Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 732

May 23, 2015

The Art of #BlackLivesMatter: "Satellites"—New Music & Visuals from Bilal

New music and visual from Bilal, from his forthcoming In Another Life. Short film is directed by Hans Elder.

New music and visual from Bilal, from his forthcoming In Another Life. Short film is directed by Hans Elder.

Published on May 23, 2015 08:00

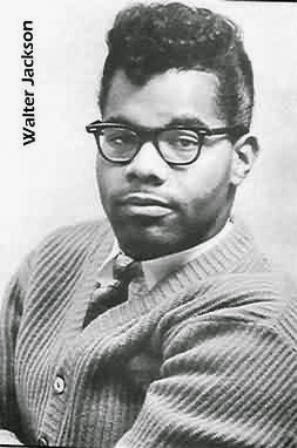

Walter Jackson -- "Speak Her Name" (1967)

Easily one of my favorite song-stylists, the Detroit-reared

Walter Jackson

(1938-1983) would eventually become a Chi-Town Soul classic with a series of recordings for OKeh in the 1960s and later in the mid-1970s on mentor Carl Davis's Chi-Sound Label. "Speak Her Name" (1967) is one of his signature tracks from his early days.

Easily one of my favorite song-stylists, the Detroit-reared

Walter Jackson

(1938-1983) would eventually become a Chi-Town Soul classic with a series of recordings for OKeh in the 1960s and later in the mid-1970s on mentor Carl Davis's Chi-Sound Label. "Speak Her Name" (1967) is one of his signature tracks from his early days.

Published on May 23, 2015 07:02

The Spin: #SayHerName—Remembering Aiyana Stanley-Jones & the Case of “White-on-White” Violence

On this episode of #TheSpin host

Esther Armah

is joined by

Shani Jamila

, dream hampton and

Glynda Carr

in a conversation about the anniversary of the death of Aiyana Stanley-Jones and the Waco, Texas shootout among rival "motorcycle clubs."

On this episode of #TheSpin host

Esther Armah

is joined by

Shani Jamila

, dream hampton and

Glynda Carr

in a conversation about the anniversary of the death of Aiyana Stanley-Jones and the Waco, Texas shootout among rival "motorcycle clubs."

Published on May 23, 2015 06:33

May 22, 2015

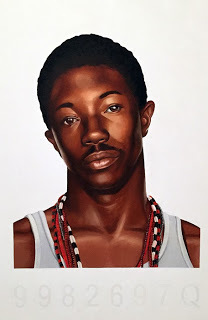

Eyes Wide Open: Kehinde Wiley’s Penetrating Plea for Grace by Simone C. Drake

PHOTO: KEITH BEDFORD FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNALEyes Wide Open: Kehinde Wiley’s Penetrating Plea for Graceby Simone Drake | @SimoneCDrake | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

PHOTO: KEITH BEDFORD FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNALEyes Wide Open: Kehinde Wiley’s Penetrating Plea for Graceby Simone Drake | @SimoneCDrake | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)California-native and New York-based artist, Kehinde Wiley, has established a highly recognizable painting style. In order to write African Americans largely, but also African-descended people globally, into historical, imperialist narratives as subjects rather than objects, Wiley inserts these raced figures—almost entirely male—into European visual art “masterpieces.” Wiley replaces the white European aristocracy with “everyday” black and brown people whose participation he solicits on the streets, initially in Harlem and, now, globally.

Wiley is best known for his photo-derived, grandiose images of young, urban, black men appropriating the stance and gestures of the subjects of classic Baroque and Rococo paintings. These massive portraits have displayed black men as heroic, confident, and regal, as in one of his most famous portrait paintings Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps (2005). But, they have also represented black men as tragically vulnerable and simultaneously beautiful, as in his Down series.

While art critics consistently note Wiley’s adoption of European conventions in the larger than life paintings that appropriate the originals, attention is not paid to subtle nuances. A particularly important nuance is how Wiley redirects and, therefore, empowers the gaze. The portrait Officer of the Hussars (2007) appropriates Romantic painter Théodore Géricault’s Officer of the Imperial Guard on Horseback (1812). In this portrait Wiley adds his trademark Baroque and Rococo decorative patterned backdrop to his rendition along with a black man—this time the man is wearing a white ‘wife-beater,’ relaxed-fit denim jeans worn at his hips, tan suede Timberland boots, and a purple satin jacket with rainbow-colored lining that is halfway on. With a saber in his right hand and a firm grip on the reins of the horse with his left hand, the male subject is seated on a bucking stallion that is positioned diagonally on the canvas, so that the subject must twist at his waist in order for viewers to see his face. Géricault’s rider does the same, but with a difference. Géricault’s rider’s gaze is directed toward the ground; Wiley’s rider is looking straight ahead, meeting the viewer’s gaze. It is, in fact, a repeating style in Wiley’s male portraits that the subject’s gaze is penetrating, demanding even.

While art critics consistently note Wiley’s adoption of European conventions in the larger than life paintings that appropriate the originals, attention is not paid to subtle nuances. A particularly important nuance is how Wiley redirects and, therefore, empowers the gaze. The portrait Officer of the Hussars (2007) appropriates Romantic painter Théodore Géricault’s Officer of the Imperial Guard on Horseback (1812). In this portrait Wiley adds his trademark Baroque and Rococo decorative patterned backdrop to his rendition along with a black man—this time the man is wearing a white ‘wife-beater,’ relaxed-fit denim jeans worn at his hips, tan suede Timberland boots, and a purple satin jacket with rainbow-colored lining that is halfway on. With a saber in his right hand and a firm grip on the reins of the horse with his left hand, the male subject is seated on a bucking stallion that is positioned diagonally on the canvas, so that the subject must twist at his waist in order for viewers to see his face. Géricault’s rider does the same, but with a difference. Géricault’s rider’s gaze is directed toward the ground; Wiley’s rider is looking straight ahead, meeting the viewer’s gaze. It is, in fact, a repeating style in Wiley’s male portraits that the subject’s gaze is penetrating, demanding even. Even before their arrivals on the shores of the Americas, it was firmly established that enslaved Africans were not to make eye contact with their white captors. The gaze was restricted to white evaluation and observation of black bodies. After emancipation, race codes continued to prevail, forcing black citizens to avert their gaze in the presence of whites. While Wiley surely reaches a black audience—most notably through several of his portraits being featured on Fox TV’s Empire—a white audience and white consumers are surely larger than his black audience. Thus, the penetrating gaze of his subjects reflects an agency in a position that once rendered them vulnerable and subordinate. And, to read deeper, in Officer of the Hussars, for example, given the homoerotic desire that both the posture of the rider’s body and prominent curvature of his exposed derrière evokes, one could also read the rider as penetrating the viewer with his own homoerotic gaze (instead of the heteropatriarchal phallus). Thus, the subjects’ gaze demands for viewers to critically analyze the masculinities at play when Timberlands, blackness, and Rococo meet.

Wiley’s persistent attention to rendering penetrating gazes and even re-directing gazes is, perhaps, best represented in the Down series. In it, Wiley’s appropriations are oil paintings and sculptures from the European Classical period to the Impressionist period. The Dead Christ in the Tomb (2007), Matador (2009), Femme piquée par un serpent (2008), Morpheus (2008), and from his World Stage Brazil series, Santos Dumont—The Father of Aviation II (2009), all redirect the gaze out toward the viewer rather than obscuring the gaze or turning it in toward the canvas as was the case in the prototypes. Given the contemporary social realities of many urban, young black men, downed (by gunshot) black men with eyes wide open seems to demand accountability from both the viewer and society at large. Depicting what, in many cases, is an honorable death—the death of Christ and bullfighters or angles in eternal sleep—the downed men whose eyes catch the eyes of the viewer break from scripted codes, but also seem to pose the question for the viewer: can you look beyond my color, bone, hair, and genitalia and imagine innocence for bodies that have been deemed unworthy of grace?

Perhaps unconvinced the message is clear enough, Wiley’s most recent productions function as a more explicit plea for grace. His 2015, fourteen-year retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum includes new works of stained glass, gold-embossed icon panels, and bronze busts. The new material—particularly the stained glass and icons—evokes Wiley’s 2006 Mugshot Study that, according to Wiley, made him begin to think differently about portraiture. An actual NYPD mugshot profile of a young black man that Wiley found on 125th St in Harlem when he was a resident at the Studio Museum inspired Mugshot Study. The paper included the young man’s name, address, arrest information, and physical description. It compelled Wiley to juxtapose this image that he insists is a type of “portraiture” with that of the traditional eighteenth century style of portraiture. Within this juxtaposition he was attuned to how the position of one is controlled by those in power (mugshot), whereas the subject controls positioning in the other. The stained glass images work to humanize the vulnerability captured in the mug shot—vulnerability in this case being the criminalizing fact of black maleness. Wiley pushes his audience to reimagine a type of portraiture for young black men that is unimaginable—that of sainthood.

When entering the gallery, the six stained glass images immediately draw your eye. They are inlaid in a hexagonal structure, making both the artwork and architecture resemble a Gothic cathedral. Appropriating a Gothic style is apropos given Wiley’s mission to humanize those who have lost control of their own representation. While the Byzantine period showed little interest in human form and the underlying structure of the body, Gothic art broke from rules of classical art, embracing the imagination and producing realistic images of the complete human form, including facial expressions reflecting the inner self. In Saint Ursula and the Virgin Martyrs (2014), for example, Saint Ursula is replaced with a black man. He retains her golden halo and quiver, which is the culprit in her death, but he sheds her Renaissance regalia and, instead, is clothed in Timberlands, patterned shorts, and a clashing patterned jacket with black fur collar. He is surrounded by a handful of the 11,000 virgin handmaidens who were also martyred with Ursula. Unlike the downed portraits, the subject in this composite does not look demanding. His head is tilted to the left, and his left shoulder is slightly hitched up, giving off an air of indifference or even deference. Rather than penetrating and directing the viewer’s gaze, his eyes are obscured by shadow. We do, however, see his eyes and the eyes of some of the virgins, which is not the case in the prototype. Thus, visible eyes, even when not penetrating, still call upon the viewer to see into the soul.

Given the time period of production, one cannot help but wonder if the very explicit casting of black men as saints and martyrs is in response to the contemporary high profile police and civilian violence directed toward black men. Many of Wiley’s oil paintings have, in fact, been replicas of Christ and various saints and martyrs. Those portraits, however, often emphasized style and bravado even when vulnerably positioned against “rosy” backdrops. The stained glass images exude the entangling of resoluteness, weariness, and, perhaps, even a hint of “shade” thrown at viewers. The facial expressions and body language suggest, perhaps, that the black models simply are tired of the gaze, are tired of the fleeting nature of grace for black men.

+++

Simone C. Drake is an assistant professor of African American and African Studies at The Ohio State University. She is the author of Critical Appropriations: African American Women and the Construction of Transnational Identity (LSU Press) and her second book, When We Imagine Grace: Black Men and Subject Making will be published next year by the University of Chicago Press.

Published on May 22, 2015 09:00

May 21, 2015

Baltimore Protesters Call “Amnesty for All” by Lamont Lilly

Baltimore Protesters Call “Amnesty for All”

by Lamont Lilly | @LamontLilly | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Baltimore Protesters Call “Amnesty for All”

by Lamont Lilly | @LamontLilly | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)On Saturday May 16th, hundreds of protesters gathered at downtown Baltimore’s McKeldin Square in a show of solidarity with the more than 500 (mostlyly Black youth) protesters who were arrested and jailed here over the last three weeks. While some arrestees have posted bail, many are still catching hell behind the walls of the Baltimore City Detention Center .

Organized by the Baltimore People’s Power Assembly (PPA), concerned community members spoke out and marched for three miles through Baltimore’s downtown and oppressed community, including Latrobe Homes. Community members of all nationalities were there to call for justice in the torture death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray by six Baltimore Police Department officers last month. It took more than a week — which included the rebellion and a five-day curfew — for these officers to be charged with Gray’s death.

In addition to honoring Brother Gray, others shared personal stories involving friends and loved ones who have also experienced negative encounters with Baltimore police – from racial profiling to beatings, to outright murder. It was obvious through public testimonies that the city of Baltimore does indeed have a very serious problem with police terror.

A rally led by Sharon Black and Rev. C.D. Witherspoon of the Baltimore People’s Power Assembly had protesters continuously chanting: “What do we want? AMNESTY! When do we want it? NOW!” Rev. Witherspoon reminded the local media and attendees, “This is an uprising, not a riot. Our resistance is justified.” His inspiring comments were right on time as the local police attempted to derail the route by way of an armed barricade.

Their intention was to cut off the route from entering the Black community in order to disconnect the oppressed from their supporters and allies. In a spontaneous show of sheer bravery, marchers refused to be moved and simply went around the police (despite their guns, tasers and mace close at waist-side). This small but heroic stand was important because the route was specifically mapped to cover the Black community, as well as stops at the Baltimore Juvenile Justice Center and the city’s Central Booking and Intake Center.

At both facilities community members spoke out against the state of Maryland’s recent approval to construct a new $30 million youth jail, which is only an insult to the recent rebellion. Speakers and protesters were careful to highlight the connections among police terror, militarization, the perpetuation of the prison-industrial complex through private prisons and the school-to-prison pipeline. It’s unfortunate how the city of Baltimore can find money for more jails and prisons, but not money for better schools and recreation centers.

Protest attendees were very conscious of the fact that most of the inmates incarcerated in Baltimore (Black youth from 18-30) are in actuality victims of racist systematic disenfranchisement, poverty and police terror — all ills of the capitalist crisis. Protesters were very aware that prisons and jails are merely tools that aid continued oppression and state-sponsored violence; which is exactly why local protesters are calling for full amnesty of all uprising-related arrestees.

Capitalism has run its course and the system has now failed, both workers and youth alike. Those incarcerated for speaking truth to power must be defended. Those detained for standing up for justice must be released. You don’t punish oppressed youth for seeking justice. You punish the oppressors who deny them justice. We say jail the “real thugs” — the judges and corrupt politicians. Free the people and jail the pigs! More schools, fewer prisons!

***

COME STAND IN SOLIDARITY: First Session of the Baltimore Tribunal & People’s Assembly on “Police Terror and Structural Racism,” Saturday, June 6th, 2-7 p.m. at New Unity Church (100 W. Franklin St. Baltimore, Maryland 21201). Come build community power. Join the Know Your Rights/Cop Watch Teams. For details and additional information, contact the PPA at 443-221-3775.

+++

Lamont Lilly is a contributing editor with the Triangle Free Press and frequent contributor to Truthout, Dissident Voice and The Durham News. Though based in Durham (NC), he is currently serving as a community organizer with the Baltimore People’s Power Assembly. Follow him on Twitter @LamontLilly.

Published on May 21, 2015 18:23

Arise Entertainment 360: Interview with Veteran Actor Antonio Fargas

Acting Legend

Antonio Fargas

talks with @lolaogunnaike + @patarack of Arise Entertainment 360.

Acting Legend

Antonio Fargas

talks with @lolaogunnaike + @patarack of Arise Entertainment 360.

Published on May 21, 2015 13:29

#SayHerName: New Visuals for Rapsody's "Hard to Choose"

Following her star-turn on Kendrick Lamar's "Complexion," Rapsody and Jamla Records release new visuals for "Hard to Choose" (produced by 9th Wonder; directed by Kent Willard) from the EP Beauty and the Beast. The song and video, with its message of Black Girl empowerment is a timely contribution to #SayHerName and #BlackGirlsMatter.

Following her star-turn on Kendrick Lamar's "Complexion," Rapsody and Jamla Records release new visuals for "Hard to Choose" (produced by 9th Wonder; directed by Kent Willard) from the EP Beauty and the Beast. The song and video, with its message of Black Girl empowerment is a timely contribution to #SayHerName and #BlackGirlsMatter.

Published on May 21, 2015 06:51

Highly Visible Invisibility: Black Women and the Politics of Representation in Baltimore

Highly Visible Invisibility: Black Women and the Politics of Representation in Baltimore

by Frances Henderson | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Representations of real and imagined black women in the US media have been fraught with contradictions and stereotypes, while simultaneously rendering black women invisible. The current upheaval in Baltimore City has forced several black women in to the spotlight in unexpected ways, but in ways that reify and challenge some of the standard stereotypes of black women (Jezebel, Sapphire, and Mammy) that dominate the cultural, political and media landscapes in the United States.

Here I focus on three black women, Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings Blake, Toya Graham and Baltimore City’s State Attorney Marilyn Mosby, all of whom were catapulted into the national and international spotlight by way of the upheaval in Baltimore in April 2015. In many ways the roles that black women were called upon to play in this scenario and the acts that the media chose to highlight, mirrored the stereotypical imaginings that white Americans hold about black women. I suggest that while these black women are highly visible, many black women activists, who have been working for years on the ground in Baltimore, and don’t fit into one of the stereotypes, remain invisible.

At the height of the Baltimore upheaval, the story that the national and international corporate media told about the riots was one that correctly reflected the fact that African American women in positions of military and political power were being used to discipline and hurt black bodies. The mayor of Baltimore, Stephanie Rawlings Blake faced the daunting and arduous task of “gaining control” over the sea of outraged black youth- called on the entire police force to report for duty, denounced the protests and violence as a bunch of “thugs” and discredited any articulation of the real material and social conditions that fueled the protestors. Surrounded by male black city council members, male black police officers and black ministers at her April 27th news conference, Mayor Rawlings Blake detailed her plan to restore order to the city (which included asking for assistance from Governor Larry Hogan), while the black men at the podium reinforced her decision by articulating over and over again that “looting” and “rioting” on the part of Baltimore city residents was unnecessary, counterproductive and barbaric. Shortly after the mayor’s press conference, white Governor Hogan used his podium to further denounce the “violence” and “looting” in Baltimore city.

Then something strange happened; he threw Baltimore’s black woman mayor under the bus, claiming that he didn’t understand why it took her so long to call on the governor’s office for help. Implicit in his comments (and not explicit ONLY because he never actually USED the word incompetent) was the suggestion that she was incompetent in handling the residents of her city, and had waited too long to use the entire breadth of disciplining force available to her as mayor. “We were trying to get in touch with the mayor for some time. We are glad she finally called us” Governor Hogan said. The white governor was flocked by all white men at his press conference, until he introduced, National Guard Major General, Linda Singh. Singh, a Black woman, stood at the podium, emitting a very clearly masculinized military persona as she described the role that the National Guard would play in restoring order to the city. The National Guard would assume supporting role to police, she maintained, but also said that they would be fully armed in case they needed to protect themselves. Again using black women to discipline black communities, but as the face of a justification for a violent response. It was unclear initially what the mayor felt in response to Gov. Hogan’s claims, as she refused to “play politics” by responding to Hogan’s assertions in later press conferences, but clearly, she had to have been feeling some kind of way.

The video of Toya Graham, a black mother disciplining her son by raining down a series of blows upon him after finding the boy among a group of young male protesters, is perhaps one of the most visible (and enduring) images of African American women during the Baltimore Protest. One of the things that immediately come to mind is the fear that she must have experienced, the understanding of what it meant to have her son participating in either rebellion or acts of protest, with his black male body-iness and burgeoning black masculinity on full display, despite, or perhaps because of his use of the face mask and hood. News reports say that she saw him in the crowd of African American teenaged boys throwing rocks at the police.

The fact that she recognized him in the crowd reflects the intimacy with which she knows her son; his walk, his mannerisms, his throwing arm. All of these things recognizable to her despite her distance from the crowd, the number of young men in the crowd and despite his covered face and head. She knew her son’s physical demeanor, perhaps more importantly she knew her son’s emotional and intellectual demeanor and that he was capable and probable of being influenced by those around him or, under the pressure of his own frustrations and helplessness as a young black male in Baltimore, to be involved in rebellion, whatever form it was going to take among the youth on the night of April 27, 2015.

This image, a mother beating her son in order to discipline him, probably out fear and as an attempt to save his life, is recognizable an understandable in the context of African American communities. Numerous FB friends chimed in with comments of “my momma would have done the same thing” or “beat that boy, mama, put him in his place.” To a certain extent many of us understand and are guilty of disciplining our black children at home in ways that we think will equip them with the appropriate set of skills in a society that does not value their confidence, courage or ability to shine. And yes, most times we (African American mothers) assert this is an act of love, and do so as what royblorn @crunkfeministcollective calls an act of radicality (radical love). But within the broader context of the representations, portrayals and imaginings of black women in the midst of the upheaval in Baltimore, white supremacy will not allow this mother’s beating of her child to be interpreted that way. Within the context and framework of the ghetto welfare queen, (the poor, lazy unaccountable welfare mom trope mixed with the emasculating, domineering black matriarch) that dominates discourse around poor black women’s identity and personhood, “this radical act of love” will be read and interpreted differently for and by those who consume it greedily as further evidence of our supposed deviance.

Instead, many who consume this act of mothering that would otherwise have occurred beyond the prying eyes of the media, will laud her for her condemnation of her son’s participation in the riots. Others will read the images of a black mother who beats her son in full view of the world (here gone viral globally) for participation in what was either in her eyes looting, or an illegitimate protest as an act not of radicality, but of further emasculation of a young black man at the hands of his mother, further personifying the Sapphire stereotype that dominates the cultural landscape.

Lest we forget “Bad Ass Marilyn Mosby.” State’s Attorney for Baltimore, who rounds out the triumvirate of highly visible black women examined here. Mosby, an African American woman who was elected as Baltimore’s States Attorney in fall 2014, is the lead prosecutor on the Freddie Gray case. On Friday, May 1st, Marilyn Mosby announced that she would use her office to bring charges against the 6 police officers who arrested Freddie Gray. In a fiery press conference, Mosby confidently outlined the scenario, as well as the charges against the officers and acknowledged the activists in the streets, saying she had heard their calls (“no justice, no peace”). Her announcement was met with shouts, screams and wails of relief from the gathered Baltimore city residents and protestors, but was immediately met with cries of incompetence from the conservative media and the Baltimore police union.

In usual fashion, the political pundits began to dissect every aspect of her case, her career, and her personal life in an attempt to discredit her. In addition to asserting that her charges unsupported, ill-conceived and rash, conservative bloggers and pundits argued that she sounded too angry to be unbiased and that her case would stoke the fires of racial animus in Baltimore, calling her a two bit political hack. Immediately, Mosby’s passion, intellect and desire to seek justice were “misshapen” in order to fit her into the angry black woman stereotype. Media portrayals of Mosby have mixed the angry black woman with the incompetent stereotype, placing her perspective, her expertise and knowledge of the law outside of the context of her job. Nonetheless, Mosby strikes fear and contempt in the hearts of her opponents and conservatives as she ploughs forward with case prosecution, jury selection and living her life (who would pass up the opportunity to attend a Prince concert as his special guest?).

Highly Visible yet still Invisible

The media’s portrayal and capturing of the role of black women in this scenario is troubling to say the least. What it speaks to is the absence of fully engaged representations of black women in public discourse and the simultaneous reification of stereotypes of black women as incompetent, emasculating, and domineering. But juxtapose these stereotypes of black women against the black women’s realities that have been rendered INVISIBLE in Baltimore right now. Black women in Baltimore have been at the forefront of the community protests against police brutality and the killing of black young men and women.

In her article “Many organizers at the forefront of protests are women, despite men taking center stage,” journalist Caitlin Goldblatt underlines the centrality of black women of Baltimore in the ongoing protests against police brutality and the death of Freddie Gray. Apparently, black women activists, mothers, wives, lovers, sisters and grandmothers, were organizing and marching long before April 12, but their voices have yet to be heard. Not heard in the sense that police brutality has not been eradicated in their community, but heard even in terms of an opportunity to speak truth to power through national media. Legions of black women, whose response to their sons’, daughters’ and community members troubled interactions with police has been sustained activism not outbursts of violence directed towards their own children, have been erased from media coverage and subsequently from the national spotlight.

While it is clear that corporate media leans towards coverage of the sensational, spin-able and the sexy, what is equally as clear here is the fact that inclusion of black women in the national discourse only occurs when they or their actions fit squarely within the preconceived notions of black womanhood. Toya Graham, Stephanie Rawlings Blake and Marilyn Mosby are, like the rest of us, black women who are much more complex than the racial stereotypes that dominate the media’s portrayal of their public persona and job. For many of us, the inability or unwillingness of the media to see and reflect this complexity in favor of reifying the stereotypes is not merely a disservice, it is a travesty, especially in light of the invisibility of the black women who lie at the margins of the spotlight, either because they lack the power, the platform or the good fortune (or misfortune) to have done something sensational enough for media coverage.

+++

Frances Henderson is an associate professor of political science at Maryville College. Her research interests include women and politics in southern Africa, black feminisms and social movements.

Published on May 21, 2015 03:41

May 20, 2015

#ArchivalMatters: Tom Scott--"Today" / Aaron McGrrduer--"Riley Wuz Here"

Perhaps one of the best uses of the archive, in layering and re-interpreting Black life, loss, memory and remembering for at least two-generations living with Hip-Hop. As much a tribute to the White saxophonist, Tom Scott , whose music serves as source material for both this episode of The Boondocks and Pete Rock & CL Smooth's "T.R.O.Y." as it is a reimagining of intellectual property; I am moved by [them] in all manifestation.

Published on May 20, 2015 13:53

Left of Black S5:E30: A Black Southern Poet on Spoken Word & Black Southern Culture

Left of Black S5:E30: A Black Southern Poet on Spoken Word & Black Southern Culture

Left of Black S5:E30: A Black Southern Poet on Spoken Word & Black Southern Culture

Left of Black host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) is joined in-studio by spoken word poet and writer Dasan Ahanu (@DasanAhanu). A member of the 2015 class of the Nasir Jones HipHop Fellows at the HipHop Archive and Research Institute at Harvard University, Ahanu is also assistant professor of English and Creative Writing at Saint Augustine’s University.

Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University and in conjunction with the Center for Arts, Digital Culture & Entrepreneurship (CADCE).

***

Episodes of Left of Black are also available for free download in @ iTunes U

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlack

Published on May 20, 2015 07:07

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.