David Tallerman's Blog

September 26, 2025

Drowning in Nineties Anime, Pt. 146

Pleasant as it was last time around to cover some of my all-time favourite films in the second part of our Studio Ghibli special, this month's batch of deeply obscure oddities feels so much more in the spirit of Drowning in Nineties Anime. Though, thinking about it, it's fair to say that all four entries here are actually products of major franchises - it's just that they're major franchises that never made a meaningful impact outside of Japan. And so we have an Osamu Tezuka adaptation, a hugely popular magical girl, a spin-off from an enormous video game series, and an OVA from a major action-comedy franchise, and there's still an extremely good chance you won't have heard of a thing from among Ambassador Magma, Gigi and the Fountain of Youth, Fire Emblem, and Saber Marionette J Again: Plasmatic Crisis...

Ambassador Magma, 1993, dir: Hidehito Ueda

Ambassador Magma, 1993, dir: Hidehito UedaIt's always nice when a title exceeds your expectations, though nicer, it has to be said, when those expectations were above rock bottom. Ambassador Magma the OVA series is a slice of vintage anime that I've never once known anyone to mention, which was released by not one but two publishers you've almost certainly never encountered: Kiseki in the UK, L A Hero in the US. Heck, I'm not convinced Kiseki even put out the full series, given that there's no trace of more than three volumes that I can find; the US version spreads the 13 episodes over six tapes, and I assume they'd planned to do likewise. And while in the plus column we have as source material a much-loved, in Japan anyway, manga from the legendary Osamu Tezuka, nostalgic reboots of classic sixties properties are every bit as likely to go awry in Japan as they are anywhere else.

Yet, with all of that, Ambassador Magma is thoroughly okay and frequently quite good, and if that hardly sounds like a recommendation, I do intend it to be, albeit with a few caveats. The one you might expect would be that you're unlikely to ever find the thing, except that it's apparently reared its head on US streaming services, having skipped a couple of decades of intermediary formats. That aside, the negatives are mostly trivial, and largely come down to an acknowledgement of what he have here: for all that I get the impression the creators were doing quite a bit to make their material feel more current than its source, they certainly didn't go so far as to erase its innate goofiness or to worry unduly about setting it apart from a million other "boy and his giant robot buddy have exciting adventures" anime properties.

Which isn't to suggest that's all it's up to; one of Ambassador Magma's weirder quirks is how little screen time the titular golden giant gets in favour of our teenage protagonist Mamoru, his parents, a handful of reporters, a bunch of military folks, and indeed Magma's arch-nemesis Goa, all of whom feel more significant to the story as it unfolds than the huge shiny guy who occasionally pops up to batter a monster. Indeed, this was Ambassador Magma's best surprise: for all that it has a definite 'cartoon adaptation based on a 60s comic aimed primarily at kids' vibe, the actual plot veers all over, including to a few places I'd have never anticipated, and spends as much time dipping into horror and weird sci-fi and smaller scale action as it does focusing on the sort of giant-robot-battling-monsters shenanigans you'd have every reason to expect. The plot has its share of flaws, including a few points where, in the dub anyway, it's downright incoherent - Goa's backstory with humanity, in particular, seems to change on a scene-by-scene basis - but generally it does a respectable job of finding thirteen episodes of content with which to keep itself occupied and building towards its climax with a proper measure of escalation.

At which point I'm starting to feel like I'm describing a show that's better than "thoroughly okay", and arguably my reason for landing there comes down largely to personal taste. The more so since it's mostly due to the look of the thing, and I can't really fault the animation as a whole: it's never less than competent and often rather ambitiously flashy. But the character designs are just horrible. The goal, I think, was to keep the simplicity of Tezuka's art while bringing it into the present, and Ambassador Magma fails on both counts, losing every iota of Tezuka's charm but still looking dated even by nineties standards. Moreover, it's the main cast who get the worst of it, which becomes all the more noticeable later on when a couple of designs that actually work show up. It seems like it ought to be an inconsequential bother when stacked against the virtues elsewhere, but in practice it's an awful drain on the show's energy, making it too often look like the kiddie cartoon it mostly manages not to feel like. And so we end up back at "thoroughly okay", with the caveat that if the designs don't bother you, and if you're a fan of Tesuka and that era of Japanese sci-fantasy, you might find plenty to love here.

Gigi and the Fountain of Youth, 1985, dir: Kunihiko Yuyama

Gigi and the Fountain of Youth, 1985, dir: Kunihiko YuyamaIf we were to discuss Gigi and the Fountain of Youth by its more accurate-to-the-Japanese title, we'd be talking about Magical Princess Minky Momo: La Ronde in my Dream, which, as you might notice, hasn't a single word in common and also apparently has a different protagonist. Quite an accomplishment, you'd think, but the fact is that we're back in the world of Harmony Gold and Carl Macek, and if you have any familiarity with those names, you'll both know better than to be surprised at a spot of drastic misnaming and have already set your expectations to a barrel-scrapingly low level. For their collaboration was mostly one of treating Japanese animation as raw product to be mangled in whatever way they saw fit, so long as it could be made vaguely palatable to small American children.

I say "mostly" because here we are and the dub of Gigi and the Fountain of Youth is actually pretty great, Gregory Snegoff's script is a solid piece of writing in its own right, and while I have my doubts as to how much any of this is a faithful adaptation of the original Japanese - the apparent lack of ten minutes of running time sets off alarm bells even before you get to some obvious translation liberties - the truth is that it works just fine. And to be fair to all involved, bringing the second OVA spin-off of a long-running, much-loved-in-its-native-country magical girl series to a Western audience that almost certainly wouldn't have the faintest knowledge of it was no small task, and we can hardly blame those involved if they chose, for example, to slap a bit of narration over the opening credits to key us in on some crucial information.

But already we get to why this is the rare dub that works on its own merits. What starts with an upbeat but faintly dry narrator tossing us some bare-bones information rapidly devolves into an argument between said narrator and Gigi's dad, the king of some magical realm that the adaptation makes no efforts towards explaining. For all that it's an obvious idea, the execution is legitimately amusing; but more than that, it does a fantastic job of setting our expectations, since, though the narrator will vanish soon enough, the foreknowledge that we're in for lots of freewheeling weirdness with the barest respect for the fourth wall or narrative convention is extremely valuable for what's to come.

And this I don't think we can pin on Macek, Snegoff, Harmony Gold, or any of the game American cast trying to navigate through the madness; it certainly feels in keeping with other Japanese kids' movies of the period, where pure dream logic and whiplash tonal shifts were par for the course. However, nor are any of the American creative team trying to rein the material in, and thank goodness for that, since once you settle into Gigi's rhythm, it's a delight. Or should that be lack of rhythm? Certainly, the first twenty minutes or so, in which Gigi and her friends set off to rescue her parents from an airline crash and stumble upon an isolated island that houses what's basically Neverland from Peter Pan, feel as close to incoherent as any narrative I've seen that wasn't being purposefully surreal. That seems pretty baked in to the franchise, too: take Gigi's magical girl power, which isn't to transform into a single alternative persona, as is usually the way with these things, but to turn into literally anyone she wants to be. Granted, her choices here only extend as far as "sneak thief" and "pilot", but it remains a uniquely disorientating approach to that particular trope.

Nevertheless, bear with Gigi and the Fountain of Youth and there is an actual plot here, with something like a beginning, middle, and end. Granted, that beginning, middle, and end cover a dozen different genres, from comedy to conspiracy thriller to musical, and get awfully cluttered with whatever ideas happened to strike the creators in any given moment, but they're there. And crucially, keeping up never feels like a chore. At worst, it's a bit confusing in the early going, which really is a whirlwind of seemingly unrelated stuff happening. But while it's never less than busy and deeply eccentric, the bones are those of a solidly entertaining and even, in places, an unexpectedly poignant movie. And while the animation budget seems more in line with some polished episodes of the TV show than an OVA, it's really only the frame rate that suffers, with there never being a sense that the spectacle - which gets pretty darn spectacular in places, as the absurdity reaches epic heights - is being compromised. For all its strangeness, there's the sense that everyone involved was giving their all to Magical Princess Minky Momo: La Ronde in my Dream, and let's be glad that the same can be said of Gigi and the Fountain of Youth. It's a heck of a shame we never got more of Minky Momo's bewildering adventures in the West, but at least Macek and co recognised the gem they had and tried to do it justice.

Fire Emblem, 1995, dir: Shin Misawa

Fire Emblem, 1995, dir: Shin MisawaTo start with some positives that set Fire Emblem a little apart from your average two-part OVA, and indeed your average nineties anime video game adaptation, it's an awfully slick and detailed piece of animation made by a director who's making actual choices that go beyond ensuring that everything's legible and on budget. Misawa constructs scenes interestingly throughout and stages some bursts of legitimately exciting action, and he and his team have put meaningful thought into such age-old problems as how to distinguish past from present and how to keep a large cast easily identifiable. To expand on that latter example, not only do we have some easily readable designs and a spot of well-used colour coding, the central characters are drawn to a notably more exaggerated, big-eyed aesthetic compared with the relative realism of the minor players. It may sound like damning with faint praise, but there's much to be said for good nuts-and-bolts filmmaking, especially when you've got a lot of material to work through and not much time in which to do it.

Except that I was damning with faint praise, because none of the above is enough to save Fire Emblem. I mean, I guess that it's saved from being an unmitigated disaster and nudged into the heady realms of mildly ambitious failure; I'll never be the one to argue that above-par animation and more-than-competent direction count for nothing. But they can't substitute for good bones, and Fire Emblem has such dodgy bones that it's amazing it can stand up straight, let alone stagger along for the better part of an hour.

We might lay that at the door of its being an adaptation of a video game that was never about to have its plot squashed into fifty minutes, and we might also point to the fact that it feels awfully like there was intended to be more than what we ultimately got, but, though both points surely didn't help, I think we'd be making excuses for some pretty fundamental failings. Because if you only have two episodes, you have to make sensible use of that time, and Fire Emblem doesn't do this to such a degree that I truly couldn't tell you what tale the first episode thinks it's telling. If I were being generous, I'd propose that it's to do with the young prince-in-exile Mars working past his doubts and the caution of his elders to re-enter the conflict that claimed his father's life, but even then, what I've summarised there is basically just a series of events: "hero sits around, finally decides to act" is a jumping-off point, not a story in its own right. And while part two feels somewhat less shapeless, it commits the identical sin and adds a new one of its own, splitting the focus onto a side character who also spends twenty minutes dithering before finally deciding to act for reasons we the viewer have barely been made privy to.

Not finding enough of a narrative through-line is annoying, but I guess it's understandable given how much game there was to cram in here - though, again, we might argue that trying to cram so much in rather than picking out a couple of chunks that would be satisfying in their own right is precisely where things began to go wrong. At any rate, what pushes Fire Emblem over into being properly annoying is how much of a slog it is to follow even when there's so little happening. I praised Misawa for differentiating his flashback footage, for example, but the method he chose just looks like someone mucked up the contrast, and even then, opening with a flashback when you've not established anything to flash back from is pretty shoddy.

Fire Emblem does a lot of that kind of thing, not to mention at least one moment of flat-out incoherence: there's a scene in which the side-protagonist of episode two appears to rescue a young couple from bandits, yet when we next encounter them, one's back in captivity and the other is having their injuries treated by our heroes, and I was so bewildered that I watched the sequence again to be sure I hadn't missed something. But no, we're presumably just meant to guess what occurred in the meantime, or maybe to have played the game, in which case why bother adapting it to a different medium at all? Put all those niggles together and the results are actively frustrating: such a straightforward bit of cheesy fantasy ought to be the easiest thing in the world to keep up with, not a puzzle in constant need of unravelling. And, if anything, it only adds to the frustration that Fire Emblem gets so much right; there were obviously a bunch of talented people here putting in the effort to make something special, and it's a shame the good stuff was undone by such fundamental mistakes.

Saber Marionette J Again: Plasmatic Crisis, 1997-1998, dir: Masami Shimoda

Saber Marionette J Again: Plasmatic Crisis, 1997-1998, dir: Masami ShimodaI was unreasonably excited to come across Saber Marionette J Again, given that, before I stumbled upon it, I'd pretty much convinced myself I knew of every bit of nineties anime there was that had made it as far as a DVD release. And my only prior history with the Saber Marionette franchise - which is surprisingly vast for something so widely forgotten - was the OVA Saber Marionette R, which I'd quite enjoyed, particularly for the extravagant amount of world building it managed to fit into a relatively brief running time. Saber Marionette J Again, at six episodes long, had twice the space to work with, so what could go wrong?

Looking at the back of the DVD case, I can see at least one reason why I was foolish to get my hopes up. It's not the quality of the artwork, which is hard to judge from still images: they can't convey the jankiness of late-90's animation that's relying too hard on computers to do things on the cheap, at the behest of animators who seemingly have no idea how to hide the seams, to the point where there's invariably a digitised line or two flickering aggravatingly somewhere. (Though I do think you can spot the floatiness of digital foregrounds plastered over painted backdrops if you look carefully.) But no, the actual giveaway is that, of the seven images chosen by Bandai to promote the show, not one shows off anything more dramatic than a conversation.

You might think that, if you were trying to sell buyers on your light-hearted action show, you'd want to include some action in there - but we oughtn't to criticise whoever designed that packaging for failing to emphasise something that Saber Marionette J Again could hardly have made a lower priority. Our first hint of excitement comes, I swear, towards the end of the fourth episode, and only number five could legitimately be described as action-heavy. I'm not saying a six-episode OVA has to be action-packed, not even when it's the sequel to a TV series that was; I'm sure I could come up with examples of similar things I love that are heavier on the talking than this. But the problem is that Saber Marionette J Again does so little to fill that void with anything else, and indeed so little to warrant its running time.

What we get is pure anime spin-off boilerplate: the cast are reunited for tenuous reasons and a new character is introduced, who'll prove to be crucially important until they vanish at the end, never to be heard from again. Here that character is Marine, and her arc is a great illustration of the leaden pacing. If I remember rightly, she doesn't even properly appear until episode two, where she's set up as an antagonist in a thread that's rapidly dropped. We then get an episode of her being incorporated into the show's ongoing harem comedy shenanigans, before, well into episode four, we get the aforementioned action scene as a lead-in to - well, to the plot, essentially, or at any rate to the particular (and yes, plasmatic) crisis that Marine will be required to deal with. Like I said, it's purest boilerplate, but it's terrible at being even that, what with its somnambulant pacing and plenty of enormous, unnecessary plot holes and baffling character decisions, as when the nominal villains spend an episode trying to kill the one and only person they know can save the world on which they themselves live.

In a sense, though, such criticisms are maybe missing the point. Or it might be fairer to say that, in saddling Saber Marionette J Again with any sort of high-stakes drama, the creators were the ones missing the point of their own property; either way, the plot's dumb because nobody cared about it and because the show has no place for existential threats when it would rather be hanging out with its silly, one-note characters making goofy jokes. And who knows, if you were a fan of the series, maybe that would be enough? Purely on its own merits, though, Saber Marionette J Again is functional, kind of ugly, and ultimately sunk by devoting any energy at all to a narrative it couldn't be less invested in.

-oOo-

You'd really think I'd know better than to have any sort of expectations by now, yet Fire Emblem and Saber Marionette J Again both managed to disappoint, so more fool me. On the other hand, my hopes were low indeed for Ambassador Magma and Gigi and the Fountain of Youth, and those both proved to be nice surprises, particularly the latter, which has become a minor new favourite. And, you know what, with only four more posts to go because we've covered basically everything there is to cover, or three if we exclude the end of the Studio Ghibli special, it's pretty great that there are still some unexpected treats waiting to be found. Plus, I'm far enough into the next post to know that we haven't seen the last of them, and that we may yet get to wrap up this marathon through the vast world of vintage anime with slightly more of a bang than a whimper...[Other reviews in this series: By Date / By Title / By Rating]

July 31, 2025

Drowning in Nineties Anime, Pt. 145

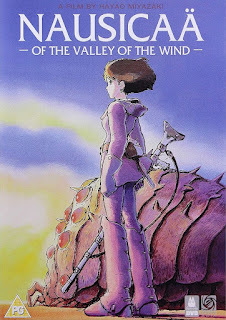

It's post number 145, which means part two of the Drowning in Nineties Anime Studio Ghibli special, and specifically a look at the four films released by Ghibli between 1989 and 1993. They're fascinating for any numbers of reasons, of course, but what struck me was that here, already, three movies into their lifespan, we were into the troubled stage in which the studio tried to figure out how the heck it could be more than just an outlet for its two genius creators, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata. Spoiler alert, except not really, since we both live in the present day: they'd never quite work that out, and the whys and wherefores of that failure would lead to some fascinating and even somewhat tragic places over the succeeding decades. Though the flip side, and another thing that's awfully evident here, is that the mere act of trying, and the determination to not coast on early successes, led them to some equally interesting places and - as we're about to see - a wonderfully diverse output.

Let's take a look at Kiki's Delivery Service, Only Yesterday, Porco Rosso, and Ocean Waves...

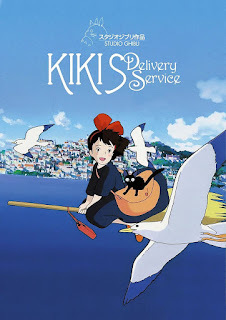

Kiki's Delivery Service, 1989, dir: Hayao Miyazaki

Kiki's Delivery Service, 1989, dir: Hayao MiyazakiKiki's Delivery Service was originally intended to be a short film - at a planned 60 minutes, short by Ghibli standards, anyway - and to be directed by Sunao Katabuchi, until Hayao Miyazaki's involvement as producer because so extensive that he took over as director too, at which point the running time ballooned, as did the budget, to end up being among the highest for an animated film at that point. At the time, perhaps no one would have thought much of Katabuchi being shouldered out by his considerably more experienced and respected producer, but now we have the benefit of nearly four decades of hindsight and know that he'd go on to become a master animator in his own right, with In This Corner of the World in particular standing as one of the great achievements of 21st century anime. So it's interesting to wonder what might have been had Miyazaki held back, and to speculate to what extent all this was the result of a troubled production, as, not for the last time, Miyazaki tried and failed to expand Ghibli's directorial base beyond himself and Isao Takahata.

Whatever went on, Kiki's Delivery Service is a markedly less flawless film than anything Ghibli had produced up until that point. Indeed, at the level of raw plot, it's really kind of a mess. Miyazaki's screenplays have a tendency to be kind of shaggy, but none of them rely so heavily upon contrivance and happenstance as this does, and none feel so aimless until well past their midway point. A single example to illustrate: having set off alone at 13 to find her way in the world, young witch Kiki has more or less accidentally set up a delivery business, since being able to fly on a broom is handy in that line of work. For her first proper job, she's tasked with delivering a bird cage that contains a toy black cat that so happens to be the spitting image of her familiar, Jiji. But mid journey she's caught by a gust of wind, the toy cat gets lost during a run-in with some angry crows, and Jiji is obliged to play dead to act the part until Kiki can recover the real thing. This she does by noticing it in the window of an artist who lives in the depths of the woods - said artist will become an important character, not to mention something of a deus ex machina, later - and the problem of swapping Jiji with the toy turns out to be no problem at all thanks to the intervention of a kindly old dog.

Write it down like that and it really is just ten minutes of stuff happening, without much rhyme or reason and without much in the way of character agency. While Kiki ignores a warning about the wind and does a bit of housework as payment for the return of the toy cat, nevertheless it mostly feels as though neither her travails nor her successes are due to anything she has or hasn't done. And such woolly plotting isn't the film's only flaw, either: I'd forgotten how irritating the character of Tombo, Kiki's kind-of love interest, is, at least until we get to know a bit more about him past the midway point - since it very much seems we're meant to find him off-putting until then, as Kiki herself does. I'd even propose that Joe Hisaishi's score isn't up there with his best efforts, with a tendency towards a chipper Continental vibe that's a perfectly fine match for Miyazaki's purposefully nonspecific hodgepodge of a European town but doesn't elevate the material the way his finest works do.

Yet I love the film wholeheartedly, and would rate it in the top half of any list of my Ghibli favourites. And feeling that way doesn't require me to ignore its flaws, as I hope I've made clear, or to pretend they're all somehow intentional. I do think they're somewhat intentional, and in a way only a genius like Miyazaki could pull off, but that's not to say that, for instance, having a major character who's downright annoying for half the running time should be ignored. Nevertheless, a Kiki's Delivery Service without its imperfections would undoubtedly be worse, since the thing it's exceptionally good at, which happens to be the thing Miyazaki stated as his intention for the film, is to capture the sort of crisis of faith you can only really have as a teenager, as you realise that the world isn't fair or rational, and sometimes bad things happen for no reason, just as sometimes you're rewarded for getting things wrong. You wildly misjudge situations and people; you sulk and often don't even know why; you can be overwhelmed with joy and wonder one minute and sunk in self-loathing the next. And few films convey that turmoil half so successfully, or with a central character half so well-formed and charming as Kiki, a protagonist markedly more complicated than any Miyazaki had offered prior to this point.

Plus, the plotting may often feel arbitrary, but when every moment is so perfect in and of itself, it's hard to care. Take that sequence I critiqued earlier: sure, it's set off by a random mishap, but my goodness is the scene of Kiki being flung about by gale force winds an exquisite bit of animation - indeed, the flying sequences consistently rank among the most terrific of Ghibli accomplishments - and lucky break that it may be, my goodness are the scenes with Jiji and Jeff the elderly dog funny and adorable and sweetly melancholy. It's as though Miyazaki, through enormous force of will, is invariably finding the best possible version of material that theoretically oughtn't to work half so well as it does and that, in lesser hands, could slip into being aimless and twee in a heartbeat. And while I don't know that I'd describe Katabuchi as "lesser hands", I can certainly see how, so much nearer to the start of his career as he was then, he might not have been able to read between the lines of Miyazaki's screenplay the way its author could. Which is okay, I think; ultimately he'd go on to make a couple of near-perfect coming-of-age movies of his own, and we got to have Hayao Miyazaki's Kiki's Delivery Service, one of the loveliest and most empathetic family films of all time.

Only Yesterday, 1991, dir: Isao Takahata

Only Yesterday, 1991, dir: Isao Takahata

A couple of personal anecdotes to start with. First up, Only Yesterday was the film that turned me around on Isao Takahata, who until then I'd regarded as that other guy from Studio Ghibli, and knew only from Grave of the Fireflies, a film that's almost impossible not to admire and equally nigh-impossible to love. But Only Yesterday, now there's a movie that you can fall in love with, and I did, and I love it still - indeed, I was slight surprised, returning to it, to realise just how big a place it holds in my heart. That being anecdote number two, as I discovered to my shock that I've been quoting one particular stretch of dialogue practically verbatim for years without appreciating where it had come from or that I was quoting at all. For those who've seen it, it's Toshio's mini-lecture in response to Taeko's joy at being amid what she sees as untouched nature, to which he responds that every stream, every wood, every hedgerow has actually been arranged and controlled by the people who live there, generation after generation, in service of their needs.

Only Yesterday is full of such insights. It's long, at narrowly under two hours, and has the bare minimum of plot: Taeko takes a working holiday in rural Japan as a break from an office job in Tokyo that she's starting to realise isn't fulfilling her needs at all, reminisces about the brief spell in her childhood that made her want to visit the countryside in the first place, and hangs around with Toshio, a local organic farmer, who already has quite the crush on her and who she slowly discovers she's falling for in return. Really, laying it out like that suggests a more plot-heavy and overtly structured film than the one we get, which is episodic in the extreme, often spending minutes at a time exploring a particular incident in ten-year-old Taeko's life, varying from the triviality of trying fresh pineapple for the first time to the momentousness of the one occasion her kindly, rather distant father struck her.

It ought to be messy, and yet it's so perfectly controlled and so constantly engaging that it never feels that way. I think that part of why I was once a little cool on Takahata is that his films can feel kind of unfocused and overloaded with stuff, and sure, that stuff is all wonderful, but does it absolutely all need to be there? Watch Only Yesterday closely and the only possible conclusion is that yes, it does, or at the very least that Takahata strongly believes it does, and has given his utmost to ensure that not a frame feels wasted or superfluous. It's intoxicating, almost but not quite too much of a good thing, and just as with Grave of the Fireflies, I was a helpless, blubbering mess by the end; but this time it was the happy crying that comes from watching something completely transporting and genuinely life-affirming, not because it feeds you platitudes but because it reminds you that goodness exists and change is possible.

And obviously it's gorgeous, that ought to go without saying at this point, but even by Ghibli standards, Only Yesterday is gorgeous in some particularly distinctive ways. That extends to the soundtrack, surely the most complex of any of the studio's movies, with a mix of licensed tracks, an original score, and most strikingly, traditional Eastern-European folk music that lend the scenes it appears in a haunting, off-kilter energy. Visually, meanwhile, Takahata makes the perhaps obvious choice of making the present-day scenes essentially realistic, while the flashbacks to Taeko's childhood have the washed-out, faded-edge impression of old photographs, an approach that would have been easy to abuse and which he manipulates sublimely to convey the ebbing and flowing vividness of Taeko memory. And though it's easy to think of Miyazaki as Ghibli's resident perfectionist, not much in his canon can compare with the attention to detail in the the present-day scenes: what they lack in gimmickry, they more than make up for in quality, rendering prosaic elements like a night-time car journey so painstakingly that they end up feeling not at all prosaic. There's truly not a frame I could nit-pick, just as there isn't a moment I'd trim or change: it's daft to talk about perfect films, of course, and yet for the life of me I can't imagine a better version of Only Yesterday than the one Takahata created.

Porco Rosso, 1992, dir: Hayao Miyazaki

Porco Rosso, 1992, dir: Hayao MiyazakiPorco Rosso is a lark, a word I'd use to describe nothing else in Hayao Miyazaki's filmography, not even the relatively frivolous Castle of Cagliostro or the non-stop high adventure of Laputa. Almost always there's a basic seriousness to Miyazaki's work, which in turn demands that we take it seriously, no matter that its subject matter might, on the surface, not seem to warrant such treatment. Partly, perhaps, it's a consequence of the sheer artistry involved, and partly that whatever he's making, there's always a depth to the world-building and characterisation, and partly it's that, even in his lightest works, themes tend to creep in around the edges, along with an awareness that, however much we might wish otherwise, the world isn't always a safe place full of good people.

Porco Rosso sort of still has all that. It would be hard to claim otherwise of a film that spends its entire running time under the encroaching shadow of fascism and ends by acknowledging that the high times it's shown off for 90 minutes are done with, never to return. Heck, our hero is a former soldier with a tragic past that he's trying to outrun, outlast, or perhaps just give as little thought to as possible. But he's also, like, a pig. I mean, a humanoid pig, sure, who wears clothes and can talk and fly a plane and do basically all the things people do, but nevertheless, a pig. And the film doesn't dance around this, so that we can never forget for an instant we're watching a movie about a humanoid pig who's also a fighter pilot. But even if that weren't the case, even if Porco Rosso the character - it means "Red Pig", see what I mean about not letting you forget? - were merely a rather Humphrey Bogart-coded tough guy making his mercenary living taking out sky pirates above the Adriatic, this would still, I think, be light-hearted in a way practically nothing else Miyazaki put his mind is.

This is amply illustrated by the opening sequence, in which a band of said sky pilots semi-inadvertently kidnap a class of school girls, who couldn't possibly be less nonplussed about the situation, and don't start to take it any more seriously once Porco arrives to rescue them via the questionable means of shooting their plane down. This ought to be at least mildly concerning, but since no one within the film is concerned - not the kids, not the pirates, and not our hero, who, to be fair, is suitably careful in picking his shots - we the viewer can't be concerned either. And so it goes: though serious things will happen, and though the spectre of fascism is always hovering close by, nevertheless the overwhelming mood is one of joy, because who wouldn't want to live in an alternate mid-war era when mercenaries and sky pirates fought thrilling battles in one of the lovelier places on Earth?

I think we can safely assume that Miyazaki did. More than anything in his CV, this feels like not merely a passion project but a reward for reaching a point in his career where he could make something so wilfully odd and go so all-in on the one obsession that's been a constant across practically all his work: that of flight and particularly the brief age of mechanised flight we see portrayed here, in which the nascent science of aviation relied as much on luck, persistence, and magical thinking as it did on - well, science. Porco Rosso is brazenly obsessed with this stuff: the entire middle act is effectively just one scene after another of Porco's plane being repaired, while what plot there is ticks away gently in the background. It ought to be deadly dull for anyone who doesn't share Miyazaki's passion, but then Miyazaki's a man never bettered at expressing through the medium of animation precisely why he feels as strongly as he does about any given topic. Plus, by this point we have the film's secret second protagonist in play, Fio the teenage mechanic, and Fio is fervent and open and excitable in all the ways Porco isn't, such that we want her to succeed almost as much as we want to see Porco back having thrilling midair duels.

Because the advantage of having a director indulging himself on a subject he's wildly enamoured with is that he throws everything at the flying scenes, pushing the medium about as far as it will go and indulging in sequences that would send most animators scurrying for the hills. Water is tough to animate; complex objects moving in three dimensions are tough to animate; it follows, then, that no one in their right mind would build their hand-drawn animated film around aircraft fighting mostly over the ocean. But passion projects aren't meant to be pragmatic, are they? And if I were to really nit-pick, I might add that they're maybe not always meant to be loved, either, since they're made, first and foremost, for their creators. Having had nothing but positive things to say, I'd have to admit that, for me, Porco Rosso is still lesser Miyazaki. Granted, that's barely a criticism, just an acknowledgement that the film, while delightful, is a little trivial-feeling in the company of masterpieces - though from anyone else it would certainly be at least a fondly remembered cult classic, which goes to show what a stupid bar for Miyazaki films holding them up to other Miyazaki films is.

Ocean Waves, 1993, dir: Tomomi Mochizuki

Ocean Waves, 1993, dir: Tomomi MochizukiOcean Waves was a departure for Studio Ghibli in just about every possible way. The standout, of course, was that for the first time they'd be putting out a work by someone other than its two founding fathers, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, a notion they'd flirted with before with Kiki's Delivery Service - and we've seen how that went. But this time, Miyazaki and Takahata were serious: Ghibli had to be more than just the two of them, and so it was time for a project that gave some of their hot young talent a chance to shine. Only, by way of mitigating the obvious risks of putting out a Ghibli project without the name of either of its two resident geniuses attached, it was going to have to be something a little more contained in scale: a TV movie with a suitably smaller budget and less ambitious animation, and a story to match, not a sweeping epic but a high-school drama confined to a handful of locations, with a 72-minute running time that would barely quality it as a feature film in the West.

Ocean Waves went over-budget, of course; even without Miyazaki and Takahata, Ghibli was still Ghibli. Nevertheless, what Tomomi Mochizuki eventually delivered was effectively what the brief had demanded, which perhaps inevitably left it as noticeably cheap-looking by comparison with their previous output and comfortably the worst film they'd released up until that point. But let's flip that on its head and clarify my position early: even if Ocean Waves was, in 1993, Ghibli's least great film, that's not to say it wasn't pretty great in its own right. And cheapness, too, is extremely relative: there's some jolting animation that would have looked out of place in, say, Laputa, but there's also some lovely and effective backgrounds and some incredibly nuanced character animation, that being a speciality of Mochizuki's, as he'd proven with the similar and thoroughly wonderful Kimagure Orange Road: I Want to Return to That Day five years earlier. Ghibli's idea of budget animation was not anyone else's, then or now, and there have been no end of cinematic releases that couldn't hold a candle to their idea of made-for-TV.

The same goes for the narrative. In no way did the shift in material mean that Ghibli were abandoning their standards for smart, empathetic, complex storytelling. Though, granted, on the surface, Ocean Waves offers a fairly traditional coming-of-age tale centred around a high-school love triangle: in the coast city of Kōchi, close friends Taku Morisaki and Yutaka Matsuno both become involved with a new transfer student, the beautiful, troubled Rikako Muto. For Matsuno, that means immediately falling for her and doing practically nothing about the fact, while Morisaki, our protagonist, inadvertently finds himself developing a more complex relationship with Muto, beginning when she borrows a large sum of money from him while on a school trip.

Common enough ingredients; however, it's fair to say that the traditions to which it hews closely were less ingrained then than now, and more importantly, that Mochizuki's interests go beyond the usual limits of the genres he was working in. Indeed, it would be hard to argue, for most of its running time, that the film cares much about the question of who might end up with who at all. Rather, it's the process of looking back on these events that preoccupies Ocean Waves, and especially the idea that, particularly in our most formative years, it's awfully hard to pick out what's important and significant to our lives from amid the chaos. Retrospect reshapes everything, and while sometimes that means distorting the past to fit a shape we'd have preferred or turning the molehills of small hurts into mountainous injuries, it can also mean that we see more clearly and understand much better, especially when it comes to gauging our own actions and making sense of those of others.

From all of that, you might fairly claim that Ocean Waves is a perfectly fine example of a particular type of story rather than the sort of ground-breaking masterpiece Ghibli had been trafficking in almost exclusively up to that point, and you'd be right, more or less. Yet I've always thought that it did break ground in its way, and while it's impossible to gauge, for me its influence routinely shows up in the many subsequent anime that treat the travails of teenagerdom with honesty and respect. Is it really a stretch to suggest that a film like A Silent Voice or a show such as Toradora! has a dash of Ocean Waves DNA in there? Whatever the case, if lesser Ghibli means doing the familiar exceptionally well rather than expanding the breadth of cinematic animation, that's a low bar I'm happy to live with. Granted, it has its flaws - the biggest, for me, being Shigeru Nagata's score, which goes too far in trying to dictate mood and routinely opts for the wrong one - and while I greatly admire Mochizuki, no one could claim he was on a par with his fellow Ghibli directors. Yet he proved himself, here and elsewhere, as being absolutely terrific at honestly representing the emotional landscape of teenage life, and while I can imagine an objectively better version made by Miyazaki or Takahata, it would surely lack much of what I admire in Ocean Waves, where the smallest gestures and moments carry such a wealth of meaning.

-oOo-

Five more posts to go, then, with the big 150 seeing the end of our Ghibli tour. In the meantime, there's plenty of interesting stuff left to cover, at least by a given definition of interesting that assumes everyone involved to be hopeless vintage anime nerds. There's a few more VHS-only releases, and more surprisingly, a handful of things that made it as far as DVD and even Blu-ray - in part because there's a classic or two I've neglected and need to tick off for the sake of completism. On top of all that, there's likely to be an Armored Trooper VOTOMS special, what with it producing a quite hefty number of spin-offs across the eighties and nineties, and the only real question mark comes down to whether I can finish watching the TV series in time. I mean, I will, it's really good, but damn is there a lot of it. Anyway, that certainly won't be next time, so expect a bunch of stuff you've probably never heard of...[Other reviews in this series: By Date / By Title / By Rating]

April 29, 2025

Drowning in Nineties Anime, Pt. 144

There's a very good chance you haven't heard of UK anime distributor Western Connection. Actually, it would be strange if you had; they only ever released on VHS, managed to put out all of about two dozen titles, then vanished without a trace. And what they did release was mostly pretty obscure, not to mention what a hash they generally made of doing so, with badly timed subtitles, tissue-paper-thin inlays, bafflingly worded descriptions, horribly cheap and unreliable tapes, and a money-saving hack of cutting out episode credits to pass off OVAs as films. Heck, those weren't even their worst offences, as we're about to see - because, yes, this time around we're looking exclusively at titles from this most would-be-notorious-if-anyone-had-heard-of-them of distributors! So let's see what mess they managed to make of Slow Step, Dancougar, Galactic Pirates, and Hummingbirds...

Slow Step, 1991, dir: Kunihiko Yuyama

Slow Step, 1991, dir: Kunihiko YuyamaUpon starting the second of Slow Step's five 45-minute episodes, a couple of things occurred to me. The first was just how much had been set up in the first episode, for all that it had seemed to be ambling along in a fairly aimless slice-of-life mode - yet here we were and there were numerous characters in the mix with multiple plot strands around them, half of which had crept up on me unawares. Which led directly to the second revelation, that I was already thoroughly caught up in those character dramas and eager to find out how things would pan out.

This, it turns out, is basically the game Slow Step is playing throughout, ushering its plot and cast towards you with the lightest of touches while at the same time developing them with sufficient care and attention that it's hard not to get absorbed. I guess, then, that a third surprise was the realisation that I was watching something kind of special: superficially familiar in a bunch of ways, sure, but stamping its own personality on well-worn themes and even sometimes using that familiarity to surprise. For example, by the beginning of episode two, our female lead Minatsu has managed to stumble her way into a situation where she's dating two different boys, one of them while wearing a fairly obvious disguise. It's remarkable how plausibly we get to that point, and the disguise, which amounts to a wig and glasses, is obviously preposterous, but the character designs sell it nonetheless. However, with so much vintage anime behind me, I was starting to dread the narrative convolutions that would be needed for Minatsu to keep her double life up and how tired that was likely to get with another three hours of running time to go.

Only, Slow Step doesn't do that. The dual identity shenanigans last for precisely as long as they need to, and when Minatsu's charade inevitably falls apart, it does so in a manner that both advances and deepens the plot - which, remarkably, is how more or less everything works. We have not one but two interlocking love triangles and a show that's both a baseball anime and a boxing anime, but somehow none of those elements stumble over each other or detract from the whole. The sports bits arguably gets the shortest shrift, but only in so much as their value, asides from providing a bit of action, is in how they matter to and affect the characters. Even the comedy is never there purely for its own sake, with a general lack of overt gags or goofiness. And for all that, Slow Step manages to be awfully funny when it wants to be: I didn't laugh constantly, but I laughed hard in a fair few places, and often it was at a joke that had been gathering steam in the background only to catch me off guard at the crucial moment.

The writing, then, if I haven't already made that clear, is very good indeed. How much of that we can pin on Manga creator Mitsuru Adachi I daren't say, since I can't find a credit for a scriptwriter anywhere, but it's certainly splendid source material: Adachi, as I understand it, was quite a big deal in Japan, yet for whatever reason his work has barely found its way to the West. Our loss, clearly, and all the more so if this is the sort of adaptation he gets. I've had cause to say nice things about director Kunihiko Yuyama before now, and while he's not up to anything radical here, with the animation rarely having to do much besides make the most of Adachi's charming designs and keep the sports sequences lively, he certainly deserves kudos for the spot-on pacing and nice use of colour palate to build mood. As stylistic choices go, it's all familiar stuff, but familiar stuff done so impeccably that it feels awfully fresh and exciting nonetheless, which is really Slow Step all over.

Dancougar, 1987, dir: Jutarô Ôba

Dancougar, 1987, dir: Jutarô ÔbaBefore we can begin to talk about Dancougar in terms of content, we need to get past what it was and what Western Connection did with it. Most of that is the sort of sneakiness and shoddiness we've grown awfully familiar with in this long tour of vintage anime, and if you've made it this far, you'll hardly blink an eye at the discovery that what Western Connection put out as a standalone film was in fact an edited version of the three-part OVA God Bless Dancouga, second sequel to the 38-episode show Dancouga - Super Beast Machine God. Granted, while there's scant effort made to reintroduce the concept or characters, it remains a bit more forgiving to the unfamiliar viewer than that might imply - and a good thing, too, since pretty much every viewer would be unfamiliar when this was dropped into UK stores because said TV show hadn't been released outside of Japan. But we're still not really breaking new ground, and though we might add in Western Connection's bargain-basement production standards, none of that was unique to them either.

You know what was? Releasing a title with the edges of the animation cells in shot, that's a new one on me. I concede here that I might not do the best job of describing this, because I'm nowhere near having the technical knowledge to explain how Western Connection botched as badly as they did, but essentially, there are shots - and not just a few! - where the images appear unfinished at the top and bottom of the picture. That unfinishedness is nothing weird in and of itself, it's how hand drawn animation was done in those days: you painted what was intended to be visible in the finished product and fudged the rest, and of course it would never occur to an animator that someone might be bonkers enough to release their hard work in such a state. The practical effect varies from distracting to incoherent, since sometimes your brain just registers that something looks kind of off, but sometimes characters are missing their legs and appear to be floating in mid-air. Put it all together, though, and it's the sort of bewildering mistake that the best anime in the world would struggle to survive.

If Dancougar is hardly that, it's fine for what it is, which is to say, an obviously unnecessary sequel that has all the usual problems unnecessary sequels are prone to, like having to spend an inordinate amount of time re-establishing its setup and then introducing a new conflict. And to its credit, it even plays with those issues a little: there's an interesting thread teasing the notion that all our heroes have accomplished until now is to get rid of an external threat, leaving the usual bad actors to make everyone's lives miserable, since it hardly takes an alien invasion to make human society rubbish. Had more been done with that idea, we might actually be on to something, and once it becomes apparent where everything's leading in the closing third, it's hard not to be disappointed, especially if you're one of those viewers new to the franchise who were naively hoping for a climax that didn't rely heavily on foreknowledge you couldn't possible have.

Admittedly, if you can get past Western Connection's ruinous cockup, the animation's rather nice, particularly during the giant robot action; but then there's not enough of that, and aside from the plot briefly threatening to go to interesting places, that's about the only significant positive I had. Would that have changed if I'd been familiar with the rest of the series? Marginally, perhaps, in that knowing the cast might enliven some of the character drama that bogs down the opening minutes; but I do think that, Western Connection's astonishing ineptitude aside, what really harms Dancougar is the sense that this story doesn't need telling and everyone new it. So I guess we can be glad that what they chose to ruin in so unique a fashion wasn't some lost masterpiece but a serviceable, disposable sequel made for no other reason than that somebody supposed it might sell.

Galactic Pirates, 1989, dir's: Shin'ya Sadamitsu, Katsuhisa Yamada, Kazuo Yamazaki

Galactic Pirates, 1989, dir's: Shin'ya Sadamitsu, Katsuhisa Yamada, Kazuo YamazakiOne of the nice things about Western Connection was that they didn't generally go in for dubs - assuming you're like me and have no love for them, which is a big assumption, I'll admit, and probably in a perfect world they'd have done what the majority of publishers at the time did and released in both formats. But they didn't, and because of that, the vast bulk of their titles are subtitled, a fact of which I, at any rate, have been glad. But then we come to Galactic Pirates, which bucks that trend in a big way. For not only was it solely put out as a dub, it's the sort of dub you're most definitely going to have strong feelings about. And for most of the presumably small number of people who ever experienced it, those feelings were no doubt negative, because it's obvious within seconds that notions like respect for the material and restraint and faithful interpretation were not so much off the table as never in the room to begin with.

This manifests most obviously in a volume of swearing that would have put the curse-happy folks at Manga to shame and in the decision by one of the leads to play his character - a human-sized, talking cat, mind you - as though they'd just wandered in from a particularly tacky seventies Blaxploitation movie. Since the cat's black, you see? It's certainly a bold choice, and we might say the same for the director who didn't shoot the idea down immediately and the rest of the cast who didn't march their colleague out into the carpark for a sound kicking. And yet, I dunno... it sort of works? Oh, not in the traditional sense of good dubbing, in that it never stops being wrenching and obviously apart from the source material. But it does have a certain "go big or go home" quality, and the performance, in itself, has a measure of enthusiastic charm, and sometimes it brings a spot of humour that wasn't there on the page, and I can't honestly claim I hated it. In fact, from the perspective of someone with no time for dubs, this one sort of worked for me, and make of that what you will.

That is, anyway, on the level of the performances, and to some extent the humour, if you can get past the tendency to chuck in swear words in place of actual jokes. And since Galactic Pirates is a comedy above all else, that actually gets us a fair way. But there is a plot, quite the convoluted one in fact, and where the script translation - by someone named Dr. D. Shoop, who I'm inclined to suspect may not have been a real doctor - falls down is in losing said plot at every turn. What's not gags and swearing seems to consist entirely of proper nouns, many of them variations on "cat" - a word that may be one of our protagonists, one of our villains, or a sentient AI that makes imagination a reality, depending on context - and following along winds up somewhere between a chore and an impossibility. I couldn't manage a plot summary, and if I did, it would disintegrate by the last episode, by which point numerous characters and factions are following various agendas that seem to relate only tangentially to each other.

That's a problem, obviously, but it would be worse if there wasn't the impression that Galactic Pirates was always meant to be chaotic and that the script is, at worst, exacerbating an existing and somewhat intentional issue. More to the point, the plot doesn't matter all that much; indeed, if there's a real flaw here, it's that the complex but aimless narrative gets the emphasis it does when the comedy, characters, and action are what works. Thankfully, those better elements get foregrounded more often that not, with the wider story frequently sidelined almost entirely. The second episode, for example, features a baseball match in which no-one knows how to play baseball, or even can agree on whether hand grenades and intervention by sentient spaceships are allowed, but everyone argues incessantly over the rules nonetheless, and it's genuinely hilarious in places. If nothing else is quite that good, we never go too long without a solid joke or cheerfully weird concept to liven up events, and even in the weaker moments, distinctive designs and some fairly impressive animation help keep things lively. Top it all off with an English-language heavy rock soundtrack by metal band Air Pavilion, which is somehow better for being such a weird fit for the material, and you're left with an interesting curio that works more often than not, despite - and very occasionally because of - the less-than-ideal treatment it received at the hands of those wacky folks at Western Connection.

Hummingbirds, 1993, dir: Kiyoshi Murayama

Hummingbirds, 1993, dir: Kiyoshi MurayamaIt's obviously bad practice to review the title you were expecting rather than the one you got, and yet the version of Hummingbirds I had in mind makes so much more sense than the one that was actually released that I had a hard time getting over it. If you have an anime in which, for reasons unknown, the Japanese military has been entirely privatised and the only ones daft enough to take them up on the offer are idol groups, you'd surely think the central joke would be along the lines of, "Wouldn't idols make terrible pilots, on the grounds of them not having any of the relevant skills and there being basically no connection between being a popular musical performer and controlling a piece of state-of-the-art military hardware?"

Hummingbirds begs to differ. Instead, our five protagonists, the Toreishi sisters, are all hotshot pilots to begin with (despite their youngest member being all of 12 years old) who happen to also want to be idols, and so are uniquely well suited to these bizarre circumstances. And I'm all for avoiding obvious jokes, but there's nothing to say an obvious joke can't be funny, and by the same measure, dodging one is really only a virtue if you have another to replace it with. I've read reviews that suggest Hummingbirds is a biting satire, but personally I couldn't see it: it has little to say on the topics of either the Japanese military nor idol culture, except for noting in passing that the two would make for quite the awkward fit. Indeed, I'm not even sure we can regard Hummingbirds as being primarily a comedy of any stripe.

With all of that out of the way - and I do wish I'd known it going in, so perhaps it's worth so much emphasising - we can finally consider what Hummingbirds is rather than what it isn't and acknowledge that the show has quite a bit going for it. The animation, for one thing, is mostly pleasing, particularly in the air combat sequences, which generally look pretty great, albeit at the price of some occasionally rough character work elsewhere. After the action, most of the money seems to have gone on the song and dance numbers, which are as regular as you'd expect from a show about idols. You might also expect some really standout tracks, and thus find yourself mildly disappointed, but everything's catchy and certainly good enough that having the brakes jammed on for five minutes of musical interlude never gets annoying. And the cast are a charming bunch to be around; the sisters are a little indistinguishable beyond their effective designs and obvious age differences, but in episode two the rival Fever Girls arrive and bring a considerable spark to the proceedings, something the creators some to have realised given how much they become the centre of attention in the latter half.

So a neat four-episode OVA that fails to exploit the daftness of its core concept, but opts instead for being an appealingly character-led show about idols with solid production values and plenty of catchy tunes, along with some unexpectedly exciting bursts of action. Put like that, it's hard to fault Hummingbirds, and I strongly suspect that when I return to it, as I'm sure I will, I'll enjoy it even more for taking it on its own considerable merits. Which would be a nice, positive note to end on, but since this is the Western Connection special, we'd better take a moment to consider how said distributor managed to muck up this particular release. Only, this time around, it's slightly tragic, in that they put out just the one volume, containing the first two episodes, before they finally went bottom up. What's worse, it's a solid release, perhaps suggesting they were getting their act together towards the end. Thankfully, all four episodes - under the original, obviously better title of Idol Defence Force Hummingbird - are up on YouTube, which is surely a better option than tracking down a phenomenally rare video tape and then feeling sad that you'll never get to see the ending.

oOo-

I suppose it would have been best if these titles had sucked, given that it's all but impossible that any of them will see the light of day ever again. Yet I'm personally glad that they didn't, and that Western Connection, for all their eccentricities and sometimes almost unbelievable lack of care and common sense, managed to put out such a respectable and cheerfully eccentric catalogue. Indeed, had they continued, and had their quality control improved substantially, I've no doubt they'd be one of my favourite distributors, and even with their small output, I have a definite soft spot for them: after all, aside from what we've covered here, they were behind stuff like Samurai Gold, Ai City, Grey: Digital Target, and The Sensualist, all of which I've raved about to a greater or lesser degree.Though they did also release Kama Sutra, so, yeah, maybe they got what they deserved.

[Other reviews in this series: By Date / By Title / By Rating]

February 26, 2025

Drowning in Nineties Anime, Pt. 143

There are a couple of themed posts on the way - 145 will be part two of the Studio Ghibli roundup, and 144 will be, er, not that - but before we reach those, there's more random stuff to be gotten through. In a change from recent programming, however, that doesn't just mean desperately obscure VHS-only releases. We have something that made it all the way to DVD, but also, and much more excitingly, we have a brand new Blu-ray release that's (sort of) never seen the light of day before in the West. Yes, the good folks at Discotek have been at it again, and altogether that leaves us with Luna Varga, I Dream of Mimi, Digimon Adventure, and Techno Police...

Luna Varga, 1991, dir: Shigenori Kageyama

Luna Varga, 1991, dir: Shigenori Kageyama

Luna Varga, a four episode comic fantasy OVA of a flavour that was everywhere in anime at this point, has essentially one idea going for it, and whether that one idea is stupid, awesome, or a bit of a both is surely in the eye of the beholder. Towards the end of the first episode, our plucky heroine the princess Luna, whose kingdom is under assault from the local warmongers, finds herself in a hidden dungeon beneath her castle and uncovers a secret weapon that her family has squirrelled away for just such an occasion, in the shape of a giant dinosaur-thing by the name of Varga. The only kink in this good news is that Varga will only function with the addition of a brain, and Luna will need to be said brain. And while there are no end of ways that might have been represented, this being anime from the beginning of the nineties, there was only one they were likely to go with, and that is of course Luna sitting on Varga's head butt naked.

The butt nakedness has mostly been addressed by midway through episode two, which isn't to say Luna won't be exposed quite regularly, in part because Varga's more portable form is a tail that protrudes from exactly the part of Luna you'd expect a tail to protrude from. And like I said, you can respond to all of this in one of two ways, or possibly bounce between the two extremes like I did, but at any rate, what we have here is four episodes of a scantily clad woman riding about on a dinosaur that's attached to her nether regions. Though having said that, I'm reminded of how much of Luna Varga busies itself with other stuff, such as wacky comedy, perhaps because the scenes where Luna and Varga are in full-on kaiju mode are invariably the action set pieces, and Luna Varga is rather thrifty by early nineties OVA standards - though thankfully Kageyama's energetic direction and some nice designs ensure that it never looks offputtingly cheap.

Nevertheless, I can't convince myself the version of Luna Varga we got quite works, and that's frustrating, since it really feels as though it ought to. It is, after all, effectively being a mech show where the giant robot is replaced by a giant monster and the boring male protagonist is replaced by a feisty princess, and that's surely a solid enough twist to keep a four episode OVA afloat. In fairness, it's not as if Luna Varga doesn't manage to get itself over the finish line reasonably intact, only that there's the persistent sense that nothing's quite functioning as well as it should be. The surrounding cast are varied and entertaining, and there are hints of intriguing world building: two of said cast, for example, can turn into animals on a whim, which is apparently a thing some people can do. But almost everything occurs more as an amusing idea than as meaningful content, and thus ends up feeling slightly like filler on the way to a final encounter with the big bad that's an awfully generic note to end on.

I guess my point is, if you're going to have a central premise as outlandish as "princess has dinosaur attached to her butt" and then pepper it with dark wizards who can only summon pterodactyls and people who turn into flying cats at the drop of a hat, you probably need to accept that you've gone to a weird place and run with it, whereas what we get here somehow ends up making all of that feel rather generic. As someone who has quite a fondness for generic nineties anime comic fantasies, I wasn't overly put out by that, and goodness knows there are plenty worse examples of the form, but there's no denying that an opportunity for something much more memorable was sitting there in plain sight.

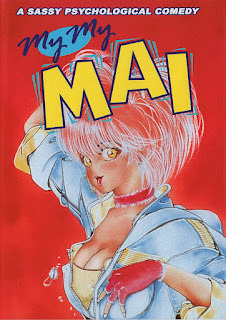

I Dream of Mimi, 1997, dir: Masamitsu Hidaka

I Dream of Mimi, 1997, dir: Masamitsu HidakaOK, yes, I'm afraid I'm breaking the "no hentai" rule yet again, and again it's because some rando on the internet claimed that something was good enough that, with a bit of squinting, you could enjoy it on its non-pornographic merits. Now, I don't really agree, but I can sort of see how someone might have come to that conclusion about I Dream of Mimi, if only because there's some genuinely nice animation here, and some unusually good character designs, and a general sense that more than the usual thought has gone into the visual side of things, and not just for the sorts of reasons that hentai tends to focus on. Which is to say that by "good character designs" I don't just mean "well-drawn boobs". Though that too.

I care a fair bit about nice animation, enough so that I can ignore some pretty hefty failings, so that's a good start, and it's not even as if I Dream of Mimi has nothing else going for it: the humour worked enough of the time to keep me routinely amused, and since this is primarily a comedy when it's not being hentai - and quite often when it is being hentai - that's certainly a win. And the sexy stuff is all consensual and not especially graphic and relatively well woven into the plot, so in theory it's not as if its being hentai detracts from its other merits, either.

But in practice, by trying to do something awfully familiar but with a mildly pornographic twist, I Dream of Mimi leaves itself with not enough time to tell a decent story or to tell the one it's set itself very coherently. For what we've got here is one of those "nerdy guy gets magical dream girlfriend" shows that were, and no doubt remain, awfully common in the world of anime. They always had the potential to be kind of gross, and I've commented before on how miraculously they generally manage to sidestep being the worst version of themselves: heck, Oh My Goddess! is a personal favourite, and I doubt I could explain that to someone without making it sound deeply icky. Indeed, I remember singling out Video Girl Ai in my review on precisely that point, and being gobsmacked that it somehow wrung something heartfelt and witty from a premise that had every reason to be all sorts of unpleasant.

I won't quite go so far as to say that I Dream of Mimi is the version of Video Girl Ai that I praised Video Girl Ai for not being, but the possibility certainly occurred to me more than once while I was watching. Out story involves the nerdish Akira, who buys a computer from a dodgy fellow in the street and is surprised when he gets home that said computer is a naked girl, whom he eventually names Mimi. The show, incidentally, doesn't seem to know the difference between computers and robots, or indeed between computers and sexbots, that being effectively what Mimi is, since she immediately pledges herself to Akira for all eternity and seemingly has no functions that aren't powered by... Well, look, let's just say that if you'd care to hazard a guess at what Akira has to do to expand her RAM, or where her software needs to be inserted, then, unless you have the cleanest of minds imaginable, you're almost certainly right.

Given that we're in the realms of hentai, I guess there are plenty dumber reasons to jam a bunch of sex scenes and an awful lot of nudity into what's primarily a romantic comedy. But I Dream of Mimi never quite figures out how to balance those elements. Given that Mimi is a sex-powered machine, and an awfully possessive and demanding one at that, the romance doesn't function well at all, and the comedy keeps getting sidelined for what turns out to be the main plot, some action-heavy business about invading American computers that in turn doesn't gel with the ongoing business of Akira trying to hide from his friends that he's inadvertently married a nymphomaniac PC that looks like a teenage girl, and all in all this feels like a title that needed to pick fewer lanes and stick to them. If the concept appeals, it's certainly easy to imagine a worse version, and indeed a sleazier and more charmless version, but unless you're absolutely determined to have sporadic sex scenes in your magical girlfriend show, there are much better takes on that over-done setup to be had.

Digimon Adventure, 1999, dir: Mamoru Hosoda

Digimon Adventure, 1999, dir: Mamoru HosodaDigimon Adventure is quite a pointless title to be reviewing, but pointless for different reasons to how most of these reviews have been over the last two or three years, given that, thanks to Discotek and their recent Blu-ray, you can actually buy it in normal shops for a relatively reasonable amount of money. On the other hand, you almost certainly know in advance whether you'd want to - are you a Digimon fan, a Mamoru Hosoda fan, or both? - and given that Discotek's release includes the first three movies and that, at twenty minutes, Digimon Adventure is far and away the shortest, the odds are stacked against anyone splashing out for it in isolation, especially when they're also getting Hosoda's well-regarded follow-up Our War Game.

The logical thing to do, then, would be to review the release rather than the individual film. But I'm not going to do that because only Digimon Adventure came out during our decade of choice, and even if I do break my own rules here so often that it's become a running joke, I'm in a stubborn mood today. Yet thankfully, none of that matters, because if you fall into either of the categories mentioned above, then the first Digimon film, in spite of its miniscule running time, is damn near good enough to warrant the price of entry on its own.

Though, I dunno, maybe that's a little truer if you're in the Digimon fan camp? Hosoda brings an unusually visible amount of directorial presence, far more than you'd expect for a property like this, but I don't know that we can call Digimon Adventure a Hosoda feature in the way that, say, Wolf Children or The Boy and the Beast, or even his later franchise entry, the One Piece film Baron Omatsuri and the Secret Island, are. Yet Digimon Adventure manages to be a perfect approach to what a franchise movie should be, while at the same time feeling as if it's doing quite a bit more than what that would call for. The story is as simple and slight as can be - some years before the start of the TV series, Tai and his little sister Hikari have their first encounter with a digimon, then there's a big fight - but feels considerably more substantial and nuanced than that suggests. It starts out light-hearted, gets awfully dark before the end, and has as many delightful character moments as films four or five times its length. Plus, Hosoda being Hosoda, and having his shtick down apparently from even very early on in his career, the animation is wonderful, and in most of the ways his later work would feature wonderful animation, with tons of charm and subtlety of expression to the scenes that are primarily about two children trying to make sense of the cute but baffling monster that's inserted itself into their lives and a real sense of scale and weight to the climatic battle.

And you know what? I've changed my mind. In spite of a rather high price tag - sure it's three movies, Discotek, but they have a combined running time of one quite long movie! - I'd recommend this to any vintage anime fan, and to anyone who's interested in following Hosoda back to his roots. I know I said I wouldn't review the release, but Our War Game is pretty wonderful, spoiled only by some dated digital animation work and the fact that its director would return to the same well with both Summer Wars and Belle, leaving it feeling like something of a rough draft - albeit the rough draft of a skilled craftsman who already had most of what he needed to do figured out. And the third film, Hurricane Touchdown!!, is a perfectly serviceable, entirely rote franchise movie, which is okay because it just emphasises how elegantly Hosoda balances an auteur's instincts with the needs of his material, and so makes Digimon Adventure seem all the better for how much more it accomplishes with less than a third of the running time.

Techno Police 21C, 1982, dir's: Nobuo Onuki, Masashi Matsumoto

Techno Police 21C, 1982, dir's: Nobuo Onuki, Masashi MatsumotoI try not to repeat what others have said better than I could, so rather than detail the origins of what would come to be known in the West as either Techno Police 21C or plain old Techno Police (I'm assuming, based on no evidence, that it had a different title in Japan), I'll just point you to this review. But short story even shorter, since it's handy information to know in advance: what we have here was intended to be a TV series that never got off the ground, and in desperation, the extant footage was cobbled together into something that, if you were being very generous in your definitions, could be regarded as a movie.

Though why anyone would be generous towards Techno Police is beyond me, since it isn't very good, and almost certainly wouldn't have been a good TV series, perhaps struggling its way up to "cheap and generic" in its better episodes. Here, those better episodes get translated into better scenes, of which there are maybe two, though I can only remember one, so perhaps I'm already being too kind. There simply isn't anything to get excited about, and I do wonder how things ever got so far as they did, since surely not even in 1982 was "futuristic cops are partnered with robots" such a ground-breaking premise that you could hang an entire TV show - or movie - off it without bothering to concoct anything in the way of interesting characters, settings, narrative or themes? And if I'm wrong and Techno Police had genuinely come up with a notion so radical and ground-breaking that it had to be thrust into the world by some means or other, even then, I refuse to accept that more couldn't have been down with it than ... well, than nothing, since Techno Police is content to go nowhere with its core idea. The closest we get to a hook is that the robot partners are essentially new-borns who have to be trained in the basics of police work and social behaviour, which translates to a brief montage of wacky misunderstandings, while also offering a fine example of the level this is operating on, given what an awesomely stupid jumping-off point "robot cops that don't know how to be cops" is.

Still, the robots serve us better than their human counterparts, since they at least get some mildly appealing designs, whereas the homo sapiens of the cast are bland as bland can be, both in appearance and whatever passes for character. They're not even stereotypes, and the only two traits I can recall about any of them are that the hero, Ken, is introduced to us as having a thing for trashing his police motorcycles that you might imagine would figure somewhere in the subsequent plot but doesn't, and Eleanor, the one who's a girl, gets an hilarious line in which she seems to suggest that getting into tanks is somehow her speciality. There's a third team member, but even looking at his picture on the cover and having watched this thing yesterday, I can't recall a single detail about him, and there are some recurring villains who I've also largely forgotten, and if there's a lower bar to clear than making your anime villains remotely memorable, I struggle to think what it might be.

Needless to say, the animation is resolutely threadbare, leaving multiple action sequences that feel like they probably ought to be mildly exciting as anything but, and an early score by Miyazaki's go-to guy Joe Hisaishi serves only to illustrate that even geniuses have to learn their craft somewhere. And with all of that said, and since I always try not to be wholly negative, I'll close by admitting that, in its incredibly modest and inept way, Techno Police did kind of charm me. It's not hatefully bad; you can sort of feel that somewhere deep beneath its bland and clunky exterior is the heart of something that somebody genuinely cared about - woo, robot cops!! - and however badly that spark got lost along the way, it wasn't altogether extinguished. Of course any modern child would be repelled by its incompetence and immense datedness, but I can imagine a kid in the late eighties stumbling across Techno Police on TV and kind of digging it for the course of eighty minutes.

-oOo-