Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 738

April 29, 2015

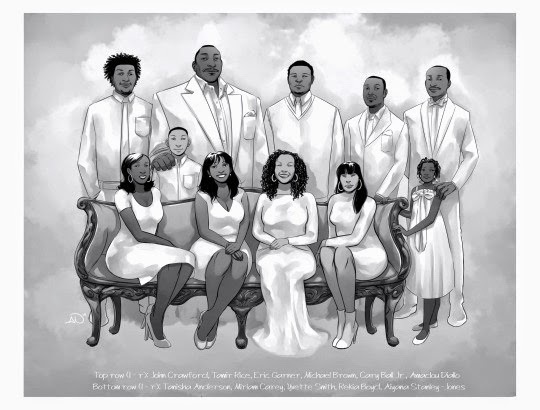

Illustrator Ashley A. Woods Honors Victims of Police Violence

As part of the forthcoming

APB: Artists against Police Brutality

, a tribute to the Black Fallen from illustrator

Ashley A. Woods

.

As part of the forthcoming

APB: Artists against Police Brutality

, a tribute to the Black Fallen from illustrator

Ashley A. Woods

.

Published on April 29, 2015 21:17

You're Nobody 'Till Somebody Kills You: Baltimore, Freddie Gray and the Problem of History

You're Nobody 'Till Somebody Kills You: Baltimore, Freddie Gray and the Problem of Historyby Yohuru Williams | @YohuruWilliams | HuffPost Black Voices

As residents of Maryland and the nation brace for what could potentially be another night of civil unrest in Baltimore, it is important to pause and reflect on what has brought us to the current moment. It would be easy to attribute the violence now taking place in the nation's 20th largest city to external factors including the rash of police killings that sparked the national Black Lives Matter campaigns. These grass roots efforts demand greater accountability and oversight of the police. One could also locate the roots of the unrest deep in the tangles of both Baltimore and the nation's troubled history with race and policing. Both have merits.

Long before video surfaced of a battered Freddie Gray being hoisted into a police van, students working on an African American history project at the Maryland historical society were uncovering one of the forgotten turning points of Baltimore's history, also coalescing around race and policing nearly three quarters of a century ago.

On February 1, 1942, a Baltimore police officer named Edward Bender killed an African American serviceman named Thomas Broadus in an incident of police brutality. Broadus's death mobilized the city's Black community. According to published accounts, the altercation began after Bender stopped Broadus and three companions for trying to hail an unlicensed taxi. The incident turned violent after Broadus insisted he was free to spend his money in whatever way he chose. Angered, Bender seized him and began beating him with his nightstick. When Broadus managed to break free, the crowd that gathered at the scene pressed him to flee. Although injured, Broadus attempted to stagger from the scene but not before Bender took careful aim and shot him in the back. He then proceeded to where Broadus was trying to take cover under a parked car and shot him in the back a second time.

To the horror of witnesses, he then began kicking Broadus and threatened to shoot several bystanders who volunteered to transport the wounded solider to the hospital. Broadus died later that night. Bender, who was also responsible for the killing of another black man, was initially charged with murder by a grand jury. However when they reconvened after a several day recess, they changed their vote and Bender was never prosecuted.

Angered by the killing, and after more than a month of organizing, on April 24 some 2,000 black protesters made their way to the state capital at Annapolis to demand an immediate end to segregation and police brutality in Baltimore. After the demonstration and meetings with Black leaders, Governor Herbert R. O'Conor assigned a Commission on Problems Affecting the Negro Population and ushered in a series of modest changes including the hiring of three uniformed black patrolmen. O'Conor's plodding pace however caused one black leader to warn of the possibility that, "a serious racial conflict may result unless some remedial steps are taken."Another complained, "Our people are being taught that policemen do not move among to protect them and uphold the law, and to say the least, it is producing a damning psychology which in the end must lead to disaster."

It is a familiar forecast to what we have witnessed over the past year in communities from Ferguson, Missouri to Staten Island, New York where the killing of unarmed men of color has garnered national attention, but not necessarily national action. Now as broadcast images of rock-throwing looters clashing with police and setting fire to cars threatens to displace the discussion of police violence, we have an even greater responsibility to be mindful of the past and the unfulfilled promises of justice that haunt the pages of history and silently condemn the indifference of the present. In this sense, Freddie Gray is no more unique than a half century of victims, like Thomas Broadus, whose names are now attached to violent urban uprisings. They mock us from the pages of history divorced from the social, political, and economic conditions that fed the social unrest to which their names are now attached. The faces and locations change but the agents of the killing or beating in each case have not. By ignoring that history we also ignore our collective responsibility to address the persistent problem of police brutality on persons of color.

When I was a graduate student at Howard University in the 1990s, I often visited the U street corridor where remnants of the 1968 Washington, D.C. riot remained nearly three decades later. Baltimore will bear similar scars and, despite optimistic and triumphant talk of rebuilding, in a city where poverty and joblessness are rampant, residents are justified to scratch their heads about what is there left to rebuild.

Amidst all the talk of economic recovery it is important to note that those gains have not been general and that cities like Baltimore, Cleveland, and Detroit that were once thriving urban centers have become heavily policed islands of despair.

In this context, it perhaps understandable why Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake chose to restrain law enforcement rather than unleash the devastating force of police in riot gear on residents. By the same token, the smoldering ruins of a city already in great physical and financial distress point to the limitations of electoral power. A Black mayor or a Black police chief, even a Black president for that matter are not sufficient to meet the needs of those, in the words of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, "smothering in an airtight cage of poverty."

Lecturing the disaffected on their moral responsibility to be non-violent loses its power when they are constantly confronted with images of men and women of color in their own city and in the nation as a whole subject to brutal treatment at the hands of law enforcement on YouTube, social media and the nightly news.

In the 1960s, politicians worried about the prospects of "long hot summers" where riots erupted episodically. In the age of social media, however, Baltimore may prove to have more in common with the Arab Spring. Perhaps, Freddie Gray may be the harbinger of a much-needed non-violent social revolution that once again privileges human life and democratic values over wanton police brutality dressed up as law and order.

Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee Chairman Stokely Carmichael spelled it out in an editorial in the New York Review of Books in 1966. Commenting on the rash of race riots then sweeping the nation he forcefully observed:

"In a sense, I blame ourselves--together with the mass media--for what has happened in Watts, Harlem, Chicago, Cleveland, Omaha. Each time the people in those cities saw Martin Luther King get slapped, they became angry; when they saw four little black girls bombed to death, they were angrier; and when nothing happened, they were steaming. We had nothing to offer that they could see, except to go out and be beaten again. We helped to build their frustration."

The same can be said for the contemporary scene. For more than two years, much longer for those who have been paying close attention, officially sanctioned violence against black and brown bodies has weaved through a procession of names like Oscar Grant, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner and now Freddie Gray whose lives mattered. The erasure from public discourse of their very humanity in the legalese of official responsibility and the racially coded terminology of urban crime was certainly a contributing factor in Baltimore where other ambiguous lives have responded in the language of despair, urban unrest.

In his "Letter from a Birmingham Jail," the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King noted what he described as the psychologically debilitating condition of "nobodiness" that induced racial resentment among people of color against white Americans. The kind of nobodiness that forces people to resort to social media campaigns that cry out what should be obvious, Black lives matter, human life matters, democracy matters, social justice matters.

I abhor violence in all of its forms. I also agree that the rioting will solve little. But, I also understand that when you are dealing with peoples whose experience is filtered through a constant struggle for recognition out of a degenerating sense of "nobodiness," the turn to rock throwing and looting is easier. Even if temporarily, it compels the world to confront the profound misery and pain that is the centerpiece of life for far too many Americans living on the margins.

It has become trite for some to seek solace for their indifference by writing such occurrences as police shootings and riots off as part of some imagined ineluctable cycle of history. We should, nevertheless be clear. History does not repeat itself nor does it rhyme. What it does is reflect. And what it displays in the current crisis is the jagged edges of a broken mirror reflecting back at us the distorted images of poverty, policing, and race, through the deeply wounding translucent shards of opportunity loss.

The deepest cut is the fact that we have failed to substantively address the issues of race and inequality that produce such moments in our history. We also have to be far more honest in acknowledging that they are not really moments at all, but part of a larger problem that eats away at the fabric of our society like a chronic disease. Our remedies thus far only treat the symptoms allowing the life-stealing cancer to run malignant. As politicians and pundits search for meaning in the aftermath of the unrest in Baltimore, the flames of anger and discontent will continue to burn in the hearts and minds of millions of Americans who feel that they have no vested stake in the society in which they live and intensely fear. For in one unfortunate encounter with the wrong officer that they may traverse the ignominious existence of nobodiness to the infamy of another Eric Garner, Tamir Rice or Freddie Gray -- another nobody killed in the custody of police.

+++

Dr. Yohuru Williams is Associate Vice President for Academic Affairs and Professor of History at Fairfield University. He is the author of Teaching US History Beyond the Textbook (2008) and Black Politics/White Power: Civil Rights, Black Power and Black Panthers in New Haven (2008) and co-editor of In Search of the Black Panther Party (2006) and Liberated Territory: Toward A Local History of the Black Panther Party (2009).

As residents of Maryland and the nation brace for what could potentially be another night of civil unrest in Baltimore, it is important to pause and reflect on what has brought us to the current moment. It would be easy to attribute the violence now taking place in the nation's 20th largest city to external factors including the rash of police killings that sparked the national Black Lives Matter campaigns. These grass roots efforts demand greater accountability and oversight of the police. One could also locate the roots of the unrest deep in the tangles of both Baltimore and the nation's troubled history with race and policing. Both have merits.

Long before video surfaced of a battered Freddie Gray being hoisted into a police van, students working on an African American history project at the Maryland historical society were uncovering one of the forgotten turning points of Baltimore's history, also coalescing around race and policing nearly three quarters of a century ago.

On February 1, 1942, a Baltimore police officer named Edward Bender killed an African American serviceman named Thomas Broadus in an incident of police brutality. Broadus's death mobilized the city's Black community. According to published accounts, the altercation began after Bender stopped Broadus and three companions for trying to hail an unlicensed taxi. The incident turned violent after Broadus insisted he was free to spend his money in whatever way he chose. Angered, Bender seized him and began beating him with his nightstick. When Broadus managed to break free, the crowd that gathered at the scene pressed him to flee. Although injured, Broadus attempted to stagger from the scene but not before Bender took careful aim and shot him in the back. He then proceeded to where Broadus was trying to take cover under a parked car and shot him in the back a second time.

To the horror of witnesses, he then began kicking Broadus and threatened to shoot several bystanders who volunteered to transport the wounded solider to the hospital. Broadus died later that night. Bender, who was also responsible for the killing of another black man, was initially charged with murder by a grand jury. However when they reconvened after a several day recess, they changed their vote and Bender was never prosecuted.

Angered by the killing, and after more than a month of organizing, on April 24 some 2,000 black protesters made their way to the state capital at Annapolis to demand an immediate end to segregation and police brutality in Baltimore. After the demonstration and meetings with Black leaders, Governor Herbert R. O'Conor assigned a Commission on Problems Affecting the Negro Population and ushered in a series of modest changes including the hiring of three uniformed black patrolmen. O'Conor's plodding pace however caused one black leader to warn of the possibility that, "a serious racial conflict may result unless some remedial steps are taken."Another complained, "Our people are being taught that policemen do not move among to protect them and uphold the law, and to say the least, it is producing a damning psychology which in the end must lead to disaster."

It is a familiar forecast to what we have witnessed over the past year in communities from Ferguson, Missouri to Staten Island, New York where the killing of unarmed men of color has garnered national attention, but not necessarily national action. Now as broadcast images of rock-throwing looters clashing with police and setting fire to cars threatens to displace the discussion of police violence, we have an even greater responsibility to be mindful of the past and the unfulfilled promises of justice that haunt the pages of history and silently condemn the indifference of the present. In this sense, Freddie Gray is no more unique than a half century of victims, like Thomas Broadus, whose names are now attached to violent urban uprisings. They mock us from the pages of history divorced from the social, political, and economic conditions that fed the social unrest to which their names are now attached. The faces and locations change but the agents of the killing or beating in each case have not. By ignoring that history we also ignore our collective responsibility to address the persistent problem of police brutality on persons of color.

When I was a graduate student at Howard University in the 1990s, I often visited the U street corridor where remnants of the 1968 Washington, D.C. riot remained nearly three decades later. Baltimore will bear similar scars and, despite optimistic and triumphant talk of rebuilding, in a city where poverty and joblessness are rampant, residents are justified to scratch their heads about what is there left to rebuild.

Amidst all the talk of economic recovery it is important to note that those gains have not been general and that cities like Baltimore, Cleveland, and Detroit that were once thriving urban centers have become heavily policed islands of despair.

In this context, it perhaps understandable why Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake chose to restrain law enforcement rather than unleash the devastating force of police in riot gear on residents. By the same token, the smoldering ruins of a city already in great physical and financial distress point to the limitations of electoral power. A Black mayor or a Black police chief, even a Black president for that matter are not sufficient to meet the needs of those, in the words of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, "smothering in an airtight cage of poverty."

Lecturing the disaffected on their moral responsibility to be non-violent loses its power when they are constantly confronted with images of men and women of color in their own city and in the nation as a whole subject to brutal treatment at the hands of law enforcement on YouTube, social media and the nightly news.

In the 1960s, politicians worried about the prospects of "long hot summers" where riots erupted episodically. In the age of social media, however, Baltimore may prove to have more in common with the Arab Spring. Perhaps, Freddie Gray may be the harbinger of a much-needed non-violent social revolution that once again privileges human life and democratic values over wanton police brutality dressed up as law and order.

Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee Chairman Stokely Carmichael spelled it out in an editorial in the New York Review of Books in 1966. Commenting on the rash of race riots then sweeping the nation he forcefully observed:

"In a sense, I blame ourselves--together with the mass media--for what has happened in Watts, Harlem, Chicago, Cleveland, Omaha. Each time the people in those cities saw Martin Luther King get slapped, they became angry; when they saw four little black girls bombed to death, they were angrier; and when nothing happened, they were steaming. We had nothing to offer that they could see, except to go out and be beaten again. We helped to build their frustration."

The same can be said for the contemporary scene. For more than two years, much longer for those who have been paying close attention, officially sanctioned violence against black and brown bodies has weaved through a procession of names like Oscar Grant, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner and now Freddie Gray whose lives mattered. The erasure from public discourse of their very humanity in the legalese of official responsibility and the racially coded terminology of urban crime was certainly a contributing factor in Baltimore where other ambiguous lives have responded in the language of despair, urban unrest.

In his "Letter from a Birmingham Jail," the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King noted what he described as the psychologically debilitating condition of "nobodiness" that induced racial resentment among people of color against white Americans. The kind of nobodiness that forces people to resort to social media campaigns that cry out what should be obvious, Black lives matter, human life matters, democracy matters, social justice matters.

I abhor violence in all of its forms. I also agree that the rioting will solve little. But, I also understand that when you are dealing with peoples whose experience is filtered through a constant struggle for recognition out of a degenerating sense of "nobodiness," the turn to rock throwing and looting is easier. Even if temporarily, it compels the world to confront the profound misery and pain that is the centerpiece of life for far too many Americans living on the margins.

It has become trite for some to seek solace for their indifference by writing such occurrences as police shootings and riots off as part of some imagined ineluctable cycle of history. We should, nevertheless be clear. History does not repeat itself nor does it rhyme. What it does is reflect. And what it displays in the current crisis is the jagged edges of a broken mirror reflecting back at us the distorted images of poverty, policing, and race, through the deeply wounding translucent shards of opportunity loss.

The deepest cut is the fact that we have failed to substantively address the issues of race and inequality that produce such moments in our history. We also have to be far more honest in acknowledging that they are not really moments at all, but part of a larger problem that eats away at the fabric of our society like a chronic disease. Our remedies thus far only treat the symptoms allowing the life-stealing cancer to run malignant. As politicians and pundits search for meaning in the aftermath of the unrest in Baltimore, the flames of anger and discontent will continue to burn in the hearts and minds of millions of Americans who feel that they have no vested stake in the society in which they live and intensely fear. For in one unfortunate encounter with the wrong officer that they may traverse the ignominious existence of nobodiness to the infamy of another Eric Garner, Tamir Rice or Freddie Gray -- another nobody killed in the custody of police.

+++

Dr. Yohuru Williams is Associate Vice President for Academic Affairs and Professor of History at Fairfield University. He is the author of Teaching US History Beyond the Textbook (2008) and Black Politics/White Power: Civil Rights, Black Power and Black Panthers in New Haven (2008) and co-editor of In Search of the Black Panther Party (2006) and Liberated Territory: Toward A Local History of the Black Panther Party (2009).

Published on April 29, 2015 20:41

America's Real State of Emergency: Baltimore and Beyond

Matt Rourke/The Associated PressAmerica's Real State of Emergency: Baltimore and Beyondby Heather Ann Thompson | @hthompsn | HuffPost Politics

Matt Rourke/The Associated PressAmerica's Real State of Emergency: Baltimore and Beyondby Heather Ann Thompson | @hthompsn | HuffPost PoliticsAs most Americans were sitting down to dinner Monday night, Maryland's Governor Larry Hogan was declaring a state of emergency in the city of Baltimore. Baltimore was burning, he explained, and nothing short of calling out the National Guard could now bring calm to Charm City. Mere minutes later, CNN, NPR and myriad other media outlets were reporting on the chaos. No matter how many mea culpas the Baltimore Police Department had offered, and no matter what assurances it had given that a thorough investigation into the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray would be conducted, city residents couldn't be calmed.

And yet, can state officials or the media really be surprised that promises of an internal investigation don't appease? Have they forgotten that citizens have directed their attention again and again to the crisis of police misconduct and abuse without remedy? Can they not remember the myriad instances of police violence against ordinary citizens that even they have acknowledged when they paid out millions of dollars in restitution to the victims? Indeed, as the Baltimore Sun reported just seven months ago, complete with graphic photographs of seriously injured citizens from that city, city officials have paid out over $5.7 million dollars to such victims since 2011. And, it turns out, they got off cheap. The state of Maryland has a cap on what it could be forced to pay out of a mere $200,000 per incident.

Even if state officials can't really grasp why Baltimore is burning today, they would do well to take a bit of a step backward and consider why their city burned before -- back in 1968. They might discover, albeit with some surprise, that then, like now, black residents erupted only because they were bone-sick of hearing news that yet another black man had been killed in America. They might see that the true state of emergency now, like then, isn't rage or even rock throwing. It is the racial profiling and racial brutality of the police.

Indeed, this state of emergency -- the true state of emergency -- has a very long national history. Back in 1967, for example, when Detroit was in flames and its black citizenry also took to the streets in rage and despair, Michigan's Governor George Romney also declared a state of emergency. He also called in the National Guard. And, most importantly, he also misunderstood the true state of emergency that his city faced.

Then, like now, the real emergency wasn't the smashing glass nor the fires. That would all end soon enough.

The real crisis that Romney faced -- indeed the real state of emergency facing his constituents -- was the fact that the Detroit Police Department had been abusing black citizens without censure for decades. The real state of emergency was that black lives didn't matter enough in Detroit.

And this is the real crisis that Governor Larry Hogan and every other American governor now faces as well. America's real state of emergency is that black citizens keep getting wounded, maimed and killed by members of law enforcement. These are real women like Rekia Boyd andAmerica's real state of emergency remains that black lives still don't matter enough in cities across America.

+++

Dr. Heather Ann Thompson is a native Detroiter and historian at Temple University who has written numerous popular as well as scholarly articles on the history of mass incarceration as well as its current impact. She recently completed Blood in the Water: the Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 for Pantheon books and the author of Whose Detroit: Politics, Labor and Race in a Modern American City. In 2015 Thompson joins the faculty at the University of Michigan.

Published on April 29, 2015 11:33

April 28, 2015

Left of Black S5:E28: Black Rage in the Age of Color-Blind Racism

Left of Black S5:E28: Black Rage in the Age of Color-Blind Racism

Left of Black S5:E28: Black Rage in the Age of Color-Blind RacismLeft of Black host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) is joined in-studio by Duke University Sociologist Professor Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, who is the author of the classic Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America (4th Edition).

Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University and in conjunction with the Center for Arts, Digital Culture & Entrepreneurship (CADCE).*** Episodes of Left of Black are also available for free download in @ iTunes U*** Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlack

Published on April 28, 2015 18:36

Not Looters, Liberators: Baltimore Rebels by Lamont Lilly

Credit Stefanie Mavronis Not Looters, Liberators: Baltimore Rebelsby Lamont Lilly | @LamontLilly | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Credit Stefanie Mavronis Not Looters, Liberators: Baltimore Rebelsby Lamont Lilly | @LamontLilly | NewBlackMan (in Exile)We could smell the tear gas a mile away. Thick clouds of burning smoke spread city-wide. The police, the tanks, the helicopters, all present and fully armored. From the moment I stepped off the train, you could feel the resistance in the air. At approximately 5pm, it was straight from the station to the streets, live.

When you take your time and walk by foot, the intense degree of poverty will completely paralyze you. It shocked me, and I’m from the hood. The absurd amount of boarded homes is absolutely ridiculous. The makeshift neighborhoods comprised of trash and forgotten debris – the countless number of dilapidated buildings, an absolute travesty. The lack of grocery stores, playgrounds and recreation facilities. The community’s once beloved primary school that was recently closed last year. The wasting away of Black bodies, good people and buried hope. The emphasis of protecting property over suffering people. While Freddie Gray was laid to rest today, these are the images that still remain.

For those who aren’t poor or never have been, tonight is April 27th (the end of the month), which for many people means that food stamps and EBT have run out. At least tonight, poor folk can eat well. Thankfully, the rice and pork chops were sponsored by the people, their courage and the Baltimore Rebellion.

For those who were glued to the corporate media (as in CNN, FOX News and CBS) unfortunately, you were force fed a pallet of lies, stereotypes and propped up images – a ruling class narrative that intentionally did not capture the spirit of strength, unity, resistance and perseverance. Truth is, we didn’t see any hoodlums and thugs tonight. We didn’t see any thieves, looters, nor rioters. All we saw was liberators – parents, workers and youth who heroically chose to liberate the bare necessities denied to them for months, years and several decades now.

So what people were taking some goddamn medicine! Pharmaceutical companies are making billions off the poor and could care less about them. Yes, poor people were taking pampers and toilet tissue, tube socks and boxes of cereal; these are the basic needs they’ve been denied. I don’t blame them for taking fresh food, new shoes, clothing and water. These are the basic needs capitalism refuses to provide.

After needs, there were also wants and desires that were met. Contrary to popular belief, poor people like televisions too, just like the rich folk do. Think about it, home appliances and laptops surround you every day, yet you have no means to acquire any of these things. You see them on billboards and watch them advertised on commercials, but you, no! You get nothing. So when human need is denied by brick walls, two-inch glass windows and security cameras, do excuse me, but something will have to give; and I can you assure it will not be the oppressed!

What people saw tonight on their Channel 6 News were the youth and families capitalism, U.S. greed and elected officials have thrown away. You can’t deny jobs, justice and self-respect and not expect rebellion. The Black masses are burning tonight because Amerikkka has burned them – excuse me, has burned “us” for centuries now.

This is bigger than Freddie Gray, Walter Scott and Rekia Boyd – much bigger than Baltimore and Ferguson put together. This is the underclass reclaiming their human existence from a country that denies them the right to breathe, the right to live without police occupation living on their front door step. We weren’t thugs and hoodlums tonight; none us were. We were tired of being tired.

The oppressed have spoken in their own language, loud and clear tonight. The question is who will hear us and join the fight?

+++

Lamont Lilly is a contributing editor with the Triangle Free Press and frequent contributor to Truthout, Dissident Voice, The Durham News, and Black Youth Project. He is currently serving as a visiting organizer with the Baltimore Branch of Workers World Party.

Published on April 28, 2015 12:49

The Violence of Gentrification by Mark Naison

The Violence of Gentrificationby Mark Naison | @McFireDogg | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

The Violence of Gentrificationby Mark Naison | @McFireDogg | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Last night, at a dinner where my wife was being honored for her educational leadership and anti-testing activism, I ran into an old friend, Tom Kappner, who for forty years has been a tenant activist on the Upper West Side. I asked him how the battle against Columbia expansion was going, and after saying "Not good," he shared me a horror story about events that were occurring in the heavily Dominican neighborhood that runs from Amsterdam Avenue to Riverside Drive between 135th and 155th Streets which has suddenly become valuable terrain.

Tom had just come from a meeting with the local City Councilman and several community leaders who had stories from more than 400 Dominican families who were being harassed by their landlords to drive them out of their apartments. This was being done because huge profits could be made from raising rents for new arrivals or turning the buildings into co-ops.

As Tom told me this, I thought of the events in Baltimore, and in Ferguson, and in many parts of Brooklyn, and was reminded that "Gentrification," often described as the impersonal operation of markets, can get very personal, and in its own way, quite violent.

How many tenants and homeowners and storekeepers leave communities where they have been fixtures for decades, sometimes generations, because they have been harassed by landlords and/or banks? If what is going on in West Harlem now is any indication, more than a few.

We need to factor this in as we try to understand the rage that many people feel about police practices, and in more recent times, police killings. The police are bearing the brunt of an anger felt at a whole array of forces that are driving poor and working class people out of communities they once felt at home, or making them feel as if they are an unwanted presence

When harassment comes from every direction, and you feel that no one cares and no one will come to your defense, it breeds desperation and rage as well as resignation.

Either we address the underlying causes of this distress, which go far beyond resentment of police, or we will reap the whirlwind.

And not only in Baltimore.

+++

Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies and History at Fordham University and Director of Fordham’s Urban Studies Program. He is the author of two books, Communists in Harlem During the Depression and White Boy: A Memoir. Naison is also co-director of the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). Research from the BAAHP will be published in a forthcoming collection of oral histories Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life From the 1930’s to the 1960’s.

Published on April 28, 2015 09:05

April 27, 2015

From Emmett Till to Trayvon…We Have Been Here Before and We Still Can’t Breathe

From Emmett Till to Trayvon… We Have Been Here Before and We Still Can’t Breathe

From Emmett Till to Trayvon… We Have Been Here Before and We Still Can’t Breathe(Interview with Chasen Hampton on His New Single “I Can’t Breathe”)

by Gloria Y.A. Ayee | @GloriaYAyee | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

“I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe…” These are the final words uttered by Eric Garner, a 43 year-old African American man, as he was being arrested and wrestled to the ground in a chokehold by a New York Police Department (NYPD) officer. Garner’s death is one in a long, troubling history of abuse of power, police brutality, and violence against Blacks in the United States.

“I Can’t Breathe,” a powerful Hip-Hop anthem by Chasen Hampton (featuring REKS, Dutch ReBelle, and Antagon1st), which was released in March 2015, addresses the pain of a society that can no longer breathe, literally and figuratively speaking, as countless lives continue to be lost through senseless violence and brutality. In an exclusive interview for NewBlackMan (In Exile), Hampton spoke about the process of writing “I Can’t Breathe.”

Hampton says that he wanted to express his frustrations with what he viewed as race baiting from media outlets in their coverage of stories about protests and rioting in response to police brutality and violence against Blacks. “I was fed-up and disgusted,” he says. Hampton realized that he could no longer remain silent, and he needed to take a public stand.

Hampton is an American actor and musician, who began his career as a Mouseketeer on The All-New Mickey Mouse Club, and later went on to become a member of the pop band, The Party. After a recent move to Boston, Hampton became heavily involved in the local Hip-Hop scene there. Hampton, who has always played it safe with his music, describes himself as someone who is not “one to rock the boat.” He generally stays away from making political statements, but has been deeply moved and disturbed by media misrepresentations, and a general absence of healthy dialogue on race issues in the country as a whole.

Hampton views “I Can’t Breathe” as a way to stand up for the truth. The American Antagon1st produced track features backpacking rapper REKS and Haitian-born Dutch ReBelle. Each artist wrote and recorded their verses on the track separately, allowing them to provide social commentary from their own unique perspectives. REKS and Dutch ReBelle both display lyrical prowess on their individual verses and Hampton’s strong vocals are a standout on the track, serving as a haunting reminder of the lives that have been lost. “No more. Enough is enough, it’s time to make a change,” Hampton sings.

Hampton, who is of Cherokee and Sac-Fox Native American descent, understands the troubling history of race relations in the United States, and knows that he has a unique platform through which he can speak out about injustice. He argues that in order for our country to move forward, no one should turn a blind eye when there are people crying out that they cannot breathe and asking that society as a whole acknowledge that Black lives matter.

+++

Gloria Ayee is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political Science at Duke University. She is also a freelance entertainment journalist and has contributed to The Root and Billboard.com.

Published on April 27, 2015 21:11

April 26, 2015

#TheSpin: Playing Cop for a Day and The Acquittal of Rekia Boyd's Killer

In this episode of

#TheSpin

with Esther Armah, guests

Shani Jamila

, Professor Anthea Butler and

Imani Uzuri

talk about citizens who pay to "play cop," the acquittal of

Rekia Boyd's

killer, and the rise of Xenophobia in South Africa.

In this episode of

#TheSpin

with Esther Armah, guests

Shani Jamila

, Professor Anthea Butler and

Imani Uzuri

talk about citizens who pay to "play cop," the acquittal of

Rekia Boyd's

killer, and the rise of Xenophobia in South Africa.

Published on April 26, 2015 07:54

April 24, 2015

Will Police Killings of Blacks be the Defining Crisis of the Obama Presidency?

Duke University University Sociologist

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva

, author of the classic Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America (now in its 4th edition) and

Left of Black

host Mark Anthony Neal discuss #BlackLivesMatters and the Obama Presidency.

Duke University University Sociologist

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva

, author of the classic Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America (now in its 4th edition) and

Left of Black

host Mark Anthony Neal discuss #BlackLivesMatters and the Obama Presidency.

Published on April 24, 2015 03:15

Will Police Shootings of Blacks be the Defining Crisis of the Obama Presidency?

Duke University University Sociologist

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva

, author of the classic Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America (now in its 4th edition) and

Left of Black

host Mark Anthony Neal discuss #BlackLivesMatters and the Obama Presidency.

Duke University University Sociologist

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva

, author of the classic Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America (now in its 4th edition) and

Left of Black

host Mark Anthony Neal discuss #BlackLivesMatters and the Obama Presidency.

Published on April 24, 2015 03:15

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.