Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 255

October 1, 2024

[Josh Blackman] New Eleventh Circuit Amicus Brief In Special Counsel Appeal

Today our team submitted an amicus brief in United States v. Trump before the Eleventh Circuit. This case is an appeal from Judge Cannon's decision declaring the appointment of the Special Counsel to be unlawful. Our brief was filed on behalf of Robert Ray, Professor Seth Barrett Tillman, and the Landmark Legal Foundation. We are grateful to Michael A. Sasso for serving as local counsel.

Tillman and Landmark joined our District Court brief. We are honored that Ray joined our effort on appeal. Ray served as one of the last Independent Counsels, replacing Kenneth W. Starr in October 1999, and was in charge of the Whitewater and Monica Lewinsky investigations. He concluded the investigations by March 2002 with the decision not to prosecute President Clinton once he left office.

Our brief makes four primary arguments:

The District Court correctly dismissed the indictment. Amici advance four rationales to support the judgment below.

First, from the 1850s through the 1950s, during six presidential administrations, Attorneys General retained outside lawyers as Special Counsels either: to assist a U.S. Attorney with prosecutions, or to assist the Attorney General with an investigation. Josh Blackman, A Historical Record of Special Counsels Before Watergate (2024), https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4970972 (hereinafter"A Historical Record"). And the Watergate Special Prosecutor is a thin reed to stand on. United States v. Nixon expressly and repeatedly recognized that the Watergate Special Prosecutor had "unique authority and tenure." 418 U.S. 683, 694 (1974). Further, in 1973, the Acting Attorney General, with the acquiescence of the President, granted the Special Prosecutor unsurpassed insulation against removal. Apart from those compromises, this insulation would be inconsistent with Bowsher v. Synar. 478 U.S. 714 (1986). Whether the Nixon analysis is holding or dicta, it is not controlling, and it should not be extended to today's context under today's statutory and regulatory framework.

Second, Special Counsel Jack Smith ("Smith") cannot rely on the permanent indefinite appropriation found in a "note" to 28 U.S.C. §591. In 2004, the Government Accountability Office determined that this appropriation can be used for "investigat[ing] and prosecut[ing] high ranking government officials." GAO, Special Counsel and Permanent Indefinite Appropriation, B-302582, 2004 WL 2213560, at *4 (Comp. Gen. Sept. 30, 2004). But Trump was not a "high ranking" official when he was indicted, and all the alleged conduct took place after he was out of office. In these circumstances, the funding mechanism in Section 591's note cannot be used to pay Smith.

Third, Supreme Court precedent distinguishes between officers and employees. An "Officer of the United States" position must have a duration that is continuous. Though Smith's prosecution has already continued for several years, and his duties are regular, his position is not continuous, because his extant position would not continue to a successor. Morrison v. Olson, 487 U.S. 654, 672 (1988). At most, Smith is a mere "employee" who cannot exercise the sweeping powers of a Senate-confirmed U.S. Attorney.

Finally, Amici have properly preserved for review by the Supreme Court the question of whether Morrison v. Olson should be overruled.

The Special Counsel, like the Independent Counsel, still comes as a wolf. Id. at 699 (Scalia, J., dissenting).

We look forward to this litigation proceeding.

The post New Eleventh Circuit Amicus Brief In Special Counsel Appeal appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] New Article: A Historical Record of Special Counsels Before Watergate

I have posted to SSRN a new article titled, A Historical Record of Special Counsels Before Watergate. This Article is based on some extensive research into more than a dozen different archives. This Article is also relevant to the ongoing litigation over the Special Counsel, which I will address shortly.

Here is the abstract:

This Article presents a corpus of primary sources that were written by Presidents, Attorneys General, United States Attorneys, Special Counsels, and others between the 1850s and the 1950s. This corpus reproduces primary sources from more than a dozen archives to present a better legal account showing how Special Counsels were retained by Attorneys General under Presidents Buchanan, Andrew Johnson, Grant, Garfield, Theodore Roosevelt, and Truman.

During these six presidential administrations, Attorneys General retained outside lawyers as Special Counsels either: (1) to assist a U.S. Attorney with prosecutions, or (2) to assist the Attorney General with an investigation. In none of these matters did the Attorney General appoint an outside lawyer as a Special Counsel, and then delegate to him the powers now claimed by modern special counsels: all of the powers of a Senate-confirmed U.S. Attorney.

There was one outlier. In 1924, during the Coolidge Administration, Congress enacted legislation establishing Senate-confirmed special counsels to prosecute Teapot Dome Scandal defendants. These Special Counsels were afforded "total independence." It is doubtful that these positions would be consistent with the Supreme Court's modern separation of powers jurisprudence.

This practice shows that the positions of special counsels in the post-Watergate era are not analogous to the positions of special counsels in the pre-Watergate era. Thus pre-Watergate history does not provide support for the modern, post-Watergate special counsel and the vast powers that they are purportedly vested with.

I welcome comments and feedback!

The post New Article: A Historical Record of Special Counsels Before Watergate appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Draft Chapters on Education and Corporate Law for the Forthcoming Routledge Handbook of Classical Liberalism

I previously posted about my draft chapter on "Land-Use Regulation" for the forthcoming forthcoming Routledge Handbook on Classical Liberalism (edited by Richard Epstein, Liya Palagashvili, and Mario Rizzo). It is now available on SSRN. Two other draft chapters for this book are also now up on SSRN: "Education," by Williamson Evers (Director of the Center on Educational Excellence at the Independent Institute), and "Classical Liberalism and Corporate Law," by Robert T. Miller (University of Iowa).

Here's the abstract for the education chapter:

This chapter contends that classical liberal reform of K–12 and higher education would restore liberty and efficacy to all participants. It discusses the pros and cons of public and private provision of K–12 education. It describes the movement from highly local control to increased centralization. The article discusses how the organizational format of K–12 education came about historically, with particular emphasis on the influence of millennialism and its secular successor Progressivism. It shows that Progressivism in educational policy was also influenced by the example of Prussia. The chapter describes teacher-union power and discusses in particular the cases of African American education and Catholic schools. It examines the classical liberal K–12 reforms of pluralism, demonopolization, and parental choice.

Section 3 lays out higher education's array of subsidies and its poor incentive structure. The government is quite often inserted between colleges and students. As with K–12 education, the chapter discusses how the institutional organization of higher education came about historically. It relates what classical liberals have said about professorial tenure. It portrays the increasingly illiberal milieu in institutions of higher learning. The section proposes removing direct subsidies and relying mainly on student tuition payments.

The chapter offers a great overview of both libertarian/classical liberal critiques of conventional government-controlled education, and internal disagreements among libertarians over education policy (e.g.—between those who advocate total privatization and those who support state-subsidized school vouchers). If you want a relatively short but thorough summary of libertarian perspectives on education, this is the place to go.

If I have a reservation, it's that I wish the author had paid more attention to the argument that government control and/or funding of education is needed to increase voters' political knowledge. Voter knowledge of government and public policy is a public good that the market is likely to underprovide. This is an important standard rationale for state intervention in education. I offer some reservations about it in Chapter 7 of my book Democracy and Political Ignorance, and in a more recent book chapter. But the topic is, I think, due for a more extensive reconsideration.

I cannot say much about the corporate law chapter, because it is too far removed my areas of expertise. But it seems a valuable overview of its topic, as well.

The post Draft Chapters on Education and Corporate Law for the Forthcoming Routledge Handbook of Classical Liberalism appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "AI, Society, and Democracy: Just Relax"

I wanted to specially note this Digitalist Papers essay by my Hoover colleague, economist (indeed, Grumpy Economist) John Cochrane; I'm somewhat more worried than he is, but I thought his perspective was interesting and worth noting. Here's the Conclusion:

As a concrete example of the kind of thinking I argue against, Daron Acemoglu writes,

We must remember that existing social and economic relations are exceedingly complex. When they are disrupted, all kinds of unforeseen consequences can follow…

We urgently need to pay greater attention to how the next wave of disruptive innovation could affect our social, democratic, and civic institutions. Getting the most out of creative destruction requires a proper balance between pro-innovation public policies and democratic input. If we leave it to tech entrepreneurs to safeguard our institutions, we risk more destruction than we bargained for….

The first paragraph is correct. But the logical implication is the converse—if relations are "complex" and consequences "unforeseen," the machinery of our political and regulatory state is incapable of doing anything about it. The second paragraph epitomizes the fuzzy thinking of passive voice. Who is this "we"? How much more "attention" can AI get than the mass of speculation in which we (this time I mean literally we) are engaged? Who does this "getting"?

Who is to determine "proper balance"? Balancing "pro-innovation public policies and democratic input" is Orwellianly autocratic. Our task was to save democracy, not to "balance" democracy against "public policies." Is not the effect of most "public policy" precisely to slow down innovation in order to preserve the status quo? "We" not "leav[ing] it to tech entrepreneurs" means a radical appropriation of property rights and rule of law.

What's the alternative? Of course AI is not perfectly safe. Of course it will lead to radical changes, most for the better but not all. Of course it will affect society and our political system, in complex, disruptive, and unforeseen ways. How will we adapt? How will we strengthen democracy, if we get around to wanting to strengthen democracy rather than the current project of tearing it apart?

The answer is straightforward: As we always have. Competition. The government must enforce rule of law, not the tyranny of the regulator. Trust democracy, not paternalistic aristocracy—rule by independent, unaccountable, self-styled technocrats, insulated from the democratic political process. Remain a government of rights, not of permissions. Trust and strengthen our institutions, including all of civil society, media, and academia, not just federal regulatory agencies, to detect and remedy problems as they occur. Relax. It's going to be great.

The post "AI, Society, and Democracy: Just Relax" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] 5 Years in Prison for "Concealing Material Support to Hamas"

From a Justice Department statement yesterday (all redactions in original)

A Somerset County, New Jersey, man was sentenced today to time served—64 months—for concealing his attempts to provide material support to Hamas …. Jonathan Xie, 25, of Basking Ridge, New Jersey, previously pleaded guilty ….

According to documents filed in this case and statements made in court:

Xie knowingly concealed and disguised the nature, location, source, ownership and control of his attempt to provide material support and resources to Harakat alMuqawamah al-Islamiyya and the Islamic Resistance Movement, an organization that is commonly referred to as Hamas. Xie admitted that he knew Hamas was a designated foreign terrorist organization and has engaged in terrorist activities. He said he attempted to conceal his attempted support believing it would be used to commit or assist in the commission of a violent act.

In December 2018, Xie sent $100 via Moneygram to an individual in Gaza who Xie believed to be a member of the Al-Qassam Brigades—a faction of Hamas that has conducted attacks, to include suicide bombings against civilian targets inside Israel. At approximately the same time that Xie sent the money, he posted on his Instagram account "Just donated $100 to Hamas. Pretty sure it was illegal but I don't give a damn."

In April 2019, Xie appeared in an Instagram Live video wearing a black ski mask and stated that he was against Zionism and the neo-liberal establishment. When asked by another participant in the video if he would go to Gaza and join Hamas, Xie stated "yes, If I could find a way." Later in the video, Xie displayed a Hamas flag and retrieved a handgun. He then stated "I'm gonna go to the [expletive] pro-Israel march and I'm going to shoot everybody."

In subsequent Instagram posts, Xie stated, "I want to shoot the pro-israel demonstrators … you can get a gun and shoot your way through or use a vehicle and ram people … all you need is a gun or vehicle to go on a rampage … I do not care if security forces come after me, they will have to put a bullet in my head to stop me."

In April 2019, Xie sent a link to a website for the Al-Qassam Brigades to an FBI employee who was acting online in an undercover capacity. Xie described the website as a "Hamas" website and stated he had previously sent a donation to the group. Xie then sent screenshots of the website to the undercover employee and demonstrated how to use a new feature on the website that allows donations to be sent via Bitcoin. On April 18, 2019, when the undercover employee asked whether Bitcoin was anonymous, Xie responded: "yah… i think thats why hamas is using it now because money transfer is not that anonymous." …

The criminal complaint against Xie (which has more detailed information about the allegations) was filed in May 2019; the plea agreement was signed in June 2020; the docket doesn't directly explain why there was the delay between the plea and sentencing, but this November 2022 order notes that Xie was planning to rely on "certain expert psychological and neurological reports."

The post 5 Years in Prison for "Concealing Material Support to Hamas" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Paul Cassell] Glossip v. Oklahoma: The Story Behind How a Death Row Inmate and the Oklahoma A.G. Concocted a Phantom "Brady Violation" and Got Supreme Court Review (Part I)

Next week the Supreme Court will hear oral argument in Glossip v. Oklahoma. Death row inmate Glossip claims that the prosecutors at his murder trial withheld evidence from him. In a curious twist, the State of Oklahoma has reversed its long-held position supporting Glossip's conviction and now joins Glossip. I have filed an amicus brief for the murder victim's family, presenting important facts about the case the parties have concealed from the Court. In this three-part series, I review the true facts of the case. Working together, Glossip and Oklahoma have concocted a phantom denial of evidence. In fact, the prosecutors never withheld any evidence from the defense. The Supreme Court should rapidly affirm the lower court's decision upholding Glossip's conviction and death sentence—and help bring the victim's family closer to closure after more than two decades of litigation.

In this first post, I demonstrate that the alleged violation of Brady v. Maryland (requiring the State to provide exculpatory evidence to a defendant) simply never happened. The evidence that Glossip alleges prosecutors withheld was, in fact, fully known to the defense, as my amicus brief explains. Tomorrow, in the second post, I will review Glossip's and Oklahoma's (non)responses to this decisive point. Their silence in briefing before the Court is powerful support for my position. Finally, in the last post, I draw some broader conclusions about non-adversarial litigation such as this one. This case presents a cautionary tale about the dangers of courts simply accepting an elected prosecutor's confession of "error," which may be politically motivated.

The story begins on January 7, 1997, when authorities found the slain body of Barry Van Treese in a motel located in Oklahoma City that he owned. Van Treese had been missing for several hours that day. The subsequent search for Van Treese consumed everyone associated with the motel … everyone, that is, except Richard Glossip.

Glossip managed the motel and had allowed it to fall into disrepair in the latter months of 1996. Additionally, Van Treese and his wife, Donna, suspected that Glossip was embezzling money. Van Treese had planned on confronting Glossip about these issues on January 6, 1997. But Glossip said that encounter never happened. Instead, Glossip maintained that Van Treese was his normal self on that day.

As police were searching for Van Treese the next day, suspicion quickly fell on Glossip, who provided conflicting statements and sent investigators on false leads. Later, a friend of Glossip's—Justin Sneed—would confess that he (Sneed) had murdered Van Treese and that Glossip had commissioned him to commit the murder. In 1998, a jury convicted Glossip and he was sentenced to death. After reversal of that conviction for ineffective assistance of counsel, in 2004 a jury again found Glossip guilty and he was sentenced to death based on testimony from Sneed and other witnesses. The judge who presided over the trial found Sneed "to be a credible witness on the stand," as quoted at p. 46 of the 2022 State's Submission to Parole Board. At sentencing, another judge echoed this conclusion, saying to Glossip: "I would say that after observing the witnesses and hearing the testimony I have absolute confidence in the decision the jury reached, both to convict you, to find the aggravators and to impose the sentence of death," as quoted at p. 48 of the same 2022 submission.

In 2007, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals ("OCCA") affirmed Glossip's conviction and sentence, rejecting Glossip's claim that the evidence only proved his was an accessory after the fact. In the years since, courts have rejected multiple challenges by Glossip to his conviction and death sentence.

Nearly two decades later, Oklahoma was preparing to execute Glossip when a new Attorney General, Gentner Drummond, was elected. Shortly after assuming office in January 2023, and apparently sensing political opportunity, the new Attorney General hastily commissioned an "independent" review of Glossip's conviction. Conveniently, General Drummond hired Rex Duncan, his lifelong friend and a political supporter who possessed limited experience in capital litigation. Duncan suddenly discovered "new" evidence the prosecution had purportedly concealed from the defense.

As the tale is told in Glossip's and Oklahoma's briefs before the Supreme Court, the trial prosecutors withheld from Glossip's defense team information about Sneed's lithium usage and related psychiatric care. This story rests on an interpretation of notes the prosecutors took during a pretrial interview of Sneed. Specifically, General Drummond asserts that the handwritten notes indicated that Sneed told the prosecutors "that he was 'on lithium' not by mistake, but in connection with a 'Dr. Trumpet.'"

Before the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals (the "OCCA"), Oklahoma's highest court on criminal issues, five judges considered General Drummond's confession of error and were unimpressed. In April 2023, in a detailed opinion, the OCCA unanimously concluded that the Attorney General's concession was "not based in law or fact."

In May 2023, Glossip sought certiorari, supported by Attorney General Drummond. The Court re-listed Glossip's petition twelve times through the end of 2023.

In January 2024, the Supreme Court granted certiorari to review questions relating to the Court's jurisdiction and the implications of "the State's suppression" of Sneed's "admission he was under the care of a psychiatrist …." Because no one was defending the OCCA's judgment below, the Court appointed Chris Michel, a very capable appellate lawyer in Washington, D.C., to defend it as Court-appointed amicus.

The Supreme Court lacks jurisdiction in this case, for the reasons explained in briefs by the Court-appointed amicus, Utah and six other states, and the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation. But more important, Glossip's conviction should be affirmed because the prosecutors never suppressed anything.

Here's what really happened during the prosecutors' interview of Sneed two decades ago: On October 22, 2003, before Glossip's retrial, prosecutors Connie Smothermon and Gary Ackley interviewed Sneed, with Sneed's counsel present. Smothermon and Ackley both took notes. Read in context, the notes show that Sneed told the group that members of Glossip's defense team had previously visited him (Sneed) and questioned him about being "on lithium?" and a "Dr[.] Trumpet?" Smothermon and Ackley simply took notes recording what Sneed recounted about questions from Glossip's own defense team!

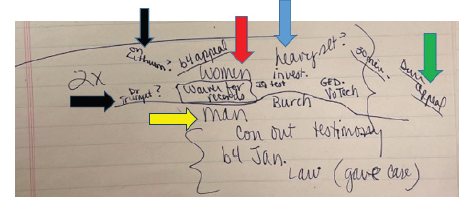

Turning first to Smothermon's notes, General Drummond argues that the prosecutor had "taken handwritten notes confirming her knowledge of Sneed's diagnosis and treatment"—e.g., treatment for a psychiatric condition by lithium by a Dr. Trumpet. But General Drummond fails to quote Smothermon's notes accurately, much less discuss their context or meaning in any detail. Smothermon's note regarding lithium contains a question mark—e.g., her note reads, "on lithium?" And her related note about "Dr[.] Trumpet" likewise contains a question mark. You can see the notes in question in the image below—with "on lithium?" and "Dr[.] Trumpet?" flagged with black arrows:

Stepping back to examine the surrounding context of these two notes reveals that Smothermon was simply recording Sneed recounting what Glossip's defense team was questioning him (Sneed) about—hence, the two question marks reflecting questions being asked. Smothermon's adjoining notes reflect two visits ("2X") by defense representatives—with notes about the two visits separated by a curving line.

Turning to the first visit, as shown by the note flagged with a red arrow above, Sneed's visitors were "women." As shown by the notes flagged with a blue arrow, that visit involved an investigator ("invest.") who may have been heavy set ("heavy set?"). As shown by the notes flagged by the green arrow, the defense representatives may have been involved in Glossip's earlier direct "appeal." And, finally, as shown by the notes flagged by the two black arrows, the women questioned Sneed about (1) whether he was "on lithium?" and (2) a "Dr[.] Trumpet?"—i.e., questioned by the women representing Glossip. Thus, read in context, the key words in Smothermon's notes reveal that Sneed was recounting not what Smothermon had independently learned (much less confirmed) but rather what questions Glossip's defense team was asking Sneed.

While General Drummond fleetingly (and inaccurately) discusses Smothermon's notes, he fails to substantively discuss the notes taken by the prosecutor seated next to Smothermon during the interview, Gary Ackley. Ackley's contemporaneous notes interlock with Smothermon's and confirm that the prosecutors were merely recording Sneed recounting two meetings with the defense team.

At the top part of his notes, Ackley wrote that the witness (i.e., "W" or Sneed) was "visited by 2 women who said they rep Glossip – heavy 1 'Inv' & 1 'Atty' – Appellate?" This important sentence in Ackley's notes is flagged by the red arrow below:

Ackley's notes further indicate, as flagged by the blue arrow above, that the two women who "said they rep[resented] Glossip" were "1 'Inv' & 1 'Atty' – Appellate?"—that is, the women who visited Sneed were an investigator and an (appellate?) attorney representing Glossip. Ackley's notes reflect, as flagged by the black arrow above, that it was these two women who asked Sneed about lithium ("Li"). And, as flagged by the green arrow above, Sneed indicated to Glossip's defense representatives that the lithium was being prescribed in connection with a "tooth pulled." Further, as flagged by the orange arrow, the women asked Sneed about "Nurse's cart record discrepancies v. W's [i.e., Sneed's] jail permanent record"—i.e., issues about Sneed's medical history. And Glossip's defense team also asked Sneed about an "IQ test" and "GED, etc."

That Ackley's notes correspond so closely with Smothermon's notes begs the question why General Drummond fails to discuss what Ackley recorded in his notes—and has even failed to include all of Ackley's notes before the OCCA and the Supreme Court. General Drummond's (and Glossip's) omission of Ackley's notes is deceptive. The text of Ackley's notes leave no doubt that Sneed was being asked about lithium and a possible doctor by women representing Glossip.

Thus, during their October 22, 2003, pretrial interview, Smothermon and Ackley simply recorded Sneed recounting a first interview by two women representing Glossip. Did such an interview by the defense team take place? It clearly did.

In earlier litigation before the OCCA, the Oklahoma Attorney General's Office filed a sixty-two-page opposition to Glossip's Fourth Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Release. That opposition explained that on April 16, 2001, before Sneed's first conviction had been reversed, Glossip's post-conviction attorney, Ms. Wyndi Hobbs, visited Sneed in prison. Hobbs was with an investigator named Ms. Lisa Cooper. During the meeting, attorney Hobbs told Sneed that it looked like Glossip would get a new trial and that there was a good chance that Sneed would be called to testify again. Hobbs indicated that she was going to "set up a second meeting and take [Sneed] an affidavit to review and sign." Apparently, Sneed "signed releases for juvenile, jail, prison and criminal records."

These references in the record establish that Glossip's defense team met with Sneed—i.e., a meeting with two women (attorney Wyndi Hobbs and investigator Lisa Cooper). That such a meeting occurred reinforces the conclusion that Smothermon's and Ackley's notes simply reflect Sneed recounting defense team questions.

Of course, if the prosecutor's notes merely record Sneed recounting questioning from the defense team, the notes could not reflect information withheld from the defense. The notes would reflect information about the defense. No Brady violation could even possibly exist. Glossip and the Oklahoma A.G. have simply concocted a phantom constitutional claim lacking any basis. And they have subjected the victim's family to additional, frivolous litigation on top of two decades of earlier litigation.

So do Glossip and Oklahoma have any response to these damning arguments? Their (non)response is the subject of tomorrow's post.

The post Glossip v. Oklahoma: The Story Behind How a Death Row Inmate and the Oklahoma A.G. Concocted a Phantom "Brady Violation" and Got Supreme Court Review (Part I) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] MSNBC Pundit's Tweet Accusing Lawyer of "Coach[ing a Witness] to Lie" Is a Potentially Defamatory Factual Assertion, Not an Opinion

From Judge Loren L. AliKhan's decision yesterday in Passantino v. Weissmann (D.D.C.):

The following factual allegations drawn from Mr. Passantino's complaint, are accepted as true for the purpose of evaluating the motion before the court. Mr. Passantino has been a lawyer for more than thirty years. In 2017 and 2018, he served as a senior lawyer in the Trump administration. Since then, he has been in private practice.

Following the attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, the House of Representatives established a Select Committee to investigate what had happened. As part of its investigation, the Select Committee interviewed numerous witnesses, including Cassidy Hutchinson, a former special assistant to President Trump who had been serving under the direction of White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows on January 6, 2021.

Mr. Passantino represented Ms. Hutchinson at her first three closed-door Select Committee depositions on February 23, March 7, and May 17, 2022. While the complaint does not specify exactly when this occurred, Ms. Hutchinson sent text messages to a friend expressing that she "d[idn]'t want to comply" with the Committee's requests. In the same conversation, however, she noted that "Stefan [Passantino] want[ed] [her] to comply."

Following the second deposition, Ms. Hutchinson felt that she had "withheld things" from the Select Committee and wanted to "go in and … elaborate … and kind of expand" on some topics. Unbeknownst to Mr. Passantino, Ms. Hutchinson asked a friend to "back channel to the committee and say that there [were] a few things that [she] want[ed] to talk about." While Ms. Hutchinson deliberately kept this from Mr. Passantino, she explained at a future deposition that, at that time, she "wasn't at a place where [she] wanted to terminate [her] attorney-client relationship with [Mr. Passantino]."

In early June 2022, after the third deposition, Ms. Hutchinson fired Mr. Passantino and retained Bill Jordan and Jody Hunt as her new counsel. She subsequently gave a fourth, televised deposition on June 28, which received substantial media coverage.

After her fourth deposition, Ms. Hutchinson sent a letter to the Select Committee stating that she intended to "waive [her] attorney-client privilege [with Mr. Passantino] in order to share information with the Committee that [was] relevant to [her] prior testimony." The Select Committee accordingly scheduled her for a fifth deposition for September 14, 2022.

At her fifth deposition, Ms. Hutchinson revealed additional details about the preparation she and Mr. Passantino had done ahead of her first Select Committee deposition. Specifically, the two had met "for a couple hours" on February 16, 2022 to discuss her upcoming testimony. When Ms. Hutchinson suggested printing out a calendar so that she could "get[] the dates right" with respect to timelines of events, Mr. Passantino said "No, no, no." He told her that the plan was "to downplay [her] role" and that "the less [she] remember[ed], the better." Id. 30:19-31:2. When Ms. Hutchinson brought up an incident that occurred inside the Presidential limousine on January 6 (which she had been told about by a colleague), Mr. Passantino said "No, no, no, no, no. We don't want to go there. We don't want to talk about that."

Mr. Passantino then told Ms. Hutchinson: "If you don't 100 percent recall something, even if you don't recall a date or somebody who may or may not have been in the room, ['I don't recall' is] an entirely fine answer, and we want you to use that response as much as you deem necessary." Id. 36:7-10. Ms. Hutchinson then asked, "if I do recall something but not every little detail, … can I still say I don't recall?" to which Mr. Passantino replied, "Yes." The morning of the first deposition, Mr. Passantino reminded Ms. Hutchinson to "[j]ust downplay [her] position," telling her that her "go-to [response was] 'I don't recall.'"

At her fifth deposition, Ms. Hutchinson discussed a line of questioning from her first deposition about the January 6 incident in the Presidential limousine. She explained that, during a break after facing repeated questions on the topic, she had told Mr. Passantino in private, "I'm f*****. I just lied." Mr. Passantino responded, "You didn't lie…. They don't know what you know, Cassidy. They don't know that you can recall some of these things. So you [sic] saying 'I don't recall' is an entirely acceptable response to this." He concluded, "You're doing exactly what you should be doing." Ms. Hutchinson explained that, in the moment, she "[felt] like [she] couldn't be forthcoming when [she] wanted to be."

Ms. Hutchinson did, however, state at her fifth deposition: "I want to make this clear to [the Select Committee]: Stefan [Passantino] never told me to lie." She recalled him saying to her: "I don't want you to perjure yourself, but 'I don't recall' isn't perjury. They don't know what you can and can't recall." She then reiterated to the Select Committee, "[H]e didn't tell me to lie. He told me not to lie."

At the Committee's final public session on December 19, 2022, a Congressmember announced that they had "obtained evidence" that "one lawyer told a witness the witness could in certain circumstances tell the Committee that she didn't recall facts when she actually did recall them."

After the Committee released the transcripts from the Ms. Hutchinson's closed-door depositions, multiple news outlets claimed that the "lawyer" referred to by the Select Committee member was Mr. Passantino. On September 15, 2023, Mr. Weissmann—a former prosecutor who now serves as a "political pundit" for MSNBC—posted the following on X (formerly known as Twitter):

Mr. Weissmann made the post in response to an alert that Mr. Hunt had been subpoenaed in an unrelated case. Mr. Weissmann had approximately 320,000 followers on X at the time.

Passantino sued for defamation (and a related tort), and the court allowed the defamation claim to go forward:

Mr. Passantino alleges that Mr. Weissmann's post "deeply damaged [his] 30-year reputation and caused him to lose significant business and income." Prior to the allegations surrounding his representation of Ms. Hutchinson, Mr. Passantino had "never been accused by a client, or anyone else, of unethical or illegal behavior." …

The parties agree that this motion boils down to a core question: was Mr. Weissmann's social media post that "[Mr. Passantino] coached [a witness] to lie" a verifiably false fact, or a subjective opinion? This is not an easy inquiry, and the answer in such cases is rarely clear cut.

{For the purposes of this motion, the parties do not dispute other possible defenses to a claim for defamation, such as whether the content of Mr. Weissmann's post was substantially true. After this court's resolution of the motion to dismiss, Mr. Weissmann is free to raise any such defenses not barred by the Federal Rules. See Long v. Howard Univ.\ (D.C. Cir. 2008) ("[A] defense can be raised [as late as] at trial so long as it was properly asserted in the answer and not thereafter affirmatively waived."). The court is thus only deciding whether Mr. Weissmann's statement is nonactionable as a subjective opinion.}

The first Ollman v. Evans (D.C. Cir. 1984) (en banc) factor requires the court to determine whether the challenged statement "has a precise meaning and thus is likely to give rise to clear factual implications." The touchstone of this inquiry is whether "the average reader [could] fairly infer any specific factual content from [the statement]." As the Ollman court noted, "[a] classic example of a statement with a well-defined meaning is an accusation of a crime." The allegedly defamatory portion of the post can be distilled into: "[Mr. Passantino] coached [Ms. Hutchinson] to lie." …The definition of the verb "coach" is "to instruct, direct, or prompt." While Mr. Weissmann argues that "coached" is "indefinite," "ambiguous," and "can 'mean different things to different people at different times and in different situations,'" the court concludes that the word conveys a sufficiently precise meaning in the challenged social media post.

Readers of a statement do not isolate and parse individual words into all of their possible connotations. Mr. Weissmann wrote that Mr. Passantino "coached [a witness] to lie." In that string of text, read as a whole, the clear factual implication is that Mr. Passantino "instruct[ed], direct[ed], or prompt[ed]" Ms. Hutchinson "to lie" to the Select Committee. While it is true that general statements that someone is "spreading lies" or "is a liar" are not categorically actionable in defamation, Mr. Weissmann's post very directly claimed that Mr. Passantino had committed a specific act—encouraging or preparing a specific witness to make false statements. A reasonable reader is likely to take away a precise message from that representation.

[The second factor is the d]egree to which the statements are verifiable ….. Verifiability hinges on a deceptively difficult question: "is the statement objectively capable of proof or disproof?" In some ways, this second factor overlaps with the first because the common usage of the statement's words will determine whether the statement—as a whole—can be proven true or false.

Mr. Weissmann advances two arguments for why the statement is not verifiable. First, he reasserts his claim that "coached" is too ambiguous of a term, and that "a statement with a number of possible meanings is by its nature unverifiable." However, as discussed above, the phrase "coached her to lie" is sufficiently precise to "give rise to clear factual implications." Mr. Weissmann's ambiguity argument is therefore not persuasive.

Second, Mr. Weissmann asserts that there is no objective standard for assessing when someone has coached another to lie—at least in the absence of an explicit instruction to do so. For support, he cites various cases for the proposition that evaluating a lawyer's performance is "not susceptible of being proved true or false." Those cases are not particularly useful, however, because they primarily discuss the quality of an attorney's representation, not whether the attorney committed or engaged in a particular act. There is a difference between calling an attorney's representation "good" or "bad," on one hand, and saying that an attorney "lied" or "told the truth," on the other. The former is a subjective spectrum indicative of an opinion; the latter is a yes-or-no binary indicative of a fact….

As for the cases that do concern the act of witness preparation (rather than the quality of an attorney's representation generally), an "objective standard" is only lacking if the court assumes that the term "coach" is ambiguous. If one reasonably reads "coach" to mean "instruct, direct, or prompt" in the context of Mr. Weissmann's full social media post, then the statement is verifiable. Mr. Passantino either "coached"—that is, he "instruct[ed], direct[ed], or prompt[ed]"—Ms. Hutchinson to lie, or he didn't. The second Ollman factor thus favors Mr. Passantino.

[The third factor is the c]ontext in which the statement occurs…. This inquiry focuses on the immediate context surrounding the challenged statement. For example, a sentence asserting a seemingly factual claim takes on an entirely different meaning if situated in a satirical newspaper column….

Here, Mr. Weissmann's post contained only three sentences. It began by stating that "[Mr.] Hunt is Cassidy Hutchinson's good lawyer." Both parties agree that this is "obviously" an opinion. Then, in a parenthetical, it reads: "(Not the one who coached her to lie)." Finally, it concludes, "And [Mr. Hunt] is the guy who took notes of Trump saying, when Mueller was appointed, quoting him as saying 'I'm f….d.'" Mr. Passantino argues that the final sentence is clearly a factual assertion, and Mr. Weissmann does not contest that characterization.

Nothing about the surrounding context suggests that the reference to Mr. Passantino's "coach[ing]" Ms. Hutchinson "to lie" is facetious or sarcastic. It presents neutrally, nestled between a statement of opinion and a statement of fact. Mr. Weissmann contends that because the challenged statement follows a statement of opinion, it must also be an opinion, especially because it comes in the form of a parenthetical. Mr. Passantino takes the opposite view, arguing that the challenged statement must be a statement of fact because it is followed by a statement of fact. Given how short the full statement is, the court cannot divine much from the contested language's location to determine whether it is presented as a subjective thought or a verifiable fact….

The fourth and final Ollman factor evaluates the broader social context beyond the statement and its immediate surroundings…. Starting with X, the statement's backdrop, Mr. Weissmann asserts that it is generally considered an "informal" and "freewheeling" internet forum. [S]ome courts have held that "the fact that Defendant's allegedly defamatory statement … appeared on Twitter conveys a strong signal to a reasonable reader that [it] was Defendant's opinion."

While Mr. Weissmann is correct that X is seen by many as a free market for the exchange of subjective ideas, its use is not always one-sided. Journalists and reporters use X to post news alerts and factual content…. [I]nferring that Mr. Weissmann's statement was an opinion based solely on his use of the X platform risks overlooking "society's expectations of journalistic conduct on [X]." That is especially so when Mr. Weismann is a public figure connected to a news organization and not a private user.

This leads to Mr. Weissmann's status as a "political pundit." … Mr. Passantino asserts that Mr. Weissmann's career as a former prosecutor, his twenty-plus years of experience in the Department of Justice, and his record as an accomplished author of a book about federal prosecutions make his audience more likely to view his statements as facts. And while Mr. Weissmann currently serves as a political commentator on MSNBC, Mr. Passantino argues that that should not shield his comments from liability.

Mr. Passantino is correct that "there is no blanket immunity for statements that are 'political' in nature … [because] the fact that statements were made in a political context does not indiscriminately immunize every statement contained therein." Individuals who immerse themselves in political commentary are still capable of defaming others with verifiably false assertions. And, presumably, Mr. Weissmann does not limit his social media activity strictly to offering opinions. After all, at least one-third of the social media post in question was an expression of objective fact. Clearly, then, Mr. Weissmann's audience of followers can expect him to present some statements of fact.

At the same time, Mr. Weissmann is correct that reasonable readers know to expect subjective analysis from commentators. As a political pundit (rather than, say, a news anchor), his statements possess a general air of opinion rather than fact. "Reasonable consumers of political news and commentary understand that spokespeople are frequently (and often accurately) accused of putting a spin or gloss on the facts or taking an unnecessarily hostile stance toward the media or others." And numerous courts have held that the average reader, viewer, or listener tempers his or her expectations of hearing factual reporting in the world of punditry….

On balance, the fourth factor weighs in Mr. Weissmann's favor. But even so, the court concludes that the overall analysis of the Ollman factors suggests that his statement was not a subjective opinion.

Again, keep in mind that this merely resolves that the statement is a factual assertion; to prevail, plaintiff must still show that it's false and that defendant said it with the requisite mental state.

The post MSNBC Pundit's Tweet Accusing Lawyer of "Coach[ing a Witness] to Lie" Is a Potentially Defamatory Factual Assertion, Not an Opinion appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 1, 1924

10/1/1924: Chief Justice Rehnquist's birthday.

Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist

Chief Justice William H. RehnquistThe post Today in Supreme Court History: October 1, 1924 appeared first on Reason.com.

September 30, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Monday Open Thread

The post Monday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

[Stephen Halbrook] Second Amendment Roundup: Textualism and ATF's Redefinition of "Firearm"

This is my second installment preceding the upcoming October 8 argument in Garland v. VanDerStok, a challenge to the regulatory redefinition of the term "firearm" in the Gun Control Act. By expanding the statutory definition, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms & Explosives (ATF) in its 2022 Final Rule purports to criminalize numerous innocent acts that Congress never made illegal.

Until the new rule, a kit with partially-machined raw material that can be fabricated into a firearm was not considered to have reached a stage that it is a "firearm." To prevent Americans from making their own firearms from such material, which has always been and remains lawful, the bugbear term "ghost guns" was recently coined. In its VanDerStok brief, the government argues that "anyone with basic tools and rudimentary skills" can "assemble a fully functional firearm" from such kits "in as little as twenty minutes."

As explained in my last post, that is refuted by none other than the former Acting Chief of ATF's Firearm Technology Branch, Rick Vasquez, who reviewed and approved hundreds of classifications about whether certain items are "firearms." As he explained in his amicus brief, fabrication of a firearm from these kits is a complex process requiring skill and special tools beyond the capacity of the average person.

In this post I'll trace the statutory history of the term "firearm" to gain insight into its meaning. The Gun Control Act defines "firearm" as "(A) any weapon (including a starter gun) which will or is designed to or may readily be converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive; (B) the frame or receiver of any such weapon…." 18 U.S.C. § 921(a)(3). An ATF regulation on the books from 1968 to 2022 defined a "frame or receiver" as "that part of a firearm which provides housing for the hammer, bolt or breechblock and firing mechanism," i.e., the main part of a firearm to which the barrel and stock attach.

ATF's Final Rule stretches these terms to mean parts, material, jigs, tools, and instructions that constitute neither an actual "firearm" nor a "frame or receiver," but may be used by a skilled person with proper tools to fabricate these items.

This new regulatory definition of "firearm" obviously conflicts with the definition enacted by Congress. Two cases decided by the Supreme Court this year directly apply. Per Dep't. of Agriculture Rural Dev. Rural Housing Service v. Kirtz: "When Congress takes the trouble to define the terms it uses, a court must respect its definitions as virtually conclusive." Congress defined "firearm." And while Congress did not explicitly define "frame or receiver," Snyder v. United States teaches that, after analyzing the statutory text, a court may look at "the statutory history, which reinforces that textual analysis."

Statutory history is a prime focus of the Amicus Curiae Brief of the National Shooting Sports Foundation, which I coauthored with Schaerr Jaffe LLP and NSSF counsel. As the brief details, the statutory history reinforces the textual analysis. I have covered the subject further in "Textualism, the Gun Control Act, and ATF's Redefinition of 'Firearm,'" Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy: Per Curiam, Aug. 27, 2024.

We begin with the Federal Firearms Act of 1938 ("FFA"), 52 Stat. 1250, which defined a firearm as "any weapon, by whatever name known, which is designed to expel a projectile or projectiles by the action of an explosive … or any part or parts of such weapon." It provided that any person who violated "any of the provisions of this Act or any rules and regulations promulgated hereunder" was subject to fines and imprisonment. It empowered the Secretary of the Treasury to "prescribe such rules and regulations as he deems necessary to carry out the provisions of this Act."

FFA regulations required licensed manufacturers to record firearms disposed of, including "the serial numbers if such weapons are numbered." Dealers were required to record acquisitions and dispositions. Required records included "firearms in an unassembled condition, but not including parts of firearms." That an "unassembled" firearm constituted a firearm in no way implied that raw material and unfinished parts were considered a firearm.

Revenue Ruling 55-175 (1955) held that "a barrel[ed] action comprised of the barrel …; front and rear stock bands; receiver with complete bolt, trigger action, magazine, etc., is a weapon, complete except for the stock, which is capable of expelling a projectile or projectiles by the action of an explosive." One can see here the understanding of a "receiver" as the housing that holds the internal parts that would be reflected in the 1968 regulatory definition of "frame or receiver."

Apparently, the only judicial decision on the meaning of "part or parts" in the FFA was United States v. Lauchli (7th Cir. 1966), which mostly concerned dealing in unregistered machine guns.

The court held that "Browning automatic rifle magazines" were "parts" under the FFA because "such weapons could not be fired automatically without the magazines." These finished parts contained in the machine guns were "serviceable parts, thus bringing them within the scope of the [FFA]." This statement confirmed that items that were not "serviceable parts" were not considered "parts."

In sum, under the FFA, a "firearm" was a "weapon" designed to expel a projectile, whether assembled or unassembled. To be a "part or parts," the items had to be serviceable. A "receiver" housed the bolt, trigger action, and magazine. This background demonstrates that partially completed material that had not become an actual weapon or useable parts was not considered a "firearm."

Despite recent political jargon about so-called "ghost guns," from the ratification of the Second Amendment in 1791 until 1958, no federal legislation required that anyone—even a firearm manufacturer—mark a firearm with a serial number. Then in 1958, a regulation required manufacturers and importers to identify each firearm "by stamping … the name of the manufacturer or importer, and the serial number, caliber, and model of the firearm…. However, individual serial numbers and model designation shall not be required on any shotgun or .22 caliber rifle…."

Beginning in 1963, bills were introduced to revise the FFA that would eventually find their way into the Gun Control Act ("GCA") of 1968, the major federal law regulating firearms today. As reflected in Senate Report No. 90-1097 (1968): "It has been found that it is impractical to have controls over each small part of a firearm. Thus, the revised definition substitutes only the major parts of the firearm; that is, frame or receiver for the words 'any part or parts.'"

Initially, the GCA bills continued the FFA provision making violation not just of the Act, but also of any rule or regulation, a criminal offense. In floor debate, Senator Robert Griffin objected that lawmakers "should not delegate our legislative power … in the area of criminal law," and that due process required that "we should spell out in the law what is a crime." Likewise, Senator Howard Baker rejected "plac[ing] in the hands of an executive branch administrative official the authority to fashion and shape a criminal offense to his own personal liking." 114 Cong. Rec. 14,792 (May 23, 1968). Making it a crime to violate a regulation was then removed from the bill.

As enacted, the GCA defined "firearm" exactly as it is defined by that statute now. It required licensed manufacturers and importers to engrave a serial number on each frame or receiver.

Also in 1968, the Treasury Department adopted the same regulatory definition of "frame or receiver" that was retained until 2022: "That part of a firearm which provides housing for the hammer, bolt or breechblock and firing mechanism, and which is usually threaded at its forward portion to receive the barrel." That reflected the common understanding of the meaning of those terms. In fact, each of the terms in the definition was defined that same year in Chester Mueller & John Olson, Small Arms Lexicon and Concise Encyclopedia (1968).

Just before adopting its proposed GCA regulations in 1968, Treasury held a public hearing, the only one ever held before or since. Not a single witness objected to the definition of a frame or receiver. To the contrary, an industry witness praised the "very clear definition of a … receiver, something we didn't have before[.]"

If the 1968 regulation could talk, it would say: "read my lips – the frame or receiver is the 'part' that 'provides housing' for the internal parts in the present tense, not partially-machined raw material that 'could provide housing' in the future should one perform the required fabrication operations."

In deep-sixing the Chevron deference doctrine in Loper Bright Enters. v. Raimondo, the Supreme Court said that historically "respect was thought especially warranted when an Executive Branch interpretation was issued roughly contemporaneously with enactment of the statute and remained consistent over time." That applies perfectly to the 1968 regulation, which expressed the common understanding of "frame or receiver" when Congress enacted the GCA, and remained in force for the next fifty-four years until ATF abruptly scrapped it.

In enacting the Firearm Owners' Protection Act ("FOPA") of 1986, Congress found "additional legislation" necessary "to correct existing firearm statutes and enforcement policies." But it left intact the GCA's definition of "firearm" and expressed no dissatisfaction with ATF's definition of "frame or receiver." It was the same result in the three subsequent times in which Congress defined certain types of firearms – the Crime Control Act of 1990, defining "semiautomatic rifle"; the Brady Act of 1993, defining "handgun"; and the Public Safety & Recreational Firearms Use Protection Act of 1994, defining "semiautomatic assault weapon" (repealed in 2004).

As the Supreme Court opined in U.S. v. Rutherford (1979), "once an agency's statutory construction has been 'fully brought to the attention of the public and the Congress,' and the latter has not sought to alter that interpretation although it has amended the statute in other respects, then presumably the legislative intent has been correctly discerned."

However, FOPA mandated that the Secretary (now the Attorney General) may prescribe "only such rules and regulations as are necessary to carry out the provisions of this chapter," deleting the prior language that "the Secretary may prescribe such rules and regulations as he deems reasonably necessary." And yet today, ATF's Final Rule purports to expand the meaning of terms in conflict with the GCA's plain text and thereby to criminalize previously legal conduct through regulations.

In sum, the statutory history reinforces the textual analysis that the term "firearm" is limited to the exact definition that Congress enacted, and does not extend to an open-ended, undefined "parts kit" that flunks that definition. Further, a "frame or receiver" is the main part of a firearm that provides housing for the internal parts, an understanding that has persisted over a half century. It does not include partially-machined raw material that has not been fabricated into a functional housing.

For much more on the statutory history beginning with the Federal Firearms Act of 1938 and going forward, please see my article "The Meaning of 'Firearm' and 'Frame or Receiver' in the Federal Gun Control Act: ATF's 2022 Final Rule in Light of Text, Precedent, and History."

The post Second Amendment Roundup: Textualism and ATF's Redefinition of "Firearm" appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers