Adam Thierer's Blog, page 138

March 25, 2011

Lessons from the Gmail Privacy Scare of 2004

Last night, Declan McCullagh of CNet posted two tweets related to the concerns already percolating in the privacy community about a new Apple and Android app called "Color," which allows those who use it to take photos and videos and instantaneously share them with other people within a 150-ft radius to create group photo/video albums. In other words, this new app marries photography, social networking, and geo-location.

Last night, Declan McCullagh of CNet posted two tweets related to the concerns already percolating in the privacy community about a new Apple and Android app called "Color," which allows those who use it to take photos and videos and instantaneously share them with other people within a 150-ft radius to create group photo/video albums. In other words, this new app marries photography, social networking, and geo-location.  And because the app's default setting is to share every photo and video you snap openly with the world, Declan wonders "How long will it take for the #privacy fundamentalists to object to Color.com's iOS/Android apps?" After all, he says facetiously, "Remember: market choices can't be trusted!" He then reminds us that there's really nothing new under the privacy policy sun and tat we've seen this debate unfold before, such as when Google released it's GMail service to the world back in 2004.

And because the app's default setting is to share every photo and video you snap openly with the world, Declan wonders "How long will it take for the #privacy fundamentalists to object to Color.com's iOS/Android apps?" After all, he says facetiously, "Remember: market choices can't be trusted!" He then reminds us that there's really nothing new under the privacy policy sun and tat we've seen this debate unfold before, such as when Google released it's GMail service to the world back in 2004.

Indeed, for me, this debate has a "Groundhog Day" sort of feel to it. I feel like I've been fighting the same fight with many privacy fundamentalists for the past decade. The cycle goes something like this:

an innovative new information-sharing / social networking technology appears on the scene.

the technology encourages more information production / sharing and defaults to sharing as the norm (but usually with opt-out capabilities or privacy settings of some sort built in).

importantly, the technology in question is almost always free to consumers.

immediately, a vociferous crowd of privacy fundamentalists lament the announcement and call for the technology or service to be rolled-back or even regulated by the government. At a minimum, major design changes (usually an opt-in privacy default) are requested. These advocates usually ignore or downplay the inherent quid pro quo involved in the deal, i.e., you share some info and tolerate some ads to get the free goodies.

most privacy-agnostic people (like me!) usually yawn, sit back and enjoy the new free goodies, and wonder what all the fuss is about. In other words, over time (and usually fairly quickly), social norms adjust to the new technologies and modes of sharing.

In this regard, my favorite case study of this process in action is the one that Declan already mentioned: Gmail. It's easy to forget now, but back in 2004 there was quite a hullabaloo over the introduction of Gmail. Indeed, the privacy fundamentalists wanted it stopped cold. Letters started flying from privacy groups, sent first directly to Google itself (31 groups signed this letter asking the company to roll back the service), and then to attorney general of California requesting an investigation following an immediate suspension of the service. Those signing that particular letter (Chris Jay Hoofnagle of EPIC, Beth Givens of Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, and Pam Dixon of the World Privacy Forum) also warned of civil and criminal penalties and private rights of action.

It was at about that time that, well, I blew my top. After seeing some traffic on Declan's old "Politech" listserv about this, and fearing that action might be forthcoming by government officials aimed at restricting this new technology, I fired off this response to the Gmail-haters on April 30, 2004:

-------- Original Message --------

Subject: RE: [Politech] EPIC letter compares Gmail to FBI's Carnivore,

Total Information Awareness [priv]

Date: Fri, 30 Apr 2004 09:16:54 -0400

From: Adam Thierer

To: Declan McCullagh

Oh brother, I can't take this lunacy from the privacy absolutists anymore:

(1) What part of VOLUNTARY is it that these privacy fundamentalists do

not understand? How many times and in how many ways must it be said: YOU

DO NOT HAVE TO SIGN UP FOR THIS FREE SERVICE!

(2) Second, these privacy absolutists persistently attempt to equate

private sector privacy concerns and government privacy violations. There

is a world of difference between the two and it basically comes down to

the fact that governments hold guns to our heads and coercively force us

to do certain things against our will. That is the real Big Brother

problem. Google, by contrast, isn't holding a gun to anyone's head and

forcing them to sign up.

(3) If you're concerned about how government might co-opt this service

for its own nefarious ends, that is not a Google problem, that is a Big

Government problem. Let's work together to properly limit the

surveillance powers of government instead of shutting down any new

private service or technology that we feel the feds might have to chance

to abuse.

(4) Final point about these privacy fanatics: Do they not believe in

freedom of contract? Do I or do I not have a right to contract with a

company to exchange certain forms of personal information for a the

right to free e-mail access and storage? Can I not VOLUNTARILY agree to

such a deal? If not, then I fear that there are a heck of lot of things

in this world that these people would make illegal in the name of

"protecting privacy."

Do they believe that companies like Google will - - out of the goodness

of their hearts - - just hand over free e-mail services and massive

storage capacity to everyone without anything in exchange? There is no

free lunch in this world but Google is giving us about the closest thing

to it. And yet, the privacy fanatics want to reject that offer on the

behalf over everyone in society. Well guess what EPIC... you don't speak

for me and a lot of other people in this world who will be more than

happy to cut this deal with Google. So do us a favor and don't ask the

government to shut down a service just because you don't like it.

Privacy is a subjective condition and your value preferences are not

representative of everyone else's values in our diverse nation. Stop

trying to coercively force your values and choices on others. We can

decide these things on our own, thank you very much.

It turns out that I didn't really have as much to fear as I thought when I fired off that angry email. Most people immediately embraced the new Gmail service. And why wouldn't they? It was an amazing innovation at just the right price — free! Don't forget that, at that time, Yahoo! mail (the leading webmail provider) offered customers less than 10 megabytes of email storage. By contrast, Gmail offered users an astounding gigabyte of storage that would grow steadily over time. Rather than charging some users for more storage or special features, Google paid for the service by showing advertisements next to each email "contextually" targeted to keywords in that email — a far more profitable form of advertising than "dumb banner" ads previously used by other webmail providers. That raised some privacy concerns, but it also offered users the ultimate email free lunch. And they ate it up.

Today, 190 million people around the world use Gmail and the service continues to evolve to meet the needs of users. While I'm not a fan of Gmail's spartan user interface and lack of other useful features found in other services (like Outlook loaded up with Xobni), there's no doubt that Gmail has been a terrific boon to consumers. But we should not so easily forget that some people wanted to preemptively kill it by imposing the equivalent of what I have called a "Privacy Precautionary Principle" and stopping innovation before they had given it their blessing.

Again, as I noted in my 2004 rant above, many privacy fundamentalist too often forget that privacy is a highly subjective and ever-changing condition. As Abelson, Ledeen, and Lewis noted in their excellent recent book, Blown to Bits:

The meaning of privacy has changed, and we do not have a good way of describing it. It is not the right to be left alone, because not even the most extreme measures will disconnect our digital selves from the rest of the world. It is not the right to keep our private information to ourselves, because the billions of atomic factoids don't any more lend themselves into binary classification, private or public. (p. 68)

This struggle to conceptualize privacy and then protect it is going to continue and become quite a heated debate at times. I want to be clear, however, that while I do not share the values of those in the privacy fundamentalist camp, I do understand and appreciate that there are some people who are hyper-sensitive about this issue and I'm fine with them pressuring companies to change their privacy policies or, better yet, encouraging them to offer more tools that will allow users to better manage their own privacy. I think Microsoft, Facebook,Yahoo! and Google (among many others) have made some amazing strides in this regard and some of the credit must go to the hard-core privacy advocates for pushing them to offer more flexible privacy-enhancing tools and settings for those who demand them.

But let's be clear about another thing: This should be an evolutionary, experimental process. Educating and empowering consumers to handle their personal privacy settings is a wonderful thing. On the other hand, making those decisions for consumers preemptively, as some privacy advocates often seem to want to do, is an entirely different matter. A Privacy Precautionary Principle mentality — as we saw in display in the early spat over Gmail — would have resulted in hundreds of millions of people being denied an amazingly innovative new service based on largely on phantom fears and conjectural "harms." It is better to let these things play out in the information marketplace and see what the ongoing interaction of consumers and companies yields in terms of new innovation and new privacy settings / norms. Those new settings and norms may not always be to the liking of some privacy fundamentalists, or even to privacy agnostics like me, but that experimental, evolutionary, organic process remains the right way to go if we value both progress and liberty.

March 24, 2011

Search Bias and Antitrust

[Cross-posted at Truthonthemarket.com]

There is an antitrust debate brewing concerning Google and "search bias," a term used to describe search engine results that preference the content of the search provider. For example, Google might list Google Maps prominently if one searches "maps" or Microsoft's Bing might prominently place Microsoft affiliated content or products.

Apparently both antitrust investigations and Congressional hearings are in the works; regulators and commentators appear poised to attempt to impose "search neutrality" through antitrust or other regulatory means to limit or prohibit the ability of search engines (or perhaps just Google) to favor their own content. At least one proposal goes so far as to advocate a new government agency to regulate search. Of course, when I read proposals like this, I wonder where Google's share of the "search market" will be by the time the new agency is built.

As with the net neutrality debate, I understand some of the push for search neutrality involves an intense push to discard traditional economically-grounded antitrust framework. The logic for this push is simple. The economic literature on vertical restraints and vertical integration provides no support for ex ante regulation arising out of the concern that a vertically integrating firm will harm competition through favoring its own content and discriminating against rivals. Economic theory suggests that such arrangements may be anticompetitive in some instances, but also provides a plethora of pro-competitive explanations. Lafontaine & Slade explain the state of the evidence in their recent survey paper in the Journal of Economic Literature:

We are therefore somewhat surprised at what the weight of the evidence is telling us. It says that, under most circumstances, profit-maximizing vertical-integration decisions are efficient, not just from the firms' but also from the consumers' points of view. Although there are isolated studies that contradict this claim, the vast majority support it. Moreover, even in industries that are highly concentrated so that horizontal considerations assume substantial importance, the net effect of vertical integration appears to be positive in many instances. We therefore conclude that, faced with a vertical arrangement, the burden of evidence should be placed on competition authorities to demonstrate that that arrangement is harmful before the practice is attacked. Furthermore, we have found clear evidence that restrictions on vertical integration that are imposed, often by local authorities, on owners of retail networks are usually detrimental to consumers. Given the weight of the evidence, it behooves government agencies to reconsider the validity of such restrictions.

Of course, this does not bless all instances of vertical contracts or integration as pro-competitive. The antitrust approach appropriately eschews ex ante regulation in favor of a fact-specific rule of reason analysis that requires plaintiffs to demonstrate competitive harm in a particular instance. Again, given the strength of the empirical evidence, it is no surprise that advocates of search neutrality, as net neutrality before it, either do not rely on consumer welfare arguments or are willing to sacrifice consumer welfare for other objectives.

I wish to focus on the antitrust arguments for a moment. In an interview with the San Francisco Gate, Harvard's Ben Edelman sketches out an antitrust claim against Google based upon search bias; and to his credit, Edelman provides some evidence in support of his claim.

I'm not convinced. Edelman's interpretation of evidence of search bias is detached from antitrust economics. The evidence is all about identifying whether or not there is bias. That, however, is not the relevant antitrust inquiry; instead, the question is whether such vertical arrangements, including preferential treatment of one's own downstream products, are generally procompetitive or anticompetitive. Examples from other contexts illustrate this point.

Grocery product manufacturers contract for "bias" with supermarkets through slotting contracts and other shelf space payments. The bulk of economic theory and evidence on these contracts suggest that they are generally efficient and a normal part of the competitive process. Vertically integrated firms may "bias" their own content in ways that increase output. Whether bias occurs within the firm (as is the case with Google favoring its own products) or by contract (the shelf space example) should be of no concern for Edelman and those making search bias antitrust arguments. Economists have known since Coase — and have been reminded by Klein, Alchian, Williamson and others — that firms may achieve by contract anything they could do within the boundaries of the firm. The point is that, in the economics literature, it is well known that content self-promoting incentives in a vertical relationship can be either efficient or anticompetitive depending on the circumstances of the situation. The empirical literature suggests that such relationships are mostly pro-competitive and that restrictions upon the abilities of firms to enter them generally reduce consumer welfare.

Edelman is an economist, and so I find it a bit odd that he has framed the "bias" debate without reference to any of this literature. Instead, his approach appears to be that bias generates harm to rivals and that this harm is a serious antitrust problem. (Or in other places, that the problem is that Google exhibits bias but its employees may have claimed otherwise at various points; this is also antitrust-irrelevant.) For example, Edelman writes:

Search bias is a mechanism whereby Google can leverage its dominance in search, in order to achieve dominance in other sectors. So for example, if Google wants to be dominant in restaurant reviews, Google can adjust search results, so whenever you search for restaurants, you get a Google reviews page, instead of a Chowhound or Yelp page. That's good for Google, but it might not be in users' best interests, particularly if the other services have better information, since they've specialized in exactly this area and have been doing it for years.

"Leveraging" one's dominance in search, of course, takes a bit more than bias. But I was quite curious about Edelman's evidence and so I went and looked at Edelman and Lockwood. Here is how they characterize their research question: "Whether search engines' algorithmic results favor their own services, and if so, which search engines do so most, to what extent, and in what substantive areas." Here is how the authors describe what they did to test the hypothesis that Google engages in more search bias than other search engines:

To formalize our analysis, we formed a list of 32 search terms for services commonly provided by search engines, such as "email", "calendar", and "maps". We searched for each term using the top 5 search engines: Google, Yahoo, Bing, Ask, and AOL. We collected this data in August 2010.

We preserved and analyzed the first page of results from each search. Most results came from sources independent of search engines, such as blogs, private web sites, and Wikipedia. However, a significant fraction – 19% – came from pages that were obviously affiliated with one of the five search engines. (For example, we classified results from youtube.com and gmail.com as Google, while Microsoft results included msn.com, hotmail.com, live.com, and Bing.)

Here is the underlying data for all 32 terms; so far, so good. A small pilot study examining whether and to what extent search engines favor their own content is an interesting project — though, again, I'm not sure it says anything about the antitrust issues. No surprise: they find some evidence that search engines exhibit some bias in favor of affiliated sites. You can see all of the evidence at Edelman's site (again, to his credit). Interpretations of these results vary dramatically. Edelman sees a serious problem. Danny Sullivan begs to differ ("Google only favors itself 19 percent of the time"), and also makes the important point that the study took place before Yahoo searches were powered by Bing.

In their study, Edelman and Lockwood appear at least somewhat aware that bias and vertical integration can be efficient although they do not frame it in those terms. They concede, for example, that "in principle, a search engine might feature its own services because its users prefer these links." To distinguish between these two possibilities, they conceive of the following test:

To test the user preference and bias hypotheses, we use data from two different sources on click-through-rate (CTR) for searches at Google, Yahoo, and Bing. Using CTR data from comScore and another service that (with users' permission) tracks users' searches and clicks (a service which prefers not to be listed by name), we analyze the frequency with which users click on search results for selected terms. The data span a four-week period, centered around the time of our automated searches. In click-through data, the most striking pattern is that the first few search results receive the vast majority of users' clicks. Across all search engines and search terms, the first result received, on average, 72% of users' clicks, while the second and third results received 13% and 8% of clicks, respectively.

So far, no surprises. The first listing generates greater incremental click-through than the second or third listing. Similarly, the eye-level shelf space generates more sales than less prominent shelf space. The authors have a difficult time distinguishing user preference from bias:

This concentration of users' clicks makes it difficult to disprove the user preference hypothesis. For example, as shown in Table 1, Google and Yahoo each list their own maps service as the first result for the query "maps". Our CTR data indicates that Google Maps receives 86% of user clicks when the search is performed on Google, and Yahoo Maps receives 72% of clicks when the search is performed on Yahoo. One might think that this concentration is evidence of users' preference for the service affiliated with their search engine. On the other hand, since clicks are usually highly concentrated on the first result, it is possible that users have no such preference, and that they are simply clicking on the first result because it appears first. Moreover, since the advantage conferred by a result's rank likely differs across different search queries, we do not believe it is appropriate to try to control for ranking in a regression.

The interesting question from a consumer welfare perspective is not what happens to the users without a strong preference for Google Maps or Yahoo Maps. Users without a strong preference are likely to click-through on whatever service is offered on their search engine of choice. There is no significant welfare loss from a consumer who is indifferent between Google Maps and Yahoo Maps from choosing one over the other.

The more interesting question is whether users with a strong preference for a non-Google product are foreclosed from access to consumers by search bias. When Google ranks its Maps above others, but a user with a strong preference for Yahoo Maps finds it listed second, is the user able to find his product of choice? Probably if it is listed second. Probably not if it is delisted or something more severe. Edelman reports some data on this issues:

Nevertheless, there is one CTR pattern that would be highly suggestive of bias. Suppose we see a case in which a search engine ranks its affiliated result highly, yet that result receives fewer clicks than lower results. This would suggest that users strongly prefer the lower result — enough to overcome the effect of the affiliated result's higher ranking.

Of course this is consistent with bias; however, to repeat the critical point, this bias does not inexorably lead to — or even suggest — an antitrust problem. Let's recall the shelf space analogy. Consider a supermarket where Pepsi is able to gain access to the premium eye-level shelf space but consumers have a strong preference for Coke. Whether or not the promotional efforts of Pepsi will have an impact on competition depend on whether Coke is able to get access to consumers. In that case, it may involve reaching down to the second or third shelf. There might be some incremental search costs involved. And even if one could show that Coke sales declined dramatically in response to Pepsi's successful execution of its contractual shelf-space bias strategy, that merely shows harm to rivals rather than harm to competition. If Coke-loving consumers can access their desired product, Coke isn't harmed, and there is certainly no competitive risk.

So what do we make of evidence that in the face of search engine bias, click-through data suggest consumers will still pick lower listings? One inference is that consumers with strong preferences for content other than the biased result nonetheless access their preferred content. It is difficult to see a competitive problem arising in such an environment. Edelman anticipates this point somewhat when observes during his interview:

The thing about the effect I've just described is you don't see it very often. Usually the No. 1 link gets twice as many clicks as the second result. So the bias takes some of the clicks that should have gone to the right result. It seems most users are influenced by the positioning.

This fails to justify Edelman's position. First off, in a limited sample of terms, its unclear what it means for these reversals not to happen "very often." More importantly, so what that the top link gets twice as many clicks as the second link? The cases where the second link gets the dominant share of clicks-through might well be those where users have a strong preference for the second listed site. Even if they are not, the antitrust question is whether search bias is efficient or poses a competitive threat. Most users might be influenced by the positioning because they lack a strong preference or even any preference at all. That search engines compete for the attention of those consumers, including through search bias, should not be surprising. But it does not make out a coherent claim of consumer harm.

The 'compared to what' question looms large here. One cannot begin to conceive of answering the search bias problem — if it is a problem at all — from a consumer welfare perspective until they pin down the appropriate counterfactual. Edelman appears to assume — when he observes that "bias takes some of the clicks that should have gone to the right result" — that the benchmark "right result" is that which would prevail if listings were correlated perfectly with aggregate consumer preference. My point here is simple: that comparison is not the one that is relevant to antitrust. An antitrust inquiry would distinguish harm to competitors from harm to competition; it would focus its inquiry on whether bias impaired the competitive process by foreclosing rivals from access to consumers and not merely whether various listings would be improved but for Google's bias. The answer to that question is clearly yes. The relevant question, however, is whether that bias is efficient. Evidence that other search engines with much smaller market shares, and certainly without any market power, exhibit similar bias would suggest to most economists that the practice certainly has some efficiency justifications. Edelman ignores that possibility and by doing so, ignores decades of economic theory and empirical evidence. This is a serious error, as the overwhelming lesson of that literature is that restrictions on vertical contracting and integration are a serious threat to consumer welfare.

I do not know what answer the appropriate empirical analysis would reveal. As Geoff and I argue in this paper, however, I suspect a monopolization case against Google on these grounds would face substantial obstacles. A deeper understanding of the competitive effects of search engine bias is a worthy project. Edelman should also be applauded for providing some data that is interesting fodder for discussion. But my sense of the economic arguments and existing data are that they do not provide the support for an antitrust attack against search bias against Google specifically, nor the basis for a consumer-welfare grounded search neutrality regime.

March 23, 2011

Getting to Know Your RFID

App Store Wars: Apple, Amazon, Google, Microsoft & Dynamic Platform Competition

Venture capitalist Bill Gurley asked a good question in a Tweet late last night when he was "wondering if Apple's 30% rake isn't a foolish act of hubris. Why drive Amazon, Facebook, and others to different platforms?" As most of you know, Gurley is referring to Apple's announcement in February that it would require a 30% cut of app developers' revenues if they wanted a place in the Apple App Store.

Indeed, why would Apple be so foolish? Of course, some critics will cry "monopoly!" and claim that Apple's "act of hubris" was simply a logical move by a platform monopolist to exploit its supposedly dominant position in the mobile OS / app store marketplace. But what then are we to make of Amazon's big announcement yesterday that it was jumping in the ring with its new app store for Android? And what are we to make of the fact that Google immediately responded to Apple's 30% announcement by offering publishers a more reasonable 10%-of-the-cut deal? And, as Gurley notes, you can't forget about Facebook. Who knows what they have up their sleeve next. They've denied any interest in marketing their own phone and, at least so far, have not announced any intention to offer a competing app store, but why would they need to? Their platform can integrate apps directly into it! Oh, and don't forget that there's a little company called Microsoft out there still trying to stake its claim to a patch of land in the mobile OS landscape. Oh, and have you visited the HP-Palm development center lately? Some very interesting things going on there that we shouldn't ignore.

Indeed, why would Apple be so foolish? Of course, some critics will cry "monopoly!" and claim that Apple's "act of hubris" was simply a logical move by a platform monopolist to exploit its supposedly dominant position in the mobile OS / app store marketplace. But what then are we to make of Amazon's big announcement yesterday that it was jumping in the ring with its new app store for Android? And what are we to make of the fact that Google immediately responded to Apple's 30% announcement by offering publishers a more reasonable 10%-of-the-cut deal? And, as Gurley notes, you can't forget about Facebook. Who knows what they have up their sleeve next. They've denied any interest in marketing their own phone and, at least so far, have not announced any intention to offer a competing app store, but why would they need to? Their platform can integrate apps directly into it! Oh, and don't forget that there's a little company called Microsoft out there still trying to stake its claim to a patch of land in the mobile OS landscape. Oh, and have you visited the HP-Palm development center lately? Some very interesting things going on there that we shouldn't ignore.

What these developments illustrate is a point that I have constantly reiterated here: Markets are extremely dynamic, and when markets are built upon code, the pace and nature of change becomes unrelenting and utterly unpredictable. It is often during what some claim is a given sector's darkest hour that the most exciting things are happening within it. That very much seems to be the case in the mobile OS / app store world. Companies and coders are responding to incentives. With it's 30% rake, Apple has made what many consider a massive strategic miscalculation with competitors, consumers, and critics alike. In other words, opportunity knocks for innovative alternatives.

But some critics — especially those in the academy– continue to suffer from a "static snapshot" mentality and tend to underplay this dynamic process of market discovery and entrepreneurialism. Far too often, such critics look only at the day's seeming bad news (like Apple's 30% announcement) and claim that the sky is falling. In their myopia (and seeming desire to have someone or something intervene to "make things right") they often fail to follow up and investigate how markets respond to bone-headed moves. It's a point I've gone to great lengths to make in my battles with Professors Lessig, Zittrain, and Wu. Here's how I put it in a debate with Lessig two years ago when I was contrasting the "cyber-libertarian" vs. "cyber-collectivst" modes of thinking about these issues:

Cyber-libertarians are not oblivious to the problems Lessig raises regarding "bad code," or what might even be thought of as "code failures." In fact, when I wake up each day and scan TechMeme and my RSS reader to peruse the digital news of the day, I am always struck by the countless mini-market failures I am witnessing. I think to myself, for example: "Wow, look at the bone-headed move Facebook just made on privacy! Ugh, look at the silliness Sony is up to with rootkits! Geez, does Google really want to do that?" And so on. There seems to be one such story in the news every day.

But here's the amazing thing: I usually wake up the next day, fire up my RSS reader again, and find a world almost literally transformed overnight. I see the power of public pressure, press scrutiny, social norms, and innovation by competitors combining to correct the "bad code" or "code failures" of the previous day. OK, so sometimes it takes longer that a day, a week, or a month. And occasionally legal sanctions must enter the picture if the companies or coders did something particularly egregious. But, more often than not, markets evolve and bad code eventually gives way to better code; short-term "market failures" give rise to a world of innovative alternatives.

Thus, at risk of repeating myself, I must underscore the key principles that separate the cyber-libertarian and cyber-collectivist schools of thinking. It comes down to this: The cyber-libertarian believes that "code failures" are ultimately better addressed by voluntary, spontaneous, bottom-up, marketplace responses than by coerced, top-down, governmental solutions. Moreover, the decisive advantage of the market-driven approach to correcting code failure comes down to the rapidity and nimbleness of those response(s).

And that's very much what we're seeing play out in the mobile OS / app store ecosystem today: Apple's "foolish act of hubris," as Gurley calls it, is driving incredible innovation as critics, consumers, and competitors think about how alternative platforms can offer a better experience. It's certainly true that none of these competing platforms or app stores have Apple's reach today. But who cares? The fact that they exist and that innovation continues at such a healthy clip is all that counts.

Cyber-capitalism works, when you let it.

March 22, 2011

No Facts, No Problem?

[Cross-Posted at Truthonthemarket.com]

There has been, as is to be expected, plenty of casual analysis of the AT&T / T-Mobile merger to go around. As I mentioned, I think there are a number of interesting issues to be resolved in an investigation with access to the facts necessary to conduct the appropriate analysis. Annie Lowrey's piece in Slate is one of the more egregious violators of the liberal application of "folk economics" to the merger while reaching some very confident conclusions concerning the competitive effects of the merger:

Merging AT&T and T-Mobile would reduce competition further, creating a wireless behemoth with more than 125 million customers and nudging the existing oligopoly closer to a duopoly. The new company would have more customers than Verizon, and three times as many as Sprint Nextel. It would control about 42 percent of the U.S. cell-phone market.

That means higher prices, full stop. The proposed deal is, in finance-speak, a "horizontal acquisition." AT&T is not attempting to buy a company that makes software or runs network improvements or streamlines back-end systems. AT&T is buying a company that has the broadband it needs and cutting out a competitor to boot—a competitor that had, of late, pushed hard to compete on price. Perhaps it's telling that AT&T has made no indications as of yet that it will keep T-Mobile's lower rates.

Full stop? I don't think so. Nothing in economic theory says so. And by the way, 42 percent simply isn't high enough to tell a merger to monopoly story here; and Lowrey concedes some efficiencies from the merger ("buying a company that has the broadband it needs" is an efficiency!). To be clear, the merger may or may not pose competitive problems as a matter of fact. The point is that serious analysis must be done in order to evaluate its likely competitive effects. And of course, Lowrey (H/T: Yglesias) has no obligation to conduct serious analysis in a column — nor do I in a blog post. But this idea that the market concentration is an incredibly useful and — in her case, perfectly accurate — predictor of price effects is devoid of analytical content and also misleads on the relevant economics.

Quite the contrary, so undermined has been the confidence in the traditional concentration-price notions of horizontal merger analysis that the antitrust agencies' 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines are premised in large part upon the notion that modern merger analysis considers shares to be an inherently unreliable predictor of competitive effects!! (For what its worth, a recent The Wall Street Journal column discussing merger analysis makes the same mistake — that is, suggests that the merger analysis comes down to shares and HHIs. It doesn't.)

To be sure, the merger of large firms with relatively large shares may attract significant attention, may suggest that the analysis drags on for a longer period of time, and likely will provide an opportunity for the FCC to extract some concessions. But what I'm talking about is the antitrust economics here, not the political economy. That is, will the merger increase prices and harm consumers? With respect to the substantive merits, there is a fact-intensive economic analysis that must be done before anybody makes strong predictions about competitive effects. The antitrust agencies will conduct that analysis. So will the parties. Indeed, the reported $3 billion termination fee suggests that AT&T is fairly confident it will get this through; and it clearly thought of this in advance. It is not as if the parties' efficiencies contentions are facially implausible. The idea that the merger could alleviate spectrum exhaustion, that there are efficiencies in spectrum holdings, and that this will facilitate expansion of LTE are worth investigating on the facts; just as the potentially anticompetitive theories are. I don't have strong opinions on the way that analysis will come out without doing it myself or at least having access to more data.

I'm only reacting to, and rejecting, the idea that we should simplify merger analysis to the dual propositions — that: (1) an increase in concentration leads to higher prices, and (2) when data doesn't comport with (1) we can dismiss it by asserting without evidence that prices would have fallen even more. This approach is, let's just say, problematic.

In the meantime, the Sprint CEO has publicly criticized the deal. As I've discussed previously, economic theory and evidence suggest that when rivals complain about a merger, it is likely to increase competition rather than reduce it. This is, of course, a rule of thumb. But it is one that generates much more reliable inferences than the simple view — rejected by both theory and evidence — that a reduction in the number of firms allows leads to higher prices. Yglesias points out, on the other hand, that rival Verizon prices increased post-merger (but did it experience abnormal returns? What about other rivals?), suggesting the market expects the merger to create market power. At least there we are in the world of casual empiricism rather than misusing theory.

Adam Thierer here at TLF provides some insightful analysis as to the political economy of deal approval. Karl Smith makes a similar point here.

The AT&T and T-Mobile Merger

[Cross-Posted at Truthonthemarket.com]

The big merger news is that AT&T is planning to acquire T-Mobile. From the AT&T press release:

AT&T Inc. (NYSE: T) and Deutsche Telekom AG (FWB: DTE) today announced that they have entered into a definitive agreement under which AT&T will acquire T-Mobile USA from Deutsche Telekom in a cash-and-stock transaction currently valued at approximately $39 billion. The agreement has been approved by the Boards of Directors of both companies.

AT&T's acquisition of T-Mobile USA provides an optimal combination of network assets to add capacity sooner than any alternative, and it provides an opportunity to improve network quality in the near term for both companies' customers. In addition, it provides a fast, efficient and certain solution to the impending exhaustion of wireless spectrum in some markets, which limits both companies' ability to meet the ongoing explosive demand for mobile broadband.

With this transaction, AT&T commits to a significant expansion of robust 4G LTE (Long Term Evolution) deployment to 95 percent of the U.S. population to reach an additional 46.5 million Americans beyond current plans – including rural communities and small towns. This helps achieve the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and President Obama's goals to connect "every part of America to the digital age." T-Mobile USA does not have a clear path to delivering LTE.

As the press release suggests, the potential efficiencies of the deal lie in relieving spectrum exhaustion in some markets as well as 4G LTE. AT&T President Ralph De La Vega, in an interview, described the potential gains as follows:

The first thing is, this deal alleviates the impending spectrum exhaust challenges that both companies face. By combining the spectrum holdings that we have, which are complementary, it really helps both companies. Second, just like we did with the old AT&T Wireless merger, when we combine both networks what we are going to have is more network capacity and better quality as the density of the network grid increases.In major urban areas, whether Washington, D.C., New York or San Francisco, by combining the networks we actually have a denser grid. We have more cell sites per grid, which allows us to have a better capacity in the network and better quality. It's really going to be something that customers in both networks are going to notice.

The third point is that AT&T is going to commit to expand LTE to cover 95 percent of the U.S. population.

T-Mobile didn't have a clear path to LTE, so their 34 million customers now get the advantage of having the greatest and latest technology available to them, whereas before that wasn't clear. It also allows us to deliver that to 46.5 million more Americans than we have in our current plans. This is going to take LTE not just to major cities but to rural America.

At least some of the need for more spectrum is attributable to the success of the iPhone:

This transaction quickly provides the spectrum and network efficiencies necessary for AT&T to address impending spectrum exhaust in key markets driven by the exponential growth in mobile broadband traffic on its network. AT&T's mobile data traffic grew 8,000 percent over the past four years and by 2015 it is expected to be eight to 10 times what it was in 2010. Put another way, all of the mobile traffic volume AT&T carried during 2010 is estimated to be carried in just the first six to seven weeks of 2015. Because AT&T has led the U.S. in smartphones, tablets and e-readers – and as a result, mobile broadband – it requires additional spectrum before new spectrum will become available.

On regulatory concerns, De La Vega observes:

We are very respectful of the processes the Department of Justice and (other regulators) use. The criteria that has been used in the past for mergers of this type is that the merger is looked at (for) the benefits it brings on a market-by-market basis and how it impacts competition.

Today, when you look across the top 20 markets in the country, 18 of those markets have five or more competitors, and when you look across the entire country, the majority of the country's markets have five or more competitors. I think if the criteria that has been used in the past is used against this merger, I think the appropriate authorities will find there will still be plenty of competition left.

If you look at pricing as a key barometer of the competition in an industry, our industry despite all of the mergers that have taken place in the past, (has) actually reduced prices to customers 50 percent since 1999. Even when these mergers have been done in the past they have always benefited the customers and we think they will benefit again.

Obviously, the deal is expected to generate significant regulatory scrutiny and will trigger a lot of interesting discussion and analysis of the state or wireless competition in the U.S. With the forthcoming FCC Wireless Competition Report likely to signal the FCC's position on the issue, and split approval authority with the conventional antitrust agencies, there appears to be significant potential for inter-agency conflict.

Greg Stirling at Searchengineland notes that "AT&T and T-Mobile said that they expect regulatory review to take up to 12 months." I'll take the "over." Stirling also notes, in an interesting post, the $3 billion termination fee owed to T-Mobile if the deal gets blocked. How's that for a confidence signal? In any event, it will be interesting to watch this unfold.

Here is an interesting preview, from AT&T executives this morning, of some of the arguments AT&T will be advancing in the coming months to achieve regulatory approval. Some of the most critical issues to parse out will be previous historical experience with cellular mergers, and whether, in fact, it is likely that the merger will bring about substantial efficiencies and facilitate bringing LTE to new markets. The preview includes the following chart, suggesting that significant price increases are not likely as a result of the merger based upon past experience.

No doubt there will be further opportunity to comment upon developments here over the next 12-18 months.

Court Rejects Google Books Settlement — Now What?

Today, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York rejected a proposed class action settlement agreement between Google, the Authors Guild, and a coalition of publishers. Had it been approved, the settlement would have enabled Google to scan and sell millions of books, including out of print books, without getting explicit permission from the copyright owner. (Back in 2009, I submitted an amicus brief to the court regarding the privacy implications of the settlement agreement, although I didn't take a position on its overall fairness.)

While the court recognized in its ruling (PDF) that the proposed settlement would "benefit many" by creating a "universal digital library," it ultimately concluded that the settlement was not "fair, adequate, and reasonable." The court further concluded that addressing the troubling absence of a market in orphan works is a "matter for Congress," rather than the courts.

Both chambers of Congress are currently working hard to tackle patent reform and rogue websites. Whatever one thinks about the Google Books settlement, Judge Chin's ruling today should serve as a wake-up call that orphan works legislation should also be a top priority for lawmakers.

Today, millions of expressive works cannot be enjoyed by the general public because their copyright owners cannot be found, as we've frequently pointed out on these pages (1, 2, 3, 4). This amounts to a massive black hole in copyright, severely undermining the public interest. Unfortunately, past efforts in Congress to meaningfully address this dilemma have failed.

In 2006, the U.S. Copyright Office recommended that Congress amend the Copyright Act by adding an exception for the use and reproduction of orphan works contingent on a "reasonably diligent search" for the copyright owner. The proposal also would have required that users of orphan works pay "reasonable compensation" to copyright owners if they emerge.

A similar solution to the orphan works dilemma was put forward by Jerry Brito and Bridget Dooling. They suggested in a 2006 law review article that Congress establish a new affirmative defense in copyright law that would permit a work to be reproduced without authorization if no rightsholder can be found following a reasonable, good-faith search.

Jane Yakowitz on How Privacy Regulation Threatens Research & Knowledge

Jane Yakowitz of Brooklyn Law School recently posted an interesting 63-page paper on SSRN entitled, "Tragedy of the Data Commons." For those following the current privacy debates, it is must reading since it points out a simple truism: increased data privacy regulation could result in the diminution of many beneficial information flows.

Jane Yakowitz of Brooklyn Law School recently posted an interesting 63-page paper on SSRN entitled, "Tragedy of the Data Commons." For those following the current privacy debates, it is must reading since it points out a simple truism: increased data privacy regulation could result in the diminution of many beneficial information flows.

Cutting against the grain of modern privacy scholarship, Yakowitz argues that "The stakes for data privacy have reached a new high water mark, but the consequences are not what they seem. We are at great risk not of privacy threats, but of information obstruction." (p. 58) Her concern is that "if taken to the extreme, data privacy can also make discourse anemic and shallow by removing from it relevant and readily attainable facts." (p. 63) In particular, she worries that "The bulk of privacy scholarship has had the deleterious effect of exacerbating public distrust in research data."

Yakowitz is right to be concerned. Access to data and broad data sets that include anonymized profiles of individuals is profound importantly for countless sectors and professions: journalism, medicine, economics, law, criminology, political science, environmental sciences, and many, many others. Yakowitz does a brilliant job documenting the many "fruits of the data commons" by showing how "the benefits flowing from the data commons are indirect but bountiful." (p. 5) This isn't about those sectors making money. It's more about how researchers in those fields use information to improve the world around us. In essence, more data = more knowledge. If we want to study and better understand the world around us, researchers need access to broad (and continuously refreshed) data sets. Overly restrictive privacy regulations or forms of liability could slow that flow, diminish or weaken research capabilities and output, and leave society less well off because of the resulting ignorance we face.

Consequently, her paper includes a powerful critique of the "de-anonymization" and "easy re-identification" fears set forth by the likes of Paul Ohm, Arvind Narayanan, Vitaly Shmatikov, and other computer scientists and privacy theorists. These scholars have suggested that because the slim possibility exists of some individuals in certain data sets being re-identified even after their data is anonymized, that fear should trump all other considerations and public policy should be adjusted accordingly (specifically, in the direction of stricter privacy regulation / tighter information controls).

She continues on to brilliantly dissect and counter this argument that the privacy community has put forward, which is tantamount to a 'it's better to be safe than sorry' mentality. "If public policy had embraced this expansive definition of privacy — that privacy is breached if somebody in the database could be reidentified by anybody else using special non-public information — dissemination of data would never have been possible," she observes.

If anything, Yakowitz doesn't go far enough here. In my recent filing to the Federal Trade Commission in their "Do Not Track" proceeding, I noted that we are witnessing the rise of a "Privacy Precautionary Principle" that threatens to block many forms of digital progress through the application of a "Mother, May I" form of prophylactic information regulation. Basically, you won't be allowed to collect many forms of information / data until receiving permission from some agency, or at least an assurance that crushing liability won't be imposed later if you do. Such a Privacy Precautionary Principle will have troubling implications for the future of the Internet and free speech (especially press freedoms) as it essentially threatens to stop digital progress in its tracks based on conjectural fears about data collection / aggregation. But it's effect will be even more deleterious on the research community. Yakowitz brilliantly addresses this danger in her paper when she notes:

Privacy advocates tend to play the role of doom prophets — their predictions of troubles are ahead of their times. Convinced of the inevitability of the harms, privacy scholars are dissatisfied with reactive rather than proactive, regulation. Reactive legislation gets a bad wrap, but it is the most appropriate course for anonymized research data. Legislation inhibiting the dissemination of research data would have guaranteed drawbacks today for the research community and to society at large. We should find out whether reidentification risk materializes before taking such drastic measures. (p. 48-9)

Quite right. The application of a Privacy Precautionary Principle would have radical ramifications for the research community and, then, society more generally. It is essential, therefore, that policymaker think carefully about calls for sweeping privacy controls and, at a minimum, conduct a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis of any proposed regulations before shutting off the flow of information online.

But we should realize that there will never be black-and-white answers to some of these questions. Using the example of Google Flu Trends, Yakowitz notes that it is often impossible to predict in advance what data or data sets are "socially valuable" in an effort to determine preemptively what should be allowed vs. restricted:

Google Flu Trends exemplifies why it is not possible to come to an objective, prospective agreement on when data collection is sufficiently in the public's interest and when it is not. Flu Trends is an innovative use of data that was not originally intended to serve an epidemiological purpose. It makes use of data that, in other contexts, privacy advocates believe violate Fair Information Practices. This illustrates a concept understood by data users that is frequently discounted by the legal academy and policymakers: some of the most useful, illuminating data was originally collected for a completely unrelated purpose. Policymakers will not be able to determine in advance which data resources will support the best research and make the greatest contributions to society. To assess the value of research data, we cannot cherry-pick between "good" and "bad" data collection. (p. 11-12)

Importantly, Yakowitz also notes that data access is a powerful accountability mechanism. "A thriving public data commons serves the primary purpose of facilitating research, but it also serves a secondary purpose of setting a data-sharing norm so that politically-motivated access restrictions will stick out and appear suspect." (p. 17) In essence: the more data, the more chances we can hold those around us more accountable and check their power. (David Brin also made this point brilliantly in his provocative 1998 book, The Transparent Society, in which he noted that it was access to information and openness to data flows that put the "light" in Enlightenment!)

Yakowitz feels so passionately about openness and access to data that she goes on to propose a safe harbor to shield data producers / aggregators from liability if they follow a set of reasonable anonymization protocols. She compares this to the sort of protection that the First Amendment offers to journalists as they seek to unearth and disseminate important truthful information of public interest. She argues that aggregated research data serves a similar purpose because of the myriad ways it benefits society and, therefore, those who produce and aggregate it deserve some protection from punishing liability. (I thought she might also reference CDA Sec. 230 here as well, but she didn't. Sec. 230 immunizes online intermediaries from potentially punishing forms of liability for the content sent over their digital networks. The purpose is to ensure that information continues to flow across digital networks by avoiding the "chilling effect" that looming liability would have on intermediaries and online discourse. See my essays: 1, 2, 3, 4.)

Anyway, read the entire Yakowitz paper. It deserves serious attention. It could really shake up the current debate over privacy regulation.

Patri Friedman on seasteading

On this week's podcast, Patri Friedman, executive director and chairman of the board of The Seasteading Institute, discusses seasteading. Friedman discusses how and why his organization works to enable floating ocean cities that will allow people to test new ideas for government. He talks about advantages of starting new systems of governments in lieu of trying to change existing ones, comparing seasteading to tech start-ups that are ideally positioned to challenge entrenched companies. Friedman also suggests when such experimental communities might become viable and talks about a few inspirations behind his "vision of multiple floating Hong Kongs": intentional communities, Burning Man, and Ephemerisle.

Related Links

Seasteading: Institutional Innovation on the Open Ocean, by Friedman and Brad Taylor (pdf)

"Live Free or Drown: Floating Utopias on the Cheap," Wired

"Homesteading on the High Seas," Reason

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

March 21, 2011

Again, Most Video Games Are Not Violent

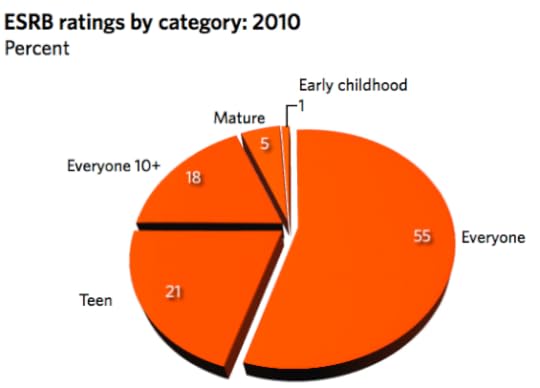

Five years ago this month, I penned a white paper on "Fact and Fiction in the Debate over Video Game Regulation" that I have been meaning to update ever since but just never seem to get around to it. One of the myths I aimed to debunk in the paper was the belief that most video games contain intense depictions of violence or sexuality. This argument drives many of the crusades to regulate video games. In my old study, I aggregated several years worth of data about video game ratings and showed that the exact opposite was the case: the majority of games sold each year were rating "E" for everyone or "E10+" (Everyone 10 and over) by the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB).

Five years ago this month, I penned a white paper on "Fact and Fiction in the Debate over Video Game Regulation" that I have been meaning to update ever since but just never seem to get around to it. One of the myths I aimed to debunk in the paper was the belief that most video games contain intense depictions of violence or sexuality. This argument drives many of the crusades to regulate video games. In my old study, I aggregated several years worth of data about video game ratings and showed that the exact opposite was the case: the majority of games sold each year were rating "E" for everyone or "E10+" (Everyone 10 and over) by the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB).

Thanks to this new article by Ars Technica's Ben Kuchera, we know that this trend continues. Kuchera reports that out of 1,638 games rated by the ESRB in 2010, only 5% were rated "M" for Mature. As a percentage of top sellers, the percentage of "M"-rated games is a bit higher, coming in at 29%. But that's hardly surprising since there are always a few big "M"-rated titles that are the power-sellers among young adults each year. Still, most of the best sellers don't contain extreme violence or sexuality.

The primary criticism of these findings is that (1) violence is subjective and, therefore, (2) you can't trust the industry to accurately rate it's own content. Plus, (3) kids still see a lot of violent content, anyway.

Violence certain is subjective, as I've discussed here numerous times before. And it's also true that the ESRB was created by the video game industry as a self-regulatory body to rate the content of games. That doesn't mean the ratings are deceptive, however. Indeed, polls have generally shown parental satisfaction with the system, and when you compare ESRB ratings to independent rating schemes (like Common Sense Media's) you see largely the same sort of labels and age warnings being affixed to various titles. Sure, there are small differences at the margin, but they tend to be legitimately difficult cases (ex: how to rate a boxing game when the real-world equivalent is an actual sporting event that can be quite violent at times).

I'm never quite sure what to make of the third argument: that kids will still see a lot of violent games. If that's true, is it the video game industry's fault? Should no violent games be released because some kids might still find a way to see or play them? That's an intolerable solution in a free society that treasures the First Amendment, of course. Moreover, it really comes back to parental choice and responsibility. When games cost $20 to $60 bucks a pop, it's hard to even figure out how junior gets his hands on some of these games without Mom or Dad knowing. Moreover, even getting the game console into the house requires a significant outlay of cash, and even then, parents are prompted to set up parental controls when they get some of these devices. (All of them contain sophisticated controls but the initial configuration is slightly different on each).

In my opinion, the combination of the excellent ESRB ratings and the outstanding current generation console controls has resulted in one of the great user-empowerment success stories of modern times. Parents have been given valuable information about games to make decisions regarding what is appropriate for their families and then also given the tools to take action on that information by establishing console settings in line with their household values. Sounds like an ideal state of affairs to me. And, better yet, as the data above illustrate, parents don't even have to worry about most games being inappropriate for kids!

Now, excuse me while I get back to playing "Plants vs. Zombies" on the XBox with my kids! What a great game that is. The whole family is loving it.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower