Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1076

June 25, 2011

Black Music Month 2011: Bassist/Producer Marcus Miller Remembers Miles Davis

from the JazzVideo Guy:

Bret Primack's 1998 interview with Marcus Miler. After a 30-year association with Columbia Records -- which had begun with 'Round About Midnight' way back in 1956 -- MILES DAVIS decided to sever ties with his old company and jump ship to Warner Bros. That was in 1986 and although a large amount of money helped facilitate his move, the iconic jazz trumpeter was in search of fresh musical inspiration. He found it in an unlikely source -- MARCUS MILLER, a 25-year-old Big Apple bass player who had first played with the 'Dark Magus' on his 1981 comeback album, The Man With The Horn. As Davis discovered, Miller was much more than a mere bassist -- he was a gifted multi-instrumentalist who could write, arrange and produce (he also had a parallel career in the R&B world as Luther Vandross's collaborator). Miller came up with Tutu, which with its reliance on synthesizers, drum machines and inclusion of pop elements and funky bass lines horrified many jazz critics. But it was an influential album and took Miles' music to a new generation of listeners.

Published on June 25, 2011 15:53

Black Muisc Month 2011: Bassist/Producer Marcus Miller Remembers Miles Davis

from the JazzVideo Guy:

Bret Primack's 1998 interview with Marcus Miler. After a 30-year association with Columbia Records -- which had begun with 'Round About Midnight' way back in 1956 -- MILES DAVIS decided to sever ties with his old company and jump ship to Warner Bros. That was in 1986 and although a large amount of money helped facilitate his move, the iconic jazz trumpeter was in search of fresh musical inspiration. He found it in an unlikely source -- MARCUS MILLER, a 25-year-old Big Apple bass player who had first played with the 'Dark Magus' on his 1981 comeback album, The Man With The Horn. As Davis discovered, Miller was much more than a mere bassist -- he was a gifted multi-instrumentalist who could write, arrange and produce (he also had a parallel career in the R&B world as Luther Vandross's collaborator). Miller came up with Tutu, which with its reliance on synthesizers, drum machines and inclusion of pop elements and funky bass lines horrified many jazz critics. But it was an influential album and took Miles' music to a new generation of listeners.

Published on June 25, 2011 15:53

Aishah Shahidah Simmons: "Reflecting Upon My Twenty-One Years Of Pride"

"I AM A FULL WOMAN"~ Rachel Bagby

"I AM A FULL WOMAN"~ Rachel BagbyJulie Yarbrough - photographer, Jennifer Ferriola - make -up, Summer Walker - stylist

Reflecting Upon My Twenty-One Years Of Pride by Aishah Shahidah Simmons | special to NewBlackMan

For Michael (Dad), Cheryl D., and Wadia...In Memory of Toni and Audre...

On the eve of the Pride parade in New York City, I reflect upon my very first New York Pride, which was in 1990. I was a very 'wet behind the ears,' 21-year old OUT 'Baby Dyke.' Wadia Gardiner, who was my first girlfriend as an adult, took me to the big city to celebrate PRIDE. That experience changed my life forever.

My being out as a LESBIAN is not solely political. It is literally and metaphorically about my own survival in the entity known as Aishah Shahidah Simmons in this lifetime. I will never ever condone my rape, which resulted in my pregnancy and abortion. At the same time, I know that my rape was connected to my deep seated internalized homophobia where I was a frightened teenager who literally thought I was going to be struck down by Allah (God). I can very vividly remember literally looking at the sky wondering when the striking would happen because of my attraction to women. I went to a high school (Philadelphia High School for Girls '231) where there were many of us who were either comfortable with or struggling through our queer identities. Equally as important there were many straight identified girls who were staunch allies of those who were/are queer. And yet, I still was terrified.

When I was eighteen in my senior year in high school struggling with my sexuality, Michael Simmons, my father, asked Cheryl Dowton, an out Black lesbian to talk to me about being a lesbian. My father didn't want me to think that being a lesbian was a bad thing. Equally as important he didn't want me to think that becoming a lesbian would mean that I would have to give up my racial identity. So it was extremely important to him that I have the opportunity to talk with a Black lesbian about all of my questions, anxieties and fears. Having the opportunity to talk with Cheryl allowed me to literally see that Black and lesbian were not contradictory identities. Even with my having a girlfriend in my senior year in high school, I was SO afraid that my connecting with Cheryl, didn't enable me to fully embrace my authentic self until three year later.

During my second year at Temple University, I went on a study abroad program to Mexico. During that journey, I was raped. My rape from an acquaintance in Mexico was directly related to my thinking something was wrong with me because I hadn't had (heterosexual, or homosexual, for that matter) sex in over a year (post my break up with my boyfriend). Clearly, as a woman, regardless of my sexual orientation, I could get raped at any point or time. This is based on the wretched global statistics about violence against women. However, in my specific instance, I was trying to prove that I was heterosexual and that's why I made the poor choices I made. Again, I want to be explicitly clear, I'm not nor would I EVER condone my rape. Poor choices and poor judgement should never EVER equate rape. The rape probably resulted in my pregnancy, though I'm not sure exactly. In my quest to both deny what happened and anesthetize my pain, the following night, post my rape; I had consensual sex with another man. When I returned to the States, I was six weeks shy of my 20th birthday and pregnant. I'm one of the fortunate women who was able to have a safe and legal abortion about one week after my 20th birthday. Albeit, I had to cross vitriolic anti-choice/anti reproductive justice protesters to get into the Elizabeth Blackwell Health Center for Women in Philadelphia.

Fast forward to the following year when I was 21 years old and finally coming to terms with the fact that I was a lesbian and that I could no longer keep it a secret from myself foremost, and the world secondarily, I called my teacher/mentor/Big Sista Toni Cade Bmabara several times and talked to her about my internal struggle, my fears of rejection, isolation, and alienation. Toni listened to me. She affirmed me. She encouraged me to be true to my spirit and myself without regards for what anyone else thought, said, and or wanted. During this conversation, Toni taught me two of many invaluable lessons, one, that the word sistah was both a noun and a verb and two, that the responsibility of the artist/cultural worker is to use their art/cultural work to make revolution irresistible.

During that same time I read Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde, which was given to me by a Holli Van Ness a colleague of mine at the American Friend Service Committee. Prior to reading that book, I didn't really know about Audre Lorde or her groundbreaking work. Audre Lorde's words both invigorated and challenged me to break the vicious cycle of silence and shame around being a lesbian. I was literally transformed in my bedroom while reading Sister Outsider. I devoured every single word as if my very life depended upon it. It was as if Audre Lorde were speaking directly to me. In that book, she addressed all of my issues and concerns. Her written words taught me that I had a responsibility to not only be out, but to be engaged in the international struggles of the oppressed as an out Black Feminist Lesbian. I know a metaphysical transformation happened where I went from being an afraid, frightened, and ashamed Black lesbian young woman, to an out Black lesbian activist after reading Sister Outsider.

I am keenly aware that the metaphysical transformation that occurred was a gradual process that began with my father's ongoing support, which commenced with his arranging for me to meet and talk with Cheryl Dowton as well as the conversations that I had with Toni. And yet, at the same time, Audre Lorde's words gave me the initial tools that I needed to embark on my journey as an out Black feminist lesbian. It was in April 1990 that I came out with a vengeance and vowed never ever to go back in the closet again.

It was during this time that I met Wadia. Nine years older than me, she was, in my eyes, a Lesbian veteran. While the relationship barely made it slightly over a year, it was one of the most profound connections for several reasons. One, Wadia is a Muslim who didn't see any contradiction between her sexuality and her spirituality. This was critical for me because I was raised Sufi Muslim and yet I thought Allah had forsaken me because of my sexual orientation. Wadia's absolute clarity about her connection to her faith helped me to understand that like with my race and my sexuality, which are bound into one, my spirituality is an integral part of who I am. It was a transformational experience because prior to meeting and getting involved with Wadia, I made the decision that I would face and burn in Hell later and live my life now, which meant I would sever my relationship with my faith. It was profound to perform Salats (Prayer) and do Dhikr with my Black woman partner. I still get teary eyed when I think about that homecoming where all of mySelves were embraced and acknowledged. I'm most grateful that my first partner was/is a Black Muslim Woman.

Two, in addition to helping me reintegrate back into my Spiritual life, Wadia introduced to me to a world of Black, Latina, Asian, Indigenous, European (American) and Arab feminist lesbians who were/are cultural workers, musicians, scholars, jewelers, activists, healthcare practitioners, and organizers based in Philadelphia, New York, and other parts of the country. More often than not, I was by far one of the younger ones in the private and public spaces where we gathered. I have many fond memories of our tenure together, including a two month journey to Mexico where I reclaimed the space/place where I was raped. However, the one memory that will always hold a deep place in my heart is New York Pride. This was years before the police clamped down on the Pier where after marching in the PRIDE Parade, we (women, men, trans) gathered to pour libation, drum, perform spoken word, eat food, embrace, dance and BE IN ALL OF OUR (predominantly) COLORED LGBT PRIDE AND GLORY well into the wee hours of the morning… My Goddess that was a profound gift… Once I made peace with my lesbian identity, I was able to focus my attention on my life's work, which was/is to use the camera lens and written word to (hopefully) make radical, peaceful, compassionate revolution irresistible. To this very day Wadia is one of my most trusted friends/confidantes/comrades. We are family.

June 2011 a different landscape from June 1990.

There's marriage equality for all in NY, and yet for so many of us who are Queer identified, we're still not safe and protected. I believe EVERYONE, regardless of their sexual orientation, who wants to get married, should have the right to get married. At the same time, I don't want to have to get married to have rights and privileges, which should be made available to everyone, regardless of their marital status. I celebrate this Marriage Equality victory while not losing sight that the battle is SO far from being over that it's not even funny.

Just ask my Black Lesbian sisters (The New York Four) who are (unjustly and inhumanely) incarcerated for protecting themselves against sexist and homophobic violence perpetuated against them in the (safe, White) queer friendly Village… You can read Imani Henry's poignant 2007 essay.

This is one of many countless examples of the ongoing assaults on Queer people of Color throughout NY and across the country… Just ask or check in with The Audre Lorde Project or Queers for Economic Justice, to name two radical and revolutionary NY-based Queer organizations. Also the recently released Queer (In)Justice The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States by Joey Mogul, Andrea Ritchie, and Kay Whitlock is groundbreaking, sobering, and a must read. http://www.queerinjustice.com/

Twenty-one years later, I joyously celebrate PRIDE while I interrogate the various ways, at various junctures on my journey as an out lesbian; I colluded in my own invisibility. I recognize that there aren't any clear-cut lines in the struggle to eradicate internalized and external oppression. Often times it's a trial and error process, where hopefully we can learn to both have compassion and forgive each other and ourselves.

***

Aishah Shahidah Simmons is an award-winning African-American feminist lesbian independent documentary filmmaker, television and radio producer, published writer, international lecturer, and activist based in Philadelphia, PA. Simmons is the writer, director and producer of NO! the Rape Documentary, a ground-breaking film that explores the issues of sexual violence and rape against Black women and girls.

Published on June 25, 2011 12:53

June 24, 2011

"We Invented the Remix": The Legacy of Tom Moulton and Philadelphia Soul

"We Invented the Remix": The Legacy of Tom Moulton and Philadelphia Soul by Mark Anthony Neal

"As the dance floor itself became a site where the African-American Diaspora reintegrated with itself, Gamble and Huff…created a soundtrack aimed at repairing and sustaining communal relations across the chasms of class and geography." —What the Music Said: Black Popular Music and Black Public Culture (1999)

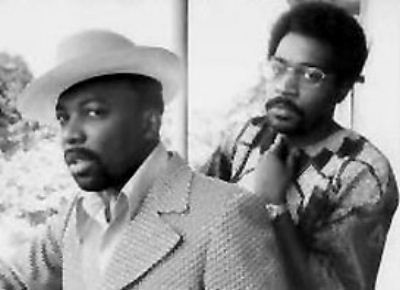

For Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff, Philadelphia International Records (PIR) was always more than a record company. Though they, along with Mighty Three publishing partner Thom Bell, were the most visible practitioners of "Philly Soul," the music of PIR was as much a social movement; Gamble's pseudo-political uplift narratives often finding a space on the album jackets of their artists and in the lyrics, he often wrote for those artists.

Artists such as The O'Jay's ("For the Love of Money" and "Give the People What They Want"), Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes ("Wake Up Everybody" and "Be for Real"), the Intruders ("I'll Always Love My Mama") and McFadden and Whitehead ("Ain't No Stoppin' Us Now") were the musical mouthpieces for Gamble and Huff's belief that the "revolution" (spinning at 33 1/3 rpms) would be broadcast on radio stations and mixed on dance floors across the nation. Producer Tom Moulton, was a willing conspirator in Gamble and Huff's dance floor revolution and Philadelphia Classics (originally released in 1977) showcased Moulton's extended remixes of some of PIR's most classic sides.

Moulton was first approached by Harry Chipetz, general manager of Sigma Sound Studios—where Gamble and Huff et al did most of their magic—to mix one of PIRs songs, as a way to introduce his skills to the duo. That song was People Choice's bumping groove "Do It Any Way You Wanna," notable because the song is one of the few PIR hits that lacks PIR's signature string arrangements. It was also Chipetz, who suggested that Moulton embark on the full-length remix project that would eventually become Philadelphia Classics.

Moulton had been in and out of the industry (modeled for awhile as the Camel Cigarette Man), when he began creating extended mixes on his own. As Mouton tells Shapiro in Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco, the idea came to him one night at a club where he was "watching these White people, really getting off on [Soul] music. And I'm really observing them and, of course, all the songs are like two and a half, three minutes long." Moulton sensed that folks would walk off the dance floor, before they really got open emotionally. Weeks later Moulton produced a 45-minute mixtape—this in the era before digital editing machines—featuring songs by Ann Peebles, Syl Johnson and the Detroit Emeralds, among others.

Eventually Moulton's tapes began to circulate to record company execs, all trying to cash in on the burgeoning Disco frenzy, by creating extended versions of their hit songs, that club DJs would find attractive. Moulton's first big success was with B.T. Express's "Do It ('Till Your Satisfied)" which was a top ten hit on the R&B, Pop, and Dance charts in 1974. It was at that time the Mouton and other also began pressing tracks on 12-inch discs; the first commercially available 12-inch was the Double Exposure classic "Ten-Percent," which was released a week before the Moulton mixed "So Much for Love" by Moment of Truth in 1976. Thereafter, records touched by Moulton would feature the tag: "A Tom Moulton Mix."

The former Camel Cigarette Man Though PIR experienced success with dance music dating back to Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, which some claim as the first Disco song, Moulton's work with the label allowed them to solidify their presence within the genre. MFSB's "Love is the Message," seemed tailored for just the kind of aural re-visioning, that Moulton specialized in. The song was the title track of the second MFSB second album. MFSB was the PIR house band (an orchestra really) featuring among others Earl Young on drums, Norman Harris and Roland Chambers on guitar, bassist Ronnie Baker, and Vince Montana on Vibes. The album featured their signature track, "T.S.O.P. (The Sound of Philadelphia)," which topped the Pop and R&B charts in 1974, though the song is most synonymous as the theme to Soul Train.

The former Camel Cigarette Man Though PIR experienced success with dance music dating back to Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, which some claim as the first Disco song, Moulton's work with the label allowed them to solidify their presence within the genre. MFSB's "Love is the Message," seemed tailored for just the kind of aural re-visioning, that Moulton specialized in. The song was the title track of the second MFSB second album. MFSB was the PIR house band (an orchestra really) featuring among others Earl Young on drums, Norman Harris and Roland Chambers on guitar, bassist Ronnie Baker, and Vince Montana on Vibes. The album featured their signature track, "T.S.O.P. (The Sound of Philadelphia)," which topped the Pop and R&B charts in 1974, though the song is most synonymous as the theme to Soul Train.Though "Love is the Message," didn't even chart in the R&B Top-40 upon its release, it was Moulton's 11-minute plus remix of the song that would take on a life of its own. As Nelson George relates in Hip Hop America (1998), "On a hot summer night in about 1977 a mobile jock with gigantic speakers and an ego to match introduced me to two records that were not just simply fly, progressive things to play, but that twenty years later, still help define hip-hop." According to George, "Trans Europe Express" and "Love is the Message" was the music "of people who voted for Jimmy Carter and feared Ronald Reagan. It was the music of people who did the Hustle on asphalt in the summer wearing Converse and espadrilles; it was the music of a city nearly bankrupt yet found millions to remodel Yankee stadium." For those who inhabited DJ Nicky Siano's Gallery in the early 1970s, according the music journalist Peter Shapiro, "Love is the Message" was the "national anthem of New York."

MFSB: Heart & Soul of PIRFor the remix, Moulton extended the "break" section that appeared on the original including recording a new Fender solo for the part. It was Leon Huff who unwittingly recorded the new electric piano solo. "Moulton wasn't just elongating records to meet the demands of the dance floor, Shapiro writes in Turn the Beat Around, he was "toying and playing with these records, using his equalizer to boost the bottom end and adding breaks to create disco extravaganzas out of three-minute pop song," a process only enhanced by the 12-inch format. Of course neither Moulton or Huff were aware of the young Black and Latino men, up in Harlem, N.Y. and the Boogie-down, who liked to spin on their heads to extended break beats like the one Moulton crafted for the remix.

MFSB: Heart & Soul of PIRFor the remix, Moulton extended the "break" section that appeared on the original including recording a new Fender solo for the part. It was Leon Huff who unwittingly recorded the new electric piano solo. "Moulton wasn't just elongating records to meet the demands of the dance floor, Shapiro writes in Turn the Beat Around, he was "toying and playing with these records, using his equalizer to boost the bottom end and adding breaks to create disco extravaganzas out of three-minute pop song," a process only enhanced by the 12-inch format. Of course neither Moulton or Huff were aware of the young Black and Latino men, up in Harlem, N.Y. and the Boogie-down, who liked to spin on their heads to extended break beats like the one Moulton crafted for the remix.The release of the Philadelphia Classics in 1977 coincided with the explosion of Disco culture into the mainstream. The genre had been incubated in the underground years before in dance clubs like the aforementioned Gallery and The Loft, where DJs like David Mancuso and later Larry Levan favored a wide range of dance music including Motown tracks like Eddie Kendricks' "Girl You Need a Change of Mind," the Afro-Funk Manu Dibango's "Soul Makoussa," and the bubble-gum girl Soul of First Choice ("Smarty Pants").

Philadelphia Classics allowed PIR to take advantage of the moment by re-issuing dance grooves were already in the can and had a proven track record. By describing the remixed tracks as Philly "classics" the label was also staking a major claim on their musical legacy. Because of the labels overall dedication to musicianship and quality vocals (though it was in decline by 1977), PIR managed to escape the ire of mainstream audiences who quickly tired of the repetitive formulas that marked much of (bad) Disco music (any one remember Dan Hartman's "Instant Replay"?).

Very often Mouton just added subtle flavors to extend the tracks, allowing for extended grooves, but also a more pleasurable listening experience. A Norman Harris guitar solo was added to the nine minute version of the O'Jays' "I Love Music" and their barely three-minute breakthrough hit "Love Train" (Backstabbers, 1972) is given a new three minute introduction. Similarly, the Mother's Day anthem "I'll Always Love My Mama" by the Intruders, was given a new three minute introduction that could stand alone musically on its own (and give jocks three full minutes to give Mother's Day shout-outs before the vocals started).

Some of the best work done on Philadelphia Classics was done in the service of Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes. Though most audiences are familiar with Thelma Houston's "chitlin n' grits" disco version of "Don't Leave Me This Way" (1977), the track was originally recorded by the Blue Notes on their classic Wake Up Everybody (1976). Perhaps in response to the break out success of the Houston's version, Moulton gives the Blue Notes' original a brand new flavor. Both versions of the Blue Note song highlight lead vocalist Teddy Pendergrass' "Marvin Junior-turned Joe Ligon" gospel sensibilities (Junior and Ligon are lead vocalists of the Dells and the Mighty Clouds of Joy, respectively).

Nowhere Moulton touch more apparent than on Pendergrass' lead on the "still-brilliant-after-all-these-years" "Bad Luck" (To Be True, 1975). Moulton simply extends the middle of the song two minutes with a string-laden groove. Moulton's remix tempers the break-neck angel dust pace of the original track, allowing audience to more fully experience and appreciate the genius of Pendergrass' closing sermon and his brilliant referencing of the Nixon Watergate proceedings. It is in that closing where Pendergrass literally screams the lyrics:

"I know none of y'all satisfied, satisfied / The way prices has been going up on things / I can barely buy a morning paper…But then early one morning I got me a paper / I sat down on my living room floor and opened it up / Guess what I saw? I saw the president of the United States / The man said he wasn't gonna give it up / He did resign / But he still turned around and left all us poor folks behind / They say they got another man to take his place / But I don't think that he can satisfy the human race."

As the song begins to fade, Pendergrass can be heard "The only thing that I got that I can hold on to is my God, my good, Jesus be with me and give me good luck, good luck." The track is unquestionably the strongest of Pendergrass' performances as a member of the Blue Notes.

While Sean Combs can legitimately talk about birthing the era of the hip-hop remix—his remix of Craig Mack's "Flava in Your Ear" had the same impact of Moulton's "Love is the Message" remix—Philadelphia Classics highlights the legacy on one of the greatest record makers of the 20th century and the man who truly invented the remix.

Published on June 24, 2011 18:36

June 23, 2011

Black Music Month 2011: Urban Soul | "The Millennium R & B"

Tags: VH1 Rock Docs, Reality TV Shows, Reality TV Shows 6

Urban Soul: The Making of Modern R&B

A film by John Akomfrah

Part Six: "The Millennium R & B"

Published on June 23, 2011 14:08

A Meeting of Walkers: Rebecca and Kara

The Root's Rebecca Walker hangs out with renowned artist Kara Walker in Turin, Italy, and on Facebook, where they talk about everything from salty dark chocolate to their kids to why Kara's no apologist for anti-black racism.

The Italian Jobby Rebecca Walker | The Root

Kara Walker is tall, fashionable and reserved when I meet her in the lobby of the chic Residence Du Parc, a brutalist landmark of poured concrete adorned with iconic examples of modernist and postmodern art. Outside huge windows, Turin is celebrating itself: Italian flags drip from every window, flutter along every boulevard.

Kara wears flat leather oxfords, tights and a paper-thin leather jacket. She eyes me somewhat warily as I extend my arms for an embrace and launch into small talk, which I normally detest. Luckily, my bags have been lost and I indulged in a truly remarkable spa treatment the night before, so I have plenty to talk about.

Kara says little. She's been working on the installation of her show we're both here in Italy to support. The necessary projectors have not arrived. The show is to open in five days, and today we have to teach a class to art students. I sense she'd like to get back to the gallery, and the class is a distraction. She twirls her hair as we wait for the taxi.

At the class, the students are on fire. They've studied our work and want to know about memory and myth, the creative process and its demands. Kara and I sit behind a paint-splattered table and do our best. I'm jet-lagged but exuberant, thanks to a piping-hot cappuccino; Kara is laconic and soft-spoken. But then I see it -- a gentle smile, then a big laugh followed by a series of confident assessments of student work.

As the day wears on, we find a groove. We tag-team it, develop a rapport, give everything we can in the time allotted. Driving back to the Du Parc to recover and prepare for dinner, we talk about our kids. Hers is starting high school, into fashion, gorgeous. Mine is 6, getting ready for soccer camp, and I miss him with an ache I can't begin to put into words.

The next five days are a whirlwind of activity. We teach the students, I present my memoir Baby Love at Il Circolo dei Lettori on the same night that Jonathan Franzen reads from Freedom. I introduce Kara's show, A Negress of Noteworthy Talent, to a full gallery, and Melissa Harris-Perry and Jennifer Richeson follow up with talks about the black body and the neurological workings of prejudice. The press descends and recommends.

Later, I steal away to the Egyptian Museum. We dine at the home of Olga Gambari, the show's remarkable curator, and shop the Ballon, one of Europe's largest open-air markets, where I snag a fabulous Prada-esque red coat for five euros and a dress made of African wax cloth for 10, while Kara snaps pics of me on her iPhone.

Read the Full Essay @ The Root

Published on June 23, 2011 07:21

June 22, 2011

Lisa Fager Bediako: Not About Rape, Not About Rihanna

Not About Rape, Not About Rihanna by Lisa Fager Bediako | Special to CNN

(CNN) -- Rihanna's "Man Down" video was the motivation for Industry Ears -- a media watchdog group I co-founded -- to recently join forces with the Parents Television Council to hold media corporations, in this case Black Entertainment Television, accountable. We argued that the graphic violence aired in the video was inappropriate for the age group that makes up nearly half of BET's "106 & Park" video show's audience: 12- to 17-year-olds.

Our concern lies not with Rihanna as an artist, but with BET and its parent company, Viacom, as purveyors of violence. Over the last several weeks, however, I have witnessed our original concern with the video become twisted from a national discussion about protecting children into one of feminist empowerment and free artistic expression.

The first moments of the "Man Down" video show a man in a crowded train station being shot in the head and falling into a puddle of his own blood. This grisly image is, to us, the most questionable part of the video.

Our suggestion to BET is that they edit the "too graphic for kids" portion of this video, roughly the opening 45 seconds. We have all seen guns, drug paraphernalia, and T-shirt logos blurred out or whole scenes edited out of music videos that appear on music channels. MTV and BET routinely require record labels to edit videos, so why not this one?

Some argue that the discovery later in the video that the man being shot is a rapist, and that the woman shooting him is his victim, makes this depiction of violence acceptable. We disagree.

In his 30 years of viewing BET, Paul Porter, Industry Ears co-founder and former BET video programmer, says he has never witnessed "such a cold, calculated execution of murder in prime time." Cable television content is not regulated like broadcast television, but most cable networks have adopted the broadcast television standard of airing sexually explicit, violent and mature content after 10 p.m. and adding disclaimers, especially if the program attracts younger viewers. "106 & Park" airs weekdays at 6 p.m.

Read the Full Essay @ CNN.com

***

Lisa Fager Bediako is president of Industry Ears and formerly worked for Capitol EMI Records, Discovery Communications, CBS radio and other entertainment media outlets.

Published on June 22, 2011 15:16

Teach for America: A Failed Vision

Teach for America: A Failed Visio nby Mark Naison | special to NewBlackMan

Every spring without fail, a Teach for America recruiter approaches me and asks if they can come to my classes and recruit students for TFA, and every year, without fail, I give them the same answer: "Sorry. Until Teach for America changes its objective to training lifetime educators and raises the time commitment to five years rather than two, I will not allow TFA to recruit in my classes. The idea of sending talented students into schools in high poverty areas and then after two years, encouraging them to pursue careers in finance, law, and business in the hope that they will then advocate for educational equity rubs me the wrong way"

It was not always thus. Ten years ago, when a Teach for American recruiter first approached me, I was enthusiastic about the idea of recruiting my most idealistic and talented students for work in high poverty schools and allowed the TFA representative to make presentations in my classes, which are filled with Urban Studies and African American Studies majors. Several of my best students applied, all of whom wanted to become teachers, and several of whom came from the kind of high poverty neighborhoods TFA proposed to send its recruits to teach in.

Not one of them was accepted! Enraged, I did a little research and found that TFA had accepted only four of the nearly 100 Fordham students who applied. I become even more enraged when I found out from the New York Times that TFA had accepted 44 out of a hundred applicants from Yale that year. Something was really wrong here if an organization who wanted to serve low income communities rejected every applicant from Fordham who came from those communities and accepted half of the applicants from an Ivy League school where very few of the students, even students of color, come from working class or poor families.

Never, in its recruiting literature, has Teach for America described teaching as the most valuable professional choice that an idealistic, socially conscious person can make, and encourage the brightest students to make teaching their permanent career. Indeed, the organization does everything in its power to make joining Teach for America seem a like a great pathway to success in other, higher paying professions.

Three years ago, the TFA recruiter plastered the Fordham campus with flyers that said "Learn how joining TFA can help you gain admission to Stanford Business School." To me, the message of that flyer was "use teaching in high poverty areas a stepping stone to a career in business." It was not only profoundly disrespectful of every person who chooses to commit their life to the teaching profession, it advocated using students in high poverty areas as guinea pigs for an experiment in "resume padding" for ambitious young people.

In saying these things, let me make it clear that my quarrel is not with the many talented young people who join Teach for America, some of whom decide to remain in the communities they work in and some of whom become lifetime educators. It is with the leaders of the organization who enjoy the favor with which TFA is regarded with captains of industry, members of Congress, the media, and the foundation world, and have used this access to move rapidly to positions as heads of local school systems, executives in Charter school companies, and educational analysts in management consulting firms.

The organization's facile circumvention of the grinding, difficult but profoundly empowering work of teaching and administering schools has created the illusion that there are quick fixes, not only for failing schools, but for deeply entrenched patterns of poverty and inequality. No organization has been more complicit than TFA in the demonization of teachers and teachers unions, and no organization has provided more "shock troops" for Education Reform strategies which emphasize privatization and high stakes testing. Michelle Rhee, a TFA recruit, is the poster child for such policies, but she is hardly alone. Her counterparts can be found in New Orleans ( where they led the movement toward a system dominated by charter school) in New York ( where they play an important role in the Bloomberg Education bureaucracy) and in many other cities.

And that elusive goal of educational equity. How well has it advanced in the years TFA has been operating? Not only has there been little progress, in the last fifteen years, in narrowing the test score gap by race and class, but income inequality has become greater, in those years, than any time in modern American history. TFA has done nothing to promote income redistribution, reduce the size of the prison population, encourage social investment in high poverty neighborhoods, or revitalize arts and science and history in the nation's schools. It's main accomplishment has been to marginally increase the number of talented people entering the teaching profession, but only a small fraction of those remain in the schools to which they were originally sent.

But the most objectionable aspect of Teach for America–other than its contempt for lifetime educators—is its willingness to create another pathway to wealth and power for those already privileged, in the rapidly expanding Educational Industrial Complex, which offers numerous careers for the ambitious and well connected. An organization which began by promoting idealism and educational equity has become, to all too many of its recruits, a vehicle for profiting from the misery of America's poor.

***

Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies and History at Fordham University and Director of Fordham's Urban Studies Program. He is the author of three books and over 100 articles on African-American History, urban history, and the history of sports. His most recent book White Boy: A Memoir, published in the Spring of 2002.

Published on June 22, 2011 12:28

Why Clarence Clemons Matters to Race Relations

Why Clarence Clemons Matters to Race Relations by Ben Mankiewicz | Huffington Post

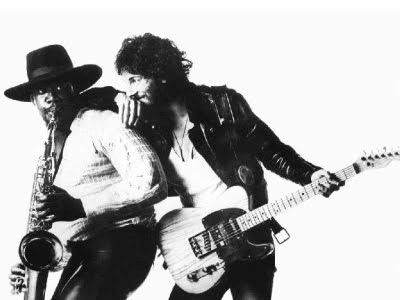

Iconic is a wildly overused word, but the cover photo of Born to Run -- Bruce Springsteen grinning and leaning on Clarence Clemons' broad shoulder -- is a powerful and memorable picture, one that meets the standard for iconic rock n' roll images. And its status is rooted in the beautiful story that picture tells.

You've got this enormously talented, giant black man -- literally "The Big Man" -- saxophone between pursed lips, essentially supporting Springsteen. The look on Bruce's face is honest and authentic, a genuine moment captured in a photo shoot. There's a giddiness in Bruce's smile: "I'm working with my friend," he seems to be saying, "and our music has never been better."

The photo made an instant impact on me, long before their music did.

I was eight when Born to Run was released and that image meant a hell of a lot more to me than anything my teachers could tell me about race. It sealed a point my brother Josh, now a Dateline correspondent, made a few years earlier.

This is an embarrassing story, one I'm hesitant to tell, but remember, I was five years old. We were playing Nerf basketball with Josh -- who is 12 years older -- on his knees so we'd be close to the same height. He blocked my shot or stole the ball or otherwise foiled one of my vintage mid-70s Elvin Hayes Washington Bullets moves. And then I called him an N-word. I'd clearly heard it at school and recognized it as an insult. I had no earthly idea what it meant, but boy was I about to find out.

Within milliseconds Josh was up off his knees, hands grasping my shoulders, picking me up and placing me on the bed. "You never, ever say that to anyone," he said. "That's something very bad white people say to black people when they want to be mean on purpose. It's about the worst thing you can say." I remember crying hysterically at this point because my brother never yelled at me, which could only mean I had done something seriously wrong.

When I had calmed down, I remember asking him about the equivalent, what does a bad black person say to a white person? "There really isn't one," he said, refusing to simplify a complicated issue. "They might say 'honky,' but it's really not the same thing."

Since I still remember the conversation roughly 35 years later, I'd say my brother's "teaching moment" was successful.

And three years later -- on the cover of one of the greatest albums ever released, one of the first records I owned -- was the next step in my education about race relations in America, a shot of a black guy and a white guy, clearly good friends, working together to make something great.

Critically, it delivered a subtle lesson to impressionable young rock n' roll fans. Nobody was beating us over the head with a mallet of racial unity. It's not that those messages shouldn't have been delivered, but kids have a tendency to tune out words of wisdom from overly earnest After School Specials. Instead, you had Clarence playing his sax and Bruce somewhere between a knowing smile and laughing, conveying a sense that this friendship between black and white, this artistic collaboration, wasn't such big a deal.

Being told that black people and white people were equal was one thing. Being shown it was something else.

When Born to Run solidified Bruce as one of the great artists of his generation, the photo took on even more symbolism. The second single from album is "Tenth Avenue Freeze Out" (Number 4 on my list of the Top 25 Springsteen songs, compiled last fall), which Bruce regularly calls "the story of the E Street Band." It's a joyful song, brimming with optimism, and it has one of the lines that matters most in the Springsteen catalog, words that regularly draw thunderous cheers in concert, "When the Change Was Made Uptown and the Big Man Joined the Band."

Obviously, Clarence's impact on the band will last forever. And his impact on how I -- and others, I'm sure -- view race in America will last a lifetime.

***

Ben Mankiewicz is host, Turner Classic Movies.

Published on June 22, 2011 12:10

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.