Adam Thierer's Blog, page 143

February 21, 2011

Just How Dynamic is the Mobile Internet Marketplace?

To believe some of the worrywarts around Washington, we find ourselves in the midst of a miserable mobile marketplace experience. Regulatory advocates like New America Foundation, Free Press, Public Knowledge and others routinely claim that the sky is falling on consumers and that far-reaching regulation of the wireless sector is needed to save the day.

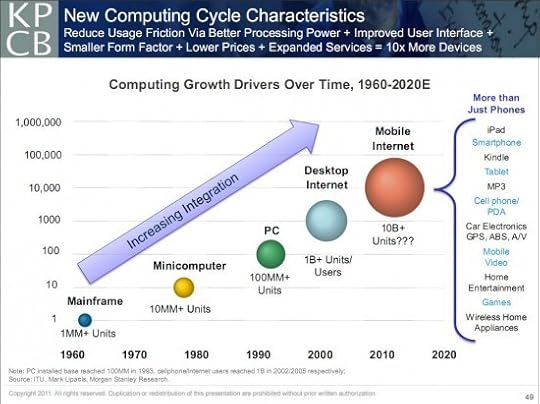

I hope those folks are still willing to listen to facts, becuase those facts tell a very different story. Specifically, I invite critics to flip through the latest presentation by Internet market watchers Mary Meeker and Matt Murphy of Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers on "Top Mobile Internet Trends" and then explain to me how we can label this marketplace anything other than what it really is: One of the greatest capitalist success stories of modern times. Just about every metric illustrates the explosive growth of technological innovation in the U.S. mobile arena. I've embedded the entire slideshow down below, but two particular slides deserve to be showcased.

The first slide illustrates "Computing Growth Drivers Over Time" from the 1960s to present and shows how roughly 10 Billion mobile Internet devices will soon be upon upon us. TEN BILLION!! As the subtitle of the slide summarizes: "Reduced Usage Friction via Better Processing Power + Improved User Interface + Smaller Form Factor + Lower Prices + Expanding Services = 10xMore Devices." Again, absolutely amazing innovation is occuring in all layers of this space.

But wait, shouldn't we fear that the same old big, bad corporate behemoths will dominate the mobile Internet marketplace? The second slide down below explains why such pessimism is unwarranted. True, every generation has its share of large operators in each sector, but Meeker and Murphy's depiction of "Technology Wealth Creation / Destruction Cycles" over time illustrates why high-tech markets are far more dynamic than critics suggest.

As the subtitle of that slide notes, "New Companies Often Win Big in New Cycles While Incumbents Often Falter." Today's titans often become tomorrow's technological also-rans. For example, who in the 1970s would have thought that anyone could give IBM a serious run for its money? And yet IBM ended up completely missing the boat on the rise of home personal computing as the company was myopically stuck in a mainframe mindset that made it serious money in the past but crippled the company for the future. (See this post for more details on the dramatic decline of Big Blue.) Ditto for AOL in the late 1990s or early 2000s. As I've documented here before, AOL was considered the unassailable giant of the Internet space during that period. Today, many of us struggle to figure out how the company even still exists! In other words, today's mobile marketplace giants won't likely be tomorrow's. New forces and faces will move in that we can not yet fathom.

Bottom line: Don't let the cyber-Chicken Littles and tech worrywarts fool you. Things are getting better all the time!

Top 10 Mobile Internet Trends (Feb 2011)

View more presentations from Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers.

Is Apple's digital subscription plan good or bad for consumers?

There has been much hand wringing about Apple's new in-app subscription system for publishers and even one report that antitrust enforcers have begun looking into the matter.

There has been much hand wringing about Apple's new in-app subscription system for publishers and even one report that antitrust enforcers have begun looking into the matter.

The purpose of the antitrust laws is to protect consumers, not companies, so the simple fact that Apple will take a 30% cut from publishers who want to offer subscriptions on iOS devices should not be enough to trigger scrutiny. So, my guess at what a theory of consumer harm against Apple might be is this: Apple not only takes a 30% cut of any subscription purchased in-app on an iOS device, it also requires publishers to offer as low a price on iOS as they offer anywhere else. Therefore, a case could be made that a publisher faced with Apple's 30% fee (and unable to simply raise prices by 30% just on Apple's devices) might raise prices on all platforms enough to cover Apple's cut. So, assuming market power of course, Apple's new policy could affect all digital subscription pricing.

Yet it's hard to talk about market power in such a nascent sector. Digital subscriptions didn't exist 5 years ago, and they do now in large part thanks to Apple. The right market structure is sorting itself out right now and yes, Apple does seem to have a well-earned lead as the innovator in the space. But if the original Mac taught us anything, is that a lead in a nascent sector is no guarantee of monopoly and regulators would be creating serious disincentives to innovation if they meddle.

Digital publishing is very much a contestable market. I hardly need to point out that the day after Apple's announcement, Google made public its own very competitive subscription service. And while the iPad is ahead of the game right now, Android tablets are only now beginning to hit the market. If declining iPhone market share is any indication, Android will nip at Apple's heels in the tablet space as well. And let's not forget other formidable (and somewhat-formidable) competitors in the likes of HP's WebOS, Microsoft-Nokia, and RIM.

Moreover, while the consumer harm is speculative, the potential consumer benefits of Apple's subscription service are pretty clear:

Ease of Use & Security: Apple's app store is a tremendous innovation if nothing else because it creates a simple payment system consumers trust. iPad users will tell you they much prefer one-click subscriptions managed through Apple than having to create many accounts with disparate publishers, which incidentally improves security.

Privacy: One thing that sets Google's offering apart from Apple's is that they will share with publishers information about subscribers. Apple, on the other hand, gives users the choice of sharing information with publishers, and then it's only limited information. This should please privacy conscious consumers.

Subsidized Devices: As a recently viral article in Wired suggests, the reason Apple is able to offer the iPad entry price of $500 (which rivals are having a hard time meeting) is that Apple is a vertically integrated company. This means that the 30% from subscriptions potentially subsidizes the iPad's low price, thus benefitting consumers.

February 20, 2011

Time to mobilize against a governmental takeover of DNS

For better or worse, my first post here is going to be a rather urgent call to action. I'd like to encourage everyone who reads this blog to register their support for this petition. Entitled, "Say no to the GAC veto," it expresses opposition to a shocking and dangerous turn in U.S. policy toward the global domain name system. It is a change that would reverse more than a decade of commitment to a transnational, bottom-up, civil society-led approach to governance of Internet identifiers, in favor of a top-down policy making regime dominated by national governments.

If the U.S. Commerce Department has its way, not only would national governments call the shots regarding what new domains could exist and what ideas and words they could and could not use, but they would be empowered to do so without any constraint or guidance from law, treaties or constitutions. Our own U.S. Commerce Department wants to let any government in the world censor a top level domain proposal "for any reason." A government or two could object simply because they don't like the person behind it, the ideas it espouses or they are offended by the name, and make these objections fatal. This kind of direct state control over content-related matters sets an ominous precedent for the future of Internet governance.

On February 28 and March 1, ICANN and its Governmental Advisory Committee will meet in Brussels to negotiate over ICANN's program to add new top level domain names to the root. The U.S. commerce Department has chosen to make this meeting a showdown, in which the so-called Governmental Advisory Committee (GAC) will demand that the organization re-write and re-do policies and procedures ICANN and its stakeholder groups have been laboring to achieve agreement on for the past six years. The GAC veto, assailed by our petition, is only the most objectionable feature of a long list of bad ideas our Commerce Department is dragging into the consultation. We need to make a strong showing to ensure that ICANN has the backbone to resist these pressures

For those concerned about the role of the state in communications and information, I can't think of a better, clearer flashpoint for focusing your efforts. A great deal of the Internet's innovation and revolutionary character came from the fact that it escaped control of national states and began to evolve new, transnational forms of governance. As governments wake up to the power and potential of the Internet, they have increasingly sought to assert traditional forms of control.

The relationship between national governments and ICANN, which came into being during the Clinton administration as an attempt to "privatize" and globalize the policy making and coordination of the Internet's domain name system, has always been a fraught one. Whatever its flaws (and they are many), ICANN at least gives us a globalized governance regime that is rooted in the Internet's technical commnunity and users, and one step removed from the miasma of national governments and intergovernmental organizations. The GAC was initially just an afterthought tacked on to ICANN's structure to appease the European Union. It was – and is still supposed to be – purely advisory in function. Initially it was conceived as simply providing ICANN with information about the way its policies interacted with national policies.

Those of you with long memories may be feeling a sense of deja vu. Didn't we think we were settling the issue of an intergovernmental takeover of ICANN back in 2005, during the World Summit on the Information Society? Wasn't it the U.S. government who went into that summit playing to fears of a "UN takeover of the Internet" and swearing that it was protecting the Internet from "burdensome intergovernmental oversight and control"? Wouldn't most Americans be surprised to learn that the Commerce Department is now using ICANN's Governmental Advisory Committee to reassert intergovernmental control over what kind of new web sites can be created? Ironically, the US has become the most formidable world advocate of burdensome government oversight and control in Internet governance. And it has done so without any public consultation or legal authority.

Please spread the word about this petition and use whatever channels you have to isolate the Commerce Department's illegitimate incursions on constitutional free expression guarantees.

Isn't "Do Not Track" Just a "Broadcast Flag" Mandate for Privacy?

It seems peculiar to me that some of the same individuals and groups who so vociferously opposed a "broadcast flag" technological mandate in past years are now in a mad rush to have federal policymakers mandate a "Do Not Track" regulatory regime for privacy purposes. The broadcast flag debate, you will recall, centered around the wisdom of mandating a technological fix to the copyright arms race before digitized high-definition broadcast signals were effectively "Napster-ized." At least that was the fear six or seven years ago. TV broadcasters and some content companies wanted the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to recognize and enforce a string of code that would have been embedded in digital broadcast program signals such that mass redistribution of video programming could have been prevented.

Flash forward to the present debate about mandating a "Do Not Track" scheme to help protect privacy online. As I noted in my filing last week to the Federal Trade Commission, at root, Do Not Track is just another "information control regime." Much like the broadcast flag proposal, it's an attempt to use a technological quick-fix to solve a complex problem. When it comes to such information control efforts, however, there aren't many good examples of simple fixes or silver-bullet solutions that have worked, at least not for very long. The debates over Wikileaks, online porn, Internet hate speech, and Spam all demonstrate how challenging it can be to put information back into the bottle once it is released into the digital wild.

To be clear, I am not opposed to technological solutions like broadcast flag or Do Not Track, but I am opposed to forcing them upon the Internet and digital markets in a top-down, centrally-planned fashion. While I am skeptical that either scheme would work well in practice (whether voluntary or mandated), my concern in these debates is that forcing such solutions by law will have many unintended consequences, not the least of which will be the gradual growth of invasive cyberspace controls in these or other contexts. After all, if we can have "broadcast flags" and "Do Not Track" schemes, why not "flag" mandates for objectionable speech or "Do Not Porn" browser mandates?

From 2002-2005, when the broadcast flag wars were really raging, groups like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Center for Democracy & Technology made several legitimate legal and practical arguments against a mandatory broadcast flag regime. But their principled case against broadcast flag mandates came down to an underlying fear about government encroachment on the Internet and the specter of more far-reaching regulation of cyberspace. For example, in a December 2003 report, CDT noted that even if other details could be worked out, "the [broadcast] flag approach will still pose unresolved concerns regarding technical regulation of computers and the Internet by the government [and] the impact of regulations on innovation and future consumer uses" was also problematic.

Importantly, EFF and CDT hammered broadcast flag proponents on the question of jurisdictional authority. They rightly asked where the FCC got the authority to impose such rules at all and worried about the spillover effects of such arbitrary mandates in other Internet contexts. (The broadcast flag scheme was eventually tossed out by the D.C. Court of Appeals because of the FCC's lack of authority.)

So, why wouldn't these same concerns and arguments apply to Do Not Track regulation? CDT and EFF seem to care little that the Federal Trade Commission is aggressively pushing this new information control regime on the Internet. Indeed, CDT and EFF are two of the biggest cheerleaders for FTC action in this regard. Sorry, but I just don't get it. If it was misguided for regulators to push a broadcast flag regime upon cyberspace, isn't it just as misguided for them to be pushing Do Not Track? I suspect this inconsistency has something to do with CDT and EFF being inherently skeptical of the benefits of most online copyright protection schemes while being more sympathetic to legal efforts aimed at protecting personal privacy online. Simply stated, they think there's something to the notion of privacy "rights" and will bend over backward to engineer an information control regime to protect against the "unauthorized" flow of personal information online. When it comes to the "unauthorized" flow of copyrighted bits of information online, however, they aren't nearly as interested in inviting the code cops in.

But even if one sympathizes with that distinction — absolute privacy "rights" vs. minimal copy-"rights" — all the same concerns and criticisms that CDT and EFF raised earlier about the broadcast flag regulatory scheme would seemingly apply to the Do Not Track regime. Both regimes face formidable enforcement challenges and raise the specter of broader government control of cyberspace. There's just no getting around that reality, and Do Not Track defenders who deny it are basically hiding from the ugly truth that they are greasing the skids for future information control efforts and regimes — both here and abroad.

I suppose that they might also argue that regulation is justified where it ensures more "choice" for consumers. But forcing "choice" upon online markets isn't exactly the same thing as allowing it evolve in a natural, non-destructive fashion. As I noted in my filing, many others besides me are concerned about what mandatory Do Not Track would mean for the online ecosystem of mostly "free" content and services. Lauren Weinstein, co-founder of People For Internet Responsibility (PFIR), worries that the "ability [of Do Not Track concepts] to cause major collateral damage to the Internet ecosystem of free Web services is being unwisely ignored or minimized by many Do Not Track proponents." And in a brilliant Huffington Post column this week about the rise of a privacy techno-panic, Jeff Jarvis said, "I also worry that efforts to bring in a 'Do Not Track' list and other demonization of ad targeting could cripple the revenue of the media and news industries even as they struggle to find sustainability; it could kill news outlets and reduce journalism."

Weinstein and Jarvis are right. There is no free lunch. While groups like EFF and CDT who support Do Not Track regulation are well-intentioned in their aims, the reality is that government regulation that attempts to create a cost-free opt-out for data collection and targeted online advertising will likely have damaging consequences for the future provision of online content and services. In terms of direct costs to consumers, Do Not Track could result in higher prices for service as paywalls go up or, at a minimum, advertising will become less relevant to consumers and, therefore, more "intrusive" in other ways.

Which leads to my final point. What is perhaps most perplexing about this is how many of the advocates of Do Not Track argue that such a regulatory scheme will slow the "arms race" in the privacy arena. For example, EFF has said "The header-based Do Not Track system appeals because it calls for an armistice in the arms race of online tracking." And my favorite frenemy Chris Soghoian argues that "opt out mechanisms… [could] finally free us from this cycle of arms races, in which advertising networks innovate around the latest browser privacy control." At best, this is highly wishful thinking. At worst, it's outright deceit aimed at sugar-coating the hard truth: If anything, a Do Not Track mandate will speed up the technological arms race and have many other unintended consequences. Online advertising will almost certainly become "annoying" and even invasive as a result of such regulation. And "tracking" techniques aren't going to be stopped or even slowed as a result of Do Not Track. (Hello DPI!) Again, check out my filing to the FTC for more details.

The important point here is that one intervention will simply beget another and another in an attempt to address the "arms race" and to refine and rework Do Not Track to cover more and more online information flows. One wonders how expansive this new regulatory regime will need to be to deal with the growing scale and volume of online information flows. Really, does anyone think there will be less personal information online in coming years? Unless we stop the unprecedented voluntary information-sharing and self-revelation of personal data that takes place on social networking sites and via user-generated content sites, there is simply no way in hell this problem is going to be curtailed. When 600 million people use Facebook as an open diary to the world (among many other examples I could cite), it's hard to imagine we'll ever be able to stop the mercurial flow of personal information across the Internet. Do Not Track certainly won't stop it, but the cost of putting such a regulatory regime in place in an attempt to put the genie back in the bottle could be profound for the future of the Internet and online content and culture.

Again, this is essentially the same argument previously set forth against a broadcast flag mandate. As EFF once noted, "the technology mandate proposed… is unnecessary, ineffective, and unwise." I agree, and I invite Do Not Track defenders at CDT and EFF (or anyone else) to explain why, conceptually speaking, Do Not Track isn't just broadcast flag in drag.

Welcoming Milton Mueller to the TLF

It's my great pleasure to welcome Milton Mueller to the TLF as an occasional contributor. Milton is a professor at the School of Information Studies at Syracuse University. Cyberlaw and Internet policy scholars are certainly familiar with Milton's impressive body of research on communications, media, and high-tech issues over the past 25 years. You can find much of it on his website here. Regular readers of the TLF will also recall that I have praised Milton's one-of-a-kind research on Internet governance issues, going so far as to label him the "de Tocqueville of cyberspace." His work with the Internet Governance Project and the Global Internet Governance Academic Network is truly indispensable, and in books like Ruling the Root: Internet Governance and the Taming of Cyberspace (2002) and his more recent Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance (2010), Milton brilliantly explores the forces shaping Internet policy across the globe. (Also, make sure to listen to this podcast that Jerry Brito did with Milton about the book and his ongoing research.)

It's my great pleasure to welcome Milton Mueller to the TLF as an occasional contributor. Milton is a professor at the School of Information Studies at Syracuse University. Cyberlaw and Internet policy scholars are certainly familiar with Milton's impressive body of research on communications, media, and high-tech issues over the past 25 years. You can find much of it on his website here. Regular readers of the TLF will also recall that I have praised Milton's one-of-a-kind research on Internet governance issues, going so far as to label him the "de Tocqueville of cyberspace." His work with the Internet Governance Project and the Global Internet Governance Academic Network is truly indispensable, and in books like Ruling the Root: Internet Governance and the Taming of Cyberspace (2002) and his more recent Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance (2010), Milton brilliantly explores the forces shaping Internet policy across the globe. (Also, make sure to listen to this podcast that Jerry Brito did with Milton about the book and his ongoing research.)

More importantly, as I noted in my review of Network and States last year, Milton has sought to breathe new life into the old cyber-libertarian philosophy that was more prevalent during the Net's founding era but has lost favor today. In the book, he notes that his "normative stance is rooted in the Internet's early promise of unfettered and borderless global communication, and its largely accidental and temporary escape from traditional institutional mechanisms of control." He has also given our little movement its marching orders, arguing that "we need to find ways to translate classical liberal rights and freedom into a governance framework suitable for the global Internet. There can be no cyberliberty without a political movement to define, defend, and institutionalize individual rights and freedoms on a transnational scale," he says. Terrific stuff, and I very much look forward to Milton developing this framework in more detail here at the TLF in coming years.

Milton will continue to do much of his blogging over at the Internet Governance Project blog, but will drop by here on occasion to cross-post some of those writings or to comment on other pressing Internet policy issues of the day. Welcome to the TLF, Milton!

February 19, 2011

The Internet Kill-Switch Debate

Experienced debaters know that the framing of an issue often determines the outcome of the contest. Always watch the slant of the ground that debaters stand on.

The Internet kill-switch debate is instructive. Last week, Senators Lieberman (I-CT), Collins (R-ME) and Carper (D-DE) introduced a newly modified bill that seeks to give the government authority to seize power over the Internet or parts of it. The old version was widely panned.

In a statement about the new bill, they denied that it should be called a "kill switch," of course—that language isn't good for their cause after Egypt's ousted dictator Hosni Mubarak illustrated what such power means. They also inserted a section called the "Internet Freedom Act." It's George Orwell with a clown nose, a comically ham-handed attempt to make it seem like the bill is not a government power-grab.

But they also said this: "The emergency measures in our bill apply in a precise and targeted way only to our most critical infrastructure."

Accordingly, much of the reportage and commentary in this piece by Declan McCullagh explores whether the powers are indeed precisely targeted.

These are important and substantive points, right? Well, only if you've already conceded some more important ones, such as:

1) What authority does the government have to seize, or plan to seize, private assets? Such authority would be highly debatable under any of the constitutional powers kill-switchers might claim. Indeed, the constitution protects against, or at least severely limits, takings of private property in the Fifth Amendment.

and

2) Would it be a good idea to have the government seize control of the Internet, or parts of it, under some emergency situation? A government attack on our private communications infrastructure would almost certainly undercut the reliability and security of our networks, computers, and data.

The proponents of the Internet kill-switch have not met their burden on either of these fundamental points. Thus, the question of tailoring is irrelevant.

I managed to get in a word to this effect in the story linked above. "How does this make cybersecurity better? They have no answer," I said. They really don't.

No amount of tailoring can make a bad idea a good one. The Internet kill-switch debate is not about the precision or care with which such a policy might be designed or implemented. It's about the galling claim on the part of Senators Lieberman, Collins, and Carper that the U.S. government can seize private assets at will or whim.

February 17, 2011

What is the meaning of leisure?

My last post on the opportunities presented by "The Great Stagnation" got a bit of attention, and I'm heartened by that because I'd like to develop my conception of "opting out" a bit more in later posts. Today I'd just like to respond to my friend and Colleague Tate Watkins who reacted to my post noting that "most people don't want any more leisure. People don't work 20 hours a week because they would have to make up the difference 'playing with [their] families and reading books.'"

Tate says that spending that much time doing nothing, and doing it with their families, is likely a net minus for most people. I think he's absolutely right, so I guess I need to define what I mean by "leisure" when I say that "the cost of leisure is going down" allowing us to consume more of it.

I'm not sure economists have a very clear definition of "leisure." Generally it's thought of as any activity that's not work.(Please correct me.) I think that's a good start, but the way I conceive leisure it could include work, just not work that one has to do to earn income.

Take for example Cato's Bob Levy, who is one of the persons I most admire in this world. Bob got his PhD in business in 1966 and started an investment technologies firm that he built up and sold in 1991. At this point, Bob was financially independent and could lead a life of leisure. What did he do? He came to George Mason Law and pursued a law degree. In his 50s he interned at IJ and clerked for federal judges, just like other bright people out of law school. After that he served full-time as a legal scholar at Cato and, as far as I know, always contributed to the Institute more than he took in salary. Do you call Bob's activity work or leisure?

Now, Bob was able to pursue his leisure activities because he worked hard to accumulate wealth. But what if we approached it from the other direction? If the activities you want to pursue are inexpensive because the cost of leisure is coming down, then perhaps you can "opt out," pursue leisure, and cover your living expenses with minimum work. Consider the woman I wrote about yesterday. She was supporting herself and her husband on $24,000 a year she makes through bloggin and web design. She fills her time with outdoor activities and volunteering.

A couple of things to keep in mind: To do this one would have to probably accept a standard of living that is at or below the median. But of course this ignores Tyler's point that increases to happiness are more and more becoming internal to the human mind and aren't captured in the usual living standard measures. Also, it seems to me that the option to "opt out" will be available first to knowledge workers because they have greater flexibility about their work and because they are more likely to be the ones to enjoy the gains from internal economies.

Filing in FTC "Do Not Track" / Privacy Proceeding

Today I filed roughly 30 pages worth of comments with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in its proceeding on "Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change: a Proposed Framework for Businesses and Policy Makers." [Other comments filed in the proceeding can be found here.] Down below, I've attached the Table of Contents from my filing so you can see the major themes I've addressed, and I've also attached the entire document in a Scribd reader. In coming days and weeks, I'll be expanding upon some of these themes in follow-up essays.

In my filing, I argue that while it remains impossible to predict with precision the impact a new privacy regulatory regime will have the Internet economy and digital consumers, regulation will have consequences; of that much we can be certain. As the FTC and other policy makers move forward with proposals to expand regulation in this regard, it is vital that the surreal "something-for-nothing" quality of current privacy debate cease. Those who criticize data collection or online advertising and call for expanded regulation should be required to provide a strict cost-benefit analysis of the restrictions they would impose upon America's vibrant digital marketplace.

In particular, it should be clear that the debate over Do Not Track and online advertising regulation is fundamentally tied up with the future of online content, culture, and services. Thus, regulatory advocates must explain how the content and services supported currently by advertising and marketing will be sustained if current online data collection and ad targeting techniques are restricted.

The possibility of regulation also retarding vigorous marketplace competition—especially new innovations and entry—is also very real. Consequently, the Commission bears the heavy burden of explaining how such results would be consistent with its long-standing mission to protect consumer welfare and promote competition. Importantly, the "harm" that critics claim online advertising or data collection efforts gives rise to must be shown to be concrete, not merely conjectural. Too much is at stake to allow otherwise.

Finally, as it pertains to solutions for those who remain sensitive about their privacy online, education and empowerment should trump regulation. Regulation would potentially destroy innovation in this space by substituting a government-approved, "one-size-fits-all" standard for the "let-a-thousand-flowers-bloom" approach, which offers diverse tools for a diverse citizenry. Consumers can and will adapt to changing privacy norms and expectations, but the Commission should not seek to plan that evolutionary process from above.

Download my comments here or just scroll down and read them below.

Contents

I. Introduction

II. No Showing of Harm or Market Failure Has Been Made

How Do We Conduct Cost-Benefit Analysis When "Creepiness" Is the Alleged Harm?

Privacy Regulation & the Precautionary Principle.

On "Informed Consent" & Information as Currency

On "Commonly Accepted Practices"

The Mythical Harm of Consumer "Walk Aways"

III. Privacy Regulation Is an Information Control Regime That Faces Formidable Enforcement Challenges

Media & Technological Convergence

Decentralized, Distributed Networking

Unprecedented Scale of Networked Communications

Explosion of the Overall Volume of Information

Unprecedented Individual Information Sharing Through User-Generation of Content and Self-Revelation of Data

IV. The Commission's Proposed "Do Not Track" Regime Creates Potential Risks to Consumers, Culture, Competition, and Global Competitiveness

Potential Direct Cost to Consumers

Potential Indirect Costs / Impact on Content & Culture

Competition & Market Structure

International Competitiveness

"Silver-Bullet" Solutions Rarely Adapt or Scale Well

Implications of This New Regime in Other Contexts

V. Privacy Regulation Raises Serious Free Speech & Press Freedom Issues

VI. Better, Less-Restrictive Solutions Exist to Privacy-Related Concerns

Education, Empowerment & Self-Regulation

Simplified" Privacy Policies, Enhanced Notice & "Privacy by Design"

Increased Sec. 5 Enforcement, Targeted Statutes & the Common Law

VII. Conclusion

Comment in FTC Do Not Track Proceeding (Adam Thierer – Mercatus Center)

February 16, 2011

Is the Great Stagnation a great opportunity?

In his column on Monday, David Brooks put his finger on what I found most interesting about Tyler Cowen's The Great Stagnation. Namely:

It could be that in an industrial economy people develop a materialist mind-set and believe that improving their income is the same thing as improving their quality of life. But in an affluent information-driven world, people embrace the postmaterialist mind-set. They realize they can improve their quality of life without actually producing more wealth.

As Tyler points out in this book, and catalogued at length in his other excellent book, Create Your Own Economy, recent increases in happiness come from growth in internal economies. That is, internal to humans. In the past, increased well-being came from not having a toilet and then having one, or the invention of cheap air travel. Today they come from blogging, watching Lost on Netflix, listening to a symphony from iTunes, tweeting with your friends, seeing their pictures on Facebook or Path, and learning and collaborating on Wikipedia. As a result, once one secures a certain income to cover basic needs, greater happiness and well-being can be had for virtually nothing.

The problem some see with this is that the Internet sector, while it may give us amazing innovations, produces little by way of revenue or jobs. Brooks also laments that because American's have not come to grips with this growing distinction between wealth and standard of living, we tend to live beyond our means, which is certainly true in a personal and public fiscal sense.

But I'd like to see this seeming decoupling of wealth and well-being as an opportunity.

If we've doubled our productivity over the last 50 years, why are we not working 20 hours a week and enjoying the difference playing with our families and reading books? Well, it's because the opportunity cost of leisure is high. Time spent on leisure means time not spent generating income, and if happiness is tied to material wealth, then that may be an expensive trade-off.

However, if happiness is increasingly decoupled from material wealth, then perhaps the cost of leisure is going down and we can finally afford to indulge in more of it. If you can grasp the distinction, then you realize that it is now truer than ever that beyond a certain point, accumulating more material wealth will not contribute to your happiness. The opportunity that presents itself is to live "below your means" yet be happier than ever.

Though anecdotal, there is some evidence that young people are choosing this route and "opting out." Here's a NYT "trend piece" on the topic. One of its subjects is a 31-year-old woman who traded her investment management job for more leisure:

Today, three years after Ms. Strobel and Mr. Smith began downsizing, they live in Portland, Ore., in a spare, 400-square-foot studio with a nice-sized kitchen. Mr. Smith is completing a doctorate in physiology; Ms. Strobel happily works from home as a Web designer and freelance writer. She owns four plates, three pairs of shoes and two pots. With Mr. Smith in his final weeks of school, Ms. Strobel's income of about $24,000 a year covers their bills. They are still car-free but have bikes. One other thing they no longer have: $30,000 of debt.

Ms. Strobel's mother is impressed. Now the couple have money to travel and to contribute to the education funds of nieces and nephews. And because their debt is paid off, Ms. Strobel works fewer hours, giving her time to be outdoors, and to volunteer, which she does about four hours a week for a nonprofit outreach program called Living Yoga.

Portland, as Fred Armisen tells us, is where young people go to retire. Now, what I haven't considered are the effects of "opting out" on innovation, or the distributional issues. (That is, can everyone afford to sleep 'til eleven?) I'll try to address these in later posts.

February 15, 2011

A Debate on NPR about the Future of NPR

It was my pleasure today to debate the future of public media funding on Warren Olney's NPR program, "To The Point". I was 1 of 5 guests and I wasn't brought into the show until about 29 minutes into the program, but I tried to reiterate some of the key points I made in my essay last week on "'Non-Commercial Media' = Fine; 'Public Media' = Not So Much." I won't reiterate everything I said before since you can just go back and read it, but to briefly summarize what I said there as well as on today's show: (1) taxpayers shouldn't be forced to subsidize speech or media content they find potentially objectionable; and (2) public broadcasters are currently perfectly positioned to turn this federal funding "crisis" into a golden opportunity by asking its well-heeled and highly-diversified base of supporters to step up to the plate and fill the gap left by the end of taxpayer subsidies.

Just a word more on that last point. As I pointed out on the show today, it's an uncomfortable fact of life for NPR that their average listener is old, rich, highly-educated, and mostly white. Specifically, here are some numbers that NPR itself has compiled about its audience demographics:

The median age of the NPR listener is 50.

The median household income of an NPR News listener is about $86,000, compared to the national average of about $55,000.

NPR's audience is extraordinarily well-educated. Nearly 65% of all listeners have a bachelor's

degree, compared to only a quarter of the U.S. population. Also, they are three times more likely than the

average American to have completed graduate school.

The majority of the NPR audience (86%) identifies itself as white.

Why do these numbers matter? Simply stated: These people can certainly step up to the plate and pay more to cover the estimated $1.39 that taxpayers currently contribute to the public media in the U.S. But wait, there's more! There are plenty of other existing corporate and foundational supporters out there who already make sizable contributions to NPR. Down below, I have attached a list that appeared in the NPR's 2008 annual donor list of just the corporations who currently support NPR and it includes only those companies who support at a level greater than a half million per year. There are many others who offer annual support for less than that and then there are the hundreds of foundations and wealthy families who give major gifts of varying amounts.

Again, these individual benefactors could all probably be prodded to give a bit more, and plenty of others out there would likely step up to the plate to meet the challenge of filling the small gap left by ending taxpayer support. For God's sake, just look at that list of current top-dollar corporate supporters for NPR down below! It reads like a "Who's Who" of the Fortune 500 giants and it must leave all of NPR's competitors stinging with jealous about how smart it was for non-commercial media to diversify its base of philanthropic support so long ago.

Thus, there's no reason that public media operators can't take the next step and find alternative means of support to fill the 16% of their budgets that currently comes from taxpayers. In these tight fiscal times, it's only fair.

$1 Million + Supporters of NPR in 2008

Angie's List

CITGO Petroleum

Corporation CSX Corporation

Feeding America

Fox Searchlight Pictures

General Motors Corporation

Institute for Supply Management

Insurance Company

Intel Corporation

Johnson Controls

Kashi Company

Lindamood-Bell Learning Systems

Lumber Liquidators

MasterCard

MGM

National Association of Realtors

Netflix

Northwestern Mutual Foundation

Novo Nordisk

Overture Films

Pabst Brewing Company

Paramount Home Entertainment

Paramount Pictures

Prudential Financial

PBS Raymond James Financial Services

Philips Healthcare

POM Wonderful REI

Progressive Casualty Insurance

Scotts Miracle-Gro Company

State Farm Mutual Automobile

Travel Guard

U.S. Bank Vestas

Universal Pictures

Visa Warner Home Video

Walden University Yahoo!

Wind Systems

$500,000-$999,999 Supporters of NPR in 2008

Cargill

Citibank

Constant Contant

Constellation Energy

Focus Features

iShares

Leanding Tree

Lenovo

Lionsgate

Entertainment

CNetApp

Pajamagram Company

Saturn

Sit4Less.com

Subaru

T. Rowe Price

UPS

Vanguard Group

[Read rest of the list of this impressive list of NPR corporate and foundational supporters here. Has there ever been a more well-diversified base of support for any media operation in American history? I think not. As Jill Lawrence points out on Politics Daily, public media's extremely loyal -- and rich -- fan base are not about let NPR and PBS die.]

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower