Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 63

July 31, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] UCLA Stipulates to Permanent Injunction as to Alleged Exclusion of Jewish or Pro-Israel Students from Parts of Campus [UPDATE: + $6M Payment]

[UPDATE 7/31/2025 12:09 pm: The agreement also apparently includes an over $6M payment by UC; according to the N.Y. Times (Anemona Hartocollis), "The settlement, which still has to receive final approval from a judge, would give $50,000 to each of the named plaintiffs, including two law students, one undergraduate and one medical school professor. It would distribute $2.33 million among eight nonprofits, including Hillel at UCLA, the Anti-Defamation League and Chabad House at UCLA; $320,000 to a U.C.L.A. account dedicated to combating antisemitism; and the rest to costs and legal fees."]

From today's proposed stipulated judgment in Frankel v. Regents (C.D. Cal.):

a. The Regents of the University of California, President of the University of California, the Chancellor of UCLA, the Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost of UCLA, the Administrative Vice Chancellor of UCLA, the Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs of UCLA, and the Associate Vice Chancellor for Campus and Community Safety of UCLA—in their official capacities (collectively, the "Enjoined Parties")—are enjoined from offering any of UCLA's ordinarily available programs, activities, or campus areas to students, faculty, and/or staff if the Enjoined Parties know the ordinarily available programs, activities, or campus areas are not fully and equally accessible to Jewish students, faculty, and/or staff.

b. The Enjoined Parties are prohibited from knowingly allowing or facilitating the exclusion of Jewish students, faculty, and/or staff from ordinarily available portions of UCLA's programs, activities, and/or campus areas, whether as a result of a de-escalation strategy or otherwise.

c. For purposes of this order, all references to the exclusion of Jewish students, faculty, and/or staff shall include exclusion of Jewish students, faculty, and/or staff based on religious beliefs concerning the Jewish state of Israel.

d. Nothing in this order prevents the Enjoined Parties from excluding any student, faculty member, or staff member, including Jewish students, faculty, and/or staff, from ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas pursuant to UCLA code of conduct standards applicable to all UCLA students, faculty, and/or staff.

e. Nothing in this order requires the Enjoined Parties to immediately cease providing medical treatment at hospital and medical facilities, fire department services, and/or police department services. However, the Enjoined Parties remain obligated to take all necessary steps to ensure that such services and facilities remain fully and equally open and available to Jewish students, faculty, and/or staff.

Here's the backstory, from my post a year ago about the preliminary injunction in the case:

[* * *]

From [the] order by Judge Mark Scarsi (C.D. Cal.) in Frankel v. Regents:

In the year 2024, in the United States of America, in the State of California, in the City of Los Angeles, Jewish students were excluded from portions of the UCLA campus because they refused to denounce their faith. This fact is so unimaginable and so abhorrent to our constitutional guarantee of religious freedom that it bears repeating, Jewish students were excluded from portions of the UCLA campus because they refused to denounce their faith. UCLA does not dispute this. Instead, UCLA claims that it has no responsibility to protect the religious freedom of its Jewish students because the exclusion was engineered by third-party protesters. But under constitutional principles, UCLA may not allow services to some students when UCLA knows that other students are excluded on religious grounds, regardless of who engineered the exclusion….

On April 25, 2024, a group of pro-Palestinian protesters occupied a portion of the UCLA campus known as Royce Quad and established an encampment. Royce Quad is a major thoroughfare and gathering place and borders several campus buildings, including Powell Library and Royce Hall. The encampment was rimmed with plywood and metal barriers. Protesters established checkpoints and required passersby to wear a specific wristband to cross them. News reporting indicates that the encampment's entrances were guarded by protesters, and people who supported the existence of the state of Israel were kept out of the encampment. Protesters associated with the encampment "directly interfered with instruction by blocking students' pathways to classrooms."

Plaintiffs are three Jewish students who assert they have a religious obligation to support the Jewish state of Israel. Prior to the protests, Plaintiff Frankel often made use of Royce Quad. After protesters erected the encampment, Plaintiff Frankel stopped using the Royce Quad because he believed that he could not traverse the encampment without disavowing Israel. He also saw protesters attempt to erect an encampment at the UCLA School of Law's Shapiro courtyard on June 10, 2024.

Similarly, Plaintiff Ghayoum was unable to access Powell Library because he understood that traversing the encampment, which blocked entrance to the library, carried a risk of violence. He also canceled plans to meet a friend at Ackerman Union after four protesters stopped him while he walked toward Janss Steps and repeatedly asked him if he had a wristband. Plaintiff Ghayoum also could not study at Powell Library because protesters from the encampment blocked his access to the library.

And Plaintiff Shemuelian also decided not to traverse Royce Quad because of her knowledge that she would have to disavow her religious beliefs to do so. The encampment led UCLA to effectively make certain of its programs, activities, and campus areas available to other students when UCLA knew that some Jewish students, including Plaintiffs, were excluded based of their genuinely held religious beliefs.

The encampment persisted for a week, until the early morning of May 2, when UCLA directed the UCLA Police Department and outside law enforcement agencies to enter and clear the encampment. Since UCLA dismantled the encampment, protesters have continued to attempt to disrupt campus. For example, on May 6, protesters briefly occupied areas of the campus. And on May 23, protesters established a new encampment, "erecting barricades, establishing fortifications and blocking access to parts of the campus and buildings," and "disrupting campus operations."

Most recently, on June 10, protesters "set up an unauthorized and unlawful encampment with tents, canopies, wooden shields, and water-filled barriers" on campus. These protesters "restricted access to the general public" and "disrupted nearby final exams." Some students "miss[ed] finals because they were blocked from entering classrooms," and others were "evacuated in the middle" of finals.

Based on these facts and other allegations, Plaintiffs assert claims for violations of their federal constitutional rights, including violation of the Equal Protection Clause, the Free Speech Clause, and the Free Exercise Clause; claims for violations of their federal civil rights, including violations of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, conspiracy to interfere with civil rights, and failure to prevent conspiracy; claims for violations of their state constitutional rights, including violation of the California Equal Protection Clause and the California Free Exercise Clause; and claims for violations of their state civil rights, including violations of section 220 of the California Education Code, the Ralph Civil Rights Act of 1976, and the Bane Civil Rights Act….

The court rejected UCLA's standing objections, in part reasoning:

UCLA argues that Plaintiffs lack standing because they fail to allege an imminent likelihood of future injury…. UCLA contends that its remedial actions following the Royce Quad encampment make any "future injury speculative at best." These actions include the creation of a new Office of Campus Safety and the transfer of day-to-day responsibility for campus safety to an Emergency Operations Center. The changes, while commendable, do not minimize the risk that Plaintiffs "will again be wronged" by their exclusion from UCLA's ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas based on their sincerely held religious beliefs below "a sufficient likelihood."

First, since UCLA's changes, protesters have violated UCLA's protest rules at least three times: on May 6, May 23, and June 10. While these events may not have been as disruptive as the Royce Quad encampment, according to a UCLA email, the June 10 events "disrupted final exams," temporarily blocked off multiple areas of campus, and persisted from 3:15 p.m. to the evening. Similarly, also according to UCLA emails, the May 6 and 23 events disrupted access to several campus areas. Further, any relative quiet on UCLA's campus the past few months is belied by the facts that fewer people are on a university campus during the summer and that the armed conflict in Gaza continues.

Finally, while UCLA's focus on safety is compelling, UCLA has failed to assuage the Plaintiffs' concerns that some Jewish students may be excluded from UCLA's ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas based on their sincerely held religious beliefs should exclusionary encampments return. In response to these concerns raised at the hearing, UCLA did "not state[] affirmatively that" they "will not" provide ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas to non-Jewish students if protesters return and exclude Jewish students.

It remains to be seen how effective UCLA's policy changes will be with a full campus. While the May and June protests do not appear to have resulted in the same religious-belief-based exclusion as the prior encampment that gives rise to the Plaintiffs' free exercise concerns, the Court perceives an imminent risk that such exclusion will return in the fall with students, staff, faculty, and non-UCLA community members. As such, given that when government action "implicates First Amendment rights, the inquiry tilts dramatically toward a finding of standing," the Court finds that Plaintiffs have sufficiently shown an imminent likelihood of future injury for standing purposes….

And the court concluded that plaintiffs were likely to succeed on their Free Exercise Clause claim (and thus declined to consider any of the other claims):

The Free Exercise Clause … "'protect[s] religious observers against unequal treatment' and subjects to the strictest scrutiny laws that target the religious for 'special disabilities' based on their 'religious status.'" "[A] State violates the Free Exercise Clause when it excludes religious observers from otherwise available public benefits." …

Here, UCLA made available certain of its programs, activities, and campus areas when certain students, including Plaintiffs, were excluded because of their genuinely held religious beliefs. For example, Plaintiff Frankel could not walk through Royce Quad because entering the encampment required disavowing the state of Israel. Similarly, Plaintiff Ghayoum was prevented from entering a campus area at a protester checkpoint, and Plaintiff Shemuelian could not traverse Royce Quad, unlike other students…. Plaintiffs' exclusion from campus resources while other students retained access raises serious questions going to the merits of their free exercise claim….

Plaintiffs have put forward a colorable claim that UCLA's acts violated their Free Exercise Clause rights. Further, given the risk that protests will return in the fall that will again restrict certain Jewish students' access to ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas, the Court finds that Plaintiffs are likely to suffer an irreparable injury absent a preliminary injunction…….

Under the Court's injunction, UCLA retains flexibility to administer the university. Specifically, the injunction does not mandate any specific policies and procedures UCLA must put in place, nor does it dictate any specific acts UCLA must take in response to campus protests. Rather, the injunction requires only that, if any part of UCLA's ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas become unavailable to certain Jewish students, UCLA must stop providing those ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas to any students. How best to make any unavailable programs, activities, and campus areas available again is left to UCLA's discretion….

The court therefore issued the following order:

[1.] Defendants Drake, Block, Hunt, Beck, Gordon, and Braziel ("Defendants") are prohibited from offering any ordinarily available programs, activities, or campus areas to students if Defendants know the ordinarily available programs, activities, or campus areas are not fully and equally accessible to Jewish students.

[2.] Defendants are prohibited from knowingly allowing or facilitating the exclusion of Jewish students from ordinarily available portions of UCLA's programs, activities, and campus areas, whether as a result of a de-escalation strategy or otherwise.

[3.] On or before August 15, 2024, Defendants shall instruct Student Affairs Mitigator/Monitor ("SAM") and any and all campus security teams (including without limitation UCPD and UCLA Security) that they are not to aid or participate in any obstruction of access for Jewish students to ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas.

[4.] For purposes of this order, all references to the exclusion of Jewish students shall include exclusion of Jewish students based on religious beliefs concerning the Jewish state of Israel.

[5.] Nothing in this order prevents Defendants from excluding Jewish students from ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas pursuant to UCLA code of conduct standards applicable to all UCLA students.

[6.] Absent a stay of this injunction by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, this preliminary injunction shall take effect on August 15, 2024, and remain in effect pending trial in this action or further order of this Court or the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

The court also noted:

[T]his case [is not] about the content or viewpoints contained in any protest or counterprotest slogans or other expressive conduct, which are generally protected by the First Amendment. See Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343, 358 (2003) ("The hallmark of the protection of free speech is to allow 'free trade in ideas'—even ideas that the overwhelming majority of people might find distasteful or discomforting." (quoting Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616, 630 (1919) (Holmes, J., dissenting)); see also Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397, 414 (1989) ("If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.").

Amanda G. Dixon, Richard C. Osborne, Eric C. Rassbach, Mark L. Rienzi, Laura W. Slavis, and Jordan T. Varberg (Becket Fund), Erin E. Murphy, Matthew David Rowen, and former U.S. Solicitor General Paul Clement (Clement & Murphy, LLC), and Elliot Moskowitz, Marc J. Tobak, and Adam M. Greene (Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP) represent plaintiffs.

The post UCLA Stipulates to Permanent Injunction as to Alleged Exclusion of Jewish or Pro-Israel Students from Parts of Campus [UPDATE: + $6M Payment] appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "If Doe Wishes to Use Judicial Proceedings" "to Seek Relief from … Defamat[ion],"

["he must do so under his true name and accept the risk that certain unflattering details may come to light over the course of the litigation."]

From Judge John J. Tharp, Jr. (N.D. Ill.) in yesterday's Doe v. Ahrens:

Plaintiff John Doe has filed this suit against defendant Valery J. Ahrens, alleging that after the two engaged in a long-distance, casual relationship, conducted largely online and over the phone, Ahrens began stalking and harassing him. Doe, who describes himself in the Amended Complaint as "a self-made entrepreneur, author, internet personality, [] venture capitalist … [and] a dedicated and loving father," alleges that Ahrens sent him non-stop messages and created various social media accounts for the purpose of publishing false and unflattering information about him, often engaging with his followers to direct them to these accounts.

Further, Doe alleges that Ahrens broadcast certain private, sexual telephone exchanges between the two that, Doe says, he did not know she was recording. Doe claims these actions amount to defamation per se, false light invasion of privacy, public disclosure of private facts, and intentional infliction of emotional distress under state law, and has invoked diversity jurisdiction for his federal suit.

With his complaint, Doe filed a motion to proceed under a pseudonym, arguing that given her past behavior, Ahrens is likely to "weaponize" this case and any filings therein to "exacerbate" the harm she has already allegedly inflicted on Doe. Doe argues that given the sensitivity of Ahrens's posts about Doe, and the fact that the "veracity" of those posts will be central to his defamation claims, he should be allowed to pursue his claims without further damaging his reputation.

"The norm in federal litigation is that all parties' names are public." This is because judicial proceedings are public and "[i]dentifying the parties to the proceedings is an important dimension of publicness. The people have a right to know who is using their courts." Departures from that norm are justified in cases involving, for example, parties who are minors or who have reason to fear physical harm or retaliation by third parties as a result of the litigation. Pseudonyms may also be allowed in cases involving victims of sex crimes.

The Seventh Circuit has "held that a desire to keep embarrassing information secret does not justify anonymity." … "[F]ear of stigmatization and a desire not to reveal intimate details were not enough to justify anonymity for the plaintiff." . . . Moreover, "the Seventh Circuit generally opposes allowing sexual harassment claimants to proceed anonymously."

In his motion and reply brief, Doe argues that this case is "exceptional" due to Ahrens's extreme, prolific, and long-running efforts to publicly defame and embarrass him. Even after Doe filed his complaint, he alleges, Ahrens threatened to publicize their phone and video calls, intervened in his personal relationships, posted about Doe online (using his real name and photo), and even lodged an unsuccessful complaint against Doe's counsel with the Attorney Registration and Disciplinary Committee. For the purposes of weighing the merits of Doe's motion, the Court will assume the truth of these allegations.

Doe believes that revealing his name "will embolden Ahrens to disseminate every public filing and discovery response filed or exchanged in this litigation" while "hid[ing] behind the litigation privilege and craft[ing] pleadings designed to inflict greater mental distress and deter Plaintiff from continuing to seek redress[.]"Doe in fact separately moved for a protective order pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(c), which the Court granted in part by ordering any materials filed by the parties related to the communications recorded (whether video or audio) by Ahrens to be filed under seal.

The problem for Doe is that the potential harms he identifies are not the sort which are appropriately remedied by proceeding under a pseudonym. Doe fears that Ahrens will use this litigation—the fact of its existence, and any filings made therein—in her continued campaign against him, causing him further reputational and emotional damage. But the Seventh Circuit has been quite clear that reputational harm alone is not an adequate justification for proceeding anonymously. And Doe has not offered any other specific consequence he fears will befall him if his name is made public in connection with this litigation other than that potential reputational harm. Only "[a] substantial risk of harm—either physical harm or retaliation by third parties, beyond the reaction legitimately attached to the truth of events as determined in court—may justify anonymity."

Further, while not bound to follow it, the Court finds persuasive the reasoning set forth in Doe v. Doe (4th Cir. 2023), a decision from the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit highlighted by the intervenor in this case, Eugene Volokh, an academic and journalist. In its ruling, the Fourth Circuit affirmed a denial of a plaintiff's motion to proceed under a pseudonym in a defamation case:

[W]e fail to see how Appellant can clear his name through this lawsuit without identifying himself. If Appellant were successful in proving defamation, his use of a pseudonym would prevent him from having an order that publicly "clears" him. It is apparent that Appellant wants to have his cake and eat it too. Appellant wants the option to hide behind a shield of anonymity in the event he is unsuccessful in proving his claim, but he would surely identify himself if he were to prove his claims.

If Doe wishes to use judicial proceedings against Ahrens—who is publicly named in this case—to seek relief from her allegedly defamatory and harassing behavior, he must do so under his true name and accept the risk that certain unflattering details may come to light over the course of the litigation.

This is not to say that Doe has no recourse to protect himself if he fears that Ahrens will continue to post about him or broadcast illicitly recorded conversations. Doe has already sought a protective order pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(c), which the Court granted in part by directing any materials related to the contents of communications (whether audio or video) recorded by the Ahrens to be filed under seal. That order will remain in place for now, as the parties proceed into discovery. Doe is also free to seek preliminary injunctive relief against Ahrens if, as he indicates in his reply brief, he believes he is at imminent risk of further defamation by Ahrens. But he must seek any relief against Ahrens under his true name….

The post "If Doe Wishes to Use Judicial Proceedings" "to Seek Relief from … Defamat[ion]," appeared first on Reason.com.

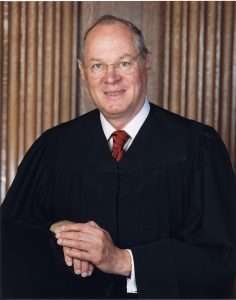

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: July 31, 2018

7/31/2018: Justice Anthony Kennedy retired.

Justice Anthony Kennedy

Justice Anthony Kennedy

The post Today in Supreme Court History: July 31, 2018 appeared first on Reason.com.

July 30, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] "Federal Judge's Order" "Lists Incorrect Parties," Includes "Wrong Quotes" and Nonexistent Cases

From Mississippi Today (Taylor Vance & Devna Bose) on Monday:

A ruling from a federal judge in Mississippi contained factual errors — listing plaintiffs who weren't parties to the suit, including incorrect quotes from a state law and referring to cases that don't appear to exist — raising questions about whether artificial intelligence was involved in drafting the order.

U.S. District Judge Henry T. Wingate issued an error-laden temporary restraining order on July 20, pausing the enforcement of a state law that prohibits diversity, equity and inclusion programs in public schools and universities.

Lawyers from the Mississippi Attorney General's Office asked him to clarify the order on Tuesday, and attorneys for the plaintiffs did not oppose the state's request. On Wednesday, Wingate replaced the order with a corrected version.

His original order no longer appears on the court docket, so the public no longer has access to it. The corrected order is backdated to July 20, even though it was filed three days later.

The article also notes that the replacement order still cites "Cousins v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 503 F.2d 422, 426–27 (4th Cir. 1974)," though no case with that name or at that citation appear to exist. As the article notes, it's not certain that these errors stemmed from the use of AI (the judge's chambers apparently didn't respond to the newspaper's query about this), but this seems like a plausible speculation given the facts that the newspaper reports.

You can also read the defendants' Motion to Correct Docket, Preserve Record, and for Clarification which seeks to place the original TRO back in the record (and which indeed attaches the original TRO).

Thanks to Damien Charlotin (AI Hallucination Cases Database) for the pointer.

The post "Federal Judge's Order" "Lists Incorrect Parties," Includes "Wrong Quotes" and Nonexistent Cases appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] New Pacific Legal Foundation Report Based on 50 Freedom of Information Requests to Top Law Schools: ABA Accreditation Frequently Nudges Law Schools Toward Illegal Discrimination

[A guest post from Alison Somin.]

I have written at some length about the problems with ABA accreditation. Alas, some of the most egregious behaviors from the ABA are considered confidential. Thankfully, the Pacific Legal Foundation sent public information requests to 50 public law schools concerning their accreditation process. The ABA routinely encourages schools to engage in unlawful discrimination, and rewards schools that are engaging in unlawful discrimination. The results are at once disappointing, but entirely predictable. The mere fact that the ABA temporarily suspended its DEI mandates does not mean much. They will revert to form as soon as the political pressure is gone.

Here is an excerpt from the report:

On the one hand, 20 law schools received accreditation reports indicating failure to meet the ABA's diversity standards. Common points of failure included not having enough minority faculty, not having enough women faculty, not having enough student diversity, failing to follow through with diversity plans, concerns about the treatment of minority faculty, having limited DEI curriculum integration, not having enough LGBTQ+ support groups, and attrition concerns for minority students. On the other hand, 25 law schools received accreditation reports acknowledging or praising the schools' compliance with the ABA's diversity standards. Common commendations included having a strong commitment to hiring diverse faculty, having diversity-focused scholarships and fellowships, having pipeline programs for minority students, having active DEI committees and task forces, having diversity recruitment strategies, having inclusive classroom initiatives, having a presence of DEI leadership positions, and having faculty diversity training.

Figure 1 displays the number of law schools that received qualitative evaluations of a variety of accreditation diversity standards. Each category aligns with a question in the accreditation report. No more than 15 of the 50 law schools received qualitative evaluations in any particular category.

[image error]

I asked PLF Senior Legal Fellow Alison Somin (and wife of co-blogger Ilya) to write about the report. Her post follows below.

--

The American Bar Association has frequently pressured law schools into unlawful race and sex discrimination in faculty hiring and admissions, according to a recently released Pacific Legal Foundation report I co-authored with my colleague Caitlin Styrsky.

PLF's research team sent freedom of information requests to the 50 public law schools ranked highest by U.S. News and World Report. Forty-five schools ultimately responded. Twenty of the forty-five were faulted by the ABA in some way for not adequately meeting the ABA's diversity standards. Schools were criticized, among other things, for not having enough minority faculty, not having enough women faculty, not having enough racial minority students, and failing to follow through with diversity plans.

Concerns about inappropriate accreditor pressure toward discrimination is nothing new. PLF's report cites a number of news stories about the phenomenon dating back to the 1990s, both at law schools and other institutions. A United States Commission on Civil Rights report from 2007 recounts in detail the saga of George Mason University School of law (now Scalia Law School), which spent years skirmishing with the ABA about the racial composition of its student body, until it finally quietly gave up and started offering significant preferences in admissions. But to my knowledge, PLF's report is the first to look systematically at accreditor pressure at a significant number of schools.

The ABA accreditation process doesn't just provide law schools with the academic equivalent of the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. In most states, students must graduate from an ABA accredited law school to be able to take the bar exam and eventually become lawyers. Losing accreditation is basically a death sentence for most law schools, and they will be inclined to do anything to avoid it. In this context, the message to law schools is clear: get the ABA the demographic numbers it wants, even if you have to discriminate in violation of the law to get there.

The accreditation process was originally intended to protect students from diploma mills – scams that would take a student's money without actually providing them with much of an education. This basic consumer protection principle became especially important once federal money started to flow into higher education following the enactment of the G.I. Bill. Eventually, in 1965, Congress enacted the Higher Education Act that required federal money to go only to accredited institutions of higher learning.

Accreditation was never supposed to be about social engineering for the sake of social engineering. Yet much of what the ABA's diversity standards demand of institutions are really about nudging institutions toward pursuing the ABA's vision of social justice, not about ensuring that students receive high quality legal education. Indeed, much empirical research actually cuts the other way, suggesting that race preferences in admissions harm their intended beneficiaries.

Two years ago, the Supreme Court's Students for Fair Admissions opinion made clear that race discrimination in admissions is unlawful: "Eliminating race discrimination means eliminating all of it," Chief Justice Roberts wrote for the majority. But that promise will not be fully realized if accreditors are pushing schools to violate the law.

Even before Students for Fair Admissions, some states adopted constitutional provisions stricter than those found in federal law prohibiting the use of race or sex in public employment or education. California's Civil Rights Initiative (Prop 209) from 1996 is perhaps the best-known example, but Florida, Michigan, and a number of other states have since followed suit. For at least some law schools, it would be difficult or outright impossible to meet the ABA's diversity quotas without discriminating in violation of such laws. Yet the ABA took the position that these laws were no defense.

A recent executive order attempts to stop accreditors from pressuring schools into violating the law. The ABA has also recently temporarily suspended enforcement of its diversity standards. But an executive order can be revoked at the stroke of a pen by the next President. And, given the ABA's past enthusiasm for race and sex preferences, it will not be surprising if it decides to revive its diversity standards should the political winds shift.

All in all, legislation is necessary as a more permanent solution to the problem. PLF's report contains model language that Congress could use. Legislation on this topic has also recently been introduced by Senator Jim Banks (R-Indiana).

Some state supreme courts, including Texas, Florida, and Ohio, are considering whether they should continue to rely on the ABA as an accreditation authority. During their deliberations, they should consider the ABA's history of exerting unlawful pressure toward discrimination on law schools, as documented in PLF's recent report.

The post New Pacific Legal Foundation Report Based on 50 Freedom of Information Requests to Top Law Schools: ABA Accreditation Frequently Nudges Law Schools Toward Illegal Discrimination appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: July 30, 1956

7/30/1956: Congress enacted a resolution, declaring that the motto of the United States is "In God we Trust." The Supreme Court declined to grant review in Newdow v.Congress, which considered the constitutionality of that motto.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: July 30, 1956 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Wednesday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Wednesday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

July 29, 2025

[Paul Cassell] The Justice Department Powerfully Defends Alina Habba's Appointment as Acting U.S. Attorney for New Jersey

[The Department's filing makes a strong case that Habba's appointment is proper. The courts should quickly reject defendants' challenge to the appointment. ]

Over the last several days, Steve Calabresi and I have been posting about the President's authority to appoint acting and interim U.S. Attorneys. See posts here, here, and here. We both generally believe the President's appointment (through his Attorney General) of Alina Habba to be Acting U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey is valid.

As I mentioned in my post earlier today, a criminal defendant in New Jersey has challenged Habba's appointment. And late this afternoon, the Justice Department filed its strong response. Here is the Department's introduction explaining why Habba is validly appointed and, in any event, the defendant is not entitled to attack the prosecution:

First, Ms. Habba is validly serving as the Acting United States Attorney. The Attorney General properly appointed her as the First Assistant United States Attorney; the First Assistant can serve as the Acting United States Attorney under the Federal Vacancies Reform Act when that office is vacant; and the President properly removed as United States Attorney an individual whom the District Court for the District of New Jersey purported to appoint.

Second, and in any event, even were Ms. Habba not eligible to serve as the Acting U.S. Attorney, there would be no basis for dismissing this indictment or prohibiting everyone in the U.S. Attorney's Office for the District of New Jersey (USAO-NJ) from participating in this prosecution. At minimum, Ms. Habba has been properly appointed as a Special Attorney to the Attorney General of the United States and directed to supervise the USAO-NJ. Pursuant to that appointment alone, she could still supervise this case—which was initiated by a validly empaneled grand jury and a Senate-confirmed U.S. Attorney—and the Assistant U.S. Attorneys assigned to it can continue prosecuting it under their own delegated authority from the Attorney General, subject to supervision by both Ms. Habba and Senate-confirmed officials in Main Justice, including the Attorney General and the Deputy Attorney General.

Unsurprisingly given my defense of her appointment, I find this brief to be highly persuasive. I did want to highlight the detailed response in the brief to the New Jersey defendant's claim (endorsed by some law professors) that the fact that Ms. Habba had previously been nominated to serve as the U.S. Attorney blocked her appointment. This specific statutory argument about the Federal Vacancies Reform Act (FVRA) is based on 5 U.S.C. § 3345(b)(1). The Department's response this point seems particularly powerful:

Although Ms. Habba did not previously serve as the First Assistant, she is not subject to § 3345(b)(1)'s bar because she is not presently nominated to serve as United States Attorney in a permanent capacity (and was not even so nominated at the time of her appointment as First Assistant).

The purpose of subsection (b)(1) is to prevent the President from circumventing the Senate's advice-and-consent function by installing a pending nominee for an office on an acting basis before the Senate can act on the nomination. See NLRB v. SW General, Inc., 580 U.S. 288, 295–96 (2017) (tracing history of provision). Accordingly, "if a first assistant is serving as an acting officer under [subsection (a)(1)], he must cease that service if the President nominates him to fill the vacant [Presidentially-appointed, Senate confirmed] office," or else withdraw from nomination. Id. at 301; see Hooks v. Kitsap Tenant Support Servs., Inc., 816 F.3d 550, 558 (9th Cir. 2016) ("Subsection (b)(1) thus precludes someone from continuing to serve as an acting officer after being nominated to the permanent position, unless he or she had been the first assistant for ninety days of the prior year.").

Subsection (b)(1) therefore presupposes a current nomination to an office that is pending before the Senate. Nothing in the FVRA, however, suggests that the mere fact of a past nomination for an office—withdrawn by the President and never considered or acted upon by the Senate—forever bars an individual from serving in that capacity on an acting basis. The statute precludes a person from serving as an acting officer once "the President submits a nomination of such person to the Senate for appointment to such office," 5 U.S.C. 3345(b)(1)(B) (emphasis added); it does not say that the person is barred from such service if the President ever submitted a nomination in the past, or continues to be barred once a nomination is withdrawn. See, e.g., Dole Food Co. v. Patrickson, 538 U.S. 468, 478 (2003) (explaining that a statutory provision "expressed in the present tense" requires consideration of status at the time of the regulated action, not before); Nichols v. United States, 578 U.S. 104, 110 (2016) (same). Indeed, a lifetime ban of that sort would have no logical relationship to the distinct separation-of-powers problem that Congress sought to address in subsection (b)(1): Congress's desire to protect its ability to consider and act upon a pending nomination for an office can hardly be served if no nomination is pending.

In light of this strong response, the defendant's specific and narrow statutory challenge to Ms. Habba's authority should be—and likely will be—quickly dismissed. A quick dismissal will be helpful to the administration of justice, because the challenge to Habba's authority is reportedly leading to some other cases being put on hold.

Of course, there are other broader issues at play in the appointment of interim and acting U.S. Attorneys, as my earlier posts discuss.

The post The Justice Department Powerfully Defends Alina Habba's Appointment as Acting U.S. Attorney for New Jersey appeared first on Reason.com.

[Irina Manta] Privacy Breaches, Dating App Safety, and AI - Oh My!

[How We Ended up with the Tea App Breach and What Are the Alternatives]

It was revealed a few days ago that the Tea app that allows women to rate male daters and run them through a "Catfish Finder AI" got hacked. Over 72,000 selfies, ID pictures, and other user images were apparently exposed in the process. Then it turned out that users' direct messages about sensitive topics such as abortions or cheating were revealed as well.

It's easy to dismiss this incident as another instance of a private company failing to safeguard user data properly. But it's worth asking first how we got here. Safety apps such as Tea and social media groups that seek to protect people from dating app abuse have been labeled "vigilante justice." Why do we have this highly imperfect system of reporting abusive dating app behavior, however, along with tenuous frameworks of data storage?

In short, because current dating app use, in a largely unregulated environment, is dangerous yet often unavoidable if one wants to find a romantic partner. Some data suggests that one in three women who have used dating apps have experienced sexual assault as a result. As I discuss in my scholarship (such as in my forthcoming article "Tinder Backgrounds" here), the law currently does little to address or prevent this and other related forms of abuse.

So is it any wonder that dating app users, including especially women, have resorted to self-help in the form of online gossip networks? Most of the writers who attack these types of self-help offer little by way of alternatives and seem mainly focused on the privacy harms to the men being posted at the expense of the physical and other harms to the women who have few other options to warn others. As I argue in "Tinder Backgrounds," this will not change until we create mandated mechanisms on dating apps that would--unlike the Tea app--ensure that the data being collected for purposes of identification and background checks is stored in keeping with recognized safety standards.

Hence, the Tea app breach is actually illustrative of the exact opposite of what it seems at first. In addition to all the other harms it creates, the current lack of regulation of dating apps is hurting privacy rather than helping it.

The post Privacy Breaches, Dating App Safety, and AI - Oh My! appeared first on Reason.com.

[Paul Cassell] The Attorney General Can Put Her Own Legal Team in Place—through U.S. Attorneys in New Jersey and Elsewhere

[Acting through through Section 546, or temporarily through the Federal Vacancies Reform Act, the Attorney General is entitled to appoint U.S. Attorneys for the District of New Jersey and all other federal judicial districts. If done properly, such appointments preempt any need for judges to appoint U.S. Attorneys. But it is important that the President submit a nominee for the position for Senate confirmation.]

Recently questions have swirled around how the Attorney General can appoint an "interim" U.S. Attorney before the Senate has acted to permanently fill the position, with a focus on the New Jersey position that has been filled temporarily by Alina Habba. A statute (28 U.S.C. 546) allows the Attorney General to make an interim appointment for 120-days, but then provides that the district judges in the district can step in to make a further appointment. On Saturday, VC co-blogger Steve Calabresi questioned the constitutionality of this statute, contending that such cross-branch appointments by the Judiciary of an Executive Branch officer violates separation of powers principles. Yesterday, I rebutted his argument, explaining why the Constitution's Appointments Clause allows Congress to set up this approach to interim appointments. And, if my constitutional analysis of § 546 is correct, then only statutory questions remain about how an interim U.S. Attorney can be appointed.

But Ms. Habba very recently resigned her position as "interim" U.S. Attorney to become "acting" U.S. Attorney. Is this permissible? Over the last 24 hours, this seemingly technical academic issue has suddenly assumed tremendous practical importance. As the New York Times is reporting in a lead story, "New Jersey Criminal Cases Screech to a Halt as [N.J. U.S. Attorney] Habba's Authority is Challenged." In this post, I address the current controversy surrounding the authority of the New Jersey U.S. Attorney. And, more broadly, I also attempt to set out the relevant statutory framework and policy issues surrounding appointments to the important U.S. Attorney positions.

To make a long story short, in my view, Ms. Habba is lawfully the acting U.S. Attorney in the District of New Jersey, at least for a short period of time, via the somewhat circuitous route of having been appointed by the Attorney General to be the First Assistant in the Office, and then being elevated to the Acting U.S. Attorney via the Federal Vacancies Reform Act (FVRA), 5 U.S.C. §§ 3345 et seq. But one problem with this approach is that, while seemingly authorized by statute, it appears to have the potential to deprive the Senate of its opportunity to vote on the U.S. Attorney selection for a lengthy period of time. Rather than relying on the FVRA, a more straightforward path for the Attorney General is to simply appoint an "interim" U.S. Attorney every 120 days, under § 546—while the President simultaneously nominates that person to be the permanent U.S. Attorney. Indeed, Ms. Habba could now be reappointed as the interim U.S. Attorney and, simultaneously, her nomination resubmitted to the Senate. Under this approach, the Senate has an opportunity to speak to nomination, while at the same time the Attorney General is entitled to put her own legal team in place in the important U.S. Attorney positions around the country.

To set the stage for this question, it is useful to recount that the U.S. Attorneys for each of the 94 federal judicial districts (such as the District of New Jersey) are the top federal prosecutors. The U.S. Attorneys are political appointees, acting under the direction of the Attorney General (currently, of course, Attorney General Pam Bondi). Because of the importance of U.S. Attorneys, they are nominated for their positions by the President and then must be confirmed (or disapproved) by the Senate.

In recent years, following the election of a new President, it has become common for existing U.S. Attorneys to quickly resign and be replaced, particularly where (as happened in the last election) the new President is from a different political party than his predecessor. That replacement process can take time, as the new President must identify an appropriate replacement, and then nominate the replacement for the Senatorial advice and consent process.

In New Jersey, following the election of President Trump, in December the Biden-appointed U.S. Attorney for New Jersey (Philip R. Sellinger) resigned. As the Trump Administration transitioned into office and after Attorney General Bondi was confirmed, on March 24, 2025, Alina Habba was appointed as the "interim" U.S. Attorney for New Jersey. And President Trump submitted her nomination to become the permanent U.S. Attorney.

As I have discussed, the statute governing interim U.S. Attorneys (28 U.S.C. § 546) contains a 120-day time limit on Attorney General appointments. Since March 24, Alina Habba had been serving in that interim position, while her nomination to become the permanent U.S. Attorney was pending before the Senate. In the past, it has been common for interim U.S. Attorneys to remain in their positions until the Senate has acted, one way or the other, on their nominations. But over the last week or so, as Ms. Habba's interim, 120-day term was drawing to a close, the district judges for the District of Jersey entered a brief order declining to extend her term. Instead, citing their authority under § 546(d), the judges appointed Ms. Habba's First Assistant (Desiree Leigh Grace) to the interim U.S. Attorney position.

The Trump Administration quickly responded to keep Ms. Habba in the position. First, the President withdrew Ms. Habba's nomination to be the U.S. Attorney, a step apparently designed to clear the path for using the FVRA. And then Attorney General Bondi appointed Ms. Habba to be the First Assistant in that U.S. Attorney's Office. This appointment meant that automatically, by operation of law, Ms. Habba became the Acting U.S. Attorney for the District for up to the next 210 days, pursuant to the Federal Vacancies Reform Act (FVRA), 5 U.S.C. §§ 3345 et seq. The Attorney General also removed the First Assistant (Ms. Grace) from her (potential) court-appointed interim U.S. Attorney position.

After reading this complex procedural history, some might wonder whether this case is some sort of New Jersey machination, unlikely to recur elsewhere. But as Calabresi recounted in his original post, this issue is not confined to The Garden State. Senate Democrats are reportedly slow-walking the President's U.S. Attorney nominees, with negotiations on-going to break the impasse. As of a few days ago, only a dozen nominees have moved past a preliminary committee vote and not a single nominee has received a confirmation vote on the Senate floor—even though the Presidential election was more than eight months ago. So issues regarding the appointment process for the 93 U.S. Attorneys, whether it be on an "interim," "acting," or permanent basis, have tremendous practical importance. (For an excellent recent article differentiating among the three categories, see James A. Heilpern, Interim United States Attorneys, 28 George Mason L. Rev. 187 (2020) (calling the current situation "a mess").)

The recent use of the Federal Vacancies Reform Act to fill the New Jersey slot might serve as a roadmap for the Trump Administration to follow in other districts. But the FVRA's scope is debated. And, more important, the Act's constitutionality has also been seriously questioned. For example, Justice Thomas has concluded that "[c]ourts inevitably will be called upon to determine whether the Constitution permits the appointment of principal officers pursuant to the FVRA without Senate confirmation." N.L.R.B. v. SW Gen., Inc., 580 U.S. 288, 318 (2017).

In the last few days, these seemingly arcane appointment issues have come to a head in New Jersey. A federal criminal defendant in New Jersey has already challenged Habba's appointment under the FVRA, arguing that the statute explicitly prohibits individuals whose nomination have been submitted to the Senate from serving in an acting capacity for the same office. Let's consider this narrow statutory argument.

The relevant provisions in the FVRA provide:

(a) If an officer of an Executive agency … whose appointment to office is required to be made by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, dies, resigns, or is otherwise unable to perform the functions and duties of the office—

(1) the first assistant of the office such officer shall perform the functions of the duties of the office temporarily in an acting capacity …

(b)(1) … a person may not serve as an acting officer for an office under this section, if—

(A) during the 365-day period preceding the date of the death, resignation, or beginning of inability to serve, such person—

(i) did not serve in the position of first assistant to the office of such officer; or

(ii) served in the position of first assistant to the office of such officer for less than 90 days; and

(B) the President submits a nomination of such person to the Senate for appointment to such office.

5 U.S.C. § 3345 (emphasis added).

According to this defendant, this last (highlighted) provision "explicitly prohibits" Habba from serving as the Acting U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey because the President had months earlier submitted her nomination to the Senate for that same position—even though the President has now withdrawn her nomination. The defendant's argument is joined by Georgetown law professor Steve Vladeck, who argues on social media that the "President can't appoint the 'first assistant' to be the acting officer if her nomination was 'submitted,' not just if it's 'pending.' Withdrawing the nomination doesn't change the fact that it was submitted."

I believe Habba is properly serving as the Acting U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey, by operation of the FVRA, at least for a short period of time. The key question being litigated in her case is whether a person is permanently barred from serving as an acting U.S. Attorney after the President "submits a nomination of such person" to the Senate. But the statute's plain language does not create a disability after a nomination "was submitted," as Vladeck suggests. Instead, the statute uses the present tense: a disability exists when the President "submits a nomination." Under standard, recommended principles of legislative drafting, the present tense is used "to express all facts and conditions required to be concurrent with the operation of the legal action," as Bryan Garner explains in his excellent treatise, Garner's Dictionary of Legal Usage 536 (3d edition 2011) (emphasis added). Now that the President has withdrawn Habba's nomination—i.e., is no longer submitting her nomination—the condition of her nomination being submitted to the Senate is no longer concurrent with the legal actions she is taking as the U.S. Attorney.

This interpretation of the statute makes common sense. Presumably Congress did not want a person to serve as the "acting" U.S. Attorney while that same person's nomination had been submitted to the Senate. Before that person can act as the U.S. Attorney, that person should go through the normal Senate confirmation process. But the fact that the President had earlier submitted a nomination should not create a disability for temporary service as the acting U.S. Attorney—months, years, or even decades after an earlier nomination that the Senate never acted upon.

Moreover, it makes no difference to Ms. Habba's ability to serve as the "acting" U.S. Attorney that she had previously served as the "interim" U.S. Attorney under § 546. The Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) has opined that the two statutes (the FVRA general provisions on "acting" officials and § 546's specific provisions on "interim" U.S. Attorneys) "can operate in sequence," with an official first being appointed under one statute and then later under the other.

Nor does it make any difference how the vacancy that Ms. Habba is filling arose. The FVRA drafters apparently intended to allow the filling of even self-created vacancies. During a floor debate, both Senators Thomas and Byrd stated that vacancies created by terminations were examples of § 3345(a)'s "otherwise unable to perform the functions and duties of [such] office" language. See Guidance on Application of Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998, at 61 (1999) (noting that during a floor debate Senators Thomas and Byrd stated that firing was an example of not being able to perform one's duties under 5 U.S.C. § 3345(a) (discussed in Note, Justin C. Van Orsdol, Reforming Federal Vacancies, 54 Georgia L. Rev. 297, 309 (2019)). In fact, this broad language was specifically chosen to "make the law cover all situations" because, under Doolin Security Savings Bank v. Office of Thrift Supervision, the original Vacancies Act's language did not apply to officers who were fired. See 139 F.3d 203, 207 (D.C. Cir. 1998) ("[I]t becomes clear that the [original Vacancies Act] contemplates only the death, resignation, illness or absence of someone appointed to the position by the President." (emphasis added)), superseded by statute, Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998, Pub. L. No. 105–277, discussed in 144 Cong. Rec. S12810, S12823 (daily ed. Oct. 21, 1998) (statement of Sen. Thompson), as summarized in Note, supra, at 308 & nn.69-71.

For all these reasons, I believe that Habba is properly serving today as the acting U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey, at least temporarily for a short time until the Attorney General decides who should be nominated to fill that spot permanently. And any question will be resolved relatively quickly. The statutory issue is already being reviewed by the courts and is simply a question of reading several sentences in the FVRA. Nonetheless, the ramifications are significant, as the likely remedies for a determination that Habba has been improperly appointed is new trials and proceedings. See Heilpern, supra, at 210-11 (citing Lucia v. SEC, 585 U.S. 237 (2018)).

But a broader issue is that the FVRA maneuver has forced the President to withdraw Habba's nomination, not only depriving the President of the chance to have his selected nominee considered but also the Senate of an opportunity to vote on her confirmation. This absence of a possible Senate confirmation vote raises the constitutional question identified by Justice Thomas above—i.e., whether the FVRA is an impermissible abrogation by the Senate of its advice and consent function. There are also other statutory questions about the FVRA that this (already lengthy) blog post does not consider, such as whether the FVRA's general provisions for all Executive Branch positions effectively cross-references and makes applicable § 546's more specific provisions for filing vacant U.S. Attorney's positions in particular. See 5 U.S.C. § 3347(a)(1)(A). Indeed, it is interesting to observe that the FVRA was intended to limit Executive Branch power, and is now apparently being used as an expansion of the Attorney General's power. Cf. Ross E. Wiener, Inter-Branch Appointments After the Independent Counsel: Court Appointment of United States Attorneys, 86 Minn. L. Rev. 363, 439 n.352 (2001).

Like Calabresi, I believe that the President (and his Attorney General) need not resort to the complexities of the general provisions of the FVRA to put his chosen U.S. Attorneys into place. Instead, I believe that the Attorney General posses more straightforward authority under § 546 (specifically governing appointment of U.S. Attorneys) to make, first, an "interim," 120-day appointment while a Senate confirmation is pending. And then, if the Senate has failed to Act to make the interim appointment a permanent one, the Attorney General can make successive interim appointments until the Senate makes its decision. If the Attorney General is able to use that specific statute to appoint the President's nominees as "interim" U.S. Attorneys, there is no need for the Attorney General to resort to the FVRA to put in place "acting" U.S. Attorneys. And the Senate's role is respected if the interim U.S. Attorney's nomination is simultaneously provided to the Senate for its decision.

In evaluating the Attorney General's authority to appoint interim U.S. Attorneys under § 546, it is useful to begin with the statute's text:

(a) Except as provided in subsection (b), the Attorney General may appoint a United States attorney for the district in which the office of United States attorney is vacant.

(b) The Attorney General shall not appoint as United States attorney a person to whose appointment by the President to that office the Senate refused to give advice and consent.

(c) A person appointed as United States attorney under this section may serve until the earlier of—

(1) the qualification of a United States attorney for such district appointed by the President under section 541 of this title; or

(2) the expiration of 120 days after appointment by the Attorney General under this section.

(d) If an appointment expires under subsection (c)(2), the district court for such district may appoint a United States attorney to serve until the vacancy is filled. The order of appointment by the court shall be filed with the clerk of the court.

Under the statute, the Attorney General can obviously put the President's U.S. Attorney nominees in place initially for 120 days. Historically, this time would have usually been sufficient to then have the nominee confirmed (or rejected) by the Senate. But as noted above, in the current contentious political environment, confirmations within 120 days are, apparently, no longer the norm.

So if the 120-day time period expires, the obvious question becomes: what happens next? One approach the Attorney General can take is to simply reappoint the previous interim U.S. Attorney to a new, successive 120-day term. On this issue, I agree with Calabresi's conclusion that successive appointments are permissible. But whereas Calabresi seemed to hinge his argument on the unconstitutionality of § 546(d), I believe that the statute is constitutional and also permits the Attorney General to make such successive appointments. To be sure, my interpretation may render the judicial appointment provisions in the statute only rarely applicable. But the statute's text and the Constitution's structure support this conclusion. And the bottom line result makes perfect sense: The President, working through his Attorney General, is able to put his legal team in place to execute his policies.

In years past, the Justice Department has seemingly taken differing positions on whether such successive appointments are consistent with the statute. In November 1986, shortly after Congress adopted § 546 in its current form, then-Deputy Assistant Attorney General Sam Alito explained in a memorandum to the Department's Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys that a second appointment by the Attorney General would be inappropriate because "[t]he statutory plan discloses a [c]ongressional purpose that after the expiration of the 120-day period further interim appointments are to be made by the court rather than by the Attorney General." See Ross E. Wiener, Inter-Branch Appointments After the Independent Counsel: Court Appointment of United States Attorneys, 86 Minn. L. Rev. 363, 402 (2001) (describing the memorandum).

But in a later interpretation, the Office of Legal Counsel (then headed by Chuck Cooper) explained that "[i]t could be argued that, after the removal by the President of a court appointed United States Attorney, the power to appoint an interim United States Attorney shifts back to the Attorney General, because the court's power of appointment is conditioned on the expiration of a 120-day appointment by the Attorney General." Memorandum from Charles J. Cooper, Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel, to Arnold I. Burns, Deputy Attorney General (Apr. 15, 1987) (quoted in Wiener, supra, at 402 n.179). [Disclosure: In 1987, I worked for DAG Burns as an Associate Deputy Attorney General. I don't recall working on this issue.] Interestingly, from what I can tell from the description of these two memoranda (from Alioto and Cooper), it was not the Department's position during the Reagan Administration that § 546(d) was unconstitutional.

As suggested by the Cooper memorandum, a straightforward strategy to avoid judicial appointments would be for the interim U.S. Attorney to be removed (or resign) on, let's say, 119 days into the 120-day term. Thereafter, because the U.S. Attorney position would be "vacant" under § 546(a), the Attorney General would be entitled to appoint an interim U.S. Attorney. Nothing in the statute blocks the Attorney General from appointing the same person who was previously the interim U.S. Attorney (assuming that the interim U.S. Attorney had not been rejected by the Senate). And because the first 120-day term never "expired" under § 546(c)(2), no occasion for a judicial appointment would arise.

This strategy appears to be consistent with the statute's plain language. But as then-Deputy Attorney General Alito suggested, the "congressional purpose" might have been to turn appointments over the Judiciary after the initial 120-day period.

Alito's congressional purpose argument from 1986 is supported by subsequent developments surrounding the statute. As I noted yesterday, in 2006 Congress enacted complete Justice Department control over interim U.S. Attorneys for an unlimited period of time. See USA PATRIOT Improvement and Reauthorization Act of 2005, Pub. L. No. 109-177, tit. V, sec. 502, 120 Stat. 246 (2006). But shortly thereafter, controversy arose about how certain U.S. Attorney's had been removed from their offices. And, the next year (2007), Congress responded by enacting legislation—sometimes identified as the "Preserving U.S. Attorney Independence Act"—which reenacted the pre-existing law. The legislation restored the 120-day limit and judicial appointment provision that remain in the law today (as quoted above).

The 2007 congressional re-enactment of § 546(d) could possibly be viewed as blocking successive appointments. The House Report on the interim appointment of U.S. Attorneys critically observed that the Congressional Research Service (CRS) had "identified several instances where the Attorney General made successive interim appointments pursuant to [the pre-2006 version of] section 546 of either the same or different individuals. For example, one individual received a total of four successive interim appointments." H. Rep. 110-58 at 6; see also House Hearing at 138 (CRS statement). And the issue of successive appointments led to at least one court case considering the issue, with the case upholding the Attorney General's second, successive U.S. Attorney appointment. See In re Grand Jury Proceedings, 671 F.Supp. 5 (D. Mass. 1987).

So Congress must have been aware of the successive appointments issue. Indeed, the CRS warned Congress that if it simply put back in place the pre-existing language, it could "give rise to a dynamic whereby the advice and consent function of the Senate could be avoided to a significant degree even under the prior version of section 546."

But did Congress actually do anything to block successive appointments? No. In (re)enacting § 546, all Congress did was (re)adopt the earlier language. Compare Pub. L. 110-34, section 2 (June 14, 2007) with Public L. 99-646, section 69 (Nov. 10, 1986).

Thus, it seems that Congress left the door open for successive appointments of an interim U.S. Attorney, even appointments of the same person. As the CRS presciently warned, that was not only a theoretical possibility but the actual practice under the previous language. If Congress wanted to change that practice, it needed to change the statute's language. While its is arguable that the statute's "purpose" was to effect change, the plain language controls. And the statute's plain language is the same as the earlier law, where successive interim appointments had been made.

Supporting this argument about the permissibility of successive appointments, as Calabresi notes, is the fact that the 120-day term limit does not bar reappointment if done by district court judges. If judges outside the Executive Branch have the power to reappoint the same person to an Executive Branch position, it is hard to see why the same power does not extend to the Attorney General, who is inside the Executive Branch.

Finally, it is worth considering the argument that § 546(d) strips the Executive Branch of any authority to make an interim U.S. Attorney appointment after the 120 days expires. In just the last two days, a New Jersey criminal defendant has advanced this argument. But the argument immediately founders on the statute's text. Judicial authority to appoint an interim U.S. Attorney only exists "until the vacancy is filled." 28 U.S.C. § 546(d). By definition, a successive appointment "fills" the vacancy. And note that the statute requires only that the vacancy be filled, not that the Senate has confirmed a new U.S. Attorney.

If my reading of § 546 is correct, then the Attorney General can effectively prevent any judicial appointment of interim U.S. Attorneys through successive appointments. Some may argue that this is a flaw in the statute (or in my reading of the statute). But it is useful to step back and ask whether judicial appointments of (interim) U.S. Attorneys are good or bad?

For reasons that I explained yesterday, I don't believe that it is unconstitutional for Congress to provide for judicial appointment of U.S. Attorneys. But for all the reasons that Calabresi explained earlier in arguing for the statute's unconstitutionality, it is certainly unusual to have a cross-branch appointment by the Judiciary of an Executive Branch officer. In some extreme cases, such cross-branch appointments might even be unconstitutional. The Supreme Court has held that Congressional action to vest the appointment power in the Courts would be improper if there was some "incongruity" between the functions normally performed by the Courts and the performance of the duty to appoint. Morrison v. Olson, 487 U.S. 654, 675–76 (1988) (citing Ex parte Siebold, 100 U.S. 371, 398 (1879)).

More important, even if such cross-branch appointments are typically constitutional, they are often unwise—as arguments by Calabresi and others suggest. Judicial appointments of Executive Branch officials seem fraught with political intrigue, with the potential to embroil judges in political controversy. The recent New Jersey judicial appointment controversy illustrates this point. As Ms. Habba's interim appointment from a Republican Attorney General was expiring, mostly Democratic nominated judges considered whether to extend her appointment. When the judges quickly decided to pick someone else a few days before the expiration of Habba's term, the Deputy Attorney General took to X to criticize the move as political:

The district court judges in NJ are trying to force out @USAttyHabba

before her term expires at 11:59 p.m. Friday. Their rush reveals what this was always about: a left-wing agenda, not the rule of law. When judges act like activists, they undermine confidence in our justice system. Alina is President Trump's choice to lead—and no partisan bench can override that.

To be sure, the judges may have good reasons—even nonpartisan good reasons—for declining to extend Habba's appointment. I don't take a position on her merits. But assessing the judges' reasons would quickly connect to political controversies that judges are poorly suited to handle. And the formal mechanism that the judges have for making an interim appointment—in this case a terse, two-sentence court order—is not well-suited to quell any controversy, as the reasons underlying the selection are unarticulated.

Even if the judges articulated their reasons for appointments of U.S. Attorneys more extensively, such appointments have the potential to cast doubt on the impartiality of the judiciary. When the judiciary selects an interim U.S. Attorney, are the judges trying to find the "best" prosecutor—that is, the prosecutor most likely to obtain a conviction? Should the judges consult with the Justice Department to see who would be the "best fit" to run the office and implement the President's policies?

The point is that it is an incongruous to have judges select an interim U.S. Attorney, when thereafter those same judges will hear cases on a regular basis brought by their appointee. This perception may not be enough to violate formal separation of powers constraints, as the First Circuit concluded in United States v. Hilario, 218 F.3d 19 (1st Cir. 2000). Indeed, judges regularly select defense attorneys in federal criminal cases without constitutional impediment. Id. at 29. And judges may be forced to select a prosecutor "when the Executive Branch defaults." Id. (citing Young v. United States ex rel. Vuitton et Fils,481 U.S. 787, 800–01 (1987) (approving court appointment of a prosecutor for a contempt proceeding)). But when there are no case-specific reasons in play and all that is left is a simple choice between the Executive Branch selecting an Executive Branch officer and the Judicial Branch doing so, it makes sense to prefer the intra-branch selection.

One last point remains to be considered: even when judges appoint an interim U.S. Attorney, can the President (acting through his Attorney General) remove that person from office, creating a vacancy that he can then fill. Here again, the answer appears to be straightforward: yes, the President has removal power. Nothing in § 546(d) blocks the normal removal power of the President over his subordinates. Indeed, in an adjacent statute to § 564—§ 541— Congress provides that "[e]ach United States Attorney is subject to removal by the President." 28 U.S.C. § 541(c). If a judicially appointed U.S. Attorney is somehow immunized from this general statutory removal power, such immunity would need to appear in a statute. Indeed, many of the Supreme Court cases that Calabresi cites (and that I discussed yesterday) underscore how Presidential removal power is important to the proper functioning of the Executive Branch. See, e.g., Seila Law LLC v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 591 U.S. 197 (2020). And on this removal issue, the First Circuit has specifically held that "the President may override the judges' decision and remove an interim United States Attorney." United States v. Hilario, 218 F.3d 19, 27 (1st Cir. 2000) (citing 28 U.S.C. § 541(c)).

To be sure, there may be situations where recognizing Executive Branch removal power would defeat the very purpose of a judicial appointment. For example, as Young v. United States ex rel. Vuitton et Fils suggests, once the Executive Branch has declined to support a judicially initiated contempt prosecution, the judiciary must have the power to move the prosecution forward without Executive Branch interference. But interfering with a specific prosecution for case-specific reasons is different than removing and replacing an interim U.S. Attorney for appropriate institutional reasons to implement the President's policies. Ultimately, as an institutional matter, the selection of a U.S. Attorney operating within the Executive Branch rests in the hands of the Executive Branch.

Contrary to the foregoing arguments, James Heilpern has suggested that it is impermissible for the President to simply be able to remove and reappoint a U.S. Attorney not to his liking. Heilpern argues that, "[b]y doing so ad nauseum, the President could effectively sidestep the appointment mechanism Congress thought proper"—i.e., the selection by district court judges at the end of the 120-day interim term. Heilpern, supra, at 226. But Heilpern's argument argument essentially ignores Congress's specific statutory authorization for the President to remove U.S. Attorneys. And Heilpern's excellent article, written in 2020, did not have the benefit of recent Supreme Court decisions reinforcing the President's removal power, including most recently Trump v. Wilcox. Under current decisions, the President's removal power over interim U.S. Attorneys seems very likely to be upheld.

For all these reasons, the Attorney General has ultimate control over the selection of U.S. Attorneys. But having dispatched the statutory concerns in the FVRA and § 546, one last important and overarching constitutional question remains to considered: What about the Senate's advice and consent function. Through the maneuvers just discussed, are the President and his Attorney General able to simply and perpetually bypass the Senate confirmation process for U.S. Attorneys?

To answer this question, I think it is important to circle back to point that I made yesterday (in apparent agreement with Calabresi). Both of us went down the path of analyzing the statutory appointments processes on the premise that someone temporarily in an "interim" U.S. Attorney's position was an "inferior" officer of the United States, whose appointment could be specified by Congress under the Appointments Clause, Article II, Section 2. But the issue is a complex one. James Heilpern has helpfully reviewed the issue at some length, concluding that it remains an "open constitutional question." Heilpern, supra, at 210-11. At some point, a series of successive temporary appointments of a U.S. Attorney might well functionally convert an "interim" U.S. Attorney into the permanent U.S. Attorney—in turn raising the question of whether that person needs to be Senate confirmed before taking action.

In my view, one way out of this potential dilemma is to treat an "interim" U.S. Attorney as an inferior officer only in a situation where the Senate confirmation process has been put in play through a Presidential nomination for a permanent appointment. For example, while President Trump's nomination of Alina Habba was pending before the Senate, it was perfectly reasonable to treat her (non-Senate confirmed) interim appointment as an inferior officer, since the appointment was merely temporary pending a Senate decision. If the Senate confirmed Habba, then the advice and consent function had been carried out. And if the Senate rejected Habba, then Habba's temporary interim appointed immediately ended, by operation of law. See 28 U.S.C. § 546(b). In this way, the Senate's constitutional role is honored.

For this reason, Attorney General appointments of interim U.S. Attorneys—along with simultaneous submission of the person to the Senate—should be the preferred approach rather than maneuvering through the FVRA. As noted at the beginning of this post, Justice Thomas (and others) have raised serious constitutional questions about whether the FVRA constitutes an impermissible abrogation by the Senate of its advice and consent function. Moreover, the FVRA itself specifies that the First Assistant may perform the duties of (in this case) the U.S. Attorney only "temporarily." 5 U.S.C. § 3345. This temporary time period is specified in the FVRA next provision as 210 days or "once a first or second nomination for the office is submitted to the Senate, from the date of such nomination for the period that the nomination is pending in the Senate." 5 U.S.C. § 3346. In this way, the FVRA also attempts to protects the Senate's advice and consent function by making an "acting" appointment contingent, at least to some degree, on the Senate having the opportunity to vote to confirm (or reject) a permanent replacement. But the FVRA maneuver is subject to constitutional attack where the First Assistant is not subject to Senate review as she discharges the duties of the U.S. Attorney for 210 days (or, perhaps, even longer, if successive appointments of new First Assistants are made).

To circle back to the current situation in New Jersey, the Attorney General would be acting within her rights to simply reappoint Habba as the interim U.S. Attorney for New Jersey under § 546, accompanied by the President renominating Habba to serve as the permanent U.S. Attorney. The Senate would then have the opportunity to vote up or down on Habba, protecting the advice and consent function. Leaving Habba as the acting U.S. Attorney under the FVRA might invite a constitutional challenge to the entire Act, as Justice Thomas has suggested.

One last note: There may be situations where the Attorney General wishes to confer with local district judges on making selections, or even to allow district judges to make such selection after expiration of the 120-day interim period under § 546. And in all events, the Attorney General may find it politically wise to consult with Senators in that state about whom to select. But nothing in existing law forbids the Attorney General from making a different choice and proceeding on her own initiative to make interim appointments accompanied by proffering a nominee for Senate confirmation hearings.