Adam Thierer's Blog, page 141

March 3, 2011

Progress on Spectrum Inventory…if Only Illusory

I've written posts today for both CNET and Forbes on legislation introduced yesterday by Senators Olympia Snowe and John Kerry that would require the FCC and NTIA to complete inventories of existing spectrum allocations. These inventories were mandated by President Obama last June (after Congress failed to pass legislation), but got lost at the FCC in the net neutrality armageddon.

I've written posts today for both CNET and Forbes on legislation introduced yesterday by Senators Olympia Snowe and John Kerry that would require the FCC and NTIA to complete inventories of existing spectrum allocations. These inventories were mandated by President Obama last June (after Congress failed to pass legislation), but got lost at the FCC in the net neutrality armageddon.

Everyone believes that without relatively quick action to make more spectrum available, the mobile Internet could seize up. Given the White House's showcasing of wireless as a leading source of new jobs, investment, and improved living conditions for all Americans, both Congress and President Obama, along with the FCC and just about everyone else, knows this is a crisis that must be avoided.

Indeed, the National Broadband Plan estimates conservatively that mobile users will need 300-500 mhz of new spectrum over the next 5-10 years.

The last major auction, however, conducted in 2008 for analog spectrum given up by broadcasters in the Digital TV transition, was only 62 mhz. And that process took years.

So while auctions–perhaps of more of the over-the-air allocations–could help, it can't be the silver bullet. We'll need creative solutions–including technology to make better use of existing allocations, spectrum sharing, release of government-held frequencies.

But why not start by figuring out who has spectrum now, and see if it's really being put to the use that's in the best interests of American consumers, who are ultimately the owners of the entire range.

You can guess why some people would prefer not to open that dialogue.

And perhaps why something so obvious as an inventory doesn't already exist.

March 2, 2011

Free the Toll-Free Numbers

Toll-free number allocation remains one of the last vestiges of telecom's monopoly era. Unlike Internet domain names, there is no organized way of requesting, registering, reserving, purchasing 800, 888, 877, 866, or the newly available 855 numbers, the five prefixes that currently designate toll-free service. If you're lucky or creative enough, you can visit any number of sites (just Google "855 toll free code") and the number you request might be available. If not, you're SOL.

That's because the toll-free number regulation regime is cumbersome, opaque and bureaucratic. And while the FCC technically prohibits the warehousing, hoarding, transfer and sale of toll-free numbers, enforcement is difficult and inconsistent.

The North American Numbering Council, a federal advisory committee that was created to advise the FCC on numbering issues will be meeting in Washington March 9. On the agenda will be discussion on whether to go forward with exploring market mechanisms that can be applied to toll-free number assignment.

It's an idea worth pursuing. It is clear that some toll-free numbers have equity value, especially when they can bolster a brand identity or be easily remembered. 1-800-SOUTHWEST, 1-800-FLOWERS are two examples.

Yet right now, the toll-free numbering pool is a vast and unruly commons that recognizes no difference in value between a desirable mnemonic and a generic sequence of digits. Numbers are assigned on a first-come, first-served basis. End users can request a specific number, but they can get it only if it is available from the pool. Under the current rules, they cannot offer to buy the number from its current user. Nor can the user of 1-800-555-2665, which alphanumerically translates to both 1-800-555-BOOK and 1-800-555-COOK, put the number up for auction to see who will pay more, the bookstore or cooking school.

In fact, there is really no accurate way to determine the party to whom any toll-free number has been assigned. Unlike Internet domain names—or automobiles for that matter—there is no central registry linking a toll-free number with a specific end-user. With the Internet, the WHOIS database can at least tell you the organization or agent for the domain name in question. Any state department of motor vehicles can verify car ownership through VIN and license plate numbers. With a particular toll-free number, however, whoever is using it at the moment can lay claim to it. As Jay Carpenter, president of 1-800-American Free Trade Association (1-800-AFTA), a trade group pushing for adoption of market models in toll-free numbering, told me, it's like basing car ownership on the basis of who had the keys.

Despite the FCC rule that prohibits sale or transfer of toll-free numbers, enforcement is woefully inconsistent. For one, toll-free numbers are routinely transferred when businesses are bought or sold. Take United Airlines, which last year was purchased by Continental Airlines but, as part of the deal, kept the United name. Despite the sale, the merged company is still using 1-800-UNITED-1 and other toll-free numbers. ITT sold Sheraton Hotels to Starwood Resorts in 1998, yet Sheraton's famously melodic toll-free number, 800-325-3535, which this web site says dates from 1969, still gets you a reservation.

Carpenter said his research over the years has unearthed SEC filings where companies openly state that they have purchased specific toll-free numbers. He also believes a gray and black market for toll-free numbers has existed for some time.

Furthermore, while the FCC officially eschews the notion that some numbers may be more valuable that others, when it opened the 888 toll free prefix, it allowed owners of certain 800 numbers, such as 1-800-FLOWERS, to reserve the same numbers in the 888 codes. This decision seems to fly in the face of its first-come, first-served and no warehousing policies.

It's time for the government to admit what everybody knows already–that there is considerable value locked up in toll-free numbers and that consumers, businesses, and even government programs can benefit if this value were unleashed.

Market mechanisms have already been applied with great success to spectrum allocation and domain name assignment. Market pricing would direct resources to the party who can make best and most effective use of it. Market signals would be established. Opaque transactions and arbitrage would be driven out. The rate of toll-free number depletion, now at about 100,000 a week according to 1-800-AFTA, would be slowed considerably. Meanwhile, what was once a cost center for the government would become a potential revenue stream. 1-800-AFTA suggests a supply-and-demand mechanism for toll-free number allocation could be channeled into the Universal Service Fund.

What's more, it's been done. Australia's Telstra has created both a primary and secondary market for toll-free numbers. Ownership can be verified through registration. Transactions are brokered through trusted entities.

A market mechanism can be phased in, starting with the creating of an open database for toll-free number registration, an initiative that may not even require FCC action. Secondary market mechanisms can be developed, allowing transfer, sale and exchange of numbers. A primary market model can be drawn from the Australia example or the other models already noted. Certain use rights, such as those pertaining to existing trademarks and branding, could be protected from poaching and squatting.

Finally, there's the opportunity for greater innovation if Internet and IP networking functionality can be integrated more seamlessly with telephone numbering. Unified communications—the efficient merger of phone, wireless, email and web access, which stands to have great benefits in public safety and commerce–would be easier and less expensive to implement. More information and models can be found in this white paper 1-800-AFTA prepared for the NANC.

The only reason the current system numbering system exists is legacy inertia. If starting from scratch today, no one would design a toll-free regime. The ICANN approach to domain names speaks to that. Geography and carrier mean little to number assignment anymore. It's time to get past the mechanisms of yesteryear and free the toll-free numbers.

March 1, 2011

TLFers Attending Two Important Sec. 230 / Net Liability Events in CA This Week

This week I will be attending two terrific conferences on Sec. 230 and Internet intermediary liability issues. On Thursday, the Stanford Technology Law Review hosts an all-day event on "Secondary and Intermediary Liability on the Internet" at the Stanford Law School. It includes 3 major panels on intermediary liability as it pertains to copyright, trademark, and privacy. On Friday, the amazing Eric Goldman and his colleagues at the Santa Clara Law School's High Tech Law Institute host an all-star event on "47 U.S.C. § 230: a 15 Year Retrospective." Berin Szoka and Jim Harper will also be attending both events (Harper is speaking at Stanford event) and Larry Downes will be at the Santa Clara event. So if you also plan to attend, come say 'Hi' to us. We don't bite! (We have, however, been known to snarl.)

In the meantime, down below, I just thought I would post a few links to the many things we have said about Section 230 and online intermediary liability issues here on the TLF in the past as well as this graphic depicting some of the emerging threats to Sec. 230 from various proposals to "deputize the online middleman." As we've noted here many times before, Sec. 230 is the "cornerstone of Internet freedom" that has allowed a "utopia of utopias" to develop online. It would be a shame if lawmakers rolled back its protections and opted for an onerous new legal/regulatory approach to handling online concerns. Generally speaking, education and empowerment should trump regulation and punishing liability.

Further Reading from the TLF

Web 2.0, Section 230, and Nozick's "Utopia of Utopias" – 1/13/09

The AutoAdmit Case and the Future of Sec. 230 – 2/16/09

The Future of Sec. 230 and Online Immunity: My Debate with Harvard's John Palfrey – 5/6/2009

Emerging Threats to Section 230 – 5/14/09

Great Summary of Section 230 – 6/28/09

Section 230: The Cornerstone of Internet Freedom – 8/18/09

Cyberbullying Hearing Yesterday: Education, not Criminalization or Intermediary Deputization – 10/1/09

Eric Goldman on New Threats to Sec. 230 – 3/27/10

GetUnvarnished.com: Should We Allow User Feedback about Personal Reputation? – 4/6/10

An update on the evolving e-book market: Kindle edition (pun intended)

[Cross-posted at Truth on the Market]

A year ago I wrote about the economics of the e-book publishing market in the context of the dispute between Amazon and some publishers (notably Macmillan) over pricing. At the time I suggested a few things about how the future might pan out (never a god idea . . . ):

And that's really the twist. Amazon is not ready to be a platform in this business. The economic conditions are not yet right and it is clearly making a lot of money selling physical books directly to its users. The Kindle is not ubiquitous and demand for electronic versions of books is not very significant–and thus Amazon does not want to take on the full platform development and distribution risk. Where seller control over price usually entails a distribution of inventory risk away from suppliers and toward sellers, supplier control over price correspondingly distributes platform development risk toward sellers. Under the old system Amazon was able to encourage the distribution of the platform (the Kindle) through loss-leader pricing on e-books, ensuring that publishers shared somewhat in the costs of platform distribution (from selling correspondingly fewer physical books) and allowing Amazon to subsidize Kindle sales in a way that helped to encourage consumer familiarity with e-books. Under the new system it does not have that ability and can only subsidize Kindle use by reducing the price of Kindles–which impedes Amazon from engaging in effective price discrimination for the Kindle, does not tie the subsidy to increased use, and will make widespread distribution of the device more expensive and more risky for Amazon.

This "agency model," if you recall, is one where, essentially, publishers, rather than Amazon, determine the price for electronic versions of their books sold via Amazon and pay Amazon a percentage. The problem from Amazon's point of view, as I mention in the quote above, is that without the ability to control the price of the books it sells, Amazon is limited essentially to fiddling with the price of the reader–the platform–itself in order to encourage more participation on the reader side of the market. But I surmised (again in the quote above), that fiddling with the price of the platform would be far more blunt and potentially costly than controlling the price of the books themselves, mainly because the latter correlates almost perfectly with usage, and the former does not–and in the end Amazon may end up subsidizing lots of Kindle purchases from which it is then never able to recoup its losses because it accidentally subsidized lots of Kindle purchases by people who had no interest in actually using the devices very much (either because they're sticking with paper or because Apple has leapfrogged the competition).

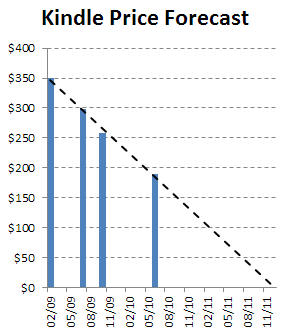

It appears, nevertheless, that Amazon has indeed been pursuing this pricing strategy. According to this post from Kevin Kelly,

John Walkenbach noticed that the price of the Kindle was falling at a consistent rate, lowering almost on a schedule. By June 2010, the rate was so unwavering that he could easily forecast the date at which the Kindle would be free: November 2011.

There's even a nice graph to go along with it:

So what about the recoupment risk? Here's my new theory: Amazon, having already begun offering free streaming videos for Prime customers, will also begin offering heavily-discounted Kindles and even e-book subsidies–but will also begin rescinding its shipping subsidy and otherwise make the purchase of dead tree books relatively more costly (including by maintaining less inventory–another way to recoup). It will still face a substantial threat from competing platforms like the iPad but Amazon is at least in a position to affect a good deal of consumer demand for Kindle's dead tree competitors.

For a take on what's at stake (here relating to newspapers rather than books, but I'm sure the dynamic is similar), this tidbit linked from one of the comments to Kevin Kelly's post is eye-opening:

If newspapers switched over to being all online, the cost base would be instantly and permanently transformed. The OECD report puts the cost of printing a typical paper at 28 per cent and the cost of sales and distribution at 24 per cent: so the physical being of the paper absorbs 52 per cent of all costs. (Administration costs another 8 per cent and advertising another 16.) That figure may well be conservative. A persuasive looking analysis in the Business Insider put the cost of printing and distributing the New York Times at $644 million, and then added this: 'a source with knowledge of the real numbers tells us we're so low in our estimate of the Times's printing costs that we're not even in the ballpark.' Taking the lower figure, that means that New York Times, if it stopped printing a physical edition of the paper, could afford to give every subscriber a free Kindle. Not the bog-standard Kindle, but the one with free global data access. And not just one Kindle, but four Kindles. And not just once, but every year. And that's using the low estimate for the costs of printing.

More Confusion about Internet "Freedom"

Nate Anderson of Ars Technica has posted an interview with Sen. Al Franken (D-MN) about Defining Internet "Freedom". Neither Sen. Franken nor Mr. Anderson ever get around to defining that term in their exchange, but the clear implication from the piece is that "freedom" means freedom for the government to plan more and for policymakers to more closely monitor and control the Internet economy. The clearest indication of this comes when Sen. Franken repeats the old saw that net neutrality regulation is "the First Amendment issue of our time."

As a lover of liberty, I find this corruption of language and continued debasement of the term "freedom" to be extremely troubling. The thinking we see at work here reflects the ongoing effort by many cyber-progressives (or "cyber-collectivists," as I prefer to call them) to redefine Internet freedom as liberation from the supposed tyranny of the marketplace and the corresponding empowerment of techno-cratic philosopher kings to guide us toward a more enlightened and noble state of affairs. We are asked to ignore our history lessons, which teach us that centralized planning and bureaucracy all too often lead to massively inefficient outcomes, myriad unforeseen unintended consequences, bureaucratic waste, and regulatory capture. Instead, we are asked to believe that high-tech entrepreneurs are the true threat to human progress and liberty. They are cast as nefarious villains and their innovations, we are told, represent threats to our "freedom." We even hear silly comparisons likening innovators like Apple to something out of George Orwell's 1984.

To be clear, I am not saying everything will be sunshine and roses in a free information marketplace. Mistakes will be made by those innovators and there will even be short-term spells of what many would regard as excessive corporate market power. The question is how much faith we should place in central planners, as opposed to evolutionary market forces, to solve that problem. Those who truly love liberty and real human freedom would have more patience with competition and technological change and be willing to see how things play out. In other words, "market failures" and "code failures" are ultimately better addressed by voluntary, spontaneous, bottom-up responses than by coercive, top-down approaches.

The decisive advantage of the market-driven approach is nimbleness. It is during what some might regard as a market's darkest hour when some of the most exciting disruptive technologies and innovations develop. People don't sit still; they respond to incentives, including short spells of apparently excessive private power. But they can only do so if they are truly free from artificial constraint from government forces who, inevitably, are always one or two steps behind fast-moving technological developments. Thus, we shouldn't allow the cyber-collectivists to sell us their version of "freedom" in which markets are instead constantly reshaped through incessant regulatory interventions. That isn't freedom, it's tyranny.

More insulting to me is the continued repetition of this balderdash about how Net neutrality is "the First Amendment issue of our time." As I've pointed out before here before in my essay on "Net Neutrality Regulation & the First Amendment," the Internet's First Amendment is the First Amendment, not some new, top-down, heavy-handed regulatory regime that puts Federal Communications Commission bureaucrats in control of the Digital Economy. America's Founding Fathers intended the First Amendment to serve as a shield from government encroachment on our liberties, not as a sword for government to wield to reshape markets and speech according to the whims of five unelected bureaucrats at the FCC. Anyone who suggests otherwise is engaging in revisionist history of the highest order.

Sadly, however, countless people seem to buy into this twisted vision of "Internet freedom" today. They stand ready to empower the techno-planners, to call in the code cops, and to roll out the tech pork barrel in their invitation to Washington to give the Digital Economy a great big bear hug.

You can call this vision many things, but pro-freedom is not one of them. As Berin Szoka and I have argued here in the past, true "Internet freedom" is freedom from state action; not freedom for the State to reorder our affairs to supposedly make certain people or groups better off or to improve some amorphous "public interest" — an all-to convenient facade behind which unaccountable elites can impose their will on the rest of us.

If you stand for liberty, the choice of which conception of "Net freedom" to embrace is simple.

Jim Harper on identification systems

On the podcast this week, Jim Harper, director of information policy studies at the Cato Institute, discusses identification systems. He talks about REAL ID, a national uniform ID law passed in 2005 that states have contested, and NSTIC, a more recent government proposal to create an online identification "ecosystem." Harper discusses some of the hidden costs of establishing national identification systems and why doing so is not a proper role of government. He also comments on the reasoning behind national ID proposals and talks about practical, beneficial limits to transparency.

Related Links

"REAL ID Is Still Dead, But It Is Walking Dead," by Harper

"Cyber-Security Czar Defends Government Role," the Wall Street Journal

"Why You Should Trust Apple More Than the U.S. Commerce Dept. With Your Universal Online ID," Fast Company

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

February 28, 2011

Sen. Klobuchar's Child Safety Hearing: Bring Your Own Salt!

The Senate Judiciary Committee will hold a hearing on March 2 entitled "Helping Law Enforcement Find Missing Children." While this is just about the most popular topic for a hearing one could imagine, and I'm as much in favor of finding missing children as anyone, I'm a little concerned to see Sen. Klobuchar presiding over a hearing that could lead to new proposals for Internet regulation. As a former prosecutor, it certainly makes sense for her to have taken over Judiciary's Subcommittee on Administrative Oversight and the Courts. But she's engaged in blatant fear-mongering about online child safety in the past, so I think it's fair to say that anyone listening to this hearing should take it with at least a grain of salt—especially if the hearing calls for new mandates for internet intermediaries to address a supposed "crisis."

Last summer, as I noted, the Senator sent an angry letter to Facebook demanding the site require "a prominent safety button or link on the profile pages of users under the age of 18″ that included the following:

Recent research has shown that one in four American teenagers have been victims of a cyber predator.

The letter didn't actually cite anything, so it's not clear what research she was relying on, as I noted:

The 25% statistic is particularly incendiary, suggesting a nationwide cyber-predation crisis—perhaps leading the public to believe 8 or 9 million teens have been lured into sexual encounters offline. Perhaps the Senator considers every cyber-bully a cyber predator—which might get to the 25% number. But there are two serious problem with that moral equivalence.

First, to equate child predation with peer bullying is to engage in a dangerous game of defining deviancy down. Predation and bullying are radically different things. The first (sexual abuse) is a clear and heinous crime that can lead to long-term psychological damage. The second might be a crime in certain circumstances, but generally not. And it is even less likely to be a crime when it occurs among young peers, which research shows constitutes the vast majority of cases. As Adam Thierer and I noted in our Congressional testimony last year, there are legitimate concerns about cyberbullying, but it's something best dealt with by parents and schools rather than prosecutors (like Klobuchar in her pre-Senate career).

I went on to cite summaries of the statistics on actual child predation rates—not even close to Sen. Klobuchar's figure. If she had made these unsubstantiated claims in an academic paper, she would have been roundly criticized by her peers in the "reality-based community." Yet in Congress, a willingness to sensationalize seems to have little consequence—other than a promotion to a larger bully pulpit from which to harangue. With her experience, she could be an an excellent Chairman and leader on these issues. I only hope it starts with a commitment to accuracy, lest unsubstantiated concerns about child safety lead to bad policy-making while real and substantiated concerns are under-emphasized.

Apple, Antitrust, and the FTC

[Cross-posted at Truth on the Market]

Antitrust investigators continue to see smoke rising around Apple and the App Store. From the WSJ:

For starters, subscriptions must be sold through Apple's App Store. For instance, a magazine that wants to publish its content on an iPad cannot include a link in an iPad app that would direct readers to buy subscriptions through the magazine's website. Apple earns a 30% share of any subscription sold through its App Store. …

A federal official confirmed to The Washington Post that the government is looking at Apple's subscription service terms for potential antitrust issues but said there is no formal investigation. Speaking on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to comment publicly, the official said that the government routinely tracks new commercial initiatives influencing markets.

Investigators certainly suspect Apple of myriad antitrust violations; there is even some absurd talk about breaking up Apple. There is definitely smoke — but is there fire?

The most often discussed bar to an antitrust action against Apple is the one many regulators simply assume into existence: Apple must have market power in an antitrust-relevant market. While Apple's share of the smartphone market is only 16% or so, its share of the tablet computing market is much larger. The WSJ, for example, reports that Apple accounts for about three-fourths of tablet computer sales. I've noted before in the smartphone context that this requirement should not be consider a bar to FTC suit, given the availability of Section 5; however, as the WSJ explains, market definition must be a critical issue in any Apple investigation or lawsuit:

Publishers, for example, might claim that Apple dominates the market for consumer tablet computers and that it has allegedly used that commanding position to restrict competition. Apple, in turn, might define the market to include all digital and print media, and counter that any publisher not happy with Apple's terms is free to still reach its customers through many other print and digital outlets.

One must conduct a proper, empirically-grounded analysis of the relevant data to speak with confidence; however, it suffices to say that I am skeptical that tablet sales would constitute a relevant market.

Meanwhile, Google demonstrates the corrective dynamics of markets. New entry during an investigation period can influence agencies' decision-making — as it should; Google has recently offered a new service, OnePass, which would allow publishers to keep up to 90% of subscription revenue. It is unknown — and perhaps unknowable — which business model is "correct;" perhaps both are preferable in their individual contexts. It appears there is emerging, significant competition in this space, of which regulators should take note.

Finally, in light of Geoff's recent post, it is also worth discussing whether Tim Wu's recent appointment to the Commission impacts the likelihood of a suit against Apple. Geoff thinks it means a likely suit against Google; Professor Wu might bring similar implications for Apple — after all, Professor Wu has described Apple as the company he most fears. I have no doubt that Professor Wu will spend a good deal of his time at the Commission dealing with issues surrounding both Google and Apple, policy issues concerning both, and potential antitrust theories surrounding business practices such as Apple's subscription model. I am skeptical, however, that his presence changes the actual likelihood of a suit: Section 2 law remains a substantial obstacle. The real value of his creative thinking will be in generating Section 5 claims surrounding these business arrangements — where the Commission must demonstrate substantially less onerous requirements and where the Commission operates within greater legal ambiguities. In this light, will Professor Wu bring such an aggressive stance to Section 5 so as to make the difference between an Apple challenge or not? I doubt it — the Commission has already expressed an interpretation of Section 5 that I find unjustifiably aggressive. The Commission needs no assistance in leveraging Section 5 to intervene in high-tech contexts: just ask Intel.

Predictions are a rough business: that caveat aside, I continue to believe the FTC will file against Apple — and because of the obvious (and likely impassable) hurdles under Section 2, I believe the eventual complaint will be a bare Section 5 suit.

February 27, 2011

More Challenges to the Lessig-Zittrain-Wu Thesis

Writing over at Forbes, Bret Swanson notes that the progression of information technology history isn't going so well for those Net pessimists who, not so long ago, predicted that the sky was set to fall on consumers and that digital innovation was dying. Specifically, Swanson addresses the theories set forth by cyberlaw professors Lessig, Zittrain, and Wu (among others), whose theories about "perfect control," the death of "generativity," and the rise of the "master switch," I have addressed here many time before. [See this compendium of TLF essays discussing "Problems with the Lessig-Zittrain-Wu Thesis."] Swanson summarizes what went wrong with their gloomy Chicken Little theories and their predictions of the coming cyber end-times:

As the cloud wars roar, the cyber lawyers simmer. This wasn't how it was supposed to be. The technology law triad of Harvard's Lawrence Lessig and Jonathan Zittrain and Columbia's Tim Wu had a vision. They saw an arts and crafts commune of cyber-togetherness. Homemade Web pages with flashing sirens and tacky text were more authentic. "Generativity" was Zittrain's watchword, a vague aesthetic whose only definition came from its opposition to the ominous "perfect control" imposed by corporations dictating "code" and throwing the "master switch."

In their straw world of "open" heros and "closed" monsters, AOL's "walled garden" of the 1990s was the first sign of trouble. Microsoft was an obvious villain. The broadband service providers were of course dangerous gatekeepers, the iPhone was too sleek and integrated, and now even Facebook threatens their ideal of uncurated chaos. These were just a few of the many companies that were supposed to kill the Internet. The triad's perfect world would be mostly broke organic farmers and struggling artists. Instead, we got Apple's beautifully beveled apps and Google's intergalactic ubiquity. Worst of all, the Web started making money.

Swanson goes on to argue that, despite all the hang-wringing we're heard from this triumvirate and their many, many disciples in the academic and regulatory activist world, things just keep getting more innovative, more generative, and yes, even more "open." As I noted in my book chapter on "The Case for Internet Optimism, Part 2 – Saving the Net From Its Supporters" as well as my recent Reason magazine essay on "The Rise of Cybercollectivism," scholars like Lessig, Zittrain, and Wu:

seem trapped in what Virginia Postrel labeled the "stasis mentality" in her 1998 book The Future and Its Enemies. They want an engineered world that promises certain outcomes. They are prone to taking snapshots of market activity and suggesting that those temporary patterns are permanent disasters requiring immediate correction. (Recall Lessig's fear of AOL, which once had 25 million subscribers who were willing to pay $20 a month to get a guided tour of the Internet, but which ignored the rise of search and social networks at its own peril. It didn't help that the company's disastrous merger with Time Warner ended with over $100 billion in shareholders losses and an eventual divorce.) The better approach is what Postrel termed dynamism: "a world of constant creation, discovery, and competition." Dynamism places heavy stress on the heuristic and believes there is inherent value in an experimental, evolutionary process, no matter how messy it can be in practice.

Moreover, I think these scholars fail to appreciate a point I tried to make in my essay earlier this week on "Techno-Panic Cycles":

many people overlook the importance of human adaptability and resiliency. The amazing thing about humans is that we adapt so much better than other creatures. When it comes to technological change, resiliency is hard-wired into our genes. … We learn how to use the new tools given to us and make them part of our lives and culture.

Just as that is true for social or speech-related technology developments, so too for economic developments. People don't sit still — consumers, coders, new companies, etc. — they respond to marketplace developments and incentives. They seek out new ways of doing things. They hack. They crack. They code. They are always looking to build or buy a better mousetrap. And when they find them, they don't just settle for the state-of-the-art ; they expect everything to be reworked and re-launched constantly with revisions and improvements at every level. For example, the original Verizon Droid 1 that I got just 15 months ago now feels like an antique compared to the latest devices on the market. I am dying to upgrade to a new model, which will give me more processing power, more storage, more high-speed access, more apps, more of everything. I am so pampered by the pace of progress that expect and demand it!

No doubt, the ivory tower worrywarts will continue to grumble about how their techno-cratic philosopher king approach would supposedly make the world even more innovative and consumer-friendly, if only we adopted a healthy dose of top-down planning and centralized direction. But we need to ask ourselves whether their prescription for planning can really beat the track record that is unfolding on a daily basis right before our eyes.

February 26, 2011

Today's Titans, Tomorrow's Bygones

Newsweek has a great single-page spread on Who's Eating Your Lunch? about the topsy-turvy tech sector, illustrating beautifully our argument that the relentless force of disruptive innovation is the best remedy for incumbent power:

AOL has been forced to become a content company and team up with Huffington Post now that we all get our Internet from the cable guy. Meanwhile, MySpace is sporting a FOR SALE sign and Borders is facing Chapter 11, while their competitors—Facebook and Amazon—brag of record growth and profits. Now as ever, success in business belongs to those ready to eat the lunch of a complacent rival—and the cycle of life completes itself as potential competitors of the future hit the scene. Here's a guide to some of the business world's biggest recent reversals of fortune.

Check it out here.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower