Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 250

October 8, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Tuesday Media Recommendations: Nonfiction History Books

The post Tuesday Media Recommendations: Nonfiction History Books appeared first on Reason.com.

[Samuel Bray] Today's Argument in Lackey v. Stinnie: Attorneys' Fees and Preliminary Injunctions

This morning the Supreme Court will hear argument in Lackey v. Stinnie, a major case about attorneys's fees and preliminary injunctions. The case has so far escaped much attention in the press, but its implications are important. These include implications for litigation funding, for incentives to settle after a preliminary injunction, and for how the preliminary injunction operates in the federal courts.

The preliminary injunction is designed to protect the Court's ultimate remedial options (as explored at length in The Purpose of the Preliminary Injunction). It is an interim measure that does not determine the merits, and instead, to use a felicitous phrase of Professor Bert Huang, it "sets a holding pattern." But there has been a major shift in the federal courts toward merits-dominated decisionmaking. It has become a central front in many of the most important public law cases. It is not designed for that role, and the error costs at the preliminary stage are high. Those costs are exacerbated by heightened judicial polarization and forum-shopping. And these shifts in preliminary injunction practice have contributed to many of the cases that come to the Court in an emergency posture. A win for the respondents would be likely exacerbate these trends still more, moving the preliminary injunction further from its traditional function and towards being a merits determination.

Here is my discussion of the briefs from last week, here at the Volokh Conspiracy.

And here is The Purpose of the Preliminary Injunction, which explores these questions about this interim measure's function and the problems with how it is now being used in the federal courts.

The post Today's Argument in Lackey v. Stinnie: Attorneys' Fees and Preliminary Injunctions appeared first on Reason.com.

[Curtis Bradley] New Book on Historical Gloss and Foreign Affairs, Part II

This is the second of five posts about my new book, Historical Gloss and Foreign Affairs: Constitutional Authority in Practice. In the first post, I addressed some general points about the role of historical gloss in constitutional interpretation, and I explained why gloss has had particular relevance in the foreign affairs area.

This is the second of five posts about my new book, Historical Gloss and Foreign Affairs: Constitutional Authority in Practice. In the first post, I addressed some general points about the role of historical gloss in constitutional interpretation, and I explained why gloss has had particular relevance in the foreign affairs area.

In this post, I discuss the phenomenon of executive agreements.

Article II of the Constitution describes how treaties are to be made: by the President with the advice and consent of two-thirds of the Senate. But from early in our history, presidents have sometimes concluded international agreements through other processes.

Agreements concluded with either the ex ante or ex post approval of a majority of Congress are sometimes referred to as "congressional-executive agreements" and those concluded based solely on the President's authority are sometimes referred to as "sole executive agreements." The term "executive agreements" is used in the United States to distinguish them from agreements concluded through the Article II process, but under international law these are all treaties.

There were executive agreements even in the early days of the nation, but the practice grew over time. According to one widely cited calculation, in the first fifty years after the adoption of the Constitution, the federal government concluded 60 Article II treaties and only 27 executive agreements. The executive agreements concerned matters such the international exchange of mail and the settlement of American claims against foreign governments.

By contrast, in the fifty-year period from 1939 to 1989, there were, according to a State Department calculation, 702 Article II treaties and 11,698 executive agreements. In other words, executive agreements constituted almost 95% of the overall international agreements during that period.

This trend has continued during the last several decades. In fact, in recent years the use of the Article II treaty process has slowed to a trickle, so almost all binding international agreements concluded by the United States have been executive agreements.

As I explain in the book:

Part of the reason for the substantial growth in executive agreements, especially after World War II, has been practical necessity: as the United States became a major world power, and as international affairs became more complex, the executive branch needed to conclude many more agreements than could reasonably be considered by the Senate. The House, moreover, insisted on a role in the making of international agreements, as such agreements increasingly addressed matters relating to congressional prerogatives. Both Congress and the executive branch responded by developing alternatives to the Article II treaty process.

When the Supreme Court has considered cases involving executive agreements, it has upheld them, in large part because of historical practice.

To take one example, in upholding an executive agreement made by President Jimmy Carter settling the Iran hostage crisis, the Court in Dames & Moore v. Regan (1981) noted that, although agreements settling claims with foreign nations have sometimes been made by treaty, "there has also been a longstanding practice of settling such claims by executive agreement."

Not surprisingly, the executive branch also relies heavily on practice in defending the legality of these agreements.

For example, a 1994 Office of Legal Counsel memorandum defending the legality of the GATT trade agreement (which was concluded through majority congressional approval rather than two-thirds senate consent) argued that "a significant guide to the interpretation of the Constitution's requirements is the practical construction placed on it by the executive and legislative branches acting together."

The chief debate today is not over whether executive agreements are constitutional as a general matter, but rather over the extent to which they are interchangeable with Article II treaties.

Executive agreements (especially congressional-executive agreements) are used for a wide range of subject areas, but not all of them. The Senate has successfully insisted, for example, that arms control and human rights agreements be processed as Article II treaties. And practice suggests that the permissible use of sole executive agreements is substantially narrower than for Article II treaties.

As I conclude in Chapter 4 of the book:

Although it seems settled that congressional-executive agreements are generally constitutional, the practice does not yet support complete interchangeability of these instruments with Article II treaties. In addition, although it seems settled that presidents have some authority to conclude sole executive agreements—to resolve American claims against foreign governments, for example—the bounds of this authority are unclear and sometimes contested, and practice does not suggest anything like full interchangeability of these agreements with Article II treaties.

Without denying that there are boundary lines, the courts so far have been content to let the political branches work them out.

The book also contends that the historical gloss account of the rise of executive agreements is more descriptively accurate than accounts focused on a particular "constitutional moment," such as a moment in the mid-1940s when there was extensive debate about the legitimacy of executive agreements:

It is true … that most ex post congressional-executive agreements have been concluded since World War II, but some of these agreements occurred earlier, and in any event, those agreements are a small part of the executive agreement landscape (only about one per year in recent decades). The vast majority of executive agreements today are ex ante congressional-executive agreements, a type of agreement that can trace its lineage back to the 1790s. Moreover, the debates in the 1940s, while an important part of the history, did not in fact settle core issues, such as the extent to which congressional-executive agreements (whether ex ante or ex post) are interchangeable with Article II treaties. Historical gloss provides a better account of constitutional development in this area.

The post New Book on Historical Gloss and Foreign Affairs, Part II appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 8, 1888

10/8/1888: Chief Justice Melville Fuller takes the judicial oath.

Chief Justice Melville Fuller

Chief Justice Melville FullerThe post Today in Supreme Court History: October 8, 1888 appeared first on Reason.com.

October 7, 2024

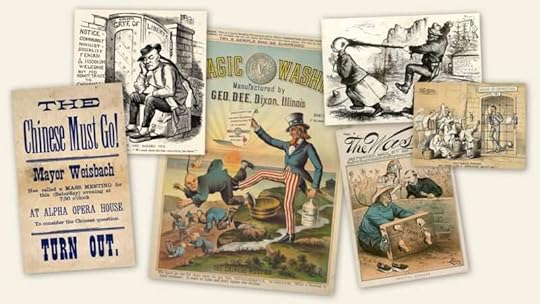

[Ilya Somin] The Economic Impact of the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred most Chinese immigration, was one of the most important immigration restrictions in American history. It barred large numbers of Chinese immigrants, condemning them to a life of poverty and oppression. It also set the stage for later immigration restrictions. Perhaps even more significantly, it led to the Supreme Court's awful ruling in the 1889 Chinese Exclusion Case, which ruled that the federal government had a general power to restrict migration, despite the absence of any textual or originalist basis for it. That, of course helped make future immigration restrictions possible. Elsewhere, I have argued the Chinese Exclusion Case should be added to the "anti-canon" of constitutional law.

A new study for the National Bureau of Economic Research, authored by economists Joe Long, Carlo Medici, Nancy Qian and Marco Tabellini assesses the economic impact of the Act. One of the main rationales for its passage was to benefit white workers, who were supposedly victimized by competition from the Chinese. Did it achieve that goal? Turns out not. Here is the abstract of the new NBER study:

This paper investigates the economic consequences of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned immigration from China to the United States. The Act reduced the number of Chinese workers of all skill levels residing in the U.S. It also reduced the labor supply and the quality of jobs held by white and U.S.-born workers, the intended beneficiaries of the Act, and reduced manufacturing output. The results suggest that the Chinese Exclusion Act slowed economic growth in western states until at least 1940.

This should not be a surprising result. Immigrants contribute disproportionately to economic growth and innovation, and nineteenth century Chinese immigration did so, as well. The result is also consistent with modern data indicating that mass deportations of immigrants destroy more jobs for native-born citizens than they create.

The study does not prove that no white workers were ever displaced by Chinese immigrants. Some almost certainly were. The authors of the NBER study point this out, and note that the Exclusion Act benefited "local" white miners competing with Chinese miners. But such effects were outweighed by the much larger number of white workers who benefited from Chinese migration, including the associated job opportunities it created. The economy is not a zero-sum game, and the interests of workers from different ethnic and racial groups are more mutually reinforcing than conflicting. I explained this dynamic in a bit more detail here.

The post The Economic Impact of the Chinese Exclusion Act appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Compendium of Writings on the October 7 War and Western Reactions to it

Today is the one year anniversary of the horrific October 7, 2023 Hamas terrorist attack on Israel. The resulting war continues. I wish there was something I could say to ease the pain of the victims of the attack, and their families. But that task is far beyond my very limited eloquence.

Still, over the past year I have written pieces on various aspects of the conflict and the reaction to it in the West, that may be of interest. This post is a compilation of them. I haven't written as much about this conflict as the Russia-Ukraine War. But there is enough to be worth compiling.

I hold a somewhat unusual combination of views on the conflict. I am no great fan of the present Israeli government, or of the ideology of Zionism (the latter because of my general opposition to ethno-nationalism). Yet I nonetheless hope Israel wipes out Hamas and deals a decisive defeat to its other adversaries, as well. For all its serious flaws from the standpoint of liberal values, Israel is incomparably superior to its enemies.

A small anecdote can help illustrate the point. In December, I am scheduled to be a visiting professor at Uriel Reichman University in Israel. One of the meetings tentatively planned is one with Arab Israeli legal academic Mohammed Wattad; since we last met in 2016, he has become the president of one of the country's major universities.

Can you imagine a Jew leading any major institution under the rule of Hamas, Hezbollah, Iran, or even the Palestinian Authority? The question answers itself. Indeed, a Jew probably could not even remain alive for long under these regimes. Hamas and Hezbollah severely repressive even towards Arab Muslims who dare dissent from the rulers' quasi-medieval theocracy.

As Wattad will likely remind me, Arabs still face considerable discrimination in Israel. That is wrong, and deserves condemnation. But the rule of Hamas, Hezbollah and the PA is vastly worse. Arabs under Israeli rule not only have more rights than ethnic and religious minorities under the control of Israel's enemies; they even have more rights than do Arab (or Iranian) Muslims under the latter regimes. Things are worse for West Bank Palestinians than Arab Israelis. But even they are unlikely to be better off with a Hamas victory that would put them under the rule of a brutal theocratic dictatorship.

In any conflict, I prefer the victory of the side that better approximates liberal democratic values—at least in situations where there is a meaningful difference between the two. In this case, there is no question that side is Israel.

Without further ado, here are links to my writings on the post-October 7 conflict. For convenience, I have put them in chronological order, and divided them into one section on the war itself and one on the Western reaction, including resulting protest movements. All of these writings are posts published here on the Volokh Conspiracy blog:

Writings on the War and Related Policy Issues

"Those Who Support Israel Against Hamas Should also Back Ukraine Against Russia, Oct. 12, 2023. There are many parallels between the two conflicts. The post is primarily directed at right-wingers who back Israel, but not Ukraine. But most of the points it makes apply equally to leftists who hold the exact opposite combination of views.

"Hamas Attack Should Teach Us the Folly of Hostage Deals with Terrorists,"Oct. 17, 2023. This may be one of my most unpopular takes. It may seem like only a cruel and heartless person could possibly oppose deals that release hostages. But, as I point out in the piece, such deals incentivize further terrorism and hostage taking. The October 7 attack itself was masterminded by Yahya Sinwar, a Hamas leader released in the 2011 Shalit deal, in which the Israelis released some 1200 terrorists in exchange for one soldier captured by Hamas. I was one of the few critics of the Shalit deal at the time it happened. Things turned out much worse than even I expected.

"The Moral and Strategic Case for Opening Doors to Gaza Refugees," Oct. 24, 2023. Granting refuge to Palestinian civilians who wish to flee the war and Hamas's repressive rule is both a moral imperative, and a way to make it easier for Israel to crush Hamas. For somewhat different reasons, this view is fiercely opposed by a combination of Western right-wingers, far leftists, and supporters of Palestinian nationalism. This combination of opponents actually increases my confidence that it is right. Interestingly, this is an issue where I find myself largely in agreement with my much more conservative colleague and co-blogger Eugene Kontorovich.

"Biden is Right to Grant Temporary Refuge to Palestinian Migrants Already in US, but Should go Further," Feb. 15, 2024.

"Why I Don't Buy the Idea that You Can't Kill an Idea," Feb. 24, 2024. It's often said you can't defeat movements like Hamas and Hezbollah by military means, because "you can't kill an idea." This post explains why that ubiquitous claim is wrong. Though I also emphasize that doesn't mean the Israelis should rely on force alone, or that they need not observe any moral constraints on their military measures.

Writings on Western Reactions to the War and Protest Movements

"Some Cancellations are Justified," Oct. 15, 2023. Why employers and others are often justified in refusing to hire people who express support for Hamas terrorism. As noted in the post, this is not a new position adopted in response to controversies arising from the October 7 war. It builds on arguments I advanced years before.

"Far-Left Support for Hamas is not an Aberration,"Oct. 30, 2023. Western far-leftists have a long history of supporting repression and mass murder. Thus, we should not be surprised that many of them now support Hamas. As noted in the post, "far left" is not a pejorative term for anyone to the left of me. As used here, it has a far more specific and narrower meaning.

"Student Movements Are Often Wrong," April 26, 2024. The idea that causes espoused by student-led movements are always or almost always right is a myth. Today's student anti-Israel movement is just the most recent of many counterexamples. Obviously, movements led by older people are often misguided, as well.

"Campus Anti-Israel Protests and the Ethics of Civil Disobedience," June 5, 2024. Violence and other lawbreaking perpetrated by many campus anti-Israel protesters can't be justified by theories of civil disobedience.

The post Compendium of Writings on the October 7 War and Western Reactions to it appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] The 13th Annual Harlan Institute Virtual Supreme Court Competition

The Harlan Institute is pleased to announce the Thirteenth Annual Virtual Supreme Court Competition. This competition offers teams of two high school students the opportunity to research cutting-edge constitutional law, write persuasive appellate briefs, argue against other students through video chats, and try to persuade a panel of esteemed attorneys during oral argument that their side is correct. This year the competition focuses on Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton.

The competition is endorsed by the Center for Civic Education's We The People Competition:

Tournament InstructionsThe Virtual Supreme Court Competition helps students gain the skills they need to understand, synthesize, and advocate for reasoned legal positions on timely and relevant constitutional issues, and in doing so deepens their commitment to the rule of law. The program directly supports the highest goals of the Center for Civic Education to develop enlightened and responsible members of our society, and it is a privilege to be a part of this important work. Christopher R. Riano President, The Center for Civic Education Member Board of Advisors, The Harlan Institute

Teams of two high-school students will write an appellate brief, and present oral arguments, addressing the following question:

Whether Texas House Bill 1181 should be reviewed with rational-basis review scrutiny or strict scrutiny?Petitioners will argue that Texas House Bill 1181 should be reviewed with strict scrutiny.

Respondents will argue that Texas House Bill 1181 should be reviewed with rational basis scrutiny.

Phase 1—Research and Write Your BriefCoaches can register their teams at the Institute for Competition Sciences (ICS). ICS will generate a number for each team. Odd-numbered teams will represent the Petitioners and even-numbered teams will represent the Respondents.

Teams will research and write their briefs. Carefully review the lesson plan. The brief must be a minimum of 2,000 words. Please download this template. The brief should have the following sections:

Table of Cited Authorities: List all of the original sources, and other documents you cite in your brief. Summary of Argument: State your position succinctly in 250 words or less. Argument: Structure your argument based on at least five Supreme Court precedents. The more authorities you cite, the stronger your argument will be–and the more likely your team will advance. Conclusion: Summarize your argument, and argue how the Supreme Court should decide this issue.Be sure to proofread your work. The work must be yours, and you may not seek help from anyone else–including attorneys or law students. Students who submit plagiarized briefs will be disqualified.

Please review the winning submissions from previous years:

OT 2023—Moody v. NetChoice OT 2022—Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard OT 2021—New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen OT 2020 – Torres v. Madrid OT 2019 – Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue OT 2018 – Timbs v. Indiana OT 2017 – Carpenter v. United States OT 2016 – Trinity Lutheran Church v. Comer OT 2015 – Abigail Fisher v. University of Texas, Austin (II) OT 2014 – Zivotofsky v. Kerry OT 2013 – National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning OT 2012 – Abigail Fisher v. University of Texas, Austin (I) Phase 2—Virtual MentoringTeams that register before November 4, 2024 will be invited to participate in a virtual mentoring session. These sessions will be hosted during the week of December 2, 2024. The Harlan Institute will match each class with a mentor from our network. These sessions will be helpful to finalize your briefs and prepare your preliminary round arguments.

Phase 3—Preliminary RoundFor the preliminary round, each team must prepare a YouTube video. The argument must be at least 15 minutes in length. Coaches will ask their students ten questions from the lesson plan.

Teams will upload a PDF of their brief, as well as a link to their YouTube video to the Institute of Competition Sciences. The deadline for the preliminary round will be December 16, 2024. The brief and preliminary round video will be scored based on this rubric.

Phase 4—Virtual RoundsWe will hold the Virtual Rounds over Zoom:

Semifinal Round: 2/10/25, 2/11/25, 2/12/25 Round of 8: 2/24/25, 2/25/25, 2/26/25 Round of 4: 3/24/25, 3/25/25, 3/26/25The virtual rounds will be scored based on this rubric. This video offers five tips to prepare for oral argument:

Phase 5—Championship Round RoundsThe top teams will receive a free trip to Washington, D.C. to argue the championship round before federal judges on May 1, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kBPlh... https://youtu.be/EsCp4OI-Uqs?si=f9PkG...

Coaches can register their teams at the Institute of Competition Sciences. Read the problem, and get started! Good luck. Please send any questions to info@harlaninstitute.org.

The post The 13th Annual Harlan Institute Virtual Supreme Court Competition appeared first on Reason.com.

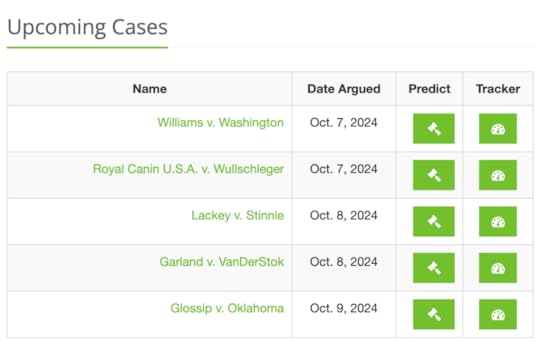

[Josh Blackman] Oyez! Oyez! Oyez! The October Term 2024 of FantasySCOTUS is now in session

I am honored to open up the 16th Season of FantasySCOTUS. I launched the site back in 2009 when I was still clerking. Now, more than decade later, thousands of Court watchers have made their predictions. Sign up today at FantasySCOTUS.net to predict the outcome of all the blockbusters this term.

I am honored to open up the 16th Season of FantasySCOTUS. I launched the site back in 2009 when I was still clerking. Now, more than decade later, thousands of Court watchers have made their predictions. Sign up today at FantasySCOTUS.net to predict the outcome of all the blockbusters this term.

The post Oyez! Oyez! Oyez! The October Term 2024 of FantasySCOTUS is now in session appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Federal Prosecution for Spray-Painting "Hamas Is Comin" on Monument in D.C.

From the government's supporting affidavit in U.S. v. Mahdawi (D.D.C.); Mahdawi's actions were part of a broader demonstration at which some "individuals … pulled down flags affixed to the flagpoles; burned flags and objects; interfered with law enforcement's ability to place individuals under arrest; and sprayed graffiti on multiple statutes and structures," causing total cleanup costs of $11K:

On July 24, 2024, between approximately 3:30 p.m. and 3:45 p.m., an individual later identified as ZAID MOHAMMAD MAHDAWI climbed the monument located in the center of Columbus Circle ….

After climbing to a ledge, MAHDAWI began to spray paint the monument…. MAHDAWI spray painted "HAMAS IS COMIN" across a side of the Columbus monument…. After completing the phrase, MAHDAWI spray-painted an inverted red triangle above the slogan.

Based on the foregoing, your affiant submits there is probable cause to believe that MAHDAWI violated 18 U.S.C. § 1361 by willfully injuring or depredating any property of the United States in an amount less than $1,000….

See also the government's press release.

The post Federal Prosecution for Spray-Painting "Hamas Is Comin" on Monument in D.C. appeared first on Reason.com.

[Curtis Bradley] New Book on Historical Gloss and Foreign Affairs, Part I

In a series of five posts this week, I will describe my new book, Historical Gloss and Foreign Affairs: Constitutional Authority in Practice (Harvard University Press 2024). This first post discusses the phenomenon of "historical gloss" and explains why it has played an especially significant role in the foreign affairs area.

The core question addressed in the book is how foreign affairs authority is distributed between Congress and the President. The first thing that you might want to do in answering this question would be to consult the text of the Constitution. You would immediately encounter a problem, however, which is that the text is silent about many key issues of foreign affairs authority. For example, there is no mention in the text of the powers to declare neutrality, issue passports, recognize foreign governments, extradite criminal suspects, enter into executive agreements, terminate treaties, regulate the exclusion and deportation of non-citizens, or wage undeclared wars. As Louis Henkin noted long ago in his treatise on foreign relations law, there are a host of what appear to be "missing" foreign affairs powers that "were clearly intended for, and have always been exercised by, the federal government."

These omissions would be less of a problem if it were easy to amend the Constitution, but it is not. Amendments normally require a two-thirds vote in both the House and the Senate and an approval by three-fourths of the states. In part because of this difficulty, none of the foreign affairs provisions of the Constitution have ever been amended in the more than 230 years since the Constitution took effect.

Yet, to state the obvious, we live in a world that is very different from that of the Founding. The country has grown from a small group of former colonies along the eastern seaboard to fifty states including Alaska and Hawaii. The United States was a party to seven international agreements at the Founding and is now a party to many thousands. The country was extremely weak militarily at the Founding, with only about 700 people in the army and no navy, and it is now a global superpower with bases around the world and nuclear weapons. The State Department at the Founding was Thomas Jefferson and a couple of clerks, but it now has over 70,000 employees. From the perspective of the constitutional text, we are managing foreign affairs with a horse-and-buggy constitution.

As for the rest of the world, at the Founding it was thought that there were only a handful of "civilized states" with which a country like the United States might have formal diplomatic relations; now there are over 190 recognized nations. Today, threats to the United States arise less from the danger of an invasion than from the possibility of terrorist attacks, nuclear proliferation, cyber warfare, and global pandemics. International law, meanwhile, has changed dramatically: banning war as an instrument of foreign policy, regulating the protection of human rights, and seeking to protect the global environment, to name just a few of the many developments.

Perhaps the courts could fill in the gaps of our old and hard to change Constitution. But for a variety of reasons judicial review tends to be low in the foreign affairs area. There is often a lack of standing to sue, and the political question doctrine has long had particular vibrancy in the foreign affairs area. In applying these and other limiting doctrines, judges perceive that their expertise, access to relevant information, and ability to predict the outcome of decisions is lower in the foreign affairs space than in other areas. This means that judicial review of foreign affairs authority is at best sporadic, and sometimes non-existent.

As a result, constitutional law in this area is often interpreted and developed outside the courts through the practices of government, and these practices then become a form of non-judicial precedent. We can call these precedential practices "historical gloss." The word "gloss" is being used here in the sense of explaining or annotating a text, akin to medieval scholars "glossing" the Code of Justinian. As Justice Felix Frankfurter observed in his concurrence in the Youngstown steel seizure case, it "is an inadmissibly narrow conception of American constitutional law to confine it to the words of the Constitution and to disregard the gloss which life has written upon them."

Even outside the area of foreign affairs, there are a variety of reasons why it can make sense for interpreters to credit gloss when addressing matters of constitutional structure. Among other things, doing so allows for constitutional updating; it respects the political branches' judgments about what is needed for governance; and it reflects a Burkean caution about upsetting settled ways of doing things.

Not surprisingly, therefore, gloss has been an important part of the Supreme Court's constitutional interpretation since the early days of the nation. In McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), for example, Chief Justice Marshall noted that "a doubtful question [concerning] the respective powers of those who are equally the representatives of the people . . . if not put at rest by the practice of the government, ought to receive a considerable impression from that practice."

Many modern decisions have similarly invoked gloss. In a 1929 decision, the Pocket Veto Case, the Supreme Court looked to practice in discerning the scope of the President's veto power, explaining that "Long settled and established practice is a consideration of great weight in a proper interpretation of constitutional provisions of this character." In 2014, in NLRB v. Noel Canning, the Court looked to practice in discerning the scope of the recess appointments power, noting that "this Court has treated practice as an important interpretive factor even when the nature or longevity of that practice is subject to dispute, and even when that practice began after the founding era." In 2020, in Trump v. Mazars, the Court, in considering the scope of executive privilege, acknowledged that "Such longstanding practice 'is a consideration of great weight' in cases concerning 'the allocation of power between [the] two elected branches of Government,' . . . ."

Gloss reasoning has also long been prevalent in constitutional interpretation outside of the courts. There are countless examples, but the following quotes will provide a sense of the phenomenon: In 1798, Representative Charles Pinckney argued that a broad delegation to the President of authority to raise troops (on the eve of war with France) was constitutional in part because of practice (even though the Constitution at that point had been operating for only nine years), reasoning that "where a thing has frequently been done in one way, and no objections raised to that course, it was reasonable to suppose that course was not unconstitutional." In 1836, John Quincy Adams, in his eulogy for James Madison, contended that even though it was not obvious from the constitutional text that the President had some authority to initiate the use of military force, "an experience of fifty years has proved that in numberless cases he has and must have exercised that power." In 1916, William Howard Taft, reflecting after his presidency, explained that, "Precedents from previous administrations and from previous Congresses create an historical construction of the extent and limitations of their respective powers."

As I state in the Conclusion of my book:

As this book has shown, much of the U.S. constitutional law of foreign affairs has been worked out through historic governmental practice. The text of the Constitution is unclear about many issues of foreign affairs authority, especially with respect to issues of executive power. Even when the text is clear about foreign affairs authority, it speaks to conditions that are markedly different from those today. Over the course of U.S. history, Congress and the President have determined the details of institutional authority in this area, often in ways that have helped the United States better respond to changes in the world. Sometimes the political branches developed the law in this area through mutual understandings and cooperation, and at other times they did so through conflict. The courts, meanwhile, have largely deferred to these arrangements unless they have violated individual rights.

In the next several posts, I will describe three important examples of foreign affairs powers that have been heavily informed by historical gloss: the conclusion of executive agreements, the termination of treaties, and the use of military force. Each of these examples is covered in detail in the book. I will then conclude this series of posts by discussing one of the central objections to relying on historical gloss when interpreting the separation of powers: that it unduly favors the expansion of executive power.

The post New Book on Historical Gloss and Foreign Affairs, Part I appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers