Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 245

October 16, 2024

[David Kopel] National Firearms Act Seminar

This Friday, October 18, there will be an all-day seminar on the National Firearms Act, the 1934 federal statute that regulates machine guns, short-barreled rifles and shotguns, sound suppressors, and some other items. Continuing legal education credit is available, and the seminar is free and online. Registration, CLE information, and the schedule are available here.

The seminar is hosted by the University of Wyoming College of Law's Firearms Research Center, where I am a Senior Fellow. This is the first-ever legal seminar on the National Firearms Act, in important topic for anyone who practices general federal criminal law. It begins at 8:30 a.m. Mountain Time, and concludes at 3:30 p.m. If you happen to be in Laramie, you can attend in person. Some readers may remember the call for papers that I posted this summer. The seminar is collaboration with the Wyoming Law Review, which will publish revised versions of papers presented at the seminar.

The program is:

Session 1. Benjamin Hiller, Deputy Associate Chief Counsel for the Firearms & Explosives Law Division at the ATF. Implementation of the National Firearms Act, and insights into legal issues surrounding firearms regulation.

Session 2. David Kopel. The history of machine guns.

Session 3. Stephen P. Halbrook, Yang Liu, Matthew Larosiere, and Charles K. Eldred. The National Firearms Act's impact on regulated arms. Also, tax issues.

Lunch. Kelly Todd of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department. The National Firearms Act's impact on wildlife management and enforcement

Session 4. Tom W. Bell, Chris Land, Clayton Cramer, and Ted Noel. Second Amendment issues. How historical firearms are categorized in the NFA.

Session 5. Michael Williams, General Counsel for the American Suppressor Association. Recent policy developments related to the NFA.

The post National Firearms Act Seminar appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] SpaceX's First Amendment Claim Against California Coastal Commission

The California Coastal Commission recently decided to block SpaceX's increase in annual launches at Vandenberg Space Force Base from 36 to 50. SpaceX has just sued, claiming the decision was preempted by federal authority, violated state law, and also violated the First Amendment. I can't speak to the preemption arguments and the statutory arguments, but I wanted to pass along some thoughts about the First Amendment question.

SpaceX is arguing that the Commission's 6-4 decision was influenced by the Commissioners' disapproval of Elon Musk's politics and speech:

The Commission also made clear that its objection was rooted in animosity toward SpaceX and the political beliefs of its owner Elon Musk, not concern for the coastal zone. After talking at length about concerns with changes in Department of Defense leadership following the November 2024 election, Commission Chair Hart said explicitly: "The concern is with SpaceX increasing its launches, not with the other companies increasing their launches." She explained, "we're dealing with a company … the head of which has aggressively injected himself into the Presidential race and made it clear what his point of view is."

Other Commissioners similarly made clear their decision was based on political disagreements with Mr. Musk. Commissioner Newsom, for instance, said that "Elon Musk is hopping about the country, spewing and tweeting political falsehoods and

attacking FEMA while claiming his desire to help the hurricane victims with free Starlink access to the internet." Commissioners Aguirre and Escalante voiced similar concerns regarding the political uses of Starlink. As these statements show, the impact of the proposed launch cadence increase on the coastal region was the last topic on the Commissioners' minds at the October 2024 meeting.

At the same time, there have also been other arguments given for the decision, related to the potential environmental effects of the launches.

Here's the general rule: The government generally may not deny a license or approval to a regulated entity because of that entity's speech, or the speech of its owners or managers (unless the speech falls within a First Amendment exception, such as for true threats of illegal conduct). "[T]he standard for evaluating whether a regulated entity has established a claim of retaliation based on the exercise of free speech rights," to quote CarePartners LLC v. Lashway (9th Cir. 2008), is:

A "plaintiff alleging retaliation for the exercise of constitutionally protected rights must initially show that the protected conduct was a 'substantial' or 'motivating' factor in the defendant's decision." If the plaintiff makes this initial showing, the "burden shifts to the defendant to establish that it would have reached the same decision even in the absence of the protected conduct." To meet this burden, a defendant must show by a preponderance of the evidence that it would have reached the same decision; it is insufficient to show merely that it could have reached the same decision.

Likewise, here SpaceX would likewise have to show—presumably based on evidence such as the Commissioners' statements (as alleged in the Complaint)—that Musk's political activity was a substantial or motivating factor in the Commission's 6-4 decision. If it does make that showing, then the burden would shift to the Commission to show that it would have denied SpaceX's application (notwithstanding facts such as the Department of the Air Force's support for the application) even if Musk's politics had been different, or if Musk had been apolitical. The key question is thus factual, or, to be precise, counterfactual.

Nor would it be enough for the Commission to argue that it "was entitled" to deny the application under state law based on environmental reasons, or that it "could have" rejected the application "in the absence of any" consideration of Musk's constitutionally "protected conduct" (I'm quoting here from Sorrano's Gasco, Inc. v. Morgan (9th Cir. 1989), another Ninth Circuit precedent.) That focus on what the Commission could have done would "mispreceive the import of the … causation analysis" set forth by the Supreme Court in Mt. Healthy City School Dist. Bd. of Ed. v. Doyle (1976):

The Mt. Healthy test requires defendants to show, by a preponderance of the evidence, that they would have reached the same decision in the absence of the protected conduct. The defendants here have merely established that they could have suspended the permits.

Thanks to Hans Bader (Liberty Unyielding) for the pointer to CarePartners.

The post SpaceX's First Amendment Claim Against California Coastal Commission appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Bernstein] Did Yale, Princeton, and Duke Violate SFFA in Last Year's Admissions Cycle?

Following the Supreme Court's decision in SFFA in 2023, barring the use of racial preferences in admissions, admissions patterns at most elite universities followed the pattern one would expect: enrollment of black and Hispanic students declined, and enrollment of Asian-American students increased. Three major exceptions to this pattern are Yale, Princeton, and Duke. At each of these universities, enrollment of black students was basically flat, and enrollment of Asian-American students was actually down. Enrollment of Hispanic students, meanwhile, was flat at Princeton and Duke and actually up at Yale.

In today's New York Times, University of Chicago lawprof Sonja Starr argues that we shouldn't assume that these schools were cheating, and offers 3 alternative explanations:

The first possible reason is that schools do not admit students in a vacuum. They compete for them. Why did fewer Asian American students enroll this year at Yale, Duke and Princeton? Perhaps they went to other elite schools instead … The second plausible explanation for the schools' demographics has to do with the statistics themselves: Duke and Princeton had a large rise in the number of students declining to identify themselves by race. (Yale does not report this figure.) If that rise was concentrated among Asian American students, it could explain the apparent drop-off in their numbers. [DB This would not explain the Hispanic and African American figures.]… The third possible reason the critics' suspicion is unfounded is the most important: It is perfectly lawful for universities to seek to preserve racial diversity. Even if it turns out that colleges are deliberately seeking to keep Black and Hispanic students well represented, this would not in itself raise a legal problem.

Color me skeptical. First, I find it extremely suspicious that all three schools had almost exactly the same percentage of African-American matriculants this year as in the recent past, and two of the three had almost the exact same percentage of Hispanic students. Given what necessarily were substantial changes in their admissions processes, this is an awfully "interesting" coincidence. Relatedly, I find it unlikely that Starr's first explanation would have nearly the dramatic effect it would need to have to explain this year's matriculation results.

Second, each of these schools signed an amicus brief to the Supreme Court stating that there was no way no they could possibly achieve similar racial diversity as in the past without using racial preferences. If Starr is right that the universities in question found other ways to achieve diversity without using race as a factor in admissions, it suggests one of two possibilities, neither of which is flattering. First, the schools knew that they could achieve diversity without using racial preferences but declined to do so, even though pre-SFFA Supreme Court precedent required them to use race only as a last resort, and even though this meant that they were lying in their amicus brief. Second, the schools were able to achieve racial diversity without using racial preferences but had never bothered to try to do so before, again despite precedent requiring them to.

Most likely though, all three schools illegally considered race in filling a soft quota for underrepresented minority students while also avoiding accepting more Asian-American students.

The post Did Yale, Princeton, and Duke Violate SFFA in Last Year's Admissions Cycle? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Paul Cassell] Should the Boeing Plea Deal on the 737 MAX Crashes Be Approved?

For the last several years, I have represented families who lost loved ones in the crashes of two Boeing 737 MAX aircraft (see earlier posts here, here, and here). The families want Boeing held fully accountable for the harms caused by its federal conspiracy crime of defrauding the FAA about the safety of the 737 MAX. Last Friday, I argued before Judge Reed O'Connor (N.D. Texas) that he should reject the proposed plea agreement negotiated between Boeing and the Justice Department. Among other arguments, I explained that the proposed plea deal would improperly transform Boeing's conspiracy into a "victimless" crime rather than recognize the 346 deaths Boeing directly and proximately caused through its lies. This post summarizes a few of my arguments against the deal, along with linking to the main filings from both sides in the case–and the oral argument transcript–so that readers can see the competing positions. This post also includes an order from Judge O'Connor, issued yesterday, that directs DOJ and Boeing to provided additional briefing on a DEI provision in the proposed plea.

Some quick background to set the stage: In 2018 and 2019, two brand-new Boeing 737 MAX aircraft crashed in Indonesia and then Ethiopia, killing 346 passengers and crew. The Justice Department opened a criminal investigation into Boeing and soon developed compelling evidence that Boeing had defrauded by the FAA by concealing the capabilities of one of the plane's new software programs.

Faced with the Government's compelling evidence, in late 2020 and early 2021, Boeing secretly negotiated a lenient deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) with the Justice Department. The parties then filed the DPA with Judge O'Connor in the Northern District of Texas. Receiving no immediate objection to the DPA, Judge O'Connor allowed the agreement to move forward.

In December 2021, I filed an objection to the deal. I argued that the Justice Department had violated the rights of the families of the victims killed in the two crashes. In secretly negotiating the deal, DOJ violated the families right under the Crime Victims' Rights Act to confer with the prosecutors during the DPA negotiations. DOJ (and Boeing) responded that the families did not represent "crime victims," because the connection between Boeing's conspiracy crime and the crashes was too attenuated. But after two days of evidentiary hearings, in October 2022, Judge O'Connor disagreed—finding that the families represented "crime victims" and that the Justice Department had violated the families' CVRA rights to confer about the deal.

But ultimately, after a further hearing, in January 2023, Judge O'Connor ruled that while he had "immense sympathy for the victims and the loves ones of those who died in the tragic plane crashes resulting from Boeing's criminal conspiracy," he was unable to award them any remedy. I sought review in the Fifth Circuit. Last December, the Circuit concluded that, if a properly presented issue came before Judge O'Connor, he did have the power to take victims' rights into account in deciding how best to proceed.

Since then, in the wake of the Alaskan Air 737 doorplug blowout, in April the Justice Department concluded that Boeing breached its safety and compliance obligations under the DPA. Following that breach determination—which ended the deferral of prosecution provided by the DPA—in July Boeing and DOJ announced that they had reached a plea agreement to resolve the pending conspiracy charge.

When the parties unveiled the terms of their plea deal, the families were outraged. Previously I blogged about the families' objections to the plea and their motion to Judge O'Connor asking him to exercise his discretion to reject it. Both the Justice Department and Boeing have filed responses.

Here is an excerpt from the Justice Department's response, essentially arguing that this plea deal is the best they could do:

In the Government's judgment, the Agreement is fair and just, as well as a strong resolution of this matter that serves the public interest. And ultimately, the Government's decision to enter into this Agreement is dictated by what it can prove in court and what it cannot. The Government can prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Boeing defrauded the FAA, and that this fraud caused a gain of $243.6 million. For that conduct, the Government has secured the best criminal resolution possible. Yet despite exhaustive investigation—both prior to the 2021 DPA and more recently—the Government cannot prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Boeing's fraud directly and proximately caused the 737 MAX plane crashes, and it cannot prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the loss (or gain) arising from Boeing's fraudulent activity exceeded $243.6 million. Guided by the law, the evidence, and the Department's Principles of Federal Prosecution, the Government has obtained a resolution that sets out the facts it could prove at trial and carries a proposed sentence that satisfies each of the factors this Court must consider under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a).

I filed a reply for the families. One of the main points is that Boeing got special treatment through a "C-plea" (that is, a plea agreement under Fed. R. Crim. P. 11(c)(1)(C).) Under a C-plea, if the judge approves the deal, then he is required to impose the sentence that the parties stipulate. As the argument is commonly phrased, the judge's "hands are tied" once he approves the C-plea.

The C-plea that the Justice Department and Boeing have presented to Judge O'Connor relies on a sentencing guidelines calculation that essentially assumes Boeing's crime caused no harm to anyone. But Judge O'Connor has already ruled that Boeing's crime killed 346 people, making the crime (by some measures) the "deadliest corporate crime in U.S. history."

The parties attempt to make the deaths vanish by arguing that Boeing must be sentenced based solely on facts that can be proven beyond a reasonable doubt. But at sentencing, under long-settled law, a defendant is conventionally held accountable for all harms that can be proven by a preponderance of the evidence. The introduction to my reply brief focuses on the Department's incorrect burden of proof:

The parties create a distorted record by misleadingly conflating the demanding proof-beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard used in jury trials with the lower proof-by-a-preponderance-of-the-evidence standard applicable in sentencing proceedings. Under this lesser standard—which controls here—criminal defendants are responsible for all of their "relevant conduct," including all losses caused by their crimes. In this case, the Court has already found that Boeing's lies directly killed 346 people. For the parties, this is the truth that dare not speak its name. But faithfully determining the factual record on which to base Boeing's sentence requires considering these deaths. And with the deaths properly in mind, a host of features in the proposed plea agreement are revealed to be inadequate, such as its misleading guidelines calculations, paltry fine, non-transparent corporate monitor, insufficient remedial measures, and uncertain restitution awards. For all these reasons, the Court should reject the proposed plea.

To consider the competing positions, Judge O'Connor held a hearing last Friday. A transcript of the two-hour argument is found here. The Justice Department argued that the plea was the best they could do:

This plea agreement is a strong and in-the-public-interest resolution. The plea agreement convicts Boeing of the felony crime it is charged with and compels the company to pay the maximum legal fine, the most the government could achieve if this case went to trial and Boeing were convicted. It ensures that the Court can order Boeing to pay all lawful restitution to the families of the crash victims, the same as if Boeing were convicted at trial. It requires Boeing to continue to improve its compliance and ethics program, to better integrate that with its safety and quality, while respecting the jurisdiction of the FAA in that space and to have a monitor to oversee the improvements to compliance and ethics and to back up these efforts with an investment of almost half a billion dollars.

Were this case to go to trial, there's no guarantee that the Court could or would impose these conditions or similar ones, but this agreement guarantees them.

The government acknowledges the deep disagreement that the families have with the plea agreement, though we endeavor[ed] through our conferrals to incorporate their voices and their views as much as was appropriate and feasible in the document.

Boeing agreed with the Government and argued that a "C" plea (a binding plea) was required to provide certainty to the outcome of the case:

[A]s the Court may know, the Boeing Company is a pillar of the American economy and a pillar of the national defense. The Boeing Company employs 170,000, approximately, people. And it is not subdivided. In other words, the Boeing defense business is within the same company as Boeing commercial airplanes and Boeing global supply. It's all within one business that provides commercial airplanes, but also defense platforms.

And so, as the Court already said and knows and any guilty plea resulting in a felony offense, obviously, the DOD relevant personnel would review that. But it certainly has, under the federal regulations, debarment consequences. And that will be for the DOD programs to decide.

But what the "C" plea advances and accomplishes here is setting forth the record, if the Court accepts it, that those officials would have and can proceed to make their decisions on that record. I would submit that's important, not just for Boeing, but for the national defense, because it will enable to them to proceed with their decisions.

I argued for the families that the plea deal was "rotten" because it concealed the truth that Boeing's lies killed people:

Let me go straight to the heart of the matter, which is that the parties are swallowing the gun in this case–that is, they are concealing, through legal maneuvering, … the truth of the case.

Now, it's a well-established principle that in sentencing the Justice Department is supposed to provide the Court all relevant facts, but they failed to do that here. … I know that I'm making a strong assertion there and sometimes attorneys come in and make assertions that they can't back up—but see, right here on the table is our 44-page Statement of Facts with redlining for the convenience of Your Honor and for the parties, showing exactly the facts that the Justice Department and Boeing are leaving out. And those are facts that go directly to the culpability of this company for the deadliest corporate crime in U.S. history.

And indeed, let's talk specifically about the deaths. Your Honor has already found that Boeing's crime directly and proximately caused the deaths of 346 people, making it the deadliest corporate crime in U.S. history. You would think that that fact would somewhere show up in the plea agreement that the parties are asking you to bless, but it doesn't. That is the fundamental reason why the families are here today asking you to reject this plea. It would be one thing if the parties said, 346 people died and now let's discuss with Judge O'Connor what the appropriate response is in terms of a criminal sentence. But they want you to go to sentencing in this case as though 346 people did not die.

At the end of the Friday hearing, Judge O'Connor promised a ruling quickly. And then, the next business day (yesterday, October 15), Judge O'Connor ordered the Justice Department and Boeing to file additional briefing on a DEI provision in the proposed plea related to the selection of a corporate monitor for Boeing. Judge O'Connor explained (footnotes omitted):

The Government has confirmed Boeing's fraudulent misconduct has burdened safety and compliance protocols. Accordingly, the corporate monitor's role centers precisely on Boeing's "current and ongoing compliance with U.S. fraud laws," specifically focusing "on the integration of [Boeing's] compliance program with [Boeing's] safety and quality programs as necessary to detect and deter violations of anti-fraud laws or policies."

Given this, the Court needs additional information to adequately consider whether the Agreement should be accepted. Specifically, it is important to know: how the provision promotes safety and compliance efforts as a result of Boeing's fraudulent misconduct; what role Boeing's internal focus on DEI impacts its compliance and ethics obligations; how the provision will be used by the Government to process applications from proposed monitors; and how Boeing will use the provision and its own internal DEI commitment to exercise its right to strike a monitor applicant. Accordingly, the parties should address the following:

• The Government SHALL provide the Court with the specific DOJ policy it referenced during the October 11 hearing and in the Agreement; definitions for the terms "diversity" and "inclusion" as stated in the Agreement; supplemental briefing explaining how the provision furthers compliance and ethics efforts; and how it will use the provision in selecting a proposed monitor.

• Boeing SHALL provide supplemental briefing explaining what it understands the provision to require; an explanation of how its existing DEI policies are used in its current compliance and ethics efforts; and how it intends to use DEI principles in exercising its strike of a proposed independent monitor.

Judge O'Connor directed the parties to file their briefs on the DEI issues by October 25. A ruling on whether he will accept or reject the plea will likely follow soon thereafter.

Note: I have been joined in representing the families by (among other excellent lawyers) Bob Clifford and Tracy Brammeier at Clifford Law Offices, Erin Applebaum at Kreindler & Kreindler, Pablo Rojas at Podhurst Orseck, and Warren Burns and Darren Nicholson at Burns Charest (very capable local counsel in Dallas).

The post Should the Boeing Plea Deal on the 737 MAX Crashes Be Approved? appeared first on Reason.com.

October 15, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] No Civil Court Claim Over Publicizing Religious Court's Statement That Litigant Refuses to Appear in the Religious Court

From today's decision by Judge Rachel Kovner (E.D.N.Y.) in Esses v. Rosen:

Plaintiff Regina Esses has moved for a preliminary injunction under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65 against defendants Tanya Rosen and Tanya Rosen Inc. enjoining defendants from disseminating a declaration from a rabbinical court and an accompanying instructional document. Plaintiff's motion for a preliminary injunction is denied….

The following facts are taken from plaintiff's filings in support of her motion for a preliminary injunction and are assumed true for purposes of this motion.

Both plaintiff and defendant Tanya Rosen are members of the Orthodox Jewish community. As relevant to plaintiff's request for a preliminary injunction, plaintiff asserts that, before she filed this lawsuit, Rosen secured the issuance of a summons against plaintiff by a Jewish rabbinical court, or beth din, called Badatz Mishpitei Yisroel ("BMY"), regarding plaintiff's former employment contract with defendant Tanya Rosen Inc. According to plaintiff, "[u]nder Jewish law, when an individual is summoned to beth din, the recipient has the right to propose an alternative beth din to avoid potential bias or undue influence from the summoner's chosen venue." Plaintiff alleges that "BMY, at Rosen's request, continued to issue summonses demanding [plaintiff's] appearance," even though plaintiff proposed an alternative rabbinical court in New Jersey.

Plaintiff asserts that Rosen later "sought a seiruv from BMY against" plaintiff. According to plaintiff, a "seiruv is a public declaration issued by beth din that a person has refused to comply with rabbinic court orders to appear." The seiruv lists plaintiff's home address and states:

Whereas, close to a year has passed since we have sent out our first summons to [plaintiff] and until this day a Din torah has not been scheduled, we have no choice but to declare [plaintiff] a Mesareves, in addition to her filing in court against [Rosen] without permission from a Bais Din. She claims to have permission from her Rabbi, which she has not substantiated to the Beis Din. Anyone that may impress upon her the severity of the grave sin of refraining from appearing in Beis Din shall do so and it will be to his merit.

Rosen distributed the seiruv, along with an "instructional document" purporting to describe what a seiruv generally entails, "throughout [plaintiff's] neighborhood," in various "Jewish community Whatsapp group chats," and to Rosen's listserv, which contains thousands of recipients. The instructional document describes a seiruv as "a form of contempt order issued by a rabbinical court." It states that the "public declaration serves as a form of social pressure, calling on the community to shun or ostracize the individual until they comply with the court's demands."

It adds that "the treatment of someone with a [seiruv] can vary depending on the community's customs," but that, generally, "[t]he community may avoid social interaction with the individual, including not inviting them to communal events, not including them or their spouse in a minyan (quorum for prayer), and refraining from doing business with them." In addition, "[t]he community may be informed of the [seiruv], and the person's refusal to comply with the court's ruling is to be publicized." Plaintiff claims that Rosen's dissemination of the seiruv has caused her "significant emotional distress" and fear, amplified by plaintiff's pregnancy and a recent "armed break-in at [plaintiff's] home" by unknown persons. Plaintiff also claims that she has "lost a client who terminated their business relationship upon becoming aware of the seiruv." …

Plaintiff's operative amended complaint alleges a wide-ranging "campaign of harassment" by Rosen against plaintiff, beginning after plaintiff left defendants' employment in October 2022. For example, plaintiff alleges that Rosen arranged a box containing feces to be sent to plaintiff's home, sent harassing text messages to plaintiff's husband, and created an Instagram account under plaintiff's name that Rosen used to write posts designed to portray plaintiff in a negative light….

Those arguments aren't being resolved in this decision, but the decision does discuss plaintiff's request for a preliminary injunction, "focus[ed] solely on defendants' distribution of the seiruv":

Specifically, plaintiff moves for a preliminary injunction "restraining the Defendants from further disseminating the notice of seiruv … or any similar documents … that contain the plaintiff's home address or false claims regarding the plaintiff's failure to appear at a Beth Din." Plaintiff also requests that the Court order defendants "to take down or request the removal of any existing copies of the Seiruv or similar materials from any platforms where it has been disseminated."

The court said plaintiff hadn't established "a likelihood of success or serious questions going to the merits of her supplemental defamation claim":

The First Amendment limits courts' ability to adjudicate some defamation claims involving religion. The Establishment Clause bars state actors from deciding disputes of religious doctrine or practice. Federal courts therefore consistently refuse to adjudicate defamation claims that would require them to decide questions of religious law…. [Plaintiff's] declaration, even if fully credited, does not establish that the statements in the seiruv or accompanying document are actionable as substantially false statements. Plaintiff offers four theories to establish this element, but none withstand scrutiny.

Plaintiff first asserts that the seiruv defames her because it "states that Plaintiff improperly initiated this matter in court in lieu of bringing it to beth din." While plaintiff does not dispute that she brought the claims in this case before a secular court rather than a religious one, she suggests that the seiruv is defamatory because it indicates that her doing so was "improper[]." That statement is nowhere contained in the seiruv itself. But even if the seiruv is read to convey that implication through its reference to plaintiff's civil filing, the First Amendment would prevent this Court from second-guessing a religious court's view of impropriety. Any implication of impropriety in the order of the beth din is "plainly made in the context of the Orthodox Jewish faith." Plaintiff's claim thus invites the Court to determine whether a rabbinical court properly applied religious principles in disapproving of plaintiff's conduct—the type of "judicial intrusion into ecclesiastical doctrine and practice" that "is unquestionably forbidden ground under the First Amendment.

Plaintiff next suggests that the seiruv is defamatory because it states that plaintiff "has not 'substantiated'" to BMY that she received permission from her rabbi "to forego beth din proceedings." But plaintiff has not shown serious questions going to the merits of a claim based on this statement because she does not contend that she did provide substantiation of rabbinical permission to the beth din. While plaintiff suggests that the seiruv "falsely implies the beth din requested substantiation from Plaintiff," she has not made the requisite "rigorous showing," that this inference is supported by the seiruv, which simply states that plaintiff "has not substantiated" her "claim[] to have permission from her Rabbi" not to appear.

Plaintiff next claims that the instructional document distributed with the seiruv is defamatory because it falsely conveys "that the rabbis of the beth din were encouraging social ostracism and shaming in this case." Again, such a statement appears nowhere on the face of the instructional document, which makes no reference to BMY or the specific seiruv BMY issued regarding plaintiff. It instead appears to describe what the issuance of a seiruv generally entails. In any event, the Establishment Clause would preclude this Court from finding defamation on that ground. To decide whether the instructional document was true or false in its asserted characterization of plaintiff's seiruv, the Court would be "called upon to inquire into the rules and customs governing rabbinical courts as they are utilized in the Orthodox Jewish religion" to determine whether a seiruv should be understood to encourage social ostracism or shaming, and then to give an authoritative construction to a religious court's declaration in light of those religious rules and customs. Again, this is the type of intrusion into religious practice that the First Amendment prohibits.

Finally, plaintiff claims that "the seiruv in its entirety" is defamatory because it "was procured under false pretenses" by Rosen. Specifically, plaintiff alleges that Rosen "procur[ed] the seiruv … to falsely and disingenuously defame" plaintiff, as suggested by the fact that Rosen's "behavior in this forum directly contradicts her claim to the beth din that she wishes to pursue arbitration." But plaintiff cannot establish a defamation claim based on asserted bad motives, unaccompanied by evidence of falsity, because defamation requires falsity.

And the court likewise concluded that plaintiff hadn't established "a likelihood of success or serious questions going to the merits" of her intentional infliction of emotional distress claim:

Under New York law, an IIED claim requires the plaintiff to establish "four elements: (1) extreme and outrageous conduct, (2) intent to cause severe emotional distress, (3) a causal connection between the conduct and the injury, and (4) severe emotional distress." The defendant's conduct must be "so outrageous in character, and so extreme in degree, as to go beyond all possible bounds of decency, and to be regarded as atrocious, and utterly intolerable in a civilized community." The "extreme and outrageous conduct" standard is "rigorous[] and difficult to satisfy." …

Plaintiff's motion seeking a preliminary injunction based on IIED does so exclusively based on "[t]he dissemination of the seiruv," which she argues "cannot be classified as anything other than a malicious campaign of harassment and intimidation." But as explained above, plaintiff has not plausibly alleged any inaccuracy in the seiruv or accompanying flier that is within the competence of this Court to adjudicate.

Plaintiff cannot meet her burden of establishing "extreme and outrageous conduct" that "go[es] beyond all possible bounds of decency" and is "utterly intolerable in a civilized community" based merely on dissemination of true statements. And because plaintiff cannot invite the Court to intrude on questions of religious law in the context of an IIED claim any more than in the context of a defamation claim, plaintiff cannot base an IIED claim on the theory that the seiruv erred in treating plaintiff's conduct as improper or that the informational document misstates the implications of the seiruv under Jewish law….

Brandon David Okano (Leeds Brown Law) and Rick Ostrove represent defendants.

The post No Civil Court Claim Over Publicizing Religious Court's Statement That Litigant Refuses to Appear in the Religious Court appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Colorado Elected District Attorney Disbarred for Litigation Misconduct

From People v. Stanley, decided Sept. 10 by the Office of Presiding Disciplinary Judge of the Supreme Court of Colorado but just posted to Westlaw; the opinion is by Presiding Disciplinary Judge Bryon M. Large, joined in part by Member Sherry A. Caloia (a lawyer) and in part by Member Melinda M. Harper (a citizen member):

Following the highly publicized disappearance of a Chaffee County woman [Suzanne Morphew], Stanley, who was the newly elected District Attorney of Colorado's 11th Judicial District, brought first-degree murder charges against the woman's spouse [Barry Morphew]. During the prosecution, Stanley made three improper extrajudicial statements about the case to the media, which threatened to prejudice the defendant and undermine the public's interest in justice. Those statements contributed in part to a judicial ruling changing venue in the case. Through this misconduct, Stanley violated Colo. RPC 3.6(a) (a lawyer who participates in the investigation or litigation of a matter must not make an extrajudicial statement that the lawyer knows or reasonably should know will be disseminated by means of public communication and will have a substantial likelihood of materially prejudicing an adjudicative proceeding) and Colo. RPC 3.8(f) (prosecutors must refrain from making extrajudicial comments that have a substantial likelihood of heightening public condemnation of the accused unless the comments serve a legitimate law enforcement purpose, are necessary to inform the public of the nature and extent of the prosecutor's action, or are permitted under Colo. RPC 3.6(b)).

At the same time, Stanley did not adequately supervise the prosecution of the case. She failed to timely direct adequate administrative resources to process discovery, leading to a series of judicially imposed sanctions against the prosecution for discovery violations. She failed to take reasonable measures to establish a leadership structure that ensured accountability within the prosecution team, with the result that the prosecution team overlooked important projects in the case. And she failed to intervene when the prosecution team was given an opportunity to cure its deficient endorsements for expert witnesses, the majority of whom were eventually excluded. Through this conduct, Stanley violated Colo. RPC 5.1(b) (a lawyer with direct supervisory authority over another lawyer must make reasonable efforts to ensure that the other lawyer conforms to the Rules of Professional Conduct).

After the presiding judge [Ramsey Lama] issued several adverse rulings less than two months before jury selection, Stanley instructed her chief investigator to interview the judge's former spouse to determine whether the judge committed domestic abuse. Even though she had no credible evidence to believe that the judge had ever engaged in such criminal conduct, Stanley ordered the investigation in an effort to uncover information about the judge that would require him to recuse from the case. Shortly after the interview, which revealed that the judge had never abused his former spouse, Stanley dismissed the case without prejudice. Though this conduct, Stanley attempted to violate Colo. RPC 8.4(d) (it is professional misconduct for a lawyer to engage in conduct prejudicial to the administration of justice), thereby contravening Colo. RPC 8.4(a) (it is professional misconduct for a lawyer to attempt to violate the Rules of Professional Conduct).

In a bid to rehabilitate her relationship with the media, Stanley later agreed to sit for a videotaped interview with a local reporter. During that interview, which Stanley reasonably should have known was on the record and would be publicly disseminated, she again made improper extrajudicial statements about two defendants criminally charged in the death of a ten-month-old baby.

She effectively pronounced that one of the defendants was guilty, revealed inadmissible details about the defendant's sexually based juvenile offenses, and impugned the motives and character of the defendants. Two judicial officers, ruling independently, concluded that Stanley's extrajudicial statements amounted to outrageous government conduct so severely prejudicing the defendants that the judiciary was required to dismiss each defendant's criminal case. Through this conduct, Stanley violated Colo. RPC 3.6(a) and Colo. RPC 3.8(f)….

In their opening statement, the People likened Respondent's handling of the Morphew prosecution to that of a ship's captain who never appeared on the bridge. In some ways, this analogy is apt. Respondent's absence at the helm during key phases of the prosecution—even when she was warned that it faced rough waters—led to a series of events that ended with the first-degree murder case running aground.

The analogy captures Respondent's dereliction of her duty as an elected official and the top prosecutor in her district. In that role, her obligation was not to win or to protect her reputation but to see justice done. Instead, her unjustifiable extrajudicial statements in the Jacobs and Crawford cases led to the opposite result, prejudicing each criminal defendant and torpedoing the criminal cases against them. And her baseless decision to launch an in-house investigation of a judge presiding over a case that was close to trial prejudiced the administration of justice and abused her position of trust. She must be disbarred.

This is just the introduction and the conclusion; the full opinion goes into much more detail. Member Caloia dissented in part:

I would be remiss if I did not set forth the particularities of practicing criminal law in a small rural jurisdiction and the accepted practices of criminal lawyers and district attorneys. The problems that exist with respect to providing discovery to defendants in a criminal case in Colorado are many and widespread. The practice of responding to motions and filing expert witness reports varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and judge to judge. I am concerned that the Morphew case has undergone an extensive amount of Monday-morning quarterbacking. Practices common to a civil arena are not always common to a criminal case. There are various accepted practices and discovery issues that are particular to criminal law that need to be considered….

I also dissent as to the majority's finding as to [the interview of Judge Lama's wife]…. Here, the majority concludes the People have not proved that Respondent's decision to interview Iris Lama either prejudiced or attempted to prejudice the administration of justice. Respondent's decision to seek an interview with Iris Lama had some grounding—most specifically, Judge Lama's decision to exclude evidence of domestic violence in the Morphew case. That, coupled with Iris Lama's position with the Alliance Against Domestic Abuse and her public advocacy for missing people, including Suzanne Morphew, was sufficient to justify exercise of Respondent's sweeping discretion to look into the change.org petition's allegations.

I am even more influenced by the manner in which Respondent chose to inquire into potential judicial bias. Though best practices would dictate that an outside agency conduct the interview, Respondent did solicit help from the Chaffee County Sheriff and the CBI; both agencies declined to participate. After settling on Corey to interview Iris Lama, Respondent took reasonable steps to ensure that the interview was both voluntary and entirely confidential. Corey met on Iris Lama's terms, wore civilian clothes, and conducted the interview in a conversational, low-pressure way. The prosecution took no further investigative action. As I see it, the interview was something short of a criminal investigation and did not clearly evince an attempt to prejudice the administration of justice. Further, because Respondent did not make public the allegations or the fact of the interview, I assess the risk as rather low that the interview took on the appearance of harassment, intimidation, or retaliation. Ultimately, the case was dismissed shortly after the interview, so no prejudice to the justice system accrued.

I conclude that Respondent's decision to interview Iris Lama was within the bounds of Respondent's prosecutorial discretion. In making this determination, I am particularly mindful that an opposite conclusion could send the message that prosecutors are prohibited from merely asking citizens questions about intimations of wrongdoing. Had Respondent gone further—if, for example, she had made Judge Lama aware of the interview, approached him for an interview, taken other additional actions, or more conspicuously invoked the authority of her office—I would find differently. But under these specific circumstances, I cannot conclude the People have proved that Respondent prejudiced or attempted to prejudice the administration of justice….

Finally, I dissent as to the appropriate sanction in this case. I believe that Respondent should not be disbarred but instead should be suspended for a period of two and a half years, with the requirement that before she returns to the practice of law she must prove she can practice law in conformity with the Rules of Professional Conduct….

Member Harper dissented in part as to a different matter: She would have also found that DA Stanley had "failed to exercise reasonable diligence in prosecuting the Morphew case." Judge Large's opinion was thus a majority opining for the panel, though different members joined different parts.

The majority opinion also discusses DA Stanley's background; had her behavior in these cases been different, her personal might have been inspiring:

Respondent grew up in Davenport, Iowa. After receiving an associate's degree in criminal justice, she moved to Colorado in 1989 and worked as a truck driver. In 1993, she obtained a bachelor's degree at Metro State University in criminal justice. Later, she served as a police officer for several years, first in Arvada and then in Blackhawk. Before starting her family, Respondent returned to driving semis, which paid more and which she adjudged was less dangerous. She had two boys, who are now grown. Eventually, she attended the University of Denver master's degree program in public administration with an emphasis in domestic violence prevention, an issue personal to her, having been a victim of domestic violence. In autumn 2006 she enrolled at University of Denver law school in the part-time evening program, with the goal of working as a prosecutor. She graduated from law school in May 2010.

Respondent was admitted to practice law in Colorado in 2012. She has worked as prosecutor for most of her legal career in municipal, county, and district courts. In 2017, she briefly worked in private practice before accepting employment as a hearing officer for the Colorado Department of Revenue. She left that position in January 2020 to campaign for the position of district attorney …. She testified that she ran in part on a platform of prioritizing cold cases. She won the election ….

The post Colorado Elected District Attorney Disbarred for Litigation Misconduct appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Journal of Free Speech Law: "The Future of Free Speech: Curiosity Culture," by Olivia Eve Gross

The article is here; the Introduction:

Before entering college in 2020, I thought cancel culture existed solely in the domain of celebrities, newsmakers, social media, consumer brands, and large corporations. I first became aware of the phenomenon in its original context: a TV show was canceled in response to a backlash after its star committed an abhorrent act. In another case, a product-endorsement contract was canceled ahead of public outcry over the spokesperson's reported behavior. As these scenarios grew more common, I assumed cancellations only took place in the realm of the famous.

At the start of my first year at the University of Chicago, I learned that cancel culture had infiltrated campus life. Students were being shunned for voicing an unpopular view in class, excoriated on social media over a pun, or shamed for asking a question because they were of the "wrong" identity for the subject matter. My campus wasn't unique—if anything, Chicago does more than almost any other university to advocate and defend principles of free speech.

This revelation was as bewildering as it was upsetting. The fundamental mission of a liberal-arts education is to promote diverse perspectives, thoughtful debate, intellectual growth, and, hopefully, classmate camaraderie in the shared experience of it all. And my university does a lot to support this objective. But students themselves are now stifling the university experience by using a variety of methods to either silence speech or ensure that certain speech receives social punishment. Such trends have detrimental consequences for the campus community at-large, eroding the university's formative environment of speech. In polling conducted by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, more than half of students (56 percent) expressed worry about damaging their reputation because of someone misunderstanding what they have said or done.

The post Journal of Free Speech Law: "The Future of Free Speech: Curiosity Culture," by Olivia Eve Gross appeared first on Reason.com.

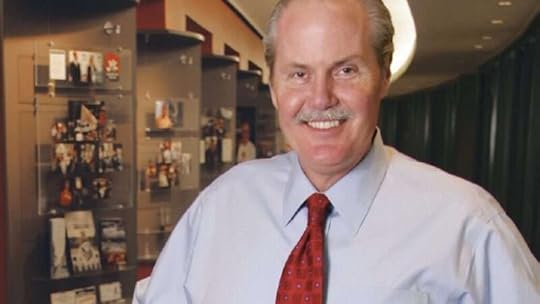

[Ilya Somin] William "Chip" Mellor, RIP

William "Chip" Mellor. (Institute for Justice)

William "Chip" Mellor. (Institute for Justice)

William "Chip" Mellor, visionary cofounder and longtime president of the Institute for Justice—a leading public interest law firm focused on economic liberty, property rights, and free speech—passed away on October 11. Here is an excerpt from the obituary posted on the IJ website, written by John Kramer:

On Friday, October 11, America lost one of the most significant civil liberties pioneers of the past 40 years: William "Chip" Mellor—the founding president and recent board chairman of the Institute for Justice, a national, public interest law firm—died at his home in Moab, Utah, after a battle with leukemia.

Mellor's philosophically and tactically consistent approach to protecting the rights of ordinary Americans—especially those of modest means—led him to cofound the Institute for Justice in 1991 with Clint Bolick. He created IJ to protect private property and free speech, to challenge arbitrary government regulations that interfere with economic liberty, and to expand educational choice for those stuck in failing public schools. In the process, he and IJ reshaped America's legal landscape and how public interest cases are litigated in the courts of law and in the court of public opinion.

"Chip demonstrated remarkable vision and a knack for public interest litigation throughout his life," said Scott Bullock, who worked with Mellor for 25 years and in 2016 succeeded him as IJ's president. "He brought together cutting-edge legal advocacy, media relations, grassroots activism, legislative work, and strategic research in a pioneering and innovative way. He made the Institute for Justice a powerhouse for the protection of constitutional rights."

Thanks to Mellor's vision and the advocates he hired and inspired, IJ has won many pathbreaking constitutional cases that have set the standard for legal change. Mellor understood that principled change takes time, so he established IJ to engage in long-term, strategic public interest litigation rather than react to current controversies or issues of the week. He fostered an entrepreneurial, happy warrior culture within IJ, where many make their careers to change the world for the better.

As a law student, I served as a law clerk at IJ during the summer of 1998, at which time I got to know Chip. His leadership was incredibly impressive. In large part thanks to his efforts, IJ litigated and won numerous precedent-setting cases. Few could match his skill at combining strategic litigation with effective campaigns in the court of public opinion.

The time I spent at IJ helped generate an abiding interest in constitutional property rights that has been a major part of my work ever since. The institution Chip played a key role in creating had a similar impact on many other future lawyers and academics.

Chip will be greatly missed. I extend my condolences to his colleagues, family, and friends.

The post William "Chip" Mellor, RIP appeared first on Reason.com.

[Thomas Lee and Jesse Egbert] Corpus Linguistics, LLM AIs, and the Future of Ordinary Meaning

Modern textualism is built on at least three central pillars. Textualists credit the ordinary meaning of the language of law because such meaning: (1) can reasonably be discerned by determinate, transparent methods; (2) is fairly attributable to the public who is governed by it; and (3) is expected to constrain judges from crediting their own views on matters of legislative policy.

To fulfill these goals, textualist judges expected to show their work—to cite reliable evidence to support their conclusions on how legal words or phrases are commonly used by the public. Judicial intuition is a starting point. But judges who ask the parties and public to take their subjective word for it are not engaged in transparent textual analysis; cannot reliably be viewed as protecting public reliance interests; and may (at least subconsciously) be advancing their own views on legislative policy.

The Snell concurrence acknowledges these concerns (as do the academic pieces it relies on). But the tools it advances (AI LLMs) fall short of fulfilling these key premises. Corpus linguistic tools, by contrast, are up to the task.

We show how in our draft article. In Part III we investigate the empirical questions in Snell through the tools of corpus linguistics. We performed transparent searches aimed at assessing (a) how the term "landscaping" is commonly used in public language; and (b) whether people commonly use the term "landscaping" when they speak of the installation of in-ground trampolines. Our results are granular and nuanced. They stand in contrast to the conclusory assertions of AI chatbots—conclusions that gloss over legal questions about the meaning of "ordinary meaning" and make it impossible for a judge to lay claim to any sort of transparent, determinate inquiry into the ordinary meaning of the language of law.

Our first search was aimed at uncovering empirical evidence on the conceptual meaning of "landscaping"—whether and to what extent this term is limited to improvements that are botanical and aesthetic or instead encompasses non-botanical, functional improvements. We sought empirical data on that question by searching for all uses of the term "landscaping" in the Corpus of Contemporary American English. Our search yielded 2,070 "hits" or passages of text containing the term. We developed and applied a transparent framework for "coding" a random sample of 1,000 of those hits (as detailed in Part III.A of our article). And we found that "landscaping" (a) is sometimes used to encompass improvements of a non-botanical nature (in about 20% of the passages of text we coded), and (b) and is regularly used to extend to improvements for a functional purpose (in about 64% of codable texts).

Our second search considered the ordinary meaning question from the standpoint of the "referent" or application at issue in Snell. It asked whether and to what extent "landscaping" is the term that is ordinarily used to refer to installation of an in-ground trampoline. Here we searched the 14 billion word iWeb corpus for references to "in-ground trampoline," "ground-level trampoline," "sunken trampoline," and more (as detailed in Part III.B. of our article). And we found that "landscaping" is a common term—if not the most common term—used to describe the type of work involved in the installation of an in-ground trampoline. Our dataset was small. But of the texts where a category word was used that could be viewed as arguably competing with "landscaping," we found that in-ground trampoline work was described as "installation" (62%), "landscaping" (33%), and "construction" (5%).

The datapoints are a bit messy (but such is American English). And the takeaway will depend on a judge's views on jurisprudential questions lurking beneath the surface—among other things, on how common a given meaning must be to fall within "ordinary meaning."

There is no settled view on the matter. Some courts deem a meaning "ordinary" only if it is the most common meaning of the term (or perhaps a prototypical application). Others treat a meaning as "ordinary" if it is less common but still attested. (See Part I.A of this article).

A judge who views "ordinary meaning" as limited to the most common sense or prototypical application of a given term might come down against insurance coverage—noting that 80% of the uses of "landscaping" refer to botanical improvements and observing in-ground trampoline work is predominantly (63%) referred to as "installation."

A judge who views "ordinary meaning" to extend to less common (but attested) senses might come down the other way—contending that the 20% rate of "landscaping" reference to non-botanical use is still substantial, as is the 33% use of "landscaping" to refer to in-ground trampoline work (particularly where "installation" may not be considered to compete with "landscaping" since installation work can be done by landscapers).

LLM AIs provide none of this authentic nuance or granular detail. They just give bottom-line conclusions and AI gloss.

In Snell, the queries themselves didn't ask for the "datapoints" or "probabilistic[] maps" that Judge Newsom said he was looking for. They asked for bare conclusions about "the ordinary meaning of 'landscaping'" and whether "installing an in-ground trampoline" "is landscaping." The chatbots responded accordingly. They said that "landscaping" "can" be used to encompass "trees, shrubs, flowers, or grass as well as … paths, fences, water features, and other elements," and stated that installation of an in-ground trampoline "can be considered a part of landscaping" but it is "a matter of opinion" depending on "how you define the term."

These aren't datapoints. And the chatbots won't provide them if asked. In Part I.B.1 of our article we show what happens if you push back on the chatbot. It will openly concede that it "can't generate empirical evidence," explaining that this would have to be "based on new observations or experiments"—"something I can't do directly."

This is a fatal flaw. The premises of textualism require more than a chatbot's bare conclusions about how "landscaping" "can" be used or on whether in-ground trampoline work "can" be considered to fall within it.

The chatbot's conclusions gloss over underlying questions of legal theory—on how common or prototypical a given application must be to count as "ordinary." And in the absence of underlying data, a judge who credits the "views" of the AI is not engaged in a transparent analysis of ordinary meaning, may not be protecting the reliance interests of the public, and may be (even subconsciously) giving voice to his own views on matters of public policy.

This is just one of several grounds on which existing LLM AIs fall short where corpus tools deliver. Our draft article develops others. We will present a couple more of them in upcoming blog posts. And on Friday we will outline some potential advantages of AIs and make some proposals for a future in which we could leverage AI to augment corpus linguistic methods while minimizing the risks inherent in existing LLM AIs.

The post Corpus Linguistics, LLM AIs, and the Future of Ordinary Meaning appeared first on Reason.com.

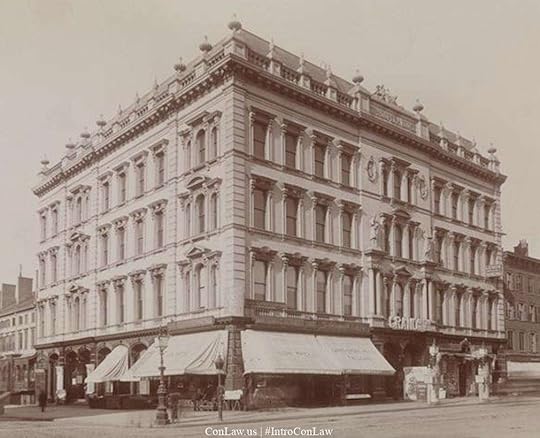

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 15, 1883

10/15/1883: The Civil Rights Cases are decided.

The Grand Opera House in New York denied "another person, whose color is not stated, the full enjoyment of the accommodations."

The Grand Opera House in New York denied "another person, whose color is not stated, the full enjoyment of the accommodations."The post Today in Supreme Court History: October 15, 1883 appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers