Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 246

October 14, 2024

[Josh Blackman] The WSJ Story About Future Trump Judicial Nominees

The Wall Street Journal published an article titled, "Trump Loyalists Push for a Combative Slate of New Judges." The first sentence repeats the theme of loyalty: "A rising faction within the conservative legal movement is laying the groundwork for Donald Trump to appoint judges who prioritize loyalty to him and aggressively advocate for dismantling the federal government should he win a second term." The implied connection is clear: Trump loyalists in executive branch seek to install Trump loyalists in the judiciary branch. Nonsense.

There is not a single word in the story to suggest that Trump appointees would be "loyal" to Trump. These judges have a constitutional vision that far surpasses whatever ephemeral issues matter to Trump. Judicial appointments can last up to forty years. Trump will be in office for, at most, four years. And if Trump prevails, he will not have to stand for any more elections, thus no more Trump-election-related litigation. More likely than not, anti-Trump litigation will be brought in blue circuits, where Trump-appointees are a discrete and insular minority. Does anyone think that a handful of Trump appointees on the Ninth Circuit will make a difference? Judges Katsas, Rao, and Walker will be flying solo on the D.C. Circuit for some time. And the Fourth Circuit is lost for a generation. I truly do not understand the thrust of this "loyalist" meme. It is not accurate, and even if accurate, will have no practical effect.

Instead, the true thrust of the piece comes in a quote from Mike Davis:

Future Trump judicial nominees must be "even more bold and more conservative and more fearless," than those appointed in the first administration, said Republican legal activist Mike Davis, one of the conservative lawyers pushing for a harder line in a potential second Trump administration.

As I've written "judicial courage," should be an important metric for any future judges. I think any plausible judicial nominee will profess fidelity to textualism and originalism. Or at least they will pretend to. That is a given. The better question is what a judge will do with that jurisprudence. To use an analogy, what quantum of originalist evidence is sufficient to upset the status quo. This is not merely a question about stare decisis. I've written at some length how Justice Barrett has imposed extremely onerous burdens on litigants seeking to change things. And the Barrett mode is common enough on the lower courts. Of course lower court judges cannot reverse Supreme Court precedent. And individual panels cannot reverse circuit precedent. But between those lines, there is some space for lower-court originalism.

The article goes on to say that conservatives were "surprised" by Justice Gorsuch's Bostock majority and Justice Kavanaugh's concurrences.

Some were shocked in 2020, for instance, when Gorsuch, the most libertarian of the Trump three, joined with liberal justices and Chief Justice John Roberts to extend federal civil-rights protections to LGBT employees. Others have expressed exasperation at Kavanaugh's practice of filing concurring opinions that credit the concerns of liberal dissenters even when he votes with the conservative majority—something he did in the 2022 decision eliminating women's federal right to abortion before fetal viability.

No one should have been surprised by anything the Trump appointees have done. They are behaving now exactly as they behaved below. To the extent that conservatives are frustrated with these Justices, they should reconsider the criteria for appointment.

The rest of the article tries to sketch some divide between the "old guard" and the "new guard" within the Federalist Society.

The movement's old guard, including lawyers who helped found the Federalist Society in the 1980s, is pushing back, fearful of discrediting the conservative principles they worked for decades to legitimize within a legal profession that leaned left.

Since losing the 2020 election, Trump has broken with Federalist Society leaders who had eagerly boosted his blitz of judicial appointments during his first term but later balked at his efforts to thwart President Biden's victory and didn't openly support him as he faced dozens of criminal charges.

Trump has gravitated to more-combative lawyers outside the conservative legal establishment who have said they want to hobble regulatory agencies and concentrate power in the White House. The shift has sidelined the old guard in favor of groups like America First Legal, run by former Trump adviser Stephen Miller, who isn't a lawyer but said he set up the group to fight what it called "an unholy alliance of corrupt special interests, big tech titans, the fake news media and liberal Washington politicians." . . . .

Longtime Federalist Society members said the group was designed not to advocate for specific positions but to promote conservative and libertarian thought more broadly—and provide a career network for right-leaning lawyers interested in government and the judiciary.

"I'm one of the traditionalists who believe the strength of the Federalist Society is that it doesn't take positions, it allows its members to take positions," said former Solicitor General Ted Olson, who took part in the 1982 conference at Yale Law School where the group was founded. . . .

Sarah Isgur, who was a spokeswoman for the Trump Justice Department and considers herself more of a traditional conservative, said that while the Federalist Society historically sought to associate its movement with the most prestigious law schools and professional accomplishments, the upstarts have other criteria.

The direction of FedSoc seems separate from the question about potential Trump nominees. But I do think that FedSoc is standing at something of a turning point, given the pending search for President.

The post The WSJ Story About Future Trump Judicial Nominees appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Monday Open Thread

The post Monday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Journal of Free Speech Law: "The Future of Speech Online: International Cooperation for a Free & Open Internet," by Nick Clegg

The article is here; the introductory paragraphs:

The internet is the latest in a long line of communications technologies to have enabled greater freedom of speech. From the printing press to the radio to the television and the cell phone, technological advances have made it possible for more people to express themselves, share news, and spread ideas. At every stage, speech has been further democratized, empowering people who could not previously make themselves heard and challenging the influence of the traditional gatekeepers of public information—including the state, the church, politicians, and the media. These advances have often been met first with excitement and enthusiasm, followed by a public backlash fueled by a mix of legitimate concerns about the impact of technology on society and moral panic stoked by the vested interests whose power has been challenged. In time, these pendulum swings have come to a resting point through a combination of the normalization of the technologies in society, the development of commonly understood norms and standards, and the imposition of guardrails through regulation.

The internet has enabled the most radical democratization of speech yet, making it possible for anyone with an internet connection and a phone or computer to express themselves, connect with people regardless of geographical barriers, organize around shared interests, and share their experiences across the world in an instant. Over the last two decades, social media and instant messaging apps have turbocharged internet-enabled direct communication—and have exploded in popularity. More than one-third of the world's population uses Facebook every day. More than one hundred forty billion messages are sent every day on Meta's messaging apps, including Messenger, WhatsApp, and Instagram.

These technologies have made it possible for grassroots movements to grow rapidly and challenge established authority and orthodoxy, and in doing so, change the world—from the Arab Spring to the Black Lives Matter movement and #MeToo. A decade ago, sociologist Larry Diamond called social media a "liberation technology." Without the ability of ordinary people to share text, images, and video in close-to-real time, and to have it amplified via networks of people connected through social media apps like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, the groundswell of public support for these causes and others would never have been possible. Social media also made it possible for millions of spontaneous grassroots community-based initiatives to start and flourish during the emergency stages of the COVID-19 pandemic to help the vulnerable or celebrate frontline workers, and for millions of small businesses to stay afloat and reach customers during lockdowns.

It would be naive to assume that connection inevitably leads to progress or harmony. The free and open internet is not a panacea. With hindsight, the techno-utopianism of the Arab Spring phase of social media was never going to last. But the pendulum has now swung far the other way, as it has done in the aftermath of previous technological advances, to a phase of techno-pessimism, with many critics decrying social media as the source of many of today's societal ills. This backlash has led us to a pivotal moment for the internet. Politicians around the world are now responding to the clamor with a new wave of laws and regulations that will shape the internet for generations to come.

The radical liberalization of speech enabled by the internet brings its own set of issues and dilemmas: from what to do about the spread of misinformation, hate speech, and other forms of "bad" speech, to a range of novel issues around privacy, security, well-being, and more. These challenges are worthy of lengthy analysis and discussion in their own right—and they are the focus of other essays in this volume.

It is right that policymakers the world over are grappling with the many challenges the internet presents and beginning to establish a new generation of guardrails intended to mitigate the potential harms. But if we accept as our starting point that, for all the downsides, empowering people to express themselves directly is on the whole a positive thing for societies, and that this has been enabled by the open, borderless, and largely free-to-access internet, then we must not take it for granted.

In its early days, many thought that the internet's distributed architecture and multi-stakeholder governance model would be enough to keep it open and free. It was thought that the web was by design a technology that evades control by any single state or organization—an idea perhaps best captured in poet and political activist John Perry Barlow's end-of-the-millennium manifesto, "A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace." As he rather grandly put it: "Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather." Alas, this idealism has proved to be misplaced. Events in recent years have demonstrated that the internet's design is not enough to guarantee protection from government control.

The clash between borderless open communication and authoritarian top-down control is one of the greatest tensions in the modern internet age. Authoritarian and semi-authoritarian regimes have demonstrated over and over that when they want to quash dissent, one of the tools they use is the internet. They often try to do two things: 1) censor what their citizens can say, and 2) cut their citizens off from the rest of the global internet. And, as we have seen firsthand at Meta, to do these things they target the use of social media and messaging apps by their citizens….

The post Journal of Free Speech Law: "The Future of Speech Online: International Cooperation for a Free & Open Internet," by Nick Clegg appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] FCC as Truth Police / Racism Police / Sowing Discord Police

Thursday, FCC Chair Jessica Rozenworcel denounced Trump's calls for the FCC to strip CBS of its license (and to investigate ABC) for alleged bias against him. Seven years ago, then-Chair Ajit Pai likewise rejected then-President Trump's calls for the FCC to strip NBC of its license for supposed "fake news."

The FCC had also been asked to deny renewal to a FOX Philadelphia affiliate on the grounds that it "aired 'false information about election fraud' about the 2020 presidential election and arguing it sowed discord and contributed 'to harmful and dangerous acts on January 6' at the U.S. Capitol." That matter is pending, though a month ago FCC Commissioner Nathan Simington urged the FCC to close it.

Back in 2014, the FCC rejected the claim that broadcasters that referred to the Washington Redskins (the team name at the time) should lose their licenses. Marilyn Mosby, then the Baltimore State's Attorney (since convicted of perjury and mortgage fraud), asked the FCC to investigate a local TV station on the theory that its coverage of her was "blatantly slanted, dishonest, misleading, racist, and extremely dangerous"; Commissioner Brendan Carr put out a statement condemning the complaint, and I haven't seen any indication that the FCC has taken any action on it.

The law in this area is, regrettably, complicated. The Supreme Court has broadly protected the right of newspapers, magazines, book authors, filmmakers, cable companies, Internet companies, and others to speak, without the fear that a government agency will strip them of the right to speak based on the content of their speech. But the rule for broadcast television and radio has been different. Since the 1920s, the government has required a license to broadcast; part of the rationale was to prevent stations from interfering with each other using the same frequency, but once the licenses were given, the government has used that as a means to impose "public interest" requirements on licensees. Here is an excerpt on this from Justice White's opinion in Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC (1969):

Where there are substantially more individuals who want to broadcast than there are frequencies to allocate, it is idle to posit an unabridgeable First Amendment right to broadcast comparable to the right of every individual to speak, write, or publish. If 100 persons want broadcast licenses but there are only 10 frequencies to allocate, all of them may have the same "right" to a license; but if there is to be any effective communication by radio, only a few can be licensed and the rest must be barred from the airwaves. It would be strange if the First Amendment, aimed at protecting and furthering communications, prevented the Government from making radio communication possible by requiring licenses to broadcast and by limiting the number of licenses so as not to overcrowd the spectrum.

This has been the consistent view of the Court. Congress unquestionably has the power to grant and deny licenses and to eliminate existing stations. No one has a First Amendment right to a license or to monopolize a radio frequency; to deny a station license because "the public interest" requires it "is not a denial of free speech."

By the same token, as far as the First Amendment is concerned those who are licensed stand no better than those to whom licenses are refused. A license permits broadcasting, but the licensee has no constitutional right to be the one who holds the license or to monopolize a radio frequency to the exclusion of his fellow citizens. There is nothing in the First Amendment which prevents the Government from requiring a licensee to share his frequency with others and to conduct himself as a proxy or fiduciary with obligations to present those views and voices which are representative of his community and which would otherwise, by necessity, be barred from the airwaves.

Justice White used this argument to uphold (1) the Fairness Doctrine, which generally required "that discussion of public issues be presented on broadcast stations, and that each side of those issues must be given fair coverage," and (2) the Personal Attack Rule, which more specifically required that, "When, during the presentation of views on a controversial issue of public importance, an attack is made upon the honesty, character, integrity or like personal qualities of an identified person or group," the target be given "a reasonable opportunity to respond." The Court has also held, in FCC v. Pacifica Foundation (1978), that because broadcasting reached into the home and was unusually accessible to children, the government could ban the "Seven Dirty Words" on radio and television (though it couldn't do so on the public street). Lower courts have likewise allowed some policing by the FCC of alleged "distortion," see, e.g., Serafyn v. FCC (D.C. Cir. 1998). And the FCC has a specific "broadcast hoaxes rules" barring the publication of knowingly "false information concerning a crime or a catastrophe," if the information foreseeably "cause[s] substantial public harm."

Fortunately, in recent years the FCC has recognized the dangers of policing speech this way, whether in the service of trying to restrict disfavored views (such as alleged racism) or supposed misinformation. The case involving the Washington Redskins is one example; the FCC there recognized that the Court's decision upholding the viewpoint-neutral restrictions on sex- and excretion-related vulgarities in Pacifica couldn't be extended to allegedly bigoted words, which would be punished precisely because of their supposed viewpoints. The FCC commissioners' statements quoted above support this as well, as does the FCC's 2020 decision related to the broadcast hoaxes rule:

[T]he Commission does not—and cannot and will not—act as a self-appointed, free-roving arbiter of truth in journalism. Even assuming for the sake of argument that Free Press's assertions regarding any lack of veracity were true, false speech enjoys some First Amendment protection, and section 326 of the Communications Act, reflecting First Amendment values, prohibits the Commission from interfering with freedom of the press or censoring broadcast communications. Accordingly, the Commission has recognized that "[b]roadcasters—not the FCC or any other government agency—are responsible for selecting the material they air" and that "our role in overseeing program content is very limited."

On the Court, Justices Thomas and Ginsburg had also suggested that it was unsound to offer lesser First Amendment protection to broadcasting; I expect that, if the issue were to come before the Court today, Red Lion and Pacifica would at least be sharply limited and perhaps overruled altogether.

Whether or not some narrow, clearly-defined, and viewpoint-neutral restrictions or access compulsions (such as the Personal Attack Rule) should be upheld for broadcasters, I think that the FCC can't be trusted to police supposed "misinformation" on radio and television any more than some Federal Newspaper Commission could be trusted to police supposed misinformation in newspapers. The same is true, of course, for state governments as well as the federal government. For all the dangers posed by falsehoods about politics, science, and the like—and I think those dangers are quite real—the dangers of the government policing such falsehoods are greater still. To quote Justice Alito's dissent for three Justices in U.S. v. Alvarez (2012) (which was agreed with by the two-Justice concurrence, and as to which the plurality raised no objection),

The point is not that there is no such thing as truth or falsity in these areas or that the truth is always impossible to ascertain, but rather that it is perilous to permit the state to be the arbiter of truth.

The post FCC as Truth Police / Racism Police / Sowing Discord Police appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Submit Your Articles to the Journal of Free Speech Law, Before You Circulate Them to the Law Reviews

Our peer-reviewed Journal of Free Speech Law, which is now nearly four years old, has published 65 articles, including by Robert Post (Yale), Jack Balkin (Yale), Keith Whittington (Yale), Mark Lemley (Stanford), Geoffrey Stone (Chicago), Vince Blasi (Columbia), Jeremy Waldron (NYU), Cynthia Estlund (NYU), Christopher Yoo (Penn), Danielle Citron (Virginia), and many others—both prominent figures in the field and emerging young scholars (including ones who didn't have a tenure-track academic appointment). The articles have been cited so far in eight court cases, over 235 articles, and over 90 briefs. And note that all the articles have only had three years or less to attract these citations.

I expect that many authors are planning to submit articles on free speech to the usual law reviews when the submission cycle restarts in February. But if you submit exclusively to us before that, we will give you an answer within 14 days (our guarantee, which we have so far never broken); and then if you'd like to have it published quickly, we can publish it in within several weeks, if it's sufficiently clean and cite-checked by your research assistant. (If you don't have a research assistant, we can have it cite-checked for you by one of our student staffers, but that takes a bit longer.) This means your article can be published by us, if it's accepted, almost a year (or more) before it would be published by the law journals.

Of course, also please pass this along to friends or colleagues who you think might be interested. Note that the submissions don't compete for a limited number of slots in an issue or volume; we'll publish articles that satisfy our quality standards whenever we get them.

All submissions must be exclusive to us, but, again, you'll have an answer within 14 days, so you'll be able to submit elsewhere if we say no. Please submit an anonymized draft, together with at https://freespeechlaw.scholasticahq.com/. A few guidelines:

Instead of a cover letter, please submit at most one page (and preferably just a paragraph or two) explaining how your article is novel. If there is a particular way of showing that (e.g., it's the first article to discuss how case X and doctrine Y interact), please let us know. Please submit articles single-spaced, in a proportionally spaced font. Please make sure that the Introduction quickly and clearly explains the main claims you are making. Please avoid extended background sections reciting familiar Supreme Court precedents or other well-known matters. We prefer articles that get right down to the novel material (if necessary, quickly explaining the necessary legal principles as they go). Each article should be as short as possible, and as long as necessary. Like everyone else, we like simple, clear, engaging writing. We are open to student-written work, and we evaluate it under the same standards applicable to work written by others.We publish:

Articles that say something we don't already know. Articles with all sorts of approaches: doctrinal, theoretical, historical, empirical, or otherwise. Articles dealing with speech, press, assembly, petition, or expression more broadly. Generally not articles purely focused on the Free Exercise Clause or Establishment Clause, except if they also substantially discuss religious speech. Articles about the First Amendment, state constitutional free speech provisions, federal and state statutes, common-law rules, and regulations protecting or restricting speech, or private organizations' speech regulations. Articles about U.S. law, foreign law, comparative law, or international law. Both big, ambitious work and narrower material. Articles that are useful to the academy, to the bench, or to the bar (or if possible, to all three). Articles arguing for broader speech protection, narrower speech protection, or anything else.The post Submit Your Articles to the Journal of Free Speech Law, Before You Circulate Them to the Law Reviews appeared first on Reason.com.

[Thomas Lee and Jesse Egbert] Corpus Linguistics, LLM AIs, And the Assessment of Ordinary Meaning

More and more, judges are seeing the assessment of ordinary meaning as an empirical matter—an inquiry into the way legal words or phrases are commonly used by the public. This inquiry is viewed as furthering some core tenets of textualism. It views the assessment of the ordinary meaning of words as transparent, determinate, and constraining—much more so than a free-wheeling inquiry into the intent of the legislative body.

For many years and for many interpretive questions, dictionaries were viewed as the gold standard. To resolve an interpretive question, all the judge had to do was declare that the ordinary meaning of the text controls, note that dictionaries are reliable evidence of such meaning, and cite a dictionary definition as the decisive basis for decision.

Over time, both scholars and judges have come to question the viability of that approach—especially in cases where competing dictionary definitions provide support for both sides of a case. In that event, a judge's intuitive preference for one definition over another isn't transparent. And it isn't any more constraining than a subjective assessment of legislative intent.

That does not mean that the ordinary meaning inquiry is lost. It just means that we need more sophisticated tools to answer it.

Increasingly, scholars and judges are acknowledging that the empirical dimensions of the ordinary meaning inquiry call for data. And they are turning to tools aimed at producing transparent, replicable evidence of how the language of law is commonly or typically used by the public. A key set of those tools come from the field of corpus linguistics—a field that studies language use by examining large databases (corpora) of naturally occurring language.

When properly applied, corpus linguistic analysis delivers on the promises of empirical textualism. A judge who is interested in assessing how a term is commonly used by the public can perform a replicable search of that term in a corpus designed to represent language use by the relevant speech community. Such a search will yield a dataset with replicable, transparent answers to the empirical dimensions of the ordinary meaning inquiry—as to whether and how often a term is used in the senses proposed by each party. And that data will provide the judge with a determinate basis for deciding the question presented.

Take the real-world case of Snell v. United Specialty Insurance, which raised the question whether the installation of an in-ground trampoline falls within the ordinary meaning of "landscaping" under an insurance policy. Dictionaries highlight the potential plausibility of both parties' positions—indicating that "landscaping" can be understood to mean either (a) botanical improvements to an outdoor space for aesthetic purposes or (b) any improvement to an outdoor space for aesthetic or functional purposes.

A researcher interested in assessing which of these definitions reflects the common or typical use of "landscaping" could perform a search for these terms in a corpus of naturally occurring language. Such a search would yield actual data—on how often "landscaping" is used in either of the above ways (or how often it is used to encompass a non-botanical improvement like an in-ground trampoline). And the resulting data would inform the ordinary meaning inquiry in ways that a dictionary could not.

This sort of corpus inquiry has been proposed and developed in legal scholarship. And it has taken hold in courts throughout the nation—with judges in the United States Supreme Court and in various federal and state courts citing corpus methods in their analysis of ordinary meaning (see fn 22 in our article).

In recent months, critics of corpus linguistics have swooped in with something purportedly better: AI-driven large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT. The proposal began with two recent law review articles. And it caught fire—and a load of media attention—with a concurring opinion by Eleventh Circuit Judge Kevin Newsom in the Snell case.

Judge Newsom began by noting that dictionaries did little more than highlight a basis for disagreement (on whether "landscaping" is commonly or typically limited to natural, botanical improvements). As a textualist, he said he "didn't want to be that guy"—the judge who picks one definition over another based on his "visceral, gut instinct." So he went looking elsewhere. "[I]n a fit of frustration" or a "lark" he queried ChatGPT, asking (a) "What is the ordinary meaning of 'landscaping'?," and (b) "Is installing an in-ground trampoline 'landscaping'?"

ChatGPT told Newsom that "landscaping" "can include" not just planting trees or shrubs but "installing paths, fences, water features, and other elements to enhance the . . . functionality of the outdoor space" and that "installing an in-ground trampoline can be considered part of landscaping."

Newsom found these responses "[i]nteresting," "sensible," and aligned with his "experience." He channeled points developed in recent scholarship. And he came down in support of the use of AIs as "high-octane language-prediction machines capable of probabilistically mapping . . . how ordinary people use words and phrases in context"—or tools for identifying "datapoints" on the ordinary meaning of the language of law.

Newsom doubled down on this view in a more recent concurrence in United States v. DeLeon—a case raising the question whether a robber has "physically restrained" a victim by holding him at gunpoint under a sentencing enhancement in the sentencing guidelines. Again the question was not easily resolved by resort to dictionaries. And again Newsom turned to LLM AI queries, which he likened to a "survey" asking "umpteen million subjects, 'What is the ordinary meaning of 'physically restrained'?"

The Newsom concurrences are intriguing. Perhaps they are to be applauded for

highlighting the need for empirical tools in the assessment of ordinary meaning. But LLM AIs are not up to the empirical task. They don't produce datapoints or probabilistic maps. At most they give an artificial entity's conclusions on the interpretive question presented—in terms that may align with a judge's intuition but won't provide any data to inform or constrain it.

AI apologists seem to be thinking of chatbot responses as presenting either (1) results of empirical analyses of language use in an LLM corpus (as suggested in Snell) or (2) results of a pseudo-survey of many people (through the texts they authored) (as suggested in DeLeon). In fact they are doing neither. As we show in our article and will develop in subsequent posts, at most AIs are presenting (3) the "views" of a single, artificial super-brain that has learned from many texts.

The apologists need to pick a lane. AI chatbots can't be doing more than one of these three things. And if they are (as we say) just presenting the rationalistic opinion of a single artificial entity, they aren't presenting the kind of empirical data that aligns with the tenets of textualism.

We raise these points (and others) in a recent draft article. And we will develop them further here in posts over the next few days.

The post Corpus Linguistics, LLM AIs, And the Assessment of Ordinary Meaning appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 14, 1911

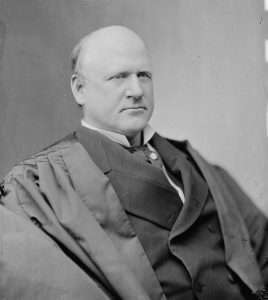

10/14/1911: Justice John Marshall Harlan I dies.

Justice John Marshall Harlan I

Justice John Marshall Harlan IThe post Today in Supreme Court History: October 14, 1911 appeared first on Reason.com.

October 13, 2024

[Ilya Somin] Trump's Plan to Use the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 as a Tool for Mass Deportation

Cartoon depicting congressional debate over the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Cartoon depicting congressional debate over the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Donald Trump recently announced his intention to use the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 as a tool for mass deportation of immigrants. The Alien Enemies Act is a component of the notorious Alien And Sedition Acts. It's the only part of that legislation that remains on the books today. Unlike the more sweeping Alien Friends Act, which gave the president broad power to deport and bar any "aliens as he shall judge dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States," and was therefore rightly denounced as unconstitutional by James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and others, the Alien Enemies Act allows detention and removal only when there "is a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion is perpetrated, attempted, or threatened against the territory of the United States by any foreign nation or government." In that event, the president is given the power to detain or remove "all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of the hostile nation or government, being of the age of fourteen years and upward, who shall be within the United States and not actually naturalized."

Katherine Yon Ebright of the Brennan Center has an excellent explanation of why the Alien Enemies Act cannot legally be used against migrants from countries with which the US is not at war. Here's her summary of her analysis:

As the Supreme Court and past presidents have acknowledged, the Alien Enemies Act is a wartime authority enacted and implemented under the war power. When the Fifth Congress passed the law and the Wilson administration defended it in court during World War I, they did so on the understanding that noncitizens with connections to a foreign belligerent could be "treated as prisoners of war" under the "rules of war under the law of nations." In the Constitution and other late-1700s statutes, the term invasion is used literally, typically to refer to large-scale attacks. The term predatory incursion is also used literally in writings of that period to refer to slightly smaller attacks like the 1781 Raid on Richmond led by American defector Benedict Arnold.

Today, some anti-immigration politicians and groups urge a non-literal reading of invasion and predatory incursion so that the Alien Enemies Act can be invoked in response to unlawful migration and cross-border narcotics trafficking. These politicians and groups view the Alien Enemies Act as a turbocharged deportation authority. But their proposed reading of the law is at odds with centuries of legislative, presidential, and judicial practice, all of which confirm that the Alien Enemies Act is a wartime authority. Invoking it in peacetime to bypass conventional immigration law would be a staggering abuse.

She makes several other good points, as well. If you're interested in this issue, read the whole thing!

I would add that the "invasion" or "predatory incursion" in question must be perpetrated by a "foreign nation or government." That excludes illegal migration or drug smuggling perpetrated by private individuals, which is what we see at the southern border today. One can argue that use of the word "nation" in addition to "government" means the former has a different meaning from the latter. Perhaps so. But "nation" still doesn't include private individuals. Rather, it could apply to state-like entities that are not recognized governments. For instance, the Hamas terrorist organization that brutally attacked Israel on Oct. 7, 2023 is not a recognized government, but did—at least until recently—have state-like control over Gaza. The same could be said for some Founding-era Indian nations (which the US and European states didn't recognize as full-fledged governments) and groups like the Barbary pirates, who were agents of Arab north African states.

Elsewhere, I have explained why Founding-era understandings of "invasion" are limited to large-scale armed attacks, and do not cover things like illegal migration or drug smuggling (for more detail, see my amicus brief in United States v. Abbott).

Despite the strong legal arguments against it, there is a chance Trump could succeed in using the Alien Enemies Act as a tool for detention and deportation. As Ebright notes, courts might rule that the definitions of "invasion" and "predatory incursion" are "political questions" that courts aren't allowed to address. Several previous court decisions have held that the definition of "invasion" in the Constitution is a political question (thereby preventing state governments from invoking broad definitions of invasion under the Invasion Clause of Article IV in order to be able to "engage in war" in war without federal authorization), though many have simultaneously held that an illegal migration does not qualify as "invasion" because an invasion requires a large-scale armed attack (see pp. 20-22 of my amicus brief).

Ebright argues (correctly, I think) that even if the definition of "invasion" is usually a political question, the use of the Alien Enemies Act as a tool for mass detention and deportation of migrants from countries with which the US is not at war should fall within the exception for "an obvious mistake" or "manifestly unauthorized exercise of power" (Baker v. Carr (1962)). I would add that the entire political question doctrine is an incoherent mess, and courts should not extend it further.

Nonetheless, there is a danger they could apply it here, and thereby let Trump get away with a grave abuse of power that could potentially harm many thousands of people. Mass deportations of the kind envisioned by Trump would create disruption, increase prices and cause shortages. They also destroys more American jobs than they creates, because many U.S. citizens work in industries that depend on goods produced by undocumented workers. In addition, large-scale detention and deportation routinely sweeps in large numbers of US citizens, detained by mistake because of poor-to-nonexistent due process protections.

It's also worth noting that the Alien Enemies Act applies to any migrants from the relevant countries who have not been "naturalized," which includes legal migrants even permanent resident green card holders. If Trump is able to use it at all, it could be deployed against legal immigrants no less than illegal ones. And he and his allies have repeatedly made clear they want to slash legal migration no less than the illegal kind.

If Trump returns to power, it is possible this particular plan will be stopped by the courts. But that is far from certain. Ebright also recommends Congress simply repeal the Alien Enemies Act (there are plenty of other tools to deal with actual threats to national security); I agree, but it's unlikely to happen anytime soon. Thus, the only surefire way to block this dangerous abuse of power is to defeat Trump in the election.

The post Trump's Plan to Use the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 as a Tool for Mass Deportation appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Thomas R. Lee & Jesse Egbert Guest-Blogging About AI and Corpus Linguistics

I'm delighted to report that Prof. Thomas R. Lee (BYU Law, and former Justice on the Utah Supreme Court) and Prof. Jesse Egbert (Northern Arizona University Applied Linguistics) will be guest-blogging this coming week on their new draft article, Artificial Meaning? The article is about artificial intelligence and corpus linguistics; Prof. Lee has been a pioneer in applying corpus linguistics to law. Here is the abstract:

The textualist turn is increasingly an empirical one—an inquiry into ordinary meaning in the sense of what is commonly or typically ascribed to a given word or phrase. Such an inquiry is inherently empirical. And empirical questions call for replicable evidence produced by transparent methods-not bare human intuition or arbitrary preference for one dictionary definition over another.

Both scholars and judges have begun to make this turn. They have started to adopt the tools used in the field of corpus linguistics—a field that studies language usage by examining large databases (corpora) of naturally occurring language.

This turn is now being challenged by a proposal to use a simpler, now-familiar large language model (LLM)—AI-driven LLMs like ChatGPT. The proposal began with two recent law review articles. And it caught fire—and a load of media attention—with a concurring opinion by Eleventh Circuit Judge Kevin Newsom in a case called Snell v. United Specialty Insurance Co. The Snell concurrence proposed to use ChatGPT and other LLM AIs to generate empirical evidence of relevance to the question whether the installation of in-ground trampolines falls under the ordinary meaning of "landscaping" as used in an insurance policy. It developed a case for relying on such evidence—and for rejecting the methodology of corpus linguistics—based in part on recent legal scholarship. And it presented a series of AI queries and responses that it presented as "datapoints" to be considered "alongside" dictionaries and other evidence of ordinary meaning.

The proposal is alluring. And in some ways it seems inevitable that AI tools will be part of the future of an empirical analysis of ordinary meaning. But existing AI tools are not up to the task. They are engaged in a form of artificial rationalism—not empiricism. And they are in no position to produce reliable datapoints on questions like the one in Snell.

We respond to the counter-position developed in Snell and the articles it relies on. We show how AIs fall short and corpus tools deliver on core components of the empirical inquiry. We present a transparent, replicable means of developing data of relevance to the Snell issue. And we explore the elements of a future in which the strengths of AI-driven LLMs could be deployed in a corpus analysis, and the strengths of the corpus inquiry could be implemented in an inquiry involving AI tools.

The post Thomas R. Lee & Jesse Egbert Guest-Blogging About AI and Corpus Linguistics appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Journal of Free Speech Law: "Hostile State Disinformation in the Internet Age," by Richard A. Clarke

The article is here; the Introduction:

State-sponsored disinformation (SSD) aimed at other nations' populations is a tactic that has been used for millennia. But SSD powered by internet social media is a far more powerful tool than the U.S. government had, until recently, assumed. Such disinformation can erode trust in government, set societal groups—sometimes violently—against each other, prevent national unity, amplify deep political and social divisions, and lead people to take disruptive action in the real world.

In part because of a realization of the power of SSD, legislators, government officials, corporate officials, media figures, and academics have begun debating what measures might be appropriate to reduce the destructive effects of internet disinformation. Most of the proposed solutions have technical or practical difficulties, but more important, they may erode the First Amendment's guarantee of free speech and expression. Foreign powers, however, do not have First Amendment rights. Therefore, in keeping with the Constitution, the U.S. government can act to counter SSD if it can establish clearly that the information is being disseminated by a state actor. If the government can act constitutionally against SSD, can it do so effectively? Or are new legal authorities required?

The federal government already has numerous legal tools to restrict activity in the United States by hostile nations. Some of those tools have recently been used to address hostile powers' malign "influence operations," including internet-powered disinformation. Nonetheless, SSD from several nations continues. Russia in particular runs a sophisticated campaign aimed at America's fissures that has the potential to greatly amplify divisions in this country, negatively affect public policy, and perhaps stimulate violence.

Russia has created or amplified disinformation targeting U.S. audiences on such issues as the character of U.S. presidential candidates, the efficacy of vaccines,

Martin Luther King Jr., the legitimacy of international peace accords, and many other topics that vary from believable to the outlandish. While the topics and the social media messages may seem absurd to many Americans, they do gain traction with some—perhaps enough to make a difference. There is every reason to believe that Russian SSD had a significant influence on, for example, the United Kingdom's referendum on Brexit and the 2016 U.S. presidential election. But acting to block such SSD does risk spilling over into actions limiting citizens' constitutional rights.The effectiveness of internet-powered, hostile foreign government disinformation, used as part of "influence operations" or "hybrid war," stems in part from the facts that the foreign role is usually well hidden, the damage done by foreign operations may be slow and subtle, and the visible actors are usually Americans who believe they are fully self-motivated. Historically, allegations of "foreign ties" have been used to justify suppression of Americans dissenting from wars and other government international activities. Thus, government sanctions against SSD, such as regulation of the content of social media, should be carefully monitored for abuse and should be directed at the state sponsor, not the witting or unwitting citizen.

Government regulation of social media is problematic due to the difficulty of establishing the criteria for banning expression and because interpretation is inevitably required during implementation. The government could use its resources to publicly identify the foreign origins and actors behind malicious SSD. It could share that data with social media organizations and request they block or label it. A voluntary organization sponsored by social media platforms could speedily review such government requests and make recommendations. Giving the government the regulatory capability to block social media postings—other than those clearly promoting criminal activity such as child pornography, illegal drug trafficking, or human smuggling—could lead to future abuses by politically motivated regulators.

The post Journal of Free Speech Law: "Hostile State Disinformation in the Internet Age," by Richard A. Clarke appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers