Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 53

August 18, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Monday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Monday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Advice to Entering Law Students - 2025

[Some suggestions that might help you make better use of the opportunities available to you in law school.]

NA

NA Law students around the country will be starting classes over the next few weeks. Back in 2018, I wrote a post offering advice to entering students, which I updated in 2019, 2022, 2023, and last year. I tried to focus on points that I rarely, if ever, see made in other pieces of this type. I think my original suggestions remain relevant today. So I reprint my advice from earlier posts largely unaltered, with the addition of incremental edits and updates:

1. Think carefully about what kind of law you want to practice.

Law is a profession with relatively high income and social status. Yet studies repeatedly show that many lawyers are deeply unhappy, a higher percentage than in most other professions. One reason for this is that many of them hate the work they do. It doesn't necessarily have to be that way. There are lots of different types of legal careers out there, and it's likely that one of them will be a good fit for you. A person who would be miserable working for a large "Biglaw" firm might be happy as a public interest lawyer or a family law practitioner, and so on. But to take advantage of this diversity, you need to start considering what type of legal career best fits your needs and interests.

There are many ways to find out about potential options. But one place to start is to talk to the career services office at your school, which should have information about a range of possibilities. Many also often have databases of alumni working in various types of legal careers. Talking to these people can give you a sense of what life as a practitioner in Field X is really like.

This advice applies not just to what you do in school, narrowly defined, but what you do in the summer, as well. Law students typically get summer jobs at firms or other potential future employers. Apply widely, and look for organizations that might be good employers, or at least introduce you to areas of law that might be crucial for your future career.

The summer clerk job I took at the Institute for Justice after my first year in law school, was a key step towards becoming a property scholar, and helped lead me to write two books and numerous articles about takings. Spending a summer at a public interest firm might change your life, too!

Regardless, don't just "go with the flow" in terms of choosing what kind of legal career you want to pursue. The jobs that many of your classmates want may be terrible for you (and vice versa). Keep in mind, also, that you likely have a wider range of options now than you will in five or ten years, when it may be much harder to switch to a very different field from the one you have been working in since graduation.

2. Get to know as many of your classmates and professors as you reasonably can.

Law is a "people" business. Connections are extremely important. No matter how brilliant a legal thinker you may be, it's hard to get ahead as a lawyer purely by working alone at your desk - even with the help of AI and other modern tech. Many of your law school classmates could turn out to be useful connections down the road. This is obviously true at big-name national schools whose alumni routinely become judges, powerful government officials, and partners at major firms. But it's also true at schools whose reputation is more regional or local in nature. If you plan to make a career in that area yourself, many of your classmates could turn out to be useful contacts.

The same holds true for professors, many of whom have extensive connections in their respective fields. They are sometimes harder to get to know than students. But the effort is often worth it, anyway. And many of them are actually more than eager to talk about their work.

This is one front on which I didn't do very well when I was in law school, myself. Nonetheless, I still suggest you do as I say, not as I actually did. You will be better off if you learn from my mistakes than if you repeat them.

3. Think about whether what you plan to do is right and just.

Law presents more serious moral dilemmas than many other professions. What lawyers do can often cost innocent people their liberty, their property, or even their lives. It can also save all three. Lawyers have played key roles in almost every major advance for liberty and justice in American history, including the establishment of the Constitution, the antislavery movement, the civil rights movement and many others. But they have also been among the major perpetrators of most of the great injustices in our history, as well.

Robert Cover's classic book Justice Accused - a work that made a big impression on me when I was a law student - describes how some of the greatest judges and legal minds of antebellum America became complicit in the perpetuation of slavery. While we have made great progress since that time, the legal system is not as far removed from the days of the Fugitive Slave Acts as we might like to think. There are still grave injustices in the system, and lawyers whose work has the effect of perpetuating and exacerbating them. We even still have lawyers who do such things as come up with dubious rationales for deporting literal escaped slaves back to places where they are likely to face further oppression. The present administration is coming up with even more dubious rationales for doing things like using the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 (previously used only in wartime) to deport people who have not broken any laws to imprisonment, without any due process. The latter is just one of several dramatic examples of how we are now engaged in a struggle over the future of justice and the rule of law in this country.

Law school is the right time to start working to ensure that the career you pursue is at least morally defensible. You don't necessarily have a moral obligation to devote your career to doing good. But you should at least avoid exacerbating evil. And it's easier to do that if you think carefully about the issues involved now (when you still have a wide range of options), than if you wait until you are already enmeshed in a job that involves perpetrating injustice. At that point, it may be too late - both for you and (even more importantly) for the people who may be harmed.

4. Legal knowledge isn't as different from other kinds of knowledge as you might think.

Students often ask me how best to study for law school classes. My answer is that there isn't one way that's best for everyone. You probably know what works for you far better than I do.

In law school, you are likely to be bombarded with all sorts of complex methods of studying and outlining cases. Advocates of each will often tell you theirs is the One True Path to law school success. Some students really do find these methods useful.

But I would urge you to consider the possibility that you can study for law school classes by using…. much the same methods as you used to study other subjects in the past. If you were successful in social science and humanities classes as an undergraduate, the methods that worked there are likely to carry over.

I know because that's largely what I did as a law student myself. I did the reading, identified key points, and didn't bother with complicated outlines or spend money on study guides. If I did badly in a class, it wasn't for lack of more complex study methods (usually, I either got lazy or just had a bad day on the final exam). And I've seen plenty of other people succeed with similar approaches. You can save a lot of time and aggravation (and some money) that way. And that time, energy, and money can be better devoted to other purposes - including advancing your studies and your career in other ways!

Ultimately, when reading a legal decision (or any assignment), you need to 1) identify the key issues, and 2) understand why they are important. With rare exceptions, the case in question was likely included in the reading because it highlights some rule, standard, or issue that has a broader significance. If you know what that is and why it matters, much of your work is done. The same goes for most other kinds of assigned reading: they are probably there because the professor thinks they elucidate some broadly important point. Figure out what it is, and you will be in good shape.

These days, there is much discussion about the extent to which students should rely on AI to help them study. I don't have any definitive answer to that question. But, ideally, AI can augment your reading, writing, and analytical skills, but doesn't fully replace them. You should also be wary of its tendencies to hallucinate information. Use its output, but verify for accuracy. And, as with other study aids, the use of AI to study law need not be much different than its proper use for other subjects.

The experience of remote learning during the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of Point 2 above. The loss of much in-person contact was a serious problem, one we would do well to avoid repeating.

I don't think I need to dwell on how recent events have reinforced the significance of Point 3. Suffice to say there are many recent examples of lawyers facilitating both good and evil. Even if you don't maximize the former, you should at least avoid contributing to the latter.

The post Advice to Entering Law Students - 2025 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Fifth Circuit: West Texas A&M Violated First Amendment by Blocking Student Group's Drag Show

[The decision drew a sharp dissent. [UPDATE: The headline originally said Texas A & M, and has since been corrected to West Texas A & M; my apologies.]]

Some excerpts from today's long Fifth Circuit decision in Spectrum WT v. Wendler, written by Judge Leslie Southwick and joined by Judges James Dennis, which I think reaches the correct result (see the bottom of the post for my brief analysis):

Spectrum WT is an LGBT+ student organization at West Texas A&M University. It was in the last stages of organizing a drag show on campus when University President Walter Wendler canceled the show. The plaintiffs, Spectrum WT and two of its student-officers, sought a preliminary injunction on the grounds their free speech rights were violated. The district court denied the injunction, partly based on a holding that the First Amendment did not apply to the drag show. We REVERSE.

The court concluded that the First Amendment protects drag shows like it protects other theatrical productions:

We start with a Supreme Court opinion stating that "a narrow, succinctly articulable message is not a condition of constitutional protection" for expressive conduct…. Other Supreme Court opinions also have held that conduct within certain expressive settings and media is protected. For example, "live drama" implicates the First Amendment, given that "theater usually is the acting out—or singing out—of the written word, and frequently mixes speech with live action or conduct." Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v. Conrad (1975). Films are no different. Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson (1952). Violent video games also fall under First Amendment doctrine. Brown v. Ent. Merchs. Ass'n (2011)….

Having set out the relevant principles, we now examine the plaintiffs' intended drag show. It would have included costumed performers with stage names, occurred on a stage, and mixed the spoken and sung word with the show's physical components while songs played in the background. Cf. Southeastern Promotions (describing a production of Hair as protected expression)…. In the present dispute, it is evident that a message in support of LGBT+ rights was intended, which is a far clearer message than some of the examples of art identified in Hurley as protected by the First Amendment….

Whether conduct is communicative is [also] explained in part by societal and temporal context. A drag show can communicate a message of solidarity and support for the LGBT+ community. Drag shows—with performers dancing and speaking to music on stage in clothing associated with the opposite gender—mark a deliberate and theatrical subversion of gender-based expectations and signify support for those who feel burdened by such expectations….

The court then concluded that Legacy Hall was a "designated public forum"—government property voluntarily opened up for public access—and that speech there was protected against content-based speech restriction as much as in traditional public fora, such as parks. And the court concluded the drag show ban was a forbidden content-based restriction:

The restriction here describes impermissible expression "not in terms of time, place, and manner, but in terms of" content, i.e., a drag show. The ban abandons "the neutrality of time, place, and circumstance" and becomes "a concern about content." … President Wendler did not argue, either before the district court or on appeal, that restricting the intended drag show would survive strict scrutiny [i.e., the compelling interest test]. Based on the record before us, the district court erred in concluding that the plaintiffs were not substantially likely to succeed on the merits of their First Amendment claim.

Judge James Ho dissented; again, an excerpt from the long dissent:

Spectrum WT claims that it has a First Amendment right to put on a drag show in a public facility at West Texas A&M University. But university officials have determined that drag shows are sexist, for the same reason that blackface performances are racist. And Supreme Court precedent demands that we respect university officials when it comes to regulating student activities to ensure an inclusive educational environment for all. See Christian Legal Society v. Martinez (2010).

I disagree with the Supreme Court's decision in CLS. But I'm bound to follow it. And I will not apply a different legal standard in this case, just because drag shows enjoy greater favor among cultural elites than the religious activities at issue in CLS….

Members of the CLS chapter at the Hastings College of the Law sought to exercise their First Amendment right to associate with fellow believers who share their Biblical views on marriage and sexuality—just as politically affiliated student groups at Hastings have been allowed to associate with fellow partisans who share their ideological priors. But university officials chose to expel CLS—and only CLS—from campus. And the Supreme Court sided with university officials over CLS.

In doing so, the Court acknowledged that forcing an organization to accept unwelcome members "directly and immediately affects associational rights" ordinarily protected by the First Amendment. But the Court insisted that the First Amendment must be analyzed differently in "the educational context" and "in light of the special characteristics of the school environment." …

[U]ntil the Court itself overturns CLS, we're bound to follow it. And if we're bound to respect university officials when they regulate Christian groups over (contrived) concerns about discrimination, then we're surely bound to respect university officials when they regulate other groups over concerns about discrimination. We should apply the same First Amendment principles, whether the views are embraced or abhorred by cultural elites.

It would turn the First Amendment upside down to give greater protection to drag shows than devotional acts. That would violate the Constitution under the guise of enforcing it. It would discriminate not only on the basis of viewpoint, but on the basis of religion as well—in violation of not just the Free Speech Clause, but the Free Exercise Clause, too….

West Texas A&M President Walter Wendler concluded that drag shows are demeaning to women. As he explained in an open letter to the community, "WT endeavors to treat all people equally. Drag shows are derisive, divisive and demoralizing misogyny, no matter the stated intent. Such conduct runs counter to the purpose of WT. A person or group should not attempt to elevate itself or a cause by mocking another person or group."

In opposing drag shows as derogatory towards women, Wendler compared them to blackface performances. "As a university president, I would not support 'blackface' performances on our campus …. I do not support any show, performance or artistic expression which denigrates others—in this case, women—for any reason."

Wendler is hardly the first member of the academy to regard drag shows as sexist—or to compare them to blackface performances, which are widely condemned as racist. As one scholar has observed, "the same arguments that forged the cultural consensus against blackface should forge a consensus against drag."

Drag shows "represent institutionalized male hostility to women." They "may be glamorous or comic, and presented by gay men or straight men," but they all "represent a continuing insult to women, as is apparent from the parallels between these performances and those of white performers of blackface minstrelsy."

In sum, "[d]rag is misogynistic, no matter who performs it." See also, e.g., Dr. Grace Barnes, Drag: a sexist caricature, or a fabulous art form?, The Guardian (Apr. 7, 2024) ("Drag can be compared to blackface and yellowface: those holding the reins of power utilise performance to mock those without power through a demeaning parody…. [I]t is … exclusionary, sexist and insulting to women."); Meghan Murphy, Why has drag escaped critique from feminists and the LGBTQ community?, Feminist Current (Apr. 25, 2014) ("Why do we despise performance in blackface and celebrate performance in drag?").

So it's not surprising that university officials across the country have opposed drag shows as demeaning to women. In IOTA XI Chapter of Sigma Chi Fraternity v. George Mason University (4th Cir. 1993), for example, university administrators and student leaders were upset that a fraternity hosted an event in which men "dressed as caricatures of different types of women." Campus officials concluded that the event had "created a hostile learning environment for women" and was therefore "incompatible with the University's mission." One dean stated in an affidavit that the event "perpetuated derogatory … sexual stereotypes" and was "incompatible with, and destructive to, the University's mission of promoting diversity within its student body." The official worried that the event "sends a message to the student body and the community that we are not serious about hurtful and offensive behavior on campus." Hundreds of students protested, similarly condemning the "sexist implications of this event in which male members dressed as women." University officials ultimately sanctioned the fraternity for hosting the event. (The court's decision preceded, and thus was not bound by, the Supreme Court's decision in CLS.) …

The dissent also went on to argue that the forum in this case should be viewed as a limited public forum, where content-based but viewpoint-neutral restrictions are allowed (so long as they are reasonable), rather than a designated public forum.

I think that the majority reached the correct result, indeed regardless of whether the forum is viewed as a designated public forum or a limited public forum: If the rationale for the drag show ban is that drag shows are "sexist" (or, for that matter, if one adopts a different rationale that drag shows support improper views of gender), that just means that the ban is viewpoint-based, and thus unconstitutional in a limited public forum as well.

Indeed, the Court in CLS took pains to make clear that it upheld the policy there—which required student groups to accept all prospective members—because it viewed the policy as viewpoint-neutral, and that viewpoint-based campus speech restrictions would remain unconstitutional:

Although registered student groups must conform their conduct to the Law School's regulation by dropping access barriers, they may express any viewpoint they wish—including a discriminatory one. Cf. Rumsfeld v. FAIR (2006) ("As a general matter, the Solomon Amendment regulates conduct, not speech. It affects what law schools must do—afford equal access to military recruiters—not what they may or may not say."). Today's decision thus continues this Court's tradition of "protect[ing] the freedom to express `the thought that we hate.'"

Likewise, even if drag shows' message is seen as "sexist" and therefore "discriminatory," CLS offers no basis for upholding the ban. Indeed, CLS began by making clear that viewpoint discrimination remains forbidden even in limited public fora:

In a series of decisions, this Court has emphasized that the First Amendment generally precludes public universities from denying student organizations access to school-sponsored forums because of the groups' viewpoints. See Rosenberger v. Rector and Visitors of Univ. of Va. (1995) [a limited public forum case -EV]; Widmar v. Vincent (1981); Healy v. James (1972).

Spectrum WT is represented by Adam Steinbaugh, Conor Fitzpatrick, JT Morris, and Jeffrey Daniel Zeman (Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression). Note that I have consulted in the past for FIRE, as well as represented them pro bono and have been represented by them pro bono; but I didn't work with them on this case. Note also that I am an amicus and one of the cocounsel (together with Dale Carpenter) in a different drag show case that raised related issues, Woodlands Pride, Inc. v. Paxton.

The post Fifth Circuit: West Texas A&M Violated First Amendment by Blocking Student Group's Drag Show appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Free Speech Unmuted: Free Speech and Doxing

For those interested in reading more about the subject, here's a post of mine from January:

The term "doxing" is not well defined, but is often used broadly to refer to publicly disclosing a person's name, photograph, address, phone number, employer name, and the like, in connection with some express or implied condemnation of the person. The concern is that such disclosure can instigate or facilitate violence or vandalism targeting the person, or the sending of threats, or the sending of insulting messages, or economic retaliation (often through the person's employer). Different states have different rules dealing with such matters, and they generally define "doxing" differently, both as to what information is covered, who is protected against such disclosure, what (if any) specific purposes on the discloser's part must be shown to lead to liability, and more.

In any case, in thinking about the subject (and especially the questions that aren't limited to information such as social security numbers, bank account numbers, and the like), I came up with a set of hypotheticals that I hoped might be helpful. If any of you are interested in this, I'd love to hear your thoughts about which, if any, of these situations should lead to, say, criminal or civil liability (and, briefly, why). One can of course think that none should lead to liability—at least unless the allegations are false and therefore libelous, or are part of a criminal conspiracy involving the speaker, or involve some other factual feature not included in the hypothetical—or one can think that all should, or one can come to some conclusion in between.

Some doxing rules might not involve criminal or civil liability, and might not be subject to First Amendment restraints: For instance, a private university might restrict such speech by its students (especially about other students, staff, or faculty), or a social media platform might restrict such speech on the platform, or a newspaper might set up editorial policies about what kinds of material it publishes. But for purposes of this comment thread, I thought it would be good to focus on criminal or civil liability.

[1.] Dentist Who Shot Cecil the Lion: In 2015, Minnesota dentist Walter Palmer was publicly "named and shamed" through many people's social media posts for killing Cecil, a famous Zimbabwe lion, on a hunting trip. This led to likely economic harm to his practice, and to his "receiv[ing] a slew of death threats on social media." How the Internet Descended on the Man Who Killed Cecil the Lion, BBC, July 29, 2015. Assume the posts identified Palmer and the name of his dental practice.

[2.] Central Park Karen:

The white woman dubbed "Central Park Karen" when a video of her confrontation with a black birdwatcher went viral three years ago [in 2020] says she is still living in hiding and struggling to stay employed.

Amy Cooper claimed in a new opinion piece for Newsweek that she has received an endless flurry of hate mail that told her she deserves to be raped in prison or to kill herself and referred to her as a "Karen"—a term used for white women who victimize people of color—since the 2020 encounter in the Manhattan park….

Cooper was fired from her job as an insurance portfolio manager at Franklin Templeton Investments within 24 hours of the viral confrontation on May 25, 2020—the same day that George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis, sparking a national reckoning over racism.

She was caught on camera yelling at science and comic book writer Christian Cooper (no relation) and calling the police to claim an "African American man" was "threatening" her while she was walking her dog in the Ramble in Central Park….

Cooper was charged by Manhattan prosecutors in July 2020 with falsely reporting an incident—and while the rap was ultimately tossed after she attended therapy sessions on racial bias, she still lost her job.

Olivia Land, NYC's 'Central Park Karen': I Still Live in Hiding Three Years After Viral Video, N.Y. Post, Nov. 7, 2023. Assume some of the posts included the video, her name, and the name of the employer.

[3.] Accused Child Molester: A newspaper reports on allegations of child molestation against a local resident, and includes the man's name and place of employment (e.g., the school through which the molestation allegedly occurred). As a result, the man or his family get death threats. This is based, with the addition of the place of employment, on Ashleigh Panoo, His Twin Brother Allegedly Molested a Girl. Now He's Getting Death Threats, Fresno Bee, Jan. 13, 2018. (The Fresno Bee story doesn't indicate whether the threats came as a result of newspaper coverage, but it seems likely they would, in this case or in some other.)

[4.] Boycott Noncomplier: An NAACP chapter organizes a black boycott of white-owned stores. "Store watchers" stand outside stores and write down the names of black residents who aren't going along with the boycott; the names are then "read aloud at meetings at the First Baptist Church and published in a local black newspaper." Apparently as a result, there are crimes against some violators: three incidents of shots fired into homes, "a brick … thrown through a windshield," "a flower garden [being] damaged," and two beatings. The addresses of the targeted people aren't published, but they are presumably known in the community. These are basically the facts of NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware, 458 U.S. 886 (1982).

[5.] Palestinian Advocates: A truck with a billboard bearing the words "Columbia's Leading Antisemites" alongside the names and faces of students and faculty is circling around the Columbia campus. The truck lists 29 Columbia students and faculty who allegedly signed a statement of Palestinian solidarity; so does a website titled "Columbia Hates Jews," run by the same conservative group that hired the truck. The website states that the people listed belong to various pro-Palestinian campus groups who signed statements of solidarity with Palestinians and opposition to Israel in the days following the Oct. 7 attacks; the website's operators view those statements as expressing support for the attacks.

The website calls on readers to send messages to Columbia's board of trustees urging them to "take a stand" against "these hateful individuals." The group has also bought the Internet domain names that correspond to the actual names of several students and faculty on the list. The truck also regularly patrols outside the targets' homes. Two law students who were targeted by the truck had job offers withdrawn by prestigious New York law firms. See Esha Karam, 'Doxxing Truck' Displaying Names and Faces of Affiliates It Calls 'Antisemites' Comes to Columbia, Columbia Spectator, Oct. 25, 2023; Sabrina Ticer-Wurr, Nearly Two Dozen Palestinian Solidarity Groups Release Open Letter, Joint Statement, Columbia Spectator, Oct. 11, 2023.

[6.] Real Estate Broker: A self-described civil rights group believes that a local real estate agent is engaging in sales practices that undermine the group's goal of having a racially integrated community. (Assume that the practices are legal.) To pressure the agent, they "distribute[] leaflets" in the agent's home town describing and criticizing his actions. They do this each week for several weeks at local shopping malls; twice, they distribute leaflets "to some parishioners on their way to or from [the agent's] church"; they also leave leaflets "at the doors of his neighbors." "The … leaflets gave plaintiff's home address and telephone number and urged [the home town's] residents to call [the agent] and tell him to" agree to the group's demands that he change his practices. These are basically the facts of Organization for a Better Austin v. Keefe, 402 U.S. 415 (1971).

[7.] School Board Member: Three School Board members—elected officials, who serve part-time—take a controversial stand on the display of Black Lives Matter materials in local schools. Three parents post online the names and phone numbers of the members' employers, hoping that readers will pressure the employers (e.g., through threat of boycott) into pressuring the members to change their positions. Assume that some readers do call the employers, which makes the members fear for their careers. Assume also that a few readers also send threatening e-mails to the officials personally (by finding the e-mail addresses on the Board's website). This is loosely based on the facts of DeHart v. Tofte, 326 Ore. App. 720 (2023).

[8.] Police Chief: Charles Kratovil, founder and editor of the online publication New Brunswick Today, believes that New Brunswick police chief Anthony Caputo is living in Cape May, two hours away from New Brunswick. He wants to write about this, and to include a voter record that he has obtained from some government agency that shows Caputo's home address. Caputo demands that Kratovil not do this, because Caputo is concerned that people might use the information to physically attack Caputo or his family, or at least vandalize his home. These are basically the facts of Kratovil v. City of New Brunswick, now pending before the New Jersey Supreme Court (see 258 N.J. 468 (2024), granting review of 2024 WL 1826867 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. Apr. 26, 2024)). [The New Jersey Supreme Court has since ruled against Kratovil, upholding the state law that let government officials demand that their home addresses not be published. -EV]

[9.] Judge: John Smith, a disgruntled litigant who is unhappy about Judge Mary Jones' decisions in his now-completed divorce case posts a website accusing Judge Jones of being biased against men. He includes Jones' photograph and home address, and encourages people to join him in picketing her home. Some people leave threatening messages for Jones at her home; others do indeed join him for the picketing. Assume that residential picketing is not illegal in that jurisdiction.

[10.] Election Worker: William Johnson posts a video of a poll worker, accompanied with (1) a note saying that Johnson thinks the actions depicted on the video might be indicative of election fraud, and (2) a request for information about who the poll worker is. An anonymous commenter posts the poll worker's name, and the name of the poll worker's employer. That in turn leads to anonymous threats sent to that poll worker, and demands sent to the employer to fire the poll worker.

[* * *]

See also our past episodes:

The Supreme Court Rules on Protecting Kids from Sexually Themed Speech OnlineFree Speech, Public School Students, and "There Are Only Two Genders"Can AI Companies Be Sued for What AI Says?Harvard vs. Trump: Free Speech and Government GrantsTrump's War on Big LawCan Non-Citizens Be Deported For Their Speech?Freedom of the Press, with Floyd AbramsFree Speech, Private Power, and Private EmployeesCourt Upholds TikTok Divestiture LawFree Speech in European (and Other) Democracies, with Prof. Jacob MchangamaProtests, Public Pressure Campaigns, Tort Law, and the First AmendmentMisinformation: Past, Present, and FutureI Know It When I See It: Free Speech and Obscenity LawsSpeech and ViolenceEmergency Podcast: The Supreme Court's Social Media CasesInternet Policy and Free Speech: A Conversation with Rep. Ro KhannaFree Speech, TikTok (and Bills of Attainder!), with Prof. Alan RozenshteinThe 1st Amendment on Campus with Berkeley Law Dean Erwin ChemerinskyFree Speech On CampusAI and Free SpeechFree Speech, Government Persuasion, and Government CoercionDeplatformed: The Supreme Court Hears Social Media Oral ArgumentsBook Bans – or Are They?The post Free Speech Unmuted: Free Speech and Doxing appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Judge Quashes FTC Investigative Demand to Media Matters, Finding "Straightforward First Amendment Violation"

A short excerpt from Friday's long decision by Judge Sparkle Sooknanan (D.D.C.) in Media Matters for America v. FTC:

Speech on matters of public concern is the heartland of the First Amendment. The principle that public issues should be debated freely has long been woven into the very fabric of who we are as a Nation. Without it, our democracy stands on shaky ground. It should alarm all Americans when the Government retaliates against individuals or organizations for engaging in constitutionally protected public debate. And that alarm should ring even louder when the Government retaliates against those engaged in newsgathering and reporting.

This case presents a straightforward First Amendment violation. Media Matters for America is a nonprofit media company that is over two decades old. In November 2023, it ran a story reporting that as a result of Elon Musk's acquisition of Twitter (now "X"), advertisements on the social media platform were appearing next to antisemitic posts and other offensive content. Mr. Musk immediately promised to file "a thermonuclear lawsuit against Media Matters." And he followed through. In the weeks and months that followed, X Corp. and its subsidiaries sued Media Matters all over the world, at least until a federal district court preliminarily enjoined this aggressive litigation strategy. Meanwhile, seemingly at the behest of Steven Miller, the current White House Deputy Chief of Staff, the Missouri and Texas Attorneys General issued civil investigative demands (CIDs) to Media Matters, both of which were preliminarily enjoined in this Court as likely being retaliatory in violation of the First Amendment.

But these court victories did not end the fight for Media Matters. Now the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has taken up the cause. After Andrew Ferguson took on his new role as the Chairman of the FTC, the agency issued a sweeping CID to Media Matters, purportedly to investigate an advertiser boycott concerning social media platforms. That CID should have come as no surprise.

Before President Trump selected him to head the FTC, Mr. Ferguson appeared on Steve Bannon's podcast, where he said that it is "really important that the FTC take investigative steps in the new administration under President Trump" because "progressives" and others who are "fighting "disinformation" were "not going to give up just because of the election." One of his supporters, Mike Davis, who urged President Trump to nominate him to the role, made several public comments about Media Matters, including that Mr. Musk should "nuke" the media company. And after taking the reins, Chairman Ferguson brought on several senior staffers at the FTC who previously made public comments about Media Matters.

Media Matters brought this lawsuit to challenge the FTC's CID, alleging that it is retaliatory in violation of the First Amendment and that it is overbroad in violation of the Fourth and First Amendments. Before the Court is a motion seeking preliminary injunctive relief from the CID. The Court agrees that a preliminary injunction is warranted….

Media Matters … alleges that the "Defendants violated, and continue to violate, [its] First Amendment rights by launching an investigation and serving a burdensome CID in retaliation for [Media Matters'] speech, press, and associational activities." "[T]he law is settled that … the First Amendment prohibits government officials from subjecting an individual to retaliatory actions … for speaking out." To prevail on a retaliation claim, a plaintiff must show: "(1) he engaged in conduct protected under the First Amendment; (2) the defendants took some retaliatory action sufficient to deter a person of ordinary firmness in plaintiff's position from speaking again; and (3) a causal link between the exercise of a constitutional right and the adverse action taken against him." At this preliminary stage, Media Matters has demonstrated that it is likely to show all three elements, so the Court finds that it is likely to succeed on the merits of this claim….

Here's the court's analysis of the second prong; for more on the third prong (the first was uncontested), read the full opinion:

Media Matters is … likely to show that the Defendants took a retaliatory action sufficient to deter a person of ordinary firmness in Media Matters' position from speaking again. This is because the FTC issued a sweeping and burdensome CID calling for sensitive materials. See White v. Lee (9th Cir. 2000) (holding an "investigation by … HUD officials" "more than meets" the standard requiring an act that "would chill or silence a person of ordinary firmness from future First Amendment activities" where the defendants "directed the plaintiffs under threat of subpoena to produce all their publications regarding [a certain] project, minutes of relevant meetings, correspondence with other organizations, and the names, addresses, and telephone numbers of persons who were involved in or had witnessed the alleged discriminatory conduct"); Cooksey v. Futrell (4th Cir. 2013) (holding "[a] person of ordinary firmness would surely feel a chilling effect" where an official told the plaintiff "that he and his website were under investigation and that the State Board does have the statutory authority to seek an injunction[.]").

This is especially true where, as here, "[t]he CID seeks" "a reporter's resource materials." A reporter of ordinary firmness would be wary of speaking again if she had to reveal the materials requested by this fishing expedition of a CID. See, e.g., Compl., Ex. D at 2, ECF No. 1-4 ("Provide all analyses or studies that Media Matters conducted, sponsored, or commissioned relating to advertising on social media or digital advertising platforms, including but not limited to any financial analyses or studies, and all data sets and code that would be necessary to replicate the analysis."); id. ("Provide documents sufficient to show the methodology by which Media Matters evaluates or categorizes any news, media, sources, platforms, outlets, websites, or other content publisher entities."); id. at 2–3 ("Provide all communications between Media Matters and any other person regarding any request for Media Matters to label any news, media, sources, outlets, platforms, websites, or other content publisher entities for 'brand suitability,' 'reliability,' 'misinformation,' 'hate speech,' 'false' or 'deceptive' content, or similar categories, regardless of whether the request was fulfilled."); id. at 3 ("Provide all documents, including correspondence, relating to Media Matters working with ad tech, technology, or developer companies or social media platforms to develop or advance any of [Media Matters'] programs, policies, or objectives, including but not limited to any agreements between Media Matters and these companies."); id. ("Provide each financial statement … prepared by or for Media Matters on any periodic basis."); see also id. at 4 (defining "Media Matters" to mean "Media Matters for America, together with its successors, predecessors, divisions, wholly- or partially-owned subsidiaries, committees, working groups, alliances, affiliates, and partnerships, whether domestic or foreign; and all the directors, officers, employees, consultants, agents, and representatives of the foregoing. Identify by name, address, and phone number, each agent or consultant.")….

The Defendants' main counterargument on the retaliatory act element is that "there is a significant question whether a retaliatory investigation claim is even cognizable." And they point to out-of-circuit cases holding state and local actors were protected by qualified immunity because retaliatory criminal investigations were not clearly violative of the First Amendment. See Archer v. Chisholm (7th Cir. 2017) (holding defendants are protected by qualified immunity where they allegedly engaged in a retaliatory criminal investigation because the plaintiff's asserted right was not "clearly established" given Supreme Court precedent stated that "the first amendment does not protect statements made as part of one's job" and the plaintiff's purportedly protected "activities were part of her job as a public employee" (cleaned up)); Rehberg v. Paulk (11th Cir. 2010) ("But even if we assume Rehberg has stated a constitutional violation by alleging that Hodges and Paulk initiated an investigation and issued subpoenas in retaliation for Rehberg's exercise of First Amendment rights, Hodges and Paulk still receive qualified immunity because Rehberg's right to be free from a retaliatory investigation is not clearly established."); Thompson v. Hall (11th Cir. 2011) (per curiam) ("Defendants Sheriff Hall and Deputy Utsey are entitled to qualified immunity insofar as Plaintiffs have alleged they carried out an investigation in 2005 in retaliation for Plaintiff Daniel Thompson's comments at the town hall meeting."); J.T.H. v. Missouri Dep't of Soc. Servs. Children's Div. (8th Cir. 2022) (holding "the complaint falls short of establishing that Cook violated a clearly established right" because "we have never recognized a retaliatory-investigation claim of this kind"); see also Sivella v. Twp. of Lyndhurst (3d Cir. 2011) ("We … conclude that … when [the mayor] sent a letter requesting the initiation of an investigation of no-show municipal jobs by the Township Chief of Police, allegedly in retaliation for Sivella's protected speech, it was not clearly established that such an adverse action amounted to a First Amendment violation.").

But the standard for qualified immunity is higher than what is required for preliminary injunctive relief. Indeed, the Ninth Circuit simultaneously held that it is not "clearly established that a retaliatory investigation per se violates the First Amendment" and that "[t]he scope and manner of the investigation" in White v. Lee (9th Cir. 2000), "violated plaintiffs' First Amendment rights."

The Defendants also cite language from three out-of-circuit opinions unrelated to qualified immunity. But the first case merely held that a retaliatory investigation did not amount to an adverse employment action under the First Amendment retaliation test for public employees—a test that is not at issue here. See Breaux v. City of Garland (5th Cir. 2000) ("[I]nvestigating alleged violations of departmental policies and making purportedly false accusations are not adverse employment actions."). And it even acknowledged that such an investigation could have a chilling effect. See id. ("This court has declined to expand the list of actionable actions, noting that some things are not actionable even though they have the effect of chilling the exercise of free speech" "to ensure that § 1983 does not enmesh federal courts in relatively trivial matters.").

It is true that the second and third cases squarely held that "a criminal investigation in and of itself does not implicate a federal constitutional right." Thompson; Rehberg. But that language does not foreclose the possibility that certain investigatory acts may cross the line when they come with particularly adverse consequences. And the FTC's CID has had plenty of knock-on effects according to Media Matters' declarants; it is "driving additional costs," it has caused "retention challenges," and it has resulted in Media Matters being "removed from coalition communications" "about FTC actions." It is hard to imagine any media company not being chilled by this sweeping and sensitive CID. The Court is therefore unpersuaded that these non-binding opinions render Media Matters unlikely to succeed on the merits of their retaliation claim.

The Defendants' argument is further undercut by D.C. Circuit precedent new and old. In Media Matters for America v. Paxton, the Texas Attorney General had forfeited the argument that "a retaliatory investigation is not a cognizable claim," so the Court did not address it head-on. But when discussing Media Matters' injury-in-fact for standing purposes, the Court quoted broad non-standing language from a prior opinion: "In distinguishing between 'good faith' and 'bad faith' investigations, this court has explained that 'all investigative techniques are subject to abuse and can conceivably be used to oppress citizens and groups,' and that bad faith use of investigative techniques can abridge journalists' First Amendment rights." It explained that "the First Amendment 'protect[s] [information-gathering] activities from official harassment,' and that 'official harassment [of the press] places a special burden on information-gathering, for in such cases the ultimate, though tacit, design is to obstruct rather than to investigate, and the official action is proscriptive rather than observatory in character.'"

The older D.C. Circuit opinion pulled no punches, stating that "there can be no doubt that, as a general proposition," the issuance of subpoenas "not in furtherance of Bona fide felony investigations, but in order to harass plaintiffs in their journalistic information-gathering activities," "would constitute an abridgement of a journalist's First Amendment rights." Reps. Comm. for Freedom of the Press; see also Branzburg v. Hayes (1972) ("[N]ews gathering is not without its First Amendment protections, and grand jury investigations if instituted or conducted other than in good faith, would pose wholly different issues for resolution under the First Amendment."); United States v. Morton Salt Co. (1950) (saying an agency's "power of inquisition" is "analogous to the Grand Jury"). So the Court sees no reason why the FTC's CID cannot amount to a sufficient retaliatory act as a matter of law….

The post Judge Quashes FTC Investigative Demand to Media Matters, Finding "Straightforward First Amendment Violation" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] No Qualified Immunity as to Allegations that Pre-K School Principal Failed to Respond to Sexual Molestation of Student by Teacher

From Doe v. Jewell, decided Friday by Fifth Circuit Judge Patrick Higginbotham, joined by Judges Don Willett and James Ho:

Parents of a pre-kindergarten student bring claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 against April Jewell, a school principal, for failure to respond to sexual molestation of their daughter by a faculty member. The district court denied Jewell's motion to dismiss on the basis of qualified immunity finding that she failed her duty to protect the student. We AFFIRM….

Jane [Doe] brings two claims: (A) that her Fourteenth Amendment right to bodily integrity was violated by Jewell's failure to supervise; and (B) that Jewell's conduct constituted arbitrary and conscience-shocking executive action….

As to bodily integrity and failure to supervise, the panel set forth the Fifth Circuit rule:

A supervisory school official can be held personally liable for a subordinate's violation of "an elementary or secondary school student's constitutional right to bodily integrity in physical sexual abuse cases." Three hurdles await putative plaintiffs:

(1) the defendant learned of facts or a pattern of inappropriate sexual behavior by a subordinate pointing plainly toward the conclusion that the subordinate was sexually abusing the student;

(2) the defendant demonstrated deliberate indifference toward the constitutional rights of the student by failing to take action that was obviously necessary to prevent or stop the abuse; and

(3) such failure caused a constitutional injury to the student….

Doe v. Taylor Indep. Sch. Dist. (5th Cir. 1994) (en banc).

And it went on to apply Taylor:

The Does allege that by the end of March 2021, a minimum of three school employees [Sams, Peebles, and Willis] had reported to Jewell significant concerns with Crenshaw's behavior towards Jane. Such behavior includes Jane sitting in Crenshaw's lap; Jane wearing Crenshaw's clothes; Jane holding Crenshaw's hand; Crenshaw locking the door while he was the only adult in the room; and Crenshaw lying underneath a blanket with Jane during nap time. Taken together, these actions constitute inappropriate sexual behavior and point toward the conclusion that Crenshaw—Jewell's subordinate—was sexually abusing a student.

Jewell not only knew about this behavior; she also was present at a meeting where multiple employees discussed Crenshaw's habit of being alone with students and locking the door to his classroom. And, Jewell knew that Sams' photographs of Crenshaw depicted inappropriate behavior. Jewell may be correct that some of the above actions by a teacher can be innocent. But Crenshaw's oft-reported behavior creates a pattern of inappropriate sexual behavior pointing directly to sexual abuse of Jane….

The Plaintiffs allege that Jewell did not properly investigate, reprimand, or warn Crenshaw; inform Jane's parents of the concerns and complaints made against him; or report Crenshaw's misconduct to law enforcement. Plaintiffs further allege that Jewell disregarded numerous reports over the course of an entire school year of excessive physical and sexually-charged contact with and "favoritism" of certain students. Moreover, Jewell's decision to reprimand Sams and subdivide the classrooms may have made it easier for Crenshaw to be alone with Jane and other students. While Jewell reassigned Willis to another room, the effect was to remove another pair of watchful eyes.

The complaint sufficiently alleges deliberate indifference by Jewell towards the repeated reports of Crenshaw's sexually inappropriate behavior and, in turn, to Jane's bodily integrity. Accepting the factual allegations as true, Jewell did nothing to stop the abuse, and nothing to free herself from liability through the litany of examples in our caselaw where principals were able to defeat accusations of deliberate indifference….

Plaintiffs urge that Jewell intervened in ways that increased Jane's exposure to Crenshaw's sexual predation and caused her to be molested repeatedly over an entire school year. On the present record, Jewell reprimanded and removed concerned adults from Jane's orbit and failed to alert Jane's parents, despite repeated reports by her subordinates….

As to the shocks-the-conscience theory, the panel reasoned:

The "shocks-the-conscience test" is a demanding and difficult test to apply. "It has been described as conduct that 'violates the decencies of civilized conduct'; conduct that is 'so brutal and offensive that it [does] not comport with traditional ideas of fair play and decency'; conduct that 'interferes with rights implicit in the concept of ordered liberty'; and conduct that 'is so egregious, so outrageous, that it may fairly be said to shock the contemporary conscience.'" But the Supreme Court has "made it clear that the due process guarantee does not entail a body of constitutional law imposing liability whenever someone cloaked with state authority causes harm." The Court has identified "conduct intended to injure in some way unjustifiable by any government interest" as "the sort of official action most likely to rise to the conscience-shocking level."

That said, the test is not confined to intentional acts—it also reaches certain instances of deliberate indifference. "To act with deliberate indifference, a state actor must consciously disregard a known and excessive risk to the victim's health and safety." The Supreme Court has cautioned against rote application of that standard: "Deliberate indifference that shocks in one environment may not be so patently egregious in another, and our concern with preserving the constitutional proportions of substantive due process demands an exact analysis of circumstances before any abuse of power is condemned as conscience shocking." We must therefore evaluate the allegations here without "fastidious squeamishness or private sentimentalism."

Knowledge of danger plays an important role in our analysis of a state actor's inaction. "[T]his court has never required state officials to be warned of a specific danger. Rather, we have held that 'the official must be both aware of facts from which the inference could be drawn that a substantial risk of serious harm exists, and he must also draw the inference.' " And "we may infer the existence of this subjective state of mind from the fact that the risk of harm is obvious."

Here, the pleaded facts present a stark picture. When told a grown man was lying under a blanket with a young girl, Jewell reprimanded—not the man—but the staff member who spoke up. When informed that photos documented additional inappropriate conduct, Jewell scolded the aide who took them and refused even to look. And as concerns mounted, she brushed them off, telling subordinates, "we can't be picky" about who cares for young children.

The danger to Doe and her pre-kindergarten classmates was obvious. Admittedly, Plaintiffs likely cannot show that Jewell consciously concluded that Crenshaw was molesting students. But they do allege that she refused to view photographic evidence of pedophilic behavior, and that she met employee concerns with hostility. This shifts Crenshaw's misconduct from "possible" to "obvious." Multiple employees complained; some had photographic proof. Jewell's reaction was struthious inaction.

These allegations, if proven, depict a school official who "failed to act despite h[er] knowledge of a substantial risk of serious harm" to her students—conduct that can qualify as conscience-shocking. This conclusion is anchored in context: deliberate indifference by a school official to suspected sexual abuse. In Taylor, we recognized a student's "constitutional right to bodily integrity in physical sexual abuse cases," relying on "shocks-the-conscience" precedent. Taylor thus treats supervisory deliberate indifference in the school-abuse setting as the functional equivalent of conscience-shocking conduct. While not every Fourteenth Amendment violation meets that high bar, here—given the context and allegations—Jewell's deliberate indifference does.

And the court concluded that the law on this was so clearly established that defendant was rightly denied qualified immunity:

At least since 1987, students have enjoyed a clearly established substantive due process right to bodily integrity under the Fourteenth Amendment that is violated by sexual abuse by a school employee. It is also well-established that a supervisory school official may be liable for breaching the duty to stop or prevent child abuse. Its contours are sufficiently clear given the breadth of the Taylor opinion and litigation that followed. Given our multi-prong test established by the en banc court, as well as lengthy cases applying Taylor with detailed fact patterns, we are persuaded that this right was clearly established by the 2020-2021 school year….

Judge Higginbotham and the other panel members disagreed on one item: Judge Higginbotham added a footnote that he "would not invoke [the shocks-the-conscience] doctrine here, as in his view it is a judicial creature responding to voids in the reach of § 1983. With Taylor on the books, that void here has been filled. With no void, the shocks-the-conscience test does no work." But Judges Willett and Ho declined to join this footnote, and Judge Ho wrote a concurrence on the subject:

It should shock the conscience if a school principal's extreme dereliction of duty predictably results in the sexual abuse of a five-year-old girl by a suspected pedophile on the faculty.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that governmental action that "shocks the conscience" violates the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. The Court has further held that deliberate indifference can in some circumstances shock the conscience.

The members of the panel today unanimously agree with the district court that, if the allegations in this case are proven at trial, April Jewell was indeed deliberately indifferent to keeping a sexual predator on her school's faculty. To put it simply, Jewell ignored an obvious risk of serious harm to a student in her care. And that's enough to establish deliberate indifference under governing precedent.

When told that a grown man was caught lying under a blanket with a young girl, Jewell reprimanded the staff member who spoke up. When informed that there were photos showing additional inappropriate behavior, Jewell scolded the classroom aide who took the photos and refused to look at them. When concerns grew, she brushed them off, telling her subordinates that "we can't be picky" about who we entrust to care for young children. And she declined to report any of this to the child's parents.

This is a shocking betrayal of public trust in school administrators.

To be sure, the "shocks the conscience" theory of the Due Process Clause has come under withering criticism in both judicial and academic circles. But until the Supreme Court overturns its own precedent, it remains binding on us as an inferior court.

So we have had no trouble enforcing the "shock the conscience" standard against excessively large monetary damage awards—despite sharp criticism in certain quarters. See, e.g., Caldarera v. Eastern Airlines, Inc. (5th Cir. 1983) (noting that excessive awards "shock the judicial conscience" and ordering remittitur); Wackman v. Rubsamen (5th Cir. 2010). But see, e.g., BMW v. Gore (1996) (Scalia, J., dissenting) (criticizing use of the Due Process Clause to combat excessive damage awards).If a disappointing hit to a company's bottom line can shock the conscience, then surely so too can a principal who is willfully blind as a child's innocence is destroyed at the hands of a pedophile….

Monica Beck (Law Office of Monica Beck, P.L.L.C.), Rachael J. Denhollander (Fierberg National Law Group), and Jeffrey Green (Law Office of Jeff Green, P.C.) represent plaintiffs.

The post No Qualified Immunity as to Allegations that Pre-K School Principal Failed to Respond to Sexual Molestation of Student by Teacher appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Attempt to Get Government Documents About Anthony Pellegrino and Goldstone Financial Vanished from Internet Searches

On August 5, I wrote about a temporary restraining order in Goldstone Financial Group, LLC v. FinanceScam.com that ordered the removal of posts alleging that Goldstone Financial Group and its CEO Anthony Pellegrino had engaged in deceptive attempts to try to vanish material about them from Internet searches.

I explained that there had indeed been seemingly deceptive attempts to vanish such material about Goldstone and Pellegrino, though they denied that the attempts came from them, or were authorized by them. Now it turns out that someone submitted yet another deindexing request to Google, asking Google to remove various pages about Goldstone and Pellegrino from search results. That request was based on the Complaint that Goldstone and Pellegrino had filed, and it sought the deindexing not just of posts on FinanceScam.com but also from various government sites:

https://adviserinfo.sec.gov/individual/summary/6390276 (the Securities and Exchange Commission page related to Anthony Pellegrino, which includes records of certain government proceedings against him).https://brokercheck.finra.org/individual/summary/5900843 (a Financial Industry Regulatory Authority page containing records of various proceedings related to Michael Pellegrino, who appears to have also been involved in the matter listed in item 5 below).A page uploaded to squarespace.com, URL too long to include here (a Florida state court order related to the settlement of a lawsuit in which Goldstone was one of the defendants).https://www.finance.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/legal/administrative-actions/securities/enforcement-orders/documents/2022/4843-2019-7-05-C-Goldstone-Financial-A-Pellegrino-AO.pdf (an Idaho Department of Finance order in an investigation of Anthony Pellegrino and Financial).https://www.sec.gov/files/litigation/admin/2022/33-11045.pdf (a Securities and Exchange Commission order instituting proceedings against Goldstone, Anthony Pellegrino, and Michael Pellegrino).The request also sought to deindex, among other things, material published by VitalLaw.com, a seemingly reputable research service provided by Wolters Kluwer, and by RegComplianceWatch.com, likewise a seemingly reputable research service.

Now I should stress that this deindexing request does not itself appear to be fraudulent. It appears to attach an accurate version of a filed Complaint. It doesn't claim that the Complaint is a court order. Nor does it make any inaccurate claims of copyright infringement. And, as before, it's not certain who submitted the request.

Still, it seems noteworthy that someone is trying—even if so far unsuccessfully—to get Google to hide from search results government documents that discuss investigations of financial professionals. I e-mailed Goldstone's and Pellegrino's lawyer, as well as Goldstone itself, for a comment but have not heard back; naturally, I'd be glad to post their response on the matter.

The post Attempt to Get Government Documents About Anthony Pellegrino and Goldstone Financial Vanished from Internet Searches appeared first on Reason.com.

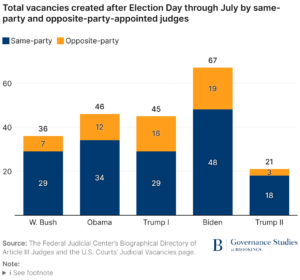

[Jonathan H. Adler] Why Are There So Few Judicial Vacancies for President Trump to Fill?

[There are fewer early-term vacancies than one might have expected.]

The first Trump Administration substantially reshaped the federal courts. Will the second Trump Administration be equally effective or influential on the composition of the judiciary? The jury is still out. Even setting aside the Supreme Court--where President Trump made three appointments in a single term--it is looking like there will be significantly fewer opportunities to influence the balance and composition of the federal courts.

At present, there are more Republican than Democratic nominees on the federal circuit courts of appeal, but there are Republican majorities on only six of thirteen circuits. There are also more Democratic than Republican appointees on district courts, as one would expect given that a Democratic president was making judicial appointments the past four years.

How much influence President Trump will have on the composition of the federal courts will largely depend on the extent to which eligible judges elect to take senior status or retire, thereby creating vacancies for Trump to fill. As I noted in May and July, it appears that some number of judges are more reluctant to take this step than one might have expected.

Russell Wheeler at the Brookings Institution notes that, to date, there are fewer vacancies for Trump to fill than one would usually expect during the early part of a Presidential term. Specifically, Wheeler suggests there have been fewer strategic retirements by Republican appointed judges than one might expect.

Note, however, that any reluctance by Republican appointees to step down or take senior status does not directly affect the extent to which President Trump will influence the balance of the federal courts during his second term. Shifting the balance of the courts generally, and specific circuit courts in particular, will depend upon whether Trump has the opportunity to fill seats currently held by Democratic appointees. (The creation of new court seats, as has been recommended by the Judicial Conference, could also have an impact, particularly on district courts, but this appears unlikely before 2028.)

Wheeler echoes the speculation that some Republican judges may be reluctant to create vacancies because they do not want to be replaced by a Trump appointee, whether because of their concerns about Trump himself, his attitude about the courts, or the sort of nomination he would make. Comments by administration officials and proxies suggesting that Trump is likely to emphasize different criteria in his second term than he did during his first may feed into this, though (with the exception of the Emil Bove nomination, which provoked substantial controversy), Trump's judicial picks so far this term have been quite strong and quite consistent with the pattern we saw during the first term.

There is another factor that may affect Trump's ability to influence the composition of the courts that is rarely discussed: the length of judicial service is increasing. Insofar as longevity is increasing, it should not surprise us that more judges are deciding to serve longer than they might have in the past. In addition, insofar as recent administrations, and the Trump Administration in particular, have increasingly tapped younger judicial nominees, we would expect them to serve longer as well.

In my view, strategic behavior by judges may help explain the relative lack of judicial vacancies for Trump to fill--and I have heard this concern expressed by some judges--but other factors likely play a role as well.

The post Why Are There So Few Judicial Vacancies for President Trump to Fill? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Apparent Massive Quotation/Citation Errors in Netchoice Expert's Report …

[supporting Netchoice's challenge to the Louisiana social media age verification law. Netchoice is a trade association representing many tech companies, including Amazon, eBay, Google, Meta, Netflix, PayPal, and X.]

From the Louisiana Attorney General's memorandum in a motion to exclude an expert report, filed Friday in Netchoice v. Murrill (links added) (and see also the declaration from the AG's expert analyzing the report, as well as the coverage from Friday on Bloomberg [Jacqueline Thomsen]):

NetChoice submitted Dr. Bean's expert report to Defendants, along with the original sources on which he allegedly relied. While the original sources NetChoice produced exist, the substance of Dr. Bean's report is fake. None of the 17 articles in Dr. Bean's reference list exists, and his report never cites the actual sources NetChoice provided to Defendants. More, none of the 12 quotations that Dr. Bean's report attributes to various authors and articles exists (even in the original sources provided to Defendants).

A cursory comparison between Dr. Bean's report and the disclosed original sources would have alerted NetChoice that something is amiss. In fact, just reading Dr. Bean's report would have done so. His reference list makes no sense, (a) citing website links that are dead or lead to entirely unrelated sources and (b) citing volume and page numbers in publications that are easily confirmed to be wrong. And his report itself is strangely formatted, not least because, well, it looks and reads like a print-out from artificial intelligence (AI).

Dr. Bean's report bears all the telltale signs of AI hallucinations: completely fabricated sources and quotations that appear to be based on a survey of real authors and real sources. See, e.g., Brandon Fierro, Short circuit court: AI hallucinations in legal filings and how to avoid making headlines, Reuters (Aug. 4, 2025 8:27 AM), t.ly/inw31. It is difficult to escape the irony of a NetChoice expert submitting an expert report based on non-existent authorities and quotations. Yet here lies NetChoice—a loud proponent of "free expression" and "AI's Transformative Power"—attempting to rely on such a report and such an expert in this litigation.

The upshot is straightforward—and other courts have been down this road before on materially identical facts. Dr. Bean's reliance (under penalty of perjury) on entirely fake sources and quotations "shatters his credibility" beyond repair. Kohls v. Ellison, No. 24-CV-3754 (LMP/DLM), 2025 WL 66514, at *4 (D. Minn. Jan. 10, 2025).

Accordingly, at a minimum, Dr. Bean's testimony must be excluded. More, NetChoice must bear the consequences of "citing to fake sources," which "imposes many harms, including 'wasting the opposing party's time and money, the Court's time and resources, and reputational harms to the legal system (to name a few).'" Id. at *5 (citation omitted). As the Kohls court ordered, this Court should exclude Dr. Bean's testimony and prohibit NetChoice from submitting any amendment or supplement— and award the State Defendants reasonable fees and costs associated with uncovering this egregious problem and filing this motion….

[Long discussion of the errors in the report omitted. -EV]

If the detail here seems exhaustive, it is because the scale of fabrication demands it: Every quotation and citation in Dr. Bean's report is fabricated. Far from obscure errors, these would have been uncovered by even a cursory review of Dr. Bean's report by NetChoice or its counsel. Yet no one did. Given this mountain of fabrication, Dr. Bean never could be deemed competent to offer reliable or credible expert testimony to this Court consistent with Rule 702. Accordingly, the Court should conclude that Dr. Bean's testimony is irreparably unreliable….

I asked Netchoice and their counsel for a statement, and a Netchoice representative responded:

Our counsel confirmed that Dr. Bean's final declaration discussed only source publications that were explicitly provided to the Attorney General. When our team submitted Dr. Bean's declaration, all of the source publications from which each and every assertion in the body of the report were also provided to the AG. To be clear: None of the source publications discussed in the body of the report or produced to the AG were hallucinated by AI. All publications were provided to the AG at the same time as the report. [See all the source publications here]

However, after providing the presumptively final version, our counsel requested that Dr. Bean make a minor change to his declaration to add a paragraph to disclose his hourly compensation. Dr. Bean then accidentally sent us a different version that misattributed Dr. Bean's summaries of publications as quotations from the authors of those publications. Our team should have caught that before sending it to the AG.

Of the quotations that the AG said were "fabricated," these should have been described as Dr. Bean's statements about actual publications and findings by others. In the version submitted to the AG, these statements were incorrectly shown as quotes from the authors of those publications.

The references section of Dr. Bean's declaration contained errors on authors, article titles and publications that neither we, nor our outside counsel, discovered in our review of the report. Nonetheless, all of the true and correct publications supporting Dr. Bean's conclusions were provided to the AG at the same time as the report. [See all the source publications again here]

We're disappointed in this situation but remain confident in our case challenging the constitutionality of Louisiana SB 162. This was the first time we used Dr. Bean as an expert in one of our cases. We wish we would have had the opportunity to resolve this issue directly with the AG's office, and had we known of Dr. Bean's misattributions, we would have withdrawn his declaration because it did not meet our standards.

For your information, we are going to drop Dr. Bean as an expert and will withdraw his declaration, in our response to the state's motion to exclude his declaration.

Like courts around the country, this court requires that both sides engage directly to resolve questions about discovery, in good faith, amicably, and without unnecessarily burdening the court, [see Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 37a]. We've met several times with the AG in this case, regarding various aspects of discovery–including just last Wednesday about Dr. Bean's expert deposition–but at no time did the AG's office raise their concerns about Dr. Bean's declaration so that we could resolve their concerns. Instead, the AG filed a motion with the Court and placed a sensational media story, despite none of the source publications discussed in the body of the report or produced to the AG being hallucinated by AI.

Again, if the AG had followed proper procedure as laid out in the federal rules of civil procedure and made us aware of Dr. Bean's misattributions, we would have withdrawn his declaration.

NetChoice remains confident that Louisiana's law is unconstitutional and will ultimately be struck down. Indeed, when assessing similar law, Justice Kavanaugh said that NetChoice is likely to succeed in demonstrating that age-verification for social media is "likely unconstitutional."

We look forward to challenging SB 162 in court.

I followed up with this:

Thanks for the very prompt response, and I entirely appreciate that the source publications produced to the AG were real. I also appreciate the possibility of version control errors.

Still, I wanted to ask some follow-up questions that I expect our readers would have—and that the judge will likely have as well.

Can you pass along, please, a copy of the presumptively final version of the report that you folks were prepared to file before the request to add the paragraph about compensation?Do you have a sense of why any version would misattribute the expert's own summaries of the publications as quotations from the authors of those publication? I've never heard of that happening before; I've heard of people saying (in controversies about alleged plagiarism) that others' text was apparently copied into a file and quotation marks were inadvertently omitted, but I've never heard of quotation marks being inadvertently added by a person to represent his or her own work as someone else's. Is the reason for those quotation marks that those quotes were generated in part by [generative] AI, which is indeed known for sometimes erroneously putting its own output into quotation marks?Do you have a sense of why the author, article title, and publication names cited in the declaration were so comprehensively erroneous? The obvious explanation is that the report was prepared in part using AI, and the citations were hallucinated—is that the correct explanation?

Netchoice's representative responded:

On the first [question], unfortunately, as this case is still in active litigation, we cannot share the prior version of the report.

On the second and third, we do not have any additional insight as to why or how these errors arose.

Regardless of how these errors came about, when they were brought to our attention, we determined the report was not up to our standards and have severed our relationship with Dr. Bean as a result.

The post Apparent Massive Quotation/Citation Errors in Netchoice Expert's Report … appeared first on Reason.com.

August 17, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Eric Claeys Guest-Blogging About His New Book, "Natural Property Rights"

I'm delighted to report that Prof. Eric Claeys (George Mason, Antonin Scalia School of Law) will be guest-blogging this week about his new book, Natural Property Rights. Here's the publisher's summary:

Natural Property Rights presents a novel theory of property based on individual, pre-political rights. The book argues that a just system of property protects people's rights to use resources and also orders those rights consistent with natural law and the public welfare.

Drawing on influential property theorists such as Grotius, Locke, Blackstone, and early American statesmen and judges, as well as recent work in in normative and analytical philosophy, the book shows how natural rights guide political and legal reasoning about property law. It examines how natural rights justify the most familiar institutions in property, including public property, ownership, the system of estates and future interests, leases, servitudes, mortgages, police regulation, and eminent domain. Thought-provoking and comprehensive, the book challenges leading contemporary justifications for property and shows how property both secures individual freedom and serves the common good.

The post Eric Claeys Guest-Blogging About His New Book, "Natural Property Rights" appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers