Alexander Billet's Blog, page 7

January 12, 2024

Fatal Holes

Standing outside the theatre in Leicester Square, considering the various combinations of nondescript suitcoats and evening dresses waiting to be let in, I had a thought I’ve been having a lot lately. Had it not been for the events of recent years, this line may be a bit denser. A great many here had lost someone close to them at the height of the pandemic, a friend or loved one, someone who they might have otherwise invited to accompany them to that evening’s performance of Hamnet.

Granted, the average demographic represented in that line — more on that later — would have access to care and resources many other parts of the world, even other parts of the UK, would not. Still, the numbers being what they are, odds are that there were a fair number of ghosts waiting with us.

They say that the vitality of live theatre is gone, that the stage is a dead medium. That its relationship to the most visceral and extraordinary experiences in daily life has been loosened to such a degree that, ultimately, most people can’t be fucked to care what the artform has to say.

They’ve been saying this for a long time. Nobody seems to fear it more than theatre’s most dedicated practitioners. In the introduction to his and Nicholas Wright’s 2000 book Changing Stages, former National Theatre artistic director Richard Eyre admitted that to stake a claim of his artform’s continuing relevancy was to take a position of almost unrealistic optimism. The necessity of this optimism is reflected in his observation that the opinions of newspapers’ theatre critics — once widely respected and listened to by all who wanted to keep up on what was happening culturally — no longer carried much weight. Eyre quoted former Sunday Times theatre critic Harold Hobson: “The trouble with our successors is that nothing seems at stake for them.”

Nearly 25 years later, this hasn’t changed. But then, for theatre critics to have anything at stake, so too must the theatre itself. Theatre critics have been glowing their praise of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Hamnet. The blurbs on the promotional posters in the London Underground call it “pure theatre gold.” And frankly, this kind of description of this particular play could only cut ice in a world where plays don’t matter anymore. At least not to the degree they once did.

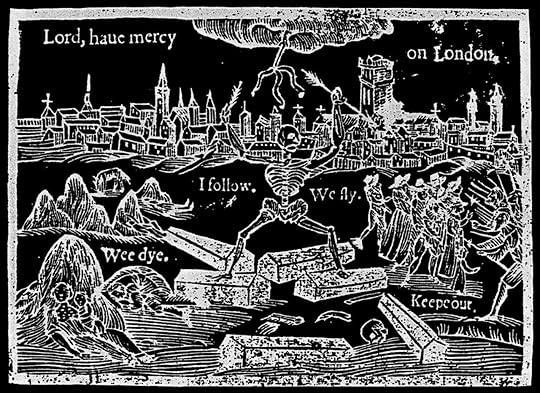

Hamnet, as a play, should matter. The novel it’s based on — of the same name, written by Maggie O’Farrell — was one of the bestsellers of 2020, appropriately enough for “a novel of the plague.” O’Farrell’s book is just that. It tells a version of the story of the death of William Shakespeare’s only son, which some speculate came from bubonic plague.

Why this story should be relevant, given the events of the past few years, is self-evident. O’Farrell’s novel admirably captures all the sadness and confusion of loss in the midst of spreading disease, which no doubt struck readers in the gut during a harrowing time. But reading can only ever be a solitary act, leaving us to walk into the world with a hole in our chests we still, inexplicably, don’t acknowledge to each other.

Hamnet the play should be an opportunity to collectivize the grief and trauma. Seeing this story — the tragedy of losing a child, the wedge it drives into families, the thorny but inexorable pull for the artist to process their grief through their work — acted out before an audience might be cathartic in this context. It should be, but it isn’t. Not in the RSC’s version.

Like most other things related to the lived life of William Shakespeare, the historical record of his son’s death is scant. It is accepted that William married Anne Hathaway in November of 1582 somewhere in or around Stratford-upon-Avon. He was 18, she was 26. Their first child, Susanna, was born six months later in 1583. In 1585, Anne gave birth to twins, Hamnet and Judith. Hamnet died in 1596, with the cause of death unrecorded. Records tell that this was several years into William’s increasingly lucrative playwriting career, when he was splitting his time between London and Stratford.

These are the parameters that O’Farrell used to spin the story of her book, from established fact to theories and arguments among scholars, to hypotheses and educated guesses, then finally to simply inventing the conversations and interactions that make up the meat of her novel. Though Hathaway’s accepted first name is Anne, her father’s will refers to her as Anges, and O’Farrell does the same. Given the frequent outbreaks of bubonic plague that would periodically crop up across Europe, it isn’t unreasonable to think that Hamnet died after contracting the disease, and this is how his death is recounted in the book.

Then there’s the matter of the name. Nobody can miss the similarity between that of Shakespeare’s son and that of his famous play, perhaps the most influential in the English language, written just a few years after Hamnet’s death. Scholars have bickered for centuries over whether Shakespeare deliberately chose a name so similar to Hamnet’s when he wrote Hamlet. If baptismal records are to be believed, and the name given to Hamnet during his christening was “Hamlette Sadler Shakespeare,” then it seems more than a bit likely.

O’Farrell’s Hamnet is, therefore, less historical novel than occult history, and in more than one sense. You see, the book suggests that Agnes was learned in the ways of herbs, that she was given to visions, could commune with animals, and would go to the woods to give birth. In other words, Agnes was at best thought a bit strange, and at worst was holding at bay whispers that she was a witch.

That isn’t all she is, though. She is devoted and strong-willed. Despite her illiteracy, she is easily the smartest person in the room, and manages to stay that way with everyone else thinking they know best. She is also particularly protective of her twins. When Judith falls ill with the plague, she plies every remedy she’s been taught to save her daughter. When Judith miraculously recovers, only then for her brother to get sick and die, Agnes’ grief engulfs both her and everyone around her.

All except Will. After Hamnet’s funeral, he quickly retreats back to London. The Will of Hamnet is quite different from the William Shakespeare we have drilled into us. He is intelligent but naïve, and nowhere near as strong-willed as Agnes. He isn’t just in love with her, but in awe of her, at her ability to understand what he cannot. Learned and literate though he is, he can’t find the vocabulary for some of the most harrowing experiences.

Naturally, her husband’s constant aloofness embitters Agnes. When she hears of the production of Hamlet, she ventures into London herself to admonish him for being such a coward, such an opportunist. Only after seeing that Prince Hamlet is a subtle, complicated, flawed-but-admirable, fully fleshed human does she understand. Hamlet was the only thing Will could think of doing to make sense out of a senseless unknown, his version of Agnes’ uncanny sight.

O’Farrell’s book is prescient because it interrogates what we do with the painful reality of cosmic indifference. It is an investigation into the unpredictable interactions between love, grief, and intellect, the alchemical overlaps between the act of creation and the inevitability of loss. And it manages to do so with minimal sentimentality, despite how easy it is to fall into the traps of the overwrought with a story like this.

It’s the kind of sweeping story — epic but intimate — that people once flocked to the theatre to see. Indeed, in Shakespeare’s own time, it was the kind of story that could only be told on the stage. People would crowd by the hundreds into sweaty wooden O’s, literally standing in shit, to witness and be moved by a tale like Hamnet.

I, unfortunately, was not standing in shit. I had paid £55 for nosebleed seats at the Garrick Theatre. I was sat next to two women with Sloane Ranger accents discussing matter-of-factly that mummy and daddy were paying the mortgage for them. In all likelihood, they too had lost someone dear to them in recent years. But such topics aren’t the stuff of polite conversation during a genteel night at the theatre.

As for the play itself, it underwhelmed from its first moments. Some of that was down to Lolita Chakrabarti’s adaptation. While much of the dialog is taken directly from O’Farrell’s book, its structure, its non-linear moves between the events of Will and Agnes’ marriage, the birth of their children, and Hamnet’s death, are flattened into a linear chain of events. This is an unambitious, paint-by-numbers adaptation, barely attempting to reach in the direction it needs to.

The cast seems to do as well as they can with this uninspired material, but they are further hobbled by Erica Whyman’s uninspired direction. It makes for sloppy performances, none so noticeable as that of Madeline Mantock’s Agnes. This is a character that must fill the stage with herself and her aura. When she stands tall it needs to be with all the sturdiness of an oak, when she mourns it must be the kind of mourning that catches the breath of everyone around her. Her grief needs to be on the level of Medea or Hecuba. As it is, even when Agnes stands alone on an empty stage weeping for her dead son, it carries more novelty than power.

This isn’t even a problem of the sentimental, which might be understood if not forgiven. No, Hamnet is a play that is attempting to give us a carbon copy of sentimentality, and can’t even manage to do that successfully.

During intermission, I looked around and saw how delighted the audience was, how pleased they were for such a perfectly aesthetic night at the theatre. How utterly unmoved they were by this story of what is supposed to be the most devastating loss you can fathom.

I wanted to rage at them. Every single one of them. Partly because far too many of them have been far too protected from other people’s rage for far too long. And partly because this story — all of our stories — merit more than polite laughter between sips of overpriced chardonnay. I pictured myself storming down the bar, grabbing everyone by the collar, shaking them by their shoulders, screaming in their faces. Why are you so calm? So contented? You know the devastation that comes! You’ve felt it yourself! The way you wanted to rend your clothes and howl at the unfairness of it all? The hole it left inside you? How can you ignore it when this play is set to tearing away at it?

I wanted to, but I didn’t. Mostly because the play, despite its subject matter and source material, didn’t tear away at the empty spaces left by our dead friends and family. It simulated the act, provided enough so those in attendance could talk about what a lovely night at the theatre they had. It did not, however, create much of anything in the way of emotional resonance. The raw edges of absence and loss were left more or less untouched. The casual frivolity, the idle chit-chat in a theatre lobby; these were, ultimately, warranted by what this audience was watching.

What is the point of a play like this? What is its intent? Is it to change something, even if only the air around it? Does anyone involved with it understand that this means making the audience feel something they’ve never felt, see something they’ve never seen? Does this play set out to do that and merely fail? Or is it simply recapitulating something that already exists, but with just enough variation to hold the attention of people who aren’t used to being challenged? As a theatrical experience, Hamnet fails to satisfactorily answer any of these questions.

Few plays are a full and totalizing encapsulation of a given moment’s class politics and withering culture, but we can say that each one reflects something of these back to us in a fractured, incomplete manner. Two things are true here. The first is that the Royal Shakespeare Company is one of the more flagrant examples of how mainstream Britain is continually finding ways to maintain its weird, neo-Victorian cultural superiority complex. It is also true that the RSC has managed to shape some of the sharpest talents in contemporary theater. It has cast some of the most creative actors. It has employed some of the most daring dramaturgs. And it has provided training from some of the most skilled practitioners and teachers, well-educated themselves on such varied topics as the intricacies of Elizabethan history and the biomechanics of the human voice and body.

The RSC’s primary flaw, though, is the primary flaw of most theatrical institutions in England. That is, it is less and less viewed as an essential part of a healthy demos and more as a business, with its own subtle ways of making itself responsive and pliable to the market. As public funding for the arts continues to twist on the vine, the access that working-class would-be actors might have had to reach the peak of their craft — think of the grants that allowed, say, Patrick Stewart and Brian Blessed to train at Bristol Old Vic Theatre School — also narrows. So too does the the space to take risks, the time to dive deep into a story and explore is contours. It is just as true at the Royal Shakespeare Company as it is at the Globe, the Old Vic, the National Theatre, and other similar institutions.

Still, even after years of this increasing inertia, there has been evidence of brilliance. In 2001 I saw a full four-hour version of Hamlet at the RSC’s home theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon, starring the tragically underrated Sam West. It was stunning: not just stylishly produced but grounded, rendered in such a way that the style served a purpose. The acting and direction were impeccable too, a reminder that all one needs to make Shakespeare great is to master the language (a task graceful in its simplicity, though no easy feat).

We also can’t blame the flabbiness of the RSC’s Hamnet on the fact that it wasn’t a Shakespeare play. This RSC’s vast resources and capabilities have been well-applied to countless more modern works. Another personal experience: seeing the company’s version of The Lieutenant of Inishmore, well before author Martin McDonagh had become the praised writer-director of films like In Bruges and The Banshees of Inisherin. Again, it was a near-flawless production: absurd, demented, hilarious, and a bit haunting.

What seems to have happened with Hamnet is that its story — particularly the book on which it was based — had become enough of a mass phenomenon that its watering down became inevitable. The eerie timing of the book’s release, the resonance its story fomented between past and present events; these made any possible stage adaptation of Hamnet timely and urgent. It also, for that same reason, made it very lucrative. And when something might make a lot of money, every corner must be cut to ensure it does. A story that might be too taxing or controversial to an imaginary target demographic must have its rough edges smoothed over.

It’s a perverse irony, that a story’s relevance might create pressure to turn it into its shallowest shadow, but that’s the logic that the culture industry. The end result recreates Hamnet’s aching losses while keeping their truth at a safe distance. The well-heeled audience might say they’ve “gone through” catharsis without having done so. They applaud, and the best-paid critics swoon. Sure, a few true believers dissent in their little corners of the internet (like this one), but the machine of theatre-as-spectacle continues to chug along more or less unperturbed.

Understand, when I use the term “theatre-as-spectacle,” I mean it as a bad thing, but I don’t simply mean theatre that is “spectacular,” overblown with expensive sets, grandiose choreography or other such sugar-shiny trinkets. Those can be part of theatre-as-spectacle, but by that same token, a well-crafted and produced play can also make use of these devices and mostly avoid being sucked into the spectacle of it all. Yes, the spectacle I’m talking about here when I describe Hamnet as an example of theatre-as-spectacle is the spectacle of Debord in his best-known work: the manufactured appearance of life filling in for life lived in truth.

In contrast, meaningful art imparts meaning into life, allowing us to tarry with its details and ambiguities, to critically reflect on the forces that might shape it. This is something that — for as much as Debord might object — Hamnet the book does quite well. Several sequences vividly illustrate the quotidian, almost mundane happenstances that allow the story to unfold how it does. The serendipities and coincidences, the examples of uncanny timing, the random cosmic threads that weave the fabric of tragedy, comedy, epic history. Studies in Shakespeare’s own time would couch these events in alchemy or some other numinous universal principle. Bollocks of course, though one must respect that they thought something might explain the randomness of life and death, love and calamity, that these could be, with the right tools, eminently knowable.

Until such time though, only the imagination can provide some logic to this ineffable randomness. Whether it is in the form of oil painting, game theory, or Elizabethan playwriting, it is the imagination that puts substance to the most baffling strands of human existence. It is, we might say, the crucial element of “anti-spectacle,” that which will enlarge rather than diminish the reach of collective human subjectivity. And it should — again, should — be the primary animating force behind any worthy work of art. It may proceed from what we know, what we can grasp, but dares to leap into what we, at this time, cannot.

No passage illustrates this more presciently in Hamnet than the section that recounts the travels of a flea. First jumping from a pet monkey into the shirt folds of a sensitive Manx cabin boy in Alexandria, it stows away on a ship. There it breeds, and its offspring nest in the dirty rags used to pack a shipment of Venetian glass beads bound for England. The glass, rags, and fleas change hands as far north as York, and as far south as Kent. Some are delivered to Warwickshire, where a merchant’s wife allows to Judith to see them. One of the flea’s offspring, infected with plague, bites Judith, then, presumably, Hamnet. And through this uncanny sequence of events, the story of Hamnet is set in motion.

Hamnet the play doesn’t bother with any of this. At one moment Judith is sick, then she is well, while Hamnet unexpectedly falls ill and dies. The flea’s story needn’t necessarily be included in the stage version, but there must be something illustrating the oddity and mystery of this story. One is led to believe this is the intent behind the occasional sequences of cool lighting and the sounds of children’s laughter that pepper the play, but they’re a paltry substitute. The play’s attempt at alchemy comes off as no more than what it is: staged tricks. Cheap, rote, unable to fully explain, and uninterested in trying. The world of the RSC’s Hamnet is, ultimately and accidentally, a prosaic world, where a child’s illness is ordinary and a mother’s grief is underwhelming.

This is also a world where a playwright father’s cathartic masterwork is clumsily fit on top of his attempt to come to grips, rather than a search for a way to fill the gaps left in his life. Hamnet the book spends time unraveling the parallels between the Danish prince and Shakespeare’s late son, revealing how Hamlet was Will’s earnest attempt to map a way out of his grief. Hamnet the play assumes this same relationship, but almost none of it is dramatized on the stage. But then, this may be good enough when you create theatre not to make sense of this sea of chaos enveloping us, but to satisfy those who already have a robust life raft.

We aren’t so terribly removed from the opposite kind of theatre. A quick scan through British drama during the 1960s and 70s, and for much of the 80s, reveals productions that challenged audiences (emotionally and intellectually) and scandalized censors. These were, naturally, years where the relevance of live performance were called into question by film and television. Writers like Caryl Churchill and Edward Bond, and directors like Peter Brook, were all aware of the tension created by this new technological-cultural reality. Rather than submit, they and a flourishing grassroots theatre movement insisted on the unique ability of the stage to touch the raw nerves of experience, unmediated by film and camera, particularly in a world where stability was proving illusory.

One must wonder — or, more precisely, imagine — what might have been possible had the RSC’s Hamnet dared to grapple with the world in this manner, to stand in this fecund lineage. It wouldn’t have filled these ghastly holes we walk around with, but it might at least have forced us to acknowledge them to ourselves and each other.

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

January 5, 2024

Word/War Games

“Whosoever destroys one soul, it is as though he had destroyed the entire world. And whosoever saves a life, it is as though he had saved the entire world.”

That’s from the Talmud, commonly attributed to Hillel the Elder. But the Talmud being the Talmud, there is debate on what it means, about which translation or interpretation is most accurate.

Some insist that the proscription only applies within the Jewish community: “Therefore, Adam the first man was created alone, to teach you that with regard to anyone who destroys one soul from the Jewish people, i.e., kills one Jew, the verse ascribes him blame as if he destroyed an entire world.”

Then there are the simplified, Hollywood versions: “Whoever saves one life, saves the world entire,” the version cast about in Schindler’s List, a convenient way of sidestepping the uncomfortable fact that the man who saved a thousand Jews was also a Nazi war profiteer.

But it is the first version that has stuck with me. Eloquent in its simplicity, it reads as an ethical and philosophical thread between the particular and the universal, the individual and the totality. It’s an encapsulation of the worldview sketched by Walter Benjamin in his “Theses on History” on the one hand, and his “Critique of Violence” on the other. It is also an ethic that drew me closer to Judaism, as the idea of converting became a genuine goal, an act that would put me right with myself and the world around me.

Hence the pain and rage of now, the feelings of existential displacement. You see, according to the United States House of Representatives, not only does holding the first interpretation make me not a real Jew, it makes me an antisemite. Elon Musk can fart all manner of Jew-hating drivel onto his keyboard and get praised by the Anti-Defamation League. But speak on the part of the 22,000 worlds destroyed — at least a third of them having gone round the sun only a handful of times — and you are nothing more than a pariah, responsible for every crime against the Jewish people.

November 30, 2023

Thousands More Sailing

Those who look at our prosaic existence and think that life has lost all poetry might consider the following. Shane MacGowan got to live one day without being forced to share this mortal coil with Henry Kissinger. It is a sign that some small thread of the cosmos, the universe, or whatever we call this seemingly random collision of causes and effects, bends toward the just and the beautiful.

True, both were men whose respective longevities would leave onlookers agog. “How the hell are they still alive?” we ask ourselves. But there, the similarities end, more or less entirely. Kissinger died at the age of 100, flabby and sedentary, like an over-puffed toad, his heart kept pumping through some combination of gold-standard medical care and a daily dose of blood from an eviscerated Cambodian child.

MacGowan, meanwhile, radiated all manner of unprocessed damage. He could put himself through a stunning amount of pain, be it a sliced-off earlobe at a Clash show, teeth so rotted you wondered how he ate, or infamous and intractable alcoholism. Watching him gyrate and tilt and slur his way through performances with the Pogues, it often seemed that this gangly fucker was keeping himself alive only through sheer willpower so he could rail against the world that created him. That he made it to 65 is, considering everything, rather remarkable.

Tributes to Kissinger are coming from the most craven and cruel. Biden, Von der Leyen, Bush, Netanyahu, Blair; their praise sidestepping his mountain of corpses because if it didn’t, too many might ask why they and Kissinger weren’t all delivered to the dock at the Hague long ago.

MacGowan’s tributes, meanwhile, come from all the right people. Irish President Michael D. Higgins, one of the few decent and humane heads of state left in Europe, said he “will be remembered as one of music's greatest lyricists... The genius of Shane's contribution includes the fact that his songs capture within them, as Shane would put it, the measure of our dreams…”

We might feasibly say that without men like Kissinger, there would be no need for poets like MacGowan. Whether we’re talking about leftist governments overthrown in Chile or bombs dropped across Southeast Asia, men like Kissinger are in the diaspora-making business. There is a lot of writing, research, and thought dedicated to the phenomenon of diaspora — its spread, its fissures, how it winds its way through the cracks and crevasses of modernity. But whether it is African, Jewish, Palestinian, or Irish, it is too seldom acknowledged that diaspora only arises out of calamity, of regions colonized and pillaged, people driven from their homes, heaved into the winds of migration.

As for the diaspora’s denizens, what choice do they have other than to survive? But survival isn’t just a matter of a roof and food. Those are just a matter of keeping the body going. The mind, if it isn’t to shatter, needs stories, poems, songs, something that connects its present place with the nebulous idea of “home.”

It’s a messy process, often improvisational, forced to work with only what you’ve strapped to your back and what you can find in front of you. Inevitably, it mashes together what could have been with what is and what could still be. Regrets about not joining a liberation army back home channeled into slam-dancing and howls for anarchy transform into a sharp blend of folk instrumentation and punk aggression. You’ll have no lack of ideas for lyrics: the songs from back home that enrage or sadden, the backbreaking labor you’ll have to perform, the postcards you’re mailing of wide open skies from dank rented rooms.

Some of it may get you banned from the BBC. And how you deal with the pain may get you kicked out of your own band. But you’ll manage to mine something sublime out of a wrecked life. It shouldn’t be necessary, but as long as some men think their own power is worth the death and displacement, it will be.

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

That Ellipsis… will be taking a break through the month of December. There are several reasons — the holidays, getting a few affairs in order, catching up on other projects, making sure I have ample time to both mourn Shane MacGowan and dance on Kissinger’s grave. But rest assured: not only will I be returning in 2024, I’ll be instituting a much more rigorous publishing schedule, including more material for paid subscribers. So if you haven’t subscribed, now’s the time to do so.

November 9, 2023

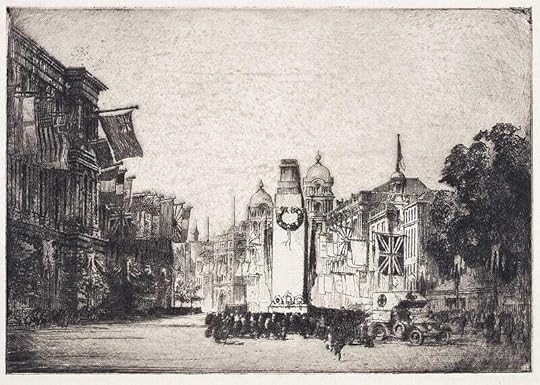

How to Destroy a Cenotaph

We weren’t going to say anything. But you’ve made that impossible. You, with your sanctimony, your hollow reverence, your Home Office howling.

They say the dead cannot speak for themselves. Hence the need to commemorate, memorialize, honor. And normally, we don’t mind. We may wince, shudder to ourselves, count the poppy pins, whisper about whose grief seems genuine, though most of the time, even false grief feels appreciated.

There’s a limit, though. Even for the dead.

We can take more slander than most. We have no choice. Our stories are in the ether; there is no clinging to them. The Tommies who cried to a mother we tried to be brave for. The trench soldiers who called over the top for a truce on Christmas. Those of us left strung from barbed wire while captains moved pieces on maps and got drunk on the company rum. Those of us who froze in the Baltic winter, or staved off heat exhaustion while the brass starved the communists in Malaya, or turned to skeletons in the Iraqi desert.

For many, too many, the ceasefire always comes too late. So many in fact that you can only bury us in an empty tomb, turn us into a metaphor, a present absence, sealed off with giant marble slabs.

And now you say the slab is insulted. By whom? By the people who think we are already too many? Who cannot lose count of the dead?

As if Death wraps itself in any flag. As if it defers to those of us trained to aim a rifle.

You don’t honor us. Only the guns we carried, the bombs we dropped, the landmines that tore the muscle from our bones. You use us now just as you used us then. And we know – bitterly, we know – what it is to be used.

Every single one of us were told that we were preventing atrocity.

Every single one of us was lied to.

They say that the dead cannot speak for themselves. But they can be brought back, if only by those who remember – really remember. Those who feel the massive gash we left in the earth when we disappeared, who can feel it getting larger, deeper, more bloody, the torn roots turned to sinews.

Let them come from miles away. Let them hoard and mill around this slab, around us, and we around them. Let them march and shriek and shout so much that they shake the ground that traps us. We can only hope that they stop our ranks from growing.

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

November 7, 2023

Untitled (For Gaza)

When I read the news,

it’s wrapped in sackcloth,

the color of charcoal.

A little darker every time.

I dread when it turns pitch black:

the last dispatch,

signal that the electricity’s run out,

the borders shut tight,

and ancient cities

about to be torn in two.

The truth has finally broken.

It will take years to walk again.

But, sure and inevitable,

its questions will whisper

like dust:

How did this happen?

How did you let it happen?

How could you let “never again”

turn into “again, and with enthusiasm”?

And we’ll have to answer.

We’ll have to remember.

How humanitarians saw terrorists

around every corner:

street vendors,

daycare workers,

doctors…

The 10,000 dead,

the trauma wards leveled,

the schools,

the refugee camps…

Olive trees crushed under rubble.

I’ve only just arrived,

but I was at Sinai…

so I’ve been told.

Others are coming to join me,

schlepping themselves through the Rafah crossing,

their stories strapped to their backs.

By the time they arrive,

only one in five will still have a name,

their faces scratched out.

Finally, I’ve earned the right

to be angry with G-d.

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

October 25, 2023

The Mosquitoes are Exactly What They Seem

In the Coen Brothers’ uber-symbolic Barton Fink, our titular idealistic-but-nebbishy playwright (played by the great John Turturro) comes to 1940s Hollywood to write a big studio wrestling picture. He spends his first night in a run-down hotel, boiling in a heatwave.

Arriving at the studio for his first meeting with the studio head Jack Lipnick (a memorable Michael Lerner) he is asked what the hell is wrong with his face. Barton tells him it’s a mosquito bite. “Bullshit,” retorts Lipnick, “mosquitoes breed in a swamp, this is a desert.”

The cliche observation is that, culturally, Los Angeles is both. But in the film, the mosquito is what everyone around Barton denies about LA, even if he, sinking into isolation and madness, can see it clear as day. It won’t leave him alone. It wakes him up in the night. It bites him and leaves him itching. It lands on dead bodies lying next to him in bed.

I’ve been thinking about this sequence a lot lately. I spend lots of time outside for work, including right around sunset. Living on the East Coast and the Midwest, I was used to mosquitoes, even if I, like just about every sane person, was driven to annoyance by them. Just one more reason to hate the humidity.

My first two summers in Los Angeles were more or less mosquito-free. I chalked it up to the dry heat, which most locals confirmed. The fascinating desert surroundings made a difference; it was another reason to fall in love with the place. These pests need more than heat to thrive; they need water and moisture. This year, though, has been uncharacteristically humid. Again, the locals confirm it. And with the humidity comes that whiny hum, the pinprick bites, the itching that becomes more un-ignorable the harder you try to ignore it. The fevered swatting, the obsessive scratching.

It’s a minor annoyance really, until you remember that mosquitoes carry Zika and West Nile virus. “I’m just being neurotic,” we say to ourselves. But that’s the point. Neuroses seldom spring entirely fictional dangers. They may be amplified, exaggerated beyond any reasonable level, but they all have at their core a fairly reasonable fear. A student in the San Fernando Valley died of West Nile in September, the first of the year. A tiny proportion of mosquitoes carry the virus, but the more mosquitoes out there, the more likely it is to be bitten by one that carries it.

And the mosquitoes have definitely thrived lately. It’s because of an uncharacteristically wet summer, including a tropical storm. Despite all the panic among Angelenos, Tropical Storm Hilary was almost literally a damp squib, leaving minimal damage and no injuries. It did, however, leave plenty of water for mosquitoes to breed.

As I wrote at the time, the fact that an earthquake struck in the middle of an underwhelming Hilary was a reminder that this is a city on an ecological and geological edge. Disaster rarely unfolds all at once.

One must marvel at the mosquito: it is well-suited to what it is meant to do. You might call it the mirror image of the honeybee. For while the latter has evolved over hundreds of millions of years into a species that can elegantly and efficiently pollinate a dizzying array of foods for just about every other life form on the planet, the mosquito has perfectly gestated to sicken and spread disease.

For 200 million years, it has been a bloodsucking insect. It is difficult to imagine the Orkin man successfully doing battle with this level of natural design. But some natural historians assert that, prior to the rise of Europen colonialism, it was not a global pest. The ships that brought conquistadors and new diseases also brought with them mosquitoes.

If true, then it is grotesquely apt. Diseases transmitted by mosquitoes — most notably malaria — were both aided by and helped assist the spread of the British empire through Africa and the Indian subcontinent during the reign of Queen Victoria. The same with US imperialism in the Philippines, and elsewhere in Asia. Epidemics of malaria wiped out hundreds of thousands, their immune systems already weakened by forced labor and starvation.

Malaria is easily treatable today. The same cannot be said for Zika or West Nile. And like Covid, like the mosquito itself, these diseases evolve and find ways to break through the safeguards of what we call civilization.

There are greater tragedies in Barton Fink, though we only learn of them in passing. Fink’s writer’s block turns his own head into a claustrophobic cell, and we’re trapped in it with him. We aren’t sure if any of the slowly creeping horrors around him are real. The woman lying dead in bed with him. The cops that tell him that his neighbor is a serial killer (John Goodman). Are they real or just another tangle in Fink’s slowly unraveling mind? It’s difficult to believe all of this started with a blank page. A blank page he cannot fill and cannot leave alone.

Then comes a cursory realization: we’re at war. While Fink maniacally tried to fill the page, the attack on Pearl Harbor took place. Fink is brought into Lipnick’s office. Not only has all of the studio head’s previous gregarity vanished, he is wearing an army uniform, albeit one that he had the people in wardrobe make for him. Even the most rabid patriotism is a put-on in this town.

With military gruffness, Lipnick admonishes Fink for turning in a script which we are led to believe is a rehash of his stage play. “It won’t wash” he plainly tells the writer, despite having previously praised his idealism.

Obsessions can be easily traded out. The longer we scratch at them, the more easily discarded they become. Which isn’t to say they needle us any less. In fact, you could rather easily say that grand tragedy — wars, disasters, moments when the ground comes out from beneath us — needs the minor annoyances to remind us of the damage it left in its wake. At first, the enormity of loss and fear dwarfs the itches and scratches. We find it easy to ignore them as we confront the reality of grief and terror.

Over time, we learn to cope. We are surprised one day to find ourselves thinking of something other than what happened in that horrible moment. It never completely goes away, but we can keep going forward, but again, it never completely goes away. Almost like an irritant.

Then we shame ourselves for treating tragedy like an itch. Shouldn’t we be completely unable to let it fade like this? Shouldn’t such monumental loss create an unbridgeable chasm in our psyche? The only thing that can prevent us from becoming cold and callous is to fixate on it, never let it heal, scratch until it is raw and bloody. At least that’s what we tell ourselves.

Even in near-miss tragedies — those we thought would ruin lives but somehow let us escape — we never entirely avoid them. In some ways, the skin of our teeth is just a placeholder for when the cosmos finally decides it’s your turn. It’s one of the reasons for the disbelief when the total weight of events finally comes crashing down. The first human being to contract coronavirus likely just thought it was a nasty case of the flu, something that would pass in a matter of days, the kind of experience that at worst forces them to play catch-up next week at work.

We have long pretended that the grand accomplishments of history can somehow hover apart from the changing of the seasons, the natural rhythms of the atmosphere. Sure, more people today remember Shelley’s “Ozymandias” than do the Pharoah Ramesses II, but never mind all that. Artists and poets are prone to catastrophizing, don’t you know? As for climate change, you needn’t worry if it is going to have an impact on your life. Even if it already has.

Back in the real world, this much we know. One of the few things we don’t usually have to worry about in LA is making itself known in all its irritation. It’s not like this city has ever been entirely devoid of mosquitoes. Urban development unavoidably creates damp and warm corners. Until recently, those damp and warm corners have been minimized. Getting bitten was likely accompanied by a brief thought of “was that really a mosquito? In LA?” Now, it’s just one more thing to get used to in a city steadily filling with more and more irritants. Some are little more than just that: irritants. Others are standing in for something bigger, and potentially more terrifying.

Climates change. We know that now. And with them, so do our expectations for what to fear. That voice in the back of your head that says this could be catastrophic? Listen to it. Consider it. Ponder it. Argue with it if you will, scratch it if you must, but do not dismiss it.

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I am presenting my paper, “A Great Composer of Time: The Post/Anti/Humanist Socialism of Jóhann Jóhannsson,” at Historical Materialism London in just a few weeks. More information about the conference can be found here, but I will be part of a session on Friday, November 10, at 4:15pm GMT. Anyone planning to be in London around that time is encouraged to attend.

October 16, 2023

Truth or Death

On October 5, I posted a short story – originally appearing in the latest issue of Locust Review – about a young Jewish man during the first hours of the Nazi invasion of Prague. Desperate, and likely guided by some cosmic force, he runs to the attic of the Altneuschul. Here he finds the dried, dusty clay remains of the Golem of Prague, constructed and brought to life 300 years earlier by Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezazel (a.k.a. the Maharal).

The legend of the Golem is one of the most enduring in Ashkenazi Jewish literature. The original story is that Rabbi Loew shaped and breathed life into it to protect Prague’s Jewish quarter from antisemitic attacks, which it did, before going into a mindless rampage attacking everyone in sight, Jew and gentile alike. The Maharal, seeing what he had done, managed to pacify the clay beast, and reaching up to its forehead, smudged the aleph in the Hebrew word inscribed there. Emét became mét, reverting the Golem into an inert lump of dirt and clay.

The story I wrote pivoted from another, more recent legend of the Golem, an unofficial sequel to the original. In that story, two Nazi soldiers ventured into the Altneuschul’s attic, wondering if the legends were true. They were never seen again.

Obviously, anyone can pick out analogs for the Golem throughout literature and pop culture. Mary Shelley was influenced by the myth when she wrote Frankenstein. The Golem is a mod in Minecraft. Recently, the tale has experienced a revival among younger diasporic Jews, both as a symbol of self-defense and as a cautionary tale. Adam Mansbach has recently published a comedic novel about a Brooklyn art teacher who accidentally animates a clay behemoth of his own while stoned.

Predictably, there are more recent parallels between the Golem and artificial intelligence. It is an apt comparison, effectively capturing the anxieties of AI: something with helpful intent behind it, spinning beyond our control, with perhaps disastrous results. Is the Golem Skynet, or the reprogrammed T-800 model sent back in time to save John Connor?

Two days after I posted the story, Hamas broke through the barrier around Gaza. We know what happened next. And what came after. I try to post something new here every Thursday, but last week, I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Things were happening too fast, the fears too overwhelming. Writing about unfolding events seemed futile, but so did writing about anything else.

As Netanyahu’s far-right government bombs and invades Gaza – an enclave where over half the population is under 18, where all exits have been sealed off, currently deprived of food, water, and electricity – the comparisons with 9/11 resonate with me. The ferocious beating of war drums, baying for revenge, the doublespeak that mourns civilian lives on one end while dismissing them on the other, the full-throated refusal of sanity. It is, in the midst of all this, impossible to ignore that something is emerging which will ultimately be impossible to control.

The day after Hamas burst into Israel, Hamilton Nolan wrote at How Things Work that we should retire the word “terrorism.” He received some predictable flak from people who like to think themselves his journalistic peers, which in some ways proves Nolan’s case. We’ve spent the better part of the last quarter century being bombarded with simplistic terms like “War on Terror,” a term that strips away nuance and historicization, often even ignoring basic causality. I honestly don’t think I can do better than Nolan’s own scathing description:

No matter what you think of America’s history in the Middle East or of Osama Bin Laden or of the Iraq War, the term “The War on Terror” fails as a basic unit of journalism because, rather than attempting to accurately describe something, it instead dips an entire geopolitical epoch into a vat of acid and waves around its ruined corpse in front of readers, as an introduction. It is the journalistic equivalent of attaching your friend’s birthday present to a Molotov cocktail and hurling it through their window to deliver it to them. When you ask them what they thought of it, you should not be surprised to find that their impression was tainted from the very moment they received it.

The anti-war left – isolated as it was during the years following 9/11, at least until the US turned its attention to Iraq – rightly turned the rhetoric of the “War on Terror” on its head. We argued that it was, if anything, a War Of Terror, that the only real difference between a soldier and a terrorist is a matter of perspective. We would cite the scene in The Battle of Algiers where a captured leader of the Algerian resistance says he’ll exchange bombers for handbaskets.

The impetus was basically correct, but looking back, I wonder if all we did was reinforce the meaningless ubiquity of “terrorism.” Thirteen years before the attacks on the Twin Towers, in his short 1988 book Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord was already suspect of the word’s loaded vagary.

“Such a perfect democracy constructs its own inconceivable foe, terrorism,” wrote Debord. “Its wish is to be judged by its enemies rather than by its results. The story of terrorism is written by the state, and it is therefore highly instructive. The spectators must certainly never know everything about terrorism, but they must always know enough to convince them that, compared with terrorism, everything else must be acceptable, or in any case more rational and democratic.”

Some context is warranted here. Debord’s original The Society of the Spectacle, published in 1967, was a passionate and often dense critique of how the commodity form had warped everyone’s view of daily life, society, and history. Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, published twenty years later, it just what it sounds like, updating the critique to a moment of full spectrum Cold Wars, rising neoliberal austerity, and 24-hour news cycles. The whole concept of terrorism, then, as conceived by the state, is deployed as a component of the spectacle, the practice – essential to commodification – of alienating us from history, turning it into something done to us rather than made by us. It is a term that obfuscates with fear more than describing what is happening and why it is happening.

Considering that Debord was writing just before the Berlin Wall started to crumble, it is impressive how prescient he is in Comments. As the Soviet bloc collapsed and the Cold War ended, as the big bad boogeyman of communism was no longer viable, the West needed a new enemy, someone or something that could excuse the failures of liberal capitalism, with its growing inequalities and declining democratic participation (Debord was obviously being sarcastic when he wrote of “such a perfect democracy”). It only took a decade for governments to realize that “terrorism” fit the bill.

But of course, “terrorism” is a far more amorphous concept than communism. It doesn’t emerge from a particular type of state. It isn’t a coherent movement or even an ideology. Just about the only consistent, defining feature is there in the name: terror. It is the use of not just fear, but of all-encompassing despairing fear, the fear that your entire world is ending, that the void is wafting through the air. Ubiquitous, but amorphous and pliable. Spectacular, in both our more conventional definition and that of Debord.

In the days since Hamas’ attack, celebrities on social media – avatars of the spectacle par excellence – have posted pictures of wounded children, ostensibly Israeli. “This is terrorism” they say, only to be informed that the pictures they are sharing are in fact of Palestinian children wounded in Israel’s ongoing bombardment. The posts and pictures are quickly deleted without comment. Presumably, Palestinians can never be victims of terrorism. Only its perpetrators. But if democracy’s enemy can be so vaguely defined, if its definition can be bent so easily and applied so selectively, how democratic a society are we really talking about?

Metaphors are imperfect things. We all recognize when one has been stretched too far, when we find ourselves accidentally substituting rhetoric for reality. When I first wrote and posted “An Attic In Prague,” it was intended as a rumination on just these imperfections as they applied to violence, an examination of the dyad that makes it both necessary and dangerously messy. The Golem of Prague story has always served this pedagogical role.

At the same time, I find myself stunned by the timing. For there is another valence to the Golem myth, particularly as it pertains to violence. It’s not so much in the violence per se, but the thoughtlessness with which the Golem commits it. Incapable of rational or independent thought – unable to reason, remember, or contextualize – the clay beast essentially adopts violence as its own logic. What starts as a means to an end becomes an end in itself, quite apart from human intent.

Key here are the values imprinted on the Golem; not the values of the Maharal, not even the values of Judaism. Rather, the values of the society in which the Golem exists are imprinted upon it. It is one of the reasons that the metaphor works for AI, illustrating that technology is neither good nor bad, but neither is it neutral. It speaks volumes that the words literally imprinted on the golem’s forehead are Hebrew for “truth” and “death,” implying a world in which there is no more than a veil between the two. No wonder it can so easily spin beyond its creator’s control.

In this reading, there is something of an affinity between the Golem and Debord’s spectacle. Still, the fact is that we have always reached for something — metaphors, ideas, systems of symbolization — to describe our propensity to create destructive forces that move beyond control.

E.P. Thompson, in applying the term “exterminism” to the Cold War push toward nuclear annihilation, clarified that it had less to do with the actions of this or that world leader (though these certainly play a crucial role), and more with the all-encompassing logic of mutually assured destruction that prevailed. In preparing to prevent nuclear destruction by building up our own arsenals, we made it more likely.

Others have already written about the way Thompson’s rubric can be applied to climate change, as well as the crazed, unsublimated desires to “sacrifice the weak” at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic.

All of the above were, in their own ways, expansions on the Thatcher-Reaganite dictums of “there is no alternative.” Just as a world of exploitation and inequality was the only option for running a society, so is the destruction wrought by nuclear catastrophe, climate disaster, or global pandemic.

Meanwhile, there is Mark Fisher’s formulation of “capitalist realism,” gaining currency since his death in 2017. This was his attempt to map how “TINA” had gone full-spectrum, seeping into the fibers of daily life to the point where any other way of living becomes unimaginable. It too has been adapted to describe the prevailing approaches to climate change and global pandemic.

For our purposes, we might apply it here to the insistence of military intervention even in the face of its obviously disastrous consequences: imperial realism. Empire literally soldiers on despite all evidence that it has made the world a more dangerous place.

It strikes me that all of these heuristics are actually just describing the same thing. Or maybe just the same dynamic. Spectacle. Exterminism. Capitalist/imperialist realism. The Golem in its more harrowing iterations. All are a kind of Rashomon, describing different aspects of a world that pretends at democracy and human rights, filled with leaders declaring the gospel of protection, unable to see the horizon they themselves have walled off. This is less a world of people’s idealism than a world of people dictated by ideology, the possibility of an alternative laughed away.

Up until a few days ago, it was unspoken consensus that the “War on Terror” was a dismal failure, producing civil wars and fragile puppet governments, and strengthening some of the worst authoritarian regimes in the Middle East. Some (Iran) are infamously opposed to the United States, while others (Saudi Arabia) are its staunch allies.

Or look at Haiti. In return for hosting the first successful slave revolution in modern history, the small Caribbean nation has spent the past 200 years punished by the US and Europe. Deliberate destabilization in the form of US-backed coups and interventions has spun out to such a degree that it is currently impossible to deliver aid to Haitian hospitals without permission from local warlords.

Nor does the barbarism stop at the borders of the North Atlantic states. The “with us or against us” mentality has had a particularly toxic ferment in the former Soviet bloc. Mass disillusionment has put initiative in the hands of some of the most hideous political formations. Take Hungary. Under Viktor Orban, the country has embraced open right-wing nationalism. Orban himself has peddled the Soros myth, and destroyed the library archive of the late Jewish Marxist theorist and literary critic Georg Lukacs on the grounds of explicit anti-Jewish conspiracy, all while maintaining close relations with Israel.

As for Israel itself, it makes its own moves within the imperial realist chess match. A thorough piece at Jonathan M. Katz’s site The Racket illustrates this through the concept of “the iron wall,” which has been central to Israel’s security strategy from the state’s inception. Hamas’ own origins in the late 80s include tacit and active support from Israel as a way of weakening secular forces like the Palestinian Liberation Organization. And we cannot forget Netanyahu’s ongoing attempts to consolidate judicial and legislative power within Israel, which are of course perversely framed by him and his supporters as a matter of national security. Now, he vows to “flatten Gaza,” and looks hellbent on keeping his promise. Stunted democracy is further curtailed to save it, terror promises to keep terrified people safe. There is no attempt to reconcile with a full past because we cannot reckon with what won’t be remembered.

The Golem lumbers on. Nobody is guiding it, though some pretend to. Once again, the borders between truth and death are blurred. One will have to win out in the end, and I’m not convinced it will be the one we want.

October 5, 2023

An Attic in Prague, 1939

This short story, published in the latest print issue of Locust Review, is behind a paywall. Meaning that the only ways to read it are purchasing the latest issue, or becoming a paid subscriber here at That Ellipsis… Luckily for you, yearly subs are 25% off for the month of October. off a yearly subscription. That’s 40 dollars for a yearly subscription instead of 50. Even better, those who opt for a Founding Member subscription will get a half-off price, paying 100 up front rather than 200.

Even in this cacophony, it’s the silence that unsettles most. If only because it won’t be long until it’s pierced again. Screaming, shouting, tires screeching, panicked footfalls, sporadic gunfire. If there were ever a silence that could threaten, a kind of quietude that, for a few seconds or several minutes, promises to split the skull of whomever steps in its way, this is it.

It was the silence that told us this night was coming. The things we said to ourselves in the hope that the dread will quiet. They’ll never come to Prague, we assured ourselves. They only want the Sudetenland. But in between, in that small pause, we could hear the coming years screaming at us. And we knew that there would be hundreds of thousands, in fact millions, who would never live to know how empty our reassurances were.

I would be lying if I said that I think this will work. That this mythical mound of dirt could somehow come together and move, let alone keep Josefov safe. I can’t even say what it is that draws me here now, except the knowledge that everything else has failed. The facile words of Beneš, the blinkered confidence of the Communists, the pious promises of rabbis whose words I started dismissing long ago.

When I heard that the Wehrmacht had reached the outskirts of the city, I froze. Out of fear? Frustration? Despair? Who knows? Whatever it was that bolted me to the floor, I could do little more than stand in front of my window, my eyes glazing over as panicking people ran in and out of my sightlines.

The only thought I could make myself think all the while was that this was always going to happen. Nations are as finite as they are fleeting. The last war, and countless before, taught us this. Still, that this one could vanish into thin air, that it can cease to exist, as this one will for the next several years, is enough to leave you forgetting to breathe.

Only when they had taken the city’s center, marching down Wenceslas Square, was I finally jolted into motion. It wasn’t thought that moved me, not even instinct. All I knew to do was run in the direction of the Altneuschul, of that building I hadn’t entered since my teenage years. When I burst through its doors, I had no idea where I was going. Only that within seconds I was racing up a staircase I had never noticed before, through the doors to an attic I had only heard about.

And still I didn’t expect the legend to be true. Myths and fairy tales are a child’s things, and I put them aside a long time ago. When I saw this table, mounded with dry and cracking clay, for several minutes I could only stop and stare, mouth open, at this proof that the stories were real. Real as my breath, as fire, as the gunshots outside, as the barking of German orders echoing down the narrow streets. It was those sounds that brought me here, when all other options from kind persuasion to armed force have disappeared, when myth is all we have left.

Most of us can never contemplate death like this. We tell ourselves that it isn’t the rational thing to do. What really prevents us is fear. Pure, simple, and abject. That idea that something may become nothing. But three hundred years ago, the Maharal – though he could not have been the first – reversed the sequence. He molded these arms and legs thick as tree trunks, this squat head, this hulking torso. And he alchemically converted the inert into the moveable, the dead into the spirit, the truth of survival, adding to a throughline that endures through centuries of shapeshifting Talmudic bickering.

And yes, I know very well how those stories ended. The bloodshed, the heartbreak and homes destroyed beyond repair by the very thing that was made to protect us. This pile of dirt in front of me is capable of ghastly, wonderful things. Every time it crosses the border between dream and nightmare, it becomes a bit more real. Until it arrives here, laying on a table right in front of me.

Perhaps we can only look these gruesome truths in the eye at our most desperate, when we’ve put aside all the reason and the urge to explain that we’ve cribbed into our minds, rationalizing away the mystical happenstance that lets bad things happen to good people. Maybe we don’t have to understand. Maybe teaching ourselves the logic of the unknowable is less important than opening up to its wondrous terror, stilling ourselves, more and more, until we can feel it resting in our bones. To hear, in the terrible quiet, what lies on the other side in all directions. To know that survival is less about a collection of individual lives, and more about the extramundane trajectory of history you reach for.

Three years down the line we’ll hear of those in Warsaw. Knowing they were assured death, they will figure it better to die human, facing the monster that shoves them into hovels and forces them to march toward a quiet and degraded end. That’s what this is. This anguished, undefeated realization that we can no longer ignore the option of death.

Perhaps this loam giant, this man-made half-man, this – let us say it… golem – will do what it did last time, rampage through our streets without anything like discrimination. But it may also keep its own word, the promise implied in its creation, distinguish between those who need protection and those who need to die in order for that protection to be provided. It is rarely so clear cut. But while I carve an Aleph into this hulking thing’s forehead, undoing the erasure of three hundred years ago, turning “mét” to “emét,” I can only hope that my own blurred, incomplete view into the future proves itself out.

Decades from now they’ll tell more legends and myths, more whispered tales about the Gestapo officers who tried to enter this attic. Some will say that they were sent there by Hitler himself, his occultist proclivities egging him on, perhaps with some endgame of harnessing the Kabbalah for the aims of the Reich. Others will say that it wasn’t the Gestapo, but simply two stupid soldaten who let their youthful curiosity lead them up here, seeing if the legends were true.

Either way, be it Gestapo or Werhrmacht, on higher orders or simply wandering dumb, they’ll never leave this attic alive. They’ll be torn limb from limb. The final thing they see will be this clay ogre’s massive foot caving in their skulls as they howl like babies for their mothers, trying to reach for their revolvers with arms ripped from their sockets. Two fewer Nazis, and with them, maybe a few more lives – of Jews, of socialists, of vagrants or queers – spared.

What the stories will forget, is me, that third man. The one who can hear them racing up these forgotten wooden steps right now, barking German at each other. That one Jew, that one man, that one human who, knowing he was facing oblivion, grasped the cosmic hubris that keeps one free.

October 3, 2023

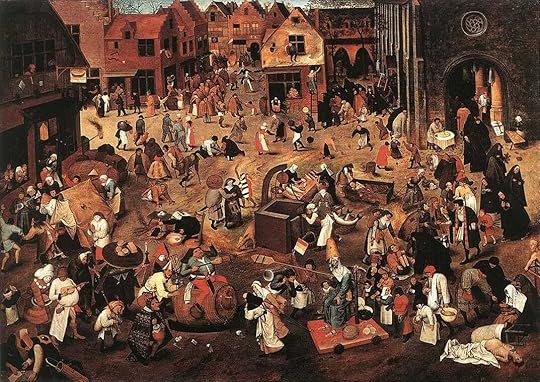

Carnival

For the month of October, new paid subscribers to That Ellipsis… will get 25% off a yearly subscription. That’s 40 dollars for a yearly subscription instead of 50. Even better, those who opt for a Founding Member subscription will get a half-off price, paying 100 up front rather than 200. So if you’ve been waiting to read my Barbenheimer review, my thoughts on movies about terrible rich people, or if you’re hoping to get access to my upcoming post on the rising of the bears, now is the perfect time.

A recent article in Smithsonian magazine tells a neglected story: that of the radical roots of today’s beloved Renaissance fairs. It’s not the first time these origins have been chronicled; Set the Night On Fire, the magisterial history of Los Angeles in the 1960s by Jon Wiener and the late Mike Davis, does so in its chapter on Pacifica’s LA radio station KPFK. There’s also a book, cited in the article, titled Well Met: Renaissance Faires and the American Counterculture. But it is fascinating to think that, in a twisted way, were it not for some of the artists and workers internally exiled by McCarthyism, the Renaissance Fair as we know it wouldn’t exist.

To briefly sum up, the first Renaissance Pleasure Faire was the creation of Phyllis Patterson, and Doris and Robert Karnes. Patterson had left teaching in the public schools because she refused to sign the anti-Communist loyalty oath, while the Karneses had been hounded by the House Un-American Activities Committee for somehow “infiltrating” the youth center where all three had wound up teaching. Funded by KPFK – which had its own experience being hounded by HUAC – the first Faire, held in 1963, was on the five-acre North Hollywood ranch of Oscar Haskell, who had also been accused of membership in the Communist Party.

The early years included many of the trademarks we recognize in today’s Renaissance fairs: elaborate period costumes, performances of Shakespeare or commedia dell’arte (which Patterson had a background in), and an overall attempt to replicate the more revelrous aspects of European culture in the 1500s. Innocuous as it sounds, the organizers deliberately viewed it as a space of free education, culture, and expression. It was bound to rankle some of the more conservative onlookers, particularly as the festival grew and started to collide with the burgeoning counterculture of the 1960s. In 1967, when the organizers attempted to move the fair to bigger grounds in Ventura County, local conservatives campaigned to have it banned, and ultimately succeeded.

Today’s Renaissance fairs aren’t exactly insurgent, though this may only be because they are able to exist comfortably in the larger culture. Right-wingers have found a lot to enrage them in recent years, as they always have, but these kinds of events – which are often financial boons for the sponsoring companies – aren’t normally in their sites.

Still, phenomenologically speaking, the first Pleasure Faires’ countercultural affinities are fitting. Soviet literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin’s influential theories of the carnivalesque rely on the experience of medieval and Renaissance festivals. Emphasizing the base and grotesque, they were moments when social boundaries and taboos might be transcended. Though hardly a threat to the established order, they gave participants a sense of what life might be like were it done and lived differently.

It is also interesting to consider this in light of the Writers Guild of America’s recent victory in their strike against the Hollywood studios. It’s far from the last word – SAG-AFTRA is still on the picket line, and the studios will be looking for any opportunity to undermine the gains the writers made – but we should be clear that this was a very big win.

Like most Hollywood unions, the Screen Writers Guild (which later became the WGA) went along with McCarthyism, allowing its radical members to be blacklisted and purged. A generation later, with many blacklistees rehabilitated, the union sought to come to grips with this ignominious moment in its past.

That the Writers Guild stood aside and let its members get persecuted is particularly ironic considering that, if not for Communist Party members like John Howard Lawson, and sympathizers like Dorothy Parker, the union probably wouldn’t have existed. One of the themes I take up in a forthcoming piece on the writers’ strike is the inextricable link between labor rights and freedom of speech. It seems obvious to bring up – union and non-union workers alike are unjustly disciplined and fired for “speaking out of line” all the time – but it is especially central in the worlds of artistic and culture work.

On one hand, creatives will likely always try to find ways to create, and I mean this in the most unromantic way possible. Most of us have put a large amount of time and effort into honing a craft, to the point where, for many of us, it literally is all we know how to do to put a roof over our heads. Blacklisted writers used fronts, striking deals with other writers who would sign their name to their scripts. Acting teachers and theater performers – like Patterson and the Karneses – found ways to teach and build worlds outside the traditional avenues.

The challenge, often overlooked even in much of the left-wing discourse on free speech, isn’t just about finding spaces for these kinds of expression to flourish. Nor is it about some slow process by which these outsider experiences can find a safe, sanitized place in the world. It is both and neither. How does the carnival spill out into the rest of the world and, in the process, let the world be changed by it rather than the other way around? How does the subcultural become countercultural, and how does the counterculture vie for hegemony against the ideologies that tell us a world of rank exploitation and disaster is the best we can do?

Finally, what role to artists – conceiving of themselves and organized as workers – play in altering our sense of what is possible? Can it be done while also shunning the inane transformation of everything into an aesthetic or a pose? If we can figure that out, then we may yet have a snowball’s chance of making life itself the carnival.

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

September 28, 2023

Trembling Between Plagues in Los Angeles

But first, a plug. Starting now, and for the month of October, new paid subscribers to That Ellipsis… will get 25% off a yearly subscription. That’s 40 dollars for a yearly subscription instead of 50. Even better, those who opt for a Founding Member subscription will get a half-off price, paying 100 up front rather than 200. So if you’ve been waiting to read my Barbenheimer review, my thoughts on movies about terrible rich people, or if you’re hoping to get access to my upcoming post on the rising of the bears, now is the perfect time. And now, read this poem. Shana Tova.

1. Ink

Walked outside today, past a row of crumbling homes, observing the new year. Cracked paint, rotting wood, broken windows and dead, overgrown lawns. The street here is easy to miss, its signs obscured by freeway overpasses, its twists blocked by blinding glass.

Those who’ve sat here long enough will know the lives that have washed through. She knows she’ll always feel them (though is less sure of others). Some arrived after months floating aimlessly at sea, vague stories of tank treads that swallowed people whole.

Some came through deserts or rivers, the water cooling their blistered skin. Others were born here and never had any plans to leave, until they did. They raised children, mourned parents, wore scuffmarks into the linoleum and hardwood floors. Made meals for each other. Babysat their children.

She takes a book from the shelf, pen in hand, and makes another inscription on the title page. She leaves the words to dry on the table before walking out the front door.

2. Breath

There is only so much oxygen to go around nowadays, most of it hoarded by faulty ventilators and fires on the chaparral. Anytime it rains, neighbors rush out their front doors to breathe it in, gasping cool, fresh, and rare. You can hear the air hiss as it evaporates.

It’s been so long since she went outside (though not as long as it’s been for others). Everything is exposed in the light, vulnerable. The sun blinds, but it also sterilizes. At least for a time.

The hot air rushes into her lungs. She knows it will only get hotter as the ground keeps opening. But as always, there are people out there, shuddering and waiting, their necks craning upward in prayer for another storm. Quietly to herself, she recites the shema, then patiently sets off down Vine.

3. Sand

I heard of the ‘stone tape theory,’ the idea that ghosts are just pain and trauma, trapped in rocks. So I traced my finger along the concrete sidewalk for as long as I could, up to the end of the street. I strained hard, tried to listen, asked questions.

What is the difference between prayer and incantation? I couldn’t tell you, but I chanted both into the ground. Nobody answered. For five thousand years, nobody has answered.

Some call my reaction terror, but it was something more. Some places you can dig, but not here. We need the soil to soften. Claw at it hard enough, squeeze the cold layers of deep time between your fingers. Just don’t breathe it in. Valley fever lives in the dirt.

4. Ash

There’s smoke above the Hollywood sign. At night it glows orange and red. Come morning, it still somehow stands, ready to survey new catastrophes. It will be ten days before flames stop, and the sign will still stand, waiting for some new stranger to look up and wonder why this landmark manages to endure while so many others have become memories.

There’s a man dragging his swollen feet up Fairfax, a guitar slung over his shoulder. His stomach is empty today (though no emptier than it normally is) and his name is crumpled in a nearby tent.

Catching the eye of a rabbi walking past, he frantically renounces everything he’s had to remember, flinging verses into the future like upbraided cobblestones, against the door of every holy house that’s been slammed in his face.

Unfazed, the rabbi looks at him. ‘What took you so long?’ she asks. Then she smiles, her wrinkles framing her gray-green eyes as they light up. ‘We’re always in need of people like you.’ She touches his arm. In that instant, he sees what he’s always hoped, but never searched for.

5. Wax

This city… This monument of exquisite talking corpses, Babylonian trials, and dried-up rivers. There are few places to grieve, and even fewer to repent. Anything that might exist long enough is quickly cordoned off and forgotten. By the time we remember it’s just been paved over.

Closing the front door behind her, the rabbi takes a moment to notice the shadows cast through the window. Outside, the color of cracked paint continues to fade, and tree branches burrow through concrete. In here, everything remains beautifully still.

Outside, every scream is an audition, every grave diagnosis a chance to build an audience. In the midst of this, she can’t tell him whether the fires or the sickness will get him, the swords or the police batons, stupidity or old age. Will he grow roots or wander? Have peace or torment? Music or hunger?

Somewhere, searching, she knows, but can’t say. Gently, she blots the ink, closes the book, and places it back on the shelf to collect dust for another year.

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.