Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 736

May 6, 2015

That Big-Ass Name You Gave Me by Mark Anthony Neal

© Maureen Beitle | Bible Study (1999)That Big-Ass Name You Gave Me (for Elsie E. Neal)

© Maureen Beitle | Bible Study (1999)That Big-Ass Name You Gave Me (for Elsie E. Neal)by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

I am still left juxtaposing that image of you at the end--small, fragile, defeated--with the defiant, bombastic yet still tiny figure that I came to know, and would come to know in the stories shared after your demise. Wish I had known that 16-year-old who stepped out of her momma’s home and up to the Big City. I can no more come to terms with those last days than I can imagine my own daughters in such a state, yet that is the cycle.

I was/am mad at you.

I say that now, to get it out of the way, as I was never able to get it out of the way when you were alive, because my inability to say it, even think it, cluttered our relationship, as it clutters my memories of you.

Your granddaughter--the youngest one, the one who who most reminds me of you, the one who is willful and wise beyond her proverbial years--matter-of-factly just asked if I was sad.

I was sad. Not today, or even yesterday, but those other days...you up in a nursing home in the Bronx, me sitting next to you as often as I could, yet unable to reach you. As a child your biggest gift to me was the attention that you gave me. And it’s not that I didn’t have my father’s, your husband’s attention, but you seemed to understand, better than any, the caution that was my nature, that I was more than comfortable in the smallness of it all.

You gave me that big name. Used it as a calling card for the possibilities that I would confront. Many will recall hearing you announce my name before they ever met me. Whatever Mark Anthony Neal is in the world, you imagined that for me, even if you had no idea what that would look like.

The name was always bigger than I wanted to be. Your fear was of not being heard, of not being seen--for real dark-skinned Black girl anxieties, that manifested itself in so many unhealthy ways; the fear of not being taken seriously. If the world was not gonna take you seriously, they were for damn sure gonna take your baby-boy seriously, with that big-ass name that you made him own as a child. In the end I now realize that I never felt invisible or silenced because I knew you always had my back (even when you tore into it).

I was often embarrassed by the Bigness of your personality, not yet aware of all that it masked, until you took that last breath. The smallness of you at the end, betrayed the Bigness that was you. One of your husband’s biggest gifts to me was the example to not be threatened by the Bigness of the woman he chose to share his life with; it has served me well in the home that I share with your two Granddaughters and Daughter-in-Law.

***

You would be proud of both of your granddaughters. Little doubt you’d be put off a bit by the oldest, who is as emotionally detached from family as her father, your son was, for your time on earth. She too is ambitious and focused, and particularly adept at masking the hurts, sleights, the invisibility born of for real dark-skinned Black girl anxieties that she will never publicly claim--because it’s not her way. Oh what I wouldn’t give for her to spend just an hour with the best of you and your momma. True to her spirit, when I spot her on the pool deck, it’s not because she is one of one-hand-full of Black girls on the deck, but because of the white pearls that always adorn her ears and the smile that matches them. We all have our mask.

But that other one--the youngest one, the one who who most reminds me of you, the one who is wise and willful beyond her proverbial years--who just matter-of-factly just asked if I was sad--she is, as one person described her, “Black Girl Magic.” Don’t get me wrong; she is as difficult as you were/are--would have paid some money to watch the two of you go at it. But as one one of her teachers recently admitted, “she is big on justice,” initially borne out her willing acknowledgement--dark-skinned Black Girl anxieties be damned--that she will not be ignored or rendered invisible, but now, more often or not, it is in the advocacy of others. She will be the one who will claim you Big, hence her knowingly pushing me to think hard about you on this morning.

***

As I write this, your city is still smoldering (I know New York--The Bronx--was just the place that you lived and raised me, but Baltimore was always your home). There is a mother who publicly chastised her son, for being up in those rebellious streets; She would not be foreign to you. I offer no judgement regarding her actions, recalling similar moments in my own childhood, like that night you showed up at that football field, belt in hand, looking for a son, who should have already been home.

I Thank-God there were not hand-held devices, though the social media of the day, word-of-mouth, guaranteed that more than a few of my peers would recall that moment, much to my embarrassment. I still walk this earth, in part, because of those actions on your part.

I just wish that you had stayed on the earth long enough for me to finally understand why you made those choices, and to thank-you for them.

I may never live up to that big ass name you gave me; I thank-you for providing the challenge.

Published on May 06, 2015 20:33

Documentary: Adina Howard 20: A Story of Sexual Liberation

In 1995, Adina Howard made waves in the world of music with her hit song “Freak Like Me.” Along with becoming one of the highest selling singles and most played music videos on MTV and BET in 1995. Howard’s performance allowed young women of color and future recording artists to express their sexuality without shame. Adina Howard 20: A Story of Sexual Liberation shares Howards’s story through her own words as well as gives an intellectual view into the inside of the life a platinum of a selling artist via commentary by Professor Treva B. Lindsey and others. ADINA HOWARD 20: A STORY OF SEXUAL LIBERATION (FULL DOCUMENTARY) from Rebel Life Media on Vimeo.

In 1995, Adina Howard made waves in the world of music with her hit song “Freak Like Me.” Along with becoming one of the highest selling singles and most played music videos on MTV and BET in 1995. Howard’s performance allowed young women of color and future recording artists to express their sexuality without shame. Adina Howard 20: A Story of Sexual Liberation shares Howards’s story through her own words as well as gives an intellectual view into the inside of the life a platinum of a selling artist via commentary by Professor Treva B. Lindsey and others. ADINA HOWARD 20: A STORY OF SEXUAL LIBERATION (FULL DOCUMENTARY) from Rebel Life Media on Vimeo.

Published on May 06, 2015 18:06

May 5, 2015

Isaiah Washington's New Film 'Blackbird' Tackles Identity & Homophobia

Published on May 05, 2015 20:48

Director Dee Rees Discusses new Bessie Smith Biopic Starring Queen Latifah

Pariah

director

Dee Rees

talks with HuffPost Live's Nancy Redd about co-writing and directing

Bessie

, a TV biopic starring Queen Latifah as blues legend Bessie Smith.

Pariah

director

Dee Rees

talks with HuffPost Live's Nancy Redd about co-writing and directing

Bessie

, a TV biopic starring Queen Latifah as blues legend Bessie Smith.

Published on May 05, 2015 20:29

Left of Black S5:E29: Black Women's Movements for Black Power

Left of Black S5:E29: Black Women's Movements for Black Power

Left of Black S5:E29: Black Women's Movements for Black Power Left of Black host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) is joined in-studio by Historian Ashley D. Farmer (@DrAshleyFarmer), author of the forthcoming What You've Got is a Revolution: Black Women's Movements for Black Power (UNC Press). Dr. Farmer is a Post- Doctoral Associate in the Department of History at Duke University.Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University and in conjunction with the Center for Arts, Digital Culture & Entrepreneurship (CADCE).*** Episodes of Left of Black are also available for free download in @ iTunes U*** Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlack

Published on May 05, 2015 19:23

Freddie(Gray)’s Dead by I. Augustus Durham

Photo: Andrew BurtonFreddie(Gray)’s Deadby I. Augustus Durham | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Photo: Andrew BurtonFreddie(Gray)’s Deadby I. Augustus Durham | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)The Super Fly soundtrack is a classic for the genre of funk/soul music, and a benchmark for the black cinema score, akin to Isaac Hayes’s Shaft or Aretha Franklin’s Sparkle. Therefore, when perusing his track list, Curtis Mayfield could have chosen any number of songs as Soul Train “fare” for his January 6, 1973 appearance—blue-light special “Give Me Your Love (Love Song)” (my JAM!), funk-laced “Pusherman”, or “Little Child Runnin’ Wild”. Instead, Mayfield performed, understandably, the title track, “Superfly”, and the first single “Freddie’s Dead”, the soundtrack’s most melancholic offering.

Even Wikipedia suggests, “[t]he arrangement is driven by . . . a melancholy string orchestration.” But the most intriguing aspect of the “Freddie’s Dead” performance is that regardless of its accouterments, young, gifted and black folks—natural-haired and crop-topped—dance! Collectively bopping. Rhythmically isolating. They dance to the funeral dirge sitting in the pocket.

Surmising what to say here amidst the occurrences in Baltimore, I kept arriving at Mayfield’s Zodiac twoness (during the Soul Train interview, Jennifer Boykin asks Mayfield’s sign: Gemini!), which could easily be considered prophetic, and the melancholic genius of his episodic B-selection from the vinyl’s A-Side. Having heard the full interview, one presumes that if she theorizes Freddie Gray’s death, then Baltimore becomes the milieu for the Mayfield interview’s intelligibility. Although The Wire never conjures glitter or gold, the Baltimore televised during those five seasons elicits (post)modern double consciousness insofar as perhaps viewers never took seriously that serial life is not but a dream for Freddie, his kith and kin, even on HBO where a high cost is charged to telecast what many deem “low living”.

Nevertheless, the song’s melancholy emerges through lyrical inversion in Erykah Badu’s “Master Teacher”. Mayfield sings, “All I want is some piece of mind/With a little love I’m trying to find/This could be such a beautiful world/ . . .”. Erykah reconfigures Curtis: “I am known to stay awake/A beautiful world I’m trying to find/I’ve been in search of myself/A beautiful world is just too hard for me to find/Said it’s just too hard for me to find/I’m in the search of something new/Searching in me, searching inside you (and that’s for real)/What if there was no niggas only master teachers?/I stay woke”; Curtis echoes “dreams”. If one staged an intervention around niggas (and authenticity) via R. A. T. Judy (1994) to address why Freddie(Gray)’s dead, death by eye contact maps a long history of the “nigga” as “badman”: “nigga is misread as nigger. . . . The nigga of hard core blurs with the gang-banger, mack daddy, new-jack, and drug-dealer, becoming an index of the moral despair engendered by a thoroughly dehumanizing oppression, and hence inevitably bearing a trace of that dehumanization” (Judy 217).

If the exegesis is correct, as “the eye”/I. sees it, Freddie was “asking for it” by daring to even look at “the man”: treatment like a rag doll enfolded upon itself; doubling his back as a do-over of the double bind; boxing him in crateless as Brown, Henry rethought; breaking his neck, but not like Busta, because one’s life is the ultimate cost of his encoding as a “nigga”, even if the aggressor meant nigger. All the while, many never interrogate whether the people who read Freddie as such, vis-à-vis Nas, require decoding themselves.

But is this our newest obstacle, which honestly and melancholically finds its rehearsal again here: have we always and ever misread the victim instead of convening a reading circle about the “victor”? The perpetrators, and others like them, that led to Freddie being dead never conceive of him as a master teacher because they consistently enter bastions of power deeply invested in civilizing “us” through what James Cone calls, via lynching, “public service announcements”, whether one of “us” attends UVA, plays with a toy gun in a nearby park, experiences (black) social life with her peers only to be shot in the head, or, by stunning subterfuge, encounters “the machine” that publicly boycotts any hint of its attachment to fostering “authenticity”, even in the face of a historicized apparatus set up by “dem” to capture “we”—a noose—, by suggesting that such a hateful occasion was “a result of ignorance and bad judgment”, only to proceed in publishing an open letter from the “victor” where his salutation is not even addressed to aggrieved community. It is quite amazing how the powerful protect the very ones who continuously ruin their brand . . .

I digress.

Freddie’s death has awakened in many that they are sick and tired like Fannie Lou, and as much as it was a small minority of the “minority” who broke with the “black protest tradition” and “looted”, according to the always “truthful” media that “keeps them honest”, the perpetrators utilize that same rhetoric to qualify the badmen who do not know how to properly serve and protect, thus creating all things “equal”. Freddie as master teacher gives us the opportunity to listen anew to Curtis and Erykah making musical decisions that signal mastery: for Curtis, the key change; for Erykah, the newness after the count. This is to say, maybe Curtis chooses to perform “Freddie’s Dead” because he comprehends that the black aesthetic tradition, at its best, turns mourning—our collective melancholy—into dancing, trades in sackcloth and ashes as the grave clothes you wore during the work week only to put on joy and gladness when your humanity was affirmed by your brothers and sisters once every seven days, even while tripping the light fantastic.

This twoness is blackness, which is to say humanness. And yet, the sobering conundrum left in the wake of Freddie being dead is: if Freddie is a Baduian master teacher, how many more teachable moments have to be convened on black bodies before our peers in the classroom called society stay woke? Truly everything depends on that awoke-ness because that is indeed the difference between the makings, or breakings, of us all . . . namely you!

+++

I. Augustus Durham is a third-year doctoral candidate in English at Duke University. His work focuses on blackness, melancholy and genius.

Published on May 05, 2015 17:40

#TheRemix: Michael Eric Dyson Talks Malcolm X & Hashtag Activism

On this episode of #TheRemix, host James Braxton Peterson talks with noted public scholar Michael Eric Dyson about the legacy of Malcolm X and #Hashtag Activism.

On this episode of #TheRemix, host James Braxton Peterson talks with noted public scholar Michael Eric Dyson about the legacy of Malcolm X and #Hashtag Activism.

Published on May 05, 2015 14:21

May 4, 2015

A Cornerstone of American Soul: Remembering Ben E. King by Charles L. Hughes

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images A Cornerstone of American Soul: Remembering Ben E. Kingby Charles L. Hughes | @CharlesLHughes2 | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images A Cornerstone of American Soul: Remembering Ben E. Kingby Charles L. Hughes | @CharlesLHughes2 | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)When Ben E. King died last week, the world lost not only one of its great singers. We also said goodbye to a figure who both symbolized and signaled larger historical transformations in the 20th century United States and beyond.

Born in North Carolina, King joined countless other African Americans by relocating to Harlem with his family in 1947. There, he joined several vocal groups including the 5 Crowns, a doo-wop ensemble that performed at the Apollo and elsewhere. In 1958, the Crowns were asked to replace the first line-up of the Drifters, the hit Atlantic Records group whose energetic hits and charismatic lead singer Clyde McPhatter, made them one of the most important acts in the R&B explosion of the 1950s. Embroiled in a conflict with their manager, the McPhatter-led Drifters were fired and replaced by the 5 Crowns, with King installed as the new lead singer.

The King-led Drifters retooled their sound to better spotlight their lead vocalist’s rich, subtle baritone. Working with producer Phil Spector, then at the height of his success with the lush “Wall of Sound,” and skilled songwriters like Jerry Leiber & Mike Stoller or Doc Pomus & Mort Shuman, the King-led Drifters surpassed the commercial success of the original ensemble. For the next several years – both with the Drifters and as a solo artist – Ben E. King was one of the most prominent artists in U.S. popular music.

King’s Atlantic hits were sharp and elegant symphonies that blended a rich musical palette with the singer’s singularly intense vocals. With their sweeping strings and soaring crescendos, records like “This Magic Moment” and “Dance With Me” offered a soundtrack for an age of new opportunity in the wake of the Great Migration, the post-war expansion of the middle class, and the modern Civil Rights Movement.

Additionally, with their Latin flavor, many of King’s recordings – most obviously his first solo hit “Spanish Harlem” – revealed the continuing interchange between black and Latin communities in New York, which defined the 20th-century city and only increased after the passage of the 1965 Hart-Celler Immigration Act. This interchange also structured King’s greatest anthem, “Stand By Me.” Written by Leiber and Stoller, who based it on a gospel standard, “Stand By Me” blended cha-cha rhythms with a call for community that resonated with Civil Rights workers, soldiers in Vietnam, and countless others who sought communal strength in the face of danger and isolation. King specialized in such juxtapositions.

On tracks like “Save the Last Dance for Me” and “I (Who Have Nothing),” King’s pained vocals cut through the rich arrangements to focus the listener’s attention on his call for connection. He didn’t just stand out – he often stood alone.

King’s astonishing run of hits slowed in the mid-1960s, a change that he blamed on the British Invasion and could also be attributed to the rising prominence of Motown, Memphis and other new capitals of R&B/soul. King was a major influence on all of those developments, of course, and the singer’s underrated output from in the late 1960s and early 1970s engaged fully with these new developments. He recorded striking covers of R&B-influenced British rockers Elton John and Van Morrison, and he embraced the deep grit of southern soul on records like 1967’s appropriately-titled “What Is Soul?” and his collaboration with super-group The Soul Clan, where he was a last-minute replacement for Wilson Pickett.

Although he scored mostly minor hits in this period, he returned to the charts in a big way with the sexy uptown funk of “Supernatural Thang,” a Top 10 in both Pop and R&B in 1975. He stayed funky on 1977’s Benny & Us, a collaboration with the Average White Band that produced several hits. The album’s highlight, the disco-drenched “A Star In The Ghetto,” was a loving tribute to black New York that refuted “benign neglect” myths of dysfunction and offered a fitting bookend for a singer who had so long celebrated the sounds and people of the multiracial city. At the moment when hip-hop created a new generation of artists meditating on New York’s promise and problems, “A Star In The Ghetto” is a beautiful amen from an elder statesmen.

Even as King earned his elder status, he still had an impact on the trajectories of pop even into the 21st century. In 2007, Jamaican reggae-pop singer Sean Kingston topped the U.S. charts with “Beautiful Girls,” which sampled “Stand By Me’s” backing track, and – in 2010 – New York-based bachata singer Prince Royce had his breakthrough hit with a Spanglish version of “Stand By Me” that offered a fitting 21st-century remix of King’s greatest anthem. That same year, King performed with Prince Royce at the Latin Grammys, a torch-passing that affirmed the musical and cultural connection between the generations. It was one of King’s last prominent public appearances.

Ben E. King’s legacy is rich and multifaceted. He was a singular artist, who had hits for four decades and left behind a wealth of remarkable recordings. As a key player in the R&B and soul revolution, he helped provoke a crucial shift in American popular music and the cultural language of the world. His life and art further symbolize broader cultural changes that shaped his life and defined his art. He reminds us all of the importance of community, and calls to us to stand by each other. He will be missed.

+++

Charles L. Hughes is assistant professor of history at Oklahoma State University. His book, Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American South, is now available from the University of North Carolina Press. Follow him on Twitter @CharlesLHughes2.

Published on May 04, 2015 20:22

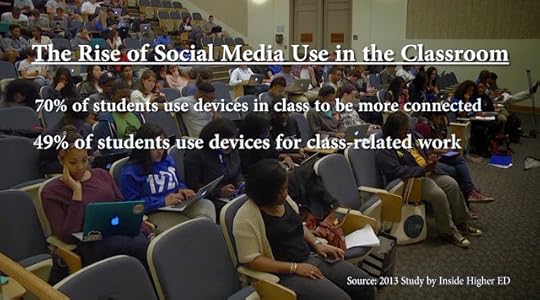

The Rise of Social Media Use in the Classroom

At Duke University, a rising number of professors are integrating social media into their classrooms and using it as a learning tool for students. Professor

Mark Anthony Neal

(

African & African American Studies

) and Dean of Undergraduate Education Stephen Nowicki discuss the future of social media in higher education with Duke student Kiara Brantley-Jones.

At Duke University, a rising number of professors are integrating social media into their classrooms and using it as a learning tool for students. Professor

Mark Anthony Neal

(

African & African American Studies

) and Dean of Undergraduate Education Stephen Nowicki discuss the future of social media in higher education with Duke student Kiara Brantley-Jones.

Published on May 04, 2015 08:39

Vocalist Bridget Ramsey Covers Classic "Fever" [video]

Vocalist Bridget Ramsey covers "Fever," made famous three generations ago by Little Willie John, from her forthcoming EP

B Eclectic

.

Vocalist Bridget Ramsey covers "Fever," made famous three generations ago by Little Willie John, from her forthcoming EP

B Eclectic

.

Published on May 04, 2015 08:00

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.