Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 254

October 3, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Insulting Anti-Gay Preaching at PrideFest Event May Have Been Protected by the First Amendment

From an order this Monday by Judge Kevin Castel (S.D.N.Y.) In Rusfeldt v. City of New York (just an excerpt of a long opinion):

Pastor Aden Rusfeldt brings claims arising from his interactions with and arrest by officers of the New York City Police Department ("NYPD") that occurred while he was holding up a large sign on a long pole reading "Fags and Whores Burn in Hell" at the June 27, 2021 PrideFest in Manhattan….

The First Amendment protects Rusfeldt's right to express his message and the Pride festivalgoers' right to express their hostility to his message. The expressive elements of Rusfeldt's hateful message and the festivalgoers' expressed antipathy to the message do not require law enforcement to turn a blind eye to the potential that the physical proximity of the two groups could lead to unlawful behavior. But the permissible means to mitigate the potential for escalation cannot be the removal of a person engaging in protected speech merely to appease others offended by his expressive activity. Provocations to immediate violence may change the calculus.

When police officers learned that objects and liquids had been thrown by members of the crowd of Pride festivalgoers in the direction of Rusfeldt, they stepped into action. They could have ordered the crowd dispersed or arrested an offender, if the person was observed and could be identified and apprehended. Police officers selected a different response, at first standing in between Rusfeldt's group and the crowd and then moving metal barriers into place between the two groups, which did not impair the ability of Rusfeldt or the festivalgoers to deliver their messages.

Law enforcement also had concerns that Rusfeldt was on the sidewalk with a long pole holding his message aloft, potentially blocking the sidewalk and presenting a hazard to others. Police officers told Rusfeldt to move—or, as defendants now characterize it, ordered him to disperse. Rusfeldt was ultimately arrested. The "Complaint/Information" for the violation of at least one of New York's disorderly conduct provisions (N.Y. Penal Law § 240.20(7)), which was affirmed by the officer on the date of the arrest, noted that Rusfeldt was "in possession of a large metal pole. Defendant was asked to relinquish the pole and refused to do so." The charges were later dismissed without any court appearance.

The lawfulness of Rusfeldt's arrest does not turn on whether the individual officers loved or hated his message but on whether they had probable cause to arrest him and whether they would have arrested another person with a very different message under similar circumstances.

The fog of police action on June 27, 2021 is not sufficiently clarified by snippets of video, augmented by deposition testimony. Material issues of fact abound that preclude this Court from definitively opining on the lawfulness of police conduct….

Defendants assert that the words used by Rusfeldt on a large sign held aloft on a pole, "Fags and Whores Burn in Hell," were intended by Rusfeldt "to shock and upset his target audience: members of the LGBTQ+ community. In that context his sign was fighting words unworthy of protection under the First Amendment."

Defendants' position is profoundly wrong. Obnoxious and loathsome speech is protected under the First Amendment. Snyder v. Phelps (2011) (citation omitted) ("If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable."); see also National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie (1977) (per curiam) (vacating order enjoining "displaying any materials which incite or promote hatred against persons of Jewish faith"); Brown v. State of Louisiana (1966) (citations omitted) ("Participants in an orderly demonstration in a public place are not chargeable with the danger, unprovoked except by the fact of the constitutionally protected demonstration itself, that their critics might react with disorder or violence.")….

Rusfeldt mounts a First Amendment challenge to his arrest. It stands or falls principally on whether there was probable cause for his arrest. The Supreme Court has considered "whether probable cause to make an arrest defeats a claim that the arrest was in retaliation for speech protected by the First Amendment." The Court concluded that the existence of probable cause defeated the claim. The Court noted one possible exception to the rule: "Although probable cause should generally defeat a retaliatory arrest claim, a narrow qualification is warranted for circumstances where officers have probable cause to make arrests, but typically exercise their discretion not to do so." …

Rusfeldt makes no effort to show that NYPD officers typically do not make arrests in similar circumstances when the participants are not engaged in expressive activity or when they are expressing a favored viewpoint. Rusfeldt's effort to draw a close analogy to police inaction in response to the conduct of the Pride crowd of festivalgoers fails. The police were across the street when objects were thrown in the direction of Rusfeldt, and the record does not permit the conclusion that the police had the ability to identify and arrest the offender or offenders. It was only Rusfeldt, and not any of the festivalgoers, who was on the sidewalk holding aloft a long metal pole supporting a banner, a pole which arguably presented a hazard to those in proximity to it. No reasonable factfinder could conclude that the waving of a rainbow flag by one Pride festivalgoer seen on a video presented a hazardous or physically offensive condition.

Rusfeldt asserts that as a matter of law there was no probable cause for his arrest. Defendants assert that as a matter of law there was probable cause for his arrest. (ECF 109 at 17-21.) The Court concludes that there are material issues of fact that preclude summary judgment.

The principal statute relied upon by the parties with respect to their probable cause arguments is N.Y. Penal Law § 240.20, which provides, in pertinent part, as follows:

A person is guilty of disorderly conduct when, with intent to cause public inconvenience, annoyance, or alarm, or recklessly creating a risk thereof: …

[(6)] He congregates with other persons in a public place and refuses to comply with a lawful order of the police to disperse; or

[(7)] He creates a hazardous or physically offensive condition by any act which serves no legitimate purpose….

Rusfeldt does not dispute that the NYPD gave him orders to leave the area, that he understood these orders, and that he did not comply with them. He also does not dispute that the NYPD officers were motivated by a desire to control or maintain the public order "that was either disrupted or threatened to be disrupted by the crowd that gathered around" him when they issued these orders. Rusfeldt argues, however, that these orders were not "orders to disperse," as the term is used in N.Y. Penal Law § 240.20(6), and that they were also unlawful orders.

An order by police for an individual to disperse or leave an area while exercising his right to free speech is a restriction on that speech. Because Rusfeldt was ordered to disperse under a New York statute and that order restricted his speech, the Court must determine both whether the order was "lawful" under New York law and whether it satisfied the requisite Supreme Court standard for a restriction of Rusfeldt's constitutional rights under the First Amendment. See id. (citations omitted) ("The First Amendment, however, 'does not guarantee the right to communicate … at all times and places or in any manner that may be desired.' … At issue here is the balance between an individual's First Amendment right to engage in a conversation on a public sidewalk with protestors and the government's interest in maintaining public safety and order.")…. [Factual details on this, as well as on whether Rusfeldt's carrying the pole or Rusfeldt's blocking the sidewalk created a hazardous condition, omitted. -EV]

The court therefore allowed Rusfeldt's First Amendment claim to go forward.

The post Insulting Anti-Gay Preaching at PrideFest Event May Have Been Protected by the First Amendment appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 3, 1990

10/3/1990: Justice David Souter takes the oath.

Justice David Souter

Justice David SouterThe post Today in Supreme Court History: October 3, 1990 appeared first on Reason.com.

October 2, 2024

[Stephen Halbrook] Second Amendment Roundup: ATF's Final Rule Implicates the Right to Bear Arms

Getting closer to October 8, when the Supreme Court will oral argument in Garland v. VanDerStok, I'd like to address whether ATF's 2022 Final Rule drastically expanding the meaning of the statutory term "firearm" implicates the Second Amendment. By redefining "firearm" to include unfinished materials, information, jigs, and tools, the supply has dried up for persons freely to obtain what they need to construct self-made firearms. Indeed, that is the purpose of the rule.

No one disputes that the right to keep and bear arms entails the right to acquire them, which presupposes that firearms must be made. As explained in my previous post, the Federal Firearms Act of 1938 was the first federal law to require those engaged in the business of manufacturing firearms to obtain licenses. To date, the Gun Control Act (GCA), passed in 1968, provides no restrictions on a person acquiring materials and making his or her own firearm.

ATF's commentary to the Final Rule argues that it does not violate the Second Amendment, because "the GCA and this rule do not prohibit individuals from assembling or otherwise making their own firearms from parts for personal use," nor do they "prohibit[] law-abiding citizens from completing, assembling, or transferring firearms without a license" as long as they are not "engaged in the business." Yet the rule does prevent individuals from "making their own firearms from parts" by purporting to extend the statutory definition of "firearm" to raw material and previously-unrestricted parts that may no longer be bought and sold except through federal firearm licensees.

The Supreme Court in District of Columbia v. Heller did not "cast doubt on … laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms." ATF's regulations are not "laws" and have no basis in the laws passed by Congress, which enacted the exclusive definition of "firearm." The Final Rule impedes the making and acquisition of firearms by imposing new, onerous restrictions, costs, and potential criminal jeopardy.

The commentary quotes the above words from Heller, but those words do not justify the policy argument in the next sentence: "PMFs [privately made firearms], like commercially produced firearms, must be able to be traced through the records of licensees when the PMFs are involved in crimes." First, as covered in my last post, that a firearm was traced does not indicate that it was used in a crime. Second, a firearm "must be able to be traced" only when, as the GCA provides, it comes from a licensed manufacturer or importer, is distributed by a licensed dealer, and is required to be marked with a serial number. ATF's contention regarding the need for tracing is not a legal argument, but is purely a policy argument which can only be addressed by Congress.

In New York State Rifle & Pistol Ass'n, Inc. v. Bruen, 597 U.S. 1, 17 (2022), the Supreme Court held: "When the Second Amendment's plain text covers an individual's conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct. The government must then justify its regulation by demonstrating that it is consistent with the Nation's historical tradition of firearm regulation."

Before looking for possible historical regulations, consider the Court's longstanding interpretative guide, expressed long ago in Ex parte Bain (1887), that "in the construction of the language of the Constitution . . . we are to place ourselves as nearly as possible in the condition of the men who framed that instrument. Undoubtedly, the framers … had for a long time been absorbed in considering the arbitrary encroachments of the Crown on the liberty of the subject…."

I've documented countless such encroachments in The Founders' Second Amendment, but especially pertinent here is the 1777 plan by British Colonial Undersecretary William Knox: "The Militia Laws should be repealed and none suffered to be re-enacted, & the Arms of all the People should be taken away, . . . nor should any Foundery or manufactuary of Arms, Gunpowder, or Warlike Stores, be ever suffered in America…." And consider this letter from Thomas Jefferson in 1793, two years after ratification of the Second Amendment: "Our citizens have always been free to make, vend, and export arms. It is the constant occupation and livelihood of some of them."

Extensive documentation of this aspect of our history is set forth by Joseph Greenlee in "The American Tradition of Self-Made Arms," 54 St. Mary's L.J. 35 (2023). He distilled a good part of this research for VanDerStok in the amicus brief of the National Rifle Association.

During colonial times, Greenlee shows, acquisition of firearms by importation and local manufacture was essential for food and protection. Gunsmiths in towns and on the frontier made and repaired guns, often obtaining intricate parts like locks and barrels from other sources. The trade was carried out by individual craftsmen. The outbreak of the War for Independence brought a high demand for muskets from the States and the Continental Congress. This cottage industry produced over a fourth of the long arms used by American troops during the war. Even children helped assemble cartridges.

James Whisker, a prominent historian of early gunmaking, writes in The Gunsmith's Trade (1992): "Gun crafting was one of several ways Americans expressed their unrestrained democratic impulses at the time of the adoption of the Bill of Rights.… The climate of opinion was clearly such that it would have supported a broad distribution of this right to the people…."

Private gunmakers in the United States have developed many of the most significant innovations in firearm technology. They include the forgotten makers of Pennsylvania rifles, Samuel Colt and his revolvers, the developers of Winchester lever action rifles, John Moses Browning and his countless innovations, and John Garand, inventor of the M1 Garand battle rifle that gave American GIs an edge in World War II. Countless Americans, in bygone times and today, fashion, make, assemble, customize, and repair their own firearms. As long as they were not engaged in the business of manufacturing firearms, Congress has never regulated private gunmakers.

ATF's Final Rule aims to prohibit the free acquisition of items that are not firearms by redefining them as firearms. The government's brief brushes off any Second Amendment consequences – saying "the Rule's interpretation of the Act is entirely consistent with the Second Amendment" – without even attempting to show, as Bruen requires, that the Final Rule "is consistent with the Nation's historical tradition of firearm regulation." While this has not been litigated as a Second Amendment case, the rule of constitutional doubt should discourage an expansive reading of the GCA.

The amici brief of the Gun Violence Prevention Groups steps in to provide a Bruen analysis, relying on a Student Note "Gunmaking at the Founding" forthcoming in Stanford Law Review. However, part VI of the NRA brief, relying on that same source, refutes it point by point. The following seven categories (in quotation marks) are claimed to constitute a "historical tradition of firearm regulation," but for the following reasons given in the NRA brief, they do no such thing:

The "standard setting" laws established what arms could be used in militia service or sold to governments for militia use. The "inspection" laws required militiamen to prove to militia officers that they possessed the mandated militia arms. The "licensing" law was a 1642 Connecticut law requiring a license for any "Smith" to "doe any work for" hostile American Indians or for any person to "trade any Instrument or matter made of iron or steele" to them. The "labor" laws simply refer to the legal relationship between masters and apprentices. The "impressment" laws were generally wartime measures that required gunsmiths to prioritize military arms. The "restrictions on dangerous persons" include prohibitions on providing firearms to allegedly dangerous persons and restrictions on repairing firearms for American Indians. The "gunpowder-making" regulations did not apply to firearms and instead targeted gunpowder storage and sales.The Gun Violence Prevention Groups' brief also cites "the longstanding practice of marking weapons—a precursor to modern-day serialization." But the marking requirements applied only to public arms owned or used by the States. As historian Whisker relates, "a gunsmith could choose to mark his guns, or not mark them, in any way he chose." During the Revolution, many gunsmiths refrained from marking their firearms so that, in case the British won, those firearms could not be traced back to their makers.

As the Republic grew, some manufacturers voluntarily inscribed their firearms with serial numbers and others did not. It was not until 1958 that licensed manufacturers were required to engrave serial numbers on firearms, excluding shotguns and .22 caliber rifles. Only in 1968 did Congress require licensees to serialize all "firearms" as it defined them. To date, it remains lawful under the Gun Control Act to make your own gun without restriction.

Finally, it is worth recalling that, in passing the Firearm Owners' Protection Act of 1986, Congress found that "the rights of citizens … to keep and bear arms under the second amendment to the United States Constitution … require[d] additional legislation to correct existing firearms statutes" and reaffirmed its intent not to "place any undue or unnecessary Federal restrictions or burdens" on firearm owners or "to discourage or eliminate the private ownership or use of firearms by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes." It admonished that the Attorney General may prescribe "only such rules and regulations as are necessary to carry out the provisions of this chapter." The Final Rule simply disregards these statutory "rules of engagement" and writes off the Second Amendment as if it is a "second class right."

The post Second Amendment Roundup: ATF's Final Rule Implicates the Right to Bear Arms appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Judge Blocks California Law Restricting "Materially Deceptive" Election-Related Deepfakes

From today's decision by Judge John Mendez (E.D. Cal.) in Kohls v. Bonta:

Plaintiff Christopher Kohls (aka "Mr. Reagan") is an individual who creates digital content about political figures. His videos contain demonstrably false information that include sounds or visuals that are significantly edited or digitally generated using artificial intelligence …. Plaintiff's videos are considered by him to be parody or satire. In response to videos posted by Plaintiff parodying presidential candidate Kamala Harris and other AI generated "deepfakes," the California legislature enacted AB 2839. AB 2839, according to Plaintiff, would allow any political candidate, election official, the Secretary of State, and everyone who sees his AI-generated videos to sue him for damages and injunctive relief during an election period which runs 120 days before an election to 60 days after an election….

AB 2839 does not pass constitutional scrutiny because the law does not use the least restrictive means available for advancing the State's interest here. As Plaintiffs persuasively argue, counter speech is a less restrictive alternative to prohibiting videos such as those posted by Plaintiff, no matter how offensive or inappropriate someone may find them. "'Especially as to political speech, counter speech is the tried and true buffer and elixir,' not speech restriction." …

The court began by concluding that AB 2839 doesn't fall within the existing defamation exception to First Amendment protection, and isn't subject to any other doctrine that categorically lowers protection for false statements in election campaigns:

While Defendants attempt to analogize AB 2839 to a restriction on defamatory statements, the statute itself does not use the word "defamation" and by its own definition, extends beyond the legal standard for defamation to include any false or materially deceptive content that is "reasonably likely" to harm the "reputation or electoral prospects of a candidate." At face value, AB 2839 does much more than punish potential defamatory statements since the statute does not require actual harm and sanctions any digitally manipulated content that is "reasonably likely" to "harm" the amorphous "electoral prospects" of a candidate or elected official.

Moreover, all "deepfakes" or any content that "falsely appear[s] to a reasonable person to be an authentic record of the content depicted in the media" are automatically subject to civil liability because they are categorically encapsulated in the definition of "materially deceptive content" used throughout the statute. Thus, even artificially manipulated content that does not implicate reputational harm but could arguably affect a candidate's electoral prospects is swept under this statute and subject to civil liability.

The statute also punishes such altered content that depicts an "elections official" or "voting machine, ballot, voting site, or other property or equipment" that is "reasonably likely" to falsely "undermine confidence" in the outcome of an election contest. On top of these provisions lacking any objective metric and being difficult to ascertain, there are many acts that can be "do[ne] or [words that can be] sa[id]" that could harm the "electoral prospects" of a public official or "undermine confidence" in an election

Almost any digitally altered content, when left up to an arbitrary individual on the internet, could be considered harmful. For example, AI-generated approximate numbers on voter turnout could be considered false content that reasonably undermines confidence in the outcome of an election under this statute. On the other hand, many "harmful" depictions when shown to a variety of individuals may not ultimately influence electoral prospects or undermine confidence in an election at all. As Plaintiff persuasively points out, AB 2839 "relies on various subjective terms and awkwardly-phrased mens rea," which has the effect of implicating vast amounts of political and constitutionally protected speech.

Defendants further argue that AB 2839 falls into the possible exceptions recognized in U.S. v. Alvarez (2012) for lies that involve "some … legally cognizable harm." However, the legally cognizable harms Alvarez mentions does not include the "tangible harms to electoral integrity" Defendants claim that AB 2839 penalizes. Instead, the potentially unprotected lies Alvarez cognized were limited to existing causes of action such as "invasion of privacy or the costs of vexatious litigation"; "false statements made to Government officials, in communications concerning official matters"; and lies that are "integral to criminal conduct," a category that might include "falsely representing that one is speaking on behalf of the Government, or … impersonating a Government officer." 567 U.S. at 719-722 (2012). AB 2839 implicates none of the legally cognizable harms recognized by Alvarez and thereby unconstitutionally suppresses broader areas of false but protected speech.

Even if AB 2839 were only targeted at knowing falsehoods that cause tangible harm, these falsehoods as well as other false statements are precisely the types of speech protected by the First Amendment. In New York Times v. Sullivan, the Supreme Court held that even deliberate lies (said with "actual malice") about the government are constitutionally protected. The Supreme Court further articulated that "prosecutions for libel on government"—including civil liability for such libel—"have [no] place in the American system of jurisprudence." See also Rosenblatt v. Baer (1966) (holding that "the Constitution does not tolerate in any form" "prosecutions for libel on government"). These same principles safeguarding the people's right to criticize government and government officials apply even in the new technological age when media may be digitally altered: civil penalties for criticisms on the government like those sanctioned by AB 2839 have no place in our system of governance….

The court therefore evaluated the statute, as a content-based speech restriction, under strict scrutiny and concluded that it likely failed that test:

Under strict scrutiny, a state must use the "least restrictive means available for advancing [its] interest." The First Amendment does not "permit speech-restrictive measures when the state may remedy the problem by implementing or enforcing laws that do not infringe on speech." … "If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence."

Supreme Court precedent illuminates that while a well-founded fear of a digitally manipulated media landscape may be justified, this fear does not give legislators unbridled license to bulldoze over the longstanding tradition of critique, parody, and satire protected by the First Amendment. YouTube videos, Facebook posts, and X tweets are the newspaper advertisements and political cartoons of today, and the First Amendment protects an individual's right to speak regardless of the new medium these critiques may take. Other statutory causes of action such as privacy torts, copyright infringement, or defamation already provide recourse to public figures or private individuals whose reputations may be afflicted by artificially altered depictions peddled by satirists or opportunists on the internet. Additionally, AB 2839 by its own terms proposes other less restrictive means of regulating artificially manipulated content in the statute itself. The safe harbor carveouts of the statute attempt to implement labelling requirements, which if narrowly tailored enough, could pass constitutional muster….

In addition to encumbering protected speech, there is a more pressing reason to meet statutes that aim to regulate political speech, like AB 2839 does, with skepticism. To quote Justices Breyer and Alito in Alvarez, "[t]here are broad areas in which any attempt by the state to penalize purportedly false speech would present a grave and unacceptable danger of suppressing truthful speech." In analyzing regulations on speech, "[t]he point is not that there is no such thing as truth or falsity in these areas or that the truth is always impossible to ascertain, but rather that it is perilous to permit the state to be the arbiter of truth" in certain settings.

The political context is one such setting that would be especially "perilous" for the government to be an arbiter of truth in. AB 2839 attempts to sterilize electoral content and would "open[] the door for the state to use its power for political ends." "Even a false statement may be deemed to make a valuable contribution to public debate, since it brings about 'the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.'" When political speech and electoral politics are at issue, the First Amendment has almost unequivocally dictated that Courts allow speech to flourish rather than uphold the State's attempt to suffocate it.

Upon weighing the broad categories of election related content both humorous and not that AB 2839 proscribes, the Court finds that AB 2839's legitimate sweep pales in comparison to the substantial number of its applications, as in this case, which are plainly unconstitutional. Therefore, the Court finds that Plaintiff is likely to succeed on a First Amendment facial challenge to the statute.

And the court held that the disclosure requirement for materially deceptive videos that are nonetheless parody or satire was also unconstitutional:

For parody or satire videos, AB 2839 requires a disclaimer to air for the entire duration of a video in text that is no smaller than the largest font size used in the video. In Plaintiff Kohls' case, this requirement renders his video almost unviewable, obstructing the entirety of the frame. The obstructiveness of this requirement is concerning because parody and satire have relayed creative and important messages in American politics…. In a non-commercial context like this one, AB 2839's disclosure requirement forces parodists and satirists to "speak a particular message" that they would not otherwise speak, which constitutes compelled speech that dilutes their message….

Even if some artificially altered content were subject to a lower standard for commercial speech or "exacting scrutiny" instead of strict scrutiny as the Defendants argue[,] AB 2839 could not meet its "burden to prove that the … notice is neither unjustified nor unduly burdensome" under NIFLA v. Becerra (2018), or that the disclosure is "narrowly tailored" pursuant to the standard articulated for political speech disclosures in Smith v. Helzer (9th Cir. 2024). AB 2839's size requirements for the disclosure statement in this case and many other cases would take up an entire screen, which is not reasonable because it almost certainly "drowns out" the message a parody or satire video is trying to convey. Thus, because AB 2839's disclosure requirement is overly burdensome and not narrowly tailored, it is similarly unconstitutional.

Adam Schulman and Ted Frank (Hamilton Lincoln Law Institute) represent Kohls. For more on the satire question, see this post.

The post Judge Blocks California Law Restricting "Materially Deceptive" Election-Related Deepfakes appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Stalking" a Child or Being at the Same School Event with One's Own Children?

Florida appellate courts have published many opinions in recent years (correct ones, I think) reminding trial courts of the limits on anti-harassment/stalking/cyberstalking restraining orders. Whether that is a mark of the soundness of the Florida appellate courts, of the frequency of errors by Florida lower courts, something else, or a mix of these, I can't say. But here's a recent example, from Hoover v. Peak, decided in August by Judge Thomas Winokur joined by Chief Judge Timothy Osterhaus and Judge Joseph Lewis, Jr.:

On Independence Day, 2023, Hoover aimed a Roman candle firework at several children present in his neighborhood. Peak's daughter, C.P., was one of those children. C.P. had her back turned to Hoover when the firework went off, and she suffered a minor injury to her thigh.

Peak reported the incident to the Department of Children and Families, which led to Hoover's arrest for child abuse. Hoover was also arrested for a separate domestic incident with his now estranged wife Mandelin Hoover. The court granted Mandelin Hoover a domestic violence injunction against Hoover with a no-contact provision.

Then, in August 2023, Hoover and his ex-wife—not Mandelin Hoover—attended their daughter's ninth-grade orientation at Crestview High School. C.P. was also a ninth-grader at Crestview High School. Thus, Peak, her husband, C.P., and Mandelin Hoover (Peak's purported best friend) also attended the orientation. While at the orientation, Peak and Hoover crossed paths on four occasions. Peak believed that Hoover understood his criminal case for child abuse due to the fireworks incident to also include a no-contact order as to C.P. In fact, no such provision existed.

Peak sought out the school police deputy to inform him that Hoover was on the premises and that he should be removed. At the same time, Hoover turned into the same hallway but after seeing Peak's family, he walked away. Based on the four encounters at orientation, Peak filed the underlying petition for an injunction for stalking against Hoover….

The trial court held "that Peak satisfied her burden of showing that a reasonable person would have been placed in substantial emotional distress by Hoover's actions," and granted a harassment restraining order against Hoover, but the court of appeals reversed:

Section 784.0485(1), Florida Statutes, creates a civil cause of action for injunctive relief from stalking. Paragraph (6)(a) further provides that "[u]pon notice and hearing, when it appears to the court that the petitioner is the victim of stalking, the court may grant such relief as the court deems proper …." Stalking occurs when a person "willfully, maliciously, and repeatedly follows, harasses, or cyberstalks another person[.]"

To establish a showing of "stalking" under the statutes, a petitioner must show evidence of "repeated acts" of "following, harassment, or cyberstalking." Moreover, competent, substantial evidence must be present in the record to support a finding that a "reasonable person" suffered from emotional distress due to the stalking. Here, there was neither evidence of harassment nor following—much less evidence of "repeated acts" of such actions[—]that would support an injunction for stalking….

"'Harass' means to engage in a course of conduct directed at a specific person which causes substantial emotional distress to that person and serves no legitimate purpose." {"'Course of conduct' means a pattern of conduct composed of a series of acts over a period of time, however short, which evidences a continuity of purpose. The term does not include constitutionally protected activity such as picketing or other organized protests."}

In this case, Hoover attended his daughter's Crestview High School orientation, where parents were to "walk the schedule" of their children. The Peak family and Mandelin Hoover attended the orientation with C.P. Peak, her husband, and Mandelin Hoover testified that they saw Hoover four times during the orientation:

First, near room 501. Hoover was walking toward what was likely room 514 when he allegedly turned back, saw Peak's group, and kept walking. Second, inside room 514. Hoover was in the room (the computer lab) when Peak's family entered the room, saw Hoover, and then they—the family—left the room. Hoover's ex-wife stated that when they saw the Peaks "pop" into room 514, they—the Hoover "entourage"—decided to leave to avoid any issues with Mandelin Hoover, who maintained a no-contact order against Hoover. Third, along the room 501 hallway. Peak's family was next to room 501 after they walked out of room 514 and shortly thereafter, Hoover walked towards them in the hallway from 514 to 501—which was the direction in which Hoover's daughter's math class was. Last, near the "Media Center." Peak's family was near the media center speaking with the school police officer about Hoover being at the school when he turned a corner, saw them, and turned around to walk away.All four encounters—Peak argued—were evidence of "stalking." Peak's main contention was that C.P. suffered emotional distress every time she came into contact with Hoover. Thus, Peak claimed that Hoover was "harassing" C.P. and the family. See § 784.048(1)(a), Fla. Stat. (defining "harass" as engaging in "a course of conduct directed at a specific person which causes substantial emotional distress to that person and serves no legitimate purpose[ ]"). While Peak alleged in the petition that C.P. asked "to start attending therapy to cope with the nightmares and him showing up and following her," no evidence of the alleged therapy was presented at the injunction hearing. Nor was there any evidence that a reasonable person in C.P.'s position would have suffered "substantial emotional distress." No evidence of any other dispute other than the firework incident appears in the record that would support such a finding.

Because no competent, substantial evidence is present in the record that Hoover "repeatedly harassed" C.P. or her family while at the Crestview High School orientation, we turn to whether Hoover "repeatedly followed" Peak's family….

Unlike harassment, "following" is not defined in the statute. Therefore, we apply its ordinary meaning. To follow someone is to "move behind and in the same direction" as them or "to go after [them]" or to "pursue" them "as if with the intention of overtaking [them]." Of the four "encounters" with Hoover, none showed that Hoover was "following" C.P. Mere speculation that someone is following you is not sufficient to warrant an injunction against that person…. [N]othing in the record suggests that Peak met her burden below to show Hoover "followed" or "harassed" C.P. so as to warrant the placement of a permanent injunction with restrictions on certain liberties guaranteed by our state and federal constitutions….

We "must be careful not to apply the stalking statute to infringe on another person's constitutionally protected freedom of association or free speech or apply in an overbroad manner to reach non-malicious conduct." … Hoover was attending his daughter's high school orientation with her and his ex-wife. He spent, at most, thirty minutes at the school going from classroom to classroom, "walking" his daughter's schedule. Nothing about that behavior is malicious or criminal.

Luke Newman represents Hoover.

The post "Stalking" a Child or Being at the Same School Event with One's Own Children? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "[T]his Is a Matter of Law, Not of Wounded Feelings": Univ. of Maryland May Not Ban All Oct. 7 Demonstrations …

Yesterday's opinion by Judge Peter Messitte (D. Md.) in Univ. of Md. Students for Justice in Palestine v. Bd. of Regents held (generally quite correctly, I think) that the University's revoking the SJP's reservation of space for a demonstration violated the First Amendment, because it was an attempt to suppress SJP's viewpoint. An excerpt of the facts:

SJP [at first was given a reservation, in August, for an event that it] described … as an interfaith vigil to be held on the University's College Park campus on October 7, intended to mourn lives lost in Israel's purported "genocide" in Gaza. In revoking the approval, the University also banned all student-organized events on the College Park campus on that day, as well as such events throughout the University system statewide….

For years, UMCP students as well as outsiders have used UMCP's McKeldin Mall as a forum for free expression, one of only four venues that UMCP allows for students to host "Scheduled Expressive Activity." The Mall is a rectangular field, consisting of some nine acres, centrally located on the College Park campus…..

SJP indicates that it primarily planned to use their reservation of McKeldin Mall to hold a vigil commemorating the thousands of lives lost since what it characterizes as the initiation of Israel's current attack on Gaza. Over the course of the day, the group stated that it would also host several other activities, including teach-ins about Palestinian history, culture, and solidarity between Palestinians and other marginalized groups; tables highlighting Palestinian art and traditional crafts; a visual display of kites, a motif in Palestinian poetry; as well as a vigil and inter-faith prayers. The group indicated that it had invited several SJP members who have personally lost family members in Gaza to speak. {SJP expressly indicated that it expected 25 to 50 student attendees and expressly agreed to comply with all student-organization event guidelines and policies.} …

SJP says it chose October 7 specifically because October 7 marks the beginning of what it calls Israel's most recent "genocidal campaign" which, SJP claims, has resulted in the death of over 40,000 Palestinians in Gaza. Another recognized student organization, Jewish Voice for Peace at the University of Maryland …, has agreed to co-sponsor SJP's event….

In response to public opposition, the University of Maryland canceled the event and indeed ban all student-sponsored events on Oct. 7; here's how UMD College Park's president publicly explained the cancellation:

Applications for events led by several student organizations have been submitted for October 7, and questions have been raised about the events of the day. Numerous calls have been made to cancel and restrict the events that take place that day, and I fully understand that this day opens emotional wounds and evokes deeply rooted pain. The language has been charged and the rhetoric intense.

Given the overwhelming outreach, from multiple perspectives, I requested a routine and targeted safety assessment for this day to understand the risks and safety measures associated with planned events. UMPD has assured me that there is no immediate or active threat to prompt this assessment, but the assessment is a prudent and preventive measure that will assist us to keep our safety at the forefront.

I have also consulted with the University System of Maryland about the importance of our university and all of our USM schools prioritizing safety and reflection on this one-year anniversary. Jointly, out of an abundance of caution, we concluded to host only university-sponsored events that promote reflection on this day. All other expressive events will be held prior to October 7, and then resume on October 8 in accordance with time, place and manner considerations of the First Amendment.

The court noted that the University System of Maryland has adopted the "Chicago Principles" protecting student speech, and that (even apart from that decision) has opened up the relevant space on campus as a "designated public forum," in which content discrimination is generally forbidden. (Under some recent Supreme Court cases, the space might properly be seen as a limited public forum, in which some content discrimination is allowed, but viewpoint discrimination would be forbidden in any event.) And the court held that the University's action violated the First Amendment. Here's what strikes me as the core of the analysis:

It is clear to the Court that UMCP's decision to revoke its permission to SJP to hold its event on October 7 was neither viewpoint-neutral, nor content-neutral, nor narrowly tailored to serve a significant government interest. The decision clearly came in response to possible speech that several groups or individuals claimed would be highly objectionable. It was further motivated by a concern—not unreasonable—that violence might ensue. Those potentialities, however, in no way legally justified the revocation. See Forsyth County v. Nationalist Movement (1992)…. [T]he Government has the "responsibility to permit unpopular or controversial speech in the midst of a hostile crowd reaction" …. [T]here is no "hate speech" exception to the First Amendment …. UMCP's decision to revoke appears to be nothing less than an effort to suppress speech which would be offensive to some, indeed many. This is true even if Defendants—despite their claiming early on that "no immediate or active threat" prompted their security assessment—in fact really did anticipate on-campus turbulence….

And here's more of the court's justification (these are just excerpts of a long opinion, which you can read in full):

SJP has picked a particularly controversial date to hold an event to commemorate Gaza War dead, to decry what it terms Israeli "genocide," and to promote multiple aspects of Palestinian life and culture. Groups opposing the event have taken deep offense over an event on October 7, a day when it has been widely reported that Hamas fighters invaded Jewish settlements near Gaza, killing some 1,200 occupants, torturing others, and taking some 250 hostages (said by some to be the worst day Jews have suffered since the Holocaust).

Individuals and groups opposing SJP's proposed October 7 event take further offense by reason of the event's likely references to the Hamas fighters as patriots, martyrs, or freedom fighters, and by at least one slogan arguably interpreted to call for the extinction of Israel ("From the river to the sea"). Numerous university students, parents, alumni, donors, and members of the public have expressed passionate opposition to the event.

But like them or not, these very terms appear in the media virtually daily. They are expressive of ideas, however vile they may seem to some. There is no reason why they should not be given protection as speech when they are used in the forum of a public university.

Moreover, there is no suggestion, in SJP's reservation form at least, that any space other than the commonly used McKeldin Mall will be occupied on October 7 or that Jewish students will be threatened or harassed or otherwise impeded from attending classes, or that any buildings will be occupied, an encampment established, or property destruction contemplated. SJP has held more than 70 events on campus since October 7, 2023, including meetings, protests, sit-ins, and demonstrations, all without significant disruption or conflict.

Indeed, as testified to at the September 30 hearing, the parties agree that SJP and UMCP have a respectful, even collaborative, relationship. For example, in May 2024, opposing groups held an event, Israel Fest, and counter-event (termed a boycott of Israel Fest) on opposite sides of UMCP's McKeldin Mall. Chief Mitchell testified that police set up fencing around each group, increased security personnel, checked bags, among other proactive security measures. Despite the controversial nature of the event, it was, Chief Mitchell testified, "very peaceful." In all, SJP appears to want to hold another peaceable, if highly controversial, event.

But this is a matter of law, not of wounded feelings. Free speech as guaranteed by the First Amendment may be the most important law this country has. In many ways, all other basic freedoms—freedom of religion, of the press, of the right to assemble, and to petition the government—depend upon it. Accordingly, subject to certain conditions that the Court will impose, the Court will order UMCP to permit the October 7 event to go forward….

Several Supreme Court precedents related to free speech on campus are relevant. See Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) (speech can only be prohibited if it is directed to incite or produce imminent lawless action, and is "likely to incite or produce such action"); Hess v. Indiana (1973) (anti-war protesters at university yelled, "We'll take the fucking street later"; conviction overturned because speech not directed at particular person or persons and unlikely to "produce[] imminent disorder"); Healy v. James (1972) (state college could not deny recognition of anti-war group based on group's association with national organization and fear of disruption on campus); Snyder v. Phelps (2011) (family could not sue for emotional distress where individuals on public property picketed soldier's funeral because "speech was at a public place on a matter of public concern … [and] entitled to 'special protection' under the First Amendment"); Saxe v. State Coll. Area Sch. Dist. (3d Cir. 2001) ("There is no 'categorical harassment' exception to the First Amendment's free speech clause.")….

The Court recognizes that the University has compelling interests in maintaining campus safety and carrying out its educational mission; however, the decision to deny University student organizations permission to sponsor expressive events on October 7 was not narrowly tailored to address those concerns. The Constitution protects even what many would deem despicable speech. See Snyder v. Phelps [upholding Westboro Baptist Church's right to picket near a military funeral, with signs saying, for instance, {"God Hates the USA/Thank God for 9/11," "America is Doomed," "Don't Pray for the USA," "Thank God for IEDs," "Thank God for Dead Soldiers," "Pope in Hell," "Priests Rape Boys," "God Hates Fags," "You're Going to Hell," and "God Hates You"}]. "'[T]he point of all speech protection … is to shield just those choices of content that in someone's eyes are misguided, or even hurtful.'" Even if outrageous words cause pain, "we cannot react to that pain by punishing the speaker. As a Nation we have chosen a different course—to protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate."

Testimony at the hearing established that UMCP indeed did have reasonable alternatives to an entire ban on expressive speech on October 7. UMCP could, for example, arrange to employ extra security personnel, rely on the assistance of local and state police, install temporary metal detectors, erect fencing for crowd control, and check student identification….

[E]ven if pro-Israel groups see October 7 as somehow sacrosanct, it is at least fair argument for pro-Palestine groups to see the date as sacrosanct as well, symbolic of what they believe is Palestine's longstanding fight for the liberation of Gaza. The facts remain—SJP chose the October 7 date, complied with the reservation process, obtained the University's preliminary approval for the date, and then had the approval abruptly taken away. No other date, as SJP sees it, can make the point of their mission quite as forcefully as October 7; to SJP, it is unique….

Allowing that SJP may engage in speech that is protected, controversial though it may be, and despite SJP's claim that only 25 to 50 students will attend, it remains entirely plausible that the University may need to beef up its security personnel (and perhaps seek the assistance of regular law enforcement) in order to maintain order during the protests, as well as to arrange for appropriate personnel to monitor any substantial inflow of non-student protestors and in general to keep the crowd under control. {At the hearing, SJP did not provide a convincing argument that the event would be or, practically speaking, could be limited to 25 to 50 students. It bears noting that USM policy specifically allows student-event holders to invite outside participants.} It simply cannot be said with assurance that personal threats, violence, and property damage as a result of campus protests involving Gaza, given recent experience around the country, will not occur. But, as stated before, there are less restrictive alternatives to meet these potential challenges short of suppressing expressive conduct under the First Amendment….

Summing up, while speech and slogans by SJP will be permitted on October 7, any negative conduct not protected by the First Amendment will not be—including any incitement to imminent violence, physical or verbal threats, impeding access of any students to class or buildings, property damage of any sort, the occupation of buildings, encampments, and, in general, defiance of reasonable crowd control measures employed by security personnel. Violators may be subject to arrest and/or ouster from the campus. The University's policy requirements with respect to campus events as they presently stand will apply in full.

{The same liability for negative conduct not protected by the First Amendment would apply to any counter-protestors who might attend the October 7 event. Moreover, free speech does not mean hecklers have the right to shut down campus debate; they do not have a so-called "heckler's veto."}

The court enjoined the ban on Oct. 7 events only as to the University of Maryland College Park campus, presumably because it was the only venue that the court viewed the plaintiffs as having properly complained about.

SJP is represent by Gadeir F. Abbas & Lena F. Masri (CAIR), Radhika Sainath (Palestine Legal), and Victoria Porell. Note that the court heavily relies on the work of our recent guest-blogger Prof. Cass Sunstein.

The post "[T]his Is a Matter of Law, Not of Wounded Feelings": Univ. of Maryland May Not Ban All Oct. 7 Demonstrations … appeared first on Reason.com.

[Paul Cassell] Glossip v. Oklahoma: The Story Behind How a Death Row Inmate and the Oklahoma A.G. Concocted a Phantom "Brady Violation" and Got Supreme Court Review (Part II)

In yesterday's post, I discussed Glossip v. Oklahoma—a case that the Supreme Court will hear next Wednesday about allegations that prosecutors withheld evidence in a death penalty trial. In that post, I reviewed my amicus brief for the murder victim's family, which contains extensive documentation proving that the prosecutors never withheld any evidence. In this second post, I discuss Glossip's and Oklahoma's (non)responses to the facts that I presented. The parties' failure to respond confirms that their Brady claim is concocted and that they are forcing the victim's family to endure frivolous litigation. Tomorrow, in my third and final post, I will explain why courts should be cautious before accepting an apparently politically motivated confession of "error" from a prosecutor.

In Glossip, the underlying question before the Supreme Court concerns whether state prosecutors withheld evidence from Glossip's defense team before his 2004 trial. In that trial, Glossip was found guilty of commissioning his friend, Justin Sneed, to murder Barry Van Treese. Glossip was sentenced to death. Now, nearly two decades later, Glossip argues that newly released notes from the prosecutors show that they withheld information about Sneed's lithium usage and treatment by a psychiatrist. And, curiously, Oklahoma Attorney General Gertner Drummond agrees. Drummond has joined Glossip in asking the Supreme Court to overturn the conviction and capital sentence.

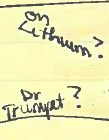

As I reviewed yesterday, Glossip's and General Drummond's argument rests primarily on four handwritten words in prosecutor Smothermon's notes:

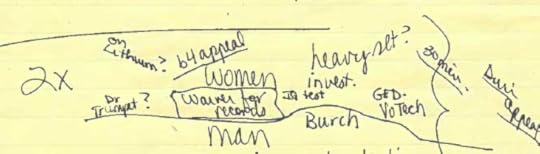

According to Glossip and General Drummond, these few words "confirm" Smothermon's knowledge of Sneed's treatment for a psychiatric condition by lithium by a "Dr. Trumpet" (later claimed to be a Dr. Trombka). But stepping back and reading the notes in context reveals a much different interpetation. Here are Smothermon's notes surrounding the four words in question:

In yesterday's post, I explained that looking at all of her notes reveals that Sneed was merely recounting what the defense team was questioning him about—not what the prosecutors had discovered. The defense team interview is reflected in the reference to "2x" (two interviews), including one by "women" that was "b4 [the] appeal" who were an "invest[igator]" and a person involved in the "appeal."

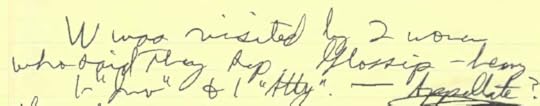

To the extent any question remains, the corresponding notes from the other prosecutor at the interview (Gary Ackley) show even more directly that Sneed was simply recounting a defense interview. The first line of Ackley's notes from the Sneed interview reads "W was visited by 2 women who said they rep[resented] Glossip—heavy—1 "inv" & 1 "Atty" Appellate?" Read for yourself:

As I pointed out yesterday, if the prosecutors' notes record what happened during a defense interview, obviously no Brady violation could exist. Because the prosecutors were simply recording what a state's witness recounted about questions asked of him by the defense team, the notes cannot contain information withheld from the defense.

In today's post, I review Glossip's and General Drummond's failure to respond to these facts. As with yesterday's post, today's post summarizes my amicus brief and also additional factual material contained in an appendix to my brief (linked here as a single document).

Glossip and General Drummond contend that the four words in the notes mean that the prosecutors possessed information that they should have disclosed to the defense. My contrary interpretation prompts the obvious question of what do the prosecutors say their own notes mean. The authors' explanation of what their own handwriting means would seem to be at least relevant to the discussion. But, surprisingly, General Drummond has not even asked the prosecutors what their notes mean.

Here's the story of behind Drummond's remarkable lack of curiosity:

Shortly after assuming office in January 2023, and perhaps sensing political advantage, General Drummond ordered an investigation into Glossip's conviction by an allegedly "independent" investigator, Rex Duncan. Duncan, its turned out, was a lifelong friend and political supporter of Drummond. General Drummond paid Duncan handsomely to produce a report on the case. But Duncan's report relied almost completely on an earlier report from the anti-death penalty law firm, Reed Smith. Duncan actually cut and pasted sections from the Reed Smith report directly into his.

In preparing his report, Duncan interviewed Smothermon twice. But Duncan never substantively explored what her notes meant. First, on March 15, 2023, Duncan spoke to Smothermon for about thirty minutes. During that interview, Duncan did not ask Smothermon about the notes in question, as confirmed by an email Smothermon immediately sent to the Attorney General's Office.

Second, on the next day, March 16, 2023, Duncan briefly called Smothermon back. During that three-minute call, Duncan conveyed an interpretation of the notes provided by Reed Smith. Duncan asked Smothermon about a reference in her notes to a "Dr. Trumpet." Smothermon then asked to see the note in question, which she had written about two decades earlier. Duncan responded there was "no need" and quickly ended the call. The entire call took about only three minutes. Smothermon then sent another contemporaneous email to the A.G.'s Office, memorializing that this call was abbreviated and non-substantive.

Since then, General Drummond has been asked (at least) three times to talk to Smothermon and Ackley about what their notes really mean—but he has obstinately refused. First, in May 2023, prosecutors at an Oklahoma District Attorney's Association (ODDA) meeting asked General Drummond personally to talk to the two prosecutors about their notes. ODDA prosecutors told Drummond that because he had never spoken with Smothermon or Ackley, he could not know what their notes meant. Drummond reportedly responded: "I accept that criticism." Drummond was also told that if he spoke with Smothermon, he would learned that her notes were about what Sneed remembered about his meetings with defense attorneys. Drummond did not respond to this concern.

Second, on behalf of my pro bono clients (the Van Treese family), in a telephone call with General Drummond on May 24, 2023, and a follow-up letter the next day, I said that Drummond should talk to Smothermon and Ackley about the true meaning of their notes. See May 25, 2023 Letter at 2 ("I believe that if you talk to the prosecutors who took the notes (Connie Smothermon and Gary Ackley), you will be able to quickly confirm that the notes recount what the defense knew—not what prosecutors knew."). Drummond's response to me (contained in the link above) ducked the subject. In the sixteen months since, Drummond has not followed up my suggestion that he go to the source of the notes.

And third, Smothermon herself has contacted the Attorney General's Office and asked the Office to review the notes with her. General Drummond's Office has declined.

In sum, despite repeated requests, the General Drummond has not discussed with the prosecutors their notes, much less attempted to discuss what is apparent from their face—e.g., that the notes merely describe what happened when Sneed was "visited by 2 women who said that they rep[resented] Glossip." Against this backdrop, the reasonable conclusion is that Drummond is not seeking to determine what the prosecutors' notes really mean. Instead, he remains willfully blind to the facts.

After I filed my amicus brief pointing all this out to the Supreme Court, General Drummond filed a reply brief. But he did not respond specifically to my arguments, including my detailed examination of the text of the notes in question. Instead, all that Drummond said was that my brief "offer[ed] alternative explanations for the notes by reference to extra-record materials." (Okla. Reply at 9)

General Drummond's reply is deceptive. First, as explained this post above and in my post yesterday, my brief offered an "alternative explanation" to Drummond's reading of prosecutor Smothermon's notes based on the notes' text. For example, the notes refer to "on lithium?" and "Dr[.] Trumpet?" Drummond omits the two question marks from his brief, which obviously suggest lack of certainty and point to Sneed being asked questions. Drummond also fails to explain who the "women" in the notes might be … other than the two women on the defense team who I have identified. And clearly these notes are in the record—they are the very notes that Drummond claims constitute grounds for reversal.

Second, General Drummond never discusses the parallel, confirming notes taken by prosecutor Ackley, who was seated next to prosecutor Smothermon during the Sneed interview. Drummond does not deny that the notes I presented to the Supreme Court are, in fact, Ackley's notes. Instead, Drummond apparently takes the position that Ackley's notes are "extra-record materials"—a convenient omission from the record, because it was Drummond himself chose to leave them out! And in any event, when it is now clear that Ackley's notes are highly relevant to the issue pending before the Court, why doesn't Drummond admit that he possesses in his Office's files parallel notes fully confirming my interpretation of Smothermon's notes?

It turns out that General Drummond has included at least part of Ackley's notes in the record. (JA939, discussed in my brief at 11 n.6). Accordingly, it is appropriate for the Supreme Court to look at the rest of Ackley's notes under the doctrine of completeness, recognized in both federal law (Federal Rule of Evidence 106) and state law (Okla. Stat. tit. 12 § 1207).

In addition to ignoring the notes' text, General Drummond fails to discuss what the prosecutors themselves say their handwritten notes mean. Drummond seem to think it is enough to say that the prosecutors' interpretation is "extra-record"—which is just another way of saying that he has contrived to remain willfully blind to avoid learning what the two prosecutors say their own scrawled notes mean. The Supreme Court has granted certiorari to review Glossip's and General Drummond's claim that the prosecutors' notes reflect information that the prosecutors knew and intentionally withhold from the defense. It is extremely odd to have an entire case move forward without Drummond and Glossip even telling the Court what the prosecutors themselves say their writing means.

As recounted in my amicus brief, the prosecutors say that their notes mean exactly what their text indicates. Smothermon says her notes recorded that Sneed was recounting what defense team members were asking him:

Sneed answered "2X" to my question of whether anyone else had spoken to him which was my usual question at the conclusion of an interview with an in-custody witness. Sneed told us … [t]he first visit was from two women before his appeal (of his first conviction). One he described as heavyset investigator. They asked him to sign a waiver for records—IQ test, GED, VoTech, and asked him questions about lithium and Dr. Trumpet. The question marks after those two words indicate that the women asked him those questions.

And Ackley likewise says that his notes reflect Sneed was recounting a defense interview:

[My] notes reflect that Sneed (W-witness) was visited by 2 women who said they represented Glossip, one was heavy, an investigator and one was an attorney. I noted appellate as a thought to the identity of the visitors. Sneed said the visit lasted about 30-40 minutes. They asked Sneed to sign a waiver so they could review his records regarding IQ tests, GED, etc. With an arrow, I noted Sneed said "on lithium when administered" regarding the visitor's questions about IQ testing.

In sum, General Drummond is asking the Supreme Court to reverse a murder conviction and death sentence based on an interpretation of four words in one prosecutor's notes. But Drummond ignores the true facts of the case established by surrounding context.

Glossip also had the opportunity to reply to my interpreation of the notes. But, like Drummond, Glossip fails to engage on the key facts. Notably, Glossip never denies the critical point (discussed in my post yesterday) that on April 16, 2001, two women on his defense team interviewed Sneed. If so, it would appear that Glossip has an ethical obligation to tell the Supreme Court what information his defense team learned through that interview and related investigation. And yet one can read Glossip's brief without finding any discussion of his own defense team's interview of Sneed—an interview in which the defense team asked Sneed about lithium and Dr. Trumpet.

In his reply brief, Glossip briefly refers to my presentation of Smothermon's interpretation of her own notes. Glossip disparages her interpretation "as unsworn hearsay manufactured for an amicus brief." (Glossip Reply. at 5). But why hasn't Glossip (or General Drummond) asked her to explain her notes. Glossip briefly refers to the interview of Smothermon by Rex Duncan (discussed above). But it is apparently undisputed that, during that inconclusive three-minute interview, Smothermon asked to see her notes to interpret them, and Duncan replied there was "no need."

Glossip's team has also recently interviewed Ackley. But that interview apparently steered clear of the fact that Ackley was just memorializing Sneed's recounting defense team questioning. As with General Drummond, Glossip entirely ignores the fact that co-prosecutor Ackley's notes interlock with Smothermon's and make clear that Sneed was recounting being "visited by 2 women who said they rep[resented] Glossip"—i.e., what the defense team knew.

In addition, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals declined to order an evidentiary hearing on what the prosecutors' notes mean. In rejecting Glossip's claims, the OCCA held:

This Court has thoroughly examined Glossip's case from the initial direct appeal to this date. We have examined the trial transcripts, briefs, and every allegation Glossip has made since his conviction. Glossip has exhausted every avenue and we have found no legal or factual ground which would require relief in this case. Glossip's application for post-conviction relief is denied. We find, therefore, that neither an evidentiary hearing nor discovery is warranted in this case.

In his certiorari petition to the U.S. Supreme Court, Glossip declined to challenge the OCCA's decision not to order an evidentiary hearing. Of course, in any evidentiary hearing about the notes, Glossip would have to explain exactly what his defense team knew about Sneed before the trial—a subject that he has avoided discussing.

In sum, Glossip is asking the Supreme Court to overturn his death sentence based on a concocted interpretation of the prosecutors' notes that ignores their plain meaning. It is gobsmacking that he has gotten so far with so little. And, as a result of Glossip extending his frivolous litigation, the victim's family continues to wait for his sentence to be carried out … 10,128 days after Glossip commissioned the murder of Barry Van Treese.

In tomorrow's final post, I discuss how courts should handle non-adversarial litigation, such as this one—where Glossip and General Drummond are working hand-in-hand to keep the Supreme Court from learning the truth.

The post Glossip v. Oklahoma: The Story Behind How a Death Row Inmate and the Oklahoma A.G. Concocted a Phantom "Brady Violation" and Got Supreme Court Review (Part II) appeared first on Reason.com.

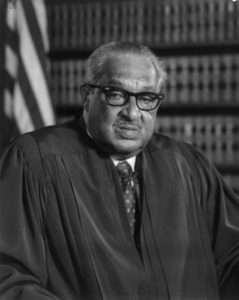

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 2, 1967

10/2/1967: Justice Thurgood Marshall takes the oath.

Justice Thurgood Marshall

Justice Thurgood MarshallThe post Today in Supreme Court History: October 2, 1967 appeared first on Reason.com.

October 1, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Tuesday Media Recommendations: General Fiction (not Historical, SF, Fantasy, Mystery, or Detective)

UPDATE: I had originally said "general literature," and many readers interpreted that as including nonfiction. I've updated this to "general fiction"; I'll have a query for nonfiction next week.

The post Tuesday Media Recommendations: General Fiction (not Historical, SF, Fantasy, Mystery, or Detective) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Stephen Halbrook] Second Amendment Roundup: ATF's Wish to Trace More Firearms Doesn't Justify Redefining "Firearm"

ATF declares that its Final Rule at issue before the Supreme Court in Garland v. VanDerStok "will enhance public safety by helping to ensure that more firearms may be traced by law enforcement to solve crime and arrest the perpetrators." Radically expanding the definition of "firearm" from what Congress enacted is allegedly justified by the policy argument that the agency will be able to "trace" more firearms. Whether that will solve more crimes is a big "if."

We're all familiar with the spiel. A criminal leaves his gun at a "crime scene" (how often does that happen?) but gets away, unidentified. Police find the gun and ask ATF to trace it. The gun is engraved with the manufacturer's name and serial number. ATF starts with the manufacturer and, using the records kept by federal licensees, traces the gun to its retail purchaser. And voilà, the criminal is identified and arrested.

But now the sky is falling. ATF insists that its Final Rule is the Ghost Buster for "ghost guns," a propaganda term used to describe privately-made firearms. Unless the kits from which hobbyists make their own guns are declared to be "firearms," their homemade guns won't be traceable. Criminals who lose their guns at "crime scenes" won't be caught.

After years of ATF exaggerating the usefulness of tracing, Congress enacted a law in 2013 requiring ATF to "make clear that trace data cannot be used to draw broad conclusions about firearms-related crime" by including in its releases of information the following language: "Law enforcement agencies may request firearms traces for any reason, and those reasons are not necessarily reported to the Federal Government. Not all firearms used in crime are traced and not all firearms traced are used in crime."

Consider the disconnect. ATF traces all firearms it encounters. A person is subject to a domestic violence restraining order and ATF learns that he has a very large gun collection. They raid his house, seize all 200 of his guns, and then trace them. That goes down as 200 "crime guns" seized at a "crime scene" that have nothing to do with his offense of mere possession while subject to the order.

As explained in my two previous posts (here and here), Congress defines a "firearm" as a weapon "which will or is designed to or may readily be converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive" or "the frame or receiver of any such weapon." ATF's Final Rule expands that definition to include partially-machined raw material, information, jigs, and tools that sufficiently-skilled persons may fabricate into a firearm. Whether ATF has such authority is the issue before the Court in VanDerStok.

One of the superior amici briefs filed in the case is that of the Citizens Committee for the Right to Keep and Bear Arms, authored by Dan Peterson and C. D. Michel. I'll cover some of the highlights in that brief and offer some additional material in the following remarks.

Only licensed manufacturers and importers who are "engaged in the business" are required by the Gun Control Act (GCA) to identify and serialize firearms. 18 U.S.C. § 923(i). Hobbyists are free lawfully to craft their own guns without these requirements. ATF claims that the resultant "ghost guns" cannot be traced, thus requiring the non-gun materials that hobbyists use to make guns be redefined as guns.

But the GCA, as amended by the Firearm Owners' Protection Act, sharply delineates licensees from private individuals. While ATF may inspect licensed dealer records "in the course of a bona fide criminal investigation," it is prohibited from establishing "any system of registration of firearms, firearms owners, or firearms transactions." 18 U.S.C. §§ 923(g) & 926(a).

Nevertheless, ATF has been on a crusade to trace all firearms that law enforcement encounters, and its attack on privately-made firearms is only the latest stage in this endeavor. The Final Rule, ATF urges, is necessary to address an "urgent public safety and law enforcement crisis posed by the exponential rise of untraceable firearms commonly called 'ghost guns.'"

Let's test this claim with reality. New Jersey is one of the states that traces every firearm it encounters, to include the .22 rifle a widow abandons at a police station. Not exactly a crime scene.

In 2022, New Jersey criminalized the purchase of a parts kit not made by a licensed manufacturer with a serial number. ATF trace data for New Jersey that same year shows 5,248 firearm traces, of which 3,824 – 73% – were for "possession of weapon" and "found firearm." Keep in mind that the Garden State makes possession per se without the right papers a crime. How many of these were privately-made firearms? Only 67 traces were for "homicide" and 132 for "aggravated assault." As to firearms seized from the possessor, how did tracing solve any crime?

The Citizens Committee brief goes on point by point in explaining why tracing isn't what it's cut out to be and how meaningless is the supposed data on "ghost guns." First, a trace only leads to the first retail purchaser, if that person can be located. Without evidence, no reason exists to consider that person a "suspect" in whatever the crime is. And after that first purchase, the gun may have been inherited, given as a gift, sold, lost, or stolen.

Second, criminals don't typically buy guns from a licensed dealer, and thus their acquisitions cannot be traced. Where do criminals get their guns? Out of 24,848 prison inmates surveyed, a Bureau of Justice Statistics study Source and Use of Firearms Involved in Crimes (2019) reported:

Off the street/underground market: 43.2%

Obtained from individual: 25.3%

Theft: 6.4%

Purchased/traded at retail source: 10.1% [only 6.9% under one's real name]

Other sources: 17.4%

The study made no mention of any of the firearms being made from kits. Multiple studies of the sources from which criminals get their guns, going back to the 1980s, report similar results.

Third, evidence does not support the government's argument of an "urgent public safety and law enforcement crisis posed by the exponential rise of untraceable firearms…." Let's compare some numbers. There are an estimated 500 million firearms in private hands in the United States. The types of kits that hobbyists most often make into firearms are for AR-15 rifle types and handguns similar to Glocks. ATF data shows that about two and a half million Glocks were introduced into commerce between 2016 and 2022. According to the National Shooting Sports Association, there were 24 million+ modern sporting rifles (mostly AR-types) in American civilian circulation as of 2020.

Compare those numbers with the 19,000 privately-made firearms alleged to have been traced in 2021. That's hardly a drop in the bucket. And consider this further finding by Congress in the 2013 law cited above: "Firearms selected for tracing are not chosen for purposes of determining which types, makes, or models of firearms are used for illicit purposes. The firearms selected do not constitute a random sample and should not be considered representative of the larger universe of all firearms used by criminals, or any subset of that universe."

Other than the numbers of privately-made firearms traced, no information exists as to why they were traced. ATF has raided companies that market kits and presumably seized their inventory, which could jack-up the statistics dramatically. Eleven states and the District of Columbia restrict privately-made firearms, so traces generated in those places may reflect mere possessory offenses.

Based on unverified media accounts, Everytown for Gun Safety Foundation lists 187 alleged "shootings" with "ghost guns" between 2013 and 2024, for an average of about 15 per year. But the data include accidents and suicides, not just assaults. In any event, 15 shootings per year are a miniscule fraction of the tens of thousands of traces of "ghost guns" now being reported by ATF annually.

This is not the first time ATF has manipulated trace data for political ends. In the 1990s, in order to justify a ban on "assault weapons," it was charged with creating the impression that criminals prefer them. Its Forward Tracing Program entailed getting information from manufacturers on the subject firearms and "tracing" them to the retail dealers. Then they told the public that the designated firearms were disproportionately used in crime based on them being traced so much. I document this cooking of the books in America's Rifle, chapter 14.

It goes without saying that the issue before the Supreme Court in VanDerStok is purely legal: does ATF have authority to expand the definition of "firearm" enacted by Congress and thereby to criminalize activity that Congress did not make unlawful? Contrary to government claims, there is no "urgent public safety and law enforcement crisis posed by the exponential rise of untraceable firearms…." But even if there is, it's a matter for Congress, not the agency, to address.

The post Second Amendment Roundup: ATF's Wish to Trace More Firearms Doesn't Justify Redefining "Firearm" appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers