhibit that entirely – and literally – overshadowed all others.

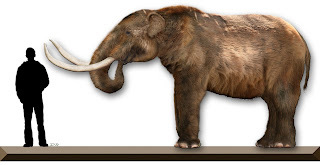

Modern reconstruction of an American mastodon in life alongside a human for scale purposes (© Dantheman9758/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Modern reconstruction of an American mastodon in life alongside a human for scale purposes (© Dantheman9758/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

On 24 March 1840, Koch learnt that a farmer living in Missouri's Benton County had found some remains of an enormous creature on his land. Mindful of the handsome monetary remunerations that the mastodon skeleton had garnished for Peale, and despite being beset with fever at that time, Koch swiftly travelled to meet the farmer there. Four months later, after supervising several different teams of workers, Koch was rewarded with the unearthing of a huge fossil skeleton, which he took back to his museum in St Louis and assembled into the most prodigious palaeontological creature that had ever been seen at that time.

Measuring 32 ft long and standing 15 ft high, this gargantuan mega-beast towered over Peale's mundane mastodon (indeed, it was so immense that a three-piece band was hired to play inside its ribcage!), and sported an enormous pair of tusks curving out laterally from its skull's jaws. But that was not all. As the pièce de resistance of his publicity campaign to promote this stupendous specimen, which he alleged to have resembled a vast hippopotamus-like creature with scaly alligator-like skin when alive (see more details later here), Koch sensationally claimed that it was nothing less than the fossilised reptilian remains of the ocean-dwelling biblical Leviathan itself!

The biblical Leviathan, as envisaged by Arthur Rackham (public domain)

The biblical Leviathan, as envisaged by Arthur Rackham (public domain)

Indeed, Koch clearly deemed his Missourium to be so good that, just like New York, he named it twice – formally dubbing it Missourium leviathan and also Leviathan missourii, both names translating as the Missouri Leviathan. (Moreover, in later advertisements, he also referred to it by yet another name, Missourium theristrocaulodon.) In colloquial parlance, he referred to it simply as the Missourium. So was the Missourium truly a latter-day remnant of Leviathan – "the dragon that is in the sea" (Isaiah 27:1)? Needless to say, the unspoken reality was very different from Koch's outspoken claim.

In fact, Koch's monumental Missourium was not a single specimen but a composite. That is to say, it was composed not merely from the fossil bones of the mastodon that Koch had unearthed in Benton County but also from various additional mastodon vertebrae, ribs, and limb bones that he had obtained in the Ozarks, most of which he had skilfully combined together to yield his colossal creation. While doing so, he increased its extended spinal column even further by surreptitiously adding concealed wood blocks between its supernumerary vertebrae. He also utilised the longest limb bones available in order to make this titanic entity far taller than any normal mastodon, as well as rotating its shoulder blades and pelvis to enhance its elevated height to an even more dramatic extent. And he had purposefully angled its tusks to splay out sideways and upwards, instead of correctly pointing them forwards and upwards, in order to increase still further this monstrous creature's perceived size and dramatic appearance. After all, Koch reasoned, if Peale's mastodon could pull in the crowds, how much more so would his even more spectacular Missourium?

19th-Century engraving of Missourium towering over a normal Asian elephant (public domain)

19th-Century engraving of Missourium towering over a normal Asian elephant (public domain)

The year 1841 saw the publication of a short pamphlet-style booklet authored by Koch that was very grandly (and wordily) entitled Description of the Missourium, or Missouri Leviathan; Together With Its Supposed Habits. And Indian Traditions Concerning the Location From Whence It Was Exhumed: Also, Comparisons of the Whale, Crocodile and Missourium, With the Leviathan, as Described in 41st Chapter of the Book of Job. In it, notwithstanding that he knew only too well that its subject was a blatant fake, Koch offered the following confident, and comprehensive, prediction of the appearance and lifestyle of the Missourium in the living state:

The animal has been without doubt an inhabitant of water courses, such as large rivers and lakes, which is proven by the formation of the bones: 1st, his feet were webbed; 2d, all his bones were solid and without marrow, as the aquatic animals of the present day; 3d, his ribs were too small and slender to resist the many pressures and bruises they would be subject to on land; 4th, his legs are short and thick; 5th, his tail is flat and broad: 6th and last, his tusks are so situated in the head that it would be utterly impossible for him to exist in a timbered country. His food consisted as much of vegetables as flesh, although he undoubtedly consumed a great abundance of the latter, and was capable of feeding himself with the fore foot, after the manner of the beaver or otter, and possessed, also, like the hypopotamus [sic], the faculty of walking on the bottom of waters, and rose occasionally to take air.

The singular position of the tusks has been very wisely adapted by the Creator for the protection of the body from the many injuries to which it would be exposed while swimming or walking under the water; and in addition to this, it appears that the animal has been covered with the same armor as the alligator, or perhaps the megatherium [prehistoric ground sloth].

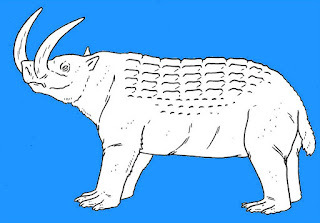

Reconstruction of Missourium in life, based upon Koch's above-quoted claims (© Tim Morris)

Reconstruction of Missourium in life, based upon Koch's above-quoted claims (© Tim Morris)

In fact, even a cursory examination of his Missourium skeleton would readily reveal that even if it had been genuine, many of Koch's assertions concerning it were eminently nonsensical. These include, but are not limited to: its feet being webbed (how could he deduce that, bearing in mind that its feet were actually those of a mastodon?); its ribs being too small and slender to resist damage if the creature had been terrestrial (we're talking about decidedly sturdy mastodon ribs here!); its legs being short (the Missourium stood a very lofty 15 ft tall); its tail was flat and broad (despite consisting of mastodon tail bones); its undoubted consumption of a great abundance of flesh (its exclusively herbivorous mastodon dentition would suggest otherwise); its ability to feed itself with its forefoot like a beaver or otter (not when possessing the highly inflexible skeletal structure of a mastodon's forelimb); and its body being covered with alligator-like armour, i.e. scaling (how could anyone assume that from what in reality were the assembled remains of conspicuously non-scaly mastodons?).

In the same laughable manner of hyperbolic hypothesising, Koch then presented a point by point comparison of his Missourium's predicted form and lifestyle with that of the biblical Leviathan in the Book of Job, and, unsurprisingly in view of his agenda for yielding a phoney phenomenon, concluded that the two great creatures were evidently one and the same species. And so it was that according to the highly imaginative gospel of Koch, the spectacular fossilised remains of a colossal reptilian sea monster from the holy scriptures came to be placed on public display by him inside a small Missouri museum for all to see (once an entry fee to do so had been paid, of course).

An advertisement for Koch's Missourium exhibition in the saloon at the rear of Tommey's Hotel (public domain)

Thanks to his Missourium, Koch's museum of wonders proved sufficiently successful to remain in business until he voluntarily sold it in 1841, having decided by then to emulate Barnum yet again by launching a touring show instead, with the Missourium assuming centre stage once more. After taking it across the USA, Koch ventured overseas, presenting his show in London, Dublin, and Germany, and advertising it with lurid posters and flyers that further exaggerated the dimensions of his Missourium, to the extent that a full-grown Asian elephant was depicted standing between its front and hind limbs underneath its belly! He also claimed that the reasons why its tusks were flared laterally were to protect itself from floating debris encountered when swimming in the sea, and to hang itself from underwater branches!

An advertisement for Koch's Missourium exhibition in the saloon at the rear of Tommey's Hotel (public domain)

Thanks to his Missourium, Koch's museum of wonders proved sufficiently successful to remain in business until he voluntarily sold it in 1841, having decided by then to emulate Barnum yet again by launching a touring show instead, with the Missourium assuming centre stage once more. After taking it across the USA, Koch ventured overseas, presenting his show in London, Dublin, and Germany, and advertising it with lurid posters and flyers that further exaggerated the dimensions of his Missourium, to the extent that a full-grown Asian elephant was depicted standing between its front and hind limbs underneath its belly! He also claimed that the reasons why its tusks were flared laterally were to protect itself from floating debris encountered when swimming in the sea, and to hang itself from underwater branches! Eventually, however, scientists visiting Koch's show not only perceived that the bones of his Missourium were mammalian, not reptilian, in nature (i.e. merely mastodon, as opposed to Leviathan!), but also readily discerned its composite nature. Yet because he recognised its scientific worth, due to it containing at least one complete, genuine mastodon skeleton, in 1843 the eminent British zoologist Prof. Sir Richard Owen from London's British Museum arranged for the latter establishment to purchase Koch's Missourium from him for £1300 (a very sizeable sum back in those days), plus an additional yearly payment of approximately £650. It was then dismantled, and a complete standard mastodon skeleton reassembled from its components, which is still on display at London's Natural History Museum today.

A mounted American mastodon skeleton (© Ryan Somma/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

A mounted American mastodon skeleton (© Ryan Somma/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Handsomely reimbursed for his multi-mastodon Missourium, what did Koch do next?

Why, construct an even more enormous pair of fossil sea serpent skeletons, of course – as will be revealed in Part 2 of this ShukerNature blog article, coming soon, so don't miss it!

An advertisement for Koch's Missourium exhibition at London's Egyptian Hall in 1843 (public domain)

An advertisement for Koch's Missourium exhibition at London's Egyptian Hall in 1843 (public domain)

July 22, 2021

MYSTERY OF THE MACAW MOSAIC - A (NOT SO) ROMAN RIDDLE?

The macaw-depicting mosaic panel sold by Christie's at auction in 2003 (© Christie's – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

The macaw-depicting mosaic panel sold by Christie's at auction in 2003 (© Christie's – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only) I'm very grateful to Brazil-based Facebook friend and parrot aficionado Rafael Nascimento for having kindly brought to my attention the most intriguing marble mosaic panel depicted at the beginning of this present ShukerNature blog article.

As seen, this mosaic panel is decorated with five bird depictions, shown variously surrounding and perched upon a water vessel, and according to its description in a catalogue produced by the famous auction house Christie's it is of Roman origin and dates from approximately the 2nd Century AD. This attractive artifact was sold on 11 December 2003 by Christie's for the very princely sum of US$ 107,550. Its previous owner was an unnamed private collector who had owned it since c.1980.

What is so intriguing about this 2nd-Century AD mosaic from a zoological standpoint, however, but which to my knowledge has never previously been pointed out in the cryptozoological literature, is that it depicts a blue-and-yellow macaw Ara ararauna (aka blue-and-gold macaw). This is a readily-recognisable parrot species native to South America – i.e. a continent whose own existence (let alone that of its indigenous fauna) was not discovered by the West for another 1300 years! So how can this anachronistic ornithological anomaly be explained?

It is remotely conceivable that the mosaic has been partially reconstituted in modern times but with a South American macaw erroneously added rather than an African parrot when filling the gaps. Yet judging from the photograph of it reproduced here, it doesn't look as if this mosaic has been reconstituted in any way, and even if it had been, this would surely have been alluded to in its description by Christie's.

Nevertheless, if we assume that this mosaic has not been reconstituted, and also that it neither is a fake nor has been misidentified but is indeed genuine, then we must also assume that the macaw's depiction upon it indicates that Romans were trading with South America many centuries before this continent was supposedly revealed to Europe. And if so, this mosaic constitutes an immensely significant historical artifact.

Worth noting, incidentally, is that whoever wrote its description for Christie's catalogue was clearly not well-versed in ornithology. For what they referred to as a pileated woodpecker is actually a hoopoe (bottom right in the mosaic), what they called a greenfinch is a European roller (top right, perched upon the water vessel), and what they termed a chaffinch is a goldfinch (top left). Indeed, the only correctly-identified bird on the mosaic was the partridge (bottom left). Let us hope, therefore, that their dating and authenticity abilities in relation to this particular object were more accurate – but were they?

A blue-and-yellow macaw (copyright-free)

A blue-and-yellow macaw (copyright-free)

For if this macaw-depicting mosaic truly provided firm evidence of Roman trading with South America, why had it not attracted considerable attention from historians and archaeologists? A detailed online search by me concerning it had proved singularly unable to uncover any evidence of such attention. Not surprisingly, I was very mystified, but I subsequently obtained some information that may conceivably explain these anomalies.

My discovery began via fellow cryptozoological investigator Andy McGrath, who kindly informed me that after reading some posts concerning it on Facebook and a short report by me in my regular Alien Zoo column in Fortean Times, he had discovered that due to how attractive this mosaic panel was, it had actually been pictured on the front cover of the Christie's catalogue containing it. This fact proved invaluable to me in uncovering some very thought-provoking additional information.

In early 2021, the eagerly-awaited English-language edition of a fascinating book written by Dutch art crime detective/investigator Arthur Brand and entitled Hitler's Horses was published (after originally appearing in Dutch as De paarden van Hitler in 2019). It documented the incredible real-life story of how 'Striding Horses' by Nazi sculptor Josef Thorak, a spectacular statue featuring two gigantic bronze horses, which had been a favourite of Adolf Hitler but had later vanished, long assumed destroyed during the bombing of Berlin in World War II, was sensationally rediscovered via some complex, dangerous sleuthing by Brand.

Mentioned almost in passing within Brand's book, moreover, were some most intriguing details relevant to the macaw mosaic. Brand recalled a conversation that he'd had with an enigmatic figure from the art world named Michel van Rijn, during which van Rijn had shown him an auction catalogue whose cover had depicted a Roman mosaic panel depicting five birds around a drinking vessel, one of these birds being a South American blue and yellow macaw! (Although not named, judging from Brand's description of the mosaic panel this catalogue must surely have been Christie's?) Bursting out laughing, Brand had asked where this forgery (his word) had originated. Here is van Rijn's reply:

Tunisia, I think. There's a village just south of Sousse where they churn out fake Greek and Roman mosaics. A regular goldmine.

I wish to make absolutely clear here that I am entirely unaware of any formal, professional confirmation that this particular artefact is indeed a fake, a forgery. Yet if what van Rijn had said about it and the veritable mosaic fake factory operating near Sousse does have merit, might this be why the macaw mosaic panel has signally failed to influence the accepted mainstream views concerning early Roman trading?

The original 2019 Dutch edition of Hitler's Horses, by Arthur Brand (© Arthur Brand/Boekerij – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

The original 2019 Dutch edition of Hitler's Horses, by Arthur Brand (© Arthur Brand/Boekerij – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

July 16, 2021

'THE BOY WHO SAW BIGFOOT' - BOOKING MY REDISCOVERY AT LONG LAST OF A CRYPTOZOOLOGY NOVEL LONG LOST!

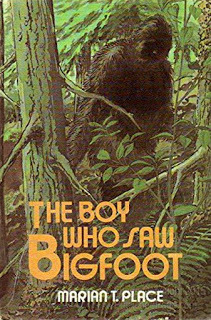

The very evocative front cover of my Weekly Readers Books hardback edition of The Boy Who Saw Bigfoot, a novel written by Marian T. Place and first published in 1979 by Dodd, Mead & Company (© Marian T. Place/Dodd, Mead & Company/Weekly Readers Books – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

The very evocative front cover of my Weekly Readers Books hardback edition of The Boy Who Saw Bigfoot, a novel written by Marian T. Place and first published in 1979 by Dodd, Mead & Company (© Marian T. Place/Dodd, Mead & Company/Weekly Readers Books – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only) Friends and colleagues, including loyal ShukerNature readers, will be very familiar with my succession of searches in recent times for various unusual books, magazines, records, and artefacts that I once fleetingly encountered many years previously but inexplicably failed to purchase and which have eluded all of my attempts since then to identify and very belatedly buy them. Happily, however, quite a few of these recent searches by me have finally ended in success, and the cryptozoologically-relevant example documented here is one of them.

It was during the evening of 7 April 2021 when I scored this particular "identified at last after all these years" successes. On that occasion, my search had been the latest one in a lengthy succession spanning a quartet of decades, seeking a very specific bigfoot-themed novel that for so long had seemed no less elusive than its cryptid subject! Here is the back-story to my quest for it.

One Bank Holiday Tuesday during the early 1980s, my family and I visited the Welsh seaside city of Newport for the day, where, while walking around the shops in its central area (by my early 20s, I'd long since lost interest in sitting on a beach!), Mom and I came across a big second-hand bookshop. Needless to say, I swiftly entered it and began a perusal of its wares, especially as this shop was totally new to me.

While doing so, I chanced upon a slender hardback book with a very attractive drawn illustration that wrapped around its entire front cover, spine, and back cover, and which was mainly brown with some green, featuring a bigfoot on the front. I opened it, but when I discovered that it was a children's novel rather than a work of non-fiction, I placed it back on the shelf, and eventually left the bookshop without buying anything – a rare event indeed for me!

A typical shopping street in Newport city centre, Wales (© Paula Rogers/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0licence

)

A typical shopping street in Newport city centre, Wales (© Paula Rogers/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0licence

)

Once back home, however, as so often happens with me, I began to wish that I'd bought the book after all, even if only as a novelty or souvenir, as it wasn't expensive and I'd never seen it before. Unfortunately, Newport was a very considerable distance away from where we lived, so there was no question of travelling all the way back there to buy it. I've only visited Newport once since then, several years later, and although the shop was still there, the bigfoot book had gone.

Regrettably, I hadn't taken notice of either its title or its author while looking at this book's cover, my attention having been focused upon its very striking wraparound illustration instead. Nevertheless, the memory of it has occasionally popped into my head during the subsequent four decades, as it did again on 7 April. However, after having failed on several previous occasions, this time I was determined to track down this long-vanished volume and identify it. And after scouring through untold lists of bigfoot-entitled books that night on ebay, Abebooks, Amazon, etc, I did indeed finally find it!

I did so by entering "bigfoot children's novel 1970s" in Google's Image Search (because I'd seen the book during the early 1980s, I guessed that it had probably been published in the 1970s – any earlier would have been most unlikely because bigfoot wasn't a well-known cryptid prior to the 1968 Patterson-Gimlin film). Sure enough, up popped a picture of the entire cover of a book, front and back, featuring a wraparound illustration that immediately clicked in my memory – that was it, that was the very same cover whose striking image had stayed with me all these years!

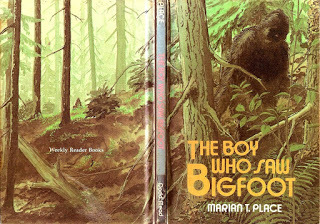

The book turned out to be The Boy Who Saw Bigfoot, a 96-page hardback novel aimed at young people, written by American children's authoress and bigfoot seeker Marian T. Place, who has also written various other bigfoot-themed novels for youngsters (as well as one non-fiction book), which was first published in 1979 by New York-based publisher Dodd, Mead & Company. I soon found for sale online a reasonably-priced good-condition copy of the Weekly Readers Books hardback edition featuring that same iconic cover illustration and published that same year, which I purchased straight away. It arrived safely from the States about a fortnight later. So after more than 40 years, I finally own this hitherto nebulous novel, and I now look forward to reading it at last. Finally: here is that very memorable wraparound cover that finally solved for me the longstanding mystery of the missing bigfoot book:

The very eyecatching full wraparound cover from my Weekly Readers Books hardback edition of The Boy Who Saw Bigfoot (© Marian T. Place/

Dodd, Mead & Company/Weekly Readers Books – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

The very eyecatching full wraparound cover from my Weekly Readers Books hardback edition of The Boy Who Saw Bigfoot (© Marian T. Place/

Dodd, Mead & Company/Weekly Readers Books – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

July 15, 2021

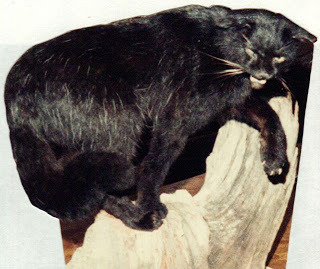

KELLAS CATS, RABBIT-HEADED CATS, FAIRY CATS, AND DAEMON CATS - A CLOWDER OF FORMER FELINE CURIOSITIES

The late Corinna Downes from the Centre of Fortean Zoology alongside a taxiderm Kellas cat (© Jonathan Downes/Centre of Fortean Zoology)