Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 56

August 13, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] First Amendment Claim Over Firing of Firefighter for Supposedly Racially Offensive Anti-Abortion Post Can Go Forward

From today's decision in Melton v. City of Forrest City, written by Judge David Stras, joined by Judges Lavenski Smith and Ralph Erickson:

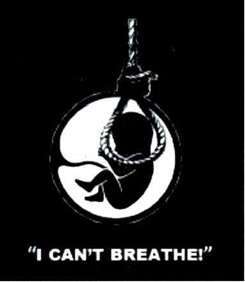

Steven Melton is a pro-life, evangelical Christian. In June 2020, he reposted a black-and-white image on Facebook that depicted a silhouette of a baby in the womb with a rope around its neck. His intent was to convey that he was "anti-abortion."

Others did not view the image the same way. Two weeks after he posted it, a retired fire-department supervisor complained to Melton that he thought it looked like a noose around the neck of a black child. It upset him because the caption of the image, "I can't breathe!," was associated with the protests surrounding George Floyd's death. Melton agreed to delete it immediately.

Deleting it was not enough for Mayor Cedric Williams, who called him into his office the next day. Although Melton was "apologetic," the mayor placed him on administrative leave pending an investigation. After a single day reviewing Melton's Facebook page and discussing the post with the current fire chief, two retired firefighters, several attorneys, and a human-resources officer, the mayor decided to fire Melton over the image's "egregious nature."

He was concerned about the "huge firestorm" it had created. Among other things, the fire chief's phone had been "blowing up," "several" police officers had become "very upset," and the "phone lines" were jammed with calls from angry city-council members and citizens. Some said that Melton "should not be a part of the … fire department responding to calls." A few even said that they did not want "him coming to their house … for a medical call or fire emergency." According to the mayor, these complaints "threaten[ed] the City's ability to administer public services."

Melton was fired; he sued, claiming the firing violated the First Amendment, and the court allowed the claim to go forward:

Public employees "must," according to the Supreme Court, "accept certain limitations on [their] freedom," because the government has valid "interests as an employer in regulating the[ir] speech," Recognizing, however, that they "do not surrender all their First Amendment rights by reason of their employment," the Court has staked out a middle ground. (emphasis added). Known as Pickering balancing, it requires weighing the government's interest "in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees" against the employee's interest "in commenting upon matters of public concern." Pickering v. Bd. of Educ. (1968). Courts weigh these interests on a post hoc basis, long after the speech and the alleged retaliation have come and gone. It is no easy task.

Getting there even involves addressing a couple of threshold issues, one for each side. For Melton, he can bring a claim for retaliation only if he was speaking "as a citizen on a matter of public concern." Then the focus shifts to the government employer to establish that the speech "created workplace disharmony, impeded [Melton's] performance, … impaired working relationships," or otherwise "had an adverse impact on the efficiency of the [fire department's] operations." Only if both are true will we do a full Pickering balancing and weigh these interests against each other.

The record is clear on the first issue. Melton posted the image to his personal page on his own time, and there is no dispute that race and abortion are matters of "political, social, or other concern to the community." From there, the "possibility of a First Amendment claim ar[ose]" out of the "individual and public interest[]" in Melton's speech.

The record is more of a tossup on whether there was a negative impact on Forrest City's delivery of "public services." Sometimes a government employer will experience an actual disruption. Other times, it will have a "reasonabl[e] belie[f]" in "the potential for disruption." Either is usually enough when the government entity is a public-safety organization. But when neither is present, there are "no government interests in efficiency to weigh" and Pickering balancing "is unnecessary."

At best, the evidence of disruption is thin. As the district court pointed out, everyone agrees "that there was no disruption of training at the fire department, or of any fire service calls, because of the post or the controversy surrounding it." Instead, Mayor Williams argues that the "firestorm" itself is what "disrupted the work environment." "[S]everal" police officers and city-council members were upset and "phone lines [were] jammed" with calls from concerned citizens. A few opposed Melton's continued employment as a firefighter and did not want him "coming to their house … for a medical call or fire emergency." These calls seemed to be the main motivation for firing Melton.

The problem is that there was no showing that Melton's post had an impact on the fire department itself. No current firefighter complained or confronted him about it. Nor did any co-worker or supervisor refuse to work with him. Granting summary judgment based on such "vague and conclusory" concerns, without more, runs the risk of constitutionalizing a heckler's veto. Enough outsider complaints could prevent government employees from speaking on any controversial subject, even on their own personal time. And all without a showing of how it actually affected the government's ability to deliver "public services"—here, fighting fires and protecting public safety.

Much of what remained was predictive. Mayor Williams claimed, for example, that "conveying racist messages against Black people [would] affect trust between firefighters." To provide a "reasonable prediction[]" sufficient to take the case away from a jury, a decisionmaker must do more than make a vague statement in response to a conditionally worded question about what could happen. When the record and the prediction do not match, it will usually be up to the jury to resolve the discrepancy and determine whether the prediction was reasonable enough to be entitled to "substantial weight."

What the district court should not have done was automatically give the mayor's belief "considerable judicial deference." As one of our cases puts it, "we have never granted any deference to a government supervisor's bald assertions of harm based on conclusory hearsay and rank speculation." Keep in mind that, in addition to the lack of evidence supporting the mayor's prediction, his brief investigation could lead a reasonable jury to conclude that what he said masked the true reason for Melton's firing, which was a disagreement with the viewpoint expressed in the image. The jury's role will be to resolve these factual disputes "through special interrogatories or special verdict forms." The district court can then decide, based on "the jury's factual findings," whether Melton's speech was protected.

And the court concluded that the law here was "clearly established," so Melton's claim couldn't be dismissed on qualified immunity grounds:

Insufficient evidence of a disruption would be "fatal to the claim of qualified immunity" because there would be no governmental interest to weigh. If the jury finds sufficient evidence of disruption to get to Pickering balancing, on the other hand, then "the asserted First Amendment right [is] rarely considered clearly established."

Frank H. Chang and John Michael Connolly (Consovoy & McCarthy) and Chris P. Corbitt and David Ray Hogue (Hogue & Corbitt) represent Melton.

The post First Amendment Claim Over Firing of Firefighter for Supposedly Racially Offensive Anti-Abortion Post Can Go Forward appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] My New Boston Globe Article on Why Massachusetts Should Reject Rent Control, and Instead End Exclusionary Zoning

[Rent control would only make the housing crisis worse. Zoning reform would make things better.]

Illustration: Lex Villena; Lev Kropotov

Illustration: Lex Villena; Lev Kropotov Today, the Boston Globe published my article on why rent control is a terrible approach to addressing the housing crisis. Massachusetts should instead ban exclusionary zoning. Here is an excerpt:

Massachusetts may have a rent control measure on its 2026 ballot, which would restrict rent increases throughout the state. Advocates claim rent control would alleviate the state's housing crisis. They couldn't be more wrong. Rent control is a proven failure that actually exacerbates housing shortages. The state should instead ban exclusionary zoning, which restricts the types of housing that can be built in a given area. That could truly alleviate shortages and make housing more affordable.

Rent control is condemned by a broad consensus of economists and housing experts across the political spectrum. Jason Furman, former chair of Barack Obama's Council of Economic Advisers, notes that "[r]ent control has been about as disgraced as any economic policy in the tool kit." A recent meta-study in the Journal of Housing Economics found that while it effectively slows rent increases in controlled units, it has multiplenegative effects, including reduction in the quantity and quality of available housing….

By contrast, ending exclusionary zoning across the state would greatly increase housing construction and reduce rents, while empowering property owners to have greater control over their land….

Extensive research by economists and other scholars finds that exclusionary zoning massively increases housing prices and prevents millions of people from "moving to opportunity" — taking up residence in places where they could find better jobs and educational options. Exclusionary zoning has a long history of being used to keep out minorities and poor people. It also greatly increases homelessness by pricing low-income people out of the housing market.

I grew up in Massachusetts — where my parents and I arrived as poor recent immigrants in 1980 — and owe much to the opportunities the state has to offer. Curbing exclusionary zoning would help ensure that more people of all backgrounds could access those opportunities….

Zoning is often viewed as a tool to protect the interests of current homeowners, many of whom support "NIMBY" ("not in my backyard") restrictions on building. But many homeowners would have much to gain from ending restrictions on housing construction. They would benefit from added economic growth and innovation, increases in the value of their property if it could be used to build multifamily housing, and lower housing costs for their children.

Current property owners would also benefit from having the right to use their land as they see fit. Advocates of local control of land use should embrace YIMBYism ("yes in my backyard"): Letting property owners decide how to use their own land is a far greater level of local control than allowing local governments to impose one-size-fits-all regulations.

YIMBY zoning reform unites experts across the political spectrum. Supporters range from progressives such as Furman and former president Joe Biden's Council of Economic Advisers to free-market advocates such as Edward Glaeser of Harvard, one of the world's leading housing economists….

There is much room for zoning-reform progress in Massachusetts. The National Zoning Atlas recently surveyed the state's zoning rules and found that about 63 percent of the state's residential land is restricted to single-family homes only (including some where multifamily construction is permitted only after a special public hearing, which can be easily manipulated by NIMBY forces to block development). Many communities also have other severe restrictions, such as minimum lot sizes and parking mandates (imposed on 76 percent of residential land).

I would add that most of these problems are far from unique to Massachusetts. Other states should also reject rent control and instead embrace YIMBYism.

The post My New Boston Globe Article on Why Massachusetts Should Reject Rent Control, and Instead End Exclusionary Zoning appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Why the Supreme Court is Highly Unlikely to Overturn Obergefell in the Kim Davis Case

[My Cato Institute colleague Walter Olson explains.]

Kim Davis. (Getty Images)

Kim Davis. (Getty Images)

Kim Davis, a former Kentucky county clerk who was sued for refusing to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples has filed a cert. petition asking the Supreme Court to overturn Obergefell v. Hodges, the landmark 2015 ruling striking down laws banning same-sex marriage:

Ten years after the Supreme Court extended marriage rights to same-sex couples nationwide, the justices this fall will consider for the first time whether to take up a case that explicitly asks them to overturn that decision.

Kim Davis, the former Kentucky county clerk who was jailed for six days in 2015 after refusing to issue marriage licenses to a gay couple on religious grounds, is appealing a $100,000 jury verdict for emotional damages plus $260,000 for attorneys fees.

In a petition for writ of certiorari filed last month, Davis argues First Amendment protection for free exercise of religion immunizes her from personal liability for the denial of marriage licenses.

More fundamentally, she claims the high court's decision in Obergefell v Hodges -- extending marriage rights for same-sex couples under the 14th Amendment's due process protections -- was "egregiously wrong."

I have been getting media calls about this, and have seen expressions of concern from people worried about it. My Cato Institute colleague Walter Olson has a helpful Facebook post explaining why such fears are likely misguided. I reprint it here, with his permission:

Dozens of friends are freaking out at news reports that Kim Davis, the disgraced Kentucky clerk who has struck out in court up to now, is asking the Supreme Court to overturn Obergefell, the same-sex marriage ruling.

I understand why people get upset, but here's why this story doesn't even make it up to number 200 on my list of current worries:

Pretty much anyone with a pulse who's exhausted other avenues can file a certiorari petition and it doesn't mean the Supreme Court will hear the case, let alone agree to revisit one of its most famous modern rulings, let alone resolve it the wrong way.

"People said they weren't going to overturn Roe, then they did."

Court-watchers have known literally for decades that there was a big chance Roe would go. Overturning it was the number one project for much of the legal Right through countless confirmation battles. Thousands of anti-Roe meetings were held and articles published. There is no comparable head of steam on Obergefell, or really any head of steam at all.

"Terrible things are happening and I don't want to be told that I'm overreacting."

I agree that terrible things are happening. Accurately assessing which terrible things have a serious probability of happening soon is essential in directing our energy to where it can do the most good.

"I don't trust the Supreme Court."

You don't have to trust them, but you should practice the most useful skill in Court-watching: counting to five. The anti forces will get Thomas and probably Alito. Roberts was strongly against at the time but has been careful to treat it as legitimate precedent since. Gorsuch usually sides with religious litigants but also wrote Bostock, the most important gay rights decision in years, and Roberts raised eyebrows by joining him. Most people who know Barrett and Kavanaugh believe them to have zero appetite for reopening this issue. Trump isn't pushing for it. Granting cert takes four votes, overturning a case five. I don't see Davis getting up even to three on the question of whether to overturn Obergefell.

Each time I write a version of this prediction I get called rude names, as if I were consciously misleading people for some fell purpose. But as someone with real rights of my own at stake, I'm just trying to give you my honest reading. We'll probably know within three months whether the Court will hear Davis's case and if so on what question presented. Save your anger till then.

Both Walter and I are longtime same-sex marriage supporters, since before it was popular. And, as Walter notes, his stake in this issue goes beyond legal theory (he is a gay man in a same-sex marriage). That doesn't by itself prove us right. But it does mean Walter, at least, cannot easily be accused of downplaying concerns about reversing Obergefell because he doesn't really care about the issue.

In a post on the tenth anniversary of Obergefell, I explained its great benefits, why it reached the right result (even though it should have used different reasoning), and why it is likely to prove durable. Maybe I will be proven wrong on the latter point. But if Obergefell does get overruled, it won't be in the Kim Davis case.

Her case has multiple flaws as a potential vehicle for the Obergefell issue. Among other things, that question is an appendage to a dubious religious-liberty claim, under which Davis claims that government officials have a First Amendment right to refuse to issue marriage licenses to couples they disapprove of on religious grounds. It's worth noting, here, that some people have religious objections to interracial marriages and interfaith marriages, among other possibilities. Does a clerk with religious objections have a constitutional right to refuse to issue a marriage license to an interracial couple or to one involving an intermarriage between a Jew and a Christian? The question answers itself.

The court of appeals rightly rejected Davis' claim on the grounds that "Davis is being held liable for state action, which the First Amendment does not protect—so the Free Exercise Clause cannot shield her from liability. The First Amendment protects 'private conduct,' not 'state action.'"

This is pretty obviously right. In the private sector, I think there often is a First Amendment free speech or religious liberty right to refuse to provide services that facilitate same-sex marriages, as with bakers who refuse to bake a cake for a same-sex wedding, website designers who refuse to design a site for such a wedding, and so on. While I have little sympathy for such people's views, they do have constitutional rights to act on them in many situations. And same-sex couples almost always have other options for getting these kinds of services.

Public employees engaged in their official duties are a very different matter. They are not exercising their own rights, but the powers of the state. And the services they provide are often government monopolies to which there is no alternative.

The post Why the Supreme Court is Highly Unlikely to Overturn Obergefell in the Kim Davis Case appeared first on Reason.com.

[Keith E. Whittington] On the Status of Judicial Independence in the American Constitutional Order

[My new paper on judicial independence as a constitutional construction.]

I have posted a new paper on "Judicial Independence as a Constitutional Construction."

The paper builds on the notion of constitutional construction and the role constructions play in our constitutional politics and in structuring the workings of our constitutional system. It focuses on the specific context of judicial independence and contestation over how valuable that ideal actually is and how it should be realized in practice. Current proposals to reform the courts might unsettle long-established understandings of how the judiciary should operate, but such efforts to unsettle and reform established constitutional practices and understandings have happened before.

From the abstract:

An independent judiciary, in the American context, might best be understood as a constitutional construction. That is, it is a politically constructed set of practices, institutions, and norms that extend but do not contradict the legal requirements of the formal constitution. As such, judicial independence has come to occupy a fundamental status within our inherited constitutional order. But importantly, it is mutable. Our inherited practice of judicial independence has been built up, and fought over, across time, and within the contours of the written constitution can be significantly reconstructed.

The example of judicial independence can serve as a useful illustration of the significance of unwritten practices to our constitutional order. This also provides an opportunity to examine how judicial independence was constructed, and contested, across American history. As current activists and politicians raise questions anew about the future of judicial independence in America, these current debates can be situated within a long history of debates about the proper role, composition, and structure of American courts. This Article reviews those debates regarding federal courts in the Jeffersonian era, state courts in the Jacksonian era, and the Supreme Court in the New Deal era.

The post On the Status of Judicial Independence in the American Constitutional Order appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Saudi Activist's Claims Against Alleged Hackers for UAE Government Can Go Forward

From Judge Karin Immergut (D. Or.) yesterday in Alhathloul v. DarkMatter Group:

This case involves allegedly unlawful actions by Defendant DarkMatter Group ("DarkMatter"), a software company based in the United Arab Emirates, and three of its former senior executives, Marc Baier, Ryan Adams, and Daniel Gericke (the "individual Defendants" and, together with DarkMatter, the "Defendants"). Plaintiff Loujain Alhathloul, a prominent Saudi women's rights activist, alleges the Defendants hacked her iPhone, surveilled her movements, and exfiltrated her private data. Plaintiff alleges the hack facilitated her arrest in the United Arab Emirates and rendition to Saudi Arabia, where she alleges she was imprisoned and tortured. Plaintiff alleges all Defendants violated the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act ("CFAA"), and conspired together and with Emirati officials to violate the CFAA. She also alleges the individual Defendants' actions constitute a crime against humanity actionable under the Alien Tort Statute ("ATS").

This Court concludes Plaintiff's FAC makes a prima facie showing of specific personal jurisdiction over all Defendants. Plaintiff's allegations that Defendants committed an intentional tort while Plaintiff was in the U.S., together with Defendants' other forum-related contacts, establish minimum contacts that arise out of Plaintiff's claims, and Defendants have failed to establish that exercising jurisdiction would be unreasonable. The motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction is therefore denied.

This Court also denies Defendants' motion to dismiss Plaintiff's CFAA and CFAA conspiracy claims. Finally, this Court declines to recognize Plaintiff's alleged tort of discriminatory persecution under the ATS and accordingly grants the individual Defendants' motion to dismiss that claim for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction….

The post Saudi Activist's Claims Against Alleged Hackers for UAE Government Can Go Forward appeared first on Reason.com.

August 12, 2025

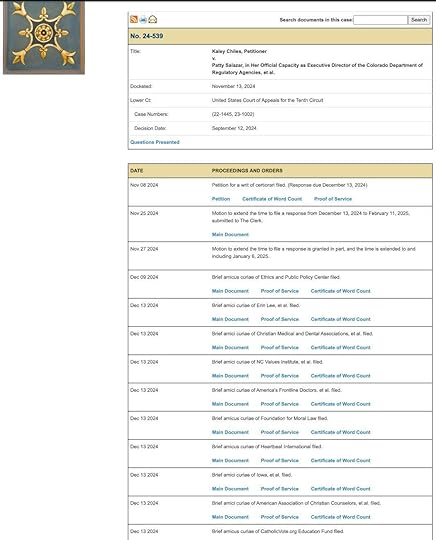

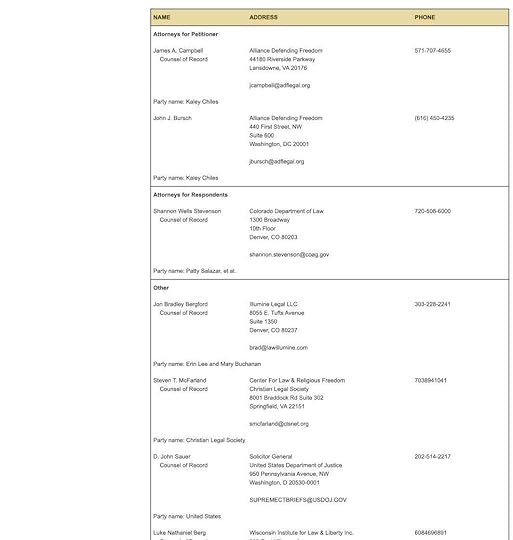

[Josh Blackman] SCOTUS Redesigns The Docket Page

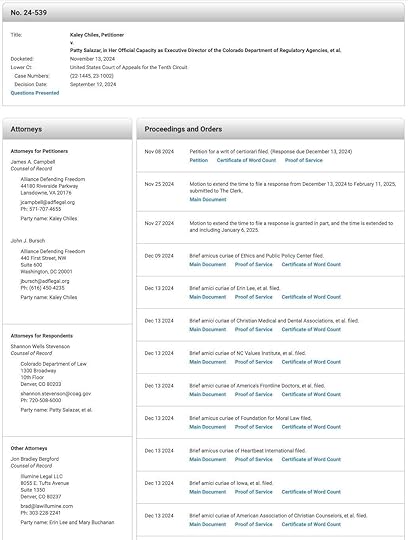

SupremeCourt.gov got a redesign recently. The docket page previously looked like this. With the , all of the counsel were listed at the bottom of the page. There is a lot of wasted white space.

The has a different color scheme. The brown color is now a silver color. And the sharp edges are now rounded. The biggest change is that counsel are listed on the left side column. The new design is far more elegant, and has far less wasted space.

The post SCOTUS Redesigns The Docket Page appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Are Opinions Respecting En Banc Denials "Offensive to Our System of Panel Adjudication"?

[The judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit split over whether they should write about the reasons for their splitting over en banc review.]

Today the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit denied rehearing en banc in Mitchell v. City of Benton Harbor, a case in which a divided panel concluded that Benton Harbor residents could sue the city and city officials for violating their substantive-due-process right to bodily integrity for failing to mitigate and adequately address lead contamination in the local water system. Judge Moore wrote the original panel opinion, joined by Judge Cole. Judge Larsen wrote separately, concurring in part and dissenting in part.

Today, Judge Larsen dissented from the courts denial of a petition for rehearing en banc, joined by Judges Kethledge, Thapar, Bush, Nalbandian, Readler, and Murphy. This dissent prompted a statement from Judge Moore, decrying the growing practice of dissents and other opinions or statements respecting en banc denials. (In this regard, Judge Moore echoed some concerns raised by Judge Wynn on the Fourth Circuit several years ago.) Judge Moore's opinion, in turn, prompted a second dissent from the en banc rehearing denial by Judge Readler, joined by Judge Bush, expressly addressing the question of whether there are two many opinions respecting the denial of rehearing en banc. (Answer: No.).

Judge Larsen's dissent begins:

The court concludes that several City of Benton Harbor officials plausibly violated city residents' clearly established substantive due process right to bodily integrity. How? Each official is alleged to have engaged in slightly different conduct. But to take one, consider the case of Mayor Marcus Muhammad. At a press conference, he informed residents that the water in some city homes had dangerous levels of lead, and he advised them that they could work with the City to test their water. He also urged them not to panic; and that, according to the court, crossed a clearly established constitutional line because it "undermined" the rest of the message. Mitchell v. City of Benton Harbor, 137 F.4th 420, 437 (6th Cir. 2025). In other words, the court strips Muhammad of qualified immunity for not delivering the warning with the (now) constitutionally required tone of alarm.

Muhammad's failure to speak with sufficient alarm is in no way "conscience shocking"

behavior that violates the Constitution. And until today, no case has come close to holding that it is. Accordingly, Muhammad is entitled to qualified immunity.

The court's conclusion to the contrary brazenly defies Supreme Court precedent, which

alone merits en banc review. And the importance of the question at issue—the constitutional liability of government officials responding to naturally occurring environmental crises—deepens the need for the full court's consideration of this case. I thus respectfully dissent from the denial of rehearing en banc.

Judge Moore's opinion concurring in the denial (and responding to Judge Larsen) begins:

There is a rising trend in our circuit of publishing separate statements when rehearing is denied after a poll of the en banc court. I have serious concerns about this practice. In this case, the opinions of the majority and the dissent have already been fully and carefully explained. Drafting CliffsNotes versions of our views is not only unnecessary, but it is also offensive to our system of panel adjudication. "The trust implicit in delegating authority to three-judge panels to resolve cases as they see them would not mean much if the delegation lasted only as long as they resolved those cases correctly as others see them." Issa v. Bradshaw, 910 F.3d 872, 877–78 (6th Cir. 2018) (Sutton, J., concurring in the denial of rehearing en banc). By accumulating votes for or against the positions articulated in the panel opinions, we cast doubt on circuit precedent, erode our faith in the panel system, and give rise to our own "shadow docket." But when, as here, the dissenting judge accuses the panel majority of "brazenly def[ying] Supreme Court precedent," Principal Dissental at 10, I cannot allow that accusation to go unanswered. See United States v. New York, New Haven & Hartford R.R., 276 F.2d 525, 553–54 (2d Cir. 1960) (statement of Friendly, J.), overruled in part, Chappell & Co. v. Frankel, 367 F.2d 197 (2d Cir. 1966). So, I write in response to re-explain the panel majority's reasoning.

This case concerns a lead-water crisis in Benton Harbor, Michigan, which played out in the wake of the highly publicized water crisis in Flint, Michigan. In October 2018, routine water testing revealed that Benton Harbor's municipal water supply was tainted with dangerous quantities of lead. See Mitchell v. City of Benton Harbor, 137 F.4th 420, 425 (6th Cir. 2025). As is well known, lead is a toxic metal that is particularly hazardous to children. Id. Even low-level exposure can cause lifelong consequences. Id. Despite these serious risks, and with the situation in Flint barely in the rearview mirror, Plaintiffs allege that Benton Harbor City officials encouraged residents to drink water that they knew was contaminated with lead, leading hundreds of children to be exposed to lead and suffer symptoms of lead poisoning. See id. at 428–29, 437–38. Because this would clearly violate those individuals' constitutional right to bodily integrity, the panel majority allowed the case against the City officials to proceed in the district court past a motion to dismiss. I concur in the court's decision to deny rehearing en banc.

Judge Moore's opinion prompted a response from Judge Readler:

I join fully in Judge Larsen's dissent. Our concurring colleague's broader concern over separate writings at the en banc stage, Concurring Op. 3, ironically enough, prompts me to add one more writing to the mix.

Our colleague has "serious concerns" over what she sees as the "rising trend in our circuit of publishing separate statements when rehearing is denied" by the en banc court. Id. If past practice is any indicator, our colleague's distaste for separate writings, dissents from the denial of rehearing en banc in particular, appears to be a very recent phenomenon. [Lengthy string cite omitted.] It is also difficult to reconcile with the current arc of legal discourse.

Debate over weighty issues is the heart and soul of the legal profession. In nearly all respects, we encourage the exchange of ideas. For lawyers and litigants, their efforts benefit from legal analysis by peers and judges alike, all of which helps shape legal practice and strategy going forward. See Georgia v. Public.Resource.Org., Inc., 590 U.S. 255, 288 (2020) (Thomas, J., dissenting) (explaining that the existence of multiple opinions helps readers "understand[] the reasoning that animates the rule" and thus "provides pivotal insight into how the law will likely be applied in future judicial opinions"). The same is true for judges, whose "legal analysis" is likewise "elevate[d]" by "healthy and respectful discussion about important ideas." United States v. Boler, 115 F.4th 316, 333 (4th Cir. 2024) (Quattlebaum, J., dissenting). After all, in ultimately

resolving the difficult legal questions put before us, we customarily are aided by more thought and inspection, not less.

That is what separate writings—concurrences, dissents, concurrals, dissentals, and the like—aim to achieve. They flesh out legal issues beyond what prior opinions have done, either reinforcing earlier conclusions or raising questions over them. These writings thus "serve an important function and," for that reason, "are taken seriously by courts, the public, the academy, and the legal profession." Alex Kozinski & James Burnham, I Say Dissental, You Say Concurral, 121 Yale. L.J. Online 601, 607 (2012). Indeed, contrary to our colleague's concern about "erod[ing] faith in the panel system," Concurring Op. 1, the practice of writing at the en banc stage in fact increases our Court's legitimacy: "It does honor to the law, promotes justice, and serves the interests of an informed public when citizens learn that appellate judges have given difficult and important cases exacting scrutiny—not just one judge or even the three-judge panel, but an entire court of appeals." Kozinski & Burnham, supra, at 612. Few jurists would understand all of this better than our concurring colleague, who has contributed as much to the legal discourse in our Circuit as has anyone over the last three decades.

True, in some instances an en banc–stage writing may reiterate points in an underlying panel opinion. See Concurring Op. 1 (critiquing separate writings that are "CliffNotes versions" of panel opinions). . . . Yet even then, the writing serves an important function: it allows other judges apart from those randomly assigned to the panel to join in the effort, which further informs issues in the current case, to say nothing of the next one. See Kozinski & Burnham, supra, at 604 (defending the legitimacy of

"off-panel judge[s]" writing at the en banc stage). The esteemed Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson summed up the en banc process exactly this way. "Judges vote on th[e] [en banc] poll, and judges are entitled to explain their reasons for that vote. Giving reasons is what we do. Reasoning adds to judicial transparency; it does not detract from it. And debate on issues of legal and public importance is to be welcomed, not disapproved." Doe v. Fairfax Cnty. Sch. Bd., 10 F.4th 406, 414 (4th Cir. 2021) (order) (Wilkinson, J., dissenting from denial of en banc rehearing).

Members of the Supreme Court understandably hew to this same practice. At the certiorari stage, justices will sometimes craft separate opinions expressing their views on why a case should (or should not) have been accepted for review, views that often inform related cases going forward. . . . see also Eugene Gressman et al., Supreme Court Practice § 5.5, at 330–31 (9th ed. 2007) (noting, nearly two decades ago, the rise in "the practice of publicly recording dissents from the denial of certiorari" and cataloguing the "[m]any different purposes" these writings serve, including providing "signals to the bar" or "to the litigants").

But there is one more reason why these writings are valued: The Supreme Court relies on them in overseeing our legal system. The Supreme Court faces a daunting task. Among all of the cases in the federal courts, it must select the most deserving for review. See Sup. Ct. R. 10 ("A petition for a writ of certiorari will be granted only for compelling reasons."). To do so, it relies on the development of legal opinions across the "inferior courts." U.S. CONST., art. III, § 1. As cases "percolate[]" in those courts, jurists add their "independent evaluation" of the issues presented, meaning that when the Supreme Court eventually is asked to review those issues, it "has the benefit of the experience of those lower courts." See Samuel Estreicher & John E. Sexton, A Managerial Theory of the Supreme Court's Responsibilities: An Empirical Study, 59 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 681, 716 (1984). And that percolation process, it is well understood, informs the Supreme Court's decisionmaking, both which cases to decide, and how to decide them. . . .

Separate writings in the courts of appeals, including at the en banc stage, are critical pieces to this puzzle. In case after case, the Supreme Court has cited those writings and explained how they informed the Supreme Court's review process. Examples from just the last two Supreme Court terms abound. . . .

In so doing, the Supreme Court often highlights the number of judges who joined the

writing, which I take to reflect the weight justices place upon these efforts in the appeals courts. . . . A notable example on this front is the Supreme Court's recent opinion in Grants Pass, which lays out in detail how the Supreme Court views separate writings at an appeals court's en banc stage:

The city sought rehearing en banc, which the court denied over the objection of 17 judges who joined five separate opinions. Judge O'Scannlain, joined by 14 judges, criticized Martin's "jurisprudential experiment" as "egregiously flawed and deeply damaging—at war with constitutional text, history, and tradition." Judge Bress, joined by 11 judges, contended that Martin has "add[ed] enormous and unjustified complication to an already extremely complicated set of circumstances." And Judge Smith, joined by several others, described in painstaking detail the ways in which, in his view, Martin had thwarted good-faith attempts by cities across the West, from Phoenix to Sacramento, to address homelessness.

144 S. Ct. at 2214 (citations omitted). In particular, the separate en banc–stage writings of our colleagues on the Ninth Circuit highlighted both the repeat-player legal doctrines commonly at issue in that circuit and the damaging practical consequences flowing from those doctrines, all of which likely informed the Supreme Court's ultimate resolution of the case. As this and other cases reflect, "the jurisprudential benefits that come with" writing separately at the en banc stage "more than merit a continuing and vibrant community of dissental writing." Diarmuid F. O'Scannlain, A Decade of Reversal: The Ninth Circuit's Record in the Supreme Court Through October Term 2010, 87 Notre Dame L. Rev. 2165, 2178 (2012).

Much more could be said on the topic, but the point seems easy enough to understand. Most of us welcome, indeed encourage, the exchange of ideas, the Supreme Court included. Perhaps one who does not want a panel opinion placed in the spotlight might bristle at colleagues adding their dissenting voices, as a collection of judges, led by Judge Larsen, have done here. See Jonathan H. Adler, Are There Too Many Dissents from Denial of En Banc Petitions?, Volokh Conspiracy (Aug. 31, 2021), https://perma.cc/228V-E5TX ("I get that judges do not like to be criticized, and they like even less to be overruled. And if a judge's overall judicial philosophy is out-of-step with that of the Supreme Court, such reversals may be more common. Yet if such reversals are a problem, it seems the better course would be for circuit courts to decide cases in accord with prevailing legal principles than to complain about dissents from denial of en banc review."); see also Kozinski & Burnham, supra, at 604 (describing the practice of limiting nonpanel participation at the en banc stage as "the judicial equivalent of the fox guarding the henhouse"). Happily, that sentiment appears to be a minority one in our Circuit.

Also of note, today the SIxth Circuit also denied rehearing en banc in C.S. v. McCrumb. Judge Clay authored an opinion concurring in the denial, joined by Judge Stranch; Judge Gibbons concurred in the denial of panel rehearing and a statement respecting the denial of rehearing en banc; and Judge Readler delivered a separate statement respecting the denial of the petition for rehearing en banc, joined by Judges Thapar and Bush.

The post Are Opinions Respecting En Banc Denials "Offensive to Our System of Panel Adjudication"? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Reporters Without Borders' Stance on US-Brazil Policy Undermines Press Freedom"

From Jacob Mchangama (The Bedrock Principle), a leading scholar of free speech history and of international speech restrictions:

Last week, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) issued one of the more remarkable statements I've seen from a group dedicated to press freedom. It criticized the Trump administration for imposing 50% tariffs on Brazil in response to what the U.S. called the Brazilian government and judiciary's "unprecedented actions to tyrannically and arbitrarily coerce U.S. companies to censor political speech."

To be clear, there are fair reasons to question the administration's sincerity and its focus on Brazil. Why, for instance, isn't the U.S. going after Russia, which has long banned U.S. tech companies for spreading "illegal content" and fined Google $360 million in 2022 and $78 million this year for failing to remove "prohibited material"? Meanwhile, the administration's own record on speech and press freedom at home severely undermines its credibility when criticizing wrongdoings abroad.

But these were not RSF's objections. Instead, one of the world's best-known press-freedom organizations effectively endorsed Brazil's approach:

"Using free speech as a pretext for trade sanctions is both cynical and misleading. Freedom of expression does not excuse disinformation, and it is not a shield for corporate influence. Brazil must not back off legitimate regulatory efforts designed to strengthen the right to reliable information and protect democratic debate online. Initiatives to counter disinformation, hate speech, and online harm are essential to protect journalism and democratic debate."

According to RSF, prohibiting "disinformation" is not only legitimate but necessary—and it strengthens, rather than weakens, journalism and democratic debate. That's an unusual stance for a press-freedom group….

Much worth reading in its entirety.

The post "Reporters Without Borders' Stance on US-Brazil Policy Undermines Press Freedom" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Arkansas Ban on Youth Gender Transition Procedures Upheld, Including Restriction on Referrals for Such Procedures

[But the restriction appears to cover only referrals for illegal in-state procedures, and not referrals for legal out-of-state procedures.]

Today's en banc Eighth Circuit opinion in Brandt v. Griffin, written by Judge Duane Benton, held—largely relying on the Supreme Court's decision this Summer in U.S. v. Skrmetti—that the Act doesn't involve a presumptively unconstitutional sex classification or a transgender status classification. It also held that the Act doesn't violate parents' "right to provide appropriate medical care for their children," for much the same reasons given by panels in the Tenth Circuit and Sixth Circuit. And the court said this as to the prohibition on referrals:

[T]he Supreme Court recognizes that the First Amendment "does not prevent restrictions directed at commerce or conduct from imposing incidental burdens on speech." National Inst. of Family & Life Advocates v. Becerra (2018). "States may regulate professional conduct, even though that conduct incidentally involves speech." In Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, the Court upheld a provision compelling physicians to provide information to patients about the risks of abortion. The plurality opinion recognized that the requirement "implicated" a physician's First Amendment rights, "but only as part of the practice of medicine, subject to reasonable licensing and regulation by the State." Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey (1992) (joint opinion of O'Connor, Kennedy, and Souter, JJ.), overruled on other grounds by Dobbs.

The question here is whether the Act regulates speech, conduct, or both. "While drawing the line between speech and conduct can be difficult," the precedents of the Supreme Court have long drawn that line. The district court interpreted "refer" in the Act to include "informing their patients where gender transition treatment may be available." … [But] this court should read "refer" according to its medical definition: "to send or direct for diagnosis or treatment." The whole of the Act supports this reading. The Act makes "unprofessional conduct" any "referral for or provision of" gender transition procedures for minors. This language supports that "refer" in Section 1502(b) means a formal "referral for" treatment, not merely informing patients about the availability of procedures.

Whether the Act "proscribes speech, conduct, or both depends on the particular activity in which an actor seeks to engage." A referral for treatment is not part of the "speech process." Rather, a referral is part of the treatment process for gender transition procedures.

The Act does not focus on whether a healthcare professional is "speaking about a particular topic." Instead, the Act prohibits a "healthcare professional" from providing gender transition procedures to minors. It also prohibits a "healthcare professional" from referring minors to "any health care professional for gender transition procedures." The Act defines "healthcare professional" as "a person who is licensed, certified, or otherwise authorized by the laws of this state to administer health care in the ordinary course of the practice of his or her profession." Thus, the Act prohibits a healthcare professional from referring minors to healthcare professionals for procedures that the Act prohibits them from providing. See United States v. Hansen (2023) ("Speech intended to bring about a particular unlawful act has no social value; therefore, it is unprotected."). To the extent the Act regulates speech, it does so only as an incidental effect of prohibiting the provision of gender transition procedures to minors. See Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice Co. (1949) (emphasizing that "it has never been deemed an abridgement of freedom of speech or press to make a course of conduct illegal merely because the conduct was in part initiated, evidenced, or carried out by means of language, either spoken, written, or printed").

The healthcare professional invokes National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v. Becerra. There, the Supreme Court held that requiring healthcare professionals to provide information about contraception and abortion services provided by the state was a content-based regulation of speech. But there, unlike in Casey, the compelled speech was not part of a medical procedure.

By contrast, a referral for treatment is "part of the practice of medicine." Becerra is not helpful to the healthcare professionals, because the Act does not regulate "speech as speech." This is not a case where "the only conduct which the State sought to punish was the fact of communication." Rather, the Act seeks to prohibit the conduct of providing gender transition procedures to minors. True, a referral includes "elements of speech," such as writing, typing, or verbal communication. But any restriction on speech is "plainly incidental" to the Act's regulation of conduct….

Judge Jane Kelly, joined by Judge James Loken, concurred as to the First Amendment, though noted that she read the Court's First Amendment ruling "as narrow":

The Court concludes only that a ban on formal medical referrals does not directly implicate the First Amendment. Under the Court's interpretation of Act 626, healthcare professionals remain free to discuss the possible treatments for gender dysphoria with their patients, as well as where such treatments are offered. Additionally, as the Court suggests, Slip Op. 23, the Act does not appear to prohibit doctors from referring patients to out-of-state providers for gender affirming care. See Ark. Code. Ann. § 20-9-1502(b) (prohibiting "[a] physician or other healthcare professional" from referring minors "to any healthcare professional for gender transition procedures"); id. § 20-9-1501(8) (defining a "[h]ealthcare professional" as "a person who is licensed, certified, or otherwise authorized by the laws of this state").

She argued, though, that the court should "remand for the district court to assess whether the Act survives rational basis review" under the Equal Protection Clause, reasoning that the district court's factual findings suggest that the law is irrational. For the full (long) opinions, see here.

The post Arkansas Ban on Youth Gender Transition Procedures Upheld, Including Restriction on Referrals for Such Procedures appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] The Supreme Court (Finally) Posts The October and November Calendars

After an unusually long delay, the Court has posted the calendars for October and November. The Voting Rights Act case has been consolidated for a single hour on October 15.

The post The Supreme Court (Finally) Posts The October and November Calendars appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers