David Tallerman's Blog, page 8

November 30, 2020

Drowning in Nineties Anime, Pt. 88

If you were watching anime or reading manga in the eighties and nineties, you were bound to come across the works of Rumiko Takahashi sooner or later: if Urusei Yatsura didn't do it, then Ranma 1/2 or Maison Ikkoku would get you. Takahashi's most famous works were staggeringly successful, and practically inescapable.

But they were far from being all that she produced, and in the eighties, four of her shorter titles were given the OVA treatment, to be released under the collective banner of the Rumik World series. Sad to say, the only Western release those four OVAs would get was on VHS, from Manga Video in the UK and U.S. Manga Corps in the US. But is that to say they didn't deserve to make it onto DVD, or were there darker forces at work? Since I was curious enough to track them down and to dig out my old video player especially, let's find out, with a deep dive into the Rumik World and Fire Tripper, Laughing Target, Maris the Wondergirl, and Mermaid Forest...

Fire Tripper, 1986, dir: Motosuke Takahashi

Fire Tripper, 1986, dir: Motosuke TakahashiFire Tripper belongs to a particularly rarefied subgenre: what we might call time-travel romance, for want of a better term*. In feudal Japan, an infant girl escapes a bandit attack and her burning home by spontaneously vanishing, only to reappear in the modern day. The next we see of her, she's been adopted by the kindly pair who found her, renamed Suzuko, and has grown to be a teenager - at which point, a gas explosion casts her and the young boy, Shu, that she's looking after back in time once more, separating them and stranding her in the past. Before she can find her feet, Suzuko is rescued from a rape attempt by a young fighter, Shukumaru, who takes her back to his village and treats her with a modicum of kindness, enough so that she's not wholly put off when he starts talking about marriage. As for Shu, his T-shirt turns up mysteriously in the village, but there's no sign of the lad himself, for all that Suzuko devotes herself to hunting for him and Shukumaru grudgingly agrees to aid her.

For this to work, it needs to get two things right, the time travel shenanigans and the romance that ensues from them. So the fact that neither entirely lands is definitely a flaw. The former, I'd say, fares better, in that at least it's entertainingly convoluted. Obviously there's more going on here than we're immediately made privy to, and much of the pleasure to be had with Fire Tripper (and this tiny subgenre in general) is in seeing how its plot unwinds and comes to make some measure of sense. So, that of the two big twists along the way, one's so obvious that I had to assume I was meant to have got ahead of it and the other's only marginally harder to preempt is certainly another problem. Arguably worse, though, is the lack of any wider explanation: that Suzuko jumps between two time periods when her life is in danger from fire or explosions is presented as an irrefutable fact, and we'd just better deal with it, because Fire Tripper isn't wasting one iota of its running time on trying to justify it.

The romance, though, is considerably worse. At any rate, the version of the romance imposed by Manga's dub is worse; it's certainly possible that this would play better in its native Japanese. It's not a horrible dub, the intent is evidently to be true to the material and I'm always in favour of that, but neither of the leads seems terribly concerned with making us like their characters, and a romance between two unlikable people is tough to be on side with. Then again, since neither has a lot in the way of personality, or much room to develop in a plot that necessarily requires them to be swept from event to event, it's maybe the case that this could never have functioned as its needs to.

If I wanted to go on grumbling, I could mention some wholly run-of-the-mill animation and Takahashi's flavourless direction, which never does much to elevate the material. But here at the end, I'd rather acknowledge that, for all that I don't think Fire Tripper succeeds as it was intended to, it's not altogether a washout. You can only screw up a setup like this so far, because so long as the plot is sufficiently ingenious - and this one is, just about - there's pleasure to be had in seeing how the pieces slot together. Since the narrative is basically a puzzle we watch solving itself over the course of forty-five minutes, the flat romance and even the predictable twists are less of a problem that they'd otherwise be. Though there are much better such puzzle-box narratives out there (for my money, 2014's Predestination perfects the form to an unbeatable degree) they're also thin enough on the ground that a decent but flawed example remains enough of a curio to waste your time on.

Maris the Wondergirl, 1986, dir: Kazuyoshi Katayama, Motosuke Takahashi

Read the synopses of the other three episodes and it seems fairly clear what these Rumik World OVAs are going to be: fantastical Twilight Zone-esque stories with some sort of central supernatural gimmick and a twisty sting in their tails. So it's quite the surprise when Maris the Wondergirl comes along and throws all that out the window. Okay, arguably it does contain a gimmick of sorts: its core idea is that our hero Maris, being from the now-extinct planet of Thanatos, has the strength of six regular people, which she has to keep in check via a special harness lest her uncontrollable power destroy whatever happens to be near. And, thinking about it, I suppose there's even a twist ending of sorts, though it's more by way of a gag than anything. Because, and this is perhaps the biggest change from its fellows, more even than the shift from fantasy set in a reasonable approximation of the real world to a bonkers science-fictional universe: Maris the Wondergirl is a comedy.

A part of why this feels odd, I think, is that comedy is very much what Rumiko Takahashi is and was known for, and I'd decided based on no real evidence that the intention of these Rumik World episodes was to present another side of her oeuvre. Then again, this is a different brand of comedy than either Urusei Yatsura or Ranma 1/2, a little less goofy and a lot more dark, or at any rate more willing to watch its protagonist suffer. As we meet her, Maris is having a decidedly crappy time of it, and most of her problems boil down to her annoying super-strength: working as a space cop of sorts, we quickly learn that she routinely does so much damage on her missions that she's incapable of turning a profit. And even if that weren't the case, that her father and mother are respectively a drunk and a shopaholic, and also have a tendency to break everything in sight and then phone their daughter to beg for cash, means that the odds are against her ever getting into the black.

This all looks like it could change when Maris is offered the job of rescuing a captured billionaire. All she needs to do, aside from the actual rescuing part, is ensure that he falls madly in love with her and marries her on the spot. So off she sets, with only her partner Murphy for backup - Murphy, being, by the way, a nine-tailed fox that in the English version gets a broad Irish accent that's somehow the most perfect bit of dubbing I've ever encountered. And as to why Maris is partnered with a creature out of Japanese folklore, that isn't something Maris the Wondergirl ever feels inclined to explain, much as it's happy to leave a good portion of its world-building unexplained, in favour of taking every opportunity to chase after jokes or simply opportunities for general weirdness.

This is absolutely the right decision, and weirdly, not only for Maris the Wondergirl as comedy but for Maris the Wondergirl as science-fiction too. It's thoroughly great at the former: it's awfully nasty to poor Maris, but surreal enough that it never feels nasty, and there are some genuinely excellent gags along the way, right from the beginning and the narrator's stentorian assurance that what we're about to watch is not a true story. But at the same time, there's enough to the plot and setting that they don't just come across as a delivery mechanism for jokes; indeed, the background here feels much more thought through that in Fire Tripper. And while we're comparing, the animation and music are both a marked improvement, with some engaging pop interludes and Maris in particular benefiting from terrific character work. All of which means that, while I don't know that Maris the Wondergirl is necessarily a great Rumik World entry, seeming as it does too fundamentally different from the rest, in its own right it's a gem, one of the most charming and witty comic OVAs I've encountered.

Laughing Target, 1987, dir: Motosuke Takahashi

Laughing Target, 1987, dir: Motosuke TakahashiIf Fire Tripper had a single advantage, it was that it was dabbling in a very exclusive subgenre, puzzle-box time-travel romances not being exactly ten a penny. So that Laughing Target goes to the opposite extreme, opting for the sort of supernatural horror that you can barely move for in the anime world without stumbling over, and that it keeps one of Fire Tripper's significant weaknesses - that being director Takahashi, who put in such a lacklustre showing there - doesn't bode well.

So it's both a surprise and a relief that it ends up being the better title in almost every way. For a start, while the core elements are thoroughly routine, Laughing Target comes to them via an awfully nice angle. Yuzuru Shiga was pledged at a young age to marry his cousin Azusa, but in the years since, he's thought little of her, and by the time we meet him as a teenager, he's well established in a relationship with his classmate Satomi. So it's quite the disruption for both of them that, following the death of her mother, Azusa is coming to live with Yuzuru, and that she definitely hasn't forgotten that childhood promise, and indeed seems to have been planning her entire life around it. And much as that's bound to be a problem, it's a considerably bigger problem given that Azusa seems both a touch crazy and possessed of supernatural powers, surely related to an opening scene we witnessed in which she strayed into a mysterious other realm.

The reason this works so well is that everyone is basically sympathetic. Of course Yuzuru doesn't want to honour a promise he made when he was six years old, and of course Satomi doesn't want to give up her boyfriend so he can marry a relative he barely knows, but we're given enough insight into Azusa and the events that formed her that we can also understand why she's determined to see this through. She's as much a victim as the couple she's preying on, if not more so. And from a horror perspective, a situation where you're more or less rooting for everyone has considerable advantages. We don't want to see Azusu harmed any more than we do Yuzuru or Satomi - thanks to a solid dub, they're all easy to be on side with - and so the ever-increasing violence between them is that bit more discomforting.

This is helped by a far stronger performance by Takahashi, or perhaps by the fact that he's just better suited to the material: the expository stuff is still quite pedestrian, but he's an unexpectedly dab hand at laying on the creepiness, and while there's nothing here you could genuinely call scary, Laughing Target does a respectable job of getting under your skin on more than one occasion. Indeed, the flashback in which we learn how Azusa first manifested her powers is a genuinely effective piece of horror film-making, both in how visually striking it is and in how it shunts us through a number of troubling emotions, mixing a heady combination of alarm at what might happen to Azusa, disgust for the solution she arrives at, and sadness as we come to comprehend how this event shaped the present.

There is, in short, a good little horror film here, with a fine setup and some scenes that really land. But it's also not hard to see how it could have been improved. As with Fire Tripper, while we get enough answers that the result feels like a coherent narrative, there are plenty of questions left over, and some of those would definitely have been opportunities to tie everything together more neatly. In particular, Yuzuru and Azusa's family connection ends up feeling like a plot device, when surely there was more to be done with the hints that this all stems from some generations-old curse. Three quarters of the way through this series and I'm starting to suspect Takahashi was better at coming up with neat ideas than thinking them all the way through, but then again, these ideas are at least genuinely neat, and Fire Tripper does a respectable job of nailing the execution too.

Mermaid Forest, 1991, dir: Takaya Mizutani

Mermaid Forest, 1991, dir: Takaya MizutaniIt was Mermaid Forest that initially brought to me to this OVA series: of all of them, it's the title that's managed to sustain something of a reputation for itself, and it's often spoken highly of when Takahashi's work crops up. And yeah, I can definitely see why ... while maybe not the most distinctive of the four Rumik World entries, it's an exceedingly well-formed example of what it is.

Which is a vampire story, in essence, though part of why it feels so fresh is that it comes at that particular set of tropes from an appealingly different direction. Three of its main characters (four if we count a dog) are immortal, and one is very definitely surviving by dosing herself with human blood, though we're led to suppose that until the beginning proper of this story - that is, excepting a couple of important prologues - the blood has all been from corpses supplied by the village doctor, who's madly, unwisely in love with her. Towa, you see, was cured of a potentially fatal childhood illness by her sister Sawa, but at quite the cost: she was only saved by drinking the blood of a mermaid, and in Japanese folklore, consuming a mermaid's flesh grants the gift-stroke-curse of immortality. In Towa's case, it's also stuck her with a mutated arm that leaves her in incessant pain and constantly threatens to get out of control. Quite how human blood is staving this off is slightly unclear, but it does, albeit with diminishing results. And while Towa is convinced that a permanent cure could be arrived at if her sister would just let on where she got that cup of mermaid juice from, she's soon wondering about other solutions when two more immortals wind up in her home.

The mermaid element, so vital to the story, does a great deal to spice up well-worn ideas, and makes for an enticing combination, at once familiar and surprising. The result is a plot you can see the shape of from early on, but that still succeeds in throwing curve balls as it goes along: Mermaid Forest certainly has the most satisfying twist of these four titles, and the one that does most to retroactively reshape the material. It's never, it has to be said, remotely scary, and though there's a fair bit of blood and guts and the odd gross moment, it's rarely that horrifying either: quite where the 18 rating came from is anyone's guess. All else aside, though the animation's perfectly decent and director Mizutani does a competent job of keeping the narrative flowing, there's not sufficient flare to properly get under your skin; in those terms, Laughing Target was the better work of horror. But Mermaid Forest feels like the superior title in other ways, perhaps because it's based not on a short story but one section of a longer work. That definitely comes over, in largely good ways: there's a sense of scale that touches, albeit lightly, on what it might mean to live forever and how that experience might twist a mind or set it free.

Sadly, there's one aspect of Mermaid Forest that's as weak as anything in this series, and that's the dub: it has moments of abject terribleness, and none of the cast remotely shine, though the actress voicing Towa does seem to get to grips with her character by around the halfway point, thus mitigating the worst of the damage. It's a shame, though, and as with many of these dubs, goodness knows what Manga were thinking letting this crap out the door. But thankfully the material is sturdy enough to ride it out. The odds were against this being my favourite entry with Maris the Wondergirl in the mix, and I'd say Laughing Target about ties it, but nevertheless, Mermaid Forest does fine work in taking one of horror's oldest concepts and making it feel new, and that's enough to earn its enduring reputation.

-oOo-

Whenever I get close to shaking this vintage anime obsession, something wonderful comes along to drag me back in, and recently that's been these four Rumik World titles: individually they're good to great, but taken as a unit, they're a bit of a treasure, and I've thoroughly enjoyed my time with them. What's more, I find it deeply weird that nobody's ever rescued them on DVD or even blu-ray. Here as so often, the only solution for most people who fancy giving them a shot is Youtube, which is a shame, though certainly better than their being vanished altogether. As I say, there's a lot to be gained from watching all four in the order they were released, but failing that, it's definitely working seeking out the drastically underrated Maris the Wondergirl and the perhaps slightly overrated but still commendable Mermaid Forest.[Other reviews in this series: By Date / By Title / By Rating]

* Though weirdly, a subgenre that anime has explored quite a bit, with The Girl Who Leapt Through Time being another obvious example.

November 26, 2020

Six Tips For Surviving Novel Writing

Somewhat to my surprise, I seem to be writing a new novel. Given my currently not-so-great circumstances, it's hard to say exactly what the point is, but somehow it seems like the most reasonable of a whole bunch of unreasonable options. At any rate, that's inevitably got me thinking about the process, and the lessons I've learned over the course of doing this more than a dozen times already. And since I haven't altogether given up on the pretence that this blog is about my writing, I thought sharing some of that might be worthwhile.

This won't be anything so presumptuous as telling anyone how they should go about writing a book, because there are a million ways of doing that and any number of them are right. (Also, I'm pretty sure I already did that post way back when!) The most I can offer is a few conclusions I've come to after having tried numerous approaches to a greater or lesser extent, and given how much nearer I am to the beginning than the end of the process - past the 60'000 word mark, but this promises to be substantially heftier than anything else I've done - there's a definite theme here, centred around how to keep moving as it starts to sink in just what an enormous task you've set yourself. So, with that in mind...

Don't Rush In

Of everything here, I imagine this is the point most likely to be widely ignored, because many people absolutely swear by rushing in, and presumably it works for at least some of them. And, look, I'm not saying you have to have a detailed plan, though personally I can no longer imagine how I'd go about writing a novel without one, any more than I'd think of waking up one day and thinking "Hmm, maybe I'll climb Everest today" and setting out in my pyjamas. Still, not everyone's a planner, I get that, and planning isn't necessarily what I'm talking about. I guess it's more to do with facing up to those points where whatever concept has you so fired up feels that bit too sketchy. Maybe they'll have sorted themselves out by the time you get to them, but maybe they won't, and confronting them without the stress of weeks of work depending on the results can be a lot easier. What I've found is that ultimately I tend to reach a point where I know I'm ready to go, and mostly it's a sense that I haven't left any towering brick walls for myself to dash headfirst into at the worst possible moments.

Don't Sacrifice Your Momentum

This one probably depends on whether you've followed the previous suggestion: if you've charged in without much of a plan, chances are that eventually you're going to run out of steam, and when that happens, your best bet may well be to step back for a week or two and figure out where you're heading. Planning is always going to happen sometime, and if you'd rather do it in the middle than at the start, or in chunks along the way, then each to their own. But let's assume for the moment that you do have a plan and that it's basically sturdy. If that's the case, I've come to think the best approach in a first draft is to keep moving forward for as long as it's remotely feasible to do so, and hopefully right through to the end. If your plot's absolutely crumbling in your fingers then, sure, stop and take a breather, but if your plot's merely wobbling a bit, that ought to be a problem for the next draft. And while there's a definite appeal to heavily editing alongside your first draft, my conclusion is that it's better to keep that to a minimum. This time through, I'm experimenting with starting the day by doing a quick polish of yesterday's work, and that's definitely proving positive, but more than that and I suspect I'd just be trashing my confidence and risking skidding to a halt.

Don't Bore Yourself

This is more of a general point, and applies to all writing, no matter the length, but it's also one of the most important conclusions I've reached over the years, so let's include it. If there's a type of scene you don't like writing, there's a fair chance you won't write it well; if you find action a slog, or dialogue is something you want to hammer through to reach the good stuff, odds are that a reader's bound to notice that lack of engagement. And the best way to deal with this is to ask yourself what it would take for you to be excited by those sequences. Would you get more out of writing that dialogue if it was faster and peppier, or maybe if there were more character beats mixed in? What if you could shift the focus off the mechanical aspects of the action and onto the psychological effects, or vice versa? If you're feeling disengaged, it's vital to figure out why and even make that work to your advantage, because the alternative is great swathes of novel that you'll return to and be mortified by how visibly the energy levels plummet.

Avoid Feast and Famine

It's awfully tempting to push your luck when you're on a roll. Some days, the words won't stop coming, and why wouldn't you lean into that? Well, there's one reason, and that's how easy it is for your reach to exceed your grasp. I'm sure there are people whose wells never run dry, but for me, what I find is that a run of prolific days will inevitably result in a harsh crash. Writing is an enormously subconscious-driven task, and your subconscious can only do so much advance work; I have a theory that getting too far ahead of it is a big part of what people refer to as writer's block, a condition I've mostly been fortunate enough to steer clear of. But whichever way you look at it, novel writing is marathon running, and too many sprints will burn you out in no time. Add to that how easy it is to make wild mistakes or churn out seriously unpolished prose if you're caught up in mad dashes and it generally makes more sense to keep to a steady pace.

Don't Freak Out

There's nothing quite like the unadulterated panic of getting deep into a major project only to realise you've got something enormously, irreparably wrong. Or, I guess there is one thing like it, and that's when the same happens on a smaller, less horrifying scale: you're midway through a chapter and it hits you that this is where you ought to have started it, or that character you've spent three pages introducing is just taking up space and serving a purpose your existing cast were more than capable of covering. If you're anything like me, your first reaction will be to try and fix the problem as quickly and painlessly as possible, and your second reaction, once it's sunk in that quick and painless aren't on the table, is to run around shrieking and then hide under the bed. And I'm not saying that's a wrong response (okay, obviously it's a terrible response) but there are better options. And most of them revolve around hanging onto your calm and, if possible, deferring the problem until you've had time to properly digest it.

Don't Ignore the Small Achievements

Writing a novel is a major thing. It's easy to forget that, when there are so many trillions of books out there, but producing yet one more is still a herculean task. And if you're planning to wait until the very end before you permit yourself a pat on the back, you're going to be waiting a long time. Getting a chapter down is a big deal. Getting ten thousands words in the bag is a big deal. Heck, these days, making it out of bed and all the way to the computer without collapsing in a sludgy mound of despair is a big deal. In one sense, novel writing is very much an all or nothing exercise, in that, unless you're both extremely famous and dead, nobody's ever going to be interested in your unfinished opus. But in another sense, every step along the way counts toward the total, and you're fully justified in allowing yourself a dash of excitement, or even a small reward, at surviving another lap.

-oOo-

Okay, sure, that was more for my benefit than anyone else's. But while this might be mostly about me reminding myself that I'm near the start of a long road and need to hold the line for a good while longer without letting those brain-goblins devour my frontal cortex, I hope there are one or two other people out there who might find something useful here!

November 16, 2020

Drowning in Nineties Anime, Pt. 87

To the long list of things I promised myself I'd never do, because if I did, this whole exercise would go from downright silly to irredeemably ridiculous, then promptly went ahead and did anyway, we can now add picking up titles that were only ever released on VHS. We've had one VHS review already, that being Debutante Detective Corps, but that was only because I couldn't snag the DVD and the tape was cheap. Here, for the first time, we have something that never even made it onto recent media, and also the reason I slipped up in the first place: the 1984 film Lensman, which is both well regarded enough to be of interest and condemned to have never reached any technology more modern than a LaserDisc player.

But was it worth it? You'll see when we get there! Let's take a look at Night on the Galactic Railroad, Golgo 13: The Professional, Lensman, and Lupin the Third: The Legend of the Gold of Babylon...

Night on the Galactic Railroad, 1985, dir: Gisaburo Sugii

Beloved childhood classics don't always translate readily between cultures, nor should we expect them to. After all, these are the sort of stories that get buried deep in a nation's psyche, often in ways that are difficult to comprehend from the outside. And that certainly seems to be true for the works of Kenji Miyazawa, who somehow managed to tell enormously personal, abstract, difficult tales that probed at his brief and often tormented life in a manner that resonated deeply with those who came after him.

Thus, from half a century after his death, we have the film adaptation of his short and oft rewritten but never quite finished novel Night on the Galactic Railroad, which sort of looks like a kids film and sort of behaves like a kids film and yet has no qualms about delving into questions of faith, suffering, and how the heck we're meant to live in the sure knowledge that we're all going to die, perhaps without forewarning or apparent cosmic fairness. This is approached via a series of sequential but not always very connected vignettes, and the story of lonely, hard-working boy (well, boy cat) Giovanni, who a quarter of the way into the film finds himself whisked from his home town by an interstellar train, where he runs into his friend Campanella. From there, the two encounter various other characters, many of whom have stories of their own to tell, and go on a series of...

I was going to say adventures, but that's not really how Night on the Galactic Railroad works. If it was a Western kids' story then sure, we might reasonably expect that. If it were, to pick on a close parallel, something like the sort of children's literature C. S. Lewis wrote, another author trying to thrash out questions of faith and the meaning of existence through the medium of books ostensibly aimed at a young audience, we'd expect the two friends to be a driving force through the narrative, even if that narrative was primarily there to explore bigger issues. But actually, the pair are more of an audience, and very little happens to them in the traditional sense; indeed, the one episode where they're particularly active was invented by screenwriter Minoru Betsuyaku. Mostly we're in classic dream narrative territory: stuff happens, much of it makes no objective sense, but Giovanni and Campanella are content to go with the flow, no matter how odd these events seem to us, the wide-awake audience.

The way Night on the Galactic Railroad pulls this off is partly by successfully conjuring the precise mood of a dream and partly by embedding us in a story that rejects adult baggage and views the world through childish eyes, making intuitive much that would otherwise be strange. And all of this depends primarily on a couple of elements. First and foremost, unsurprisingly, there's the animation, which is soft and simple and quite lovely, and looks like a children's book come to life in the truest sense: not like a series of illustrations but as if we've plunged through those illustrations into the world within. But good as the animation is, I doubt it would work without Haruomi Hosono's sublime score, which ties every element - the dreaminess, the childishness, the religiosity, the grand philosophising - together with alternating subtlety and grandeur. Though thinking about it, even Hosono wouldn't be so effective were it not for some tremendous sound engineering: for example, its impossible to imagine this succeeding half so well without the measured, eerie clacking of wheels and gears that underlies the train journey.

Sadly, none of that's to say that I loved Night on the Galactic Railroad; I think it would be a tough film to truly love, though I'm sure there are many who do. In some ways, it deals in universal themes, and in some ways it does so wonderfully, but it also has a tendency to phrase them in terms of religious faith, which, if you're not religious, can be off-putting. Also, there's the fact that - at the risk of sounding like a philistine! - not a heck of a lot happens and much of what does happen is fairly baffling. This is the kind of film you have to give yourself over to wholly, and if you can't succumb to its hallucinatory atmosphere and keep succumbing, it loses a lot of its effect. But to be clear, you should absolutely put in the effort: I can't say on the back of a single viewing whether Night on the Galactic Railroad is a masterpiece, but it certainly begs the possibility.

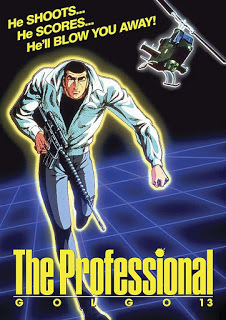

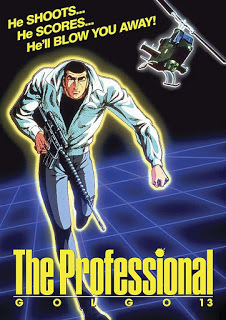

Golgo 13: The Professional, 1983, dir: Osamu Dezaki

Golgo 13: The Professional, 1983, dir: Osamu DezakiThere's a lot about Golgo 13: The Professional that's plain awful. Top of the list has to be Golgo 13 himself, a hitman so stoic that, whatever the male equivalent of the sexy lamp test is, he'd fail it. In many a scene, you could replace him with, say, a brick or a fence post, and it would have negligible impact on the drama. In fact, some sequences would make more sense, since there are moments when logic dictates that a flesh-and-blood human being would die horribly, rather than appearing intact a minute later as though a building hadn't just exploded around them. And Golgo 13 the character is at his worst when Golgo 13 the film expects us to believe that he's irresistible to women, which is often. In this universe, apparently nothing excites the ladies more than a total lack of personality, and the way to drive them to heights of ecstasy is to lie perfectly immobile and let them get on with whatever they feel like doing. Mind you, this should probably more be regarded as part of a wider issue with the movie's horrible attitudes, which manifests most damningly in a rape scene - heck, more of a rape subplot - that exists primarily so that we grasp that the villains are such unpleasant people that we should be on Golgo 13's side, ignoring the extent to which he does nothing besides kill people for money and have inanimate sex.

Now, I'm inclined to argue that Osamu Dezaki salvages Golgo 13: The Professional, but I honestly don't know if that's the case: I can't be certain his bonkers approach here makes for a better film. What he certainly does do, though, is offer one hell of a distraction. I've commented often on how Dezaki was a fan of ostentatious style to an extent few directors can, or would want to, match, but now I reckon I hadn't seen the half of it. Golgo 13 feels like the work of a man who was handed the script for a seedy hitman thriller and decided his brief was to make a delirious art installation. I doubt there's a shot anywhere that could be described as normal; always there's some weird trick or angle or distortion. And there's never a point where it feels like Dezaki is content with merely propelling the narrative from A to B. There are plenty of scenes that don't work at the level of plot - most of the first third falls hard into that category - and there are plenty of scenes that don't work at the level of visual storytelling, but there's not an instant where it doesn't seem that Dezaki was wholly invested in whatever he was up to.

Then again, like I say, whether what he regarded himself to be doing had much in common with conveying a coherent version of the screenplay handed to him is an unanswerable question. Still, I'm inclined to take his side, given how not terribly special that screenplay is. It has superior moments, like an unlikely hit that takes up the middle portion and a basically sound reason for all the various goings-on that ends on a satisfying twist, but there's also lots of garbage, mostly stemming from the scumminess with which it handles its every female character. Those aren't small failings, nor are they easy to look past; a couple of years back, in the days when I loathed Dezaki for his reliance on weird gimmickry, I doubt I'd have managed it. And while the animation is respectable and sometimes great, even that's not always an asset. In particular, some desperately primitive CG is fine in the weird Bond-style credits sequence but ruinous when it shows up later for a helicopter attack on a building.

All told, I couldn't honestly claim Golgo 13: The Professional is a good film. It gets too much enormously, inexcusably, unnecessarily wrong for that to be the case, and even that weren't true, it would still be a story about a profoundly boring central character. But in Dezaki's hands, subjected to his overdose of raw style, it's certainly something. And now that I'm on side with Dezaki, I personally enjoyed it far more than I didn't, even if the content often made that more challenging than it needed to be. As eighties anime classics go, it's aged atrociously, and there's plenty better out there. But if its director's mad excesses are now the sole reason to seek this out, they're nonetheless a decent excuse.

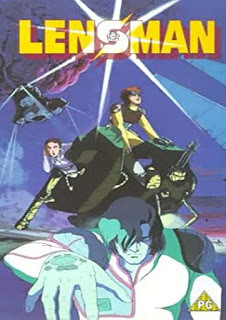

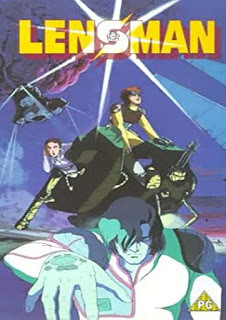

Lensman, 1984, dir: Shûichi Hirokawa, Yoshiaki Kawajiri

Lensman, 1984, dir: Shûichi Hirokawa, Yoshiaki KawajiriYou can absolutely see the thinking behind Lensman. By 1984, Star Wars continued to be enormous business, as was trying to imitate it with whatever pulpy sci-fi you could conjure up, and what pulpier sci-fi was there than the writings of E. E. "Doc" Smith? Add to that the fact that A New Hope has some transparent similarities to the books and you had the perfect balance: all the benefits of imitating Star Wars and with the neat get-out of pointing out that actually, no, you were the rip-off merchant, Mr. Lucas, all we're doing is adapting these here novels.

Whether or not that was truly the logic behind their decision-making, what's evident is that Toho were willing to throw some serious money at the thing. It's all there on the screen, and if it wasn't, the presence of some remarkably okay CG effects in 1984 - yeah, eleven years before Toy Story, that 1984 - are a sure testament. All of which begs the question of why you've probably never heard of the movie Lensman and almost certainly never seen a copy.

The answer to that question isn't altogether easy. Or rather, it's very easy indeed - as I mentioned in the introduction, the film never made it to any medium besides VHS and LaserDisc - but the whys and wherefores are trickier. The most convincing theory I've found is that Smith's estate, unimpressed with the liberties taken with the beloved material and possibly also a lack of appropriate royalties, created enough of a fuss that nobody was willing to wade into the legal quagmire to try and salvage the release rights. And that certainly seems plausible, given how much vastly worse eighties anime would find its way onto DVD.

Because, whether we choose to view it as a shonky E. E. Smith adaptation or an unusually solid Star Wars rip-off, Lensman is quite the treat. Its plot is absolutely boilerplate, but boilerplate dressed up with lots of delightful stuff around the edges, as our young hero Kimball Kinnison finds himself orphaned and dragged into an intergalactic war with only a bison man, some sort of pterodactyl person, and a sexy nurse lady to back him up. Oh, and the titular lens, a bit of nifty technology that serves so little point in the plot that they could have exchanged it with any easily carried technomagical doodad and saved themselves a lot of bother. At any rate, the film has a merry time barrelling through various loosely connected incidents for the better part of two hours, from spaceship scraps to drugged-up alien murder slug attacks to disco riots, and looks terrific all the while: the character work has dated slightly badly, and is oddly careless in places, and obviously 1984 CG can't hold a candle to modern CG - though it's awfully charming in its own way - but the backgrounds and effects and the vast bulk of the animation are up there with anything the decade would provide.

Admittedly, Lensman is hardly perfect, and I wouldn't go so far as claiming it to be any kind of lost classic. Appropriately for a Star Wars imitator, its signal weakness is a flat lead character, and Kimball also gets the least inspired design, along with, in the dub Manga put out, the worst vocal performance in an otherwise impressive cast. Then there's the female lead, Clarissa MacDougall, who's introduced as a plucky Katherine Hepburn type before immediately descending into serial damsel-in-distress uselessness; and the back half does rather get lost in enormous action sequences that, while undeniably cool, are less fun than the more involved world-building of the opening scenes. Nevertheless, there's plenty more that succeeds than doesn't, and taken together, the film is pretty much a joy, certainly enough so that its near-total erasure from anime history has be considered a crying shame.

Lupin the 3rd: The Legend of the Gold of Babylon, 1985, dir's: Seijun Suzuki, Shigetsugu Yoshida

Lupin the 3rd: The Legend of the Gold of Babylon, 1985, dir's: Seijun Suzuki, Shigetsugu YoshidaThe Legend of the Gold of Babylon does something I've never seen anime attempt before, which is to emulate the loose, slipshod style of the brand of American animation exemplified by the works of Ralph "Fritz the Cat" Bakshi. Now, I for one don't like Bakshi's work much at all, and the last thing I want my anime doing is aping it, but hey, it's certainly different. And for a Lupin story that spends a great deal of its running time in New York, it even makes a degree of sense. Indeed, for the first five minutes, a scene in a monster-themed bar that pushes the franchise's tolerance for out-and-out surrealism about as far as it could go, it looks as though it might be precisely the right choice. Then the film stops dead for an extended, repetitive, deeply dull action sequence with perpetually hopeless cop Zenigata, and decides that what it really ought to be foregrounding is how damn dubious the designs for its black characters are, and suddenly the Bakshi influence starts to feel like a very bad decision indeed.

Fortunately, things largely balance out from there; even the experimental animation style eventually settles into something more comfortably familiar, though certain characters, notably Fujiko, never come close to looking right. At any rate, there are scenes that function brilliantly and scenes that fall flat - though none so much so as that interminable motorbike chase with Zenigata - and scenes that simply get the job done, and maybe the lousy beginning even works to the film's benefit, in that everything thereafter seems better than it might otherwise have. Plus, it's to The Legend of the Gold of Babylon's advantage that it has quite a bit of plot to go around, or at any rate lots of incidents that hang together engagingly enough that it feels like there's a significant plot. It's an enormously busy movie, with far more than its share of ideas and characters and threads to keep track of, and that it cobbles all its elements into something that seems vaguely unified is an achievement in itself.

On the flip side, you don't need the excellent liner notes of Eastern Star's re-release to inform you that this had a troubled gestation - though the revelation that one of its many contributors and potential directors was Mamoru Oshii, of Ghost in the Shell fame, and that he was shoved off the project when the studio deemed his ideas too radical and weird, is downright heart-breaking. Then again, their first choice was for Hayao Miyazaki to return and work the sort of magic he brought to The Castle of Cagliostro, so Oshii would admittedly have made for quite the change of pace.

Plus, if his legacy amounted to contributing the screenplay's more outlandish elements, I fervently hope Oshii wasn't to blame for the ending, which doesn't so much jump the shark as line up a hundred sharks and attempt to break the world shark-jumping record. It's so bewildering that it makes the entire film feel oddly non-canonical, since surely there's no squaring any other Lupin film with this one. And while that's an annoying way to have to digest this, the more so given that some of those better scenes get the formula one hundred percent right, it's maybe the best perspective from which to view The Legend of the Gold of Babylon: it feels, and looks, like a Lupin movie beamed in from some bizarre parallel universe. Given how generic and overstuffed the series would become for lengthy stretches, that's exciting in and of itself, but it would be that bit more so if the results were consistently successful.

-oOo-

Do I regret dragging my VHS player out of its retirement in the TV cabinet? Of course I don't! I mean, I should, but that would require a lot more self-judgement and common sense than I possess, so right now I'm just excited about the neat finds I've managed to snag at very reasonable prices ... it turns out pretty much no-one wants VHS tapes, who'd have thought it? We'll certainly be seeing those popping up over the next few posts, so for anyone who comes to this blog for its near-total irrelevancy, that's sure to be a treat!Whether that'll happen next time, though, I'm not certain, because - shock, horror! - I've exhausted my backlog of finished posts and now just have lots of half-finished ones. So really, it's anyone's guess, but it's safe to say this might mark the end of the weekly schedule I've been keeping up for a while now.

[Other reviews in this series: By Date / By Title / By Rating]

Drowning in Nineties Anime, Pt. 87 (80's Anime)

To the long list of things I promised myself I'd never do, because if I did, this whole exercise would go from downright silly to irredeemably ridiculous, then promptly went ahead and did anyway, we can now add picking up titles that were only ever released on VHS. We've had one VHS review already, that being Debutante Detective Corps, but that was only because I couldn't snag the DVD and the tape was cheap. Here, for the first time, we have something that never even made it onto recent media, and also the reason I slipped up in the first place: the 1984 film Lensman, which is both well regarded enough to be of interest and condemned to have never reached any technology more modern than a LaserDisc player.

But was it worth it? You'll see when we get there! Let's take a look at Night on the Galactic Railroad, Golgo 13: The Professional, Lensman, and Lupin the Third: The Legend of the Gold of Babylon...

Night on the Galactic Railroad, 1985, dir: Gisaburo Sugii

Beloved childhood classics don't always translate readily between cultures, nor should we expect them to. After all, these are the sort of stories that get buried deep in a nation's psyche, often in ways that are difficult to comprehend from the outside. And that certainly seems to be true for the works of Kenji Miyazawa, who somehow managed to tell enormously personal, abstract, difficult tales that probed at his brief and often tormented life in a manner that resonated deeply with those who came after him.

Thus, from half a century after his death, we have the film adaptation of his short and oft rewritten but never quite finished novel Night on the Galactic Railroad, which sort of looks like a kids film and sort of behaves like a kids film and yet has no qualms about delving into questions of faith, suffering, and how the heck we're meant to live in the sure knowledge that we're all going to die, perhaps without forewarning or apparent cosmic fairness. This is approached via a series of sequential but not always very connected vignettes, and the story of lonely, hard-working boy (well, boy cat) Giovanni, who a quarter of the way into the film finds himself whisked from his home town by an interstellar train, where he runs into his friend Campanella. From there, the two encounter various other characters, many of whom have stories of their own to tell, and go on a series of...

I was going to say adventures, but that's not really how Night on the Galactic Railroad works. If it was a Western kids' story then sure, we might reasonably expect that. If it were, to pick on a close parallel, something like the sort of children's literature C. S. Lewis wrote, another author trying to thrash out questions of faith and the meaning of existence through the medium of books ostensibly aimed at a young audience, we'd expect the two friends to be a driving force through the narrative, even if that narrative was primarily there to explore bigger issues. But actually, the pair are more of an audience, and very little happens to them in the traditional sense; indeed, the one episode where they're particularly active was invented by screenwriter Minoru Betsuyaku. Mostly we're in classic dream narrative territory: stuff happens, much of it makes no objective sense, but Giovanni and Campanella are content to go with the flow, no matter how odd these events seem to us, the wide-awake audience.

The way Night on the Galactic Railroad pulls this off is partly by successfully conjuring the precise mood of a dream and partly by embedding us in a story that rejects adult baggage and views the world through childish eyes, making intuitive much that would otherwise be strange. And all of this depends primarily on a couple of elements. First and foremost, unsurprisingly, there's the animation, which is soft and simple and quite lovely, and looks like a children's book come to life in the truest sense: not like a series of illustrations but as if we've plunged through those illustrations into the world within. But good as the animation is, I doubt it would work without Haruomi Hosono's sublime score, which ties every element - the dreaminess, the childishness, the religiosity, the grand philosophising - together with alternating subtlety and grandeur. Though thinking about it, even Hosono wouldn't be so effective were it not for some tremendous sound engineering: for example, its impossible to imagine this succeeding half so well without the measured, eerie clacking of wheels and gears that underlies the train journey.

Sadly, none of that's to say that I loved Night on the Galactic Railroad; I think it would be a tough film to truly love, though I'm sure there are many who do. In some ways, it deals in universal themes, and in some ways it does so wonderfully, but it also has a tendency to phrase them in terms of religious faith, which, if you're not religious, can be off-putting. Also, there's the fact that - at the risk of sounding like a philistine! - not a heck of a lot happens and much of what does happen is fairly baffling. This is the kind of film you have to give yourself over to wholly, and if you can't succumb to its hallucinatory atmosphere and keep succumbing, it loses a lot of its effect. But to be clear, you should absolutely put in the effort: I can't say on the back of a single viewing whether Night on the Galactic Railroad is a masterpiece, but it certainly begs the possibility.

Golgo 13: The Professional, 1983, dir: Osamu Dezaki

Golgo 13: The Professional, 1983, dir: Osamu DezakiThere's a lot about Golgo 13: The Professional that's plain awful. Top of the list has to be Golgo 13 himself, a hitman so stoic that, whatever the male equivalent of the sexy lamp test is, he'd fail it. In many a scene, you could replace him with, say, a brick or a fence post, and it would have negligible impact on the drama. In fact, some sequences would make more sense, since there are moments when logic dictates that a flesh-and-blood human being would die horribly, rather than appearing intact a minute later as though a building hadn't just exploded around them. And Golgo 13 the character is at his worst when Golgo 13 the film expects us to believe that he's irresistible to women, which is often. In this universe, apparently nothing excites the ladies more than a total lack of personality, and the way to drive them to heights of ecstasy is to lie perfectly immobile and let them get on with whatever they feel like doing. Mind you, this should probably more be regarded as part of a wider issue with the movie's horrible attitudes, which manifests most damningly in a rape scene - heck, more of a rape subplot - that exists primarily so that we grasp that the villains are such unpleasant people that we should be on Golgo 13's side, ignoring the extent to which he does nothing besides kill people for money and have inanimate sex.

Now, I'm inclined to argue that Osamu Dezaki salvages Golgo 13: The Professional, but I honestly don't know if that's the case: I can't be certain his bonkers approach here makes for a better film. What he certainly does do, though, is offer one hell of a distraction. I've commented often on how Dezaki was a fan of ostentatious style to an extent few directors can, or would want to, match, but now I reckon I hadn't seen the half of it. Golgo 13 feels like the work of a man who was handed the script for a seedy hitman thriller and decided his brief was to make a delirious art installation. I doubt there's a shot anywhere that could be described as normal; always there's some weird trick or angle or distortion. And there's never a point where it feels like Dezaki is content with merely propelling the narrative from A to B. There are plenty of scenes that don't work at the level of plot - most of the first third falls hard into that category - and there are plenty of scenes that don't work at the level of visual storytelling, but there's not an instant where it doesn't seem that Dezaki was wholly invested in whatever he was up to.

Then again, like I say, whether what he regarded himself to be doing had much in common with conveying a coherent version of the screenplay handed to him is an unanswerable question. Still, I'm inclined to take his side, given how not terribly special that screenplay is. It has superior moments, like an unlikely hit that takes up the middle portion and a basically sound reason for all the various goings-on that ends on a satisfying twist, but there's also lots of garbage, mostly stemming from the scumminess with which it handles its every female character. Those aren't small failings, nor are they easy to look past; a couple of years back, in the days when I loathed Dezaki for his reliance on weird gimmickry, I doubt I'd have managed it. And while the animation is respectable and sometimes great, even that's not always an asset. In particular, some desperately primitive CG is fine in the weird Bond-style credits sequence but ruinous when it shows up later for a helicopter attack on a building.

All told, I couldn't honestly claim Golgo 13: The Professional is a good film. It gets too much enormously, inexcusably, unnecessarily wrong for that to be the case, and even that weren't true, it would still be a story about a profoundly boring central character. But in Dezaki's hands, subjected to his overdose of raw style, it's certainly something. And now that I'm on side with Dezaki, I personally enjoyed it far more than I didn't, even if the content often made that more challenging than it needed to be. As eighties anime classics go, it's aged atrociously, and there's plenty better out there. But if its director's mad excesses are now the sole reason to seek this out, they're nonetheless a decent excuse.

Lensman, 1984, dir: Shûichi Hirokawa, Yoshiaki Kawajiri

Lensman, 1984, dir: Shûichi Hirokawa, Yoshiaki KawajiriYou can absolutely see the thinking behind Lensman. By 1984, Star Wars continued to be enormous business, as was trying to imitate it with whatever pulpy sci-fi you could conjure up, and what pulpier sci-fi was there than the writings of E. E. "Doc" Smith? Add to that the fact that A New Hope has some transparent similarities to the books and you had the perfect balance: all the benefits of imitating Star Wars and with the neat get-out of pointing out that actually, no, you were the rip-off merchant, Mr. Lucas, all we're doing is adapting these here novels.

Whether or not that was truly the logic behind their decision-making, what's evident is that Toho were willing to throw some serious money at the thing. It's all there on the screen, and if it wasn't, the presence of some remarkably okay CG effects in 1984 - yeah, eleven years before Toy Story, that 1984 - are a sure testament. All of which begs the question of why you've probably never heard of the movie Lensman and almost certainly never seen a copy.

The answer to that question isn't altogether easy. Or rather, it's very easy indeed - as I mentioned in the introduction, the film never made it to any medium besides VHS and LaserDisc - but the whys and wherefores are trickier. The most convincing theory I've found is that Smith's estate, unimpressed with the liberties taken with the beloved material and possibly also a lack of appropriate royalties, created enough of a fuss that nobody was willing to wade into the legal quagmire to try and salvage the release rights. And that certainly seems plausible, given how much vastly worse eighties anime would find its way onto DVD.

Because, whether we choose to view it as a shonky E. E. Smith adaptation or an unusually solid Star Wars rip-off, Lensman is quite the treat. Its plot is absolutely boilerplate, but boilerplate dressed up with lots of delightful stuff around the edges, as our young hero Kimball Kinnison finds himself orphaned and dragged into an intergalactic war with only a bison man, some sort of pterodactyl person, and a sexy nurse lady to back him up. Oh, and the titular lens, a bit of nifty technology that serves so little point in the plot that they could have exchanged it with any easily carried technomagical doodad and saved themselves a lot of bother. At any rate, the film has a merry time barrelling through various loosely connected incidents for the better part of two hours, from spaceship scraps to drugged-up alien murder slug attacks to disco riots, and looks terrific all the while: the character work has dated slightly badly, and is oddly careless in places, and obviously 1984 CG can't hold a candle to modern CG - though it's awfully charming in its own way - but the backgrounds and effects and the vast bulk of the animation are up there with anything the decade would provide.

Admittedly, Lensman is hardly perfect, and I wouldn't go so far as claiming it to be any kind of lost classic. Appropriately for a Star Wars imitator, its signal weakness is a flat lead character, and Kimball also gets the least inspired design, along with, in the dub Manga put out, the worst vocal performance in an otherwise impressive cast. Then there's the female lead, Clarissa MacDougall, who's introduced as a plucky Katherine Hepburn type before immediately descending into serial damsel-in-distress uselessness; and the back half does rather get lost in enormous action sequences that, while undeniably cool, are less fun than the more involved world-building of the opening scenes. Nevertheless, there's plenty more that succeeds than doesn't, and taken together, the film is pretty much a joy, certainly enough so that its near-total erasure from anime history has be considered a crying shame.

Lupin the 3rd: The Legend of the Gold of Babylon, 1985, dir's: Seijun Suzuki, Shigetsugu Yoshida

Lupin the 3rd: The Legend of the Gold of Babylon, 1985, dir's: Seijun Suzuki, Shigetsugu YoshidaThe Legend of the Gold of Babylon does something I've never seen anime attempt before, which is to emulate the loose, slipshod style of the brand of American animation exemplified by the works of Ralph "Fritz the Cat" Bakshi. Now, I for one don't like Bakshi's work much at all, and the last thing I want my anime doing is aping it, but hey, it's certainly different. And for a Lupin story that spends a great deal of its running time in New York, it even makes a degree of sense. Indeed, for the first five minutes, a scene in a monster-themed bar that pushes the franchise's tolerance for out-and-out surrealism about as far as it could go, it looks as though it might be precisely the right choice. Then the film stops dead for an extended, repetitive, deeply dull action sequence with perpetually hopeless cop Zenigata, and decides that what it really ought to be foregrounding is how damn dubious the designs for its black characters are, and suddenly the Bakshi influence starts to feel like a very bad decision indeed.

Fortunately, things largely balance out from there; even the experimental animation style eventually settles into something more comfortably familiar, though certain characters, notably Fujiko, never come close to looking right. At any rate, there are scenes that function brilliantly and scenes that fall flat - though none so much so as that interminable motorbike chase with Zenigata - and scenes that simply get the job done, and maybe the lousy beginning even works to the film's benefit, in that everything thereafter seems better than it might otherwise have. Plus, it's to The Legend of the Gold of Babylon's advantage that it has quite a bit of plot to go around, or at any rate lots of incidents that hang together engagingly enough that it feels like there's a significant plot. It's an enormously busy movie, with far more than its share of ideas and characters and threads to keep track of, and that it cobbles all its elements into something that seems vaguely unified is an achievement in itself.

On the flip side, you don't need the excellent liner notes of Eastern Star's re-release to inform you that this had a troubled gestation - though the revelation that one of its many contributors and potential directors was Mamoru Oshii, of Ghost in the Shell fame, and that he was shoved off the project when the studio deemed his ideas too radical and weird, is downright heart-breaking. Then again, their first choice was for Hayao Miyazaki to return and work the sort of magic he brought to The Castle of Cagliostro, so Oshii would admittedly have made for quite the change of pace.

Plus, if his legacy amounted to contributing the screenplay's more outlandish elements, I fervently hope Oshii wasn't to blame for the ending, which doesn't so much jump the shark as line up a hundred sharks and attempt to break the world shark-jumping record. It's so bewildering that it makes the entire film feel oddly non-canonical, since surely there's no squaring any other Lupin film with this one. And while that's an annoying way to have to digest this, the more so given that some of those better scenes get the formula one hundred percent right, it's maybe the best perspective from which to view The Legend of the Gold of Babylon: it feels, and looks, like a Lupin movie beamed in from some bizarre parallel universe. Given how generic and overstuffed the series would become for lengthy stretches, that's exciting in and of itself, but it would be that bit more so if the results were consistently successful.

-oOo-

Do I regret dragging my VHS player out of its retirement in the TV cabinet? Of course I don't! I mean, I should, but that would require a lot more self-judgement and common sense than I possess, so right now I'm just excited about the neat finds I've managed to snag at very reasonable prices ... it turns out pretty much no-one wants VHS tapes, who'd have thought it? We'll certainly be seeing those popping up over the next few posts, so for anyone who comes to this blog for its near-total irrelevancy, that's sure to be a treat!Whether that'll happen next time, though, I'm not certain, because - shock, horror! - I've exhausted my backlog of finished posts and now just have lots of half-finished ones. So really, it's anyone's guess, but it's safe to say this might mark the end of the weekly schedule I've been keeping up for a while now.

[Other reviews in this series: By Date / By Title / By Rating]

November 10, 2020

Drowning in Nineties Anime, Pt. 86

Let's talk about sex, shall we? Or, well, not talk about it, more review some anime about it, but ... wait, what do you mean I already did a sex-themed review post way back in part 43? That's ... woah, exactly 43 posts ago, isn't it? That's kind of creepy. And also means that henceforward, every 43rd post is going to have to be sex-related.

Boy, that went south fast, huh? I guess we probably ought to just look at some sexy anime, in the shape of Demon Fighter Kocho, Very Private Lesson, Fake, and the Sorcerer Hunters OVA...

Demon Fighter Kocho, 1997, dir: Tôru Yoshida

Demon Fighter Kocho, 1997, dir: Tôru YoshidaWhat's a fair way to go about reviewing an OVA of less than half an hour in length? It's tempting to say that Demon Fighter Kocho would have been a solid title if there was only more of it, but that doesn't get us far, because what we have is all there is or ever will be. And to its credit, it crams about as much into its running time as you could possibly ask for, setting up its concept and introducing four characters sufficiently that we have a sense of who they are and what they're about and even finding time to tell a decent little story, with a beginning, middle, and twisty end. Moreover, it's not as if that story would be improved by being twice as long; it's actually rather satisfying the way Demon Fighter Kocho barrels through its plot without pausing for breath. It's just that it's tough to come away from what amounts to a single TV episode and feel you've had your money's worth.

Still, let's take that as said and move on, shall we? What we have here belongs to a familiar subgenre, both in and out of anime: Kocho is a high school student who, as the title informs us, fights demons, as part of her role in an astrology class that clearly should have been shut down years ago, what with how the teacher, Professor Kamo, is a massive sex pest with no qualms about tricking his female students into disrobing. Also, thinking about it, as far as this OVA is concerned, Kocho doesn't fight demons, she fights ghosts; and this she does with the dubious assistance of her sister Koran, along with fellow student Kosaku, who's also a bit of a perv. Kocho seemingly lacks any powers, but what she's pretty great at is getting naked, and Kamo and Kosaku are both entirely fine with this, especially given that Koran's also quite willing to reveal all at the drop of a hat.

So you could consider it a much more perverted Buffy the Vampire Slayer, or a slightly more perverted Devil Hunter Yohko, but either way, it's evident the territory we're in and Demon Fighter Kocho does nothing to hide its influences. Insomuch as it's interested in doing its own thing, that mostly extends to doubling down on the nudity and the general obsession with sex, along with a bit of self-aware fourth wall breaking that's perhaps its biggest saving grace; it's genuinely funny in places, and even when it's not, it has an endearing tone of not taking itself too seriously. Being able to laugh along with Demon Fighter Kocho does it a lot of favours, because it's never quite good enough that it would get by otherwise. The animation is resolutely mediocre, with dated computer assists and character designs that look almost half-finished, and only the jaunty score stands out on the artistic side of things.

To finish on a slight diversion, while putting out a less-than-thirty-minute OVA that just barely warrants the effort is very much the kind of thing AnimeWorks had a bad habit of doing, a dash of credit's due for the extras, which are the usual behind the scenes stuff with the US voice cast that tend to pad out these releases, but much longer and much less filtered. Though I didn't check, I suspect the various bits of footage we get total more than Demon Fighter Kocho itself, and they're an entertaining insight, the more so because the dub cast are actually pretty good and pretty damn funny in their own right. Obviously those extras don't push the title into must-have territory or anything, but they round out the package nicely, and meant that I came away from Demon Fighter Kocho with a somewhat greater appreciation of its goofy, low-rent charms.

Very Private Lesson, 1998, dir: Hideaki Ôba

Very Private Lesson, 1998, dir: Hideaki ÔbaIt's tough to imagine how the setup for Very Private Lesson was ever going to work: youthful teacher Oraku, in the midst of trying to hit on his crush and fellow teacher Satsuki, runs into the sixteen-year-old Aya, who proceeds to have him drive her home and flirts with him mercilessly. By the next day, Aya has somehow tracked down his address, and not only has she transferred to the class Oraku teaches, she's decided to move in with him, and Oraku hasn't much choice in the matter because her old man happens to be a Yakusa boss who, as the saying goes, makes him an offer he can't refuse: either get Aya to graduation in one piece or suffer the consequences.

Accepting that there's probably no good way to go about that wholly problematic setup, it's at least not hard to see a less disastrous approach than the one the makers opted for. What we get is effectively three different takes, which the show bounces between largely at random: the smutty comedy that's the most obvious route, a more sweet-natured character drama that emphasises Oraku and Aya's developing friendship and mutual respect, and - here's the kicker - a violent, social-realist thriller in which Aya is repeatedly under threat of rape and Oraku under threat of horrible violence or even death.

Two of those could, maybe, have fitted together; certainly you could have got a fairly routine nineties anime sex comedy out of the first two in combination, and if it kept a tight rein on the fan service, it might even have been pretty okay. And for that matter, the thriller stuff, though grim and tasteless, is far from unsalvageable; it's novel, at least, to see an anime of this sort that doesn't shy away from the darker aspects of school life and Japanese society. But all three together makes for a tone that's often wildly, cringingly dysfunctional. The show absolutely wants to have its cake and eat it, while never seeming entirely sure what the cake actually consists of: one minute it's leching over Aya in her underwear, the next it's freaking out over the prospect of her falling into the hands of one of the many male characters who openly express an interest in sexually assaulting her. It shouldn't need saying that that's not a topic you treat lightly, and it's sure as hell not one you cram up against sleazy light comedy.

Really, the only reason I'm wasting this many words on something that's in many ways totally obnoxious is that it isn't wholly awful. Technically it's pretty competent - the music's particularly solid, but the animation does just fine - and narratively it's not always a train wreck. Oraku and Aya are both humanised enough that we like them and would like to see them helping each other out, and Aya in particularly strays far enough away from the twin poles of obnoxious male fantasy and obnoxious male nightmare that it feels like there's a personality there that could be more deeply delved into. The comedy is even funny sometimes, and the thriller aspects are interesting, particularly in how they're willing to explore their ostensible villains and reveal them as more complex than we'd assume. But seesawing between the two constantly over the course of an OVA that doesn't make it to ninety minutes is a hell of an ask of an audience, and one Very Private Lesson ultimately doesn't warrant.

Fake, 1996, dir: Iku Suzuki

Fake, 1996, dir: Iku SuzukiIt's fair to say that the anime market has never exactly been overstuffed with shows about gay American cops holidaying in the British countryside, so if there's one thing Fake has going for it, it's novelty. Though, unlike in the West, it's not the gay part of that equation that really stands out; most anime fans will have at some point encountered the subgenre known as Yaoi, of homoerotic stories aimed at a primarily female audience. Supplant that to the wilds of England, though, and the result is something decidedly interesting. It's not really a criticism to say that anime tends to get the UK enormously wrong - I mean, it's not as if Western media hasn't been horribly misrepresenting Japan forever - but it genuinely feels like a bit of research went into Fake, and possibly even an actual visit. I mean, Peter Rabbit shows up at one point, how's that for veracity! Granted, so does a tanuki, and you don't see a lot of those gambolling around in English forests, but nobody's perfect.

In fairness, that care for detail is mostly true of the Yaoi aspects as well: you can sort of tell that this was aimed more at women than at gay men, but there's enough depth and complexity to the lead characters that the presentation of their relationship feels more sympathetic than prurient. This is a good thing given how basically seedy the premise is: the confident and openly gay Dee Laytner has arranged this trip away with the explicit goal of bedding his more closeted partner (in the police sense!) Ryō 'Randy' Maclean, and he's certainly not above getting him drunk to do it. Thankfully, Dee isn't quite as lecherous as the setup paints him to be, and where many a nineties anime character would have barged onward without restraint, he's generally inclined to rein himself in before anything happens to push the certificate up. This lets Fake have it both ways, by being a raunchy sex comedy that nevertheless doesn't slip up as a character drama and lets us laugh comfortably at situations which could easily have gone the other way, especially given that we're never a hundred percent sure of where Ryō's proclivities tend.

So that's the first half of Fake: Dee hits on Ryō, Ryō demurs, while also playing up to it sufficiently that we can get a few scenes of two guys making out, and it's all pretty involving, mostly because the pace is relaxed enough that we feel we're hanging out with this pair of likeable characters who we'd be quite happy to see wind up together. But there's a B-plot bubbling away, introduced by a brief flash of bloody murder early on, and inevitably the B-plot has to become the A-plot before all's said and done. This isn't disastrous, since it's not like the stuff that was working just vanishes, but the murder mystery that dominates the latter half is hardly an asset: it's obvious who the culprit is, since there aren't any other suspects, their motives are nonsensical, and it's utterly implausible that the local police wouldn't have figured out whodunit. There's some hand-waving about a cover-up perpetrated by the locals, which is downplayed enough that its stupidity isn't too glaring, but in general, all the shift into more traditional cop drama gets us is a relatively fun action sequence to cap things off with. Oh, and the sight of Peter Rabbit being stabbed, which after those godawful recent movies is enough to earn an extra point.

Put the two halves together and you end up with something that's definitely unusual - "come for the gay romance, stay for the naff murder mystery!" is a tagline no-one used ever - but generally more successful than not. Ryō and Dee are engaging company, as are most of the supporting cast, technically it's all more good that not, there are some solid laughs, and the thriller elements kick in just as we've had about enough of our two heroes awkwardly flirting. If those thriller elements had been great, Fake would be an easy recommendation; given that they're only just about functional, it ends up much more in the category of "Take a look if it sounds like your thing." Still, all credit to AnimeWorks for putting this out there, it's always a treat to come across a title that doesn't feel quite like anything else.

Sorcerer Hunters OVA, 1996, dir: Kōichi Mashimo

Sorcerer Hunters OVA, 1996, dir: Kōichi MashimoI'll say this for the Sorcerer Hunters OVA, it's nice to see an anime that commits so hard to being a sex comedy, instead of tentatively nosing around the concept. So often anime has a tendency to be simultaneously prudish and exploitative, portraying sex as something basically naughty that men want to do to women - and that needs to be punished, perhaps via giant hammers or lightning attacks - and never going beyond the odd illicit flash of bare breasts or underpants, there to "service" the (implicitly male) fans and often so unrelated to what's going on elsewhere that the plot has to come to a crashing halt to fit the moment in.

Sorcerer Hunters is having none of that. We've seen practically the entire cast naked by the end of the second scene, and the remainder of the first of these three episodes involves them all trying fiercely to hook up in various combinations. It's that rare work that concedes that sex is basically a fun activity, one most people want to do, and even goes so far as to admit that sometimes women want to have sex with women and men want to have sex with men and some folks aren't especially picky and all of this is absolutely fine. Once you get past the sheer busy lecherousness, it's actually kind of refreshing. Sure, it's not particularly adult - the general theme here is still using sex as a way into a familiar brand of silly comedy, and there's no question that the targeted viewer remains predominantly male - but it's at least flirting with the notion of adultness.

Would that it could have found a way to do this and be a mite funnier! Don't get me wrong, the Sorcerer Hunters OVA often is quite funny, and I certainly laughed out loud at various occasions over the course of its ninety minute running time. But it's not hilarious, or consistent, and even that would be fine if there was a bit more plot to hang the gags and the raunchiness off. Only the middle episode sees any actual sorcerer hunting going on, or has what you could generously call a story, and thinking about it, that probably makes it the weakest of the three; then again, it's not much of a story, so I'm not sure that disproves my argument. The problem's not ruinous, but compare this with another Sorcerer Hunters spin-off, the two-part Sorcerer on the Rocks, that actually did manage to deliver a relatively involved narrative without sacrificing the humour, and it feels that bit shallower than even its inherently shallow nature calls for.

On the plus side, if we're making that comparison, Sorcerer Hunters does considerably better on the technical side of things, with animation that's in line with what you'd hope for from a mid-nineties OVA of a TV show: there's enough extra spark here to warrant the step up of an independent release, and Mashimo's energetic direction ensures that the plotlessness and inconsistent humour don't matter too much while you're watching, since there's rarely a slow moment in which to nitpick. Even with all that, I doubt it's going to stick in my memory, but if you fancy a fantasy comedy anime that's not terribly interested in the fantasy side of things but is absolutely obsessed with sex, this might well be for you.

-oOo-

Sex may allegedly sell, but you certainly get the sense from this bunch that it doesn't often make for good anime. I suppose that only Very Private Lesson was actively bad, though it was bad enough in its worst moments to cast quite the shadow over everything else, and it's not as though anything was good enough to make up for it. Fake seems to be well-regarded, and I can certainly see why, but the thriller parts were enormously dumb and could have been fixed with annoying ease. Looking back, I'm almost wondering whether my personal highlight wasn't Demon Fighter Kocho, and that certainly wasn't a sentence I ever dreamed I'd type when I was watching it. Oh, and as for the Sorcerer Hunters OVA, while it wasn't anything terribly special, it does have the advantage of having been recently re-released along with the series, so at least you can buy the thing for money without too much bother, which makes quite the change for these reviews!

Next: probably another trip back to the eighties, unless I change my mind between now and next week...

[Other reviews in this series: By Date / By Title / By Rating]

November 2, 2020

Drowning in Nineties Anime, Pt. 85