Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 59

August 7, 2025

[Luke Goodrich] Religious Hiring and Expressive Association

[Does the First Amendment freedom of expressive association protect religious hiring?]

Thanks to Eugene for inviting me to guest-blog about my forthcoming article, Religious Hiring Beyond the Ministerial Exception. My first post laid out how appellate courts are grappling with an important question that will likely reach the Supreme Court soon: What legal protections do religious groups have when they fire a non-minister (like a secretary or janitor) for rejecting the group's religious teachings on sex or marriage? I then explored two potential protections: Title VII's religious exemption and the First Amendment's church-autonomy doctrine.

Today I'll argue that a different First Amendment protection—the right of expressive association—also protects religious hiring by religious groups.

What Is Expressive Association?

Unlike the church-autonomy doctrine, the right of expressive association is not rooted in the Religion Clauses; it is rooted in the Speech Clause (or, as some cogently argue, the Assembly Clause). The basic idea is that freedom of speech necessarily entails the right to gather with others—to associate—to engage in speech. The right of expressive association, then, protects the right to associate with others (or not to associate) for expressive purposes.

The leading case is Boy Scouts v. Dale. There, the Boy Scouts dismissed a scoutmaster for being a "gay rights activist," and the scoutmaster sued, alleging his dismissal was illegal sexual-orientation discrimination. But the Supreme Court rejected his claim, explaining that the First Amendment freedom to associate "presupposes a freedom not to associate," and that requiring the Scouts to retain the scoutmaster would unconstitutionally "force the [Scouts] to send a message … that [it] accepts homosexual conduct as a legitimate form of behavior."

Dale requires courts to address two questions when considering an expressive-association defense: (1) whether the group "engage[s] in some form of expression," and (2) "whether the forced inclusion" of the individual "would significantly affect the [group's] ability to advocate public or private viewpoints." And if the answer to both questions is yes, the First Amendment prohibits the forced association, absent proof that the forced association satisfies strict scrutiny—i.e., serves "compelling state interests" that cannot be achieved through "significantly less restrictive" means.

Expressive Association for Religious Groups

Dale provides a strong framework for protecting religious groups. Suppose, for example, a religious school dismisses its math teacher for entering a same-sex marriage. Under Dale's first prong, a religious school, of course, "engage[s] in some form of expression": teaching and propagating a religious faith, including (often) views on marriage.

Second, forcing a religious school to employ a teacher who violates its view of marriage would "significantly affect the [school's] ability" to instill that view in its students. As the Second Circuit explained: "'It would be difficult,' to say the least, for an organization 'to sincerely and effectively convey a message of disapproval of certain types of conduct if, at the same time it must accept members who engage in that conduct."

Another Second Circuit panel tried to cut back on this ruling, suggesting that forcing religious groups to hire dissenters doesn't significantly inhibit their expression unless propagating a particular viewpoint is the "very mission" of the organization. But this argument stands in tension with Dale. There, opposing homosexuality wasn't the "very mission" of the Boy Scouts; indeed, the Boy Scouts' "central tenets" arguably did not "say[] the slightest thing about homosexuality." Yet the Court held that "associations do not have to associate for the 'purpose' of disseminating a certain message in order to be entitled to the protections of the First Amendment." Instead, courts must "give deference" to an association's view of "the nature of its expression" and "what would impair [that] expression."

Under Dale, then, our hypothetical teacher's employment-discrimination claim would likely be barred unless it satisfied strict scrutiny.

Counterarguments

Some courts have ruled that forcing religious groups to employ dissenters does satisfy strict scrutiny—that it advances a compelling interest in eradicating discrimination, and there is no less-restrictive means of accomplishing this interest absent forced association.

But this argument faces several hurdles. First, it contradicts the strict-scrutiny analysis in Dale. There, the Court likewise considered if the government's interest in eliminating discrimination was sufficiently compelling to justify forced association with the scoutmaster. And it rejected the strict-scrutiny defense. The Court said that however "compelling" the government's "interest in eliminating discrimination" based on "sexual orientation," that interest "d[id] not justify such a severe intrusion on … freedom of expressive association." So too with religious groups.

Second, to satisfy strict scrutiny, it is not enough to assert a "broadly formulated" interest in "ensuring equal treatment" based on sexual orientation. Instead, the government must show a specific, compelling interest in denying a religious exemption to "particular religious claimants." The Supreme Court has never found this standard satisfied when a religious claimant has sought an exemption from a sexual-orientation discrimination law. Rather, all five cases presenting the issue (Hurley, Dale, Masterpiece, Fulton, and 303 Creative) came out in favor of a religious exemption.

Third, Title VII's ban on sex discrimination is particularly unlikely to satisfy this analysis, because it is shot through with other exemptions. Most notably, among others, it includes an exemption for every employer with fewer than fifteen employees—which exempts approximately 80% of all private employers nationwide, employing tens of millions of Americans. The government cannot have a compelling interest in forcing religious groups to hire religious dissenters, when it allows millions of secular businesses to discriminate for any reason with impunity.

Given the shaky strict-scrutiny defense, some courts have floated another idea: the right of expressive association doesn't apply to employment disputes at all. But this argument fails as a matter of both precedent and principle.

The leading precedent invoked for this argument is Hishon v. King & Spalding, which held that a large law firm lacked an expressive-association right to exclude women from partnership. But Hishon doesn't say expressive association is categorically inapplicable to employment disputes. Rather, Hishon addressed and rejected an expressive-association defense on the merits, reasoning that the large law firm there had not shown "how its ability" to express "ideas and beliefs" would be "inhibited" by letting a woman make partner. If anything, that suggests employers that can make such a showing would be protected—and many lower courts since Hishon have so held.

Nor would excluding employment from the right of expressive association make sense as a matter of constitutional principle. The Supreme Court routinely applies First Amendment defenses to employment relationships and other commercial disputes—e.g., the ministerial exception applies to employment suits by ministers; church autonomy applies to collective bargaining over employment in religious schools; the Free Exercise Clause applies to antidiscrimination lawsuits against for-profit businesses; the Free Speech Clause applies to antidiscrimination lawsuits against commercial web designers, the sale of violent video games to minors, and the placement of paid, commercial ads in newspapers. There is no reason that expressive association, alone among First Amendment rights, would be categorically inapplicable to employment.

Conclusion

In short, expressive association offers another potential defense for religiously motivated hiring practices. Under Dale, the defense turns primarily on whether a religious group "engage[s] in some form of expression," and whether forced inclusion of a religious dissenter "would significantly affect the [group's] ability to advocate public or private viewpoints." And many religious groups will be able to make that showing—particularly given Dale's admonition that courts must "give deference" to an association's view of "the nature of its expression" and "what would impair [that] expression."

With several potential defenses available, however, how should courts handle these claims? Should one defense be preferred over others? If so, which one and why? Tomorrow's post (the final one!) will attempt to sketch out an answer to these questions.

The post Religious Hiring and Expressive Association appeared first on Reason.com.

August 6, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Ban on Gender Transition Procedures for Minors Doesn't Violate Parental Rights

From Poe v. Drummond, decided today by the Tenth Circuit (Judge Joel Carson, joined by Judges Harris Hartz and Gregory Phillips), upholding an Oklahoma statute that "prohibits healthcare providers from 'provid[ing] gender transition procedures' to anyone under eighteen."

Parent Plaintiffs assert a substantive Due Process claim arguing that SB 613 impinges on their fundamental right to make medical decisions for their minor children….

Parents have the right "to make decisions concerning the care, custody, and control of their children," which includes "to some extent, a more specific right to make decisions about the child's medical care," But we and the Supreme Court have held that parents do not have an absolute "right to direct a child's medical care." …

We … have consistently held that individuals do not have an affirmative right to specific medical treatments the government reasonably prohibits. We have held that although patients have a fundamental right to refuse treatment, the "selection of a particular treatment … is within the area of governmental interest in protecting public health." Thus, the government has the "authority to limit the patient's choice of medication," whether the patient is an adult or a child.

The parent-child relationship does not change our reasoning, and to conclude otherwise would allow parents to "veto legislative and regulatory polices about drugs and surgeries permitted for children." LAlthough parents have authority over their children's medical care, no case law "support[s] the extension of this right to a right of parents to demand that the State make available a particular form of treatment." In fact, the state's interest in a child's health may "constrain[] a parent's liberty interest in the custody, care, and management of her children." So our Nation does not have a deeply rooted history of affirmative access to medical treatment the government reasonably prohibited, regardless of the parent-child relationship….

As for gender transition procedures specifically, healthcare providers onlyrecently began providing gender transition procedures for minors. The medical community traditionally limited gender transition treatments to adults.In 1979, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health ("WPATH") published the first standard of care ("Standard") for treating gender dysphoria and recommended that healthcare providers only administer hormone and surgical procedures on legal adults.In 1998, WPATH revised their Standard to include puberty blockers and hormones to those older than 16 if the patient met certain criteria but still recommended that "the administration of hormones to adolescents younger than age 18 should rarely be done."

Not until 2001 did WPATH revise their Standard to allow for puberty blockers as soon as pubertal changes began but still recommended that hormone therapy not occur until the age of 16. In 2012, WPATH revised their Standards to permit puberty blockers and hormonal therapy from the early stages of puberty. This recent development in the medical field regarding gender transition procedures for minors shows that our Nation does not have a deeply rooted tradition in providing gender transition procedures to minors….

Seems correct to me; here's what I wrote about the subject June 30, quoting a Sixth Circuit decision that reached the same result:

Some people have asked: Why aren't state statutes limiting youth gender medicine treatments violations of parental rights (given that they apply even when the parents ask for the treatment for their children)? The answer, I think, is that the Court hasn't generally recognized a constitutional right to get forbidden medical procedures for oneself, much less a right to get them for one's children. I think Sixth Circuit Judge Jeffrey Sutton correctly summarized the legal rules in L.W. v. Skrmetti (which the Supreme Court just declined to review):

There is a long tradition of permitting state governments to regulate medical treatments for adults and children. So long as a federal statute does not stand in the way and so long as an enumerated constitutional guarantee does not apply, the States may regulate or ban medical technologies they deem unsafe.

Washington v. Glucksberg puts a face on these points…. The Court reasoned that there was no "deeply rooted" tradition of permitting individuals or their doctors to override contrary state medical laws. The right to refuse medical treatment in some settings, it reasoned, cannot be "transmuted" into a right to obtain treatment, even if both involved "personal and profound" decisions….

Abigail Alliance hews to this path. The claimant was a public interest group that maintained that terminally ill patients had a constitutional right to use experimental drugs that the FDA had not yet deemed safe and effective. As these "terminally ill patients and their supporters" saw it, the Constitution gave them the right to use experimental drugs in the face of a grim health prognosis. How, they claimed, could the FDA override the liberty of a patient and doctor to make the cost-benefit analysis of using a drug for themselves given the stark odds of survival the patient already faced? In a thoughtful en banc decision, the D.C. Circuit rejected the claim. The decision invoked our country's long history of regulating drugs and medical treatments, concluding that substantive due process has no role to play….

As in these cases, so in this one, indeed more so in this one. "The state's authority over children's activities is broader than over like actions of adults." A parent's right to make decisions for a child does not sweep more broadly than an adult's right to make decisions for herself….

Parental rights do not alter this conclusion because parents do not have a constitutional right to obtain reasonably banned treatments for their children. Plaintiffs counter that, as parents, they have a substantive due process right "to make decisions concerning the care, custody, and control of their children." At one level of generality, they are right. Parents usually do know what's best for their children and in most matters (where to live, how to live, what to eat, how to learn, when to be exposed to mature subject matter) their decisions govern until the child reaches 18. But becoming a parent does not create a right to reject democratically enacted laws. The key problem is that the claimants overstate the parental right by climbing up the ladder of generality to a perch—in which parents control all drug and other medical treatments for their children—that the case law and our traditions simply do not support. Level of generality is everything in constitutional law, which is why the Court requires "a 'careful description' of the asserted fundamental liberty interest."

So described, no such tradition exists. The government has the power to reasonably limit the use of drugs, as just shown. If that's true for adults, it's assuredly true for their children, as also just shown. This country does not have a custom of permitting parents to obtain banned medical treatments for their children and to override contrary legislative policy judgments in the process. Any other approach would not work. If parents could veto legislative and regulatory policies about drugs and surgeries permitted for children, every such regulation—there must be thousands—would come with a springing easement: It would be good law until one parent in the country opposed it. At that point, either the parent would take charge of the regulation or the courts would. And all of this in an arena—the care of our children—where sound medical policies are indispensable and most in need of responsiveness to the democratic process.

I have argued that there should be a constitutional right to choose certain medical treatments for oneself in narrow circumstances (basically when the person is terminally ill, and seeks a possibly life-saving though unproven treatment). But even if I'm right, that would be quite a narrow right; and in any event, the Abigail Alliance en banc opinion, described in the excerpt above, rejected even that narrow argument.

Zach West, Audrey A. Weaver, and Will Flanagan of the Oklahoma Attorney General's office represent the state in the Tenth Circuit case.

The post Ban on Gender Transition Procedures for Minors Doesn't Violate Parental Rights appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Vulgar Signs Condemning City Official, ~1200 Feet from Official's Home, Constitutionally Protected

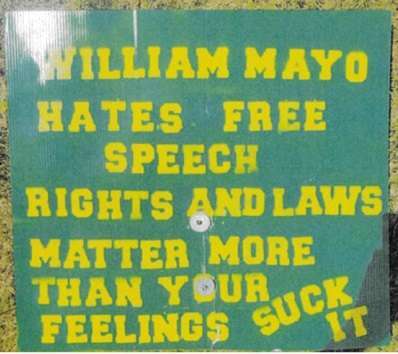

One of the signs (from the court opinion).

One of the signs (from the court opinion).

Some excerpts from today's long decision by Judge Stacey D. Neumann in Roussel v. Mayo (D. Me.):

Plaintiff Joseph F. Roussel sued the city manager of Old Town, Maine, various Old Town police officers, and the Piscataquis County Sheriff for allegedly violating his First Amendment rights. This case began as a disagreement over the masking policy at the Old Town City Hall during the COVID-19 pandemic. But it developed into an acrimonious dispute, and the situation deteriorated further when Mr. Roussel did two things that are the subject of this Order: First, while passing by the city manager's lakefront house on his friend's boat, Mr. Roussel shouted expletives at the city manager. Second, Mr. Roussel posted strongly worded and expletive-laden signs on the side of the private road leading to the city manager's house. In response, the city manager enlisted Piscataquis County Sheriff Robert Young to serve Mr. Roussel with a cease harassment notice.

The court largely allowed Roussel's First Amendment claim to go forward:

Mr. Roussel was with his friends—who lived in the area—on their boat on Schoodic Lake, in Lake View Plantation, Maine. As they happened to pass by a particular house on the lakeshore, one of Mr. Roussel's friends told him that Mr. Mayo lived there. Mr. Roussel saw two people seated on the porch near the lakeshore at Mr. Mayo's home, and he assumed that one of them was Mr. Mayo. Mr. Roussel shouted at the people on Mr. Mayo's porch, "fuck you, try trespassing me from here you tyrant piece of shit," referencing the City Hall trespass warning from the previous fall [related to the disagreement about masks].

Mr. Mayo was, in fact, sitting on his porch with a friend when Mr. Roussel passed by Mr. Mayo heard someone shouting at him but did not recognize who it was….

A week later, … Mr. Roussel drove to Lake View Plantation to meet with friends who lived there. Mr. Roussel spoke with them about posting signs on the roads nearby. After he left his friends' house, he posted … signs near Mr. Mayo's home, along Hancock Road and Railroad Bed Road. The signs displayed the following language in all capital letters:

FUCK YOU WILLIAM MAYO WILLIAM MAYO HATES FREE SPEECH RIGHTS AND LAWS MATTER MORE THAN YOUR FEELINGS SUCK IT SOMETIMES WHEN YOUR A TYRANT AT WORK THEY FIGURE OUT WHERE YOU LIVE AND SCOTT WILCOX CANT HELP WILLIAM MAYO SUPPORTS BIDEN ANOTHER SHIT BAG THAT HATES FREEDOM THE CONSTITUTION MATTERS MORE THAN YOUR LIMP DICK FREEDOM OF SPEECH MATTERS MOST WHEN YOU DONT LIKE IT FUCK YOU WILLIAM MAYO EAT A BAG OF DICKSThe closest sign was located approximately 1,200 feet from Mr. Mayo's house, posted on a utility pole near the primary entrance into the subdivision. None of the signs were posted on the final access road to Mr. Mayo's property. Mr. Roussel himself never went closer than within 1,000 feet of Mr. Mayo's home when he posted the signs. Nor did Mr. Roussel confront—or even see—Mr. Mayo in person when he posted the signs….

The court held that Roussel's speech was constitutionally protected:

When Mr. Roussel passed by Mr. Mayo's home on the lake, he shouted at Mr. Mayo's porch, "fuck you, try trespassing me from here you tyrant piece of shit." That speech does not fall into any of the "well-defined and narrowly limited classes" of exceptions to the First Amendment's strong free speech guarantee. Although the language used is crass and derogatory, it does not constitute incitement, defamation, or obscenity. Nor is it a true threat of violence. Indeed, the Supreme Court has held that the First Amendment protects the right to shout at public officials, City of Houston, Tex. v. Hill (1987), and to use profanity, see Cohen v. California (1971) (jacket bearing the words 'Fuck the Draft' was protected speech); Hess v. Indiana (1973) (shouting "we'll take the fucking street again" while police were attempting to clear a protest was protected). Accordingly, the content of Mr. Roussel's speech on the lake is protected.

Sheriff Young argues Mr. Roussel's speech on the lake is unprotected because it was "one-to-one" speech between Mr. Roussel and Mr. Mayo. In Sheriff Young's view, speech directed from one person at another in private lacks First Amendment protection. As an initial matter, there is no such categorical exception for one-to-one speech. Sheriff Young relies exclusively on a case in which the court denied habeas relief to a petitioner convicted for violating a domestic protection order. McCurdy v. Maine (D. Me. 2020). As the court recognized in that case, the Supreme Court has not "squarely addressed the issue." See also Saxe v. State Coll. Area Sch. Dist. (3d Cir. 2001) (Alito, Circuit Judge) ("There is no categorical 'harassment exception' to the First Amendment's free speech clause.").

In any event, I need not decide the issue here as undisputed facts in the record demonstrate that Mr. Roussel did not engage in one-to-one speech. Mr. Roussel was on the boat with at least one other friend, and Mr. Mayo was on the shore with at least one other person….

As with the language shouted from the boat, albeit crude and offensive, the speech on Mr. Roussel's signs does not constitute incitement, defamation, obscenity, or any other type of speech outside the scope of First Amendment protection.

Sheriff Young briefly suggests that the sign stating, "SOMETIMES WHEN YOUR A TYRANT AT WORK THEY FIGURE OUT WHERE YOU LIVE AND SCOTT WILCOX CANT HELP" could be considered a true threat. However, Sheriff Young does not sufficiently develop this argument in his motion. He does not cite to any case law supporting his argument, explain how the signs are threatening, or demonstrate that Mr. Roussel subjectively understood the threatening nature of his speech. While both Sheriff Young and Mr. Roussel discuss Mr. Roussel's subjective intent in their depositions, Sheriff Young does not develop this testimony into a legal argument in his briefs. Therefore, because Sheriff Young does not make any reasoned argument as to whether the content of Mr. Roussel's signs constitutes an unprotected true threat, I consider that argument waived.

The court concluded that "a reasonable jury could find that Sheriff Young's decision to issue a cease harassment notice was content based":

First, Sheriff Young testified at his deposition that he explained over the phone to Mr. Roussel that he issued the cease harassment notice "because of the signs, the nature of the signs, the language that was used, the fact that he went on private property and posted it when he didn't have permission to do so." When asked whether his concerns were mostly about the language used in the signs, Sheriff Young responded, "The language was of concern, yes." Second, Sheriff Young testified that he would not have issued any order to Mr. Roussel over the language in some of the signs, but the language in others prompted him to do so. As to one sign, he testified, "I would not issue a summons just for that sign." When asked if one of the other signs would constitute disorderly conduct on Mr. Roussel's part, and thereby justify the cease harassment notice, Sheriff Young testified "I think it could be." Third, Sheriff Young testified about his interpretation of one of Mr. Roussel's signs: "Well, my sense of that … is that he was trying to convey to Mr. Mayo that he was in a place now where the chief of police in Old Town can't help him …."

Additional facts in the record, "if believed, could lead a reasonable jury to conclude" Sheriff Young issued the cease harassment order "because of disagreement with [Mr. Roussel's] message." There were other signs on the same roads, but none prompted Sheriff Young to take any action. For example, there were multiple non- political signs concerning the road's use. ECF No. 72-8 (signs reading "Caution"; "25 MPH Please Slow Down"; "Ride Right on Pavement"; "ATVs Please Slow Down or Lose the Privilege of Using this Road"; and numerous directional signs with arrows pointing to snowmobile trails, and food and lodging nearby). In Reed, the Supreme Court held that a town ordinance distinguishing between "Temporary Directional Signs," "Political Signs," and "Ideological Signs" was facially content based. That holding applies here, too. The distinction between non-political signs (like those directing traffic) and political signs (like Mr. Roussel's coarse criticism of Mr. Mayo) is content based….

And the court concluded that the restriction on Roussel's speech likely couldn't be justified under the "strict scrutiny" applicable to content-based restrictions:

Sheriff Young hints at the governmental interest in residential privacy. In his view, Mr. Roussel placed his signs on the roads close enough to Mr. Mayo's home to infringe on Mr. Mayo's privacy. Sheriff Young cites to Frisby v. Schultz (1988), in which the Supreme Court upheld a content-neutral ban on targeted residential picketing, to support his argument. There, anti-abortion protestors staged pickets directly in front of the home of a doctor who performed abortions. The Court held that picketing in front of a private residence infringes on the resident's privacy interest; therefore, the government can regulate such speech in a content-neutral manner because the captive audience "cannot avoid the objectionable speech." That such speech "inherently and offensively" intrudes on the special privacy of the home justifies regulation.

Frisby is distinguishable in two ways. First, its reasoning is limited to content- neutral regulations. As the Court explained, "[t]he ordinance also leaves open ample alternative channels of communication and is content neutral. Thus, largely because of its narrow scope, the facial challenge to the ordinance must fail." Here, by contrast, where a reasonable jury could conclude Sheriff Young's conduct was content based, Frisby's reasoning does not apply by its own terms. Second, while the parties here disagree as to the precise location of the signs on the roadside, the undisputed record demonstrates Mr. Roussel did not post any signs directly outside Mr. Mayo's home. The closest sign was approximately 1,200 feet from Mr. Mayo's house. Mr. Roussel himself never went closer than 1,000 feet to Mr. Mayo's home when he posted the signs. Nor did he confront—or even see—Mr. Mayo in person when he posted the signs. Based on these undisputed facts, the signs did not inherently intrude on Mr. Mayo's privacy in his home. Treating Frisby as permitting the government to restrict speech beyond the home's immediate surroundings would be inconsistent with its focus on picketing "narrowly directed at the household."

Additionally, while there is certainly a government interest in "protecting the well-being, tranquility, and privacy of the home," the Supreme Court has held only that it rises to a "significant government interest." That is a lower standard than the compelling interest required to justify a content-based restriction on speech. Therefore, when considering the state interest in protecting residential privacy beyond the limited context of Frisby's facts, the Supreme Court has held that content-based restrictions on protests are unconstitutional. Because a content-based speech restriction "cannot be upheld as a means of protecting residential privacy for the simple reason that nothing in the content-based … distinction has any bearing whatsoever on privacy," and a reasonable jury resolving disputed facts could find Sheriff Young issued a content-based speech restriction, summary judgment is inappropriate.

The court thus allowed the case to go forward.

The post Vulgar Signs Condemning City Official, ~1200 Feet from Official's Home, Constitutionally Protected appeared first on Reason.com.

[Keith E. Whittington] On the Politics of University Autonomy

[My new paper thinking through the political calculus of independent universities]

Public and private universities are currently being scrutinized by politicians and political activists in ways that they have not been in many years. Moreover, government officials at both the state and federal level are intervening in the internal affairs of universities in ways that are nearly unprecedented.

These political interventions were predictable (indeed, I was among those predicting them), but they pose extraordinary challenges to traditional ways in which universities have operated and to the future of higher education in America. The normative and public policy questions surrounding greater political supervision of universities are difficult and real.

In a new paper I take a more empirical and positive political theory approach to our current situation. There is an extensive literature on the politics of "independent" government institutions, from the judiciary to bureaucracies to central banks to international organizations. The conceptual apparatus and logic of those models can be turned toward thinking about the political conditions and political boundaries of university autonomy from government interventions.

This paper on "The Bounded Independence of American Universities" is, I believe, the first effort to develop an empirical model of university independence. It emphasizes that the lessons from other contexts apply to universities as well. No matter how normatively attractive an independent judiciary or an independent university might be, institutional independence is a political construct and must be maintained through political effort. And "independent" institutions are always politically vulnerable to being rendered less independent if they become too politically costly. Strategic university leaders should recognize that university autonomy is politically contingent and cannot simply be assumed. Unfortunately, university faculty and administrators have become forgetful that university independence, like judicial independence, rests on political foundations.

From the abstract:

State universities are agents of the state. As such, they are subject to the same political dynamics as other state institutions. There are normative reasons for preferring that some state institutions enjoy a substantial degree of independence from ordinary political forces, but there are significant political challenges to achieving such independence. Universities are no different. Achieving and preserving some degree of independence from political control for universities is an ongoing political task, and the independence of universities from political influence and intervention is bounded and contingent.

And from the conclusion:

The fact that university autonomy is politically bounded and conditional does not mean that independence is not real. It just means that there are limits. Those limits are not themselves fixed, but they are not necessarily under the control of the university. Universities can do what they can to demonstrate their societal value. They can persuade critical stakeholders that continued autonomy is important to generating that societal value. Like all agents, they must convince their principals that they are faithful agents whose interests largely align with those of the principals and who exercise their discretion in a prudential fashion. They must cultivate allies who share an interest in the relative autonomy of universities and can exert political pressure on their behalf. The conditions for university autonomy must be cultivated over time, and sometimes the terms of institutional independence have to be renegotiated to better conform to the political environment within which universities operate.

The post On the Politics of University Autonomy appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Kash Patel Awarded $100K Compensatory + $100K Punitive Damages Default Judgment in Libel Suit Against Substacker Jim Stewartson (Filed in 2023)

Back in June 2023, now-FBI-Director Kash Patel sued Jim Stewartson for libel, alleging that Stewartson had falsely claimed that Patel "attempted to overthrow the government," "planned 1/6," was "guilty of sedition," was a "Kremlin asset," and paid people to "lie to congress"; some of the allegations were also about Patel's Kash Foundation. Stewartson didn't appear to defend himself, so eventually, in March 2025, Patel moved for default judgment.Yesterday, Judge Andrew Gordon (D. Nev.) granted the motion:

As a result of the entry of default [triggered by Stewartson's failure to defend himself], "the factual allegations of the complaint, except those relating to the amount of damages, [are] taken as true." Stewartson's statements are defamatory as to Kashyap Patel. And the complaint alleges that at least one of these statements was impliedly directed at the Kash Foundation, Inc. and "directly and proximately caused the Kash Foundation significant damages …." Thus, liability is established.

The plaintiffs' motion offers scant evidence of harm or damages to either plaintiff. Even if damages are presumed, there must be some evidence to support a monetary award. The plaintiffs' expert report offers only conclusory statements about reputational damage and lost Foundation donors, with almost no reference to specific instances to support those. For example, the reports states that Mr. Patel's "image has been deeply hurt by the defamation accusing him of working against the government, corruption, and crime. Apart from the business already lost, this impacts future opportunities and relationships." But the report offers no examples of "business already lost" and how Mr. Patel's image was hurt by the defamatory statements themselves, as opposed to the myriad non-defamatory attacks Mr. Patel has suffered as a result of being a public figure.

To the contrary, after the defamatory statements, Mr. Patel was confirmed by the United States Senate as Director of the F.B.I. Clearly his reputation was not significantly sullied by the defamatory statements. Thus, minimal, if any, reputational rehabilitation damages are needed.

Nevertheless, Stewartson's statements were defamatory and caused presumed damages. Falsely stating as fact that a public figure "attempted to overthrow the government," planned the January 6 insurrection, was a "Kremlin asset," and paid people to "lie to [C]ongress" inflicts real injuries, personally and professionally. I award Mr. Patel $100,000 in compensatory damages.

Likewise, there is almost no concrete evidence of harm or damages suffered by the Foundation. All of the defamatory statements were directed at Mr. Patel individually. The Foundation contends it was harmed "by implication." The plaintiffs' expert states that Mr. Patel's "reputational damage has affected the ability of Kash Foundation to continue carrying out its social impact and affected donor and client relationships." But there is only proffer of a possible harm to the Foundation: according to Andrew Ollis (whose affiliation with the Foundation is not described) "[a]t [l]east 7 donors, with a total donation/gift of $25,000+ have stopped giving since the incident, with the defamation being a highly probable cause of the same because the narrative directly contradicts the benevolence of donating to a charitable cause." There is no indication which "incident" (i.e., which defamatory statement) is referenced and why that statement (or the series of statements) is "a highly probable cause" of the lost donations, as opposed to other reasons. Nor does the report explain why those seven donors account for "$25,000+" in lost donations when the average donation to the Foundation is $47.

Nevertheless, I will accept the $25,000 figure as a reasonable estimate of the harm to the Foundation, given that there is no other evidence of any affected donor or relationship or any impact on the Foundation's ability to carry out its mission. I award the Foundation $25,000 in compensatory damages.

The plaintiffs also request an award of punitive damages. Such an award is appropriate here, in part to deter Stewartson and others from engaging in defamation. Factual criticism of, and opinions about, public figures are protected speech and must be tolerated. This nation was founded on "a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials."

But defamatory falsehoods made with actual malice are not protected, even if directed at public officials. The complaint and the motion adequately demonstrate Stewartson acted with malice.

I consider "three guideposts" when evaluating punitive damages: "(1) the degree of reprehensibility of the defendant's misconduct; (2) the disparity between the actual or potential harm suffered by the plaintiff and the punitive damages award; and (3) the difference between the punitive damages awarded by the jury and the civil penalties authorized or imposed in comparable cases." … Here, the harm was economic, the plaintiffs were not financially vulnerable, and the conduct involved repeated defamatory statements infused with malice. Considering these factors, I award Mr. Patel $100,000 in punitive damages and the Foundation $25,000 in punitive damages.

The post Kash Patel Awarded $100K Compensatory + $100K Punitive Damages Default Judgment in Libel Suit Against Substacker Jim Stewartson (Filed in 2023) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Alleged "QAnon John"'s Libel Lawsuit Against Anti-Defamation League Settles, ADL Removes Page with Accusations

I wrote last year about Judge Reed O'Connor's opinion in Sabal v. Anti-Defamation League (N.D. Tex.), which declined to dismiss the lawsuit. Friday, the case settled; the Backgrounder: QAnon page and the Lone Star Report page seems to now have Sabal's name removed, and the Glossary of Extremism and Hate entry for Sabal has apparently been deleted. Here's an excerpt from last year's opinion:

Plaintiff John Sabal started his own business, The Patriot Voice, to organize conservative political events. The purpose of these events is to showcase "pertinent and dynamic speakers, whose messages are timely and relevant." These events also "feature speakers of every color and creed, including those of the Jewish faith." … Sabal contends that ADL defamed him….

The first ADL publication at issue is entitled, "Backgrounder: QAnon" (the "Backgrounder"). The Backgrounder includes two references to Sabal. The first states that "several aspects of QAnon lore mirror longstanding antisemitic tropes, and multiple QAnon influencers, including … QAnon John (John Sabal) have been known to peddle antisemitic beliefs." [The Backgrounder specifically refers to "the antisemitic trope of blood libel, the false theory that Jews murder Christian children for ritualistic purposes." -EV] The second states that "[i]n October 2021, several elected officials and candidates spoke at the Patriot Double Down conference hosted in Las Vegas, Nevada by antisemitic QAnon influencer John Sabal (QAnon John)." The words "spoke at the Patriot Double Down conference" link to an article published by the Arizona Mirror reporting on "some extremely antisemitic imagery," such as visuals of Hitler and the Star of David superimposed against a picture of the 9/11 attacks….

The second publication is ADL's "Glossary of Extremism and Hate" ("Glossary"), which "provides an overview of many of the terms and individuals used by or associated with movements and groups that subscribe to and/or promote extremist or hateful ideologies." The Glossary entry at issue here provides that "John Sabal, also known as 'QAnon John,' is a QAnon influencer who runs The Patriot Voice website, which he uses to advertise QAnon-related conferences. These conferences, the first of which was held in May 2021, have showcased the mainstreaming of QAnon and other conspiracy theories." …

The third ADL publication at issue is the report entitled, "Hate in the Lone Star State: Extremism & Antisemitism in Texas" (the "Lone Star Report"), which "explore[d] a range of extremist groups and movements operating in Texas and highlights the key extremist and antisemitic trends and incidents in the state in 2021 and 2022." The Lone Star Report identifies Sabal in connection with a Dallas conference:

Over the last few years, Texas has been at the heart of several notable QAnon events and incidents. The state has been home to multiple QAnon-themed conferences, highlighting the mainstreaming of QAnon and other conspiracies among conservative communities and the GOP. The most notable was "For God & Country: Patriot Roundup," which took place on Memorial Day weekend 2021. Organized by John Sabal, known online as "QAnon John" and "The Patriot Voice," the event featured then-Congressman Louie Gohmert (R-TX), then-Texas GOP chair Allen West, Lt. General Michael Flynn, attorney and conspiracy theorist Sidney Powell and various QAnon influencers. During the event, Michael Flynn seemingly endorsed a Myanmar-style coup in the U.S., although he has since backtracked on his remarks….

The Complaint alleges that the Backgrounder is defamatory by falsely stating that Sabal has been "known to peddle antisemitic beliefs, including the "antisemitic trope of blood libel." … From a review of the Backgrounder, the Complaint plausibly contends that a reasonable reader would view the statement "known to peddle antisemitic beliefs" as a factual assertion about Sabal. True, some courts have found calling a person "antisemitic" to be a non-actionable opinion. However, Texas law makes clear that this determination depends on context, which may reveal that an opinion instead functions as a factual assertion. Bentley v. Bunton (Tex. 2002) (holding that calling someone "corrupt" was actionable defamation based on the challenged publication's context because a reasonable reader could view the statement as an assertion of fact). Taking as true the allegations that Sabal has never expressed or endorsed antisemitic views, ADL's statements seem possible to verify: either Sabal has made such statements or he has not, making ADL's assertions capable of being proven false.

To accept Defendant's argument that a reasonable viewer would not attribute the blood libel conspiracy to Sabal would require the Court to ignore illustrative context in the Backgrounder. Contextual clues plausibly suggest to a reasonable reader that Sabal factually believes and endorses this antisemitic belief. For instance, the Backgrounder's description of the blood libel conspiracy immediately follows the explicit mention of four "QAnon influencers" by name. One of those names is Sabal. ADL identifies these influencers as those who are "known to peddle antisemitic beliefs." The textual proximity of the blood libel theory appears to function as an example of one such antisemitic belief. A reasonable reader could conclude that ADL mentioned Sabal and the other three names to provide examples of people who espouse the specific antisemitic belief of blood libel….

The Complaint also plausibly shows that ADL's statements in the Backgrounder carry defamatory impact…. ADL's accusation that Sabal espouses abhorrent beliefs is plausibly harmful to his reputation and occupation—just like calling someone "corrupt" in certain contexts carries the same potential harm, Bentley—because such allegations do not carry "innocent" meaning….

Viewing the entire context—and not merely the individual statements—the Backgrounder implies "materially true facts from which a defamatory inference can reasonably be drawn." …

Sabal's Complaint next alleges that ADL's inclusion of his name as an entry in the Glossary of Extremism is provably false and defamatory because it implies Sabal "is a dangerous, extremist threat and even a criminal." Published by ADL's Center on Extremism, the entry links to a mission statement advising readers that ADL "track[s] extremist trends, ideologies and groups across the ideological spectrum" and its "staff of investigators, analysts, researchers and technical experts strategically monitor, expose and disrupt extremist threats."

ADL argues that the Glossary entry is not defamatory because it includes entries for many persons beyond Sabal. As such, a description about one person does not necessarily apply to others. But the Glossary has one overarching theme shared by all entries: extremism. The Glossary even states that "many of the terms and individuals used by or associated with movements and groups that subscribe to and/or promote extremist or hateful ideologies." Although ADL contends that calling someone an extremist is not defamatory, the type of extremism featured in the Glossary is of a highly criminal and depraved nature. Combined with the mission statement, the Glossary's context appears convey factual assertions about persons with Glossary entries rather than mere opinion.

To a reasonable reader, the Glossary may objectively indicate that all persons on this list are similarly dangerous and abhorrent. In his Complaint, Sabal pleads that Defendant wrongly likened him to "murderous Islamic terrorists—such as Nidal Hasan, Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, and ISIS—notable white supremacists—such as David Duke—and racist mass-murderers—such as Dylann Roof (the Charlestown church shooter), Brenton Tarrant (the Christchurch shooter), and Patrick Cruscius (the El Paso Walmart shooter)." In the full context of the Glossary, it was plausibly defamatory to call Sabal an extremist by including him alongside obviously dangerous terrorists and mass murderers. Cf. Bentley (holding that, while the term "corrupt" is normally used as opinion, it can be used as a statement of fact in certain contexts). Further revealing the plausibility of this defamatory implication is the absence of additional information about Sabal in the Glossary to counter the likelihood that a reasonable reader would understand this publication as a factual assertion about Sabal….

Similar to the Glossary and the Backgrounder, the third allegedly defamatory statement is found in the Lone Star Report's reference to Sabal's 2021 "QAnon-themed" event when discussing antisemitic incidents, hate crimes, and terrorist activities in Texas. ADL's sole argument is that most of the statements in this publication are not attributable to Sabal. But a contextual review of the entire Lone Star Report tells a different story. By including Sabal alongside antisemites and extremists in a report highlighting "[h]ate [c]rime [s]tatistics" and "[e]xtremist [p]lots and [m]urders," a reasonable reader could objectively understand the publication's context as making a factual assertion that Sabal's events are associated with such criminal activity. Further evincing this potential factual imputation is the Lone Star Report's hyperlink to Sabal's Glossary entry. As with the publications discussed above, inclusion of Sabal by name in a report about criminal extremism and antisemitism is "obviously hurtful to [his] reputation" in Texas and carries the potential to injure his "office, profession, or occupation."

Therefore, the Court determines that Sabal pleads sufficient facts at this stage to show plausible defamation based on the Lone Star Report because it factually implies Sabal is a particular type of extremist who engages in, or is otherwise responsible for, dangerous criminal activity….

Looking at each [of the above statements], individually and in context, it is plausible that each is provably false. That is not to preliminarily determine that each statement is, in fact, false. Instead, the Court merely recognizes that evidence could be produced to prove the falsity of the challenged statements, which leads to the conclusion at this stage that they are factual assertions rather than opinion. Similarly, these statements plausibly carry defamatory significance due to the lack of innocent meaning that is hurtful to Sabal's business and reputation. Therefore, the Court concludes at this stage that Sabal plausibly alleges defamation based on statements contained in three of the four ADL publications….

The court deferred deciding whether Sabal was a limited-purpose public figure, and thus had to show that the ADL knew that the statements were false or likely false:

The requisite degree of fault that flows from Sabal's status is a question of law for the Court to ultimately decide. In candor, this is a close call. And the chaotic state of case law on limited-purpose public figures only further complicates this question. See, e.g., Berisha v. Lawson (2021) (Gorsuch, J., dissenting from denial of certiorari) (lamenting that "the very categories and test this Court invested and instructed lower courts to use in this area—'pervasively famous,' 'limited purpose public figure'—seem increasingly malleable and even archaic when almost anyone can attract some degree of public notoriety in some media segment"). As a result, the Court determines that it is appropriate to instead evaluate whether Sabal is a limited-purpose public figure at a later stage in these proceedings with the benefit of additional briefing and development of the factual record. Indeed, there are times when "[i]ssues pertaining to [a plaintiff's] defamation claims are better resolved at the summary judgment stage."

But the court rejected a separate part of Sabal's claim, which rested on ADL's Congressional testimony, because testimony is absolutely immune from defamation liability.

The post Alleged "QAnon John"'s Libel Lawsuit Against Anti-Defamation League Settles, ADL Removes Page with Accusations appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Columbia Ph.D. Student #TheyLied Libel Suit Over Allegations of Stalking and Abuse Can Go Forward

From Thursday's decision by N.Y. trial judge Dakota Ramseur in Talbert v. Tynes, rejecting defendants' motion to dismiss:

In his complaint, Talbert alleges that Tynes, an acquaintance and former Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University, made various posts to Twitter in November 2021 concerning their interactions as students that accused him of stalking and of being generally abusive and manipulative towards women. More specifically, Tynes' tweets responded to a photograph shared by third party Derecka Purnell, a prominent scholar and author on Black History, that identified Talbert as being "in the tradition of black liberation theology" and as "legendary James Cone's last student." Tynes reposted the image with the caption, "If I speak, Twitter will suspend me," followed by two tweets: "Not the abolitionist [Purnell] with my stalker," and "That man has harmed multiple women and is abusive and manipulative, but congrats on his dissertation, I guess."

Talbert contends that these statements were false, published with actual malice, and caused reputational, emotional, and professional harm.

In support of her … motion to dismiss, Tynes submitted an affidavit describing the context of her prior interactions with him and the alleged basis for her public tweets. In it, she explains that they both attended Columbia University as graduate students between 2017 and 2020, enrolled in a Spring 2018 seminar titled DuBois@150, and participated in a shared study group.

According to her, during the seminar, Talbert would sit across from her, stare at her, and move physically closer without speaking. On or about April 25, 2018, while walking to class, Talbert allegedly followed her, remarked, "that was one of three creepy ways I thought to approach you," and showed her photos he had taken of her walking. Tynes further alleges that Talbert asked where she lived, whether she lived alone, if anyone would notice if she did not come home, whether she drank or used drugs, and then invited her to become inebriated with him.

Around this time, she disclosed her discomfort with Talbert's conduct to their study group and stated that she did not want to be around him. In response, Talbert accused her of bullying, which prompted her to leave the group. The next semester, at a Fall 2018 Welcome Back Mixer, Tynes avers that Talbert made unwanted sexual advances toward her and, after she rejected them, he conspicuously followed her around the event—behavior that, she alleges, was observed by a Columbia University employee.

Following the September 2018 mixer, Tynes asked classmates to inform her if Talbert would be attending social events because she did not want to see or speak to him. She also reached out to Columbia University's Sexual Violence Response (hereinafter, "SVR") office, where an unnamed counselor "identified Talbert's actions as stalking/harassing behavior" and advised her to send an email asking him not to contact her anymore. Tynes sent this email on September 20, 2018, in which she wrote: "please do not talk to me or approach me. I'm not interested in being friends or anything more, and it makes me uncomfortable when you comment on my appearance."

The letter notwithstanding, in February 2019, Tynes alleges she encountered Talbert in a nail salon near Columbia University campus, where he stared at her without saying anything until she left. In March 2019, a second counselor in Columbia University's "Student Conduct and Community Standards" Office reached out to Tynes. While the source of its knowledge is unclear, in the letter, the counselor notes that the office "received limited information alleging that you experienced behavior that may meet the definition of Gender-Based Misconduct." Tynes does not allege that she followed up and met with this counselor to discuss the allegations as the letter invites.

Lastly, Tynes alleges that, through conversations with close friends, she "learned that she was not the only Black woman Talbert had harmed. I was informed of additional instances through friends I trusted of him manipulating and acting abusively towards other women." This stand-alone averment does not specify from who she received this knowledge nor precisely the conduct she alleged was manipulative or abusive.

Talbert's affidavit disputes the surrounding context provided by Tynes. He avers that his first conversation with Tynes took place as small talk while both were on their way to the same seminar location and that he did not say "that was one of three creepy ways I thought to approach you" or show her pictures that he had taken of her. As to the allegations of misconduct within their study group, Talbert disputes the very existence of a shared study group.

He also avers (1) his conversation with plaintiff at the 2018 Welcome Back Mixer was limited to pleasantries and lasted but a brief moment and (2) he often frequented the salon near campus but never saw her in February 2019 let alone silently stared at her. In March 2018, around the same time Tynes received her letter from Columbia, Talbert filed a report with the same Student Conduct and Community Standards office, in which he sought Columbia's assistance regarding Tynes' false accusations that she was making to mutual friends and acquaintances. Around this same time, he also sought counsel from Columbia's Department of Counsel and Psychological Services. On December 9, 2021, Talbert's counsel sent a cease-and-desist letter to Columbia's Department of Anthropology. In all, Talbert contends that the tweets were defamatory per se and published with knowledge of thier falsity or reckless disregard for the truth….

The court concludes that Tynes' statements were statements of fact, and could thus form a basis for a defamation claim:

First, on its own, the fact that Tynes' statements were intended to convey her subjective interpretation of Talbert's behavior does not change whether the statements can be construed as conveying facts. Regardless, the term "stalker" is capable of a precise definition, even if the term does not constitute defamation per se. (See New York Penal Law 240.26 [defining the term stalker as "a person who pursues someone obsessively and aggressively to the point of harassment"]; Rivas v Restaurant Assoc., Inc., 223 AD3d 634, 635 [1st Dept 2024] [similar terms such as "pedophile" and "child molester" capable of being true or false and is not subjective in nature].) That "stalker," like these terms, is capable of evoking a specific allegation of criminality is what separates Tynes' statement from those considered in cases such as Farber v Jefferys (103 AD3d 514 [1st Dept 2013] [name calling someone as "no good" and "a criminal" was an opinion and not actionable]), Polish American Immigration Relief Committee Inc. v Relax (189 AD2d 370 [no reasonable person would conclude that actual criminality was charged by the epithets "thieves" and "false do-gooders"]) and Ganske v Mensch (480 F. Supp. 3d 542, 553 [SDNY 2020] [term "xenophobic" not a statement of fact because it is incapable of being proven true]).

Moreover, the surrounding context of the Tynes' tweet does not suggest that it was intended "colloquially" as she asserts. To begin, it is unclear what the purported difference between the "colloquial" sense of "stalker"—which, according to her, refers to Talbert "repeatedly following and pursuing her in a way that made her feel threatened"—and what might be considered an objective, literal usage of the word.

But even assuming a difference, in using the personal pronoun "my" stalker, Tynes suggests a unique, private familiarity with Talbert's conduct, one that, even on Twitter, would imply to the reasonable reader that she had personal knowledge that he engaged in the conduct charged—the specifics of which she chose to withhold in the posts.1 Notably, any qualifying or excessive language that otherwise might negate the impression that she meant "stalker" literally is entirely absent from her posts. And by reposting the "stalker" statement in conjunction with and immediately after "If I speak, Twitter will suspend me," Tynes only highlights the seriousness and sincerity of her allegations, which, in the surrounding context, the potential reader may very well be more inclined to interpret as statements of fact.

The comments that Talbert has "harmed multiple women" and was "abusive and manipulative" are also actionable. Though both have a more nebulous, less precise meaning than "stalker," both support her previous claim that he stalked her without offering the basis or identifying the source of her knowledge. This is especially true as plaintiff admits that she did not personally observe his harming or abusive behavior towards multiple women.

And the court held that Talbert had sufficiently alleged that Tynes' statements were knowingly false (though of course at this point these are just allegations):

In his affidavit, Talbert directly refutes each of Tynes's allegations. He avers that his personal interactions with her were incidental, brief, and never threatening. He denies making inappropriate remarks, following her, taking pictures of her, or engaging in any conduct that could be reasonably construed as stalking or harassment. He also disputes the existence of a shared study group and states that he never made unwanted advances or sent harassing messages. His denials, if true, entirely refute her allegations that is a "stalker" who "harmed multiple women."

Moreover, Talbert's denials are supported by contemporaneous documentary evidence, including a 2019 report he filed with Columbia University's Student Conduct and Community Standards office, in which he sought assistance regarding what he described as false accusations Tynes was spreading to mutual acquaintances. He also engaged with Columbia's Department of Counseling and Psychological Services around the same time, as reflected in a documented appointment confirmation. These records, created over two years before the tweets at issue, bolster the credibility of his version of events and provide the relevant proof that a reasonable mind may accept as adequate to support a finding of both falsity and actual malice.

In finding that Talbert's affidavit and corroborating evidence sufficiently shows a substantial basis for his defamation claim, the Court notes that each party has filed conflicting "self-serving" affidavits, each with some degree of corroborating evidence, though neither party's submissions entirely refute the other's position. With respect to Tynes' evidence, it is worth pointing out that she did not attach affidavits from anyone of her friends from whom she derived the "abusive and manipulative" post, from the counselor in Columbia's SVR office with whom she met to discuss Talbert's conduct, or from the alleged university employee who observed Talbert's behavior at the 2018 mixer. By resting such significant portions of her motion on her factual averments, Tynes' evidence is not so convincing that Talbert's own affidavit cannot serve as an adequate rebuttal….

The post Columbia Ph.D. Student #TheyLied Libel Suit Over Allegations of Stalking and Abuse Can Go Forward appeared first on Reason.com.

[Luke Goodrich] Religious Hiring and Church Autonomy

[Does the church-autonomy doctrine extend to hiring decisions outside the ministerial exception?]

Can a religious group legally fire a non-minister employee (like a secretary or janitor) for violating the group's beliefs about sex or marriage? As I've explained, this is an urgent question likely to reach the Supreme Court soon. And the most straightforward answer is to apply the plain text of Title VII's religious exemption—which says religious groups may limit employment to individuals who adhere to their particular religious beliefs, observances, or practices.

But Title VII's religious exemption won't resolve the question entirely. That's because employees can sue under state law, and some states have recently gutted their state-law religious exemptions. Thus, as I explain in my article, Religious Hiring Beyond the Ministerial Exception, courts will eventually have to decide if religious hiring decisions are also protected by the Constitution.

My article analyzes three potential constitutional protections: (1) the church-autonomy doctrine, (2) the freedom of expressive association, and (3) the Free Exercise Clause. Today, I'll focus on the first: church autonomy.

The Scope of Church Autonomy

Church autonomy is a hot topic. Multiple appellate judges have gone out of their way to write about it. Justices Alito and Thomas have, too. What is it?

The church-autonomy doctrine is a legal principle rooted in "the understanding that church and state are 'two rightful authorities,' each supreme in its own sphere." While this doesn't mean religious institutions are immune from civil laws, it does mean the First Amendment protects a certain sphere of autonomy in which the government is not permitted to intrude. This sphere is often described as encompassing the right of religious institutions to "decide for themselves, free from state interference, matters of church government as well as those of faith and doctrine."

The protection for "faith" and "doctrine" means civil courts cannot decide religious questions or make legal decisions based on religious doctrine.

The protection for "church government" means religious institutions have freedom to make and enforce rules for their internal governance. This includes deciding who can lead a religious organization, teach its doctrine, and perform its religious functions, all of which are protected under the ministerial exception. But the ministerial exception is only one "component" of protection for church government. Also protected are other "internal management decisions that are essential to the institution's central mission," such as decisions about "church discipline, ecclesiastical government, or the conformity of the members of the church to the standard of morals required of them."

The right to make and enforce rules for church membership is particularly longstanding and robust. Since 1872, the Supreme Court has held that civil courts "have no power to revise or question ordinary acts of church discipline, or of excision from membership." This means religious groups get to set qualifications for church membership and judge "the conformity of the members of the church to the standard of morals required of them." It also means disaffected members typically cannot sue for defamation or other torts based on acts of church discipline or statements made during church discipline. In short, the government cannot interfere in a church's decision about who is qualified to be a member.

Employment of Non-Ministers

My article argues that what is true of ordinary members is even more true of individuals employed to further a church's mission. The Supreme Court unanimously agreed this is true for employment of ministers. But other Supreme Court cases also extend this principle to non-ministers.

In Catholic Bishop, for example, the Supreme Court denied the National Labor Relations Board jurisdiction over "lay teachers" (non-ordained teachers of secular subjects like "physical education") in church-run high schools, reasoning that the Board's exercise of jurisdiction "would implicate the guarantees of the Religion Clauses." Similarly, in Amos, the Supreme Court allowed application of Title VII's religious exemption to a maintenance worker in a church-run gymnasium, noting that the exemption "alleviate[s] significant governmental interference with the ability of religious organizations to define and carry out their religious missions." Justice Brennan concurred, emphasizing that the "[c]oncern for the autonomy of religious organizations" requires respect for their right to "[d]etermin[e] that certain activities are in furtherance of an organization's religious mission, and that only those committed to that mission should conduct them."

In keeping with these decisions, several lower courts (see footnote 240) have applied the church-autonomy doctrine to bar employment lawsuits by non-ministers who were dismissed for violating church teaching.

The principle that emerges from these cases is the same as that in Catholic Bishop and Amos: Church autonomy protects a religious group's freedom to decide what activities are part of its religious mission and who is religiously qualified to undertake those activities—including as a non-minister. And if an employment-discrimination lawsuit would prevent a religious organization from requiring adherence to its religious occupational qualifications—whether the qualification is based on religious belief (you must be a Christian; you must be an Orthodox Jew) or religious conduct (you must refrain from sex outside marriage; you must refrain from non-kosher food)—it is barred by the church-autonomy doctrine.

Objections

There are two main counterarguments to this understanding of church autonomy. First, some courts have said that applying church autonomy to religious occupational qualifications for non-ministers "would render the ministerial exception superfluous."

But this objection misunderstands the relationship between the ministerial exception and the protection for religious occupational qualifications. The ministerial exception applies to only a narrow set of employees (ministers), but protects a broad range of employment decisions—including decisions not "made for a religious reason." The religious-occupational-qualification protection is different: It applies to a broader group of employees (including non-ministers), but a much narrower set of employment decisions—only those based on religious qualifications for employment. Thus, while the doctrines can sometimes overlap, they still have different scopes and perform different functions.

The second objection is that there are no principled, workable limits on this religious-occupation-qualification protection. I address this objection more fully in my article. But in a nutshell, I argue that the limits of this constitutional protection are similar to the limits of Title VII's religion exemption. First, the protection is limited to religious organizations. There is ample caselaw drawing a line between religious and nonreligious organizations in various contexts—such as under the ministerial exception, Title VII's religious exemption, and federal and state tax law. This caselaw tells us, among other things, that for-profit businesses likely don't count as religious.

Second, the protection is limited to employment decisions based on sincere, religious occupational qualifications. That means insincere (i.e., "faked") qualifications aren't a protected basis for an employment decision. Nor are qualifications invoked as a pretext to mask a different, discriminatory reason for the decision. Although there are constitutional limitations on a court's inquiry into sincerity and pretext, those issues are not completely off limits, and courts regularly address them in a variety of religious contexts.

Finally, having considered the outer limits of this protection, it is also important to consider heartland cases. Suppose, for example, Congress repealed Title VII's religious exemption—making it illegal for religious groups to hire employees based on "religion." Under this regime, the government could force a Baptist church, for example, to hire an atheist church secretary. Would such a regime violate church autonomy?

Of course it would. As the Supreme Court has said, church autonomy protects "internal management decisions that are essential to the institution's central mission." This includes defining the mission, deciding what activities advance the mission, and deciding that "only members of its community" can "perform those activities." If the government could force a Baptist church to hire atheists, the First Amendment would be slender reed indeed.

Conclusion

In short, church autonomy is not limited to the ministerial exception. It also includes the freedom of religious groups to establish and maintain religious qualifications for employment—including for non-ministers. This means that when religious groups face post-Bostock claims of sex discrimination by non-ministers, they can invoke not only Title VII's religious exemption but also the First Amendment's church-autonomy doctrine.

But the church-autonomy doctrine is not the only potential constitutional protection. Tomorrow's post will explore another: the First Amendment right of expressive association.

The post Religious Hiring and Church Autonomy appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Wednesday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Wednesday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

August 5, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Where Are the October And November Sitting Calendars?

[Last year, the calendars were posted by the end of July. ]

As of August 5, 2025, the Supreme Court has not yet posted the argument calendars for the October and November sittings.

For OT 2024, the October and November calendars were posted on July 26, 2024.

For OT 2023, the October calendar was posted on July 14, 2023.

The Court is behind schedule.

The Justices are so busy with the emergency docket, perhaps they are neglecting the merits docket!

The post Where Are the October And November Sitting Calendars? appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers