Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1080

June 11, 2011

Black Music Month 2011: Staple Singers | When Will We Be Paid...

The Staple Singers live in Ghana (1971)

Published on June 11, 2011 14:05

Black Music Month 2011 | High Negro Style: The Motown Visual Effect

Motown's impact on American music is well known, but the label was also significant for introducing to the world to "High Negro Style"

High Negro Style: The Motown Visual Effect by Mark Anthony Neal

When Berry Gordy founded Motown records in January of 1959, his efforts were little more than a hunch and a hustle. At the time Gordy could not have imagined that his little Detroit-based record company would go on to produce some of the most timeless music of the 20th century. For all of the two-and-a-half minute classics that came off the label's automobile-like assembly line, there is perhaps no more endearing tribute to Motown than the image of upscale sophistication that so many of the label's artists embodied during the 1960s. Motown's "High Negro Style" as former Motown President Andre Harrell would term it, is on full display on the recent release Motown the DVD: Definitive Performances.

Harrell took over the helm of Motown Records in 1995 when the label was well removed from its peak as one of the premier record companies in the country. Harrell was faced with the daunting, and ultimately unsuccessful, task of making the label relevant to an industry that had long passed it by. For many, the label had become strictly a back catalogue brand, most valuable for the potential of endlessly repackaging Motown's many classic recordings and artists. Though the label boasted the talents of the platinum selling group Boyz II Men on its roster at the time—Harrell's tenure with the label coincides with the beginning of the group's descent from the top of the pop charts—the label's most notable commodity was its tradition and that back catalogue.

To his credit, Harrell understood the value of that tradition and began to place his own stamp on the aging brand as an example of what he called "High Negro"—upscale, urban, urbane and just enough ghetto to remind you that the Detroit housing projects supplied Motown with more than enough talent in the early 1960s. "Ghetto glamour," as Harrell described "High Negro" style in a 1995 cover story for New York Magazine," would have been incomprehensible for those audiences who flocked to Motown performances in the 1960s. There's no denying though, that just below the sheen of respectability and mainstream acceptance that Gordy craved, were the gritty realities of the social world that made his hustle palpable.

In the 1960s as television had emerged as a particularly volatile site for representations of blackness, images of black civil rights workers clashing with southern segregationists often competed with images of uplift like Dianne Carroll's Julia, a nattily dressed Nat King Cole and the athletic grace of Willie Mays and Hank Aaron. Gordy understood these dynamics better than most, so for many of those first generation of Motown acts, the label, was among other things, a finishing school. In addition to the intricately choreographed Cholly Atkins stage routines, there were etiquette classes. As critical as the rhythm tracks laid down by the Motown's famed backing musician, The Funk Brothers were to Motown's success in the 1960s, was making White people comfortable with the Black bodies that emboldened the brand was as critical to Motown's success

Motown the DVD captures some of the tensions that accompanied Gordy's attempts to conquer the pop music world. The Contours 1962 appearance on The Hy Lit Show is instructive. Singing "Do You Love Me?"—a song that would be prominently featured twenty-five years later in the film Dirty Dancing—the quartet seems particularly challenged not to engage in the very "dirty dancing" that the song inspired. Only a few years after Elvis Presley's swiveling hips would court controversy on television, America was not quite ready to see black men doing the same. In comparison, the Temptations' tightly choreographed routines during their 1964 performance of "My Girl" on Teen Town is a lesson in restraint. "My Girl" was the group's first major pop hit, and Gordy was understandably cautious in his approach.

When the voluptuous Brenda Holloway appeared on Shivaree in 1964, it was the camera that seemed confused. The camera was still focused on the white Go-Go dancers that were featured weekly, while Holloway was well into the first verse of "Every Little Bit Hurts," seemingly reluctant about presenting Holloway in her sleeveless leather cat suit. Even when the camera finally settles on Holloway's figure, albeit briefly, it seems confused as to whether to present a head-shot or a full body view, Holloway's rather ample hips in tow.

Many of the performances included on Motown the DVD, were lip-synced, highlighting many of the technical issues that producers were faced with when trying to present musical performances via the still evolving medium. Not all of the teen music programs in the era, for example, had production budgets that would allow them to feature live musicians and alternately, many of the fledgling records labels of the era couldn't afford to hire musicians for one-time appearances. For Gordy such canned performances were useful, because they helped guarantee that the label's artists would reproduce the very performances that record buyers were familiar with.

The performances of Martha Reeves and the Vandellas and The Supremes on The Ed Sullivan Show—the premiere weekly variety show throughout the 1950s and 1960s—and The Mike Douglass Show offer a contrast to the many of the lip-synced performances. Despite having a reputation for possessing a rather saccharine voice, Supremes lead Diana Ross more than makes up with her star power during the group's performance of "Back in My Arms Again." And none of made the Motown sound "pop" was lost when the Vandellas donned full-length gowns in front of Sullivan's house orchestra.

Motown the DVD includes additional footage of the company picnic in 1970, that is as notable for the moments it captures the label's biggest stars—Diana Ross, Smokey Robinson, Marvin Gaye and a young Michael Jackson—alongside the rank-and-file types that were the essence of the operation as it is for the comical narration of then Motown staffer Weldon McDougal III. For all of the label's achievements, the footage of the picnic is a reminder that above all else, Motown always saw itself as a family.

Published on June 11, 2011 08:49

Eddie Long, Creflo Dollar, and the Black Church's Sanctioning of Sexual Violence

Eddie Long, Creflo Dollar, and the Black Church's Sanctioning of Sexual Violence by Tamura A. Lomax | The Feminist Wire

In September 2010 Bishop Eddie Long, prominent Atlanta pastor of New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, was accused of sexual improprieties with four young men—Anthony Flagg, Spencer LeGrande, Jamal Parris and Maurice Robinson. According to the suits, Long, an internationally known televangelist who had previously campaigned against gay and lesbian marriage, used his position, extravagant trips, including overseas, and lavish gifts such as housing, clothes, jewelry and cars, to coerce the young men into having sex while they were teenagers. Initially, the powerful megachurch leader denied all charges. However, as time progressed and more and more evidence was revealed, Long agreed to settle out of court for an alleged $25 million.

Obviously, this story has garnered quite a bit of media, academic, social network and water cooler attention. The reasons are many. For years Long, who once boasted about having more than 25,000 members, running an international corporation, pastoring a multimillion dollar congregation and "dealing with the White House," functioned more like a towering rock-star CEO than a church pastor. If driving through Atlanta or simply flipping through television stations, you were sure to catch a glimpse of his chiseled physique and dramatic form fitting flair. Almost always flanked by secret service like bodyguards and draped in a display of his riches, Long seemed infallible. He was indeed a [preacher] man's [preacher] man in a significantly paternalistic culture. Thus, the world seemed to sit in attention at his feet for a while—well, at least 25,000 world citizens.

When Longs' story of sexual impropriety first broke, many excitedly rushed to find a locale for judgment. Surely, someone was to blame. Some thought wrongdoing rested squarely on the shoulders of Long. Others vexingly believed the young men (and their mothers) were to blame—because they obviously "wanted it" (and because real—heterosexual—men wouldn't allow same sex encounters). However, what many failed to realize is that contemporary Black Church culture, which serves as a significant site of history, community, spirituality, hope and transcendent possibilities for many including myself, creates a context for unchecked phallocentric lordship, which often sanctions rampant sexual violence, to include but not limited to physical, emotional, psychological, linguistic and representational. (Yes, sexual violence is more than the physical act of rape, and yes I am naming what happened between Long and the teenagers as violent. Sacred trust between an adult pastor (and others) and teenaged parishioners was broken.) Thus, there is plenty of blame to go around, for it was New Birth members who gave Long the kind of totalitarian authority that he had. Nevertheless, while sexual violence is communally ratified, the onus lies primarily with Long himself.

Read the Full Essay @ The Feminist Wire

Published on June 11, 2011 08:02

June 10, 2011

Adam Mansbach Talks 'Go the **** to Sleep' on The Today Show

Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

Published on June 10, 2011 07:46

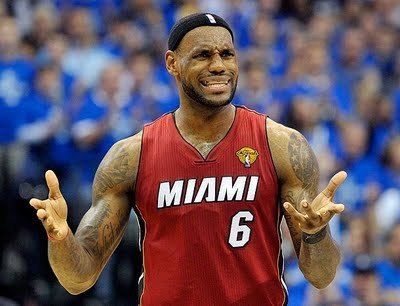

LeBron James and the Redemptive Path to Nowhere

LeBron James and the Redemptive Path to Nowhere by David Leonard and Bruce Lee Hazelwood | special to NewBlackMan

As Game 4 of the 2011 NBA Finals came to a close on another last second shot, Dwyane Wade and Dirk Nowitzki were praised for carrying their respective teams. The celebration of Nowitzki has been especially robust given his reported illness, a fact that has been used to celebrate his performance as heroic, as a sign of his toughness, and as evidence of his talents as a leader.

LeBron James, on the other hand, endured another bout of criticism from fans, media, and players alike. After Game 3, where LeBron had a stat line that included 17 points, 9 assists and 3 rebounds, Greg Doyle asked LeBron about his "shrinking" in the 4th quarter. Notwithstanding LeBron's dismissal of the question, Doyel maintained this line of criticism in his column the following day, writing:

When someone makes a movie of the fourth quarter, they can cast Rick Moranis as LeBron James and call it Honey, I Shrunk the Superstar.

That's what I'll remember about James from Game 3. His shrinkage, and how it continued a series of shrinkages. I asked him about that after Game 3. I asked him, pretty much word-for-word, how come he hasn't been playing like a superstar in the fourth quarter? What's going on with that? James played the defensive-stopper card. That's why he's out there, you know. For his defense. He's not a latter-day Michael Jordan. He's a latter-day Dudley Bradley.

Doyel proceeds to criticize James for "complaining" to referees, whining, and otherwise having a "bitter-beer face" when he doesn't get his way on the court, only to conclude his article by highlighting an instance where James didn't get a foul call not because there was a foul but because he isn't a superstar: "Maybe the officials are onto something. Maybe LeBron James isn't a superstar. If the 2011 NBA Finals were the only games I had seen him play, that would be my conclusion. Doyel, especially after Game 4, is not alone in his criticism. Jordan Shultz, in " LeBron James Shows True Colors In Game 4 Disappearance " identifies his Game 4 struggles are not an aberration but evidence of his ineptitude and shortcomings as a player: "Wade is in essence, everything James is not. He has the will, the fire and the assassin's nature that LeBron lacks."

This criticism is nothing new and demonstrates how LeBron James cannot win. In wins (Game 3) and losses (Game 4), he has been reduced to a failure, a punching bag for America's sports punditry. Ever since the ill-fated "Decision," praise for James seems to shrink every day while criticism of his game continues to overshadow his contributions to his team. In a season where perception is James is "on the road to redemption," questions need to be asked. How can redemption be gained if he can do no right? Who is LeBron James really redeeming? And in the end, is LeBron James really trying for redemption?Since joining the Heat, James has faced criticism at both ends of the spectrum: go for 35-12-10 and he's hogging the ball, but go 15-9-8 and he isn't doing enough. With Wade and Chris Bosh on the team, he either doesn't involve the other two superstars enough or defers to them too much. He is the walking embodiment of the longstanding criticism that has always plagued black athletes living amid American racism: too selfish or unable to lead. This highlights the power of the white racial frame, one that renders black bodies as undesirable and suspect, with the impossibility of redemption. In that James will face criticism irrespective of his on-the-court performance – if he shoots the last shot and misses, he lacks the "killer instinct"/ he is selfish and should have passed the ball to Wade (this was a criticism after Game 2 where James was questioned for not deferring to Wade who had it going); if he passes the ball, he is depicted as mentally weak, scared, and otherwise unable to lead.

What is underlying much of this criticism is a false comparison to a reimagined Jordan. The nostalgia for Jordan as post-racial, as team player, as unselfish, and as God-like illustrate the impossibility of James meeting these expectations. Whereas Jordan in retirement has been reconstituted as a leader, as a fundamentally perfect player who was driven by team success and not individual accomplishment, James, as an embodiment of Thabiti Lewis' "baller of new school," has no possibility of becoming the next Michael Jordan. Given the ways in which black players are scolded and demonized for ego, James, despite his unselfishness, despite his willingness to defer to Wade, pass to Chris Bosh, and set-up Mario Chalmers is unable to transcend the confined meaning of blackness. In actuality, in 2011, Michael Jordan likely couldn't be the next Michael Jordan.

More than his "struggles" on the court, James cannot win because he cannot be Michael Jordan. And he cannot be Michael Jordan because LeBron does not fulfill a post-racial fantasy. LeBron does not embody what David Falk celebrated in Michael Jordan: "When players of color become stars they are no longer perceived as being of color. The color sort of vanishes. I don't think people look at Michael Jordan anymore and say he's a black superstar. They say he's a superstar. They totally accepted him into the mainstream. Before he got there he might have been African American, but once he arrived, he had such a high level of acceptance that I think that description goes away."

His tattoos, his decision to hire his longstanding friends to guide his career, "The Decision," his insertion of race into the post-Cavs discourse, his acceptance of the anti-hero role, his "What should I do?" Commercial for Nike, and even his response to Greg Doyel where he told him to "watch the film again" so he could "ask me a better question tomorrow" all contribute to a path not paved by Jordan toward racial redemption but one more travelled by many black athletes: one of derision, contempt, criticism, and scrutiny. "The irony of the connection between Willie Horton, O.J. Simpson, and Tookie Williams, and Michael Jordan, LeBron James, Allen Iverson, and Latrell Sprewell, along with most of the black NBA superstars of today is that, as easily as the first three, like so many countless criminalized black male bodies in the United States are denied social and moral redemption because of their race, their presumed inherent transgression, and the need of the American public to reify much of its racist (il)logic," writes Lisa Guerrero from Leonard and King's Criminalized and Commodified . While LeBron as member of the Cavs, as a potential savior (of the NBA; of the Jordan legacy; of Cleveland) had the potential to "redeem us, to maintain our sense of ourselves as a nation that is righteous, equal, and free, and to allow us to continue dreaming the American Dream," that potential is gone. The narrative of his "failure" redeems us; the hegemonic claims about the righteousness of others and the steps LeBron must take to be saved is a celebration of the system not him.

In terms of the second question – is this his "road to redemption"—we must be clear. LeBron James appears to be disinterested in redeeming himself – a central perquisite in the history of race in America. The parameters of his redemption have been set not by James but by the media and fans. With this in mind, it then becomes impossible for James to gain redemption in the public eye because he will never buy into the parameters set before him. LeBron James is in the continuous struggle of playing by his rules on a court/in a society where everyone but him is setting the rules of the game. Worse, yet, the rules change with each game. "If, as today's writers lament, LeBron doesn't want to take over the game, that should be praised, not derided," writes Dave Zirin . "Basketball at its best is a beautiful game: a team game. As long as LeBron keeps playing the game as it comes, he will be a champion. He doesn't have to settle for being the next Jordan." Irrespective of whether he takes over a game or not, James will be criticized because he can't be "like Mike" – on the court, maybe, but in the national imagination, never!

For LeBron James, there is no need for redemption. In his eyes, he did what he wanted to do and there is no regret. He wanted to play with his friends and he ended up signing with a team allowing him to do this. While many black athletes strive to reach the summit of Jordan-like acceptance, they fail to see even what Jordan failed to see: no matter what they do or how much money or how many endorsement deals they sign or how they make their respective leagues profitable with immense cultural capital, they are still black bodies in America. James made clear last year that there is little he can do to redeem himself as Michael Jordan. In his "Rise" Nike Commercial, he asks,

What should I do? Should I tell you I'm a championship chaser? I did it for the money, rings?Maybe I should just disappear

As evident in LeBron's inability to outrun the leadership and selfish trope that defines America's sports racial history and thus his inability to find solace on a path to redemption, there is nothing LeBron can do. His experiences demonstrate that so long as (white) fans and (white) commentators resent his talent, his choices, his attitude, his swagger, his motivations, his blackness, he is dammed. Not only cannot he not be Michael Jordan or as good as Michael Jordan (sorry Scottie Pippen) in the national imagination but he will continue to face a barrage of criticism for his every move. The black body is continuously subjected to mainstream notions of what it means to be black in a white society all while managing how and working to control those same bodies. Championships or not; 45 points or 8; 25 assists or 2, LeBron James will forever be remembered with the sentence, "Yeah, LeBron could ball, but…"

Post-script

Despite securing a triple double in game 5, the criticisms directed at LeBron continue to mount. Described as hallow, disinterested, quiet, and otherwise ineffective, securing the 29th triple double in NBA final history did little to silence those critics who continued to focus on his leadership and play in "clutch minutes." Treating the 4th quarter like a game of "Hot Shot," where the points are worth double, these critics ignores LeBron's success throughout the game in an effort to undercut his contributions all while advancing a narrative about his lack of leadership, mental toughness, and "the clutch gene." Makes one wonder what the critics would say if he did not score, rebound or get his teammates for the first 42 minutes of the game only to amass 17-10-10 in the final 6 minutes.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor of Comparative Ethnic Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press).

Published on June 10, 2011 07:06

June 9, 2011

Trailer: 'Thunder Soul' feat Director Mark Landsman | #BMM 2011

Reelblack had a chance to chat briefly with filmmaker MARK LANDSMAN. The AFI grad's award winning debut feature, THUNDER SOUL, is an amazing tribute to Prof. Johnson and the Kashmere Stage Band. Thunder Soul hits theaters on September 23, 2011, presented by Jamie Foxx.

Most fans of classic soul and funk don't spend much time listening to high school bands, but mention the Kashmere Stage Band and they'll sit up and take notice. In the 1970s, the jazz band at Houston, Texas's Kashmere High School was one of the best in the nation, and even scored regional hits with their recordings. Comprised of students from one of Houston's roughest neighborhoods, the Kashmere Stage Band was the brainchild of Conrad O. Johnson Sr., the school's band director who replaced the band's staid repertoire with a mix of lively jazz and funk tunes and current R&B favorites, and instilled a powerful work ethic in his students that turned the ensemble into award winners.

www.thundersoulmovie.com Kashmere Satge Band music available on Stones Throw records.

Published on June 09, 2011 21:23

Why President Obama Must Remove Arne Duncan As Secretary of Education

Why President Obama Must Remove Arne Duncan As Secretary of Education by Mark Naison | special to NewBlackMan

The 2008 Election Campaign of Barack Obama inspired a spirit of sacrifice and idealism that I had not seen among close friends since the early days of the Civil Rights Movement. My upstairs neighbors, both in their mid 70's, camped out in Virginia a week before the election to help get out the vote in that state. My best friend and his wife did the same in Florida. At least ten people in my circle took regular trips to Pennsylvania and Ohio on weekends to help move those "swing states" into the Democratic camp. And my dear friend Rich Klimmer, now deceased, spent three months in a hotel room in Philadelphia, while undergoing dialysis three times a week, coordinating the labor campaign for Obama in Pennsylvania.

What did all these people have in common, other than a passion to elect the first African American president in American History?

Every single one of them were college professors or public schools teachers. No group worked harder for Barack Obama's election than America's teachers, who not only contributed funds to his campaign, but were the campaign's most effective "grunt workers," doing everything possible to reach voters in swing states, whether by participating in phone banks or by travelling long distances to reach voters door to door.

Today, America's teachers stand so disillusioned with the Obama Administration that their participation in the 2012 is a big question mark. Teachers I know may ultimately vote for Barack Obama, but they will do so only because they fear the Republican candidate will do more damage, not because they think the Obama Administration's policies are moving the nation in the right direction. When it comes to education policy, most teachers and professors see the Obama administration as promoting national initiatives which strip teachers of their autonomy, make them scapegoats for the nation's problems, and promote formulas for assessing teacher quality that will, if accepted, reduce instruction at all levels to memorization and test prep. They are very likely to sit out the next Presidential campaign unless the Administration switches gears and embraces a teacher centered strategy for improving American's schools and universities.

But to do that, President Obama will have to remove the Harvard trained lawyer who runs the US Department of Education, Arne Duncan. Not only does Duncan promote policies which force schools and universities make testing and assessment a far more significant part of classroom learning, in his comments to the press and elected officials, he literally oozes contempt for teachers and school administrators. In Arne Duncan's field of vision,, America's schools and universities are islands of backwardness and inefficiency in a dynamic society where competition produces excellence and those who can't compete lose their jobs. Obsessed with quantifying success and punishing failure, he is on a mission to turn every dimension of classroom learning, from kindergarten through graduate school, into something that can be measured and evaluated with the simplicity and clarity of sales figures in a bank or corporation, thereby allowing for ironclad measures of teacher evaluation on a national scale.

When anyone suggest that teaching involves more than preparing students for tests, and involves characteristics likes nurturing, mentoring and character building, or involves stimulating imagination and creativity, Duncan responds with impatience and contempt. He sees himself as single handedly driving the nation towards educational competiveness by shaking up the nation's teachers,, made soft by tenure and union protections, and forcing them to be as success driven and fearful as those who work in the private sector.

While Duncan's approach has succeeded in making teachers angry and fearful, nowhere has it improved the nation's schools. The strategic mix of school closings, teacher assessment protocols based on student test results, and the closing of "failing" schools, mandated by No Child Left Behind has not raised tests results in a single major urban school district, nor has it brought new idealism and energy to teaching and learning. Instead it has enraged teachers, confused administrators, and led to protests by students and parents who feel that their input has been erased by the national formulas that determined a larger and larger portion of school policies.

On the University level, Duncan has forced rating agencies like Middle States to require assessment protocols that vastly simplify what goes on in college classrooms and strip faculty members of powers of peer evaluation that have been in place since the 1960's. The same obsession to find out if teachers have been "successful" according to a one size fits all formula, forced down the throat of local school districts through the financial incentives of Race to the Top, has been forced on universities through the threat of the cutting off of federal funding. As a result, faculty members throughout the country have been forced to used a language in evaluating their work that has no standing or credibility in their discipline ( what "outcomes" and "goals" would one measure in a course on Greek philosophy or Hip Hop Dance) and violates every norm of academic freedom that faculty members have fought for since the McCarthy Era.

The negative effect on teacher morale of such policies is well documented, but they have also started to inspire resistance. All over the nation, teachers are taking to the streets to resist attacks on their autonomy and professional status, and university professors are starting to mobilize against the threat posed to academic freedom and departmental self-governance by nationally designed and enforced assessment protocols. Everywhere you go in this country, the name Arne Duncan inspires outrage, not only among teachers, and college professors, but among school administrators and college presidents

If President Obama has any hope of being re-elected in 2012, he'd better pay attention to this groundswell of outrage and replace Arne Duncan with a Secretary of Education who shows more greater respect for the idealism, creativity and hard work of a group that played a central role in his 2008 campaign—America's Teachers

***

Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies and History at Fordham University and Director of Fordham's Urban Studies Program. He is the author of two books, Communists in Harlem During the Depression and White Boy: A Memoir. Naison is also co-director of the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). Research from the BAAHP will be published in a forthcoming collection of oral histories Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life From the 1930's to the 1960's.

Published on June 09, 2011 08:19

Africa and the World | A Film Project by Tukufu Zuberi

A Message from Tukufu Zuberi

We are reaching out to our friends and fans to help create a unique film documentary entitled Africa and the World that is designed to give American and international audiences fresh insight into Africa's past, present, and future.

The journey to create Africa and the World began several years ago when I interviewed my father about our family history just prior to his death. The discovery that his grandfather came from "somewhere in Africa" (my father didn't know where) fueled my desire to understand on a deeper and more personal level the continent I have studied most of academic life. Blending a personal quest with a scholarly vision and understanding, I hope to place the people and events of modern Africa within their full historical and social context.

But as M. Mead once said, "Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has." We need you to be a part of the small group that will enable us to make this game-changing film.

Check the Africa & the World KickStarter site.***

Tukufu Zuberi is the Lasry Family Professor of Race Relations, Professor and Chair of the Department of Sociology, and the Faculty Associate Director of the Center for Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Tukufu Zuberi is popularly known as a host on the hit Public Broadcasting System (PBS) series The History Detectives, which regularly shows the way individual objects can serve as a lens into the past.

Published on June 09, 2011 08:10

June 8, 2011

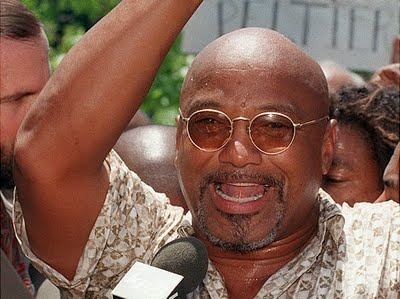

Remembering Geronimo Pratt

Remembering Geronimo Pratt by Bakari Kitwana | NewsOne

Political activists around the country are still absorbing the news of Geronimo ji Jaga's death. For those of us who came of age in the 80s and 90s, the struggles of the late 1960s and early 1970s were in many ways a gateway for our examination of the history of Black political resistance in the US. Geronimo ji Jaga (formerly Geronimo Pratt) and his personal struggle, as well as his contributions to the fight for social justice were impossible to ignore. His commitment, humility, clear thinking as well as his sense of both the longevity and continuity of the Black Freedom Movement in the US all stood out to those who knew him.

I interviewed him for The Source magazine in early September 1997 about three months after he was released from prison, having served 27 years of a life sentence for a murder he didn't commit. Three things stood out from the interview, all of which have been missed by recent commentary celebrating his life and impact.

First that famed attorney Johnnie Cochran was not only his lawyer when ji Jaga gained his freedom, but also represented him in his original trial. They were from the same hometown and, according to ji Jaga, Cochran's conscious over the years was dogged by the injustice of the US criminal system that resulted in the 1970 sentence. Second, according to ji Jaga, he never formally joined the Black Panther Party. As he remembered it, he worked with several Black activist organizations and was captured by the police while working with the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. And finally, his analysis of the UCLA 1969 shoot-out between Black Panthers and US Organization members that led to the death of his best friend Bunchy Carter and John Huggins is not a simple tale of Black in-fighting. Now is a good time to revisit all three.

Misinformation is so much part of our current political moment, particularly as the 24-hour news cycle converges with the ascendance of Fox News. In this climate, the conservative analysis of race has been normalized in mainstream discourse. This understanding of racial politics, along with the election of Barack Obama and a first term marked by little for Blacks to celebrate, makes it a particularly challenging time to be politically Black in the United States. Ask Jeremiah Wright, Shirley Sherrod, and Van Jones—all three serious advocates for the rights and humanity of everyday people whose critiques of politics and race made them far too easily demonized as anti-American.

If we have entered the era where the range of Black political thought beyond the mainstream liberal-conservative purview is delegitimized, Geronimo ji Jaga's life and death is a reminder of our need to resist it.

EXCERPTS FROM THE 1997 INTERVIEW:How did you get involved with the Black Panther Party?

Technically I never joined the Black Panther Party. After Martin Luther King's death, an elder of mine who was related to Bunchy Carter's elder and Johnnie Cochran's elder requested that those of us in the South that had military training render some sort of discipline to brothers in urban areas who were running amuck getting shot right and left, running down the street shooting guns with bullets half filled which they were buying at the local hardware store. When I arrived at UCLA, Bunchy was just getting out of prison and needed college to help with his parole. We stayed together in the dorm room on campus. But we were mainly working to build the infrastructure of the Party.

You ended up as the Deputy Minister of Defense. How did that come about?

They did not have a Ministry of Defense when I came on the scene. There was one office in Oakland and a half an office in San Francisco. I helped build the San Francisco branch and all of the chapters throughout the South—New Orleans, Dallas, Atlanta, Memphis, Winston-Salem, North Carolina and other places. We did it under the banner of the Panthers because that's what was feasible at the time. Because of shoot-outs and all that stuff, the work I did with the Panthers, overshadowed the stuff that I did with the Republic of New Afrika, the Mau Mau, the Black Liberation Army, the Brown Berets, the Black Berets, even the Fruit of Islam—but I saw my work with the Panthers as temporary. When Bunchy was killed, the Panthers wanted me to fill his position [as leader of the Southern California chapter]. I didn't want to do it because I was already overloaded with other stuff. But it was just so hard to find someone who could handle LA given the problems with the police. So I ended up doing it, reluctantly. And this is how I ended up on the central committee of the Black Panther Party. I never took an oath and never joined the Party.

What was your role as Deputy Minister of Defense?

The Ministry of Defense was largely based on infrastructure: cell systems in the cities; creating an underground for situations when you need to get individuals out of the city or country. When you get shot by the police, you can't be taken to no hospital. You gotta have medical underground as well. That's where the preachers, bible school teachers and a lot of others behind the scenes got involved. When Huey got out of prison in 1970, this stuff blew his mind.

What were the strengths and weaknesses of the Party?

The main strength was the discipline which allowed for a brother or sister to feed children early in the morning, go to school and P.E. classes during the day, go to work and selling papers in the afternoon, and patrol the police at night. The weak points were our naiveté, our youth, and the lack of experience. But even at that I really salute the resistance of the generation! I have a problem saying it was just the Panthers `cause that's not right. When you do that you x-out so much. There was more collective work going on than the popular written history of the period suggests. And when you talk about SNCC you are talking about a whole broader light than the Panther struggle. So you have to talk about that separate—that's a bigger thing. They gave rise to the intelligence of a whole bunch of Panthers.

What was Bunchy Carter like?

He was a giant, a shining prince. He had been the head of the Slausons gang. He was transforming the gangbangers in Los Angeles into that revolutionary arm. He was my mentor. Such a warm and lovable, brainy brother. At the same time he was such a fierce brother. He was very dynamic—he was an ex-boxer, and he was even on The Little Rascals probably back in the fifties. His main claim to fame was what he did with the gangs in the city. And that was a monumental thing. All that was before Bunchy became a Panther.

Because of the death of Bunchy Carter as a result of the Panthers' clash with Maulana Karenga's US organization, even today rumors persists that Dr. Karenga was an informant. . .

Not true. Definitely not true.

What was the Panther clash with US all about?

We considered Karenga's US organization to be a cultural-nationalist organization. We were considered revolutionary nationalist. So, we have a common denominator. We both are nationalist. We never had antagonistic contradictions, just ideological contradictions. The pig manipulated those contradictions to the extent that warfare jumped off. Truth is the first casualty in war. It began to be said that Karenga was rat, but that wasn't true. The death of Bunchy and John Huggins on UCLA campus was caused by an agent creating a disturbance which caused a Panther to pull out a gun and which subsequently caused US members to pull out their guns to defend themselves. In the ensuing gun battle Bunchy Carter and John Huggins lay dead.

What's your worst memory of the 27 years you spent in prison?

I accepted the fact that when I joined the movement I was gonna be killed. When we were sent off to these urban areas we were actually told, "Look, you're either gonna get killed, put in prison, or if you're lucky we can get you out the country before they do that. Those are the three options. To survive is only a dream." So when I was captured, I began to disconnect. So it's hard to say good or bad moments because this is a whole different reality that had a life of its own.

Many people would say that during those twenty-seven years that you lost something. How would you describe it?

I considered myself chopped off the game plan when I was arrested. But it was incumbent upon me to free myself and continue to struggle again. You can't look back twenty-seven years and say it was a lost. I'm still living. I run about five miles every morning, and I can still bench press 300 pounds ten times. I can give you ten reps (laughter). Also I hope I'm a little more intelligent and I'm not crazy. It's a hell of a gain that I survived.

What music most influenced you during that time?

In 1975 I heard some music on a prison radio. I hadn't seen a television in six years until about 1976, and it was at the end of the tier. I couldn't see it unless I stood up sideways against the bars. When I really got to see a television again was in 1977. So, I was basically without music and television for the first eight years when I was in the hole. When I was able to get on the main line and listen to music and see T.V., of course the things I wanted to hear were the things I heard when I was on the street. But by then those songs had to be at least nine years old. So, I would listen to oldies. And the new music it was hard to get into, but I slowly began to get into that. But when hip-hop began to come around, it caught on like wildfire. It reminds me how the Panthers and other groups started to catch on like wildfire. It reminded me of Gil Scott-Heron. He would spit that knowledge so clearly and that was the first thing that came to mind when I heard Grandmaster Flash, KRS-One, Paris, Public Enemy and Sista Soldier—the militancy.

What type of books were you reading?

We maintained study groups throughout when I was on main line. Much of the focus was on Cheik Anta Diop—He was considered by us to be the last Pharaoh. We also read the works compiled by Ivan Van Sertima. Of course, there were others.

In terms of a spiritual center, what helped you to get through?

Well the ancestors guided me back to the oldest religion known to man—Maat. We also studied those meditations that were developed by all of our ancestors—the Natives, the Hispanics, the Irish—not just the ones that were strictly African.

The youngest of seven children, Ji Jaga was born Elmer Pratt, in Morgan City, a port city in southwestern Louisiana, two hours south of New Orleans, on September 13 1947. 120 years earlier marked the death of Jean Lafitte, the so-called "gentleman's pirate" of French ancestry who settled in Haiti in the early 1800s until he was run out with most other Europeans during the Haitian revolution. Lafitte's claim to fame was smuggling enslaved Africans from the Caribbean to Louisiana during the Spanish embargo of the late 17th & early 18th centuries, often taking refuge in the same bayous that were Pratt's childhood home. Pratt was dubbed Geronimo by Bunchy Carter and assumed the name ji Jaga in 1968. The Jaga were a West African clan of Angolan warriors who Geronimo says he descends from. Many of the Jaga came to Brazil with the Portuguese as free men and women and some were later found among maroon societies in Brazil. How Jaga descendants could have ended up in Louisiana is open to historical interpretation, as most Angolans who ended up in Louisiana and Mississippi and neighboring states entered the US via South Carolina. Some Jaga were possibly among the maroon communities in the Louisiana swamplands as well. According to the Pratt, the Jaga refused to accept slavery—hence his strong identification with the name.

What were some of your earliest early childhood memories?

Well, joyous times mostly. Morgan City was a very rural setting and very nationalistic, self-reliant, and self-determining. It was a very close-knit community. Until I was a ripe old age, I thought that I belonged to a nation that was run by Blacks. And across the street was another nation, a white nation. Segregation across the tracks. We had our own national anthem, "Lift Every Voice and Sing," our own police, and everything. We didn't call on the man across the street for nothing and it was very good that I grew up that way. The worst memories were those of when the Klan would ride. During one of those rides, I lost a close friend at an early age named Clayborne Brown who was hit in the head by the Klan and drowned. They found his body three days later in the Chaparral River. And, we all went to the River and saw them pull him in. Clayborne was real dark-skinned and when they pulled him out of the river, his body was like translucent blue. Then a few years later, one Halloween night, the Klan jumped on my brother. So there are bad memories like that.

Does your mother still live there?

She's gone off into senility, but she's still living—94 years old this year. [She died in 2003 at 98 years-old] And every time I've left home, when I come back the first person I go to see is my mama. So, that's what I did when I got out of prison. Mama has always stood by me. And, I understood why. She was a very brainy person. Our foreparents, her mother was the first to bring education into that part of the swampland and set up the first school. When I was growing up, Mama used to rock us in her chair on the front porch. We grew up in a shack and we were all born in that house, about what you would call a block from the Chaparral River. She would recite Shakespeare and Longfellow to us. All kind of stuff like that at an early age we were hearing from Mama—this Gumbo Creole woman (laughs). And she was very beautiful. Kept us in church, instilled all kinds of interests in us, morals and respect for the elders, respect for the young.

What about your father?

My father was very hard working. He wouldn't work for no white man so he was what you could call a junk man. On the way home from school in Daddy's old pick-up truck we would have to go to the dump and get all the metal that we could find as well as rope, rags, anything. When we got home, we unloaded the truck and separated the brass, copper, the aluminum, so we could sell it separate. That's how he raised an entire family of seven and he did a damn good job. But he worked himself to death. He died from a stroke in 1956.

With an upbringing so nationalistic, what made you join the US military?

I considered myself a hell of an athlete. We had just started a Black football league. A few years earlier, Grambling came through and checked one of the guys out. So initially my ambition was to go to Grambling or Southern University and play ball. Because of the way the community was organized, the elders called the shots over a lot of the youngsters. They had a network that went all the way back to Marcus Garvey and the days when the United Negro Improvement Association (U.N.I.A.) was organizing throughout the South in the 1920s. My uncle was a member of the legionnaires, the military arm of the U.N.I.A. Of the seventeen people in my graduating class, six of us were selected by the elders to go into the armed forces, the United States Air Force. The older generation was getting older and was concerned about who would protect the community.

Many of the brothers that went to Vietnam have never gotten past it. You seemed to have made a progressive transition. How have you done that?

I've never suffered the illusion that I was aligned to anything other than my elders. And my going to Vietnam was out on a sense of duty to them. When I learned how to deal with explosives, I'm listening at that training in terms of defending my community. Most of the brothers that I ran into in the service really bought into being Americans and "pow" when they were hit with the reality of all the racism and disrespect, they just couldn't handle it.

What was it like to be a Black soldier in the US military in 1965?

This was my first experience with integration. But I was never was a victim of any racial attack or anything. During the whole first time I was in Vietnam—throughout 1966—I never heard the "N" word. And all of my officers were white. When I went back in 1968 that's when you would see more manifestations of racial hatred, especially racial skirmishes between the soldiers. But first off there were so many battles and we were getting ambushed so much. Partners were dying. We were getting over run. I mean it was just madness. If you were shooting in the same direction, cool.

You were very successful in the military. Why did you get out?

On April 4, 1968 Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed. I was due to terminate my service a month later. I wasn't gonna do it. I was gonna re-up 'cause I had made Sergeant at a very early age, in two tours of combat, so I could have been sitting pretty for the rest of my life in the military. I was loyal and patriotic to the African nation I grew up in who sent me into the service. And after Martin Luther King was killed, my elders ordered me to come on out of the service. King was the eldest Messiah. Malcolm was our generation's Messiah. And now that their King was dead, it was like there's no hope. So they actually unleashed us to do what we did. This is why when Newsweek took their survey in 1969, it was over 92% of the Black people in this country supported the Black Panther Party as their legitimate political arm. It blew the United States' mind.

Published on June 08, 2011 18:56

Saggy-Pants Laws: Red Herring to Control Kids

Saggy-Pants Laws: Red Herring to Control Kids by Marc Lamont Hill | Philadelphia Daily News

EARLIER THIS WEEK, the Fort Worth Transportation Authority in Texas announced that it will "get tough" on enforcing a dress code that bans sagging pants from the city's public transportation.

The Texas decision is nothing new. Over the past several years, cities around the country have made similar decisions regarding the hip-hop-inspired fashion trend. A year ago, New York state Sen. Eric Adams drew national headlines by unveiling the "Stop Sagging" campaign, a series of billboards and viral Web videos that decry the practice of wearing pants below the waist.

In Michigan, Louisiana, Texas and Florida, politicians have taken the anti-sagging movement even further by passing laws that outlaw the fashion trend through the creation of public-decency ordinances.

Do we really have nothing better to do?Don't get me wrong. I'm not a huge fan of sagging pants. The older I get, the more absurd and unattractive I find the practice. Still, the fact that legislators around the country can devote serious time, energy and political muscle to the sartorial predilections of teenagers means that we have seriously misplaced priorities.

Much of the outrage over sagging pants is rooted in the belief that the trend is an outgrowth of prison culture in which inmates are forced to sag their pants because they aren't permitted to wear belts. Others argue it's a sign of prison homosexuality, as gay inmates expose their buttocks to let others know that they are sexually available.

While the claims about prison culture may be true - though they look and smell like a well- crafted urban legend - there is little credible evidence that they provide the origins of the current hip-hop trend. There is even less evidence that the youth who sag their pants are consciously or unconsciously trying to mimic the practices of prisoners.

These sorts of arguments are nothing more than red herrings that play on a cynical, unsophisticated and reactionary vision of our youth. They allow politicians to score cheap political points on the backs of our children.

By linking sagging pants to prison culture, opponents are able to scare the public into believing in a one-to-one relationship between fashion choices and social deviance. By connecting it to homosexuality, they are able to play on the homophobic myth that being gay is a social contagion that can be avoided through the use of a sturdy belt.

Such arguments are not new. From the Zoot Suit Riots in Los Angeles to the Senate hearings on gangster rap, every generation of adults has expressed deep anxiety about the cultural practices of the next generation. This anxiety is rooted in a natural but troublesome nostalgia that allows adults to forget how much our parents hated our hairstyles, clothing and music preferences. The current moral panic, however, is particularly dangerous because it seduces us into focusing on the behavior of youth rather than on social conditions that are placing youth under unprecedented levels of attack.

Today's anti-sagging movement is not an isolated project, but part of a broader set of policies that comprise a full-fledged "War on Youth." From unconstitutional civil injunctions against gangs to the rise of draconian zero-tolerance policies in schools, our nation has produced a set of policies that construct our youth in increasingly criminalized terms. In reality, these policies - combined with the elimination of after-school programs, recreation centers and public libraries - are far more likely to produce anti-social outcomes than a pair of low-riding jeans.

By focusing on relatively harmless fashion trends, we effectively sidestep the issues that truly undermine the life chances of our youth such as poverty, crumbling schools and an increasingly shaky labor market. Our attention to fashion contributes to an increasingly popular narrative about this generation of youth that focuses on containment and blame rather than investment and love. If we truly worry about the futures of our children, we should stop judging their clothes and take a good look at ourselves.

***

Daily News editor-at-large Marc Lamont Hill is an associate professor of education at Columbia and the host of "Our World With Black Enterprise," which airs at 6 a.m. Sundays on TV-One. Contact him at MLH@marclamonthill.com.

Published on June 08, 2011 18:44

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.