Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 242

October 20, 2024

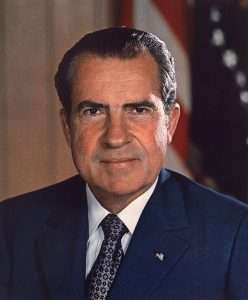

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 20, 1973

10/20/1973: The Saturday Night Massacre occurs.

President Richard Nixon

President Richard NixonThe post Today in Supreme Court History: October 20, 1973 appeared first on Reason.com.

October 19, 2024

[Josh Blackman] When Did The Supreme Court Come Out "The Other Way Than Every Court of Appeals"?

Co-Blogger Jon Adler flagged an exchange in Royal Canin U.S.A., Inc. v. Wullschleger. Chief Justice Roberts asked Ashley Keller if there were any cases where the Supreme Court "came out the other way than every court of appeals had come out." Keller was not able to think of an example on the spot. After a few moments, Roberts thought of a case:

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Was that -was that the case in Chadha?

MR. KELLER: INS versus Chadha?

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Yes. MR. KELLER: I –I don't know. I apologize.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Somebody will check. I just –

JUSTICE KAGAN: Gosh, I'm not sure which way that cuts.

(Laughter.)

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: I'm not sure that's true. I just have it in the back of my mind, but –okay.

Yes, someone would "check" that. His name is Seth Barrett Tillman. Seth reminded me that in Chadha, the Supreme Court affirmed the Ninth Circuit. And do you know who wrote the circuit court opinion in Chadha? Judge Anthony M. Kennedy. AMK ruled that the one-house veto violated the separation of powers. So Chief Justice Roberts is wrong on this front. Even better, Antonin Scalia filed an amicus brief on behalf of the American Bar Association supporting affirmance!

But there is one fairly prominent case in which the Supreme Court came out the opposite way of all lower federal courts: Brown v. Board of Education. The Court reversed three federal courts in Kansas, South Carolina, and Virginia. Of course, the Court affirmed the Delaware Supreme Court, which found that the separate schools were not equal.

The post When Did The Supreme Court Come Out "The Other Way Than Every Court of Appeals"? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Mich. S. Ct. Declines to Review Decision Upholding U. Michigan Gun Ban

The case is Wade v. Univ. of Mich.; as is common for such denials of review, the majority didn't offer a detailed opinion, but Justice David Viviano, joined by Justice Brian Zahra, dissented:

In 2001, the University adopted Article X, which bans the possession of firearms on its campus or "any property owned, leased or otherwise controlled" by the University. That prohibition applies to all persons regardless of whether they possess a concealed-carry permit. Plaintiff unsuccessfully applied for a waiver under Article X. The record indicates that plaintiff does not work, reside, or study at the University and has a concealed-carry permit….

[T]he Court of Appeals disregarded the analysis required by the United States Supreme Court for Second Amendment disputes and invented a confusing four-factor test that bears almost no resemblance to the Supreme Court's test. On remand, the Court of Appeals set forth the following factors for resolving Second Amendment challenges:

1) Courts must first consider whether the Second Amendment presumptively protects the conduct at issue. If not, the inquiry ends and the regulation does not violate the Second Amendment.

2) If the conduct at issue is presumptively protected, courts must then consider whether the regulation at issue involves a traditional "sensitive place." If so, then it is settled that a prohibition on arms carrying is consistent with the Second Amendment.

3) If the regulation does not involve a traditional "sensitive place," courts can use historical analogies to determine whether the regulation prohibits the carry of firearms in a new and analogous "sensitive place." If the regulation involves a new "sensitive place," then the regulation does not violate the Second Amendment.

4) If the regulation does not involve a sensitive place, then courts must consider whether the government has demonstrated that the regulation is consistent with this Nation's historical tradition of firearms regulations. This inquiry will often involve reasoning by analogy to consider whether regulations are relevantly similar under the Second Amendment. If the case involves "unprecedented societal concerns or dramatic technological changes," then a "more nuanced approach" may be required.

The first factor accurately reflects the principle that the Second Amendment presumptively protects a citizen's right to keep and bear arms. On the basis of this factor, the Court of Appeals concluded that plaintiff is a "law-abiding, adult citizen" who enjoys Second Amendment protection….

Concerning the second factor, the Court of Appeals concluded that the University is a school and a sensitive place and that Article X is constitutional because regulations forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places are consistent with the Second Amendment. The Court of Appeals also stated that courts may only employ historical analogies when a firearm regulation does not have a direct historical precedent….

In Heller, the Supreme Court stated in dicta that its holding did not call into question "longstanding" laws that forbid "the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings …." In Bruen, the Supreme Court expressly declined to "comprehensively define 'sensitive places,'" although, interestingly, it rejected an approach that would extend the concept across large areas, such as the island of Manhattan. Arguably, the Court of Appeals' conclusion that the entire campus of the University of Michigan—spanning one-tenth of Ann Arbor—does what Bruen rejected and extends sensitive places across large swaths of territory….

In any event, Bruen makes it clear that sensitive places are those locations where firearms have been historically regulated. This conclusion reflects Bruen's general text-and-history approach to Second Amendment rights, under which courts must "examine any historical analogues of the modern regulation to determine how these types of regulations were viewed." … The Court did not exempt sensitive places from this historical approach. Rather, in Bruen, it described sensitive places as those locations where "'longstanding' 'laws forbidding the carrying of firearms'" existed. Put differently, a sensitive place is one in which firearms have historically been forbidden….

Yet the Court of Appeals tried to take a shortcut here. As can be seen from its multifactor test, the Court suggested that any historical analysis is unnecessary if a location is a sensitive place. This completely ignores that sensitive places are those locations with historical regulations. And in applying its newly fabricated test, the Court once again offered little more than an analysis of whether universities are schools, this time relying solely on modern definitions of schools…. As I noted before, my own review of historical gun restrictions on campuses and the secondary literature on the topic has not uncovered any tradition of complete firearm bans, only partial and targeted prohibitions, e.g., regulations on the discharge of firearms on campus.

It seems doubtful that after establishing a text-and-tradition approach to the Second Amendment, the Supreme Court would uphold total bans on firearms in locations that historically never had such prohibitions. Indeed, such a regulation would not be supported by text or tradition, so what reasoning could support it? A rationale grounded in the pragmatic balancing of interests was rejected in Bruen, as discussed above. I therefore struggle to see how the Court of Appeals' framework here, which eschews text and tradition altogether, can be justified under the Supreme Court's precedent.

{

Most courts that have recently addressed these regulations have recognized that they do not support a total prohibition of firearms on university campuses. See United States v Metcalf (D. Mont. 2024) ("The Court is unconvinced by evidence of these early university bans because they were not regulations on carrying weapons in "sensitive places." Rather, they banned certain persons—students—from carrying weapons. The University of Georgia restriction banned students from carrying weapons anywhere. Neither the University of Virginia ban nor the University of North Carolina ban applied to faculty members or to members of the community, so they, too, only banned certain persons from carrying weapons."); United States v Allam (E.D. Tex. 2023) ("In any event, although these enactments occurred close to our Nation's founding, the prohibitions applied to students only, and, thus, the university campus 'was not a place where arms were forbidden to responsible adults,' much less within 1,000 feet of campus…. Moreover, three university regulations that applied only to students cannot be said to be representative of our Nation's tradition of firearms regulation."). The Court of Appeals relied on, among other things, two recent out-of-state federal cases for the proposition that a university is a college campus. United States v Power (D. Md. 2023); United States v Robertson (D. Md. 2023). These courts were less thorough in their analysis, however. Neither case addressed college or university campuses; instead, both examined a nonschool government location. While the court in both cases did analogize the location to universities, the court addressed only three historical regulations, none of which totally prohibited firearms on campus. In a third case cited by the Court of Appeals, the decision upheld a prohibition on carrying concealed weapons, not a total ban; in doing so, the court cited various additional historical examples of limited prohibitions on student possession of firearms and the carrying of firearms in school rooms, not across entire campuses. Antonyuk v Hochul (N.D.N.Y. 2022). Tellingly, too, all these decisions at least attempted to do the historical analysis that the Court of Appeals said was unnecessary here.}

Here's an excerpt from the Court of Appeals' opinion:

In Bruen, the Court stated that it was "settled" that arms carrying could be prohibited consistent with the Second Amendment in locations that are "sensitive places." The Court explained that, although the historical record showed relatively few 18th and 19th century "sensitive places," such as legislative assemblies, polling places, and courthouses, there was no dispute regarding the lawfulness of prohibitions on carrying firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings. The Court's statements indicate that, even though 18th and 19th century "sensitive places" were limited to legislative assemblies, polling places, and courthouses, laws prohibiting firearms in schools and other government buildings are nonetheless consistent with the Second Amendment. Thus, if the University is a school or government building, then Article X does not violate the Second Amendment….

Samuel Johnson's dictionary from 1773 defines "school," in part, as: "A house of discipline and instruction[,]" and "[a] place of literary education; an university." It defines "university" as "[a] school, where all the arts and faculties are taught and studied." Thus, considering either time period, the term "school" included universities.

Notably, the reference to "schools" being sensitive places was first made by Justice Scalia in Heller. In discussing the "longstanding" tradition of laws forbidding firearms in sensitive places such as "schools and government buildings," Justice Scalia did not define the term "school," nor did he cite or rely on any authority. Given that the term "school" is not found in the Second Amendment, but was first used by Justice Scalia, it is not clear that either 1791 or 1868 are the correct time periods to determine the meaning of that term as used in Heller. Nonetheless, the plain meaning of "school" when Justice Scalia used the term in 2008 similarly includes universities….

Other courts have concluded that universities are schools, and thus, "sensitive places." See DiGiacinto v Rector & Visitors of George Mason Univ (Va. 2011) ("The fact that [George Mason University (GMU)] is a school and that its buildings are owned by the government indicates that GMU is a 'sensitive place.' "). See also United States v Power (D. Md. 2023); United States v Robertson (D. Md. 2023) ("[T]he Court determines that a regulation centered on a 'college campus' falls under 'schools' and within the sensitive places doctrine."). In Power and Robertson, the court upheld the National Institute of Health (NIH)'s regulation banning firearms on its campus because the NIH is a sensitive place. Thus, the challenged regulation did not violate the Second Amendment. The court explained that Bruen never said only "elementary schools" or "middle schools," and the terms "schools and government buildings are presented as broadly as possible, allowing the reader to consider all possible subtypes that fall within those two examples." Finally, in Antonyuk v Hochul (N.D.N.Y. 2022), the court upheld a New York restriction on concealed carry at colleges and universities….

Relatedly, plaintiff suggests that while "some specific parts" of the University's campus may be considered "sensitive areas," the entire campus is not a "sensitive area." Plaintiff's suggestion is untenable because it would require that certain "areas" of the University be partitioned off from other areas of the University, and other "sensitive places" like courthouses would likewise have to be partitioned. More importantly, plaintiff provides no support for partitioning "sensitive areas" and no such support can be found in Heller or Bruen, which used the term "schools" and "government buildings" broadly….

We acknowledge that the parties, as well as the amici, present numerous policy arguments both in support of and against Article X. In brief, the University argues that, in addition to public safety concerns, the presence of firearms works against its important goals of protecting First Amendment freedoms and the free flow of information. The Michigan Attorney General argues that: courts should not interfere with state and local decisions; university students believe learning is hampered if firearms are permitted on campus; and the University would be an outlier among colleges and universities if its ordinance were struck down. Brady argues that Article X protects speech and the free exchange of ideas and furthers the University's core educational goals. Giffords similarly argue that guns on campuses chill speech, impede learning, and pose unique safety risks. Further, there is no evidence that the presence of guns would decrease mass shootings.

Plaintiff, however, argues that guns increase public safety. He further argues that the concerns regarding violence, suicide, and alcohol abuse may relate to students, but not to him, and the free flow of information is not a concern at the places of his proposed conduct. GOA similarly argues that Article X is far too broad, potentially affecting more than 88,000 people and effectively operating as a city-wide ban, which is impermissible.

Clearly, the efficacy of gun bans as a public safety measure is a matter of debate. However, because the University is a school, and thus a sensitive place, it is up to the policy-maker—the University in this case—to determine how to address that public safety concern….

The post Mich. S. Ct. Declines to Review Decision Upholding U. Michigan Gun Ban appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Interesting and Detailed N.Y. Times Article About DEI at the University of Michigan

It's The University of Michigan Doubled Down on D.E.I. What Went Wrong?, by Nicholas Confessore; the subtitle is "A decade and a quarter of a billion dollars later, students and faculty are more frustrated than ever."

The post Interesting and Detailed N.Y. Times Article About DEI at the University of Michigan appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Journal of Free Speech Law: "The Unfortunate Consequences of a Misguided Free Speech Principle," by Robert Post

The article is here; the Introduction:

There is growing pessimism about the future of free speech in the United States. Crusaders from all sides of the political spectrum seem intent on suppressing objectionable discussion. The worry is that Americans may be losing their appetite for candid and constructive dialogue. It has become too costly to participate in public discourse. We fear that incorrect speech will be canceled by the left or bullied by the right.

This is surely a troubling state of affairs. But it can be cured only if we first correctly diagnose its causes. There is a widespread tendency to conceptualize the problem as one of free speech. We imagine that the crisis would be resolved if only we could speak more freely. But this diagnosis puts the cart before the horse. The difficulty we now face is not one of free speech, but of politics. Our capacity to speak has been disrupted because our politics has become diseased. We misconceive the problem because American culture is obsessed with what has become known as the free speech principle. It is a principle that is widely misunderstood. Our misconceptions are as deep and as they are consequential.

I shall take as my text a representative and much-discussed 2022 opinion piece by the editorial board of The New York Times entitled "America Has a Free Speech Problem." In its first sentence, the editorial warned that Americans "are losing hold" of the "fundamental right" to "speak their minds and voice their opinions in public without fear of being shamed or shunned." The editorial did not focus its attention on government regulation of speech, which is the particular domain of the constitutional law of the First Amendment, but instead on the more basic question of free speech itself. It urged Americans to extend to each other the fundamental right to say whatever is on their minds. The editorial suggested that the more speakers could express their thoughts, the more our politics would heal. It implied that the current dislocation of our politics could be solved by more speech.

The editorial's framing of the issue is not idiosyncratic. Advocates of a free speech principle abound. Yet the editorial rests on a misguided understanding of free speech.

Whatever freedom of speech might signify, it does not mean that unrestrained expression is inherently desirable. It does not mean that more speech is always better. One can see this clearly if one imagines the limit case. Those who cannot stop talking, who cannot exercise self-control, do not exemplify the value of free speech. They instead suffer from narcissism. Unrestrained expression may be appropriate for patients in primal scream therapy, but scarcely anywhere else.

Normal persons ordinarily feel constrained to speak discreetly. I might detest my friend's wife, but I will refrain from telling him so in ways that might hurt his feelings. Speech is the foundation of all human relationships, but no human relationship can exist without tact or discretion. No friendship can survive unrestrained communication that ruptures elemental norms of mutual respect. More speech is not always better.

No doubt friendship also requires candor and spontaneity. Sometimes friends must articulate to each other truths that are unpalatable and difficult to express. How then do we balance the need to speak freely against the need for tact? The answer is that we should choose to speak in ways that will make our friendship as good as it can be. We speak when it improves the quality of friendship; we exercise self-restraint when it improves the quality of friendship. The relevant good we seek to achieve is friendship, not more speech.

The same logic applies to almost all human relationships. We do not value speech from the solipsistic perspective of the speaker. Instead, speech that contributes to the excellence of a relationship is valued; speech that undermines the value of a relationship is suppressed. Consider, for example, the lawyer who speaks to a court or a client. The lawyer does not simply say what is on her mind, nor would it be a good thing if she did. The lawyer's goal is not to produce the maximum number of words. The goal of the lawyer is instead to produce the best possible results for her client. To achieve that goal, a lawyer must balance candid expression against tactful self-restraint.

In my own capacity as a professor of law, I would never assess the success of my classes by the number of words I have expressed. I rarely simply blurt out what is on my mind. I instead try to speak in ways that maximize the educational value of my classes. This means that I always balance self-restraint against spontaneous self-expression. There is no principle of free speech that can override this simple, essential, and universal logic.

This suggests that the premise of the New York Times editorial, while familiar from continuous iteration, is fundamentally misguided. Abstract principles of free speech tend to rest on unstated and undefended premises about the desirability of an uninhibited and unrestrained flow of words. But in actual life, we know full well that human speech always transpires in the context of concrete relationships. This means that we never value speech as such. We instead prize the good of the relationships within which speech is embedded. We do not honor the speech of friends; we honor friendship. The eloquence and advice of lawyers are not important except insofar as they advance the rule of law. Classroom discussion is not significant in itself; it is only valuable insofar as it facilitates education. And so on. All such judgments are substantive and contextual.

The post Journal of Free Speech Law: "The Unfortunate Consequences of a Misguided Free Speech Principle," by Robert Post appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Justice Kagan Does Not Like INS v. Chadha

Another interesting tidbit from the oral argument in Royal Camin USA v. Wullschleger concerned what weight the Court should give unanimity on a question among the lower courts of appeals. (In this case, the lower courts of appeals have treated the post-removal amendment of a complaint in one way, but there is an argument the relevant statutory requires a different result.)

In the exchange, Justice Kagan suggests she is not a fan of INS v. Chadha (the decision in which the Court held that a unicameral legislative veto is unconstitutional).

From the transcript:

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Counsel, we have had cases where we came out the other way than every court of appeals had come out, right?

MR. KELLER: Yes, you have, Mr. Chief Justice.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Like what?

MR. KELLER: I think there are—that's a great question.

(Laughter.)

MR. KELLER: And none spring to mind, but I am positive that I can find some.

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: Central Bank?

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Well, I mean, it's pretty bold to take the position without knowing one.

MR. KELLER: Fair. Mea culpa.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Was that—was that the case in Chadha?

MR. KELLER: INS versus Chadha?

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Yes.

MR. KELLER: I—I don't know. I apologize.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Somebody will check. I just —

JUSTICE KAGAN: Gosh, I'm not sure which way that cuts.

(Laughter.)

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: I'm not sure that's true. I just have it in the back of my

mind, but—okay.

The post Justice Kagan Does Not Like INS v. Chadha appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Justices Alito and Sotomayor on How Courts Read Dicta

Catching up on Supreme Court oral arguments, I was struck by the following exchange in Royal Canin U.S.A. v. Wullschleger (a case about the effects of post-removal amendments to a complaint) in which Justice Sotomayor suggested that some lower court judges are taking their cues from dicta in Supreme Court opinions.

From the transcript:

JUSTICE ALITO: Well, do you think that—that courts of appeals read our

decisions differently than we may? I mean, you know, I'm—I was on a

court of appeals for 15 years. If I saw a strong dictum in a Supreme Court decision, I

would very likely just salute and move on. But, here —(Laughter.)

JUSTICE ALITO:—we have —

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Not now.

(Laughter.)

JUSTICE ALITO:—more of an obligation—it depends, Justice Sotomayor —(Laughter.)

JUSTICE ALITO:—both when we're considering—you know, when we're considering

what we've written—we know how these things are written. You know, we know how these footnotes are written. Can—do we have liberty to read them a little bit differently?

Listening to the audio, I took Justice Alito to be suggesting there is dicta and then there is dicta, and justices (particularly those who may have been on the Court at the time) can often tell the difference. I also took Justice Sotomayor to be suggesting that some lower courts don't merely "salute and move on" when they see "strong" dicta in a Supreme Court opinion, but rather take that dicta as their cue for how to proceed and push beyond settled precedent. Justice Alito's response suggests to me he interpreted her comment in the same way. (Again, this may be more clear on the audio.)

I am not sure which case(s) Justice Sotomayor had in mind, but there are many potential candidates.

The post Justices Alito and Sotomayor on How Courts Read Dicta appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 19, 1789

10/19/1789: Chief Justice John Jay takes oath.

Chief Justice John Jay

Chief Justice John JayThe post Today in Supreme Court History: October 19, 1789 appeared first on Reason.com.

October 18, 2024

[John Ross] Short Circuit: A Roundup of Recent Federal Court Decisions

Please enjoy the latest edition of Short Circuit, a weekly feature written by a bunch of people at the Institute for Justice.

Last week, IJ's cofounder and former president Chip Mellor passed away after a battle with leukemia. Godspeed, Chip. You're a legend. Click here to learn more.

New on the Short Circuit podcast: What happens when the gov't claims it doesn't enforce the law? It avoids a lot of civil rights lawsuits.

Economists like to say that incentives matter. Consider, for example, the incentives created by a prenup under which a man's wife receives $8 mil if he dies, but only $3.5k a month for 36 months if they divorce within a year. First Circuit: Murder-for-hire convictions affirmed. Can the State of New York assert parens patriae standing to sue a school district for its alleged failure to address repeated complaints of student-on-student sexual assault, sexual harassment, and gender-based violence and bullying? Second Circuit: It certainly can. Concurrence dubitante: That seems pretty screwy, but our whole jurisprudence of parens patriae standing is screwy, so the Supreme Court should clear this up. If one of your aims in life is to figure out whether a "subsection" is anything within a "section" or, alternatively, only the next-smallest-thing within a "section" but not something smaller, than that then your ship has come in. You'll also need to wade through whether a registered nurse must be part of certain investigations under the Medicaid Act, but otherwise your perusal of this Second Circuit opinion (no on nurses needed), including the dissent (yes on nurses needed), will be totally worth it. The Video Privacy Protection Act was passed in 1988 after a reporter dug into the video-rental history of Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork (and discovered it to be entirely non-salacious). But does this dusty law written in the era of VHS tapes have any continuing vitality? Second Circuit: "The VPPA is no dinosaur statute." Thus, a lawsuit alleging that the NBA violated a basketball fan's rights when it disclosed his video-watch history to Meta Platforms may proceed. In 2021, Texas enacts a law restricting paid "vote harvesting services," defined as "interaction with one or more voters, in the physical presence of an official ballot or a ballot voted by mail, intended to deliver votes for a specific candidate or measure." The law is challenged in August 2021, but the district court doesn't get around to enjoining it until September 28, 2024, three weeks before voting begins in Texas. The state moves to stay the injunction. Fifth Circuit: And it is stayed. Under the Purcell principle, you can't mess around with things this close to an election. Man is celebrating his birthday in Detroit and listening to street musicians when a police officer tells him to move along. They argue for a bit, and the man is passively resisting arrest by hugging his girlfriend when the officer tases him without warning. Qualified immunity for excessive force? Sixth Circuit: Nope, it's "clearly established in this circuit that an individual has a constitutional right not to be tased when he or she is not actively resisting." Anticipating that the district attorney's office would announce it would not prosecute a police officer who shot a Black teenager, and in the midst of 2020 unrest over similar deaths, Wauwatosa, Wisc. officials impose a five-day nighttime curfew and arrest or ticket several protestors for violating it. Seventh Circuit: Which did not violate the First Amendment because it was a content-neutral measure appropriately tailored to the exigencies of the situation. (And NB: Don't ignore a district court when it tells you to be very careful in amending your complaint about whether you are suing gov't defendants in an official or individual capacity.) Hoax phone call brings police to Pasadena, Calif. home in search of a non-existent suicidal resident. Yikes! It turns out two federal law enforcement officers live at the home, and they file a complaint about the guns-drawn search, during which officers rifled through drawers and personal effects. In response, the police chief issues a press release that includes bodycam footage that purports to show his officers behaving appropriately, but that also reveals the location of the home. Federal officers: Which was retaliation and put our lives in danger—we had to move to a different city. District court: No qualified immunity. Ninth Circuit (unpublished): Qualified immunity. Plaintiff: Colorado law says I'm not allowed to build a septic tank without a permit, but my county says they won't give me a permit until I'm done building my septic tank! My 22 has been caught! I'm choosing a Sophie! I mean, this is unconstitutional! Tenth Circuit: That sounds like a crappy system, but that doesn't mean it violates due process. Did the Jenks, Okla. police department have jurisdiction to investigate a man for the 2018 murder of his ex's boyfriend on the Muscogee Creek Reservation? Tenth Circuit: Not after the U.S. Supreme Court's 2020 decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma, but no need to suppress the evidence because state officers acting in good faith could reasonably believe that they had jurisdiction to investigate in 2018. Conviction affirmed. Plaintiff landowner (and successful SCOTUS litigant) complains that the county's land-use ordinances make it impossible for him to develop his land, roughly 97% of which is underwater. Eleventh Circuit: Well, you've never asked them if you could build anything, so maybe swim on over with a variance application or something first. It's not an appellate case yet, but a friend of the newsletter informs us that this successful habeas petition from Puerto Rico—in a brutal triple murder from 1989—is a big story that has not yet hit the mainland, and some Google-translate-enabled sleuthing suggests that it will soon be headed to the First Circuit. With section headings like "Pandemonium at the Crime Scene" and "Investigators Contaminate, Discard, and Destroy Critical Evidence," this one's a doozy. And in en banc news, the Sixth Circuit will not reconsider its refusal to remove RFK Jr. from the Michigan presidential ballot. Judge Clay sharply concurs, calling the First Amendment argument presented by "Plaintiff and our dissenting colleagues" "completely fraudulent" in light of Kennedy's lawsuit in New York trying to remain on that state's presidential ballot. The dissenting colleagues, meanwhile, point the finger at the Michigan Secretary of State, who is alleged to have illegally placed Kennedy on the ballot, perhaps to draw votes away from a certain controversial major-party candidate. And in granted/vacated/remanded news, the Supreme Court has sent back to the Fifth Circuit for a rethink in light of (IJ mega hit) Gonzalez v. Trevino . After Ms. Villarreal—a citizen-journalist and known critic of law enforcement—asked a Laredo, Tex. officer to confirm facts that were part of a developing story, she was arrested for the crime of "soliciting" non-public information (a crime that's never been enforced in the decades it's been on the books). Back in January, the Fifth Circuit ruled 9-7 that the arrest was A-OK. (IJ filed an amicus brief urging a rethink. And, while we're tooting this horn, please don't fail to note that this is the second time in as many weeks that a bad First Amendment ruling has been GVR'd in light of Gonzalez.)New case: Last month, Kalispell, Mont. city council members voted to shut down the Flathead Warming Center, a 50-bed homeless shelter located in a commercial area, as winter approaches. The shelter is clean and well-organized and has not been cited for any code violations. It only opened in its current location (which had been a vacant auto repair shop) after extensive work with elected officials and city staff. But visible homelessness has been on the rise in town (rents have nearly doubled in the last two years), and city leaders have decided to scapegoat the shelter. And though there is a process for dealing with problem properties, here the city council elected to ignore its own rules to revoke the shelter's permit—a permit that, once granted, runs with the land. Next week, a federal judge will consider a motion for temporary restraining order, so that the Warming Center can operate while the case proceeds and nightly temperatures fall below freezing.

The post Short Circuit: A Roundup of Recent Federal Court Decisions appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Journal of Free Speech Law: "The Fate of American Democracy Depends on Free Speech," by Suzanne Nossel

The article is here; the Introduction:

In response to our democratic crisis—polarization, contested elections, political violence—philanthropists, activists, and civic leaders have set about trying to find ways to restore democracy and a vibrant civic culture. Foundations have launched ambitious new programs. Individual philanthropists have convened collaboratives—the Democracy Alliance, the Democracy Funders Network, New Pluralists—aimed to pool resources and insights to shore up the polity. A cottage industry of new organizations has grown over the last seven years to work on voting rights, voter access, election laws and systems, civic participation, and more. These valiant efforts have collectively helped tamp down political unrest, fend off demands to reject the 2020 election result, and defend vulnerable democratic systems at the state level across the country. Many of these efforts are geared not just toward fortifying American democracy in its current form, but also to reinventing it to better meet the needs of a country buffeted by technological, demographic, and social change.

One bulwark of a healthy democracy that these efforts have not sufficiently prioritized, however, is free speech. This is doubly surprising. First, because alongside voting rights and systems, good governance, and civic participation, free speech and open discourse have always formed part of the backbone of a healthy democracy. And second, because free speech and open expression are so clearly under threat today. Controversies over free speech—what can and cannot be said, taught, studied, and read—are fueling grievances that are deepening polarization and distrust in our political system. Yet the battle to uphold free speech has not been incorporated into the broader movement for democracy. It must be.

In this essay, I first describe the loss of faith in free speech on the left and the right and the reasons for it. I then detail the relationship between free speech and democracy, and how it has come under pressure from growing pluralism, polarization, and digitization. I follow by outlining how a flagging commitment to free speech in education, in terms of protest and assembly rights and in relation to the role of the free press, are collectively weakening American democracy. I conclude with a series of recommendations that can help shore up the place of free speech as a democratic cornerstone now and for generations to come.

The post Journal of Free Speech Law: "The Fate of American Democracy Depends on Free Speech," by Suzanne Nossel appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers