Alexander Billet's Blog, page 2

April 1, 2025

An Arrival at Pituffik

He had never seen anything quite like it. Through countless eons spent in an ancient wilderness, nothing like this. A white, jagged coastline tore through a tumultuous sea. On the horizon, rough, gray mountains pushed into the skyline.

Looking through the window of Air Force Two, he saw this odd floating landmass as a place where anything that wasn’t trying to consume was bound to be consumed. He could imagine lone strays – animal and human alike – sucked into the swirling snows, frozen and swallowed whole by the white void. This was a place that thrived on it. A place he understood.

And him? He wasn’t here to consume exactly. More to prepare the ground for a future feast. Possibly the most awesome he had ever taken part in.

Considering what was coming, he had to reflect on all he had achieved, and in such a short period of time. It was impressive enough that he had gotten this far without anyone discovering his true, inhuman form. But to have made it to possibly the second most powerful position on the planet (and with the “possibly” appended only because of the constant presence of that odd car man, who, he suspected, was likely another masquerading entity like him)? It was a magnificent ruse, proof that civilization was, ultimately, completely unable to outsmart deep time.

His ascent happened so fast that, truthfully, he still found it a bit awkward to refer to himself as a “he.” Let alone Vice President, let alone Senator, let alone best-selling author. Even after all this time, his emergence from wilderness, the years spent closely studying the movements of these strange beings. The military training, the time at Yale, the book tours, the media appearances, the campaign trails. It was “he” that he found most jarring.

“He…” “he…” “HE…” It was like scared laughter. It sent a tickle up his curled spine every time he heard it.

Nobody who had encountered him along the banks of what they called the Ohio River, whispering back at them in their voice from the woods, had ever called him “he.” Most of the time, they didn’t call him anything. They just froze, letting it dawn on them what they had just heard, and started walking again, picking up the pace – but never, never running – to put as much distance between them and him as they could.

At least, that’s what the locals did. The tourists, the visitors, those who didn’t know the woods were a place you survived? The ones who, occasionally, he even found whistling through the trees and hills? More often than not, they were his bounty. The trepidation and anxiety he provoked in the locals were enough to sustain him. But the reactions of the outsiders were truly a meal.

The confusion, the slow dawning fear, quickly turning to horror and panic, the adrenaline that wafted through the trees as they tried to run. He didn’t always need them to decay into the void of Appalachia. The kill wasn’t what drove him. Not by itself anyway.

It was the explosion of awe and extreme terror that took over the air when they finally saw his real face, before they rotted to dust in front of him – their eyes, fixed on him in utter disbelief, the last to dissolve into the void as it enveloped them.

The fear. The complete and all-consuming fear. That was what satisfied and nourished him. It gave him strength and allowed him to take new forms, eventually becoming strong enough to leave the woods after spending entire ages dwelling in the soil and stone and plant-life.

It allowed him to learn memory – though he found he could only apply it going back a few hundred thousand years at most. It also allowed him to form language, to become cunning and strategic. All the while, the hunger, the instinct to consume greater and greater terrors, grew in him. And as his hunger grew, so did the fear of those around him.

When his boss first told him that this place was in their sights, he was, admittedly, confused. Why here? Why this large mass of rock and ice, pushed by the cold winds toward the top of the world? He had been told all manner of things, all of which he had learned and practiced to repeat. “Geopolitically strategic.” “Necessary for national security.” “Protecting the world from Russia.” “Protecting the world from China.” And all the rest. He was good at repeating. Even if he didn’t really know what any of it meant. Repetition was, after all, how he had survived, how he had managed to get this far.

Still, he didn’t quite understand why here. Why Greenland? Then he learned. The deep histories of nomadic human people finding their way down the island through brutal winters and unforgiving seas. The legends and folklore. The violence that had torn through the lands. The Norse terrorizing the Inuit. The Inuit resisting. The arrival of the Danes. The years of extraction and exploitation and lives lived in the cold shadows of dashed hopes.

It all sent his hunger reeling, tearing through him. A land full of names and screams and cries he had not yet heard, had not yet learned to mimic? He had sensed similar despairs when he was in Iraq years before, and plenty of them, but he was far too removed, too inculpable to really feast. This was something new entirely, a meal beyond meals. Cities, towns and settlements full of people whose sense of dread and instability would provide him with new dimensions of wonder.

Thus the last-minute decision to join the human he called his wife on her trip to Greenland. The wife had been irked by his decision, and the subsequent news that she wouldn’t get to watch a dog sledding race after all. She knew better than to let her annoyance show, however, lest his feverish tastes be triggered, sapping her of what little will to live she still had left.

He needed to see it for himself, to breathe in the frozen air, to see if he could get a scent of anger and fear. To see if he could create the conditions to make a meal beyond the arbitrary borders he and his boss watched over. Why did his boss want Greenland? In the end, he still hadn’t a clue. But in the end, he didn’t care. He had his own reasons, his own bottomless hunger to satiate.

As the plane came to a stop on the runway, he realized he hadn’t yet decided what to say. Such absent-mindedness might tell him he was becoming something altogether more human, but it wasn’t that. At least he hoped it wasn’t. But in his years taking this form, he had learned that the best sounds to repeat were the most mundane. It was these that brought smiles to the faces of those around him while also spiking their deepest anxieties and frustrations. He hadn’t much time to conjure up something from the innumerable sounds that had imprinted on him through the millennia.

He and the wife disembarked. The base staff ushered them across the tarmac and he consciously stretched his adopted face into the rictus he had learned most people were able to look at. Their escorts – base staff, commanding officers – all rambled in his direction. He could make out tones and consonants, but he also knew that they could be tuned out without much in the way of consequence. He was too busy forming the things they called words in his head.

As they opened the door to the base’s interior, as he was greeted by the faces of soldiers and reporters alike, the sounds came to him. He knew these would be what they needed to hear. And so, with a learned twist of his jaw and the quivering anticipation of the feasts to come, he let himself speak.

“It’s cold as shit here.”

Perfect.

Daydreams & Paving Stones is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

March 26, 2025

An Unserious Nation

If you want to understand why it is that the American media is so up in arms over a Signal conversation, you first need to grasp just how insufferably nosy Americans have been trained to be. Many readers may yet be puzzled by the sudden laser focus of the US media and political classes on this of all instances given the context. The United States, after all, is cannibalizing itself. That the Vice President and a few bumbling cabinet members spoke of classified war plans over an insecure channel should be the least of our worries in the grand scheme.

It’s less worrying than the ongoing crusade to deport every Black or brown person with a crown tattoo or a Palestinian flag in their home. Less worrying than Elon Musk’s efforts to strip the US government for parts and gut what’s left of our threadbare social safety net. And certainly less worrying than the impunity with which the US bombs rain down on countries like Yemen, a truth that goes back well before the presidency was in Donald Trump’s syphilitic sights.

No, the real problem here is that the officials bombing Yemen were sloppy enough to talk about it over an app any drooling prole can download at the Apple Store. How common. How unpresidential. How unserious.

This, rather than any of the above, is what finally prompts the Democrats to pull the lead out, to stop helplessly flailing in front of reporters when asked why they aren’t doing anything. This is what it takes for Michael Bennet to start shouting in committee hearings, for the mummified Chuck Schumer to call for investigations. Never underestimate the jolts of motivation provided by a declining empire. It can still provide a few morsels of prestige and clout.

It would be an oversimplification to say that this empire was built by our nosiness, but by that same token it would be simply wrong to say it didn’t play a role. Go back to those longed-for days of the 1950s, when, so we are told, everyone had a comfortable house and two cars and enough scratch to buy a shiny new microwave for each of their 2.5 children and vacations to Disneyland every year. To this day it is only intermittently acknowledged that this was only possible because half the planet had been reduced to rubble, that the atomic future required the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. That the goods flowed partly because the west would kill to keep the Suez Canal open. Likewise, it wasn’t simply that the idyllic suburbs happened to exist at the same time as Jim Crow and immiserated ghettoes. Each persisted because of the other.

Still, it was the best of all possible systems. In theory at least. All of it was, naturally, highly individualistic. You, the individual, deserved this comfort. You deserved these manufactured goods almost as you deserved the manufactured desire for them. And so long as you played by the rules, you would receive them. If you didn’t receive, or didn’t receive enough, it was either because you didn’t play well enough or, more likely, someone less deserving got them instead. Someone who didn’t play by the rules as well as you did. The problem wasn’t that a few people had so much more, but that someone else with less might have what should be yours. Be on the lookout for them. They deserve retribution.

A whole cultural praxis sprung up around this in the 1950s. And with it, the paranoia and mistrust, the spirit of late capitalism, blossomed. The busybody neighbor – beamed into your living room every night as part of Leave It to Beaver or The Dick Van Dyke Show – was harmless enough at first blush. But then, these shows always focused on the well-behaved and deserving neighbors. It was those other neighbors, the ones who rumor has it voted for Henry Wallace in ‘48, who once signed a petition against the H-Bomb, who had to really be scrutinized, reported if necessary.

If there was anything as bad as those who didn’t deserve but got anyway, it was those who shared the abundance but didn’t want the system that created it. When the college kids hopped on a bus to register Black voters in the south, when Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland went around singing “Fuck the Army,” they were, by their very nature, ungrateful. No worse sin.

The tabloids and gossip rags and entertainment news shows that flourished in the wake of the 1970s were full of people who dared to have opinions and troubles outside the parameters of power and glamor. Politics was bound to adapt. Watergate might have been the last seriously reported political scandal in US history. After that, it was all downhill. News of arms traded to Iran to back anti-communist death squads in Nicaragua jockeyed alongside revelations that Gary Hart – one of the many mediocrities vying to beat George H.W. Bush to the White House – might have fucked someone who wasn’t his wife.

It is by now trite to point out that this has all come full circle. Kamala Harris thought calling Trump “an unserious man” was a real mic drop. What she missed, what the Democrats still cannot grasp, is that the unseriousness is partly the point. Yes, the nation that gave the world reality TV – a genre that allowed us all to sit in voyeuristic judgment of each other – finally has a reality TV star as its president. The role of social media in organizing the seething American ressentiment that put him there is, by now, well known. Given this, one of us can be surprised that Trump’s ilk have slipped up using the same apps that helped boost them into power. He’s so adept at sullying the sacred with the profane (in such a way that it leaves the former intact) that it’s probably second nature in his cabinet.

The counterattack from other Republicans is similarly predictable. The intrigue titillates even more than it did 70 years ago. The longer it can keep going, the more chatter there is to drown out anything of consequence. White House communications director Stephen Cheung says the Democrats are “weaponizing innocuous actions.” In a certain sense, he’s right. From what we can tell so far, the only issues discussed were the dispositions and capabilities of the military units that carried out the strikes. You could argue that the discussion put troops at risk, but in a world where America is so understandably hated, so does their very existence.

Also half-right is Ted Cruz, who has again said the quiet part out loud. “[I]f you look at the underlying substance of what they were discussing, I think we actually should be very encouraged,” he said. “Now the consequence is Americans, Texans, when you go to the grocery store, you're paying more… When you go to the department store, you're paying more because [of] this terrorism. What the entire text thread is about is President Trump directed his national security team take out the terrorists and open up the shipping lanes. That's terrific.”

About high prices solely coming from terrorism in the Suez Canal, Cruz is wrong. Insofar as the security of 70 years ago ever existed, it certainly doesn’t now, even if our own nosiness can now be used against us. That America will kill for low prices, he is most certainly correct. That it’s terrific? Cruz certainly thinks so. But then, everyone looks equally undeserving of the Good Life through the camera lens of a Predator drone.

Header shot is from BBC News.

Daydreams & Paving Stones is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

March 21, 2025

(De)Compressing History

One hundred years ago, North Hollywood was nothing but ranches. Back then it was known as West Lankershim. Municipally, it was not part of Los Angeles. When the drought came, the struggling ranchers mortgaged their properties to the fruit companies and agreed to be annexed into the city. They were promised water from the LA Aqueduct, but that water never came. It didn’t take long before the ranches were foreclosed and sold off to developers.

That was in the 1920s. The drought is still here of course. And apart from a small, over-developed Arts District, the renamed North Hollywood doesn’t feel very much like Hollywood. It’s blocky, suburban, and has just as strained a relationship with its ecology as ever.

Like many other branches of the LA River, the Tujunga Wash is enclosed by giant concrete slabs. Parts of it are walkable though, with gravel paths and benches placed on either side. You can find a handful of joggers on it each morning: the kinds of people who insist that they live in Valley Village rather than North Hollywood.

Cross Oxnard, going south. On your left, more nondescript suburban faff. On your right, Los Angeles Valley College, part of the city’s network of community colleges. It is a campus that can mostly be described as pleasant, and you struggle to find any stronger words for it.

Cast your gaze down, in between you and the edge of the campus. It’s the Great Wall of Los Angeles, and it’s a mural on the concrete side of the Tujunga Wash: a strange, somewhat unassuming place for an impressive attempt to capture all the horror and beauty of LA.

Started in 1978, the Great Wall is technically unfinished. Theoretically, it never will be, at least until this frustrating homunculus of a city finally empties itself into the ocean. It is a chronological history of the mass of land we came to call Los Angeles, starting way back in prehistory, and stopping with the 1984 Olympics. In between, all the things we call history, but from a distinctly, if sometimes uneven, bottom-up perspective.

We might loosely but accurately refer to this mural as a kind of people’s history of Los Angeles; appropriate, considering it origins in the New Left and the Chicano movement. SPARC, the organization that conceived and spearheaded the project, has as its mission “creating sites of public memory.” The mural’s affinities with Diego Rivera are clear, the way it swoops through different events and sews them together, trying to find different levels of grace in the anarchy.

The ideal and predictable route starts at the corner of Burbank and Coldwater Canyon Boulevards, and with the wash on your left side, goes north along the asphalt path. This takes you chronologically through the story of LA. Because of where my apartment is, however, I find myself walking the Great Wall backwards most days. Back through the Mattachine Society and the LA chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis, through the grip of McCarthyism in Hollywood and the exile of Rosie the Riveter back into the home, the internment of Japanese-Americans at Manzanar, fights for equal pay and against segregation, the zoot suit riots, the arrival of dust bowl refugees.

Keep going: the birth of the film industry in what was still a desert town, indentured Chinese migrants building the railroads, the violent transfer of the territory into American hands. Even further: the rise of the Californios and the merciless Catholic missions, the arrival of the Spanish. Further still: back to the height of the Chumash people, and finally to the strange plants and animals that inhabited Southern California before anyone ever dreamt up the idea of history.

There is a contradiction at the center of public art, one we don’t acknowledge or even always know to look for. Its purpose, at least in the abstract, is to open the viewer up to the possibility of the space. If it is a monument or memorial, then we are of course reminded of the past, commonly something that took place there. It isn’t always clear to what end we are to remember, but we can at the very least guarantee that there is some kind of different behavior expected of us.

If the art is more capacious in its subject matter, up to and including the abstract, then more often than not it exists with an eye toward the future. Quite often the city planners who assent to the art’s placement are unaware of it, but the invitation to imagine, to provoke, is always there. If we interact with this provocation in the intended way, then the compression of history becomes an unfurling of events.

Think, for example, of the giant Picasso sculpture sitting in Chicago’s Daley Plaza. Most people passing by – normally those who work nearby, normally with a smattering of tourists – don’t stop to consider what this piece of art asks of us. Put a gaggle of small kids nearby though, and you’ll see them start to climb up and down, under the weird face that looks out across the square. A spatial gap in bureaucracy and commerce is turned into a playground.

More and more however, public art seems be integrated into space’s alienation, the transformation of that space beyond the permission or even notification of those who inhabit it. Where art brings history and contingency together, its usage in the contemporary (gentrified, authoritarian) city forecloses these into something foregone.

How does the radical artist square this circle? Can it be done? My friends Tish and Adam Turl say no, at least in the context of America’s biggest cities. It’s one of the reasons they’ve relocated to Carbondale, Illinois – a city situated closer to the rust belt fringes of American urban life.

Lately, large portions of LA’s Great Wall are fenced off. It’s chainlink fence primarily. You can still see the wall clearly, but you can’t walk right up alongside it. A footbridge has been built allowing pedestrians to cut across and over the river. The bridge, smartly, isn’t particularly eye-catching. It makes for a more convenient route for some to get to campus and, potentially, will allow one a different vantage of the wall’s murals. There are also plans to expand the mural, particularly its chronicle of the 1960s, including the Watts Riots, the LA chapter of the Black Panthers, the Chicano high school walkouts. (The new segments were housed at the LA County Museum of Art while SPARC founder Judy Baca worked on them, up until this past summer.)

We’ve heard a lot about “liminal spaces” lately. They’re everywhere on TikTok and Instagram and the increasingly fractured world of the online. Liminal spaces are seemingly everywhere if you know where to look, promising the excitement of the strange, the unpredictable, the reinvented and reconceived.

It’s clear that the Great Wall, as it is originally conceived, deliberately plays with this liminality. A mural stringing together a people’s history of sorts painted on the wall of an aqueduct creates a sense of disruption, something smuggled in that nonetheless demands its place.

That a bridge is built over the wall is on its own harmless, even beneficial. Less so in the context of the general “revitalization” construction projects on the LAVC campus. Mind-numbing, mundane blocks that pretend to the stark angularity of brutalism but don’t have the bravery to really embrace it. The kind of buildings that flatten space and overwhelm the possibility of encounter with the nothing of empty time.

This is the problem. The more we notice liminal spaces, the more they are deliberately placed in the center of our already-taxed attention spans, the less liminal they become and, paradoxically, the easier it is to gloss over them. The apparent possibilities of place diminish. Its uses narrow.

This isn’t automatic. I am by no means deploying the hipster view of history, wherein the city is ruined by simple dint of trend or attention. Nor is the point here to say that the expansion of the Great Wall of Los Angeles, the artistic broadening of an Angeleno people’s history, is futile. Rather, it is to insist that public art is incapable of acting upon its viewers if those viewers are already passive. Artists forget this, often aiming for their art to “wake up” the audience, only to find that both art and audience have been rendered inert. That while they weren’t looking, history became something you pass briefly on the way to class.

It would be naive to think that the Trump presidency’s attacks on elite college campuses like Columbia and Georgetown won’t extend to less “elite” institutions. At the very least, the cuts in funding and criminalization of protest will have a knock-on effect for community colleges like LAVC. What could be a vibrant hub of a North Hollywood still clinging onto its polysemic histories runs the risk of becoming just another weight, anchoring this neighborhood and its people in static place. There is a very good chance that all of us are about to know what it looks like to live in the authoritarian city in the near-future. Whether artworks like the Great Wall of Los Angeles can play a role in driving some sort of wedge into it is an open question.

Daydreams & Paving Stones is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

March 14, 2025

Salvation

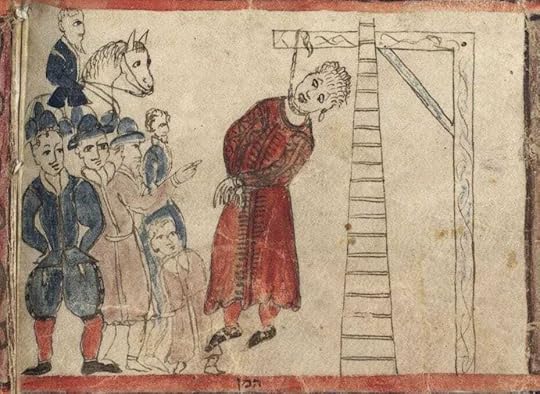

Chag Purim Sameach. In the spirit of the carnivalesque and Talmudic reinterpretation, I offer a short postscript to the typical Purim spiel. Enjoy. And please do subscribe…

“It may indeed be the highest secret of monarchical government and utterly essential to it, to keep men deceived, and to disguise the fear that sways them with the specious name of religion, so that they will fight for their servitude as if they were fighting for their own deliverance, and will not think it humiliating but supremely glorious to spill their blood and sacrifice their lives for the glorification of a single man.” – Baruch Spinoza, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

The rope was very coarse. Haman could see it would chafe and burn on his neck. He wondered if it had been woven from the same thorny trees they had cut to build the gallows. It would have made for nice symmetry, but he was quick to put it out of his mind. Rope made from vines and plant fibers was notoriously weak, completely unsuited for hangings.

Besides, he presently had more important matters to think about. Today was the day that he, King Xerxes’ chief minister, his most trusted advisor, would be executed on the King’s own orders.

Strange… the gallows he’d ordered constructed outside his home had, of course, not been for him. Yet it was he who would hang first from its towering top. It was a magnificent gallows, awe-inspiring. He stared up at it, squinting his eyes against the noon sun, and recalled his order to his slaves to carve it from the tallest camelthorn in Susa, fifty cubits high. They had done their job, he had to admit. Stretching above Haman’s sprawling gardens, the orchards of apple and pomegranate, it seemed out of place yet entirely correct.

The plan had been to watch from the Citadel, at the King’s side. To show Xerxes how he would always be the King’s unwavering protector. Some had thought the young King feckless and mercurial, easily swayed. Haman had always sneered at these whispers, thought them close to treason. It did not matter what the King’s personality was. What mattered was that he was the King.

It was as true for Xerxes as it had been for his father, the revered Darius. Darius had expanded the empire, encompassing more cities and tongues than ever before. He had built Susa and Persepolis, had rebuilt Babylon into a towering metropole. That was Darius’ lot in life, just as it was Xerxes’ lot to rule it in his father’s steps, and for Haman to serve Xerxes. Those who thought otherwise, who found reasons to refuse their lot, to refuse to serve and bow, deserved nothing but scorn.

Susa was swarming with these kinds, the traitors and opportunists. It was a fair price for the greatness of rule and conquest. But it meant that it was only a matter of time until one of them tried to get close to the King. That it was Mordecai who gave Haman the chance to demonstrate this to Xerxes was, he thought, proof that he was the most righteous minister a King could deserve. Mordecai, of all the smug and duplicitous Hebrews in the empire. Mordecai, who all those years before had given Haman food and, in return, had hung a humiliating debt of slavery over Haman’s head. It was too perfect.

As for Haman’s idea, intimated to the King, that it should not be the empire’s military who eliminated the Hebrews, but the people of Susa themselves… this was a stroke of genius, one Haman was still proud of. Not only would Susa be finally rid of a treacherous people, but the city’s populace – be they Greek, Phoenician, Arab or Ethiopian – would be given an enemy. The kind of enemy that ensures a King’s rule as protector in the eyes of his people.

And to make it all that much sweeter, Haman would watch, alongside King Xerxes, as Mordecai swung and twisted and jerked above his own estate. A sign to Xerxes that he, Haman, and everything he owned, would be in service and protection of the King.

Had he known about Esther… well, that would have called for different calculations. One of Mordecai’s kind had indeed gotten close to the King. It was Mordecai’s niece no less, and she had wormed her way so far into Xerxes’ graces that he had made her his wife. They had made a fool of Haman, that was for sure. At the very least, he would die without having ever been Mordecai’s slave.

He felt movement across the courtyard and let his eyes be drawn from the gallows. Esther and her retinue – three bodyguards, an advisor, and, curiously, a court scribe – stood just outside the doorway. It was her home, according to the King. His position in court was now held by Mordecai. The gallows, and the rope, were for Haman. He might have marveled at it had he not spent days in his cell cursing them both, his hatred for them and their people seething in his gut. Though his mouth was dry, he spit on the ground before her.

Beyond the walls, between his estate and the Citadel, the city of Susa tore itself apart. Haman had kept his gaze fixed downward during the journey from the Citadel to his estate, did his best to ignore the screams and cries, the echo of iron and stone clashing. Xerxes had decreed the Hebrews could fight back. What was supposed to be a cleansing was now merely a bloodbath. In the days to come, the fighting would subside. Or perhaps it wouldn’t. The Gods knew what lay ahead for Xerxes now.

He felt the noose tighten round his neck. As he had suspected, it scratched and itched. The rope dangled from the nape of his neck, and he watched as it snaked upward, fifty cubits high, then back down again where four hulking soldiers were taking it in their hands.

These were the last moments. It was a small audience: a sparse detachment of soldiers, Esther, and her entourage. Not even Mordecai was present. Not even the King. Everyone stood stock still. The sounds of battle on the other side of the estate walls was far away, faint. The only movement Haman could make out was the quick scribble of the scribe’s quill against the roll of parchment.

He caught the look of the soldiers’ commander. His brow was furrowed expectantly. That’s when Haman realized he was being allowed the small dignity of final words. “I have been proud to serve the King,” Haman said. His voice was cracked and reedy. “I make no apologies for my loyalty.” Then, briefly, looking at Esther, “or my hatred.”

It would be a long way up to the top of the gallows. He reckoned he would feel all of it: his breath squeezed out his lungs, his windpipe crumpling in his throat. He would feel the blood vessels pop, the muscles in his shoulders and neck and face writhing and twisting. All before his neck snapped.

It was guaranteed to be an agonizing, excruciating end. Still, he didn’t wish for a quick death. He hoped, prayed, to stay awake as long as he could, until he reached the top of the gallows. So he could look, one last time, at the Citadel. King Xerxes would be watching. Maybe Haman would catch his eye. If so, then the King would know that, whatever his other mistakes and missteps, he had never once, not for a moment, been disloyal. Xerxes would never find a better servant.

Header image is a detail from the Megillat Esther, Moshe ben Avraham Pescarol (1617).

Daydreams & Paving Stones is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

March 7, 2025

Against All Ambition

If you cannot relax, you will self-destruct. Relax too much, and you won’t exist. Your thoughts learn to wind themselves around an always climbing number of concerns and tasks and worries and goals. Our to-do lists grow, and so do our notifications. It’s getting to the point where we don’t need a phone or a tablet to get them. They live, they thrive, in our own sense of the incomplete. In the guilt that puppets us between home and work. In the nagging feeling that we aren’t good enough or simply good for nothing.

What psychoanalytical term best suits this state of mind? Is it the pleasure principle or the death drive? Can they be separated anymore? The need for quick and cheap validation is a powerful one. Its reward is shallow, but it’s normally a sure thing, if not the only option. Would Freud or Jung or Fromm or Guattari have anything to say? Or would they be too preoccupied with finding a description that can game the algorithm and put them at the top of everyone’s feed? It is, after all, perfectly possible to starve to death, be overworked, exhausted, and bored out of your skull all at the same time. What a time to be alive…

I once walked down a street in Havana and noticed I was more relaxed than I had been in years. I wondered why. After determining it had to be something more than the heat and humidity forcing me to conserve my energy, I noticed I hadn’t seen a billboard all day. I cannot recall if I even saw anything that could be considered an advertisement. Likely I had, but they were so unassuming and uninvasive that none presently come back to me. However we might think of Cuba — characterize or idealize or criticize or exoticize — I find myself stunned by how rare and unique that experience is. No matter how tight the equation of busy-ness with fulfillment grips you, it’s impossible to forget the sensation of floating upstream once you’ve had it.

A friend of mine is sometimes criticized for his lack of motivation. Though intelligent and creative, he works a modest job, has few specific goals, and generally lives an unremarkable life. I sometimes see a look on his face that reminds me of the unbothered feeling I remember in Havana. Or at least this is how I guess I looked. Life, it would seem to my friend, is not supposed to be so difficult and demanding. So he doesn’t live like it is.

Other times, I see a profound loneliness in him, an isolation he has no idea how to overcome. There was nothing particularly romantic in the blue collar workaday lives of fifty years ago. But knowing that you weren’t going to live in a hovel just because you worked an unimpressive job, that survival didn’t require herculean hustle, that most of your coworkers and friends could opt to be just as unambitious as you, allowed for a stability and connection. To opt out of ambition wasn’t such a lonely endeavor, and in fact plenty found meaning in the refusal: a first step toward a collective horizon.

Now, the social basis for “unambition” – and with it, the freedom to contemplate, to patiently tinker with one’s life, to want nothing more out of that life than to simply enjoy it – is gone. The pressures and demands that take its place are pernicious, frantic and predatory. I am convinced that until we’ve eliminated them from our psychological vocabulary, we are all bound to die of our own remorse.

Header image is Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Land of Cockaigne (1567).

Daydreams & Paving Stones is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

February 28, 2025

What's Wrong With Me?

Welcome to the February 2025 edition of Worms of the Senses, a monthly feature where I comb through the best things I heard, saw, read, and pondered in search of something like a structure of feeling. It probably comes as no surprise that February 2025 felt pointedly cruel and aggressively absurd. Not strange, not weird, not odd, and certainly (mostly) not funny. Absurd. In the existential-adjacent, Endgame and Rhinoceros kind of way. Welcome to hell. Sorry we started without you. Also…

Squid’s third album Cowards was released on February 7th. It is the group’s tightest and most cohesive, reining the post-punk avant-gardism into something still very manic and experimental. That they’ve found such a strong and distinctive direction over the course of just four years (their debut full-length Bright Green Field was released in mid 2021) is impressive. What remains intact is a kind of sensory overload, an uneasy feeling like we’re experiencing too much at once. As if every attempt at grounding ourselves is bound to become just another jagged piece of mental flotsam inundating us. Despite the chaos of Cowards being more controlled, its subject matter – examinations of evil’s banality – are probably the darkest the band has taken up.

A few examples: “Blood on the Boulders” is about the Manson murders. “Building 650” is about a serial killer friend – Frank, “a true American” – that the narrator can’t bring himself to escape, raising the question of his own complicity. Opening track “Crispy Skin” reverses this viewpoint. The narrator is a cannibal. “What’s wrong with me?” he asks, but he also implies that the world around him has let him get away with it, even accepting and encouraging his gruesome diet. (Takashi Ito’s video for the song provides an alluring interpretation for this.)

Even with the music of Cowards so compelling, it rather defies you to glean greater meaning from it. I have found a helpful, though unexpected, affinity between Cowards and Modest Mouse’s seminal 2004 album Good News for People Who Love Bad News. Both exhibit an unhinged confusion, a profound anxiety of realizing all your efforts inconsequential in an indifferent world. (As they say in “Bury Me With It,” “Life handed us a paycheck, we said ‘we worked harder than this!’”)

The difference is that twenty years ago we could laugh at this state of affairs, this universe that often seems deliberately constructed to lack sense. Not so much now, save the occasional acerbic chuckle. What’s notable here, though, is that in most instances, it’s not the violent actors themselves who are called out on Cowards, but the world that invents this violence.

What lies at the core of a world capable of this? It would be wrong (and boring) to answer this question with some kind of Marxist schematic, insisting it’s all about work. Exploitation? Feasibly. Certainly an extreme-but-ordinary form of alienation. But as Paul Rekret argues in his recent book Take This Hammer, most music is in some way mediating our relationship to work, along with the anxieties and excesses that spring from attempts to reassert some kind of control.1

The book is part of Goldsmiths Press’ Sonics Series, radical dissections of music and being that fill a very real need in today’s musical-critical landscape. Rekret’s argument doesn’t rely so much on narrowing the scope of popular music as showing us how the logic of work and exploitation stitch together our daily existence. What music tells us about this when we are conscious of it can be quite insightful, revelatory even.

One of the book’s most compelling sections is on trap music – Migos, Gucci Mane, 2 Chainz – and resituating its all-encompassing illicit hustles as forms of labor, survival. The chapter on ambient music, which has become more dominant in the streaming age, also asks us to look at the genre differently, from a style that ostensibly aims to create soothing spaces to one that contents us with our own overwhelm. Even when we are at rest, we are at work. The rhythms of our own needs and desires and those of the outside world are inevitably at odds.

Everyone understands this. If not on a theoretical level then certainly on a visceral emotional one. Which is one of the reasons that a show like Severance has gained the critical praise it has. The premise of a consciousness bifurcated, your work self versus your leisure self, unable to remember and often at war with each other, basically works. It’s not at all difficult to map a crude understanding of alienation onto this, and it’s clearly why a small but dedicated number of viewers resonate with the show. I’d be interested to see a breakdown of how many of the show’s fans have worked for any length of time in white collar office environments.

I’ve seen Severance described as Twin Peaks meets Office Space, and that shoe fits, even if the writers make it a point to do something very particular with the formula. Much of it feels like the direction Michel Gondry’s work might have taken had his oeuvre not become so banal. The wintry gray northeastern setting, the understated acting choices, the modern-anachronistic technologies; all come together to create a setting where the utterly mundane produces the excessively weird. Some viewers seem to find the whole aesthetic anodyne and vague, difficult to get drawn into, but that’s the point. You’re supposed to be estranged.2

The problem is that, even with this premise so fleshed out, it isn’t immediately apparent where it can go without completely upending the logic of that world. I was skeptical they’d be able to do much past the first season, but the second season is being smart about it. Further exploring the structures and histories of Lumon – the company that “severs” its employees – in essence reveals it to be a cult of sorts, complete with its own strange mythos and origin stories that justify its quotidian cruelties. Again, it may be a bit obvious, but it’s dramatized in a compelling way.

Now switch streams. All culture is either alienating or expresses alienation, articulating forces that are somehow fully human and yet appear well beyond our control. And if it is beyond our control, if there is no route of exit, then what’s the point of exploring it through the arts? That, essentially, is the a priori question that every absurdist work has to answer. Most absurdist art simply finds a more specific way to pose the question. Necessary, but not exactly an answer. Which way to get out?

The films of Sara Gomez, which I’ve been binging on the Criterion Channel, provide one of the closest things to a plausible answer I’ve found in some time. Gomez was a Cuban filmmaker. She died in 1974 at the age of 31. Her films explored problems of daily life in the era after the revolution. Most are under an hour in length, and many are less than twenty minutes. I’m sure people would disagree about whether we could call them straightforwardly absurdist but they do take on everyday, almost mundane problems, in puckish ways.

Un documental a propósito del tránsito, or A Documentary About Traffic, documents traffic accidents in Cuba and the efforts of local revolutionary governments to better educate residents on safe driving practices and to better redesign city streets. It interviews drivers, urban planners, government officials. Reading this, you would think it watches more like an industrial informational video, but the action is interspersed with title cards whose almost cartoonish playfulness contrasts with the dry statistics of accidents and injuries. It is, essentially, an attempt at popular education that uses its filmic qualities in an extremely self-aware way. Two of her final films, Atención prenatal (Prenatal Attention) and Año uno; Mi aporte (First Year) bring the same sensibility to the massive changes in prenatal and postnatal care in Cuba as its free healthcare system was established. Given the dismal state of healthcare before the revolution, these short docs served to popularize the idea that working women deserved and should expect better.

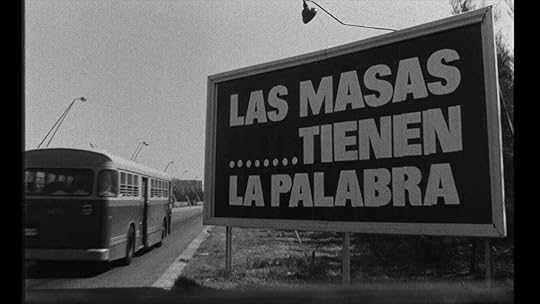

Poder local, poder popular, or Local Power, Popular Power, examines the neighborhood-based revolutionary councils of Cuba through the eyes of a small sugar mill town as it confronts shortages of goods. Local workers and party activists are interviewed, keywords and phrases emphasized by way of (once again) bold title cards. It is a short and open-ended film, without much in the way of resolution, but it shows new and different experiments in how to organize daily life. If existence is meaningless, create meaning. How does one find meaning when circumstances are beyond your control? You reach for them as if they are in your grasp. There’s a good chance that the only way to do so effectively is collectively. There’s no guarantee you’ll be able to create that meaning. Then again, it’s not like you have any choice but to try.

Header image is a still from Takashi Ito’s video for Squid’s “Crispy Skin.”

Daydreams & Paving Stones is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

1A more in-depth review of Take This Hammer is forthcoming, likely for the Historical Materialism website.

2At this point the verfremdungseffekt of Brecht’s plays – alienating the audience to some degree so they can look critically at the work – is actually so commonplace in late capitalism that writers often don’t even realize they’re employing it. Of course, those who are aware of it do it better, but sometimes it works even on accident. As to whether the writers of Severance know what they’re doing, the jury is still out, but signs are promising.

February 24, 2025

Pacts of Memory (Iberian Daydream, final part)

For most of November, I was on my honeymoon in Spain and Portugal: Porto to Lisbon, then to Seville and Barcelona. I took the opportunity to try my hand at travelogging. The initial hope was to have this entire series completed in the first days of 2025, but disaster intervened. It has taken some time to return to completing the experiment. The results – found here, here, here, here, and below – have been enjoyable to write. Hopefully they’ve been enjoyable to read. If not, then good news: we’ve come to our final city: Barcelona. Wide open boulevards. Syndicalist bars. Fractured histories. Finally, do subscribe if you haven’t already.

XXIV.Barcelona isn’t Paris. Paris had Baron Haussmann. Five years after the 1848 revolutions, he was appointed by Louis Napoleon to redesign the city. From 1853 to 1870, Paris was completely renovated. Its slums were emptied, the city center opened up. Gone were the narrow streets that made the construction of barricades easier.

Many suggest that the wide boulevards were intended to tamp down urban insurgency. It didn’t work. The year after Haussmann was dismissed from his post, workers, small artisans, and ordinary Parisians took over the city and established the first revolutionary commune in history. Haussmann’s former boss Napoleon fled too.

No redesign like this ever took place in Barcelona. La Rambla has existed there since the 1500’s. It has always been open and airy, stretching a little over a kilometer from the Plaça de Catalunya all the way down to Port Vell and the Mediterranean Sea. During the Civil War from 1936 to 1939, when all the city’s factories were essentially run by their workers, La Rambla was regularly flooded by mass demonstrations. Red flags, rifles raised in the air, the whole splendid panoply. All of the dramatic scenes that Orwell described.

The headquarters of the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista was a few hundred yards down the thoroughfare. Now the building is an expensive hotel. Nonetheless, Barcelona’s history disproves the wide-open avenue as a deterrent to urban revolt.

Barcelona isn’t Spain either. Not really. La Rambla reminds you of this. Seville wanted us to leave with the idea of Spanishness as a quintessentially traditional structure of feeling. The city’s primary pastime, as far as we could tell, is Catholic processions. We saw an unusually large number of locals wearing slacks and button-downs. That wasn’t the impression in Barcelona.

The city’s signs were in Catalan, then Spanish, and often not even Spanish. Below the massive billboards for expensive luxury brands bobbing over the street, La Rambla insisted on something chaotically grimy, cobbled together, defiant and independent. At the intersection of Plaça de Catalunya and La Rambla there is a monument to Francesc Macià, president of the Generalitat de Catalunya from 1931 until his death in 1935. Under Macià, during the Second Spanish Republic, Catalonia achieved autonomy and, according to some, got as close as it ever has to gaining full independence in the modern era.

Of course, if 2017’s referendum is to be believed, then Catalonia is indeed its own country. The final vote tally of that referendum was 92 percent in favor of independence, 8 percent for remaining part of Spain. Of course, the total turnout for that vote was only 43 percent. Because the decision to hold the referendum in the first place was boycotted by anti-independentist parties in Catalonian parliament, it was declared an illegal ballot. The National Police Corps and the Guardia Civil were deployed to physically prevent people from voting.

During forty years of Franco, the city was forced to be something other than what it naturally is. Speaking Catalan was illegal. The communists and anarchists and other workers’ organizations were driven underground or wiped out entirely. Barcelona remained a hub of shipping and heavy industry, but its horizons had been repressed, its people’s souls penned in. It remained relatively underdeveloped after Franco’s death and the fall of fascism.

That changed when the Olympics came in 1992, with requisite buckets of cash and redevelopment schemes. No longer was the city atomized by iron authoritarian heels. Thirty years later, it is difficult for many to insist it isn’t atomized once again, albeit by a different and sneakier force. If anything has been made apparent in the writing of this series of travelogues, it is that the city of modern Europe often confuses reification for memory, holding forth a city’s most distinctive histories and cultures in their most static form so that outsiders can gawk at it, wide-eyed and slack-jawed. And if that history is unfinished, as it so often is? If it wounds still itch? If its people are restless? The city of modern Europe doesn’t have an answer for this.

A few blocks off La Rambla, wedged into the narrow streets of El Raval, is Bar Llibertaria. Its drinks are cheap, its tapas are filling, and it was founded in the early 2010’s by a member of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, the anarchist trade union that played a central role in resistance to the dictatorship. As one might expect, the walls of Bar Llibertaria are covered in posters from the 1930s beseeching readers to join the CNT and resist the rise of fascism. Peasants and workers, often armed, smiling and broad-shouldered, drawn and painted in that warm, dusky light. Oranges, yellows, browns, blacks, various shades of red. The entryway has a painted statue of a young boy in a newsie cap hawking copies of Solidaridad Obrera.

Mrs. Daydream and I felt right at home. We ate, we drank, we talked politics with the bartender. We told her that the recent elections made us want to go home even less. She told us she was from Poland, where Andrej Dude ruled for nearly a decade before the current centrist government swung into power. She was well-acquainted with the havoc of the hard-right. It was why she came to Barcelona.

XXV.I dislike Gaudi. This doesn’t make me all that unique, but many people who know me are surprised when I tell them. Part of my dislike is that, across timelines, there really isn’t anything all that special about his aesthetic. There’s no reason that the flowing lines and over-baroque ornamentation that characterize his work shouldn’t have become the standard in every city. There was nothing that should have made his work less architecturally ubiquitous compared to, say, Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rohe. We act as if the city is an intentional thing, that a coordinated set of choices guides it. Certainly there are choices made, but they just as often conflict with each other or take random twists and turns that make no sense concerning what came before. Only by sheer accidental happenstance do certain designers’ and architects’ aesthetics become widespread while others become curiosities and novelties.

Curiosities and novelties can be lucrative. Anything that sticks out enough can be enclosed with a rope and tickets sold to see it. Thus Gaudi, and what I dislike about him. Given his aesthetic, how easy it is to lump the merely whimsical with the strange and surreal, he is supposed to be fascinating to “people like me.” And when people who make money off tourists think of “people like me,” they think of us as children with money. Easily amused, constantly longing, but unable to remember much of anything.

The journey toward Park Güell was a rather long one. There are, of course, countless Gaudi houses scattered throughout Barcelona; most of them will allow you to walk around inside for about thirty euros. Park Güell is a large complex of parks, gardens, buildings and architectural elements designed by Gaudi and opened to the public in 1914. Spanning about 47 acres, it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984. Despite my dislike of Gaudi, it seemed like something we should see. Our challenge was that it was three miles from the city center where we were staying. We decided to walk.

We didn’t quite register two things. The first is that Barcelona can get very hilly. The second is that the neighborhood of La Salut, where Park Güell is located, is primarily residential and very working-class.

By the time we arrived, we had already been walking for some time. The hills we encountered when we entered La Salut were uninviting enough. Then we started to notice the apartment balconies. The number of Catalan flags was expected. The number of signs telling tourists to go back to the city center, or to simply go home, was less expected.

Barcelona hates tourists. As a tourist, I can confirm this is absolutely the correct stance to take. Nobody needs reminding of how annoying we can be, particularly if we’re American. The Olympics kicked down the door for a free market fundamentalism that, for the past three decades, has put working-class lives under economic siege and transformed wide swathes of the city into a commercial Disneyland version of itself. There was a time when this kind of fuckery was seen as uniquely American, bound up with the particularly stupid and vicious United Statesian equation of anything the least bit uncommodified with communism.

Whether or not that was ever a fair equation is beside the point now. We know the model has thoroughly transformed the social spheres of every western European country and virtually any nation friendly to the United States. It’s happened in China and Russia too, just through somewhat different mechanisms, but the thrust is the same. Barcelona simply had the misfortune of facing to the west.

Throughout this entire trip, I found myself wondering what a different model of experiencing another city might look like; one that isn’t premised on turning every home into a hovel and every neighborhood into a destination.

I can’t say I’ve come up with one. Though it does seem that travel conceived as a luxury, a practice that assumes safe and conspicuous consumption, is bound to homogenize and erase. We might have thought ourselves different from your typical American tourist; thoughtful, curious, courteous, left-wing, sensitive to history. These attempts were probably no match for our vocal fry.

The ire of Park Güell’s neighbors is justified. When we finally arrived, it was mid-afternoon. The park was already teeming with the shrill touristic bedlam: kids crawling over the architecture, exhausted parents glad to have a moment that their children aren’t whining about being bored, hordes of people stumbling over each other for a picture. In the background, the sprawl of Barcelona: skyscrapers and spires, antenna arrays, ancient ruins weaving through modern neighborhoods reaching over hills. If I lived here, with all these layers of history blooming up from the ground in front of me, and I had to compete with braying gaggles of the hapless, I too would be well beyond frustrated.

We did not have the opportunity to add to the swarm. By the time we arrived, it was mid-afternoon. Somehow we hadn’t clocked that the park limits the number of people that can enter on any given day. The park was full, and no more tickets were available. Serves us right.

XXVI.Park Güell is close to the edge of the Serra de Collserola mountain range, right as the urban sprawl gives way. To get to Castell de Montjuïc, we had to cross town, all the way to the Mediterranean coast. The foundation stone for Castell de Montjuïc was laid in 1640. The next year, the Catalan Revolt against Spain kicked off, and the castle saw its first battle.

Since then, the castle’s stolid corridors and courtyards have been something of a weathervane for the fortunes of Catalanisme, between independence and Spanish domination. From the top of Montjuïc hill, you can see not only the practical whole of Barcelona, but the city’s massive port, a crucial nexus of cross-Mediterranean trade for some several thousand years. Thanks to the castle’s position, it can be used to either defend or bombard the city. There is a distinct sense that they who control Montjuïc will be in control of Barcelona, and therefore wield decisive influence over the Iberian Peninsula.

During the Civil War, the republicans installed massive anti-aircraft guns to protect the fortress against Italian air attacks. After Franco’s victory, they became a reminder of both defeat and the seeming impregnability of Spanish fascism. Lluís Companys, the left-wing regional president of Catalonia during the Civil War, was executed at Montjuïc in 1940, and there is a small memorial dedicated to him near the castle’s moat. Countless republicans, anarchists, communists, socialists, and trade unionists were tortured and killed here. In 1963, Franco converted the castle into a military museum.

Today, Castell de Montjuïc functions as a municipal center. It hosts concerts and exhibitions. Our bartender at Bar Llibertaria had recommended an exhibit here of photographs related to state repression in the Franco era. It was, naturally, difficult to take in. Testimonies of torture, executions, rape, loved ones abducted by police. Women could be arrested and imprisoned for simply being related to anyone suspected of being a red. Some 12,000 children of republican parents were taken from their imprisoned mothers and shoved into orphanages where they would be essentially indoctrinated by the state. The brutal execution of Federico Garcia Lorca, perhaps Spain’s greatest 20th century poet and playwright, is mentioned. So is the Stanbrook, the English cargo ship that took the last 3,000 republicans who were able to flee as the republic fell in 1939.

Here I learned that “the right to memory” is actually enshrined in Spanish law. The 1977 Amnesty Law that allowed Spain to transition to democracy after Franco’s death has often been called Pacto del Olvido, or “the Pact of Forgetting.” The brutality of the Civil War, and of Francoist fascism, went unaddressed. Torturers and executioners were unpunished. The disappeared remained the disappeared. Mass graves went untouched. So did public fascist symbols and street names.

The Ley de Memoria Histórica of 2007, passed over the objections of the conservative Partido Popular, sought to rectify this. The government dug up the mass graves, attempting to identify remains and provide restitution to the victims’ families. Coming to power in 2011, the right-wing PP government of Mariano Rajoy sought to essentially strangle the Law of Historical Memory, slashing its funding by 60 percent.

After the center-left PSOE returned to power in 2018, Franco’s grave in the Valley of the Fallen (just outside Madrid) was moved. Though Spain’s parliamentary social democrats are broadly in line with those around Europe – dedicated more to the idea of a humane market than anything resembling workers’ power – it would be wrong to say that the relocation of Franco was a sign of respect to the dictator’s descendants. The Valley of the Fallen has long been a site of celebration for the far-right, a place where the bodies of 30,000 executed republicans and leftists had been moved without their families’ knowledge into one of the world’s largest mass graves. Franco’s tomb was one of only two ever marked. The other was José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the Falangist Party.

A monument built on a literal mountain of bodies. Though Franco is now interred in a private family plot, the 490-foot cross still stands, as does the basilica, bigger than St. Peter’s in Rome. Compared to this, the exhibition at Castell de Montjuïc could only be understated, memories that speak plainly for themselves, without adornment or embellishment. It is almost as if fascism believes that any memory untriumphant in timbre isn’t worth commemorating. Yes, fascists exiled from power love to cite examples of their fictional victimhood, but after they conquer, these days become occasions to thump their chests and bellow victory. What, exactly, becomes of memory, in all its whispering contradictions, when this regime prevails?

XXVII.You can understand why, as the Portuguese Revolution unfolded, Henry Kissinger so openly feared it. The rise of workers’ and soldiers’ councils in Portugal was the spearpoint of a broader context. Greece (where the generals’ junta had just fallen) and Italy both had strong and militant far-lefts. There was Tito’s Yugoslavia, whose repeated attempts to build a socialist model separate from Soviet influence made the country something of a wildcard. That Franco’s regime was teetering wasn’t particularly surprising – he was, like the Portuguese Estado Novo, isolated and geriatric – but it did put a question mark over a key US ally.

The material of this Red Mediterranean was on all sides of the sea. Libya had declared itself socialist (albeit a highly religious, idiosyncratic, and ultimately authoritarian variety). Memories of Algeria’s struggle for independence barely a decade before, as well as its more recent experiments with workers’ control, also got western observers’ hackles up. In this context, it is worth remembering how many historical empires did not differentiate in the way we do between the Mediterranean’s northern shores (Europe), southern shores (Africa), or eastern shores (Levant). These different regions weren’t separated by the Mediterranean but brought together by it.

However incorrect it may be to view the Mediterranean as the center of the world, it was understandable for pre-capitalist empires. Without access to this sea, global trade was severely hindered. For Rome, Macedonia, Constantinople, empires and dynasties alike, the Mediterranean was the horizon.

Empires change geography, but so do revolutions. Or, more specifically, they change our conceptions of geography. The idea of a socialist Mediterranean, of the gate between Africa, Europe, and Asia turned red on all sides; this would shift the fortunes of a late capitalism already reeling from the collapse of the postwar boom. The same for an imperial order bogged down in Vietnam and reviled by insurgent people the world over.

A different timeline comes into focus; different memories, different pasts colliding with the present, producing different futures. It didn’t happen, but it was in the cards. We can see here, in this brief “what if,” the material consequence of memory. If history were simply one thing after another, then the right to memory wouldn’t matter. But when we see history rather as a series of contingencies, each moment pulsing with different potentials, this right becomes urgent, sacred even. Empires carve a path for memory, shifting and blocking its direction. Revolutions unleash it, allowing it to touch down wherever it might. Its previously solid barriers become flimsy and pliable.

XXIII.Yes, the ‘92 Olympics turned Barcelona into a “global city,” a city that was on everyone’s map, a place whose culture was fit to be experienced by people from around the world. The Soviet Union had imploded the previous year, and the only language available for global community was that of the market, of commerce.

It remained that way even through the financial crisis of 2008 and Spain’s economy neared total collapse, along with the other economies of Mediterranean Europe. The European Central Bank, notoriously, shamelessly, demanded more pain from the PIIGS nations to pay off their debts. Living standards still haven’t recovered.

Then came Covid, leaving every city still and silent. The explosion in tourism that followed made Barcelona one of the top three most visited in Spain. From the sound of it, the streets started to swarm with gawping boors who would be as annoyed as any Catalonian if their own city became not theirs. Some studies found that there were neighborhoods where almost half of all residential units had been turned into short-term rentals.

In the early months of the pandemic, architect Massimo Paolini penned a “Manifesto for the Reorganisation of the City after COVID-19.” This was, essentially, an attempt to map a degrowth Barcelona. Its demands were broad, but reigning in tourism played a large role. Ban cruise ships from the city’s ports. Freeze the expansion of the airport. Reject the building of museums explicitly aimed at tourism. Cease city investment in building the Barcelona “brand.” These work in tandem basic Right to the City demands like expansion of green spaces, the decommodification of housing, and the lowering of rents.

This last point was the central demand of the demonstration we encountered on our last night in Barcelona. We had seen these fliers posted from the minute we showed up, but only after seeing them several times a day did we bother translating them. S’ha acabat… Abaixem els lloguers. “It has to end… Let’s lower the rents.”

Sure, the fliers were hard to miss, but we had no way to know how big this demonstration would be. We found out coming back into the city center from Montjuïc. It was easily between 100,000 and 200,000 people, thrumming through the wide streets of central Barcelona. Loud, militant, banners of tenant groups and labor unions, a smattering of Palestinian flags, as well as flags of several far-left groups.

One of the hardest to miss among these flags is a red and black one with the initials of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo. It was their posters that covered the walls of Bar Llibertaria. They have a long history in Catalonia generally and in Barcelona in particular.

Whatever criticisms one has of anarchism — and there are plenty, including one we’ll get to presently — the CNT continues to have a following because of its unwavering defense of radical workplace democracy. This didn’t prevent them also made one of the most maddeningly tragic blunders in revolutionary history during the height of the Civil War. Seeing their influence, and believing in an independent, socialist Catalonia, President Companys approached the anarchists during the war’s height and did what virtually no bourgeois elected representative has ever done: he offered to hand power over to them. Parliamentary rule would become direct democracy. But the CNT turned him down. Being the good anarchists they are, wielding power didn’t become them.

One group that definitely loves to wield power? Fascists. And despite the idealist protestations of anarchists, anti-power never bests power. Things fell apart after Companys’ offer was rebuffed. The left antifascist coalition fractured. Moscow ordered the Communist Party to turn on their allies. Barcelona fell. Companys fled to Paris. Eighteen months later, France was in the hands of the Nazis, and Companys was sent back to Spain where he was executed at Montjuïc.

Still, the CNT survived the Franco years, and the fall of the Soviet bloc. At one glance, these flags represent the durability of revolutionary ideas. At another, the catastrophic failures that smothered the promise of a Red Mediterranean and haunt Barcelona. A Barcelona that stepped onto the world stage thanks to the commercial spectacle of the Olympics, or one that provides for its residents, offering them the chance to remake the city and themselves. Memories of what was, and what could have been.

I know which city I want to visit. I also know which one actually exists. All I can plead is that if we go to these places only to see what exists, then we sell short both ourselves and our destination.

All photos by Kelsey Goldberg and the author.

Daydreams & Paving Stones is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

February 6, 2025

Where Stars Make Dreams and Dreams Make Stars

I will be speaking at La Grand Transition conference in Montreal this coming May. My paper, “That’s Not Me: Music and Space In Gothic Capitalism,” is part of the launch of Adam Turl’s book Gothic Capitalism: Art Evicted From Heaven and Earth. More information, including registration and exact dates and times, are at the conference’s website. Please also remember to subscribe.

1.An old colleague from New York reached out. He was in Los Angeles for a few days and suggested meeting up for drinks. It was Friday afternoon, and I suggested an unassuming cocktail lounge tucked in the corner of Sunset and Argyle. Walking in, he was immediately struck by the contrast. Outside, it was bright and noisy, grimy around the edges but somehow resplendent. Faded glamor made more glamorous in its fading.

Inside the windowless bar, it could have been any time of day or night, anywhere in the world. Pleather seats and barstools, formica tables, brass railings. Dark and cool. The faint smell of bar cleaner and metal beer taps. My friend observed that separately, the two atmospheres were nothing of particular note. Contrasting them, particularly considering their tight coexistence, made for an effect that was, according to my friend (hardly a philistine when it comes to film), Lynchian.

A friend from Scotland was visiting the city. We spent an evening catching up. He told me he had spent the day at the Museum of Jurassic Technology, an LA institution infamous for its aggressive strangeness. Fashioning itself with a tip of the hat to the original definition of museum – a place dedicated to the muse – it is perhaps best described as a postmodern cabinet of curiosities. It exhibits are filled with strange oddities and curatorial non sequiturs, inviting the visitor to glean unorthodox meaning. Or, as my friend put it: It’s like the inside of David Lynch’s head.

2.Orson Welles called Los Angeles “a bright, guilty place.” David Lynch, upon his arrival, noticed the brightness. “I love Los Angeles,” he wrote in Catching the Big Fish. “I know a lot of people go there and they see just a huge sprawl of sameness. But when you’re there for a while, you realize that each section has its own mood. The golden age of cinema is still alive there, in the smell of jasmine at night and the beautiful weather. And the light is inspiring and energizing. Even with smog, there’s something about that light that’s not harsh, but bright and smooth. It fills me with the feeling that all possibilities are available. I don’t know why. It’s different from the light in other places.”

Lynch loved LA’s light. He saw magic in it. But he also didn’t shy from its darkness. He understood this city’s guilt, its talent for hoarding violent secrets, its sliding door dimensions of intrigue and menace, conflicting truths laid on top of each other like panes of glass.

3.The observation that Los Angeles is a city of simulacra is lazy. Not because it’s untrue (Baudrillard was correct enough) but because it tends to stop there. It misses the fact that the simulacrum must be made somewhere. Life takes work, even at its most quotidian.

By virtue of the activities that took place there, no matter how hidden, a location has depth. This isn’t even to mention the ecological deep time a place possesses. However, because so much of the labor of the Hollywood culture industry and adjacent spheres is dedicated to flattening, the depth is refracted, diverted, hiding in plain sight. Finding the “soul” of this city only requires the smallest scratch beneath its surface, but the paths you find underneath are winding, strange, full of mirrors and corridors to nowhere. You see everything for what it is, but what it is hides stories pulled from real and fictional histories crossing countries, continents, and timelines.

This tightly wound contradiction encompasses just about every aspect of daily Angeleno life. It’s part of the reality in every late capitalist city, particularly considering the role tourism plays in so many big urban economies. Making a city “consumer-friendly” requires this fool’s errand flattening. But no city is quite as adept at it, nor puts it so squarely in the center of its existence as it musters its way through the deep time of the desert and chaparral.

4.There is, for sure, a symbolism in the timing of Lynch’s passing, as the worst and most destructive wildfires in LA history ripped through the city, wiping out both history and ephemera. Lynch’s emphysema made it difficult to travel long distances. According to him, he was unable to do so much as cross a room without getting winded. That he and his family had to evacuate almost certainly exacerbated his condition. A more sentimental writer would say it’s because Lynch couldn’t bear to see this city brought to its knees like it is now.

Symbolic, yes, but way too on the nose for Lynch. In fact, it may be fair to say that while his LA films were deeply mysterious, they weren’t symbolic. What they told us about this city was siphoned through myriad different superstructural modes and manifestations, rising up from a deeply troubled and exploitative reality. Not reflections, but expressions: distorted and mutated.

5.Lynch was no radical. At least not on any traditional, straightforwardly political axis. His own beliefs seem to have been a strange mishmash of small-town conservatism (he had praise for Reagan), Hollywood progressivism (he supported Bernie Sanders in 2016), and New Age mysticism (his love of Transcendental Meditation). However, he drew out one of the often-overlooked parallels between radicals and conservatives: a deep ambivalence toward modernity.

It is one thing to illustrate how this gestates in the environment of a small town. Laura Palmer’s demons in Twin Peaks, powerful as they are, were the product of deeply private traumas. Her father’s sexual abuse prompted her to construct an increasingly extreme alter-ego. So potent is this reconstituted persona that she can show up in people’s dreams well after her death. As for Bob, the literal demon that possesses her father Leland, he is free to jump from body to body, visible only for brief moments in cracked mirrors.

The demons of the big city are of an entirely different nature. Yes, the Mystery Man of Lost Highway singles out Fred and Renee Madison to terrorize, but he does so through videotapes, camcorders, and cellular phones. Items designed to replicate moments, to snatch up your image and make it available to the whole world, manipulating and reinterpreting you, even turning you into an entirely different person – i.e. Balthasar Getty’s Fred Dayton and Renee’s doppelganger Alice Wakefield.

6.The perverse, impossible compulsion to somehow permanently transform into this moveable image tears people apart in Lynch’s Los Angeles. It’s portrayed in Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire, both to terrifying effect. In both of these films – which, along with Lost Highway, make up Lynch’s unofficial “Los Angeles trilogy” – the artist (be it Fred Madison, Diane Selwyn, or Nikki Grace) inhabits a landscape that can adeptly deceive us into thinking it will always be standing. In actuality, this landscape might unexpectedly move and rearrange itself, remaking its reality so abruptly that we are liable to be crushed in its moving parts.

Writing about Paris, Walter Benjamin saw in its winding streets and historic buildings “dialectical images,” places where memory and utopian dreams were brought together. The locales of Lynch’s LA are the opposite. Almost inert, they have neither memory nor future and are emptied of geographical specificity. Like sets on a soundstage.

Most of the buildings and landmarks of Mulholland Drive are so sun-drenched as to seem like sets under blinding stage lights. Lynch uses the Angeleno brightness he fell in love with here. The apartment complex Betty Elms moves into, Winkie’s Diner, Diane Selwyn’s craftsman-style bungalow: these all have the designs of Hollywood chic, but they are somehow aloof, their stylishness experienced as cold and estranged.

They are also moved between with relative ease. Some filmmakers give you a sense of how far characters might have to travel between different sites of action. Not in Lynch’s LA. These locations could be five minutes from each other or an hour without traffic. This points to an oddity of Angeleno urban design, the truth behind the quip of 72 suburbs in search of a city. Lynch is right when he says that each area and neighborhood has a character all its own (though his lights deliberately wash that out in Mulholland Drive). What he doesn’t say is that these neighborhoods fit together with very little reason.

7.Just as easily, human beings are cast and recast in this world, replacing and interchanging with each other, leaving some without anything like a sense of self. Places can do the same. You could say it’s because of the ruthlessness of the Hollywood system, but here it feels as if this cutthroat rot has infected everything around it, prompting the city itself to act erratically.

The most recognizable Los Angeles location in Inland Empire is the Walk of Fame. This is, as anyone who has visited can confirm, one of the dirtiest and grimiest places in all of Hollywood, where the most glamorous stars are memorialized next to cheap souvenir shops and homeless encampments. Lynch shows it exactly as it is. When Nikki Grace/Sue Blue bleeds out next to a pink terrazzo star between three conversing unfortunates, we see the various disparate worlds and planes of existence that have made up the film being brought together without any pretense or makeup. That is, until we realize it’s just another scene in Nikki’s movie. Not even the filth can be trusted in Hollywood.