Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 243

October 18, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Court Order Requiring Removal of Reddit Criticism of Scientist/Consultant Vacated

From the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, which represented defendant Amy Gulley (click on the link above for a version with many more links):

In August 2023, a British court convicted nurse Lucy Letby of murdering seven children and attempting to murder six more. The trial garnered international media attention. When Sarrita Adams — a British expat living in California — questioned the scientific evidence behind the conviction. Claiming to hold a Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge, Adams set up a website questioning the evidence, sought to submit a friend-of-the-court brief to the British court, and began fundraising to "aid in the upcoming appeal for Lucy Letby" — even starting a for-profit company, "Science on Trial, Inc."

British media outlets and internet users questioned the credibility of Adams's claimed credentials and expertise. Some pointed out a California appellate court opinion stating that Adams had not completed her Ph.D. as of November 2017 and questioned Adams' fundraising efforts. Amy Gulley, a Pennsylvania resident, started a subreddit — r/scienceontrial — critical of Adams and her company, and criticized them on X (formerly Twitter).

In June 2024, Adams sued Gulley in California — a state Gulley had never even visited, three time zones away from her home on the east coast. Adams alleged that Gulley was "harassing" and "stalking" Adams, and "impersonating" Science on Trial, Inc., by using its name on a subreddit. Central to Adams's claims was her allegation that Gulley "lied about [Adams'] educational qualifications . . . from the University of Cambridge[.]"

Adams obtained a restraining order — without a hearing — from the San Francisco court, which ordered Gulley: "Do not make any social media posts about or impersonate [Adams] and the company Science on Trial on any public or social media platform."

An order prohibiting future speech is a prior restraint — the "most serious" type of infringement on First Amendment rights. FIRE and California attorney Matthew Strugar came to Gulley's defense. We filed two motions:

A motion to quash, challenging the California court's jurisdiction over Amy Gulley, a Pennsylvania resident who had never been to California. The Constitution's due process guarantees means that a state court does not have jurisdiction over someone who lacks "minimum contacts" with that state. If criticizing someone online meant that person could sue you where they happen to live, a SLAPP plaintiff could force you to hire lawyers to defend yourself in a far-away court — and that can chill protected speech. An anti-SLAPP motion. A "Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation," or SLAPP, is a lawsuit meant to chill protected expression by using the legal process as a cudgel: Even if the person who filed the lawsuit loses, they accomplish their goal of making you spend time and money defending your rights in court, making it costly to criticize them — and encouraging self-censorship. California is one of 34 states that tries to mitigate these costs by providing an early way to end lawsuits targeting protected speech. Anti-SLAPP motions require a plaintiff to show proof of their claims early in a lawsuit. If they cannot, they have to pay the defendant's attorneys' fees. That is a way to prevent people from using the legal process itself to deter criticism.The "temporary" restraining order was repeatedly extended over the course of 115 days — without a hearing…. On September 30, 2024, the court held a hearing, ultimately granting the motion to quash. The court described the anti-SLAPP motion as "compelling," but declined to rule on its merits because the court determined it did not have jurisdiction. After 115 days, the prior restraint was dissolved.

Prior restraints are among the most pernicious forms of censorship because they halt speech before it occurs. The threats they pose to freedom of speech are exacerbated when they are issued without a hearing — or force you to defend your constitutional rights in a far-away court. In taking cases like this, FIRE makes it harder for people to use the costly legal system as a way to harass their critics.

The substantive filings in the case are available here.

Here, by the way, is an interesting factual allegation from FIRE's Reply Memorandum in Support of Special Motion To Strike:

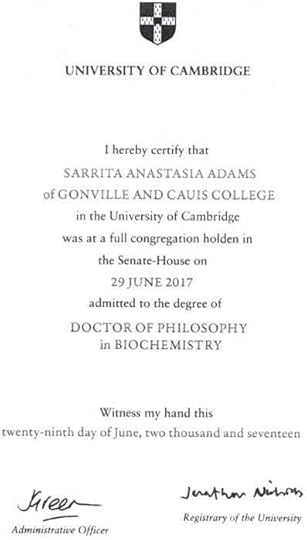

i. The diploma Adams offers from Cambridge University's Gonville

and "Cauis" [sic] College is of dubious authenticity.Adams now testifies she "possess[es] a PhD in Biochemistry from Cambridge University," submitting a diploma that purports to be dated June 29, 2017. Yet the diploma Adams proffers here bears unsettling indicia it is not authentic.

Foremost is the spelling of the college's name—the diploma states it is from Cambridge University's "GONVILLE AND CAUIS COLLEGE." But that flips the letters in the name of "Gonville and Caius College."

The diploma also purports to be signed by the University's Registrary, Jonathan Nicholls. But Nicholls retired from Cambridge University on December 31, 2016—six months before the diploma's date. And photographs of the June 29, 2017, ceremony—posted by the College itself—show diplomas were signed by Nicholls's successor, Acting Registrary Emma Rampton.

ii. Adams is judicially estopped from claiming she was awarded a PhD in June 2017.

Then there is the date on the diploma. In November 2017—five months after the diploma's "29 June 2017" date—Adams testified she had not completed her PhD.

On November 7, 2017, Adams testified in her divorce trial that she did not know when she expected to be able to complete her PhD, as she had to "rewrite the entirety of my thesis." And she told the court point-blank she had not completed her PhD:

THE COURT: Ma'am, you're seeking to complete your Ph.D. and you're finishing up your thesis; correct?

[ADAMS]: Yes.

Judicial estoppel bars Adams from contradicting her prior testimony. The doctrine prevents litigants from playing "fast and loose" with the courts by asserting inconsistent positions. Here, Adams has taken inconsistent positions in judicial proceedings, asserting both that she did not and did have a PhD in November 2017. She was successful in her prior position, as the Alameda court concluded she was entitled to spousal support because her "work prospects" were "limited" until she completed her PhD. Adams cannot now abandon that position even if it were true.

Adams' counsel filed a motion to strike the reply, arguing that the reply introduced new arguments and exhibits and seeking leave to file a sur-reply, but (as I read it) the motion didn't itself respond substantively to Gulley's factual allegations. I emailed Adams' counsel Monday to ask them if they had a statement on the allegations, but haven't heard back from them. Here's the alleged diploma, from an attachment to Adams' opposition to the anti-SLAPP motion:

Gulley is represented by Adam Steinbaugh, Colin McDonell, Gabe Walters, and JT Morris (FIRE) and Matthew Strugar.

The post Court Order Requiring Removal of Reddit Criticism of Scientist/Consultant Vacated appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Court Ordered Ex-Wife to Stop Publicly Disclosing Her Ex-Husband's Alleged Past Misdeed

From an Arizona Court of Appeals decision Tuesday in Wineberg v. Buonsante, written by Judge Lacey Stover Gard and joined by Chief Judge Christopher Staring and Peter Eckerstrom:

In January 2024, Wineberg filed a petition for an order of protection under § 13-3602. He alleged that [his ex-wife] Buonsante had engaged in the following acts:

She has been stalking my community. She has delivered my personal information to people in my community even though being told she has no reason to be around my home. She has been seen on my porch looking through my front window. [S]he has blasted me all over social media. [S]he has harassed my friends and family. This has been going on since June 2023.

The superior court conducted an ex parte hearing, at which Wineberg explained that Buonsante had shown his neighbors a published article containing negative information about him. Wineberg stated that he had not had any communication with Buonsante, but that she had told others that she was "trying to destroy" him. He accused her of seeking to prove that he was a "predator of women."

The superior court determined that Buonsante had "committed the offense of harassment" and granted the order of protection. Based on Wineberg's allegation that Buonsante had disparaged him in videos on a social-media platform, the court included in the protective order a directive that Buonsante "shall not post messages about [Wineberg] on the internet or on social media." It also ordered Buonsante not to possess any firearms for the order's duration and to surrender her existing firearms to law enforcement.

At a later hearing, "Buonsante offered to leave the order in place in exchange for removing the restriction on her right to possess firearms," but "Wineberg maintained that the firearms restriction was necessary because Buonsante posed a credible threat of violence to him." More allegations came out at the hearing:

Wineberg thereafter testified that Buonsante had circulated a disparaging note about him within his retirement community and had sent similar letters to his friends and family members. He produced text messages between his current girlfriend and Buonsante, in which Buonsante indicated that she had visited Wineberg's residence and had seen his couches through the open blinds. Based on these messages, Wineberg deduced that Buonsante had trespassed on his front porch; he explained that his home is elevated above street-level, and Buonsante could not have seen through the windows from the street.

Wineberg further testified that Buonsante had posted videos on social media exposing his purported misdeeds. He also accused her of circulating to his friends, family, and employer a published magazine article discussing alleged acts of wrongdoing in his past. Wineberg admitted, however, that he had never personally seen Buonsante at his home, and that she was unable to contact him because he had blocked her.

Buonsante also testified, and she provided a copy of the article Wineberg had referenced. That article, for which Buonsante and others had been interviewed, was published in InMaricopa magazine and accused Wineberg of having committed stolen valor and other deceitful acts. Buonsante admitted that she had shared the article with others. [The article appears to be this one. -EV]

Buonsante further claimed that she had learned about various troubling aspects of Wineberg's past after she married him, and that he had attempted during the marriage to defraud her in various ways. She said she had reached out to his former wives and romantic partners to gather more information about him. She claimed that she had intended only to warn others of Wineberg's alleged wrongdoing. She denied having trespassed on Wineberg's property; she admitted having driven past his home, but maintained she could see into the windows from the street.

The trial court concluded "that Buonsante's disclosure of negative information about Wineberg to third parties amounted to harassment, an act of domestic violence":

The Court believes based on the testimony [Wineberg] has proven by a preponderance of the evidence that an act of domestic violence … has occurred. The Court believes [Buonsante] has reached out to friends and family member[s] of [Wineberg] to malign … [Wineberg] and to provide information about [Wineberg]. Even if true that would be disturbing to [Wineberg] if he found out that those people were contacted.

The court does not believe it was [Buonsante's] obligation to notify or interfere with [Wineberg's] life, to notify his friends and family of information that they could discover on their own or through public sources. The Court believes that by providing information and links to other videos and information in the public sphere that still was harassment despite the fact that it was viewable publicly. The Court believes [Buonsante] did it merely to harass or disturb [Wineberg] and it was done solely for that purpose.

The trial court therefore "continued the order of protection, amending it to reflect that Buonsante was prohibited from possessing firearms under federal law," but the appellate court reversed.

The appellate court concluded that the speech didn't qualify as "harassment" under Arizona law, which defines the offense thus:

A person commits harassment if the person knowingly and repeatedly commits an act or acts that harass another person or the person knowingly commits any one of the following acts in a manner that harasses:

Contacts or causes a communication with another person by verbal, electronic, mechanical, telegraphic, telephonic or written means. Continues to follow another person in or about a public place after being asked by that person to desist. Surveils or causes a person to surveil another person. Makes a false report to a law enforcement, credit or social service agency against another person. Interferes with the delivery of any public or regulated utility to another person.… "[F]or the purposes of this section, 'harass' means conduct that is directed at a specific person and that would cause a reasonable person to be seriously alarmed, annoyed, humiliated or mentally distressed and the conduct in fact seriously alarms, annoys, humiliates or mentally distresses the person."

The appellate court then reasoned:

"[T]he issuance of an order of protection is a very serious matter" because such an order "carries with it an array of 'collateral legal and reputational consequences' that last beyond the order's expiration." "Therefore, granting an order of protection when the allegations fail to include a statutorily enumerated offense constitutes error by the court."

Here, the superior court did not find that Buonsante had engaged in one of the acts enumerated in [the harassment statute]. The court instead appears to have found that Buonsante "knowingly and repeatedly commit[ted] an act or acts" that harassed Wineberg. The court found that Buonsante had "reached out to [Wineberg's] friends and family member[s]" in order to "malign" him by sharing negative background information. Although the information was already in the public record, the court reasoned that Buonsante should not have informed others of it, and found that she had done so solely for the purpose of harassment.

It is undisputed that Buonsante neither made nor attempted contact with Wineberg; Buonsante therefore maintains that her conduct was not "directed at" him as [the law] requires. She relies on LaFaro v. Cahill (Ariz. App. 2002) …. The plaintiff in LaFaro sought an injunction against harassment in part because he had overheard the defendant call him pejorative names during a conversation with another person. We concluded that the defendant's communication with the third party did "not satisfy the statutory definition of harassment, which requires a harassing act to be 'directed at' the specific person complaining of harassment." We concluded that, although the defendant was talking about the plaintiff, "his comments were 'directed at' [the third party], not [the plaintiff]." …

Although we stopped short in LaFaro of holding that a third-party conversation could never meet the definition of harassment, the facts here largely parallel LaFaro's. Buonsante spoke about Wineberg to third parties and disclosed damaging, but not private, information. Like the plaintiff in LaFaro, Wineberg learned of these statements and found them distressing. But they were "directed at" the third parties, not at Wineberg.

While we do not minimize the impact of Buonsante's actions on Wineberg, we conclude that they do not satisfy [the harassment statute], and that the superior court abused its discretion by determining otherwise….

The court therefore didn't have to reach Buonsante's arguments that the injunction violated the First Amendment and improperly restrained her rights to possess firearms.

Christopher J. Torrenzano (Stillman Smith Gadow) represents Buonsante.

The post Court Ordered Ex-Wife to Stop Publicly Disclosing Her Ex-Husband's Alleged Past Misdeed appeared first on Reason.com.

[Thomas Lee and Jesse Egbert] Could LLM AI Technology Be Leveraged in Corpus Linguistic Analysis?

In our previous four posts we've argued that LLM AIs should not be in the driver's seat of ordinary meaning inquiries. In so stating, we don't deny that AI tools have certain advantages over most current corpus tools: Their front-end interface is more intuitive to use and they can process data faster than human coders.

These are two-edged swords for reasons we discussed yesterday. Without further refinements, the user-friendliness of the interface and speed of the outputs could cut against the utility of LLM AIs in the empirical inquiry into ordinary meaning—by luring the user into thinking that a sensible-sounding answer generated by an accessible, tech-driven tool must be rooted in empiricism.

That said, we see two means of leveraging LLM AIs' advantages while minimizing these risks. One is for linguists to learn from the AI world and leverage the above advantages into the tools of corpus linguistics. Another is for LLM AIs to learn from corpus linguists by building tools that open the door to truly empirical analysis of ordinary language.

Corpus linguistics could take a page from the LLM AI playbook

Corpus linguists could learn from the chatbot interface. The front-end interface of widely used corpora bears a number of limitations—including the non-intuitive nature of the interface, especially for non-linguists. The software requires users to implement search methods and terms that are not always intuitive or natural—drop-down buttons requiring a technical understanding of the operation of the interface and terminology like collocate, KWIC, and association measure. In sharp contrast, AIs like ChatGPT produce a response to a simple query written in conversational English.

Maybe chatbot technology could be incorporated into corpus software—allowing the use of conversational language in place of buttons and dropdown menus. A step in that direction has been taken in at least one widely used corpus software tool that now allows users to prompt ChatGPT (or another LLM) to perform post-processing on corpus results.

This is a step in an interesting direction. But there are at least four barriers to the use of this tool in empirical textualism. The user has no way to know (1) what language to use in order to prompt the chatbot to carry out an analysis of interest, (2) how the chatbot operationalized the constructs mentioned in the query, (3) what methods the chatbot used to process the concordance lines and determine a result, or (4) whether the same query will produce the same results in the future. For these reasons, we believe this approach has too much AI and not enough corpus linguistics. But we are intrigued by the attempt to make corpus linguistics more accessible and user-friendly.

We anticipate a middle ground between existing corpus interfaces, which can be technical and unintuitive, and the highly user-friendly chatbots, which lack transparency and replicability. We imagine a future in which users can import their own corpus and type queries into a chatbot interface. Instead of immediately delivering a result based on black-box operationalizations and methods, the chatbot might reply with clarification questions to confirm exactly what the user wants to search for. Once the user can be sure that the chatbot is performing the desired search query, the chatbot could produce results, along with a detailed description of the exact operational definitions and methods that were used, allowing the user to transparently report the methods and results. As a final step, the chatbot might allow users to save the search settings in a manner allowing researchers to confirm that the same search in the same corpus will generate the same results.

This type of tool would rely on best practices in the field of corpus linguistics while allowing users to interact with the tool in a conversational way to gain access to those analyses without having extensive training in corpus linguistics methods.

LLM AIs could take a page from the corpus linguistics playbook

We can imagine a future where AIs could allow users to search for and receive empirical data on ordinary language usage—not in outsourcing the ultimate question of ordinary meaning to the AI (as in Snell and DeLeon), but in a manner preserving transparency and falsifiability of the corpus inquiry while making the processes faster, larger-scale, and more accessible to non-linguists.

It's plausible that an AI could be trained to apply a coding framework (developed by humans) to the results of a corpus linguistics search—analyzing terms as they appear in the concordance lines to determine whether and to what extent they are used in a certain way. Human intervention would be necessary to check for accuracy. But the process could be streamlined in a manner aimed at increasing speed and accessibility.

To use our landscaping example, researchers could train a chatbot to apply the framework we developed for the study in our draft article for coding each instance of "landscaping" on whether the language was used to refer to botanical elements, non-botanical elements, or both. Again the chatbot's performance on a sample could be evaluated for accuracy against the standard set by human coders who applied the framework to the same sample. The coding framework and prompting language could then be refined with the goal of improving the accuracy of the AI. If the AI never achieves satisfactory levels of accuracy then it would be abandoned and researchers would revert back to human coding.

Drawing the line

Some researchers may be tempted to propose a third step in which they ask the AI to analyze the quantitative results of the coding and report whether the ordinary meaning of "landscaping" includes non-botanical elements. For us, this is a step too far in the direction of Snell-like AI outsourcing—a step toward robo-judging. It would violate our principles of transparency, replicability, and empiricism. And it would outsource crucial decisions about what ordinary meaning is, how much evidence is enough to decide that non-botanical elements are included, and how the data should be used and weighted as part of answering the larger question about meaning. In short, it would outsource judging.

Judges don't need to be told the ordinary meaning of a word or phrase—by a human or a computer. They need empirical evidence of how words and phrases are commonly used so they can discern the ordinary meaning of the law by means that are transparent and empirical.

Corpus tools can do that. LLM AIs, as currently constituted, cannot. But we look forward to a future in which the strengths of both sets of tools can be leveraged in a single inquiry that is simple, accessible, and transparent and that produces falsifiable evidence of ordinary meaning.

The post Could LLM AI Technology Be Leveraged in Corpus Linguistic Analysis? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 18, 1960

10/18/1960: Gomillion v. Lightfoot argued.

The Warren Court (1958-1962)

The Warren Court (1958-1962)The post Today in Supreme Court History: October 18, 1960 appeared first on Reason.com.

October 17, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Thursday Open Thread

The post Thursday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] D.C. Circuit Grants En Banc Review to Consider Reviewability of FEC Enforcement Discretion

On Tuesday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit granted a petition for rehearing en banc in End Citizens United PAC v. Federal Election Commission, to consider whether FEC decisions to decline to take enforcement action are subject to judicial review as "contrary to law." This could produce a significant outcome for the enforcement of federal election law, and perhaps for judicial review of executive branch enforcement discretion more broadly.

In January, a divided panel of the D.C. Circuit concluded that the Federal Election Campaign Act does not create a cause of action to challenge the FEC's exercise of enforcement discretion. Judge Rao wrote for the court, joined by Judge Katsas. Judge Pillard dissented. From Judge Rao's opinion:

FECA allows a court to "declare that the dismissal of [a] complaint … is contrary to law." 52 U.S.C. § 30109(a)(8)(C). Under our precedents, a dismissal is "contrary to law" if "(1) the FEC dismissed the complaint as a result of an impermissible interpretation of [FECA] … or (2) if the FEC's dismissal of the complaint, under a permissible interpretation of the statute, was arbitrary or capricious, or an abuse of discretion." Orloski v. FEC, 795 F.2d 156, 161 (D.C. Cir. 1986). To the extent we review dismissals for arbitrariness, our review is "[h]ighly deferential," "presumes the validity of agency action[,] and permits reversal only if the agency's decision is not supported by substantial evidence, or the agency has made a clear error in judgment." Hagelin v. FEC, 411 F.3d 237, 242 (D.C. Cir. 2005) (cleaned up); accord Campaign Legal Ctr. & Democracy 21 v. FEC, 952 F.3d 352, 357 (D.C. Cir. 2020) (per curiam).

FECA's contrary to law review does not eliminate the Commission's prosecutorial discretion. "[T]he [Administrative Procedure Act] and longstanding … precedents rooted in the Constitution's separation of powers recognize that enforcement decisions are not ordinarily subject to judicial review." New Models, 993 F.3d at 888; see also Chaney, 470 U.S. at 831–32. And "[t]he Supreme Court in Akins recognized that the Commission, like other Executive agencies, retains prosecutorial discretion." Citizens for Resp. & Ethics in Wash. v. FEC, 475 F.3d 337, 340 (D.C. Cir. 2007) (citing FEC v. Akins, 524 U.S. 11, 25 (1998)). It follows that the Commission's "exercise of its prosecutorial discretion cannot be subjected to judicial scrutiny." Comm'n on Hope, 892 F.3d at 439. Furthermore, we recently reiterated that a Commission dismissal is unreviewable if it "turn[s] in whole or in part on enforcement discretion." New Models, 993 F.3d at 894. A dismissal is reviewable "only if the decision rests solely on legal interpretation." Id. at 884; . . .

The Commission's dismissal of the first complaint is an unreviewable exercise of its prosecutorial discretion. As End Citizens United concedes, the controlling commissioners expressly invoked their prosecutorial discretion when dismissing the complaint. They cited Chaney repeatedly, discussed the time and expense an investigation would involve, and mentioned the Commission's "substantial backlog of cases." Statement of Reasons at 2, 10. Prioritizing particular cases and considering limited time and resources are quintessential elements of prosecutorial discretion. When the 10 Commission's dismissal rests even in part on prosecutorial discretion, it is not subject to judicial review. New Models, 993 F.3d at 884, 893–95; see also Comm'n on Hope, 892 F.3d at 439. . . .

Perhaps buoyed by Judge Pillard's dissent (and the ideological makeup of the D.C. Circuit), Camapign Legal Center Action filed a petition for rehearing en banc on behalf of the End Citizens United PAC. The grant of their petition suggests that a majority of the court believes D.C. Circuit caselaw over-insulates FEC non-enforcement decisions from judicial review. If I had to make a prediction, the full court will reverse the panel–but that may not be the end of the story.

The order granting en banc rehearing also expanded the questions before the court. Specifically the order included the following:

In addition to the issues raised in the petition for rehearing en banc, the parties are directed to address in their briefs whether Orloski v. FEC correctly held that an FEC decision can be "contrary to law" under 52 U.S.C. § 30109(a)(8)(C) "if the FEC's dismissal of the complaint . . . was arbitrary or capricious, or an abuse of discretion." 795 F.2d 156, 161 (D.C. Cir. 1986).

I doubt the addition of this question will have much effect on the en banc court's decision, as I suspect a majority of the D.C. Circuit is comfortable with Orloski and the extent to which it facilitates judicial review of some FEC decisions to dismiss complaints. Judge Rao, on the other hand, appears to have some doubts (as indicated by footnote 3 in her opinion, which draws a response in footnote 2 of the dissent). But insofar as Orloski is on the table, could that set up a broader review of judicial review of the FEC (if not federal agencies more broadly) by the Supreme Court? This is a possibility worth watching.

The post D.C. Circuit Grants En Banc Review to Consider Reviewability of FEC Enforcement Discretion appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Justice Sotomayor Asks Texas Governor Abbott To Grant Executive Reprieve To Death Row Prisoner

Tonight the Supreme Court denied a stay of execution in Roberson v. Texas. There were no noted dissents, but Justice Sotomayor issued a ten-page statement respecting the denial of the application. Justice Sotomayor acknowledged that the defendant "presents no cognizable federal claim." Therefore, the Court cannot grant relief. But the final paragraph includes an unusual plea:

Under these circumstances, a stay permitting examination of Roberson's credible claims of actual innocence is imperative; yet this Court is unable to grant it. That means only one avenue for relief remains open: an executive reprieve. In Texas, as in virtually every other State and the federal government, "[t]he Executive has the power to exercise discretion to grant clemency and affect sentences atany stage after an individual is convicted[.]" Vandyke v. State, 538 S. W. 3d 561, 581 (Tex. Ct. Crim. App. 2017).Preventing the execution of one who is actually innocent bymeans of a review "unhampered by legal technicalities" is a core historical purpose of the executive power to grant pardons or reprieves. Christen Jensen, The Pardoning Power in the American States 49 (1922); see also Herrera v. Collins, 506 U. S. 390, 417 (1993) ("History shows that the traditional remedy for claims of innocence based on new evidence, discovered too late in the day to file a new trial motion, has been executive clemency"); Graham v. Texas Bd. of Pardons and Paroles, 913 S. W. 2d 745, 748 (Tex. Ct.Crim. App. 1996) (same). An executive reprieve of thirty days would provide the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles with an opportunity to reconsider the evidence of Roberson's actual innocence. That could prevent a miscarriage of justice from occurring: executing a man who has raised credible evidence of actual innocence.

Yes, you read that right. Justice Sotomayor issued a plea for clemency to Texas Governor Greg Abbott.

Last week I wrote about the potential for clemency in Glossip v. Oklahoma. I noted that one of the justices in the fictional "Case of the Speluncean Explorers" likewise asked the Executive for clemency. I can't recall a Supreme Court justice making a similar request. But Justice Sotomayor may be one of the first.

The post Justice Sotomayor Asks Texas Governor Abbott To Grant Executive Reprieve To Death Row Prisoner appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Court Holds the First Amendment Bars Florida from Threatening Media with Criminal Punishment for Spreading Supposed Health-Related Disinformation

From Chief Judge Mark Walker's opinion today in Floridians Protecting Freedom, Inc. v. Ladapo:

Floridians will vote on six proposed amendments to their state constitution this election cycle, including Amendment 4, titled "Amendment to Limit Government Interference with Abortion." Voting has already begun.

The State of Florida opposes Amendment 4 and has launched a taxpayer-funded campaign against it. Floridians Protecting Freedom, Inc., the Plaintiff in this case, has launched its own campaign in favor of Amendment 4.

Plaintiff does not challenge the State's right to spend millions of taxpayer dollars opposing Amendment 4. The rub, says Plaintiff, is that the State has crossed the line from advocating against Amendment 4 to censoring speech by demanding television stations remove Plaintiff's political advertisements supporting Amendment 4 or face criminal prosecution.

Plaintiff's argument is correct. While Defendant Ladapo refuses to even agree with this simple fact, Plaintiff's political advertisement is political speech—speech at the core of the First Amendment. And just this year, the United States Supreme Court reaffirmed the bedrock principle that the government cannot do indirectly what it cannot do directly by threatening third parties with legal sanctions to censor speech it disfavors. The government cannot excuse its indirect censorship of political speech simply by declaring the disfavored speech is "false." "The very purpose of the First Amendment is to foreclose public authority from assuming a guardianship of the public mind through regulating the press, speech, and religion." "In this field every person must be his own watchman for truth, because the forefathers did not trust any government to separate the true from the false for us." To keep it simple for the State of Florida: it's the First Amendment, stupid….

Plaintiff is a Florida corporation and political committee sponsoring Amendment 4. Plaintiff has actively advocated for the passage of Amendment 4 during this year's general election and against arguments made by those who oppose Amendment 4. To that end, on October 1, 2024, Plaintiff began running an advertisement called "Caroline" on several TV stations across the state, in which a woman recalls her decision to have an abortion in Florida in 2022. She states that she would not be able to have an abortion for the same reason under the current law.

Shortly after the ad began running, John Wilson, then general counsel for the Florida Department of Health, sent letters on the Department's letterhead to Florida TV stations. The letters assert that Plaintiff's political advertisement is false, dangerous, and constitutes a "sanitary nuisance" under Florida law. The letter informed the TV stations that the Department of Health must notify the person found to be committing the nuisance to remove it within 24 hours pursuant to section 386.03(1), Florida Statutes. The letter further warned that the Department could institute legal proceedings if the nuisance were not timely removed, including criminal proceedings pursuant to section 386.03(2)(b), Florida Statutes. Finally, the letter acknowledged that the TV stations have a constitutional right to "broadcast political advertisements," but asserted this does not include "false advertisements which, if believed, would likely have a detrimental effect on the lives and health of pregnant women in Florida." At least one of the TV stations that had been running Plaintiff's advertisement stopped doing so after receiving this letter from the Department of Health.

The court concluded that this violated the First Amendment:

At the hearing, Defendant led with the argument that laws of general applicability are immune from First Amendment challenge. Nonsense. The line of cases Defendant cites to support this dubious argument are readily distinguishable from this case. Defendant's cases addressed a different issue—namely, whether enforcement of a law of general applicability against the press, which incidentally affects the press's ability to gather and report the news, offends the First Amendment. That is not this case. The issue here is whether the State can censor core political speech under the guise that the speech is false and implicates public health concerns. When state action "burdens a fundamental right such as the First Amendment, rational basis yields to more exacting review." With limited exceptions not applicable here, a government restriction on speech is subject to strict scrutiny if it is content based.

{A few "limited categories of speech are traditionally unprotected—obscenity, fighting words, incitement, and the like." "But what counts as unprotected speech starts and ends with tradition—'new categories of unprotected speech may not be added to the list by a legislature that concludes certain speech is too harmful to be tolerated.'"But Defendant has not demonstrated that the political speech at issue falls within any of these categories. It is not commercial speech subject to a more relaxed standard permitting some government regulation, nor is it obscene, nor is it inciting speech that will imminently lead to harm to the government or the commission of a crime.

Defendant argues this is dangerous and misleading speech that could cause pregnant women harm in Florida. But there is no "general exception to the First Amendment for false statements." United States v. Alvarez (2012) (plurality opinion). Falsity alone does not bring speech outside the First Amendment absent some other traditionally recognized, legally cognizable harm. That is because "it is perilous to permit the state to be the arbiter of truth." Alvarez (Alito, J., dissenting).

Defendant seeks to fit a square peg into a round hole by suggesting that Plaintiff's speech is unprotected because it poses an "imminent threat" to public health. But this argument fails too. Speech is unprotected as an "imminent threat" when it incites or produces imminent lawless action, or poses a clear and present danger by bringing about the "substantive evils" that the government has a right to prevent, like obstacles to military efforts, obscenity, acts of violence, and charges to overthrow the government. But there is no suggestion that Plaintiff's ad would bring about the "substantive evils" that the Supreme Court has recognized, nor is there any suggestion that Plaintiff's ad would cause individuals to take any imminent lawless action.}

Government regulation of speech is content based if a law "applies to particular speech because of the topic discussed or the idea or message expressed." A "reliable way" to assess whether a regulation is content based is to ask "whether enforcement authorities must examine the content of the message that is conveyed to know whether the law has been violated." The government engages in "the greatest First Amendment sin"—viewpoint discrimination—when it targets not just a subject matter, but "particular views taken by speakers" on that subject matter.

By threatening criminal proceedings for broadcasting a "political advertisement claiming that current Florida law does not allow physicians to perform abortions necessary to preserve the lives and health of pregnant women," Defendant has engaged in viewpoint discrimination. The letter sent by the Department of Health to broadcasters claimed that Plaintiff's ad violated Florida's sanitary nuisance statute because, "if believed, [it] would likely have a detrimental effect on the lives and health of pregnant women in Florida." Defendant would not be able to conclude that the ad may have a detrimental effect on the lives and health of pregnant women in Florida without reference to the particular view taken by the speaker—namely, that "Florida has now banned abortion even in cases like mine."

Even if the Department of Health's actions here did not amount to viewpoint discrimination, where a government uses the "threat of invoking legal sanctions and other means of coercion … to achieve the suppression" of disfavored speech, it functionally creates "a system of prior administrative restraints" that bears "a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity." Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan (1963). A government official "cannot do indirectly what [he] is barred from doing directly: … coerce a private party to punish or suppress disfavored speech on [his] behalf." NRA v. Vullo (2024). The present case bears all the hallmarks of unconstitutional coercion that the Supreme Court identified in Bantam Books and Vullo.

First, Defendant has enforcement authority that would cause a reasonable person to perceive their official communication as coercive. As cited in the letter, the Department of Health has the authority, if an identified nuisance is not removed within 24 hours, to institute criminal proceedings against all persons failing to comply. Second, the communication can reasonably be understood as a threat. While the "threat need not be explicit," here it was all but: the letter quoted Plaintiff's ad, labeled it as dangerous, suggested that it could threaten the health of women in Florida, identified any act that could threaten or impair the health of an individual as a "sanitary nuisance," and noted the Department's power under Florida law to criminally prosecute all persons who failed to remove a sanitary nuisance within 24 hours. A reasonable person would have no trouble connecting the dots to identify this as a threat. Finally, the reaction from one broadcaster to cease airing the ad after receiving the letter is further evidence of its coercive nature.

{When asked why this case was not governed by Vullo, Defendant's response was that Vullo concerned the state exercising its regulatory authority "in an effort to stop the NRA from engaging in constitutionally protected speech." But "the difference here," he argued, is that "the specific words being expressed" in this case don't fall "within the ambit of the First Amendment." But that is beside the point. In Bantam Books, on which Vullo relied, the state threatened enforcement on the basis that the speech was allegedly obscene—which the Supreme Court acknowledged was "not within the area of constitutionally protected speech or press." Here, as discussed above, Defendant has not even shown that the speech falls within one of the "traditionally unprotected" categories, let alone that such a distinction would remove this case from the ambit of Vullo and Bantam Books.}

To overcome the presumption of unconstitutionality, Defendant must show that his actions were narrowly tailored to serve a compelling government interest. This is a high bar in any case, and so here. Even assuming arguendo that Plaintiff's advertisement is "categorically false," and that countering it is a compelling government interest, Defendant's actions are not narrowly tailored. As the Supreme Court identified in Alvarez, the narrowly tailored solution to alleged falsehoods is counterspeech. That is because the First Amendment embodies a "profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open."

{As discussed above, Defendant's actions are presumptively unconstitutional whether analyzed as viewpoint discrimination or unconstitutional coercion to suppress speech. Viewpoint discrimination may be per se unconstitutional, Honeyfund.com, Inc. v. Governor (11th Cir. 2024), but at a minimum, it is subject to strict scrutiny. The Supreme Court in Bantam Books declared that coercive threats created a system of prior restraint bearing a heavy presumption of unconstitutionality but did not identify a standard of review. Vullo, considered at the motion-to-dismiss stage, simply stated that "a government entity's 'threat of invoking legal sanctions and other means of coercion … to achieve the suppression' of disfavored speech" violates the First Amendment. Because the Supreme Court has not clearly identified the standard of review applicable to these cases, this Court applies strict scrutiny.}

Whether it's a woman's right to choose, or the right to talk about it, Plaintiff's position is the same—"don't tread on me." Under the facts of this case, the First Amendment prohibits the State of Florida from trampling on Plaintiff's free speech.

See also my post from last week on this case.

Note that NRA v. Vullo, the 2024 Supreme Court precedent on which the court relied, was argued by David Cole of the ACLU (representing the NRA); the petition was filed by the Brewer Law Firm and by me. I think the visible ACLU-NRA / left-right alliance helped the NRA prevail, but also, as this case illustrates, helped ACLU in its broader agenda. The underlying principle—that the First Amendment limits the government's power to deter speech by threatening intermediaries (banks or insurance companies in NRA v. Vullo, TV stations here)—protects all speech, whether the NRA's pro-gun-rights speech or pro-abortion-rights speech such as that of the plaintiffs here.

Christina Ford, Emma Olson Sharkey, Daniel Tilley, Samantha Past, and Nicholas Warren (ACLU Foundation of Florida), Ben Stafford and Renata O'Donnell (Elias Law Group LLP), and Jennifer Blohm (Meyer, Blohm and Powell, P.A.) represent plaintiffs.

The post Court Holds the First Amendment Bars Florida from Threatening Media with Criminal Punishment for Spreading Supposed Health-Related Disinformation appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] 7 J——-S, 8 Opinions

Unfortunately, in this instance, it's "Justices," not "Jews" (at least not mostly), which would have been funnier. The case is State ex rel. Spung v. Evnen, from the Nebraska Supreme Court, and deals with a state constitutional separation of powers question related to a felon reenfranchisement statute; the opinions are an unsigned per curiam announcing the judgment of the Court, with each Justice also writing a separate opinion (shades of the Pentagon Papers case, which had one per curiam plus an opinion from each of the nine Justices). Here's the per curiam:

The Nebraska Secretary of State (Secretary) announced in the summer of 2024 that he would not implement recent statutory amendments providing that individuals who have been convicted of felonies are eligible to vote as soon as they complete their sentences. The Secretary took the position that the statutory amendments were unconstitutional. Individuals who were convicted of felonies and who had completed their sentences responded by filing this action in which they seek a writ of mandamus directing the Secretary and two named county election commissioners to implement the 2024 amendments and allow them to register to vote. Because the requisite number of judges have not found that the statutory amendments are unconstitutional, we issue a peremptory writ of mandamus directing the Secretary and the election commissioners to implement the statutory amendments immediately….

The Nebraska Constitution divides the powers of state government "into three distinct departments, the legislative, executive, and judicial." Neb. Const. art. II, § 1. It also states that "no person or collection of persons being one of these departments shall exercise any power properly belonging to either of the others except as expressly directed or permitted in this Constitution." Id. This separation of powers provision has been a part of the Nebraska Constitution since 1875.

Provisions governing voting rights and elections have also been part of the Nebraska Constitution since 1875. The constitution provides that "[a]ll elections shall be free; and there shall be no hindrance or impediment to the right of a qualified voter to exercise the elective franchise." Neb. Const. art. I, § 22. Qualified voters are defined in article VI, § 1, of the constitution to mean "[e]very citizen of the United States who has attained the age of eighteen years … and has resided within the state and the county … for the terms provided by law … except as provided in section 2 of this article …." Article VI, § 2, identifies voters who are disqualified from voting. It provides, "No person shall be qualified to vote who is non compos mentis, or who has been convicted of treason or felony under the laws of the state or of the United States, unless restored to civil rights." Neb. Const. art. VI, § 2.

Also relevant to this case is the provision of the Nebraska Constitution that authorizes the granting of pardons and other forms of clemency. The 1875 constitution authorized the Governor to "grant reprieves, commutations and pardons after conviction, for all offenses, except treason and cases of impeachment, upon such conditions and with such restrictions and limitations as he may think proper, subject to such regulations as may be provided by law relative to the manner of applying for pardons." Neb. Const. art. V, § 13 (1875). That provision was amended in 1920 to transfer clemency powers from the Governor to a pardons board comprised of the Governor, the Attorney General, and the Secretary. See Neb. Const. art. IV, § 13 (1920). Currently, article IV, § 13, of the constitution addresses the pardon power and provides in relevant part: "The Governor, Attorney General and Secretary of State, sitting as a board, shall have power to remit fines and forfeitures and to grant respites, reprieves, pardons, or commutations in all cases of conviction for offenses against the laws of the state, except treason and cases of impeachment." …

[I]n 2024, the Legislature passed L.B. 20, which … [means the relevant state statute] now provides: "Any person sentenced to be punished for any felony, when the sentence is not reversed or annulled, is not qualified to vote until such person has completed the sentence, including any parole term. The disqualification is automatically removed at such time." …

Two days before L.B. 20 became effective, the Attorney General released an advisory opinion in response to a request from the Secretary. The opinion, as summarized, concluded that L.B. 20 and L.B. 53 violated the Nebraska Constitution because the constitution vests the power to restore a felon's right to vote in the Board of Pardons, not the Legislature.

The same day that the Attorney General released his opinion, the Secretary announced that he was "directing county election offices to stop registering individuals convicted of felonies who have not been pardoned by the Nebraska Board of Pardons." The Secretary informed county election officials that "we will not be implementing LB20 and will no longer register individuals convicted of felonies under the laws of Nebraska unless their voting rights have been restored by the Board of Pardons." …

The relators ask us to issue a writ directing the Secretary and the election commissioners to implement the reenfranchisement provisions of L.B. 20. They claim L.B. 20 grants individuals convicted of felonies who have completed their sentences a clear right to register to vote and, correspondingly, imposes a clear duty on the Secretary and election commissioners to permit such individuals to register through voter registration forms required by the statute. They also argue that because the 2024 general election will occur in a matter of weeks, they have no other adequate remedy at law…. The respondents argue that because the reenfranchisement provisions of L.B. 20 are unconstitutional, not only is there no clear duty for them to implement the statutes, but it would violate the law for them to do so….

As with any claim that a statute is unconstitutional in this court, the respondents' defense implicates article V, § 2, of the Nebraska Constitution, which provides in part: "No legislative act shall be held unconstitutional except by the concurrence of five judges." In this case, as demonstrated in more detail in the separate opinions that follow, fewer than five judges find that the reenfranchisement provisions of L.B. 20 are unconstitutional. Accordingly, the respondents have not established that the reenfranchisement provisions of L.B. 20 are unconstitutional….

As I read it, four Justices concluded that L.B. 20 was at least likely constitutional, because the Nebraska Constitution should be understood to reserve for the legislature some authority to restore voting rights; one Justice (Chief Justice Heavican) wouldn't reach the question; and two Justices concluded that L.B. 20 was unconstitutional. As a result, Nebraska's unusual supermajority requirement for invalidating statutes—the requirement that five of the seven Justices agree that a statute is unconstitutional before it can be invalidated—appears not to be dispositive here.

The post 7 J——-S, 8 Opinions appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Supreme Court Refuses to Stay Biden EPA Power Plant Rule

This past spring, in Ohio v. EPA, a 5-4 Supreme Court stayed the implementation of an Environmental Protection Agency rule governing interstate air pollution pending legal proceedings challenging the rule on the merits. This decision was unusual, but not without precedent. Back in 2016 the Supreme Court had also stayed the Obama Administration's Clean Power Plan–also by a 5-4 vote.

The Court's apparent willingness to press pause on major air pollution regulations, combined with an overall increase to consider aggressive "shadow docket" filings, encouraged industrial groups and conservative states to file multiple applications for stays of other EPA rules. After all, if the Court did it twice, it could do it again. None of these recent applications have been successful however.

At the Court's long conference, the justices denied multiple applications seeking stays of EPA rules governing hazardous air pollutants and methane emissions. Then, yesterday (in a more closely watched case), the Court rejected applications seeking a stay of the Biden Adminsitration's rules limiting greenhouse gas emissions from power plants (basically the Biden Administration's replacement for the CPP). Only Justice Thomas dissented. (Justice Alito did not participate.) [See also Sam Bray's post on the application denial.]

Some seem surprised by the Court's actions, but I don't think they should be. The reasons for granting stays of the CPP and interstate air pollution rule were not present in these other cases.

The stay of the CPP was somewhat unusual, but it also presented the Court with an unusual dilemma (as I noted at the time). The Court had recently decided Michigan v. EPA, in which the justices concluded that EPA regulations governing mercury emissions from power plants were arbitrary and capricious. The EPA did not care much about this ruling, however, and trumpeted that fact. After the decision, EPA put out a press release saying (correctly) that nearly all of the regulated utilities had already made the required capital investments while the litigation was pending because there was no way to comply with the deadlines otherwise. Those who sought to stay the CPP highlighted this, basically telling the Court the EPA was celebrating its ability to impose regulations without complying with the law. That the EPA also declared that the CPP represented a pathbreaking and unusually aggressive assertion of agency authority was only icing on the cake.

While the interestate air pollution rule did not present the same sort of major question as the CPP, it was another instance in which the petitioners–and utilities in particular–could plausibly claim that they would have no choice but to make substantial and irreversible capital investments to comply with the rule while judicial review was ongoing. Thus, they could claim some degree of irreparable harm (and more harm than routine compliance costs; on this point, see Sam Bray's excellent post below).

The more recent stay applicaitons tried to present the rules in question as presenting the same sorts of issues, but they were unsuccessful at doing so. These other rules are not as broad or aggressive as the CPP, and do not present the same sort of risk of irreparable harm, in part because the EPA has been more attentive to providing compliance deadlines that accommodate some amount of judicial review. In the case of the most recent power plant rules, it is also notable that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, in its order denying the stay, took the time to explain its decision while also expediting the petitioners' legal challenges so that regulated entities would not be forced to make major compliance expenditures before the litigation could proceed.

Justice Kavanaugh (joined by Justice Gorsuch) made note of some of this in a brief opinion respecting the denial of the applications.

In my view, the applicants have shown a strong likelihood of success on the merits as to at least some of their challenges to the Environmental Protection Agency's rule. But because the applicants need not start compliance work until June 2025, they are unlikely to suffer irreparable harm before the Court of Appeals for the D. C. Circuit decides the merits. So this Court understandably denies the stay applications for now. Given that the D. C. Circuit is proceeding with dispatch, it should resolve the case in its current term. After the D. C. Circuit decides the case, the nonprevailing parties could, if circumstances warrant, seek appropriate relief in this Court pending this Court's disposition of any petition for certiorari, and if certiorari is granted, the ultimate disposition of the case.

Going forward, what I think this means is that the Court is settling on a reasonable standard for evaluating stay requests for major regulations. As a general matter, particularly if the EPA sets reasonable compliance deadlines, such stays should be denied. But where we have some combination of a particularly aggressive assertion of agency authority (again, think "major question") and a compliance schedule that will prematurely force regulated entities to make substantial capital investments (perhaps, particularly, if those regulated entities are rate-regulated utilities, which operate under greater constraints), a stay is more likely. This also means that regulatory agencies and the D.C. Circuit can make stays less likely by taking care to consider such factors themselves.

This is all a long way of saying that the justices are willing to offer extraordinary relief in extraordinary cases, but that it is far from open season on major environmental rules.

The post Supreme Court Refuses to Stay Biden EPA Power Plant Rule appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers