Adam Thierer's Blog, page 144

February 15, 2011

Is Twitter a utility like water?

Speaking at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona today, Twitter CEO Dick Costolo said he wants the service to become as ubiquitous and simple as tap water. But he should be careful what he wishes for.

Search Engine Land is already asking, "Twitter As Utility, Like Running Water?" The thing about water is that it tends to be an indispensable natural monopoly, and therefore regulated. Twitter today controls access to its "firehose" of tweet data, but access to utilities like water is mandated open and prices are set by regulators.

As I discussed recently on the podcast with Danny Sullivan, some have already suggested Google should be treated like a utility and brought under a regime of "search neutrality." Harvard's danah boyd has been banging the "regulate Facebook as a utility" drum for quite some time. And Just today Wharton's Kevin Werbach put out a draft of his new law review article: "The Network Utility."

Of course, as I already mentioned, it's unsurmountable monopolies that should be regulated, and it would be a stretch to say that either Facebook or Twitter qualify. But I fear we'll be hearing more and more of this "utility" language in the near future.

Why are some states disproportionately taxing a service we want more people using?

A new report out this week in State Tax Notes shows the discriminatory way in which Federal, state and local governments treat their citizens who subscribe to wireless services — and according to CTIA that's about 93% of Americans.

Federal, state and local taxes and fees for wireless services topped an average of 16.3% in 2010. The highest combined rate was 16.85% in 2005. This far surpasses the average retail sales tax rate, which obviously varies by state.

Some blame can rest squarely on the shoulders of state or local officials who have targeted wireless services for a specific tax. The report points out a few examples:

Baltimore: increased its per-line tax from $3.50 per month to $4

Montgomery County, MD: increased its per-line tax from $2 to $3.50 per month

Olympia, WA: imposed a 9 percent telecommunications tax on top of the state-local combined sales tax of 8.5 percent

Chicago: imposed a 7 percent excise tax on wireless services on top of the state's 7 percent excise tax

Nebraska: imposes a local "utility" tax of up to 6.5 percent in addition to the 6.5 percent combined state-local sales tax

Tucson, AZ: increased its telecommunications license tax from 2 percent to 4 percent

But the Fed's Universal Service Fund (USF) fee is where the biggest increase has come of late. Increases in the Federal USF have added 0.9 percentage points to the rate since 2007, while state and local increases added just 0.2 percent. However, of concern as well is the rate at which wireless taxes/fees are increasing: almost three times as fast as other general sales tax increases.

I'm privileged enough to live in Washington state, where we impose 23.00% combined Federal,state and local taxes/fees on wireless customers. That's second highest in the nation. Granted, Washington state has one of the highest state+local combined sales tax in the nation according to the Tax Foundation, but the 17.95% state-local wireless rate is twice that of the state-local sales tax rate of 9%. What is the excuse for that?

Nebraska imposes the highest combined tax/fees on wireless at 23.69%. Lowest is Washington's neighbor to the south, Oregon, at 6.86% then Nevada at 7.13% and Idaho at 7.25%. Rounding out the top five of the worst are New York (22.83%), Florida (21.62%) and Illinois (20.90%).

So this brings up the debate of why are some government entities disproportionately taxing a service everyone agrees is vital to the health and future growth of our economy? CTIA says that fully one-quarter of households in the U.S. have ditched their landline phone in favor of wireless only or wireless + IP telephony (count this author among one of those).

Everyone from the Obama Administration on down is touting the future of wireless and mobile broadband as one we should heartily embrace. Examples of this include the FCC's recent Net Neutrality Order that exempts wireless carriers, the Administration's push for spectrum re-allocation, all the hullabaloo about 3G-4G-LtE and all the talk about increasing carrier's backhaul.

A recent Pew Internet poll highlighted that, for many people (and especially minorities), a mobile smartphone is the primary way they connect to the Internet. Now that many smartphones can be had for free with a contract, we have lowered the barrier to entry to things like social networking and search. No longer do you have to own a desktop or laptop, you just need to whip out the computer in your pocket and connect to a cell service or WiFi. Another Pew poll said that among "non-adopters" of broadband, 14% of them had accessed the Internet via their mobile phones.

For years the two main reasons that people state when it comes to explaining why they have not adopted broadband Internet are price and relevance. The non-adopters either can't afford, don't see the value in subscribing to broadband or think it's simply a waste of time. We can't do anything about the folks who think the Internet is a fad, but why make wireless services and mobile broadband even more expensive, especially if this type of service is so elastic?

Twenty-three states now impose a state-local wireless rate above 10%, which has become the unwritten but psychological barrier that we are seeing sales taxes creep towards.

Wireless services and customers shouldn't be exempted from paying any taxes or fees, but imposing a disproportionately higher tax rate on a service we as a society are pushing people to use more of is duplicitous.

Why are some states taxing a service we want more people using?

A new report out this week in State Tax Notes shows the discriminatory way in which Federal, state and local governments treat their citizens who subscribe to wireless services — and according to CTIA that's about 93% of Americans.

Federal, state and local taxes and fees for wireless services topped an average of 16.3% in 2010. The highest combined rate was 16.85% in 2005. This far surpasses the average retail sales tax rate, which obviously varies by state.

Some blame can rest squarely on the shoulders of state or local officials who have targeted wireless services for a specific tax. The report points out a few examples:

Baltimore: increased its per-line tax from $3.50 per month to $4

Montgomery County, MD: increased its per-line tax from $2 to $3.50 per month

Olympia, WA: imposed a 9 percent telecommunications tax on top of the state-local combined sales tax of 8.5 percent

Chicago: imposed a 7 percent excise tax on wireless services on top of the state's 7 percent excise tax

Nebraska: imposes a local "utility" tax of up to 6.5 percent in addition to the 6.5 percent combined state-local sales tax

Tucson, AZ: increased its telecommunications license tax from 2 percent to 4 percent

But the Fed's Universal Service Fund (USF) fee is where the biggest increase has come of late. Increases in the Federal USF have added 0.9 percentage points to the rate since 2007, while state and local increases added just 0.2 percent. However, of concern as well is the rate at which wireless taxes/fees are increasing: almost three times as fast as other general sales tax increases.

I'm privileged enough to live in Washington state, where we impose 23.00% combined Federal,state and local taxes/fees on wireless customers. That's second highest in the nation. Granted, Washington state has one of the highest state+local combined sales tax in the nation according to the Tax Foundation, but the 17.95% state-local wireless rate is twice that of the state-local sales tax rate of 9%. What is the excuse for that?

Nebraska imposes the highest combined tax/fees on wireless at 23.69%. Lowest is Washington's neighbor to the south, Oregon, at 6.86% then Nevada at 7.13% and Idaho at 7.25%. Rounding out the top five of the worst are New York (22.83%), Florida (21.62%) and Illinois (20.90%).

So this brings up the debate of why are some government entities disproportionately taxing a service everyone agrees is vital to the health and future growth of our economy? CTIA says that fully one-quarter of households in the U.S. have ditched their landline phone in favor of wireless only or wireless + IP telephony (count this author among one of those).

Everyone from the Obama Administration on down is touting the future of wireless and mobile broadband as one we should heartily embrace. Examples of this include the FCC's recent Net Neutrality Order that exempts wireless carriers, the Administration's push for spectrum re-allocation, all the hullabaloo about 3G-4G-LtE and all the talk about increasing carrier's backhaul.

A recent Pew Internet poll highlighted that, for many people (and especially minorities), a mobile smartphone is the primary way they connect to the Internet. Now that many smartphones can be had for free with a contract, we have lowered the barrier to entry to things like social networking and search. No longer do you have to own a desktop or laptop, you just need to whip out the computer in your pocket and connect to a cell service or WiFi. Another Pew poll said that among "non-adopters" of broadband, 14% of them had accessed the Internet via their mobile phones.

For years the two main reasons that people state when it comes to explaining why they have not adopted broadband Internet are price and relevance. The non-adopters either can't afford, don't see the value in subscribing to broadband or think it's simply a waste of time. We can't do anything about the folks who think the Internet is a fad, but why make wireless services and mobile broadband even more expensive, especially if this type of service is so elastic?

Twenty-three states now impose a state-local wireless rate above 10%, which has become the unwritten but psychological barrier that we are seeing sales taxes creep towards.

Wireless services and customers shouldn't be exempted from paying any taxes or fees, but imposing a disproportionately higher tax rate on a service we as a society are pushing people to use more of is duplicitous.

Jaron Lanier on technology and humanity

On this week's podcast, Jaron Lanier, pioneering computer scientist, musician, visual artist, and author, discusses his book, You Are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto. Lanier discusses effects of the web becoming "regularized" and dangers he sees with "hive mind" production, which he claims leads to "crummy design." He also explains why he thinks advertising is a misnomer, contending that modern advertising is more about access to potential consumers than expressive or creative form. Lanier also advocates for more peer-to-peer rather than hub-and-spoke transactions, discusses why he's worried about the disappearance of the middle class, claims that "free" isn't really free, talks about libertarian ideals, and explains why he's ultimately hopeful about the future.

Related Links

"Book review: Jaron Lanier's You Are Not a Gadget", by Adam Thierer

"Caught in the Web", The Wall Street Journal

"A Rebel in Cyberspace, Fighting Collectivism", The New York Times

"The Geek Freaks: Why Jaron Lanier rants against what the Web has become", Slate

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

February 14, 2011

Introducing Digital Liberty

You'll want to visit, follow, friend, and whatever-the-hell-else-people-do the new Digital Liberty project from Americans for Tax Reform.

Digital Liberty's introductory blog post says:

Digital Liberty is dedicated to preserving a free market by pushing back against heavy regulation and taxation of all things Internet, tech, telecom, and media. DigitalLiberty.net will serve as a resource for those who believe in constitutionally limited government by providing news updates and policy briefs on tech issues, sharing research from likeminded organizations, and serving the grassroots who believe that technology and media innovation thrives best when markets are free and individuals are free to choose.

Sounds good to me.

Digital Liberty isn't really new, but an expansion of ATR's work on tech freedom. They tell us that their Web site will provide news and policy briefs, share research from like-minded free-market organizations, and serve the grassroots focusing on free-market tech policy.

That's DigitalLiberty.net. Right on to my brethren and sistren from the happy home of the leave-us-alone coalition!

"Cyber-Collectivism," "Cyber-Progressivism," or What?

The folks at Reason magazine were kind enough to invite me to submit a review of Tim Wu's new book, The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires based on my 6-part series on the book that I posted here on the TLF late last year. (Parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) My new essay, which is entitled "The Rise of Cybercollectivism," has now been posted on the Reason website.

I realize that title will give some readers heartburn, even those who are inclined to agree with me much the time. After all, "collectivism" is a term that packs some rhetorical punch and leads to quick accusations of red-baiting. I addressed that concern in a Cato Unbound debate with Lawrence Lessig a couple of years ago after he strenuously objected to my use of that term to describe his worldview (and that of Tim Wu, Jonathan Zittrain, and their many colleagues and followers). As I noted then, however, the "collectivism" of which I speak is a more generic type, not the hard-edged Marxist brand of collectivism of modern times. For example, I do not believe that Professors Lessig, Zittrain, or Wu are out to socialize all the information means of production and send us all to digital gulags or anything silly like that. Rather, their "collectivism" is rooted in a more general desire to have–as Declan McCullagh eloquently stated in a critique of Lessig's Code–rule by "technocratic philosopher kings." Here's a passage from my Reason review of Wu's Master Switch in which I expand upon that notion:

What's perhaps most troubling about The Master Switch is something it shares with Lessig's book: a concerted effort to redefine "Internet freedom." In the Lessig-Zittrain-Wu construction of Internet freedom, technocrats liberate us from the supposed tyranny of the marketplace and what Lessig calls "code failure." High-tech entrepreneurs are cast as villains; their innovations are viewed as threats to our liberties.

When challenged, Wu, Lessig, and Zittrain all vehemently reject the notion that their outlook is pessimistic. They occasionally insist that they are actually libertarians at heart. But a plain reading of Lessig, Zittrain, and Wu provides little cause for optimism. Unless someone or something—usually the state—intervenes, they warn, the Net and all things digital are doomed. "Not only can the government take these steps to reassert its power to regulate, but…it should," argues Lessig. "Government should push the architecture of the Net to facilitate its regulation, or else it will suffer what can only be described as a loss of sovereignty."

Wu's book has a very concrete regulatory vision in this regard (even though, strangely, he insists it really isn't regulation at all). As I noted in my essay last week following his appointment as a senior advisor to the Federal Trade Commission, Wu wants a so-called "Separations Principle" to govern our modern information economy. It would require that all information providers be segregated into three buckets–creators, distributors, and hardware makers–and then kept strictly compartmentalized. He proposes this in the name of keeping private power in check, which he regards as the primary threat to the information economy, not the government. This is very much in line with the thinking we see in Lessig and Zittrain's work. Here's how I summarize this thinking in my Reason piece:

Wu and other progressives don't always come right out and say it, but they often suggest that private power, however defined, is so persistently insidious that the only way to counteract it is by greatly amplifying state power. We see that yearning for a stronger state in Wu's suggestion that "the disposition of firms and industries is, if anything, more critical than the actions of the state in controlling who gets heard" and in his audacious regulatory solutions, which would greatly enhance the government's power over the information economy.

For these reasons, I believe the "cyber-collectivism" label is appropriate. They want to collectivize (or politicize) decisions that some of us believe are ultimately better addressed by voluntary, spontaneous, bottom-up, marketplace responses and evolving social norms.

At this point, some might ask: Do we need such labels at all? As a philosophy junkie, I think such labels and classifications play a useful didactic role. After all, something quite profound separates these different camps and leads to endless squabbles about nearly every aspect of technology policy. Consequently, my attempt to identify leading schools of thinking about Internet policy issues is not an effort to disparage but, rather, simply an exercise in philosophical classification to help us frame ongoing investigations of these issues in a more rational manner.

I am certainly open to other classification suggestions."Cyber-progressive" might be one option that packs less of a perceived punch than "cyber-collectivist." I've also used the term "cyber social Democrat" and "openness evangelicals" to describe this movement, although both labels have serious shortcomings.

As for myself, I have made no bones about my affiliation with what might be labeled the "cyber-libertarian" school of thought. Clearly, we're a small band of brothers, and we are currently being utterly crushed in these intellectual debates by the cyber-progressives, who dominate almost all major university cyberlaw and Internet policy programs. Nonetheless, despite having so few adherents, I still think it is fair to identify cyber-libertarianism as a distinct school of thinking.

I think we're also seeing the emergence of a clear school of thinking that we'll eventually label "cyber-conservative," as Jerry Brito alluded to in his post about "What Cablegate Tells Us about Cyber-Conservatism." I think the defining characteristics for the cyber-conservative, as with conservatism more generally, can be boiled down to security, stability, moderation, and a healthy respect for tradition. Conservatives occasionally place a high value on liberty in certain economic contexts, but when it conflicts too violently with those other principles, liberty typically gives way to planning. We see this in debates over many national security matters, some privacy discussions, and certain "faith and family" issues. Interestingly, however, conservative principles have never really taken hold in a unified or coherent way within the realm of technology policy, and it's difficult to point to many scholars who would clearly fit under the "cyber-conservative" banner. But I think that is changing today because of rising concerns about state secrets, cyber war, the ubiquity of content considered morally objectionable by many, fears about declining "social order," and so on. [See my comments on Rob Atkinson's Who's Who in Internet Politics for more discussion about cyber-conservatism.]

Do you have better labels for these philosophical schools of thinking about Internet policy matters? If so, I'm all ears.

Additional Reading:

Cyber-Libertarianism: The Case for Real Internet Freedom

The Case for Internet Optimism, Part 2 – Saving the Net From Its Supporters

Thoughts on Wu, Part 5: What Ultimately Separates the Cyber-Libertarian & Cyber-Collectivist

Cato Unbound debate with Lessig, Part 1: Code, Pessimism, and the Illusion of "Perfect Control" & Part 2: "Our Conflict of Visions."

February 12, 2011

Actually, Texans Save $600 Million a Year

A Texas tax official estimates in this story that Texas loses an estimated $600 million in Internet sales taxes every year. Its part of a long-running debate about whether state governments should be able to collect taxes from out-of-state retailers who send goods into their jurisdictions.

What happens with the $600 million depends on what you mean by "Texas." If you mean the government of the state of Texas in Austin, why, yes, the government appears not to collect that amount, which it wants to. If by "Texas" you mean the people who live, work, and raise their families throughout the state—Texans—they actually save $600 million a year. They get to do what they want with it. After all, it's their money.

The Texas tax collector is complaining because the last thing state taxing agents want to do is collect money on in the form of use taxes, which means something like going door to door to collect money from voters based on what they bought from out-of-state. Revenuers intensely prefer to hide the process, collecting their residents' money from out-of-state companies.

Amazon.com is Texas' target—it's the great white whale for tax-hungry jurisdictions nationwide. With no retail outlets and few offices or fulfillment centers around the country, it's not subject to tax jurisdiction in lots of places that would like to tap it for revenue. Having a fulfillment center in Texas may make Amazon liable for $600 million of its customers' money, so it's doing the sensible thing: getting out.

And thank heavens it can! Amazon is a cog in the extremely virtuous process of tax competition. Its ability to move operations means that it can escape states with burdensome taxes and tax collections oblibations, like Texas. Tax competition among states puts downward pressure on taxes, which in turn puts upward pressure on the wealth and well-being of state residents.

The pro-tax folks have been working for years to eliminate tax competition. The "Streamlined Sales Tax Project" continues work it began in 2000 to pave the way for nationwide sales taxation. "Streamlining" sounds so good, doesn't it? But the result would be uniform—and uniformly high—sales taxes that every state might impose on every retailer that sends goods across state lines.

The Web site of the pro-tax coalition sounds good, too: the "Alliance for Main Street Fairness," at the URL standwithmainstreet.com. Who wouldn't want to "stand with Main Street"? Lovers of limited government, for one.

"Fairness" here means uniform high sales taxes and interstate tax collection obligations. The site doesn't say who's behind it, but the campaign to impose taxes on Amazon and other remote sellers is almost certainly a project of big national chain retailers. Rather than fight to lower taxes nationwide, they think they should just saddle their online competitors with tax collection obligations.

As long as the Streamlined Sales Tax Project continues to fail, tax competition in this area survives, and retailers like Amazon can provide lower costs to all of us—including that $600 million in savings enjoyed by Texans each year.

February 11, 2011

Cyber-Intrigue and Miscalculation

If you haven't been following the intrigue around Wikileaks and the security companies hoping to help the government fight it, this stuff is not to be missed. Recommended:

"How One Man Tracked Down Anonymous—And Paid a Heavy Price," on Ars Technica.

"A Disturbing Threat Against One of Our Own," on Salon.

The latter story links to a document purporting to show that a government contractor called Palantir Technologies suggested unnamed ways that Glenn Greenwald might be made to choose "professional preservation" over his sympathetic reporting about Wikileaks. A later page talks of "proactive strategies" including: "Use social media to profile and identify risky behavior of employees."

Wikileaks has no employees. I take this to mean that the personal lives of Wikileaks supporters and sympathizers would be used to undercut its public credibility. Because Julian Assange hasn't done enough…

While we're on credibility: This may well be Wikileaks' rehabilitation. Wikileaks erred badly by letting itself and Julian Assange become the story. We're not having the discussion we should have about U.S. government behavior because of Assange's self-regard.

But now defenders of the U.S. government are making themselves the story, and they may be looking even worse than Wikileaks and Assange. (n.b. Palantir has apologized to Greenwald.) That doesn't mean that we will immediately focus on what Wikileaks has revealed about U.S. government behavior, but it could clear the deck for those conversations to happen.

The concept of "miscalculation" seems more prominent in international affairs and foreign policy than other fields, and it comes to mind here. Wikileaks and its opponents are joined in a negative duel around miscalculation. The side that miscalculates the least will have the upper hand.

Rep. Speier's "Do Not Track" Privacy Legislation

Rep. Jackie Speier introduced legislation today that would require the Federal Trade Commission to establish standards for a "Do Not Track" mechanism and require online data collectors to obey consumer opt-outs through such a tool.

As I'll explain in more detail in my comments on the FTC's privacy report (due next Friday), I've argued for the last two and half years that user empowering users to make their own choices about online privacy is, in combination with education and enforcement of existing laws, the best way to start adddressing online privacy concerns. In principle, some kind of "Do Not Track" mechanism could be a valuable user empowerment tool.

But actually implementing "Do Not Track" without killing advertising won't be easy. Just as consumers need to be empowered to make effective privacy choices, so too must publishers of ad-supported websites be able to make explicit today's implicit quid pro quo: Users who opt-out of tracking might have to see more ads, pay for content and so on.

Government cannot design a "marketplace for privacy" from the top down, nor predict the costs of forcing an explicit quid pro quo. It would be sadly ironic—as Adam Thierer and I pointed out over a year ago—if the same FTC that has agonized so much about the future of journalism wound up killing advertising, the golden goose that has sustained free media in this country for centuries.

The market is evolving quickly here, with two very different "Do Not Track" tools debuting in Internet Explorer 9 and Firefox 4 just this week. Ultimately, it is the Internet's existing standards-setting bodies, not Congress or the FTC, that have the expertise to resolve such differences and make a "Do Not Track" mechanism work for both consumers and publishers, as well as advertisers and ad networks.

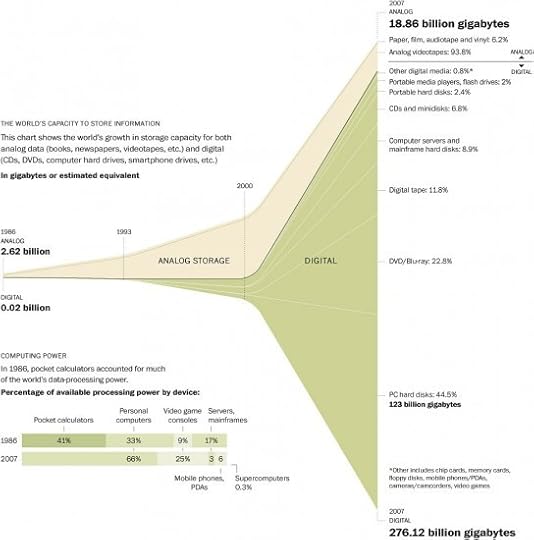

Terrific Visualization of Digital Information Explosion

Here's an amazing graphic that appeared in today's Washington Post depicting how digital information has grown exploded over the past two decades. It's better viewed on a large monitor from this link on the Post website. And here's the accompanying Post article. The underlying data come from a new study by Martin Hilbert and Priscila Lopez of the University of Southern California, which is entitled, "The World's Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information." It appears in the latest issue of Science but is not available without a subscription.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower