Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 66

July 25, 2025

[Ilya Somin] My Jotwell Review of Michael Ramsey's "The Originalist Case Against the Insular Cases"

[The article makes a compelling argument that has broader implications.]

My just-published Jotwell review focuses on Michael Ramsey's important new article,, "The Originalist Case Against the Insular Cases." Here is an excerpt:

In the Insular Cases of the early twentieth century, the Supreme Court ruled that much of the Constitution does not apply to America's "unincorporated" overseas territories, such as Puerto Rico and other territories acquired as a result of the Spanish-American War of 1898. Thus, the federal government could rule the people there without being constrained by a variety of constitutional rights. Only "fundamental" rights were held to constrain the federal government's powers over the inhabitants of these territories, while other constitutional constraints on federal power did not apply. In a 2022 concurring opinion, Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch urged the Court to overrule these decisions. Prominent originalist legal scholar Michael Ramsey's important new article explains why Gorsuch was right.

Ramsey compellingly demonstrates that the Insular Cases were wrongly decided, at least from an originalist standpoint. And his argument has potential implications that go beyond the status of people living in "unincorporated" territories. There have been various previous critiques of the Insular Cases. But Ramsey's is the first systematic scholarly dismantling undertaken from an originalist perspective.

The unincorporated territories currently include American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, plus some minor islands….

In a detailed examination of the text and original meaning of the Constitution's Territories Clause and other relevant provisions, Ramsey shows that "under the Territory Clause, Congress's power over U.S. territory [outside the states] is very broad, essentially amounting to a general police power." But he argues persuasively that "the grant to Congress of general police power in territories does not suggest that Congress is thereby freed of other specific limitations on Congress's power arising from the Constitution's structural and individual rights provisions…."

Ramsey also demonstrates that this conclusion is consistent with federal policy and Supreme Court precedent of the pre-Civil War era. The tradition was continued in the initial aftermath of the Reconstruction Amendments. For example, it was generally understood that children born in federal territories were entitled to birthright citizenship.

That longstanding body of precedent was undercut by the Insular Cases as a result of the racism and imperialism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries…

The Insular Cases are not the only important nonoriginalist, atextual abrogations of constitutional rights blessed by the Supreme Court as a result of late-19th century racial bigotry. The same is true of the "plenary power" doctrine, which exempts immigration restrictions from many of the constitutional constraints that apply to all other exercises of federal power. While later decisions have called elements of this doctrine into question, enough remains that it is not completely clear whether, for example, the government can deport immigrants for speech protected by the First Amendment….

Even if completely invalidating federal immigration restrictions entirely would be too great a break with precedent, federal courts would at least do well to rule that such restrictions are subject to the same individual rights and structural constraints as all other legislative powers…

The post My Jotwell Review of Michael Ramsey's "The Originalist Case Against the Insular Cases" appeared first on Reason.com.

[John Ross] Short Circuit: An inexhaustive weekly compendium of rulings from the federal courts of appeal

[A sovereign See, a safehouse, and an infinite number of pronouns.]

Please enjoy the latest edition of Short Circuit, a weekly feature written by a bunch of people at the Institute for Justice.

CA7 friends: The Short Circuit team is heading to downtown Chicago on Sunday, August 17 for a live recording of the podcast on the eve of the Seventh Circuit Judicial Conference. Come watch Sarah Konsky of UChicago Law and Christopher Keleher of Keleher Appellate Law hash things out with us. Click here to learn more.

New on the Short Circuit podcast: Steve Lehto provides a free diagnostic on license-plate-holder law.

We can neither confirm nor deny whether six federal agencies properly used Glomar non-responses about the existence of certain documents in response to FOIA requests. But we will say there seems to be no shredding of national security as an excuse for inaction in this D.C. Circuit opinion.The Stored Communications Act allows the government to subpoena social-media companies for user data, and it even allows those subpoenas to be kept secret from the user—but only if a court determines that certain statutory conditions justifying secrecy are met. The government: So when we subpoena X in this investigation, can we just be the ones to decide which subpoenas are secret instead of the court? D.D.C.: Okay. D.C. Circuit: Not okay.Starbucks baristas seek to decertify their union. When the NLRB refuses to grant their petition, the baristas sue, alleging that the NLRB's tenure protections are unconstitutional. NLRB: You know what, we agree. D.C. Circuit: And since you both agree, there's nothing for us to adjudicate and no standing.After the FBI raids a private safe-deposit company without probable cause to search the contents of the individual boxes, the FBI searches the boxes anyway and tries to forfeit the contents. Much meritorious litigation ensues, and the Ninth Circuit says that this is very bad. In another case, an innocent box holder brings a putative class challenge to the FBI's practice of issuing threadbare forfeiture notices that don't tell property owners what the supposed crime is. The government promptly moots her individual case by returning the $40k it took from her. D.C. Circuit: And because there was no proper appeal of the denial of class certification, the rest of the case is over too. (Ed. note: The lawyers on this case are still handsome and good.) (2d ed. note: This is an IJ case.)This sad D.C. Circuit case about child slavery on cocoa farms in Côte d'Ivoire holds that the child plaintiffs didn't plead a plausible connection to defendants like Hershey and Mars. "The Plaintiffs in this case deserve the greatest sympathy, and the people who took away their childhoods deserve the greatest condemnation." But no causation is still no causation.Did you know that, since 1922, baseball—alone among sports—has been exempt from federal antitrust laws, without any basis in statutory text? This was last reaffirmed in a 1972 Supreme Court decision, where two concurring justices took the unusual step of refusing to join the opening facts section of the opinion because Justice Blackmun's paean to America's pastime was so over-the-top. Anyway, the First Circuit says that antitrust exemption also holds in Puerto Rico—although territorial antitrust laws may nevertheless apply because there's no interstate dimension to the purely local Puerto Rican baseball league.Jury finds a Massachusetts man is liable for human-rights violations when he was previously the despotic mayor of a town in Haiti. First Circuit: But the district court needs to consider anew whether Congress did—or even could—create a cause of action in the Torture Victim Protection Act to sue for torture and extrajudicial killings if they occur abroad solely among foreign nationals. Also, that statute doesn't cover attempted extrajudicial killings.In which the Second Circuit issues a blockbuster ruling ordering the release of the Epstein files! (Not, to be clear, the Epstein files that have been in the news all week. Just some, but not all, of the filings in a defamation lawsuit against Epstein associate Ghislaine Maxwell. But still, that first sentence was exciting for a minute there, wasn't it?)New York boy disappears in 1979. Over 30 years later, a man with low IQ and a long history of mental illness and hallucinations is prosecuted for murder and kidnapping based on his confession—which occurred only after many hours of interrogations and before Miranda warnings, but which he repeated after being Mirandized. One jury hangs, and another convicts only after several notes inquiring about the voluntariness of the confessions. New York state courts: No constitutional problem, and any error was harmless. Second Circuit: There's a Supreme Court case directly on point saying police can't do this confession-Mirandize-repeat maneuver. Habeas granted.American victims of terrorist attacks in Afghanistan sue foreign banks for aiding and abetting terrorism, alleging that the banks facilitated money laundering and provided financial services to Pakistani fertilizer companies whose product was smuggled into Afghanistan and used to manufacture IEDs. Second Circuit: But the allegations don't show the banks knowingly and culpably aided and abetted the attacks. No leave to amend because "after filing two complaints together totaling over 1,200 pages" and no plan for fixing the complaint, the plaintiffs have exhausted the court's patience.Although the Pope no longer leads armies into battle, the Holy See is considered a sovereign nation. And thus has sovereign immunity in U.S. courts under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act. But not if the tortious activity exception applies. But not if the discretionary function exclusion to that exception applies. How does the Second Circuit figure out how any of this applies when alleged victims of abusive priests sue the See? By borrowing law from IJ's good buddy, the FTCA.In 2021, New Jersey passed a law banning the state, its local governments, and private parties from making, renewing, or extending any contract to detain people for civil immigration purposes. CoreCivic, operator of an immigrant detention center in New Jersey, challenges the ban as a violation of the Supremacy Clause. Third Circuit: More specifically the doctrine of "intergovernmental immunity." The feds are in charge of immigration, and states can't go making it impossible for them to contract for private detention facilities. Dissent: States can until Congress tells them they can't.Philly nonprofit called "Safehouse" wants to address opioid overdoses through providing a, well, safehouse, where people can more safely use drugs. The feds sue. Third Circuit (2021): That might violate the law. Safehouse: But what if we're religious about it? Third Circuit (2025): That might just work.Sex offender, incarcerated since 1986, refuses to complete a sex-offender program designed to reduce the likelihood of recidivism. As a result, he is repeatedly denied parole. He sues, alleging that prison officials violated due process by failing to give him a hearing before treating him as a sex offender and requiring him to participate in the sex-offender program to obtain parole. Sixth Circuit: For one thing, you are in prison for a sex offense. For another, parole is discretionary and nobody is stopping you from completing the program. Case dismissed.There is only one thing that Seventh Circuit Judge Frank Easterbrook could possibly enjoy more than drafting a merits opinion in a case involving antitrust law, the Rooker-Feldman doctrine, and Colorado River abstention: dismissing that same appeal for want of appellate jurisdiction.Schaumburg, Ill. passes a law changing how private fire alarm systems must handle an emergency. Rather than taking the calls first and connecting to the local dispatcher if emergency response is needed, the village now insists that an alarm notify the dispatcher directly. This saves the village a cool $300k per year via a credit from the dispatcher—and costs the private alarm companies all of their business in the village. An alarming Contracts Clause violation? Seventh Circuit: Not on this record, which leaves "much to the imagination."Man forces woman at gunpoint to drive him from Fargo, N.D. a few miles east, crossing the border, to Moorhead, Minn., where he tries (unsuccessfully) to get her to withdraw cash from an ATM, before she bolts and summons help. Man: The evidence showed only a robbery, not a distinct kidnapping, which you can tell by looking at this neat four-factor test from the Third Circuit. Eighth Circuit: Kidnapping conviction affirmed, and though we find that Third Circuit case interesting, no need to adopt it here. Concurrence: This is an easy one, and there's no need to add elements to the kidnapping statute like the Third Circuit did.Man is arrested for his part in a drug deal with the feds on the other side. Whoops. In addition to the pile of meth in the car meant for the deal, he also has a small bag of weed in his pocket. He admits to smoking a few times per day and to having a rifle at home that he'd used only once. Oh snap! Drug addicts can't possess guns. (You may have heard of this statute before.) Eighth Circuit: Smoking weed doesn't automatically blunt someone's Second Amendment right. On remand, the district court needs to determine if the man's marijuana use caused him to act like someone who is mentally ill and dangerous or made him pose a danger to others with his gun.Every four years, the FCC is required by law to assess whether its own rules limiting the number of TV and radio stations that someone can own are "necessary in the public interest as a result of competition." In December 2023, after years of delays and legal threats, the FCC decided that its rules are indeed in the public interest—one should be even more strict! Eighth Circuit: The FCC's review changed "almost nothing" and that's mostly fine, but its decision to keep one rule was arbitrary and capricious, and tightening another exceeded the FCC's authority.While working on a joint state-federal task force, a St. Paul officer lied to get a local teen arrested and the teen spent over two years in custody before charges were dropped. Prior Eighth Circuit decisions ruled out a Bivens remedy and held that § 1983 is off the table because the officer wasn't acting under color of state law. The plaintiff moved to amend her complaint and seek limited discovery after finding new evidence that the officer was working under color of state law. Eighth Circuit: The earlier decision controls—no § 1983 claim, and new evidence wouldn't change that. Affirmed. (This is an IJ case.)Oregon widow and mother of five wants to adopt two additional kids. A state agency has her take a class where, among other things, she's taught "[t]here are an infinite number of pronouns as new ones emerge in our language. Always ask someone for their pronouns." After she later says she doesn't agree with some of what the class taught or similar adoption policies, she's denied the chance to adopt. Ninth Circuit (over a dissent): Which violated her free speech and free exercise rights.You may not be surprised to learn that California requires a background check for every purchase of ammunition. You may be surprised to learn that even the Ninth Circuit (over a dissent) thinks the law violates the Second Amendment.District court (February): The Trump administration's executive order purporting to strip birthright citizenship is an unconstitutional travesty, and these plaintiffs deserve a universal injunction. Ninth Circuit (also February): That's not wrong! SCOTUS (June): Universal injunctions aren't even a thing, though maybe possibly the state plaintiffs need a nationwide injunction to get complete relief. Ninth Circuit (Wednesday): The state plaintiffs need a nationwide injunction to get complete relief. (Dissent: The state plaintiffs don't have standing to get any relief at all!)It seems like maybe bad business to fire a guy who put together the team that secured your company a $15 mil contract just because he said he needed an ADA accommodation to let him sit in exit rows on business trips, but the Tenth Circuit says there's enough evidence the defendant did exactly that for this case to go to the jury. Well, more specifically, it says the guy met the three-prong McDonnell-Douglas test to survive summary judgment without falling into either of the Reeves exceptions to those prongs—prompting a concurrence wondering why we need a system of prongs and anti-prongs instead of just saying "the facts presented at summary judgment make the case close enough to go to a jury."New Class! (Certified, that is.) For years, police have seized cash at the FedEx processing center at the Indianapolis airport—FedEx's second-largest hub in the country—and used civil forfeiture to keep the money. They did this to $42,000 on route to Henry and Minh Cheng, cash that was a legitimate payment to their wholesale jewelry business. The Chengs and IJ fought back, not just for them but to stop the wider unconstitutional practice. This week they received some good news: Their class was certified, meaning the lawsuit can proceed on behalf of everyone facing similar forfeiture actions.

The post Short Circuit: An inexhaustive weekly compendium of rulings from the federal courts of appeal appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Friday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Friday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

[Keith E. Whittington] Diversity Statements and the First Amendment

[My new article on diversity statements in faculty hiring and the First Amendment]

In 2024, I was honored to deliver the Roscoe Pound Lecture at the University of Nebraska College of Law. The article based on that lecture is now in print, and until the Nebraska Law Review updates its website with the contents of issue 4 of volume 103 you can find a PDF of the article here.

The article is called "Diversity Statements, Academic Freedom, and the First Amendment." From the abstract:

Diversity statements have become a common component of applications for faculty positions and student admission at universities across the country. They have also become politically controversial, with several states banning the use of such requirements at public universities. The use of diversity statements also raises difficult constitutional questions under the First Amendment at public universities and academic freedom questions at both public and private universities. Although there are versions of such statements that might pass constitutional muster, as commonly designed and implemented the use of diversity statements likely violates both First Amendment and academic freedom principles. Indeed, diversity statement requirements for faculty hiring are inconsistent with multiple lines of constitutional doctrine.

From the introduction:

This Article develops the constitutional case against the use of diversity statements across several parts. Part II describes what is known about how diversity statements are designed and used in universities. Part III outlines the academic freedom principles that are applicable to the use of diversity statements. Part IV reviews the history of the controversy of the use of loyalty oaths in universities in the mid-twentieth century and draws out some lessons from that experience. Part V applies government employee speech doctrine to the diversity statement requirements for faculty positions at state universities. Part VI applies the political patronage doctrine to diversity statement requirements for such positions. Part VII applies compelled speech doctrine to the use of such diversity statements. Part VIII summarizes the argument and concludes.

The thrust of over half a century of First Amendment doctrine is that state universities are to be the home of a wide diversity of thought and that the artificial imposition of intellectual uniformity on state university faculty runs contrary to First Amendment values. When state universities take adverse employment action against scholars, including by denying them employment, on the basis of their political and social ideas, the state bears a very high constitutional burden to justify such action. To sustain such action, the state must be able to demonstrate that it is taking measures that create the least interference with constitutionally protected expression that might be necessary to advance a compelling governmental interest. At the very least, this necessitates that the state be able to demonstrate that policies that burden disfavored political ideas are essential to advancing the genuine educational and scholarly mission of the university. Such speech restrictions should be professionally justifiable and not mere matters of political convenience or preference. Policies that merely serve to reinforce political orthodoxies on college campuses are constitutionally unjustifiable. Taking such principles seriously casts a substantial constitutional shadow over the practice of using diversity statements to exclude from state university faculties individuals with disfavored beliefs and opinions about matters of political and social controversy.

Read the whole thing here.

The post Diversity Statements and the First Amendment appeared first on Reason.com.

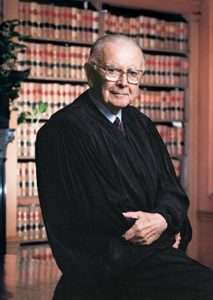

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: July 25, 1965

7/25/1965: Justice Arthur J. Goldberg resigns.

Justice Arthur Goldberg

Justice Arthur GoldbergThe post Today in Supreme Court History: July 25, 1965 appeared first on Reason.com.

July 24, 2025

[Josh Blackman] SG to SCOTUS: "District-Court Defiance of this Court's Decision in California has Grown to Epidemic Proportions"

["For good reason, the Constitution vests the 'judicial Power' in 'one supreme Court,' to which all others are 'inferior Courts.'"]

On a regular basis, district court judges accuse the Trump Administration of flouting the law, and ignoring their orders. The Washington Post counted the up! Yet, at the same time, district court judges are flouting Supreme Court precedent.

Just yesterday, in Boyle (not Moyle), the Supreme Court reversed a district court for not following Wilcox, which "squarely controlled."

Now, the Solicitor General has filed yet another emergency application. Here, a federal judge in Massachusetts ordered the government to pay out certain DEI grants. Under the Supreme Court's decision in Department of Education v. California, these disputes belong in the Court of Federal Claims. But lower federal courts disagreed.

The Solicitor General used especially sharp language to describe this lower-court resistance--no, not resistance of President Trump, but resistance of the Supreme Court itself.

This application presents a particularly clear case for this Court to intervene and stop errant district courts from continuing to disregard this Court's rulings. . . . Notwithstanding this Court's decision in California, the District of Massachusetts declined to stay a materially identical order. . . . When the government pointed out that respondents' challenges to those grant terminations belong in the Court of Federal Claims under California, the district court recognized with serious understatement that California was a "somewhat similar case." App., infra, 221a. Yet the district court dismissed this Court's ruling as "not final" and "without full precedential force," "agree[d] with the Supreme Court dissenters," and "consider[ed] itself bound" by the First Circuit ruling that California repudiated.

As I noted earlier, Boyle makes clear that shadow docket rulings are precedential, though I think that point was established during the COVID free exercise cases. Hell, Chief Justice Roberts's concurrence in South Bay was treated as a super precedent! In July 2022, I wrote about the precedential value of emergency docket rulings.

The Solicitor General writes that this resistance has grown to "epidemic proportions":

Worse, this case is no outlier. District-court defiance of this Court's decision in California has grown to epidemic proportions, as courts have issued nearly two dozen decisions asserting jurisdiction over claims challenging grant or funding terminations since California.

The SG, echoing Justice Kavanaugh's CASA concurrence, explains that the Supreme Court is supreme and the Inferior Courts are inferior.

For good reason, the Constitution vests the "judicial Power" in "one supreme Court," to which all others are "inferior Courts." U.S. Const. Art. III, § 1. As this Court explained yesterday, when lower courts face materially identical stay requests, this Court's emergency orders "squarely control[]." Boyle, slip op. 1. Our judicial system rests on vertical stare decisis, not a lower-court free-for-all where individual district judges feel free to elevate their own policy judgments over those of the Executive Branch, and their own legal judgments over those of this Court.

This . I think lower courts still will not get the memo. Let's see how long it take Circuit Justice Jackson to call for a response.

The post SG to SCOTUS: "District-Court Defiance of this Court's Decision in California has Grown to Epidemic Proportions" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Appeals Court Rules Trump's Birthright Citizenship Order is Unconstitutional and Upholds Nationwide Injunction Against it

[The court ruled that a nationwide injunction is the only way to provide complete relief to the state government plaintiffs in the case.]

Photo by saiid bel on Unsplash; Reamolko

Photo by saiid bel on Unsplash; Reamolko Yesterday, in Washington v. Trump, the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that Donald Trump's executive order denying birthright citizenship to children of undocumented immigrants and non-citizens present on temporary visas is unconstitutional. The court also upheld the district court's nationwide injunction against the order. Prominent conservative Judge Patrick Bumatay dissented on the ground that the plaintiff state governments lack standing.

This is the first appellate ruling on the legality of Trump's birthright citizenship order, though four federal district courts have previously ruled the same way. The majority opinion by Judge Ronald Gould does an excellent job of explaining why the order violates the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which grants citizenship to anyone "born … in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof." It effectively covers text, original meaning, Supreme Court precedent, and more. It's a compelling demolition of the administration's argument that people who illegally entered the US are not "subject to the jurisdiction" of the United States because they lack the proper "allegiance" and "domicile."

I would add that, if illegal entry by parents excludes a child born in the US from birthright citizenship, that would also have excluded large numbers of freed slaves. As Gabriel Chin and Paul Finkelman have shown in an important article, the freed slaves whose children were covered by the Citizenship Clause included a large population that had entered the US illegally, by virtue of being brought in after the federal government banned the slave trade in 1808. This shows that illegal entry was not considered a barrier to being under US jurisdiction. Granting black former slaves citizenship was the main objective of the Citizenship Clause.

For more on the shortcomings of the "domicile" theory, see this guest post by Evan Bernick.

As a result of the Supreme Court's ruling in Trump v. CASA barring nationwide injunctions, courts can no longer issue such injunctions merely because the government has engaged in large-scale nationwide illegality. But the Supreme Court nonetheless noted that nationwide remedies are permissible in cases where they are the only way to provide "complete relief" to the parties to the litigation. Here, the Ninth Circuit ruled that a nationwide injunction is the only way to provide complete relief to the plaintiff state governments, who otherwise stand to lose various federal grants and benefits allocated based on the number of citizens:

States' residents may give birth in a non-party state, and individuals subject to the Executive Order from non-party states will inevitably move to the States….. To account for this, the States would need to overhaul their eligibility-verification systems for Medicaid, CHIP, and Title IV-E. For that reason, the States would suffer the same irreparable harms under a geographically-limited injunction as they would without an injunction.

These kinds of harms are probably only a small proportion of the losses the states would suffer from implementation of Trump's executive order. But remedying them is still essential for purposes of providing complete relief.

In his dissenting opinion, Judge Bumatay does not consider either the constitutionality of Trump's order, or the proper scope of the injunction. He instead argues the case should be dismissed because the state plaintiffs lack standing. He contends the harms from loss of federal funds and benefits are too unclear, speculative, and indirect.

I won't try to go over the standing issue in detail. But, overall, I think the majority is more persuasive on this issue. It is indeed difficult to predict exactly how much money the states will lose if Trump's order is implemented. Among other things, as Bumatay notes, it will depend in part on exactly how implementation works. But it is virtually certain they will lose at least some funds, and even a small amount of direct economic damage is enough to justify standing.

That said, the Supreme Court's jurisprudence on state government standing is far from a model of clarity. Thus, I cannot be certain what will happen if this issue were to get to the Supreme Court.

I myself have long advocated for broad standing for both state and private litigants, including state governments advancing claims I oppose on the merits. It is vital that illegal federal policies not be immunized from challenge by arbitrary judicially created procedural rules. State standing is especially important in the aftermath of Trump v. CASA's ill-advised evisceration of universal injunctions. States are often entitled to broader remedies than private litigants, given the greater scope of the harms they might suffer.

State standing may not be the only way to secure a universal remedy against Trump's birthright citizenship order. In one of the other cases challenging it, a federal district court has granted a nationwide class action certification. Both this remedy and that upheld by the Ninth Circuit may well end up being reviewed by the Supreme Court when - as seems likely - it takes up the merits of the birthright citizenship litigation.

The post Appeals Court Rules Trump's Birthright Citizenship Order is Unconstitutional and Upholds Nationwide Injunction Against it appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Post] Trump v. The Wall Street Journal

[Trial of the Century! See the Billionaire Media Titans Wrestling in the Mud! Coming to your screens this Fall!]

It is, I suppose, an illustration of just how diminished and even sordid our political life has become these days that L'Affaire Epstein is the hot political show of the summer. But there it is. We'll see if it has legs for an extended run into the new fall season.

Here's what we know: Media megastar and ex-"Apprentice" co-producer and host Donald Trump has sued media megamogul Rupert Murdoch and The Wall Street Journal for defamation in federal district court [SD FL]. [The Complaint is available here] The suit is based on a front-page WSJ story asserting that a "letter bearing Trump's name" appeared in a 2003 birthday album celebrating Jeffrey Epstein's 50th birthday. The story described the letter this way:

"The letter bearing Trump's name, which was reviewed by the Journal, is bawdy—like others in the album. It contains several lines of typewritten text framed by the outline of a naked woman, which appears to be hand-drawn with a heavy marker. A pair of small arcs denotes the woman's breasts, and the future president's signature is a squiggly "Donald" below her waist, mimicking pubic hair. The letter concludes: "Happy Birthday — and may every day be another wonderful secret."

Trump says that there is no such letter. The Complaint states:

"[Defendants] falsely claimed that [Trump] authored, drew, and signed a card to wish the late—and utterly disgraced—Jeffrey Epstein a happy fiftieth birthday. . . . [N]o authentic letter or drawing exists. Defendants concocted this story to malign President Trump's character and integrity and deceptively portray him in a false light. . . . [T]he supposed letter is a fake and the Defendants knew it when they chose to deliberately defame President Trump." [emph. added]

Needless to say, I haven't the faintest idea whether the letter does or does not exist. If it does, though, Trump would surely know that it does, and, knowing that, he'd be an absolute madman to file this suit. That makes me think there's no such letter. On the other hand, surely the editors at the WSJ, a newspaper not known for manufacturing fake news, knew that the article was a potential bombshell, and would have taken extra-special precautions to ensure that all facts stated therein were true. That makes me think there is such a letter.

My strong suspicion is that the Journal will be able to produce a salacious letter "bearing Trump's name" – it is inconceivable that the Journal would have proceeded if such a thing did not actually exist - and that Trump will deny authorship or any knowledge of it. His defamation claim will require him to show not only that the letter in the Journal's possession is a fake, but also that the WSJ's investigation of the letter's provenance was inadequate, amounting to a "reckless indifference" to whether or not it was a fake.

The history of high-profile defamation lawsuits is littered with the carcasses of plaintiffs who ended up deeply regretting their decision to sue, from, most famously, Oscar Wildeto Teddy Roosevelt and James Whistler and Henry Ford to Jerry Falwell and Johnny Depp. Not only do these lawsuits often bring unwanted and intense media scrutiny to the allegations that otherwise might have gone completely unnoticed, but because truth is a defense to a defamation claim, the lawsuit exposes to public view whatever evidence the defendant might uncover relevant to the challenged claims, which can expose an enormous amount of the plaintiff's dirty underwear to public view.

Harry Litman over at the New Republic thinks Trump's name is going to be added to this list, and, personally, I hope he's correct (though Trump has defied these kinds of expectations many, many times in the past). One can certainly imagine any number of ways a trial could backfire – bringing to light more information about the letter, the reasons why the WSJ concluded it came from Trump, and, more generally, the close relationship between Trump and Epstein.

Trump, of course, famously said that he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue in New York and not lose any supporters, and so far there has been nothing to contradict that. But participating in a billionaire's underage girls sex ring – IF the evidence reveals such a participation – might well be the bridge too far for many of his supporters. One would certainly hope so, for the good of the Republic.

I cannot wait to see how this plays out. This is sure to be Must-See TV. My only fear is that the Journal is pressured into settling the claim. So bad for ratings!

Wilde – far and away the most successful author in Europe and quite possibly the world at the time – sued the Marquess of Queensberry for having publicly called him a "posing Somdomite" [sic]. Because truth is a defense to a defamatory libel charge, Queensberry was allowed to introduce a large trove of evidence concerning Wilde's eccentric sexual proclivities, which ultimately led to Wilde's arrest, conviction, and imprisonment on charges of sodomy and gross indecency. It ruined both his career and his life; he died, impoverished and in exile, three years after his release from prison – but not before writing "De Profundis," his remarkable and moving confessional. [See here]

In 1903, TR ordered his Attorney General to institute criminal proceedings against the New York World newspaper for "seditious libel against the government of the United States" for having suggested in several articles that corruption and bribery had tainted Roosevelt's actions in connection with the building of the Panama Canal. The courts – including, ultimately, the Supreme Court – dismissed the indictment on the grounds that there was no statutory authority for a criminal action of this kind. It was an embarrassing defeat for Roosevelt, and was widely viewed as an unprecedented and unwarranted attack on the freedom of the press - as one contemporary history of the affair (still in print here) put it: "The Attempt Of President Roosevelt By Executive Usurpation To Destroy The Freedom Of The Press In The United States."

The well-known American painter James Whistler sued art critic John Ruskin for libel for having written, in reference to one of Whistler's paintings, "I never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public's face." He won – and was, humiliatingly, awarded jury damages of one farthing.

In 1916 Ford warned employees that they would lose their jobs if they volunteered for National Guard duty in order to participate in a border war with Mexico. Robert McCormick wrote an editorial in the Chicago Tribune complaining of "flivver patriotism," and averred that the policy demonstrated that Ford was "an ignorant idealist [and] an anarchist enemy of the nation which protects his wealth." Ford sued, and testified for nine days at the trial, which revealed that he was something of an ignoramus. He won the case, and was awarded a judgment of six cents (after having spent over $100,000 in 1916 dollars to prosecute the suit).

Rev. Jerry Falwell sued Hustler magazine for publishing an advertisement "parody" which, among other things, portrayed Falwell as having engaged in a drunken incestuous rendezvous with his mother in an outhouse. Falwell lost on both his libel claim and his intentional infliction of emotional distress claim after reaching the Supreme Court, which held that "the interest of protecting free speech, under the First Amendment, surpassed the state's interest in protecting public figures from patently offensive speech, so long as such speech could not reasonably be construed to state actual facts about its subject." The suit, of course, brought a great deal of public attention to the parody which would almost certainly have been ignored had Falwell let it die a natural death.

Johnny Depp sued The Sun newspaper (U.K) for defamation after they called him a "wife-beater" in an article. Amber Heard, Depp's ex-wife, was a key witness in the case, and their tumultuous relationship became the subject of intense media scrutiny. The UK court found that Depp had indeed committed acts of violence against Heard, a finding that greatly injured Depp's reputation and career.

This is a close relative of the well-known "Streisand Effect," a reference to Barbra Streisand's 2003 lawsuit against the photographer Kenneth Adelman. Adelman had taken an aerial photo of Streisand's house as part of a project on documenting coastal erosion. Streisand claimed that publication of the photo on Adelman's website was an invasion of her privacy. The photo, which had been downloaded fewer than 10 times prior to her filing, immediately went viral and was seen by millions of viewers who would surely otherwise have been unaware of its existence.

On the other hand, maybe this is all a huge Murdoch-Trump set-up designed to enhance Trump's standing when the Journal backs down. Maybe that's what JD Vance was talking to the Murdochs about back in June . . .

The post Trump v. The Wall Street Journal appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: July 24, 1997

7/24/1997: Justice William Brennan dies.

Justice William Brennan

Justice William Brennan

The post Today in Supreme Court History: July 24, 1997 appeared first on Reason.com.

July 23, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Hallucinations in the District of New Jersey

[Is it an abuse of judicial power for a judge to issue an opinion with AI hallucinations?]

Eugene blogged about Judge Julien Xavier Neals of the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey. Judge Neals issued an opinion that included errors, including made-up quotes and incorrect case outcomes. One of the parties submitted a letter pointing out these errors. It seems pretty clear that the Judge, or at least someone in his chambers, used generative AI to create the opinion. (Judge Neals is sixty years old, so I would suspect a law clerk made this error.) The judge promptly withdrew the opinion.

I suppose this particular case is settled, but I would wager there are more orders on Judge Neals' dockets that have hallucinations. Indeed, I suspect there are many judges throughout the country that have issued opinions with hallucinations. Savvy litigators should start combing through all adverse orders, and try to determine if there are obvious indicia of hallucinations. This will make excellent grounds for reversal on appeal.

But let's take a step back. What do we make of a judge who issues an opinion based on made-up cases? To be sure, judges makes mistakes all the time. Moreover, clerks make mistakes that their judges do not catch. When I was clerking, I made a particularly egregious error that my judge did not catch. The non-prevailing party promptly filed a motion for reconsideration. The opinion was withdrawn, and a new opinion was issued. The outcome of the case was not altered by that error, but at least the opinion was corrected.

Still, one might ask how closely Judge Neals, and other judges, review the work of their law clerks. Do the judges actually check the citations to see if they are hallucinated? I would suspect most judges do not check citations. District Court dockets are very busy, and it is not realistic to expect judges to so closely scrutinize their clerks' work. (Later in Justice Blackmun's career, he apparently limited his review of draft opinions to checking citations.)

I think the more useful frame is to ask whether the judge has failed to adequately supervise his law clerks. Judges invariably have to delegate authority to law clerks, even if the judge ultimately signs all of the orders. That delegation must include what is effectively a duty of care. In other words, the judge should tell the clerk how to go about doing the job, and in particular, how not to go about doing the job. In 2025, I think all judges should tell their clerks to either not use AI at all (my advice), or to use AI responsibly and triple-check any cited cases. The failure to give this advice would be an abuse of discretion.

But is it more than just an abuse of discretion? Does an Article III judge abuse his power when he issues an opinion based on hallucinated cases that no one in his chambers bothered to check? Judges have the awesome power to affect a person's life, liberty, or property, merely by signing their names to a piece of paper. It is the order, and not the opinion, that has the legal effect.

I think we would all agree that a judge would abuse his power by deciding a case by flipping a coin or rolling a dice. I suppose using AI is a bit less reckless than a game of chance, but not by much. Relatedly, is it an abuse of power when a judge grants an ex parte TRO without evening reading the brief? I think we are starting to see some of the boundaries of the judicial power.

I don't know that Judge Neals will receive a misconduct complaint, as he promptly withdrew his opinion. But an enterprising sleuth could do a close analysis of all opinions from Judge Neals, and judges nationwide, and perhaps find a pattern of misconduct. Would that record show a judge cannot be trusted to exercise the judicial power?

And speaking of the District of New Jersey, can we be certain that Judge Neals voted to appoint Desiree Grace as the United States Attorney for the District of New Jersey? Or maybe it was a Chatbot?

I'll leave you with one anecdote I read in a recent article about what AI is doing to students:

My unease about ChatGPT's impact on writing turns out to be not just a Luddite worry of poet-professors. Early research suggests reasons for concern. A recent M.I.T. Media Lab study monitored 54 participants writing essays, with and without A.I., in order to assess what it called "the cognitive cost of using an L.L.M. in the educational context of writing an essay." The authors used EEG testing to measure brain activity and understand "neural activations" that took place while using L.L.M.s. The participants relying on ChatGPT to write demonstrated weaker brain connectivity, poorer memory recall of the essay they had just written, and less ownership over their writing, than the people who did not use L.L.M.s. The study calls this "cognitive debt" and concludes that the "results raise concerns about the long-term educational implications of L.L.M. reliance."

I still refuse to use AI. I may be the last man standing.

The post Hallucinations in the District of New Jersey appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers