Karl Shuker's Blog, page 11

June 21, 2021

THE DINOSAURS OF CRYSTAL PALACE - VISITING LONDON'S LOST WORLD. Part 2: WELCOME TO THE AGE OF REPTILES!

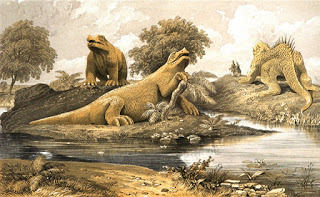

The Crystal Palace dinosaurs, in Views of the Crystal Palace and Park, Sydenham (1854), by Matthew Digby Wyatt with P.H. Delamotte (public domain)

The Crystal Palace dinosaurs, in Views of the Crystal Palace and Park, Sydenham (1854), by Matthew Digby Wyatt with P.H. Delamotte (public domain)

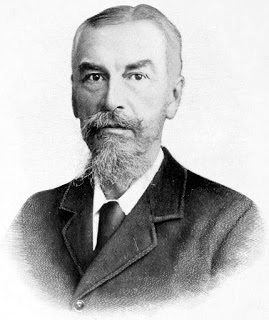

Yesterday, in Part 1 of this 3-part ShukerNature blog article (click hereto access it), we began a virtual, verbal tour of a veritable Lost World in leafy southeast London – Crystal Palace Park's famous Dinosaur Court. It contains a spectacular series of life-sized statues dating back to the 1850s, which had been created by English sculptor and artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins under the supervision of leading British zoologist and palaeontologist Prof. Sir Richard Owen.

They represent no fewer than 20 different species of prehistoric animal, reconstructed with varying degrees of accuracy compared to today's palaeontological counterparts, but still unmatched in terms of artistic magnificence. We have already visited the Court's Cenozoic mammals, but now, here in Part 2, we shall be viewing its most celebrated and stupendous sculptures – a menagerie of reptilian monsters from the Mesozoic Era, the Age of Reptiles, whose most familiar examples are its trio of dinosaur forms.

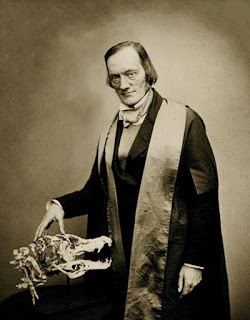

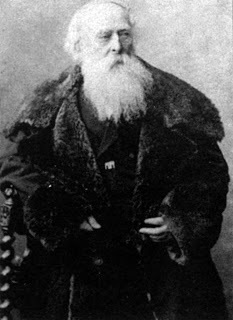

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (Maull & Polyblank Wellcome/Wikipedia –

CC BY 4.0 licence

)

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (Maull & Polyblank Wellcome/Wikipedia –

CC BY 4.0 licence

)

These dinosaurs, all originally known from fossils excavated in England, are represented by a statue of the Jurassic carnivorous theropod Megalosaurus bucklandi, two composite statues of the Jurassic/Cretaceous herbivorous ornithopod Iguanodon (as these were apparently based upon fossil material derived from at least two if not three different iguanodont species), and a statue of the early Cretaceous herbivorous ankylosaur Hylaeosaurus armatus. Whenever anyone talks about Crystal Palace Park's prehistoric animals, it is this exceedingly impressive quartet of stately sculptures that always comes to mind, because they absolutely epitomize the anatomical inaccuracy by present-day standards yet truly iconic, idiosyncratic grandeur of Hawkins's creations. Having said that, the dinosaurs in particular are actually not as inaccurate as they might have been, as will now be explained.

To my mind, the most magnificent of Hawkins's dinosaurs is his enormous Megalosaurus, standing aloof and majestic, the absolute monarch of Secondary Island beyond any shadow of doubt. Yet in morphological terms it resembles an incongruous hybrid of reptile and mammal. For whereas it sports an unequivocally reptilian head, vaguely crocodilian in profile, and its body is covered in scales, it also possesses a muscular, ostensibly mammalian shoulder hump, as well as four vertical, upright limbs, a typically mammalian characteristic. So how can its curiously composite form be explained?

The Crystal Palace Megalosaurus (© Dr Karl Shuker)

The Crystal Palace Megalosaurus (© Dr Karl Shuker)

When in the 1820s dinosaur remains were first scientifically named, described, and recognized to be giant reptiles, some scientists assumed that they were nothing more than gigantic lizards, and illustrations dating from that time period duly depicted them as such. Consequently, had Hawkins heeded those views, he would have reconstructed his dinosaurs not only as quadrupeds (as he did do) but also as ones whose limbs splayed out laterally from their bodies, just like those of lizards do. Fortunately, however, he took his lead from Owen instead, who was convinced that far from simply being enormous lizards, the dinosaurs represented nothing less than the zenith of reptilian development. As a result, in 1841 Owen allocated them to an entirely new taxonomic suborder of reptiles, which he grandly christened Dinosauria ('terrible lizards').

Moreover, based upon his studies of those fossil remains so far disinterred, especially their mighty ribs and limb bones, Owen opined that the dinosaurs' great size would necessarily have incorporated much deeper bodies proportionately speaking than those of lizards, crocodiles, and other present-day reptiles. This in turn would have required their limbs to be sturdier and, crucially, vertical in stance, holding their heavy bodies upright just as the vertical limbs of mammals do.

My mother Mary Shuker and I with Hawkins's iconic Megalosaurus statue during our visit to Crystal Palace Park's Dinosaur Court on 22 April 2010 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My mother Mary Shuker and I with Hawkins's iconic Megalosaurus statue during our visit to Crystal Palace Park's Dinosaur Court on 22 April 2010 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Consequently, when referring to Megalosaurus in his groundbreaking 1841 monograph on British fossil reptiles, Owen confidently stated:

From the size and form of the ribs it is evident that the trunk was broader and deeper in proportion than in modern Saurians, and it was doubtless raised from the ground upon extremities proportionally larger and especially longer, so that the general aspect of the living Megalosaur must have proportionally resembled that of the large terrestrial quadrupeds of the Mammalian class which now tread the earth.

Megalosaurus

model by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, c.1852, Oxford Museum, England (© Ballista/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Megalosaurus

model by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, c.1852, Oxford Museum, England (© Ballista/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

It was these comments by Owen that directly influenced Hawkins's designing of Megalosaurus and, to a slightly lesser extent, his other dinosaurs too, as veritable mammalian reptiles, or reptilian mammals, depending upon which taxonomic component of their form any given observer most readily notices. In my case, it was the reptilian head and body scales of Megalosaurusthat first attracted my attention, albeit followed very closely by the surprising realization of just how mammalian its body shape, stature, and stance were – almost like some bizarre coalescence of crocodile and rhinoceros, or alligator and elephant! Indeed, so many people at one time or another have likened this particular statue to a reptilian rhino that I can't help but wonder whether, instead of calling it a dinosaur, we would do better by dubbing it a rhinosaur!

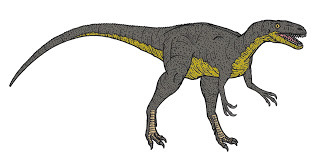

Today, conversely, Megalosaurus is typically reconstructed as a bipedal dinosaur (the concept that some dinosaurs were bipedal was first raised in 1858, too late for Hawkins to utilize it with his creations), possessing longer forearms but otherwise superficially reminiscent of its mighty Cretaceous relative, Tyrannosaurus rex. This is undoubtedly a much more accurate rendition palaeontologically, but is in my opinion a far less memorable, romantic one aesthetically than the Crystal Palace version.

Hawkins's Megalosaurus statue, Crystal Palace (© CGPGrey/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Hawkins's Megalosaurus statue, Crystal Palace (© CGPGrey/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

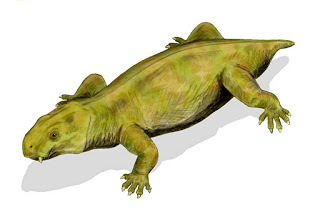

Modern-day reconstruction of Megalosaurus(Conty/Wikipedia – public domain)

Modern-day reconstruction of Megalosaurus(Conty/Wikipedia – public domain)

In the case of the two Iguanodon statues (one constructed standing, the other reposing with one front paw resting indolently upon a reconstructed cycad), their most noticeable feature is the short pointed horn perched somewhat precariously upon the tip of their snout. Yet even Owen was by no means convinced that this structure was valid, expressing his doubts as far back as 1854, which were duly vindicated when further remains and studies revealed that this supposed 'horn' was actually a pointed thumb digit!

Also, once again their quadrupedal stance has since been supplanted, first of all by reconstructions portraying Iguanodon as habitually bipedal, but later still by the currently accepted view that it was both bipedal and quadrupedal, its stance dictated by what it needed to do at any given time.

Hawkins's two Crystal Palace Iguanodon statues (© Ian Wright/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Hawkins's two Crystal Palace Iguanodon statues (© Ian Wright/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Modern-day reconstruction of Iguanodon (public domain)

Modern-day reconstruction of Iguanodon (public domain)

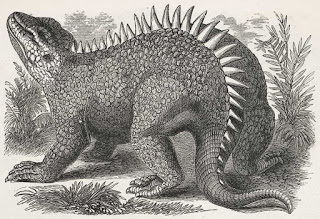

As for Hylaeosaurus: this is an early Cretaceous ankylosaur, which just for a change is still restored today as a quadruped. Hawkins reconstructed it as a much more lizard-like dinosaur than his quasi-mammalian Megalosaurus statue and his two Iguanodon statues, and he equipped its scaly body with an eyecatching mid-dorsal ridge of long pointed spines running from its neck down the entire length of its back to the end of its long powerful tail.

Even today, little is known of the overall appearance of Hylaeosaurus, because few remains have been uncovered (it is now recognised that Hawkins unknowingly utilized fossils from a wide range of different, but at that time undifferentiated, dinosaurs for inspiration when creating his statue of it). However, some researchers have conjectured that it may have sported not just one but several rows of these spines, bearing them laterally upon its flanks too, not only along its back – more like a reptilian porcupine, in fact, than Hawkins's giant lizard lookalike! Incidentally, its head is a modern fibreglass replica – the original was removed or fell off many years ago (further details concerning it will appear tomorrow in Part 3 of this ShukerNature blog article).

Hawkins's Crystal Palace Hylaeosaurus statue (© Simon/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Hawkins's Crystal Palace Hylaeosaurus statue (© Simon/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

19th-Century engraving based upon Hawkins's Crystal Palace Hylaeosaurusstatue, depicting it looking straight ahead, rather than facing away (the latter being how this statue is positioned in situ) (public domain)

19th-Century engraving based upon Hawkins's Crystal Palace Hylaeosaurusstatue, depicting it looking straight ahead, rather than facing away (the latter being how this statue is positioned in situ) (public domain)

Meanwhile, high upon a fabricated cliff behind the dinosaurs squat a pair of what by today's standards are decidedly strange-looking pterosaurs, with slender toothy jaws but heavily-scaled bodies, membranous bat-like wings that seem oddly oriented, erroneously avian limb posture and body shape, plus long, curved, swan-like necks. Looking up at them, I remember thinking that these winged monstrosities would not look out of place as stony gargoyles perched atop some lofty ledge on the exterior of a gothic cathedral!

The limestone cliff upon which they were originally sited was deliberately blown up during a less-than-successful park modification attempt in the 1960s. However, it was replaced during the extensive restoration work of 2002 by a new cliff, created from Derbyshire limestone, at whose summit these pterosaurs were then duly relocated.

Hawkins's Crystal Palace statues of 'Pterodactylus cuvieri' (© Ben Sutherland/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Hawkins's Crystal Palace statues of 'Pterodactylus cuvieri' (© Ben Sutherland/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

In Owen's time, their species was named Pterodactylus cuvieri, but today this is believed to have been based upon remains from more than one species, and they are now deemed to be representatives of the genus Cimoliopterus. The fossils upon which they were based had been derived from British chalk deposits of the Cretaceous Period.

There was once a pair of smaller but extremely elegant pterosaur statues on display here too, perched upon a rock by the teleosaurs (see later), which were notable for their billowing sail-like wings. They were based upon an uncertain species referred to back then as Pterodactylus [later Rhamphocephalus] bucklandi, but they were known colloquially as the Oolite pterosaurs because the fossils upon which they were based had been found in British Oolite rocks, dating from the Jurassic. Tragically, however, as I'll be revealing tomorrow in Part 3, Fate – or, to be more precise, the general public – was less than kind to them.

Section from a vintage picture postcard depicting the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, which includes the two small, now-lost Oolite pterosaurs, arrowed (public domain)

Section from a vintage picture postcard depicting the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, which includes the two small, now-lost Oolite pterosaurs, arrowed (public domain)

Reposing on Secondary Island's shore and also residing in its offshore waters, as well in as those of Primary Island, are a sundry array of aquatic Mesozoic reptiles. These consist of three plesiosaurs, three ichthyosaurs, and two marine crocodilians, based upon remains originating from such famous English fossiliferous locations as Lyme Regis and Whitby.

There is also a semi-submerged mosasaur, sited apart from the others in a dam setting at the edge of Secondary Island nearest to Tertiary Island, and based upon Dutch fossils.

Overview of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs and lake reptiles (© Nick Richards/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Overview of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs and lake reptiles (© Nick Richards/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

The three plesiosaurs were reconstructed by Hawkins according to the popular Victorian misapprehension that these water monsters' elongate necks were inordinately flexible, virtually able to tie themselves in knots, in stark contrast to modern-day views that they were in fact relatively inflexible, stretching forward in a fairly stiff horizontal manner. Their bodies are also more slender and supple than is nowadays believed for such reptiles.

Each plesiosaur statue represents a different species. Namely, Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus, "P." [=Rhomaleosaurus?] macrocephalus, and Thalassiodracon hawkinsi. However, there is some modern-day disagreement as to which statue represents which species.

Hawkins's three Crystal Palace plesiosaur statues (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Hawkins's three Crystal Palace plesiosaur statues (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Hawkins's trio of ichthyosaurs (again each one representing a different species) look distinctly odd too, due in no small way to their conspicuous lack of both a dorsal fin and the very large vertical shark-like tail fin that all but the earliest of these marine reptiles are now known to have possessed. Instead, Hawkins simply gave them long flat tails emerging directly from their backbone (plus a small flat terminal protuberance for the biggest ichthyosaur's tail), and he positioned these creatures resting partly out of the water on the island's shore, more like seals than sea reptiles.

In addition, their large eyes are encircled with exposed bony sclerotic plates, which are indeed present in fossil ichthyosaur remains but were much more likely to have been hidden beneath skin in the living animals (as they are in various modern-day creatures that possess them). The three species represented are Temnodontosaurus platydon (the largest member of this trio), Ichthyosaurus communis (the mid-sized one), and Leptonectes tenuirostris (the smallest).

Two of Hawkins's three Crystal Palace ichthyosaur statues – Temnodontosaurus platydon in foreground, with the head of Leptonectes tenuirostris visible in background (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Two of Hawkins's three Crystal Palace ichthyosaur statues – Temnodontosaurus platydon in foreground, with the head of Leptonectes tenuirostris visible in background (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Two of Hawkins's three Crystal Palace ichthyosaur statues – Leptonectes tenuirostris at back, Ichthyosaurus communis in front (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Two of Hawkins's three Crystal Palace ichthyosaur statues – Leptonectes tenuirostris at back, Ichthyosaurus communis in front (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Two marine crocodilians, Teleosaurus, are also present, sporting very long, slender gharial-like jaws, elongate bodies, long tails, and clawed shortish limbs, which is how this prehistoric oceanic reptile is still restored today. Unfortunately, their scales are visibly based upon those of modern-day crocodiles rather than fossil teleosaurs.

Teleosaurs belong to the now-extinct suborder of crocodilians known as thalattosuchians. Some of its members included fully aquatic species whose limbs had evolved into paddle-shaped flippers, unlike the clawed limbs of teleosaurs.

Hawkins's two Crystal Palace Teleosaurusstatues (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Hawkins's two Crystal Palace Teleosaurusstatues (© Dr Karl Shuker)

As for the mosasaur: at the time of Hawkins's statue, only the appearance of these varanid-related aquatic lizards' head was known. So, supplemented merely by a generic scaly upper back portion and a single forelimb, this is all that Hawkins created, skilfully positioning this very incomplete statue so as to create the illusion that its largely non-existent body was actually present but submerged beneath the water surface!

Having said that, Hawkins was more than happy to improvise then-undescribed body portions for various other creatures here, including the dinosaur Hylaeosaurusand the therapsid Dicynodon (see later). Hence it seems odd that he didn't do the same for this mosasaur. Its species is Mosasaurus hoffmanni.

Hawkins's Crystal Palace Mosasaurus statue (© Andrew Wilkinson/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Hawkins's Crystal Palace Mosasaurus statue (© Andrew Wilkinson/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Modern-day reconstruction of Mosasaurus (Dimitry Bogdanov/Wikipedia

– public domain)

Modern-day reconstruction of Mosasaurus (Dimitry Bogdanov/Wikipedia

– public domain)

Continuing along Dinosaur Court's mainland footpath that leads past each of the islands and takes the visitor ever further back in geological time, the Mesozoic's giant reptilian mega-stars of land, air, and water that are present on and around Secondary Island are now left behind, and five statues of smaller, less familiar archaic herpetological creatures are encountered on Primary Island, near the water edge.

Three of these are prehistoric amphibians, specifically temnospondyls – a diverse, long-extinct taxonomic group that includes various amphibians formerly categorized as either labyrinthodonts or stegocephalians. Moreover, unlike any amphibians alive today, some temnospondyls were scaly-skinned, like reptiles; others, conversely, were smooth-skinned, like modern-day amphibians.

19th-Century drawing of Hawkins's Crystal Palace statue of Mastodonsaurus jaegeri, aka Labyrinthodon salamandroides, a temnospondyl (public domain)

19th-Century drawing of Hawkins's Crystal Palace statue of Mastodonsaurus jaegeri, aka Labyrinthodon salamandroides, a temnospondyl (public domain)

Modern-day reconstruction of Mastodonsaurus (public domain)

Modern-day reconstruction of Mastodonsaurus (public domain)

The largest temnospondyl species could attain lengths of up to 20 ft, i.e. far bigger than any modern-day amphibian. Moreover, we know today from abundant fossil evidence that they were long-jawed, long-tailed, lengthy-bodied beasts, superficially resembling crocodiles, with smaller ones resembling salamanders.

Back in the days of Owen and Hawkins, conversely, with far fewer uncovered fossils available for study, it was wrongly assumed that they simply looked like very large frogs. Hence this is how Hawkins reconstructed the bodies of the two temnospondyl species on display here in Dinosaur Court, adding only short stumpy tails, although he did provide their heads with longer jaws than those of frogs.

Hawkins's Crystal Palace statue of Mastodonsaurus jaegeri, aka Labyrinthodon salamandroides (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Hawkins's Crystal Palace statue of Mastodonsaurus jaegeri, aka Labyrinthodon salamandroides (© Dr Karl Shuker)

One of these species, represented by a single large statue, was known back then as Labyrinthodon salamandroides, but was subsequently renamed during various reclassifications, and is currently referred to as Mastodonsaurus jaegeri. Hawkins reconstructed it with smooth skin. It lived in what is today Europe, including the UK, during the early Mesozoic's mid-Triassic Period, 247-237 million years ago, and is nowadays believed to have been predominantly aquatic, rarely leaving the water, whereas Hawkins positioned his statue of it on land. The biggest specimens were up to 20 ft long.

The other species, represented by a couple of smaller statues, was known in Hawkins's time as Labyrinthodon pachygnathus, but today is called Cyclotosaurus pachygnathus. This was a temnospondyl with scaly skin, which Hawkins duly incorporated into his reconstruction, but otherwise his statue of it looks very similar to his Mastodonsaurus specimens, i.e. frog-like but with fairly long jaws. It existed from the mid to late Triassic Period, which ended around 200 million years ago, grew up to 14 ft long, and lived in Europe, especially in what is now Germany.

Hawkins's two Crystal Palace statues of Cyclotosaurus pachygnathus aka Labyrinthodon pachygnathus (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Hawkins's two Crystal Palace statues of Cyclotosaurus pachygnathus aka Labyrinthodon pachygnathus (© Dr Karl Shuker)

The final two statues displayed on Dinosaur Park's Primary Island, one somewhat larger than the other, represent a strange creature known as Dicynodon, which existed in what is now South Africa, and dates further back in time than any other animal form represented here. Flourishing during the upper Permian Period of the late Palaeozoic Era, approximately 252 million years ago (certain Triassic species have also been described but these are all nowadays reclassified in other genera), Dicynodon was a therapsid, That is, it belonged to a reptilian group commonly dubbed the mammal-like reptiles, because this was the group that did indeed give rise to the mammals, evolving certain anatomical features that would characterize the mammals once the therapsids themselves died out.

Unfortunately, however, back in Hawkins's day, this reptile was principally known only from skulls, which were characterized by a pair of sizeable upper tusks and a horny tortoise-like beak. Consequently, adhering to Owen's conjecture that its body may have borne a shell, Hawkins accordingly reconstructed Dicynodonas a veritable sabre-toothed tortoise, and sporting not only a domed chelonian carapace but also a scute-bearing tail reminiscent of the American snapping turtle's. This is of course all dramatically different from the shell-less, barrel-bodied, mammalian predecessor that we now know this reptile to have been. Herbivorous by nature, Dicynodonis believed to have used its two large upper tusks (which were its only teeth) for digging up roots and tubers, whereas its beak was probably used for cropping vegetation.

Hawkins's two Crystal Palace Dicynodon statues (© Ben Sutherland/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Hawkins's two Crystal Palace Dicynodon statues (© Ben Sutherland/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Rear view of Hawkins's two Crystal Palace Dicynodon statues, showing their tail scutes (© Loz Pycock/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Rear view of Hawkins's two Crystal Palace Dicynodon statues, showing their tail scutes (© Loz Pycock/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Modern-day reconstruction of Dicynodon (Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.5 licence

)

Modern-day reconstruction of Dicynodon (Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.5 licence

)

Continuing along the mainland footpath leads round to the opposite side of the islands, which afforded a clearer view of the pterosaurs and the giant ground sloth when I visited in 2010, before finally ending full circle back at the entrance.

Unexpectedly, just before the entrance is reached, a statue of London Zoo's famous former resident Guy the Gorilla is encountered – offering some great opportunities for selfies!

The statue of London Zoo's Guy the Gorilla in Crystal Palace Park (© Dr Karl Shuker)

The statue of London Zoo's Guy the Gorilla in Crystal Palace Park (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Having now completed our virtual tour of Crystal Palace's Dinosaur Court, tomorrow, in Part 3 of this ShukerNature blog article, its spectacular exhibits' continual battle against the ravages of time, not to mention wanton vandalism, will be revealed.

We shall also look further afield, to discover what would have – should have – been Hawkins's supreme, transatlantic triumph. But as will be seen, Fate – and inhuman humanity – had other ideas. Don't miss it! And be sure to click hereto read Part 1, posted on ShukerNature by me yesterday.

One of Hawkins's Crystal Palace Teleosaurusstatues alongside a very much alive grey heron! (© Chris Sampson/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

One of Hawkins's Crystal Palace Teleosaurusstatues alongside a very much alive grey heron! (© Chris Sampson/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

June 19, 2021

THE DINOSAURS OF CRYSTAL PALACE - VISITING LONDON'S LOST WORLD. Part 1: MEGALOSAURUS, MEGALOCEROS, MEGATHERIUM, AND MORE!

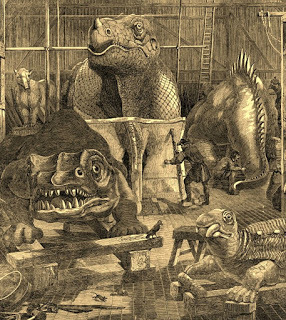

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's Crystal Palace studio in 1853, containing some of his completed statues of prehistoric 'monsters' (public domain)

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's Crystal Palace studio in 1853, containing some of his completed statues of prehistoric 'monsters' (public domain)

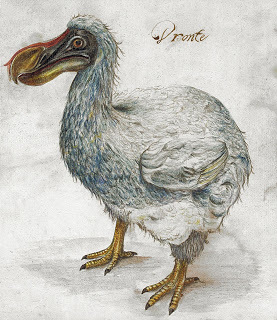

On 22 April 2010, I finally fulfilled a lifelong ambition, by visiting a veritable Lost World of dinosaurs and other monstrous members of our planet's prehistoric fauna. Yet this particular Lost World was located not atop some lofty South American mesa, or concealed amid some remote African rainforest. Instead, it was cosily ensconced within a leafy, tranquil setting not very far from the frantic hustle and bustle of central London. I refer of course to Crystal Palace Park, and its spectacular array of life-sized (albeit far from life-like) palaeontological reconstructions, which date back to Victorian times and include the earliest representations of dinosaurs ever created.

Today, they are considered by many to be nothing more than antiquated curiosities, at least as far as their direct relevance to modern-day fossil studies is concerned. Yet in historical terms, their significance is immense, as is their aesthetic value as stunning works of art. So here via this comprehensive 3-part ShukerNature blog article, I invite you all to pay a virtual, verbal visit with me to these extraordinary creations, and uncover their fascinating histories and mysteries.

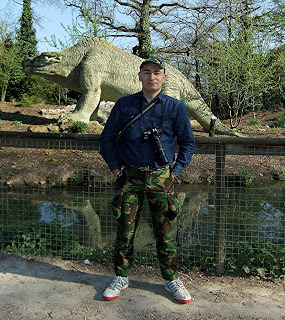

Standing in front of the iconic Megalosaurus statue in the Dinosaur Court at Crystal Palace Park, London, on 22 April 2010 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Standing in front of the iconic Megalosaurus statue in the Dinosaur Court at Crystal Palace Park, London, on 22 April 2010 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

I first learnt of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs from one particular animal book that (along with many others) my mother had bought me when I was a child, back in the 1960s. A compilation of chapters written by several different authors, and which I still own today as a fond reminder of my early years, it was entitled Children's Encyclopedia of Knowledge: Book of Nature, and had been published by Collins in 1967. I'd also been bought a number of books devoted specifically to dinosaurs and other prehistoric beasts. Yet whereas the respective reconstructions in these latter books of the various famous dinosaurs' likely appearance in life all compared well with one another, those in my Book of Nature were radically different. This notable discrepancy puzzled me for some time until I finally uncovered the answer.

The dinosaur illustrations in the above-named book were photographs of enormous statues on display in southeast London's Crystal Palace Park, but they more closely resembled giant, misshapen lizards than the very distinctive, familiar forms depicted in all of my dinosaur books. Back in those far-distant pre-internet times, it took a while for me to learn more about them, but during the mid-1970s I bought Adrian J. Desmond's bestselling book The Hot-Blooded Dinosaurs (1975), which included a fascinating history of how and when the first dinosaur remains had been discovered, and it was here that the secret of Crystal Palace Park's mystifying monsters was at last revealed to me.

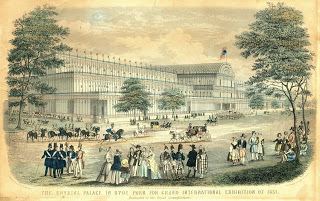

Vintage engraving of the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, for the Great Exhibition, 1851 (public domain)

Vintage engraving of the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, for the Great Exhibition, 1851 (public domain)

The year 1851 saw Central London's Hyde Park host the world-famous Great Exhibition (1 May-15 October), which was a huge exposition showcasing the finest achievements of British industry as well as including displays from other countries around the world too. It was housed within a spectacular, palatial exhibition centre designed by Sir Joseph Paxton and composed extensively of glass, which duly became known as the Crystal Palace. Although initially intended to be merely a temporary creation, so popular did this very imposing, impressive edifice prove to be that when the Great Exhibition ended, instead of being demolished the Crystal Palace was purchased for £50,000 by the new, specially-created Crystal Palace Company, which then paid for it to be dismantled and moved in its entirety from Hyde Park to Penge, situated on the lower slopes of Sydenham Hill, southeast London.

Here it was painstakingly reassembled and became the focus of a new, specially-designed park, with beautiful landscaped gardens, lakes, statues, and many other eyecatching features. These included what became its most famous attractions – the incredible statues of huge dinosaurs and other exotic-looking prehistoric animals created by English sculptor and artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807-1894).

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins sitting (Maull & Polyblank Wellcome/Wikipedia –

CC BY 4.0 licence

)

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins sitting (Maull & Polyblank Wellcome/Wikipedia –

CC BY 4.0 licence

)

Despite having become extinct many millions of years ago, dinosaurs are among the most popular of all animals in today's world, their diverse imagery appearing everywhere, from books and films to toys and postage stamps, as well as being represented by countless displays in museums worldwide. All of which makes it all the more surprising, therefore, that although dinosaur fossils had been dug up by geologists and excavators for centuries, it was not until 1824 when the first dinosaur was scientifically named.

This was the 25-30-ft-long carnivorous theropod Megalosaurus ('big lizard'), a saurischian or lizard-hipped dinosaur, by Oxford University's Professor of Mineralogy and Geology, the Reverend William Buckland, based upon fossil remains unearthed in Oxfordshire, and originally thought to indicate a creature measuring around 40 ft long. A year later saw the naming of a second dinosaur form, the herbivorous 30-40-ft ornithopod Iguanodon, based upon remains found in the Tilgate Forest area of West Sussex by English palaeontologist Gideon Mantell and initially deemed by him to have measured around 60 ft long. This was followed in 1833 by a third, Hylaeosaurus, a herbivorous spiny ankylosaur, originally thought to have been approximately 25 ft long but nowadays downsized to around 10-13 ft. Its remains had been exposed after an explosion had demolished a quarry face not far from where Mantell's Iguanodon remains had been obtained. Both of these latter forms are ornithischian or bird-hipped dinosaurs, and both were named by Mantell.

Professor Sir Richard Owen (public domain)

Professor Sir Richard Owen (public domain)

When ideas were being sought for subjects to be represented in the new Crystal Palace Park, the suggestion of constructing life-sized representations of extinct animals was put forward, although there is still some controversy as to its originator. However, Queen Victoria's enterprising consort Prince Albert (already responsible for the Great Exhibition itself), Britain's foremost zoologist and palaeontologist of the day, Prof. Sir Richard Owen (1804-1892), and the Crystal Palace's designer, Sir Joseph Paxton, were all probably involved. Once this notion had been formally accepted, in September 1852, Hawkins was duly commissioned by the Crystal Palace Company to construct these statues, using concrete, brick, lead, and steel.

Initially, the plan was to concentrate upon prehistoric mammals, with thoughts of reconstructing mastodonts, mammoths, and other furry wonders from the distant past. But once Hawkins had read some of Owen's publications, it wasn't long before the prospect of also reconstructing dinosaurs reared its reptilian head. At that time, only the above-named trio of dinosaurs had been formally recognized, so Hawkins decided to recreate all three of them with life-sized sculptures to show what they may have looked like in life. Moreover, as his work progressed, the scheme was expanded still further to include reconstructions of quite a number of other archaic beasts too.

'The 'Crystal Palace' from The Great Exhibition', an engraving by George Baxter, after 1854 (Wellcome Images-Wikipedia –

CC BY4.0 licence

)

'The 'Crystal Palace' from The Great Exhibition', an engraving by George Baxter, after 1854 (Wellcome Images-Wikipedia –

CC BY4.0 licence

)

Indeed, by the end of the project, no fewer than 33 statues representing 20 different animal species had been produced (together with some reconstructions of fossil plants too, such as cycads), yielding a major attraction dubbed Dinosaur Court (aka Dinosaur Park), which encompassed three specially-created islands within a large artificial lake, situated near the southern end of Crystal Palace Park itself. Although the idea was to focus upon such creatures that had once existed in Britain, some non-native examples were also represented, Hawkins having utilised fossil remains from Holland when reconstructing the mosasaur, for instance, from South Africa for Dicynodon, and from South America for Megatherium.

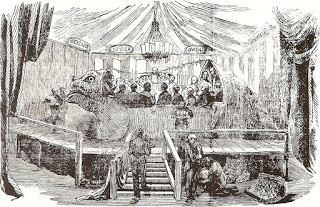

This unique project was nearing completion by the end of 1853, so to mark with suitable panache its impending official opening, a lavish banquet given by Hawkins was held on 31 December, New Year's Eve, of that same year, at which 21 notable dignitaries invited by him attended, including Owen and world-renowned bird painter John Gould. And the setting for this celebration? None other than inside Hawkins's colossal hollow mould for the construction of his standing Iguanodon statue! Never before, and probably never again, would such an event take place quite literally inside the bowels of a Mesozoic mega-beast!

Banquet inside the mould of Hawkins's Crystal Palace Iguanodon statue, New Year's Eve 1853 (public domain)

Banquet inside the mould of Hawkins's Crystal Palace Iguanodon statue, New Year's Eve 1853 (public domain)

Just over 5 months later, on 10 June 1854, Crystal Palace Park was formally opened by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Furthermore, no fewer than 40,000 visitors were in attendance, anxious to see what the media were enthusiastically referring to as an incredible assemblage of antediluvian monsters, i.e. labeling them as giant creatures that were believed by Creationists and other religious figures from that time to have existed on Earth during its earliest age before being wiped out by the Great Flood.

Although initially proving very popular, the Crystal Palace Park's Dinosaur Court eventually fell out of favour, especially once continuing palaeontological discoveries revealed that most of its reconstructions were actually very inaccurate. Neglected, especially after the Crystal Palace's destruction by fire in 1936, the statues eventually became partially hidden amid an overgrowth of undergrowth, and suffered considerably from damage caused not only by external, environmental influences but also by vandalism. Happily, following a first major restoration project in 1952, the historical significance of Hawkins's creations as a pioneering palaeontological venture was belatedly recognized, and in 1973 they were officially classed as National Heritage Grade II Listed Monuments, upgraded to Grade I in 2007. Meanwhile, an extensive second restoration project had taken place in 2002, recreating their dignified former appearance, making many repairs to their crumbling forms, and overseen by the London Borough of Bromley, the landowner of Crystal Palace Park.

Indigo Iguanodons in 1995, before the 2002 restoration, showing their previous countershaded paint scheme with white undersides (public domain)

Indigo Iguanodons in 1995, before the 2002 restoration, showing their previous countershaded paint scheme with white undersides (public domain)

Intriguingly, I'd long heard rumours that during the 1970s and possibly beyond, some of these statues were painted in bright garish colours. Only recently, however, have I uncovered some notable details concerning this hitherto scarcely-documented chapter in their long-running saga.

For example: during their 'painted period', the standing Iguanodonstatue was initially rendered a deep olive green with contrasting white underparts and golden jaw edges, but by the late 1970s both Iguanodon statues were dark indigo blue dorsally, pure white ventrally (although their throat region began as a flushed pink shade, subsequently fading to white). They still sported this colour scheme during the 1990s (as confirmed by some early 1990s videos and mid-1990s photos of them), whereas in still later photos they are a pale mint green. In addition, Mandy Holloway, Curator of Fossil Reptiles, Amphibians, and Birds at London's Natural History Museum at that time, has shown me a photograph snapped by her of the left-hand side of the Megalosaurus(nowadays uniformly grey all over) that reveals the presence of a thick red horizontal stripe running along its lower flank, and striations of the same shade upon its limbs.

Crystal Palace's Iguanodons when mint-green in colour (© CGPGrey/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Crystal Palace's Iguanodons when mint-green in colour (© CGPGrey/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

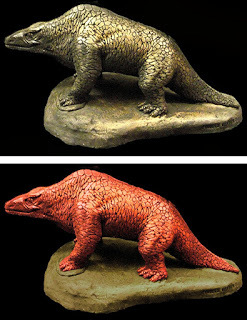

Moreover, the charity organization Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs (FOCPD – click here to access their fascinating and very worthy website) kindly alerted me to a music video from 1977 currently accessible online (click hereto view it) that features the late singer Lena Zavaroni boating past these dinosaur statues while singing the song 'I Had A Brontosaurus', in which the Megalosaurus is almost entirely bright red. I'd initially assumed that this vivid colouration was simply a special-effect created for the video, but Mandy confirmed that it was genuine – the Megalosaurus having been painted red on the instructions of the now long-defunct Greater London Council (GLC), which was also responsible for painting the other statues in Dinosaur Court that were brightly coloured during that period. Apparently, the reason for doing so was to make the statues appealing to young visitors, as a children's zoo had also been set up there, on Tertiary Island.

Correspondent Sam Crehan has shown me a full-colour photo of the Megalosaurusstatue during its red phase that appears in the little children's book I-Spy Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals, and which reveals that its underparts (not very visible in the Lena Zavaroni music video) were white. (I suspect that the statue's red colour in the video, so bright that it virtually glows, has been enhanced, to make it more visible against its dark, shadowy background.)

From I-Spy Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals as scanned by Sam Crehan, a full-colour photo of the Megalosaurus statue during its red phase (© Faber & Faber/I-Spy Ltd/Michelin – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

From I-Spy Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals as scanned by Sam Crehan, a full-colour photo of the Megalosaurus statue during its red phase (© Faber & Faber/I-Spy Ltd/Michelin – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

In January 2021, Crystal Palace Dinosaurs devotee Anthony Hawkins posted on FOCPD's Facebook page a photo of the Megalosaurus when red with white underparts that dated from December 1980. And a similar photo from 1979 was an entry in the 2016 Arles Festival of Photography, Rencontre d'Arles, a premier event for photographic art.

Finally, Canadian cryptozoological friend Sebastian Wang has drawn my attention to the official website of Palaeoplushies, a manufacturer of plush toys, which includes in its list of products not one but two versions of the Crystal Palace Megalosaurus– identical in shape and size, but very different in colour. For whereas one is grey, the other is red. In its official description of these two Megalosaurus versions, Palaeoplushies refers to the grey one as ""Classic Grey" – The current weathered grey concrete look", and to the red one as ""70s red" – The look this statue had during the 70s" (click hereto view and/or purchase these Megalosaurusplushies on the Palaeoplushies website). In short, Megalosaurus really was red in colour during the 1970s and at least as recently as the early 1980s too. This in turn means that Mandy's photo of it sporting just a horizontal red flank stripe and some red leg markings was snapped at a time when most of its red paint had been removed or painted over, or had simply faded away (red and yellow pigments are very prone to fading when exposed to sunlight).

My resin model of the Crystal Palace Megalosaurusstatue – my model's original golden-scaled form (top) and digitally recoloured to show what the statue would have looked like during its red-painted period (bottom) (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My resin model of the Crystal Palace Megalosaurusstatue – my model's original golden-scaled form (top) and digitally recoloured to show what the statue would have looked like during its red-painted period (bottom) (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Dinosaur Court's prehistoric creatures were originally located upon, and also within the waters surrounding, three artificial islands (named Tertiary, Secondary, and Primary), and most of these statues are still there today. The general public can walk around the islands (but not as yet directly upon them, except during special annual Open Days) via a railed public footpath on the Court's mainland portion, which affords excellent views of all of the statues. The islands are arranged in geological order, with their respective creatures dating from the Cenozoic Era back as far as the Permian Period of the late Palaeozoic Era. However, the Mesozoic Era is the Court's principal focus, because that is when most of the archaic beasts represented here existed, during the Age of Reptiles, as this era is commonly termed.

After arriving inside Crystal Palace Park's Dinosaur Court, if we begin our journey through geological time with the most recent creatures represented here, as I did, the first of Hawkins's statues encountered are four different mammals from the Cenozoic Era. These were formerly present on Tertiary Island, but except for the ground sloth they have now been relocated on the nearby mainland.

Anoplotherium

herd in Crystal Palace Park's Dinosaur Court (© Simon/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Anoplotherium

herd in Crystal Palace Park's Dinosaur Court (© Simon/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

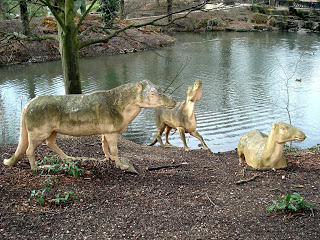

One of these mammals is Anoplotherium, represented by a small herd of three statues when I visited and photographed them in 2010 (yet some sources claim that only two exist). It was a primitive artiodactyl ungulate (even-toed hoofed mammal) from the late Eocene and early Oligocene Epochs (c.37-33 million years ago).

Anoplotherium is nowadays thought to be related to camels and llamas, and which Hawkins did provide with a camel-like head and neck. Its fossil remains have been found widely across Europe, including Hampshire and the Isle of Wight in the UK.

Anoplotherium herd seen from the opposite side, Crystal Palace (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Anoplotherium herd seen from the opposite side, Crystal Palace (© Dr Karl Shuker) Also represented here is Palaeotherium, another primitive hoofed mammal, in existence at much the same time as Anoplotherium and whose remains have again been found in Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. Unlike Anoplotherium, however, Palaeotherium was a perissodactyl (odd-toed) ungulate. Originally there were three statues of it, but the largest one mysteriously vanished sometime after the late 1950s and has never been seen again.

Hawkins followed the opinion of eminent French zoologist Baron Georges Cuvier concerning the likely appearance of Palaeotherium in life, reconstructing it to resemble those modern-day perissodactyls the tapirs. Today, conversely, palaeontologists generally depict it as a perissodactylian parallel to the artiodactylian giraffe's shorter-necked forest relative, the okapi.

One of Hawkins's Crystal Palace Palaeotheriumstatues (© Dr Karl Shuker)

One of Hawkins's Crystal Palace Palaeotheriumstatues (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My favourite Hawkins mammals are his very imposing giant deer or Irish elks Megaloceros giganteus, consisting of two antlered adult stags standing regally and an antler-lacking adult doe reposing with her fawn close by. Even today, these statues still correspond well with palaeontological thoughts regarding their likely appearance. This is because Hawkins based them upon living modern-day deer.

In addition, for his stag statues' antlers he utilized actual complete fossils of the famously magnificent antlers borne by this species' stags, but in subsequent years these real fossil antlers were replaced by replicas. Their remains have been found not only in Ireland but also on the Eurasian mainland, including as far east as Siberian Russia. Some have been dated to as recently as the early Holocene, 8000 years ago.

Giant deer aka Irish elks Megaloceros giganteusat Crystal Palace Park (© Neil Cummings/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Giant deer aka Irish elks Megaloceros giganteusat Crystal Palace Park (© Neil Cummings/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Finally, a suitably huge Pliocene/Pleistocene Megatherium or giant ground sloth from Argentina squats upright on its haunches, grasping a tall tree. However, it sports a short trunk-like proboscis that is no longer thought to have been a valid feature of this creature.

Over the course of many years following the sloth's installation at Dinosaur Court in 1854, the girth of the tree that it is grasping grew so wide that it broke the sloth's left forearm, which needed to be restored. And at the time of my visit in 2010, its right paw was missing.

Front and side views of the Megatheriumstatue in 2010, clearly revealing that its right front paw was missing at that time (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Front and side views of the Megatheriumstatue in 2010, clearly revealing that its right front paw was missing at that time (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Also worth noting is that at one stage during its long and distinguished existence, this very spectacular statue shared its location with the afore-mentioned children's zoo. That must surely be the only example of such a zoo to contain a giant ground sloth in its midst!

Moreover, although this Crystal Palace example is the first Megatheriumstatue to have been attempted by Hawkins, in subsequent years its gigantic species would again be an inspiration to him when designing a second major exhibit, as will be revealed later here.

19th-Century engraving of the Crystal Palace Megatherium, depicting it when its right front paw was still intact (public domain)

19th-Century engraving of the Crystal Palace Megatherium, depicting it when its right front paw was still intact (public domain)

Memorable though these bygone mammals are, it will come as no surprise to learn, however, that the most popular portion of Dinosaur Court is the next island to which the mainland public footpath now leads, Secondary Island. For this contains Hawkins's most famous creations – his Mesozoic dinosaurs and pterosaurs. Moreover, on its shore and also in the adjacent waters of Dinosaur Court's lake are Mesozoic plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, sea crocodilians, and a mosasaur.

So that is where our virtual tour of Crystal Palace's Lost World will be taking us tomorrow, in Part 2 of this ShukerNature blog article – back in time to the astonishing Age of Reptiles. Don't miss it!

My mother Mary Shuker and the Megatheriumstatue at Crystal Palace Park on 22 April 2010 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My mother Mary Shuker and the Megatheriumstatue at Crystal Palace Park on 22 April 2010 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

June 17, 2021

WAS A POTENTIAL SOURCE OF NESSIE DNA PROPELLED INTO OBLIVION?

The Story of the Loch Ness Monster

(1973), by Tim Dinsdale – the very first book devoted entirely to Nessie that I ever read and owned – and I still own it today (© Tim Dinsdale/Target Publishers – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

The Story of the Loch Ness Monster

(1973), by Tim Dinsdale – the very first book devoted entirely to Nessie that I ever read and owned – and I still own it today (© Tim Dinsdale/Target Publishers – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only) Sceptics regularly dismiss the Loch Ness Monster (LNM) on the grounds that there is no tangible, physical evidence for such a creature's existence, evidence that could be subjected to formal scientific examination in order to determine its originator's taxonomic identity. On one very notable occasion, however, some such evidence was indeed obtained, nothing less, in fact, than sizeable samples of flesh from an apparent Nessie - only for them to be carelessly thrown away!

Here's what happened.

In 1978, a holiday cruiser owned by truck driver Stanley Roberts, rented out to a family that included an elderly grandfather, collided heavily with a substantial unknown object while sailing on Loch Ness near Urquhart Castle. As later recalled by Roberts in a Daily Record interview (click hereto read it in archived form online):

The propeller stopped turning. The family were very alarmed. The old man had a heart attack and seemed to have died. There was no radio on board so they let off distress flares to get a tow back to Fort Augustus. The grandfather was taken by ambulance to hospital where he was found to be dead.

Roberts was duly informed by the rental managers. However:

They simply told me there had been an accident. It was only later that I learned more - what had been found on the underside of the boat when they pulled it out of the water.

Urquhart Castle and Loch Ness, depicted on a vintage pre-1914 picture postcard (public domain)

Urquhart Castle and Loch Ness, depicted on a vintage pre-1914 picture postcard (public domain) Boatyard workers who examined the cruiser had found:

flesh and black skin an inch thick along the propshaft. [However,] the workers chiseled the flesh away and threw it into the Caledonian Canal. I said you stupid b-----s. It would have proved that Nessie was here.

Indeed it might. Certainly, to quote Adrian Shine of the Loch Ness Project when told of this incident:

Very frustrating. With modern DNA techniques we could have learned a lot about exactly what had caused the damage.

In fact, this was quite possibly the single greatest lost opportunity in the entire LNM history to conduct a direct scientific examination of Nessie, because there is no known animal species resident in the loch that is big enough to have caused such a collision.This ShukerNature blog article is excerpted from my book Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors.

Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors

(© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)

Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors

(© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)

May 30, 2021

UNFURLING CHINA'S FENG-HUANG – THE 'OTHER' PHOENIX

A multicoloured feng-huang figurine that I brought back home from Hong Kong in 2005 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

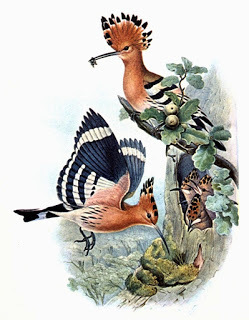

A multicoloured feng-huang figurine that I brought back home from Hong Kong in 2005 (© Dr Karl Shuker) One of the most famous legendary birds is the Egyptian phoenix, but traditional Chinese mythology has its very own equivalent of sorts – the 'other' phoenix, or, as it is commonly referred to in China, the feng-huang.

Just like the Egyptian phoenix, the feng-huang has been identified with a range of real birds. A very popular candidate is the familiar blue peacock Pavo cristatus (in depictions, the feng-huang's splendorous tail is frequently decorated with numerous ocelli or eyespots, thereby closely resembling the famously ornate train of this species).

A male blue peacock displaying its spectacular ocellated train, consisting of tail covert feathers (public domain)

A male blue peacock displaying its spectacular ocellated train, consisting of tail covert feathers (public domain)

A second candidate is Asia's crested argus pheasant Rheinardia ocellata, which is another large, exotic galliform species sporting eyespot-enhanced plumage.

In an earlier ShukerNature article (click here to read it), I revealed that there have been suggestions that Egypt's phoenix may have been based upon preserved skins of certain bird of paradise species brought back to Phoenicia from their far-off New Guinea homelands by early seagoing traders. Moreover, in 1967 a Chinese researcher postulated that one or more birds of paradise native to New Guinea may have been the basis for the feng-huang too.

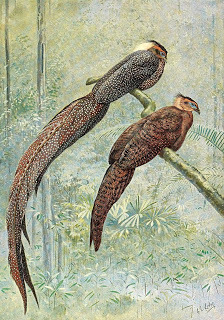

A pair of crested argus pheasants painted by George Edward Lodge, the larger specimen being the male (public domain)

A pair of crested argus pheasants painted by George Edward Lodge, the larger specimen being the male (public domain)

In a lengthy paper written principally in Chinese (and published by the Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology of Taipeh, Academia Sinica, during autumn 1967), Tzu-Chiang Chou based his assertion upon four primary points, summarized as follows:

1. According to Tzu-Chiang Chou, in the Chinese hieroglyphics of the Shang Dynasty (1384—1111 BC), the shape of the Chinese character termed ‘Feng’, denoting the phoenix, resembled the typical, effusively-plumed Paradisaea birds of paradise more closely than any other proposed contender for this fabulous bird’s identity.

2. The shape used for the character denoting the wind within this system of hieroglyphics was comparable to the Feng character, implying that the phoenix was in some way associated with the wind.

A sumptuous Chinese wall plaque in which a Chinese phoenix is portrayed in shimmering nacre or mother-of-pearl (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A sumptuous Chinese wall plaque in which a Chinese phoenix is portrayed in shimmering nacre or mother-of-pearl (© Dr Karl Shuker)

3. He offers many examples from ancient Chinese writings and from bird designs on the bronzewares of ancient China’s pre-Chin period (i.e. prior to 221 BC) that suggest a Paradisaea species as their model.

4. He presents material that he interprets as evidence for believing that as recently as 1100 AD (during the Sung Dynasty), southern China was home to two native species of bird of paradise, which have since become extinct.

From the examples of Shang Dynasty hieroglyphics depicting the ‘Feng’ and ‘Wind’ that Tzu-Chiang Chou provides, a certain, but by no means unequivocal, similarity to at least two different birds of paradise (greater, Paradisaea apoda, and king, Cicinnurus regius) is present, but his claim that a third example specifically comprises a depiction of a composite bird of paradise (created from the most striking characteristics of a wide range of different species) is less convincing. As for the wind connection, he points out that in Chinese the birds of paradise are referred to as ‘wind-birds’, because they fly against the wind.

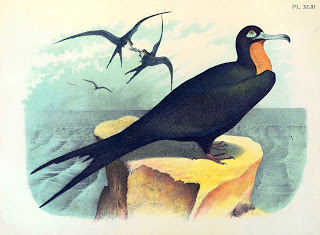

Chromolithograph from 1900 depicting a male greater bird of paradise (top) and a male king bird of paradise (bottom), plus a six-wired bird of paradise (centre) (public domain)

Chromolithograph from 1900 depicting a male greater bird of paradise (top) and a male king bird of paradise (bottom), plus a six-wired bird of paradise (centre) (public domain)

Within the ancient Chinese texts, the Chinese phoenix is described as having colourful plumage, long tufts of feathers sprouting from its flanks, a fondness for dancing, and communal behaviour – all features shared by the Paradisaea birds of paradise (whose males do display in groups rather than singly). Conversely, in more recent Chinese accounts a very different phoenix is described - a somewhat grotesque entity with a snake’s neck, a tortoise’s shell, and a fishtail – but Tzu-Chiang Chou believes that this image is wholly imaginary, not based upon observations of real forms.

So far, then, Tzu-Chiang Chou’s evidence for the identification of the Chinese phoenix as a Paradisaea bird of paradise is quite persuasive, but his fourth point is much more contentious. Quoting from various early Chinese encyclopedias, he provides descriptions of two exceptionally handsome birds supposedly native to China in those long-departed days, at least according to the authors of the descriptions.

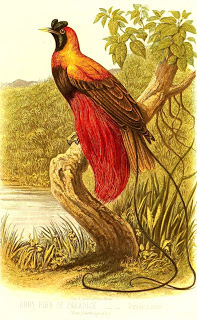

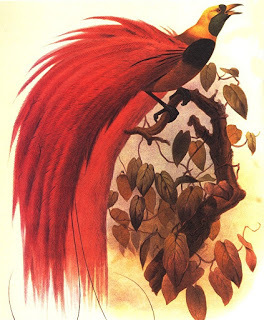

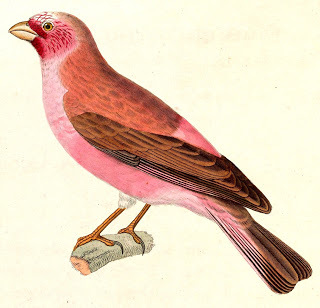

Male red bird of paradise, in Cassell's Book of Birds, 1870s (public domain)

Male red bird of paradise, in Cassell's Book of Birds, 1870s (public domain)

One bird, allegedly inhabiting Canton Province during the Sung Dynasty, referred to by the natives as the feng-huang, and said to have long sashes of red plumes on its flanks, beneath its wings, is identified by Tzu-Chiang Chou as the red bird of paradise Paradisaea rubra. This species is officially known only from the Western Papuan islands of Saonet, Waigeu, and Batanta (and perhaps Ghemien too).

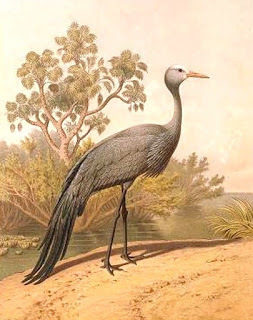

The other mystery bird, reported from Kwangsi Province, again during the Sung Dynasty, and called the u-feng or black phoenix, was reputedly bluish-green and purple, with a head crest and an elongated tail with bunches of feathers at each end. Tzu-Chiang Chou considers this to be the long-tailed (=black) sicklebill bird of paradise Epimachus fastosus (formerly magnus).

Two males and one female of the long-tailed sicklebill bird of paradise, painted by Richard Bowdler Sharpe (public domain)

Two males and one female of the long-tailed sicklebill bird of paradise, painted by Richard Bowdler Sharpe (public domain)

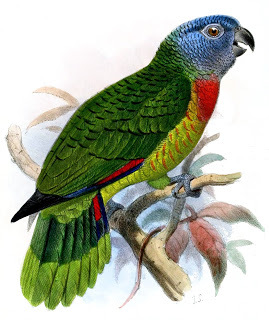

These identifications, however, are far from precise. Goldie’s bird of paradise Paradisaea decora and Count Raggi’s P. raggiana also have sprays of long red plumes emerging from their flanks beneath their wings; and the sicklebills do not have crests – the equally long-tailed species of astrapia do, but (in common with the sicklebills) they do not have bunches of feathers at each end of their tails. In any event, I consider it highly unlikely that any genuine birds of paradise have ever been native to China, even if we accept Tzu-Chiang Chou’s claim that in earlier days its climate was much warmer, and hence closer to the tropical temperatures of New Guinea.

Ornithological experts believe that the birds of paradise originated in the mid-mountain forests of New Guinea, and as the present diversity of species progressively evolved, the family’s range gradually expanded, infiltrating north-eastern Australia as its distribution’s southernmost limit and extending as far to the west as the Moluccas (home to Wallace’s standardwing Semioptera wallacei and the paradise crow Lycocorax pyrrhopterus).

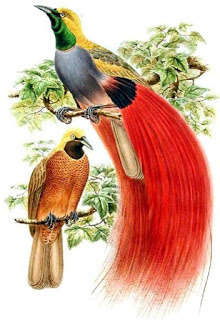

Richard Bowdler Sharpe's 1890s painting of a pair of Goldie's bird of paradise (public domain)

Richard Bowdler Sharpe's 1890s painting of a pair of Goldie's bird of paradise (public domain)

It is reasonable to suppose, therefore, that if the family were to send representatives beyond the Moluccas, ultimately reaching southern China, it would do so either via the Philippines, a handy series of stepping stones to the Asian mainland and thence China, or via a longer Sulawesi-Borneo-Vietnam course. Yet there is no evidence for the former existence of birds of paradise in any of these countries, thereby undermining support for their onetime occurrence further north-west, in China itself.

A far more likely option is that early travellers visiting New Guinea arrived at China with preserved bird of paradise skins, and perhaps even some live specimens, whose outstanding appearance would guarantee their documentation in major Chinese texts of the day – their authors probably being unaware that these birds had originated from beyond China.

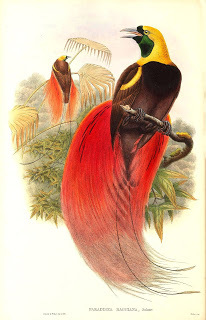

John Gould's painting of two adult male specimens of Count Raggi's bird of paradise (public domain)

John Gould's painting of two adult male specimens of Count Raggi's bird of paradise (public domain)

Another legendary Chinese bird that may conceivably have been inspired at least in part by bird of paradise skins or specimens is the vermilion bird. Totally distinct from the feng-huang, this noble and elegant bird is a mythological spirit creature, one of the four symbols of the Chinese constellations. Representing the south of China and the summer season, it is very selective where it perches and what it eats, and its gorgeous plumage incorporates many different hues of reddish orange.

Sadly, however, like so much in cryptozoology, all of this is mere speculation, nothing but unconfirmed conjecture at present, especially as illustrations can be notoriously inaccurate or so stylized that the true morphological appearance of their original subjects remains obscure.

A Chinese phoenix exquisitely depicted by Katsushika Hokusai in c.1835 (public domain)

A Chinese phoenix exquisitely depicted by Katsushika Hokusai in c.1835 (public domain)

This ShukerNature blog article was adapted from a section in my book Extraordinary Animals Revisited.

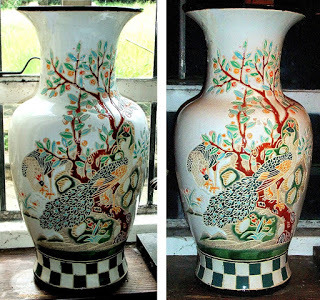

A large, modern-day, Chinese-style vase very handsomely decorated with a pair of traditionally-depicted feng-huang birds, photographed in daylight (on left) and at night (on right) (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A large, modern-day, Chinese-style vase very handsomely decorated with a pair of traditionally-depicted feng-huang birds, photographed in daylight (on left) and at night (on right) (© Dr Karl Shuker)

May 8, 2021

LEAST WEASELS, CANE WEASELS, WHITNICKS, AND DANDY DOGS - DEMYSTIFYING MUSTELIDS IS THE NAME OF THE GAME!

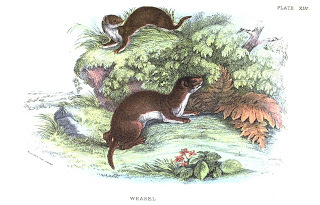

Exquisite 19th-Century colour-tinted engraving depicting a pair of Mustela nivalis, the common weasel, or – to avoid being labelled by pedants as nomenclaturally negligent – the least weasel (public domain)

Exquisite 19th-Century colour-tinted engraving depicting a pair of Mustela nivalis, the common weasel, or – to avoid being labelled by pedants as nomenclaturally negligent – the least weasel (public domain) Back in the mid-1960s, when I was just a small child, I was bought an alphabetically-arranged weekly partwork entitled Purnell's Encyclopaedia of Animal Lifethat ran for 96 weeks and which when complete yielded six hefty and exceedingly comprehensive full-colour volumes. Edited by famous British zoologists Drs Maurice and Robert Burton, these red-bound fact-filled, photo-brimming tomes totally enthralled me, and I read them over and over again. Moreover, I still own them today and they remain an extremely useful, informative source of reference. Indeed, it is perfectly true to say that this wonderful publication quite simply transformed my life as a budding zoologist, unveiling a vast array of extraordinary animals that were totally new to me. Crucially, it was also the very first zoological publication owned by me that included the taxonomic binomial names of the animals documented in its countless pages. (These binomial names, which trace their origin back to Linnaeus's revolutionary system of wildlife classification back in the 1700s, are commonly referred to colloquially as 'Latin names', even though many are derived from Greek rather than Latin.) As a result, I have been fascinated with zoological nomenclature and taxonomy ever since.

And so it was that while others of my age were memorizing football teams and car makes/models, I was enthusiastically learning the binomial names of as many animals as my besieged brain cells could accommodate, and then some, and I have continued to do so ever since. However, just like every other aspect of science, zoological nomenclature and taxonomy are ever changing, ever expanding, ever modifying as new information concerning the evolutionary origins and relationships of species and other taxa continues to emerge. Consequently, it should come as no surprise that many of the binomials and classifications of animals that I diligently learned six decades ago have since changed or transformed dramatically – but also sometimes confusingly – meaning that I am perpetually engaged in taxonomic catch-up, often having to abandon binomials that I've fondly recollected for countless years in favour of new, unfamiliar ones.

Sadly, these include the very first binomial that I ever learned, from my trusty Purnell's Encyclopaedia. It was Alopex lagopus, the Arctic fox, which has stayed with me ever since, never forgotten, a faithful reminder of where my enduring passion for such nomenclature began. And then, to my horror, some wretched wrecker of childhood memories in taxonomist form came along (albeit a fair few years ago now), and decided that the Arctic fox did not warrant its own genus, Alopex, distinct from Vulpes, which houses the true foxes, and should therefore be subsumed into their genus. Consequently, to my horror, the first binomial that I had ever leant was no more! Suddenly, "Alopex lagopus the Arctic fox" – the much-loved taxonomic mantra that had chanted happily away to itself in the backrooms of my memory for decades – had been rendered obsolete, jettisoned to nomenclatural obscurity as nothing more from now on than a synonym of Vulpes lagopus. The dread deed was done, and it is now this latter binomial that is recognized as the Arctic fox's official one – but although I outwardly accept it and grudgingly use it when writing about this species, inside my mind the Arctic fox is and always will be Alopex lagopus. So be it, forever and ever, amen.

Resplendent in its all-white winter coat, the Arctic fox – forever Alopex lagopus to me! (public domain)

Resplendent in its all-white winter coat, the Arctic fox – forever Alopex lagopus to me! (public domain)

I mentioned earlier here that sometimes the changing of taxonomic names and classifications can be a source of confusion, which is where this ShukerNature blog article's mustelid theme now kicks in and is the reason for my prefacing it with an explanation of how and why binomials have always interested me.

Back when I was a child, most of the wildlife books that I owned readily differentiated three very small species within the genus Mustela. These were referred to as the common weasel (or simply as the weasel) M. nivalis (with a head-and-body length of 5-10 in and a tail length of 0.5-3.5 in, native to much of continental Europe as well as Great Britain but not Ireland), the pygmy weasel M. pygmaea (given as being smaller than M. nivalis, and native to Fareastern Russia, Siberia, and Mongolia), and the least weasel M. rixosa (given as being even smaller than M. pygmaea, native to Canada and parts of the northern USA, and listed back then in the Guinness Book of Records as not only the world's smallest species of mustelid but also its smallest species of any type of carnivoran, i.e. belonging to the taxonomic order Carnivora). So far, so simple – but then it all changed…

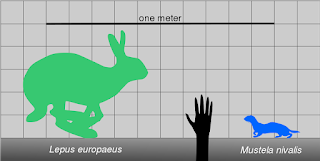

Size comparison of Mustela nivalis with the European hare Lepus europaeus and a human hand (public domain)

Size comparison of Mustela nivalis with the European hare Lepus europaeus and a human hand (public domain)

Many years later, I started noticing in books and articles that M. nivaliswas now being referred to as the least weasel and being claimed to be the world's smallest mustelid and carnivoran. So what had happened to M. rixosa (and also M. pygmaea, for that matter)? This name-change was especially curious, given that the least weasel M. rixosa that I had grown up reading about was a wholly New World species whereas M. nivalis was a wholly Old World one. To quote the website NatureServe Explorer's 'Mustela nivalis Least Weasel' page as of today, 8 May 2021 (click hereto access the full page):

The North American population sometimes is treated as a separate species, Mustela rixosa. Confusion has existed for a long time regarding the taxonomic status of this species [M. nivalis] and its subspecies, particularly in Europe (see Sheffield and King 1994; Wozencraft, in Wilson and Reeder 2005).

How very true! Further research has revealed to me that generally, but by no means universally, taxonomists nowadays deem what used to be called the least weasel (i.e. the New World species M. rixosa) to be merely a subspecies of what used to be called the common weasel (or weasel) M. nivalis, thus renaming it M. n. rixosa, which is fair enough. However, they have also elected (for reasons that entirely escape me) to utilise the latter subspecies' original common name as the name for the entire species.

In other words, no longer is M. nivalis called the common weasel or weasel. Instead, it is now called the least weasel – which to my mind is a totally unnecessary and highly confusing name-change, especially for those like myself who have long known the least weasel to be the name of the New World's tiniest of tiny mustelids, but which is nowadays called Bangs' least weasel instead.

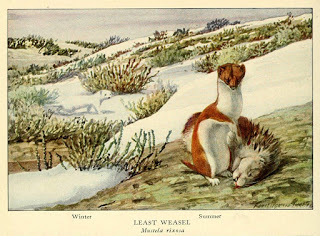

In summer and (white) winter coat, North America's least weasel M. (n.) rixosa (public domain)

In summer and (white) winter coat, North America's least weasel M. (n.) rixosa (public domain)

Moreover, the pygmy weasel M. pygmaea has been demoted to a subspecies of M. nivalis too. As a result, it has been renamed M. n. pygmaea, and is now called the Siberian least weasel instead of the pygmy weasel.

So instead of having a naming system for this trio of mustelids that was not only readily memorable by being succinct but also instantly conveyed useful information concerning them – 'common weasel', 'pygmy weasel', and 'least weasel' clearly revealing the sizes of these three forms relative to each other, self-evidently reducing in size from 'common' through 'pygmy' to 'least' – we now have one that is harder to remember and conveys no information whatsoever concerning their relative sizes. After all, how can we tell which is the biggest, the medium-sized, and the smallest from the names 'least weasel', 'Siberian least weasel', and 'Bangs' least weasel'? And there was I, thinking that the purpose of zoological nomenclature and taxonomy is to simplify animal classification and recognition!

[To make matters even more bewildering: by the 1970s, some authors had begun lumping together what until then had still been M. pygmaea from the Old World and M. rixosa from the New World, thereby creating what was now a circumpolar species. Very confusingly, however, instead of being given a new common name and a new taxonomic name (which would have made much more sense), this composite circumpolar species became referred by its New World component's names, i.e. as the least weasel M. rixosa. Also claimed as a separate species back then was the dwarf weasel M. minuta, smaller than the common weasel and native to parts of continental Europe but not the British Isles… but enough of taxonomic turmoil, time to move on, I think!]

Anyway, if even the scientific naming of creatures is far from immune to introducing confusion where only clarity should reign, how much more so when we turn our attention to local, non-scientific names, as exemplified once again by some ostensibly mystifying monikers of the mustelid variety.

Mustela nivalis

at the British Wildlife Centre, Surrey, England (© Kevin Law/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Mustela nivalis

at the British Wildlife Centre, Surrey, England (© Kevin Law/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

) Take, for instance, the so-called cane weasel. Also known variously as the miniver, mouse hound, or mousehunt, this cryptic carnivoran was once firmly believed in by many rural folk from southern England, who claimed that it was a discrete, second species of native weasel, one that was even smaller than M. nivalis. Gamekeepers vehemently attested to the reality of this minuscule mustelid, yet no specimens were ever submitted to museums or other scientific establishments for formal examination, and eventually this curious notion of a second British weasel species simply faded away. In a short but succinct 'Nature Note' article in London's Daily Telegraph newspaper for 6 January 1996, previously-mentioned British zoologist Dr Robert Burton offered three suggestions for the erstwhile belief in the cane weasel.

Firstly: M. nivalis is a noticeably variable species in terms of size, which is what had influenced the former taxonomic delineation of M. pygmaea and M. rixosaas separate species in the first place. Moreover, adult female specimens of M. nivalis can often be considerably smaller than adult males. Consequently, it would be easy for zoologically-untrained observers to spy smaller than average female specimens and wrongly assume that they must constitute a very diminutive separate species in their own right.

Secondly: M. nivalis produces two litters in a year. Consequently, it is possible that the so-called cane weasels are actually the tiny offspring of the first litter, which breed before they are full grown in size.

Thirdly: alternatively, it may be that the offspring of late-produced second litters of M. nivalis pass the winter at less than adult size and it is these overwintering under-sized specimens that have given rise to the cane weasel notion among rural observers.

Painting of a stoat Mustela erminea in its white ermine winter coat with two least weasels close by, readily revealing how much larger is the stoat – in Gerald Edwin Hamilton Barrett-Hamilton's book A History of British Mammals, Vol 5, 1910 (public domain)

Painting of a stoat Mustela erminea in its white ermine winter coat with two least weasels close by, readily revealing how much larger is the stoat – in Gerald Edwin Hamilton Barrett-Hamilton's book A History of British Mammals, Vol 5, 1910 (public domain)

Another English belief in a distinct, smaller than normal weasel species originates in the southwestern county of Cornwall, and concerns the so-called whitnick. According to Cornish language and dialect sources that I have consulted, generally speaking 'whitnick' is simply a local name for M. nivalis. However, on 31 March 1964, a short letter written by Cornish reader S.M. Lanyon that was published in the then-weekly, now long-defunct British magazine Animals enquired whether the whitnick may be something much more interesting and special.

In his letter, Lanyon, based in St Ives, Cornwall, stated that the whitnick is claimed locally to be a cross between a weasel and a stoat, to be plentiful around there, and to have always been so. But was such a creature real, or just a Cornish story, Lanyon wondered. Back then, the editor of Animals was none other than the highly-acclaimed naturalist and pioneering wildlife film maker Armand Denis, who responded personally to Lanyon's letter, Denis's reply being published directly underneath it.

Like Burton would mention many years later in his own above-noted Daily Telegraph article, Denis referred first of all to the noticeable size disparity between the two sexes in M. nivalis (i.e. females being smaller than males). He then speculated that whereas 'cane weasel' appeared to be a special name given to the smaller, female sex of M. nivalis in Kent and Sussex, in Cornwall it was the larger, male sex of this same species that had been given a special name – whitnick – because the possibility that this cryptic creature was genuinely a hybrid of M. nivalis and the much bigger M. erminea seemed highly unlikely. And indeed, I have never uncovered any information concerning verified crossbreeds of these two species, despite having searched diligently during the many years that have passed since I first read Lanyon's letter and Denis's reply to it.

Atmospheric colour-tinted 19th-Century engraving of Herne the Hunter with two of his hounds (public domain)

Atmospheric colour-tinted 19th-Century engraving of Herne the Hunter with two of his hounds (public domain)

Finally: many years ago once again, I discovered this last snippet of unexpected information relating to weasels and weasel nomenclature in an equally unexpected source. Namely, Africa-based naturalist Peter Turnbull-Kemp's book The Leopard(1967), which I consulted when researching my own, very first book, Mystery Cats of the World (1989) – now republished in expanded, updated form as Mystery Cats of the World Revisited (2020). Here is the snippet in question, in which Turnbull-Kemp recalled an interesting memory from his childhood spent in England:

I myself can remember being warned as a boy against the risks in meeting supposed troops or packs of "bloodthirsty" weasels – known in my part of England by the rather attractive name of Dandy-hounds. Such "dangerous packs were only in evidence in times of extremely hard weather, and rare parties of weasels did in fact appear on rare occasions under such conditions. Needless to say, they were sometimes bold from hunger and possibly with curiosity, but utterly harmless.