Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1073

July 8, 2011

20 Years in 27 Days: A Marriage in Music | Day #7: Quincy Jones feat. James Ingram—"One Hundred Ways"

20 Years in 27 Days: A Marriage in Music Day #7: Quincy Jones feat James Ingram—"One Hundred Ways"by Mark Anthony Neal

The funny thing about falling in love, even from the perspective of a 16-year-old, is that music that mattered little to you before, suddenly takes on great importance. Such was the case with Quincy Jones' The Dude.

Released in 1981, two years after Jones industry changing collaboration with Michael Jackson , The Dude represented the height of Jones critical and commercial powers; it earned two Grammy awards, with Jones also winning for Producer of the Year in 1982. Like many of Jones' Soul-Jazz-Pop hybrids the recording featured his regular musical collaborators including his God-daughter Patti Austin and a relatively unknown vocalist named James Ingram. The Dude was Ingram's break out effort, singing lead on Jones "Just Once," and "One Hundred Ways." By the end of 1982, Ingram was a fixture on the pop charts with his duet with Patti Austin "Baby Come to Me," which was cross-marketed via a story line on ABC's General Hospital.

It was "One Hundred Ways," that was in my head the morning of June 28, 1982. It was the last day of school and Gloria and I (along with two of her friends) were going on our first "date" after school. So after school we trekked to the McDonald's across the street from the old Yankee Stadium and Macombs Dam Park (where the new Yankee Stadium currently stands). All I had was fries, too self-conscious of eating in front of the girl, as we chatted about the summer, knowing that we likely wouldn't see each other until the following August. Two months is a long time in the life of teen-agers—two months that we would not survive.

Macombs Dam ParkAt the time "One Hundred Ways" struck such a chord in me, because it was all about the myriad ways that one can show affection. At 16, I was limited to about three of those "one hundred ways"; in many ways my relationship with this woman over the last 23 1/2 years (including19 years and 10 days of marriage) has been about realizing the full range of those "one hundred ways." It's a struggle, but that's what lasting relationships are all about.

Macombs Dam ParkAt the time "One Hundred Ways" struck such a chord in me, because it was all about the myriad ways that one can show affection. At 16, I was limited to about three of those "one hundred ways"; in many ways my relationship with this woman over the last 23 1/2 years (including19 years and 10 days of marriage) has been about realizing the full range of those "one hundred ways." It's a struggle, but that's what lasting relationships are all about.

Published on July 08, 2011 10:54

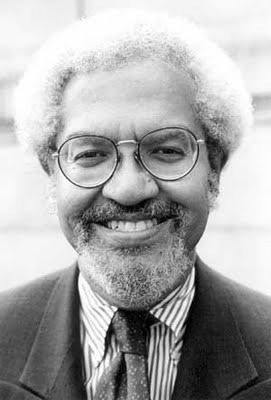

Manning Marable and the Malcolm X Biography Controversy: A Response

Manning Marable and the Malcolm X Biography Controversy: A Response by Bill Fletcher, Jr. | The Black Commentator

"In order to understand what is going on, one must identify multiple sources, much of which has almost nothing to do with the book itself. These include: the creation of Malcolm-as-icon; homophobia; personal jealousy targeted at Marable; New York chauvinism targeted at Marable; and on-going differences regarding strategy within the Black Freedom Movement."

On the day of Manning Marable's death, April 1, 2011, I received an additional piece of disturbing information. A friend of mine informed me of a discussion he had just had with a Black activist-writer who, in hearing about Marable's passing, went into what could only be described as a rant against Marable. Marable's body was hardly cold, and this individual, who knew Marable, was castigating him to my friend, claiming that Marable was everything but a child of God. It was at that moment that I knew that Marable's Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (hereafter referred to as MX) would ignite a firestorm in some quarters of the Black Freedom Movement. Within days, despite the overwhelmingly positive response to the book, this firestorm emerged.

In approaching the controversies that surround MX it is important to ask two questions prior to responding directly to critics: (1)what did Manning set out to do? (2)did he succeed? We will take these one at a time before commenting on some of the issues raised by various critics and what lies beneath them.

What did Manning set out to do?

MX is a blockbuster of enormous proportions. The mere act of writing a 500+ page biography is a significant achievement on any scale. Yet Marable was not attempting to write the definitive biography when he first started out on this journey. As he himself noted, his first objective was to write what he called a "political biography" of Malcolm X. Over time the objectives shifted somewhat and became a bit more complex.

Much has been made of the biography "humanizing" Malcolm, a term which I have myself used. Yet that is not the starting point for understanding the objectives. A better starting point is perhaps derived from Marable's own statements on the matter, the gist of which begins with the fact that Malcolm X had been—and remained—a hero for Marable, who, in his opinion, had been the most significant Black activist figure of the mid-to-late 20th century. It was Marable's committed belief in Malcolm X's significance that moved him to dedicate the last decade of his life to chronicling Malcolm's life and legacy through the Malcolm X Project at Columbia University. And it is this same commitment to Malcolm X's and his family's legacy that caused Marable to utilize his institutional influence and resources to push Columbia University to make good on its promise to open the site of the former Audubon Ballroom as the Malcolm X & Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial Center. MX is the product of a historian who cared deeply for his subject, who felt that his subject was deserving of a comprehensive examination of his life. Marable took this task seriously, grappling with aspects of Malcolm's life that he knew would challenge our iconic view of Malcolm but also do it in a way that would deepen our appreciation of his heroicism as human being to other human beings. Yet in trying to understand Malcolm's trajectory, not just when he left the Nation of Islam, but much earlier, there were curious features in the Autobiography of Malcolm X that were difficult to either understand or explain.

Read the Full Essay @ The Black Commentator

Published on July 08, 2011 07:06

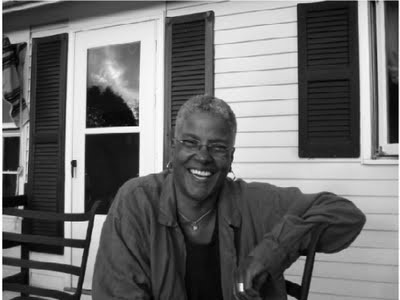

Cheryl Clarke: The Never-Ending Resource that is Black Queerness

Cheryl Clarke: The Never-Ending Resource that is Black Queerness by Darnell L. Moore | Lambda Literary

"There is queer activism in the African diaspora and wherever that movement is, there is always cultural production."

I was introduced to the iconic Cheryl Clarke while organizing a conference on spirituality and sexuality with writer and scholar Ashon T. Crawley for the Newark Pride Alliance in Newark, NJ in 2008. Ashon and I marveled for days over the fact that we had engaged in a few contentious planning meetings with Clarke, and survived! Our meeting spurred an instant love affair with the black queer literary luminary whose voice, work, and life has continued to make space for our own. Since 2008, Clarke and I have been involved in several projects and after each I end by asking myself: "Why have we—black folk, queer folk, feminist folk, and other folk—yet to fully recognize this genius among us?" This is my second interview with Clarke. The first was a conversation captured between Clarke and Amiri Baraka in Newark, NJ. In many ways, this is my way of turning attention to a black queer artist whose work deserves increased attention.

Clarke was born in 1947 in Washington, DC. She received a B.A. from Howard University and an M.A., M.S.W. and Ph. D. from Rutgers—the State University of New Jersey. She is the author of several books including her collection of prose and poetry, The Days of Good Looks, and her critical work, "After Mecca": Women Poets and the Black Arts Movement. Clarke's "After Mecca" is the first scholarly work investigating the role of black women poets/writers situated within the ten-year period of 1968-78, a decade encompassing the Black Arts Movement (BAM). BAM was a political, aesthetical movement that was spurred as a result of the Black consciousness/Black Power movement as a means to further the development and transmission of black expressive culture towards the end of radical communal change. Clarke's work demonstrates that women (including lesbian-identified women) made important feminist interventions in a staunchly sexist (and heterosexist) aesthetical space and used some of BAM's tactics to advance their own movement.

Since 2009, Clarke has been the Dean of Students for Livingston Campus at Rutgers. Prior to that position, she was the Director of the Office of Social Justice Education and LGBT Communities at Rutgers.

Read the Full Interview @ Lambda Literary

Published on July 08, 2011 06:47

The Mis-Adventures of Awkward Black Girl--Episode # 6

Episode 6: "The Stapler"

Unable to properly deal with her personal frustration in the workplace, J is sent to anger management.

(http://awkwardblackgirl.com) Created by Issa Rae (http://issarae.com)

Published on July 08, 2011 06:27

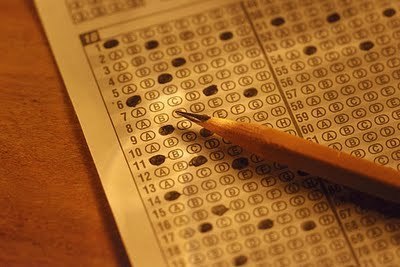

Exposing Education Reform's Big Lie: The Atlanta Test Scores Scandal

Exposing Education Reform's Big Lie: The Atlanta Test Scores Scandal by Mark Naison | special to NewBlackMan

Once again, a major cheating scandal has been uncovered in an urban school district. What happened in Houston ten years ago (but not before it's allegedly miraculous test score gains helped spawn No Child Left Behind) has happened in Atlanta. A state investigation has uncovered systematic falsification of test scores by teachers, principals, and district administrators in a district where careers could be made or broken by those results, leading to the resignation of the district superintendant and potential suspensions, and possibly criminal indictments, or scores of teachers and principals.

To regard what took place in Atlanta as an exception to an otherwise unblemished record of probity in administering standardized tests would be like regarding Bernie Madoff's ponzi scheme as an aberration in an otherwise healthy financial system. In each instance, unscrupulous individuals took the basic tenets of a flawed system to an extreme. In the case of Madoff, he provided clients with high returns based on non-existent investments, rather than flawed ones ( subprime mortgages packed into Triple A bonds); in the case of Atlanta, officials decided to invent impossible results rather than browbeat and terminate teachers and principals when they didn't achieve them.

Let us be clear--the Atlanta scandal is the logical outcome of a national movement, supported by government and private capital, to radically improve school performance and hopefully lift people out of poverty, through a centrally imposed and rigidly administered combination of privatization, competition, material incentives and high stakes testing. You would think that a movement which commands such widespread support, and extraordinary resources, has a history of proven examples, either in the US, or other nations, to guide its implementation.

But the truth is that there is not a single time in American history--with the exception of the ten years following the end of slavery--where you can point to educational reform as a factor which lifted a group out of poverty, or allowed an important minority group to improve its status relative to the majority population. The kind of "heavy" lifting required to do that, with that one exception of the Reconstruction Era, during which activists founded schools for a people once denied literacy, has come, not from top down educational reform, but from bottom up political mobilization, coupled with changes in labor markets which radically improve earning opportunities for the group in question.

Let us look at the one moment in the 20th Century where the African American population not only experienced a rapid improvement in its economic status, but improved its status relative to whites, the time between 1940 and 1950. During those ten years, Black per capital income rose from 44% of the white total to 57%. This income growth was not only a result of wartime prosperity, and Black migration from the rural to urban areas, but a result of the protest movement launched by A Phillip Randolph in 1941 to demand equal treatment for Blacks in the emerging war economy, as well as the enrollment of Black workers in industrial unions.

Randolph's march on Washington Movement didn't lead to the desegregation of the armed forces, but it did lead President Roosevelt to issue a proclamation requiring non-discriminatory employment in defense industries and to create a Commission to enforce this decree. While huge pockets of discrimination remained, African Americans, women as well as men, found work in factories throughout the nation producing ships, aircraft, and motorized vehicles and were enrolled in the unions that represented the bulk of workers involved in war production.

In Detroit, in Los Angeles, in Youngstown, in Pittsburgh, in Richmond California, Black workers, many of them newly arrived in the South were earning incomes four to five times what they would have made as sharecroppers or tenant farmers and had union protection in their places of employment. This economic revolution spawned a political revolution, with nearly 500,000 African Americans joining the NAACP, and a cultural one as well, with rhythm and blues becoming the music of choice for the emerging black working class, inspiring clubs and radio stations and small record labels to cater to this rapidly growing black consumer market.

Though educational opportunities for blacks did improve in this period, it was changes in the job market, fought for, and consolidated by grass roots political movements, reinforced by strong labor unions, that were the primary engine of change.

There is a lesson here that activists and educators should consider. If you want to improve economic conditions in Black and working class neighborhoods, than it would make more sense to raise incomes, either by unionizing low wage industries, or demanding that tax revenues be directed into job creation, rather than trying to legislate magical improvements in schools based on results on standardized tests.

Children living in impoverished communities cannot be magically vaulted into the middle class by pounding information into their heads and testing them on it relentlessly . However, their parents, and older brothers and sisters, can be lifted into the middle class through jobs that offer decent incomes and security coupled with opportunity for personal advancement through education.

School Reform is the American Elite's preferred response to poverty and inequality, a strategy that requires no sacrifice, no redistribution nor any self-organization by America's disfranchised groups. Every day, it is proving itself a dismal failure

It's time that a new strategy be launched that focuses on jobs, economic opportunity and the redistribution of wealth, one linking civil rights groups, unions, and people living in working class and poor communities who have watched wealth and opportunity be siphoned out of their communities by the very wealthy- the same people, ironically, who are the biggest supporters of School Reform.

***

→Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies and History at Fordham University and Director of Fordham's Urban Studies Program. He is the author of two books, Communists in Harlem During the Depression and White Boy: A Memoir. Naison is also co-director of the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). Research from the BAAHP will be published in a forthcoming collection of oral histories Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life From the 1930's to the 1960's.

Published on July 08, 2011 06:09

July 7, 2011

Strauss-Kahn, Domestic Immigrants and Money, Power, Respect

Strauss-Kahn, Domestic Immigrants and Money, Power, Respect by Tamura Lomax | The Feminist Wire

See I believe in money, power and respect. First you get the money. Then you get the motherf–kin' power. And after you get the f–kin' power. You get the f–kin' ni–az to respect you. It's the key to life. ~Lil' Kim

In 1998 when Lil' Kim penned these lyrics in the Hip Hop anthem, "Money, Power, Respect," she was likely drawing upon her early years as a struggling teen on the streets of Brooklyn with limited resources and no real place to call home. In my naivety, I assumed that Lil' Kim was talking about something she in fact had, not what she and countless others like her would spend a lifetime longing for. Today, these lyrics continue to ring true for women and men alike. For black diasporic women and girls, they are particularly profound. However, for immigrant domestic workers, Lil' Kim's lyrics are prophetic. Money, power and respect is exactly what former IMF Managing Director (and front-runner for the 2012 French presidential election) Dominique Strauss-Kahn, 62, has, and what the unnamed 32-year-old Guinean housekeeper, who accused Strauss-Kahn of sexual assault in a Manhattan hotel in May, needs to be taken seriously and to win her case against him.

According to the woman's initial testimony, she entered Strauss-Kahn's suite at approximately 1 p.m. believing it was unoccupied. As the housekeeper cleaned the foyer, Strauss-Kahn "came out of the bathroom, fully naked, and attempted to sexually assault her." As she fought him, he "locked the door to the suite," "grabbed her and pulled her into the bedroom and onto the bed." After which, "he…dragged her down the hallway to the bathroom, where he sexually assaulted her a second time." After fleeing, the woman reported the incident to hotel personnel who called 911. Upon boarding Air France Flight 23, Strauss-Kahn was apprehended and taken into custody, throwing the French political world, U.S. media and life of the 32-year-old Guinean housekeeper into utter mayhem.

Just last week The New York Times reported that Strauss-Kahn prosecution was "near collapse." "Major holes" were found in the credibility of the Guinean housekeeper, although forensic tests found unambiguous evidence of a sexual encounter between the two, and despite evidence of force (i.e. torn clothing, bruising, etc.). According to the prosecution, the accuser has repeatedly lied since her initial allegation on May 14.

Among the discoveries, one of the officials said, are issues involving the asylum application of the 32-year-old housekeeper, who is Guinean, and possible links to people involved in criminal activities, including drug dealing and money laundering.

Ultimately, the accuser falls short of the Victorian ideal. Like the rest of us, she is neither perfect nor without blemish (nor can she pay to appear as such). Thus, the circumstances surrounding the encounter on May 14, notwithstanding forensic and physical evidence, and personal testimony (of the victim and others alike), must be called into question. Moreover, Strauss-Kahn, who has already fallen from political grace and been replaced (perhaps conveniently), must now be exonerated (maybe, just in time to announce his candidacy for the French presidency). According to The New York Times he was released July 2. The case is now moving toward dismissal.

Read the Full Essay @ The Feminist Wire

Published on July 07, 2011 11:57

July 6, 2011

Remembering Professor Clyde Woods

Professor Clyde Woods | UC Santa Barbara

Professor Clyde Woods | UC Santa BarbaraRemembering Professor Clyde Woods by Mark Anthony Neal

"These groups [the black poor of the Mississippi Delta] learned a painful lesson that many scholars have yet to learn; slavery and the plantation are not an anathema to capitalism but are pillars of it…Slavery, sharecropping, mechanization, and prison, wage, and migratory labor are just a few permutations possible within a plantation complex. None of these forms changes the basic features of resource monopoly and extreme ethnic and class polarization." -- Clyde Woods

I first read Professor Clyde Woods' Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta (Verso) shortly after it and my book What the Music Said were published. My immediate reaction was "damn, think I need to go back to the lab." Thirteen years later, Development Arrested remains the most sophisticated analysis of the political economy of Black music that has been published in the last generation, in part because Woods never lost sight of the fact that the very economic engines that drove the degradation and exploitation of Black workers in the Delta, inspired a resistance to those engines in the music of the region—not simply through ideological retorts, but in creating something that soothed the souls of a people well beyond weary.

Yet the brilliance of the man's work, paled in the light of the man's humanity; He was simply "Good People." Professor Woods and I crossed paths finally in 2003, in a way that bespeaks his good and supportive nature; he simply showed up to a reading that my friend and journalist Esther Iverem hosted at her Washington DC home in support of my book Songs in the Key of Black Life. What I recall from that first encounter, is meeting a dude that I wished I had had the opportunity to connect with much earlier in my professional life. Still can remember talking to him about Hip-Hop's Blues aesthetic, as he reeled off lyric after lyric from Scarface to make his point. I never heard Scarface, or Southern rap for that matter, the same after that.

Yet the brilliance of the man's work, paled in the light of the man's humanity; He was simply "Good People." Professor Woods and I crossed paths finally in 2003, in a way that bespeaks his good and supportive nature; he simply showed up to a reading that my friend and journalist Esther Iverem hosted at her Washington DC home in support of my book Songs in the Key of Black Life. What I recall from that first encounter, is meeting a dude that I wished I had had the opportunity to connect with much earlier in my professional life. Still can remember talking to him about Hip-Hop's Blues aesthetic, as he reeled off lyric after lyric from Scarface to make his point. I never heard Scarface, or Southern rap for that matter, the same after that.Over the past few years I was fortunate enough to run into Professor Woods fairly regularly at the annual American Studies Association meeting. Last time I saw him, was at the 2009 American Studies Meeting in Washington DC; he was holding court, fittingly, with a group of students and New Orleans poet and activist Kalamu Y Salaam. Months later his edited volume In the Wake of Hurricane Katrina: New Paradigms and Social Visions was published, putting a fine point on all of the scholarship that was produced in the wake of Katrina. Yet, as in all of his work, Professor Woods found that common thread to Black humanity, in what he regularly referred to as the "blues tradition of investigation and interpretation."

There are many scholars who make lasting impressions with their work, but comparatively few that make those same impressions as simply good people. Professor Clyde Woods was the rare person who did both. He will be missed.

Published on July 06, 2011 17:40

20 Years in 27 Days: A Marriage in Music | Day #6: The Dazz Band—"Let It Whip")

20 Years in 27 Days: A Marriage in Music Day #6: The Dazz Band—"Let it Whip"by Mark Anthony Neal

From July 14, 1973, until June 26, 1982, Billboard Magazine published the "Hot Soul Singles" chart every week. The first song to top that chart was Johnnie Taylor's "I Believe in You (You Believe in Me"; the last song to top that chart was The Dazz Band's "Let It Whip." The "Black Singles" chart debuted in June of 1982 with w the Gap Band's "Early in the Morning" sitting atop. The shift was a reflection of the increasing tensions about how "Blackness" was going to be represented in the marketplace.

As such "Soul" meant a connection to a past of struggle and down-hominess, while "Black" was the catch-phrase for a Black Middle Class flexing its muscle in the marketplace and at the polls. Artists like Taylor and Fred Wesley, who preceded him at the top of the "Soul Singles" chart, couldn't even get played on Black radio stations in 1982. That ambivalent space between holding on to the traditions that Soul represented and Black aspiration found its resonance in early 1980s (electro) Funk; music that was unapologetically Black—even as it was coming from places Ohio and Oklahoma as was the case with The Dazz Band and The Gap Band—yet such a far-cry from the music that Black folk marched and protested to.

In the months after the Billboard chart shift, Wilson Goode and Harold Washington would be elected the first Black mayors of Philadelphia and Chicago, respectively, Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley would make a serious run for the California Governorship and Rev. Jesse Jackson would begin his quest for the Presidency of the United States. I didn't care much about any of this in June of 1982, as I was in love with that lil Brown-eyed gal. Though it wasn't apparent at the time, what would make this thing with Peaches and I work (eventually), was that we were products of a Black working class world, with parents who shared the same "down South up North" values, but we were also enticed by the aspirational desires of our middle class peers.

Published on July 06, 2011 14:28

July 5, 2011

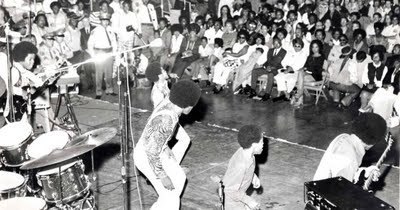

Trapped in Motown's Closet

Was Motown also the "Sound of Gay America"?

Trapped in Motown's Closet by Mark Anthony Neal

Nearly 35 years before the release of Lady Gaga's Born This Way, a Gospel singer turned Disco star, recorded a song bearing the same title, which became one of the era's most important Gay anthems. That a Baltimore bred, African-American man, who came of age during the height of Civil Rights movement could so seamlessly wed the Gospel impulses of this nation's most affecting social movement, with the nascent impulses of the GLBT movement—"Yes I'm gay/tain't a fault 'tis a fact/I was born this way"—should not be surprising. That Bean did so recording for Motown Records, a company that symbolized the push for Black integration and respectability in the 1960s and 1970s, should elicit some wonder. Bean was not alone; in the mid-1970s the Motown roster also included the vocal group the Dynamic Superiors, whose lead singer, the late Tony Washington, was an out and flamboyant homosexual. Though the musical legacies of both acts, have been largely obscured over the years, their connection to, arguably, the most prominent Black brand of the 20th Century speaks volumes about how inclusive Berry Gordy's vision was with regards to what he called the "Sound of Young America."

Whenever the subject of Black music and homosexuality is broached, the figure of Sylvester, the groundbreaking Disco and Dance artist, is immediately recalled. While the Dynamic Superiors and Carl Bean where contemporaries of Sylvester, it is important to remember that both acts had already broken through to the mainstream before Sylvester released his influential classic Step II in 1978. As a solo artist committed to drag performances, Sylvester became the quintessential example of Black artists who successfully challenged the boundaries of race, sexuality and gender. Sylvester was indeed peerless, but not without precedent, if you consider artists such as Billy Strayhorn (Duke Ellington's longtime contributor), Nona Hendryx, and Bessie Smith.

Not surprisingly, even Sylvester owed some debt to Motown for his success. Sylvester's 1977 solo debut Over and Over was produced by Harvey Fuqua, founding member of the doo-wop group the Moonglows and one-time Motown record executive, who was responsible for bringing Marvin Gaye to the label. The title track of Sylvester's solo debut was a cover of a Nick Ashford and Valerie Simpson song, featured on their 1977 album So So Satisfied. Ashford and Simpson, of course, were the well known song-writing duo behind the great Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell recordings of the late 1960s; they were also responsible for the songwriting and production on the first two Dynamic Superior recordings, their eponymous 1974 debut and Pure Pleasure (1975).

Products of the Washington DC housing projects, the Dynamic Superiors began singing with each other as high school students in the late 1960s. Their big break came when they performed at a music industry showcase in 1972 and were spotted by Motown executive, Ewart Abner, most well known for his work as President of Black owned Vee Jay Records which featured acts like Gene Chandler and Jerry Butler and distributed the initial American releases of The Beatles. The group was quickly signed by Motown and their first album The Dynamic Superiors was released in 1974. The lead single, "Shoe, Shoe Shine," was in the vein of the popular harmony groups of the day like the Stylistics and Blue Magic, and as lead singer, Tony Washington's falsetto was every bit the match of Russell Thompkins, Jr. and Ted Mills, respectively.

Yet, Washington exuded something more—a something more that can be easily recognized on the cover art from that first album. For a label that years earlier released an Isley Brothers album with a picture of a White couple on the cover in order to enhance crossover and in the late 1970s released Teena Marie's debut without a photo in order to obscure her White identity, Motown's willingness to even visually suggest Washington's queerness is striking. Whatever curiosities arose in response to that album cover would be put to rest when the group began, rather famously to perform a cover of Billy Paul's "Me and Mrs. Jones," in concert with Washington clearly singing "Me and Mr. Jones." Such performances quickly had the Black Press describing the Dynamaic Superiors as a "gay" group, as was the case when a 1977 feature on the group in the New York Amsterdam News was titled "Dynamic Superiors Lead 'Gay' Music Crusade," of course begging the question, what exactly is "gay' music and what crusade was it a part of? (questions that the paper had no intention of answering in 1977).''

Yet, Washington exuded something more—a something more that can be easily recognized on the cover art from that first album. For a label that years earlier released an Isley Brothers album with a picture of a White couple on the cover in order to enhance crossover and in the late 1970s released Teena Marie's debut without a photo in order to obscure her White identity, Motown's willingness to even visually suggest Washington's queerness is striking. Whatever curiosities arose in response to that album cover would be put to rest when the group began, rather famously to perform a cover of Billy Paul's "Me and Mrs. Jones," in concert with Washington clearly singing "Me and Mr. Jones." Such performances quickly had the Black Press describing the Dynamaic Superiors as a "gay" group, as was the case when a 1977 feature on the group in the New York Amsterdam News was titled "Dynamic Superiors Lead 'Gay' Music Crusade," of course begging the question, what exactly is "gay' music and what crusade was it a part of? (questions that the paper had no intention of answering in 1977).''The group didn't make much of such descriptions; in a magazine article in 1977 (New Gay Life), simply Washington suggested that "I guess it's because it's me myself. The fact that I'm the lead singer. I don't hide it on stage." Washington's brother Maurice, also a member of the group adds in the same magazine piece, "It was always there. We just brought it out. Tony was just another member of the Dynamic Superiors…He never did hide." In an era when no one talked openly about Black queer identity, Maurice Washington suggests that his brother's willingness to be "out" on stage was empowering to some audience members: "there are a lot more homosexuals there than we think. But, they don't care to let it out. Quite often after the show they want to meet Tony and want to thank him for being as open as they wish they could be…Tony's a great inspiration."

However progressive Tony Washington's band mates may have been in their views about homosexuality—it was in fact his voice that made the group so distinct—audiences were not always in sync. As Washington admitted to The Advocate in 1977, "I guess I was trying to push the clock ahead, though I wasn't that flamboyant in the beginning…I tried to ease it on them, bit by bit. I thought to myself, man, my makeup is part of the program, so why not accept it." Washington often made the point, as he did to the Baltimore Afro-American in 1977 that "we are everyday people…we are proud and excited about what we do, but we still have our same friends in Washington."

The Dynamic Superiors released four albums for Motown between 1974 and 1977. Trying to find just the right musical touch, Motown hired Ashford ands Simpson to do production on the first two albums, despite the fact the duo had departed the label in 1973, in part, because the label never saw them as a viable group (Valerie Simpson recorded two solo albums for the label in the early 1970s). On those first two albums, one can hear the embryo of what would become Ashford and Simpson's late 1970s sound; heavy indebtednes to the Motown assembly line and deeply steeped in the Black gospel tradition that formed the foundation of the couple's professional relationship in the mid-1960s. Washington and Ashford share similar vocal traits, so a song like the dramatic "Cry If You Want To" sounds like classic Ashford and Simpson, as does "Leave It Alone," which was later samples by Noel Gourdin on "Better Man" from his debut After My Time.

It wasn't until their second album, Pure Pleasure (1975) that the group began to broach queer themes in their music. Packaged in the guise of the personal freedoms that marked the 1970s, their cover of the Ashford & Simpson penned Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell classic "Ain't Nothing Like the Real Thing" (a male duet of a song most known as a male/female duet) or a song like "Nobody's Gonna Change Me," became anthems for all those working on the margins.

The subsequent decision to gear The Dynamic Superiors towards disco was prescient, if eventually limiting for a group that got its start as a vocal harmony group. The Dynamic Superiors didn't really reach their audience, in this regard, until their fourth (and last) Motown album, Give and Take, which features with a Disco cover (again) of Martha and the Vandella's "Nowhere to Run." The song succeeded in part, because, the dancefloor became one of the primary sites where sexuality was being negotiated in the 1970s; seemingly the Disco was the only place where folk had the freedom to come out, given the rampant homophobia of the era, which was manifested in thinly veiled "Disco Sucks" rhetoric.

At the time that "Nowhere to Hide," was released, Motown was heavily invested in Disco music, if only because Berry Gordy was always conscious of the money flow. If Disco was going to dominate the radio, and Philadelphia International Records (PIR) was building an empire, in part because of its role in creating the building blocks for Disco, Motown was, literally, going to be in the mix. Like PIR, Motown was influential in the formative years of Disco; Eddie Kendricks' "Girl You Need a Change of Mind" (1972) is often cited as the first Disco record and his "Keep On Truckin'" (1973) was one of the label's biggest singles in the early 1970s. The solo careers of David Ruffin, Diana Ross, Michael Jackson and the Jackson 5 were all re-booted in the mid-1970s with Disco tracks, such as Ruffin's "Walk Away from Love," (1975) Ross's "Love Hangover," (1976) Jackson's "Just A Little Bit of You" (1975) and The Jackson 5's "Forever Came Today" (1975). Indeed the future trajectory of Michael Jackson post-Motown career was largely shaped by his desire to find his own voice within the Disco idiom.

Given the label's commitment to Disco—even Marvin Gaye released "Got to Give It Up"—it would seem that Motown likely placed little significance on Carl Bean's "I was Born This Way." In fact, Bean's version was the label's second go-round with the song. The song, which was written by Bunny Jones, was initially recorded by an artist named Valentino and released independently by Jones. As the song topped the dance charts in England, Motown purchased the rights from Jones. When Motown botched the song's promotion—and understandably so—Valentino's version died, only to be resuscitated a year later by Bean, on a recording that featured veteran PIR and MFSB guitarist Norman Harris and Ron Kersey, who was a member of the Trammps ("Disco Inferno"), in an effort to give the song that PIR sheen.

Carl Bean was not new to the music industry; as an already out Black man, he began his professional career in a Gospel troupe led by legend Alex Bradford. With the group, Bean had the opportunity to perform on Broadway in shows like Your Arms Too Short to Box with God and Don't Bother Me I Can't Cope. By 1974 was fronting a group called Universal Love that was signed to the ABC/Peacock label. The group faltered, as Bean explains in his recently published memoir I Was Born This Way, because the group was "ahead of the curve. I was part of a movement looking to erase the line between R&B and gospel." (175)

Nevertheless, Bean showed up on Motown's radar because of Universal Love. According to Bean, in his first meeting with Motown executive Gwen Gordy, she admitted that her brother Berry thought "Bean would be perfect. It's a message song with a gospel feel. Bean will tear it up." (193) Besides Harris and Kersey, Motown brought in Tom Moulton for an extended mix, that was marketed directly to Discos, since Black radio stations were unlikely to support the song, even from a valued label like Motown. In the book, The Fabulous Sylvester, DJ Leslie Stoval tells author Joshua Gamson that Sylvester was "informally blacklisted because he was gay…they weren't ready to give this gay man his place. They didn't want to deal with it." (127) Such was the environment that Motown and Bean faced. Nevertheless, without the support of radio, "I Was Born This Way" became a major club hit, that placed Carl Bean on the precipice of major success.

Nevertheless, Bean showed up on Motown's radar because of Universal Love. According to Bean, in his first meeting with Motown executive Gwen Gordy, she admitted that her brother Berry thought "Bean would be perfect. It's a message song with a gospel feel. Bean will tear it up." (193) Besides Harris and Kersey, Motown brought in Tom Moulton for an extended mix, that was marketed directly to Discos, since Black radio stations were unlikely to support the song, even from a valued label like Motown. In the book, The Fabulous Sylvester, DJ Leslie Stoval tells author Joshua Gamson that Sylvester was "informally blacklisted because he was gay…they weren't ready to give this gay man his place. They didn't want to deal with it." (127) Such was the environment that Motown and Bean faced. Nevertheless, without the support of radio, "I Was Born This Way" became a major club hit, that placed Carl Bean on the precipice of major success.With "I was Born This Way," Carl Bean was in position to became everything that Sylvester became, and to their credit Motown was ready to make Bean its next major start, but with a caveat. After Bean signed with the label, he was given the opportunity to record an album that was initially intended for David Ruffin. As Bean recalls in his memoir, the "tracks were smoking-hot R&B. And the lyrics were all about love and ex—love and sex between a man and a woman." As label executives promised Bean that he could become the next Teddy Pendergrass, he choose to walk away from the deal rather record as an heterosexual.

Bean eventually found another calling, one that led him back to the church and into the role as a prominent AIDs activist. The founder of the Unity Fellowship of Christ Church in Los Angeles (which was featured in the Marlon Riggs' groundbreaking documentary Black Is, Black Ain't), Archbishop Carl Bean has been an important advocate for many communities, providing one of the few Christian-based safe havens for Black LGBT communities and founding one of the first AIDs hospices in the country. For Bean, his sexual identity and faith were never at odds, as he explained in a 1978 magazine article that "it's God's way of making a statement through me…it's something that should have been said a long time ago."

One wonders if Carl Bean and Tony Washington ever crossed paths at Motown; Washington is rumored to have died from AIDs, after the Dynamic Superiors broke up in 1980. Bean and Washington's legacies will forever be linked, reminding folks of the time when Motown was not only the "sound of Young America," but perhaps the "Sound of Queer America."

***

Major h/t to Queer Music Heritage for their postings of article about Tony Washington and Carl Bean.

Published on July 05, 2011 20:17

The Business of Soul

Classic J5

Classic J5Branding Soul? Considering The History of Black Music and Big Businessby Mark Anthony Neal | The Atlanta Post

The recent departure of Sylvia Rhone, from her position as President of Motown, received much attention, in part, because Erykah Badu's cryptic tweet "Motown folded." The subsequent obituaries and premature obituaries for the label, seemed odd, if only because Motown has for decades existed as little more than a shell of the company that Berry Gordy founded in 1959, living off the fumes of one of the most impressive back catalogues in all of American pop music—managed by Universal Music. Motown, for all intents "died" when it was sold to MCA in 1988, though Gordy wisely kept control of the Jobete Publishing company, which has proven more lucrative that the label ever was.

Instead the emotional reaction that many had to the potential "death" of Motown, speaks volumes, not only about the role of Soul music in the lives of many Americans, but also the cultural meanings that were assigned to record labels like Motown, Stax and later Philadelphia International Records (PIR), whose songs served as the soundtrack to Civil Rights struggles and post-Civil Rights era ambition.

Berry Gordy had a hustler's instinct that was emblematic of the immediate years after post-World War II in American culture. The American hustle was to sell the good life to as many buyers as possible. The expansion of advertising culture, as evidenced in Mad Men's throwback glance at the 1960s, went hand-in-hand with the institutionalization of corporate popular culture. Gordy learned his hustle from every other self-made business "man" of the 1950s, including record execs like Ahmet Ertugen, Jerry Wexler, and Don Robey (a loose inspiration for The Five Heart Beats' "Big Red").

Gordy may have loved music—he wrote hits for Jackie Wilson before founding Motown—but he was clear that Motown was, above all, a business. Gordy's genius was linking that hustling ethos to the assembly-line production he witnessed first hand working in Detroit's automobile factories. In creating Motown, Gordy was also establishing a brand; he called it "The Sound of Young America" and was intent that young Americans—particularly, young White Americans would enjoy leisurely summer trips to the beach listening to Motown artists such as the Temptations, The Four Tops, Mary Wells, Marvin Gaye and most famously the Supremes.

With attention to detail, which included etiquette classes for artists, highly choreographed stage performances and a structured recording environment that even included an elaborate quality control process, Motown earned a reputation for hit records that were polished and crisp.

Read the Full Essay @ The Atlanta Post

Published on July 05, 2011 19:39

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.