Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 737

May 3, 2015

What Does The SAT Really Test?..."Just how White you are?"

Some of us have known about the problems with standardized tests since

Michael Evans

(Ralph Carter) of Good Times fame told us this 30-years ago, but it's nice to hear it confirmed from other popular sources, like PBS Idea. That the SAT's creator

Carl Campbell Bingham

was once a eugenicist speaks volumes.

Some of us have known about the problems with standardized tests since

Michael Evans

(Ralph Carter) of Good Times fame told us this 30-years ago, but it's nice to hear it confirmed from other popular sources, like PBS Idea. That the SAT's creator

Carl Campbell Bingham

was once a eugenicist speaks volumes.

Published on May 03, 2015 08:28

May 2, 2015

Toni Morrison on Baltimore: "What astonishes me... is the obvious cowardice of the police"

"Nobel Prize-winning author

Toni Morrison

talks talks to

Charlie Rose

about the recent protests over the death of Freddie Gray in police custody in Baltimore, and about what can be done about the breakdown in trust between law enforcement and the community. "What astonishes me... is the obvious cowardice of the police" who are responsible for these deaths, she says."

"Nobel Prize-winning author

Toni Morrison

talks talks to

Charlie Rose

about the recent protests over the death of Freddie Gray in police custody in Baltimore, and about what can be done about the breakdown in trust between law enforcement and the community. "What astonishes me... is the obvious cowardice of the police" who are responsible for these deaths, she says."

Published on May 02, 2015 15:30

"Did You Change Your Mind?”: a Black Duke Student Responds to the “Noose” Apology

"Did You Change Your Mind?”: a Black Duke Student Responds to the “Noose” Apologyby Henry L. Washington, Jr. | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)May 1, 2015

"Did You Change Your Mind?”: a Black Duke Student Responds to the “Noose” Apologyby Henry L. Washington, Jr. | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)May 1, 2015Dear Duke Administrators,

The past semester has been excruciatingly difficult for myself, and many other black students on this campus. The macro-aggressive and micro-aggressive realities of racism and prejudice that characterize my daily experience as a student along with the countless national instances of violence against black bodies throughout the United States have left me wondering just how far our national racial politic has progressed. Systemic racism dictates that nooses are still being hung on the Bryan Center plaza in the year 2015, and that I must still march, rally, and protest simply to remind the world that my life and the lives of my peers matter.

As a result of yet another administrative disappointment, my thinking about Duke’s conclusions on the noose investigation over the course of today has been characterized by three distinct sentiments: furiousness, disdain for the timing, and dizziness.

When I initially read The Chronicle’s online headline, an update on the noose incident investigation which stated that the Duke administration had concluded that the hanging of the noose “was caused by a lack of cultural awareness and was not a statement related to racism,” I was furious. As I began to think about the particular historical context of lynching that frames the hanging of a noose, I was reminded that the significance of the act is the same regardless of the responsible student’s intentionality. Secondly, I began to think about the timing of this announcement and letter as incredibly poor, given what is happening in Baltimore as violence, racism, and systemic oppression burgeon local and national frustration with the current state of America’s sociopolitical structures around race.

Finally, as I continued to sit with and reflect on the responsible student’s letter and the university's announcement, I became dizzied. Several administrators have made promises to students that they would work to improve the culture of race relations on campus, citing their aversion to the “cowardly act of hatred--” the hanging of the noose. Thus, I was given the impression that administration identified with the anger and frustration of many students about the collective, problematic culture of race relations that is cultivated on Duke’s campus. President Brodhead, Provost Kornbluth, and Vice President Moneta, did you change your mind?

Did a student’s proclamation of their cultural incompetency serve to render what you had previously thought to be a cowardly act of hatred to be a simple lapse in judgement? Furthermore, does your promise to make Duke a more inclusive space for racial and ethnic minorities still hold true? Or does your concern focus, instead, on the potential damage yet another nationally publicized racial catastrophe could have on ‘our’ brand?

This administrative announcement and this astonishingly lax sanction for a student, whose apology letter clearly re-articulated his or her lack of understanding for the significance of the act, are three additional “slaps” in the faces of black students and their allies. I am profoundly disappointed in what appears to be the university’s decision to release an announcement declaring that racism was not involved in the hanging of the noose alongside such an ill-considered, audacious, and problematic “apology.”

With such a presentation, you may have delegitimized the claims of our outcries. It may appear that you have actually disregarded black students’ concerns. As it stands, you are setting a precedent that any act of racism or prejudice enacted against a minority student at Duke, no matter how serious, may be excused as long as that student’s supposed intention was rooted in a lack of proper judgement and not in racism. Do you wish to revoke the assessment that you brought forth in the past few weeks--that the current state of race relations at Duke is unacceptable?

Given the unequivocal responses released by other collegiate administrations in response to the racial aggressions they have addressed on their campuses, I urge you to reconsider the decision you have made on how to punish the actions of the student who hung the noose and how you choose to frame the noose hanging in archival history. As a community, we need you to decide that black lives matter, and to do so expeditiously, unreservedly, and permanently, for we still cannot breathe.

A tired, tired, black student,

Henry L. Washington, Jr.

Published on May 02, 2015 14:05

The Black Power Movement, #BlackLivesMatter & the Role of Black Women

In this preview of Left of Black at the Root.com, historian

Ashley D. Farmer

discusses renewed interest in the Black Power Movement, the movement's connections to #BlackLivesMatter and the role of Black Women in both. Dr. Farmer is the author of the forthcoming

What You've Got is a Revolution: Black Women's Movements for Black Power

(UNC Press)

In this preview of Left of Black at the Root.com, historian

Ashley D. Farmer

discusses renewed interest in the Black Power Movement, the movement's connections to #BlackLivesMatter and the role of Black Women in both. Dr. Farmer is the author of the forthcoming

What You've Got is a Revolution: Black Women's Movements for Black Power

(UNC Press)

Published on May 02, 2015 07:53

Baseball’s Warning Track: Blurred Lines and Bright Lights of Race by Wilfredo Gomez

Baseball’s Warning Track: Blurred Lines and Bright Lights of Race by Wilfredo Gomez | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Baseball’s Warning Track: Blurred Lines and Bright Lights of Race by Wilfredo Gomez | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)On the recent episode of Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel, HBO continued to mark the 20th anniversary of the show by showcasing the talents and skills of an all-star cast of comics. In this most recent episode, Bryant Gumbel introduced a segment narrated by comedian Chris Rock who offered a poignant, thought provoking social commentary on why blacks have abandoned baseball and why it matters. From the outset of the segment, Rock posits an interesting proposition: the disappearance of the Black baseball fan. It is apparent and somewhat obvious that blackness is a proxy for African-American identity. Towards this end, Rock offers an outline of his central argument, by deploying his trademark routine that fuses humor and comedic timing with social commentary. In so doing, Rock laments the loss of the African-American baseball player by noting the lack of figures such as Dwight Gooden, Darryl Strawberry, Mookie Wilson, and Kevin Mitchell. Rock makes use of these figures to talk about pastimes passed and the cultural and cognitive disconnect between the presence of African-American ballplayers and the cultural imagination of an American pastime that exists at the crossroads of a history that is inherently both black and white America.

This makes sense given the fraught and violent history that Rock signifies upon brilliantly. He does so multiple times over, evoking the following: Emmett Till, the Ferguson police department, Blake Sheldon, a photo of the Stillman College baseball team (an HBCU whose baseball team is largely “white” by Rock’s reading. I counted 8 ethnically ambiguous faces in the photo), Howard University, antique stadiums, Ruth, DiMaggio, a throwback baseball tournament (where everyone dressed up like it was the 1860s), suppressed slave rebellion(s), Franklin, Tennessee, the Carnation Plantation, and even state senators and corrections officers. Rock’s critical engagement of baseball and the lack of black bodies present in the sport afford both a context and subtext that situates and fleshes out a racial paradigm along black and white lines.

What I found particularly thought provoking about Rock’s segment was his tackling the issue of paying to play. That is to say, that Rock pointed out that some argue that baseball’s dwindling number of African-American participants is directly impacted by the exorbitant expenses incurred to participate in the sport effectively. To this Rock juxtaposes the Black experience with the experiences of youth in the Dominican Republic. While video footage of Dominican boys plays, the voice of Rock can be heard saying: “This is a tiny third-world island and it dominates baseball…and the only equipment they have are twigs for bats, diapers for gloves, and Haitians for bases.” Not to be forgotten here is the juxtaposition of the Haitian experience with that of the Dominican Republic when the bodies exposed by the video footage is that of black bodies.

While I do not think that Rock intended to offer a critique of blackness per se, his narration had the unintended consequence of raising the questions “who is black?” and “blackness for whom?” Upon viewing the footage shown to viewers, it is readily apparent that the youth playing baseball are phenotypically black. With this in mind, I ask myself, is it possible for black baseball fans to have their faith in the sport restored and/or reframed by supporting the black “others” who dominate the contemporary landscape of America’s pastime? Where do Afro-Latinos fit in this conversation?

It is in this context that I am trying to think through and challenge my own understanding of Afro-Latinidades and Latinidades vis-à-vis discourses of blackness and more importantly of diaspora(s). I am reminded of Tori Hunter’s comments circa 2010 when he noted that black Latino players in the major leagues were in fact “impostors.” When addressing a fellow ballplayer Hunter is reported to have said, “Hey, what color is Vladimir Guerrero? Is he a black player? I say come on, he’s Dominican, he’s not black…” Hunter later tried to revisit his controversial comments by noting that his word choice was inaccurate. He later alluded to cultural differences and roots in Latin America that ultimately point to a brotherhood on the field.

As I reflect on this comment within the context of Rock’s Real Sports segment, I am wrestling with this notion of presence, embodiment, performance, race, nationality, and authenticity. I raise this point in an attempt to critically interrogate the presence (or lack) of popular and public representations of Latinos/as more broadly. The vehicle used to tackle this topic is the sport of baseball, but the implications elsewhere are equally as thought provoking. With this in mind, I would like to pose a series of questions to my readers in the hopes that they spark a meaningful dialogue.

For instance, when thinking about the Puerto Rican community, what comes to mind first, the images of Jennifer Lopez and Ricky Martin or the images of Roberto Clemente and Arturo Schomburg? Do American public and American media outlets possess the kind of sensitivity, education, and wherewithal to differentiate a community that includes Dominicans, Venezuelans, Cubans, Peruvians, Hondurans, Guatemalans, Argentineans, Chileans, and Puerto Ricans, amongst other ethnic groups? Moreover, given the shift towards acknowledging, raising awareness, and self-identifying as Afro-Latino/a, what does it mean to be Afro-Latino/a? I say this acknowledging the fact that the visual is privileged in our understanding of race. What does it mean for those whose bodies may not be read as “black” to self-identify as black? Does the right to self-identification detract from the qualitative experience(s) of Latinos who happen to be Black Latinos/as? Do we celebrate and embrace black Latinidades the same way? Where do we locate the spaces for intervention regarding black diasporic bodies?

Years ago my friend and mentor James Braxton Peterson delivered a keynote address in which he offered a framework from which to understand notions he termed technical blackness and Technicolor blackness. Although his remarks were societal in scope, the terms of conversation are helpful in framing this discussion. They may also help explain the racial paradigm that Rock is operating under when making his comments. Through the idea of technical blackness, Peterson highlighted static notions of viewing identity and race. The latter, Technicolor blackness, offered a multi-dimensional and multi-purposeful deployment of language, its visible and not-so visible meanings to bring nuance and careful analysis to bear on the ways in which we characterize, define, and outline parameters of blackness and diasporic subjects. Such a language, of technical and Technicolor blackness, affords us a lens from which to situate gradations of color that transcend cultural and spatial boundaries, even language.

This language may prove helpful in reframing and reassessing Rock’s argument. In reinforcing his framework and by extension bringing attention to critical media literacies and the ways in which race may materialize in popular mediums, Peterson eloquently used the language of the Wu-Tang Clan and their song “C.R.E.A.M.” to revisit the gamut of blackness such that its manifestation included both, a Puerto Rican who doesn’t quite qualify as a “butta pecan Puerto Rican” (this writer-who was characterized as being more “French Vanilla”) and a colleague who was read as “chocolate deluxe.” In his text The Hip Hop Underground and African American Culture: Beneath the Surface, James Braxton Peterson engages the ideological dilemmas of racial authenticity by highlighting the following:

The crux of the problem, or system of problems, lies (at least partially) in the fact that American blackness is a fluid category. Moreover, the distinctive historical relationship between Black cultural production and American mainstream appropriation and commodification forces the discussion into a type of stasis that perpetuates the notion that the most oppressed Black people (the folk or vernacular culture) are already the most authentic black people. Literary, cultural studies scholars and social scientists from Dubois and Hurston, to Kwame Toure and Charles Hamilton, to Joyce Joyce, Houston Baker, Skip Gates, to Imani Perry, John L. Jackson, and Michael P. Jeffries are for the most part consistently insistent on the limitations of authenticity discourses and racial identity. In some ways definitions of authenticity in music/art are less convoluted than those definitions that attempt to arrive at some form of authentic blackness (35).

Given the kind of historical and contemporary backdrop of Rock’s comments it is noteworthy to highlight the deterioration of progress in race relations post-Obama. The experiences of black folks and blackness, be they experienced in Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, or Cuba is strikingly similar. Much like the news coverage surrounding the Protests and riots in Baltimore, the fact of blackness and its surveillance comes at the expense of its cheapening dismissal via the deployment of coded language that circulates in the media. This effectively masks the structural and institutional push and pull factors that diverge attention and accountability away from state-sanctioned violence and the overstepping of boundaries by police forces nationally. It is that which is black that is demonized and pathologized in the eyes of the popular imagination.

Globally, irrespective of cultural differences and migration, the fact of blackness remains, a proxy for that which is cool, but one that has been historically transformed into an extremely inequitable type of social contract which has lead to blacks having surrendered a greater portion of their freedoms as they have been relegated to second-class citizenship. As my brilliant colleague Odilia Rivera-Santos points out, when dealing with the police department, whether in Brooklyn, Puerto Rico, or Major League baseball, “people don’t see culture, they see race.” They also do not see class (socio-economic status). Look at how many times Rock himself has been pulled over while “driving while black.” Furthermore, it should be pointed out that what is missing from Rock’s piece is the obvious: distinctions having to do with race, ethnicity, or nationality is collapsed when folks arrive in America. The American racial paradigm is simple: either you are white or you are black. There is a premium placed on the physical and what we see. No amount of wealth and fame would preclude any of the athletes mentioned below from being the victim of discriminatory practices, prejudices, or behaviors. Basketball player Thabo Sefolosha found this out recently when encountering the New York Police Department after a night out with some teammates. Someone should remind Chris Rock of this.

I offer these vignettes, interlocutors, and arguments in an attempt to tackle Rock’s characterization and deployment of blackness (read as an African-American) alongside the blurred scripts of approximated blackness that somehow white-out the presence of Afro-Latinos. Reflecting on the most recent World Series, Rock states that the San Francisco Giants “won it all without any black guys on the team.” Thinking back to that World Series, the MVP was awarded to Pablo Sandoval, a Venezuelan. Are there any instances where Pablo Sandoval’s body may be read as black? This question is posed in lieu of Rock’s statistics suggesting that five out of six baseball viewers are white men in their 50s. Thinking through Peterson’s argument, is it possible that Pablo Sandoval could be technically black? Where and under what contexts might Sandoval’s body be read under the guise of Technicolor Blackness? Can the black fan that operates under the paradigm of technical blackness see through a Technicolor lens to celebrate the contributions of Afro-Latinos?

Revisiting the World Baseball Classic, we have players such as Jose Reyes and Fernando Rodney representing the Dominican Republic. Rodney is from Samana, Dominican Republic, known for its community of Dominicans who are of African-American descent, freed people who relocated beginning in 1824 to the Samana Peninsula in Hispanola. Players such Irving Falu and Hiram Burgos (who attended Bethune-Cookman, a historically black college/university) represented Puerto Rico. How do we view major leaguers such as Yasiel Puig and Yoenis Cespedes? What about former MVP and Triple Crown Winner Miguel Cabrera? It is possible that these figures think about their blackness and self-identify in ways that challenge America’s conceptualization of both blackness and whiteness.

As someone interested in popular culture more broadly I can’t help but think through how the issues raised by Chris Rock materialize(s) elsewhere. Is former Kentucky Center Karl-Anthony Towns Black, Afro-Latino, or both? Towns, a projected top two pick in the upcoming NBA Draft, played for the Dominican National Team, being born to an African-American father and a Dominican mother. What about music artists such as Miguel and Fashawn, who are both Mexican and African-American, or rap artists, AZ or Fabolous, who are Dominican and African-American? Curiously, where does their ability or inability to speak Spanish play into discourses of identity and authenticity? Would Romeo Santos, who recently wowed thousands of fans on the TODAY show, be read as black or Afro-Latino given his Puerto Rican and Dominican roots?

To conclude, I agree with Rock that baseball would benefit tremendously from more African-Americans participating in the sport. I also have to ask myself whether or not Rock’s comments are unique to baseball, given the significant participation of African-Americans in the NBA and the NFL. Maybe Rock has a point: Baseball may be an archaic or boring sport that lacks the luster of basketball or football. The February 13, 2015 article appearing in The Players’ Tribune penned by Pittsburgh Pirates center fielder and 2013 National League Most Valuable Player, Andrew McCutchen offers a different story. In his article “Left Out” McCutchen cites the financial costs associated with having exposure to baseball tournaments and travelling to be seen as barriers towards participation. Lack of exposure, low socio-economic status, and mentorship were factors that McCutchen highlights explaining why youths from the inner-city and working-classes might struggle to make it in the sport (Jose Bautista, in a response entitled “The Cycle” cites a lack of structured education, professional and language skills as barriers to Dominicans chasing their baseball dreams). Most importantly, he highlighted the ever-present nature of paying dues in the minor leagues and the institutional support mechanisms in place that allow baseball players in the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico to thrive, where those opportunities were not available to him as an African-American playing baseball.

While I myself am not a baseball aficionado (Ken Griffey, Jr. was my favorite player. His swing of the bat was something poetic to marvel at), baseball seems to lack a transcendent African-American star like the Lebron James, Kevin Durant, or Stephen Curry’s of the (NBA) world. If the death of baseball is eminent, its revival could lie in a shift from coverage through that which is technically black towards coverage that is more consistent with Technicolor blackness. Let us not forget the contributions of the Yasiel Puig’s alongside those of the Andrew McCutchen’s of the baseball world. Successfully doing so might remind us (and Chris Rock) that blacks have not abandoned baseball and that matters.

+++

Wilfredo Gomez is an independent researcher and scholar who can reached via Twitter at @BazookaGomez84 or via email at gomez.wilfredo@gmail.com. He is a contributor to NewBlackMan (in Exile).

Published on May 02, 2015 06:54

May 1, 2015

Genetic Ancestry Reveal with Mark Anthony Neal @ Duke--May 20, 2015

Published on May 01, 2015 19:49

"It (Still) Might Be Okay"--Cornel Westside Visuals Emerge from the Archive

Recorded almost a decade ago, timely visuals for Lupe Fiasco's "It Just Might Be Okay" have emerged. Directed by

Chris & Blaq

.

Recorded almost a decade ago, timely visuals for Lupe Fiasco's "It Just Might Be Okay" have emerged. Directed by

Chris & Blaq

.

Published on May 01, 2015 14:52

“Non-Violence as Compliance”: Interview with Fred Shuttlesworth by Charles Bane, Jr.

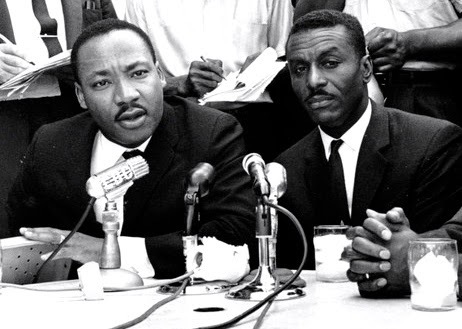

“Non-Violence as Compliance”: Interview with The Giantsby Charles Bane, Jr. | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

“Non-Violence as Compliance”: Interview with The Giantsby Charles Bane, Jr. | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)"Non-violence as compliance," writes Ta- Nehiisi Coates, attempting to challenge history in a country where the language of riots must be heard before it is too late. For like Freddie Gray, Emmet Till died because he made eye contact, and ran.

No period in the Civil Rights era of the 1960's produced more drama and violence, or drew more national attention than the campaign in Birmingham, Alabama. It was here that the movement met the full fury of the South. At the center of the firestorm was the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. One of the five original members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he was the unquestioned spiritual leader of the city's Black community. It was Shuttlesworth, fierce and uncompromising who then Attorney General Robert Kennedy phoned as Freedom Riders ( and Shutttlesworth) were being engulfed in a wave of mob violence. When Kennedy asked what he could do to help, Shuttlesworth barked " You can get the buses rolling!"

It was this determination that raised Shuttlesworth to the level of a legend among his peers in the Movement. This interview took place by phone. Two years later I met Reverend Shuttlesworth when he attended the opening of the Martin Luther King Memorial-- the largest of its kind in the South-- in West Palm Beach, Florida.

Charles Bane: When did you first arrive in Birmingham?

Shuttlesworth: I was raised there, from the age of three. I left for Mobile for work, really.I attended Cedar Grove Academy in Mobile, then left in 1947 to go to Selma University. I started pastoring in Selma in 1948 in a very rural church. I have a wife and three kids. I was happy, but I was always..studying. I had a great desire to achieve. I really went back to Birmingham to get a teacher's certificate; a Black man couldn't get that in Selma. I like to say that I left my church in Selma for a baptism of fire in Birmingham.

CB: Describe the city under Jim Crow.

Shuttlesworth: Birmingham was the closest thing to Johannesburg, South Africa. Something about this slowly evolved in me; there was no flash of fire. It was simply God's plan. Black people had no rights the white man was willing to respect. There was no organized crusade against segregation. It was my own personal struggle.A newspaper noted I was the only man to challenge Bull Connor and live.

CB: When did you first meet Dr. King?

Shuttlesworth: In 1954. He was invited to Birmingham to speak. Martin was so committed to non-violence that he didn't like to make anyone angry ( Pause). He hated to overrule his subordinates. To him, everybody was a somebody. There was no such thing as a nobody to Martin. (Quotes Dr. King) : " If a man is called to be a street sweeper, he should sweep streets even as Michelangelo painted or Beethoven composed music or Shakespeare wrote poetry. He should sweep streets so well that all the hosts of heaven and earth will pause to say, "Here lived a man who could sweep!' "

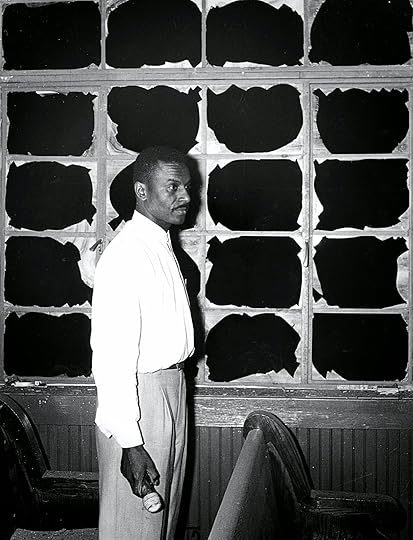

CB : What are your most vivid memories of the Birmingham campaign?

Shuttlesworth: It was a great struggle. My church was bombed twice. They jailed me over forty times, sometimes on "vagrancy" so I couldn't post bond. But it was ...glorious. Birmingham was the turning point. It was the turning point in our government's concern for its citizens.Everything good for the common folk came from Birmingham. We were really up against a system. If the police didn't stop you, the Klan would; and if that didn't stop you , the courts would. They were all one thing: the system. But scripture moved me so. Light shines in the darkness, so the darkness can't stop you.

CB: Would you describe what happened when you attempted to register your children in an all- white school?

Shuttlesworth: I knew it would be a difficult day. My associate at the church, James Fipher, dropped us right at the curb. He kept the car doors open, and it saved our lives. There was a mob of 15 or 16 people and three policemen just standing there.I was struck and they knocked me down.The first time I ever saw brass knuckles. Somebody threw a coat over me, and I heard them say, "Let's kill them!". Another said to me. " It's all over now." It all happened so fast. My wife started to move back, got a slight distance, and I didn't see a man stick a switchblade in her hip. We didn't know about it until we got to the hospital. My children stayed in the car; my wife pushed them to the floor. I was 25 or 30 feet from the car, being beaten with a bicycle chain. I was struggling back to the car a little bit more, each time I was hit. I was seeing stars, but I fell into the front seat. There's a photograph of the car taking off, with the doors still open.

CB: What would you say today to the mob that beat you?

Shuttlesworth: Come to dinner and we'll pray.

CB: When the Freedom Riders were attacked, did you confront the Attorney General of the United States?

Shuttlesworth: Uh-huh. Kennedy wanted to change their route and send them to Louisiana, to Baton Rouge. But those buses were going to Mississippi.

CB: Was Kennedy trying to manipulate you?

Shuttlesworth: Yes. But finally, he called Patterson ( John Patterson, Governor of Alabama, 1959-1963) and they went back and forth. But it was us that moved the buses: we told the bus company we had Black drivers, and they would not stand for it. That would have been the last straw. So all the buses carrying Freedom Riders had white drivers.

CB: The history books say your house was bombed.

Shuttlesworth: No, they bombed my church; but my house nearby was wood, and the bricks from the church shattered a whole side. My family was on the other side. I knew exactly what it was the minute it went off. But I have to say I never felt more comfortable. I was at peace."Underneath me are the everlasting arms." I felt God's presence and I knew I wouldn't get hurt.

CB: What were the major accomplishments of the Civil Rights Era?

Shuttlesworth: First, the Civil Rights Movement gave people hope.There was a feeling before that segregation couldn't be destroyed. To the white man, segregation was more important than going to heaven. Second, just the fact of a People rising up without arms, facing terrors, night and day. God was in this thing.

CB: Where were you when Dr. King was assassinated?

Shuttlesworth: I was in my church office, with the TV on. I went and told the choir. Everybody was crying. I had heard from Martin two days before: we were all going to meet on Monday about the Memphis thing. That speech that Martin gave: " I may not get there with you." All of us expected to get killed. My feeling was that he wasn't killed. He was simply taken up because he was doing God's work.

CB: Where do we go from here?

Shuttlesworth: There's no place to go but forward. There is the dream ahead of us of the destruction of racism. But you got to keep pushing.

Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth

. March 18, 1922 – October 5, 2011

Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth

. March 18, 1922 – October 5, 2011+++

Charles Bane, Jr. is an activist, essayist and current nominee as Poet Laureate of Florida.

Published on May 01, 2015 13:51

April 30, 2015

Trailer: What Happened, Miss Simone?

Trailer for

What Happened, Miss Simone?

(dir.

Liz Garbus

), which premieres on Netflix staring June 26th.

Trailer for

What Happened, Miss Simone?

(dir.

Liz Garbus

), which premieres on Netflix staring June 26th.

Published on April 30, 2015 08:55

Did Anybody Ask Them? America's Expendables Have Their Say by Mark Naison

Did Anybody Ask Them? America's Expendables Have Their Sayby Mark Naison | @McFiredogg | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Did Anybody Ask Them? America's Expendables Have Their Sayby Mark Naison | @McFiredogg | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Many people are upset with the unrest in Baltimore that followed the death of Freddie Gray in police custody. Fair enough. But if you spent time in the neighborhood he lived in, or in neighborhoods like it around the nation, you might still be upset, but you will not be surprised.

Abandoned houses. Vacant lots. Stray dogs. Rumors of mass displacement by the same people developing other parts of your city. No decent paying jobs anywhere. Police who patrol your community who do not live in it. Friends and relatives pushed out of the area by rising rents even though much of the housing in your neighborhood is decayed or vacant. Huge numbers of people rendered unemployable by felony convictions.

It is a toxic mix. And the policies that are made to address it are made by people far far away, Who never include your voice.

So I raise the question. Did anybody ask the poor people of Baltimore when:

...their neighborhood schools were closed and they were given charter schools and test after test?

...the State decided to wage the drug war in their community in a manner which would never be done at Johns Hopkins University, which has as many drugs on campus as any "hood" in Baltimore?

… they were encouraged to take subprime mortgages on the homes in their neighborhood and foreclosed on them en masse when the financial crisis hit?

…when their experience and music were appropriated and used it for entertainment?

You know the answer. No one ever asks them anything.

They are America's Expendables, whose suffering keeps our thriving prison industrial complex alive, and whose cries of pain are the material for popular music narratives, or hit tv series, that people around the world turn to for pleasure or inspiration.

They have a lot to be angry about. Will you finally hear their voices? Will you finally ask them what they want and what they need?

+++

Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies and History at Fordham University and Director of Fordham’s Urban Studies Program. He is the author of two books, Communists in Harlem During the Depression and White Boy: A Memoir. Naison is also co-director of the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). Research from the BAAHP will be published in a forthcoming collection of oral histories Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life From the 1930’s to the 1960’s.

Published on April 30, 2015 07:56

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.