Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1094

April 4, 2011

Teaching is Relationship Building: What School Reformers Often Forget

Teaching is Relationship Building:

What School Reformers Often Forget

by Mark Naison | Fordham University

One of the most pernicious examples of the tunnel vision of school reformers is the "school turnaround" concept incorporated in the Obama Administration "Race To the Top" legislation and currently being implemented in school districts throughout the nation. "Turnaround" strategy proposes that a school designated as "failing"-invariably on test scores- be closed and either replaced with a charter school or reopened as a new school, in the same facility, with a different principal and no more than fifty percent of the current teaching staff. Not only does this concept presume that "bad teachers" are the primary cause of a school's alleged failures, but it places no value on relationships that teachers build with students and their families, relationships that often last far beyond the time they were in class and are integral to student success and help sustain teacher morale even in the most daunting conditions.

Anyone who has been a teacher knows that building up the confidence of students and giving them the courage to realize their potential and find their voice involves more than classroom learning. It often requires individualized instruction and mentoring, joint participation in extracurricular activities and trips, and a commitment to maintain communication long after the student leaves your class. When this happens, students come to see relationships with their teachers as sources of strength throughout their lives, a form of "cultural capital" that allows them to surmount obstacles and realize their dreams. In working class and poor communities, where families are under constant stress, lifetime communication with teachers can be the critical factor enabling students to stay in school in the face of crises that would crush most people.

Janet Mayer's wonderful new book, As Bad As They Say: Three Decades of Teaching in the Bronx, provides example of example of how this longtime Bronx teacher supported her students through personal challenges that included evictions, murders, rapes, heatless homes, unemployed parents and responsibilities for raising younger siblings. This influence didn't just take place when students were in Mayer's classes. It often went on for fifteen or twenty years after they left her school. And it led to students who could have easily fallen through the cracks becoming productive, successful citizens, some of them teachers themselves.

The power of relationship building- something that cannot be measured by student performance on standardized tests- is something I have experienced over and over again in my own teaching at the college level. The most transformative moments in my teaching have not taken place during class sessions, or on midterm or final examinations, but it individual encounters with students where they confront obstacles and with my help, confronted strategies to overcome them

An example of this, from the late 90's remain etched in my memory. M was a Fordham basketball star from an Irish working class family in New Jersey, who along with some of her teammates, had enrolled in several of my Black history classes at Fordham . She was incredibly shy, never saying a word in class, but one day, she showed up in my office and started crying. "Dr Naison," she said, "I don't belong at this school. I only got 800 on my SAT's and I feel like everyone here is so much smarter than me. What am I going to do?" I took a deep breath, prayed I wouldn't screw this up, and started developing a strategy. "M, they aren't smarter than you, they just have more educated parents and went to better high schools. But we are going to overcome that. Every time you write a paper, hand me a rough draft a week before and I will edit if for you. Before every test, come with your friends to my office and I will give you a strategy for studying as a group. And in return, you and your friends can work with me on my crossover and spin moves!"

The last comment drew a reluctant smile from M and she went to work. Little by little, she went from being a C student, to a B student, to getting B+'s and A-'s in the last class she took with me during the second semester of her senior year. But the best part of this transformation was watching M find her voice. By the time she graduated, she was not only participating regularly In class discussions, she was being perceived as a leader by her fellow students, including those who came in to the school with much higher SAT's and grades. After she graduated from Fordham M's confidence only grew. After playing pro basketball in Europe for several years, she returned to New Jersey and became a teacher and coach, using her own hard won confidence to build the confidence of others.

In my forty years at Fordham, I have built many relationships with individual students I have taught, some of whom have gone on to become mayors of cities, leaders of government agencies, world renowned scholars and journalists, but no teaching or mentoring experience has been more satisfying than the one I had with M. Why? Because M represents the majority of students attending schools in America's poor and working class communities. They not only lack the skills that upper middle class students acquire in their families and the high performing schools they attend, they often suffer from a crippling lack of self-confidence in approaching the tasks that schools present. That confidence deficit, I am convinced, is at least as important as the skills deficit and it cannot be overcome through test prep drills and group instruction. It requires individual attention from teachers, and not just in a classroom setting. It requires extra work and encouragement after school, on weekends, and sometimes long after the student leaves the teachers direct care.

If you rotate teachers in and out of schools at a dizzying rate and create pressures that drive them out of the profession after a few years, you will destroy the relationship building component that is at the heart of great teaching. Ironically, under the pressure of federal mandates, this is being done in the very communities that have the greatest need for inspired teaching and mentoring.

***

Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies and History at Fordham University and Director of Fordham's Urban Studies Program. He is the author of three books and over 100 articles on African-American History, urban history, and the history of sports. His most recent book White Boy: A Memoir, published in the Spring of 2002.

Published on April 04, 2011 08:10

April 2, 2011

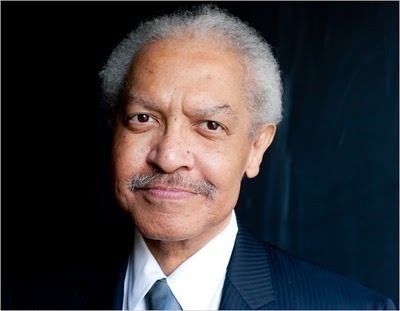

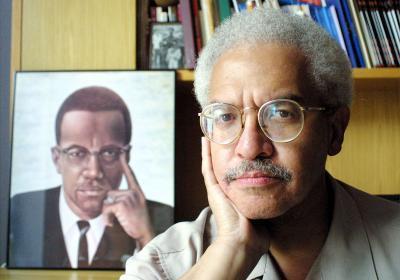

Malcolmology (Vol. 3 --Malcolm and Harlem--with Manning Marable

In Episode 3, "Malcolm and Harlem", Dr. Manning Marable discusses the early years of Malcolm's time in Harlem and his nascent political activism.

The Malcomology video project is a collaboration between truth2power films and Dr. Manning Marable, author of the new Malcolm X biography, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. Visit Dr. Marable's blog at http://detroitred.tumblr.com and truth2power films at http://truth2powerfilms.org/

Published on April 02, 2011 12:20

Malcolmology (Vol. 2)--Growing Up Garvey--with Manning Marable

This is the second installment of the Malcomology video project, a collaboration between truth2power films and Dr. Manning Marable, author of the new Malcolm X biography, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. Visit Dr. Marable's blog at http://detroitred.tumblr.com and truth2power films at http://truth2powerfilms.org/

In this episode, Growing Up Garvey, Dr. Marable discusses the political consciousness Malcolm developed at a young age.

Published on April 02, 2011 12:17

Malcolmology (Vol. 1) with Manning Marable

This is the first installment of the Malcomology video project, a collaboration between truth2power films and Dr. Manning Marable, author of the new Malcolm X biography, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. Visit Dr. Marable's blog at http://detroitred.tumblr.com and truth2power films at http://truth2powerfilms.org/

Published on April 02, 2011 12:05

On Eve of Redefining Malcolm X, Biographer Dies

from the New York Times

On Eve of Redefining Malcolm X, Biographer Dies

By Larry Rohter

For two decades, the Columbia University professor Manning Marable focused on the task he considered his life's work: redefining the legacy of Malcolm X. Last fall he completed "Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention," a 594-page biography described by the few scholars who have seen it as full of new and startling information and insights.

The book is scheduled to be published on Monday, and Mr. Marable had been looking forward to leading a vigorous public discussion of his ideas. But on Friday Mr. Marable, 60, died in a hospital in New York as a result of medical problems he thought he had overcome. Officials at Viking, which is publishing the book, said he was able to look at it before he died. But as his health wavered, they were scrambling to delay interviews, including an appearance on the "Today" show in which his findings would have finally been aired.

The book challenges both popular and scholarly portrayals of Malcolm X, the black nationalist leader, describing a man often subject to doubts about theology, politics and other matters, quite different from the figure of unswerving moral certitude that became an enduring symbol of African-American pride.

It is particularly critical of the celebrated "Autobiography of Malcolm X," now a staple of college reading lists, which was written with Alex Haley and which Mr. Marable described as "fictive." Drawing on diaries, private correspondence and surveillance records to a much greater extent than previous biographies, his book also suggests that the New York City Police Department and the F.B.I. had advance knowledge of Malcolm X's assassination but allowed it to happen and then deliberately bungled the investigation.

"This book gives us a richer, more profound, more complicated and more fully fleshed out Malcolm than we have ever had before," Michael Eric Dyson, the author of "Making Malcolm: The Myth and Meaning of Malcolm X" and a professor of sociology at Georgetown University, said on Thursday. "He's done as thorough and exhaustive a job as has ever been done in piecing together the life and evolution of Malcolm X, rescuing him from both the hagiography of uncritical advocates and the demonization of undeterred critics."

Over the course of a 35- year academic career, Mr. Marable wrote and edited numerous books about African-American politics and history, and remained one of the nation's leading Marxist historians. But the biography is likely to be regarded as his magnum opus. He obtained about 6,000 pages of F.B.I. files on Malcolm X through the Freedom of Information Act, as well as records from the Central Intelligence Agency, State Department and New York district attorney's office. He also interviewed members of Malcolm X's inner circle and security team, as well as others who were present when Malcolm X was shot to death.

Poor health had slowed his progress, but Mr. Marable remained optimistic. "For a quarter-century I have had sarcoidosis, an illness that gradually destroyed my pulmonary functions," he wrote in the volume's acknowledgments. "In the last year in researching this book, I could not travel and I carried oxygen tanks in order to breathe. In July 2010, I received a double lung transplant, and following two months' hospitalization, managed a full recovery." (An interview with The New York Times was planned, but did not take place.)

The book's account of the assassination of Malcolm X, then 39, on Feb. 21, 1965, is likely to be its most incendiary claim. Mr. Marable contends that although Malcolm X embraced mainstream Islam at least two years before his death, law-enforcement authorities continued to see him as a dangerous rabble-rouser.

"They had the mentality of wanting an assassination," Gerry Fulcher, a former New York City police detective who participated in the surveillance of Malcolm X, told Mr. Marable for the book.

That is why "law-enforcement agencies acted with reticence when it came to intervening with Malcolm's fate," the book asserts. "Rather than investigate the threats on his life, they stood back."

In a statement, Paul Browne, the chief spokesman for the Police Department, said, "As much as conspiracy theorists may press to reach a sweeping, unsupported and untrue conclusion, the fact is the N.Y.P.D. was not complicit in Malcolm X's assassination, and it's gratuitously false to suggest as much."

Based on his new material, Mr. Marable concluded that only one of the three men convicted of killing Malcolm X was involved in the assassination, and that the other two were at home that day. The real assassination squad, he writes, had four other members, with connections to the rival Nation of Islam's Newark mosque — two of whom are still alive and have never been charged.

Since Malcolm X's death, the posthumous "Autobiography," along with "Malcolm X," Spike Lee's 1992 film drawn from it, has made a pop-culture hero out of the man who was born Malcolm Little. But the Marable book contradicts and complicates key elements of his life story.

Malcolm X himself contributed to many of the fictions, Mr. Marable argues, by exaggerating, glossing over or omitting important incidents in his life. These episodes include a criminal career far more modest than he claimed, an early homosexual relationship with a white businessman, his mother's confinement in a mental hospital for nearly 25 years and secret meetings with leaders of groups as divergent as the Ku Klux Klan and the Palestine Liberation Organization.

"Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention" shows, for instance, that at a time when Malcolm X claimed in the autobiography to have "devoted himself to increasingly violent crime" in New York, he was actually in Lansing, Mich., his hometown. Mr. Marable attributes the embroidery of "amateurish attempts at gangsterism" to Malcolm X's wish to demonstrate that the Nation of Islam's gospel of pride and self-respect had the power to redeem even the most depraved criminal.

"In many ways, the published book is more Haley's than its author's," Mr. Marable writes, noting that Haley, who died in 1992, was a liberal Republican and staunch integrationist who held "racial separation and religious extremism in contempt" but was "fascinated by the tortured tale of Malcolm's personal life."

The book maintains that several chapters of the autobiography explaining Malcolm X's evolving but still radical political vision were deleted before publication, perhaps out of Haley's desire to produce a work that "frames his subject firmly within mainstream civil rights respectability at the end of his life."

The Marable book also sheds new light on Malcolm X's departure from the Nation of Islam and the subsequent feud with the organization and its founder, Elijah Muhammad, preceding his assassination. That split is usually attributed to theological and political differences and the jealousy of Muhammad's children and inner circle.

But Mr. Marable also points to an episode of almost Oedipal sexual duplicity, in which Elijah Muhammad impregnated a woman Malcolm X had loved since he was a young man. "Malcolm must have felt a deep sense of betrayal," Mr. Marable writes.

Malcolm X's subsequent trip to Mecca in 1964 — a likely turning point in his religious evolution — was recounted in both the autobiography and the biopic. The Marable book, however, provides extensive new material about a second, 24-week trip to Africa and the Middle East later that year, drawing on Malcolm X's own travel diary and providing details on a campaign he waged to have the United States condemned for racism in a vote at the United Nations.

As part of that effort to open a foreign front for the civil rights struggle, which was closely monitored by American governmental agencies, Malcolm X met with numerous African heads of state as well as Chinese and Cuban diplomats. The Johnson administration was so upset, Mr. Marable writes, that Nicholas Katzenbach, the acting attorney general, considered prosecuting him for violating a law that bans United States citizens from negotiating with foreign states.

"These are new facts being unveiled, showing just how serious and sustained was Malcolm's interest in the global dimension" of the domestic civil rights struggle, Mr. Dyson said. "They really do suggest he was a subversive figure, trying to undermine the best interests of the U.S. government" in the name of a larger pan-African cause. "That is a fresh insight, one of many."

Mr. Marable's editor, Wendy Wolf, said Friday evening that "his every fiber was devoted to the completion of this book." She added: "It's heartbreaking he won't be here on publication day with us."

Published on April 02, 2011 11:47

Manning Marable: A Brother, a Mentor, a Great Mind

Michael Eric Dyson recalls the pioneering scholar as a 20th-century Frederick Douglass who nurtured and inspired talented young academics.

Manning Marable: A Brother, a Mentor, a Great Mind

by Michael Eric Dyson | The Root.com

I discovered Manning Marable as a 21-year-old freshman at Knoxville College, a historically black college I'd left my native Detroit to attend after working in factories and fathering a son during the time most college-bound kids are in school.

I was in the library stacks, browsing the sociology section, when I came upon a book that grabbed my attention: From the Grassroots: Social and Political Essays Towards Afro-American Liberation. It was clear that Marable's left politics reflected how he had baptized classic European social theory in the black experience. "Wow," I said to myself. "If Karl Marx was a brother, this is how he'd write and think."

The author photo on this intriguing book showed a young man with a handsome face that was crowned by a shock of black hair whose woolly Afro styling conjured a 20th-century Frederick Douglass. As I was to learn later, the comparison to Douglass didn't end at the 'fro, since Marable, like his 19th-century predecessor, was an eloquent spokesman for the democratic dreams of despised black people.

As I devoured Marable's brilliant work -- including his quick 1980 follow-up, Blackwater: Historical Studies in Race, Class Consciousness, and Revolution, and his pioneering 1983 work, How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America -- I knew I was in the presence of a world-class intellectual who lent his learning to the liberation of the vulnerable masses. I was impressed that a man so smart and accomplished could so unashamedly identify with struggling black folk -- and I was really impressed that he was so young, only eight years older than I.

Years later, when he invited me to Columbia to teach as a visiting professor in the late '90s, and I recalled again to Marable my introduction to his work, he flashed that magnetic smile of his and said that he was glad his books could help a brilliant young intellectual find his way. That, of course, was vintage Marable: deflecting attention from his Herculean efforts to parse the meaning of black political destiny by embracing the promise of a younger colleague.

And that wasn't just something he did with me; Marable nurtured and guided a veritable tribe of graduate students and junior professors as they sought sure footing in the academy. He was generous with his time and insight; he had a real talent for spotting rising stars, and a genius for tutelage and inspiration, with either a bon mot if time was short or a hearty, dynamic, luxurious, sprawling conversation when you were blessed to find his inner circle.

Read the Full Essay @ The Root.com

Published on April 02, 2011 11:42

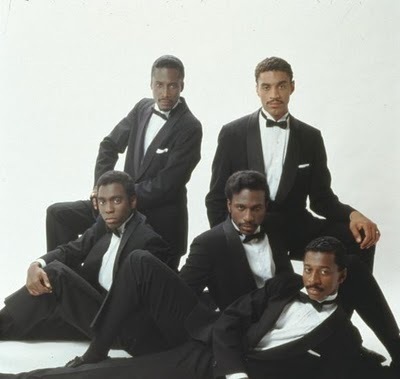

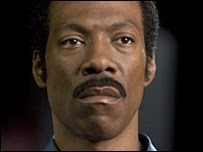

The Life and Times of Eddie King, Jr.

The Life and Times of Eddie King, Jr.

by Mark Anthony Neal

Filmmaker Robert Townsend didn't have to conjure Eddie King, Jr., the lead singer from the fictional soul group The Five Heartbeats, the subjects of Townsend's 1991 film of the same title. Well known at the time was the role of The Dells, legendary hit-makers with songs like "Oh What a Night" and "Stay (In my Corner)," as the film's consultants. And while the Dells' career resembles nothing like the drama that shapes The Five Heartbeats, as veterans of the chitlin' circuit, they of course had stories to share.

Townsend also could draw on the tradition of the male Soul singer—the proverbial Soul Man—an iconic figure from the 1960s and 1970s that congealed grand narratives of tragedy—shot dead in a motel; shot dead by your father; shot dead in a game of Russian Roulette; killed in an airplane crash; scorched by a pot of boiling grits, paralyzed in a car accident, marrying your dead mentor's wife months after his death—wedded to even more complicated personal demons—physical abuse of wives and girlfriends; sexual assault of younger female artists; sex with underage girls.

Conventional wisdom is that these tragedies were the price that these men were damned to pay for offering their Godly gifts of voice for sale in the marketplace of the flesh. And immediately we can see Choir Boy, the Five Heartbeats' falsetto voiced singer, arguing with his preacher dad about the temptations of being out on the road. What was Choir Boy's story line was likely applicable for the majority of these men who took a leap of faith—literally—and hoped that those gifts from God would translate into some modicum of fame and the ability to live the "good life," for a generation of black folk, for which such themes were always simply an ideal. The glitz and glamour of those early Motown days were more wishful thinking than anything—just look at the building in Detroit that housed the famed "Hitsville, USA."

And whatever the tragedies that befell these men, they were not occur in isolation; in the decades before the internet and 24-hour new cycles, and when Jet Magazine was effectively Black America's social media, the Soul Man was the secular brethren of the equally iconic Race Man—figures who were dually in a noble (and decidedly patriarchal) struggle against good and evil; blackness and whiteness; military aggression and pacifism; sex and love; and "class and crass" to quote another fictional Soul Man, Dream Girls' Curtis Taylor. These men existed at the same crossroads where legendary Bluesman Robert Johnson allegedly sold his soul to the devil (and damn if his BET founding namesake ain't been every bit the devil); a subtle reminder that if Huey Newton or Medgar Evers had been able to carry a tune or two over a Motown backbeat or a Stax horn chart, they might have still been in the line of fire.

When Townsend's The Five Heartbeats was released in March of 1991, audiences might have still been aching over the shocking murder of Marvin Gaye, 6 years and 362 days earlier. In truth, Michael Wright's Eddie King, Jr., most evoked the troubled and tragic soul that was David Ruffin, lead singer of the most classic Temptations' lineup from 1964, until his ouster in 1968, though Five Heartbeats cast-mate Leon would better perfect Ruffin's cavalier brilliance in his portrait of him for the television mini-series The Temptations (1997).

Townsend's movie was released only months after the first of two box-set collections of Gaye's musical career was released, a moment that demanded a re-evaluation of Gaye's career, which could be heard in the generation of R&B singers that emerged in the 1990s including Kenny Lattimore, Maxwell, D'Angelo and perhaps, most dramatically, Robert Sylvester Kelly. As the quintessential Soul Man (save Sam Cooke, who served as the template), it was not difficult to read Gaye onto Eddie King, Jr. or a generation later, Eddie Murphy's stellar portrait of the fictional James "Thunder" Early in the film adaptation of Dreamgirls.

In many ways the specter of Marvin Gaye continues to haunt contemporary imaginations of Soul Men. Perhaps it's because Marvin Gaye was a project incomplete—we all long for what Gaye might have had to say about the Hip-hop generation that was just emerging when he took his last breathe and how he might have engaged the music that was produced in its wake. I for one, wonder what Gaye might have had to say to Mr. Kelly—men who could be accused of, but never convicted of the same crime; like I said there are stories to tell.

But what makes Gaye's music so singular, is that he never seemed to seek redemption—he seemed almost tragically comfortable with the duality of his experiences and his duel lust for God and the flesh—thinking of his description of sex, fucking really, as "something like sanctified." Indeed figures as diverse as Al Green, Teddy Pendergrass, Ronald Isley, Charlie Wilson—and yes, even Mr. Kelley, have actively sought, and in some cases found redemption.

Even Eddie King, Jr. found his redemption, singing Rance Allen's "I Feel Like Going On" in one of the most memorable scenes from The Five Heartbeats. There are no such moments in Gaye's career—even his most lasting performance, singing the National Anthem at the 1983 All-star game in Los Angeles, was not so much an attempt at redemption, as it was one last dig at the failings of American Democracy—that programmed back-beat a reminder of the Black humanity that lie at the center of a radical Democratic project.

And it is perhaps this lack of resolution that makes Marvin Gaye such a difficult cinematic subject—and perhaps the very reason the idea of Eddie King, Jr.—and all the men who contributed to his mythic creation, will continue to resonate well after The Five Heartbeats are forgotten.

Published on April 02, 2011 06:42

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.