Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1083

June 1, 2011

Rap Sessions: From Precious II For Colored Girls: The Digital Highlight Reel

For the 5th year the Institute for the Study of Women and Gender in The Arts and Media at Columbia College and Rap Sessions co-presented a Community Dialogue. The powerful 'townhall meeting,' created and moderated by award-winning journalist, activist, political analyst and Institute Fellow Bakari Kitwana explored contemporary moments in popular culture and political debates where race, image and identity were center stage.

The program featured Elizabeth Méndez Berry (journalist and author, "The Obama Generation, Revisited," featured in The Nation), John Jennings (SUNY Buffalo; co-author, Black Comix: African American Independent Comix and Culture), Joan Morgan (journalist, culture critic, and author, When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost), Mark Anthony Neal (Duke University; author, New Black Man), and Vijay Prashad (Trinity College; author, The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World).

This highlight reel presents some of the program's prominent moments.

Published on June 01, 2011 05:57

May 31, 2011

Dirk "Legend"? Race, Nation, and the NBA

Dirk "Legend"? Race, Nation, and the NBA David J. Leonard | special to NewBlackMan

On the eve of the 2011 NBA finals, Professor Walter Greason asked the readers on NewBlackMan: "Can Dirk Save the NBA?" Citing the NBA's history, its efforts to court white fans from "middle-America," the centrality of racial meaning to its marketing strategies/popularity, Gleason concludes that Dirk Nowitzi has the potential to "save the NBA." He writes, "If Nowitzki overcame James, especially in a series of emotionally draining, well-played games, a new version of the Larry Bird-Magic Johnson rivalry of the 1980s would be born. It was that era that created the possibility of Jordan's global appeal. If the NBA hopes to create a global sensation that will extend its reach for new generations of fans in the twenty-first century, Nowitzki must defeat James in this year's Finals. Dirk may be the last chance to save the NBA."

At one level, the argument about the NBA's desire to produce white superstars to cater to white fans otherwise uncomfortable with a largely black league erases the NBA's global turn. With a league increasingly reliant and interested on fans from Latin America, Asia, and Europe, the necessity for a Larry Bird in the twenty-first century has weakened. According to a 2007 study, 89 percent of Chinese between the ages of 15 and 54 were "aware of the NBA," with 70 percent of youth between the ages of 15 and 24 describing themselves as fans. With 1.4 billion viewers watching NBA games during the 2008 season (up through April 30th) on one of the 51 broadcast outlets in China, and 25 million Chinese visiting NBA.com/China each month, basketball and the NBA are cultural phenomena within China.

If we take China as example, the NBA has been tremendously successful marketing the game through the likes of Bryant, James, and Iverson, whose talents, racial bodies, and whose markers of hip-hop/youthfulness/ have rendered them as authentic basketball commodities. As of 2010, Kobe Bryant possessed the top-selling jersey for 4 straight years in China. That year, LeBron James, Dwight Howard, Kevin Garnett, and Derrick Rose founded out the top-five. Yao Ming wasn't even amongst the top 10. His absence can be partially attributed to injuries but for several years he has been outside the top 5. A similar circumstance is evident in Europe, where Kobe Bryant, LeBron James, and Dwayne Wade were the top selling jerseys in 2010 (10 out of top 15 were African American players; 5 European players) All that being said, in a cultural sense, in terms of image, and in terms of the NBA's relationship with corporate America, there remains an effort to both conceal its blackness all while selling its whiteness.

As such, Gleason's article rightfully elucidates the ways in which, as noted by Todd Boyd, the NBA "remains one of the few places in American society where there is a consistent racial discourse," where race, whether directly or indirectly, is the subject of conversation at all times (2000, p. 60). He connects to a larger history that leads us back to the Palace Brawl, to Jordan, to Magic v Bird, and even into the 1970s. Yet, the NBA's effort to re-brand itself racially most recently started around 2003, with an increased emphasis after the Palace Brawl.

The 2003-2005 seasons was a "low point" for the NBA, when it saw a sharp decline in fan support. Television ratings were down, while complaints from corporate sponsors increased. Opinion polls consistently ranked NBA players as the least liked professional athletes in American sports. In response, the NBA hired Matthew Dowd, a Texas strategist who had previously worked with George W. Bush on his reelection campaign. Having successfully helped Bush find immense support within Middle America, Dowd was brought in "to help" Stern "figure out how to bring the good 'ol white folks back to the stands" (Abramson 2005).

In this context, you would think there would be a significant marketing appeal or potential for Dirk is this regard. He offers a white body and ample skills that purportedly provides something different from the NBA's African American superstars. Yet, despite success on the court, despite an MVP and appearance in the NBA finals, Dirk has not to-date emerged as the NBA's great white hope. A championship in 2011, a final's MVP, and even his postering LeBron (not gonna happen) aren't going to change this role.

Its not like Dirk is new to the league; he hasn't captured the national imagination to date (even though he won an MVP), so it wouldn't seem like a championship will result in a dramatic increase in popularity. While Dirk has "whiteness" he doesn't offer the narrative central to white racial framing. The power of white sporting narratives focuses on a fantasy about bootstraps, hard work (think Hoosiers), etc. and players that come out of European system don't fulfill these narrative fantasies. Moreover, in the national imagination, whiteness and American-ness functioned interchangeably so that neither Dirk nor LeBron possess the requisite identities to function as white in an American context.

While commentators often assume that the yearning for white superstars reflects a desire of white fans to "root for someone who looks them," the incentives here are a bit more complex. The popularity of Larry Bird, for example, rests not simply with his whiteness but in the narratives, tropes, and ideologies embedded within his body; a body that pivots around national, class, and racial meaning. Bird reinforced hegemonic frames concerning whiteness and working-class masculinity. Notions of teamwork, intelligence, hard work, and determination, all of which play through ideas of white (American) masculinity, help us understand why Bird (and to a lesser degree other white Americans) captured the white basketball imagination. In other words, Bird provided a certain amount of nostalgia for a time in sports. He provided an alternative white male hero to "African American professional basketball players who are routinely depicted in the popular media as selfish, insufferable, and morally reprehensible" (Cole & Andrews 2001, p. 72). Yet, Dirk isn't able to function as such a binary.

Dirk can't save the NBA (for whom; from whom?) because he doesn't offer the desired narrative; he doesn't embody nostalgia for basketball of yesteryear, to small-town basketball played on dirt courts in America's heartland – he, like, LeBron has no possibility of ever playing for Hickory.

In turn, he doesn't reinforce dominant narratives of white success as a result of hardwork, determination, bootstraps, and intelligence. Dirk, the child of a professional basketball playing mother and an accomplished handball player, joined DJK Würzburg, a renowned basketball club in Germany, at the age of 15. Dedicating himself to basketball, Dirk was a quasi professional until he joined the NBA ranks in 1998. Six years later, despite amassing All-star numbers on the court, the NBA's global turn had not produced a marketable white (European or otherwise) baller to fill Larry Bird's shoes. Nobody had filled his does. Some cited this failure as part of the NBA's ongoing image problem.

In June 2004, Larry Bird sat down with Magic Johnson, Carmelo Anthony, and LeBron James, and host Jim Gray to discuss the state of basketball in a symbolic passing of the torch from the NBA's past to its future. The "2 on 2 sit down,", aptly taking place at the gym used as the home court for Hickory High school in Hoosiers, a film that celebrated the era of whiteness (Jim Crow) as the era of basketball greatness, sparked controversy when Larry Bird lamented the declining presence of white athletes in the NBA. Responding to Jim Gray's question as to whether the NBA needed more white superstars Bird offered the following assessment of the racial landscape of the NBA: "Well, I think so. You know when I played you had me and Kevin (McHale) and some others throughout the league. I think it's good for a fan base because as we all-known, the majority of the fans are white America." He further disrupted while simultaneously legitimizing the hegemonic logics of race and sports when he argued, "And if we just had a couple white guys in there you might get them a little excited. But it's a black man's game and it will be forever. I mean the greatest athletes in the world are African American."

While the media feigned a certain amount of shock, denouncing the comments as extreme, racist, and hateful, his rhetoric merely reflected the commonsense logic of a broader discourse. On one level, Bird seems to be giving voice to the longstanding presumption regarding black male athletes possessing a genetic advantage over white male athletes in that the absence of whites in the NBA is a result of natural selection.

On another level, Bird's comments are not simply about the dialects of race, genetics and sport, but about the financial, spiritual, cultural and racial loss felt (or imagined) in the face of the declining presence of whites within the NBA. In other words, the purported and assumed declining interest in the NBA, the declining quality of play, the diminished "respectability" of players (what happened to the role models), and most importantly the cultural importance of the game are in deadly decline because the white NBA players are an assumed "endangered species." For example, in 2004 ESPN.com "Black History Month" article entitled "The Technicolor Sports Hero" that documents the increased visibility of black athletes within sports marketing, Darren Rovell begins his discussion by pointing out the declining importance of white athletes:

To silence the most glib sports executives, ask them who they think is the most marketable white athlete today. It usually does the trick. A chorus of "umm's," "huh's" and "give-me-a-minute's" are used to bide for time before they finally spit out names like Lance Armstrong, Tony Hawk and Andy Roddick. Yet ask for their assessment of the most marketable black athletes and the names just flow off the tips of their tongues.

In other words, racial progress, the breakdown to the walls of segregation, isn't merely providing opportunities for black athletes, but has lead to not only a diminished importance for white athletes on-the-court, but within the cultural imagination. Again from Rovell,

And active white athletes are becoming less recognized among sports fans. On its top 10 list of marketable athletes in America, Marketing Evaluations, which produces the Sports Q Ratings, has Brett Favre at the highest active white athlete on the list at No. 9. That's the lowest that first white athlete to appear on the list, says the company's executive vice president, Henry Schaffer. Will it come a day when no white athlete appears on the list? Or could the pendulum of marketing trends someday reverse itself, and white athletes begin to dominate in the advertising arena again?

As such, Bird's comments and the yearning (that Professor Gleason critically elucidates) for Dirk to "save the league" reflect the broader fears, panics and anxieties that define a post civil rights America. It isn't simply a yearning for a white (American) superstar, but the presumed narratives that because of white racial frames are restricted from today's NBA stars. Although Michael Jordan penetrated the narrative colorline through embodying "the American Dream [as] a matter of personal perseverance," race is central to the cultural meanings of the NBA, yet that transcends skin color. Jordan as "Africanized Horatio Alger" (Patton quoted in McDonald, 2001, p. 157) reaffirmed a narrative so often reserved for white American athletes: the story of the "army of athletes who possess the (new) right stuff with modest beginnings, skill, and personal determination" (McDonald 2001, p.157).

While Dirk will certainly be celebrated through these rhetorics (while LeBron won't), his whiteness notwithstanding, the 2011 NBA finals will not lead to the crowning of a "German Horatio Alger." There is no French Lick in Germany and therefore no Dirk Legend.

*** David J. Leonard is Associate Professor of Comparative Ethnic Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press).

Published on May 31, 2011 13:34

Angela Davis and Marc Lamont Hill on 'Our World'

Our World with Black Enterprise | May 29, 2011

Host Marc Lamont Hill Talks with Activist & Scholar Angela Davis

Published on May 31, 2011 12:59

May 30, 2011

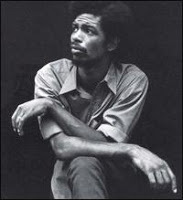

The Devil and Gil Scott-Heron

The Devil and Gil-Scott Heron by Mark Anthony Neal

As the story goes, Robert Johnson, one of the most influential guitarists of the twentieth-century, met the "Devil" at a crossroads in Clarksdale, Mississippi. Accordingly Johnson sold his soul to that "Devil" in order to play the guitar with a power and precision that many deemed otherworldly. The "Devil," in this instance, was likely the Yoruba Orisha of the crossroads, alternately known as "Legba," "Elegba," "Eshu Elegbara" and Papa Labas in the fiction of Ishmael Reed. That power and precision that Johnson wielded so effectively, might be better referred to as truth, not so neatly packaged in the Blues tradition—a tradition that notably transcends the musical genre that shares its name.

As Angela Davis notes in her book Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, "the blues were part of a cultural continuum that disputed the binary constructions associated with Christianity…they blatantly defied the Christian imperative to relegate sexual conduct to the realm of sin. Many blues singers therefore were assumed to have made a pact with the Devil." (123) Within African-American vernacular, the figure of Legba is often referred to as the "Signifying Monkey" and perhaps most well known by the Oscar Brown recording with that title and Henry Louis Gates's groundbreaking study The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism (1988).

Though the figures who possess the power of the crossroads are often thought to solely reside in Black oral traditions—the proverbial poets, preachers and rappers—others such as Blackface actor Bert Williams and Johnson have been written into the tradition. But for all the respect and pride derived from the brilliance of such artists, in the end they remain always already outside of the communities for which the truth most matters. Davis observes that the "blues person has been an outsider on three accounts. Belittled and misconstrued by the dominant culture that has been incapable of deciphering the secrets of her art…ignored and denounced in African-American middle-class circles and repudiated by the most authoritative institution in her own community, the church." (125)

In his legendary essay "Nobody Love A Genius Child: Jean Michel Basquiat, Flyboy in the Buttermilk," Greg Tate puts an even finer point on the status this cultural outsider: "Inscribed in his (always a him) function is the condition of being born a social outcast and pariah. The highest price exacted from the Griot for knowing where the bodies are buried is the denial of a burial plot in the communal graveyard…With that wisdom typical of African cosmologies, these messengers are guaranteed freedom of speech in exchange for a marginality that extends to the grave."

***

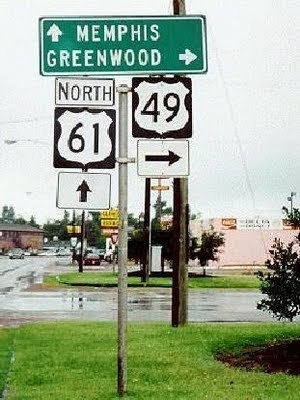

A year ago Gil Scott Heron released, I'm New Here his first studio recording in fifteen years. Fittingly, the lead single was a cover of Robert Johnson's "Me and the Devil," and while the choice of material may not have wholly been Scott-Heron's, the song—as the spiritual embodiment of its composer—for damn sure choose Gil Scott Heron. And this is not to suggest that Scott Heron—who often referred to himself at a "Blues-ologist"—was unaware of Johnson; He like Johnson, had spent a lifetime at the mythical crossroads that have defined much of Black vernacular culture. I'm New Here was a dark and brooding reminder of the costs associated with the power that the crossroads engenders. Burn away all the bells and whistles, bleeps and blurs, and Scott-Heron is standing at that same intersection of Highways 61 and 49 in Clarksdale, Mississippi with Robert Johnson, Billie Holiday, Henry Dumas, Linda Jones, Son House and so many others.

Shame on every writer who reported Gil Scott-Heron's death with the blurb, "Godfather of Rap," writers who have—per Angela Davis' observations—totally missed the point of the man's career. It was a term that Gil Scott-Heron was not ambivalent about: "There seems to be a need within our community to have what the griot provided supplied in terms of chronology; a way to identify and classify events in black culture that were both historically influential and still relevant (Now and Then: The Poems of Gil Scott Hereon, xiv). This is less Scott-Heron distancing himself from Hip-hop (though he would do so from time to time), but more a recognition that what he did, sat at the feet of traditions that came before him. He writes, "there were poets before me who had great influence on the language and the way it was performed and recorded: Oscar Brown, Jr., Melvin Van Peebles, and Amiri Baraka were all published and well respected for their poetry, plays, songs and range of other artistic achievements when the only thing I was taping were my ankles before basketball practice." (xiv)

Shame on every writer who reported Gil Scott-Heron's death with the blurb, "Godfather of Rap," writers who have—per Angela Davis' observations—totally missed the point of the man's career. It was a term that Gil Scott-Heron was not ambivalent about: "There seems to be a need within our community to have what the griot provided supplied in terms of chronology; a way to identify and classify events in black culture that were both historically influential and still relevant (Now and Then: The Poems of Gil Scott Hereon, xiv). This is less Scott-Heron distancing himself from Hip-hop (though he would do so from time to time), but more a recognition that what he did, sat at the feet of traditions that came before him. He writes, "there were poets before me who had great influence on the language and the way it was performed and recorded: Oscar Brown, Jr., Melvin Van Peebles, and Amiri Baraka were all published and well respected for their poetry, plays, songs and range of other artistic achievements when the only thing I was taping were my ankles before basketball practice." (xiv)"The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" is easily the best known of Gil Scott-Heron's compositions. Written and recorded just as the most militant energy of the Civil Rights and Black Power era seemed to be waning, the song was a sharp and prescient view of the commodities of struggle and resistance—the place where revolutionary acts give way to market forces and prime time ratings. In 1971, Scott-Heron couldn't have imagined 24 hour news programming like CNN, let alone Al Jazeera, though "Revolution" proves as relevant now, as it might have even been when he wrote it. To be sure, Gil Scott-Heron did pay a price for his truth-telling and his willingness to make politically relevant music accessible to all that would have it. Accessible is the telling term here, as Scott-Heron admitted that "because there were political elements in a few numbers, handy political labels were slapped across the body of our work, labels that maintain their innuendo of disapproval to this day." (xv)

Perhaps we'll never fully know if the drug-addiction and other dependencies that so often derailed Scott-Heron's vision was part of some COINTELPRO inspired conspiracy to deny our most gifted and passionate, access to the thing that matters the most—their right minds (surely cheaper and neater than assassination). When Albert King sang "I Almost Lost My Mind" he wasn't just whistlin' in the dark about the warm body that had just left his bed—somewhere folk like Huey P. Newton, Etheridge Knight, Esther Phillips, Sly Stone, Flavor Flav, and a host of others, including Scott-Heron, fully understood what he lamented. Yet can't help to think though, that Gil Scott-Heron knew that he was not here to be simply loved; that there were hard truths that he had to tell us and his addictions would always guarantee that we would keep him at an arm's distance. Those times he went silent, it was as much about those addictions and it was his unwillingness to bullshit us for the sake of selling records. If he couldn't tell us the truth, he wouldn't tell us anything, returning regularly to those crossroads via the needle or the pipe.

It is important to remember that Gil Scott-Heron was also a prodigy—was coloring outside the lines in ways that were significant, but not all that remarkable, for a generation of young Black folk who understood the importance of challenging boundaries from the moment they took their first breaths. Some might call that freedom. There was the grandmother, Lily Scott who made sure the young boy read books and read the weekly edition of The Chicago Defender—the closet thing to a Black national newspaper for Black Americans in the mid-20th Century—where Scott-Heron first read the columns of Langton Hughes. Before he married beats (and melodies) and rhymes, a 19-year-old Gil Scott-Heron had written his first novel.

Thankfully Scott-Heron took to heart Haki Madhubuti's (the Don L. Lee) adage that revolutionary language really didn't matter if it couldn't reach folk on the dance-floor; Scott-Heron took it a step further, recognizing, as the Last Poets and Watt Prophets did, that some of the cats never left the street corners. (At that same moment, Nikki Giovanni also understood there were also souls to be saved in the pews, hence her Gospel inspired Truth is on the Way). Those earliest Gil Scott-Heron recordings, like Small Talk at 125 Street, Pieces of a Man, Free Will and Winter in America, released on independent labels like Bob Thiele's Flying Dutchman and Strata-East, seemed like sonic counterparts to the $.05 cent poetry broadsides that poet and publisher Dudley Randall used to sell on the streets of Chicago in the 1960s.

Thankfully Scott-Heron took to heart Haki Madhubuti's (the Don L. Lee) adage that revolutionary language really didn't matter if it couldn't reach folk on the dance-floor; Scott-Heron took it a step further, recognizing, as the Last Poets and Watt Prophets did, that some of the cats never left the street corners. (At that same moment, Nikki Giovanni also understood there were also souls to be saved in the pews, hence her Gospel inspired Truth is on the Way). Those earliest Gil Scott-Heron recordings, like Small Talk at 125 Street, Pieces of a Man, Free Will and Winter in America, released on independent labels like Bob Thiele's Flying Dutchman and Strata-East, seemed like sonic counterparts to the $.05 cent poetry broadsides that poet and publisher Dudley Randall used to sell on the streets of Chicago in the 1960s. The revolution might not have been televised then, but if you listen closely to songs like "No Knock," (in response former Attorney General John Mitchell's plan to have law enforcement enter homes without knocking first, though he could have been talking about the Patriot Act), "Home is Where the Hatred Is" (on drug addiction) and "Whitey on the Moon" (which still elicits giggles in me) the revolution was clearly being recorded and pressed. The difficulty in those days, was actually making sure that distribution of Scott-Heron's music could match demand for it.

Gil Scott-Heron got unlikely support from Clive Davis—yes the same Clive Davis who would later create boutique labels for L.A. Reid and Kenny "Babyface" Edmonds, Sean "PuffyDiddyDaddy" Combs, and serve as svengali for Whitney Houston and Alicia Keys. Davis, who funded the now infamous "Harvard Report" on Black music while at Columbia Records, where he oversaw the careers of Miles Davis, Bob Dylan and Sly and the Family Stone, had been deposed from the label and was starting a new label, Arista. Davis needed acts, and in particular, acts that already had an established base, and Scott-Heron fit the bill.

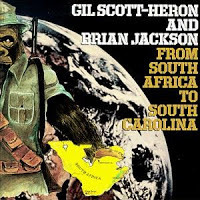

It was an odd marriage indeed—notable that Davis never really signed another political artist of Scott-Heron's stature—but it also allowed Scott-Heron to experience the most prolific period of his career, with defining albums like First Minute of a New Day (1975), From South Africa to South Carolina (which featured the anti-apartheid anthem "Johannesburg"), Bridges (1977), and Reflections (1981), which featured his 12-minute scouring of then just elected President Ronald Reagan on "B-Movie" (released months after Reagan's 1981 shooting and after Scott-Heron had completed a national tour opening for Stevie Wonder).

For all of our memories of Scott-Heron's political impact, his music covered a full gamut of experiences. A track like "Lady Day and Coltrane" paid tribute to Black musical traditions, while songs like "A Very Precious Time" and "Your Daddy Loves You" found Scott-Heron thinking about issues of intimacy. Well before proto-Harlem Renaissance writer Jean Toomer would be recovered by scholar and critics, Scott-Heron set Toomer's Cane to music. Even as young activists make the connection between Black life and environmental racism, Scott-Heron offered his take on the plaintive "We Almost Lost Detroit."

For all of our memories of Scott-Heron's political impact, his music covered a full gamut of experiences. A track like "Lady Day and Coltrane" paid tribute to Black musical traditions, while songs like "A Very Precious Time" and "Your Daddy Loves You" found Scott-Heron thinking about issues of intimacy. Well before proto-Harlem Renaissance writer Jean Toomer would be recovered by scholar and critics, Scott-Heron set Toomer's Cane to music. Even as young activists make the connection between Black life and environmental racism, Scott-Heron offered his take on the plaintive "We Almost Lost Detroit." "We Almost Lost Detroit" was later sampled by Kanye West for Common's "The People," speaking to the ways that Scott-Heron remained relevant some thirty years after his popularity peaked. Much has been made about West's "duet" with Scott-Heron on "Lost in the World" (drawn from Scott-Heron's "Comment # 1) and Scott-Heron's use of West's "Flashing Lights" on the recent "On Coming from a Broken Home." The latter song was drawn from Scott-Heron's tribute to his grandmother Lily Scott, who died in 1963. In a society in which fatherlessness continues to be deemed as simply pathology, Scott-Heron defiantly asserted "I come from what they called a broken home/but if they had ever really called at our house/they would have known how wrong they were…My life has been guided by women/but because of them I am a man."

On Friday May 27, 2011, Gil Scott-Heron went home to reunite with Lily Scott. His job was done.

***

Mark Anthony Neal is the author of five books including the forthcoming Looking for Leroy. He is co-editor (with Murray Forman) of That's the Joint!: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader (2nd Edition) which will be published this summer. Neal teaches African-American Studies at Duke University.

Published on May 30, 2011 19:24

Byron Hurt: Why I Am Rooting for LeBron James

Why I Am Rooting for LeBron James by Byron Hurt | special to NewBlackMan

Although he has yet to win his 1st NBA championship, LeBron James has proven one thing: wherever he plays the game of basketball, he wins. As a high school phenom at Akron's St. Vincent - St. Mary's High School, James won three state championships en route to becoming a Cleveland hardwood legend. The state of Ohio named him Mr. Basketball three consecutive years, and after being named the MVP at the McDonald's All-American Game, the EA Sports Classic, and the Jordan Capital Classic, James decided to forego college and entered the NBA draft. Many people thought, myself included, his decision to skip college was misguided. But James quickly turned doubters into believers.

When the Cleveland Cavaliers selected James as the number one pick overall, fans, coaches, analysts, and members of the media placed extraordinarily high expectations on the local hero dubbed "King James." As a pro, James has exceeded those expectations in spectacular fashion. In his first NBA game, he performed under tremendous scrutiny, scoring 25 points, 9 assists, and 6 rebounds. The Clevelander quickly rose to superstar status and turned the lowly Cavaliers organization into a winning franchise after just three NBA seasons. After failing to make the playoffs in his rookie season, James led the Cavs to the NBA postseason from 2006-2010.

In 2007 – and with very little talent around him – James carried his team through the Eastern Conference Finals matching up against Tim Duncan's San Antonio Spurs in the NBA Finals. Although the Spurs swept the Cavaliers 4-0, James and the upstart Cavaliers had arrived as the newest and unlikeliest perennial Eastern Conference powerhouse. He helped lift the Cleveland Cavaliers – a small-market team – to among the NBA elite. Sports networks ABC, ESPN, and TNT placed the Cavs into their nationally televised lineups. With James as its main attraction, the Cavalier franchise had a 60 plus win squad on its hands, and King James single-handedly bolstered the city's local economy. He also won an Olympic Gold medal as a member of the 2008 USA national basketball team. The new face of the NBA, James became a model of grace, dignity, maturity, and supreme athleticism.

James' poise is equally impressive. Many athletes with such burdensome expectations would implode under the bright lights, yet James performs brilliantly, over and over again, as if he was born to take the NBA's center stage. For a young man who did not attend college, his post-game and one-on-one interviews with the media prove that he is intelligent, well spoken, and has a very high basketball I.Q. For nearly two years, the sports media hounded him about his next career move once his contract with the Cavaliers expired in July 2010. Sports fans nationwide speculated about his future plans – rabidly insisted he join their favorite team. James coolly handled the media's interrogation of his looming free agency, and deftly held his cards close to the vest. When he finally became a free agent, and with the entire NBA world watching, James publicly made his bold, life-changing decision on national television in an hour-long special called "The Decision."

Sports pundits and NBA fans derided James for his awkward self-promotion, in which the reigning NBA MVP conversed for nearly an hour with sports reporter Jim Gray before ultimately revealing his decision. His decision? To leave the Cleveland Cavaliers, a team built to contend for championship, to join the Miami Heat, a team that struggled to make it into the playoffs. James' choice left Cleveland's owner, Dan Gilbert, feeling spurned, and the Cavs' fan base instantly turned on James, claiming the league's MVP was a quitter and disloyal to the city of Cleveland. Other fans across the country, particularly in New York, New Jersey, and Chicago, whose teams had publicly serenaded James for two years to join them, felt snubbed by James' decision to head to Miami. Many became bitterly hostile, sending James racist hate mail and frequently booing James whenever his new Heat team played in their cities' basketball arenas. But by choosing the Heat over the Cavaliers, Knicks, Nets, and Bulls, James revealed that he was neither Dan Gilbert's million-dollar slave nor the possession of legions of desperate fans. In "The Decision," James decided to be his own man, and made the unpopular, independent declaration to go his own way.

Almost one year after his decision, James still hasn't recovered from selecting to follow his own heart and mind. As a result, his image has taken a huge hit, and his popularity has diminished greatly among NBA fans. In a recent ESPN poll, 59% shows that the majority of NBA fans do not want James to win an NBA championship. It is likely fans are rooting against him simply because James didn't play to their expectations. Instead, LeBron James self-actualized by taking ownership of his life. He did what he wanted to do and hasn't looked back with regret or concern for naysayer opinions. He used his personal power and athletic value to carve out a new identity, shape his own destiny, and in the process, did not cow tow to the media, fans, or submit to the powers that be.

Although I wanted LeBron to join the New York Knicks or the future Brooklyn Nets, I respected and appreciated the courage it must have taken for the superstar to make such a risky move. "The Decision" for which James is still often criticized, took guts that many athletes (and most people) just don't have when it comes to making potentially life-altering choices. But LeBron James did have the guts to do make a bold call, and now his risky decision seems to be paying off nicely. On Thursday night, his Miami Heat defeated the Chicago Bulls in this year's Eastern Conference Finals. Almost one year after leaving the Cleveland Cavaliers, James is back in the NBA championship and will compete against Dirk Nowitzki and the Dallas Mavericks to win his first NBA championship.

While most fans will be rooting against LeBron James, I will be rooting for him as if he were my own son. I admire James' aptitude to make a sound decision in his own best interest, regardless of how others around him felt about it.

If only we could all be such bold, empowered, self-affirming, deciders.

***

Byron Hurt is a former college athlete and the host of the Emmy Award-nominated television show, REEL WORKS with Byron Hurt. He is also the producer/director of the upcoming documentary film, Soul Food Junkies.

Published on May 30, 2011 10:55

Can Dirk Save the NBA?

Can Dirk Save the NBA? by Walter Greason | Special to NewBlackMan

Game 7 of the 2011 Finals - Dirk Nowitzki receives a pass on the wing, guarded by LeBron James in the last minute of a tightly fought series. Two games have gone to overtime. None of the victories have been by more than three points. James' ascension as the pre-eminent international star hinges on the next eight seconds. While Nowitzki's play in the post-season has elevated him to the top echelon of current athletes in the NBA, doubts persist about his ability to deliver a championship under this kind of pressure. He fakes right and dribbles twice hard to his left to the elbow of the lane and elevates for a high-arcing shot over James' outstretched arm. The ball floats forever, and the fate of the NBA rests on its descent.

In 2006, the Dallas Mavericks lost an embarrassing Finals series to the Miami Heat, led by Dwayne Wade and Shaquille O'Neal, because they gave up a late lead in Game 3 and proceeded to lose the next three games. It was a final bow for O'Neal, demonstrating that he could win a title without Kobe Bryant. For Wade, it was an emergence on the national and international stage that held tremendous promise for future performance. Over the next five years, the Los Angeles Lakers and the Boston Celtics took center stage in the league as O'Neal's star faded and Wade became more famous for his cell phone commercials alongside Charles Barkley.

In this time, the NBA struggled to continue its development as a sports franchise in the American marketplace, despite the struggles of Major League Baseball. Bryant, Wade, Dwight Howard, and James were unable to break through the scandals of Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, and other alleged steroid users to capture the imaginations of the American public the way Michael Jordan had. The NBA could not escape the reality that it was a predominantly African American league reliant on a majority white American consumer base. In markets like Utah, Indiana, and Memphis (not to mention Oakland, Houston, and San Antonio) racial and ethnic considerations shaped the rosters and marketing of the NBA franchises over the last decade in ways that were unimaginable between 1980 and 2000. The problem was not the failure of athletes to reproduce Michael Jordan's skills, performance, or image. It was the absence of a Larry Bird figure to challenge any of them.

Nowitzki held the promise of a great white basketball player when he arrived in the 2006 Finals. Yet as a German player, he did not spark the interest of white Americans to even the same degree that his former teammate from Canada, Steve Nash, did. (See Nash's two MVP awards over a more deserving O'Neal for evidence of Nash's popularity.) Because Nowitzki lost in 2006, then suffered a humiliating first-round exit against Golden State in a later playoff series, he could not become the inheritor of Larry Bird's legacy that would motivate passionate interest among the white men, ages 35-65, who powered the global marketing force of the National Football League. The opportunity presents itself again now in 2011 after the Dallas Mavericks' victory against the Oklahoma City Thunder.

With James and the Heat going back to the Finals this year to meet Nowitzki and the Mavericks, the ascension of James as the league's leading superstar and best player would only reinforce the marketing trends against broader white (and corporate) interests in the NBA. Compare the advertisers for the NFL, MLB, and NBA sometime. Just watch how different the products and actors are in the various commercial breaks. You will notice subtle but important gradations about the markets the different leagues serve. If Nowitzki overcame James, especially in a series of emotionally draining, well-played games, a new version of the Larry Bird-Magic Johnson rivalry of the 1980s would be born. It was that era that created the possibility of Jordan's global appeal. If the NBA hopes to create a global sensation that will extend its reach for new generations of fans in the twenty-first century, Nowitzki must defeat James in this year's Finals. Dirk may be the last chance to save the NBA.

***

Walter Greason is Associate Professor of History at Ursinus College. He is the author of The Path to Freedom: Black Families in New Jersey, The History Press, 2010

Published on May 30, 2011 10:47

May 28, 2011

Adam Mansbach on Gil Scott-Heron

"He was Breaking Shit Down": Remembering Gil Scott Heron by Adam Mansbach | Special to NewBlackMan

I've known for fifteen minutes now that Gil Scott-Heron is gone. Time enough to play "Winter in America" and "Pieces of a Man," and to cry, and for the belief that his death is among the greatest tragedies I've ever known to harden inside me. That probably sounds ridiculous, and perhaps it is. Certainly, Gil died in slow motion: there is nothing to be surprised at here, no sudden violence ripping apart the fabric of a life. But the fact remains: the most incisive and salient political musician this country has ever produced – ever – is gone.

The fact that drugs took him under – and I don't mean today, I mean over and over again ¬– makes it worse; makes me angry in a diffuse, perhaps unreasonable way: leads me into thought-rants like if he'd been acknowledged as the national treasure he was, if they ("they") had given him a fucking MacArthur, then at least he would've been one of those enough-money-to-function drug addicts, and he'd be with us still, shadow-version of himself or not.

But all that is beside the point. First things first, the depth and scope of Gil Scott-Heron's musical-political content is beyond compare. Nothing and nobody comes close: not Bob Dylan, not KRS-One, nobody. During the prime of his career (1970-1984), he was out in front on practically every major political issue – not just nationally, but globally. His commentary was incisive, nuanced, hilarious, and routinely prescient. He carved up the entire Nixon administration with a stainless steel scalpel, psychoanalyzed Reagan and Reagan-happy America better than anybody else I can think of. Challenged the South African government, clarioned the dangers of nuclear power, called out racist cops. Did environmentalism is the early seventies. Gun control in 1980. The Iranian Revolution, the No-Knock Law. Abortion.

And that's just his topical shit; it's harder to say what "Ain't No Such Thing As Superman" or "Winter in America" is about… unless you just cut to the chase and start throwing around words like "zeitgeist," or phrases like "the troubled soul of America." And if Gil didn't invent the pointedly-absurdist extended-free-associative-pop-culture riff, he certainly perfected it in his most famous song.

But none of that even get at his greatness, or at least not fully. The flipside of Gil's panoramic political worldview was the depth of his self-analysis, the delicacy of his portraiture: for every world-shaking anthem, every "Johannesburg," there is another song buried deeper in his catalogue, one that charts the quietest, most intimate of blues moments with sublime beauty, raw honesty, unfettered emotion.

I met Gil in 1994, when I was seventeen and he was touring behind the release of his first new album in a decade. Went to check him at Regattabar in Cambridge, and rushed him afterward, a sheaf of my own poems in hand. He didn't break his stride – clearly, the man had somewhere to be – but he did take them. Several hours later, well past midnight, my phone rang (that is, the phone in my parents' house rang). It was Gil. He'd read my shit. For the next two hours, I listened to him talk, and jotted notes. I still have the piece of paper. It says things like "Black Elk Speaks" and "Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man." The word "Skippy" is underlined a bunch of times; midway into the conversation, I figured out that Skippy was Jimmy Carter, the peanut farmer, and the vast, intricate web of Gil's monologue started to make more sense – a frightening amount of sense, in fact.

Was he high as hell? Probably. It didn't matter. He was breaking shit down, and I never wanted that phone call to end. I moved to New York City later that year, and ran into him soon after, on 112th and Broadway, in front of the used-CD stand. He didn't remember our phone call, but I never forgot it.

There's much more I'd like to say, but it's one a.m. and I suspect I've got more tears to shed. Writing this late is probably a mistake, and so is writing this early, this soon after the fact. I don't want to end this with a flourish, or a benediction or a cliché; I guess I don't really want to end it at all.

***

Adam Mansbach's last novel, The End of the Jews (Spiegel & Grau) won the California Book Award. Named a Best Book of 2008 by the San Francisco Chronicle, it has been called "extraordinary" by the Los Angeles Times, "beautifully portrayed" by the New York Times Book Review and "intense, painful and poignant" by the Boston Globe, and translated into five languages. His new book Go the F**k to Sleep, a satire abour parenting will be published next month.

Published on May 28, 2011 04:30

May 27, 2011

Meet Big Daddy Kane

The State of Things with Frank Stasio | WUNC

The State of Things with Frank Stasio | WUNCMeet Big Daddy Kane

Big Daddy Kane is one of the most influential voices from the golden era of hip-hop. In the 1980s, Kane entered the music scene with style, sex appeal and the skills to rhyme over rapid-fire beats – a combination that sealed his place in hip-hop history as one of the best emcees of all-time. The Brooklyn-born rapper now makes his home in North Carolina where he continues his creative work. He joins host Frank Stasio to talk about his influential career and his role as a rap music pioneer.

Listen

Published on May 27, 2011 17:02

National Black Heritage Swim Meet

The State of Things with Frank Stasio | WUNC

National Black Heritage Swim Meet

Go to a competitive swim meet and you are likely to encounter a sea of white faces. Minorities are notoriously underrepresented in the sport.

But about 14 years ago, a group of North Carolina parents got together and decided to make swimming a little more diverse. They formed a traveling swim team called the North Carolina Aquablazers and in 2003, they started the National Black Heritage Championship Swim Meet. The annual meet will be held this weekend at the Triangle Aquatic Center in Cary, NC. Host Frank Stasio talks about it with Lisa Webb, vice president and co-founder of the North Carolina Aquablazers swim team, and Tom Hazelett, Aquatics director at the downtown Durham YMCA and Durham site coach for the YMCA of The Triangle swim team.

Listen

Published on May 27, 2011 16:44

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.