Alexander Billet's Blog, page 5

August 28, 2024

Definitely Shady

Oasis are reuniting, and it’s entirely the fault of one man. Of course that man is Keir Starmer. I’m only half joking.

There should be something utterly risible about this recent bit of music news. But somehow, when just about every cultural event makes itself so annoyingly unavoidable, shrieking in your face and daring you to ignore it, it’s often difficult to muster more than a shrug. This is surely the point.

Stepping back though, I cannot help but feel a kind of wry pity for Britain. This is an island that once fancied itself the pinnacle of western civilization, and had all the pomp and brutal violence needed to back it up. Now it’s a place that prides itself on being a backwater.

Thirty some odd years ago, when Oasis first started climbing their way up the charts, the country was at least trying to find a way to maintain its spot in the global cosmopolis without its empire. That was the whole grating point of “Cool Britannia” and Britpop. If it gave rise to insufferable groups like Oasis, it at least helped expose the world to the likes of Elastica, Suede, and Pulp (the latter of which is a band that can do no fucking wrong musically and I’ll fight anyone who says otherwise).

And now? Now Britain is the kind of place where people start burning down hotels because a few migrants are daring to shelter there instead of drowning off the cliffs of Dover. Yes, it was always that kind of place. Underneath the surface of even the most liberal (former) empire is the most basic and nasty forms of racism you can find, and Britain was never that liberal to begin with.

Now the last vestiges of the empire are juttering themselves loose from the mothership. Brexit has all but assured the return of Northern Ireland to the rest of the 32 counties. The main reason Scottish independence isn’t immediately imminent is because the Scottish National Party has imploded, but it’s only a matter of time until some other force manages to pick that mantle back up.

Between this and the unravelling of what is left of the country’s social safety net, it’s no wonder that people who wrapped entirely too much of their identity around being British are completely losing it right now. They want nothing more than for things to go back the way they were, even if that way never existed. They’ll impose it through rampant destruction if need be. And because centrists don’t riot over anything, I’m going to go ahead and say that Oasis’ reunion is the centrist equivalent.

Look, I will be the first to admit that Oasis’ songs could be extremely catchy, and it’s on some level understandable that you can still hear drunk forty-somethings caterwauling their songs in pubs late at night. Zoom out, though, and you have to wonder why this was the band that came to symbolize Britpop. They were the least interesting, the least experimental and adventurous, the most hidebound by their conceptions of what rock and roll “should be.”

This is, according to the band’s own history, entirely down to Noel Gallagher. When he joined the band, he did it on the explicit condition that he be its sole songwriter and front-man. It was a quizzical insistence given that he also insisted Liam continue as Oasis’ lead singer. Particularly because Noel can sing just fine. Hell, he sings their most recognizable song, “Don’t Look Back In Anger.” The video features Liam skulking in the background with a tambourine, reduced to an appendage, a cut-rate Bez. It all gives us a pretty good idea of Noel’s actual vision for Oasis, one he never had the spine to make reality.

Still, “Don’t Look Back In Anger” is a pretty good example of what Noel brought to the band. The song resolutely refuses to stray from the “verse-chorus-verse-chorus-solo-chorus” convention. The rhythm guitar is a basic and predictable barre chord progression, and the bass is all root notes. There is absolutely nothing even remotely risky or innovative in the song.

To be fair, it’s not like the band was trying to revolutionize music. Oasis got a lot of flak for sounding so much like the early Beatles. The opening piano part is, by Noel’s admission, ripped off from John Lennon’s “Imagine.” Even the song’s title is an inversion of John Osborne’s iconic 1956 play Look Back In Anger, a break in the dam that briefly turned the theatre into a receptacle of rage and dissatisfaction directed at what had become of the British way of life.

“Don’t Look Back In Anger” is an appeal to convention in every sense. From its predictable structure to its video’s set piece rockstar mansion to Noel’s own Union Jack guitar, this is a song that declares the band’s intention to behave. Particularly compared to what most other Britpop bands were doing. No wonder they became the genre’s poster lads. In the context of a slow-but-steady attrition against public funding for the arts and arts education, the truly patriotic British artists must learn to be comfortable in the middle of the road.

It was a role Oasis eagerly took up. Blur had a contradictory relationship with New Labour, Pulp’s take was more outwardly oppositional. Noel Gallagher and Oasis loved Tony Blair, a man who Margaret Thatcher once called her “greatest accomplishment.” More recently, Gallagher has become one of those sneering centrist dads whose hatred for all things left and egalitarian can only be explained by either their class position or a complete lack of basic sense.

“Fuck Jeremy Corbyn,” said Gallagher during Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party, “he’s a communist.” He also said that he wished Blair was still in politics so he could vote for him again, and that he’d rather reunite with his brother than have Corbyn run the country. Now he’s got Keir Starmer in power and Oasis is back together. Starmer is no Blair, but it wouldn’t surprise me if Gallagher were angling for another invitation to come party at No. 10.

Call it a return to his glory days. A Labour government in power, one that leaves his wealth intact. Starmer won’t be doing much of anything to help out most ordinary Brits, but I’m willing to bet people like Gallagher will be acting like he has. Blairism and Cool Britannia were themselves little more than vibes.

I may not know how people feel about Oasis’ reunion, but I do know for a fact that millions of young people in Britain feel trapped between a vague memory of how things were and what they are now. Between the hopeless expenses of higher education and the knowledge that it used to be (relatively) affordable. Between the promises of the National Health Service they learned about in school and the current months-long wait to see a doctor. Between the idea that the basic role of a functional society is to take care of everyone, and the “no entry” signs that seem to cordon off anything resembling a future.

They’ve heard that at some point, something has to give, and are asking, a bit more desperately each time, when that might be. Now, the universe replies: “Anyway, here’s ‘Wonderwall.’”

Header photo is from the video for Oasis’ “Wonderwall.”

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

August 21, 2024

Still Conventional

We witness them every four years, but the conventions of the two main American political parties are nonetheless deeply strange. Not weird. Just strange. Eldritch even. Part of it is the slapdash pageantry, the organization of enthusiasm for worldviews that range from the milquetoast to the downright sadistic. But this is mostly an outgrowth of what a deeply apolitical society America is.

Ideas and worldviews mutate when they aren’t exposed to light for too long, and regular press briefings are a poor substitute for fresh air. Every notion presented is either focus-grouped or circle-jerked beyond recognition by party leaderships in the name of giving a static and mythical people what they want. By the time any of these twisted policies make it into the larger discourse, they are at best clumsy.

Hence the protests. Even with all the limitations of “activist brain,” of jumping from action to action without regard for strategy, it encouraging to see the mad and screaming crowds that regularly congregate around both the Republican and Democratic National Conventions. John Berger once wrote of how mass demonstrations are designed to transform urban space, pulling it away from the sanctioned rhythms of commerce and official politics and suggesting a different vision.

Take the Republican National Convention of 2004, held in New York City of all places, during the height of the Iraq War. Compared to the contemporary political landscape twenty years later, this wave of protest seems positively quaint. Inside the convention were George W. Bush and Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld and all the other sneering ghouls who wanted nothing more than to trade out their penises for cruise missiles, trying to paint their grotesque agendas with some form of grace and dynamism.

Outside, 300,000 marchers. The tragedy in waiting was that most of them would end up voting for another awkward blueblood bobbing in the Democratic center who should have been wiping the floor with Bush. He would lose, and so would they. It was a stark difference from the energy and mood that emerged on that sweltering late summer day. These were some of the busiest streets in the world, now jammed with signs and chants demanding troops out.

In February of 2003, an even larger crowd had swarmed this city, again in protest of what was then an imminent invasion. Then, the crowds had broken through the lines of the NYPD, who had refused to grant permits to the march. It was difficult to forget eighteen months later. Moving crowds bring memories beyond the scope of individuals. Put aside your cynicism; you know this is impressive.

With all this in mind, it is rather dizzying seeing the various visions jockeying at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago right now. Depending on which angle you look, each proceeding portends a future wildly different from the next. Given the Democrats’ long-standing struggle to coherently present themselves, it is only fitting.

At one glance, it seems feasible that the Democratic Party of neoliberalism is a thing of the past, but this doesn’t necessarily imbue Harris’ rhetoric of economic populism with any substance. Maybe the optimists are right then a Harris administration will usher in a raft of progressive legislation. If so, then the question remains why their campaign is packed with the same Clintonian hacks who have given the party’s policies such disastrous shape. It also leaves one wondering why Tuesday’s lineup on the DNC stage was packed with Republicans.

How, exactly, is this a movement that can hold these erstwhile enemies and the likes of (an admittedly rightward-drifting) Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and others on the left-wing of the party? It’s not clear, but I’m not sure the Democrats want it to be. None of it works, in keeping with all of the mainstream solutions trotted out for climate change, refugee crises, or the rise of the far-right death cult. But maybe, just maybe, if we jam it all into the same space and frame it with the right amount of blue and red fanfare — like we’ve always done — we can make it seem plausible. At least until November.

Outside, thousands are demanding an end to the massacre in Gaza. Biden said they had a point during his speech. He was pandering. How could the man so committed to arming Israel do anything else? Those marching outside, and many of those inside, heard something hollow in his words. This may very well be a new Democratic Party, but the old one is still occupying the same space.

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

August 7, 2024

American Weird

Start, as we often do nowadays, with the words of Mark Fisher. Here he is in the introduction for 2016’s The Weird and the Eerie:

What the weird and the eerie have in common is a preoccupation with the strange. The strange – not the horrific. The allure that the weird and the eerie possess is not captured by the idea that we “enjoy what scares us.” It has, rather, to do with a fascination for the outside, for that which lies beyond standard perception, cognition and experience. This fascination usually involves a certain apprehension, perhaps even dread – but it would be wrong to say that the weird and the eerie are necessarily terrifying. I am not here claiming that the outside is always beneficent. There are more than enough terrors to be found out there; but such terrors are not all there is to the outside.

The problem with the American right is not, and has never been, that it is weird. Or at least that is not what is wrong with it per se. Any honest look at its past and present will reveal how insufferably obsessed it is with normality. From red scares to moral panics, it is clear that all ilks of conservatism and right-wing thought in America cling to the normal like a liferaft and a truncheon. It is both weapon and salvation to them. This is a lineage of political praxis that cannot tolerate deviation.

Still, Fisher’s definitions do help explain something about the contemporary right. His taxonomy of the weird and the eerie – both forms of the uncanny, the unheimlich – is plain. Both are defined by the slipstream between existence and absence. The eerie mostly pertains to that which should be but isn’t – think of how an empty street late at night makes you feel uneasy – while the weird is that which shouldn’t exist but, for some reason, does.

In this sense, there is something weird about the contemporary right. Think of the reports that Grindr was overwhelmed with traffic during the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee. If the correlations are as close as we think, then we find something that is both ludicrously tragic and very weird in the Fisherian sense. The archetype of the closeted gay conservative, filled with equal parts moral indignation, sexual repression, and deep-seated self-loathing, is a familiar one by now. To him, same-sex desire is a deviancy to be shunned, but it is also something that shouldn’t be there, but very much is.

So much of the American experience, then, is defined by the weird. There should not be white people here, but there are. There should not be a country this rich with this many homeless, but there is. On the flipside, from the perspective of the straight-laced and self-righteous, there should not be any immigrants crossing the border, but there are. The key factor here is repression. As long as there is repression, the repressed will find a way to return. This is neither good nor bad, but a simple fact, spoken plainly and without any hidden agenda.

Which is why the sudden Democratic Party penchant for labeling Donald Trump and his supporters weird strikes me as rather lame. It wouldn’t surprise me at all if Minnesota Governor Tim Walz’s sudden virality after doing so was at least partially behind the decision to tap him as Kamala Harris’ vice president. In the eyes of Democratic strategists, it likely reads as media savvy. Now, with him officially part of the ticket, the idea of Trump as weirdo is probably going to be permanently in the ether for at least the next three months.

Some on the left applaud the rhetorical move, and I can see why. But there are a few things to say about this newfound emphasis. First, it is going to get old very quickly, and therefore lose most of its bite. Second, it smacks so loudly of the Democratic playbook of the past few election cycles, which is to put a premium on just the right series of never-ending soundbites in the hope that they can drown the Republicans in rhetoric the same way Trump and company have the Democrats. Discussion of actual politics, of a quickly collapsing social reality, is treated like a complement to the style rather than the other way around.

In short, it is spectacle, the simulacrum of politics disguised as actual politics. Which puts it very much in line with politics as usual in this country and also, perhaps ironically, rather eerie, fitting seamlessly into the uncanny valley of the American political scene (where there should be substance, there is instead plenty of rhetoric). That Walz has been picked as Harris running mate is itself a surprisingly smart move, and one which will drum up enthusiasm among progressives and even some sections of the socialist left. It is probably predictable that Fox News is trying to fire back at the Harris camp by turning the weird label on his offhand, vaguely positive comments about socialism. But one wonders how long it takes for some of the solid stances Walz has taken as governor of Minnesota to get absorbed back into the wall of noise ordering us to vote Democrat. The presence of Walz means we can somehow accept the defeat of Cori Bush by a vicious Welsey Bell carting wheelbarrows of AIPAC cash.

Worrisome in a different way is how labeling the right as weird warps our sense of the possible. This is something taken up in an editorial for an earlier issue of Locust Review, written in the wake of the events of January 6th, 2021. As we wrote then, the Capitol riot/attempted putsch/whatever you wish to call it was “a fight between two normals, the normal of a recent status quo and a ‘new,’ insurgent normal.” If the right wing is hung up on normality as identity, then much of establishment liberalism seems preoccupied with normality as performance. It’s made of the same haughty and puritanical disavowal, and isn’t even pointed in too different a direction.

Recall the way in which liberal commentary pointed to the hunting gear and trucker hats among so many of the rioters, an implication that it was the vague-but-menacing “white working class” to blame. That an outsized proportion of them were in fact, from the middle and upper stratas of society – cops, small company owners, managerial types – was obscured. The message was clear, though: the outlandish buffalo horns were of a species with the camouflage jackets and Nazi garb. Transgression, evidently, comes in many styles, but only one substance.

The mistake, made once again here, is that by conflating all of the above, it narrows the field of acceptable engagement with the spheres of politics, culture, and life. To look beyond this narrow scope is the real problem, not its narrowness. As if such a wide and equitable range of existence is possible within it. As if the darker transgressions would have emerged in the first place if this were true.

There is, of course, another side to the weird, the embrace of the unknown in the name of liberation and human fulfillment. It has driven much of what is still rightly looked at as a leap forward in one sense or another – social, political, aesthetic.

“Modernist and experimental work often as weird when we first encounter it,” writes Fisher. “The sense of wrongness associated with the weird – the conviction that this does not belong – is often the sign that we are in the presence of the new. The weird here is a signal that the concepts and frameworks which we have previously employed are now obsolete.”

Pulling back the focus, it is obvious how desperately we need a new framework. Sure, sometimes an offhand turn of phrase is just an offhand turn of phrase. Other times it’s another link in the chain of the spectacle separating us from a history crying out for a change in course. Whatever breaks this spectacle, it will at first come across as deeply, unabashedly weird. We have yet to encounter it, and it’s probably not going to be waiting for us in the voting booth in November.

Header image is James Guy’s On the Waterfront (1937).

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

August 3, 2024

Wrong

Why do I bother? What is it about this activity called writing that I seem to enjoy despite every reason not to? How, even when I am at my most depressingly convinced that absolutely nobody will read what I put out into the world, do I keep returning to the keyboard, compelled to hammer away at it until something resembling coherent ideas come together?

I don’t ask this out of self-indulgence. Like most of us, I’m aware that today we write more but say less than ever before, that the bumbling homunculus of “misinformation” emerges from this reality. Words, and the ideas that represent them, like everything else, are overproduced, and thus more disposable than any prior time. I know this. And yet something in me cannot help but contribute to the pollution.

Part of it is surely a compulsion, a way of coping with a neurosis so widespread it’s become mundane. When we comment or post or write in the online mall that has replaced nearly every public forum, we are all scratching that itch. The social industry is designed with this in mind. The only thing that separates me and others who try to “professionalize” their output, to arrange their compulsion in the forms of articles or what we might have once called blog posts, is that we are trying, probably in vain, to organize.

And what exactly are we organizing? Our thoughts? Sure, but more than this. To compose something that attempts to be (likely) longer, with more of an arc and argument behind it; this is to push against the cacophonous tide of knowing. The race to come up with the exact and correct and best thing written at the moment, to best all other comers with the snazziest zing: these flatten life into a series of one-ups where anyone who manages to claw their way up the first rung is only bound to be snatched back down to the bottom.

Of all the tools employed by this doomed band of scribes, the strongest and most ubiquitous, the most essential, is negativity. The practice of summing up an event in 240 characters or a picture of your face accompanied by a bit of text your brain vomited up is designed not only to disregard nuance and contingency, but to insist that their existence is heresy. What is can only be what is. Which means that what isn’t is more dangerous than perhaps anything else. The unexpected ways an event's moving parts can shift, the void they leave behind, these consume us if we do not account for them, even (and especially) if we can do nothing to change them.

We know what this kind of worldview – the preoccupation with what is and therefore can only be – looks like. It is often cynical and bloody-minded. But it also relies on an unexpected disposition. That is the disposition of optimism. Optimism isn’t just a bland belief that the good will always prevail. It’s the belief that what is must be easily explained, therefore easily controlled, and therefore, that the good will prevail, whatever the “good” may be. It is an impulse shared in common by conspiracy theorists, the most wooden adherents of Enlightenment thinking, the liberal appeal to the best of “the American tradition,” and yes, much of the left (particularly its terminally online sectors). All are prone to explain away the inexplicable – the “not good” – with a tribal accusation of apostasy. It’s not just disagreement this worldview cannot brook, but even the practice of questions.

Again, we have all seen the outcome. Yes, the unknown will consume us at some point, but not before we consume each other. Optimism, like the written word, is cheap. Easily disproved. But in this world of planned obsolescence, the cheaper something is, the fiercer we cling to it.

When the optimist’s plan of action fails, more often than not it means they are rendered immobile, frozen in place, unable to admit they did something incorrectly. Aware they cannot proceed as they did before, but stuck in stubborn refusal to embrace the pessimism their situation clearly requires, they smilingly retreat. It is one of the reasons why so many who seek the change the world, in whatever fashion, end up doing little more than posting and tweeting, even as we watch social media lose what little purpose it had to begin with.

Pessimism, however, is the gift that keeps on giving. It’s not merely that lower expectations means never being disappointed (though that is perennially true). There is a humility that accompanies pessimism. An admission that one doesn’t know exactly what to do at all times, and therefore the patience to assess and see what, if anything, there actually is to be done. When something works, it isn’t simply a chance to puff out our chests. It is a revelation. If toxic optimism sneers at disagreement, true negativity yearns to be wrong.

July 19, 2024

Mimic Elegy

The call for submissions to the twelfth issue of Locust Review, “The Call Is Coming From Inside the House,” is now live. If you have a story, poem, work of art, essay, or review you think might fit the theme, then we want to read it.

Spend enough time in Appalachia and you can understand why its folklore is so unsettling. This is one of the most ecologically diverse regions on Earth, but also one of the most sparsely populated and geographically remote in the continental United States. Rolling mountains, deep valleys, thick woods that practically beg you to get lost in them. Few other dominions are more likely to host something simultaneously undiscovered and dangerous.

It is also, for not entirely unrelated reasons, one of the most historically rich parts of the country. They say many of the earliest European settlers found their way to Appalachia so they could live on their own terms, a tip of the hat to the strong Scots-Irish lineages in the region. Whether it's true or not, the long history of displacement, land grabs, ecological destruction, violent labor struggles, and yes, racial unrest, belie this wish. Considering how many “outsiders” tended to be people looking to do you harm – men from the mines or railroads, thugs and scabs kicking you out of your home – a healthy reticence is understandable. Deep down in the soil, hanging in the still air of this beautiful and unforgiving landscape, there are countless stories eager to take on their own life. That some take a supernatural form — ghosts, witchcraft, countless cryptids from the dwayyo to the snallygaster — is no surprise.

One of these is the mimic. You've likely heard of the mimic of Appalachia, or at least of the stories that continue up through Appalachians today. This is an entity — calling it a "creature" would be too precise — capable of calling to you in a familiar voice. Most often it is the voice of a friend or loved one, but it can also be your own. Its aim, so the tales go, is to either confuse you or trick you into coming near. What happens after that is a matter for the imagination’s darker corners. The most common advice is to calmly walk out of the area.

Some say the mimic is actually a raven, a magpie, or some other bird capable of copying what it hears. Others say that the voices of the mimic come from the infamous wendigo. In the end, none of us can say what a mimic looks like.

Or can we? If one of the primary characteristics of a mimic is its ability to avoid being sighted, why wouldn't it be able to hide in plain sight, keeping its powers and abilities hidden from onlookers? Why, when it isn't luring unsuspecting hikers to a possibly grisly end, wouldn't it be able to carry on an erstwhile normal life? Why wouldn't it be able to run for the office of Vice President?

J.D. Vance likely knows the stories of the mimic. So much of his political identity is bound up with Appalachia, and that has been deliberate on his part. It’s been apparent since the release of his book Hillbilly Elegy. Even after being repeatedly criticized and pilloried over the last decade — including many of Vance’s fellow hillbillies — not to mention a truly execrable film adaptation, this book which should have gone the dodo’s way of A Million Little Pieces is still seen by many as a legitimate treatise on what ails poor and rural America.

We can safely bet that Vance will be trotting out these embellished bona fides on the campaign trail over the next few months. Meaning that, much like Ohioans during his successful Senate run, we’ll be barraged with stories of his Mamaw and Papaw, his drug-addicted single mother, his dirt-poor upbringing, his time in the Marines, then Yale Law School and onto the world of venture capitalism. He will no doubt devote plenty of breath to describing in general terms the destitution that still hangs over the regions of his childhood — the poverty and deindustrialization, the persistent opioid crisis — and contrast it with his own biography.

He’ll then exhort voters to think of how every hillbilly deserves to take his path — and strangely, only his path — if only the globalists and woke elite would take the boot off their necks. The crowds will cheer. More to the point, they’ll be ready to commit their share of zealous, possibly violent acts to defend that vision. The thought of Curtis Yarvin, Rod Dreher, Peter Thiel, and other neoreactionary figures cited by Vance as an influence, put into practice from the bully pulpit.

There’s been ample space devoted elsewhere to pushing back against Vance’s vision of Appalachia. When you have a history that includes miners shooting cops and Pinkertons, an often steadfast respect for the surrounding nature, black and white and native and Melungeon living side-by-side, painting your own home as a racially homogenous, torpid backwater is going to be at best a fraction of the picture. Nonetheless, Vance’s descriptions chime with a certain view held by liberal and conservative alike: that of a community inherently narrow, instinctually conservative, largely white and, most importantly, completely inert.

Whether Vance believes every bit of his own bullshit is beside the point. Actions in recent years — most notably his journey from calling Donald Trump “America’s Hitler” to then sharing a presidential ticket with him — have shown him to be less than a man of his word. But among those who actually hold power, someone of Vance’s background who confirms their own views of the rural poor is tremendously valuable. There would be plenty of incentive for him to cling to them.

That is one of the primary takeaways from Gabriel Winant’s master class of an essay in n+1 on Vance, published not long after the latter took office as Ohio’s junior senator. As it turns out, Winant was at Yale around the same time as Vance, and the two met a handful of times. “I did not of course see in him the monstrous sociopath he turned out to be,” wrote Winant, “but even in our couple of passing encounters I could recognize him as a bullshitter, eager to ingratiate himself to wealthy liberals who couldn’t see his disingenuity.”

Winant also deftly points out that, however out-of-place Vance might have felt at Yale, he took it as something uniquely directed at him, rather than anything structural (much like his refusal to see anything truly structural in the conditions of rural America). Ironically then, his instinct wasn’t to rebel, let alone to try to change his own conditions, but to conform, to play the game by the rules of the privileged better than they ever could.

Vance naturally continues to speak to the struggles of his former homelands. He has to. It’s made easier by the fact that the rest of the establishment – including mainstream liberalism – has shrugged its shoulders at the industrial and natural disasters that devastate these regions. It took the Biden administration weeks to mount a meaningful response to the train derailment and chemical spill in East Palestine, Ohio. Vance dithered a bit too, but Biden’s vacillation was easier to contrast with and made Vance look genuinely concerned. Whether he ever planned to follow through on calls for better regulation or safety conditions is beside the point, particularly because he didn’t have to vote down late 2022’s railroad strike. His former stances blaming the poor for their own poverty should tell us everything we need to know about where Vance’s “populism” will revert to when confronted with any working class – Appalachian or otherwise – looking to live on their own terms.

Of course, there is never any escape from one’s roots, at least not permanently. For as much as Vance may have resented the life of the rich and powerful, he clearly wants it more. The price is to be haunted by what he left behind. Cynthia Cruz, in her book The Melancholia of Class, “The specter of what the middle class imagine as ‘working class’ is always with me. In a sense, this specter is my double, my working-class self, the ghost of who I left behind when I left my home town, now hidden behind a palimpsest of tropes the middle class invented... It is where I come from, who I am and who I will always be.”

Little wonder then that Vance has spent so much of his public career obsessed with where he came from. Not all carpetbaggers come from elsewhere, and native sons can get away with more destruction than most strangers. If he is going to be so inexorably lured back to Appalachia, then he is going to turn it into what he always wanted to be. To do that, though, he’ll have to speak like what he once was.

Few need convincing that ghosts, monsters, and the supernatural play a huge and significant role in the modern psyche. Allow the unexplained and unexplainable to take on fantastical form, and we can get a handle on it, even if we cannot control it. Even if we understand its awesome ineffability is equal parts wondrous and dangerous, that it is fully capable of swallowing us whole, and of speaking back to you in the timbre of someone you love.

That something like the mimic might exist isn’t just horrifying because it can speak like you. If it sounds like you, can it look like you? Might it even be able to be you? Could anyone, including you, tell the difference? Who, ultimately, in this moment of such predatory ambitions, is the mimic?

J.D. Vance doesn’t have to answer that question, to confront the existential crisis he portends. We are all bound to watch for the next few months as stumps and stamps his way through Appalachia (and the rest of the country), his drawl now exaggerated, unsure if he is codeswitching or simply reverting to the speech patterns of his youth the way we all do when we return home.

He’s there to save Appalachia. Or to contain it and fence it off from the rest of the world. Once he might have been able to tell you which. Now the certainty is gone. But the rewards are great, so sincerity matters less and less. Ostensibly, he is unconcerned with finding what he lost, but what he lost may yet find him.

On the way back to the campaign bus, he'll pass a nearby wood – don't call it a forest in Appalachia; those are the woods – and stop to gaze at the expanse of twisted green sprawling upward across the hills and mountains. At first he won't know why he stands frozen in place for so long, what might have possibly seized his attention in such a strange way, luring his sight and sound into these dark canopies.

Then he'll hear it. A voice, calling to him. One he recognizes as his own. And it will be the most terrifying sound he’s ever heard.

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

July 15, 2024

Blood in the Picture

Before I proceed to this version of internet-mandated doom, two bits of business:

First, “The Last Avant-Garde,” my review of Dominique Routhier’s solid book on the situationists and cybernetics, is published at the Los Angeles Review of Books.

I will be presenting my paper “In and Against the Dream Machine: Hollywood on Strike” at this November’s Historical Materialism conference in London, as part of a panel on performance and resistance in late-late capitalism. More details here…

American politics has been about image over substance for a long time. Quite possibly, it’s been that way from the beginning. Its present state can’t really be news to anyone. Donald Trump implicitly gets this, and it explains why he may be the most durable political figure in recent memory.

If there is an image that captures this election season, it is that of a defiant, bloodied Trump being ushered offstage by the Secret Service, the Stars and Stripes waving in the background next to his raised fist. You almost have to admire it; he knew exactly what to do in the situation. Of course he did. And the resulting photograph isn’t just the photo of the year, it may be the photo of the decade. I hope whoever snapped it is prepared to retire, because after it’s slapped across every magazine and newspaper in the world, they’ll have made a damned mint.

If a picture’s meaning is shaped by its context, then it is by definition bound to bring other images to mind. In this case, Trump’s resolve conjures cringey memes of a doddering Joe Biden struggling to string a sentence together. It will be what centrists and Democrats think of when they refrain from criticizing Trump lest it come off in “poor taste” (not that those on the right would extend the same courtesy). It will be what people think of when they go to the polls. They will have a simple formula rattling on their head: one of these men can get back up, can act with intent and purpose. It’s not the incumbent. It will be enough to turn them out in droves, sway many an ineffable swing voter, and demoralize even the most steadfast Biden supporter.

This is the logical outcome of politics as spectacle: eventually the issues matter in only passing fashion, secondary to the leader. In fact what matters isn’t even the leader himself but the idea of the leader. Stability, security, the viability of a meaningful future; insofar as these play any role whatsoever in this election cycle, they are embodied in a single person. Jameson famously argued that the postmodern rejection of metanarrative — and the aesthetic leveling that comes with it — stands in for very real power structures and hierarchies. It also provides cover for the de/reconstitutions necessary for power to maintain itself. The convergence between establishment neoliberalism and the far-right has been underway for some time, and has taken some worrying steps forward lately. The American version of this is taking place in a characteristically crude and literal way. Swathes of young people already see it, as it has been the liberals most enthusiastically cheering the vicious crackdown on protests in solidarity with Gaza. Now, with these same centrists essentially handing the moment over to a right that is better mobilized and thoroughly prepared to seize and reshape the mechanisms of power. What was once “unpresidential” becomes the new standard of good government. The new boss will always also be the old boss.

In this sense, it is acutely significant that there is blood streaking Trump’s face. Blood is a highly potent emotive in any political imaginary, but it has played a pointedly grotesque role in the mythos of fascism and the far-right, allowing them to cast themselves as both martyr and honorable guardian. Already you can see it in the outpourings specifically from the Christian right, their insertion of Trump into religious narratives, proof that “God wants Trump to be safe.”

Harrowing as it is, it also tells us something worth remembering: that while images are shaped by context, they also contextualize. Just as this one pulls other images to mind, so will it obscure others. Politicians are expressing more condolence for Trump than they have 40,000 dead Palestinians. The very reasonable insistence that a man who encourages violence should expect it to come back around will be drowned out by accusations of bloodthirst. The fact that the shooter was a registered Republican will be twisted into paranoid proof that the project to Make America Great Again is besieged by enemies on all sides. The urge among liberals and parts of the left to look for false flag conspiracy will simply add to political paralysis.

Whether there is any alternative to this in the immediate term is difficult to see. There can be no denying that the next several years will be very rough, and it may be some time before we can see a way out. Pictures don’t move history by themselves, but the fact that this one and the events that made it close the loop for Trump make it a very difficult one to get around. American politics as aesthetics is taking a massive leap forward. The blood will be chillingly real.

Header image is Hermann Nitsch’s Schüttbild (1983).

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

July 5, 2024

Democracy Eats Itself

1.

After fourteen years, Tory rule in the UK is gone. Good. they leave behind a destroyed country: social services gutted, wages stagnant, a National Health Service – once the pride of the British welfare state – on its knees. Not only are the Conservatives no longer in power, they were good and drubbed in the July 4th elections. Some say this is in effect the death of the Conservative Party, the oldest political party in the UK. They can’t be far off.

You’d be forgiven for missing the sighs of relief, muted as they are. This isn’t the replacement of a decrepit and inept right-wing political force by something more vibrant and principled, a party that is going to restore a future to young people and dignity to everyday life. No, the new force, the new ruler of British politics, is Keir Starmer’s Labour Party. When asked, Labour voters justified their choice at the polls not by saying they thought things would change, still less because they agreed with the party’s platform, and almost none because they believe Keir Starmer to be a principled and effective leader. The most stated reason was simply to get the Tories out.

Keir Starmer isn’t even a man, let alone a principled one. The best thing you can say about him is that he is a politician of his time: a wet, squelching sack of talking points arranged in the shape of a nice suit. And while that may make it difficult to look at him, still less to imagine him leading anything, it’s also enabled him to weather any challenge to the course of the Labour Party relatively unscathed.

Time after time, in public appearances on TV and radio, angry voters have savaged his indefensible policies. How do you, a human rights lawyer, defend the deliberate starvation of Gazans? How can you shrug at news of drowning refugees? How is it that you can call Labour a party of working people then scrap any policy that might make their lives easier? Starmer’s reaction is the same every time. His eyes widen (but only a little bit) he lets a jumble of words ooze out of his gob that seems to mold and dissolve what people say without every substantially refuting anything. It’s smarmy and untrustworthy, but remarkably effective.

Even when he’s bullying the embattled left wing of his own party, you can’t find anything of substance. It’s not just that there’s no truth to what he’s saying. There’s nothing of anything. No viciousness. No vitriol. And certainly no principle. Yes, he’s managed to completely kneecap the left of the Labour Party, but it’s been entirely through bureaucratic machination. What he says or does to justify those machinations is ultimately irrelevant. It happened. You have no say. Get used to it. With a massive majority in the Commons, Starmer’s Labour will bring this style to bear, but, oddly enough, it will always be directed against the very people he vowed to help.

This, of course, won’t hold. Even the humblest expectations can go in dangerous directions when they are deflected, and there are now far worse parties than the Tories wait in the wings. Nigel Farage’s Reform Party won thirteen seats. Farage no doubt clapped like a manic seal as Le Pen stormed the French elections, and his party’s showing is likely going to make him more emboldened and, frankly, more insufferable. He isn’t exactly the best political operator out there, but under these circumstances he doesn’t have to be. All he and the rest of the Reform MPs will have to do is wade through the ankle-high goo that drips from Starmer’s mouth in public appearances.

And to think: we could have had Jeremy Corbyn instead. At least he got to keep his seat. Good.

2.

Shift the focus to France. There was a common graffito on the walls of Paris during the 2017 elections: “Macron 2017 = Le Pen 2022.” It may have been off by a couple years, but, well, we got there. The horse-trading between the left-wing Nouveau Front Populaire and Macron’s centrist Ensemble bloc may deny Le Pen’s Rassemblement National an outright majority in the French parliament, but the margin will be slim. Meaning that the RN will still have room to pull the more conservative and/or opportunist among the center into its orbit. Fun fucking times.

It’s not an entirely dismal picture. The NFP was brought together on short notice, and it ran on a (mostly) principled program of opposing austerity and racism and withdrawing French support for the war on Gaza. That this program came in second reflects appetite for a different order.

Whether this can translate to a meaningful opposition is something else entirely. The NFP’s right wing – led by the Parti Socialiste – has operated like most social democratic parties under neoliberalism. Meaning they have spent more time administering austerity and defending racism than they have opposing it for the past three decades. The best thing that can be said for the PS is that it hasn’t managed to win more than a handful of seats in the past several years.

Still, the NFP knew it needed the PS, and vice versa. Pity the PS haven’t been acting like it. Memories of successfully ratfucking the NFP’s predecessor NUPES must have been dancing in their heads this whole time, because they’ve spent a good chunk of this campaign talking about how they refuse to let anyone to their left lead them in parliament. That La France Insoumise have shamefully accommodated these maneuvers only means they will be in a further compromised position to put up a fight to the RN’s agenda.

If the center-left is unafraid of courting the void like this, then we shouldn’t lose focus of whose fault all of this really is: Emmanuel shitting Macron. This is a man who, after the RN dominated the European elections, decided to call elections at home. It was a decision that just about everyone saw for what it was: suicide, and not just for him and his party. The RN, with its undiluted scapegoating of Muslims and immigrants and queers, its hostility to anything smacking of workers’ self-determination, was scratching at Macron’s front door. Rather than fortify the barricades, he swung it wide open and let them vomit out his window onto the folks below.

True to form, Macron spent as much time in previous weeks targeting the left as he did the far-right. This election was about defeating “competing extremes” he said. Now that Ensemble has been kicked down into third place — a full seven points behind the NFP — he is equivocating and hedging bets. The NFP had always said that it would order its third-place and below candidates to step down in the second round of the elections and urge its voters to support the center in order to stop the far-right. They’ve now done so. And while several Ensemble candidates have done the same, many other third-place Ensemble candidates have so far refused to issue such a clear order. Why be principled when being blind to history is so much easier?

3.

Remember last week when everyone was wondering who was going to replace Joe Biden? Primarily, it was a moment of severe uncertainty and frustration, but folded in there was that little spark of hope, that maybe the 2024 American elections wouldn’t be quite the dismal plod into the cesspool we thought it would be.

That spark is gone. Biden is sticking around, debate-time sundowning be damned. Whether he truly believes he can beat Donald Trump is irrelevant. Not just because his metric for such things is utterly and hopelessly broken, but because there is no real mechanism to get him to bow out. For the past several months, Democrats have shrieked in the ears of the left, youth, people of color, and just about anyone who shared the slightest shred of doubt: all that was needed to defeat Trump’s blustering lies and disregard for democracy was for Biden to stand next to him and show the world how upright and morally righteous he was. Hard to do that when you can’t put together a sentence.

Biden’s incoherence isn’t simply a matter of age. Yes, he’s 81 years old, but he’s been a mean old man for at least forty of those. He has spent most of his political life as a spiteful, prevaricating emissary of some of the worst people produced by American capitalism. With all the moral and intellectual contradiction he’s had to navigate, all the cruel and nonsensical justifications he’s had to trot out over the years, it’s no wonder that his brains are scrambled eggs.

A hack writer would say that Biden’s advanced state of decay is a stand-in for American democracy. It’s true but unoriginal. It also doesn’t fully capture the stakes. Not so long ago, pundits in Europe, Latin America, Canada, the UK, and beyond spoke nebulously but ominously about the “Americanization” of their own political process. This was roughly around the same time as Tariq Ali and others on the left started describing what they called “the extreme center,” and the two concepts overlap enough for them to be usefully compared. In some ways, you might call “Americanization” the cultural imperialist logic of the radical center.

The basics go like this. The financial crisis of 2008 burst the bubble of neoliberalism. Rather than prompting a genuine reassessment of the choices that brought the global economy to its knees – privatization, deregulation, shredding the social safety net, and anything else that might have made ordinary people’s lives more stable and safe – the response was to simply entrench them. All the structures and institutions that had progressively removed economic decision-making from any kind of democratic say dug their heels in and kept doing what they had always done. Those structures and political formations that had always presented themselves as pragmatic and realistic had to finally reveal themselves as ruthless and venal.

The results were disastrous of course. But for it to work, for the marketization of anything and everything to be taken as a natural given, then official politics had to accelerate in the direction we had already seen it drift. Weaponized identities and endless culture wars had to take the place of actual policy discussions. Vision for the future was a frivolous indulgence next to protecting your own. Alternative voices weren’t to be opposed on anything like a reasonable basis, but painted as dangerous outsiders looking to dissolve the fabric of everything you hold dear. Up is down. Black is white. Nothing means anything. And at the center of it, the same machinations of domination and exploitation just keep chugging along.

Many Americans will read this and scratch their heads. For many of us, this is how American politics has always operated. Which is why these nattering heads abroad were framing it as Americanization in the first place. The reason we hear less of it today is that, to a great degree, the process of Americanization has been completed. Of course Starmer will work with Trump if he’s elected. Trump is impossible without people like him, and now the reverse is true. It’s not difficult to imagine Starmer, with his gooey bile spilling from his mouth, coming fully apart next to a smirking, lie-spewing Farage. That Macron has been spared this fate may simply wind up one of history’s cruel mercies.

4.

It was always going to end this way. Americans love to think of democracy as something uniquely theirs. Frankly, the only thing American about American democracy is how brittle it is, how vulnerable its vanity and self-regard renders it. Like all entities with such an aggressive ego, it is eggshell fragile.

This is a model of government that has never actually believed its own promises. But somewhere down the line enough people started to believe in it that it became too late to stop the charade.

Read this…

Democracy has never been and never can be so durable as Aristocracy or Monarchy. But while it lasts it is more bloody than either… Remember Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes exhausts and murders itself. There never was a Democracy Yet, that did not commit suicide. It is in vain to Say that Democracy is less vain, less proud, less selfish, less ambitious or less avaricious than Aristocracy or Monarchy. It is not true in Fact and no where appears in history.

That quote comes from John Adams. Yes, that John Adams. A prime architect of American democracy who saw the practice as essentially another form of mob rule, a sure path to bring down any society from the inside out. No wonder its standards and practices are so weak. There have been very few attempts to overhaul and revamp it. The last major one was Reconstruction, and it had to be dismantled by the Klan.

This, in other words, is the model that we exported to the rest of the world. That it has been some time since any significant section of the globe actually thought of America as any kind of beacon is beside the point. Particularly since there hasn’t been any other model on offer. Sure, most people abroad who still defend America’s most American characteristics tend to be the most obnoxious, braying, inhumane ogres you can imagine. But, much as we may hate to admit it, they are the ones with the wind of events at their backs.

Here’s the part in most articles like this where we talk about the need to resist. But resist how? It’s one of the problems and challenges inherent in this moment, when anything earnest, anything that tries to cobble together a vision for a future worth living, smacks of lame centrist pabulum, kente cloths worn by congresspeople taking a knee in the US Capitol right before the vote to increase police budgets. These are the people who have affixed a hashtag to resistance and rendered it meaningless. They are the flotsam of Adams’ letter. They are also being exported.

The chances of reinjecting some actual meaning into the concept of resistance are by no means high. It will take a lot of experimenting, trial and error. The increasingly likely scenario, though, is that all of us are just waiting for our own Biden moment: staring into the camera, shocked that we still exist, waiting for the coming implosion.

Header photo is from Ravenous (1999).

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

July 1, 2024

Programmed Just to Do

Kraftwerk.

Kraftwerk.There is an open question at the heart of Kraftwerk’s music. It is alternately obvious and maddening for anyone familiar with the group, or with electronic music in general. Consider their origins in Dusseldorf, hub of Germany’s auto and telecommunications industries. Now consider their deliberate, at the time unconventional choice to embrace the synthesizer and electronic drum machine, to manipulate the sounds of “traditional” instruments and even the human voice through vocoders and other machinic filters. What, Kraftwerk seemed to ask, is the nature of the relationship between human and machine, particularly as we are increasingly reliant on them?

If that question seems mundane by today’s standards, that may be because attempts to answer it have been repeatedly frustrated. Few need reminding of just how hopelessly intertwined our neuroses are with our phones, our social media profiles, and the algorithms that increasingly condition everything from our job options to our dating prospects. It’s easily forgotten that this is only the latest iteration of an entanglement between people and technology.

You could argue that Kraftwerk anticipated this tension, but it’s both more prosaic and insightful than that. It wasn’t precognition that spurred them to release albums like Computer World or Electric Cafe during the height of the personal computer boom. Nor was it mere serendipity for them to experiment with the sounds of Chicago house and Detroit techno (they had, after all, been a direct inspiration for the rise of electronic dance music). It was an honesty about changes already underway: noting the contradictions and oversights inevitable in technological innovation, and exploring – not predicting – what might come of our lives and ideas as a result. That the group’s members have remained resolutely ambivalent in what they think as human beings about this dialectic — rarely granting interviews, even going so far as to render themselves an extension of the electronics in their performances — has only made their engagement more interesting, more influential, more fecund with possibility.

That is, in short, what I was hoping for during Kraftwerk’s residency at LA’s Walt Disney Concert Hall. The announcement of the residency commingled with headlines about artificial intelligence – evenly divided between an near-evangelical enthusiasm and sincere dread about what AI might do to people’s ability to earn a living – made an interpretation like Kraftwerk’s seem particularly timely.

It was this same matter of timing that influenced my choice of which night to attend. Kraftwerk had designed their nine-night residency at Disney Concert Hall with each night intended to showcase the work of one of their albums. Given all of the above, the most apt choice was and could only be 1978’s The Man-Machine.

Still, it would be wrong to characterize the instinct to rush into the Walt Disney Concert Hall as motivated only by sheer joy and excitement. There was, admittedly, a bit of morbid curiosity at play. The Disney Concert Hall is typical of most postmodern performance venues. Designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003, it sits in the center of Downtown LA with all the pomp of a place pretending it isn’t surrounded by some of the most desperate social decay imaginable. Its swooping silver facade is indifferent to the surrounding encampments of unhoused Angelenos. The heat and light generated by the mirrored stainless steel have been known to warm nearby apartments so badly that air conditioners blow fuses. Passing motorists have been blinded by the glare, causing occasional traffic accidents.

Jon B. Lovelace Collection of California Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America Project, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Jon B. Lovelace Collection of California Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America Project, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.In other words, this is a building oblivious to events unfolding around it. The prospect of a Kraftwerk performance in such a space raised the possibility of their insights being dulled. It brought to mind what Nick Cardew wrote about watching their July 2023 performance in the Spanish city of Sitges: “The criticism frequently voiced of Kraftwerk in 2023 is that under the direction of Ralf Hütter - the only original member still in the band - they have become a parody of their former, progressive selves, a touring dinosaur content to pump out the old hits for anyone who’s paying them.”

Keep in mind, this is a show that Cardew ranked on the whole as a positive experience. His hope was that Kraftwerk would transcend the fate of so many bands who have been around as long as they have: becoming their own tribute act, shunning relevancy in favor of a comfortable pedestal.

Kraftwerk falling into this trap would hardly make them unique. The passage of time isn’t their fault. Nor is it the way in which all the glitz and self-importance of the culture industry seems to have trapped culture at large in a cul-de-sac. That they would fall victim, when their sound and catalog seemed to refute it for so long, would simply hit home the frustrating irony. Mark Fisher’s observation in Ghosts of My Life that Kraftwerk still sounds like the future, “even though this is now as antique as Glenn Miller’s big band jazz was when the German group began experimenting with synthesizers in the early 1970s” is as depressing as when Fisher wrote it in 2014.

None of this is to say that the experience was without any wonder. It was impishly entertaining watching so many aging scenesters invade the pomp of the Disney Concert Hall. Ushers more used to seeing clientele in more formal dress greeted us with a delightful mixture of amusement and confusion as they guided ripped skinny jeans and Cocteau Twins t-shirts to our seats.

Whatever might be unnecessary about the outside of the Disney Concert Hall, its inside acoustics served the sound of Kraftwerk’s music – its thumps and beats, its synthesized notes skipping and punctuating their way through their songs – quite well. Listening to a group like Kraftwerk on headphones or on your computer can, even with full knowledge of what the music accomplishes, often leave one wanting, the dimensionality of their music flattened. That wasn’t the case at this performance which allowed the audience to fully experience the scope of the constructed sound and space and to feel the gaps between the beats and notes.

The same can be said visually. Kraftwerk’s performances are legendarily accompanied by computer animations that both capture and accentuate their songs’ subjects and themes. A concert hall of this size naturally allowed for a massive screen.

All of which is to say that, in terms of reading and interpretation, Kraftwerk’s performance was vivid. Meaning and intent were unmistakable without being overstated. The wonderful, terrible dichotomies of human life in a mechanized world were abundant and apparent. So were all of the contradictions of temporality that make Kraftwerk nostalgic and futuristic all at the same time.

The wonder of how modern travel collapses space into time is on display in the jaunty bounce of “Autobahn,” with its retro computer animations of automobiles gliding down Germany’s iconic highway. Conversely, there is an unmistakable coldness in the sounds and animations of “Trans-Europe Express.” There’s a certain irony here, given that the latter was the centerpiece of an album which Kraftwerk composed in order to shed their more explicitly German associations, partly solidified by the album Autobahn. Meanwhile, the clipped muscularity of “Tour de France,” accompanied by footage of that famed cycling event, turns the toned and trained cyclist into the nexus of this ambiguity, the slip between human and automaton.

Naturally, songs from The Man-Machine anchored this shifting, ambiguous dynamic throughout the night. No surprise there; it’s what we came to hear. And if these are themes that run through Kraftwerk’s entire catalog, then this album seems to distill them down to their most elemental. There is something very unsettling in “The Robots,” in the films of dancing Kraftwerk mannequins that have come to accompany performances of the song (“We are programmed just to do / Anything you want us to / We are the robots / We are the robots”). The steely melancholy of “Metropolis” inevitably brings to mind Fritz Lang’s iconic film of the same name, with all its themes of robotic replacement.

By contrast, the concept of “Spacelab” is fun, and even transcendent. Its gliding harmonies and floating percussion reflect a view of space exploration that is decidedly utopian and exceedingly rare. “Neon Lights” can sound downright elegiac, both songs reiterating the undeniable promise and pleasure that can exist in the relationship between human and machine. Meanwhile, the story of “The Model” explores the blurred lines between good and bad, making uncomfortably clear how easy it is to mistake manufactured desire for the real thing.

If there was any moment that shed this ambiguity, a song that came across as less like dangerous play and more like an explicit warning, it was in the form of one of Kraftwerk’s best-known songs, though not from The Man-Machine. The group has been playing an updated version of the title track from 1974’s Radioactivity for some time now, one that adds explicit mention of Chernobyl, Fukushima, and the nuclear accidents at Windscale and Three Mile Island.

There is little room for mistake here. Like most of us, the members of Kraftwerk have been jarred by the disasters of leaping into the future without looking first. It was a chilling performance, and a moving one, difficult to watch without feeling like we were being stalked by something hostile not just to humans but life itself.

And yet, inevitably, there was an unavoidable limit surrounding it all, a straightjacket around these songs that are ideally supposed to prompt exploration. One can’t help but be reminded of the debates that have always surrounded technology, now amplified and polarized with AI. Are these algorithms and learning machines springing up around us and building our lives more predictive or coercive? Or is it a bit more insidious than that? What is the difference between predicting and simply manipulating our behaviors?

“I want to dance,” my partner said to me. Though not particularly familiar with Kraftwerk, she’s been to her share of raves. “The music and visuals are incredible but I’m just kind of sitting here.”

She had a point. The thumping and hypnotic beats, the curving-sloping melodies, punctuated by the reworked noise of industry; if arranged perfectly, these prompt you to move in instinctive ways. It’s not dancing exactly, nothing so choreographed. Whether we are talking about London drum & bass or Brooklyn IDM or Detroit techno, there is a specific-but-ambiguous relationship between sound and movement. Are you being moved by it? Are you making the decision to move along with it? Does it matter? Without the space to explore these questions, time and context are muddled. Meaning and consequence miss each other.

It’s even evident in the pictures you’ve seen of this same performance. Being unable to move, all of them were necessarily from the same angle. The visuals of a Kraftwerk performance are stunning, but being forced to watch them from only one vantage renders them inert. There was nothing to be done about that. Our assigned seats had been assigned, and neither of us – nor anyone else in the audience – thought that moving from these assignments would be welcomed by concert hall staff.

So we sat. After being advertised this show by an algorithm constantly studying our needs, after purchasing tickets that will only ever physically exist on our smartphones, after obediently making our way to the precise seat allotted us by the ticketing system, we sat exactly where we needed to be. Or at least where someone needed us to be. So did everyone else. Maybe the grand question at the heart of Kraftwerk has been answered after all, and by forces well beyond their control. If so, then it’s a very dismal answer indeed.

All photos by the author unless otherwise noted.

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

June 28, 2024

In Dark Times, a Song

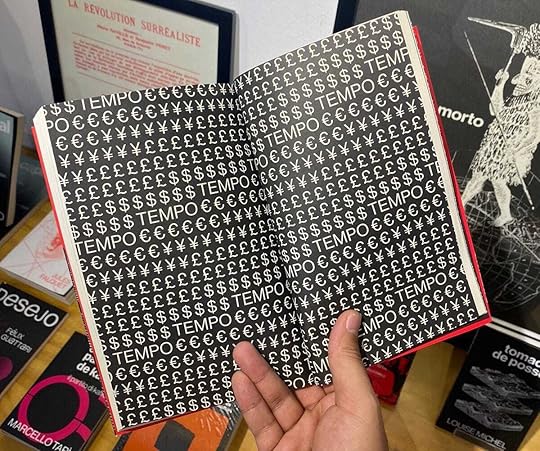

The Portuguese translation of Shake the City is released by Brazilian publisher Sobinfluencia Edições this coming week. Below is the preface I wrote for this edition.

A writer naturally hopes that their words reach a global audience, but anyone who expects it is being foolish. Even those with massive publishing deals can often struggle to get their books translated, and most books are never read in any language other than the one in which it was originally written. Perhaps a more equitable arts and culture industry would provide more opportunities for writers to get their books in front of new eyes and minds, for their ideas to be part of a robust and ever-deepening global cultural-intellectual commons. But that simply isn’t the world we live in.

When I received word that Sobinfluencia wanted to translate Shake the City into Portuguese, it of course came as a wonderful surprise. First, it meant that the book had already reached readers beyond my reasonable expectations. Second, it meant that they were at least as thrilled by its ideas as I was, that they believed others would engage with them too.

The comrades at Sobinfluencia have shown impressive sensitivity toward the original text and its translation. The arcs and arguments of this book are now translated into Portuguese, now available to the people of Brazil, with their own rich and remarkable lineages of class struggle and musical explosions. It leaves me humbled, grateful, and immensely proud.

In light of this, I wish I could write of more hope in this preface. Unfortunately, the devastated landscape I wrote of in the original English edition still looms in front of us. Governments – most notably in Europe, but around the world too – continue to swing in the direction of authoritarianism. Most nations are content to dither and waffle over the evident destruction of climate change. None seriously countenance the idea of a just ecological-industrial transition.

Pay enough attention walking through city streets, and you can see the evidence of post-pandemic shellshock on your neighbors’ faces. People are slower to believe in a way out, quicker to mistrust and fear. The atomization of daily life by big tech, the attenuation of what little remains of collective labor by the ubiquitous algorithm; these are accelerated by the introduction of artificial intelligence. Many vocations and occupations long since subject to proletarianization (including my own) will be further destabilized, their practitioners further immiserated. Which is to say nothing of ideas and aesthetics that will be further homogenized. Artists, writers, and music makers will find it increasingly difficult to make a living; those who can will face greater pressure to conform to arbitrary definitions of marketability.

And now, a fresher hell: the wholesale destruction of Gaza, renewed mass slaughter and displacement of the Palestinian people. Real estate developers openly promote plans to turn whole sectors of Gaza into cookie-cutter luxury apartments and beach resorts. Their transformation of built history into smooth space is mirrored in the push to remove Palestinian artists from streaming services, to ban them from concerts and music festivals around the world. Moments and temporal spaces that might disrupt colonial entitlement are wiped from the public sphere. For too many governments and institutions, the only sound that should accompany genocide is silence.

Even the sections of this book I would revise seem to further bear out a bleak forecast. At the time Shake the City went to press, I was certain that the choice faced by Gabriel Boric’s left-wing government in Chile was similar to that of Salvador Allende fifty years ago. That is to say it was a choice between mobilizing the masses and bending the levers of the state toward its fundamental transformation on one hand, or being drowned in blood by the forces of reaction at home and abroad on the other.

As it looks now, this was a perversely optimistic assessment. Boric in power has proven a pale shadow of Boric on the campaign trail, bolstered as he was by the estallido social and its flourish of popular power. It is a tragically familiar story, already played out in the cases of Syriza in Greece and many others. The parliamentary road to socialism remains riven with pitfalls, not all of them so dramatic as the events of 1973.

What does this mean for the arts? What does it mean for the popular creativity that was unleashed during the height of the estallido, the mass musical expressions that took over city streets and squares? In some ways, it bears out much of what Shake the City argues in the negative. If music needs space and time to reach beyond the confines imposed upon it by contemporary capital, then the setbacks and disorientations of the movements that created them cause these spaces and times to atrophy, shrinking rapidly and pushed to the margins of society, often vanishing entirely overnight.

The artists’ mutual aid organizations and networks of working musicians that allowed the Plaza Bernardo Leighton to be flooded with hundreds performing “El Pueblo Unido…” still exist. Their next steps a matter of debate, and it is difficult to imagine them scaling up on the events of 2019 anytime soon. Just as it is difficult to imagine the fascist Modi swept from power in India, an end to the apartheid regime of Israel, or an end to the order that impoverishes us with sky-high rents and shatters social bonds in London and Los Angeles.

We must imagine, though. We don’t have a choice. Some say pessimism smothers hope. Personally, I think hope is toothless unless we understand it as a finite resource, unless we stare down the reality that makes it feel impossible. In this regard, arts and music remain materially and psychologically essential, particularly when pulled away from privatized spheres, made and experienced in an organic, collective way.

It can sound more fanciful than strategic, and many of the ideas attempting to support it are just that, provoking scoffs and eyerolls rather than inspiring rationed hope. Past all the pernicious New Age bullshit, however, is the undeniable fact. Study after study, in fields ranging from musicology to mental health to urban planning, find that group participation in making and performing music nurtures thoughts and feelings of possibility, of self-determination and autonomy. The challenge is not to ignore these instances, still less to designate them with a condescending label of “interesting” before disregarding them entirely. Rather, we must look for opportunities to grow and expand these moments, while also avoiding their capture by institutions that would make them safe for consumption and mass subjugation.

We are headed into dark times. Quite often, singing will be all we can muster. It is the raw material of utopia. We cannot afford to ignore it.

That Ellipsis... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

May 31, 2024

The End of the World is Canon

Why do we need another show about the end of the world? Probably for the same reason we've gotten another show based on a previous intellectual property. Streaming has tanked; nobody can figure out how to make any money from it. But because every studio went all in on the model, they are left with no choice but to keep producing for streaming. Every executive is looking for a sure thing, but not even the sure thing can turn a solid profit. All that's left is to keep doing what we've always been doing, hoping that eventually some scraps will be left when the implosion of everything finally stops.

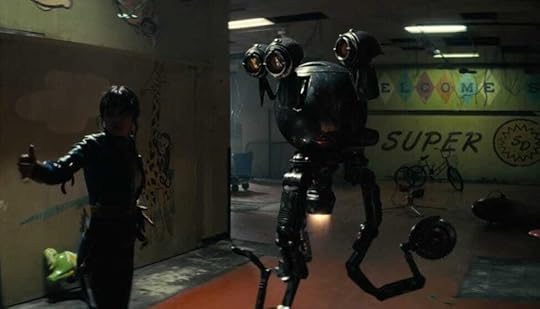

Hence Fallout. Amazon Prime shocked absolutely nobody when they announced they were greenlighting an adaptation of one of the most successful video games of all time. Every good decision made in wake of that was conditioned by that decision. And to be fair, most of the choices production has made are very smart. The writing is an incisive balance of dark comedy and tragic pathos, the dialog and story both deftly pivot with enough ease that we never lose sight of the horror of nuclear apocalypse anymore than we do its gallows humor. Likewise, the mysteries at the story's heart — How did the world end? Who or what is preventing it from being rebuilt — unfold with a rhythm straight out of a screenwriting textbook: unremarkable, but nonetheless effective.

The cast is excellent. None of us really know how a human being born and raised in an underground bunker would act after being thrust into a surface wasteland — particularly if said bunker was designed to be a stereotype of a 1950's American suburb — but Ella Purnell's Lucy MacLean seems a believable approximation. Kyle MacLachlan is clearly having a lot of fun with the direction of his career since the Millennials discovered Twin Peaks, and his portrayal of Lucy's father Hank is no exception. There's no doubt, however, that the one stealing the show is Walton Goggins. His rendition of a disillusioned western film star, now mutated into a basically immortal ghoul doomed to roam the wastelands in a sick imitation of what he once was, is everything we should hope it to be. Grizzled, cynically funny, a parody of himself that still somehow manages to drag along a megaton of gravitas.

So yes, Fallout is an enjoyable watch, and plenty intelligent to boot. Just about the only ones who seem to disagree are the hardest core of the video game's fans, which once again shocks absolutely nobody. Their reasons are as predictable as they are tedious, a repeat of the online whingeing that follows whenever any intellectual property crosses the boundaries of medium. The show isn't canon, they say, as if every cultural artifact doesn't change and evolve over time regardless of its specific afterlives. As if the specific posture of the game itself hasn't already changed by simple dint of it being publicly engaged.

It is ironic that devotees of a game that helped introduce the concept of “open world” believe that same world should be closed off, even from the social fissures that run through its own story. The idea of an America technologically dominant but culturally stuck is a fecund one. What would the year 2077 look like if the Cold War never ended, and if the leaps and bounds of consumer culture had continued to widen? How much more tragically stupid does American optimism — complete with its kneejerk anti-communism — look in the face of armageddon? What is the difference between preparing for the end of the world and profiting from it?

None of these questions are asked in anything like a subtle manner. “The future of all humanity comes down to one word,” says the insidious Vice President of the Vault-Tec Corporation. “Management.” We naturally hear the worst boss we've ever had talking to us. You know the one, the supervisor who wholeheartedly believes the mantras of every entrepreneur's seminar they've ever been to, even if they have no idea what half of them mean. The kind of person for whom genuine enthusiasm and petty tyranny are one and the same. Of course these are the people who will usher in the end of the world. Just look at all the money they’re looking to make in Gaza.