Adam Thierer's Blog, page 136

April 8, 2011

Again, It's Really Hard to Bottle Up Digital Generativity / Openness

There's a nice piece of reporting from Ian Shapira in today's Washington Post entitled, "Once the Hobby of Tech Geeks, iPhone Jailbreaking Now a Lucrative Industry." In the article, Shapira documents the rise of independent, unauthorized Apple apps (especially tethering apps) and points out that what was once a small black market has now turned into a booming, maturing business sector in its own right. In fact, Sharpia notes, there are already "market leaders" in the field:

At the top of the jailbreaking hierarchy sits Jay Freeman, 29, the founder and operator of Cydia, the biggest unofficial iPhone app store, which offers about 700 paid designs and other modifications out of about 30,000 others that are free. Based out of an office near Santa Barbara, Calif., Freeman said Cydia, launched in 2008, now earns about $250,000 after taxes in profit annually. He just hired his first full-time employee from Delicious, the Yahoo-owned bookmarking site, to improve Cydia's design. "The whole point is to fight against the corporate overlord," Freeman said. "This is grass-roots movement, and that's what makes Cydia so interesting. Apple is this ivory tower, a controlled experience, and the thing that really bought people into jailbreaking is that it makes the experience theirs."

In another sign this black market is now going mainstream, advertisers are apparently flocking to it:

In what might be the ultimate sign that the jailbreak industry is losing its anti-establishment character, Toyota recently offered a free program on Cydia's store, promoting the company's Scion sedan. Once installed, the car is displayed on the background of the iPhone home screen, and the iPhone icons are re-fashioned to look like the emblem on the front grill.

Interestingly, however, some people now complain that Cydia is getting too big for its britches and has come to be "as domineering as Apple is in the non-jailbreak world." What delicious irony! Yet, I do not for one minute believe that Cydia has any sort of "lock" on the "unlocking" marketplace. This is an insanely dynamic sector that is subject to near-constant fits of disruptive technological change.

Anyway, I feel a bit vindicated when I read articles like Shapira's since I have spent the last few years pushing back against the theories set forth by various scholars, such as Jonathan Zittrain and Tim Wu, who claim that online openness or "generativity" are dying. They often cite Apple as the big, bad boogeyman of closed code and claim that Steve Jobs is hellbent on destroying digital generativity and the open Internet as we know it.

Of course, it is certainly true that Jobs and Apple prefer a more "closed" model that grants them more control over their products, such as the iPhone and iPad. And they make some good arguments why a certain amount of control is a good thing. It helps to have a more standardized platform for developers, for example, by avoiding fragmentation. A certain degree of control can also help to crack down on malicious apps in the App Store. And without a certain amount of control it becomes hard to honor warranties when phones or apps break.

Despite those excuses, Apple is still just a bit too domineering for some of us. I don't own any of their products. Never have; never will. If it's not tinker-friendly right out of the box, it's just not for me. I cannot even begin to count how many times I have rooted and installed new ROMs on my Droid OG. (Thank You CyanogenMod!) And I bricked my last Windows Mobile 6 phone after repeated hacking.

And, yet, Apple is still wildly successful and has millions of extremely happy customers who — for reasons that still boggle my mind — are willing to line up in the wee hours of the cold morning around the block in front Apple Stores to get their hands on the latest goodies the company has to offer. (Seriously, what is wrong with you people!)

But this gets back to the point I have reiterated in my debates with Zittrain, Wu, and the other "openness evangelicals": Even if I share their general love of more "open" and "generative" platforms or devices, there's no reason to be nearly as worried as they are about them "dying." And there's certainly no need for drastic action, especially of a regulatory nature, to work this out. The market for openness is working marvelously. Innovation continues to unfold rapidly in both directions along the "open" vs. "closed" continuum. Moreover, there certainly isn't any shortage of digital "generativity" taking place on both open and closed platforms today. Again, even though Jobs and Apple try to control their platform and App Store, some amazingly generative things are happening there every day and consumers absolutely adore their Apple devices.

Anyway, I discussed all these issues in much greater detail in my chapter on "The Case for Internet Optimism, Part 2 - Saving the Net From Its Supporters," which was included in the book, The Next Digital Decade: Essays on the Future of the Internet (2011). Simply stated, things are getting more open all the time and there's just no putting the generativity genie back in the bottle. Here's a short section that appears on page 149 of the book related to the issues discussed here:

______________________

Things Are Getting More Open All the Time Anyway

Most corporate attempts to bottle up information or close off their platforms end badly. The walled gardens of the past failed miserably. In critiquing Zittrain's book, Ann Bartow has noted that "if Zittrain is correct that CompuServe and America Online (AOL) exemplify the evils of tethering, it's pretty clear the market punished those entities pretty harshly without Internet governance-style interventions."[1] Indeed, let's not forget that AOL was the big, bad corporate boogeyman of Lessig's Code and yet, just a decade later, it has been relegated to an also-ran in the Internet ecosystem.

There are few reasons to believe that today's efforts to build such walled gardens would end much differently. Indeed, increasingly when companies or coders erect walls of any sort, holes form quickly. For example, it usually doesn't take long for a determined group of hackers to find ways around copy/security protections and "root" or "jailbreak" phones and other devices.[2] Once hacked, users are usually then able to configure their devices or applications however they wish, effectively thumbing their noses at the developers. This process tends to unfold in a matter of just days, even hours, after the release of a new device or operating system.

Number of Days Before New Devices Were "Rooted" or "Jailbroken" [3]

original iPhone

10 days

original iPod Touch

35 days

iPhone 3G

8 days

iPhone 3GS

1 day

iPhone 4

38 days

iPad

1 day

T-Mobile G1 (first Android phone)

13 days

Palm Pre

8 days

Of course, not every user will make the effort—or take the risk[4]—to hack their devices in this fashion, even once instructions are widely available for doing so. Nonetheless, even if copyright law might sometimes seek to restrict it, the hacking option still exists for those who wish to exercise it. Moreover, because many manufacturers know their devices are likely to be hacked, they are increasingly willing to make them more "open" right out of the gates or offer more functionality/flexibility to make users happy

[1] Bartow, supra note 17 at 1088, www.michiganlawreview.org/assets/pdfs/108/6/bartow.pdf

[2] "In living proof that as long as there's a thriving geek fan culture for a device, it will never be long for the new version to be jailbroken: behold iOS 4.1. Most people are perfectly willing to let their devices do the talking for them, accept what's given, and just run sanctioned software. But there are those intrepid few—who actually make up a fairly notable portion of the market—who want more out of their devices and find ways around the handicaps built into them by the manufacturers." Kit Dotson, New iOS for Apple TV Firmware Released, Promptly Decrypted, SiliconAngle, Sept. 28, 2010, http://siliconangle.com/blog/2010/09/28/new-ios-for-apple-tv-firmware-released-promptly-decrypted

[3] Original research conducted by author and Adam Marcus based on news reports.

[4] Rooting or jailbreaking a smartphone creates the risk of "bricking" the device—rendering it completely inoperable (and thus no more useful than a brick). Additionally, hacking devices in this fashion typically voids any manufacturer warranty.

April 6, 2011

Surveillance, San Francisco-Style

San Francisco's Entertainment Commission will soon be considering a jaw-dropping attack on privacy and free assembly. Here are some of the rules the Commission may adopt for any gathering of people expected to reach 100 or more:

3. All occupants of the premises shall be ID Scanned (including patrons, promoters, and performers, etc.). ID scanning data shall be maintained on a data storage system for no less than 15 days and shall be made available to local law enforcement upon request.

4. High visibility cameras shall be located at each entrance and exit point of the premises. Said cameras shall maintain a recorded data base for no less than fifteen (15 days) and made available to local law enforcement upon request.

Would you recognize a police state if you lived in one? How about a police city? The First Amendment right to peaceably assemble takes a big step back when your identity data and appearance are captured for law enforcement to use at whim simply because you showed up. (ht: PrivacyActivism.org)

Leading Free Market Groups Urge Congress to Update Key U.S. Privacy Law

This morning, the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee heard key administration officials testify about the statute that governs law enforcement access to private information held electronically by third parties. Several leading lawmakers are currently working to bring this law—the 1986 Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA)—into the information age so that it reflects Americans' reasonable privacy expectations in the era of webmail, mobile services, cloud computing and the like.

TechFreedom has led, in conjunction with the Competitive Enterprise Institute and Americans for Tax Reform's Digital Liberty Project, a coalition of leading free market public interest in a letter to the committee voicing their strong support for overhauling the quarter-century-old ECPA. The coalition—also including FreedomWorks, the Campaign for Liberty, the Washington Policy Center, Liberty Coalition, the Center for Financial Privacy and Human Rights, and Less Government—is urging Congress to extend traditional Fourth Amendment protections to Internet-based "cloud" and mobile location services while preserving the building blocks of law enforcement investigations.

The coalition letter explains that framers of the Bill of Rights ratified the Fourth Amendment to protect individuals from unreasonable, unwarranted searches and seizures by government officials. But since courts have not consistently applied these Constitutional protections to private information stored with cloud and mobile providers, many Americans' private information is vulnerable to warrant-less access by law enforcement. To remedy this, the letter proposes four reforms to ECPA that would resolve legal ambiguities and affirm Constitutional protections by establishing electronic privacy standards that are consistent with the Fourth Amendment.

"Major decisions regarding the future architecture of cloud computing are being made right now," explains the letter, calling for urgent action. "If Congress fails to enact ECPA reform, cloud computing services may be designed to rely on servers outside the U.S. Not only would this harm U.S. competitiveness, it could also, ironically, deny U.S. law enforcement access to cloud data—even with a lawful warrant."

Read the full coalition letter here or below.

For more on ECPA reform, see the September 2010 congressional statement submitted to the U.S. House and Senate Judiciary Committees by several free market public interest groups.

April 5, 2011

Event 4/7: What Should Lawmakers Do About Rogue Websites?

The Competitive Enterprise Institute and TechFreedom are hosting a panel discussion this Thursday featuring intellectual property scholars and Internet governance experts. The event will explore the need for, and concerns about, recent legislative proposals to give law enforcement new tools to combat so-called "rogue websites" that facilitate and engage in unlawful counterfeiting and copyright infringement.

Video of the event will be posted here on TechLiberation.com.

What:

"What Should Lawmakers Do About Rogue Websites?" — A CEI/TechFreedom event

When:

Thursday, April 7 (12:00 – 2:00 p.m.)

Where:

The National Press Club (529 14th Street NW, Washington D.C.)

Who:

Juliana Gruenwald, National Journal (moderator)

Daniel Castro, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation

Larry Downes, TechFreedom

Danny McPherson, VeriSign

Ryan Radia, Competitive Enterprise Institute

David Sohn, Center for Democracy & Technology

Thomas Sydnor, Association for Competitive Technology

Space is very limited. To guarantee a seat, please register for the event by emailing nciandella@cei.org.

Juliana Gruenwald, National Journal (moderator)

Daniel Castro, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation

Larry Downes, TechFreedom

Danny McPherson, VeriSign

Ryan Radia, Competitive Enterprise Institute

David Sohn, Center for Democracy & Technology

Thomas Sydnor, Association for Competitive Technology

Kinsley on Cyber-Politics & "How Microsoft Learned the ABCs of D.C."

Jack Shafer brought to my attention this terrific new Politico column by Michael Kinsley entitled, "How Microsoft Learned ABCs of D.C." In the editorial, Kinsley touches on some of the same themes I addressed in my recent piece here "On Facebook 'Normalizing Relations' with Washington" as well as in my Cato Institute essay from last year on"The Sad State of Cyber-Politics." Kinsley notes how Microsoft was originally bashed by many for not getting into the D.C. lobbying game early enough:

there even was a feeling that, in refusing to play the Washington game, Microsoft was being downright unpatriotic. Look, buddy, there is an American way of doing things, and that American way includes hiring lobbyists, paying lawyers vast sums by the hour, throwing lavish parties for politicians, aides, journalists and so on. So get with the program.

But after doing exactly that, Kinsley notes, the company got blasted for for being too aggressive in D.C.!

So that's what Microsoft did. It moved its "government affairs" office out of distant Chevy Chase and into the downtown K Street corridor. It bulked up on lawyers and hired the best-connected lobbyists. Soon, Microsoft was coming under criticism for being heavy-handed in its attempts to buy influence.

"But the sad thing is that it seems to have worked. Microsoft is no longer Public Enemy No. 1," Kinsley notes, and he continues on to reiterate a point I made in my last two essays: Google is the Great Satan now!

Best of all, the finger of blame has moved on — to Google, which now gets the blame for everything. It is an evil monopoly that uses its monopoly power to extend that monopoly into new areas. It must be stopped before all of its competitors are wiped out. And so on. This is all very familiar to anyone who worked at Microsoft in the late 1990s and (it must be admitted) very enjoyable. Microsoft last week piled on, bringing charges against Google before the European Union (which had given Microsoft an especially hard time), accusing it of a variety of nefarious practices, including some the EU had formerly accused Microsoft of.

Like I said in my earlier essays, you can file this all under "Revenge is a dish best served cold." For many years the shoe was on the other foot and Google was hammering Microsoft in court and in legislative and regulatory hearing rooms. But Microsoft now relishes its role as the ringleader of the rising War on Google and is using against Google the same antitrust playbook once used against them. Whether it's the legal battle over Google Books, Department of Justice reviews of various Google acquisitions, or other fights, Microsoft now stalks Google at every turn. And, if we are to believe this new Bloomberg report ("Google Said to Be Possible Target of U.S. FTC Antitrust Probe"), there will soon be hell to pay.

Kinsley concludes his essay on miserable yet entirely appropriate note:

As the Microsoft example suggests, the Washington culture of influence peddling is not entirely, or even primarily, the fault of the corporations that hire the lobbyists and pay the bills. It's a vast protection racket, practiced by politicians and political operatives of both parties. Nice little software company you've got here. Too bad if we have to regulate it or if Big Government programs force us to raise its taxes. Your archrival just wrote a big check to the Washington Bureaucrats Benevolent Society. Are you sure you wouldn't like to do the same?

It's a dismal state of affairs to say the least. We should want these high-tech companies competing in the business marketplace, not the political marketplace.

Kevin Poulsen on cyber crime

On the podcast this week, Kevin Poulsen, a senior editor at Wired News, former hacker, and author of Kingpin: How One Hacker Took Over the Billion-Dollar Cybercrime Underground, discusses his new book. Poulsen first talks about how he became interested in hacking and why he was eventually sent to prison for it. He then discusses his book, a true crime account of Max Butler, a white hat hacker turned black hat who went from security innovator to for-profit cyber criminal to hacker of other hackers, eventually taking over the cyber crime underground. Poulsen finally comments on cyber security policy, noting that while many security vulnerabilities exist today, he suspects that legislation is not the answer.

Related Links

"Kingpin by Kevin Poulsen," Wired

"'Kingpin,' by Kevin Poulsen: review," San Francisco Chronicle

"Kevin Poulsen Book Talk – Author of Kingpin," Stanford Law School

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

April 4, 2011

The Precautionary Principle in Information Technology Debates

I'm currently plugging away at a big working paper with the running title, "Argumentum in Cyber-Terrorem: A Framework for Evaluating Fear Appeals in Internet Policy Debates." It's an attempt to bring together a number of issues I've discussed here in my past work on "techno-panics" and devise a framework to evaluate and address such panics using tools from various disciplines. I begin with some basic principles of critical argumentation and outline various types of "fear appeals" that usually represent logical fallacies, including: argumentum in terrorem, argumentum ad metum, and argumentum ad baculum. But I'll post more about that portion of the paper some other day. For now, I wanted to post a section of that paper entitled "The Problem with the Precautionary Principle." I'm posting what I've got done so far in the hopes of getting feedback and suggestions for how to improve it and build it out a bit. Here's how it begins…

________________

The Problem with the Precautionary Principle

"Isn't it better to be safe than sorry?" That is the traditional response of those perpetuating techno-panics when their fear appeal arguments are challenged. This response is commonly known as "the precautionary principle." Although this principle is most often discussed in the field of environment law, it is increasingly on display in Internet policy debates.

The "precautionary principle" basically holds that since every technology and technological advance poses some theoretical danger or risk, public policy should be crafted in such a way that no possible harm will come from a particular innovation before further progress is permitted. In other words, law should mandate "just play it safe" as the default policy toward technological progress.

The problem with that logic, notes Kevin Kelly, author of What Technology Wants, is that because "every good produces harm somewhere… by the strict logic of an absolute precautionary principle no technologies would be permitted."[1] Or, as journalist Ronald Bailey has summarized this principle: "Anything new is guilty until proven innocent."[2] Under an information policy regime guided at every turn by a precautionary principle, digital innovation and technological progress would become impossible because trade-offs and uncertainly would be considered unacceptable.

This is why Aaron Wildavsky, author of the seminal 1988 book, Searching for Safety, spoke of the dangers of "trial without error" as compared to trial and error. Wildavsky argued that:

The direct implication of trial without error is obvious: if you can do nothing without knowing first how it will turn out, you cannot do anything at all. An indirect implication of trial without error is that if trying new things is made more costly, there will be fewer departures from past practice; this very lack of change may itself be dangerous in forgoing chances to reduce existing hazards. … [E]xisting hazards will continue to cause harm if we fail to reduce them by taking advantage of the opportunity to benefit from repeated trials.[3]

Simply stated: Life involves and requires that some level of risk be accepted for progress to occur. While some steps to anticipate or control for unforeseen circumstances and "plan for the worse" are sensible, going overboard forecloses opportunities and experiences that offer valuable lessons for individuals and society. University of Chicago legal scholar Cass Sunstein, who currently serves as Administrator of the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, has argued that "If the burden of proof is on the proponent of the activity or processes in question, the Precautionary Principle would seem to impose a burden of proof that cannot be met."[4]

Importantly, Wildavsky pointed out that the precautionary principle also downplays the important role of resiliency in human affairs. Through constant experimentation, humans learn valuable lessons about how the world works, which risks are real versus illusory or secondary, and how to assimilate new cultural, economic, and technological change into our lives. A rigid precautionary principle would disallow such a learning progress from unfolding and leave us more vulnerable to the most serious problems we might face as individuals or a society. "Allowing, indeed, encouraging, trial and error should lead to many more winners, because of (a) increased wealth, (b) increased knowledge, and (c) increased coping mechanisms, i.e., increased resilience in general."[5]

Recent work by Sean Lawson, an assistant professor in the Department of Communication at the University of Utah, has underscored the importance of resiliency as it pertains to cybersecurity. "Research by historians of technology, military historians, and disaster sociologists has shown consistently that modern technological and social systems are more resilient than military and disaster planners often assume," he finds.[6] "Just as more resilient technological systems can better respond in the event of failure, so too are strong social systems better able to respond in the event of disaster of any type."[7]

Resiliency is also a wise strategy as it pertains to Internet child safety issues, online privacy concerns, and online reputation management. Some risks in these contexts – such as underage access to objectionable content or the release of too much personal information – can be prevented through anticipatory regulatory policies. Increasingly, however, information proves too challenging to bottle up. Information control efforts today are greatly complicated by five phenomena unique to the Information Age: (1) media and technological convergence; (2) decentralized, distributed networking; (3) unprecedented scale of networked communications; (4) an explosion of the overall volume of information; and (5) unprecedented individual information sharing through user-generation of content and self-revelation of data. "The truth about data is that once it is out there, it's hard to control," says Jeff Jonas, an engineer with IBM.[8]

This is why resiliency becomes an even more attractive strategy compared to anticipatory regulation. Information will increasingly flow freely on interconnected, ubiquitous digital networks and getting those information genies back in their bottles would be an enormous challenge. Moreover, the costs of attempting to control information will exceed the benefits in most circumstances. Consequently, a strategy based on building resiliency will focus on education and empowerment-based strategies that allow for trial and error and encourage sensible, measured responses to the challenges posed by technological change.

[Note: I next plan to go on to discuss several case studies and outline the sorts of education and empowerment-based strategies that I believe represent the better approach to coping with technological change.]

[1] Kevin Kelly, What Technology Wants (New York: Viking, 2010), p. 247-8.

[2] Ronald Bailey, "Precautionary Tale," Reason, April 1999, http://reason.com/archives/1999/04/01....

[3] Aaron Wildavsky, Searching for Safety (Transaction Books, 1988), p. 38.

[4] Cass Sunstein, "The Paralyzing Principle," Regulation (Washington, DC: Cato Institute, Winter 2002-2003), p. 34, http://www.cato.org/pubs/regulation/regv25n4/v25n4-9.pdf. "The most serious problem with the Precautionary Principle is that it offers no guidance – not that it is wrong, but that it forbids all courses of action, including inaction," Sunstein says. "The problem is that the Precautionary Principle, as applied, is a crude and sometimes perverse method of promoting [] various goals, not least because it might be, and has been, urged in situations in which the principle threatens to injure future generations and harm rather than help those who are most disadvantaged. A rational system of risk regulation certainly takes precautions. But it does not adopt the Precautionary Principle." Id., p. 33, 37.

[5] Wildavsky, Id., p. 103.

[6] Sean Lawson, Beyond Cyber Doom: Cyber Attack Scenarios and the Evidence of History (Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, January 25, 2011), p. 31, http://mercatus.org/publication/beyon....

[7] Id., p. 29.

[8] Quoted in Jenn Webb, "The Truth about Data: Once It's Out There, It's Hard to Control," O'Reilly Radar, April 4, 2011, http://radar.oreilly.com/2011/04/jeff....

What Progress Looks Like

Kudos to Mashable for collecting these "10 Hilarious Vintage Cellphone Commercials" from the past two decades. Strangely, I don't remember ever seeing any of these when they originally aired [although some are foreign], but it might have been because I flipped the channel when they came on. Most of really horrendous. My favorite is the Radio Shack ad shown below, not just because of the phone, but because of the Bill Gates-looking kid at the end. And speaking of Radio Shack, check out the ad down below, which I originally posted here a few years ago, for a 1989 Tandy machine, then billed as its "Most Powerful Computer Ever." Accordingly, you would have had to practically mortgage your house to own it with a price tag of $8500! Whether its phones or computers — which are increasingly one in the same, of course — it's amazing how much progress we've seen in such a short period of time.

The Google Buzz Privacy Settlement as a Possible Public Choice Study

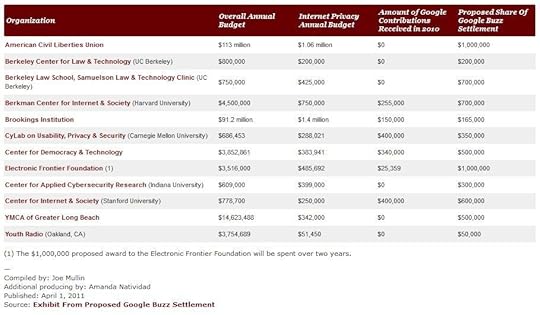

PaidContent.org has posted a chart showing "Who's Getting Buzz Settlement Money." This refers to the $9.5 million payout following the Federal Trade Commission settlement with Google a class action suit over its "Buzz" social networking service. Last week, the Federal Trade Commission entered into a consent decree with Google over its botched rollout of Buzz saying the search giant violated its own privacy policy. Google will also pay out to various advocacy groups according to the distribution seen in the chart as part of a separate class action. Payouts to advocates like this are not uncommon, although they are more often the result of a class action settlement than a regulatory agency consent decree. [Update/Correction 5:13 pm: I should have made it clear that this payout was the result of a class action lawsuit against Google and not the direct result of the FTC settlement. Apologies for that mistake, but still interested in the questions raised below.]

But that got me wondering whether this might make for good fodder for a case study by a public choice economist or political scientist. There are some really interesting questions raised by settlements like this that would be worth studying.

First, do rewards like this promote agitation with regulatory agencies for consent decrees? Regulatory advocates stand to gain a healthy cut of any final settlement, so it seems likely that they would seek such regulatory actions. It's noteworthy that, according to Computer Business News, "The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) has filed an objection to agreements Google has reached over its social network Buzz because it is not one of the beneficiaries of the privacy fund set up by Google." Apparently EPIC wants a $1.75 million cut. [Recall that EPIC wanted Google's Gmail banned when it came out back in 2004.] The ACLU, EFF, and CDT all made out handsomely from the settlement, too, and they have been among the primary cheerleaders for a new Internet regulatory regime in the name of protecting privacy.

Second, shouldn't this settlement money go to consumers who were supposedly harmed instead of to these regulatory advocates? Of course, finding and making whole a massive class of potentially aggrieved consumers would be extremely difficult and costly, especially because of the amorphous nature of the "harm" in question with something like Buzz. And so we instead get the payouts to the privacy regulatory advocates. The theory is that transferring money to these surrogates is the next best thing because they will stand up on consumers' behalf in the future. I'm not so sure. Privacy is a highly amorphous value and these regulatory advocates almost certainly do not represent the varied interests of all consumers.

Anyway, if you are an aspiring public choice econ or poly sci PhD student, this might make for an interesting study. It would be interesting to see how this money is spent and how much more aggressive these groups become in their push for privacy-related investigations/regulation when there is a nice pot of gold at the end of that particular rainbow.

April 2, 2011

Obama Accepts Transparency Award in Private

From the Politico's "Politico 44" blog:

President Obama finally and quietly accepted his "transparency" award from the open government community this week — in a closed, undisclosed meeting at the White House on Monday.

The secret presentation happened almost two weeks after the White House inexplicably postponed the ceremony, which was expected to be open to the press pool.

The same post also contains a great quote from Steve Aftergood, the director of the Project on Government Secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists, who said that the award was "aspirational," much like Mr. Obama's Nobel Peace Prize.

When am I going to receive a Pulitzer to encourage me to write better blog posts?

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower