Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1092

April 11, 2011

'Left of Black': Episode #29 featuring Kimberly Ellis and Randal Jelks

Left of Black #29

w/ Kimberly Ellis and Randal Jelks

March 21, 2011

Left of Black host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal is joined by Pittsburgh based scholar, activist, and artist Kimberly Ellis aka Dr. Goddess in a conversation about Pittsburgh's Hill District and the release of the new DVD Dr. Goddess Goes to Jail. Later Neal talks with Randal Jelks, Professor of African-American Studies at the University of Kansas, about the recent ESPN 30 for 30 documentary The Fab 5.

***

→Named one of the "Most Influential Black Women on Twitter" by "For Harriet" Digital Magazine, Kimberly Ellis aka Dr. Goddess is a writer, an entertainer, an entrepreneur, a scholar, and activist. Dr. Goddess is also an award-winning poet, playwright and performing artist, who is presently on tour with, Dr. Goddess!: A One Woman Show and screenings of its sequel, the ensemble production of Dr. Goddess Goes to Jail: A Spoken Word, Musical Comedy (Unfortunately) Based on a True Story, now on DVD. Follow her on Twitter @DrGoddess.

→Randal Jelks is an Associate Professor of American Studies at the University of Kansas with a joint appointment in African and African American Studies. He is the author of African Americans in the Furniture City: the Civil Rights Struggle in Grand Rapids, Michigan . He is currently finishing a book on Martin Luther King Jr.'s mentor titled Benjamin Elijah Mays, A Religious Rebel in the Jim Crow South: An Intellectual Biography to be published by the University of North Carolina Press.

***

Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University.

Atelier@Duke: Private Bodies

Atelier@Duke: Private Bodies

February 25, 2011

Panelists at the Atelier@Duke symposium discuss "Private Bodies," the fourth of five panels at the Atelier@Duke, an event marking the 15th anniversary of the John Hope Franklin Research Center at Duke University Libraries.

Panelists include Harriet Washington (Author, Medical Apartheid), Charmaine Royal (Duke), Alondra Nelson (Columbia), Anne Lyerly (UNC-CH), and moderator Karla Holloway (Duke).

Small Business Nation- Understanding the Social Base of Tea Party America

Small Business Nation: Understanding the Social Base of Tea Party America

by Mark Naison | Fordham University

Before he moved away after a bitter divorce, I had many an interesting conversation about politics with my Long Island neighbor John, a union carpenter and life time "Bonacker" (resident of the East End of Long Island). A tough navy veteran with a crew cut who still, in his mid fifties, looked in fighting trim, John would stop by every time he saw I was in and hold forth on all his pet peeves--which were many--while we went through the beer in my refrigerator. Among his favorite targets were politicians, the government, his wife's relatives, rich people in the Hamptons, and lawyers and insurance companies. John was still raging that he had never collected any money from an accident he had several when he fell off a roof during his home repair job, an accident that had left him with chronic back pain.

Nevertheless, John continued to do "side jobs" on the weekends, ranging from painting houses to repairing fences, because his salary at the lumber yard couldn't pay for the "extras" in his life, ranging from fishing trips, to family vacations, to his daughters acting and dance classes. He was tired, angry, hard pressed, glad he had me he could vent with, a need that became even greater when he discovered his wife was cheating on him. Since he moved out just before the 2008 election, I never had chance to explore his attitudes about the Obama Presidency, but I wouldn't be surprised if, like one of my other LI neighbors, a postal worker, he became a supporter of the Tea Party.

A glimpse at John's life suggests why it is a perilous venture to look at Tea Party affiliation strictly as an example of false consciousness, of people voting against their own interests. While the Tea Party movement was funded and has been supported by powerful corporate interests, its popularity was not manufactured. It's anti-government, anti-tax message has struck a powerful chord with millions of white middle class and working class people who feel embattled and pushed to the edge and whose identify with business, rather than labor, because small scale entrepreneurship is the only thing that stands between them and poverty.

To understand this, you have to get to know people in small town and suburban America and see how they patch together income. As real wages have stagnated during the last thirty years, more and more people have depended on performing "side jobs" as independent contractors to maintain a middle class standard of living. They drive cabs, paint houses, do child care, fix computers, teach golf, take people on fishing trips, exploring whatever "niche" in the local economy allows them to make extra income.

Some jobs they take –bartending, waitressing- involve working for others, but more and more people create their own one or two person businesses to bring in needed income.

This is the hidden side of the "Wal Martization" of America. We all know of how people have used credit card debt and second mortgages on their homes to finance middle class levels of consumption, but what is less known is how many people have developed small "side businesses" to supplement their main jobs. If John is any example, the stress and risk associated with this can be pretty high and the margin for error quite small.

Given this, is it any surprise that people who run small individual businesses see any tax increase as a threat to their livelihood, and are deeply resentful of government workers who have job security, pensions and an income that can support them, starting a business on the side?

How else do you explain the huge Republican votes in places like Wisconsin, Michigan and Ohio, states whose economies once featured auto plants and steel mills and now have more jobs in Wall Mart, Auto Zone and McDonalds than factories. Small individual business, along with consumer credit, have been the only ways working people have maintained a decent standard of living, and they see government as more an enemy than an aid in that effort.

Beneath all the racism, and the voodoo economics in the Tea Party movement, there is genuine desperation, and a cry for help. Until we address the causes of economic insecurity in their lives, progressive politics in America may be stalled for a generation.

***

Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies and History at Fordham University and Director of Fordham's Urban Studies Program. He is the author of three books and over 100 articles on African-American History, urban history, and the history of sports. His most recent book White Boy: A Memoir, published in the Spring of 2002.

April 10, 2011

Atelier@Duke: Representing Global Blackness

February 25, 2011: Panelists at the Atelier@Duke symposium discuss "Representing Global Blackness," the second of five panels at the Atelier@Duke, an event marking the 15th anniversary of the John Hope Franklin Research Center at Duke University Libraries.

Panelists include Ian Baucom (Duke), Farah Jasmine Griffin (Columbia), Charles Piot (Duke), Deborah A. Thomas (Penn), and moderator Lee Baker (Duke).

April 9, 2011

Neocolonial Fantasies: Whiteness and Hop

special to NewBlackMan

Neocolonial Fantasies: Whiteness and Hop

by David J. Leonard

I spent my Sunday like so many other days as of late at the movies with my 7-year old daughter. We, like millions of other American, headed to the theaters to watch Hop, the most recent offering from the writing-producing-writing group that brought us Despicable Me. The film, a trite and clichéd buddy picture, chronicles the mutual coming of age stories of E.B. (Russell Brand), who longs to be a rock star and not follow in the footsteps of his Easter Bunny father, and Fred (James Marsden), a 20-something loser who is floundering his way through life. Together they not only assist in each other, teaching each to appreciate their own talents and think of others, all while ultimately saving Easter.

The narrative is not especially innovative, although the absence of a princess or a story focusing on a girl being saved by a male protagonist was a refreshing change. That being said, the absence of any females characters of substance and the focus on fathers-sons gave me pause, especially in light of that so many of children's films centering female characters do so through a patriarchal fantasy. What also gave me pause was how the film depicted the factory located in a remote location deep below Easter Island.

As the factory boss, the Easter Bunny (Hugh Laurie) is a traditionalist who's English accent, his tie, and his bellowing voice is strikingly colonial. It is hard to avoid the colonial history embodied within the film in its efforts to represent the benevolent and kindhearted English gentle rabbits, whereas the chicks, embodied by heavily accented Carlos (Hank Azaria), are the grunt sweatshop workers. Worse yet, under the leadership of Carlos, the chick unsuccessfully organizes a coup against the Easter bunny, planning to replace the traditional Easter offerings with more chick friendly treats. With rare exception reviews about the film have offered little insight and commentary about the films' racial meaning. Robert Abele writes, "And why is it that the piece's nominal villain is a coup-organizing Speedy Gonzales-accented factory chick . . . , while his boss rabbit speaks like a posh Brit? Or is that a class-race over-read?").

Yet, the racial text that defines tradition, virtue, and class-based respectability through colonial whiteness against a racialized colonial otherness that scheme against tradition, goodness, and civilization is instructive as one considers how the film imagines the working conditions of the chocolate factory. Pristine, orderly, happy, clean, and enchanting, the factory is depicted as magical. It is a place where dreams come true, where the treats for millions of children are produced each and every year. Not surprisingly, the film does not represent the chick as enslaved chicks producing chocolate in slave-like conditions. According to Global Exchange, "Approximately 286,000 children between the ages of nine and twelve have been reported to work on cocoa farms on the Ivory Coast alone with as many as 12,000 likely to have arrived in their situation as a result of child trafficking." Working 80-100 hours per week under horrible conditions, the children who harvest cocoa are modern-day slaves.

The erasure of working conditions that produce the chocolates that fill American Easter baskets is not the only compelling narrative that is absent from Hop and larger understanding of this American commercial holiday. As noted by Kevin Thull, in, the commercialization of Easter is the coming together of a myriad of injustices from the environmental degradation that results from plastic eggs and baskets to the toys produced in sweatshops. Last, but not least, are the cute little stuffed animals and little toys that often find their way into Easter baskets," Writes Thull, "Those toys are more than likely produced with shamefully cheap foreign labor or by mega-corporations that care more for profits than the environment."

Hop demonstrates the power and importance of media literacy. It illustrates the power of the white racial frame and narratives that imagine commodities apart from working conditions, struggle, and neo-colonialism.

***

David J. Leonard is an associate professor in the Department of Comparative Ethnic Studies at Washington State University at Pullman. His next book (SUNY Press) is on the NBA after the November 2004 brawl during a Pacers-Pistons game at the The Palace of Auburn Hills He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums.

John Legend Tributes Adele's 'Rolling in the Deep'

A brilliant rendition of Adele's brilliant song.

April 8, 2011

Live Taping of 'Left of Black' with Karla FC Holloway

Join Mark Anthony Neal for a live taping of Left of Black on Wednesday April 13, 2011 featuring Karla FC Holloway, James B. Duke Professor of English and Professor of Law at Duke University and the author of the new book Private Bodies/Public Texts: Race, Gender, and a Cultural Bioethics (Duke University Press, 2011). The special taping is being held in conjunction with the regular Wednesdays @ the Center programming at the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University. The Gothic Bookshop will have copies of Private Bodies/Public Texts: Race, Gender, and a Cultural Bioethics for sale.

Wednesday @ The Center

Left of Black with Mark Anthony Neal and Karla FC Holloway

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

12:00 Noon

The John Hope Franklin Center for Interdisciplinary & International Studies

2204 Erwin Road

Durham, NC 27708-0402

Room 240

April 7, 2011

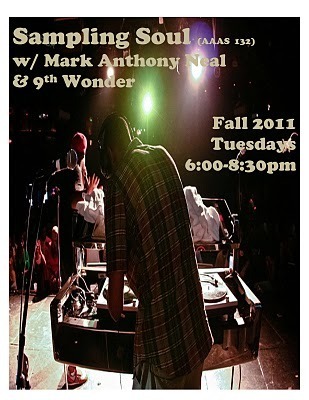

Sampling Soul--Duke University Fall 2011

Black Popular Culture—Sampling Soul (AAAS 132)

Mark Anthony Neal and 9th Wonder (Patrick Douthit)

Fall Semester 2011

White Lecture Hall 107

Tuesdays 6:00pm -- 8:25pm

***

Soul Music emerged in the late 1950s and became the secular soundtrack of the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Artists such as Aretha Franklin and James Brown and record companies such as Motown and Stax, as well as the term Soul became symbols of black aspiration and black political engagement. In the decades since the rise of Soul, the music and its icons are continuously referenced in contemporary popular culture via movie trailers, commercials, television sitcoms and of course music. In the process Soul has become a significant and lucrative cultural archive.

Co-taught with Grammy Award winning producer 9th Wonder and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal, Sampling Soul will examine how the concept of Soul has functioned as raw data for contemporary forms of cultural expression. In addition the course will consider the broader cultural implications of sampling, in the practices of parody and collage, and the legal ramifications of sampling within the context of intellectual property law. The course also offers the opportunity to rethink the concept of archival material in the digital age.

Report on Black Male Prison Population: Marc Lamont Hill Repsonds (MSNBC)

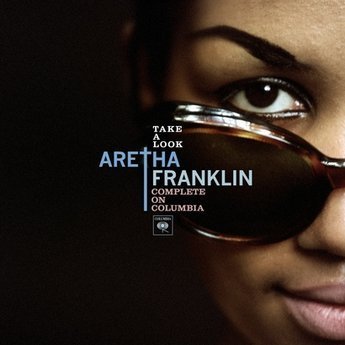

Chasing Aretha: The Columbia Years

Take a Look: Aretha Franklin Complete On Columbia features enough resonances of the Aretha Franklin that we have all come to (think we) know, that it demands a revaluation of Franklin's career; one that inevitably only enhances her reputation as that of the greatest vocalist of the 20th Century.

Chasing Aretha: The Columbia Years

by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan

It is not unusual to hear the phrase "national treasure" used to describe the legacy of Aretha Franklin. Whether thinking her the voice of the Civil Rights Movement, or the embodiment of a womanish Black respectability in the late 1960s and 1970s, or her iconic performance at the inauguration of the 44th President, Aretha Franklin remains one of this country's greatest creations. As such, there is a feeling that we all know her—how casually many of us simply refer to her as Aretha, as we all sing the lyrics to "Respect," a song that was originally written and recorded by the late Otis Redding. For far too many, Franklin's singular career began somewhere in Muscle Shoals country, at a mythic recording session that created some of the best music of an era—and if folk have a longer history to tap, it's remembering Ms. Franklin as a 14-year-old singing in her father's Detroit church.

The new collection Take a Look: Aretha Franklin Complete on Columbia offers a new view of Franklin's oft-forgotten career at Columbia Records, from 1960-1966, before she was signed by Jerry Wexler for Atlantic Records. As Daphne Brooks writes in an inspired essay that accompanies the collection, "So today, she is our national treasure…singing us ever so righteously into a colorful, new tomorrow. Hard to believe that, fifty years ago, she was an ingénue, stepping up to the microphone in the New York City studios of Columbia Records, boldly sounding out the ambitions of modern black womanhood at the dawn of the Civil Rights era." Brooks' counter reading of Franklin's Columbia career, which has often been best described as the "Queen in Waiting," suggests the need for a revisionist view of the 18-year-old who came to the big city in 1960 and by decade's end was the most visible Black woman on earth. Jerry Wexler, Atlantic Records and even the Civil Rights movement can't take all the credit for that.

Because of previously released material from Franklin's Columbia catalogue, a portrait of her early career has been crafted, that easily distinguishes those recordings from the weightier Atlantic years; recordings which clearly overshadow her days with Columbia. Perhaps that is the way that Columbia has desired those records to be interpreted, since it provides the label with a distinct Aretha brand, that while generally less impressive than the body of work that Franklin produced from 1967-1978 (her Atlantic years), positions her as almost a separate and distinct artist. Franklin's primary repertoire at Columbia was torch songs, 1960s styles pop balladry (in the vein of late stage Dinah Washington and early Dionne Warwick—she covers both), and show tunes. An easy narrative suggest that at Columbia, Franklin was perhaps, not gritty enough, not soulful enough, not Black enough, and the Aretha that literally Arrives in 1967 is the real, authentic Franklin. In her essay "Bold Soul Ingénue," Brooks challenges such assessments, arguing that "Skeptics who stereotype Aretha as the 'earthy,' 'natural' woman who only connected with her 'soul' on Atlantic Records conveniently forget the active role that she played in developing her own virtuosic talents as a musician…Calling Aretha a 'natural' diminishes our appreciation of the ways that she worked hard at cultivating her craft."

Take a Look: Aretha Franklin Complete On Columbia—which features seven albums released while Franklin was at the label, unreleased sessions with producers Clyde Otis and Bobby Scott, and post-Columbia era over-dubs and singles—features enough resonances of the Aretha Franklin that we have all come to (think we) know, that it demands a revaluation of Franklin's career; one that inevitably only enhances her reputation as that of the greatest vocalist of the 20th Century. Say what you want about standard bearers like Frank Sinatra and Barbara Streisand—neither could sing "Amazing Grace"—yet Ms. Franklin could have sang anything on In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning and indeed sings Streisand's "People" (from the musical Funny Girl) and has recently recorded a duet with Ronald Isley of Streisand's signature "The Way We Were."

The career trajectory Franklin's Columbia label-mate Streisand offers an instructive view of the limits that were place on Franklin during her career at the label. Streisand could be Streisand throughout the 1960s, without the encroachment of the Top-40 music scene (until it was her choice in the early 1970s), in part, because as a White female performer, she was allowed to simply exist an interpreter of show tunes and the like. Though Franklin's Laughing on the Outside (1962), in retrospect, represents Columbia's most successful attempt to package Franklin as a darling of the supper-club set, with brilliant interpretations of "For All We Know" (later covered by Donny Hathaway and Roberta Flack for Atlantic), "If Ever I Would Leave You" and the Franklin original "I Wonder (Where You Are Tonight)," the marketplace for Black artist in the early 1960s—with few exceptions—demanded they follow the gravy train of Motown (Ms. Franklin unconvincingly covers Mary Well's "My Guy"), Stax and Warwick's tailored-as-silk Soul/Pop confections. The Soul sound that we most associate with Ms. Franklin was still five years in the future.

Franklin's 1960 debut, simply called Aretha, paired her with the talents of pianist Ray Bryant, who also served as the musical director for the session. The session was produced by John Hammond, whose resume at the time included work with Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday. At 18-years-old, Franklin's signature talents were already on display on tracks like "Maybe I'm a Fool" and "Today I Sing the Blues." When Franklin reprises "Today I Sing the Blues" on her Atlantic recording Soul '69—in many ways a tribute that initial session—it was clear that she was then a grown woman singing the song ("today my story's a little different").

Revelatory from that first session is Franklin's rendition of "Somewhere Over the Rainbow." The song, which Judy Garland performed in The Wizard of Oz had generated renewed interest when the soundtrack from the film was released to coincide with the television premiere of the film in 1956. In the 1960s "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" would become a favorite tune for a young Patti Labelle, then fronting The Bluebelles. Though the song still remains Labelle's signature, there are resonances of Franklin's early version on that Labelle's cover, which in many ways erases Garland's imprint on the song.

Indeed one of the purely musical pleasures of listening Franklin's Columbia catalogue in its full contexts is hearing early gestures towards what Franklin's music would sound like when she was at her artistic peak in the 1970s. For example "It's So Heartbreaking," from The Electrifying Aretha Franklin (1961) features a piano introduction, that Franklin would later resuscitate as the introduction to her remake of Ben E. King's "Don't Play That Song" from her classic Atlantic outing Spirit in the Dark (1970). What was arguably a throwaway in 1961, became a critical component to one of her most popular tracks from the early 1970s; more evidence that Franklin's later career was always in conversation with her earlier recordings—a reminder that the Aretha Franklin that she became was, in part, a product of working with men like her father, John Hammond, Ray Bryant, Clyde Otis and Bobby Scott and developing her own musical sensibilities in response.

Franklin's recordings The Tender, The Moving, The Swinging Aretha (1962) and Laughing on the Outside (1963) find Franklin coming into her own as a vocalist; her renditions of "Just for a Thrill," Johnny Mercer's "Skylark" and the aforementioned "For All We Know" remain some of her greatest performances from any era. Together, the two recordings should have made Franklin a star on the level that Streisand and Nancy Wilson were in the mid-1960s. Franklin, though, sounds tentative on Billie Holiday's "God Bless the Child"—perhaps not quite ready to fill those shoes.

Franklin was more than willing face up to the expectation already placed on her when she tackles a album length tribute to Dinah Washington in 1964; just as a young Washington, who died at the too young age of 39 in 1963, faced the daunting challenge of living up to the artistry of Holliday, and Natalie Cole would later face that same challenge in the 1970s standing in the musical shadow of Franklin. Washington once described a twelve-year-old Franklin, to her producer Quincy Jones, as the "next one." Franklin's relationship with Washington and her music was personal as she details in her memoir From These Roots (1999).

Though Franklin would later claim Clara Ward as her "greatest" influence (and deservedly so, when you hear Amazing Grace), Washington's influence is all over Franklin's recordings at Columbia prior to her recording of Unforgettable: A Tribute to Dinah Washington (1964). The ten songs that appear on Unforgettable were all chosen by Franklin and include signature Washington tunes such as "What A Difference a Day Makes" and "This Bitter Earth." As critic Michael Awkward writes in Soul Covers: Rhythm and Blues Remakes and the Struggle for Artistic Identity, "Franklin offers a riveting display of vocal power, a representation of rage whose source could very well be her inability to match or improve upon…her idol's performance." (60) Franklin literally finds her own voice on Unforgettable; the future was set in motion with this recording.

The Unforgettable sessions also produced the track "Lee Cross" written by Franklin's then husband and manager Ted White. "Lee Cross" was an inkling to Franklin's immediate future at Columbia, as the company sought to have her record music more fitting to the burgeoning Pop-Soul sound of Little Anthony and the Imperials and Dionne Warwick. Franklin's most popular release for Columbia, Runnin' Out of Fools, featured production by Clyde Otis, who produced Washington's later hits, and helped establish the career of balladeer Brook Benton ("Rainy Night in Georgia). Runnin' Out of Fools (1964) features Franklin interpreting the "turn-table' hits of the day including Brenda Holloway's "Every Little Bit Hurts," Dionne Warwick's "Walk On By" (she later covers "I Say A Little Prayer" for Atlantic), Benton's "It's Just a Matter of Time," Mary Well's "My Guy" (a clear misstep) and the title track.

In retrospect Runnin' Out of Fools, might have been, Franklin's most important Columbia album, not just because of its popularity, but because it hinted at how Franklin, began to imagine herself in a pop music world that was exploding in the midst of anti-Vietnam war demonstrations, the Civil Rights Movement and the death of Camelot. Clyde Otis seemed the perfect musical interlocutor for Franklin, as least from Columbia's standpoint, as he oversaw the bulk of Franklin's recording sessions until she left the label in 1966.

Though Runnin' Out of Fools and Yeah!!! (released originally with a canned audience) are the only studio albums that Otis produced while Franklin was still at the label, the Take a Look collection includes two full discs of Otis productions, Take a Look: The Clyde Otis Sessions and the unreleased master A Bit of Soul. Both discs are a revelation of the artistic mindset of an artist, who at that point, saw her success manifested in the Soul arena, instead of the Jazz, show tunes and pop balladry that Columbia unsuccessfully tried to fit her into.

Rather than release the album A Bit of Soul, Columbia chose to issue singles, the most famous of which is "One Step Ahead," which formed the basis of Mos Def's "Ms Fat Booty" thirty-five years later. During those sessions in late 1964, Franklin also recorded an early Ashford and Simpson composition, "Cry Like a Baby." The tracks from Take a Look: The Clyde Otis Sessions, represent a sort of middle ground—Streisand and Nancy Wilson are clearly in their sights—but it's the title track, "Take a Look," an Otis original , that stands out as the best tribute to Franklin's early career, with lyrics that echo the trouble in the street, while exhibiting Franklin's singular ability to "scream and cry" as Michael Awkward describes it.

The year before Clyde Otis was brought into the fold, Columbia paired Franklin with the maverick producer Bobby Scott, best known for the compositions "A Taste of Honey" (see Lizz Wright's recent treatment) and "He Ain't Heavy, He's My Brother." Marvin Gaye was a longtime fan of Scott and sought him out in the mid-1960s to develop charts for a Sinatra-styled album that Gaye wanted to record. Those sessions were eventually released after Gaye's death as the remarkable Vulnerable.

Just as remarkable are Tiny Sparrow: The Bobby Scott Sessions, where Franklin brilliantly interprets fare like "Here Today and Gone Tomorrow," "I Won't Cry Anymore," (which Gaye also recorded), "Looking Through a Tear," and the breathtaking "Tiny Sparrow." The production is lush and beautiful throughout, but it is not hard to imagine the suits at Columbia wondering aloud, what the audience was for the project. The bulk of the sessions sat in a can at Columbia until they resurfaced on the 2002 collection The Queen in Waiting.

With the recent news of Franklin's declining health, many critics have been trying to summon words to describe a career that has been peerless and indeed timeless. Take a Look: The Complete Aretha Franklin on Columbia allows Franklin's music to offer the best assessment of a career, that in many ways, is simply beyond words.

***

Mark Anthony Neal is Professor of African & African American Studies at Duke University and the author of five books of cultural criticism including the forthcoming Looking For Leroy: (Il)Legible Black Masculinities. Follow him on Twitter @NewBlackMan.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers