Adam Thierer's Blog, page 140

March 13, 2011

A Vision of (Regulatory) Things to Come for Twitter?

Twitter could be in for a world of potential pain. Regulatory pain, that is. The company's announcement on Friday that it would soon be cracking down on the uses of its API by third parties is raising eyebrows in cyberspace and, if recent regulatory history is any indicator, this high-tech innovator could soon face some heat from regulatory advocates and public policy makers. If thing goes down as I describe it below, it will be one hell of a fight that once again features warring conceptions of "Internet freedom" butting heads over the question of whether Twitter should be forced to share its API with rivals via some sort of "open access" regulatory regime or "API neutrality," in particular. I'll explore that possibility in this essay. First, a bit of background.

Twitter could be in for a world of potential pain. Regulatory pain, that is. The company's announcement on Friday that it would soon be cracking down on the uses of its API by third parties is raising eyebrows in cyberspace and, if recent regulatory history is any indicator, this high-tech innovator could soon face some heat from regulatory advocates and public policy makers. If thing goes down as I describe it below, it will be one hell of a fight that once again features warring conceptions of "Internet freedom" butting heads over the question of whether Twitter should be forced to share its API with rivals via some sort of "open access" regulatory regime or "API neutrality," in particular. I'll explore that possibility in this essay. First, a bit of background.

Understanding Forced Access Regulation

In the field of communications law, the dominant public policy fight of the past 15 years has been the battle over "open access" and "neutrality" regulation. Generally speaking, open access regulations demand that a company share its property (networks, systems, devices, or code) with rivals on terms established by law. Neutrality regulation is a variant of open access regulation, which also requires that systems be used in ways specific by law, but usually without the physical sharing requirements. Both forms of regulation derive from traditional common carriage principles / regulatory regimes. Critics of such regulation, which would most definitely include me, decry the inefficiencies associated with such "forced access" regimes, as we prefer to label them. Forced access regulation also raises certain constitutional issues related to First and Fifth Amendment rights of speech and property.

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 got this ball rolling with its mandated access provisions for local phone service. To make a very long and tortured history much shorter, this was a battle over how far law should go to force local telephone companies to share their phone lines with rivals at regulated rates. (Check this old piece of mine for a flavor of how well that turned out.) The advocates of open access regulation eventually turned their attention to cable systems and tried (but failed) to apply similar sharing / access rules there. Following those fights, which involved many nasty court skirmishes, the Net neutrality wars broke out. Net neutrality is a type of forced access regime for broadband platforms. Although Net neutrality regulation would not necessarily require carriers to share networks with rivals, it would at least require that platform providers play by special access and interconnection rules set by federal regulators.

Forced access provisions have been used in other contexts. We might think of the provisions we saw at work in the Microsoft antitrust case as a form of forced access regulation. Some may also recall the interconnection provisions that governed AOL's instant messaging service following its merger with Time Warner (discussed more below). There are other examples but I think you get the point.

New Frontiers for Forced Access Regulation?

All this history is well known to all readers of this blog and followers of communications policy. The reason I repeat it here is because this fight is now spreading to new sectors, platforms, and technologies.

For example, "search neutrality" is one of those new frontiers of the forced access fight. Some academics and regulatory advocates are pushing for rules that would govern how search results are shown or for special requirements on search providers to eliminate supposed "search bias" or to ensure search "fairness" of various sorts. Make sure to read James Grimmelmann's terrific treatment of the concept from his chapter in TechFreedom's book, The Next Digital Decade, and then also listen to this podcast featuring Danny Sullivan dissecting the issue.

Some critics also want to treat search engines (and Google in particular) as "essential facilities." In another essay from The Next Digital Decade, Geoff Manne has done a good job pointed out why that's such a misguided idea.

Similarly, some folks (such as danah boyd) are already calling for Facebook to be regulated as a public utility or essential facility. I responded in my essay, "Facebook Isn't a "Utility" & You Certainly Shouldn't Want it to Be Regulated As Such," in which I pointed out that Facebook isn't exact a "life-essential" service that is gouging customers, who have plenty of other choices in social networking services.

Adverse Possession & API Neutrality for Twitter?

An equally interesting battle is now set to unfold for Twitter following Friday's announced changes. To get a flavor for what might lie ahead for the company, we might begin by taking a second look at what Harvard University's Jonathan Zittrain proposed in his 2008 book, The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It. In that book, Zittrain suggested that "API neutrality" might be needed to ensure fair access to certain cyber-services or digital platforms to ensure "generativity" was not imperiled. On pg. 181 of the book, Zittrain argued that:

"If there is a present worldwide threat to neutrality in the movement of bits, it comes not from restrictions on traditional Internet access that can be evaded using generative PCs, but from enhancements to traditional and emerging appliancized services that are not open to third-party tinkering."

After engaging in some hand-wringing about "walled gardens" and "mediated experiences," Zittrain went on to ask: "So when should we consider network neutrality-style mandates for appliancized systems?" He responds to his own question as follows:

"The answer lies in that subset of appliancized systems that seeks to gain the benefits of third-party contributions while reserving the right to exclude it later. … Those who offer open APIs on the Net in an attempt to harness the generative cycle ought to remain application-neutral after their efforts have succeeded, so all those who built on top of their interface can continue to do so on equal terms." (p. 184)

This might be a fine generic principle, but Zittrain implies that this should be a legal standard to which online providers are held. At one point, he even alludes to the possibility of applying the common law principle of adverse possession more broadly in these contexts. He notes that adverse possession "dictates that people who openly occupy another's private property without the owner's explicit objection (or, for that matter, permission) can, after a lengthy period of time, come to legitimately acquire it." But he doesn't make it clear when it would be triggered as it pertains to digital platforms or APIs.

As I noted in the first of my many reviews of his book, there are many problems with the logic of API neutrality or the application of adverse possession in these contexts. Here's my critique of the "API neutrality" notion (again, this is from 2008):

First, most developers who offer open APIs aren't likely to close them later precisely because they don't want to incur the wrath of "those who built on top of their interface." But, second, for the sake of argument, let's say they did want to abandoned previously open APIs and move to some sort of walled garden. So what? Isn't that called marketplace experimentation? Are we really going to make that illegal? Finally, if they were so foolish as to engage in such games, it might be the best thing that ever happened to the market and consumers since it could encourage more entry and innovation as people seek out more open, pro-generative alternatives.

Consider this example: Now that Apple has opened to door to third-party iPhone development a bit with the SDK, does that mean that under Jonathan's proposed paradigm we should treat the iPhone as the equivalent of commoditized common carriage device? That seems incredibly misguided to me. If Steve Jobs opens the development door just a little bit only to slam it shut a short time later, he will pay dearly for that mistake in the marketplace. For God's sake, just spend a few minutes over on the Howard Forums or the PPC Geeks forum if you want to get a taste for the insane amount of tinkering going on out there in the mobile world right now on other systems. If Apple tries to roll back the clock, Microsoft and others will be all too happy to take their business by offering a wealth of devices that allow you to tinker to your heart's content. We should let such experiments continue and let the future of the Internet be determined by market choices, not regulatory choices such as forced API neutrality.

I think the same critique would apply to efforts to impose API neutrality on Twitter. But before going into more detail, we need to first ask another question: Does Twitter possess "market power" such that their actions warrant antitrust or regulatory scrutiny at all?

But Isn't Twitter a "Monopoly"?

Savvy readers will recall that influential Columbia Law School cyberlaw professor Tim Wu has already labeled Twitter a "monopoly," although he has not yet bothered telling us what the relevant market is here. As I pointed out in an essay critiquing the way Prof. Wu flippantly assigns the label "monopoly" to just about any big tech provider, it's very much unclear what to call the market Twitter serves. After all, the service is only a few years old and competes with many other forms of communication and information dissemination. For me, Twitter is a partial substitute for blogging, IMs, email, phone calls, and my RSS feed. Yet, like most others, I continue to use all those other technologies and those technologies continue to pressure Twitter to innovate.

Regardless, Prof. Wu is now in a position to put his ideas into action since he is currently serving a short tenure as special advisor to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Might he act on his instincts, therefore, and advise the agency to take action against Twitter? It is unlikely that Prof Wu will be around the FTC long enough to help them bring any sort of formal action against Twitter, but he could help lay the groundwork for a creative interpretation of our nation's antitrust laws such that Twitter somehow comes to be labeled a "monopoly" or what he refers to as an "information empire" in his new book The Master Switch. (See my last review of the book here.)

But I think he'd have a very hard time convincing the folks in the FTC's Economics Bureau that Twitter is really worth worrying about or that it has anything approximating a "monopoly" in this emerging market, whatever that market is. But Wu has the ear of key people in government right now and could be lobbying for more expansive constructions of "information monopoly" since he made it very clear in his book that traditional antitrust analysis was not sufficient for information sectors. "[I]nformation industries… can never be properly understood as 'normal' industries," Wu claimed, and even traditional forms of regulation, including antitrust, "are clearly inadequate for the regulation of information industries," he says. (p. 303)

The Principle of the Matter

So here's my take on the issue. Twitter is an amazing innovator. It created the space it now plays in and that market is still so new and unique that we don't even have a name for it yet. It America, we should – and usually do – celebrate such entrepreneurialism. But sometimes certain Ivory Tower elites, regulatory-minded advocates, paternalistic policymakers, or even disgruntled competitors, claim that such innovators "owe" the rest of us something because they got rich or powerful thanks to that innovation. "Forced access" or "neutrality" mandates becomes a convenient regulatory prescription to achieve that end even though the motivating principle behind such regulation is, essentially, "what's yours is mine."

Indeed, from my perspective the entire notion of forced access to the Twitter API could be dismissed by noting that, technically speaking, Twitter's API is its private property and they should be free to do as they wish with it. That's why I'm particularly concerned with Zittrain's notion that we might consider applying adverse possession principles to any digital platform with enough users; at root, it's a call to limit or even abolish property rights for digital platforms once they gain popularity or have a large number of users. As noted below, that has extremely dangerous ramifications for digital innovation but, more profoundly in my opinion, it is an unjust and unconstitutional taking of an innovator's property. Of course, I understand that property rights aren't exactly in vogue in America anymore and that this isn't really a satisfying answer from the consumer's perspective, so let's continue on and consider a few other reasons why forced access regulation of Twitter via API neutrality would be a mistake.

First, we should not forget that Twitter has yet to find a way to turn its service into a serious revenue-generator. The most obvious reason for that is that Twitter (a) doesn't charge anything for the service it provides and (b) doesn't lock down its platform / API such that they might be able to earn a return on their investment by monetizing eyeballs via advertising on their own platform. That's why Twitter's announcement on Friday won't come to a shock to anyone with a whiff of business sense in their heads. At some point, Twitter probably had to do something like this if they wanted to find a way to monetize and grow their business.

I can hear some out there screaming out "but it's not fair!" as if there was cosmic sense of cyber-justice that has been betrayed because Twitter had the audacity to lock-down their platform. Of course, it is certainly true that some third-party app providers may suffer because of Twitter's move here. I'm not going to lie to you; if Twitter's move to exert greater control over its API somehow destroys the beauty that is the TweetDeck desktop interface, I am going to be screaming mad myself! I do not think there has ever been a slicker, more user-friendly interface for any web service in Internet history than what TweetDeck offers consumers. For my money – which means nothing since TweetDeck is free! – TweetDeck is digital perfection defined. And, incidentally, I'd be happy to pay for it if they asked.

But despite my gushing love for it, let's be clear about something: TweetDeck has no inherent right to exist. Indeed, TweetDeck owes its very existence to the fact that Twitter offered its API to the world on a completely free, unlicensed, unrestricted basis. The same holds true for all those other third-party platforms that depend upon the Twitter API. What Twitter giveth, Twitter can taketh away.

Stated differently, Twitter has thus far had a voluntary open access policy in place for the first few years of its existence but now wants to partially abandon that policy. This policy reversal will, no doubt, lead to claims that the company is acting like one of Wu's proverbial "information empires" and that perhaps Zittrain's API neutrality regime should be put in place as a remedy. Indeed, Zittrain has already referred to it as a "bait-and-switch" and cited back to the provisions of his book that I outlined above. I believe that foreshadows what's to come: more pressure from the Ivory Tower and then, potentially, from public policy makers that will first encourage and then push to force Twitter to grant access to its platform on terms set by others. It's a potential first step toward the forced commoditization of the Twitter API and the involuntary surrender of its property rights to some collective authority who will manage it as a "collective good," "common carrier," or "essential facility."

But Consider This… (on API Neutrality and Disincentives)

Of course, the people at Twitter certain realize how important all those third-party apps and platforms have been to growing the Twitter information empire. Thus, an overly-zealous move to crush third parities by denying them the API or any incidental use of the Twitter name / branding could backfire in two ways: it could lead to a major consumer backlash which in turn spurs the development of alternative platforms and entirely new types of competing services.

Vertical integration might be one way to partially alleviate those problems. Twitter could start cutting deals with existing third-party platforms that rely upon its API such that they were brought under the Twitter corporate umbrella, where more standardization could occur. But Twitter doesn't have the money to buy them all out. Moreover, Twitter doesn't want to see dozens of interfaces under its corporate umbrella. For them, this is about "a consistent user experience." In other words, they'd obviously prefer a more standardized platform / interface that simply got rid of some of those third-party apps and platforms altogether.

As a result, in the short term, I think we'll likely end up with a market dominated by Twitter's proprietary platform(s) but with a couple of other leading existing third-party providers being tolerated by the company so as not to rock the boat too much. And that's not a bad thing. Here's the key principle to keep in mind: If we apply API neutrality or adverse possession principles forcibly, it sends a horrible signal to entrepreneurs that basically says their platforms are theirs in name only and will be forcibly commoditized once they are popular enough. That's a horrible disincentive to future innovation and investment. However, it means we must sometimes tolerate short term spells of "market power" when we allow entrepreneurs to realize the benefits of their past innovations and investments if we hope to get more of them in the future.

Avoiding Static Snapshots

But wait, you say, isn't this all quite horrible for the consumers and competition? Isn't this just Wu's "information empire" fear manifesting itself such that antitrust or API neutrality really is required?

Here's where those warring conceptions of "Internet freedom" come into play. As I've noted here many times before in my work on the "conflict of visions" about Internet freedom today, it is during what some might regard as a market's darkest hour when some of the most exciting disruptive technologies and innovations develop. People don't sit still; they respond to incentives, including short spells of apparently excessive private power.

By contrast, the "static snapshot" crowd gets so worked up about short term spells of "market power" – which usually don't represent serious market power at all – that they call for the reordering of markets to suit their tastes. Sadly, they sometimes do this under the banner of "Internet freedom," claiming that we can "free" consumers from the supposed tyranny of the marketplace. In reality, that vision wraps markets in chains and ultimately leaves consumers worse off by stifling innovation and inviting in ham-handed regulatory edits and bureaucracies to plan this fast-paced sector of our economy.

"Splitting the Root"

And innovation is possible. Is it really that unthinkable that a Twitter competitor might come along? In a sense, TweetDeck shows the way forward. TweetDeck has already bucked Twitter's 140-character limit by offering "Deck.ly," an exclusive service that allows TweetDeck users to type Twitter messages longer than 140 characters, but which will only be visible via TweetDeck platforms. What if TweetDeck took the next bold step and offered an entirely separate API in direct competition to Twitter? It would be the tweeting equivalent of "splitting the root," to borrow a concept from the domain name space.

Some would decry the potential lack of interoperability at first. But I bet some sharp folks out there would quickly find work-arounds. Has everyone forgotten the hand-wringing that took place over instant message interoperability just a decade ago (and the resulting restrictions placed on the company following its merger with Time Warner)? Big bad AOL was going to eat everyone's lunch in the IM space, don't you remember? But all the hand-wringing about AOL's looming monopolization of instant messaging seems particularly silly now since anyone can download a free chat client like Digsby or Adium to manage IM services from AOL, Yahoo!, Google, Facebook and just about anyone else, all within a single interface — essentially making it irrelevant which chat service your friends use.

Again, people respond to incentives, and sometimes it takes bone-headed moves by market leaders to really get people off their butts and motivate them to code work-arounds and superior solutions. Is it so hard to imagine that a similar response might follow Twitter's move this week? After all, we are not talking about replicating a massive physical network of pipes or towers here. We are talking about pure code, for God's sake! Competition to Twitter is more than possible and it's likely to come from sources and platforms we cannot currently imagine (just as few of us could have imagined something like Twitter developing just five years ago).

Conclusion

So, Twitter's move is not an end but rather a new beginning. Personally, I think it could spawn another amazing round of innovation in this space. Again, we must not forget that we are dealing with a space that is still so new that we do not know what to call it. For that reason alone, we should be skeptical of calls for a preemptive regulatory strike. We need to have a little faith in the entrepreneurial spirit and the dynamic nature of markets built upon code, which have the uncanny ability to morph and upend themselves seemingly every few years. In the short term, Twitter will continue to possess a dominant position in whatever we call this market that it serves. But the short term is just that; it's not the end of the story.

Now excuse me while I get back to Tweeting!

March 10, 2011

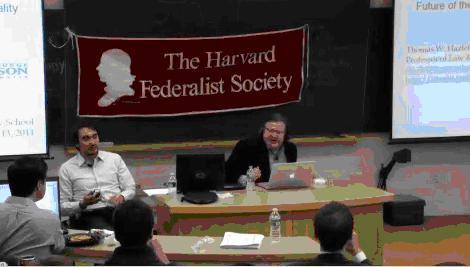

Hazlett vs. Wu on Net Neutrality

With all the attention on net neutrality this week, I thought I'd bring your attention to a debate on the-issue-that-won't-go-away between Tom Hazlett and Tim Wu, which took place earlier this year at Harvard Univerisity. Below is the MP3 audio of the event, but if you want to check it out in living color, check out the video at the Information Economy Project wabsite.

Hazlett vs. Wu Net Neutrality Debate – Jan. 2011

Questions for the FTC & DoC at Next Privacy Hearing

Yet another hearing on privacy issues has been slated for this coming Wednesday, March 16th. This latest one is in the Senate Commerce Committee and it is entitled "The State of Online Consumer Privacy." As I'm often asked by various House and Senate committee staffers to help think of good questions for witnesses, I'm listing a few here that I would love to hear answered by any Federal Trade Commission (FTC) or Dept. of Commerce (DoC) officials testifying. You will recall that both agencies released new privacy "frameworks" late last year and seem determined to move America toward a more "European-ized" conception of privacy regulation. [See our recent posts critiquing the reports here.] Here are a few questions that should be put to the FTC and DoC officials, or those who support the direction they are taking us. Please feel free to suggest others:

Before implying that we are experiencing market failure, why hasn't either the FTC or DoC conducted a thorough review of online privacy policies to evaluate how well organizational actions match up with promises made in those policies?

To the extent any sort of internal cost-benefit analysis was done internally before the release of these reports, has an effort been made to quantify the potential size of the hidden "privacy tax" that new regulations like "Do Not Track" could impose on the market?

Has the impact of new regulations on small competitors or new entrants in the field been considered? Has any attempt been made to quantify how much less entry / innovation would occur as a result of such regulation?

Were any economists from the FTC's Economics Bureau consulted before the new framework was released? Did the DoC consult any economists?

Why do FTC and DoC officials believe that citing unscientific public opinions polls from regulatory advocacy organizations serves as a surrogate for serious cost-benefit analysis or an investigation into how well privacy policies actual work in the marketplace?

If they refuse to conduct more comprehensive internal research, have the agencies considered contracting with external economists to build a body of research looking into these issues? (as the Federal Communications Commission did in a decade ago in its media ownership proceeding.)

Good News! Online Tracking is Slightly Boring

You have to wade through a lot to reach the good news at the end of Time reporter Joel Stein's article about "data mining"—or at least data collection and use—in the online world. There's some fog right there: what he calls "data mining" is actually ordinary one-to-one correlation of bits of information, not mining historical data to generate patterns that are predictive of present-day behavior. (See my data mining paper with Jeff Jonas to learn more.) There is some data mining in and among the online advertising industry's use of the data consumers emit online, of course.

Next, get over Stein's introductory language about the "vast amount of data that's being collected both online and off by companies in stealth." That's some kind of stealth if a reporter can write a thorough and informative article in Time magazine about it. Does the moon rise "in stealth" if you haven't gone outside at night and looked at the sky? Perhaps so.

Now take a hard swallow as you read about Senator John Kerry's (D-Mass.) plans for government regulation of the information economy.

Kerry is about to introduce a bill that would require companies to make sure all the stuff they know about you is secured from hackers and to let you inspect everything they have on you, correct any mistakes and opt out of being tracked. He is doing this because, he argues, "There's no code of conduct. There's no standard. There's nothing that safeguards privacy and establishes rules of the road."

Securing data from hackers and letting people correct mistakes in data about them are kind of equally opposite things. If you're going to make data about people available to them, you're going to create opportunities for other people—it won't even take hacking skills, really—to impersonate them, gather private data, and scramble data sets.

If Senator Kerry's argument for government regulation is that there aren't yet "rules of the road" pointing us off that cliff, I'll take market regulation. Drivers like you and me are constantly and spontaneously writing the rules through our actions and inactions, clicks and non-clicks, purchases and non-purchases.

There are other quibbles. "Your political donations, home value and address have always been public," says Stein, "but you used to have to actually go to all these different places — courthouses, libraries, property-tax assessors' offices — and request documents."

This is correct insofar as it describes the modern decline in practical obscurity. But your political donations were not public records before the passage of the Federal Election Campaign Act in 1974. That's when the federal government started subordinating this particular dimension of your privacy to others' collective values.

But these pesky details can be put aside. The nuggets of wisdom in the article predominate!

"Since targeted ads are so much more effective than nontargeted ones," Stein writes, "websites can charge much more for them. This is why — compared with the old banners and pop-ups — online ads have become smaller and less invasive, and why websites have been able to provide better content and still be free."

The Internet is a richer, more congenial place because of ads targeted for relevance.

And the conclusion of the article is a dose of smart, well-placed optimism that contrasts with Senator Kerry's sloppy FUD.

We're quickly figuring out how to navigate our trail of data — don't say anything private on a Facebook wall, keep your secrets out of e-mail, use cash for illicit purchases. The vast majority of it, though, is worthless to us and a pretty good exchange for frequent-flier miles, better search results, a fast system to qualify for credit, finding out if our babysitter has a criminal record and ads we find more useful than annoying. Especially because no human being ever reads your files. As I learned by trying to find out all my data, we're not all that interesting.

Consumers are learning how to navigate the online environment. They are not menaced or harmed by online tracking. Indeed, commercial tracking is congenial and slightly boring. That's good news that you rarely hear from media or politicians because good news doesn't generally sell magazines or legislation.

March 9, 2011

Is Digital Utopianism Dead? And Other Questions

What I hoped would be a short blog post to accompany the video from Geoff Manne and my appearances this week on PBS's "Ideas in Action with Jim Glassman" turned out to be a very long article which I've published over at Forbes.com.

I apologize to Geoff for taking an innocent comment he made on the broadcast completely out of context, and to everyone else who chooses to read 2,000 words I've written in response.

So all I'll say here is that Geoff Manne and I taped the program in January, as part of the launch of TechFreedom and of "The Next Digital Decade." Enjoy!

"Privacy" as Censorship: Fleischer Dismantles the EU's "Right to Forget"

Few people have experienced just how oppressive "privacy" regulation can be quite so directly as Peter Fleischer, Google's Global Privacy Counsel. Early last year, Peter was convicted by an Italian court because Italian teenagers used Google Video to host a video they shot of bullying a an autistic kid—even though he didn't know about the video until after Google took it down.

Of course, imposing criminal liability on corporate officers for failing to take down user-generated content is just a more extreme form of the more popular concept of holding online intermediaries liable for failing to take down content that is allegedly defamatory, bullying, invasive of a user's privacy, etc. Both have the same consequence: Given the incredible difficulty of evaluating such complaints, sites that host UGC will tend simply to take it down upon receiving complaints—thus being forced to censor their own users.

Now Peter has turned his withering analysis on the muddle that is Europe's popular "Right to be Forgotten." Adam noted the inherent conflict between that supposed "right" and our core values of free speech. It's exactly the kind of thing UCLA Law Prof. Eugene Volokh had in mind when he asked what is your "right to privacy" but a right to stop me from observing you and speaking about you?" Peter hits the nail on the head:

More and more, privacy is being used to justify censorship. In a sense, privacy depends on keeping some things private, in other words, hidden, restricted, or deleted. And in a world where ever more content is coming online, and where ever more content is find-able and share-able, it's also natural that the privacy counter-movement is gathering strength. Privacy is the new black in censorship fashions. It used to be that people would invoke libel or defamation to justify censorship about things that hurt their reputations. But invoking libel or defamation requires that the speech not be true. Privacy is far more elastic, because privacy claims can be made on speech that is true.

He breaks down eight problems with this fake "right," but the third is most on point:

If someone else posts something about me, should I have a right to delete it? Virtually all of us would agree that this raises difficult issues of conflict between freedom of expression and privacy. Traditional law has mechanisms, like defamation and libel law, to allow a person to seek redress against someone who publishes untrue information about him. Granted, the mechanisms are time-consuming and expensive, but the legal standards are long-standing and fairly clear. But a privacy claim is not based on untruth. I cannot see how such a right could be introduced without severely infringing on freedom of speech. This is why I think privacy is the new black in censorship fashion.

Amen, brother. I wish more "privacy advocates" would think more carefully about the tension between their absolutist privacy stances and their loyalties to America's free speech tradition.

But I won't hold my breath.

Book Review: Siva Vaidhyanathan's "Googlization of Everything"

In one sense, Siva Vaidhyanathan's new book, The Googlization of Everything (And Why Should Worry), is exactly what you would expect: an anti-Google screed that predicts a veritable techno-apocalypse will befall us unless we do something to deal with this company that supposedly "rules like Caesar." (p. xi) Employing the requisite amount of panic-inducing Chicken Little rhetoric apparently required to sell books these days, Vaidhyanathan tells us that "the stakes could not be higher," (p. 7) because the "corporate lockdown of culture and technology" (p. xii) is imminent.

In one sense, Siva Vaidhyanathan's new book, The Googlization of Everything (And Why Should Worry), is exactly what you would expect: an anti-Google screed that predicts a veritable techno-apocalypse will befall us unless we do something to deal with this company that supposedly "rules like Caesar." (p. xi) Employing the requisite amount of panic-inducing Chicken Little rhetoric apparently required to sell books these days, Vaidhyanathan tells us that "the stakes could not be higher," (p. 7) because the "corporate lockdown of culture and technology" (p. xii) is imminent.

After lambasting the company in a breathless fury over the opening 15 pages of the book, Vaidhyanathan assures us that "nothing about this means that Google's rule is as brutal and dictatorial as Caesar's. Nor does it mean that we should plot an assassination," he says. Well, that's a relief! Yet, he continues on to argue that Google is sufficiently dangerous that "we should influence—even regulate—search systems actively and intentionally, and thus take responsibility for how the Web delivers knowledge." (p. xii) Why should we do that? Basically, Google is just too damn good at what it does. The company has the audacity to give consumers exactly what they want! "Faith in Google is dangerous because it increases our appetite for goods, services, information, amusement, distraction, and efficiency." (p. 55) That is problematic, Vaidhyanathan says, because "providing immediate gratification draped in a cloak of corporate benevolence is bad faith." (p. 55) But this begs the question: What limiting principle should be put in place to curb our appetites, and who or what should enforce it?

We're All Just Sheep Being Fed the Illusion of Choice

This gets to Vaidhyanathan's broader mission in Googlization. His book goes well beyond simply Google-bashing and serves as a fusillade against what he considers really "harmful or dangerous" which is "blind faith in technology and market fundamentalism" (p. xiii) Unsurprisingly, a classic Marxist false consciousness narrative is at work throughout the book. Vaidhyanathan speaks repeatedly of consumer "blindness" to "false idols and empty promises." In his chapter on "the Googlization of Us," for example, consumers are viewed largely as ignorant sheep being led to the cyber-slaughter, tricked by the "smokescreen" of "free" online services and "freedom of choice." (p. 83)

Indeed, even though he admits that no one forces us to use Google and that consumers are also able to opt-out of most of its services or data collection practices, Vaidhyanathan argues that "such choices mean very little" because "the design of the system rigs it in favor of the interests of the company and against the interests of users." (p. 84) But, again, he says this is not just a Google problem. The whole damn digital bourgeois class of modern tech capitalists is out to sedate us using the false hope of consumer choice. "Celebrating freedom and user autonomy is one of the great rhetorical ploys of the global information economy," Vaidhyanathan says. "We are conditioned to believe that having more choices—empty through they may be—is the very essence of human freedom. But meaningful freedom implies real control over the conditions of one's life."(p. 89, emphasis added)

Vaidhyanathan doesn't really connect the dots to tell us how Google or any of the other evil capitalist overlords have supposedly conspired to take away such "real control" over the conditions of our lives. Instead, he just implies that any "choice" they offer us are "false," "empty," or "irrelevant" choices and that he and other elites can help us see through the web of lies (excuse the pun) and chart a better course.

By the end of chapter 3, Vaidhyanathan cuts loose and tells us exactly what he thinks of the faculties of his fellow humans. It's one of the most shocking and insulting paragraphs I have read in any book in recent memory. I've offered a little color commentary in the bracketed italics below imagining a different way of expressing what Vaidhyanathan is really saying here:

"Living so long under the dominance of market fundamentalism and techno-fundamentalism, we have come to accept the concept of choice [Choice is overrated, you see] and the exhortation of both the Isley Brothers and Madonna, "Express Yourself," as essential to living a good life. [We can't have people freely expressing themselves, now can we?!] So comforted are we by offers of "options" and "settings" made by commercial systems such as Facebook and Google that we neglect the larger issues. [Again, you people are all just mindless sheep who are easily confused and seduced by "options" and "settings"] We weave these services so firmly and quickly into the fabrics of our daily social and intellectual lives that we neglect to consider what dependence might cost us. [All these free "options" are killing us] And many of us who are technically sophisticated can tread confidentially through the hazards of these systems [me and my Ivory Tower elite buddies are sagacious and see through the lies…], forgetting that the vast majority of people using them are not aware of their pitfalls or the techniques by which users can master them. [… but the rest of you are just dumb as dirt.] Settings only help you if you know enough to care about them. [I'm serious, you common folk are really ignorant.] Defaults matter all the time. Google's great trick [again, you're being brainwashed; allow me to show you the light] is to make everyone feel satisfied with the possibility of choice [Have I told you about Marxist false consciousness theory yet?], without actually exercising it to change the system's default settings." (p. 113-4)

How utterly condescending. Sadly, such elitist "people-are-sheep" thinking is all too common in many recent books about the Internet's impact on society. See my reviews of recent books by Andrew Keen, Mark Helprin, Lee Siegel and even to some extent Jaron Lanier. For more discussion and a critique of this thinking, see my recent book chapter, "The Case for Internet Optimism, Part 1: Saving the Net from Its Detractors." Simply stated, these critics simply don't give humanity enough credit and they utterly fail to recognize how humans excel at adapting to change.

The One True Way & The Royal "We"

Regardless, what does Vaidhyanathan want to do to improve the lives of the cyber-sheep since they obviously don't know how to look out for themselves? In essence, he wants a precautionary principle for technological progress. He believes progress must be carefully planned to ensure that (a) no harms come from it and, (b) that all benefit equally from its riches when it occurs. More specifically, progress needs to be centrally planned through a political process so that we have more of a say about the future. (More on that royal "we" in a moment.)

Vaidhyanathan bemoans what he calls "public failure" by which he means the absence of political solutions or an over-arching "authority" that sets us on a more enlightened path. "There was never any election to determine the Web's rulers," he says. "No state appointed Google its proxy, its proconsul, or its viceroy. Google just stepped into the void when no other authority was willing or able to make the Web stable, usable, and trustworthy." (p. 23)

But should there have been an "election to determine the Web's rulers"? And who is this "other authority" that should have "stepped into the void" and made the Web more "stable, usable, and trustworthy"? Like so many other would-be cyber-planners, Vaidhyanathan never details what better plan could have saved us from the supposedly tyranny of the marketplace. We're simply told that someone or something could have done it better. Web search could have been better. Digitized book archiving could have been done better. Online news could have been done better. And so on.

Because Google has touched each of these areas, Vaidhyanathan makes the company his scapegoat for all that is supposedly wrong in the modern digital world. But the "Googlization" of which he speaks transcends one company and refers more generally to any and all private, market-based responses to the challenges of the Information Age. Again, it is the fact that such market processes are so messy and uneven that has Vaidhyanathan so incensed. How could we — and his royal we inevitably refers to the political or academic elites who supposedly should have been looking out for us — have allowed this process to unfold without a more sensible plan?

The Centralization of Everything (And Why We Should Worry)

In terms of longer-term solutions, Vaidhyanathan doesn't shy away from using a term that most other critics shy away from: centralization. Although he is short on details about whom the technocratic vanguard will be that will lead the effort to take back the reins of power, he's at least got a name for it and plan of action. Vaidhyanathan calls for the creation of "The Human Knowledge Project" to "identify a series of policy challenges, infrastructure needs, philosophical insights, and technological challenges with a single realizable goal in mind: to organize the world's information and make it universally accessible." (p. 204-5)

Why do we need such a Politburo Project when countless other entities, including Google, are working spontaneously to accomplish the same goal through diffuse efforts? Because, Vaidhyanathan says, "it's better to have these things argued in a deliberative forum than decided according to the whims of market forces, technological imperatives, and secretive contracts." (p. 205) But Vaidhyanathan's call for a centralized vision and plan of action also comes down to his fundamental distrust of market processes in knowledge and his over-arching faith in the wisdom of the technocratic elite to chart a more sensible path forward. "It's more important to do it right than to do it fast. It's more important to have knowledge sources that will work one hundred years from now than to have a collection of poor images that we can see next week." (p. 204)

From these statements we can obviously deduce that Vaidhyanathan doesn't much believe in the power of markets, but it's equally clear he doesn't really seem to understand them. Markets are simply learning and discovery processes. They are ongoing experiments. And experiments can be messy. They can be turbulent. They can be uneven. But the process of experimentation and discovery has valuable benefits that cannot be centrally planned or divined by a technocratic elite preemptively.

Vaidhyanathan doesn't like that fact very much. He is a believer in the proverbial "better path" or One True Way. Yet, when Vaidhyanathan says "it's more important to do it right," the operational assumption is that we already know what "it" is and how to do it "right." And when he suggests "it's more important to have knowledge sources that will work one hundred years from now," it suggest that somewhere out there a more enlightened path exists and that he and some other elites in the Human Knowledge Project apparently possess a map to guide us to it.

This is the height of hubris. There is no way in hell any of us could know which "knowledge sources" will work one hundred years from now or even 10 years from now, for that matter. That is precisely where markets come in. Organic, bottom-up, unplanned experimentation is valuable precisely because of the limitations of human knowledge and planning. Wikipedia, for example, isn't the product a highly planned, centralized vision set forth by some massive information bureaucracy. I doubt a "Human Knowledge Project" could have designed such a thing from scratch 10 years ago. Instead, they would have likely started with Encyclopedia Britannica and Encarta as models and then spent billions trying to figure out how to make them better.

Worse yet, Vaidhyanathan treats technological progress as a zero-sum game. He says, for example, that "it's more important to link poor children in underdeveloped regions with knowledge than to quicken the pace of access for those of us who already live among more information than we could possibly use." (p. 204) Substitute the word "money" for "knowledge/information" in the above passage and you'll discover the typical zero-sum thinking behind much global development thinking today. The traditional reasoning: Some of us are lucky enough to have money or resources and that means we must be depriving others of them. That's faulty logic, of course. Simply because one region or economy prospers it does not mean others must suffer. The same goes for information policy. We can do more to aid the poor and unconnected in underdeveloped regions without depriving information-rich countries and peoples the benefits of more and better services. After all, who is Vaidhyanathan to say that we already have "more information than we could possibly use"? Is there a meter running on how much information is too much for us?

The Unconstrained Vision, Once Again

The scope of centralized planning that Vaidhyanathan envisions the Human Knowledge Project undertaking is ambitious to say the least. In the abstract, he says: "The post-Google agenda of the Human Knowledge Project would be committed to outlining the values and processes necessary to establish and preserve a truly universal, fundamentally democratic global knowledge ecosystem and public sphere." (p. 206) More concretely:

"The Human Knowledge Project would consider questions of organization and distribution at every level: the network, the hardware, the software, the protocols, the laws, the staff, the administrators, the physical space (libraries), the formats for discrete works, the formats for reference works such as dictionaries and encyclopedias, the formats for emerging collaborative works, and the spaces to facilitate collaboration and creativity." (p. 206-7)

Needless to say, there isn't much that this veritable Ministry of Information wouldn't be considering or planning. Vaidhyanathan repeats, however, that it would constitute "public failure" if we failed to institute such a plan for the future.

Of course, there's another definition of "public failure" that Vaidhyanathan never bothers considering. It's the "public failure" identified by public choice economists and political scientists who have meticulously documented the myriad ways in which politics and political processes fail to achieve the idealistic "public interest" goals of set forth by Ivory Tower elites. For example, Vaidhyanathan never bothers considering how expanded the horizons of state power in the ways he wishes might become an open invitation for even more of the corporate shenanigans he despises. After all, history teaches us that regulatory capture is all too real.

But Vaidhyanathan doesn't have much time for such meddlesome details. He's too busy trying to save the world. Vaidhyanathan is a near perfect exponent of what political scientist Thomas Sowell once labeled "the unconstrained vision." A long line of thinkers—Plato, Rousseau, Voltaire, Robert Owen, John Kenneth Galbraith, John Dewey, John Rawls—have argued that man is inherently unconstrained and that society is perfectible; it's just a matter of trying hard enough. In this vision, passion for, and pursuit of, noble ideals trumps all. Human reason has boundless potential.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, this crowd believes that order and justice derives from smart planning, often from the top-down. Elites are expected to make smart social and economic interventions to serve some amorphous "public interest." Smart solutions and good intentions matter most and there's little concern about costs or unintended consequences of political action. Finally, desired outcomes are pre-scripted and distributive or "patterned" justice is key. Because markets cannot ensure the precise results they desire, they must be superseded by centralized planning and patterned, equal outcomes.

Of course, back in the real world, the rank hubris of the unconstrained mindset conflicts violently with economic and cultural realities at every juncture. As Friedrich von Hayek taught us long ago, "To act on the belief that we possess the knowledge and the power which enable us to shape the processes of society entirely to our liking, knowledge which in fact we do not possess, is likely to make us do much harm." It's a lesson that many countries and cultures have learned at great expense, but one that utopians like Vaidhyanathan still ignore.

More generally, Vaidhyanathan is trapped in what Virginia Postrel labeled the "stasis mentality" in her 1998 book The Future and Its Enemies. The stasis crowd is prone to take short-term snapshots of the world around us at any given time and extrapolate only the worst from it. "It overvalues the tastes of an articulate elite, compares the real world of trade-offs to fantasies of utopia, omits important details and connections, and confuses temporary growing pains with permanent catastrophes," Postrel noted. This mindset is precisely what economist Israel Kirzner had in mind when warned in of "the shortsightedness of those who, not recognizing the open-ended character of entrepreneurial discovery, repeatedly fall into the trap of forecasting the future against the background of today's expectations rather than against the unknowable background of tomorrow's discoveries."

This insidious, short-sighted, overly pessimistic worldview is contradicted at almost every juncture today by the fact that—at least technologically speaking—things are getting better all the time. There's never been a period in human history when we've had access to more technology, more information, more services, more of just about everything. While we humans have wallowed in information poverty for the vast majority of our existence, we now live in a world of unprecedented information abundance and cultural richness.

Critics like Siva Vaidhyanathan will, no doubt, persist in their claims that there is "a better path," but the path we're on right now isn't looking so bad and does not require the radical prescriptions he and others call for. Moreover, the alternative vision doesn't begin with the insulting presumption that humans are basically just mindless sheep who can't look out for themselves.

________

[To hear Vaidhyanathan in his own words, check out his Surprisingly Free podcast conversation with Jerry Brito this week as well as the webpage for his book.]

March 8, 2011

Siva Vaidhyanathan on why we should worry about Google

On the podcast this week, Siva Vaidhyanathan, professor of media studies at the University of Virginia, discusses his new book, The Googlization of Everything: (And Why We Should Worry). Vaidhyanathan talks about why he thinks many people have "blind faith" in Google, why we should worry about it, and why he doesn't think it's likely that a genuine Google competitor will emerge. He also discusses potential roles of government, calling search neutrality a "nonstarter," but proposing the idea of a commission to monitor online search. He also talks about a "Human Knowledge Project," an idea for a global digital library, and why a potential monopoly on information by such a project doesn't worry him the way that Google does.

Related Links

"The Googlization of Everything: How one company is disrupting commerce, culture, and community," Vaidhyanathan's blog about the book

The Googlization of Everything, Chapter 1

"Google's Gadfly," Inside Higher Ed

"Google Violates its Don't Be Evil Motto," debate over whether Google violates its motto

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

March 7, 2011

Targeted Advertising for Cable TV & Skype

We've said it here before too may times to count: When it comes to the future of content and services — especially online or digitally-delivered content and services — there is no free lunch. Something has to pay for all that stuff and increasingly that something is advertising. But not just any type of advertising — targeted advertising is the future. We see that again today with Skype's announcement that it is rolling out an advertising scheme as well as in this Wall Street Journal story ("TV's Next Wave: Tuning In to You") about how cable and satellite TV providers are ramping up their targeted advertising efforts.

No doubt, we'll soon hear the same old complaints and fears trotted out about these developments. We'll hear about how "annoying" such ads are or how "creepy" they are. Yet, few will bother detailing what the actual harm is in being delivered more tailored or targeted commercial messages. After all, there's actually a benefit to receiving ads that may be of more interest to us. Much traditional advertising was quite "spammy" in that it was sent to the mass market without a care in the world about who might see or hear it. But in a diverse society, it would be optimal if the ads you saw better reflected your actual interests / tastes. And that's a primary motivation for why so many content and service providers are turning to ad targeting techniques. As Skype noted in its announcement today: "We may use non-personally identifiable demographic data (e.g. location, gender and age) to target ads, which helps ensure that you see relevant ads. For example, if you're in the US, we don't want to show you ads for a product that is only available in the UK." Similarly, the Journal article highlights a variety of approaches that television providers are using to better tailor ads to their viewers.

Some will still claim it's too "creepy." But, as I noted in my recent filing to the Federal Trade Commission on its new privacy green paper:

If harm is reduced to "creepiness" or even "annoyance" and "unwanted solicitations" as some advocate, it raises the question whether the commercial Internet as we know it can continue to exist. Such an amorphous standard leaves much to the imagination and opens the door to creative theories of harm that are sure to be exploited. In such a regime, harm becomes highly conjectural instead of concrete. This makes credible cost-benefit analysis virtually impossible since the debate becomes purely about emotion instead of anything empirical. …

Importantly, nothing in the Commission's proceeding has thus far demonstrated that online data collection and "tracking" represent a clear harm to consumers per se, or that any "market failure" exists here. Such a showing would be difficult since using data to deliver more tailored advertising to consumers can provide important benefits to the public..

I've already noted one possible benefit to consumers: ads that are more relevant to them and, therefore, potentially less "annoying." But the far more important benefits would be (1) keeping costs for content and services reasonable, and/or (2) just keeping that content flowing or those services in business. I go into more detail about both of these potential benefits in my FTC filing, but the reasoning here is pretty straightforward. Again, advertising is the great subsidizer of the press, media, content, and online services. The reason we already have access to some much great content and so many great (and often free) online services is because of advertising.

But the market for content and services is becoming more cut-throat competitive every day. There's simply so much stuff to choose from that both the content/service providers and the advertisers are being forced to evolve and change their business models. Locking them into to yesterday's (or even today's) advertising and marketing methods limits their ability to respond to competitive pressures and concoct more innovate models going forward. Targeting will clearly be part of the mix, and if it can help companies continue to provide their content and services to the public — or, better yet, provide them at a more competitive price — then policymakers must take those potential benefits into account when considering privacy regulations, even if some feel such ads are "creepy." Again, it's unclear how "creepiness" is a harm and, even if it is, it has to be stacked against the many potential benefits or more targeted forms of advertising. There's no guarantee those methods will succeed, of course, but they should at least be given a chance.

Again, read my FTC comments for more detail. And let's say it once more, with feeling: There is no free lunch!

March 4, 2011

What is Market Failure? And What if There is One?

Twitter curmudgeon @derekahunter writes: "With all the medical advances of last 100 years, why hasn't anyone created a cough drop that doesn't taste like crap?" Dammit, he's right! Why hasn't the market for cold remedies produced a tasty cough drop? Put differently, the market for cold remedies has failed to produce a tasty cough drop. The market has failed. Market . . . failure.

We have now established the appropriateness of a regulatory solution for the taste problem in the field of cold remedies. Have we not? There is a market failure.

No, we haven't.

"Market failure" is not what happens when a given market has failed so far to reach outcomes that a smart person would prefer. It occurs when the rules, signals, and sanctions in and around a given marketplace would cause preference- and profit-maximizing actors to reach a sub-optimal outcome. You can't show that there's a market failure by arguing that the current state of the actual market is non-ideal. You have to show that the rules around that marketplace lead to non-ideal outcomes. The bad taste of cough drops is not evidence of market failure.

The failure of property rights to account for environmental values leads to market failure. A coal-fired electric plant might belch smoke into the air, giving everyone downwind a bad day and a shorter life. If the company and its customers don't have to pay the costs of that, they're going to over-produce and over-consume electricity at the expense of the electric plant's downwind neighbors. The result is sub-optimal allocation of goods, with one set of actors living high on the hog and another unhappily coughing and wheezing.

Take an issue that's closer to home for tech policy folk: People seem to underweight their privacy when they go online, promiscuously sharing anything and everything on Facebook, Twitter, and everyplace else. Marketers are hoovering up this data and using it to sell things to people. The data is at risk of being exposed to government snoops. People should be more attentive to privacy. They're not thinking about long-term consequences. Isn't this a market failure?

It's not. It's consumers' preferences not matching up with the risks and concerns that people like me and my colleagues in the privacy community share. Consumers are preference-maximizing—but we don't like their preferences! That is not a market failure. Our job is to educate people about the consequences of their online behavior, to change the public's preferences. That's a tough slog, but it's the only way to get privacy in the context of maximizing consumer welfare.

If you still think there's a market failure in this area—I readily admit that I'm on the far edge of my expertise with complex economic concepts like this—you haven't finished making your case for regulation. You need to show that the rules, signals, and sanctions in and around the regulatory arena would produce a better outcome than the marketplace would. Be sure that you compare real market outcomes to real regulatory outcomes, not real market outcomes to ideal regulatory outcomes. Most arguments for privacy regulation simply fail to account for the behavior of the regulatory universe.

Adam has collected quotations on the subject of regulatory capture from many experts. I wrote a brief series of "real regulators" posts on the SEC and the Madoff scam a while back (1, 2, 3). And a recent article I'm fond of goes into the problem that many people think only consumers suffer, asking: "Are Regulators Rational?"

There's no good-tasting cough drop because the set of drops that remedy coughing and the set of drops that taste good are mutually exclusive. Not because of market failure.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower